Cornell University

B.Arch Thesis

May 2024

Cornell University

B.Arch Thesis

May 2024

LUBEN DIMCHEFF

ERIN PELLEGRINO

The greatest part of experiencing a space is thinking about the memory of a space after being no longer in it. What’s left is a faded image of an experience I once had. Does the space exist anymore now that I am not in it to see and experience it? Isn’t memory the only reality when space ceases to exist in the physical world and continues to evolve in the mind?

Baruch Spinoza’s theory of one substance suggests that all physical substance is part of a network of cosmic webs that is non-hierarchical in essence: we are distributed minds made up of an infinite number of interactions and generations.

Body and mind are the two attributes of cosmos that is required for memory to form. Memory is an activity of extension and thought. Extension responds to motion constituting material bodies, while thought amounts to information constituting immaterial ideas.

We have our seas, inside sun

We have our tress, inside leaf

Morning till night, we go and go, back and forth

Between our seas and our trees

Inside nothingness

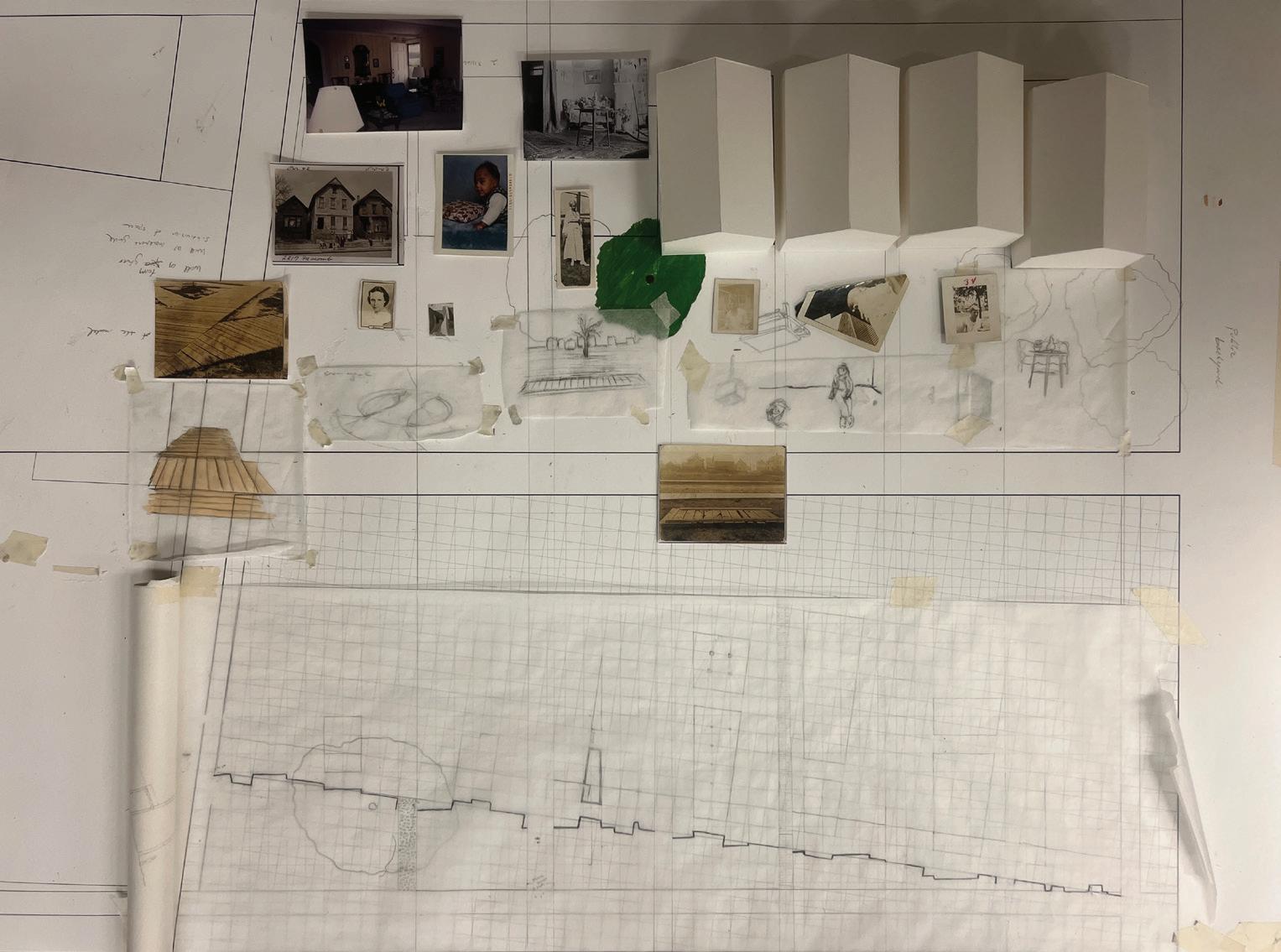

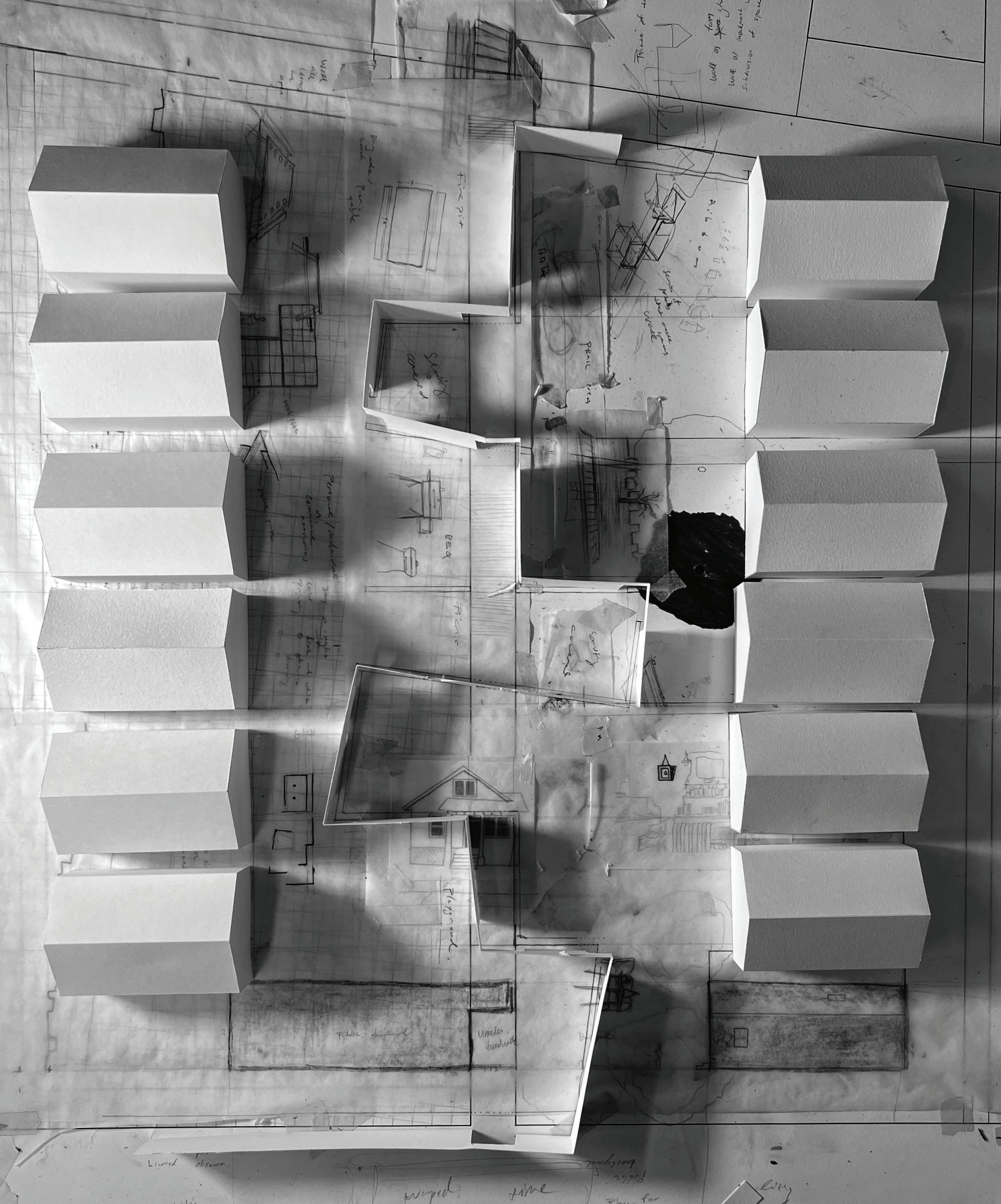

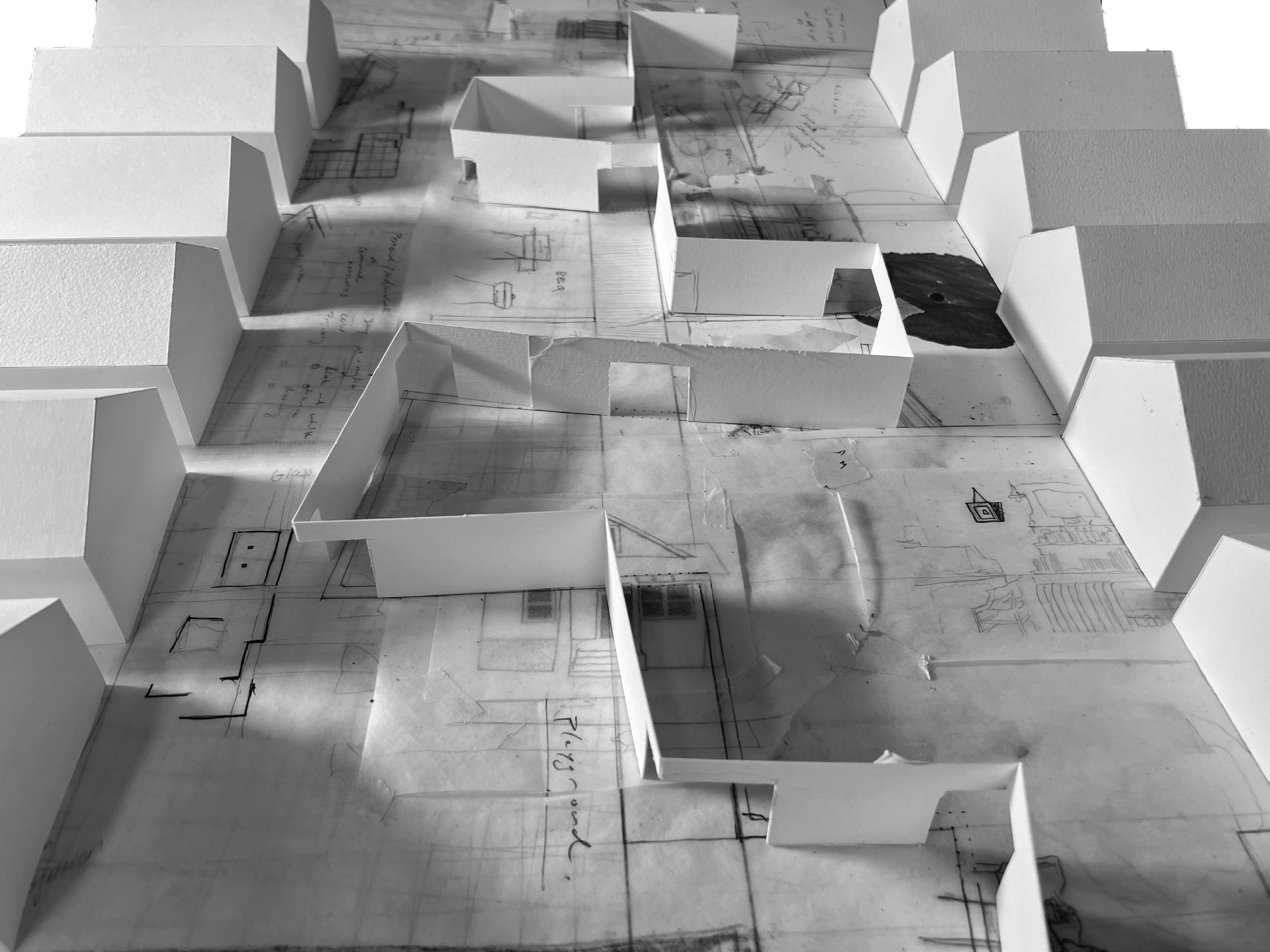

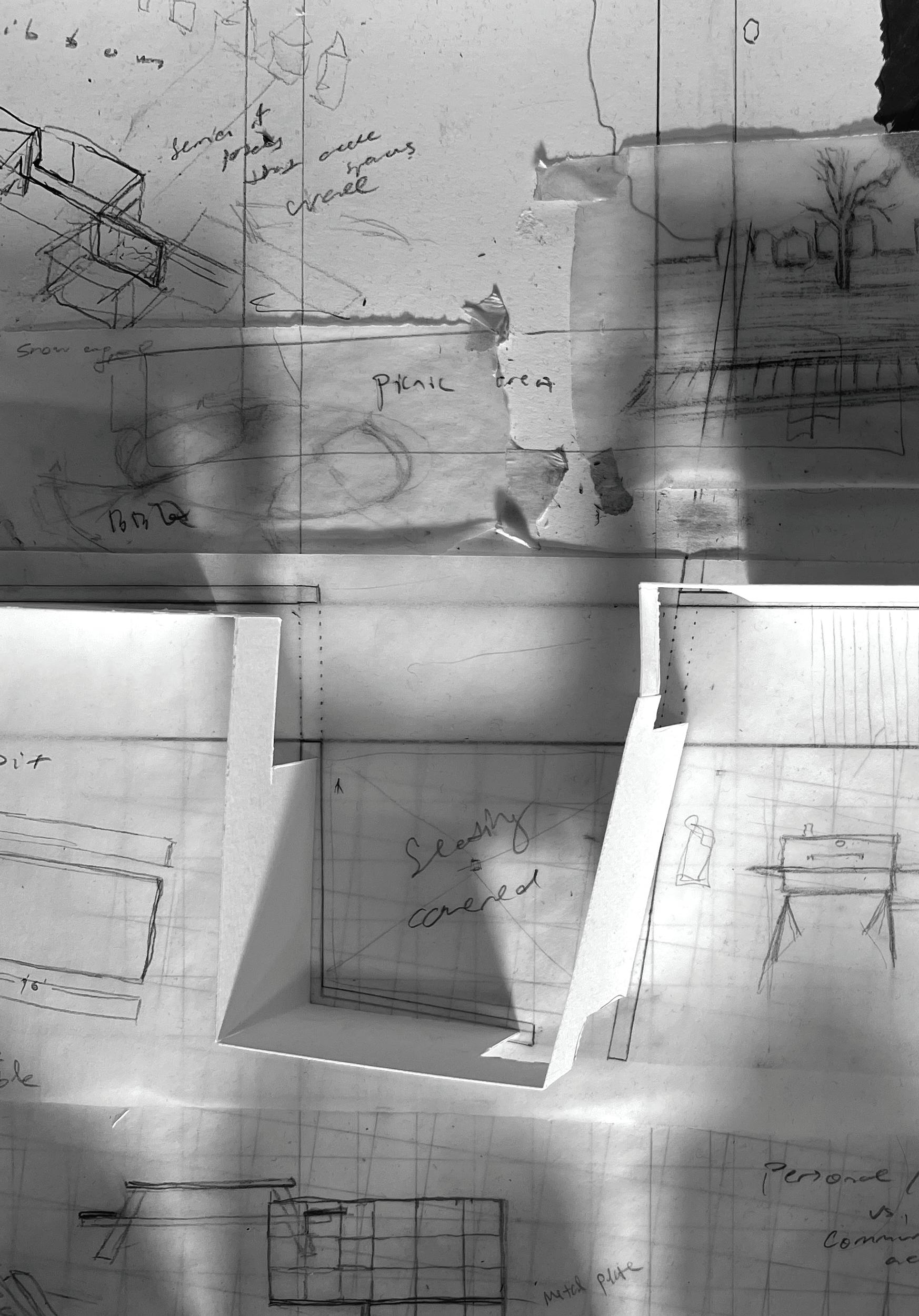

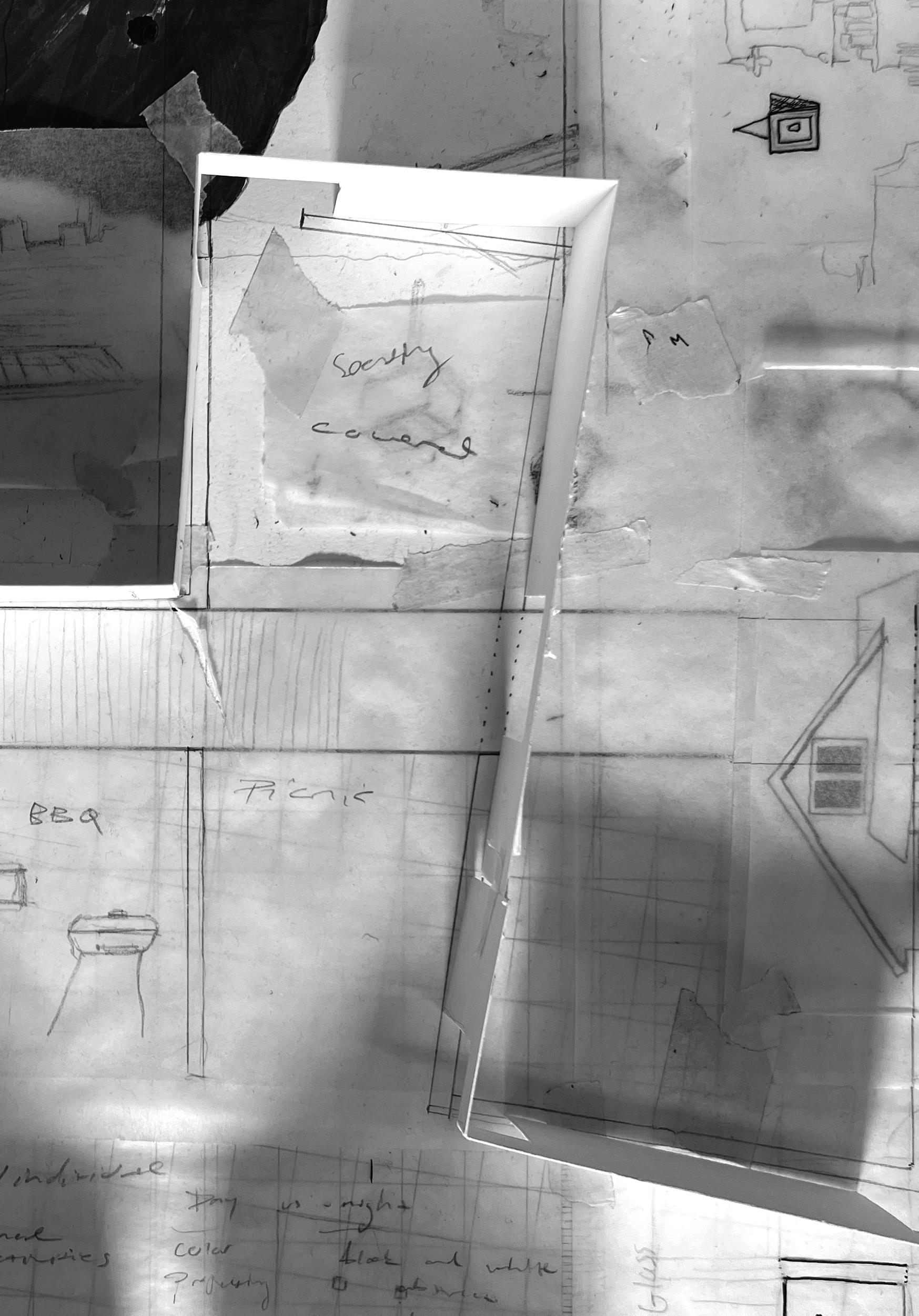

This thesis experiments with a constructed methodology that challenges canonical understandings of architecture, which limit the discipline’s boundaries within its own entity, by integrating the photograph to the traditional tools of drawing and model.

Self-isolation is a critical part of thinking in architecture. When beginning any architectural project, the architect is expected to zoom out, and take almost a godly stance as it carefully dissects, analyzes and interprets layers of information from the context, not dissimilar to a maestro. The site is the essence of these studies as it is perhaps the most critical for the architecture to be aware of and in conversation with the past, present, and future conditions of the space in question. While the pragmatism and clarity that comes with such methodologies often result in a sense of caution and sensitivity towards the site, it separates the architect from its own being as instincts, emotions, memories, and all other phenomenologies are under-valued in the profession due to their fallible and speculative nature. Is absolute clarity needed to create meaningful architecture? With the integration of such intuitive thinking and philosophy into ways of engaging with architecture, the architect can start to form personal connections, relationships, and memories with each project, creating the work through simultaneous jumps between and overlays on intuition and reasoning. Building

From Memory is an attempt to explore memory as a mode of existence through architecture and photography,

Memory is the continuously evolving core of our minds and bodily existences. It is fallible in essence, constantly evolving as one continues to experience new memories throughout their life. There is no linear movement of time as we know. Time is comprised of multiple dimensions occurring simultaneously. The deceiving and disorienting nature of memory is reminiscent of a troubled archive, a repository that does not represent the truth. The truth does not concern the memory as memory could be either real or constructed but it is always in relation to reality. The emotions that the memory evokes is the truth itself.

“Capriccio” is a Renaissance form of imaginative fantasy. The concept is characterized by unreal and sublime works that blend real and fictional elements into fantastical compositions. These pieces feature exaggerated elements, such as grandiose structures and improbable landscapes.

Figure 1

Francesco Galli Bibiena’s capriccio of a renaissance palazzo is reminiscent of visual characteristics of memory. As the center of the room serves as a stage, the endless passages in the background depict infinity through warped senses of time and scale.

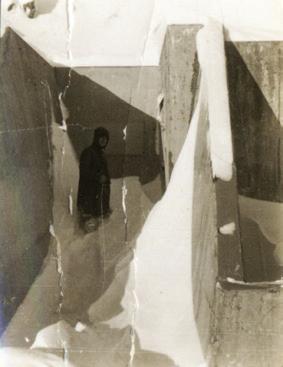

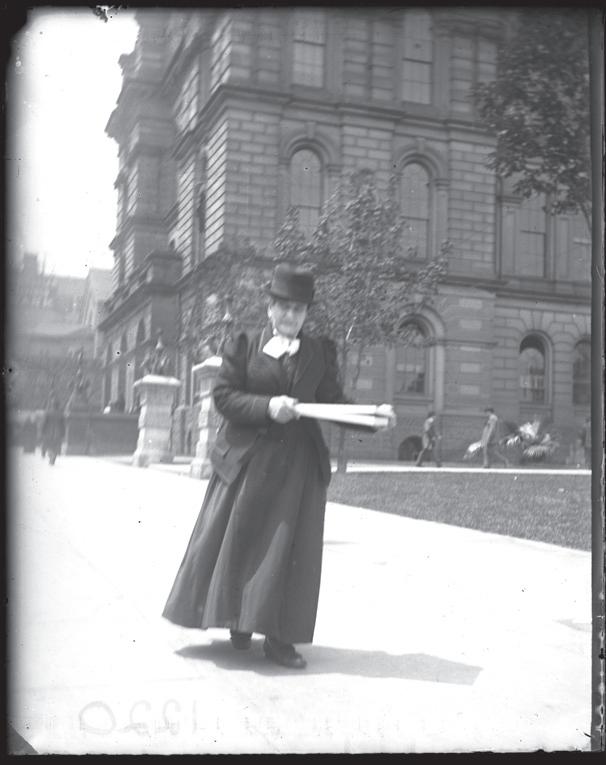

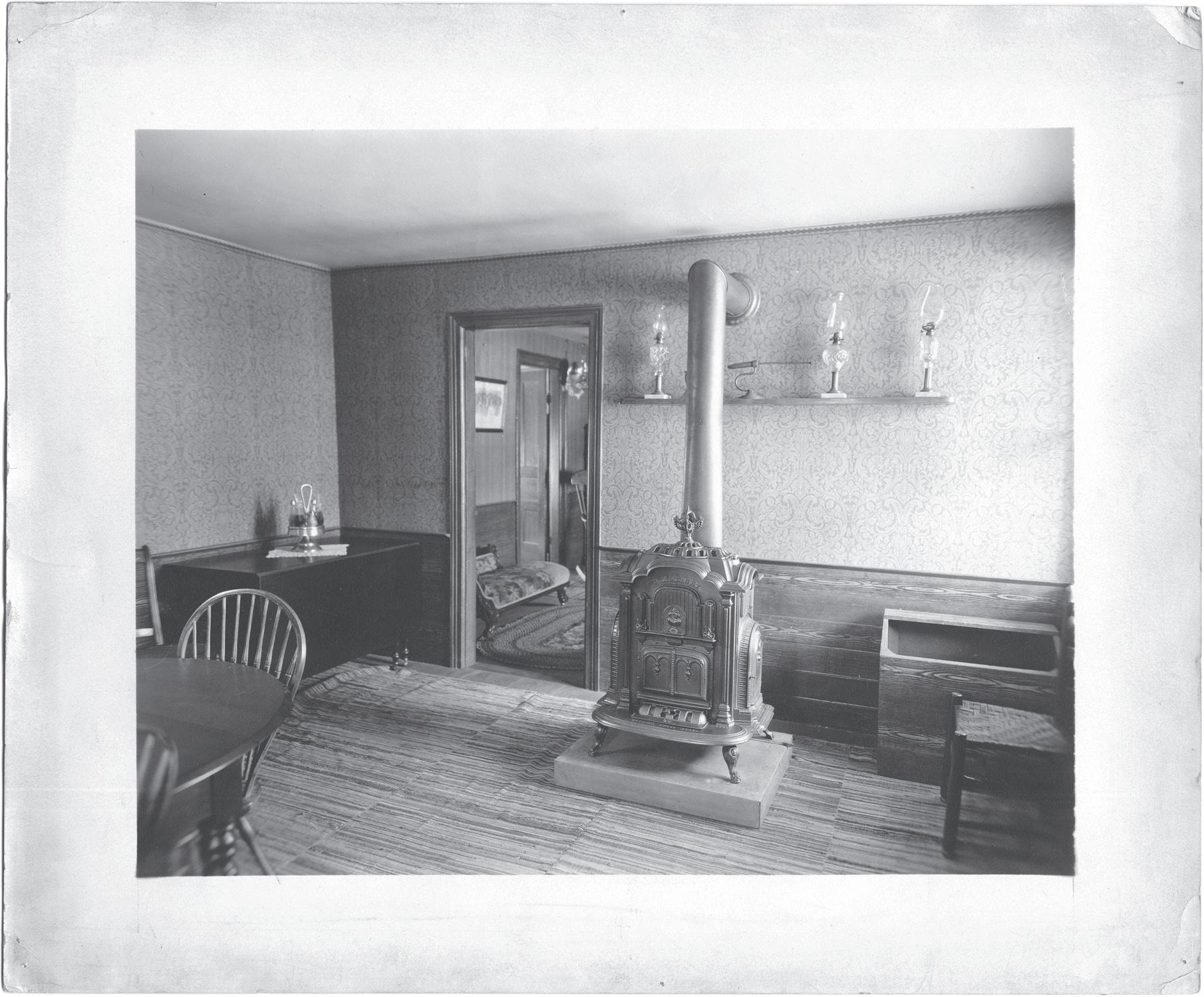

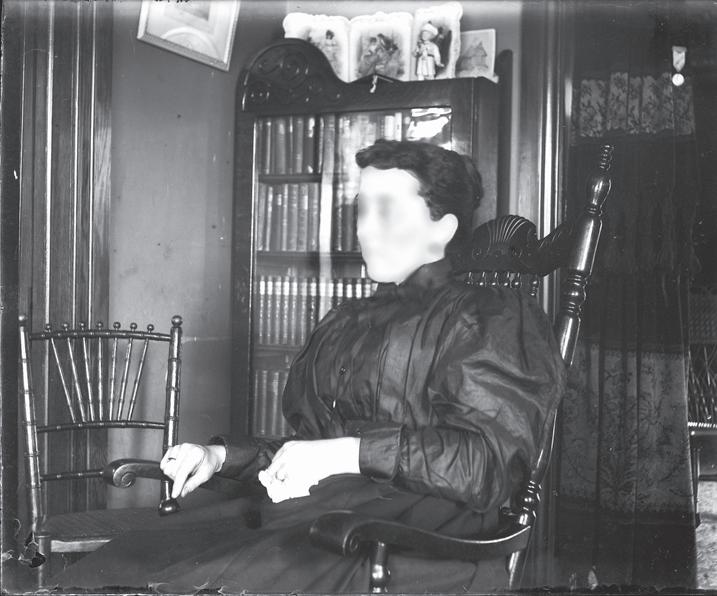

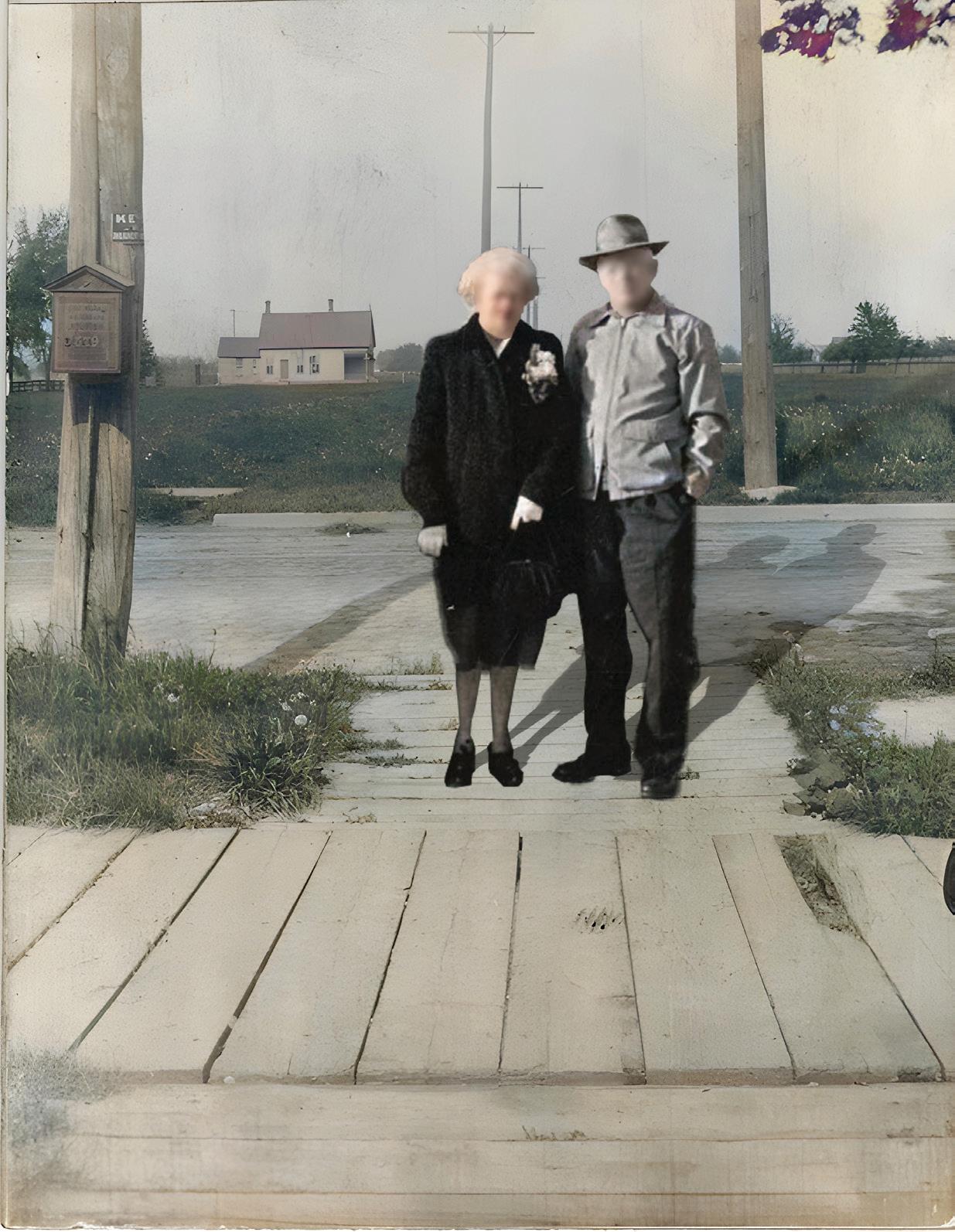

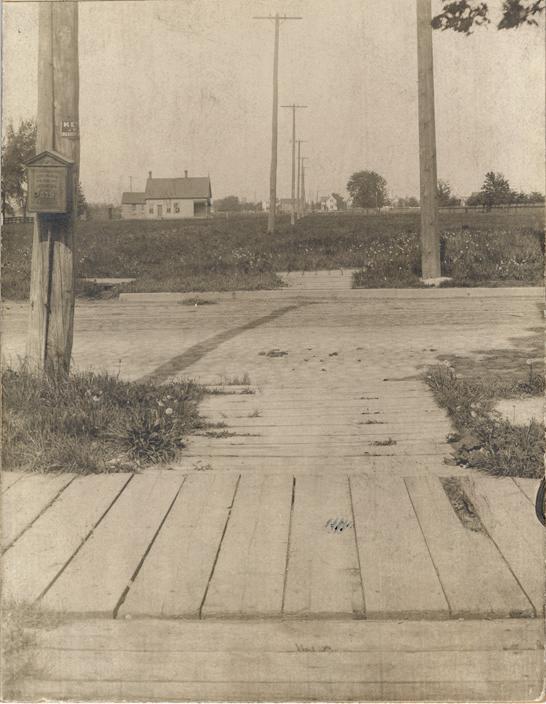

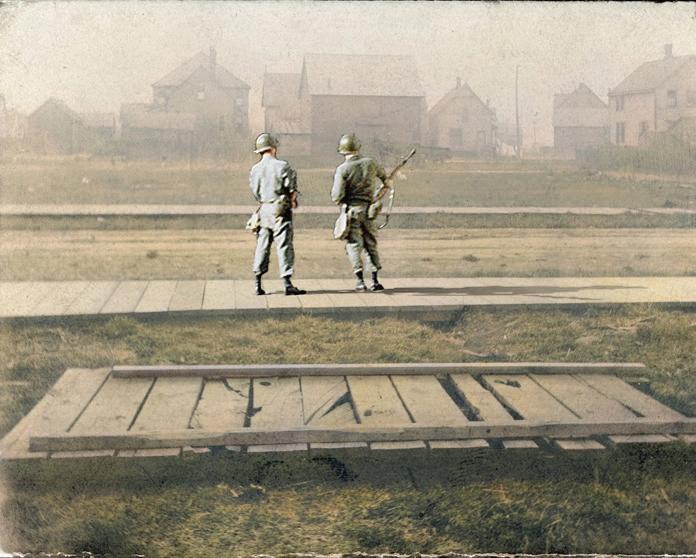

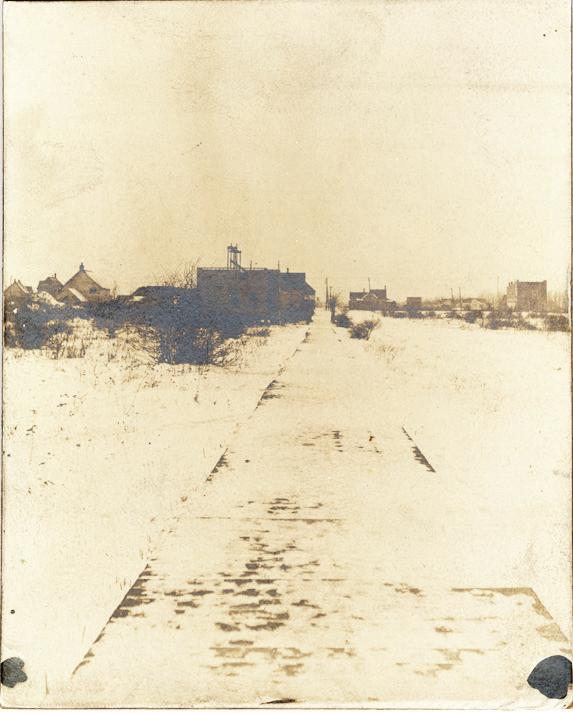

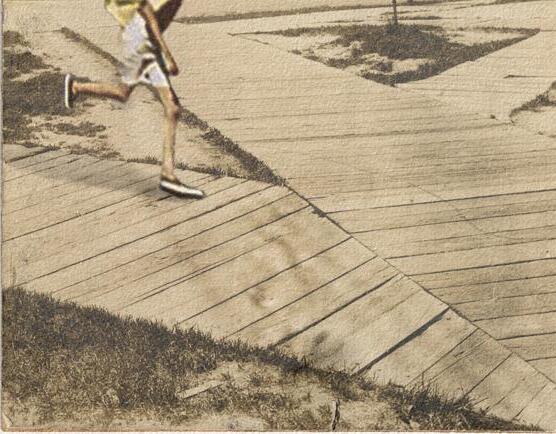

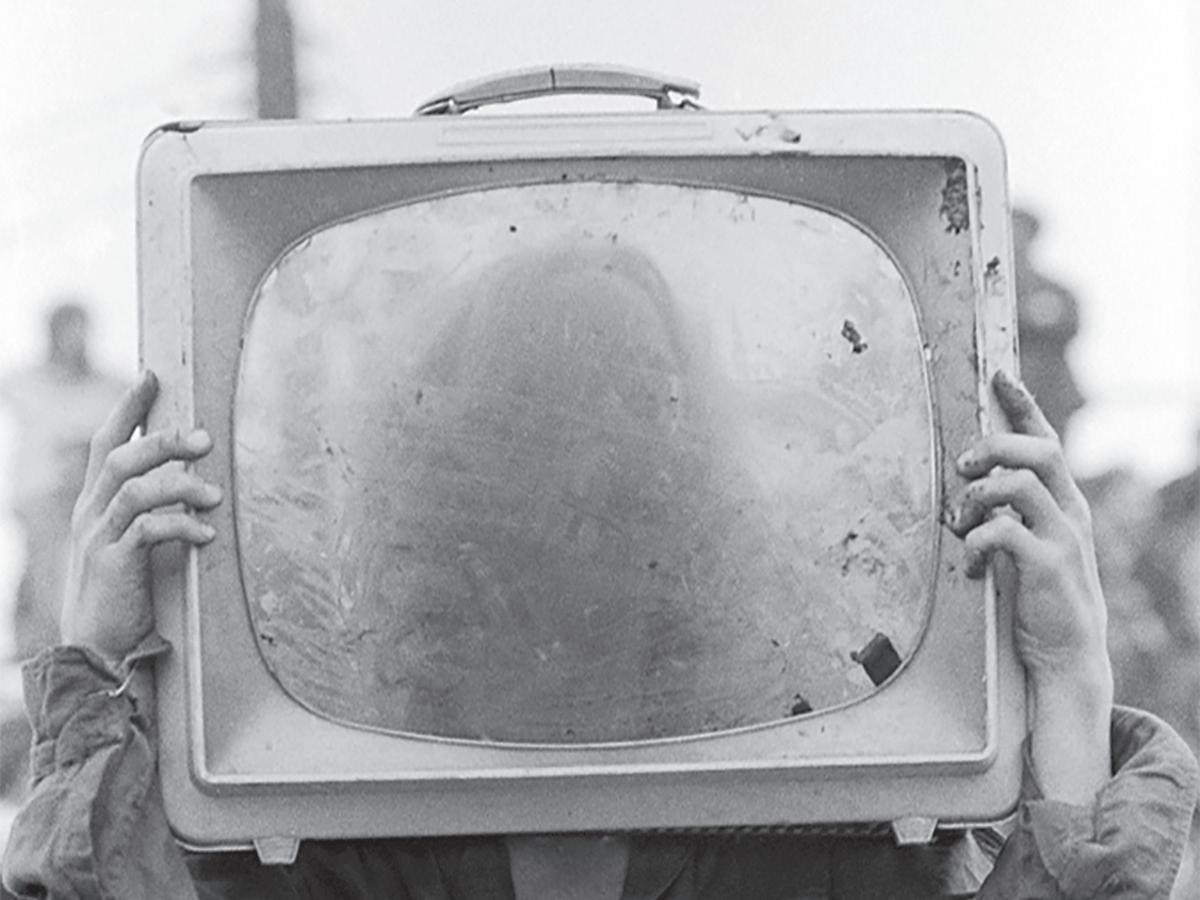

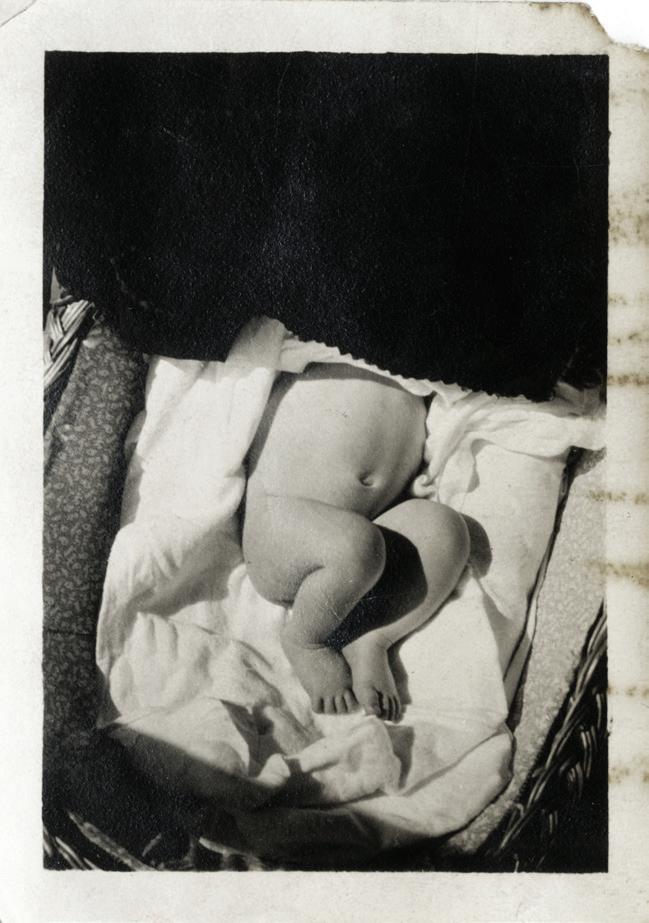

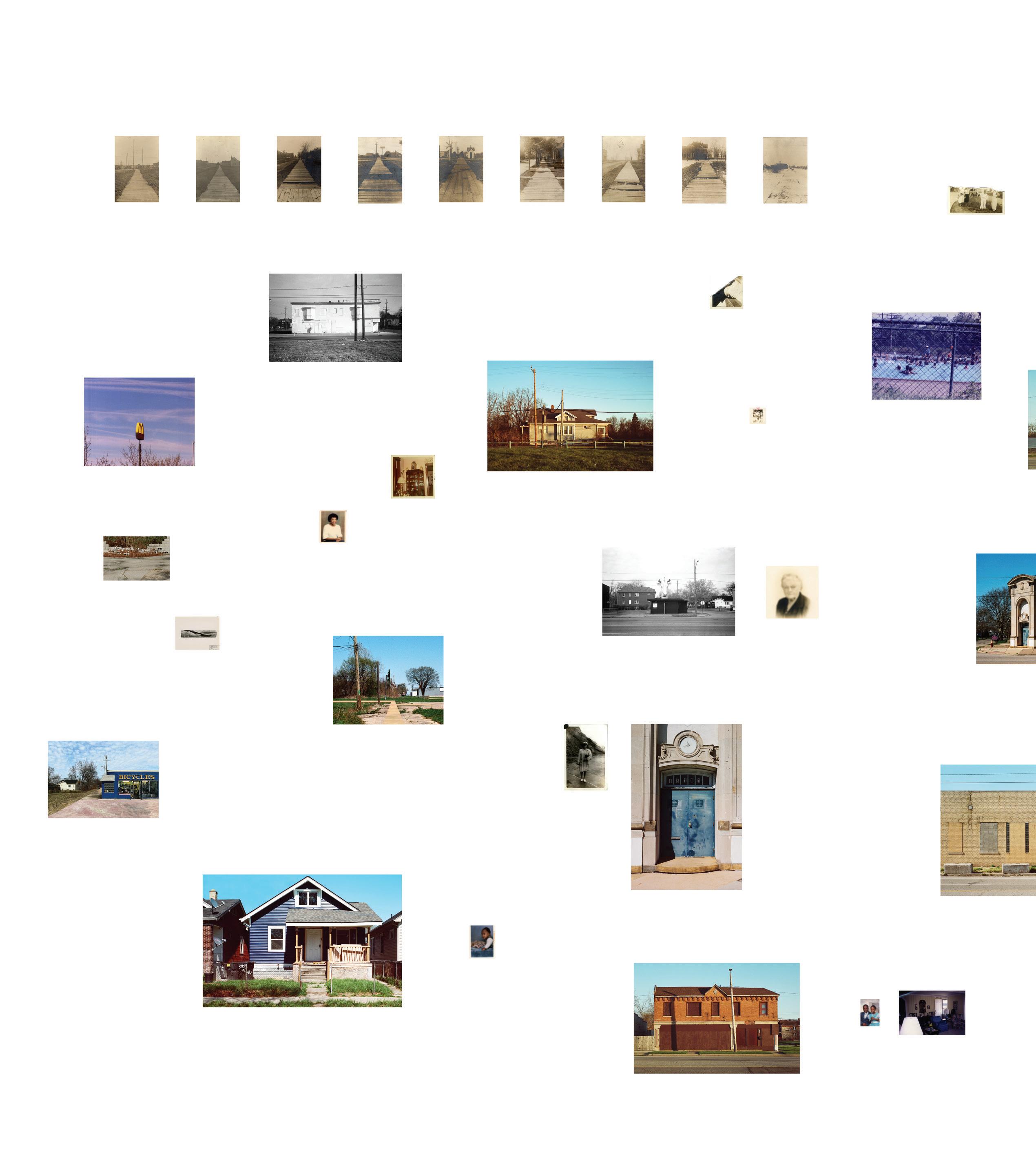

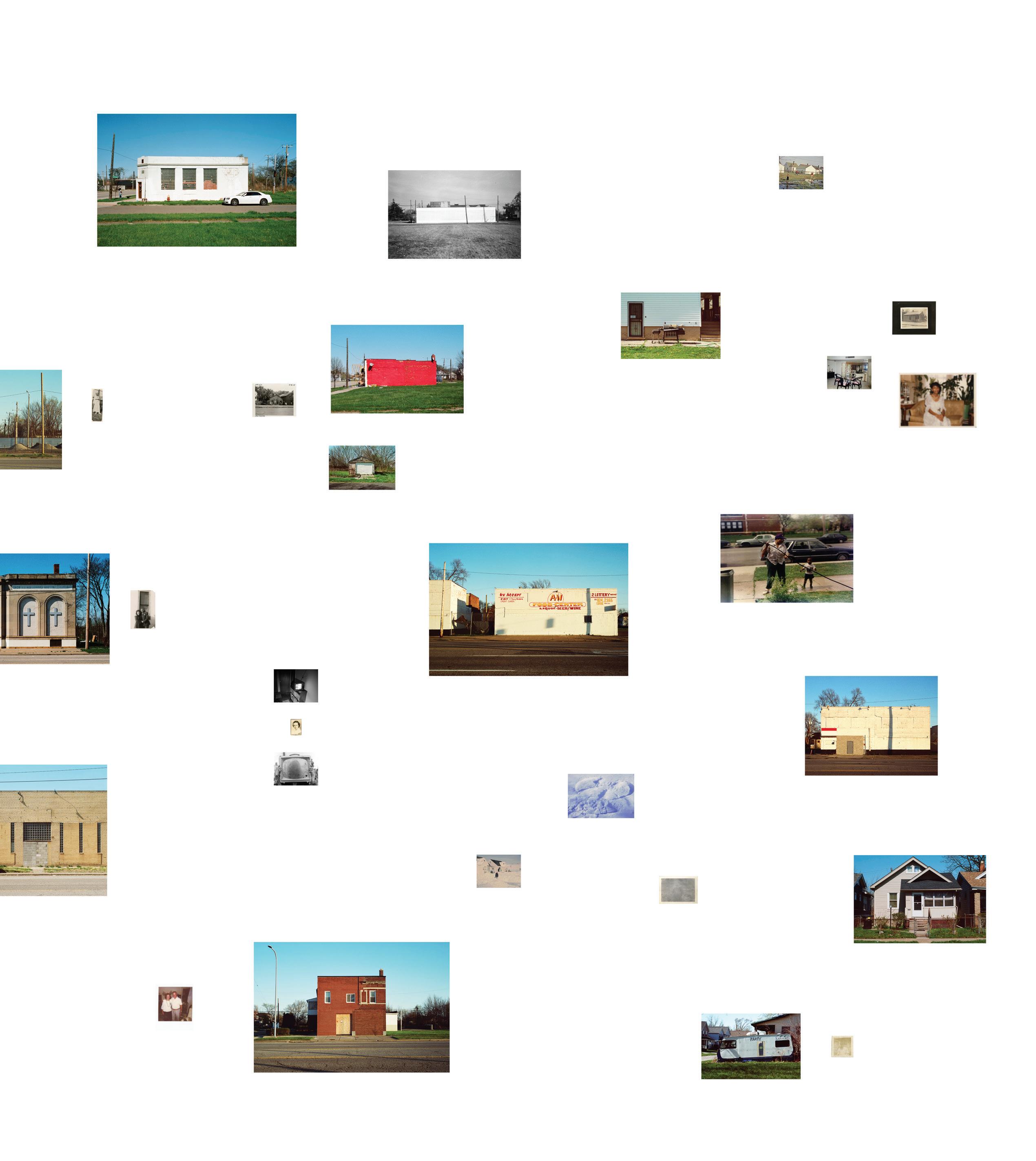

I have always felt a strong connection to Detroit, likely for its techno music. But, I know there were some subconscious decisions that ultimately led me to study and visit it. As a complete outsider to the city, I wanted to create memories in/for a place I have never been in my life. I decided to visually plant memories of Detroit in my mind -and yours- through a series of montages inspired by dream like capriccios. The initial montages were created from found archival photographs of the city, as well as family albums. By displacing, blurring, and scaling, I fabricated new fallible yet realistic memories of people in places where they have never been, possibly during a year they were not alive yet. The act of blurring, especially the identities of people featured in found photographs, is most necessary to compliment the silence of the troubled archive: as these montaged memories and stories are fabricated and symbolic, the subjects are freed from becoming materials of archival research.

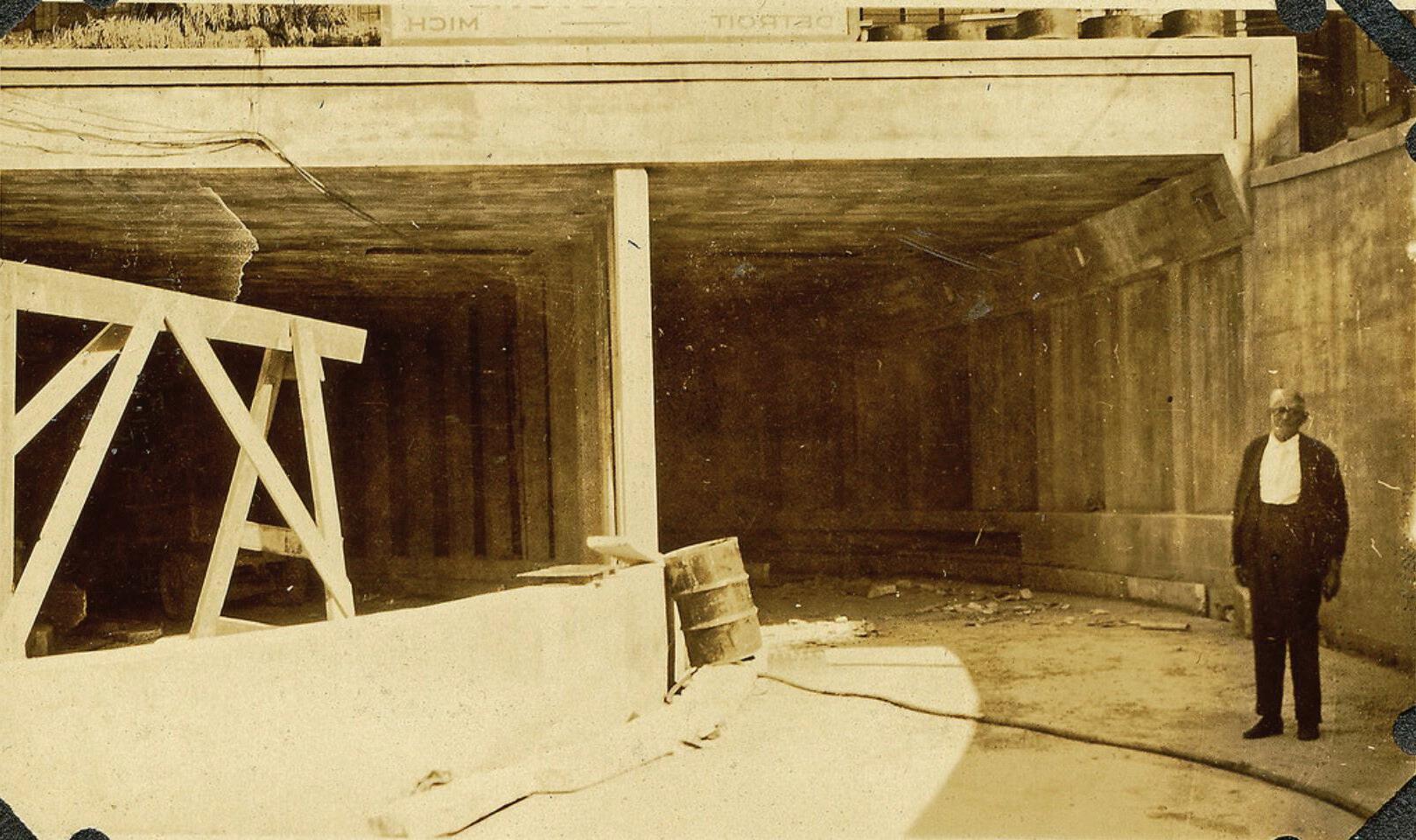

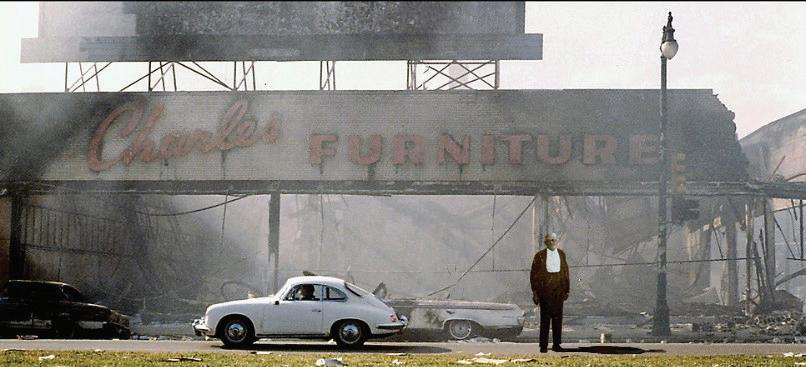

The authenticity of the photograph no longer matters as the distinction between real and montaged photographs becomes unclear to the viewer. Although, the it was never credible to begin with as authenticity itself is flawed due to the power the photographer holds in determining what subjects to include or not include in any given frame. Pages 6-7 show a man standing in the entrance of Detroit-Windsor Tunnel in 1929. On the right, we see the same man again in front of a damaged furniture store after the 1967 riots.

Maurice Halbwachs declares that collective memory “has no autobiographical component at all.”

People do not remember events or places directly. Their memory is stimulated by inherited stories, narratives, or depictions that lead to a type of “second-generation” memory effect. Every recollection, even the most personal and private thought or sentiment, is connected to a social group. Our memories are anchored within a social context, situated in the mental and physical spaces provided by the group. The apparent stability of these surrounding material spaces helps us preserve collective memories. In the case of Detroit, the physical conditions of the city has been anything but stable over the past century.

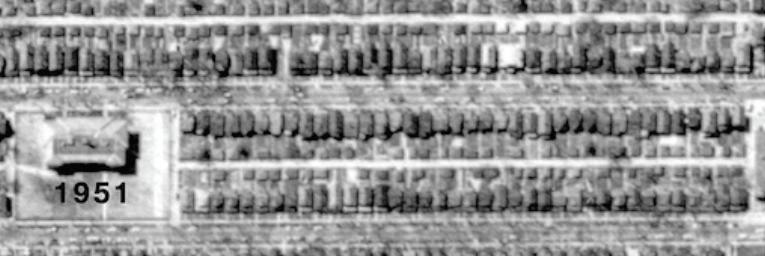

Once one of the strongest economies in the country due to its automotive industry, Detroit peaked its highest population of 2 million people in 1950, declining to around 600,000 people in 2023.

Detroit’s history of Black residents dates back to before the 1900s. The city’s Black population saw significant growth during the Great Migration. Drawn by the promise of jobs in the thriving automotive industry, Black migrants from the South, along with Europeans and Canadians, came to Detroit.

Segregation is a combination of social and political factors and is deeply rooted in city’s urban landscape. Redlining created divisions based on race and ethnicity as white laborers were repeatedly prioritized in obtaining desirable housing close to jobs, which moved out of the city following the decline of the automotive industry amid World War II. Black residents on the other hand, were continuously declined for mortgages and pushed into “D areas,” which were considered “hazardous” for investment. Redlining is one of many ways segregation has embedded itself into Detroit, which still remains one of the most separated cities in the United States.

Figure 2, Change in population density, Image by Katherine Gowman (2014)One neighborhood that evoked a particular sense in me was Fox Creek in Eastside Detroit. Currently, the neighborhood has an abundance of empty land as less than 2000 people live there. Most recently, homeowners’ residences were taken away from them by land banks during the mortgage crisis of 2008, adding on to the steadily declining population trend since the 1950s. Up until redlining, the neighborhood was densely populated with white majority residents who worked in nearby automotive plants. The neighborhood was given a grade of C & D after Black residents moved in, while neighboring region Grosse Pointe was rated A & B. Although just a few miles apart, one could easily tell the border between the two.

Grosse Pointe’s maintained tree lined streets and small businesses are taken over by empty lands and dilapidated buildings as one crosses over to Fox Creek. The segregation is ongoing today as Grosse Pointe actively blocks entry to and from Fox Creek by closing off main streets, physically detaching itself from the neighborhood.

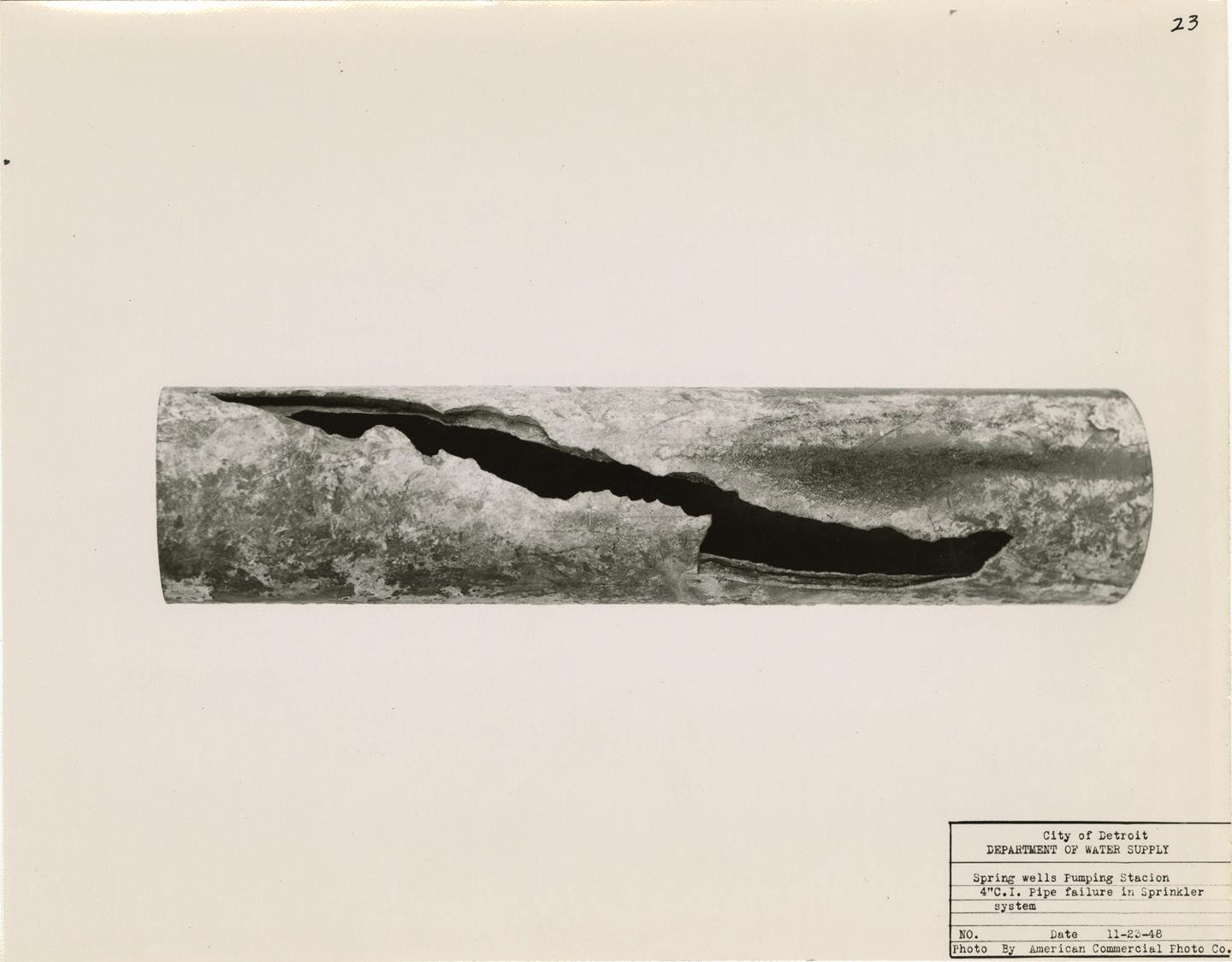

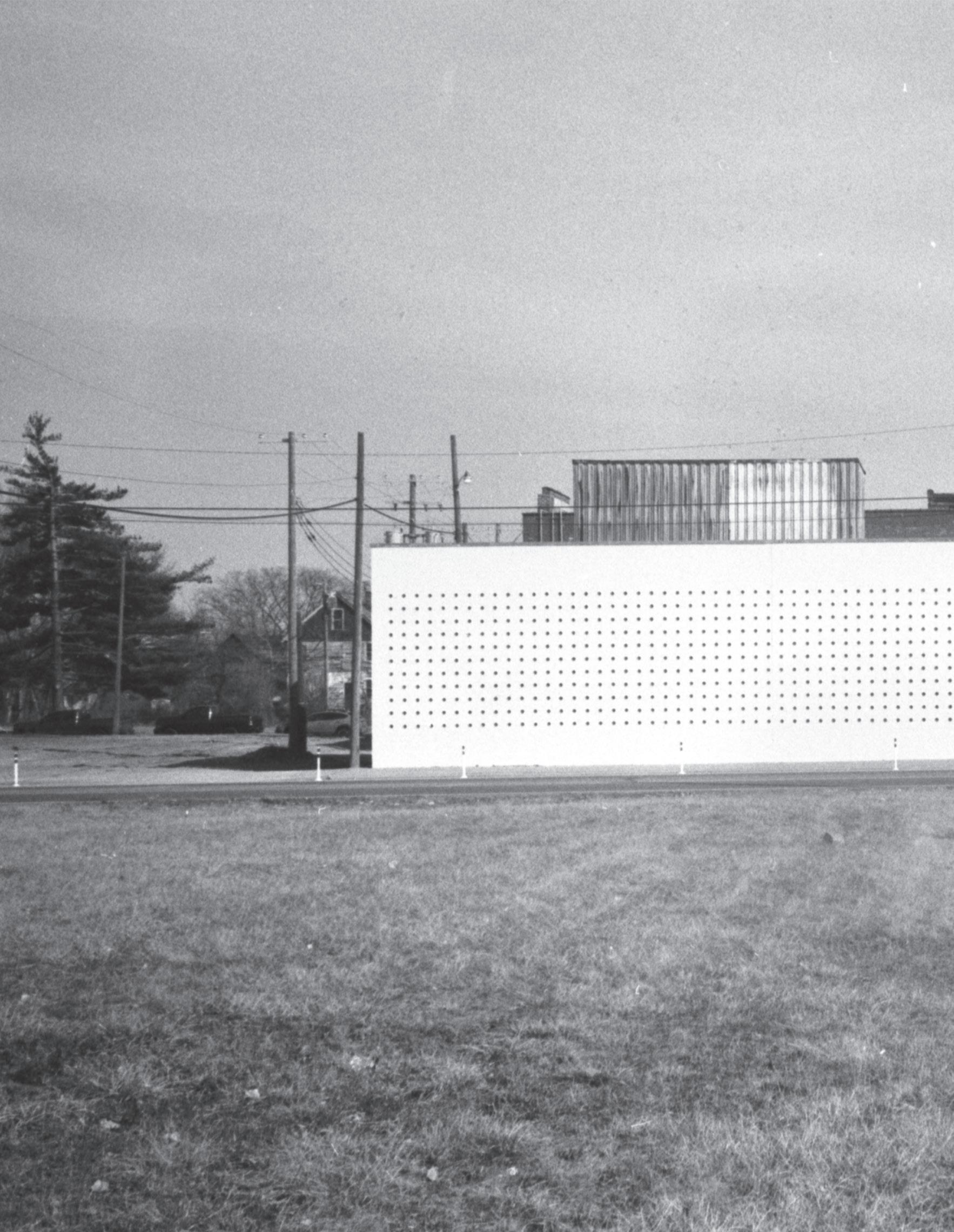

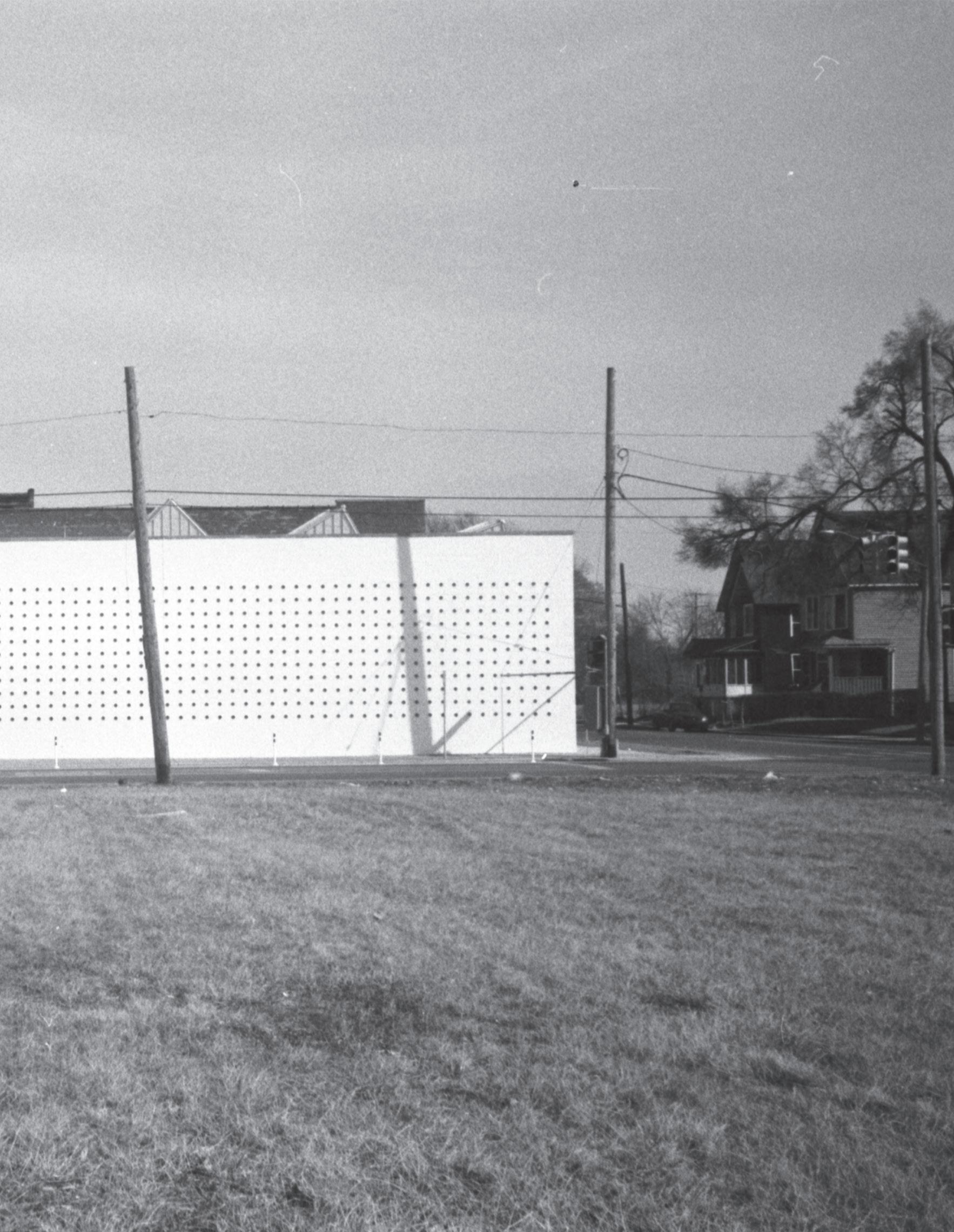

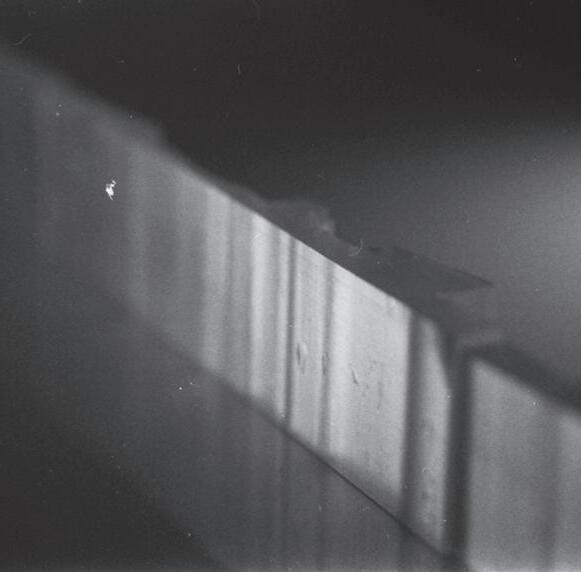

The collective memory of the wall as an architectural typology in Fox Creek is very different than what it is in Grosse Pointe. The wall is a physical and abstract tool for segregation and separation of people in Fox Creek, whereas it is a reminder of security and comfort in Grosse Pointe. As collective memories can be fabricated in essence, the wall carries the potential to alter existing and construct new memories of the neighborhood. My first visit to Detroit was spent finding and photographing different uses and meanings of the wall in Fox Creek. I biked and drove around the neighborhood, making quick stops to document the walls that each housed its own universe behind its facade. The walls felt as if they were stage props due to their distinct and kitsch qualities. I photographed them keeping their architectural frontality in mind, not dissimilar from a portrait, directly confronting the viewer with the absence of any thickness, but just a surface. Page 76 is the image of an old bank building that is currently unoccupied. The windows of the building reminded me of the idea of spolia: materials left behind and re-used as the window becomes the palimpsest of its memory. Glass cubes are vernacular elements of many walls around the neighborhood due to their affordability and popularity over the past few decades.

The walls of the neighborhood directly speak to the memory of the place. Architectural elements including covered windows and entrances, decaying streets, and left objects are all products of the segregation that physical and abstract walls has brought into Detroit. Bringing in the magical realism through montage, I edited some of the photos to imagine these spaces as small businesses, bike paths, and gathering spots -mundane programs that a neighborhood needs to stay alive. Page 84 shows an old ice-parlor brought back to life through montage. Unknown to the viewer, this building with the statue of a cow head on top is currently offered for lease and is a black box with no windows or any use as seen on Page 49. Worried about the size of the cow, one of the locals told me he suspects that the building will tip over due to the weight of the sculpture.

Upon visiting Detroit twice, and creating real and unreal memories of Fox Creek, I am attempting to alter the collective memory of the wall through architectural intervention: a glass ribbon that folds, and unfolds to create communal spaces on an empty lot surrounded by backyards of single-family houses on both sides.

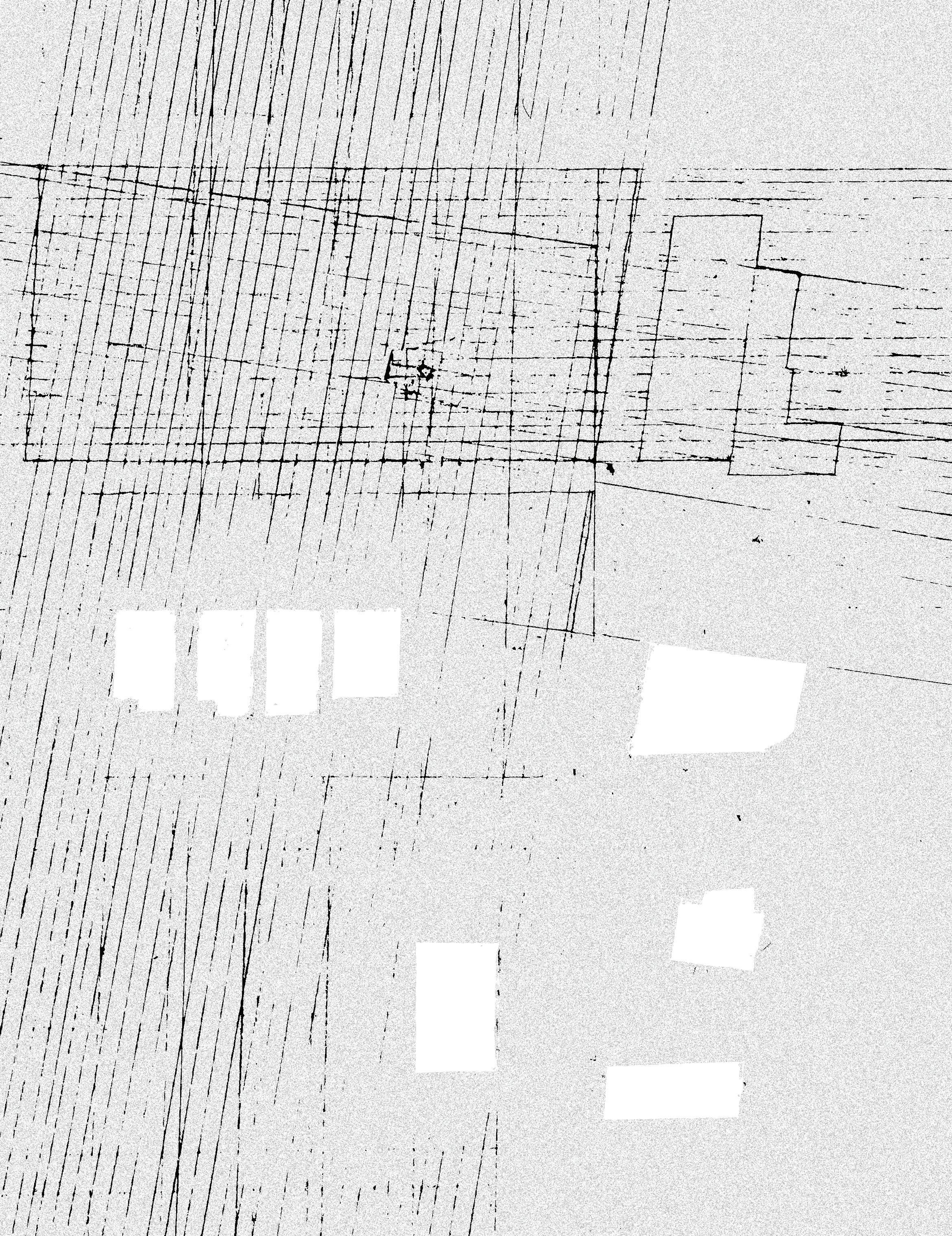

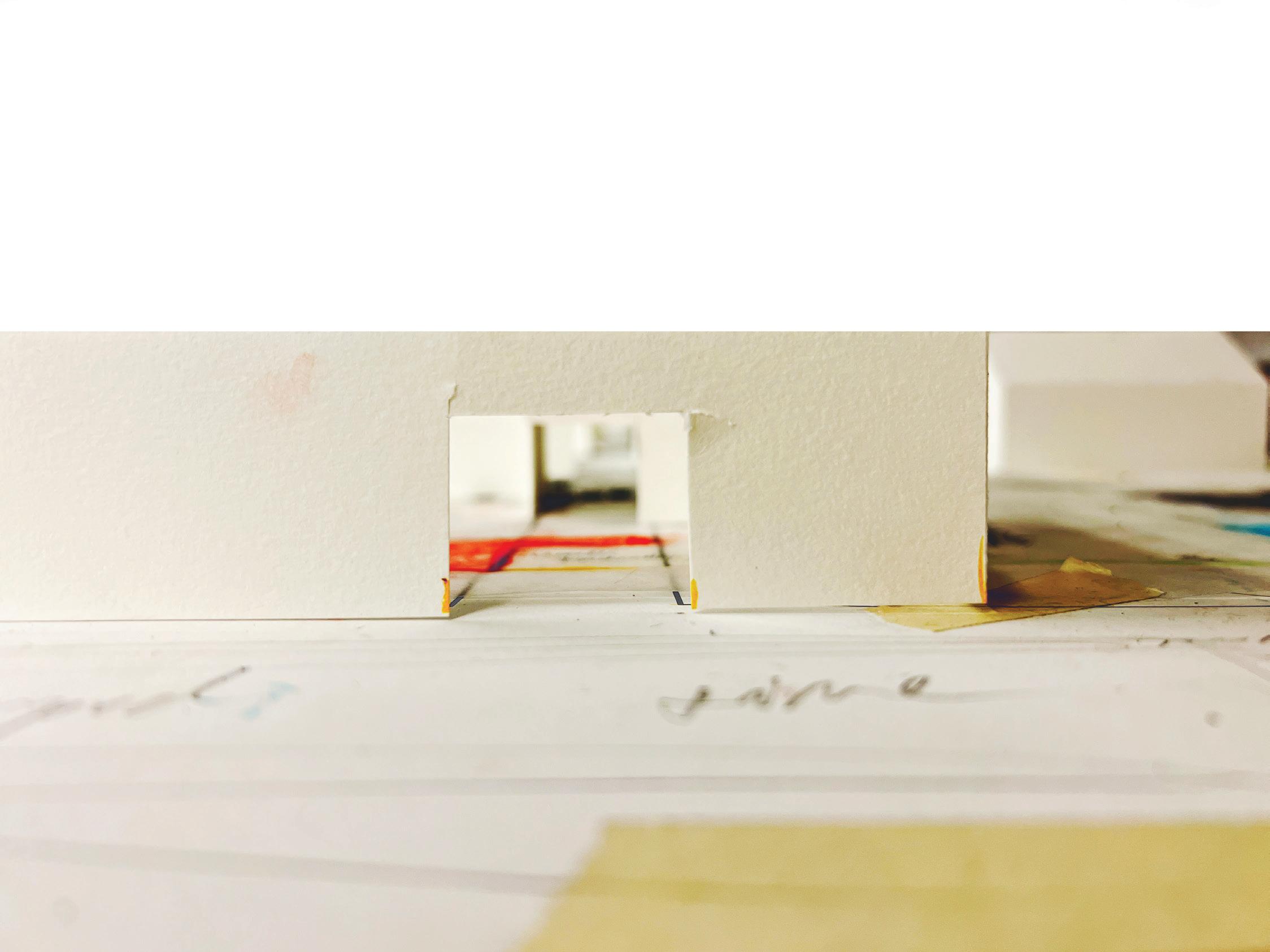

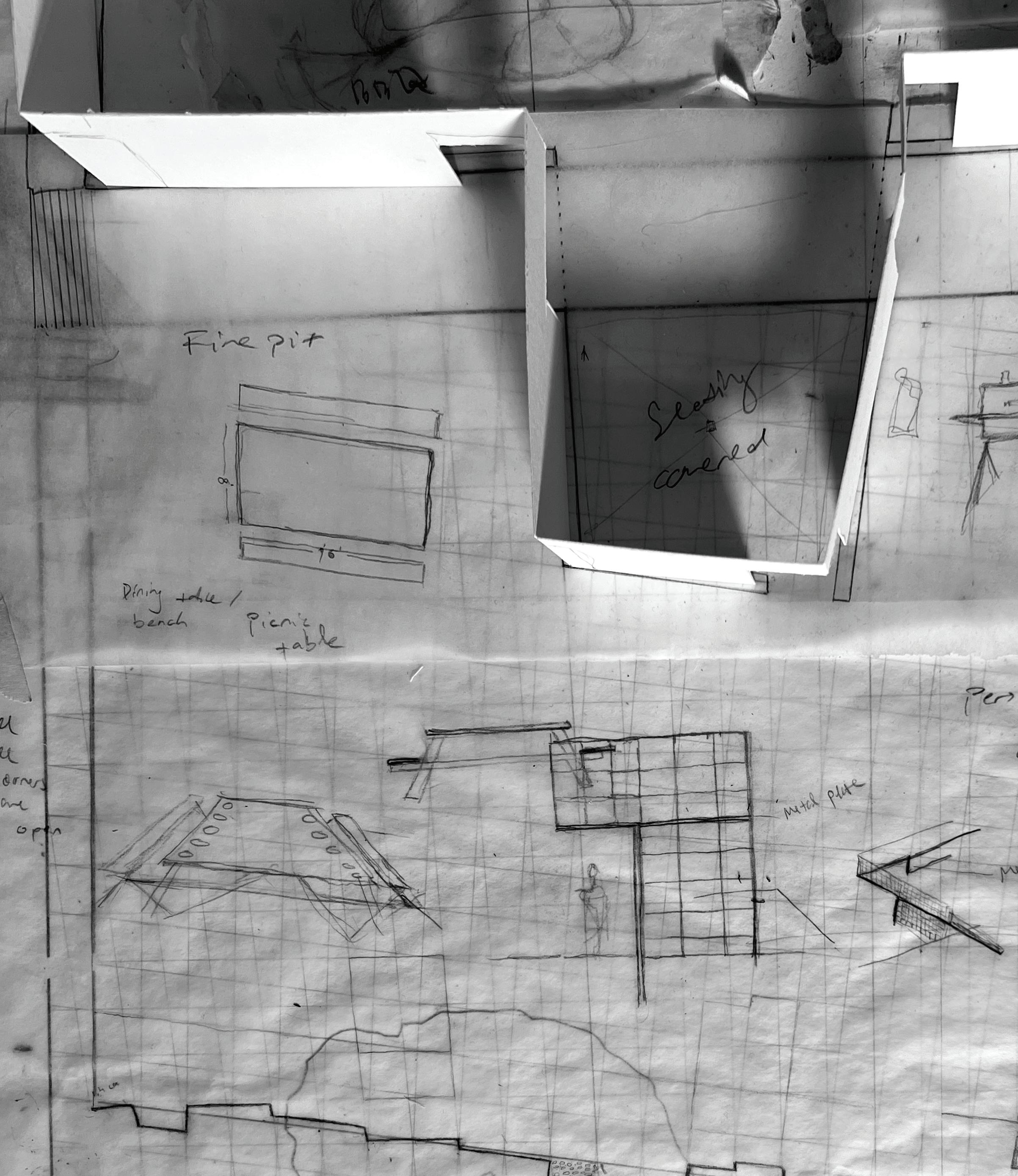

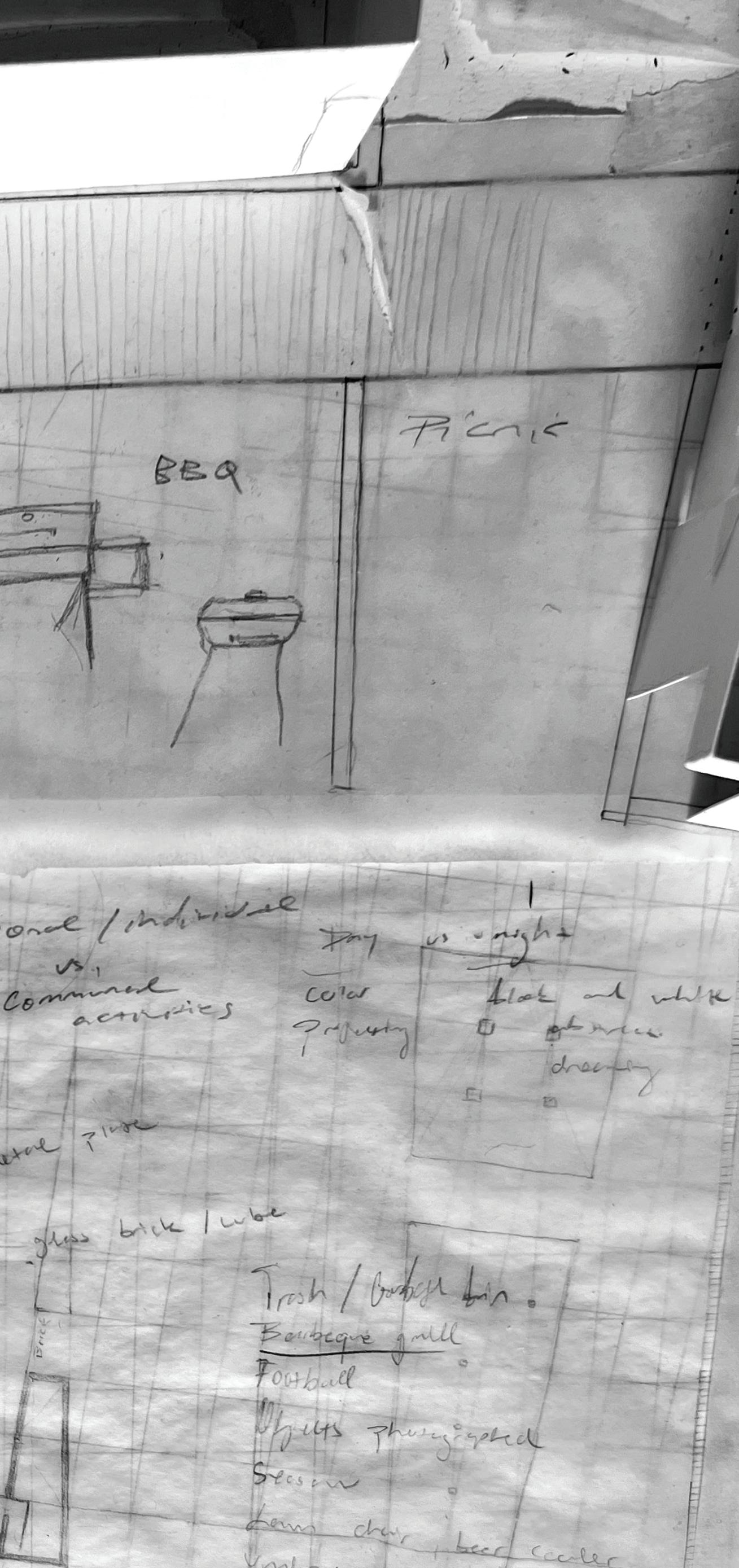

The ribbon form arrives from an overlaid drawing of new and old street grid systems of the neighborhood (Pg 113). The switch of a seven-degree angle in the grid creates odd corners and slightly trapezoid buildings where the facades are parallel to streets with different crossing angles. Matching the scale of the ribbon to the scale of the houses, the ribbon is formed through 12 turns with a series of openings (Pg 116) aligned with the decaying bike and pedestrian path that runs the span of the empty lot (Pg 117). The spaces that are created within these gestures become public extensions of private backyards and allow space for gatherings. Observing the abundance of domestic backyard objects around the site, including grills, water hoses, and carriages among others, these outdoor spaces could be used for a variety of collective activity including barbecues, farming, playground, and block parties. Although the ribbon is in the form of a memory of segregation, the meaning attached to the form is altered through accessible and inclusive spaces that foster community gathering and blur the distinction between public and private.

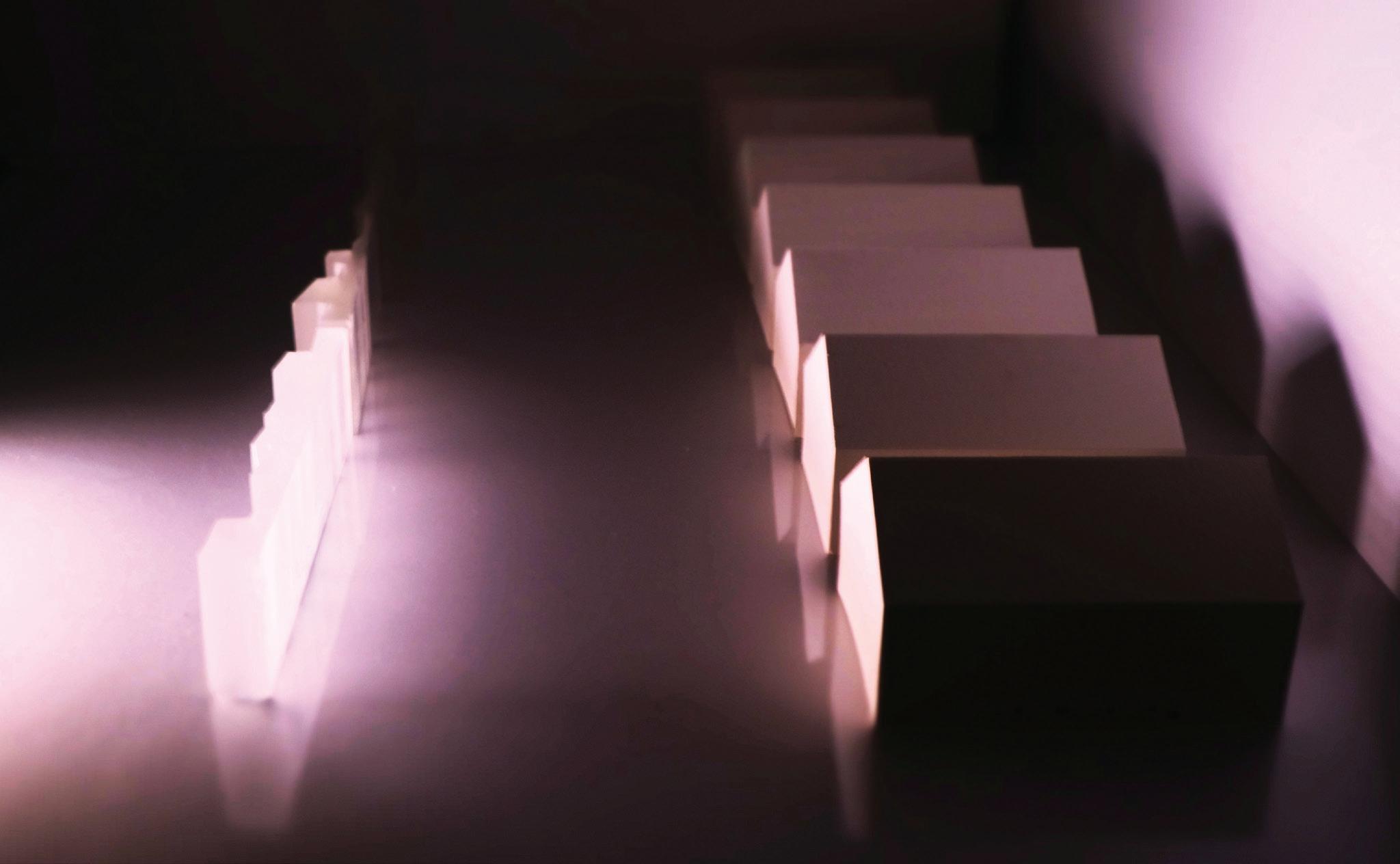

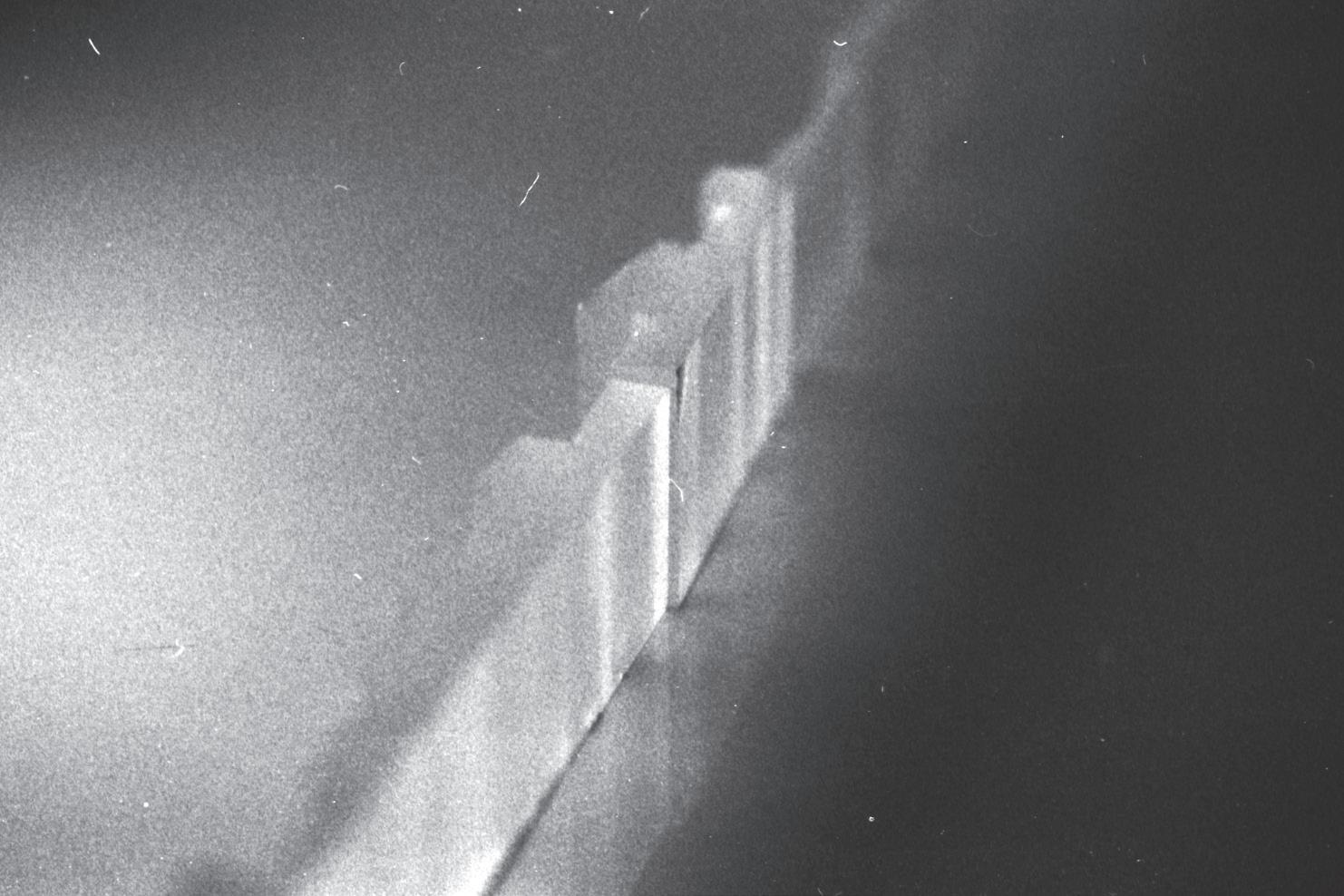

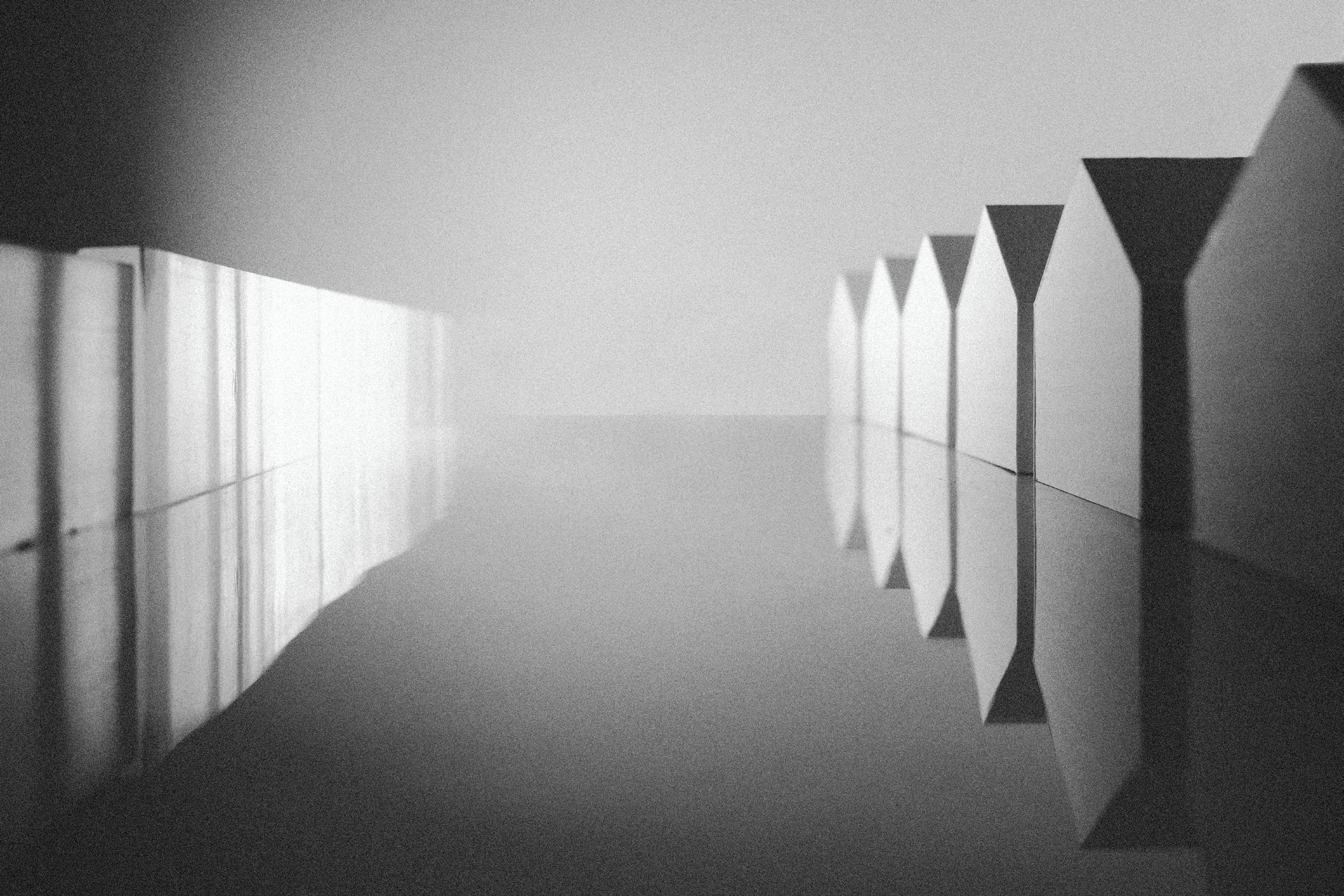

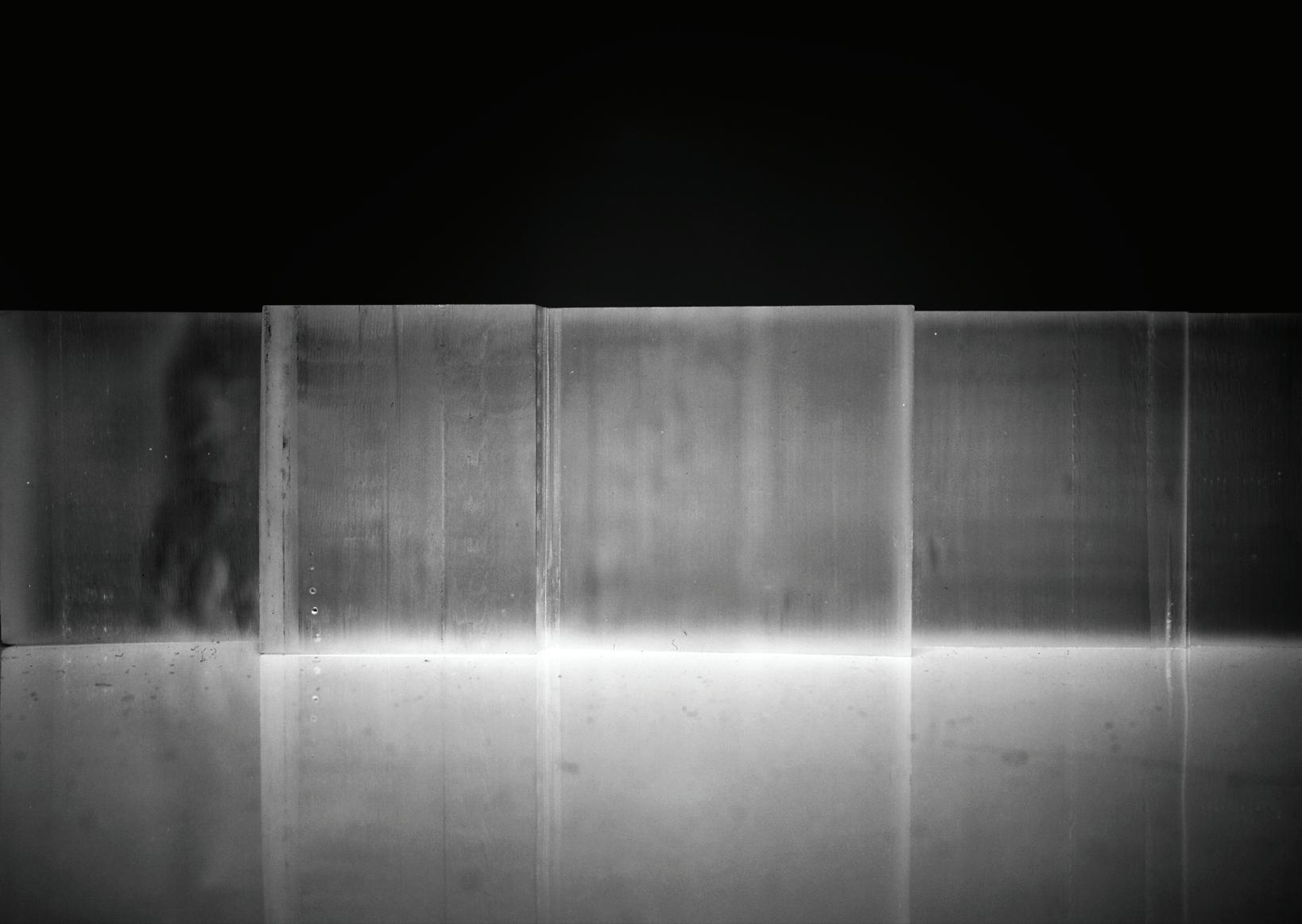

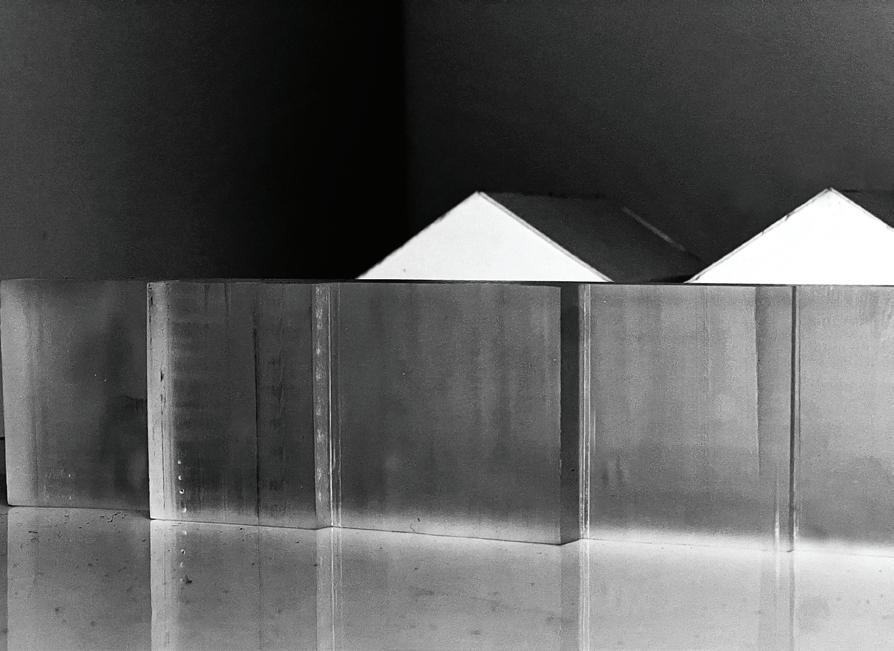

As one strolls along the path, they encounter a series of portals where each space created by the ribbon plays with light and shadow. The ribbon is constructed from glass blocks that act as framing devices with different aperture sizes to observe the surroundings. Two prototypes in one to one scale of the glass blocks were produced as part of the installation (Fig 5.)

As the glass reflects and projects light, contrasting spaces (Pg 120) that blur the line between reality and dream state encapsulates the user within their own memory, creating opportunities for contemplation and reflection. The materiality contradicts the current understandings of the wall as a heavy opaque object, and transforms it into a transparent, clear, and tactile feeling. In doing so, the collective memory of a shared architectural past becomes the carrier of a reality that re-defines its emotional memory: emotions that relate to the real, lived, ongoing life of the user.

A., Fernández Galiano Luis. Fire and Memory: On Architecture and Energy. MIT Press, 2000.

Bastéa, Eleni. Memory and Architecture. University of New Mexico Press, 2005.

Bloomer, Kent C., et al. Body, Memory, and Architecture. Yale University Press, 1979.

Deleuze, Gilles, and Felix Guattari. A Thousand Plateaus: Rhizomes. Venus Pencils, 2009.

Frampton, Hollis, and Bruce Jenkins. On the Camera Arts and Consecutive Matters: The Writings of Hollis Frampton. MIT Press, 2015.

Halbwachs, Maurice, and Jeanne Alexandre. La Mémoire Collective. Presses Universitaires de France, 1950.

Kodalak, Gökhan. Spinoza and Architecture, Cornelll University, ProQuest Information and Learning, 2020.

Pamuk, Orhan. Istanbul: Memories and the City. Faber, 2017.

Sagan, Carl, et al. Cosmos. Random House Inc, 2013.

Sommer, Richard, and Natalie Fizer. “Glossary of Dream Architecture.” Cabinet Magazine, 2019.

Steil, Lucien. The Architectural Capriccio: Memory, Fantasy and Invention. Routledge, 2016.

Sugrue, Thomas J. The Origins of the Urban Crisis: Race and Inequality in Postwar Detroit. Princeton University Press, 2014.

Zumthor, Peter. Atmospheres: Architectural Environments: Surrounding Objects. Birkhäuser, 2006

Many thanks to Detroit Public Library for their online archive of historical photographs and all unknown photographers of found images featured in this book for giving me the chance to see Detroit from your eyes

to Erin & Luben, for all the immense support, advice, genuineness, freedom, and trust

to Nidaa, for eternal inspiration and knowledge to Jason, for being there for me in all moments of panic and desperation

to Idil & Ela, for being amazing thesis helpers, and even better rakı friends

to the B.Arch Class of 2024, for countless moments of craziness and laughter to Musk, Seb, and Sam, for being my family under the roof of one exquisite house

to my parents Tijen and Taner, for always listening to me with care and patience

to my sister Talya, for all the color you spread