CULTURAL LEGACY

Reclaiming Fernandeño Water Culture

LAND BACK

550+ Acres Return To The Tribe

FAMILY MEMORIES

Inspiring the next generation

Timothy R. Ornelas

CULTURAL LEGACY

Reclaiming Fernandeño Water Culture

LAND BACK

550+ Acres Return To The Tribe

FAMILY MEMORIES

Inspiring the next generation

Timothy R. Ornelas

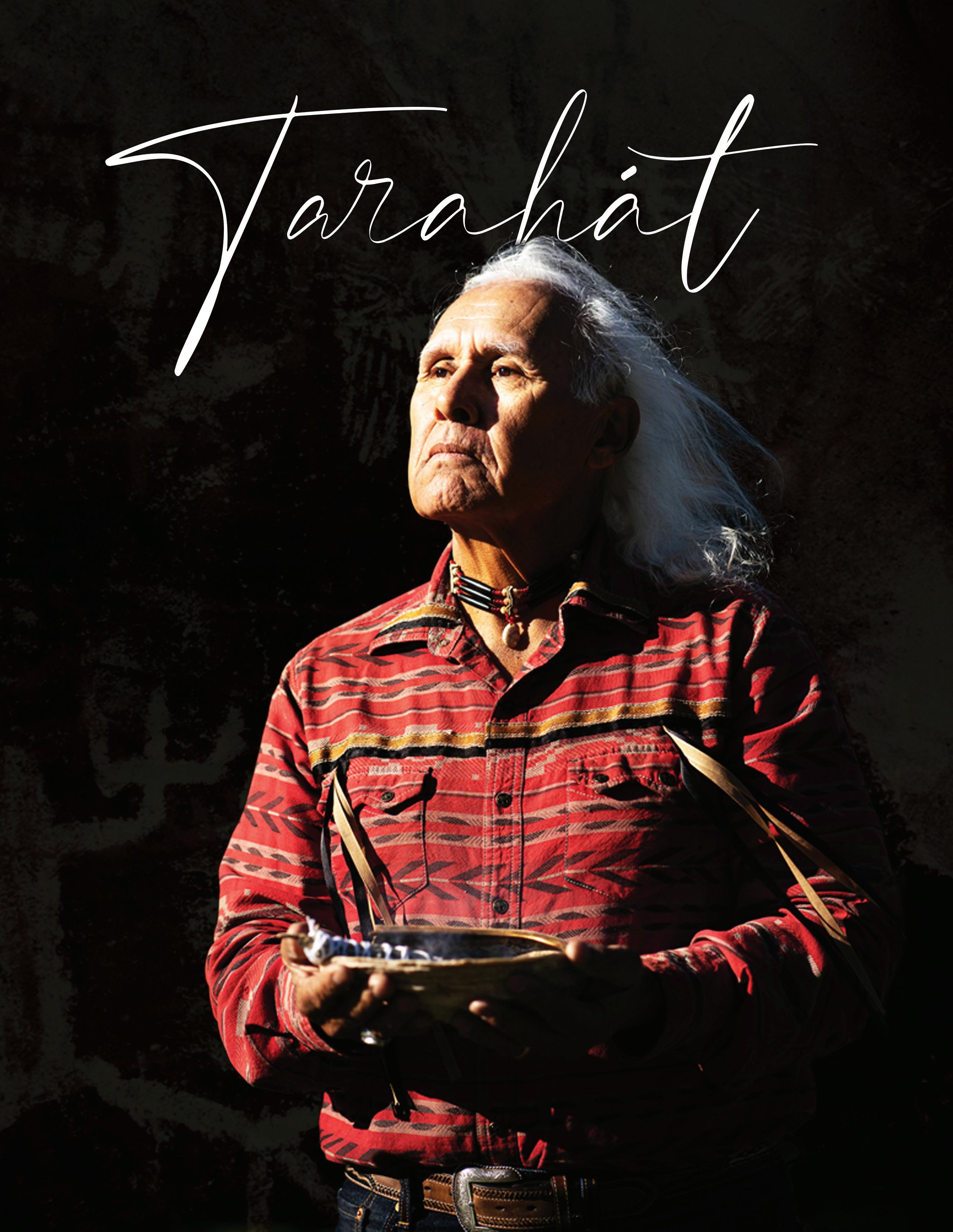

Tarahát (The People) is a bi-annual publication that celebrates and highlights the stories, news, and culture of the Fernandeño Tataviam Band of Mission Indians. Featuring a diverse range of articles, features, and illustrations, this periodical offers a deeper understanding of the Tribe’s heritage, achievements, and contemporary life. With limited print distribution and a digital presence, Tarahát serves as a vital platform for connecting the Tribe’s community members and sharing their rich history with a broader audience.

A Native Sovereign Nation of Northern Los Angeles County with ties to Mission San Fernando and descent from the Simi, Santa Clarita, San Fernando, and Antelope Valleys.

As the President of the Fernandeño Tataviam Band of Mission Indians, I extend my heartfelt gratitude to each of you for taking the time to read our magazine. Though our administration is small, we are indeed mighty, and your interest and engagement mean the world to us.

Through our publication, we aim to share not only our rich history and vibrant stories but also the cultural essence and the challenges and triumphs we experience as a community. The recognition of our Tribe is one of the oldest social justice issues in Los Angeles County, and all too often, we remain invisible.

With this magazine, we hope to shine a light on our existence and experiences, increasing our visibility for the next seven generations. Thank you for joining us on this journey. Together, we can ensure that our voices are heard and our stories are told.

Rudy J. Ortega, Jr., L.H.D.

President

Mark Villaseñor

Vice President

Lucia Alfaro

Secretary

Elisa Ornelas

Treasurer

Joe Bodle

Senator

Richard Ortega

Senator

Jorge Salazar

Senator

Mary Acuña

Senator

Cheryl Martin-Perez

Senator

Jesus Alvarez

Senator

Crystal Crowe

Senator

tarahát magazine

R. Tolteka Cuauhtin

Nahua Xicanx, Vice Chair

Lauren Van Schilfgaarde

Cochiti Pueblo, Secretary

Leon Worden

Treasurer

Mary Acuña

Fernandeño Tataviam

Natalie Bodle

Fernandeño Tataviam

Cathy Salas

Fernandeño Tataviam

Matthew Vasquez

Fernandeño Tataviam

Valerie Vasquez

Fernandeño Tataviam

land conservancy

Jesus Alvarez

Fernandeño Tataviam

President

Lucia Alfaro

Fernandeño Tataviam

Vice President

Sarah Brewer Thompson

Secretary

Rudy J. Ortega, Jr., L.H.D.

Kimia Fatehi

pukúu cultural community services

Samantha Ortega Chair

Katherine Pease

Alan Salazar

Fernandeño Tataviam

Kevin Nuñez

Gabrieleño

Richard Ortega

Fernandeño Tataviam

tïuvac’a’ai tribal conservation corps

Miguel Luna Chair

Rudy J. Ortega, Jr. L.H.D

Fernandeño Tataviam, Vice Chair

Julia Samaniego

Fernandeño Tataviam

Bruce Saito native first lending

Severyn Aszkenazy

Ken Molina

Fernandeño Tataviam,

Elisa Ornelas

Fernandeño Tataviam

Shawn Imitates Dog

Oglala Lakota

paséki strategies

corp

Rudy J. Ortega, Jr. L.H.D

President

Elisa Ornelas

Fernandeño Tataviam, Treasurer

Nicole Raphaely, J.D.

Secretary

Raymond Salas

Fernandeño Tataviam

Nazareth Chobanian

How One Tribal Citizen Uses The Art Of Film To Storytell

Tribal citizen Timothy Ornelas followed his dream. He wants you to know - you can too.

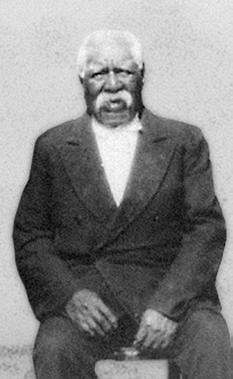

Chances are, if you’ve seen a video or photograph on the Tribe’s website in the last ten years, it was captured by Tribal Citizen Timothy Ornelas, the grandson of Rudy Ortega Sr. Timothy views his role in the Tribe as a storyteller, using the contemporary medium of film to share the narratives of his people. Although he’s usually behind the camera—resulting in few photos of himself in the Tribe’s materials—his work plays a vital role in showcasing the richness of the community and increasing the Tribe’s visibility in Los Angeles County.

The Tribe had the opportunity to interview him this week during his lunch break, of course, proving once again that great stories don’t wait for a convenient time.

Through his unique perspective, Timothy brings the Tribe’s stories to life, creating a visual tapestry that connects everyone. His keen eye not only documents the experiences of the Tribe but also challenges and detaches the community from harmful stereotypes often perpetuated by the film industry. By fostering a deeper understanding of who the Tribe is, he redefines its narrative on his own terms. Through sharing these authentic stories, he strengthens bonds and ensures that the Tribe’s voices resonate within and beyond the community. Plus, if you ever find yourself in front of his lens, just remember: he might capture your best side, but he definitely won’t be in the frame!

Everyday, I’m inspired by the legacy of my Grandfather, Rudy Ortega Sr. “

You were featured by Disney in “Inclusive Storytellers” - how does that feel?

Honestly, it’s been a tough transition for me. My previous work with the Tribe had such a profound impact on our community; every project felt deeply connected to the people I cared about. Now at Disney, I often feel a bit disconnected, and the work doesn’t have the same community impact. Still, I know this journey is important for my own growth, and I hold onto the hope that my presence here can benefit the Tribe in the long run.

Being featured at Disney allows me to reconnect and showcase my Tribe’s name, helping to bridge that gap through events, consultations, and visibility. It’s meaningful to me to uplift the Tribe and represent those of us who come from the land beneath this company office. There are only a few of us here, but together we can make a difference.

Definitely my uncle, Rudy Ortega Jr.. I could expand on him much more. And aside from him, I would say Pamela Peters. She used to work for the Tribe in the past, but outside of my Tribe, she gave me a chance; she reached out and helped lift me up by filming on reservations. That’s what community does—it lifts one another up. But it’s still scary, and I can’t say I’m not afraid.

Growing up, I looked up to my uncle Rudy Ortega Jr., who was making a black-and-white film for his high school class. That was always a moment of awe for me; he was creative and expressed who we are as a Tribe in different ways. This appreciation was instilled in me at a very young age.

School was difficult for me; I was a terrible student and didn’t know how to find myself. I struggled to achieve good grades, and the Tribe’s education program hadn’t quite launched, so I didn’t have access to that support. I felt like a nobody and almost wanted to be one—just to get through school. The Tribe’s scholarship program allowed me to afford my first computer, which helped me flourish my technical interests in video editing and music making. The barrier of “higher education” was daunting, and I fumbled through it.

The Tribe’s scholarships were a game changer for me, enabling me to purchase my first computer. Without that support, I might never have discovered the world of technological arts, which has truly changed my life. Now, as I reflect on my journey, I’m proud to be connected to the LA Native community, filled with joy every time my work is appreciated.

For our Tribe’s Education Department, I set the Youth up to interview one another because I believe that, if we are able and interested, it is our responsibility to respect the voices of our people. I really believe that meaningful listening and respectful engagement is crucial for the preservation of our culture through this craft.

Participating in cultural games like Shinny helped build my confidence, and my cousin, Pamela Villaseñor, introduced me to elder Richard Bugby. I had always struggled to connect with older male figures, but filming and interviewing him created a comfortable space for both of us. Behind the camera, I felt at ease, and Richard’s stories came to life, giving him a voice that resonated deeply within our community.

I hope that my discomfort in life shows that there is a path; it may not be easy, but you should keep pursuing what you want to do. For the Youth in our Tribe, I’m seeing more interest in the arts, and it makes me so happy to see the Tribe giving them space and a platform to grow. I hope to engage with them. And I hope they draw from my mistakes and story.

Growing up, I faced my fair share of challenges, often feeling spread out and not quite fitting in. As a biracial kid, finding my place in the world was tough. But everything shifted when I discovered my passion for film. Thanks to the Tribe, I gained access to a camera that allowed me to authentically document our community, which was a transformative experience.

Nestled in the heart of northern Los Angeles County, the Fernandeño Tataviam Band of Mission Indians carries a profound and enduring legacy that spans millennia. This vibrant community thrived on their ancestral lands for countless generations, cultivating a rich cultural tapestry long before the arrival of Spanish settlers in the late 1770s. With the onset of colonization, followed by Mexican and American rule, the Tribe faced tremendous challenges. Yet, through it all, they have remained unyielding—preserving their sovereignty and unity through a Tribal constitution that reflects their unshakable dedication to protecting both their heritage and autonomy.

The roots of the Fernandeño Tataviam are deeply entwined with the diverse lineages, villages, and cultures that flourished long before the establishment of Mission San Fernando in 1797. In this turbulent era, their ancestors were forcibly renamed “Fernandeño” and endured the grueling hardships of enslavement under Spanish rule. However, the spirit of their people endured, as they were marched across the sprawling Simi, San Fernando, Santa Clarita, and Antelope Valleys—lands that remain a testament to their resilience and strength.

Today, the Tribe stands proudly as a living testament to their history— one defined by perseverance, pride, and an unwavering commitment to a future rooted in self-determination. They continue to advocate for rightful recognition and respect within the ever-evolving narrative of Los Angeles County, ensuring that their profound legacy endures for generations to come. The story of the Fernandeño Tataviam is one of defiance against adversity, a beacon of resilience, and a powerful reminder of the unbreakable bond between a people and their land.

A rebellion amongst the Native Americans at a neighboring mission prompted the Franciscans to establish a new mission between San Gabriel and San Buenaventura, as the distance between the two was so great—over two days’ walk—that many local Native groups managed to evade control. To address this, several expeditions were carried out to find a suitable spot for a new mission, which ultimately led them to the area now known as the San Fernando Valley. There, the site for Mission San Fernando Rey de España was chosen, and on September 8, 1797, the mission was founded, marking a new chapter in California’s colonial history.

Mission San Fernando was like many other missions in California, aimed at converting the Native American tribes to Christianity. However, the impact on the Native peoples, especially the Fernandeños, was profound and enduring. They were forcefully brought to the mission, where they lived under strict rules and harsh discipline from the missionaries. As they were baptized and integrated into mission life, they

began to form a new collective identity, blending their native traditions with the customs and beliefs imposed by the mission system. The Fernandeños were stripped of their cultural practices, forced to speak Spanish, and given Spanish names, all while being pushed to abandon their old ways of life, ultimately suppressing much of their heritage in the process.

The arrival of the Spanish brought with it a deadly new threat: disease. Lacking immunity to smallpox, measles, and influenza, the Native population was vulnerable to the epidemics that quickly swept through the mission communities. The toll was devastating, decimating the Fernandeños and other local tribes. These diseases, along with the upheaval of their way of life, led to a dramatic decline in their numbers. However, the legacy of the Mission System was one of loss—by 1846, fewer than 500 Fernandeños remained, with only about 475 accounted for.

In 1821, Mexico gained independence from Spain, and California transitioned under the jurisdiction of the First Mexican Empire. In 1833, the Mexican government made plans to change how California’s missions worked. The goal was to give mission lands to Native Americans, so they could farm and form their own self-governing communities. However, many of the missionaries, who were mostly Spanish-born, strongly opposed this change. They believed that the Native Americans were key to the region’s economy and feared that freeing them would cause trouble, as they could leave the missions and stop working.

The missionaries argued for a slow transition, while some local Californios wanted quick action, pushing for fast land redistribution, the emancipation of Native Americans, and their integration into Mexican society. They felt the continued control of the missionaries was slowing down progress. With the secularization of the Missions, a pivotal moment emerged for

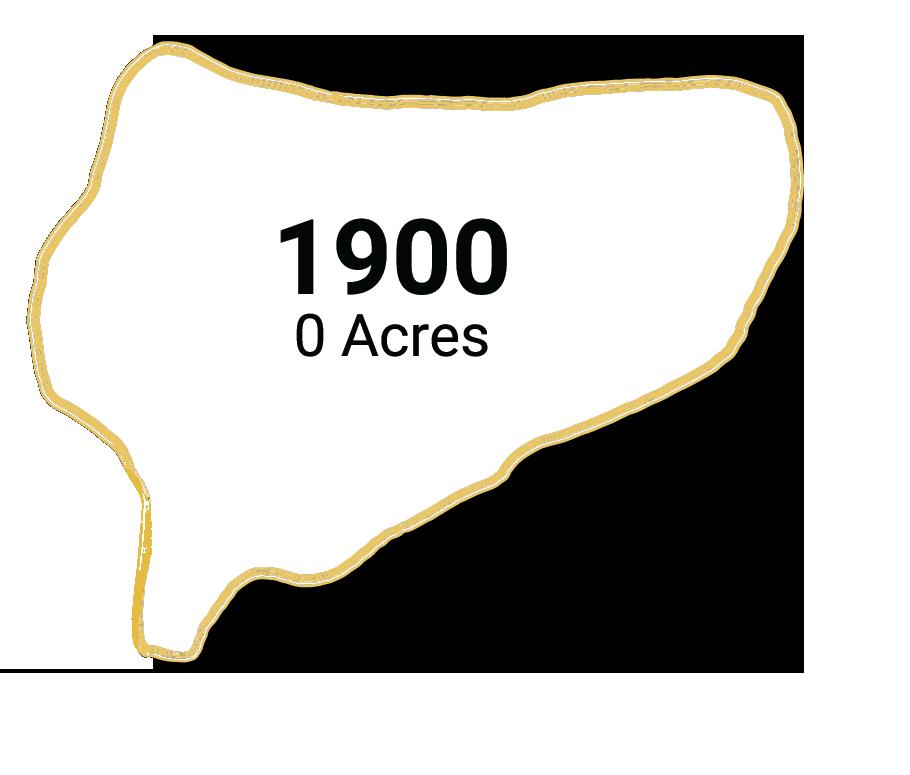

the Fernandeño people. Approximately 50 surviving leaders stepped forward, negotiating for land grants that would secure their community’s future. They successfully acquired over 18,000 acres—about 10% of the San Fernando Valley—held in trust by the Mexican government. This land represented not just property for the collective Tribe, but a chance for the Fernandeños to reclaim their heritage and assert their rights in a changing landscape.

The Fernandeño’s believed that these grants would serve as a foundation for Tribal governance. However, as history would unfold, the challenge of maintaining their legal rights to this land became a crucial part of their ongoing struggle for recognition and survival in the face of new governance. The determination of the Fernandeño leaders during this time laid the groundwork for the Tribe’s enduring legacy and their quest for justice in the years that followed.

Throughout the 1800s, the United States pursued a troubling agenda aimed at eradicating Tribes. During this dark chapter of California’s history, marked by state and federally funded genocide against Native American peoples, the Fernandeños found themselves without U.S. citizenship, yet they bravely fought to defend their lands in local state courts for decades—often to no avail.

In the early years of California’s statehood, the Congress passed the 1851 California Land Act, which exacerbated this injustice by mandating that Native land claims be filed within two years or that the land be transferred to the public domain. This timeline was impossible for the Fernandeño Tribe, whose citizens lacked knowledge

of Western legal systems and often could not read or write English.

As settlers descended on northern Los Angeles County to claim vital water sources, the Fernandeño Tribe lost ownership of the 18,000 acres previously granted by the Mexican government. The evictions prompted Tribal leaders to seek legal assistance, with attorneys commissioned by the federal government stepping in to defend their rights. Notable figures like Assistant United States Attorney G. Wiley Wells and Special Indian Agent Frank D. Lewis worked to secure land for the displaced Fernandeños.

When the Fernandeño Tribe brought suit to regain these lands, the Los Angeles courts (See Porter et al. v. Cota et al.) sided against Native claimants, ensuring that the Fernandeño Tribe could not secure title to lands that would have later become a reservation and federal trust property. The Fernandeño Tribe struggled for decades to defend its lands through state courts, but these efforts were repeatedly thwarted.

By 1900, the Fernandeño Tataviam Band of Mission Indians had been robbed of over one million acres, leaving Tribal families as refugees on their own homeland. Despite these efforts, the historic Fernandeño Tribe was never granted federal recognition, a significant hurdle in their ongoing struggle for land.

Today, the descendants of the historic Fernandeño Tribe number over 900, divided into three surviv ing lineages: Ortega, Garcia, and Ortiz. Each lin eage carries forward the legacy of their ancestors, who held a profound connection to the land.

The Tribe views the lands of Tataveaveat as a sacred cultural space, rich with thousands of years of history, memories, stories, and ancestral lifeways. This deep-rooted significance underscores their ongoing commitment to preserving their heritage and reclaiming their identity in a landscape that remains vital to their culture and existence.

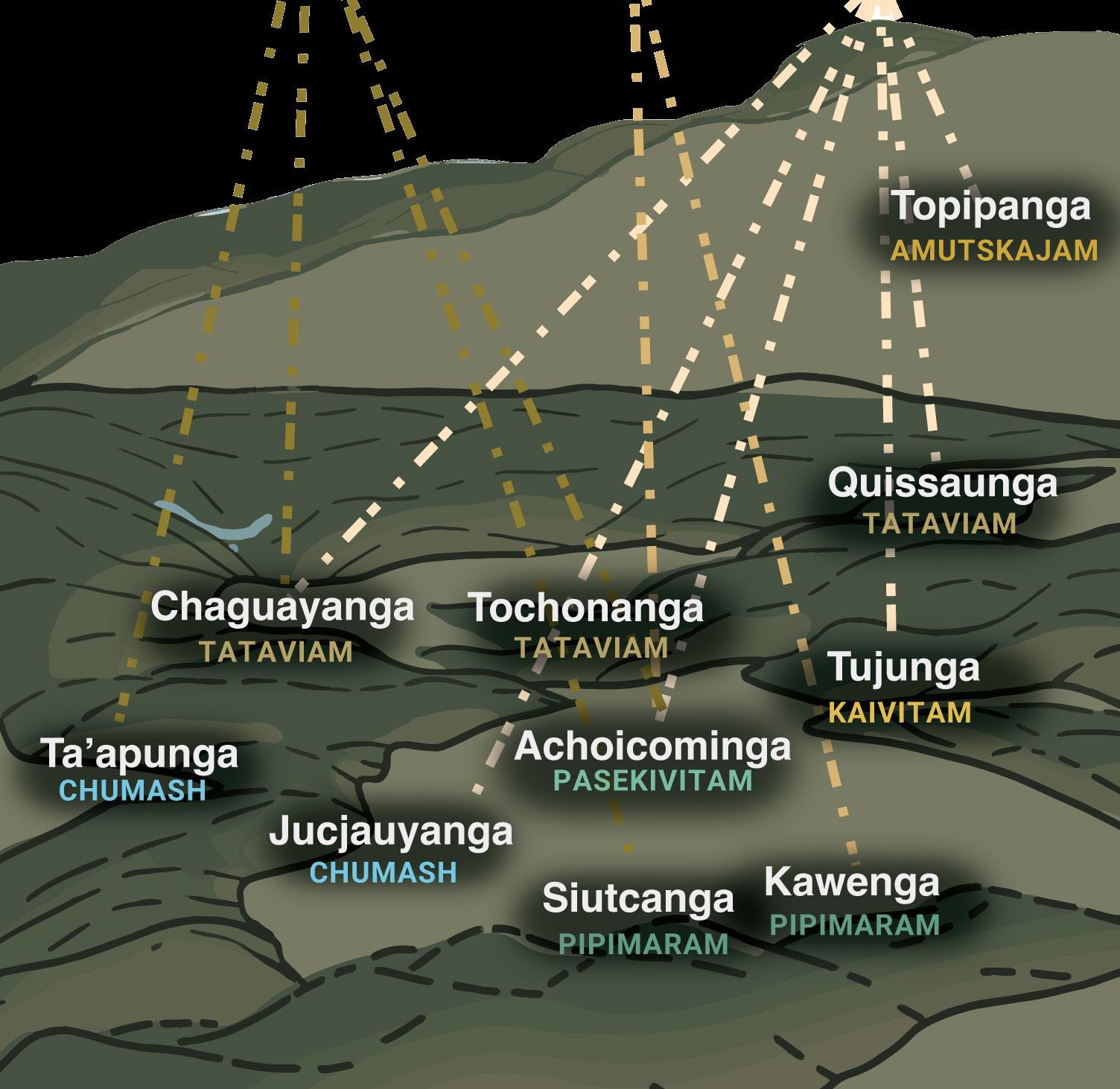

Before settlers arrived, the political system was decentralized, with each village functioning as its own tribe, holding authority over its territory, government, trade, and economy. The idea of a single tribe overseeing all of Los Angeles County is an anthropological myth imposed on the local history.

As described above, there was no tribe above the village because the village was the tribe. However, multiple villages that shared similar belief systems were grouped as “regional groups,” akin to ethnicities. Individuals could belong to several regional groups, but their citizenship was defined by their village.

Each village consisted of one lineage, containing several families with non-voting married-in spouses. Each family selected a Headperson to represent them politically. These Headpersons advised a single Captain who managed the lineage and facilitated negotiations with other Captains to ensure community harmony.

The Official Tribal Boundary delineates the area of enslavement associated with Mission San Fernando, commencing in the year 1797. This boundary encompasses the villages situated within the four distinct ethno-linguistic valleys from which registered Tribal Citizens derive their ancestry.

The Native cultures of Southern California are rich and diverse, with each tribe holding its own vibrant history and traditions. Oversimplifying them into a single narrative erases the complexity and depth that define their identities.

Before settlers arrived, Southern California was home to a fascinating village organization. Unlike many other societies, there was no single leader ruling over all the villages. Each village operated as an independent, self-governing entity, complete with its own leadership structure, cultural practices, economy, and territory. This autonomy allowed each community to thrive in its own way.

To strengthen ties with neighboring villages, village members often practiced exogamy, meaning they married outside their own villages. This practice not only fostered social connections but also encouraged the sharing of languages and dialects, enriching communication among different villages.

Villages were often linked by shared beliefs about the afterlife, forming what the Tribe calls as “regional groups.” For instance, the villages in the Santa Clarita Valley and surrounding mountain ranges were known as the tataviam regional

Following Mission San Fernando Enslavement 1797 - 1846

group. Although each village was sovereign, their common beliefs connected them as a region without superseding each village’s sovereignty.

The name Tataviam comes from “táta’viam,” a term given to those villages by their northern neighboring villages, regionally grouped together as the Kitanemuk. This reflects the interconnectedness of the communities.

The Fernandeño coalition encompasses a variety of regional groups, each with their own identity. Alongside the Tataviam, other groups include the Chumash, Kaivitam, Simivitam, Pasekivitam, Amutskajam, and many more. Each of these groups contributes to the rich heritage of the Fernandeño people, showcasing the complexity and diversity that exist within their shared history.

Understanding and respecting the complexity of Southern California’s cultural landscape is essential. Each community holds unique stories that, when uncovered, reveal the rich identities that define the region. By embracing these stories, we move beyond oversimplified narratives and come to appreciate the vibrant histories that have shaped the present. Today, the Fernandeño Tataviam Band of Mission Indians continues to represent many of these identities, encompassing numerous villages, regional groups, languages, and dialects from these valleys, preserving a legacy that spans generations.

Federal recognition does not grant sovereignty; it acknowledges It.

Since 1843, the Fernandeño Tataviam Band of Mission Indians has pursued recognition from the occupying government—a quest that continues to this day. Under the framework of what is now the U.S. government, tribes must navigate an intricate and often overwhelming process to achieve federal acknowledgment. For the Fernandeño Tataviam, this journey has required more than just paperwork—it has meant facing immense challenges, from proving their historical existence to uncovering long-hidden records that are critical to their claim.

The process of federal recognition places a heavy burden on tribes, demanding an exhaustive collection of evidence to establish their continuous presence and political structure. For the Fernandeño Tataviam, this task was complicated by limited access to crucial historical repositories, many of which were traditionally available only to certain academic experts with the right credentials. Lacking these insiders,

the Tribe was recommended to hire external experts—historians, sociologists, genealogists, attorneys, and researchers—who could navigate these exclusive archives, often seeking out records that had not yet been digitized. Over the years, the Tribe has poured millions of dollars into this exhaustive effort, building an archive of tens of thousands of documents in hopes of proving their place in history. Each document, each piece of evidence, is not just a record of the past, but a symbol of the Tribe’s struggle to reclaim its rightful place in the historical narrative.

While federal recognition does not grant sovereignty, it serves as an acknowledgment of a Tribe’s existence, providing access to vital resources and protections that help sustain their future. However, for the Fernandeño Tataviam, recognition is important, but it is not the ultimate goal. The Tribe has thrived for generations without it, preserving its cultural identity, governance, and community with resilience. Regardless of the outcome, the Fernandeño Tataviam will continue to endure, steadfast in their commitment to their heritage, which, for them, is the true measure of success.

It is a profound irony that we must seek recognition from the very government that once paid for our extermination, all while proving our existence to a state that still has no accurate tax code under which we can operate.

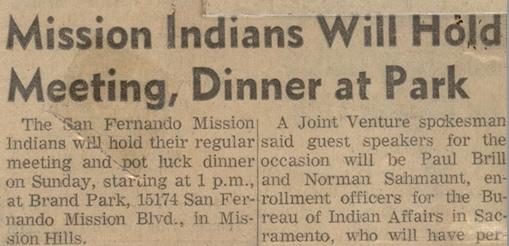

The Tribe has been holding political meetings at Mission San Fernando’s Brand Park since the early 20th Century. As a coalition of three lineages, these gatherings were key for receiving political updates, family news, and celebrating cultural festivities.

The late Tribal President Rudy Ortega Sr. wrote to the federal government seeking land for the Fernandeño people, predating the formal Federal Acknowledgment process that would be established later.

Under Mexican-ruled California in 1843, approximately 50 Fernandeño leaders who survived the Mission system negotiated for village land amounting to over 18,000 acres of the San Fernando Valley for the collective benefit of the Fernandeños.

In October 1892, federally-commissioned attorneys G. Wiley Wells and Frank Lewis represented the Fernandeños, with Lewis addressing the Lake Mohonk Conference of Friends of the Indians to report on the Smiley Commission’s efforts to implement the Mission Indian Act of 1891, acknowledging the Commission’s good work despite ongoing challenges:

“[t]he Indians living on Mexican land grants — particularly those on the Warner’s Ranch, the Santa Ysabel Ranch, the San Felipe Ranch, and the San Fernando Ranch — still faced the possibility of forced removal.”

Of all the tracts listed above, only the San Fernando Ranch was located in a major land boom, making it prohibitively expensive to acquire as a reservation.

1891

In 1995, the Tribe filed a formal letter under the U.S. government’s Branch of Acknowledgment and Research (BAR). By 2009, the Tribe filed a completed petition, and in 2015, the BAR’s successor, the Office of Federal Acknowledgment began reviewing the petition following the Tribe’s decision to proceed under the 2015 regulations.

After withdrawing its petition to clarify its claims regarding the historical Indian tribe from which it descends, the Tribe submitted a new, more concise petition to the Office of Federal Acknowledgment in July 2023.

2023 PETITION:

The struggles of the Fernandeño Tataviam Band of Mission Indians are deeply rooted in a history of land dispossession that began with the Mission System. The consequences of this loss— economic, political, social, and cultural—continue

to reverberate through the community today. Embedded in a society where wealth is tied to land ownership, the Fernandeño Tataviam people’s inability to reclaim their ancestral land has led to significant economic setbacks (continued)

910

TRIBAL CITIZENS

REPRESENTING LESS THAN 0.06% OF LOS ANGELES COUNTY’S RECORDED NATIVE AMERICAN POPULATION.

1 in15

TRIBAL CITIZENS HAS EXPERIENCED HOUSELESSNESS ON THEIR OWN HOMELANDS IN THE LAST 10 YEARS.

1 in2

TRIBAL CITIZENS DOES NOT EARN ENOUGH INCOME TO LIVE IN THEIR HOMELAND OF LOS ANGELES COUNTY.

70%

OF TRIBAL CITIZENS FALL BELOW THE CA SELFSUFFICIENCY STANDARD.

30%

OF TRIBAL CITIZENS HAVE BEEN PUSHED TO NEIGHBORING COUNTIES OR STATES TO AFFORD THE COST OF LIVING

for both the community and its individuals.

Cultural practices are at risk due to non-recognition. Among the nearly 900 members of the Fernandeño Tataviam Band, 16% are elders, yet financial hardships prevent many from passing down their knowledge. The Tribe faces barriers, including restrictions on harvesting sacred plants and the inability to practice their religion freely. Additionally, Fernandeño Tataviam artists cannot legally produce or market their work, as recognition under the Indian Arts and Crafts Act applies only to federally recognized tribes.

tribes.

The lack of federal standing prevents the Fernandeño Tataviam Band from protecting their ancestors’ remains stored in federal institutions. Without

disregard any Tribal consent before excavations.

The Fernandeño Tataviam Band is disproportionately impacted by their inability to intervene in child welfare proceedings. Without federal status, the Tribe lacks the resources to advocate for their children, risking the loss of a child’s self-identity within their homelands.

have severely undermined the Tribe’s ability to build generational wealth.

Non-recognition also impacts the protection of sacred sites. The Tribe is expected to provide expertise on cultural resources without compensation, while private firms profit from similar services. This places an unfair burden on the Fernandeño Tataviam Band, costing them hundreds of thousands of dollars annually due to limited access to grant funding and other resources for federal

recognition, the Tribe cannot access funding to rebury the remains, many of which have been kept on shelves in museums. Ancestral remains cannot be repatriated without the consent of a federal tribe - tribes that may also be inundated and overburdened with requests - despite the fact that archaeological practices

The Fernandeño Tataviam Band of Mission Indians is actively building pathways to healing for its community, focusing on both immediate needs and long-term cultural revival. Through expanded social services, the Tribe is addressing the health, education, and economic wellbeing of its members, ensuring that future generations have the resources they need to thrive. Politically, the Tribe is advocating for greater recognition and policy change, working to influence state laws that impact their sovereignty and the protection of their rights. In parallel, the Tribe is dedicated to cultural revival, restoring traditional

practices and fostering a deep connection to their ancestral heritage. Together, these efforts are creating a foundation for healing, empowerment, and resilience, helping the Fernandeño Tataviam Band of Mission Indians reclaim their place in history while securing a

vibrant future for generations to come.

The tremors of land theft can still be felt today.

The Fernandeño Tataviam Band of Mission Indians has long exemplified resilience and self-reliance, deeply rooted in a profound understanding of

their identity and obligations to the community. As part of their ongoing pathway to healing, the Tribe has consistently focused on strengthening its social services, political advocacy, and cultural revival. Historic leaders, recognizing that federal recognition was not the sole key to sovereignty, understood it as their responsibility to secure the future of the Tribe.

In the 1960s, they established proactive measures to ensure the well-being of their citizens, founding an entity outside the Tribal government to minimize tax burdens. This visionary approach laid the groundwork for Pukúu Cultural Community Services in 1971, which became a lifeline for support, providing initiatives such as toy drives, scholarships, and seas0nal

celebrations to uplift all Native American families that call Los Angeles home.

Building on this legacy, the Tribe has expanded its efforts with additional non-profits and for-profit enterprises, securing land, creating workforce opportunities, and continuing to promote self-sufficiency and economic growth. Today, these

ongoing efforts remain essential as the Fernandeño Tataviam works to heal historic wounds, advocate for their rights, and revive their cultural heritage for future generations. By reinforcing the strength of their community and their culture, the Tribe is creating pathways to healing that will empower their people for years to come.

Before colonization, Native Americans were deeply connected to the villages where they were born, each serving as a sovereign, state-like entity. These vibrant communities governed themselves with their own territories, laws, and systems for resolving disputes. At the heart of each village was a captain, a leader responsible for overseeing their lineage and negotiating with other captains to maintain harmony and balance.

Leadership wasn’t just a title; it was earned

When the Spanish enslaved the villages at Mission San Fernando, the lives of the Native Americans underwent a dramatic transformation. This marked the emergence of a new centralized political system and economy among the Fernandeños, while still allowing their distinct village identities to persist. The friars noted in their diaries that the Fernandeños were more likely to listen to their own people, which led them to elect annual representatives called “alcaldes” to handle their affairs with the Mission. However, these representatives had no real legal status or power within the Spanish government.

Today, the practice of lineage Headpersons

through exceptional knowledge of history, culture, and ceremonies, often passed down through hereditary lines. This rich tapestry of governance meant that before colonization, dozens of captains coexisted across the San Fernando, Simi, Santa Clarita, and Antelope Valleys, each contributing to a dynamic and interconnected network of communities. This system fostered cooperation, cultural richness, and a deep-rooted sense of identity long before outside forces disrupted their way of life.

remains strong. In addition to these hereditary roles, lineages appoint a Captain of the Tribe and hold elections for the Tribal President, maintaining a connection to traditional governance. Much like in the past, these leaders organize the community for the collective benefit of their families and all citizens. While the Tribal constitution guides elections, traditional lineage and family ties continue to shape leadership and decisionmaking. Each lineage retains significant political and social autonomy, ensuring that leaders respect the individual and collective autonomy of families and lineages as they navigate the complexities of governance.

DESPITE CENTURIES OF DISCRIMINATION, THE FTBMI RETAINED ITS TRADITION OF SELF-GOVERNANCE. THE TRIBE IS GOVERNED BY TWO BRANCHES, EACH WITH THE RESPONSIBILITY TO DEFEND THE FTBMI CONSTITUTION AND RIGHTS OF ALL FERNANDEÑO TATAVIAM PEOPLE.

In order to be eligible to vote or file for candidacy with the Fernandeño Tataviam Band of Mission Indians Elections, you must be:

01 An enrolled Tribal Citizen

02 18+ years of age

How One Fernandeño Elder Has Spent Decades Revitalizing Traditional Canoeing

Photo By Diego Huerta

“I realized, very early on, that in order for me to survive, I cannot be obsessed with what’s fair and unfair. It will eat you up and destroy you.”

Alan Salazar is no stranger to the deep waters of history. A respected Elder of the Fernandeño Tataviam Band of Mission Indians, Salazar has spent decades not only reflecting on his heritage but actively working to revive it. Now in his seventies, his commitment to preserving his people’s cultural legacy is more urgent than ever, driven by a personal connection to a centuriesold tradition: the construction and crossing of tomols, the traditional Chumash plank canoes. For Salazar, these canoes are not just vessels; they are living symbols of his ancestors’ resilience, ingenuity, and enduring connection to the land and sea. Each crossing on the open water is a profound link between the past and the present, a moment that binds three generations of his family.

For over 25 years, Salazar has dedicated himself to reviving this ancient craft—building traditional tomol and tsá’atsh, the Fernandeño canoe. These meticulously crafted boats, some up to 30 feet long, were once essential to the Chumash people’s coastal way of life, allowing them to navigate the Channel Islands and the waters of Southern California. The canoes were integral to the Chumash’s expansive trade network, connecting villages across the region and fostering economic and cultural exchange. But Salazar’s work goes beyond canoe-building. It’s about the survival of an identity—a resurgence of cultural pride that

tsá’atsh

TRANSLATION: “BOAT”

was nearly lost during the era of the Spanish missions. His ancestors, some of whom Chumash, were forcibly displaced by the enslavement at Mission San Fernando, were later known as the Fernandeño.

The importance of the tomol extends beyond its practical use. For Salazar, it’s a direct link to his roots in the San Fernando, Santa Clarita, and Simi Valley regions. His family’s ancestral lands stretch to Ta’apu (now Tapo Canyon), where his0 Chumash forebears lived for centuries before the disruptions of colonialism. By reviving the canoebuilding tradition, Salazar is reconnecting with those lost connections, strengthening his own identity and reinforcing the cultural legacy of his people.

Through his efforts, Salazar is also teaching the next generation of Native people about the tomol’s cultural significance. His workshops are places of collaboration, where experienced artisans mentor eager apprentices. Together, they select the best materials—often seeking out the rare

and high-quality redwood essential for building the canoes—and perfect the complex techniques required for shaping and assembling them.

Salazar’s teaching philosophy is simple yet profound: this knowledge must be passed down. He believes that for his community to thrive, young people must know and understand their heritage—not just as a concept, but as a living, breathing tradition that can be practiced and preserved.

Salazar’s work is not done in isolation. He’s received invaluable support from Patagonia, which has provided workspace, funding, and resources for the construction of two new tomols.

My hope and dream is that our young ones take this over; that they use these tools to become future paddlers... I’d die a happy man.

Alan

Salazar, FTBMI Citizen

Additionally, Patagonia is producing a documentary titled Chumash Powered, which will showcase Salazar’s work and the cultural revival taking place.

But even with this support, Salazar faces challenges. Sourcing quality redwood, a key material for building the canoes, has proven difficult. He estimates it will take about eight months to complete the new canoes, a labor-intensive process requiring not only skill but patience. The delays are frustrating, but Salazar’s outlook remains steady. As he puts it, “I realized very early on that, in order to survive, I cannot be obsessed with what’s fair and unfair. It will eat you up and destroy you.” His resilience, shaped by years of working to rebuild his community’s heritage, fuels his determination.

Salazar’s work is about more than simply building canoes; it’s about reshaping the future of his people. By educating and mentoring younger tribal members, he ensures that this craft— and the cultural knowledge behind it— will endure for generations to come. Through workshops, apprenticeships, and documentation, Salazar is creating a new generation of Native artisans who will continue the tradition long after he’s gone. For him, the tomol is not just a canoe—it’s a symbol of survival, a symbol of pride, and above all, a symbol of home.

To support this project, please connect with the Tribe’s Tataviam Land Conservancy.

On November 8, 2024, the Tribe’s historic non-profit Pukúu Cultural Community Services celebrated another year of community service! The 20th Annual Night with the Stars gala was a night full of celebration, music and honoring.

The 1st Annual Night with the Stars Gala took place in 2004. With support from the Los Angeles City/County Native American Indian Commission and American Indian Tribes from Southern California, the Gala raised scholarship dollars for American Indian college students. The magical evening is filled with live American Indian entertainers and cultural bearers. Through this annual gala, Pukúu raises funds to provide scholarships for students working towards attaining a higher education.

This year, Pukúu honored Los Angeles City Councilmember Monica Rodriguez and the founding member and bassist of the Native American rock group Redbone, Pat Vegas, for their committment to the Native community. Additionally, Pukúu provided thousands of dollars in scholarships to Native students through three scholarship funds: the Tomiar Rudy Ortega Sr. Scholarship, Cultural Defender Caitlin Gulley Memorial Scholarship established by FivePoint, and the Tribal Senator Austin Martin Memorial Scholarship established by the Martin Family.

To support this work, please connect with Pukúu Cultural Community Services.

SERVING NATIVE AMERICAN YOUTH

RESIDING IN NORTHERN LOS ANGELES COUNTY.

The Tribe’s Native Youth Football Day Camp, in partnership with Robert Judkins’ nonprofit IDEA (Indigenous Dominance in Education and Athletics) and the Los Angeles Rams Football Development, is a vital initiative aimed at empowering Tribal youth in the Los Angeles area. By establishing a youth flag football league specifically for Native children, this program not only promotes athletic skills but also strengthens community ties and cultural identity. Access to sports is essential for Tribal youth, offering them opportunities for personal growth, teamwork, and leadership while fostering a sense of belonging.

The day begins with team warm-ups, skill-building drills, an obstacle course, and a demo tryout of flag football, providing participants with a well-rounded introduction to the sport. Additionally, families learn about the importance of on-field safety protocols, ensuring that young athletes understand how to protect themselves while enjoying sports. The program also highlights potential career paths for youth in athletics and encourages parents and high school students to consider becoming coaches for the flag football league in the valley. This focus on education and mentorship (continued)

reinforces the camp’s commitment to community involvement and personal development.

The initiative’s commitment to creating an allgirls flag football league further underscores its dedication to inclusivity and empowerment. By providing a platform for female athletes, the camp helps to break down stereotypes and encourages young women to pursue their passion for sports. Beyond physical training, the program emphasizes the importance of a supportive environment for young athletes, ensuring they have the opportunities and resources necessary to thrive

in their communities and beyond. By facilitating access to sports and fostering leadership, the Youth Football Day Camp plays a critical role in nurturing the next generation of Tribal leaders.

Join the Tribe’s Education and Cultural Learning Department to engage in enriching leadership programs.

MANAGING PROGRAMS AND INITIATIVES RELATED TO THE MENTAL, PHYSICAL, AND COMMUNITY HEALTH OF THE FERNANDEÑO TATAVIAM.

When the ancestors were buried, their DNA became part of the soil that enriched the syutka for thousands of years.

Syutka is the Fernandeño Tataviam word for the coast live oak, a native, droughtresistant evergreen tree integral to the culture and sustenance of Southern California’s Native

peoples. Known for producing acorns, a vital food source for both humans and wildlife, the syutka plays a crucial role in the local ecosystem. The Fernandeño Tataviam refer to

acorns as wihuc, with one of the most cherished traditional dishes being wiich, a thick acorn soup. This culinary staple reflects the deep connection the community has with their

natural environment.

The syutka is distinguished by its unique ability to retain acorns longer than other California oaks. While most acorns fall in the autumn, some stay

The Acorn Program is Grounded by Traditional Knowledge and establishes an opportunity for Tribal Citizens to cook contemporary cuisine with historic flavors.

attached through the winter and into spring, providing vital nourishment to surrounding life. This adaptation enhances the dispersal of acorns, fostering biodiversity in the region.

For centuries, California Native peoples have perfected methods for gathering acorns from the syutka, turning them into a nutritious flour that forms the basis of many traditional dishes. Acorns remain a cherished part of Native diets, symbolizing both sustenance and cultural significance.

The syutka is not only a source of nourishment but also a place for gathering. It provides vital shade where acorns are processed and community activities take place. The Fernandeño Tataviam honor the tree’s vital role in their lives and encourage the community to treat it with reverence.

Join the Tribe’s Education and Cultural Learning Department to engage in enriching acorn-focused programs that connect you to tradition and culture.

CULTURAL PRESERVATION

PROVIDING SERVICES FOR THE MITIGATION OF ADVERSE EFFECTS TO NATURAL AND HUMAN ENVIRONMENTS.

MITIGATING ADVERSE EFFECTS TO HISTORIC RESOURCES, INCLUDING TRIBAL RANCHERIAS, CEMETERIES, AND STRUCTURES.

MITIGATING ADVERSE EFFECTS OT THE HUMAN ENVIRONMENT, INCLUDING CULTURAL ARTIFACTS, SITES, AND LANDSCAPES.

MITIGATING ADVERSE EFFECTS TO THE NATURAL ENVIRONMENT, INCLUDING CLIMATE, PLANTS, WATER, AND WILDLIFE.

First Tribal Blueprint in LA County

As global temperatures rise and the damage to land, water, and life continues to threaten selfdetermination, traditional ways of life and practices, the Fernandeño Tataviam Band of Mission Indians is using traditional ecological knowledge and science jointly to address climaterelated hazards.

“Our vision is that Tribal citizens and leaders in partnership with allies can work collaboratively to stabilize our lands towards restoration and vibrant communities where we can nurture our children in a land that has abundant clean water, thriving forests, clean air, urban communities cooled by trees and open green space, and restored rivers and tributaries.”, said Rudy Ortega Jr., Tribal President.

The Plan’s recommendations propose to position the Tribe to invest in actions that will mitigate extreme heat, wildfire,

flooding, and challenges to the Tribe’s energy systems by using traditional ecological knowledge and the best available science and data.

The recommendations in this report seek to strengthen the Tribes’ cultural identity, promote its economic prosperity, while honoring their ancestors as they forge a path towards a climateresilient future by applying their traditional ecological knowledge and history combined with new data and modern science for solutions across their Tribal lands and the region.

The Plan was made possible with a grant from the Bay Area Council, Climate Resilience Challenge Program. The development of the plan was led by the FTBMI over 18 months in collaboration with a team of partners that included environmental organizations and academia; Climate Resolve, Council for Watershed Health, and UC Riverside-CCERT.

Engage with the Tribe’s Environmental Protection Division within the Tribal Historic and Cultural Preservation Department to learn more.

The Eastern San Fernando Valley and Central Antelope Valley have many disadvantaged neighborhoods, especially in central Lancaster and throughout the San Fernando Valley. These areas struggle with both low income and high heat risks, shown in red and orange on the map. Because of this, they need to be prioritized for planning against extreme heat within the FTBMI Tribal Territory.

In the FTBMI Tribal Territory, 12% of neighborhoods have high levels of harmful tiny particles, mostly in the Western San Fernando Valley, which also has many really hot days. Additionally, over 89% of neighborhoods have high ozone levels, especially in areas away from the western parts like the Santa Monica Mountains and Lake Piru.

Southern California’s warm climate is becoming more dangerous because of rising temperatures from climate change, which creates serious health risks. Extreme heat can lead to more heart problems, like heart attacks and strokes, because it makes the body work harder. In the FTBMI Tribal Territory, about 24% of neighborhoods have high rates of heart disease.

Climate Change is a threat to Native culture & life.

The Fernandeño Tataviam Band of Mission Indians successfully urged President Biden to advance the expansion of the San Gabriel Mountains National Monument to include an additional 109,000 acres.

In the vibrant landscape of Southern California, where the vast sprawl of Los Angeles meets the rugged majesty of the San Gabriel Mountains, a significant new chapter in conservation is unfolding. Under the leadership of President Biden, the San Gabriel Mountains National Monument—first designated by President Obama in 2014—is set to grow by more than 105,000 acres. This expansion not only safeguards the breathtaking natural beauty of the region but also honors the deep cultural heritage that has flourished here for centuries. (continued)

The expansion of the San Gabriel Mountains National Monument is a significant step toward preserving not only the region’s natural beauty but also its deep cultural and historical heritage. Among the newly protected lands is a site of great importance to the Fernandeño people and other Tribal communities across Southern California. This includes the location of an ancient and sacred site tied to the Fernandeño story of *tújú*—the tale of the old woman who, after a long life of wisdom and hardship, transformed into stone on a hillside facing the San Fernando Valley. For generations, this site has served as a pilgrimage destination for Tribal peoples, a place where stories and traditions are passed down and

where the land itself holds the memory of their ancestors.

In addition to preserving this sacred cultural site, the expansion also includes a place of deep historical significance—the deportation site of the Fernandeño people. In a tragic chapter of California’s past, a former state senator, backed by a land developer, forcibly evicted the Fernandeños from their homeland in San Fernando. Captain Rogerio Rocha, an 80-year-old Fernandeño elder, was among those displaced and tragically abandoned at the end of Lopez Canyon, where he passed away shortly thereafter. By incorporating this deportation site into the expanded

monument, the government acknowledges the pain and suffering endured by the Fernandeño people and honors their enduring connection to this land.

The expansion goes beyond historical recognition. It ensures equitable access to nature, safeguards critical drinking water sources for Los Angeles County, and plays a crucial role in addressing the climate and biodiversity crises. Furthermore, it aligns with the state and federal goal of protecting 30% of U.S. lands and coastal waters by 2030.

Ultimately, the expansion of the San Gabriel Mountains National Monument is a commitment

to protecting both the cultural and ecological integrity of this remarkable landscape. It serves as a living tribute to the resilience and history of the Indigenous peoples who have long cared for these lands, ensuring that their legacy and the natural beauty of the region are preserved for future generations.

Engage with the Tribe’s Cultural Resources Management Division within the Tribal Historic and Cultural Preservation Department to learn more.

PROCESSING APPLICATIONS FOR TRIBAL CITIZENSHIP PURSUANT TO THE PROVISIONS OF THE FERNANDEÑO TATAVIAM CONSTITUTION AND LAWS.

The Fernandeño Tataviam Band of Mission Indians is committed to the protection and preservation of its heritage and communit. The Tribal Citizenship process enables individuals of Fernandeño Tataviam descent to register with the Office of Tribal Citizenship, thereby securing their representation within the Tribal government. The Tribal Senate plays an essential role in issuing permanent citizenship records, formally recognizing each individual’s identity and rights within the Tribe.

Tribal I.D. Cards

Verification of Tribal Enrollment

Declaration of Candidacy

Tribal Election Voter Registration

Adult & Minor

Enrollment

Citizen Updates

Make an appointment with the Office of Tribal Citizenship for further assistance.

OFFICE OF TRIBAL PRESIDENT STRATEGIC PLANNING AND EXECUTING THE SPECIAL PROJECTS THAT UPLIFT THE FTBMI.

In an exciting development, California State Parks and the Fernandeño Tataviam Band of Mission Indians have formalized a groundbreaking agreement to collaborate on the management and protection of natural and cultural resources within the Tribe’s ancestral lands. This partnership will not only enhance the interpretation of state parks, including the significant Village of Siutcanga, but will also incorporate traditional ecological knowledge into natural resource management and landscape protection.

The memorandum of understanding was signed at Siutcanga—known today as Los Encinos State Historic Park in Encino, California. This site holds deep cultural significance for the Tribe, with over 70% of its citizens tracing their lineage back to this village.

Connect with the Office of Tribal President to engage in meaningful consultation.

Native American Conservation Corps in Los Angeles County.

The Tiüvac’a’ai Tribal Conservation Corps’ hands-on training program will work with Indigenous youth and young adults towards the goals of regaining ecological functionality, enhancing climate resiliency and human well-being.

Paséki Strategies Corporation is not just another renewable energy company; it embodies the spirit of stewardship for the land and the community it serves. Founded on principles of sustainability and collective growth, Paséki has emerged as a leader in the renewable solutions sector, driven by an unwavering commitment to the environment and the people.

The journey of Paséki began with the ambitious conversation between Tribal President Rudy Ortega Jr. and then-Tribal Senator Raymond Salas. Together, they laid the groundwork for what

would become a flourishing renewable energy enterprise. Initially focused on revenue generation for investment, the company recognized a burgeoning opportunity in the renewable energy market. This foresight positioned Paséki to pivot towards innovative solutions that align with the increasing global demand for sustainable energy.

The driving force behind Paséki is its co-founder, a seasoned businessman whose diverse career spans from real estate to renewable energy. With 15 years of experience as a realtor, Raymond Salas has engaged in every type of transaction,

from residential properties to large commercial deals. His multifaceted background has equipped him with the necessary skills to navigate the complexities of business within the renewable sector. “It made sense to bring my experience into the tribe,” he states, highlighting the synergy between his career trajectory and Paseki’s mission.

A core philosophy at Paséki is resilience. Salas emphasizes that success is a marathon, requiring persistence and dedication. “Staying true to your path will lead to opportunities,” he asserts, drawing parallels between personal and professional journeys. This ethos resonates deeply within the Tribal community, where perseverance and hard work are ingrained values. The metaphor of “tilling and seeding until the fruit comes” captures the essence of their commitment to growth, both individually and collectively.

opportunities for others. The company is not just building a renewable energy enterprise; it is cultivating a thriving ecosystem where every Tribal Citizen has the chance to grow, contribute, and excel. In a world where traditional corporate ladders can hinder progress, Paséki stands out as a beacon of hope and opportunity for those willing to work together for a sustainable future.

UPLIFTING ALL NATIVES WITH US AS WE MOVE FORWARD

In conclusion, Paséki Strategies Corporation represents a forwardthinking model in renewable energy, rooted in community and environmental stewardship. With a focus on collaboration, resilience, and inclusivity, Paseki is not just paving the way for sustainable energy solutions but is also redefining what it means to succeed in business.

Connect with Paséki Strategies Corporation for renewable energy opportunities.

Paséki is not just about business; it’s about nurturing relationships and fostering an inclusive environment. The company’s unique approach sets it apart in Los Angeles, home to a vibrant Native American population. Paseki actively seeks to uplift those around them, creating pathways for collaboration and shared success. “We aim to bring everyone with us as we move forward,” the founder emphasizes, underlining a commitment to inclusivity that is often lacking in corporate America.

As Paséki continues to grow, its mission remains steadfast: to replicate success and create

Land is at the core of our identity as a village-based people.

One day, an elder, his body marked with cuts and bruises, walked into the Tribal Administration. When asked what happened, he simply said, ‘I gathered some medicine on the side of a hill off the freeway this morning and lost my balance.’ In that moment, President Ortega Jr. made it his mission to secure land for the Tribe.

For the Fernandeño Tataviam, land is integral to their identity. As a landless tribe without federal recognition, their ancestral connection has long been elusive.

In response, they established the Tataviam Land Conservancy in 2018, a groundbreaking initiative that marks the first of its kind in Los Angeles County. This conservancy allows the Tribe to reclaim their heritage by overseeing land that can serve cultural, ceremonial, and ecological purposes.

The Tataviam Land Conservancy reflects a unique perspective on conservation, one that prioritizes Tribal values over conventional environmentalist views. For the Fernandeño Tataviam, conservation is about preserving spaces for cultural continuity and maintaining privacy essential for traditional practices. This initiative not only seeks to acquire land but also emphasizes the importance of stewardship, allowing their People to reconnect with their ancestral ways.

Through this innovative mechanism, the Tribe is taking significant strides toward restoring their homelands on their own terms.

Connect with the Tataviam Land Conservancy for land donation opportunities.

Attended by over 10,000 visitors from across the country.

The 30th Annual Pow Wow, held at Tochonanga, the traditional name for Hart Park in Newhall, CA, attracted over 10,000 attendees celebrating Native American culture and traditions. The event featured vibrant dance competitions, craft vendors, and traditional foods, showcasing the rich heritage of

Native communities. Attendees enjoyed performances from various tribes, along with educational demonstrations about cultural practices, music, and art, fostering a deeper understanding and appreciation of the diverse Native American cultures.

The Fernandeño Tataviam Band of Mission Indians, in collaboration with the County of Los Angeles Department of Parks and Recreation and Friends of the Hart Park Museum, coordinates this event. Its success is made possible through the generous support of our sponsors and the community.

In the heart of Tochonanga, where the vibrant spirit of community pulses through the air, the annual pow wow draws together families whose roots trace back generations—approximately 70% of the FTBMI proudly descends from this historic village. For over thirty years, these families have gathered to celebrate their rich heritage, making this event not just a celebration, but a cherished homecoming for all who share in its legacy.

The 5 main things you’ll want to remember

• Powwows are deeply rooted in Native American cultural and spiritual traditions. Please respect the Elders and all participants. Listen to the Arena Director for photography instructions.

• Traditional regalia worn at powwows is sacred and meaningful, representing the individual’s heritage and tribe.

• Only those invited to dance or perform should take part in the grand entry, dances, or other specific rituals.

• Powwow grounds are considered sacred. Attendees are expected to maintain reverence, keep noise to a minimum when not participating, and avoid crossing the dance floor or interrupting ceremonies.

• Learn at least one fact about the hosting Tribe.