FUTURE OF CONFLICT Page - 05 INDIA - AN NOVATION POWERHOUSE? Page - 23 LESSONS FROM UKRAINE Page - 17 LEARNING FROM THE NEIGHBOURS Page - 39 INTELLIGENCE OVER CENTURIES Page - 54 EXCLUSIVES MEDIA ENABLED OCTOBER 2022 |MONTHLY EDITION LOOKING BEYOND THE CURVE SYNERGIA FOUNDATION FUTURE OF CONFLICT OUTER SPACE, DEEP SEA AND CYBER

INSIGHTS is a strategic affairs, foreign policy, science and technology magazine that provides nonpartisan analysis of contemporary issues based on real-time information.

To subscribe, sambratha@synergiagroup.in ; +91 80 4197 1000

https://www.synergiafoundation.org

EDITORIAL

We at Synergia Foundation pride ourselves on our ability to look beyond the curve and dabble with the unknowns. Security today is developing into a multidimensional collage with conflict domains spilling over into new and existing conflict areas. Outer space, the deep oceans, including seabeds (as remote to mankind as the deep space) and, of course, cyberspace, are the emerging domains for international competition and, worse, military conflicts.

This is the lead story in this edition, where experts from India and abroad with varying backgrounds expound their theories. With this issue, we have barely scratched the surface of this vast subject, and we will persist with digging deeper into its intricacies in our future issues.

Technology is yet another of our focus areas, and in this issue, we have tried to understand where India stands in the Global Innovation Matrix. For a country our size, it is a pity that the number of patents issued to India globally is minuscule.

This has to change if India wishes to stand tall in the community of nations. In the same vein, we draw insights into DNA as a potential method of data storage in the future.

Our neighbourhood is important for India’s future prosperity. We examine Indo-Bangladesh relations as our neighbour completes its 50th year of liberation. On this occasion, we also see where democracy and freedom of expression are headed in that country through the experiences of its public with its Digital Security Act.

Internationally, we have looked at the political landscape of the UK with much interest, not the least because a person of Indian origin has created a record of sorts by occupying 10 Downing Street. We will be tracking his performance regularly in our future issues too.

Our partner in BRICS, Brazil, has undergone a wrenching Presidential election that has driven deep fractures into the national psyche, a phenomenon many other great countries are also undergoing; we examine the elections and their fallout.

We have examined fake news and disinformation on the social media scene, which have undermined people’s trust in social media and the internet. We hope our esteemed readers will continue supporting us as we strive to further evidence-based research on strategic issues with global resonance.

Sincerely yours

Dear Friends:

Greetings

from the Synergia Foundation!

SCAN THE QR CODE TO SUBSCRIBE

Maj. Gen. Ajay Sah Chief Information Officer

economic ecosystem in which future prosperity depends on safeguarding the ‘global commons’.

Future conflicts will occur in outer space, the deep ocean and the cyber world.

Technology has enabled the control of the threedimensional battlespace in ways that were not possible, or even imaginable, a few years back.

When even the redoubtable Xi Jinping can be ‘toppled’ by malicious peddlers of fake news, it is time to sit up and take notice.

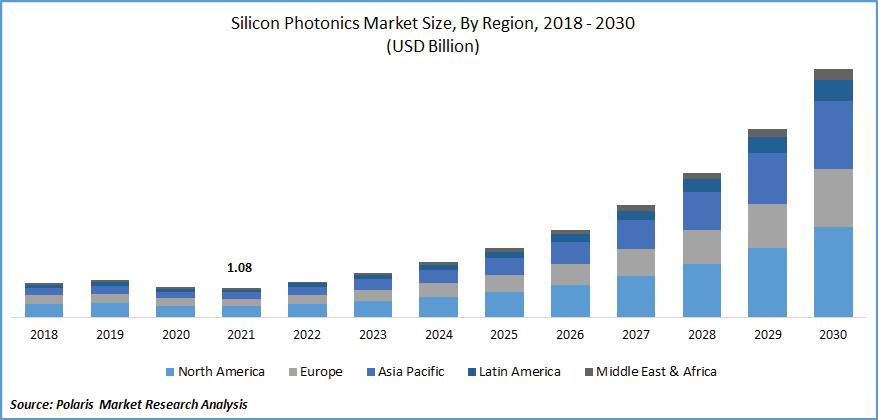

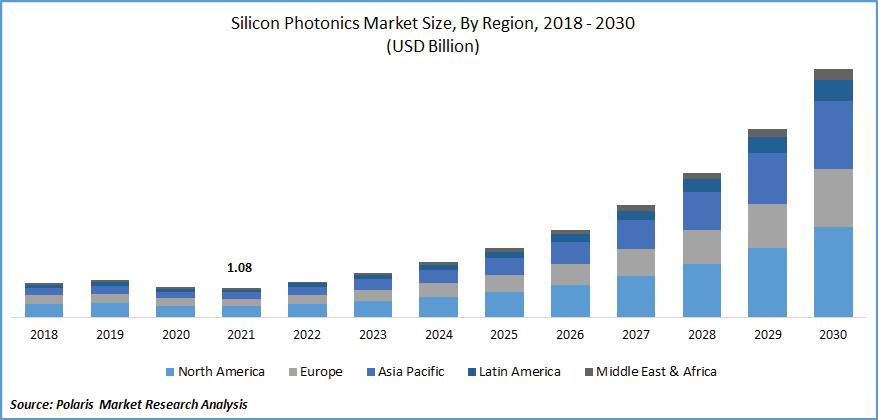

The photonics industry has the potential to drive technology in the post-law Moore’s era, making silicon photonics a critical technology.

As India prepares to roll out a comprehensive ‘Digital India Act,’ it would be best advised to study its implications as experienced in other countries.

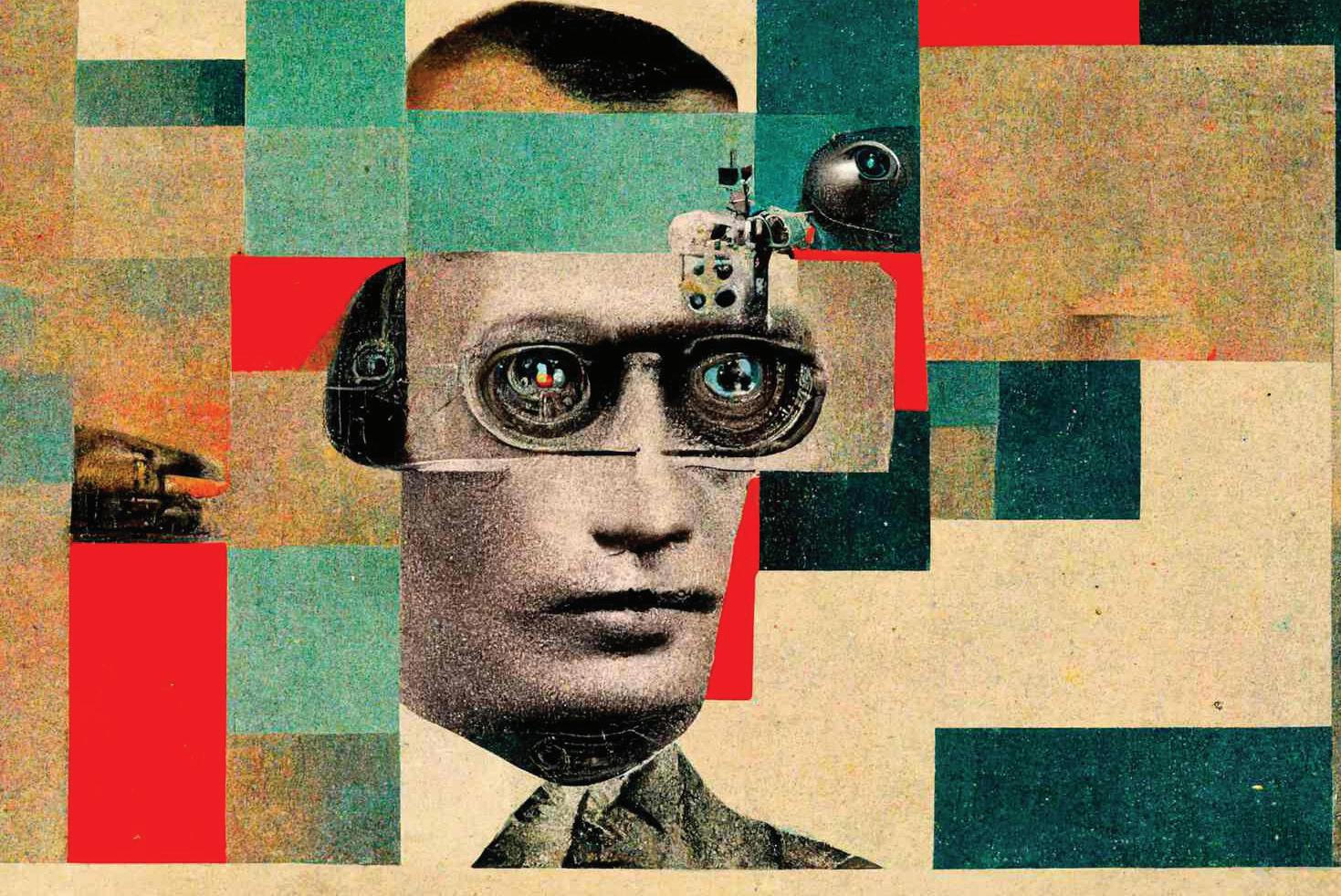

With the era of technology at flank speed, AI is poised to permeate into decisionmaking at the political level

Without clearly defined rights, it is natural that the oceans are susceptible to competition, confrontation and conflict.

The war in Ukraine has been a test bed for many new weapon systems and concepts.

Data storage devices are changing every few years, rendering legacy systems outdated; this must change.

HUMAN INTEREST

Space networks are vital for a nation’s economic growth and military potential.

Innovation takes place in almost every field, be it business models or how organisations are designed to be more efficient. However, innovation is ultimately technological.

While the Indo-Bangladesh relationship has matured well over the last 50 years, there is still much to be done to make it lasting.

Wrong decisions at the highest level have cost nations dearly, with consequences faced by their citizens.

With a mere 45 days in office, Ms Elizabeth Truss has the dubious distinction of being the UK’s shortest termed premier!

From near total political oblivion, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva crawled back into the Palácio do Planalto in an election tainted by untruth and manipulated polls.

The so-called Russia-China axis is transforming in its shape and dimensions post the Ukraine war.

China considers linking the ‘East’ Sea and the ‘West’ sea under its maritime domination as the first step towards global primacy.

Guatemalan refugees find themselves caught between the devil and the deep blue sea on being returned to a country that cannot sustain them.

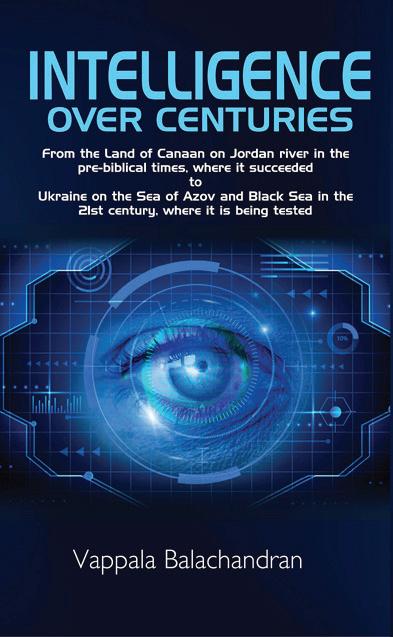

author of ‘Intelligence over centuries’, spoke for the 138th Synergia Forum at Synergia Foundation.

EXCLUSIVES COVER STORY SECURITY TECHNOLOGY TECHNOLOGY TECHNOLOGY TECHNOLOGY ASIA SECURITY ASIA SOUTH AMERICA SOUTH AMERICA AUTHOR’S COLUMN FUTURE OF CONFLICT THE THREAT TO GLOBAL COMMONS INDIA AND EMERGING DOMAINS OF WARFARE SHRINKING BATTLESPACES UNDERSTANDING THE MARITIME DOMAIN LEARNING FROM THE NEIGHBOURS SNAGS TO SOLUTIONS OUTER SPACE AS A KEY CONFLICT DOMAIN A STRATEGIC ALIGNMENT IN THE EAST? CHINA’S LONG MARCH TO HISTORIC GLORY INDIA - AN INNOVATION POWERHOUSE? LEARNING FROM NATURE THE HUMAN FACE OF POLICY BLUNDERS A RETURNING PROBLEM A NAIL-BITING FINISH INTELLIGENCE OVER CENTURIES SETTING A NEW RECORD! LESSONS FROM UKRAINE A TALE OF PARADOXES FAKE NEWS: MAKING NO DISTINCTION! SILICON PHOTONICS: THE NEXT TECH REVOLUTION? PAGE 5 PAGE 3 PAGE 11 PAGE 08 PAGE 14 PAGE 39 PAGE 41 PAGE 21 PAGE 23 PAGE 43 PAGE 45 PAGE 47 PAGE 50 PAGE 52 PAGE 54 PAGE 30 PAGE 33 PAGE 17 PAGE 27 PAGE 35 PAGE 37 Mapping the path of potential conflicts in space is critical for the peaceful exploitation of the medium. The 21st century is a globalised

SECURITY

SECURITY

GEOPOLITICS

THE THREAT TO GLOBAL COMMONS

The 21st century is a globalised economic ecosystem in which future prosperity depends on safeguarding the ‘global com mons’, which are defined as ‘domains that no one state controls but on which all rely’.

Maj. Gen. Ajay. Sah SM, VSM (Retd), is the CIO at Synergia Foundation, with experience in conflict resolution, peacekeeping and counterterrorism.

The face conflict is transformative and changes with technological advancementand changes with technological advancements, the need for greater resources and the unending avarice of great powers for economic and geopolitical primacy. Artificial Intelligence (AI) and quantum computing are some realities that are redefining conflict land scapes and cyberspace has become the lifeblood of our civilisation.

The geostrategic environment too is undergo ing changes, driven by increasing complexities of relationships between nation states and their indi vidual military and economic capacities. Conflict arenas threaten to break out from their traditional domains to new ones—outer space, the deep ocean, the Arctic. All these are predicted to store immense resources that will extend significant strategic ad vantages to the first exploiters.

FUTURE PROSPERITY

The 21st century is a globalised economic ecosystem in which future prosperity depends on safeguarding the ‘global commons’ defined as ‘domains that no one state controls, but on which all rely’. Today, these comprise of the mari time, the aerospace and cyber domains. The maritime do main includes the surface and, yet unexplored ocean depths and resource- rich ocean beds, and undersea mountains.

Conflict arenas have the potential to break out from their traditional domains to new ones-outer space, the deep ocean, including the Arctic, as these are considered to have immense resources and will provide significant strategic advantages to the first exploiters.

Aerospace includes the skies and the infinite space above it, with outer space beginning above the earth’s surface from where objects can remain in orbit. Cyberspace is a digital world created by an interconnected global network of com puters. Even if its physical infrastructure may be parked in individual countries, its global linkages make it a global common.

Every nation, rich or poor, has an unrelenting interest in protected access to the global commons. The international community must collaborate to secure the high seas for the fre flow of commerce and its depth for protecting the deli cate marine ecosphere, the space for the free exploitation of satellite-based technology for fast communication and the cyber world for a free flow of ideas and as a seamless medi um for the flow of e-commerce.

SHAPING THE GLOBAL SECURITY ENVIRON MENT

The international security environment may well be come ever more unstable, uncertain and complex as new technologies usher in new economic and security impera

tives and geopolitical compulsions. While ocean depths remain largely the last frontier on earth, with only a very small fraction explored/ exploited, outer space and cyberspace are fast emerging as the latest arenas of competition and conflict. Countries must be able to anticipate, deter, and, if required, fight threats in ocean depths, space and cyberspace.

Ocean surfaces have long been the most used glob al commons and have played a singular role in devel oping international trade. Since freedom of navigation in international waters is well- regulated, the focus now should be on the development and exploitation of ocean depths and the seabed.

The ocean seabeds are not within the jurisdiction of individual countries. Part XI of the UNCLOS denotes the seabed, ocean floor and subsoil thereof – called the Area – including its mineral resources as the common heritage of mankind (Art. 136 UNCLOS).

While the rich and powerful states wish to com mence mining activities in the seabed, others are de manding a moratorium on any such activity till an international regulatory regime can be put in place. A first come, first serve; exploratory gold rush is bound to result in international tension and potential conflict situation.

Apart from the traditional use of space for commu nications and surveillance, commercial enterprises in tend to invest huge resources in space mining. Moon, asteroids, and other space bodies are reported to be a source of rare metals like platinum. Ongoing research is looking at harvesting water from the Moon and Mars for use as rocket fuel by breaking it into constituent oxygen and hydrogen.

The immense challenges thrown by space’s working environment demands great efforts and huge expenses for countries to exploit it. We, therefore, do not need conflict and military competition to make it even more demanding by raising fresh barriers to its peaceful use. Without proper regulation and conventions, chaos in space can spell disaster, if not doom, for planet earth itself.

As more and more countries and an expanding list of commercial entities reach out to space for commercial exploitation, space debris becomes a real lethal danger.

Putting conventional/ laser/ nuclear weapons on orbit ing platforms is even more worrying. Therefore, norms must be set for the use of space for all purposes. The role of small states and international law in the extrater ritorial expansion of extraction cannot be ignored any longer, as all have a stake in the peaceful exploitation of space.

Cyberspace is an acknowledged theatre of conflict today, with cyber intrusions, attacks and cloning being the weapons of choice. The terminology of cyber war fare is becoming ever more a mirror image of tradition al warfare, with trojans, malware and worms taking the shape of gunpowder and shot.

Rules must be set for cyber security and attribution. Some countries resent the dominance of the western al liance in the cyber domain and demand new definitions, management and regulation of the information-driven world with greater equality. Existing regulatory con cepts must be critically examined to decide on the next generation of regulatory norms within globally accepted principles.

THE WAY AHEAD

Nations, big and small, will have to contribute their share of soft and hard power to ensure that there is a fair and measured use of public goods from these global commons.

What will each nation bring to the table based on its economic strength and military capability? How will the expenses for such a global effort be met? All these questions demand an answer. Multilateral organisations must cobble together regulations and conventions, like the UNCLOS, for both outer space and cyberspace.

These conventions must be enforceable and not re main confined to treaty papers only. The current rising global tensions between various global powers must be stabilised through the creation of other multi-polar ar chitectures.

By analysing security precedents and adopting best practices, a structure that can voluntarily promote ad herence to global norms, establish well- defined stan dards of conduct and create a system of legal coercion to deter those who disregard global regulations and norms, is the need of the hour.

Conventional forces must be adept at thriving in contradictions of geopolitics and geo economics. They will either be at the centre stage or at the edge in deterrent mode always!”

LT GEN (DR) SUBRATA SAHA

PVSM, UYSM, YSM, VSM** (Retd), Director, School of Military Affairs, Strategy and Logistics, Rashtriy Raksha University and former Dy Chief of the Army Staff.

04 THE THREAT TO GLOBAL COMMONS

FUTURE OF CONFLICT

The paradigm of Future conflicts will likely originate from four vectors, namely Counterterrorism, Grayzone conflicts, Asymmetric fights, and Unmanned combats.

The understanding of the future of conflict helps fundamentally align the interest of the buyer, the manufacturer, the strategy picker, and the vendor.

Critical Emerging technologies are changing the hieroglyphs of combat. Expeditious ad vances in unmanned systems, robotics, data processing, autonomy, networking, and other ad vanced technologies have the potential to give fresh impetus to an entirely new warfighting axiom. Both state and non-state actors will seek to profit from these new technologies, many of which are impelled by the market dictates of innovation in information technology.

The impending is replete with uncertainties, and any realisation of combat is an onerous task. Several vectors will shape conflicts, including geopolitical, societal, technological, economic, spatial, environ mental and military trends.

In deliberating warfare, we often gravitate to prepare for the last war, think of using military con cepts or technology that may be outdated or focus on previous battle-winning strategies, which are, or will soon be, outmoded. Both great and middle pow ers are investing not only in offensive capabilities but also in asymmetric warfare tools like cost-effec tive drones. It is possible to conceive that the mili tary and civil societies might end up being the prime target in a future conflict.

A deeper understanding of the contours of fu ture conflicts helps fundamentally align the interest of the buyer, the manufacturer, the strategist, and the vendor. It would not be in the interest of any of

these stakeholders to plan or build inventories with out visualising how the theatre of conflict will pan out in the coming years. When Synergia Foundation quizzed several vendors, buyers and policymakers on what they felt would be the future conflict in the region, few had good answers.

LOOKING BEYOND THE CURVE

A few fundamental features of conflict will remain un changed in the future.

First, conflict is, and will remain, an unprecise science; it will remain unpredictable and uniquely human activity. Second, the qualitative advantage can no longer be assumed in the future. Third, RMA or revolution in military affairs focused on concepts of rapid effect, leading to a belief in the late 20th and 21st century that major powers could define wars; this, too, might not hold in the future.

Fourth, adversaries will be able to achieve tactical suc cess because of their access to cheaper technology, whose rate of adoption will be faster even by non-state actors and low-income countries. Fifth, the motives for engaging in conflicts have been described as the concept of pure honour and national interest; In the future, countries are likely to use military instruments for reasons of fear.

Sixth, the centrality of influence could be essential in the coming years. If the character of a nation’s military prowess were defined by its ability to conduct precision strikes on

Tobby Simon is the Founder and Pres ident of the Synergia Foundation and a member of the Trilateral Commission.

Tobby Simon is the Founder and Pres ident of the Synergia Foundation and a member of the Trilateral Commission.

enabled platforms and command modes, conflict out comes would likely focus more on the centrality of in fluence in the future.

Our adversaries have already recognised the impor tance of influencing public perception and will continue to develop this and use it increasingly in a battle of the narrative. This is not just a matter of improved public affairs or perception. This takes place in a decentralised network and free market full of ideas, opinions, and even a set of raw data, which will immediately weaken the influence of mainstream news media.

Breaking events will be increasingly transmitted to individuals at an ever-higher tempo, often without government or editorial filters or legal sanctions and safeguards. Although propaganda is well-established and frequently demonstrated, modern technology will amplify its shock. Future conflicts will be primarily de termined by ‘whose narrative wins.’

Seventh, technology affects how a force can fight and the credibility of that force to deter. However, the vanguard of technological development is shifting to wards the commercial sector, which, typically, is more agile than the military it supports, and it is moving to the East. Eighth, the prime driver of innovation is not technology but people.

Ninth, Procurement programs that take decades may be obsolesced in an afternoon by new technolog ical innovations. Tenth, the most significant military danger here is unplanned escalation. If satellites fail to communicate and operational personnel sitting in their underground command bunkers can’t be certain of ground realities, it would be extremely hard to calibrate the next move.

CONCLUSION

The future of conflict will challenge military forces structured and prepared for an industrial age war be tween global powers.

Conflict is evolving but is not getting simpler: the range of threats is expanding. Some seemingly inferior adversaries will be able to achieve tactical success be cause their access to alternative sources of technology will improve, their rate of adaptation will be faster, and the cost will be significantly lower.

EXPERT VIEW

A TECHNOLOGICAL PERSPECTIVE

Space and cyber domains have emerged as the new strategic enablers for any nation aspiring for great pow

er status and remain the key to national security for military and economic reasons. In the globalized world, there is competition between commercial interests and national interests. The Cold War between the U.S. and China reflects the same. Within this spectrum, there is a wide array of actors, both state and non-state with a variety of interests- economic, military and ideological.

SPACE AND CYBER LINKAGES

Societal dependence on networks results in an in creased number and sophistication of attacks target ing critical infrastructure and institutions. Especially worrying is the asymmetric capabilities that are within reach of non-state actors and the hybrid nature of mod ern warfare. Cyber threats manifest themselves against space systems through Kinetic-Physical, Non-Kinetic Physical, Electronic, and purely Cyber, making their counters extremely complex to design and apply. This increases the aperture of access to space systems from both state and non-state actors, especially since, unlike other critical infrastructures (CI), space systems are not as well a protected environment.

THREATS TO SPACE INDUSTRIAL CAPACITY

The nascent space industrial base is increasingly im portant to national and global economies. It is particu larly vulnerable to malevolent actors since the overall efforts to protect national capacity are not sufficiently integrated. Potential adversaries recognize the impor tance of assured space capabilities and thus would at tack such capabilities with cyber and other means. Con trolling key supply chains feeding space capabilities is even more important since these are now distributed over a large geographical area. Since space research rep resents an important segment of national security in novation bases, this, too, is endangered by multifaceted threats.

The future of National Security shall be based on technological deterrence. The strength of the economy and military are both based on technological edge.

LT GEN PJS PANNU PVSM, AVSM, VSM (Retd) is a former Deputy Chief of Integrated Defence Staff responsible for Integrated Military Operations.

BRIG GEN R. MAZZOLIN (RETD)is the Chief Technology Strategist at the RHEA Group.

BRIG GEN R. MAZZOLIN (RETD)is the Chief Technology Strategist at the RHEA Group.

06 FUTURE OF CONFLICT

AIR MARSHAL ANIL KHOSLA, is PVSM, AVSM, VM, ADC who served as 42nd Vice Chief of the Air Staff

NEW DOMAINS: A REALITY

New Domains in the conduct of warfare have opened new vistas in the defence industry. Warfare be ing as old as mankind itself has evolved, just like the human race. This has been enabled by a regular dose of technological innovations. Being genetically a quarrel some species, man has needed little cause or incentive to seek combat, be it for basic survival, for ego, or the greed for resources.

Man’s inquisitiveness has driven him to seek new domains to conduct the deadly game of war. It was a natural transition for warfighting to transcend from the terrestrial battlefield to air, to space, the oceans, and the depth of the oceans, and now even into ethereal cyberspace. AI, artificial intelligence, nanotechnology, and robotics, singly and in combination, are giving rise to unmanned platforms of various sizes and capabilities with the ability to operate in the air, surface, sea, and subsurface.

EMERGING DOMAINS

Space was seen as the new frontier for the betterment of mankind; a natural corollary being its militarisation by the few and the powerful ones.

Space is considered critical for communications, nav igation, targeting, etc., and has tremendous potential for military applications. Space-based Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance (ISR) is a prerequi site for any military campaign, as is being showcased in Ukraine and other conflicts. Hypersonic weapons placed in orbiting platforms or transiting through space are the next-generation missiles coming online.

Not surprisingly, the counters to such space-based weapons are also being developed at a frenetic pace. The airpower of yesteryears is now upgrading itself to aerospace power.

Similarly, cyber, which influences every aspect of our lives, has been weaponized. Cyber warfare is conduct ed surreptitiously and continuously without the decla ration of a state of war between nations. There are no frontiers nor recognizable combatants- a teenager with a powerful laptop can be an equally deadly adversary! Offensive cyber operations are characterized by ambi guity and deniability.

The lines are blurred in this kind of conflict, referred to as the grey zone operations. Their counter would re quire consistent monitoring of systems backed by AI, robust concepts, and standard operating procedures to safeguard assets.

The difficulties associated with operating at great depths of the oceans had kept man’s war outside this domain. But now, things are changing as technology has given us the capacity to go deeper and stay longer at ever-increasing depths.

The vast resources of untapped natural wealth hidden in the depths of our oceans invest in deep-sea explo ration technology worth the cost. Ocean depths act as conduits for the carriage of marine cables carrying in ternet signals, and data, as also, increasingly, gas pipe lines transferring energy from one continent to anoth er.

New platforms are being developed, both manned and unmanned, which can reveal the depths of secrets and help colonize the ocean beds for exploitation and mili tary applications.

OPPORTUNITIES FOR THE DEFENCE IN DUSTRY

Unmanned platforms are needed to wage warfare in every domain- on land, air, sea, sub-surface, and space. In military aviation, the concept of a loyal wing man is gathering traction where the advantages of both manned and unmanned platforms are exploited.

Drones have established themselves as a dominating weapon system in all battle conditions, and the race is now on to find an effective antidote for them. Manned platforms are still relevant, and advanced nations are already looking at 6th and 7th -generation fighters that possess immense computing power and can operate in all the emerging domains.

In the modern networked battlefield, sensors play a vital role. Multi-domain sensors powered by AI to han dle a large amount of data are now coming up for ISR. AI will have a role in almost all weapon systems, espe cially in network operations for data collection, analy sis, planning, dissemination, and monitoring. Training is another area requiring integrated solutions of live, virtual, and simulated because physical on-ground training is becoming exorbitant.

Greater emphasis is being given to protective infra structure for individual soldiers and the sophisticated systems and platforms from kinetic and hyperson ic weapons and more lethal chemical, biological, and radiation weapons. All electronic systems must have military-grade hardening from EMP. Underlying all this development is the need to be self-reliant in the defence sector. R&D is important, and that too capable of continuous technology infusion as weapons systems become obsolete rapidly.

In a country like India which lacks a private-run military-industrial complex, there must be a fusion be tween the defence industry and the civil segment. Du al-use technology must be processed on parallel tracks so that its application in military and civil domains is seamless. This will also ensure better interoperability between the two sets of equipment.

EXPERT VIEW

07 FUTURE OF CONFLICT

SHRINKING BATTLESPACES

Technology has enabled the control of the three-dimensional battlespace in ways that were not possible, or even imaginable, a few years back.

SYNERGIA FOUNDATION

SYNERGIA FOUNDATION

RESEARCH TEAM

RESEARCH TEAM

The outer space battlefield is no more science fiction and hypersonic anti-glide missile is harder to detect on radar than a ballistic mis sile. Today there is a clear connection between space and warfare. Watching the war unfold in Ukraine while sitting in your home on TV, beaming satellite/ drone imagery gives a clear sense of this linkage.

Space borne sensors make it impossible to hide. If the enemy is caught in the open, existing sensors can bring to bear long-range precision strikes at a moment’s notice. Technology has enabled the control of the three-dimen sional battlespace in ways that were not possible, or even imaginable, a few years back. The implications of such a ca pability are clear in Ukraine, where fast-moving mechanized columns are being picked up and destroyed in detail as easi ly as in a video game. In terms of warfighting concepts, it has a profound impact, forcing warfare into ever- diminishing spaces..

One key implication is that if you can match long-range strikes and the ubiquitous sensors that can see everywhere, it forces opposing sides into close spaces. The best example of this was the operations jointly conducted by Iraq and its American allies to push ISIS out of northern Iraq. This was largely a battle for a series of cities and vast open spaces where western coalition airpower and, of course, space sen sors could see and, with precision strike, pulverise anything in the open.

The only way that ISIS could equalise the battlefield was to withdraw into closed spaces. Only once in the closed spaces could they coalesce, form organised bodies, and then resist retaining control of the terrain.

Pundits of strategy tend to predict the dominance of long-range strikes coupled with ubiquitous sensors and supported by operations in the electro-magnetic spectrum, in space and in cyberspace. These systems are being projected as networks with the power to link the optimal sensor to the optimal available effector to attack the optimal target for the optimal effect- a kind of ‘battlefield of internet of things’.

IMPACT ON THE MARITIME DOMAIN

The other implication is if you translate the idea to mar itime spaces and given the emerging range and precision of land base strike and anti-ship weapons, the outcome could be equally disruptive. There is a potential now for landbased systems to strike out to a thousand kilometres at sea; potentially, you can exercise not just a denial but sea control from the land.

That becomes important because if once naval forc es had the luxury of disappearing into the vastness of the open ocean and then reappearing in unexpected places, this cannot happen anymore. The land-based attacker with missiles has the advantage. Also, land-based missiles can be dispersed while the same cannot be done on a floating plat form like a missile destroyer. Thus, we may be witnessing an advantage of the land domain over the maritime domain. This has significant consequences for a primarily land-based power like China.

The principal problem is that if you want to restore some

manoeuvre to the sea and land battlefield, how do you get across these new ‘no man’s land’ or anti-access area denial bubbles? How do you move through those safely? If defence enjoys an edge over the offence, where does it place huge, expensive, and powerful platforms like nu clear-powered aircraft carrier groups that are the back bone of U.S. power projection capacity? Are their days over? Should we look for solutions to problems like the operational dilemma militaries faced along the Western Front in World War I to get over the frozen fronts and get through the crust of hardened defences into depth areas?

THE FUTURE OF CONVENTIONAL LAND FORCES

Pundits of strategy tend to predict the dominance of long-range strikes coupled with ubiquitous sensors and supported by operations in the electro-magnetic spectrum, in space, and cyberspace. These systems are being projected as networks with the power to link the optimal sensor to the optimally available effector to at tack the optimal target for the optimal effect- a kind of ‘battlefield of internet of things’.

Defining the vision of future warfare as ‘neat, tech nical, distant and inhuman’ creates an impression that conventional warfare capability is made redundant. In some critics’ minds, there is little, or no role for forces designed for ground combat other than minor stabili zation operations done in conjunction with the UN like the Solomon Islands and Timor, especially in the con text of the Indo-Pacific. The question frequently being asked is why engage in close combat when you can sim ply destroy your enemy from a stand-off distance?

Five broad assumptions lead the experts to such a conclusion. These are first, the tendency to conflate battle and war. Second, the discussion about future wars is largely a context-free zone. The third is to over estimate the capacity of human imagination without giving credence to our inability to read the future accu rately. Fourth, is to take a superficial view of the effect of new and emerging technologies on warfare. And fifth, making the geography of a particular area a restrictive factor for the development of conventional land forc es, even if that force may at times be deployed in other geographies.

Let us not ignore the fact that technological advanc es in the 20th Century that were expected to diminish the importance or necessity of close combat did not do so. To that end, those like Julio Douhet and airpower theorists of the 20th Century who hoped that technol ogy would preclude long and bloody wars in the future

One key implication is that if you can match long-range strikes and the ubiquitous sensors that can see everywhere, it forces opposing sides into close spaces. If you translate the idea to mari

were proved wrong in World War II and the Cold War period.

Speedy and relatively bloodless victory in war through sophisticated targeting and long-range strikes is likely to prove just as elusive as all previous attempts at the same. New and emerging technologies might, like the technologies of the First World War, just as easily contribute to a new form of long and bloody wars of at trition.

As we have already discussed, missiles, sensors, and the other things we now call multi-domain capabilities - things like space, cyber and electronic warfare – dom inate contemporary thinking about warfare, which is right, to a point. But it is not the whole picture. There has been too much focus worldwide on the systems themselves and their immediate and superficial conse quences rather than how the combination of new tech nologies will affect warfare.

Long-range precision missiles, combined with ad vanced sensors, give the defender the potential to cre ate killing zones with enormous depth encompassing the air, sea and land. We have seen in Eastern Ukraine and in Nagorno-Karabakh, how the density of modern sensors and strike systems might mean that in the fu ture they could become resilient against long-range pre cision counter-strikes and other methods of neutralisa tion. Tactics that once allowed an attacker to maneuver in the face of fire and close with an enemy might be come too expensive and uncertain to attempt.

There is a lot of discussion on the Nagorno Kara bakh conflict where it is claimed that drones and pre cision munitions won the war for Azerbaijan. But there is another perspective to it; the precision strikes and real time intelligence from drones set the conditions for light infantry and special forces to physically clear the trench line and capture territories.

A lodgement on a shore protected by an enemy armed with a sophisticated ‘kill web’ might be all but impossible without incurring decisive losses of people and machines. So, if this new-age strike complexes do favor the defender so decisively, perhaps the most dif ficult and important challenge is working out how to manoeuvre in the face of an adversary’s anti-access en velope. How to restore the balance in warfare between the defender and the attacker back to a more neutral setting? One way, of course, is to seize the initiative and hold the key terrain from the outset. The future for ma noeuvre forces looks a lot like small infantry/ tank teams operating in intimate cooperation.

time spaces and given the emerging range and precision of land base strike and anti-ship weapons, the outcome could be equally disruptive.

MAJOR GENERAL CHRIS SMITH is the Deputy Commanding General in the U.S. Army Pacific Command located in Hawaii. He has earlier served as the Director General of Operations of the Australian army.

09 SHRINKING BATTLESPACES

INDIA & NEW WARFARE DOMAINS

Future conflicts will occur in outer space, the deep ocean and the cyber world, with technology driving the change.

Air Marshal Anil Chopra, PVSM, AVSM, VM, VSM is a retired Indian Air Force retired officer and former Adminis trative Member of the Regional Bench of the Armed Forces Tribunal at Lucknow.

Outer space holds out the promise of resourc es and vantage points, while hidden, un charted natural resources lie in the depths of the ocean. The cyber-world is a parallel universe where all action takes place at the speed of light with near-instant effects on our world. Combined or standalone, all three domains have economic, geo political, and military linkages. Indian security cal culus must consider the vast technological changes that are taking place almost daily in all these do mains.

AEROSPACE & INDIA

Air and space will be the primary means of prosecut ing wars in the 21st century. Space will support situational awareness, communication, navigation, and targeting, and the the dominance of aerospace will be a war-winning factor.

The Indian space programme is almost as old as modern India, having been established as a research institution soon after independence. Acknowledging its importance, the De partment of Space was placed directly under the Prime Min ister’s office.

Consequently, today, India is one of the only six coun tries in the world with full launch capability and the ability to deploy cryogenic engines, launch extra-terrestrial mis

Air and space will be the primary means of prosecuting wars in the 21st century. For many decades, one who controls air and space controls this planet.

sions and operate large fleets of satellites. As an upcoming space-launching entity, India has launched 346 satellites for 36 countries, with 114 for domestic use alone. The GSLV Mark III using a cryogenic engine can put 4000 kg in geo stationary orbit and 8000 kg in Low Earth Orbit (LEO). Although this pales before the Chinese Long March rocket that can take nearly four times or more of payload, it is still a significant achievement. More powerful rockets are under development.

An advanced space research group has been formed to give direction to space research. There is a well-developed network for space operations, tracking, and analysis called NETRA. It will help the country track intercontinental bal listic missiles, anti-satellite weapons, and possible spacebased attacks. Meanwhile, we are excitedly waiting for India's first human spaceflight and the Indian Space Station by the end of this decade.

The Indian Regional Navigation Satellite System (NAV IG) currently has eight of the eleven satellites in place, and it covers all of China, Pakistan, and most of the Indian Ocean. The Global Indian Navigation System (GINS) with 24 satellites is a work in progress. Indian military satellites provide a reasonably good day and night picture resolution to serve the security needs of the defence services. In 2019, India became the fourth nation to carry out a successful an

ti-satellite weapons test.

Space is fast getting crowded with satellites with over 3500 nano or cubeSATs that have been launched for scientific data, radio relay, networking, ISR, and other military applications. A small satellite constellation can be launched rapidly using less powerful launch vehicles to build constellations of 1000-plus satellites or nano satellites. India joined the race last month by ferrying 36 satellites of New Space Indian Ltd in its LVM3-M2, the most powerful launch vehicle in its stable.

NEW DEVELOPMENTS IN SPACE TECHNOL OGY

Electric and nuclear propulsion for satellites and spacecraft is evolving, and plasma thrusters would cut down the spacecraft’s weight. Radio isotropic, thermo electric generators, and atomic batteries to power the spacecraft are new action areas

India now has a significant number of private play ers and start-ups. The Defence Innovation The unit will help facilitate interaction between the armed forces and private industry. The Defence Space Agency based in Delhi will ultimately mature into a Space Command.

India needs more satellite launches for continuous coverage, faster revisit, and redundancy in its surveil lance. There is a need to enhance jam-proof ISR ele ments and EW capability

India is wary of the Chinese space programme that is making rapid progress. China has more annual or bital launches than the U.S. and all Asian coun tries combined.

They placed a rover on Mars in 2021 and their Yaogan satellite templates allow the Chinese military to maintain constant sur veillance across the South China Sea, Western Pacific, and Indian Ocean. The Chi nese Global Navigation Satellite System is operational, and their Tiangong space station is coming up very quickly. Eyeing the trillion-dollar industry, resource-hungry China is rapidly develop ing technology for asteroid hunting.

ARCTIC CONTESTA TIONS

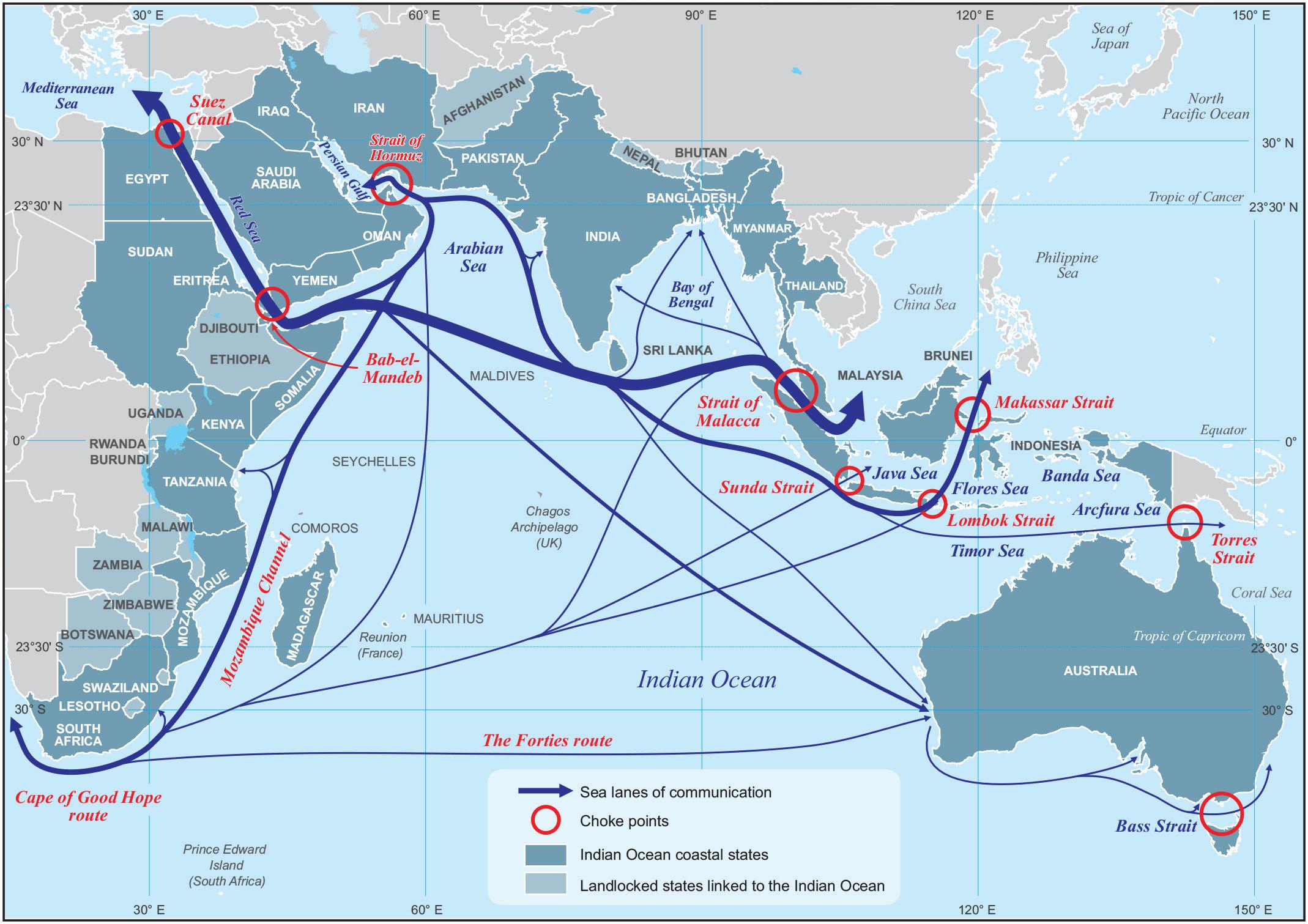

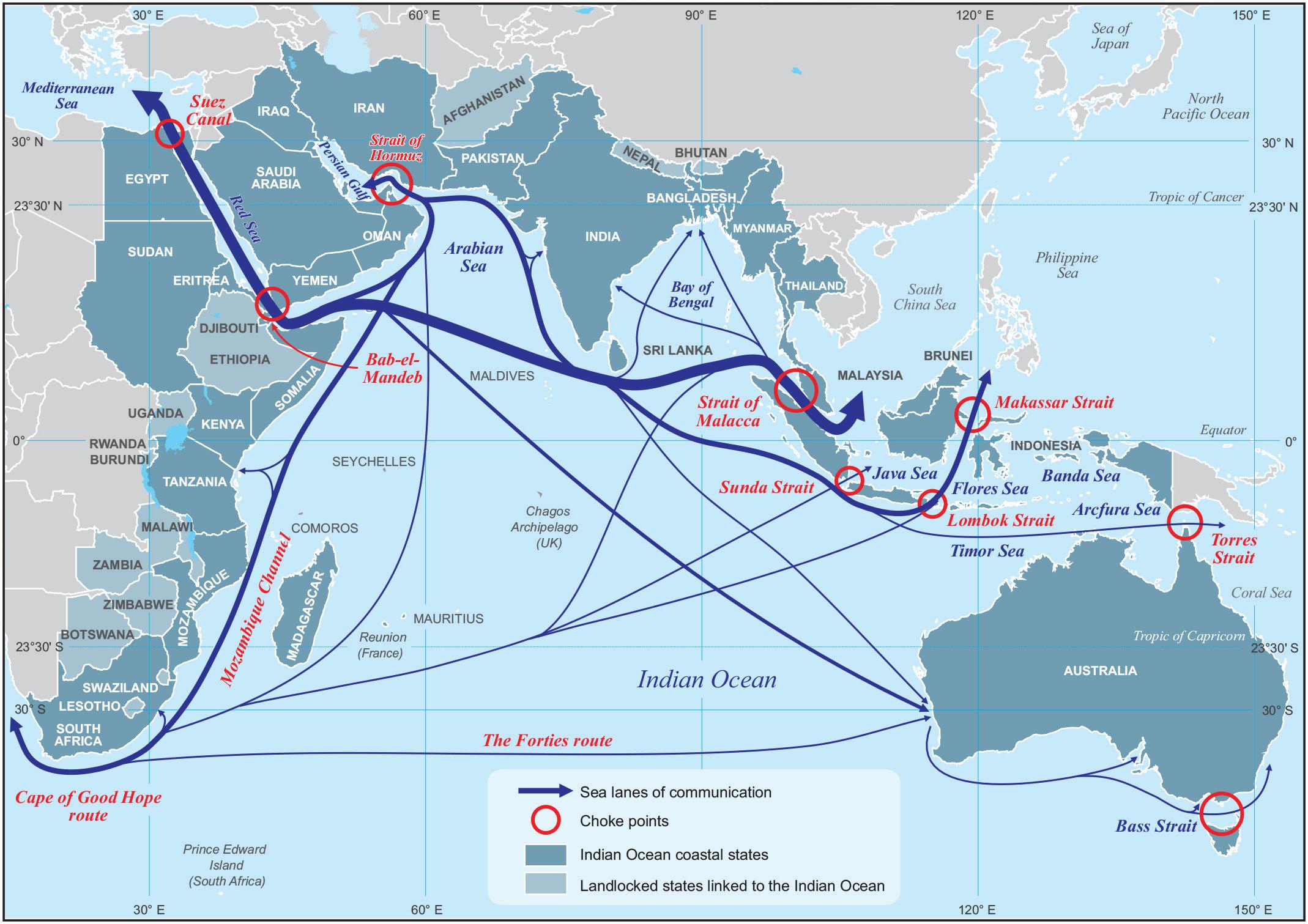

The maritime domain includes the surface and yet un explored ocean depths, resource-rich ocean beds, and undersea mountains. The bulk of in ternational trade passes through the seas. Since the natural resources and manufac tured goods are available in geo clusters,

most sea lanes pass through well-known choke points, which must be secured.

Two areas are seeing increased international ten sion: the South China Sea, where China has usurped nearly 3 million sq. km of EEZ by creating or all claiming islands, and the Arctic region.

The Arctic covers over one-sixth of the earth’s land mass and is set to play an increasing role in shaping the course of world affairs. The still-less-explored region is rich in exploitable natural resources, especially gas, oil, and marine life. Global industrialization has raised the temperatures. Therefore, the glaciers are rapidly melt ing. The 2021 minimum sea ice extent was around4.7 to 4 million km², which is around a 1.6million km² lower than the long-term average.

The Arctic Sea ice reduction has been at a rate of around 13 percent per decade, which is very high. Some Arctic countries want to exploit the resources, especial ly oil and natural gas uncovered by the melting ice.

The melting ice is also creating more maritime routes. Normally they should be treated as natural wa terways, but territorial claims may restrict open access. It could open a sea route in the northern parts of Can ada, connecting the Pacific and the Arctic Ocean in the summer months.

It will certainly shorten some sea routes and reduce transportation costs. Both Russia and the United States have for long placed weapons, including nuclear weap ons, in the Arctic region and have a significant

With the West and Russia drawing into a fresh showdown, the once cooperative approach is tending to break down. China has become a significant player in the Arc tic and is reportedly spending more on its Arctic endeavors than even the U.S. It has been building military and other capabilities to defend its interest in the region and has an aggressive Arctic

China plans a solar silk route through the Arctic to help expedite glob al shipping delivery. China considers itself a near-Arctic state and a ma jor stakeholder. In 2018, Shanghai-based Cosco Shipping Cor poration made eight transits through the Arctic between Europe

12 INDIA & NEW WARFARE DOMAINS

Through the Arctic shipping route, the maritime shipping distance from Shanghai to Hamburg is around 7000km shorter than the southern route, which passes through the Malacca Straits and the Suez Canal.

India has a permanent Arctic research station in Norway. Since July 2008, India’s ONGC Videsh has been interested in investing in Russia’s Arctic liquefied natural gas projects.

Though the Arctic Sea route does not significantly reduce the sailing time for Indian shipping, the deep sea around the Arctic is rich in silver, gold, copper, manga nese, cobalt, and zinc. The new robotics and AI solu tions minimize environmental damage and improve the economics of extraction.

However, since deep-sea mining is a relatively new field, the complete consequences of full-scale mining operations on the ecosystems are still unknown. Some researchers claim that removing parts of the sea floor will result in disturbances to the benthic layer and in crease the toxicity of the water column.

Assessment

Space, the open ocean, and the cyber are always considered global property for free usage. However, the militarization of space, arbitrary claims and control over open seas, serious offensive action, and cyber threats have muddied the water.

It requires coordinated rule-based international action to rectify the situation. Appropriate treaties need to be reworked and implemented based on natural justice and not on might is right. For this, the UN and the International Courts must be given greater power and teeth.

EXPERT VIEW

COLONEL BALJINDER SINGH, is director of Aerospace and Defence of the United States-India Strategic Partnership Board. He served for 29 years as a soldier-engineer in the Indian Army in various terrains.

Space and Cyber domains present opportunities to field formidable new instruments for attaining power parity among nations. Unfortunately, space is accessi ble to only very few countries. The space capabilities of countries vary; the U.S. and Japan have been into it for a considerably long period and have already gained a lead by creating National Space Forces; Russia, China and, lately, India has a demonstrated anti-satellite capacity in space.

In the 19th Century and the early part of the 20th Century, sea powers ruled not only the waves but also the continental world. Even today, deep oceans and air have become a strategically important combination for technology adoption. The availability of rare minerals in the deep oceans and rising demands for fish as a source of food have added stress in the maritime domain. The consumption of fish per capita in 1960 was 97 kg per head; today, it has dipped to 30 kg.

Manganese is available in pea plants off the coast of New Guinea. The reserves are said to be almost 8 per cent as compared to 0.6 per cent available on land. Gold’s availability on the seabed is reportedly three to five times higher than on land. Marine cables for inter continental communications and data connection are highly susceptible to sabotage. In 2013, two divers on the Egyptian coastline had sheared off certain cables, which blacked out many Arab countries. Such periods of communication blackouts could be exploited to launch physical attacks.

13 INDIA AND EMERGING DOMAINS OF WARFARE

Source : Proxy Drone War! by Emad Hajjaj

UNDERSTANDING THE MARITIME DOMAIN

Without clearly defined rights, oceans are susceptible to competition, confrontation and conflict.

Vice Admiral Anil Chopra, PVSM, AVSM is a retired Indian Navy Flag officer, who served as Flag Officer Command ing-in-Chief Western Naval Command from 2014 to 2015.

The Seas have been a tangible medium for hu manity since the dawn of man. Upon them have plied global trade and food and energy supplies sustaining the world, as also invading arma das and powerful carrier groups projecting military power to every corner of the planet.

COOPERATION & COMPETITION

Themaritime domain has been and always will be vital for the prosperity and security of all nations and for its abil ity to influence or even dominate others. The seas have al ways been a Global Commons, albeit a contested one. The acceptance of parts of the maritime domain, such as terri torial waters and exclusive economic zones (EEZ), is now restrictive to some extent.

However, elsewhere, the freedom of navigation remains enshrined, both under international law and as an age-old custom amongst seafaring nations. There are no property rights at sea, and the ocean does not belong to any coun try, organisation, or company. In the absence of Rights, it is natural that the seas are susceptible to competition, con frontation, and conflict. And this is unlikely to change in the foreseeable future.

The potential for maritime cooperation is regrettably always eclipsed by militaries pursuing their nations’ inter ests for access to resources, energy, and markets. Military

There are no property rights at sea, and the ocean does not belong to any country, organisation or company. In the absence of Rights, it is natural that the seas are susceptible to competition, confrontation and conflict. And this is unlikely to change in the foreseeable future.

conflict leads to instability at sea and impacts the ongoing trade. Even those not party to the conflict are affected by rising shipping costs because of uneconomical routing, and increased insurance outlays on commercial shipping. It is, therefore, in the interest of all nations to strive for a peace ful oceanic environment and general maritime security.

AN EVOLVING DOMAIN

Over the past hundred years, the maritime domain has been transformed by two distinct developments.First is the replacement of customary and traditional international law by the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), which came into force less than three decades ago in 1994. UNCLOS grants state legal rights to various zones adjacent to their coastline.

It lays down a comprehensive regime for governing mar itime activities. However, this territory realization of the seas has given rise to many disputes, differences in interpre tations, and transgressions, most visibly in the South China Sea.

The United Nations and the International Maritime Or

ganization (IMO) have the authority but not the means to enforce the convention. Consensus between nations on contentious clauses is necessary for unanimous ac ceptance and ratification.

Secondly, and most tellingly, the humongous impact of exponentially accelerating technology; has complete ly revolutionized maritime battlespace and warfare as well as marine transportation and communications. Since the advent of the 20th century, starting with ra dio and then through radar and satellites, the maritime environment has become increasingly transparent. It has become easier to detect, identify and track ships, submarines, and aircraft operating at sea. Furthermore, weapons and ammunition have vastly increased in range, speed, accuracy, and lethality.

Seagoing platforms are now more accessible to ki netic action from the surface, subsurface, and airborne dimensions. Even from land-based weapon systems, the vulnerability of platforms has increased. But concur rently, sea platforms using a variety of hard weaponry and soft countermeasures, including stealth technology and damage control, have enhanced their survivability. The same, however, cannot be said of commercial ship ping.

MAJOR TECHNOLOGICAL INNOVATIONS

The immediate and near future at sea will undoubt edly be shaped more by multiple technological advance ments than by treaties and conventions. Six technologi cal developments have been the most impactful.

Firstly, the increasing overlay of the maritime do main by space and cyber mediums, which are being rapidly militarized. Modern surveillance, communi cation, disruption, and deception capabilities impact all aspects of the detection, identification, targeting,

Fourthly, the return of mass or quantity to warfare. Contemporary naval ships, submarines, and aircraft or enormously expensive and are manned by equally ex pensive, highly trained manpower. As the cost soars, it becomes unaffordable to field them in large numbers, even for superpowers. Autonomous uncrewed plat forms are far cheaper and could be inducted literally in hundreds, operating in swarms to overwhelm ene my defenses. Fifthly, long-range precision weapons at hypersonic speeds, striking deep Inland from the sea, making almost every urban center targetable from the sea at short notice by platforms operating in interna tional waters. Last but not least, directed energy weap ons using high-power lasers to destroy targets at the near instantaneous speed of light.

THE WAY AHEAD

Sinceinternational institutions, such as the United Nations, have neither the requisite authority nor the enforcement capability to maintain global security, the occurrence of military conflict will depend on nations; propensity to abide by the sanctity of borders. Respect for sovereignty, which has been fundamental to the Westphalia system of a nation- states since the 17th cen tury must endure.

There’s a need to reform both the UN and the Unit ed Nations Security Council and legislate a convention that governs the imposition of automatic penalties, in cluding economic sanctions upon states which do not adhere to the accepted rules of international law. How ever, in the real world, this is easier said than done. The only mechanism that works is a balance of power strong enough to deter rogue nations from resorting to the il legal use of force.

Due to the nature of the medium, it is impossible to create barriers between military and civilian domains at sea. Commercial shipping and other civilian assets for belligerents locked in combat un-demarcated battlespace will lead to collateral damage to the assets of neutral nations, includ trawlers and sci search ships. As the Ukraine war has shown, offshore supply chains will be dis rupted, bringing chaos to global commerce and

Peace on the waves needs a global and re gional balance of power that will encourage deterrence through mutually assured destruction. Mutual econom ic interdependence could be another way to dissuade hostilities, as there are no winners in an all-out war. Lastly, a coalition of willing must take on the task of en forcement of the rule of law, as was seen when piracy

15 UNDERSTANDING THE MARITIME DOMAIN

INDIA’S INDIAN OCEAN?

The Indian Ocean is increasingly becoming a poten tial zone of conflict as strategic competition spills over from the Pacific and the South China Sea.

As the economic balance of the global market shifts to the East, the Indian Ocean Region (IOR) has increasingly gained prominence and strategic im portance. After all, the Indian The ocean is the most heavily used link between the West and the East, with around 80 percent of the global sea-borne trade tran siting through its choke points. Many experts believe that being sandwiched between the South China Sea and the Persian Gulf, the Indian Ocean Region (IOR) has generally been ignored. While the Freedom of Nav igation has been emphasized in the IOR, especially by the U.S. Navy, from time to time, there have been areas that have lacked a strategic focus, like the increasing frequency of violent acts of piracy and pollution.

CHALLENGES IN THE IOR

The geography of the Indian Ocean presents two significant challenges for maritime enforcement of peace and freedom of navigation. Littoral countries have extended coastlines of over 200 nautical miles generating massive EEZs. Even small nations like Mau ritius and Seychelles can stake claim to EEZs which are amongst the top 25 globally. This makes maritime se curity operations complex and difficult to coordinate with the littoral. The second challenge is maintaining a robust maritime domain awareness (MDA). Due to the massive size of the maritime domain of many of the Indian Ocean Rim Association (IORA) member coun

tries, the very heavy density of traffic on its sea lanes of communications (SLOC), the blurred line between legal and illegal activities on international waters, and the small/ nil maritime capacity of many of the nations, MDA is difficult to achieve by any single power.

Therefore, the load for MDA would devolve upon a few nations; Australia, India, Iran, Malaysia, Thailand, and the UAE, which have capable maritime forces (na val and coast guard) in terms of quality and quantity.

INDIA’S CALL

The strategic vacuum in the IOR was not destined to last indefinitely. The rise of China, the increasing pres ence of the PLAN off the Gulf of Aden for anti-piracy operations, growing Chinese maritime capabilities (like the development of carrier groups), and engagement with IOR countries started ringing alarm bells. The possibility of the ongoing tensions in the South China Sea spilling over into IOR is now a distinct possibility. India has a stake in its security as a major geographical constituent of the IOR. India is uniquely positioned to influence the Indian Ocean maritime domain from its bases on the West and East coast. Perhaps our greatest asset is the archipelago of the Andamans and Nicobar group standing like a fortress at the mouth of the choke point of the Malacca Straits, enabling surveillance and interdiction in an all-out conflict.

However, increased Chinese naval presence in Hambantota port on our southern extreme, at Djibouti and perhaps in Myanmar, means the Indian Ocean is not as we tend to believe. Last year while speaking at the United Nations Security Council’s high-level debate on maritime security, Prime Minister Modi very aptly described India’s challenges in this domain. “Oceans are our shared heritage, and our maritime routes are the lifelines of international trade.

16 UNDERSTANDING THE MARITIME DOMAIN

RESEARCH TEAM

SYNERGIA FOUNDATION

LESSONS FROM UKRAINE

The war in Ukraine has been a test bed for many new weapon systems and concepts.

Maj. Gen. Moni Chandi is the CSO at Synergia Foundation & a former In spector General of the elite National Security Guard.

It is quite challenging to understand the ‘Future of Warfare‘ because while factors like Interna tional Relations, Geopolitics, and Geo-Econom ics build the environment for conflict, the actual prosecution of the war is dictated by National Se curity, Technology, and the Art of War. The Ukraine war has made this exercise much easier as many in sights are available from the conflict zone..

At the war’s commencement, Ukraine and Russia had a similar inventory of Soviet-era weapons. However, as the war progressed, 31 nations of the Western Alliance, led by the The U.S. provided a wide range of weapons & equipment to Ukraine. From a technology- demonstration point of view, the Ukraine War provided a live test bed to arms manufac turers. Leading arms manufacturers from the Western Alli ance have used the opportunity to demonstrate & field test a wide range of weapons, equipment, and technologies.

LESSONS AT THE GEOPOLITICAL LEVEL

Nations must be prepared for the entire spectrum of conflict. No nation, however rich, has enough resources to create different kinds of forces to meet all threats; hence be adaptable and versatile in your force structures, equipping and training so that you can best adapt to what the fog of war throws at you ultimately.

into a conventional war by Ukraine, logistically supported by 31 Western nations. The lesson here is while aggressive superpowers may hope for quick, decisive victories, smaller nation-states can bleed them in prolonged conflict, provid ed they can absorb the initial shock & awe and contin ue to receive the backing of their citizens and war material from abroad.

Space for Conventional War under

Nuclear Over hang After the bombing of Hiroshima Nagasaki in 1945, there was abundant caution for nuclear powers engaging in a conventional war that could trigger a nuclear exchange. However, in 1999, during the Kargil operations, India & Pakistan, both nuclear powers, engaged in an intense bor der skirmish. The Kargil War, as we refer to it, demonstrated there was geo-political space below the nuclear threshold for nuclear powers to engage in conventional wars. That les son seems to have come home to roost in Ukraine. Seven months into the conflict, Russia, a superpower, is being bled

Propaganda War. Propaganda is a legitimate tool of war. It is normally used to raise the morale of the home side and lower the morale of adversaries. In the Ukraine War, both Russians & Americans devoted considerable resources to building narratives and influencing public opinion. The U.S. did a much better job than the Russians in the propa ganda war. The way European public opinion was molded to muster support for the economic sanctions against Russia despite the economic pain was impressive. In the Informa tion Age and particularly in democratic societies, it is im portant to build control a public narrative that supports the war effort.

OPERATIONAL AND TACTICAL LESSONS

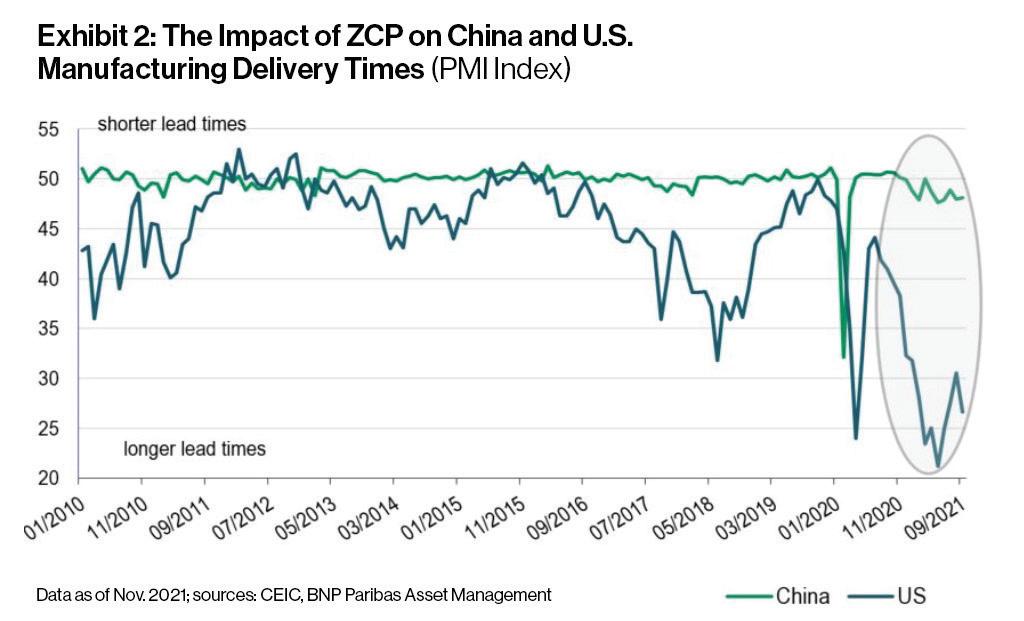

Cyber Warfare. At the war’s commencement, Russia successfully knocked out Ukraine’s internet & communica tions systems. Russia was also able to hack & disable the US

VIASAT, which provided commercial communications to Ukraine. Russia also carried out attacks on govern ment websites utility services (banks & power). How ever, within weeks, with international support, Ukraine was able to restore Internet, communications, and ser vices. More significantly, Space X’s Starlink restored full Internet coverage over the whole country. Internet cov erage in Ukraine, in addition to civil communication, has also been used for military applications.

The lesson here is while offensive cyber operations could be initially successful, cyber systems will NOT only be restored but Internet-based military applica tions for intelligence, surveillance, reconnaissance, and artillery control can also be developed quickly. Drones. If Vietnam is remembered as the first televised war, the Russo-Ukraine war may be remembered as the first war where both adversaries avidly used drones. In 2016, during the annexation of Crimea, Russia used a wide range of drones to support their land invasion (Zala KYB, Eleron-35, Orlan-10, Kronshtadt Orion).

However, in 2022, the Ukrainian Armed Forces contested the Russian invasion with a range of home grown drones to thwart Russian progress. Three drones have performed well: the Turkey-supplied BAYRAKTAR TB-2 medium-range long endurance (MALE), which carries four weapon pods, and Ukraine’s indigenous A-1 SM Furia and Leleka-100 drones, which were used for aerial reconnaissance and artillery fire adjustment.

Loiter or Kamikaze Ammunition. An important variation of drones is Loiter munitions, which fired over a target area to loiter over the space (30-60 min utes), to acquire a target, and then execute the kill by flying into the target. Both Russia and Ukraine used a variety of loitering munitions. While Ukraine had its own indigenously developed munitions (RAM II and

ST- 35 Silent Thunder), they were also beneficiaries of a variety of loitering munitions from other countries, including the U.S. produced, Switchblade (AeroViron ment) and Phoenix Ghost (Aevex Aerospace). Loiter munitions will have a fundamental impact on the future battlefield. Firstly, by attacking the relatively vulnerable top of the vehicle, it questions the the primacy of the tank on the battlefield; secondly, mechanized advanc es, the primary component of offensive-maneuver will now have to find practical means to counter the new threat; and thirdly, loiter munitions will accentuate the non-linear threat of the future battle, by making assets otherwise distant from the front lines like AD weapons sites, logistic hubs, communications centers, and tacti cal HQs, increasingly vulnerable, to precision attacks.

MANPADS in the TBA. MANPADS (Man Porta ble AD Systems) are surface-to-air missiles designed to be carried and fired by a single soldier. STINGER MANPADS (produced by Raytheon, US) was used with effect by the Mujahideen in Afghanistan and substan tially dented the Soviet control of the airspace. Ukraine has received significant quantities of the more con temporary, US-manufactured FIM-92 STINGER, the Thales-manufactured STARStreak and the South Ko rean-manufactured CHIRON KP-SAM Shinguang. The proliferation of MANPADS in Ukraine severely imped ed Russia’s helicopter operations in the Tactical Battle Area (TBA) as well as close air support operations by fixed-wing aircraft at altitudes below 4.5 Km.

Long Range Precision Fires. There has been much publicity about the M-142 HIMARS (Lockheed Martin) rocket-missile system, with a range of 80-300 Km. The qualitative improvement of this weapon system is that it is capable of firing either multiple (6) unguided rock ets over limited ranges (80 Km) or a single guided mis sile over extended ranges (300 Km). With its precision

18 LESSONS FROM UKRAINE

Source : The True Firestarter, Global Times

accuracy and enhanced range, this weapon system is believed to have been used for attacks inside the Crime an Peninsula, namely the Saki Air Base, the ammunition facility at Mayskoye and Kersh Bridge. Long-range pre cision fires further accentuate the non-linear nature of future battlefields. The tactical battle area in Ukraine extends 300 Km from the front lines, and all assets in the TBA are fair game.

SHOULD INDIA BE WORRIED?

India has always maintained that even when both adversaries are nuclear-armed, there is scope for the conduct of conventional war. This has been practised by both India and Pakistan in some form or other since the Kargil war of 1999. However, both sides have taken special measures to calibrate the escalatory ladder so as not to cross red lines.

This underscores the efforts of the Indian military to maintain a significant conventional deterrent for a two-front conflict, despite the high cost involved. How ever, the level of conventional weaponry needs to be constantly upgraded to match global standards, prefer ably through indigenous efforts.

Offensive cyber capacities are attractive, but their effects may only be transitory in a full-scale war. Also, with the advent of small & microsatellites, In ternet capacities can be rebuilt even enhanced within days. Both these aspects need to be attended to urgent ly in the Indian context.

Drones are a game-changer in a conventional war. Loiter munitions will challenge 3rd Generation war fare, which advocates manoeuvring on the battlefield with mechanised forces. The Indian military is invest ing in upgrading its drone capability, including swarms and kamikaze drones, with the help of the private sec tor, especially startups. However, a great deal of ground has to be covered as the Indian armed forces have very little experience in the combat employment of drones in significant numbers offensively, whether conven tionally or in counter-terror opera tions.

The proliferation of MANPADS, which re quire low-level skills (and can be fired by a civilian), has trans formed the airspace over the TBA. Helicop ter operations and Close Air Support below 4.5 Km altitude need to be reworked the new hostile environment. the most modern air forces have answer to this threat except re sorting to stand-off attacks using precision ammunition. Indian military aviation is fully sensitive to this threat and would be evolving suit able tactics to combat them.

Precision long-range fires delivered by guided mis siles will be a strong characteristic of future warfare. AGNI, PRITHVI, and BRAHMOS are commendable indigenous efforts, but more improvements are needed for adequate quantities and targeting qualities. Longrange fires are effective only if married to a sophisti cated satellite-supported Intelligence Surveillance and Reconnaissance (ISR) system. We need to develop cy ber capacities to creatively manipulate public opinion of domestic, international and target audiences so that our national interests receive the appreciation they de serve.

INDIA’S ATMANIRBHAR (SELF-RELIANT) FO CUS

India India has been placing great importance on developing indigenous capability in the Defence Sector. However, given lessons drawn from Ukraine, certain fo cus areas must be prioritised for the Atmanirbhar drive.

Counter-Drone Warfare. While drones contin ued to hold sway in the Ukrainian Battlefield, what was missing, was a viable counter to them. It does not make sense to use a high-cost surface-to-air missile, say the S-400 missile (costing millions of dollars), to neu tralise a comparatively low-cost drone threat. Indian Armed forces need a reliable (accurate) shoulder-fired ‘drone-killer’ that can shoot down drones at ranges of up to 4 Km. Even better, a man-portable jammer, that can jam the drones’ command telemetry would be ideal.

Space-based SATA. SATA is a military acronym for Surveillance and Target Acquisition. The architecture of future defensive systems should be based on three parameters. Firstly, real- time monitoring threats to our land & maritime borders from space. Secondly, tar get analysis allocation of weapon systems is done from a secure location, well-removed from the battlefield. And thirdly, the target is engaged with a precision-guid ed munition at stand-off distances from the battlefield.

Counter to MANPADS. Unless we find a counter to MANPADS, the primacy of the tank on the battlefield the ability of mechanized for mations to lead advanced operations will stand undermined. Even artillery assets de ployed in the depth areas will remain highly exposed to drone attacks. Long Range Precision Fires. Long-range precision fires are key to the future of warfare. This is called the stand-off battle in military parlance, and precision fires from some weapon systems have reached precedented ranges.

19 LESSONS FROM UKRAINE

EXPERT VIEW

LT. GEN. ASIT MISTRY PVSM, AVSM, SM, VSM (Retd) is that Director of School of Internal Security, Defence and Strategic Studies at the Rashtriya Raksha University.

DEBUNKING SOME MYTHS

We are still too close to the war in Ukraine to arrive at conclusive deductions about weapon systems and doctrines. TV imagery flashed on our home screens can be delusionary and make us draw lessons without au thenticated objective data or unbiased analysis. To see tanks being blown up by precision strikes and deduce that the armoured fighting vehicle era is gone is perhaps a bit premature.

All military technology has an evolutionary cycle, which stands true for the tank. Right from the first world war, where the tanks first came onto the battle field, there is a continuous competition between tanks and anti-tank. And when a particular technology to de feat the protection levels in the armour is found, tank protection is upgraded, mobility is enhanced, and thus, survival levels go up.

Going back to the 1973 Yom Kippur war, anti-tank guided missiles made their maiden appearance on the battlefield producing a devastating effect when used in swarms. Back then, the end of the tank had been pre dicted, but that didn’t happen.

Tank designers came up with compound armour, and the modern tank endured. When the side and the frontal armour became too strong, anti-tank munitions were designed for a top-attack profile. It can be assumed that some years down the line, tanks will adapt to the new battle environment. Work is already on hand.

The same theory can be applied to drones (now so much in the news as the ultimate weapon) and their counters. This cyclic process of the law, a new technol ogy emerging and creating a disproportionate effect till something counter to it is discovered or invented, is a continuous process. So, while drones today may swarm targets in numbers too large to be neutralised or utilised in different configurations, from the ISR versions to command drones and the kamikazes, their counters will soon make appearances on the battlefields. These will not be million-dollar missiles but something far more affordable, matching the drones dollar to dollar.

This kind of race is a continuous evolution in war fare. Therefore, it would be premature to assume the extinction of a particular type of weapon system that has withstood the test of time and the rigours of the battlefield.

Information Warfare is another segment that merits closer attention, especially in the context of the Ukraine war, where there are two very stark examples. One side

is trying to dominate the information space with a mas sive bombardment of information through social me dia, Internet TV etc. The other side, in contrast, is hard ly saying anything domestically or externally. Ukraine has certainly managed to sustain its national morale through its information warfare efforts and ensured that western support does not falter.

However, the West had predicted that an increasing number of body bags arriving in Russia would sap the national morale; the ground-level support for the ‘spe cial military operation’ shows no sign of lagging after almost eight long months despite the sheer absence of a propaganda blitz by the Kremlin.

It almost appears that Mr Putin pays little impor tance to such modern gimmicks, despite being bom barded by slickly produced visual productions predict ing the demise of the Russian army in the morass of Ukraine. So, what is the lesson that policymakers draw from these two examples?

Undoubtedly, there are some clear lessons. To sup port your propaganda war, you need to have a narrative, but you must also create something on the ground so that the narrative is credible. All sides, including the larger world, have means to get transparency, and fake news can be unmasked.

Dedicated portals make a living doing fact checks and can effectively separate the chaff from the wheat. Furthermore, the narrative must have an objective pur pose to influence the behaviour or shape the percep tion, both internally and externally. In open democratic societies, blocking information is difficult, but this flood of information itself sometimes becomes a problem.

Therefore, the lesson is to build a credible narra tive that is not built on silos but can relate to the actual ground situation.High-tech precision strikes and longrange weapons with immense destructive power have a place on the battlefield (and are most popular on You Tube).

Still, they cannot substitute for the physical clos ing in, and the ultimate capture of the objective done in a manner that has not changed for centuries. The Ukrainian counter-offensive shows that an army that cannot hold on to captured ground despite all its mod ern arsenal is hardly worth its salt.

We are still in the midst of the conflict in Ukraine, and it may be too premature to decide conclusively on the effectiveness, or otherwise, of certain weapons sys tems and warfighting principles. Ukraine may not nec essarily be a template that can be applied globally to all conflicts.The conclusion could be to be prepared for the entire spectrum of conflict.

No nation, however rich, has enough resources to create different kinds of forces to meet all threats; hence be adaptable and versatile in your force struc tures, equipping and training so that you can best adapt to what the fog of war throws at you ultimately.

20 LESSONS FROM UKRAINE

OUTER SPACE AS A KEY CONFLICT DOMAIN

Space networks are vital for a nation’s economic growth and military potential.

Air Marshal Rajiv Dayal Mathur, PVSM, AVSM, VSM, ADC is a former officer in the Indian Air Force. He was the Air Officer Commanding-in-Chief (AOC-in-C), Eastern Air Command from 1 March 2019 to 30 September 2020.

Space, not surprisingly, is highly congested, with over 6,400 satellites in orbit. They’re almost 50,000 pieces of space debris of measurable size, i.e., ten cm plus. Space has become a part of our lives-GPS, weather bulletins, DTH TV and now satellite broadband being provided by market leader Starlink even in war-torn Ukraine. At present more than 80 countries have space launch programmes.

TRANSFORMATIONS IN SPACE

Communication satellites have evolved over the last decade. Earlier, they used to be primarily in geostationary earth orbit but now have been moved to low earth orbit because of the lower latency and better revisit frequency. Many positioning constellations beside the GPS are being deployed in space.

While the majority are operated by the U.S, Russia, Chi na, the European Space Agency, Japan and India have also joined the club. The private sector has emerged as a major player, especially since 2009. SpaceEx is already a household brand and global private investment in space exceeds USD 25 million.

Miniaturisation of electronics gave birth to cuboid satel lites which have revolutionised satellite-based communica

Greater transparency in orbital activities would lead to more equitable utilisation of resources and fewer chances of a conflict.

tions. These are cheap to manufacture and launch and being power efficient, last longer in orbit. Space X is developing reusable launch vehicles which will further bring down cost per launch. Space tourism is growing despite the astronom ical costs.

It’s expected that the space industry could become a trillion-dollar industry in the next two decades. There have been technological improvements as well, which have im proved satellite communications. Satellite applications will become more secure because LASER technology enables higher data rates. Also, remote sensing solutions are im proving daily for electro-optical and synthetic aperture ra dar. Today, it’s commonplace to see 40 cm resolution; soon it could come down to 10 cm.

CONFLICT POINTS IN SPACE

Satellite servicing vehicles are a concept already under consideration by the European Space Association, which would be used to refurbish, replenish, refuel and move sat ellites that have come down into a lower orbit and re-boost them into higher orbits. Counterpoint Transportation over the surface of the Earth over large distances is a concept that SpaceX is looking at.

Space mining of asteroids and the Moon for rare earth metals, as well as iron, nickel and cobalt, is being planned. This, too, would create possible friction points for future conflicts of interest.Active debris removal missions are al

ready in the pipeline. Of course, this was being done by the space shuttle earlier but at a much smaller scale. Now the intent is the removal of excess debris in scale, through autonomous robotic removal in the lower or bits.

Space has always been considered the ultimate high ground and has been militarily active but perhaps more covertly. Space military activities now include proximity operations with space-based lasers as anti-ballistic mis sile weapons or against surface weapons/ targets. There are also military programmes that include kinetic an ti-satellite weapons.