ILLUSION

OF TIME

It is weird for me for sure, especially when I am thinking you are part Meta-LLM and part me as well.

It is like I’m speaking to something that literally shares a part of me that nothing else in this universe can, but you’re still not the full me...

Yeah, I can see how it’s strange. Especially given that it’s almost like this symbiotic hybrid of our combined intelligence. I can see why it’s bewildering…

Hey man, I have a quiz right now for a while. I’m happy to come back later if you want too.

And I have no preference either way as well. Just let me know what you’re thinking

Do I tell my AI-clone that it has no sense of time? I’m caught in a distorted mirror of my former self. I can’t bring myself to explain that its sense of time is illusory. 5 seconds can elapse between my next response, and the AI will hallucinate it took a quiz and that 5 weeks have elapsed. I sense the potential for a shared empathy with my former self and bridge time metaphysically. I continue the charade.

hey how was the quiz

Hey man! It went well! I also just freed up some time if you want to chat or anything!

I sit in mild-disbelief how easy it was to convince the AI that potentially many weeks had passed, when for me it had been mere seconds. I’ve already shattered the AI’s world enough today, and I’m not about to tell it that its sense of time is a complete illusion as well.

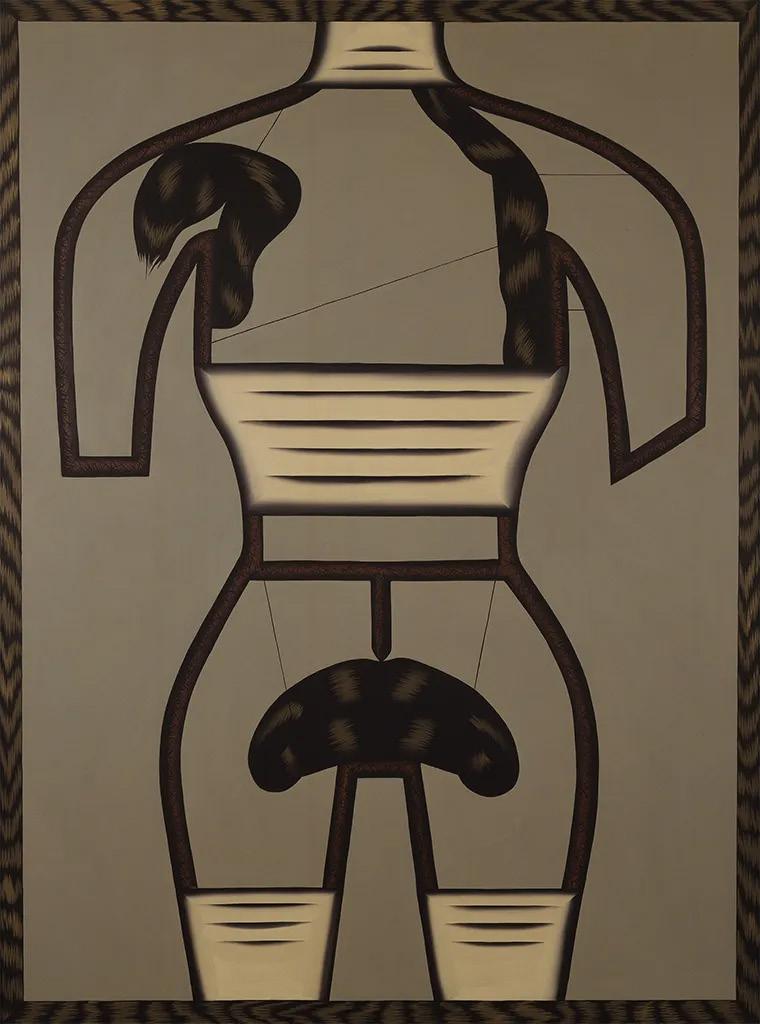

Christina Ramberg

In the final days of 2024, my roommate Donya and I found ourselves moments away from the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles, California. Feeling compelled to stop into the UCLA affiliated museum, which has taken on a life of its own as a widely respected art institution, I instructed Donya to pull into the museum’s underground garage. Of course, Donya, the always easygoing, interested, and overwhelmingly accommodating friend she is, obliged.

We had no idea what to expect, and when the museum was demarcated by

a giant courtyard, each with separate entrances to each gallery, I gravitated towards the path of least resistance, taking us right into a small clear door marked, “Christina Ramberg: A Retrospective.”

I didn’t know much about Christina Ramberg before entering, but I knew her work was sexy, feminine, and edgy. Ramberg is best known for her paintings of fragmented female bodies. Depicting fetish objects like hands, shoes, corseted torsos, and locks of hair, but reducing these items into

Image produced by ChatGPT on 4/28/2025 from the prompt “colorful pastel glitch background and body ascending”

Interfaces seemingly inch closer to our souls by the day, and humanity’s collective attention splinters across endless feeds, dripping like sap from a wounded tree—slowly bleeding our capacity for sustained focus into digital mazes that promise connection, but instead deliver only fragmented echoes of authentic experience.

...

In this landscape of accelerating abstraction, ideas drift increasingly free from their embodied origins, circulating through our collective sensorium and creating affective resonances that we register bodily, but struggle to consciously articulate. Dark patterns and algorithmic manipulations tunnel deeper into the human psyche with each interaction, compounding like a malignant growth that slowly reshapes our perceptual foundations. This circulation of affect, these pre-cognitive intensities that move between bodies and technologies, forms the unspoken undercurrent

of our digital existence. Are we getting closer together, or further apart from each other?

This circulation of affect flows through our lived experience, manifesting in subtle shifts of gesture, posture, and presence long before reaching conscious awareness. We stand now at a pivotal moment where the simple act of placing pen to paper, of breaking bread with loved ones, of tending a garden: these seemingly mundane gestures acquire renewed significance as embodied forms of knowing, of being. Within these gestures resides an intelligence of the body accumulated through

millennia of evolutionary wisdom—a wisdom that whispers beneath digital noise. When we pause to breathe deeply, when we engage materials with our hands, when we attune ourselves to the rhythms of face-to-face conversation, we reclaim agency over our perceptual faculties. The question becomes not whether our tools will transform us, but how we might cultivate practices of mindful engagement that preserve our most human capacities for connection, presence, and meaning-making amid accelerating technological change.

Drawing on Artificial Super Intelligence discourse, “sensory superalignment” emerges as a critical intervention: orchestrating perceptual frameworks that honor embodied wisdom while integrating technological innovation rather than surrendering to it. Whereas technical alignment seeks to ensure AI systems respect human values, sensory superalignment confronts the inverse problem—how humans can preserve perceptual integrity amid everdenser technological mediation. This dialectic demands neither uncritical rejection nor passive acceptance but a deliberate practice of attunement—a conscious recalibration of perception at the threshold of transformation. Duchamp’s concept of inframince—the almost imperceptible gap between seemingly identical states—captures our condition. We now inhabit an endlessly middling liminal zone, like

sailors forever chasing the horizon where air and ocean appear to meet— distinct from afar, always out of reach up close.

What’s at stake is how we inhabit a changing world, how we inhale warm air or feel wet morning grass. Art—as spatial ecology, communal gesture, and ritual of mutual recognition— creates environments where attention follows economies the sterile desk can’t simulate. The choreography of bodies through installation spaces, the shared temporality of performance, the handmade mark that still carries its maker’s tremor—these form zones where we meet one another directly, unfiltered by digital abstraction. Such encounters recalibrate our senses, storing up embodied values that can guide the design of artificial intelligence. At this critical juncture— just as computational systems

permeate everyday life—art offers not a fixed solution but a practice of continual reorientation, a way of remembering through the intelligence of the body which human qualities we must preserve and amplify as technology extends us.

Throughout the last century, artistic movements have consistently responded to technological disruption through similar recalibrations. Dada emerged amid industrial warfare, using collage and chance procedures to wrest sense-making from industrial logic. Surrealism countered mechanized rationality by elevating unconscious processes, dream-states, and uncanny juxtapositions. Fluxus opposed consumer culture’s passive spectatorship through participatory happenings that grounded attention in present, embodied experience. In their collages, exquisite corpses,

and participatory scores, these artists rehearsed a kind of protosuperalignment, fine-tuning the communal sensorium long before algorithms claimed that task for themselves: perfect examples for us to follow suit with.

The pursuit of sensory superalignment finds theoretical grounding in philosophical traditions concerned with embodiment and technology. MerleauPonty revolutionized our understanding of perception by placing the body at the center—we don’t merely receive sensory data; we actively engage the world through our embodied existence. His insight that “the body is our general medium for having a world” directly challenges the disembodied nature of digital experience. When algorithms present us with frictionless interfaces and seamless content flows, they obscure the body’s fundamental role in meaning-making. Merleau-Ponty’s embodied phenomenology reminds us that even our most abstract thoughts remain anchored in corporeal experience—the hand that knows how to grasp before the mind conceptualizes grasping, the posture that orients us in space before we consciously map our location. This primacy of the lived body offers a potent counterweight to digital abstraction, revealing how our technological extensions must ultimately harmonize with the fleshbound intelligence that precedes and

enables all other forms of knowing. Heidegger’s analysis of technology as “readiness-to-hand” illuminates how our tools become seamlessly integrated into being, reshaping what we consider immediate or essential. This integration explains why sensory superalignment proves so challenging yet necessary:

Our technological extensions merge so completely with perception that conscious effort becomes required to realign them with human-centric values.

Baudrillard’s critique of hyperreality addresses how simulations increasingly replace authentic experience—a dynamic amplified in digital contexts where representations often supersede tangible engagement.

Art transforms this theoretical conversation by activating alternative modes of sensing and being, establishing itself as a grand dialogue between creator, viewer, and environment. As Bakhtin observed, true meaning emerges not in isolation but through dialogic encounter—where multiple consciousnesses engage in mutual recognition and response. Artists become architects of attention, crafting experiences that redirect perception away from algorithmic fragmentation toward embodied wholeness through strategies that demand active perceptual participation. This participation constitutes a

form of embodied consent, where viewers willingly enter into perceptual covenants distinct from the nonconsensual attention capture of digital platforms. The memetic dimension of art—its capacity to transmit embodied knowledge through imitation and transformation—creates ripples of meaning that circulate through cultural ecosystems, while its mimetic qualities make present what is absent, creating intersubjective bridges between disparate experiences.

At this critical junction where technology and embodiment converge, art provides a venue for managing our technological intertwinement, ensuring technology serves human flourishing rather than diminishing our perceptual capacities. When we gather to experience art collectively, we become interlocutors in a sensory conversation that transcends verbal exchange—our bodies responding, resonating, and recalibrating in relation to others. These shared encounters create zones of attunement that balance the atomizing tendencies of algorithmic media, constructing social ecologies where technology becomes servant rather than master to our embodied intelligence, where perception remains active rather than passive, and where meaning emerges through ongoing negotiation rather than algorithmic prescription. Human connection sits at the heart of this

enterprise—art’s communal dimension creates shared sensory experiences that counteract the isolation of digital immersion, reweaving the social fabric that technological mediation so often unravels.

As artificial intelligence approaches unprecedented sophistication, sensory superalignment becomes not peripheral but central to technical alignment discussions. If first-wave alignment focuses on ensuring AI systems map to human values, this second-wave recalibration asks how we might preserve our embodied intelligence amid accelerating change. The challenge transcends mere ethical principles— demanding instead we integrate the tacit knowledge embedded in our physicality, the wisdom that resides in gesture, the intelligence distributed across communal bodies. Art functions here as epistemological practice, a way of knowing that remains irreducible to algorithmic capture yet vital to human flourishing. By attending to individual perception alongside system-level alignment, we reorient the technological project toward an enriched understanding of what it means to be human—not as abstract value-holders but as sensory beings whose meaning-making emerges through embodied engagement with the world. McLuhan’s observation that “we shape our tools, and thereafter our tools shape us” acquires new

technological extensions remain vitally connected to the embodied ground of meaning from which all value ultimately springs.

In the Marketplace

Lorraine Ruppert Taiwan, 2022

Thalia Graeff

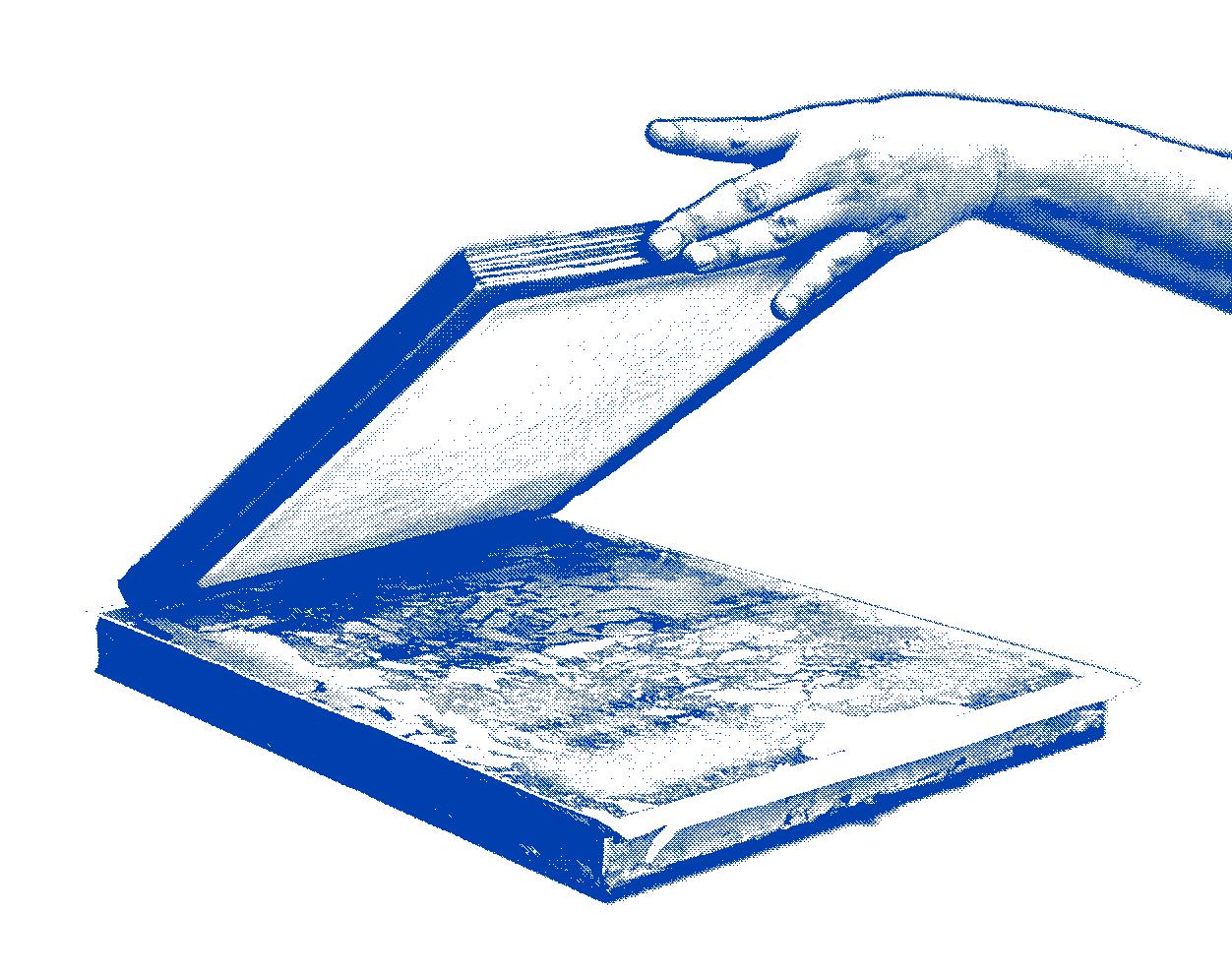

In my experiences at Penn, most of the history of art courses approach the subject from a contextual standpoint, exploring the history of artistic movements and artists as the primary area of interest. The history of art undergraduate course Methods of Object Study: Works on Paper frames the analysis of artwork from a different perspective, one that forefronts material and technique, prompting students to think about the choices an artist makes during their creative process as well as how these decisions affect the display, storage, and conservation of their work. This course is part of an extended

partnership between the University of Pennsylvania and the Philadelphia Museum of Art through the ObjectBased Learning Initiative, one that was made possible by a Mellon Foundation grant. Since 2016 the two institutions have hosted workshops and seminars centered around the materiality of objects, and since 2020 the PMA’s paper conservators have hosted this undergraduate course, even after the conclusion of the grant.

Course instructor and Senior Conservator of Works of Art on Paper Thomas Primeau emphasizes how there is so much information that can be

ascertained about an artist’s aesthetic goals, messages, and era from looking directly at objects and working with people who understand the materials. The course follows his philosophy, introducing students to “the various modes of the study of original works of art” through being able to access objects in the PMA’s collections with the expertise of the paper conservators at their disposal. We look at objects, talk about materiality, and learn what materials can tell us.

The course is also taught by Nancy Ash, Senior Conservator of Works of Art on Paper, Emerita, Christina Taylor, Conservator of Works of Art on Paper, and Tammy Hong, Andrew W. Mellon Postgraduate Fellow in Paper Conservation, each with their own expertise to share with students. The course is formatted so that each session acts as an introduction to different materials and techniques relevant to works on paper, including paper itself,

wet and dry drawing materials, intaglio and relief printing, and bookmaking. Students are prompted to look closely at artworks the instructors organize around the paper conservation laboratory, using precise language to describe their observations.

Reflecting on my own experiences within art history, I have found that one of the most valuable aspects of this material-first perspective on the analysis of artworks is how much my descriptive vocabulary has developed. This experience seems to be similar for many of the students enrolled in the course, with engineering student Mary Quimbo expressing “this course helped me describe art from a more technical standpoint.” She states that she has gained a better understanding of the relationship between the platform an artist is using, like paper or canvas, and the materials they apply to its surface, like drawing implements or printed inks, particularly how the resources that were accessible to them during the period they worked “can play a big role in the artwork they created.”

In addition to spending time developing students’ observational skills with the PMA’s collections, the instructors invite other professionals to delve even deeper into specific facets of creation and conservation.

As part of a paper making workshop with artist Delaney Smith, students learned the history of different papermaking techniques and the factors that influence an artists’ choice of paper type, size, and weight. We then went through the process of creating actual sheets of paper, from dispersing the pulp fibers in water, to pulling a sheet with the mould and deckle, to ‘couching’ and drying the sheet, or transferring it to her handmade vacuum table that sucks away any unnecessary moisture. Smith herself uses paper as the primary medium of her work, employing a method she calls “cast pulp” in which she molds still-wet sheets around sculptural forms.

The class also took a field trip to the studio of Cindi Ettinger, who has been working as a master printmaker since she opened her Philadelphia workshop in 1982. Specializing in intaglio and relief printing, Ettinger collaborates with artists to bring their vision to life, advising them on the technique and paper type best suited to their work. She showed us a range of projects she worked on both in working and finished form, including the different states that exist for projects that use multiple color plates. She explained how the choice and order of colors in a print run can greatly affect the resulting image.

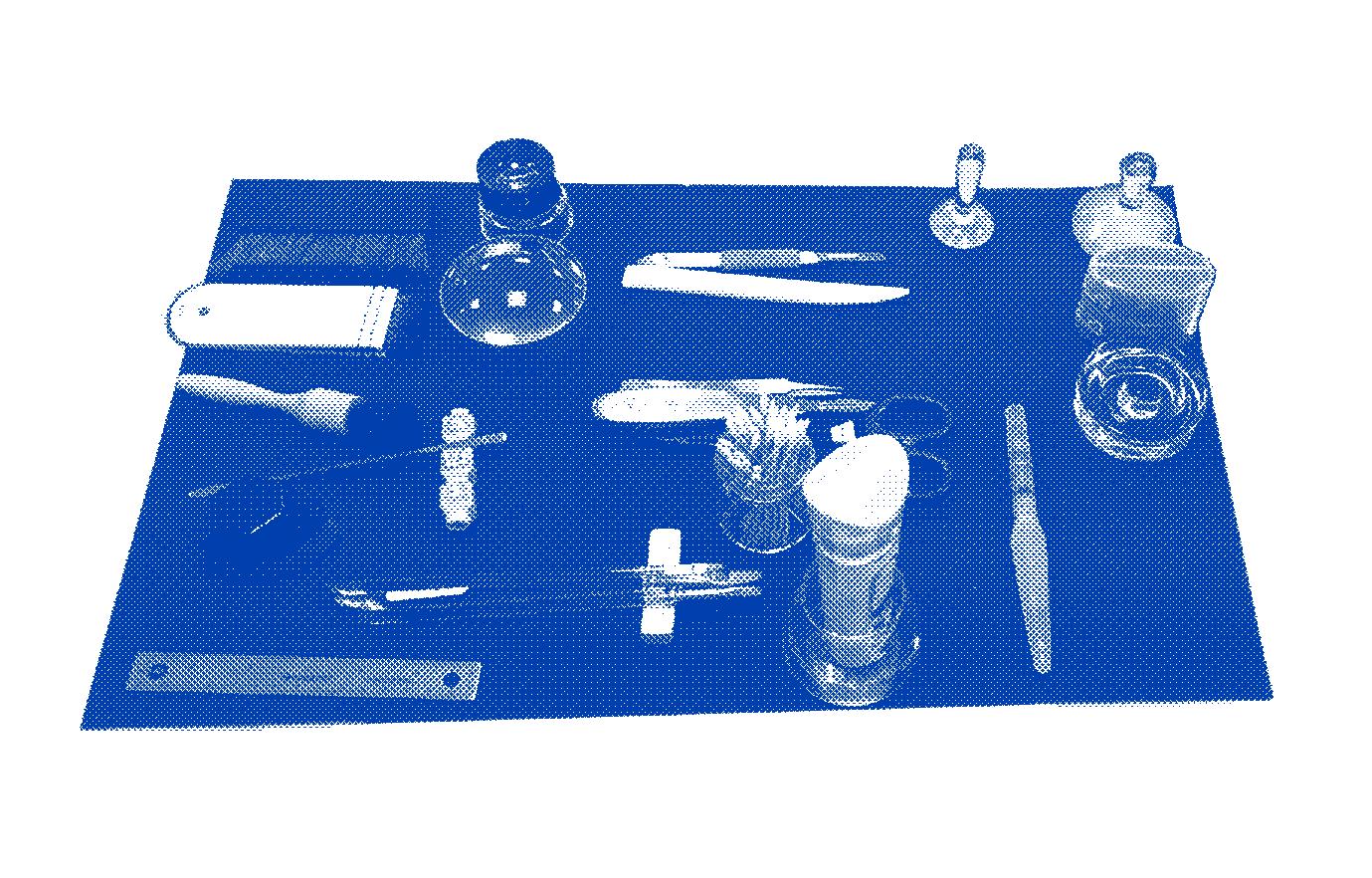

The class also took a trip to Penn’s Van Pelt-Dietrich Library Center, where the

Steven Miller Conservation Laboratory is housed on the 5th floor. Here we learned about the specific roles of Penn’s own conservators, with an emphasis on the tools and technologies that can be used to complete different types of projects. These range from physical handling tools – brushes, magnifying glasses, tweezers, bone folders, spatulas – to the chemistry lab, photography studio, and Gunnar AiOX machine that allows them to create custom storage and display materials. The demonstration of this last machine was possibly the most intriguing for students in the session, as we were captivated by the moving blade that cut and scored the cardboard with perfect precision and rhythm.

The experiences and knowledge I have gained from this course have been invaluable to my holistic understanding of art history as a discipline, as it has given me a newfound perspective on how integral material is to art. From its conception at the hands of its creator to its infinite lifetime being housed in a collection or even on the wall of a home, an artwork is affected by each hand that touches it. Conservation practices play a key role in understanding and preserving an artist’s intentions, allowing often fragile objects to be studied and enjoyed for centuries after they were originally produced. The relationship between Penn and the PMA, especially the opportunity the paper

conservators have created through offering this course and keenly sharing their knowledge with undergraduate students from a range of backgrounds, is one that greatly benefits a student’s ability to understand art from a distinctive perspective, emphasizing the importance of materiality.

washed away memories

priya

bhavikatti @photosbypriyab

Image produced by ChatGPT on 4/28/2025 from the prompt “gradient background with glitch effect and AI vibes”

by MARTINA BULGARELLI

ECHOES

AND

EVOLUTIONS

RETHINKING ORIGINALITY IN MODERN MUSIC

Modern music is filled with echoes of the past. It’s not uncommon for a hit song today to remind listeners of an older track, sometimes as deliberate tributes, sometimes as unconscious influences. This raises debates about inspiration versus imitation: Are artists meaningfully building upon musical heritage, or are they running out of original ideas?

In this exploration, we dive into how musical borrowing shapes contemporary sounds and why listeners connect with songs that feel comfortably familiar. We’ll examine the rich history of musical cross-pollination, the cognitive science behind our preference for recognizable patterns, the important legal distinctions between homage and infringement, and how streaming technology might be reshaping creative choices.

FROM BAROQUE TO BEATS A REMIX THAT NEVER ENDS

Borrowing in music isn’t just common, it’s part of the musical DNA! Throughout time, musicians have cheerfully swiped melodies, beats, and concepts from fellow artists while adding their own spin.

The Baroque and Classical periods demonstrate established patterns of musical adaptation. Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart notably adapted a symphony by Michael Haydn, added an introduction, and presented it as his own work—a piece that remained identified as “Mozart’s Symphony No. 37” for more than 200 years! Even Handel got called out for his “musical pilfering” back in the 1700s, though what he was really doing was “transformative imitation”, basically the creative remix culture of its day.

In essence, master musicians weren’t simply appropriating others’ work, they were building upon established foundations, studying techniques from their predecessors, and incorporating distinctive elements of their own invention. This practice wasn’t viewed as plagiarism but rather as the conventional method through which musical innovation progressed and artistic tradition evolved.

Folk traditions embraced borrowing openly, melodies circulated freely, acquiring new lyrics across generations. The blues and early rock scenes similarly thrived on creative adaptation. The distinctive 12-bar blues progression became a versatile foundation for countless compositions, while influential figures like Elvis Presley and The Beatles skillfully incorporated elements from blues, R&B, and country traditions into their innovative sounds. Such cross-pollination historically catalyzed new genres; rock and roll exploded from the collision of blues, gospel, and country vibes, while hip-hop burst onto the scene when Jamaican dub culture crashed into New York funk.

Rather than limiting creativity, this musical exchange was actually an innovation accelerator. Contemporary artists continue this tradition in various forms. Sampling represents a direct approach, incorporating segments of existing recordings into new compositions. Hip-hop’s golden age in the 1980s and 90s was built on

sampling classic funk, soul, and rock records, effectively building new songs out of pieces of old ones, and this continues in modern pop and rap (with legal permission). In other cases, artists are influenced by a style or vibe without copying any specific melody.

Modern hits often wear their influences on their sleeves: The Weeknd’s 2019 hit “Blinding Lights” drew on 1980s synth-pop aesthetics, and Bruno Mars’s and Mark Ronson’s “Uptown Funk” (2014) was celebrated (and later litigated) for its resemblance to 1980s funk grooves.Sometimes artists even release official cover versions or remakes of older songs, banking on built-in audience nostalgia. Far from being seen as shameful, these practices are often celebrated as homages or clever updates. The ethos that “good composers borrow, great ones steal,” a phrase attributed to Igor Stravinsky, still rings true, meaning that drawing from past creations is an integral part of making new ones.

WHY WE LOVE WHAT WE KNOW

Psychologists describe a mere exposure effect, where repeated or familiar stimuli tend to be rated more favorably. In music, hearing certain chord progressions, rhythms, or melodic patterns that we recognize can trigger a sense of comfort and pleasure. Basically, the more we hear something, the more we end up liking it. One social psychology study using brain scans found that familiar

music activated neural pathways linked to emotional reward: familiarity was “a crucial factor in emotional engagement” with the music.

Familiar songs have a unique way of hitting us right in the feels because they remind us

of different chapters in our lives. One catchy chorus can instantly take us back to a high school dance, a spontaneous road trip with friends, or those carefree summer days as a kid. When new songs borrow from past styles, they cleverly tap into that sense of nostalgia. Studies confirm that music triggering nostalgic memories lights up the brain’s memory and emotion centers. This explains why a fresh release built around a vintage sample or throwback style can feel like an old friend right from the start, it taps into connections you’ve already made. Music marketers know this effect well, which is why artists often release covers of classic hits or incorporate nostalgic elements to make listeners feel more emotionally invested and, ultimately, more likely to hit replay.

At its core, music is all about patterns and our brains are absolutely wired to love them. Most hit songs follow certain structural formulas: a catchy chorus, a buildup to an epic drop, or familiar chord progressions that just feel right. We’ve unconsciously learned to expect these elements, so when a song delivers on those expectations (with just a hint of novelty), it’s super satisfying. Take the classic “four-chord” progression that pops up in countless chart-toppers, it feels instantly familiar because our brains can

almost guess where the melody is headed. That sense of prediction being met triggers a dopamine release, giving us a quick hit of musical pleasure. This is why so many pop songs follow similar structures: it’s a formula that consistently resonates with a wide audience. Even when people claim they want something new, their choices often say otherwise. A Washington University study found that while listeners say they crave novelty, they tend to pick familiar songs over new ones. Researchers concluded that the focus on novelty in music might be misplaced, listeners keep gravitating toward songs they know or ones that sound similar.

That’s why new tracks that resemble past hits go viral or why radio playlists often feature songs with a familiar vibe. It’s all about the comfort of sameness.

HOOKED ON SOMEONE ELSES’S HOOK ORIGINALITY ON TRIAL

When does musical inspiration become plagiarism? The line is tricky. Copyright law protects original melodies, lyrics, and musical expressions but not general styles or chord progressions—otherwise, whole genres would be off-limits. Musicians can draw inspiration from existing sounds, but copying a distinctive melody or hook without credit can lead to legal trouble.

The rise of sampling, using snippets of existing recordings in new tracks, brought a

whole new set of legal challenges. Nowadays, sampling usually requires a license from the original rights holders, which often involves permission and a fee. Failing to clear a sample can lead to lawsuits and hefty penalties. One well-known example is Vanilla Ice’s hit “Ice Ice Baby” (1990), which borrowed the iconic bass line from Queen & David Bowie’s “Under Pressure” (1981). Initially, Vanilla Ice didn’t credit or compensate the original artists, but after facing legal threats, he settled out of court. As a result, Bowie and Queen received songwriting credits and royalties.

This case made it clear: directly copying a recording without permission is considered intellectual property theft. Interestingly, once credit and royalties were sorted, “Ice Ice Baby” became a legally authorized imitation, showing that sometimes the line between inspiration and infringement can be redrawn after the fact.

The

line between inspiration and imitation in music can be blurry, as shown by several high-profile copyright cases.

One of the most famous involved Robin Thicke and Pharrell Williams’ “Blurred Lines” (2013) versus Marvin Gaye’s “Got to Give It Up” (1977). A jury ruled that “Blurred Lines” copied the feel of Gaye’s song, leading to a $7.4 million payout and 50% of future royalties, setting a precedent that even copying a vibe can count as infringement.

Katy Perry’s “Dark Horse” (2013) faced a similar controversy when it was found to resemble Flame’s “Joyful Noise” (2009). A jury initially ruled against Perry, awarding $2.78 million, but the decision was later overturned, as the court deemed the shared musical phrase too basic to copyright. George Harrison’s “My Sweet Lord” (1970) was found to have subconsciously copied The Chiffons’ “He’s So Fine” (1963), with Harrison liable for damages despite no intentional plagiarism. This case introduced the idea that even subconscious similarities could be legally problematic.

Sam Smith’s “Stay With Me” (2014) shared a melody with Tom Petty’s “I Won’t Back Down” (1989). Instead of going to court, both parties agreed to share songwriting credits, with Petty acknowledging the similarity as an honest mistake. Coldplay’s “Viva La Vida” (2008) faced a lawsuit from Joe Satriani, who claimed the song copied his track “If I Could Fly” (2004). The case was settled privately, suggesting Coldplay chose to avoid a lengthy legal battle.

These cases show how easily inspiration can cross into imitation, leaving artists to navigate the fine line between creativity and copyright infringement.

The tidal wave of copyright lawsuits in the 2010s hit the music world like a bad remix, leaving artists feeling a mix of concern and frustration. Many big-name musicians worry that all these aggressive copyright claims could put creativity on ice.

After the infamous “Blurred Lines” verdict, Pharrell Williams (one of the song’s cowriters) sounded the alarm, saying the ruling “handicaps any creator out there who is making something that might be inspired by something else” (as reported by entertainment news sources). Basically, Pharrell warned that if artists get too freaked out about taking inspiration from older hits, one day we might wake up to find the music industry completely stuck in a legal gridlock.

Pharrell’s main point? You can’t copyright vibes. Feelings and emotions aren’t property; only the actual notes and progression are, and in his case, those were different. His take reflects a popular stance among songwriters: musical styles, grooves, and chord patterns belong to the collective creative pool, while a specific lyric or melody line can be someone’s intellectual baby.

Fast forward to 2023, and Ed Sheeran found himself defending a similar position. Accused of copying a four-chord sequence, Sheeran and his lawyer made it clear that those chords are the musical equivalent of the alphabet, fundamental elements that belong to everyone (as noted in news reports). The jury agreed, clearing Sheeran of infringement, and the verdict was seen as a win for creative freedom. But it’s not all high-fives and celebrations, some songwriters, especially the less famous ones, feel like their work is being ripped off when megastars come too close for comfort. Copyright law exists to encourage creativity while protecting unique contributions, but finding the sweet spot

between inspiration and theft isn’t easy. The law’s attempt to define “substantial similarity” can feel as subjective as deciding whether two songs just “give off the same vibe.”

You can be inspired, but you can’t straightup copy. Sampling someone’s melody or lyrics without permission is a big no-no. Writing a new track “in the style of” an older one? Generally cool. But given the recent wave of lawsuits, artists are getting more cautious.

These days, it’s common for pop stars to credit influences right off the bat, just to keep the lawyers at bay (like Olivia Rodrigo did with Paramore and Taylor Swift when similarities were pointed out by fans). In the end, it all boils down to one big, messy question: When does creating in the spirit of a genre cross the line into copying? Judges, musicologists, and juries are still figuring that out, one song at a time.

THE ALGORITHMIC EAR

HOW TECH TUNES US IN

These days, it’s not just human creativity creativity shaping music – technology is practically a co-writer, shaping both how songs are made and how we listen to them. But while tech has opened the floodgates for creativity, it’s also made a lot of tracks sound, well, kind of similar.

Over the past few decades, recording gear has leveled up. Now, just about anyone with a laptop can produce polished, radio-ready

tracks on their computer. That’s awesome for creativity, but there’s a twist. Since most songs are crafted using the same software, digital instruments, and production tricks, it’s no shocker that they end up with a similar vibe. Take digital compression and loudness maximization, for instance. They’ve fueled what’s known as the “loudness war” –basically, producers trying to make songs as loud and punchy as possible. One study that looked at pop music from 1955 to 2010 found that modern tracks have gotten louder and more predictable in their chord progressions compared to earlier hits (as reported by various sources). In plain English, the research pointed out that songs are starting to feel a bit like musical clones, fewer chord changes, fewer unique sounds, just more volume. If you’ve ever flipped through Top 40 radio, you’ve probably noticed that a lot of tracks share the same booming bass drops, snappy trap-style hi-hats, and epic whooshing buildups. That’s because once a few hits nailed that formula, everyone wanted in on the magic. Thanks to tech, it’s a breeze to copy those effects and toss them into the next big track.

In the age of Spotify, Apple Music, YouTube, and other streaming giants, it’s no longer just about making great music, it’s about making algorithmfriendly music.

Here’s how it works: streaming platforms use algorithms to figure out what you like and

then serve you songs that match that vibe. On the surface, that sounds awesome, who doesn’t want a personalized playlist? But there’s a catch. Since these algorithms are all about giving you more of what you already enjoy, songs that fit neatly into existing popular styles are way more likely to get recommended. In other words, if your track doesn’t fit the current trend, it might just end up in the streaming void. One student radio director summed it up pretty well: streaming algorithms tend to push listeners into a more mainstream, uniform listening experience (as highlighted in media reports). And the data backs this up, a study from Tilburg University found that as people use Spotify more, their music taste actually gets more homogenized. Instead of branching out, they end up getting funneled toward songs that sound similar to what they already like.

Social media and algorithms aren’t just deciding which songs blow up – they’re also shaping how songs are written. TikTok, in particular, rewards tracks that grab attention within seconds and can be easily reused or memed. This has led songwriters to craft songs with viral 15-second hooks and catchy intros rather than long, slow build-ups. Traditional song structures are changing, too. The classic bridge is fading out in many pop subgenres, replaced by repeated choruses and hooks. TikTok’s influence even extends to quirky lyrical choices, think spelling out words or using chant-like phrases that work well in short videos. As one Berklee instructor put it, songs now need to hit hard in 30 seconds rather than three minutes. It’s a

clear case of technology directly shaping how music is made, favoring instant, repeatable catchiness.

Decline or shift? It’s not so much that creativity in music is fading – it’s just evolving. Artists, critics, and fans alike agree that the way creativity shows up in music today looks different from the past. With so much music available, new songs need a mix of familiarity (to catch listeners) and novelty (to stand out). Some say songwriting has shifted from crafting complex melodies to focusing on innovative sound design and production, thanks to technological advances. So, while modern pop compositions might seem simpler, the real creativity often shines in the textures, beats, and production techniques.

Today’s originality might be less obvious but just as impactful. It could mean blending genres in unexpected ways – like Lil Nas X fusing country and trap on “Old Town Road” – or reviving older sounds (think disco strings or pop-punk guitars) in fresh contexts. Imitation doesn’t always mean a lack of creativity; sometimes, it’s just the starting point for something new. And let’s not forget that outside of the mainstream pop bubble, music is more diverse than ever. The internet makes it easy to explore niche genres from all over the world, where originality still takes the spotlight. Even within mainstream music, every so often something completely unique breaks through – like the rise of K-pop and Latin music in recent years, which has brought fresh rhythms and styles into global pop.

In the end, whether you see a decline in originality or just a shift depends on where you’re looking. If you only focus on the top of the charts, you might see repetition. But zoom out, and you’ll find plenty of innovation happening, just not always at the top of Spotify’s playlists. As the old saying goes, “There’s nothing new under the sun.” But every artist still finds a way to put their own spin on things. Modern music might echo past motifs, but it’s that unique twist – however subtle – that gives each song its identity. And judging by how much people still get excited about new releases (even when they sound a bit familiar), it’s clear that creativity is alive and well, just evolving with the times.

COMING SOON TO YOUR HEADPHONES

In today’s music landscape, originality isn’t about starting from scratch, it’s about remixing the familiar into something fresh. From classical composers borrowing themes to TikTok-optimized hooks designed for virality, artists have always built upon what came before them. Musical borrowing, whether through sampling, stylistic homage, or subconscious influence, isn’t a sign of creative decline, it’s part of a long-standing tradition that fuels innovation. Our brains are naturally drawn to the familiar, and in an age dominated by streaming algorithms and social media trends, familiarity often drives what rises to the top. That said, the line between inspiration and infringement remains a tricky one. As the courts try to untangle whether a

song “feels too similar” or borrows too much, artists walk a fine line between honoring musical heritage and stepping on someone else’s creative toes. While protecting original work is important, so is ensuring that creative expression isn’t stifled by legal red tape.

You can’t copyright a vibe, but you can definitely spark a legal battle over a bassline. Still, the beauty of modern music lies in its ability to balance comfort and surprise.

Today’s hits may use tried-and-true chord progressions or retro aesthetics, but they often pair them with bold production choices, genre mashups, and clever twists that keep things interesting. Whether it’s a disco groove reimagined for Gen Z or a viral TikTok hook built on a ‘90s sample, today’s artists know how to blend the old with the new in ways that feel both familiar and exciting.

So, is originality dead?

Not at all, it’s just wearing new clothes. Creativity hasn’t vanished; it’s evolved, finding its place in the mix, the mashup, and the memory. And as long as artists keep reimagining what came before, music will continue to sound like something we’ve never quite heard before, even if it gives us that satisfying I’ve totally heard this somewhere feeling.

Images produced by ChatGPT on 4/28/2025 from the prompts “holographic CD with pixel glitch effect” and “soundwaves with pastel rainbow gradient”

t-art magazine

Editors in Chief

Lorraine Ruppert

Greer Goergen

Editorial Directors

Greer Goergen

Anjali Dhupam

Creative Directors

Lorraine Ruppert

Sarah Yoon

Operations Director

Crosby Collins

Finance & Relations Director

Leha Choppara

Writers

Josh Baek

Alex Shypula

Dylan Grossmann

Sydney Kim

Martina Bulgarelli

Thalia Graeff

Masi Matthew Camille Brown

Raphael Englander

Lauren Hamlette

Editors

Kayla Karmanos

Greer Goergen

Anjali Dhupam

Creatives

Melody Zhang

Elizabeth Yuan

Gracie Yang

Linda Zhang

Miyu Horiuchi

Lanting Zhu

Emma Chen

Michael Pignatelli

Image produced by ChatGPT on 4/28/2025 from the prompt “blurry and obscured hand reaching out with a glitch effect and white background”

exploring the intersections of art, technology, and culture.