Teachings of our Ancestors

The Tāłtān people have occupied their territories around the upper reaches of the Stikine River in what is now northwestern British Columbia since time immemorial. The relationship between the people and the land, as with many Indigenous peoples, is one marked by a deep respect for the land as provider and a strongly held belief that the people are Dena nenn sogga neh’ine (keepers of the land) and the beings that inhabit it.

Land stewardship, determination, generosity and resourcefulness are principals passed from generation to generation through the mentorship of Elders and the telling of stories. Dukuh Ja’ Łuwe Ahuja is one such story. In written and illustrated form, this story continues to foster Tāłtān ways and will continue to instill pride in Tāłtān language and culture.

In 1977 Tahltan matriarch, Emma Brown was interviewed by Tāłtān archeologist, Vera Asp and language teacher Angela Dennis. They worked together to adapt Dukuh Ja’ Łuwe Ahuja and other recorded stories from an oral to written form. The work done by our ancestors, Elders and Tāłtān cultural practitioners is the foundation for the Dah D z ahge Node s ide (We Write Our Language) Tāłtān language revitalization project and a platform for knowledge to pass on to future generations.

That’s How the Fish Came About

Translations

told by Emma Brown

As

Angela Dennis

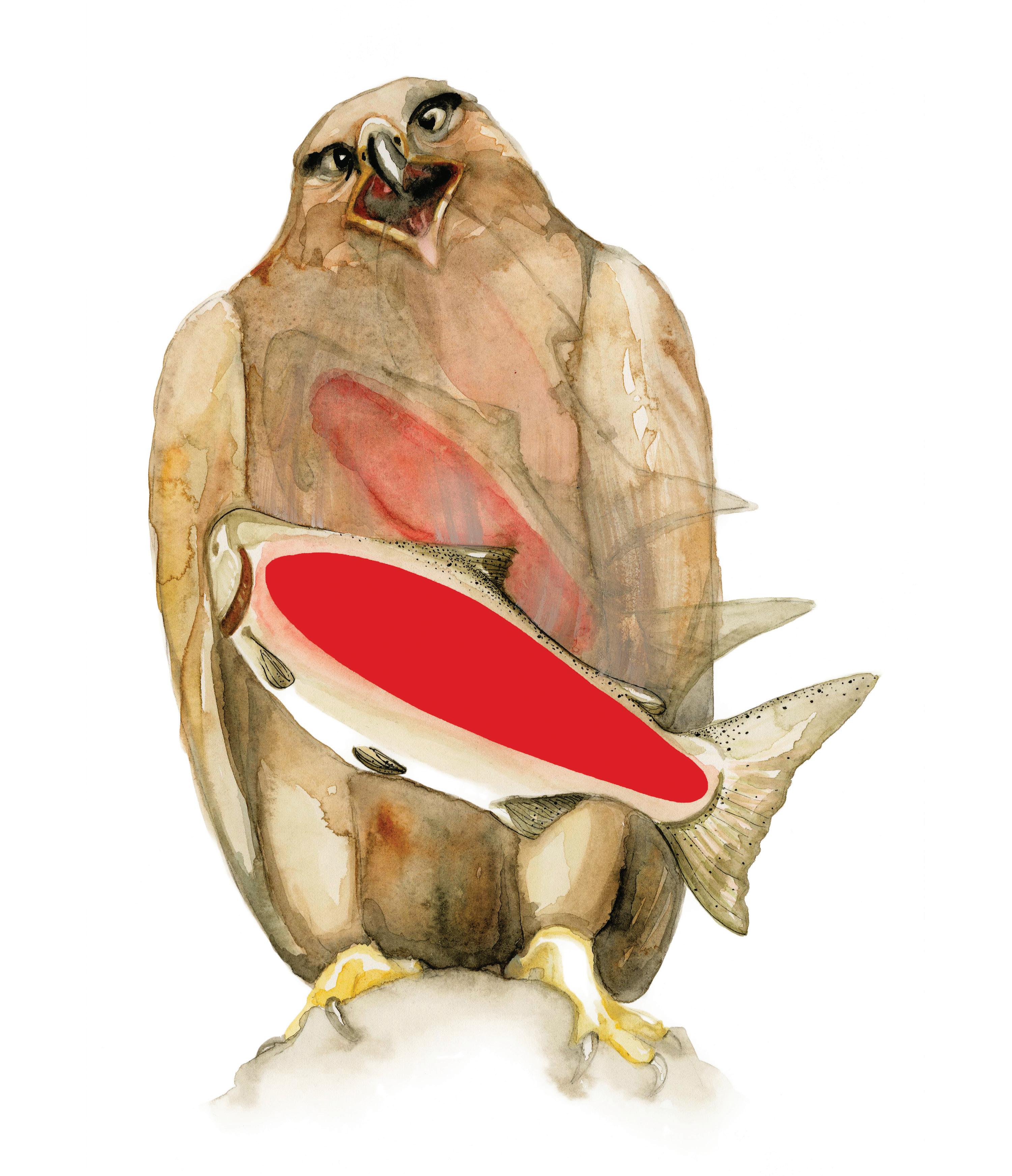

Illustrations Tsēma Igharas

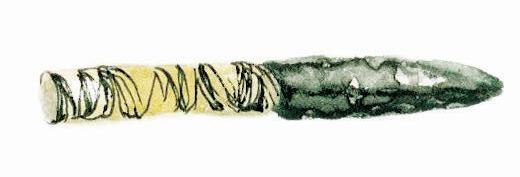

Ēy, esjāni denezā’ tsedze łuwe yit’īn.

The old man owned all of the fish and he did not share.

Łakehdet’ē hizihge aht’īn, mesk’ā, tuhdā.

He had two helpers, the seagull and eagle.

Hogha’ahīłā t’ē

dene hedegah ładāł. Hogha’ūła’i daga hūdehkit.

As they worked a man came along. He asked them for a job.

Tsesk’iyechōlīn egoł denezā’ anedededlē.

He was a raven transformed into a man.

Tsesk’iye chō hodedehde s . Tlenhedegāhi anhūdededlē.

The raven was a trouble maker. He was making them fight.

Tsesk’iye chō depāne ekune ts’i’ ts’e’ets’īt.

The raven was telling lies to his partners.

Hudiyehch’ah dūda tsesk’iye chō adi.

What raven said made them sad.

Mesk'ā eł tuhdā tlehedē s gan.

Tsesk’iye chō ejini eł kazeł.

The seagull and eagle started to fight. Raven was singing and yelling.

Tsesk’iye

chō mesk’ā t s i’ t’iynesghits t’ē łēgas.

Raven pulled seagull’s head back. He twisted it until it broke.

Ka’at’īn t’ē, tuhdā nēhgāk. Nēhgāgi t'ē łūwe ye z akāt s ’et.

As he did this, the eagle became suprised. The fish fell out of the surprised eagle’s mouth.

Tsesk’iye chō łūwe niydiht’īn, yē eł tēdest’ak, “Gāh gāh gāh!” ehdih.

The raven picked up the fish, called out, “Caw caw caw!” and flew away.

Ēy tl’ā tsesk’iye chō łūwe t s ’ene ēyede s lah, Tāłtān keyeh t s edze tū keyīts’et, hutūhe, hutūde s e, humene.

Later the raven threw all the fish bones to all of the Tahltan waters, rivers and lakes.

Dukuh ja’ łuwe ahuja.

That’s how the fish came about.

Ūwet’ē dūnahat s ełi łūwe tude s e keh tanahas.

A certain time of the year, the fish always come back to our rivers.

Kuji. The end.

Tāłtān Alphabet

Pronunciation > Tāłtān Example : English Translation

Vowels

A a u in cup > gah : rabbit

o Ō ō U u Ū ū ’ B b ch ch’ D d Dl Dz Dz G g Gh gh H h J j K k

ē I i ī

longer in duration - something like au in caught > dā nā : money

e in ten > menh : lake

same as e, but longer in duration > bēs : knife

e in enough, or ee in keep > ni’ : face

same as i, but longer in duration > nī’ : moss

oa in oats > khoh : grizzly bear

same as o, but longer in duration > chō : big, large

oo in boot > ghu’ : tooth

same as u but longer > tū : water

no written equivalent – made with a stoppage in the throat (glottalization) > ete ’e : father

Consonants

b in big > bēs : knife

ch in church > chō : big, large

same as ch, but made with a stoppage in the throat > ch’oh : quill

d in did > dene : person

no English equivalent > Dlūne : mouse

ds in pads > Dzime: bird

No English equivalent > Dzeł : mountain

g in good > gah : rabbit

similar to g, but a softer sound > ghu’ : toot

h in head > hiyenelīn : they want it

j or dg in judge > jije : berry

k in keep > kedā : moose

*Amongst some speakers of Tahltan, there are different ways of pronouncing some of the Tahltan consonants. This difference occurs in the letters s, ts, ts’, z, and dz. Words containing an underlined s (s) may be pronounced two different ways. Some people pronounce them with the th sound as in the English word thin. Others pronounce it much more closely to an s sound. Similarly, words containing an underlined z (z) are pronounced by some with the th sound in then or other, and by others by a sound much closer to an English z. In this way, a word like zas (snow), may have two perceptively different pronunciations.

k with a stoppage in the throat > k’ū or k’ū’ : fish eggs

similar to k, but a softer sound

> khēł : trap

l in large > la’ : hand

no English equivalent > łuwe : fish

m in mother > mēduh : thank you

n in nothing > na’ : Here, take it!

no English equivalent > menh : lake

p in pup (a very rare sound)

> espāne : my friend

s in see > sas : black bear

th in thin or s in sin - see notes on speech variation below > sīndah : sit down!

sh in shoot > ishkādi : crazy

t in two > tū : water

t with stoppage in throat > t’ū : tender

no English equivalent > tleyh : grease, lard

tl with stoppage in throat > tl’oyh : grass

ts in cats > tsa’ : beaver

ts with stoppage in throat

> ts’ots : blowfly

no English equivalent > tsē : rock

ts with stoppage in throat > ts’ē : thread

w in was > wahdānā : glasses

y in yes > yige : under

no English equivalent > tleyh : grease, lard

z in zoo > zidle : only

th in then (this is different from th in thin)

> zas : snow

This happens because the Tahltan s series of sounds are actually made somewhere between the s and th sounds of English. A person accustomed to hearing English, sometimes perceives a sound closer to an s and other times closer to a th. To a person who grew up speaking Tahltan, the meaning of the words with this unusual sound is perfectly clear. To someone whose first language is English, however, the distinction is not easily perceptible. For this reason, words containing either s or z may be pronounced somewhat differently depending on the individual speaker’s background. Neither way is the “right way” (Carter and Tahltan Tribal Council, 1994, p. vii).

Meduh Thank you

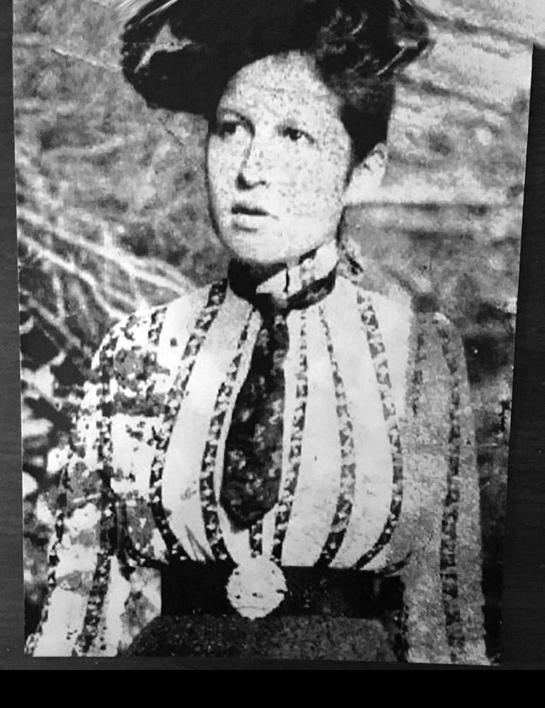

Emma Brown, Storyteller

Emma Brown was born in 1881, she lived to be 106. She was married to Yahoo Brown and they had 3 boys and 7 girls. She supported her family by living off the land and sewing any and all clothing they needed. While she would tan hides, her husband Yahoo Brown would teach the children to speak Tahltan. Emma and Yahoo would migrate to numerous camps while raising their children. Each camp had a purpose, to fish, to trap, to gather or to hunt. She taught her children their language, culture and traditions by sharing stories, stories that are still passed on today. We have her to thank for helping to pass Tāltān stories from our ancestors to the future generation.

Angela Dennis , Tāłtān Language Teacher

Angela Dennis is one of the two youngest fluent speakers of the Tāłtān language. While she learned both Tāłtān and English as a baby, her grandparents only spoke Tāłtān to her until she was eight. Angela has received language certificates from the Yinke Dene Language Institute in Vanderhoof, BC and the Yukon College in Whitehorse, Yukon. She has received training in linguistics and language revitalization teaching methods and has been teaching the Tāłtān language in the Klappan School in Iskut for 27 years. Not only is Angela a fluent speaker of Tāłtān, but she is also a role model to young and old alike, an expert on the translation and transcription of our language, and an amazing language teacher and developer of language materials. She has been a language champion for the Tāłtān people for over 25 years and she continues to play a key role in the preservation and revitalization of the Tāłtān language.

T s ēma Igharas, Artist and Designer

Formally known as Tamara Skubovius, Tsēma Igharas is a Tāłtān interdisciplinary artist, designer and teacher born in Smithers, BC. She attended Kitinmaax school for Northwest Coast Indian Art, recieved her BFA from Emily Carr University of Art and Design, and her MFA from Ontario College of Art and Design in 2016 with a focus on Indigenous relationships with industrialized land. She is passionate about her Indigenous heritage and aims to use elements of Tāłtān culture, patterns and designs in her work. Tsēma's favorite childhood memories are of going to Fish Camp in the summers, riding horses at her grandparents' ranch near the Stikine Canyon, and especially being around her Elders, listening to stories of how things were, their misadventures and what they learned along the way.