SHIFTING SANDS IN ASIA

ENABLED FEBRUARY EDITION 2024 | MONTHLY EDITION LOOKING BEYOND THE CURVE SYNERGIA “ASIA 2035: TOWARDS AN ASIAN EPOCH?” Page - 03 INDO-PACIFIC CHALLENGES Page - 17 TRUSTWORTHY AI Page - 28 STIRRING UP OF BLOOD TIES! Page - 35 Page - 48 BUDGETING FOR GROWTH EXCLUSIVES

MEDIA

INSIGHTS is a strategic affairs, foreign policy, science and technology magazine that provides nonpartisan analysis of contemporary issues based on real-time information.

To subscribe,

sambratha@synergiagroup.in ; +91 80 4197 1000

https://www.synergiafoundation.org

EDITORIAL

Dear Reader:

Greetings from the Synergia Foundation!

The Spotlight story of this month analyses the facts and fiction of the ‘Asian Century.’ Any discussion on this subject will invariably lead to comparing the Chinese model with India’s growth story. We have selected a galaxy of neutral analysts to get an objective view and put the subject in the correct perspective.

In our regular coverage of India’s neighbourhood, we have graduated from the immediate neighbourhood to the extended one since the last few issues. This time, we lead with the Indian viewpoint on the naval dimensions of the Indo-Pacific as articulated by the Chief of Naval Staff of the Indian Navy. We also look at the growing Indo-Japanese partnership, as seen by the Synergia Foundation during a recent Quad interaction hosted by Japan.

As always, technology remains a core subject for Synergia Foundation and finds a reflection in all our activities and publications. This issue is no exception, and we seek the views of practitioners of

security (defence, economic, cyber, etc) to pen down their insights on their respective fields of expertise. We look at the new domains of warfare generated by technology and do a detailed vivisection of artificial intelligence in all its dimensions: legal, warfare, etc.

In our global scan, we look at global strategic trends. In this segment, we are starting a new series focusing on Africa. We start with what it means for India to reach out to the African continent at large, and with South Africa being one of the most significant nations of the region, the Republic of South Africa is the focus.

This month’s geopolitics basket has an overview of the recently concluded elections in Taiwan and a detailed insight into the Red Sea embroglio. We end with an analysis of the recent interim Indian budget.

We hope our esteemed readers will continue supporting us as we strive to further evidence-based research on strategic issues with global resonance.

Sincerely yours

Maj. Gen. Ajay Sah Chief Information Officer

Maj. Gen. Ajay Sah Chief Information Officer

SCAN THE QR CODE TO SUBSCRIBE

SCAN FOR FEEDBACK

SCAN THE QR CODE TO SUBSCRIBE

SCAN FOR FEEDBACK

FEATURED

“ASIA 2035: TOWARDS AN ASIAN EPOCH?”

Markets and technology will play a critical role in this region, largely because of the great population centres that exist here.

PAGE 03

ASIA’S RISE TO GLOBAL DOMINANCE

An Asian century, which is still a way off, will require the cooperation of both China and India.

PAGE 06

ASIA UNLEASHED: THE POWER PLAY BEGINS

For China to define the Asian century, domination over Asia is essential.

PAGE 08

2035: PEERING INTO INDIA’S ECONOMIC FUTURE

Given the tumultuous geopolitical landscape, what does 2035 hold for the Indian economy?

INDIA’S EXTENDED NEIGHBOURHOOD

PAGE 12

INDO-PACIFIC CHALLENGES

Indo-Pacific is a natural region where the destinies of constituent nations are deeply interlinked.

SUSHI AND SPICES: DECODING THE INDO-JAPAN ALLIANCE

The India-Japan partnership extends beyond bilateral ties, finding expression in trilateral arrangements and the Quad framework.

PAGE 17

PAGE 21

SECURITY

NEW LAND OPERATIONS

Future conflicts will probably be more complex, more lethal and more contested.

PAGE 23

WARFARE AHEAD: CONFRONTING FUTURE CHALLENGES

PAGE 24

TECHNOLOGY

ALGORITHMIC WARFARE: AI’S PROMISE & BOUNDARIES

As far as risk mitigation is concerned, there is no one-size-fits-all solution.

PAGE 26

TRUSTWORTHY AI

As far as risk mitigation is concerned, there is no one-size-fits-all solution.

PAGE 28

AI AND THE LAW: WHERE PATHS COLLIDE

New technologies, however impressive, will never eliminate the fog, friction, and chaos of war.

GLOBAL SCAN

GLOBAL TRENDS: TRANSFORMING TOMORROW

“For the first time, we are looking at the potential for global conflict on a scale of World War II.”

PAGE 33

STIRRING UP OF BLOOD TIES!

PAGE 29

The Indian diaspora in South Africa is undeniable, but do they have the bandwidth to act as a bridge with their mother country?

PAGE 35

GEOPOLITICS

TAIWAN ELECTIONS: TAKING A COUNT

An emboldened Lai Ching-te asserts Taiwanese sovereignty but remains short of claiming a formal declaration of independence.

PAGE 42

ECONOMICS

BUDGETING FOR GROWTH

India’s interim budget has laid out the roadmap for growth by signalling an investment boost, tax relief and key measures for focus groups.

REACHING OUT TO AFRICA

India needs to frame its African strategy through an Indian lens.

PAGE 39

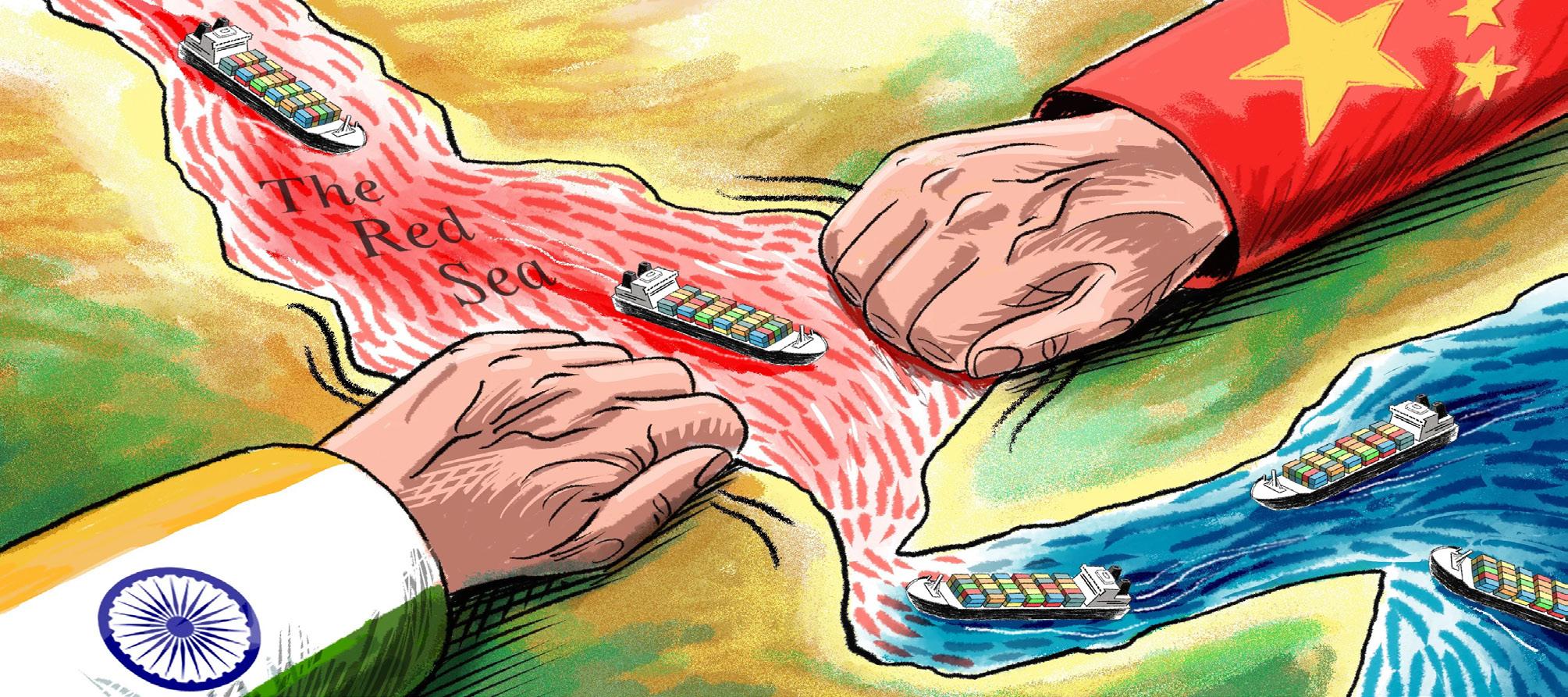

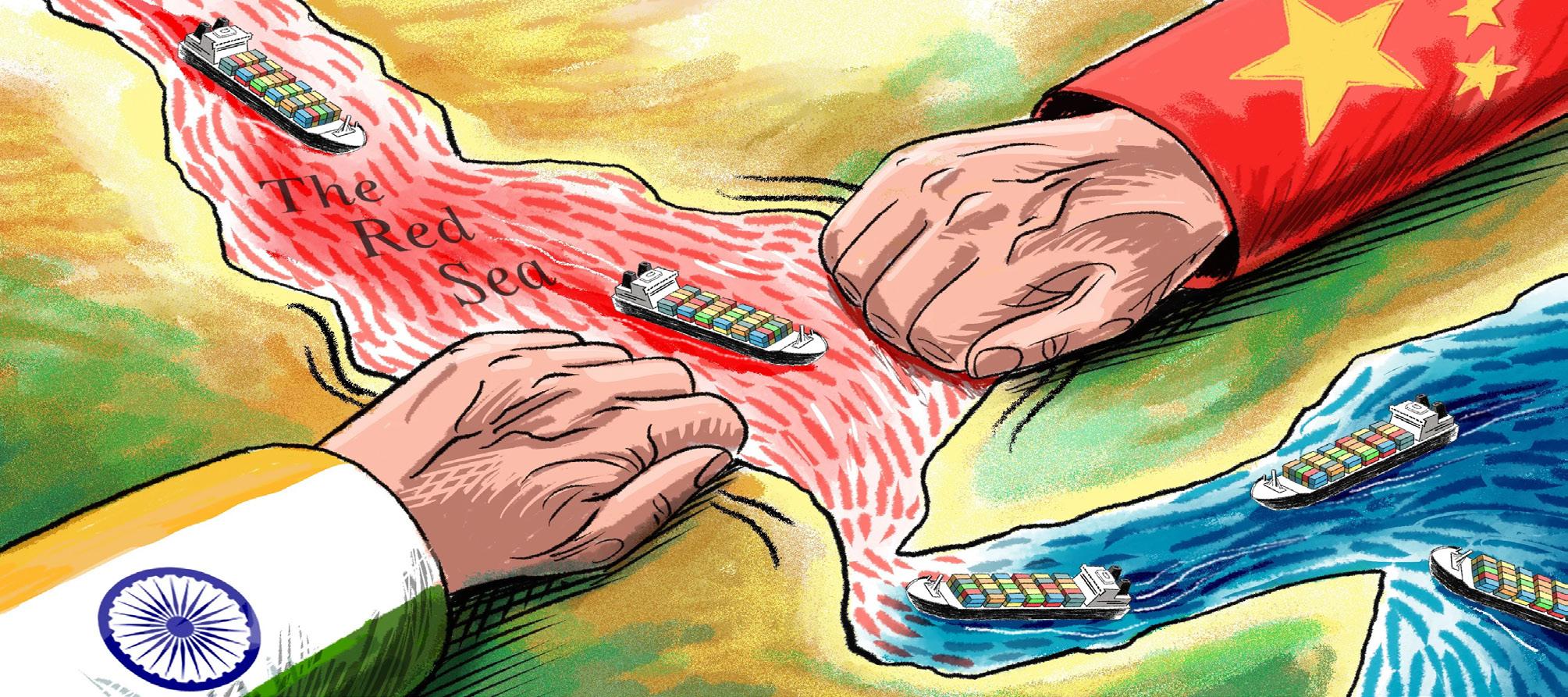

TURNING RED

The Red Sea has become an arena of conflict between David and Goliath with international repercussions.

PAGE 45

HEALTH CARE

QUAD: TRANSFORMING GLOBAL HEALTH

PAGE 51

Future conflicts will probably be more complex, more lethal and more contested.

` SPOTLIGHT STORY : MAPPING TRAJECTORY OF ASIA 2035

The multifaceted dimensions of Quad are highlighted by its efforts to transform global health by overcoming paradoxes and embracing innovations.

“ASIA 2035: TOWARDS AN ASIAN EPOCH?”

Markets and technology will play a critical role in this region, largely because of the great population centres that exist here.

It is fashionable to call this the ‘Asian Century.’ But amidst all the optimism lie embedded niggling doubts.

In light of the recent transformational events that have taken place, does the concept of the Asian Century still hold true? Is economic heft sufficient for Asia to claim the Century? And more importantly, what are the key drivers or factors that will impact the trajectory of Asia over the next 10 to 15 years? And finally, what are the plausible scenarios that could emerge for Asia by 2035?

2035 is not very far away by historical standards; it is just 13 years away from now. Because in the last ten years, India’s GDP has doubled, a 10–12-year period is not a particularly long period.

UNIPOLAR ASIA?

The base case scenario for the Asian Century is an Asia that China dominates. Any other scenario would be an aberration and somewhat of a Black Swan event. Despite the difficulties that the Chinese economy faces, almost all predictions about China’s growth and GDP are pretty uniform, putting China at a GDP of about $50

The rise of India will be a major factor in how China and India handle each other and live with each other in such an Asian Century. China and India face challenges, but how much of this will lead to unipolar or multipolar Asia is also a question that seeks answers.

trillion by 2035, the United States at $36 trillion, and India at about $10 trillion.

The question then becomes whether we are talking of an Asian or Chinese century. What might unfold is that possibly, for the first time, a global power that is resident in Asia and not in Europe or North America. And this will have major implications for the security architecture of the entire region.

Will China be an interventionist power like the United States or the erstwhile Soviet Union, or will it take a different shape and form regarding global institutions? The BRI and successor programmes indicate an alternative approach, both to the consolidation of power within and consolidation of power without.

The second question that arises is whether Asia is amenable to a security architecture in the form that we have seen in Europe and in the transatlantic alliance or earlier during the Soviet times of the Warsaw Pact. The prognosis for an Asia security architecture is still highly bleak.

SYNERGIA CONCLAVE 2023

This

article is based

on the round table curated

by

Ambassador Pankaj Saran, Member (NSAB) & Former Deputy National Security Advisor India, on the Trajectory of Asia 2035 at the 9th Synergia Conclave 2023.

There are serious identity issues. While the focus may be on East Asia, the fact is that multiple Asias impact the security architecture- West Asia, Central Asia and South Asia. And the question is whether with a China-dominated Asia, what will be its influence over the non-East Asian parts of Asia.

Will there be a convergence of security perspectives within Asia, or will we continue to see fragmentation as evident in West Asia?

The rise of India will be a major factor in how China and India handle each other and live with each other in such an Asian Century. China and India face challenges, but how much of this will lead to unipolar or multipolar Asia is also a question that seeks answers.

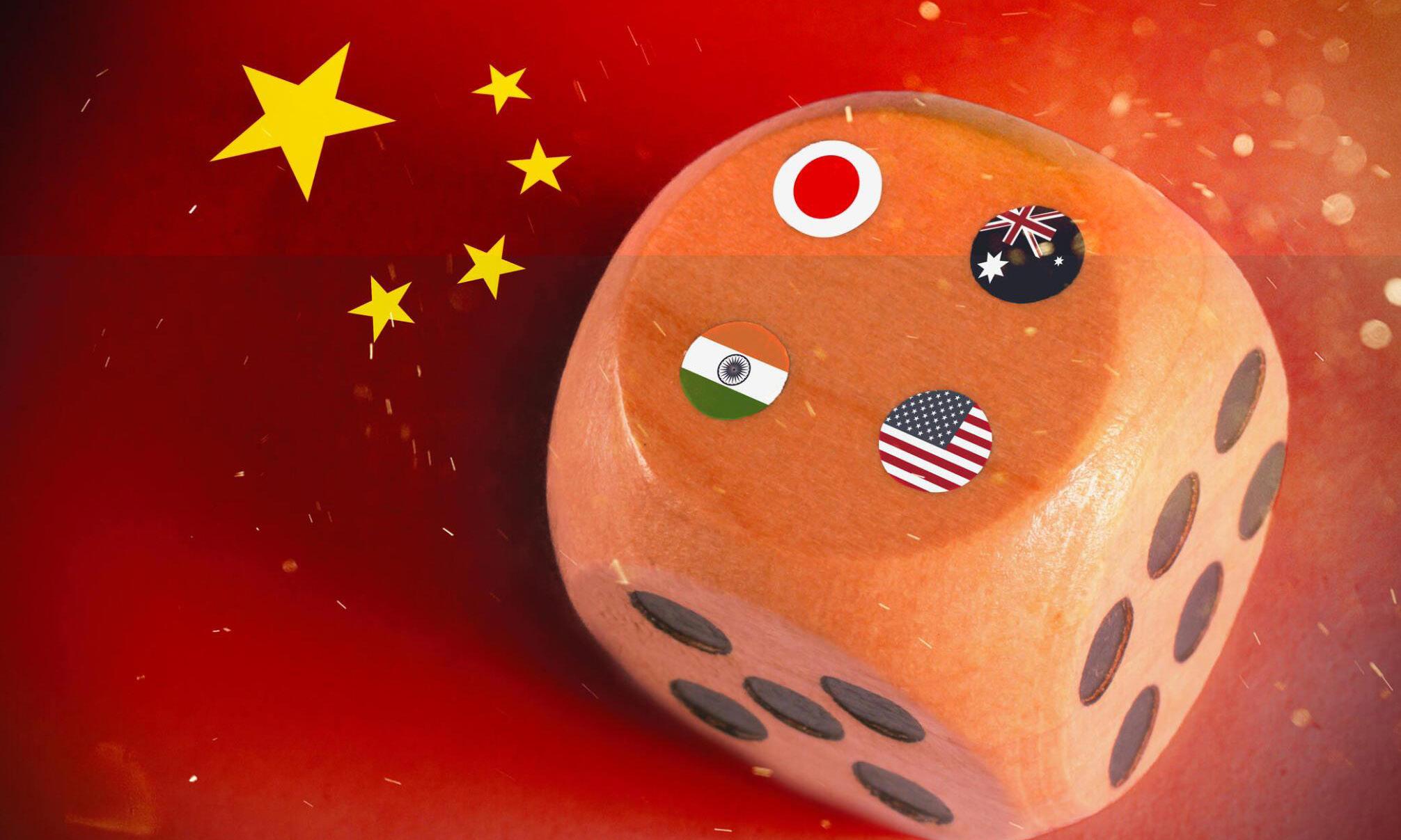

If we go by the base case scenario of an Asia dominated by China, we are heading towards a unipolar Asia. If that is the case, what would be the responses from the residential powers and powers outside Asia?

U.S. CHINA CONTESTATION

The world has witnessed different phases of the U.S.-China rivalry. However, as time passes, we will see more and more peer relationships between the two powers. In 2017, the United States national security strategy referred to China for the first time, and in the last six years, the U.S. national security approach to China has been informed by this new paradigm of major power relationships.

As a consequence of this big power rivalry, a certain degree of hedging and uncertainty will exist among the middle powers of Asia. Here the role of India could become critical in terms of offering choices to other Asian countries in values, systems, institutions, etc.

Markets and technology will play a critical role in this region, largely because of the great population centres that exist here. India will be a huge market by 2035. The question is whether production can be democratised and manufacturing centres created outside China.

Technology will be a critical driver of influence; a technological race is underway, which will impact Asia as it will impact the rest of the world.

If China is the dominant major global power, then the lines between Asia and Europe or Asia and other continents will likely blur. So, can other Asian countries claim a stake in the so-called Asian Century? If yes, then what is the space that they will occupy?

While the region has many fault lines, Taiwan could be critical. There is unlikely to be any conflagration over Taiwan till 2035 because all parties understand that any breakout of kinetic war in the region will be extremely disruptive and detrimental to China and other parties who might be forced into such a conflict.

AN ASIAN UNION?

Can Asian countries overcome all their differences and form an Asian union? The fact is that Asia remains as fragmented as it was many decades ago. There is a lack of Asian identity that will bring different sub-regions of Asia together to form some kind of a project or an organisation, as we have seen in Europe.

Paradoxically, the only initiative that seems to link Asia’s sub-regions is the Chinese BRI. There have been some studies on creating an Asian Monetary Fund, again a localised East Asian project spearheaded by the ASEAN. It does not command much consensus within the Asian region.

04 “ASIA 2035: TOWARDS AN ASIAN EPOCH?”

PROF KUNIHIKO MIYAKE Former advisor to the Prime Minister of Japan, special advisor to the Japanese Cabinet.

PROF KUNIHIKO MIYAKE Former advisor to the Prime Minister of Japan, special advisor to the Japanese Cabinet.

ASIA 2035

SCENARIOS FOR THE ASIAN CENTURY

When analysing the trajectory or power cascade for 2035, the key driver would be the U.S.-China relationship. The issues to be addressed in this context are the possibility of a US-China war and its winner or loser and the contributions India can make.

POSSIBLE SCENARIOS

If it is assumed that there will be no war before 2035, no winner and no loser, and a free and open Indo-Pacific will continue, then we are looking at the status quo. Does it mean then that there will be no century of Asia? Most would prefer this status quo.

But suppose war breaks out. Then there are three possibilities. Scenario ‘A’ means Americans will win, Scenario ‘B’ means China will win and Scenario ‘C’ means somewhere in between.

Scenario A: If America wins and China is badly defeated, China will not be left unimpacted- something has to give in either direction. Will they move towards democracy or become even more dictatorial?

Scenario B: There are two possibilities. If China wins, Americans may leave the world stage. And that would create a huge vacuum that China may dominate. Here comes India’s contribution that could make a difference.

Scenario C: While America wins, the victory could be a pyrrhic one, leaving a deeply weakened America in its wake. This could leave East Asia extremely unstable.

There would be greater demand for an Indian contribution to stabilise the situation. Only fools learn from experience; the wise learn from history. In the 1930s, in East Asia and the Indo-Pacific region, there was a new rising power- powerful, nationalistic and very xenophobic-Imperial Japan. Perceiving America as a declining power, it sought to establish a new international order

of its own making. This rising power challenged American hegemony militarily in the Western Pacific; the rest is history. The greatest worry is that China should not walk into the same trap as Imperial Japan did in 1941 by attacking Pearl Harbour to challenge the status quo by force.

The Chinese assure us that they are not that stupid.

ECONOMY VERSUS SECURITY

The economy underscores security, but mistakes are made when there is a big gap between the thinking of the strategic thinkers and the economists. The economy is not a driver; the economy is the result because, without any stable national security situation, there will be no economic activity. To have security, sometimes we need an economy, but the economy results from perfect security arrangements.

For successful security arrangements, geopolitical dominance is a pre-requisite, but technology is needed to do that. So, disruptive technologies are extremely important. However, technology does not guarantee geopolitical dominance.

Japan is a good example, a highly sophisticated, advanced country of technology in the 60s and 70s, especially the 80s and 90s. Did it become a dominant geopolitical power? No. State-of-the-art technology should be applied to the battlefield. But if they are not applied to the battlefield, a real weapon system, you can never be a dominant power. Japan has never tried to do that because it is a peaceful nation. Its engineers or inventors have no idea how to apply those state-of-the-art technologies to military applications.

Israel is a different example; it talks about technological innovations day and night and their application to the weapon systems they use every day. Technology comes first to be a dominant power, but to do that, you should be able to apply those disruptive technologies to the battlefield. Then, you stabilise the situation to reach a comfortable level of security, which enables economic prosperity.

SYNERGIA CONCLAVE 2023

ASIA’S RISE TO GLOBAL DOMINANCE

An Asian century, which is still a way off, will require the cooperation of both China and India.

As per the database sampled by the late Angus Pedersen, a very distinguished economic historian, based on purchasing power parity internationally, in 1820, two centuries ago, China supposedly had accounted for more than 30 per cent of world GDP, and India accounted for perhaps between 20 and 25 per cent of global GDP. The U.S., being a new country then, had less than 3 per cent.

What has happened over the years is that by 1960, the U.S. accounted for over 30 per cent. And in the meantime, both China and India have declined. Around the 1960s or 1970s, both were at the bottom, fetching much less than 10 per cent. However, there has been a turnaround; by 2015, China, in purchasing power parity terms, reached parity with the U.S. This finding was confirmed by both the IMF and the World Bank. India also came up, but not by as much.

CHINA AND INDIA

It would take until 2033 before Chinese GDP, and market prices and market exchange rates catch up to the U.S., even though China has been growing faster than the U.S. for about half a century. India has also been doing well in terms of GDP growth, especially in the last decade or so. Indian growth rates in the last ten years have sometimes been even higher than Chinese growth rates, and

East Asia is higher than the USA now. In 2070, China and India would have a GDP of perhaps half of the world’s GDP. India has very fine economic fundamentalsno shortage of primary inputs, tangible capital, labour and human capital. The Indian savings rate is quite healthy, around 30 per cent. India has enough savings with finances and investments.

it is assumed that India will continue to grow at 8.5 per cent. But even at these rates, it will not come too close to the Chinese or U.S. GDP.

In terms of per capita, the gap is big even for China. Even when China reached parity with U.S. GDP, for per capita, China was only one quarter that of US GDP, and it would take at least until the end of this century, if at all, for Chinese GDP per capita to surpass that of U.S. GDP. India, there’s a similar story, just a little bit further displaced in terms of time. India will become a huge economy probably sometime around 2060, maybe 2070.

While the U.S. share of the global GDP has been steadily declining even though it is about 50 per cent today, the Chinese has been going up along with India. Japan peaked at about 18 per cent of the global GDP in the early 1990s and has since been coming down. India is rising, although not enough to make a difference right now. East Asia is higher than the USA now. In 2070, China and India would have a GDP of perhaps half of

SYNERGIA CONCLAVE 2023

This article is based on the round table curated by Prof Lawrence Lau on Trajectory of Asia 2035 at the 9th Synergia Conclave 2023.

WHEN THE WORLD’S ‘BACK OFFICE’ MEETS WITH THE WORLD’S ‘FACTORY’ ...

the world’s GDP. India has very fine economic fundamentals- no shortage of primary inputs, tangible capital, labour and human capital. The Indian savings rate is quite healthy, around 30 per cent. India has enough savings with finances and investments.

INDIA

Labour supply in India should not be a problem. India is now the world’s largest population and has a younger population than China. It has a highly educated labour force and an ample supply of engineers and scientists. And like China, India enjoys tremendous economies of scale.

And because of its large population, it has a very large number of very smart people. India needs to construct an infrastructure to link the whole country together to realize its economies of scale. It should, therefore, invest in developing leading infrastructure that will create its own demand.

India should also have a strong export promotion strategy. As India expands its manufacturing, it will create employment and boost trade. India does not have a single unified language, but it can rely on English for communication. Corruption per se should not be an obstacle in itself. As you read about it in papers, corrupt senior officials are uncovered in China almost every day. So, even when people complain about possible corruption in India, that alone should not be an obstacle to growth.

SOUTH ASIA

A South Asian Free Trade Zone can be very positive for India and South Asia. Taking India, Pakistan, Bhutan, Sri Lanka, Nepal, and Bangladesh together would amount to a population of around 1.9 billion, a quarter

of the world population. And if SAFTA is created, a mini form of economic globalisation will benefit every member of the world. SAFTA will be able to do the same for South Asia as the European common market did for post-World War 2 Western Europe. That is, maintain peace and prosper together. For instance, Germany fought three wars in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. The common market provided the bond that tied them together; economic interdependence is a great way to prevent conflict between nations.

GEOPOLITICAL FACTORS

Peace in South Asia is positive; lack of peace is negative. Peace in Taiwan’s straits is positive; the lack of it is negative. China-U.S. strategic competition is negative, and it continues. Despite what Graham Addison said, there will not be any war between China and the U.S. because there will not be any winners. Both countries will be losers. The former Soviet Union and the U.S. came to the same realisation and never went to war in the last century. They even had strategic arms control treaties. The same would eventually happen between China and the U.S.

The Bretton Woods system of settlement of international transactions in each country’s national currencies will be revived.

Globalisation, decoupling, and de-risking will all be initially difficult, but ultimately possible because of increased competition among the sup ply chain; competition will lower prices for all. There will be an Asian century, which is still a way off and will require the cooperation of both China and India.

PROF LAWRENCE LAU

Professor of Economic, University of Hong Kong

07 ASIA’S RISE TO GLOBAL DOMINANCE

ASIA UNLEASHED: THE POWER PLAY BEGINS

For China to define the Asian century, domination over Asia is essential.

This article is based on the round table curated by Ambassador Ranjan Mathai, Former Foreign Secretary of India, on Asia 2035 at the 9th Synergia Conclave 2023.

Historically, there is little evidence of Asians having a geopolitical concept of Asia, such as Europe and America, for their continental regions. East Asia, Southeast Asia, South Asia, Central Asia, and West Asia were different geopolitical theatres, sometimes overlapping. Sometimes, there were conquests between one and the other, but there was never one single overarching connection. Henry Kissinger, in his book on World Order, even claims that until the arrival of modern Western powers, no Asian language had a word for Asia.

The popular use of the term Asian Century is recent and speaks of China vs Asia even though many other parts of Asia have risen rapidly in the World Economic Order for decades - Japan, Korea, and Southeast Asia.

CONSTITUENTS OF GREAT POWER

In the 1970s, the Shah of Iran envisaged his country emerging as the fifth economic power in the world in the next two decades. We know what happened to that. World-beating economic growth is not enough to become the driver of a century. This comes with the potential to alter power distribution worldwide, as we saw in Europe in the 19th or the U.S. in the 20th century. It involves comprehensive national power, military technology industry, global diplomatic leadership, global trading and preponderance in soft power, and a leading

Historically, China never had domination except for East and parts of Southeast Asia. Apart from that, Japan, Korea, India, Iran, as well as Vietnam, Philippines, Indonesia, etc., will not go along with a Chinese-dominated order. The U.S. is also not standing still and is determined to retain global preponderance in Asia.

role in the institutional structures of world order and rule-making. All of this rests on one key foundation: the economy. The phenomenal growth of China from the 1990s and joined on a lesser scale from India in the 2000s made the expression Asian Century a projection that entered the popular lexicon by around 2010.

China’s role in reviving world growth after the 2008 financial crisis in the West, its technological and military strength, and the thrust of its Belt and Road Initiative have now made the talk of an Asian century essentially one of a Chinese century with other actors playing lesser roles.

THE CAVEATS

We in India have different ideas. There are too many unknowns, including some known unknowns, some which will come along, and some unknown unknowns. The biggest known unknown is the direction of internal politics within some of the major actors because of the extent of polarisation among all the Asian countries, the United States, and Europe.

SYNERGIA CONCLAVE 2023

To identify the key actors in Asia, the ADB did a 2011 study realizing the Asian century 2050, and they listed seven- China, Japan, Korea, RoK, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, and Thailand. Iran, Saudi Arabia, and Turkey could also be added to this list. Now, Vietnam and the Philippines, or maybe ASEAN as a whole. Russia, Australia, and the US will be key actors in the Asian trajectory. Russia, Australia, and France, for that matter, are physically present in Asia, and the U.S. is getting entrenched in the island chains of the Asia-Pacific.

Asia continues to be one of the world’s fastest-growing regions, and the IMF describes the region as a key driver, generating over 66 per cent of global growth at around 4.6 per cent per annum. The post-pandemic recovery has been generally impressive, though some questions have recently arisen about statistical data on growth rates, particularly the growth rates from China.

CHINA

Since about 2015, through the pandemic and after, it appeared that China’s rise to glob al supremacy was just a matter of time. Since 2022, Chinese growth has slowed. It now seems stuck in a property-related slump. The high U.S. interest rates are weakening its currency, but at the same time, the trade and tariff problems it is encountering have not increased, but they have slashed its usual trade surpluses. The People’s Bank of China has tools to stop the currency slide, but raising interest rates to match the Fed would exacerbate problems in the housing sector as well as its debt repayment.

Has the Belt and Road Initiative achieved by 2023 what it set out to do? That is the transformation of both land-based and sea-based routes. It seemed to be geoeconomically and geopolitically transformative at one stage. China is emerging as the world’s largest creditor for development. Still, recent trends suggest that BRI debt management is done with rollovers rather than repayment as creditors fail to profit from the investments.

China runs surpluses selling consumer, manufactured and infrastructure goods and buying largely commodities and other items that feed back into its own export machine. This leads developing countries to be largely tied to other markets.

Take Sri Lanka for an example, it was being stated how China has overtaken India as the largest exporter to Sri Lanka. But where does Sri Lanka sell? It sells to the E.U., India, and the U.S; China ranks way down. So, when these countries want to make friends to sell, they must return to the West. The most recent US-China Leaders’ Summit suggests that the 2024 elections in the U.S. could be a major factor in determining China’s trajectory till 2035.

There is increasing consensus in the U.S. on treating China as a strategic competitor, but there are differences over the extent to which trade and financial decoupling should proceed. BRI was the first attempt to dominate what the geopoliticians call the world island, Eurasia, as a whole. And that is not going to happen without serious competition.

OTHER MAJOR ASIAN PLAYERS

Exports, infrastructure investment, local government expenditure and state-owned enterprises have powered China’s phenomenal growth till now. All four are facing serious headwinds, and household consumption, which could have compensated remains stuck below 40 per cent of GDP as against 50 to 60 in most other Asian major actors. Despite attempts at stimulus, household debt remains a serious problem.

One known unknown is whether China’s surge in advanced technology despite the U.S. efforts to stall it and green technology will spur a wave of new growth. It is uncertain at this point. The U.K.’s hosting of the first really big conference on artificial intelligence suggests that while there is a lot of technology in China, the West is still trying to lead the rule-making process.

Some recent data suggest that the Yuan is enlarging its role in global trade payments and international finance. It is presently the most active for global payments, but it is only 3.7 per cent of the total in the world, according to SWIFT data. It is only the fifth largest among the currency reserves held globally. Will this continue to grow till 2035, given that the current dilemmas of the Chinese policymakers have already led to capital controls and capital flight? Chinese citizens can take only $50,000 abroad. It’s a known unknown.

Japan is growing slowly, but it has grown nevertheless, and it remains a global trading power. It is now investing in initiatives rivalling the Belt and Road Initiative. It still holds huge external reserves. It’s at the cutting edge of many new transformative technologies. Now, it is developing massive deterrent missile forces, though they remain demographically negative. India’s growth is expected to remain steady at around 6 to 7 per cent, so it should overtake Germany and Japan to emerge as the third-largest economy well before 2035. India has demonstrated the potential to play a greater role in international finance bailing out Sri Lanka is a great example. However, its flip-flops in trade policy are not helping it expand its influence.The rupee is still not a player abroad. And energy remains like a ball and chain hobbling its growth. Yet, it has demonstrated a strategic economy. Another known unknown is whether the 2024 elections in India will impact its trajectory.

POLITICO-MILITARY

The status of Asia in 2023 is believed to be encouraging as Europe and the Levant are bogged down in Asia’s actual war, while the rest of Asia is not. However, military expenditures remain very high, including in ASEAN.

09 ASIA UNLEASHED: THE POWER PLAY BEGINS

There are tensions in the Taiwan Straits, South China Sea, and Northeast Asia. The standoff between India and China in Ladakh continues. And in all these situations, the central actor is China. Then there is Pakistan, domestically turbulent but still sponsoring terrorism. Their border with Afghanistan is also volatile, and there are too many unknown unknowns in the trajectory of India’s Western borders.

The possibility of Iran getting into a conflict with Israel persists. The trajectory of Iran-U.S.-Israel relations is the biggest unknown because of oil. Oil and gas will in 2035 still be the dominant energy sources for Asia, and a crisis in the Gulf could derail energy management and trade balances across Asia, just as the 1973 oil shock slowed down Europe. Today, four top oil importers are Asian- China, India, Japan, and South Korea. All five top LNG importers till last year were Asian - Japan, China, India, South Korea and Taiwan. The U.S. is sitting pretty in this situation as the world’s largest oil and gas producer.

Amongst the forecast of drivers and factors, one is political change. Will China’s political direction remain as it is? One simple signal. The sentiments expressed over the death of Li Keqiang, the former premier, had shades of mourning when Prime Minister Zhou Enlai died. It reflected public grief for an era of greater growth and possibility.

Does it mean something? Can growth in Asia continue on the same path, given that the financial situation in the world is changing? Military-industrial complexes are growing rapidly in all the key countries and will be one factor. However, not one Asian country has successfully designed a jet engine, whether commercial or military.

SOME SCENARIOS

2035 will not mark the milestone of the Asian cen-

tury. For China to define the Asian century, domination over Asia is essential. Historically, China has never had domination except for East and parts of Southeast Asia.

Apart from that, Japan, Korea, India, Iran, as well as Vietnam, Philippines, Indonesia, etc., will not go along with a Chinese-dominated order. The U.S. is also not standing still and is determined to retain global preponderance in Asia.

The best-case scenario is that the Chinese trajectory gets redefined either through internal change or by coexisting with the U.S. for a free and open Indo-Pacific, the Quad and a cold peace.

The most likely scenario is that China will not change course but will reach some temporary modus vivendi with the U.S. Japan, Korea and Australia remain closely tied to the U.S. ASEAN’s hedging strategy continues.

The growth of India, Indonesia, and Vietnam proceeds in a way that makes Chinese dominance less likely, though China will have the largest weight in Asia. We have several Black Swans - Taiwan, another war in the Gulf, the PLA deciding to push India around, North Korea out of control, another pandemic, etc.

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR INDIA

• Economy, economy, economy! Domestic first and regional integrations.

• Get other Asians to push for United Nations Security Council reform, provided the UNSC remains relevant.

• India needs to build Asian dialogues, leading to institutional structures like Europe, which was able to build with the Organization of Security and Cooperation in Europe once detente started.

10 ASIA UNLEASHED: THE POWER PLAY BEGINS

ASIA 2035: DRIVER OF A BETTER WORLD

“We need to continue to strengthen economic globalisation.”

The world is undergoing tremendous challenges and is much more dangerous than it used to be. We have experienced prosperity and peace for the past seventy-seven years since the Second World War. The Bretton Woods system built a world that has kept us going, but that system seems unable to function effectively now. Then there are multiple crises- in the Europe continent, the war in Ukraine and the Palestine/ Israel conflict.

The trend towards internationalisation and globalisation will continue because globalisation is the product that has kept us going for the last 77 years without having a third world war. Trade has gone up several hundred times since the Second World War. And we are all better off than we used to be. China is a good example; it has lifted 800 million people out of poverty. And India, too, has benefited.

There is a big Global South in which China and India can work together to strengthen globalisation. The Global South represents 80 per cent of the global population. The unipolar world is going, and we see the emergence of a multipolar world. The doubling of member countries in BRICS (from five to 11) is a sign, and China, India, and other members of BRICS are playing a leading role in this enterprise. The BRICS is an economic organisation that drives economic development and neo-development banks, Asian infrastructure banks etc.; India is the largest recipient of investment from these banks. Hopefully, the member countries of the enlarged BRICS can work together well.

China’s BRI is openly exclusive, welcoming other economic frame workers to collaborate - for example, with B3W (Build Back Better World, an international infrastructure investment initiative announced by the G-7 in June 2021 to counter BRI), EU Global Gateway, and India’s IMEC. All those infrastructures that are common consensus now should work together.

The next big trend is that along with BRICS, the Global South will create a new infrastructure revolution that will shape the world for better connectivity and understanding and prevent future conflicts. Climate is the next biggest challenge for the whole of mankind. We should first de-risk ourselves from climate threats. China, India, the U.S. and the EU must all work together to fight climate change. As big countries, we all have

a moral responsibility to prevent our Earth, our global village, from falling apart and being threatened by this climate change danger.

Digital and AI create new challenges. We have AI, data flows, etc. technologies, but they need a governance model. The world must collaborate to create the next generation of global governance in different spheres. AI is a double-edged sword, and we have to harness its good side and make it work for the benefit of mankind.

On its part, China is ready to make its contribution. It has been a full dialogue partner of the ASEAN since 1996; it wants to join the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), a higher standard of free trade agreement. China also has economic summits with Africa, Latin America, Central Asia, the Arabs and ASEAN. China looks forward to an India-China economic cooperation as there are many complementary and supplementary roads here, and both countries can contribute. Economic globalisation is the best way to go forward-trade, investment, connectivity- and to prevent future conflict. Work on transparency, people-to-people exchanges, investment and infrastructure can bring a better world together.

RECOMMENDATIONS

• India and China should work together to strengthen the multilateral system; the old unipolar world is no longer functional. We need a multipolar world, but there’s not yet a multipolar system to support that. China, the EU, the U.S., India, and the Global South must work together. G20, BRICS and other platforms can strengthen communication and dialogue.

• There should be more people-to-people exchanges. China had 150 million people touring around the world before the pandemic. China is still sending a lot of tourists and student exchanges. China welcomes international students; before the pandemic, 20000 Indian students were studying in China, and we need more of them! India and China share a cultural heritage at their roots, which needs to be strengthened.

• Economic globalisation must be strengthened. Thanks to the Bretton Woods system, trade has prevented a global conflict for the last 78 years. Let us continue to do that.

DR HUIYAO WANG

President, Center for China and Globalization

SYNERGIA CONCLAVE 2023

2035: PEERING INTO INDIA’S ECONOMIC FUTURE

Given the tumultuous geopolitical landscape, what does 2035 hold for the Indian economy?

Suchitra

Padmanabhan

is the Policy Research Associate at Synergia Foundation and has Post Graduate Degree in Social Policy & Planning from the London School of Economics.

India ranks among the fastest-growing economies globally and is positioned to sustain this trajectory, aspiring to attain high-middle-income status by 2047, marking the centenary of Indian independence. The nation is resolutely committed to navigating the challenges of climate change, aligning with its ambitious target of achieving net-zero emissions by 2070.

Despite these advancements, certain challenges persist. Consumption inequality endures, reflected in a Gini index hovering around 35 for the past two decades. Child malnutrition remains a concern, with 35.5 per cent of children under five years experiencing stunting, a figure that rises to 67 per cent among children aged 6-59 months. While headline employment indicators have improved since 2020, apprehensions linger regarding the quality of jobs generated, the actual wage growth, and the relatively low participation of women in the labour force.

INDIA’S GROWTH TRAJECTORY

India’s aspiration to achieve high-income status by 2047 will need to be realized through a climate-resilient growth process that delivers broad-based gains to the bottom half of the population. Growth-oriented reforms must be accompanied by an expansion in good

India is poised to surpass Japan and secure its position as the second-largest economy in Asia by 2030. The Indian economy, having experienced two consecutive years of rapid growth in 2021 and 2022, has sustained robust expansion throughout 2023.

jobs that keeps pace with the number of labour market entrants. At the same time, gaps in economic participation will need to be addressed, including by bringing more women into the workforce.

After real GDP contracted in FY20/21 due to the COVID-19 pandemic, growth bounced back strongly in FY21/22, supported by accommodative monetary and fiscal policies and wide vaccine coverage. Consequently, in 2022, India emerged as one of the world’s fastest–growing economies despite significant global environmental challenges–including renewed supply line disruptions following the rise in geopolitical tensions, the synchronized tightening of global monetary policies, and inflationary pressures.

In FY22/23, India’s real GDP expanded by an estimated 6.9 per cent. Growth was underpinned by robust domestic demand, strong investment activity bolstered by the government’s push for investment in infrastructure, and buoyant private consumption, particularly among higher-income earners. The composition of domestic demand also changed, with government con-

ECONOMICS

sumption being lower due to fiscal consolidation. Since Q3 FY22/23, however, there have been signs of moderation, although the overall growth momentum remains robust. The persisting headwinds – rising borrowing costs, tightening financial conditions and ongoing inflationary pressures – are expected to weigh on India’s growth in FY23/24. Real GDP growth will likely moderate to 6.3 per cent in FY23/24 from the estimated 6.9 per cent in FY22/23.

The general government fiscal deficit and public debt to GDP ratio increased sharply in FY20/21 and have been declining gradually since then, with the fiscal deficit falling from over 13 per cent in FY20/21 to an estimated 9.4 per cent in FY22/23. Public debt has fallen from over 87 per cent of GDP to around 83 per cent over the same period. Increased revenues and a gradual withdrawal of pandemic-related stimulus measures have largely driven the consolidation. At the same time, the government has remained committed to increasing capital spending, particularly on infrastructure, to boost growth and competitiveness.

POSITIVE SIGNALS

According to the latest India Development Update (IDU) from the World Bank, India persists in demonstrating resilience amidst a challenging global environment. Despite considerable global hurdles, the report, which serves as the Bank’s flagship semiannual overview of the Indian economy, notes that India achieved a growth rate of 7.2% in FY22/23, making it one of the fastest-growing major economies. India’s growth rate was the second-highest among G20 nations, nearly double the average for emerging market economies. This resilience was driven by robust domestic demand, substantial public infrastructure investment, and a strengthening financial sector. Bank credit growth also increased to 15.8% in the first quarter of FY23/24, compared to 13.3% in the same period of FY22/23.

However, the IDU anticipates that global challenges will persist and intensify due to high global interest

rates, geopolitical tensions, and sluggish global demand. Consequently, global economic growth is expected to decelerate over the medium term, influenced by these combined factors.

Given these circumstances, the World Bank projects India’s GDP growth for FY23/24 to be 6.3%. This expected moderation is primarily attributed to challenging external conditions and diminishing pent-up demand. Nevertheless, the service sector is anticipated to maintain strong activity with a growth rate of 7.4%, and investment growth is projected to remain robust at 8.9%.

Auguste Tano Kouame, the World Bank’s Country Director in India, commented on the short-term challenges posed by an adverse global environment, emphasizing the need for tapping into public spending to attract more private investments, thereby creating more favourable conditions for India to seize global opportunities and achieve higher growth in the future.

Recent months saw a spike in inflation, reaching 7.8% in July, driven by increased prices of food items like wheat and rice due to adverse weather conditions. The World Bank expects inflation to gradually decrease as food prices normalize and government measures enhance the supply of key commodities.

Dhruv Sharma, Senior Economist at the World Bank and lead author of the report projects a moderation in inflation, asserting that overall conditions will remain conducive for private investment. He also anticipates the growth of foreign direct investment in India as the global value chain rebalances.

Looking at fiscal indicators, the World Bank foresees fiscal consolidation continuing in FY23/24, with the central government fiscal deficit is projected to decline from 6.4% to 5.9% of GDP. Public debt is expected to stabilize at 83% of GDP. On the external front, the current account deficit is anticipated to narrow to 1.4% of GDP, with sufficient financing from foreign investment flows and support from large foreign reserves.

13 2035: PEERING INTO INDIA’S ECONOMIC FUTURE

OUTLOOK

According to a report unveiled by S&P Global, the nation’s GDP is anticipated to expand from 6.4% in 2023 to 7% in 2026. The report foresees India ascending to the third-largest economy by 2030. Presently, India ranks as the fifth-largest economy globally, trailing behind the U.S. China, Germany, and Japan.

“We see India reaching 7 per cent in 2026-27 fiscal... India is set to become the third-largest economy by 2030, and we expect it will be the fastest-growing major economy in the next three years,” S&P said.

As per the “Global Credit Outlook 2024” published by S&P, India is expected to lead as the fastest-growing emerging market worldwide.

However, determining whether the country can successfully transform into the next major global manufacturing hub is a crucial challenge.

The report further underscores that India’s growth is projected to be 6.4% in the fiscal year 2023-24, marking a decrease from the 7.2% recorded in the preceding financial year. The rating agency anticipates that the growth rate will persist at 6.4% in 2024-25 before witnessing an upturn to 6.9% in the subsequent year, eventually reaching 7% in 2026-27.

DETERMINANTS OF CHANGE

“A strong logistics framework will be key in transforming India from a services-dominated economy into a manufacturing-dominant one,” according to the report.

The rating agency emphasises the importance of India’s ascent as a global manufacturing hub, highlighting a significant opportunity for the country. It underscores the need for a robust logistics framework to transition India’s economic focus from service-oriented to manufacturing-dominated.

To unlock the potential of the labour market, S&P recommends enhancing the skills of workers and increasing female participation in the workforce. The agency believes that success in these areas will enable India to harness its demographic dividend.

“Success in these two areas will enable India to realise its demographic dividend,” it said.

S&P emphasizes that the flourishing domestic digital market in India has the potential to drive the growth of the high-potential startup ecosystem, particularly in financial and consumer technology, in the upcoming decade.

James Sullivan, the Managing Director of Asia Pacific Equity Research at JPMorgan, anticipates that the Indian economy will double to $7 trillion by 2030, with the manufacturing sector’s contribution increasing to nearly 25% from the current 17%. Additionally, he foresees exports doubling to over a trillion dollars. Sullivan envisions India ascending to the position of the world’s third-largest economy by 2027 as part of this growth trajectory.

According to the S&P Global report, India is poised to surpass Japan and secure its position as the second-largest economy in Asia by 2030. The Indian economy, having experienced two consecutive years of rapid growth in 2021 and 2022, has sustained robust expansion throughout 2023.

Currently holding the rank of the world’s fifth-largest economy, India is projected to surpass Japan and claim the position of the third-largest global economy, boasting an anticipated GDP of $7.3 trillion by 2030, according to the latest report from S&P Global Market Intelligence.

POSITIVE NEAR-TERM HORIZON

S&P Global underscores an optimistic near-term economic outlook, projecting sustained rapid expan-

14 2035: PEERING INTO INDIA’S ECONOMIC FUTURE

sion throughout 2023 and 2024, primarily driven by robust domestic demand. The report also points to a decade-long influx of foreign direct investments (FDI) into India, reflecting the nation’s favourable long-term growth prospects, supported by a youthful demographic profile and increasing urban household incomes.

According to the report, India’s nominal GDP, measured in USD terms, is anticipated to surge from $3.5 trillion in 2022 to $7.3 trillion by 2030. This substantial growth trajectory is expected to position India as the second-largest economy in the Asia-Pacific region, surpassing Japan. By 2030, it is projected to exceed that of Germany.

The United States currently maintains its position as the world’s largest economy, boasting a GDP of $25.5 trillion, representing a quarter of the global GDP. China follows as the second-largest economy, with a GDP of approximately $18 trillion, constituting nearly 17.9 per cent of the world GDP. Japan ranks as the third-largest economy with a GDP of $4.2 trillion, and Germany holds the fourth position with a GDP of $4 trillion.

LONG-TERM GROWTH DRIVERS

S&P Global outlines several key factors supporting India’s enduring economic prospects. These factors encompass a swiftly expanding middle class, driving consumer spending, a thriving domestic consumer market, and substantial investments from multinational corporations across diverse sectors such as manufacturing, infrastructure, and services.

Moreover, India’s ongoing digital transformation is poised to accelerate the growth of e-commerce, reshaping the retail consumer market in the next decade. The

EXPERT COMMENT

INDIA’S MEGA FUTURE!

India has progressed, profited and has a mega future interest in global leadership. I can hardly imagine any country, except perhaps the EU - if it does its work well - that can have such an impact, thinking 50 years ahead.

China is looking into itself, India is global, the U.S. is troubled, and Europe is slow, but in my view, it is building itself. What 1.5 billion Indians can do in the long term is something that is more powerful than any other geopolitical force seen from a long-term perspective.

Corruption is what undermines logical thinking of

report highlights that this transformation has attracted investments from global technology and e-commerce giants into the Indian market. The projection indicates that by 2030, the number of internet users in India will reach 1.1 billion, doubling from the estimated 500 million in 2020.

The report underlines the resilience of India’s Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) inflows, which have shown consistent momentum over the past five years, even amid the pandemic years of 2020-2022. Notably, investments from global technology multinationals (MNCs) and a notable increase in FDI from manufacturing firms contribute significantly to this ongoing growth.

Assessment

India is expected to persist as one of the globe’s swiftest-growing economies in the coming decade, establishing itself as a vital long-term growth market for multinational companies spanning diverse industries. This encompasses manufacturing, services, and sectors such as banking, insurance, asset management, healthcare, and information technology.

As 2035 appears on the economic horizon, India has a number of prosperity-supporting trends, including its digital transformation, technological moorings, a rapidly growing middle class, propelling consumer spending, a flourishing domestic consumer market, and significant investments from multinational corporations.

what the political economy needs to face. In my view and experience, I look to India to be a vocal leader on these issues. India, surely, will be a leader in the technological realm. I know that in comparison with other regions, India is but a short step from leadership.

We stand a chance if we have the courage to put wellbeing at the core of our understanding of prosper ity rather than the usual economic measure ments?

PROF MATS KARLSSON

Former

VP of World Bank

15 2035: PEERING INTO INDIA’S ECONOMIC FUTURE

SYNERGIA ASSESSMENT

ASIA 2035

The idea of the ‘Asian Century’ argues that the 21st-century international order will be defined by Asia’s pre-eminence, the way the U.S. pre-eminence defined the international order in the 20th Century and Europe in the 19th Century.

Asia’s economic revolution —stimulated by many countries on the continent—over the past 60 years is unprecedented.

However, given the transformational events that have occurred in the recent past, does the concept of an Asian Century still hold? Is economic heft sufficient for Asia to claim the Century?

More importantly, what are the Key Drivers or factors that will impact the trajectory of Asia over the next ten years, and what are the plausible scenarios that could emerge in Asia by 2035?

Also, looking at the future of Asia in isolation without examining the continent’s economic opportunities, challenges and projected growth would render any discussion on the subject incomplete.

No doubt, the realisation of the Asian Century will be a long-drawn process that will require cooperation between China and India. It will only be by the 2070s that Asia

KEY DRIVERS

When it comes to identifying the Key Drivers of change that will impact the next 10 to 15 years at a Global and Asian level, the following major aspects come to the fore:

• Peace/ absence of conflicts.

• U.S. China Strategic Competition.

• Globalisation in the face of onshoring.

• Power diffusion and the rise of the Global South lead by Asia.

• Relevance of alliances.

• Climate change will be a common risk across the board

• Global digital interconnectivity cannot be ignored.

Recommendations.

The world should take a cue from ASEAN and extrapolate its functioning in a wider context to ensure peace or an absence of conflict.

Climate change and the regulation of AI are two areas that need global cooperation on priority.

The international order must be in sync with the evolving global balance of power.

MAJOR GENERAL PAUL NAIDU (RETD)

Chief Strategic Officer, Synergia

16 SYNERGIA ASSESSMENT - ASIA 2035

-

SYNERGIA CONCLAVE 2023

INDO-PACIFIC CHALLENGES

Indo-Pacific is a natural region where the destinies of constituent nations are deeply interlinked.

This article is based on the address given by Admiral R Hari Kumar, Chief of the Naval Staff, Indian Navy, at the 9th Synergia Conclave 2023.

The most contemporary global issue is the centrality of the Indo-Pacific region and the Indo-Pacific strategy. There are eight countries and two international constructs that have already come out with their Indo-Pacific strategies.

GEOGRAPHICAL CHALLENGES

Geography is one constant in an ever-changing world of human interactions that cannot be significantly altered. Surprisingly, the term Indo-Pacific is essentially geographic, with the Indian Ocean and the Pacific Ocean fused into one homogeneous entity.

On the one hand, the Indian Ocean is geographically the smallest, geologically the youngest and geo-strategically the most complex, with an uninterrupted land capping to the north, maritime choke points to the east and the west, limiting access and the barren, ice-clad Antarctica to the south. It is recorded that it has been travelled at least 5000 years ago.

On the other hand, the Pacific is the largest ocean of them all. It is free to both the north and the south.It is empty at its core, but as one reaches to its rim to the west, fault lines become quite prominent. The Pacific Ocean is the next oldest travelled ocean after the Indian Ocean. It is recorded that it has been travelled as much as 2000 years ago.

Given the expanse of the Indian Ocean region, 20 times the landmass of Bharat, and that is only IOR, not the Indo-Pacific, no one can do it alone, and therefore, there is a need to collaborate with likeminded partners. Bharatiya Nav Sena collaborates and cooperates with likeminded navies to strengthen collective maritime competence.

This region has some of the world’s deepest oceanic trenches as well as the highest mountains. It is home to nearly two out of every three island nations in the world and seven of the ten largest continental nations. It has some of the world’s least populated or sparsely populated regions and the most densely populated ones; it is a region of contradictions.

However, one feature that unites them is the oceans. The dependence on the monsoons is the defining climatological attribute of the Indian Ocean. On the Pacific, El Nino on the South American coast perhaps sums up the interconnect between these waters. The monsoons bring rain to the core of the Indo-Pacific, South and Southeast Asia, watering the fields, feeding the populace, and driving growth and prosperity. Therefore, the region’s predominant characteristic is its maritime orientation.

The Indo-Pacific is a natural region where the destinies of constituent nations are deeply interlinked. History is testimony to the fact that cultural and civi-

SYNERGIA CONCLAVE 2023

lizational connections in the region were capitalized by seafarers both from ancient times to the current time, and it continues to be so even now.

However, the geography of oceans also means that these bodies are largely uncontrolled, un-owned, ungoverned and unregulated. They are uncontrolled because nearly 70 per cent of the earth is oceans, 85 per cent of nation-states have access to the seas, yet its fluidity means that one cannot seize, hold, or occupy the vast waters. The seas essentially remain free.

These uncontrolled seas are also largely un-owned. Only about 5 per cent of the seas, being the territorial seas, are confined by the laws of the land, while the remaining 95 per cent are free for navigation and overflight. Therefore, in terms of owning the resource, nearly 90 per cent of the seas by volume and 64 per cent by surface area are beyond exclusive economic zones and, thereby, beyond any state’s jurisdiction.

This lack of legal ownership translates into the seas remaining largely unregulated. Their vastness, accompanied by the tyranny of distance, means that the seas cannot be organized or governed to any significant distance from the shores. These characteristics, in turn, contribute to the oceans being a global commons, free for all to access, navigate and use in pursuit of respective interests. So, being global commons, the oceans also provide unfettered reach and access to nation-states and, therefore, are a medium of choice for power projection. With the Indo-Pacific washing the shores of six of the world’s seven continents, this space is definitely of great strategic importance.

INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS CHALLENGES

The definition of Indo-Pacific as a strategic geography is also a mix of contradictions. For Bharat, just

like for Japan and Australia, it extends from the eastern shores of Africa to the western shores of the Americas. For the U.S. and Canada, it stretches from the Pacific coastline to the Indian Ocean.

China opposes the construct and prefers a more continental Asia-Pacific one. ASEAN puts itself at the centre of it, whatever may be interpreted by others. However, what is undisputed is that players, actors and forces, both regional and extra-regional, are vying for their share of the pie in the resource-rich Indo-Pacific.

The most critical of them is the region’s abundance of human resources. It has nearly 60 per cent of the world’s population, home to some 4.3 billion people, including the world’s most populous countries, Bharat and China. At the same time, the region also contains some of the smallest populations on the planet, especially among the small island developing states of the region.

This diversity results in equally divergent aspirations and interests of people and states, often leading to competition and contestation. Other resources like food, fuel, minerals, rare earth elements, etc., are also found in abundance in the region, once again adding to the jostling for consumables in the region.

In addition to the diversities, the region is also characterized by the coexistence of almost the entire gamut of political systems. From monarchy to republics, democracy to autocracy, capitalism to communism or socialism, by-party to multi-party systems, kings, presidents, prime ministers, and premiers all hold sway over the regions.

Such a heterogeneous mix results in differing worldviews and outlooks. Therefore, the US-China Great Power Competition is being played out in the region across geographies, spheres and sectors. As they vie for

18 INDO-PACIFIC CHALLENGES

influence, one witnesses hedging being adopted by several states to further their interests. This has given rise to a number of mini-laterals and multilaterals as well as infrastructure and financing initiatives in the region, often at the expense of the other.

Some states are attempting to alter the basic control of the global commons to seek greater domination and control.

SECURITY CHALLENGES

There is an increasing challenge to universally accepted rules, regulations and conventions, turning global commons into contested seas. China, for instance, is pushing the envelope – be it debt traps or unilateral actions, encroachments in the South China Sea or, altered geography or expansionist designs in the Indian Ocean with the acquisition of ports and bases.

What many see as a response: the AUKUS deal has added to the mix of an already nuclearized region as almost all nuclear weapon states are either located in the Indo-Pacific or have a military presence there.

The region is also home to 9 of the 10 largest standing armies and 7 of the 10 highest defence spenders with 105 active conflicts. It accounts for the highest number of conflicts globally. It also hosts some of the most volatile hotspots from West Asia to the Horn of Africa, the South China Sea and the East China Sea.

We are witnessing the ongoing Israel-Hamas conflict, spilling out into the Red Sea and thereby into the Indo-Pacific. Regarding the maritime domain, the region has the credible presence of many extra-regional forces.

The Indian Ocean, North Indian Ocean alone at any point in time has upwards of about 50 warships of extra-regional forces, which remain deployed for various missions, including anti-piracy patrols off the Gulf of Aden. This means there is greater interaction between them at sea, and if these are not managed well, there is a greater possibility of miscalculation and perhaps conflict.

The unconventional challenges of military aggression have and will continue to exist in the maritime domain. In addition, other challenges such as transit rights, piracy, armed robbery at sea, maritime terrorism, humanitarian crises necessitating evacuation operations, trafficking, smuggling, illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing, and proliferation of private armed security all make the maritime security metrics quite complicated.

In 2022, Bharat’s Information Fusion Centre monitored about 4,728 maritime incidents in the Indian Ocean region alone. Additionally, there is also the Grey Rhino of climate change. With the continuous rise in sea levels, many states in the region are likely to face existential crises.

In the words of Fiji’s defence minister, “Machine guns, fighter jets, grey ships and green battalions. They are not our primary strategic concern.

Waves are crashing at our doorsteps; winds are battering at our homes. We are being assaulted by this enemy from many angles.”

TRADE AND ECONOMIC CHALLENGES

Sixty-two per cent of the global GDP is in this region, with the USA, China, Japan, and Bharat being four of the top five economies resident here.

Seven of the top ten export destinations are in the Indo-Pacific, but half of the global trade transits through the maritime trade routes in the region, and nine out of the ten busiest ports in the world are in the Indo-Pacific.

For Bharat as well, about 90 per cent of trade by volume, more than 70 per cent by value, and nearly 90 per cent of our oil imports are transported by the seas. Four-fifths of Bharat’s oil, half of the natural gas and half of LPG are imported from the Indo-Pacific nations.

Such vast trade and economic enterprise is underpinned by the unmatched efficiency that maritime transport affords.

Therefore, maritime transportation will remain the most efficient means for a very long time unless some new means of transportation, maybe quantum transportation or something like that, is invented later.

Given the maritime orientation of the Indo-Pacific, navies and maritime security agencies will play an important role in providing an overarching security umbrella.

ROLE OF THE INDIAN NAVY

Through sustained presence, credible responses, cooperation, and collaboration with friends, Bharati Nav Sena adds value to the Indo-Pacific, both figuratively and literally.

Given the expanse of the Indian Ocean region, 20 times the landmass of Bharat, and that is only IOR, not the Indo-Pacific, no one can do it alone, and therefore, there is a need to collaborate with like-mind ed partners.

Bharatiya Nav Sena collaborates and cooper ates with like-minded navies to strengthen collective mar itime competence. Each Navy or nation in the Indo-Pa cific, big or small, brings certain unique capabili

19 INDO-PACIFIC CHALLENGES

ties to the table. Expertise, area knowledge, area understanding, nuances, intelligence, information, technology, geographical locations, assets, etc.

One prime example of the Indian Navy’s endeavours in this regard is its mission-based deployments. In the past two years, its ships clocked about 17,000 days at sea, with submarines deployed extensively for over 1,800 days and aircraft logged over 26,000 hours. At any given time, assets are deployed across India’s areas of interest to respond to contingencies that may arise.

India’s credibility has been further strengthened by the fact that it is fast becoming self-reliant to a large extent in its defence capabilities, especially with regard to shipbuilding.

The indigenous content on board Indian warships has consistently increased since the first indigenous capital warship, Nilgiri, was commissioned more than five decades ago.

It has now reached 75 per cent onboard India’s first indigenous aircraft carrier, Vikranth, the state-of-theart Vishakhapatnam class stealth destroyers, and the new Nilgiri, presently under construction, setting the stage for a transformative change.

Indian defence products may find applicability and use for our friends in the region. The Atma Nirbharta Initiative will further contribute to collaborative security in the Indo-Pacific region.

At the strategic level, the Indian Navy is actively pursuing endeavours under the ambit of government initiatives such as the Act East Policy, ASEAN, ADMM+, IORA, Indian Ocean Commission, IPOI, Djibouti Code of Conduct and so on. All these initiatives provide the necessary framework for meaningful and constructive dialogue and form the basis for the Navy’s engagement with like-minded maritime nations.

At the operational level, initiatives such as standing arrangements for faster operational turnaround of assets, that is, reciprocal logistic agreements for interoperability and operation of surface air assets submarines from each other’s bases access facilities, all this help improve interoperability, enhance security and reaffirm our commitment to be the first port of call for our friendly maritime nations in the Indo-Pacific.

In addition, forging collaborative frameworks such as the Indian Ocean Naval Symposium, the Goa Maritime Conclave, and the Milan exercise are important elements of our commitment to the region.

India has established the Information Fusion Centre as the IOR’s hub of maritime security information. Through white shipping agreements with 25 countries and one multinational construct, 15 countries have been invited to join the centre.

The Navy works towards enhancing the capability of friends in the region by providing assets, installing coastal radar chains, and training personnel from friendly foreign navies.

Holistic maritime security in the region cannot be achieved by Bharatiya Navsena alone. The overarching outlook is towards finding regional solutions to regional problems.

The approach towards addressing regional problems is expanding the ambit of engagements to the free flow of ideas, experiences, organizations, cultures and best practices. This will further harmonize our endeavours in the Indo-Pacific, adding more value to not only Bharati Navasena’s effort but also to other like-minded states.

20 INDO-PACIFIC CHALLENGES

Conclusion

SUSHI AND SPICES: DECODING THE INDO-JAPAN ALLIANCE

The India-Japan partnership extends beyond bilateral ties, finding expression in trilateral arrangements and the Quad framework.

Sambratha Shetty is the COO at Synergia Foundation and holds a Masters’ in Science from the University of Greenwich, UK.

The evolving dynamics of the Japan-India relationship have been shaped by a combination of historical ties, economic complementarity, and shared concerns over regional security, particularly in light of China’s growing influence. To better understand this important relationship, one must undertake a journey into its history, economic angle and strategic partnership with a focus on the Quad framework.

HISTORICAL CONTEXT

Japan and India share a long history of cultural exchange dating back to ancient times. Most striking is Buddhism, which originated in India and spread to Japan around the 6th century, fostering a deep cultural connection. The 8th-century work, “The Nihon Shoki,” mentions Japanese envoys visiting India, laying the foundation for diplomatic engagements. Large number of Japanese make a pilgrimage to Bodh Gaya in Bihar, where Gautama Buddha (Prince Siddhartha) attained enlightenment and became the Buddha.

During World War II, thousands of Indians serving with the British Indian Army fell into the hands of the Imperial Japanese Army in Singapore, Malaya and later in Burma. The narrative of their treatment at the hands of their capturers is a horrendous story. However, those who volunteered to join the rebel Indian National Army

The India-Japan partnership has become indispensable in navigating the complexities of the changing global order. With a shared commitment to democratic values, economic growth, and regional stability, both nations are likely to continue their positive trajectory. While challenges exist, such as economic and bureaucratic hurdles, the benefits of collaboration far outweigh the obstacles.

created by Japan fared much better. Post-World War II, Japan and India found themselves on a path of recovery and development. The 1952 Peace Treaty marked a turning point, ending hostilities and establishing diplomatic relations between the two nations. However, during the Cold War, geopolitical alignments and economic vision differences kept the two nations at a guarded distance.

The post-Cold War era saw a significant shift, driven by economic complementarity and shared concerns over China’s regional influence. India’s “Look East Policy”, initiated by Prime Minister P. V. Narasimha Rao in 1993 marked a turning point, opening avenues for increased engagement with successful Asian economies.

The relationship weathered a brief setback in 1998 following India’s nuclear tests, but by 2018, under the leadership of Prime Ministers Modi and Abe, it was elevated to a “special strategic and global partnership.”

ECONOMIC COLLABORATION

Economic ties between Japan and India have flourished, with Japan playing a pivotal role in India’s infrastructure development. The Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement (CEPA), signed in 2011, further facilitated trade and economic cooperation.

Notable projects, such as the Delhi Metro and Mumbai-Ahmedabad High-Speed Rail, highlight Japan’s contributions. In 2021, Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) signed an agreement with the Government of India to provide Japanese (ODA) loan amounting to Japanese Yen 52,036 million (approximately Rs 3,717 Crore) for the development of Phase 2 of ‘R6 (Nagawara- Gottigere, approx. 22.0 km), 2A (Silk Board K R Puram, approx.20.0 km) and 2B ((K R Puram Kempegowda International Airport Terminal, approx.38. 0 km).

The systemic shift in Japan’s national security posture away from pacifism and India’s rising Indo-Pacific profile created opportunities for deeper collaboration. Economic cooperation now focuses on capacity building, with Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) and Japan’s Overseas Development Assistance (ODA) program supporting infrastructure development in India’s Northeast region.

STRATEGIC PARTNERSHIP:

The strategic dimension of the Japan-India relationship has gained prominence, driven by shared apprehensions over China’s activities in the region. The Galwan clashes in July 2020 marked a turning point, prompting India to strengthen ties with friendly powers like Japan to bolster its strategic deterrence against Beijing. Joint military exercises, training programs, and defence equipment and technology transfers underscore the rapid progress in security cooperation.

Japan’s support for India’s entry into prestigious international forums, such as the Nuclear Suppliers Group, and policy coordination in regional and Indo-Pacific institutions contribute to the non-material aspects of India’s global status. The recent announcement by

the Kishida government to expand its ODA program with a focus on enhancing “security and deterrence capabilities” aligns with India’s strategic objectives.

TRILATERALS AND THE QUAD

The India-Japan partnership extends beyond bilateral ties, finding expression in trilateral arrangements and the Quad framework. The India-Japan-US and India-Japan-Australia trilateral dialogues, initiated in 2011 and 2015, respectively, serve as stepping stones to the Quad. These arrangements allow for better coordination and alignment on regional issues, offering a platform for like-minded nations to work together.

The Quad, consisting of India, Japan, the United States, and Australia, has emerged as a key player in the Indo-Pacific region. All four members share a common goal of managing an assertive China and upholding the “rules-based order.” While not an Asian NATO, the Quad provides a loose-knit network for defence cooperation, intelligence-sharing, and logistics support. Ideational elements, such as promoting the Free and Open Indo-Pacific (FOIP) strategy, underline the non-military aspects of the Quad.

LOOKING AHEAD

The India-Japan partnership has become indispensable in navigating the complexities of the changing global order. With a shared commitment to democratic values, economic growth, and regional stability, both nations are likely to continue their positive trajectory. While challenges exist, such as economic and bureaucratic hurdles, the benefits of collaboration far outweigh the obstacles.

As the Quad strengthens its position in the Indo-Pacific, the India-Japan partnership plays a pivotal role in advancing regional security and stability. The ongoing collaboration in various sectors, coupled with diplomatic initiatives, cultural exchanges, and trilateral engagements, positions the relationship for continued growth. The future of the Japan-India partnership looks promising, grounded in a shared vision for a free, open, and prosperous Indo-Pacific region.

22 SUSHI AND SPICES: DECODING THE INDO-JAPAN ALLIANCE

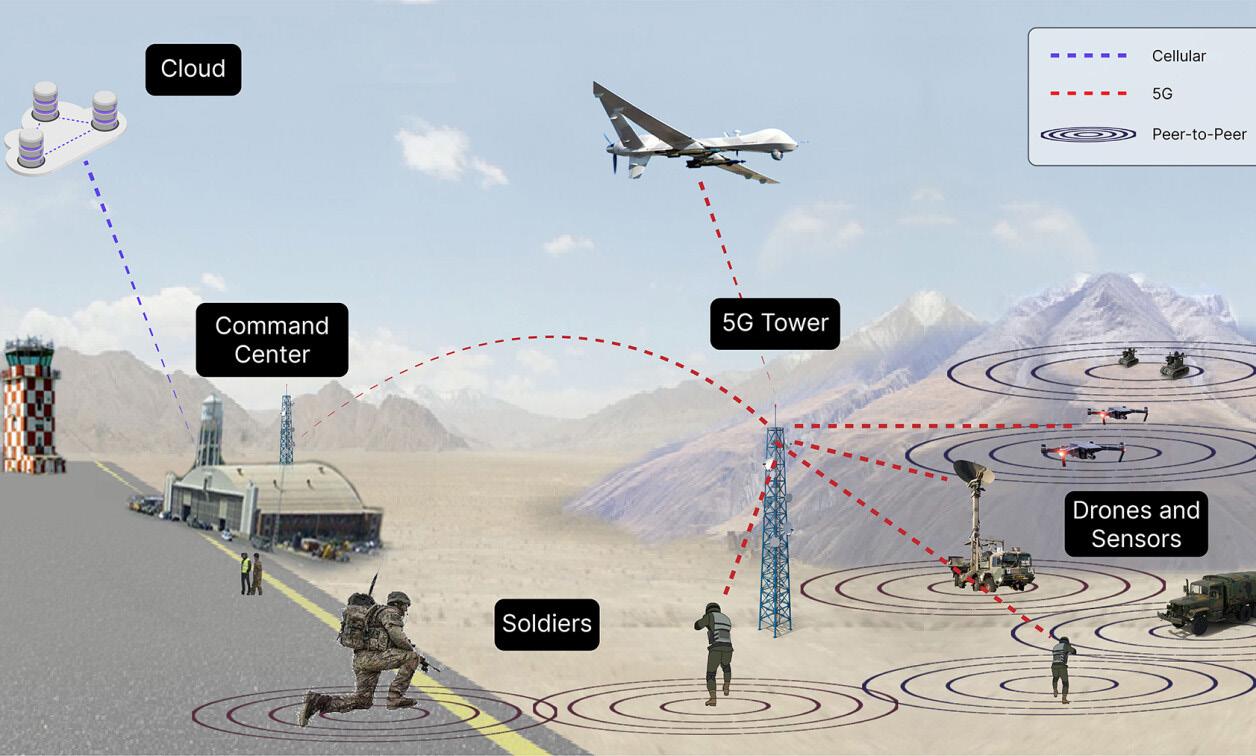

NEW LAND OPERATIONS

Future conflicts will probably be more complex, more lethal and more contested.

This article is based on the round table curated by Lieutenant General Hiroe Jiro, Commanding General, TERCOM - Japan, on New Domains and Land Operations at 9th Synergia Conclave 2023.

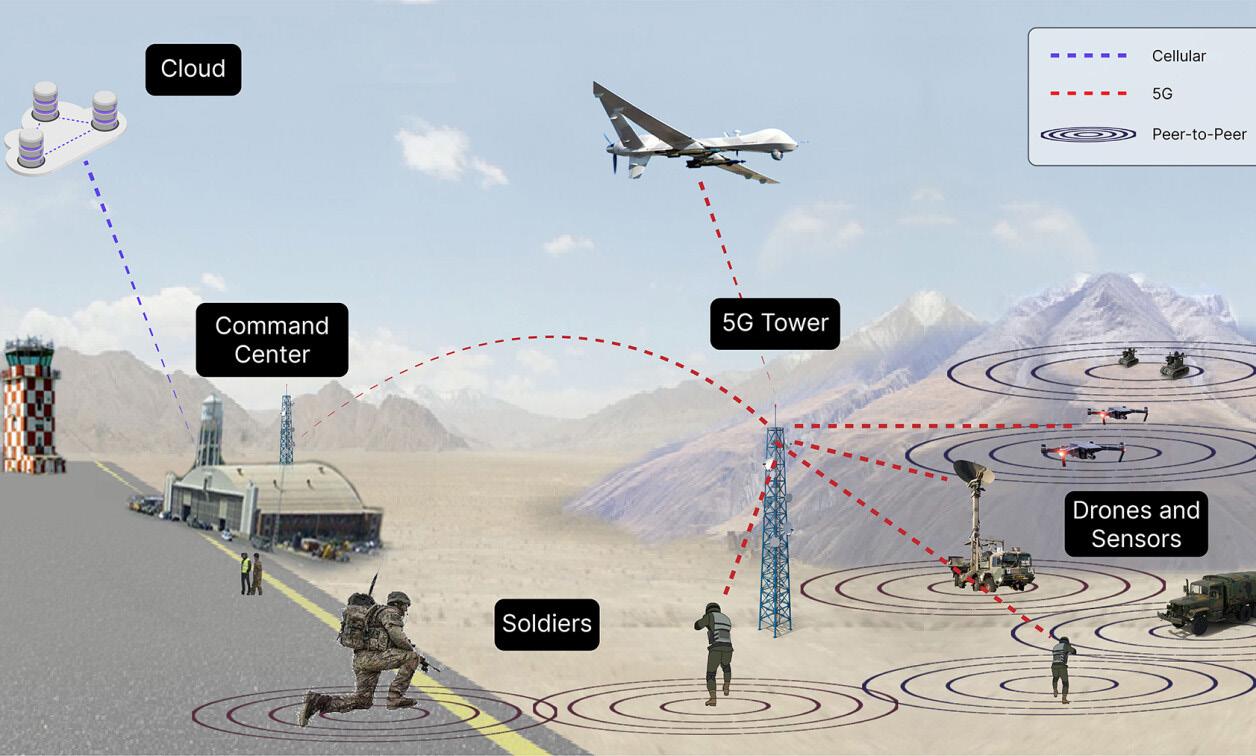

In all future wars, electromagnetic spectrum, cyber, and space superiority will be the keys to the next battlefield. Almost every army in the world is trying to realise the multi-domain operation, which in Japan is called the cross-domain operation. In France, it is called a multi-military operation. The U.S. Army has five domains: land, air, maritime, cyberspace and space. In addition to the five domains, Japan recognises the electromagnetic spectrum as a separate domain. In all future wars, electromagnetic spectrum, cyber, and space superiority will be the keys to the next battlefield.

CROSS-DOMAIN WARFARE IN UKRAINE

In July 2014, in an operation conducted in Ukraine, all indigenous radios of the Ukrainian army were jammed by Russian EW equipment. The Ukrainian forces used their private phone, and the microwaves emitted from those phones were traced by the Russian EW equipment called the Rorandzit. Surprisingly, this equipment can identify the individuals of the Ukrainian forces. Furthermore, this information will be useful in finding out about their families, fathers and mothers. So, the Russian EW units started sending messages directly to the families’ cell phones. For example, your son died. The concerned families tried to call their sons, which increased cell phone traffic and revealed the location of Ukrainian forces. Two Ukrainian platoons were destroyed in this operation. The Ukrainian forces also used satellite communication, but the Russian UAV, called R-110, also detected this communication

The U.S. Army has five domains: land, air, maritime, cyberspace and space.