MEDIA ENABLED APRIL EDITION 2024 | MONTHLY EDITION LOOKING BEYOND THE CURVE SYNERGIA SMALL BUT RESILIENT Page - 03 CONNECTIVITY IN FUTURE CITIES Page - 20 INDIA AND THE INDO-PACIFIC Page - 15 CARNAGE IN CROCUS Page - 26 Page - 41 SEEKING GREEN ENERGY SECURITY EXCLUSIVES CONNECTING THE DOTS: THE FABRIC OF SMART CITIES

INSIGHTS is a strategic affairs, foreign policy, science and technology magazine that provides nonpartisan analysis of contemporary issues based on real-time information. To subscribe, sambratha@synergiagroup.in ; +91 80 4197 1000 https://www.synergiafoundation.org

Dear Reader:

Greetings from the Synergia Foundation!

In our endeavour to comprehensively analyse India’s extended neighbourhood, we have been spreading our wings. This time, we unravel the tiny but influential Gulfdom of Qatar, which has been much in the news in the recent past. Few will deny that Qatar has carved out a unique regional and international geopolitics position despite its unconventional approach. Of course, predictably, we must also give our discerning readers insight into the recent outcome of elections in Pakistan. As you will observe, we have gotten the intelligent views of some top experts from either side of the Radcliffe Line!

Warfare is a dynamic beast that changes shape, size, and tenor with every iteration. This is what makes its study so captivating. In this issue, we look at the recent phenomenon of weaker powers and non-state actors manipulating the wide spectrum of new-age warfare to their advantage; Ukraine and Gaza reflect this paradox.

Why the Indo-Pacific matters to the world and India is a question that is heavily debated in security circles in India. We take this debate to another level by presenting a thought-provoking piece by our naval expert with inputs from subject matter doyens from amongst India’s diplomatic community.

Synergia has always been closely associated with advanced technologies. Recently, we have been advocating the case of Free Space Optical (FSO) Networks, which can play a critical part

Sincerely yours

in implementing India’s ambitious Smart Cities Mission. An article on the subject endeavours to highlight the potential of this technology. Synergia, which has been associated with Africa for more than five decades, has been looking at individual nations on the continent. This time, the spotlight is on Kenya, where a quiet technological revolution is underway, rapidly evolving as a dynamic hub of innovation.

Terrorism continues to run unabated globally, and the heart-rending massacre in Crocus Music Hall only emphasises how non-state actors leverage ongoing conflict to further their own dark agenda. Staying with Russia, we look at the prospect for the Russian Federation after Mr Putin was once again put back on the driving seat in the Kremlin with a thumping margin.

Our economic expert, this time, delves into the complex subject of AI, venturing into the diverse field of economics raising concerns about this convergence of technology and economics. The green advocates in the Synergia research team try to lay down a map for India’s green energy security anchored on its domestic manufacturing. Staying with the environment, we touch upon a subject that is sorely impacting the lives of all Bangloreans this year- rich and poor- India’s hydrosphere security.

We hope our esteemed readers will continue supporting us as we strive to further evidence-based research on strategic issues with global resonance.

Maj. Gen. Ajay Sah Chief Information Officer

Maj. Gen. Ajay Sah Chief Information Officer

EDITORIAL

THE QR CODE TO SUBSCRIBE

FOR FEEDBACK

SCAN

SCAN

CONNECTING THE DOTS: THE FABRIC OF SMART CITIES

A positive movement in the bilateral relationship between India and Pakistan will await the conclusion of Indian elections and formation of a new government..”

-Amb Sharat Sabharwal Page 11

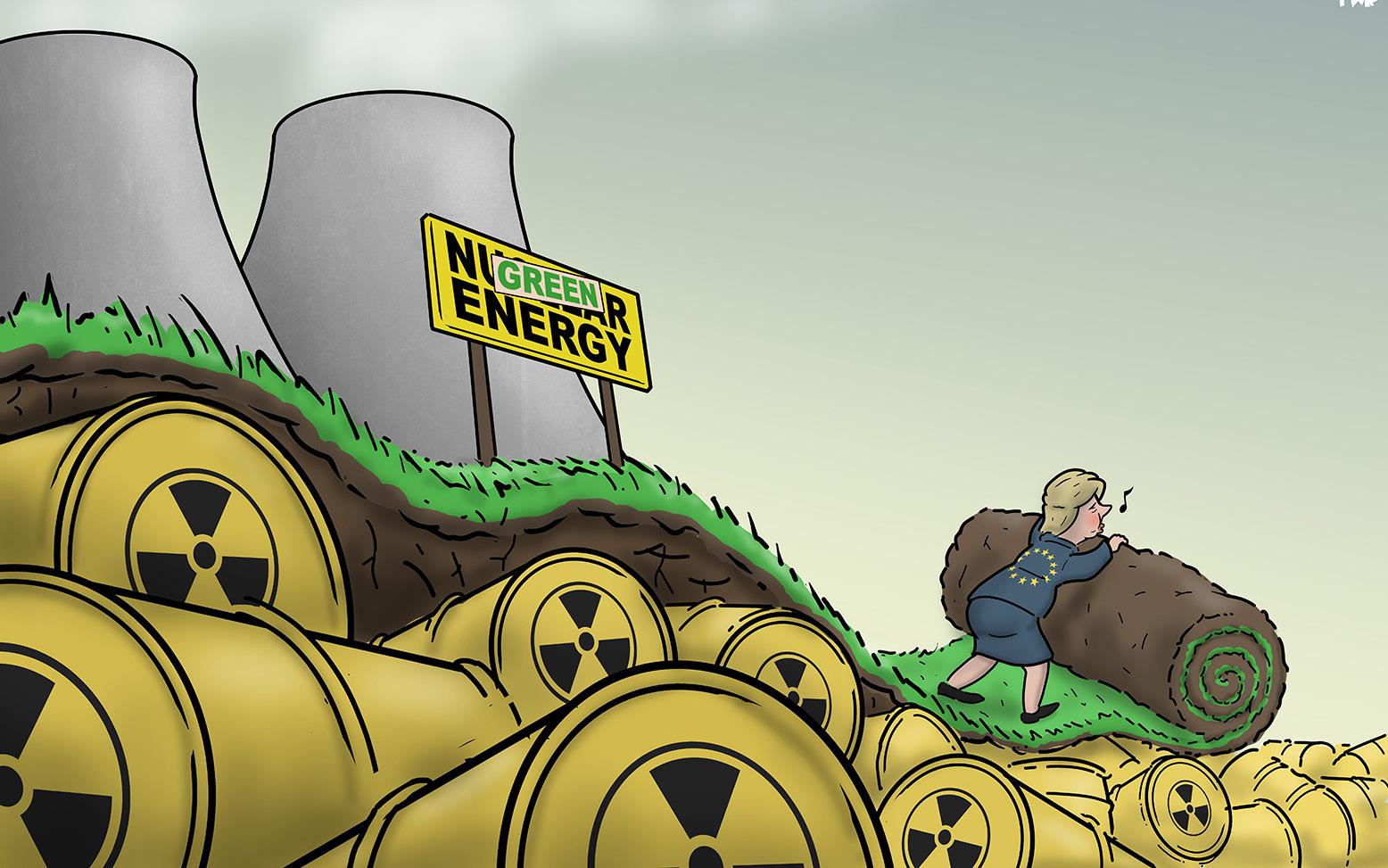

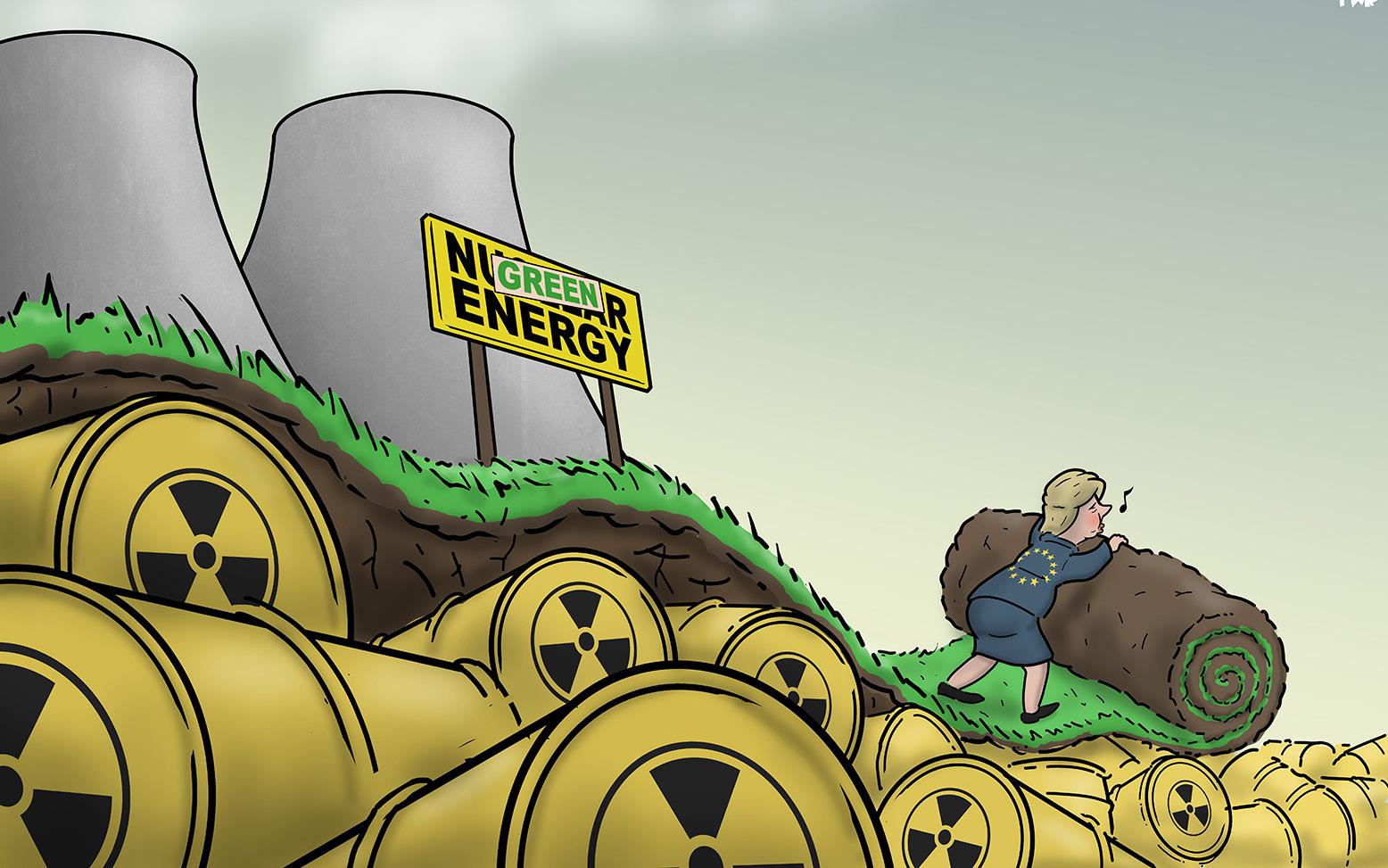

SEEKING GREEN ENERGY SECURITY

To make its goal of green energy security a reality, India must accelerate the domestic manufacturing of its essential sub-systems.

INDIA’S HYDROSPHERE SECURITY

Water security in India needs to be equated with India’s national security discourse.

SMALL BUT RESILIENT

Despite its unconventional approach, tiny Qatar has carved out a unique regional and international geopolitics position.

WARS OF ATTRITION & RESILIENCE

Wars have always been about strategy, tactics, and technology, which holds true even now.

INDIA AND THE INDO-PACIFIC

Why the Indo-Pacific matters to the world and India.

PAKISTAN: PDM 2.0 PROSPECTS

Pakistan Democratic Movement an alliance of more than a dozen parties.

CONNECTIVITY IN FUTURE CITIES

FSO can play a critical part in implementing India’s ambitious Smart Cities Mission

A SILICON SAVANNAH?

Kenya - An evolving hub of innovation?

India’s policymakers have never aspired to be a net security provider for the Indo-Pacific or the Indian Ocean Rim countries.”

-MK. Narayanan Page 19

CARNAGE IN CROCUS

PUTIN’S RUSSIA –POST 2024 POLLS

The need to deal decisively with a resurgent threat has become even more urgent after the Crocus Hall massacre. Putin’s therapy to invigorate Russia emphasises statism and anchored Soviet themes.

AI’S ECONOMICS ANALYSED

AI ventures into the diverse field of economics, raising concerns about this convergence of technology and economics.

APRIL EDITION 2024

‘‘ ‘‘

EXCLUSIVE SPOTLIGHT SPOTLIGHT ENERGY SECURITY GLOBAL SCAN GEOPOLITICS ECONOMICS 03 41 12 15 26 32 37 06 45 20 23 NEIGHBOURHOOD ANALYSIS TECHNOLOGY GLOBAL SCAN 20

strategic affairs, foreign policy, science

technology magazine

nonpartisan analysis of contemporary issues based on real-time information.

INSIGHTS is a

and

that provides

SMALL BUT RESILIENT

Despite its unconventional approach, tiny Qatar has carved out a unique regional and international geopolitical position.

Tarini Dhar Prabhu, Research Associate in Synergia Foundation

Tarini Dhar Prabhu, Research Associate in Synergia Foundation

Qatar is a small country wedged between bigger states in a tough neighbourhood. It has adroitly capitalized on its resource strengths to become financially independent and developed a network that helps it stay resilient.

From being an outlier amongst its Gulf neighbours, it has become a regional mediator and a world-leading natural gas exporter.

RESOURCES AND STRENGTHS

Qatar’s small population, desert climate, and limited ground and surface water make it less conducive for agriculture or industry. It is geographically sandwiched between two regional heavyweights, the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and Iran, both vying for control of the region.

However, Qatar does have physical assets that can contribute to its strength and make it geopolitically important. Its leading natural resource is abundant natural gas: with vast swathes of gas fields, the Emirate has the third largest natural gas reserves after Russia and Iran. It is a leading liquified natural gas (LNG) exporter. In this way, it differs from other Gulf states, whose main source of income is oil and which do not have as much export capacity for natural gas. Qatar’s strategic location at the convergence between East and West, between Asia, Africa, and Europe, enables it to participate in international markets, expand the scope of its exports, and develop trade connections with other countries.

Qatar’s strategic location at the convergence between East and West, between Asia, Africa, and Europe, enables it to participate in international markets, expand the scope of its exports, and develop trade connections with other countries.

It has made the most of its geography through robust transportation infrastructure. Its range of ports, airports, and logistical centres has enabled it to enhance its trade links. It has a marine transport line through Hamad Port, a strategic window in maritime navigation and Qatar’s portal to global trade.

Additionally, its modern shipping fleet and LNG carriers have contributed to boosting the spread of its exports to markets across the world. Its ports, like Hamad Port and Ras Lafan Port, boast global quality infrastructure.

This, combined with its proximity to channels of global communication, has made it a focal point in trade, particularly energy and gas trade. Its national flag carrier, Qatar Airways, was rated the second-best airline in 2023 by Skytrax. Qatar Airways serves more than 150 key business and leisure destinations worldwide, with a fleet of over 200 aircraft.

Its infrastructure facilities have also helped it attract leading economies as strategic partners like China, the United States, and Europe, as well as foreign direct investment. Qatar Airways, in particular, has helped bring in more tourists and allowed the private sector to reach

SPOTLIGHT STORY

foreign markets through its extensive network that covers places like Africa, Central Asia, Europe, South Asia, the Middle East, North America, and South America.

With the Ukraine war having hiked energy prices and Europe turning away from Russia for its natural gas supplies, Qatar stands to become a major energy supplier for Europe.

It is worth pointing out that Qatar’s assets have enabled it to become financially independent as a small state and helped it maintain political autonomy vis a vis its larger neighbours. Financial independence was an important factor that enabled Qatar’s new ruling elite to adopt an independent foreign policy.

REGIONAL CHALLENGES

Qatar has faced its fair share of challenges with its regional brethren. In the most severe diplomatic crisis in the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) block, Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), and Egypt imposed a blockade on Qatar from 2017 to 2021. The GCC is a political and economic alliance of six Middle Eastern countries - Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, the UAE, Qatar, Bahrain, and Oman.

The embargo and severing of ties were the culmination of years of tensions building as Qatar’s neighbours were convinced that it was too independent and non-conforming in its foreign affairs. The 2011 Arab Spring uprisings had set several governments on edge, with GCC states alarmed by threats to dynastic rulers. Most GCC nations backed rulers like Egypt’s Hosni Mubarak, but Qatar tried to build ties with some opposition members, particularly groups connected to the Muslim Brotherhood, a controversial political Islamist group in the Arab world. Qatar’s neighbours were also irked by the positive depiction of the Arab Spring protests by Qatar-linked media, notably Al-Jazeera.

However, the three-and-a-half-year blockade did not have the desired effect, and Qatar seemed to emerge stronger. According to a Brookings article (January 19, 2021), it pushed Qatar to grow more self-reliant and

boosted its economy. Qatar also strengthened ties with countries like Turkey, another supporter of the Muslim Brotherhood.

It developed closer commercial ties with Iran, Saudi Arabia’s rival since Iran’s airspace became an essential channel for Qatar to access the rest of the world. Qatar was compelled to forge alternate supply routes, boost domestic production, and expand the capacity of its Hamad Sea Port as it grew new trade links. The boycott failed to accomplish its key aims, like pressuring the tiny nation into conformity or driving it away from Iran and Turkey. It came to an end with a GCC agreement, bringing about a Gulf reconciliation.

Since then, GCC rapprochement has proceeded steadily, through diplomatic and economic channels, including efforts to jointly enter into Free Trade Agreements (as a regional bloc) with other countries and groups.

QATAR’S REGIONAL ROLE

Qatar’s foreign policy from 1995 has looked to overcome structural limits such as its geographical position between two major regional powers with an ongoing fierce rivalry.

However, this had met resistance from the Saudi kingdom, which backed two coups to overthrow the government in 1996 and 2002 and opposed gas pipelines carrying Qatari gas to Kuwait and Bahrain. Such security challenges pushed Qatar’s government, led by Sheikh Hamad, to build alliances and soft-power tools such as conflict resolution, media and culture. For instance, Qatar launched Al Jazeera, the first Arab satellite news channel.

Qatar has played mediator and intervened in several regional crises, such as in Lebanon after Hezbollah invaded Beirut and between the Houthis and the Yemen government. More recently, it has played an active role in Ukraine, Sudan, Iran, Gaza, and Afghanistan between the U.S. and Taliban, most notably in 2020 towards the U.S. withdrawal of troops from Afghanistan.

04 SMALL BUT RESILIENT

While other Middle Eastern countries aspire to don the mediator’s hat, like Egypt and Oman, Qatar’s image as the regional conflict resolver seems most widely accepted. Its ties with controversial outfits like the Taliban and Hamas enable it to broker tense situations involving such actors.

This role helps it maintain ties with the international community and protect itself from unwanted interventions from neighbours like Saudi Arabia, Egypt, and the United Arab Emirates.

Doha’s efforts to minimize its risk in the tumultuous region seem to have paid off. For instance, when Iran retaliated against the U.S. for killing its general Qasem Soleimani, it targeted U.S. bases in Saudi Arabia, Iraq and Jordan, but not Qatar. This is despite Qatar’s two major U.S. bases and the fact that they would be easy to hit.

Qatar’s negotiator role in the Gaza crisis has made headlines and released hostages as well as aid to Gaza. This is enabled by its contrasting connections with Western powers like the U.S. on the one hand and Islamist groups on the other hand. Qatar’s ties with Hamas and Iran have helped it gain a prominent position with global powers that is often described as indispensable. However, Qatar is also aware of the bad press it’s getting in the West for its ties with Hamas, which has led it to tread more carefully.

Qatar has deftly managed its relations with the U.S. and China, taking advantage of both big powers. It created waves when it opened a Chinese Renminbi clearing facility in 2015, and in 2022, amidst the Ukraine war, it sealed a lucrative contract with China for the supply of LNG.

QATAR AND INDIA

India and Qatar established formal diplomatic ties in 1973, and since then, their bilateral relationship has expanded to cover a range of aspects, including defence, counterterrorism, and energy trade. A significant diplomatic visit in 2015 featured the signing of five MoUs during the Emir’s visit to India.

Qatar’s exports to India have been mainly in the hydrocarbon sector, including LNG, LPG, petrochemicals, chemicals, plastics, and aluminium articles. Qatar is India’s largest LNG supplier, accounting for 50% of India’s LNG imports in 2023. QatarEnergy and India’s largest LNG importer, Petronet LNG, recently signed a long-term mega deal as India increases its use of the fuel to reduce its emissions.

The bal ance of trade remains sig nificantly in Qatar’s favour, although In dia’s exports to

Qatar have sizably grown in the last few years. India is among the top three export destinations for Qatari goods and is also one of the leading exporters to Qatar. Its exports to Qatar cover a range of products like copper, iron and steel articles, cereals, vegetables, machinery, electronics, and textiles.

The Indian diaspora in Qatar makes up one of its largest expatriate communities. This makes India-Qatar ties all the more important and adds a sociocultural element to their relationship. For Delhi, the condition of Indian expatriate workers in Qatar continues to be a priority, with labour mistreatment being a prevalent issue.

The amicable settlement of the case of seven ex-Indian Navy officers sentenced to death for alleged espionage in Qatar has done a great deal in strengthening relations between the two countries.

Going forward, the two nations are likely to strengthen LNG trade as India looks to increase the natural gas component of its energy mix in a bid to turn to cleaner fuels. They would also do well to expand renewable energy cooperation, as Qatar looks to diversify its exports to keep up with the green energy transition, and both countries are looking to diversify their energy sources.

The two nations could also cooperate in the area of education. Western universities in Qatar are an attractive option for Indian students looking to access quality education abroad without the high costs associated with the West.

Indian students could also offer a potential talent pool for employers in Qatar. The two nations could engage in human resources cooperation through training programs and skill-building. On the other hand, perceived anti-Muslim sentiment in India could prove to be an obstacle to ties between India and Qatar.

Assessment

Qatar emerged from the Gulf crisis as a significant player that navigated regional pressure without compromising its sovereignty and independent foreign policy. By maintaining and expanding ties with diverse states and non-state actors, it has created a niche for itself as a legitimate regional and global mediator.

In the context of the Gaza war, the Red Sea crisis and heightened regional tensions, Qatar stands to play a useful role in offering a communications channel with actors like Iran and its proxies Hamas, Hizballah and the Houthis to broker a potential peace agreement.

India and Qatar stand to benefit from energy cooperation through trade, investment, technology exchange, possible joint endeavours, and cooperation in areas like education and human resources.

05 SMALL BUT RESILIENT

PAKISTAN: PDM 2.0 PROSPECTS

The coalition may have to make tough economic and foreign policy decisions even while its standing is in question.

SYNERGIA FOUNDATION

RESEARCH TEAM

The Pakistan Democratic Movement (PDM), an alliance of more than a dozen parties, ousted Imran Khan in 2022 to form the Government.

A similar coalition, referred to as PDM 2.0, was recently formed to sidestep Mr Khan’s party and form a government in Pakistan.

Yet not only are its legitimacy and longevity in question, but it also faces sizable challenges on the economic, security, and foreign policy fronts.

ELECTIONS A SOAP DRAMA

In a surprise result, jailed former Prime Minister Imran Khan’s party won the most seats in Pakistan’s parliamentary elections earlier this year.

Mr Khan’s Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (P.T.I.) gained more seats than the military-backed Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz (P.M.L.N.) led by the three-time former prime minister, Nawaz Sharif.

The surprise PTI victory upturned the military’s expectation of an easy win. Not only was it preceded by generals jailing Mr. Khan and candidates allied with his party, but it also came amidst accusations that the incumbent military-backed Government had engaged in rigging.

Pakistan is in a poly crisis with its volatile economy, in the midst of a multi-year crisis, topping the list. As per the Economist, Pakistan’s GDP shrank slightly in 2023 amid high debt, a balanceof-payments crisis and inflation that peaked at nearly 40 per cent before falling back to its current rate of 23 per cent. With wildly fluctuating foreign reserves, Pakistan is burdened with an external debt of $ 30 billion.

However, the tables soon turned: since the PTI fell short of a majority, the Pakistan People’s Party (PPP) reached a power-sharing consensus with the PML-N to stitch together a coalition government.

Mr. Khan, a populist leader, was ousted from power in 2022 through a no-confidence vote, convicted for multiple crimes, and banned from contesting the elections. The previous PMLN-led coalition or PDM that replaced him was unpopular and came under flak for being unable to address the economic crisis and record-high inflation.

In PDM 2.0, Shahbaz Sharif, brother of Nawaz Sharif, was appointed prime minister of Pakistan. His Government faces a stagnant economy grappling with double-digit inflation and steep debt.

NEIGHBOURHOOD

WILL THE GOVERNMENT LAST?

Despite its military backing, the Government is already on a shaky footing, given Imran Khan’s popularity and allegations of election irregularities. However, political longevity aside, the new Government has urgent economic issues on its plate.

Mr Imran Khan has refused to be cowed down. In fact, the surprisingly good performance of his dismantled party, the PTI has encouraged him to wage a movement to “recover the peoples’ mandate that was stolen from him.” They intend to take recourse not only to legal actions but also gradually ratchet up public pressure through social media-generated street protests, a skill at which the PTI excels.

The country can expect more political turmoil in the coming months, especially as Pakistan goes for a fresh deal with the IMF and is compelled to enforce its directives at the cost of the common man’s economic health, already under severe duress.

There has been considerable clamour internationally on the fairness of elections in Pakistan. Expatriate Pakistanis in the U.S. and Europe have been spearheading the cause of Mr Imran Khan and have succeeded in getting considerable traction.

This has caused a dilemma for Army Chief General Munir, who calibrates the ebb and flow of political activities in the country from his GHQ in Rawalpindi.

It will be a hard sell to attract investments from discerning foreign investors if the most popular political leader remains incarcerated on charges that may not stand proper legal scrutiny in any independent court of law. Also, a total lack of political consensus between the opposition and the ruling dispensation will impede the economic agenda’s rollout.

ECONOMY IS THE KEY

Pakistan is in a poly crisis with its volatile economy, in the midst of a multi-year crisis, topping the list. As per the Economist, Pakistan’s GDP shrank slightly in 2023 amid high debt, a balance-of-payments crisis and inflation that peaked at nearly 40 per cent before falling back to its current rate of 23 per cent. With wildly fluctuating foreign reserves, Pakistan is burdened with an external debt of $ 30 billion.

During the 18 months of PDM 01, Mr Sharif managed to avoid default by the skin of his teeth when, after much haggling, the IMF released a $3bn stand-by emergency loan. With the robust backing of the Army Chief, the military-appointed caretaker government that followed cracked down on illegal foreign market trade, smuggling and black marketing of commodities to deliver a primary fiscal surplus. However, what was not so openly spoken of was that this was at the cost of imports (which affected manufacturing), and there was little or no progress in deeper reforms like privatising resource guzzling state enterprises and the shrinking tax base. Clearly, it has been left to the current dispensation to deal with these hot potatoes.

Pakistan has no option but to knock at the doors of the IMF for its 25th bailout, a task for which Mr Sharif has selected the Wharton educated Muhammad Aurangzeb, the suave CEO of Habib Bank. There is little doubt that the IMF package will come through, albeit with more arm twisting, as the international community is aware of the consequences if a nuclear armed nation is allowed to fail.

The Army-steered Special Investment Facilitation Council had been desperately trying to muster investments from Gulf nations. While the Army’s ability to convince Gulf investors to put their money into Pakistan’s faltering economy has generated much optimism,

07 PAKISTAN: PDM 2.0 PROSPECTS

dollar flow has yet to flow. However, during a recent visit to Saudi Arabia, the Crown Prince assured the prime minister of an early $6 billion investment.

It is worth pointing out that external remittances, Pakistan’s largest source of foreign reserves, are falling. Pakistanis in Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emir ates (UAE) are the top remitters, but they have held back in the face of political uncertainty, a fraught elec tion, and economic fragility.

SECURITY

It is suffice to say the picture on the internal security front looks extremely grim. The recent killing of Chinese work ers, the frequent attacks on security forc es and CPEC assets and the faceoff with the Taliban regime in Kabul have thrown questions on the ability of state security organs to protect the investments of for eign businesses. This has to be tackled as a priority before even staunch friends like Chi na and the Gulf nations risk their billions.

In the West, Pakistan grapples with tense borders with Taliban-led Afghanistan. The outlawed Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP), which Pakistan accuses of numerous militant attacks on its soil, continues to hide out in Afghanistan. A recalcitrant Taliban regime refuses to rein in the TTP.

The situation has got worse as Pakistan has repatriated nearly half a million Afghans back to their country and is gearing up to despatch the remaining one million or so in the coming few months. Most Pakistani security analysts are of the view that the much-vaunted ‘strategic depth’ philosophy for Afghanistan advocated by the Pakistan military for decades lies in tatters.

GEOPOLITICAL LANDSCAPE

On the diplomatic front, the PDM 2.0 has to manage tense ties with neighbours and mend fraying relations with its longtime ally, the United States (US). Pakistan’s close ties with China amidst significant U.S.-China tensions and U.S.-India strategic ties have contributed to this. Pakistan’s influential military leaders, who have hitherto steered its foreign policy, have expressed an interest to patch up with the U.S. However, Mr Sharif will have to avoid getting mired in Mr Khan’s campaigning allegation that the opposition (and the Army) colluded with the U.S. to oust him.

While China, a major ally, has substantially invested in Pakistan through the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), the corridor’s viability is uncertain as it faces hurdles like security risks and delays. The recent IED attack killing five Chinese nationals created serious rifts between the two “Iron Brothers’ and the prime minister had to rush to the Chinese Embassy to cool tempers. The new Government will have to address Chinese concerns to sustain the project as China becomes increasingly reluctant and cautious with its fi-

nancial overtures. Closer home, ties with India strained further under Mr Khan’s Government. Despite pressure from top military leaders who have opposed normalising ties with India, Nawaz Sharif has historically been more conciliatory towards India and appeared to enjoy a measure of rapport with Mr Modi in his last tenure. It remains to be seen whether his brother, Mr Sharif, will follow suit. However, the new Government has indicated intentions to reopen trade with India, which was suspended in 2019.

The Daily Dawn of 24 January opines that in its relations with India, the incoming Government is expected to focus on diplomatic engagement, prioritising economic stability over political tensions.

The Government is likely to open doors for regional trade and investment with India. This may involve backchannel diplomacy and dialogue at various levels, aiming to address critical issues like the Kashmir dispute while avoiding escalatory actions. Abu Dhabi and Riyadh are advocating for a paradigm shift in South Asian politics.

They are encouraging Pakistan to explore avenues for normalisation with India, urging a move away from military standoffs and a step back from conflict in general. This is to be expected from investors with Big Bucks investments lined up to safeguard their funds.

Assessment

The new Government will have to take economically and diplomatically uncomfortable measures to steer Pakistan through troubled waters. If China, the only reliable lifeline remaining, follows the route of Western investors and turns away from the unstable Pakistani regime due to recurrent security lapses, a dark economic abyss will confront the Pakistani economy.

Economically, fiscal discipline and other stringent reforms may be the only way to secure another lease of IMF funding and keep the economy afloat. Of course, the common person on the street will suffer, but this has been the case in most nations of the Global South.

Diplomatically, overtures like repairing ties with the U.S. and reopening trade ties with India may be key steps in PDM 2.0’s foreign policy action. However, will India, now in the driving seat, respond positively, or will it allow nuclear-armed Pakistan to slide into economic ruination? This is a decision that New Delhi may have to take sooner rather than later.

08 PAKISTAN: PDM 2.0 PROSPECTS

Critical Challenges: In my view, the three critical challenges for the new Government are in the domains of politics, internal security and foreign affairs. As far as the economy goes, given our accord with the IMF, it will be guided towards stabilisation and, hopefully, revival together with support from IMF and our friends like China, Saudi Arabia, UAE plus USA and EU, a process on which we are already embarked. In politics, especially after the flawed elections, there’s a need for a healing touch: releasing all political prisoners and bidding goodbye to the politics of vendetta, vengeance and victimisation. In internal security, crafting an effective counter-terror strategy, given the recurring terror attacks in Pakistan’s provinces bordering Afghanistan & Iran. And there’s a need for a Regional Reset in relations with our neighbours.

Political Landscape: Today, Imran Khan is Pakistan’s most popular politician, and his Party, although officially denied its trademark symbol of the Cricket Bat in the February polls, received 37 per cent of the popular vote, with PML-N getting 23 per cent and PPP 13 per cent. In any likely election, PTI willer. In Pakistan, -

EXPERT COMMENT

It seems the government’s top priority is to clinch another IMF “bailout”, which should help inject some stability into the economic system.

However, it remains to be seen if IMF conditionalities would be politically sustainable. In parallel, the Government is also working to get more and swift investments from China and Gulf countries.

Pakistan is unfortunately caught in a proverbial vicious economic circle, and to address massive economic chal-

ten debarred, exiled or imprisoned, but their political future is not determined by administrative or judicial diktat but by popular will. Pakistan is undergoing three transitions simultaneously: ( a) with 65 per cent of Pakistanis under 35, a youthful leadership, new generation, is already taking over two of the three major parties (Bilawal in PPP, 36, & Maryam Nawaz, 49, in PML-N); (b) the two major parties that dominated the national political landscape for the last 30 plus years have been overtaken, for the first time, by Imran Khan’s PTI; (c) traditional politics of clans, candidates & constituencies have been overtaken by popular mobilisation based on issues disseminated via IT/Social Media platforms, a more modern, creative expression of Pakistani-style populism in which youth, women, the ‘silent’ middle class & the Diaspora are key pillars!

Prospects for Indo-Pak Relations: I expect forward movement after the Indian elections, especially on low hanging fruit like Cricket, Culture, & Commerce, plus the resumption of Ambassadorial level relations, which will provide an enabling environment for a better Pakistan-India rapport. Post-polls, Mr Modi would want to follow the Vajpayee path towards Pakistan for several reasons: because of India being a loner or standing out alone on SAARC, fear of a China-Pakistan gang-up, pressure from the U.S. to ‘behave’ better with Pakistan, and no longer guided by domestic political considerations of weakening his Hindutva base.

SENATOR MUSHAHID HUSSAIN SAYED

Member of the Senate of Pakistan and Information Secretary of the Pakistan Muslim League.

lenges, it needs a stable and predictable political environment. Unfortunately, I don’t see any well-defined economic strategy. The weak coalition government will continue to experiment on different fronts.

I think there is a possibility of restoring full diplomatic relations and bilateral trade once the new Government is in place in New Delhi.

AMBASSADOR ABDUL BASIT

Ambassador to Germany from 2012 to 2014 and High Commissioner to India from 2014 to 2017.

09 PAKISTAN: PDM 2.0 PROSPECTS

EXPERT COMMENT

Mr Ihsan Ghani is a former naval officer and a retired Inspector General of Police. He has also been Chief Security Officer to the Prime Minister of Pakistan, in the Intelligence Bureau and as Minister Coord at PHC London. He also served as provincial Inspector General of Police, DG National Police Bureau, National Coordinator, National Counter Terrorism Authority and DG IB from where he retired in August 2018.

Synergia: How is the new government planning to tackle the challenges, especially those posed by the economy?

Mr Ihsan Ghani: For many decades, Pakistan’s governance has remained militarised. While this is dangerous, more dangerous is that it has resulted in the “civilianisation” of the military. The military never had as prominent a role in the country’s economic affairs, not even during direct military rules as it has now. The aim of this strategy was that while the economists would make policies, the military would guarantee the implementation and sustainability of these policies. While it sounds good on paper, on the ground, the political leadership, knowingly or otherwise, feel absolved of the

responsibility if the economy doesn’t pick up as envisaged. In my little knowledge, “economy is too serious a business to be left to the Generals”.

Synergia: What is the prognosis for the India-Pakistan relationship - in the next five years?

Mr Ihsan Ghani: Whereas political governments, with a few exceptions, have favoured cordial relations with all their neighbours, especially where trade is concerned, the overbearing military for the fear that it will not be able to sell its best-selling commodity that is fear in case the fear of India is gone, and thus have always torpedoed such efforts. Now that the military has committed to shoulder the responsibility of economic revival, a window of cooperation can be created. The effort could be civilian-led, supported by the military for longterm gains.

EXPERT COMMENT

Very few governments in Pakistan have completed their full five-year tenure. Usually, fast-moving developments overtake the usefulness of governments to the military in Pakistan, leading to changes or the overthrow of governments. In all probability, this same fate will befall the current Shahbaz Sharif government.

Imran Khan continues to remain a force in Pakistan’s politics. He could make a

not go together - don’t expect any change in India’s handling of Pakistan or bilateral India - Pakistan relations.

WHAT IS THE MAIN TAKEAWAY FOR US IN INDIA?

Given India’s position on dealing with terrorism and -

It was the Pakistan army or what is often referred to as the Pakistan establishment, which did not want any kind of peace breaking out between the two neighbours. The reason for that was simple: the very pre-eminence, influence in domestic affairs, authority and legitimacy of the Pakistan army would be called into question if there was peace. Therefore, efforts by previous Pakistan prime ministers such as Benazir Bhutto, Nawaz Sharif and Asif Ali Zardari were always shot down.

GAUTAM BAMBAWALE,

Former Indian Ambassador to China and Bhutan, Former Indian High Commissioner to Pakistan

10 PAKISTAN: PDM 2.0 PROSPECTS

Former Naval Officer and a Retired Inspector General of Police

EXPERT COMMENT

MR IHSAN GHANI

A creation of the army, the new government will last till it enjoys their trust. However, it will be a weak government subject to pulls and pressures from three sources: the army; the coalition allies, especially PPP, which supports the government from outside; and PML(N) leader Nawaz Sharif, who, though not in the government will continue to exercise considerable influence on governance issues. Being weak, the government will not be able to handle effectively Pakistan’s myriad intractable problems.

It will, in particular, depend on the army’s support to implement several unpopular measures necessary to stabilise the economy.

Though his immediate future seems bleak because of the bad blood between him and the army chief Asim Munir, Imran Khan and his party cannot be written off for all times to come. PTI received considerable public support in the election despite all the machinations of the army to put it down. It has managed to retain power in Khy-

ber-Pakhtunkhwa. Therefore, both Imran Khan and PTI will remain a political force to reckon with. A positive movement in India-Pakistan relations will be contingent upon two factors: (a) the extent of attention and political capital the new Pakistan government can devote to the India relationship while attending to several internal problems. (b) the army’s attitude under Asim Munir. His thinking on the subject is still not clear.

The new Foreign Minister, Ishaq Dar, who is close to Nawaz Sharif, has spoken of a review of the suspension of trade with India since 2019. A large segment of trade and industry supports the move.

However, it has powerful opponents in the form of hardliners in Pakistan who oppose any normalisation with India, but more importantly, sectors like automobiles and pharmaceuticals that make fat profits in the absence of imports from India. Therefore, we will have to wait and see if the above announcement results in anything positive.

In any case, any positive movement in the bilateral relationship will have to await the conclusion of Indian elections and the formation of a new government.

AMB SHARAT SABHARWAL

Former Indian Ambassador to Pakistan.

11 PAKISTAN: PDM 2.0 PROSPECTS

COMMENT

EXPERT

WARS OF ATTRITION AND RESILIENCE

Weaker powers and non-state actors can manipulate the wide spectrum of new-age warfare to their advantage; Ukraine and Gaza reflect this paradox.

SYNERGIA FOUNDATION

RESEARCH TEAM

Wars have always been about strategy, tactics, and technology, which holds true even now. However, new-age conflicts seem to be forging some novel and fascinating ways of waging war. For instance, asymmetric parties to a conflict are using disruptive technologies to prevent the stronger power from attaining its political and military objectives.

With weaker powers privileging quantity over quality, or `cheap mass` as Kelly Greico, a Washington-based analyst, argues, we can well imagine what future wars might look like.

Wars driven by first-person view drones, low-tech missiles and garage-assembled rockets, when used in large numbers, demonstrate how a weaker party to a conflict can blunt a sophisticated force with expensive platforms on the battlefield.

Whether these disruptive capabilities can cause prohibitive attrition to a stronger power in asymmetrical conflicts of long or indeterminate duration remains the moot question. And what impact these new-age wars might have on future force structures, designs, and war-fighting concepts are issues to ponder.

These and many other new war-fighting trends and technologies are legitimate questions on the evolving character of war.

From the war-fighting trends observed so far in Ukraine and Gaza, it seems prohibitive attrition could be a way to prevent or deter stronger powers from attaining their military objectives. Hopefully, adequate evidence exists to conclude that weaker powers can inflict prohibitive battlefield losses through innovative military action

RETURN OF ATTRITIVE WARS

Wars in Israel and Ukraine signal the return of attritive wars. In fact, they symbolize the new-age wars. For Ukrainians, the Hamas October 7 assault on Israeli civilians bears stark similarities to Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine last year. Earlier, Ukraine suffered the wrath of Russian strikes targeting towns and cities and the local infrastructure, leading to mass displacement and suffering. Israel is now fighting a wily adversary in dense terrestrial and subterranean environments. Possibly a war far more difficult than any other conflict in recent history, be it the tunnels of the Vietnam War or battles in Mosul, Aleppo or Fallujah.

Recent events in Gaza and Ukraine also remind us of what happens when wars turn brutal. Both wars demonstrate how the populace becomes victims of wars of attrition, and when laws of armed conflict take a backseat, vengeance rules action, and violence escalates to horrific levels. As these new-age wars of attri-

SECURITY

tion play out, collateral damage on population centres, hospitals, and schools is internalized as a normative outcome of the war. As the real fight ensues in Ukraine and Gaza and the wars evolve, the warring side narratives in the form of lies, mistruths and accusations only grow, obscuring the real purpose and human cost of the war.

From the war-fighting trends observed so far in Ukraine and Gaza, it seems prohibitive attrition could be a way to prevent or deter stronger powers from attaining their military objectives. Hopefully, adequate evidence exists to conclude that weaker powers can inflict prohibitive battlefield losses through innovative military action that compels a stronger military to miscalculate or re-think and that such ideas lead us to find new and resilient ways of waging wars.

THREE CONTEXTS

Three aspects assume importance in asymmetrical contexts: resilience in war, innovativeness in war, and the ability of a weaker power to cause prohibitive attrition in war.

Resilience in War: Russia took Ukraine by surprise in February 2022 and, as a stronger military power, was expected to liberate Kyiv in quick time. A weaker Ukraine, however, stalled the Russian offensive with fewer and borrowed resources at hand. Whether such outcomes are a simple function of superior men, machines, or material, which Ukraine did not possess at the beginning, and Russia did, or it has more to do with a state’s will to fight, its societal resilience and innovativeness on the battlefield is a question that seeks an answer.

As a weaker party to the conflict, Ukraine has successfully leveraged the intangible attributes of state resilience to match up with Russia. Everything else,

including political and military leadership, doctrines, organizational structure, and technology, comes next. In fact, Ukraine’s ability to community-ise its war effort to produce war outcomes, which its stronger opponent could not deliver, is a lesson on conflicts between asymmetrical powers.

Innovativeness in War: History tells us that technology favours the strong rather than the weaker side in battle. This is fast changing, with weaker parties to a conflict leveraging inferior technology in more innovative ways. Ukraine’s use of borrowed military equipment and innovative exploitation of low-cost disruptive technologies highlights this point.

While the West has lent a major part of this war effort, Ukraine’s ability to train and absorb these borrowed technologies on the run has been remarkable. Killer drones pioneered in Ukraine are reshaping the balance between humans and technology in war.

The fact that a war-fighting effort can be `corporatized` through your allies and partners, in case one lacks the military capacity, is a new learning from this war. The horrific Hamas strike in southern Israel is yet another example.

A banned and reckless outfit lacking material resources to make war with a powerful state has delivered the most unthinkable outcomes. Employing cheap and simple-to-use technology, Hamas squarely used a technology-laden approach to secure the Israeli state. Both wars highlight that military boots matter more than the machine in war and that innovative minds with `cheap mass` can deliver disproportionate outcomes in asymmetrical conflicts. Innovative use of `cheap mass` is achieving near-mythical status on the battlefield.

Prohibitive Attrition in War: Brutality comes at a great human cost, and both wars demonstrate this fact.

13 WARS OF ATTRITION AND RESILIENCE

A favoured strategy is to rely on prohibitive attrition to drive decisive outcomes in war. At the tactical level, wars of attrition are about bitter battles of control over contested territory and urban rubble, while at the strategic level, these are about shaping perceptions, mistruths or half-truths, and about who is the aggressor or the victim. Ukraine has done well in capitalizing on this idea and keeping Russia embroiled. The more Russia tries to achieve a decisive victory, the more successful the Ukrainians have been in inflicting heavy losses on the Russians.

While Russia might possess the logistical stamina for a long war, the prohibitive costs imposed by Ukraine have been impactful. Elsewhere, Hamas leveraged the tunnel labyrinth to impose caution and attrition on the Israel Defense Forces (IDF).

Despite its recent successes in degrading Hamas in Gaza, a long and risky battle confronts the IDF. An urban landscape compounds the effect of attritive battles, and how the IDF might maintain operational momentum and achieve its war objectives, including the repatriation of the hostages, remains to be seen. As expected, Hamas’s allies have jumped in to open new fronts and are trying hard to overwhelm Israel’s capacity to re-generate reserves and military wherewithal.

That would be a big challenge, but given its reputation for innovation and fighting against all odds, we can expect IDF to come out undefeated in this war.

SOME LESSONS

Clarity in Knowing Your Capacity: Wars are often started, fought, and progressed over various assumptions, some with misplaced optimism. Policy-makers sometimes assume that diplomacy can deliver on national security needs without developing its war-fighting capacities.

Elsewhere, they assume that the resident military power can deliver on any politico-military objectives that a state desires to achieve. Both policy positions are fraught with biases and intolerable strategic risks, which can result in a mistaken view of a state’s real diplomatic influence or war-waging capabilities. Here lies the importance and significance of building state resilience and clarity in national security concepts, policies, guidance, structures and deliverables.

Sustainability and Endurance: War-fighting resilience’s real intent and purpose is to develop the capacity to sustain higher intensity of conflicts and endurance to impose prohibitive losses to the aggressor, particularly in asymmetrical conflicts.

Resilience in such conflicts requires a state to systematically convert its limited or inferior economic, industrial, financial and technological resources into `attritive` war-fighting capabilities within a defined period.

In other words, the ability of the state to `innovatively` convert its assets and industry to sustain conflicts of long or indeterminate duration and at levels higher than what threats the adversary can bring to bear upon the state.

LESSONS FOR INDIA

For India, national security resilience could provide the state with the framework and ability to field an indigenous and sustainable deterrent capability for asymmetrical conflicts. India’s military challenge is to develop resilient war-fighting requirements to achieve a stalemate in a possible asymmetrical conflict with China.

From a policy perspective, the key question is, how can the North’s threat be contained or attrited?

What are the main lessons from the ongoing conflicts in Ukraine and Gaza, and how and what war-fighting capabilities are deliverable through innovative or new technologies and disruptive methods to cause prohibitive attrition that could stall a stronger power?

What could be the force design for causing prohibitive attrition, and can an `attritive` military action possibly be developed as a preferred operation of war for our northern borders?

For any war-fighting capabilities to build and take shape, the policy lines of effort must first be doctrinal rather than structural. More doctrinal than structural. But then, the Indian military establishment is caught up in an endless theatre-isation debate. Simply put, this debate serves a narrow structural requirement, not the doctrinal purpose of India’s attritive war-fighting capabilities. This requires both correction and pragmatism.

14 WARS OF ATTRITION AND RESILIENCE

INDIA AND THE INDO-PACIFIC

Why the Indo-Pacific matters to the world and India.

Rear Admiral Monty Khanna AVSM, NM, (Retd) is the former Deputy NSCS in New Delhi as the Assistant Military Adviser and Strategic Advisor at Synergia Foundation.

Assigning names to vast expanses of the globe is primarily a function of geography. Our continents and oceans have been named with such contiguity in mind. The sole exception to this rule is the bifurcation of the vast Eurasian landmass into the continents of Asia and Europe. Linkages between these distinct continents and oceans have existed for millennia for reasons varying from trade to migration, sometimes voluntary and more often than not forced, as was done during periods of slavery and indentured labour.

The geography of the Indo-Pacific is now playing an increasingly critical role in geopolitics. The region and its resources house a wealth of geo-strategic challenges for maritime security forces. The Indian Ocean, the third largest , and relatively peaceful ocean complements the Pacific, the largest, and most contested ocean. Together, they host two of every three island nations and seven of the ten largest continental nations. The maritime orientation of the region is highly interconnected.

RISE OF A REGION

Over the last century, as globalisation gathered steam, these inter-linkages have become even more pronounced and have extended from the physical to the virtual domain. Supply chains in both domains have be-

Insofar as India is concerned, we too have welcomed the Indo-Pacific concept, and the terminology has been mainstreamed through numerous policy statements made by the Ministry of External Affairs. It has been seen as a vehicle in consonance with our Act East Policy that could be leveraged to enhance our strategic relations with West Asia and ASEAN.

come increasingly intertwined to leverage the comparative advantage that even distant nations have had to offer. This has resulted in a steady increase in the purchasing power for most goods and services, thereby increasing affordability and consumption, which in turn has led to an exponential improvement in quality of life.

Enhanced trade dependencies, particularly in a competitive environment, have given way to enhanced strategic interests in the Indo-Pacific region. As some nations have been more efficient than others in creating the necessary environment to leverage their comparative advantages for economic benefit, trade has also resulted in power shifts, the most notable being China’s phenomenal rise over the last four and a half decades.

The re-industrialisation of Japan preceded China’s rise post World War II. This was followed by the concurrent rise of the Asian tigers, i.e., Taiwan, South Korea, Hong Kong and Singapore. Finally, the accelerated growth of India, as well as the rest of Southeast Asia,

SECURITY

has resulted in the economic fulcrum of the world having perceptibly shifted eastwards.

Given the stakes involved, challenges to global hegemony are invariably accompanied by pushback by the established power. The U.S., therefore, has resisted China’s rise in multiple dimensions, including the strategic, economic, and technological arenas.

TWO OCEANS ONE STRATEGY

Insofar as the strategic dimension is concerned, one tool that the U.S. has used is the articulation of the Indo-Pacific concept, wherein the Indian and Pacific oceans and their littoral nations are construed to be conjoined into a single geopolitical construct.

From a U.S. perspective, such a step has several perceived advantages. It serves as a vehicle for enhanced military, economic, and strategic ties between the U.S. and Indian Ocean littoral nations, the key being India. It encourages stronger bonds between the U.S. Asian allies and Indian Ocean Region countries. It provides a fillip to the QUAD and similar security constructs in the region. It serves as a counterweight to the Chinese Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and its subsequent avatars, these being the Global Development Initiative (GDI), Global Security Initiative (GSI) and Global Cultural Initiative (GCI). It demonstrates the U.S.’s continued commitment to the region and serves as an instrument for reassuring smaller nations which have occasionally shown tendencies to hedge geopolitical risks by forging closer ties with China. In a way, it has the potential to be a key building block in an effort towards containing the rise of China and preserving the current geopolitical order.

From a security perspective, the shift has been relatively easy for the U.S. as the erstwhile Pacific Com-

mand (PACCOM) ‘s Area of Responsibility (AOR) always included a sizeable part of the Indian Ocean. Its new name, the Indo-Pacific Command (INDOPACCOM), just provides greater visibility to its tasking in the IOR, a responsibility it was already entrusted with.

Countries in the region have reacted differently to the salience given to the Indo-Pacific construct. China has clearly identified it as a tool for containment. Russia sees it as a means of isolating them, as expressed in no uncertain terms by the Russian foreign minister, Mr. Sergei Lavrov, during the 2020 Raisina Dialogue.

Australia, a U.S. ally whose landmass washes the shores of both oceans, has not surprisingly embraced the Indo-Pacific. It serves their strategic interests well, for while their security interests lie with the U.S., their economic interests are oriented towards Asia. Seeing the two oceanic regions as a unified strategic construct is something they have been doing for decades. Japan, another U.S. ally, has also found favour with the concept.

Their motivations, however, appear to be more China-centric. Given their testy relations coupled with proximity to China, any attempt to broad-base the pushback against the rise of China is welcome. The enthusiasm from most Southeast Asian nations has been more tepid. The region has walked a fine line over the past decade, balancing a rising and more assertive China with the existing pre-eminent power, the U.S. They would not like to be drawn into either choosing sides or, worse, into a potential conflict, should a situation so develop.

THE INDIAN DILEMMA

Insofar as India is concerned, we too have welcomed the Indo-Pacific concept, and the terminology has been

16 INDIA AND THE INDO-PACIFIC

mainstreamed through numerous policy statements made by the Ministry of External Affairs. It has been seen as a vehicle in consonance with our Act East Policy that could be leveraged to enhance our strategic relations with West Asia and ASEAN.

It reemphasises freedom of navigation and the preservation of a rules-based order at sea in accordance with the UNCLOS. Given our unsettled borders and China’s adoption of a more belligerent stance in disputed regions, it serves as a tool for messaging and moderating China’s behaviour.

It facilitates enhanced interoperability with like-minded powers, thereby allowing the rapid coming together of security forces in the event of a contingency while remaining outside an alliance structure.

That being said, we need to remain conscious that the Western Pacific has complex geopolitical disputes related to Taiwan, the Senkaku, Paracel and Spratley islands, and the now re-articulated Ten Dash Line. Each of these has the potential to rapidly transition into a conflict that we would be wise to be highly calibrated in our involvement.

We have a large trading relationship with China and share an over 3,000 km long border that needs to be managed deftly, both militarily as well as politically, to avoid unnecessary escalation that will be detrimental to both nations.

We must also assess how our long-enduring strategic relationship with Russia will be impacted if we are seen to be increasingly aligned with nations inimical to their security interests. Further, our responsibilities in the IOR are large, and we do not have the necessary military wherewithal to execute extended operations in

the Pacific on a scale that could influence a potential conflict. We, therefore, need to temper our rhetoric on the Indo-Pacific in keeping with ground realities and our larger strategic interests. Thus, while we encourage conceptual articulation about the Indo-Pacific, we need to remain conscious that our security interests fundamentally lie in the IOR and its littoral nations.

Assessment

History records the Indo-Pacific maritime domain as crucial for establishing new and emerging powers and shaping regional dynamics. With great powers influencing the larger security architecture of the region, strategic competition is at its highest. India cannot afford to be left out of the shifting power dynamics that characterise the region.

India is fast emerging as a net security provider in the region, which will come at a considerable cost in terms of investment in the Indian Navy, a capital-intensive service. The opportunity cost of doing so may come under scrutiny as India’s principal security threats lie first on land and then at sea, from a realistic perspective.

Nations within the geography have their navies and maritime security agencies working towards keeping the region secure. No single nation, not even the U.S., can dominate the vast waters of the Indo-Pacific. Forging collaborative frameworks is an important element of any commitment to the region.

17 INDIA AND THE INDO-PACIFIC

THE US’ INDO-PACIFIC STRATEGY

The term first appeared in academic use in oceanography and geopolitics. Scholarship has shown that the “Indo-Pacific” concept circulated in Weimar Germany and spread to interwar Japan. German political oceanographers envisioned an “Indo-Pacific” comprising anti-colonial India and republican China as German allies against “Euro-America”.

Since the late 2010s, the term “Indo-Pacific” has been increasingly used in geopolitical discourse. It also has a “symbiotic link” with the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue, or “Quad”, an informal grouping between Australia, Japan, India, and the United States.

It has been argued that the concept may lead to a change in popular “mental maps” of how the world is understood in strategic terms. Remarking on overlap-

ping older terms for the region, the political scientist Amitav Acharya stated that as a concept, “’Asia’ was built by nationalists, ‘Asia-Pacific’ by economists, ‘East Asia’ by culturalists, and ‘Indo-Pacific’ by strategists’”.

In its widest sense, the term geopolitically covers all nations and islands surrounding either the Indian Ocean or the Pacific Ocean, encompassing mainland African and Asian nations who border these oceans, such as India and South Africa; Indian Ocean territories, such as the Kerguelen Islands and Seychelles; the Malay Archipelago (which is within the bounds of both the Indian Ocean and the Pacific); Japan, Russia and other Far East nations bordering the Pacific; Australia and all the Pacific Islands east of them, as well as Pacific nations of the Americas such as Canada or Mexico. ASEAN countries (defined as those in Southeast Asia and the Malay Archipelago) are considered to be geographically at the centre of the political Indo-Pacific.

The term Indo-Pacific is ambiguous and amorphous, with each member of the so-called Quad having its own understanding of the strategic space.

The current coinage has been main-streamed by the USA: as Rear Admiral Khanna has observed, “Insofar as the strategic dimension of its contestation with China is concerned, one tool that the U.S. has used is the articulation of the Indo-Pacific concept, wherein the Indian and Pacific oceans and their littoral nations are construed to be conjoined into a single geopolitical

sole littoral representative whose shores are washed only by the Indian Ocean. The aforesaid three countries are constituents in a U.S.-led military alliance; India is not.

The other three countries’ biggest security challenges emerge from the maritime domain; India’s concerns are primarily territorial.

As the Quad is an informal security construct without any commitments for mutual assistance, the answer to India being a party to a conflict involving any of the other three is speculative.

Prime Minister Modi has articulated the Indo-Pacific as a ‘free, open, inclusive region, which embraces us all in a common pursuit of progress and prosperity’ ; a formulation that has universal application for all the countries in the region.

KRISHNAN SRINIVASAN

Retired Indian diplomat, historian, author, and former Indian Foreign Secretary.

18 INDIA AND THE INDO-PACIFIC

INDO-PACIFIC AS DEFINED BY WIKIPEDIA.

EXPERT COMMENT

Synergia: By trying to extend its maritime influence beyond the Indian Ocean into the Pacific, is India overextending its capacity?

MKN: It is a mistaken belief that as India emerges on the regional scene as a potential ‘net security provider’, it is anxious to project power beyond the Indian Ocean. There is no Indian Naval Doctrine that suggests this as a realistic option today. The Prime Minister has, on occasion, referred to the ‘Open Seas’ concept. The West has unilaterally chosen to interpret this as if India has endorsed the U.S.-driven ‘Open Seas Policy’ in the Pacific, particularly in the seas around Taiwan, the Philippines, and Japan. Certain Naval Commanders speak loosely about India’s role in the Indo-Pacific, but this is not tantamount to a Policy Statement. The U.S. would no doubt like India to firmly endorse its concept of an ‘Open Seas Policy’ in the Pacific, but this has yet to happen. India is clearly hedging its bets and is unwilling at present to enter into a confrontation with China on this count.

Synergia: India has no history of participating in military alliances in actual combat. Therefore, being a member of QUAD or any other demi-military alliance in the Indo-Pacific region, does it mean that in case of open hostilities in the Pacific, India will also become a party to the conflict?

MKN: India does not believe in the idea or concept of Military Alliances. This has been an entrenched belief as far as its State and Military Doctrines are concerned. Hence, it has been extremely careful in delineating the role of QUAD. From India’s standpoint, it is essentially a platform for a security dialogue and

nothing beyond this. QUAD, in this respect, is vastly different from AUKUS (the Security alliance between Australia, the UK and the US in the Pacific), which is a military alliance intended to safeguard the interests of these nations against, primarily, China.

Synergia: How real is India’s perceived role as a net security provider for the Indo-Pacific, considering the competing demands on the Indian Budget by the Army and the Air Force?

MKN: India’s policymakers have never aspired to be a net security provider for the Indo-Pacific, or for that matter, the Indian Ocean Rim countries. Many military leaders and some itinerant policy analysts do loosely mention the idea of India extending its security canvas to embrace the Indo-Pacific Region, but there is no substance to this idea or belief. Even in the Indian Ocean Region, India’s Naval doctrine does not endorse the idea of India being ‘a net security provider’ to countries in the region. Rather, while seeking to defend and protect India’s core interests from an external attack by sea, India has chosen to encourage a string of friendly countries in the Indian Ocean Rim to side with India against an external threat from the sea by nations outside the region. A well-defined mechanism is already in place for this purpose. This is, however, very different from a military alliance. By and large, India’s defence posture does not include any kind of military alliance, whether on land or the sea. This has been the case ever since India became independent.

MR. M.K. NARAYANAN

Former National Security Advisor, India

19 INDIA AND THE INDO-PACIFIC

EXPERT COMMENT

CONNECTIVITY IN FUTURE CITIES

FSO Networks can play a critical part in implementing India’s ambitious Smart Cities Mission

TRitika Simon is a Strategic Policy Adviser in Synergia Foundation. She has Masters degree from LSE in Economics & Risk and Society.

he Indian government initiated the Smart Cities Mission on 25th June 2015. Its goal is to foster sustainable and inclusive cities that offer core infrastructure, a clean and sustainable environment, and the application of smart solutions, thereby enhancing the quality of life for its citizens. The mission emphasizes implementing novel and innovative approaches at a small scale, which can be scaled up and replicated nationwide. This approach, known as the “lighthouse” strategy, aims to expedite the development and successful operation of such zones, promoting sustainable and inclusive growth in urban areas.

The goal of converting Indian cities into smart ones can only be achieved by leveraging the latest technologies, which reduce the time and resources needed to create the infrastructure. In pursuit of this vision, freespace optical (FSO) communications have emerged as a promising technology for delivering high-speed, secure, and reliable connectivity between future cities and their surrounding infrastructure.

SMART CITY PRIORITIES

The concept of future cities is rapidly gaining momentum as urban areas worldwide aspire to become more interconnected, sustainable, and technologically advanced. A smart city’s fundamental infrastructure

Free Space Optical (FSO) networks offer high-speed wireless communication with built-in security features but face challenges during implementation and operation. Atmospheric conditions like fog, rain, and snow can cause signal attenuation, reducing data rates or causing communication failures. Redundancy systems and optimized network design can improve reliability.

encompasses various essential components to enhance urban living standards. These include efficient water management with smart reservoirs and distribution systems to ensure access to clean water, reliable electricity supply, and comprehensive sanitation solutions covering solid waste management.

Additionally, the infrastructure extends to facilitating efficient urban mobility and transport systems, robust IT connectivity, and digital ecosystems.

Moreover, a smart city infrastructure incorporates provisions for affordable housing, promotes good governance practices such as e-government and citizen participation, ensures a sustainable environment, and fosters education and public health initiatives.

It also emphasizes the safety and security of citizens, with particular attention to vulnerable groups like women, children, and the elderly.

TECHNOLOGY

In implementing these initiatives, the program sets achievable benchmarks and selects suitable systems and structures to modernize planned cities. Employing a blend of retrofitting, redevelopment, and greenfield development approaches, the initiative identifies approximately 6 to 10 cities across various densely populated states.

FSO NETWORKS A GAMECHANGER

The concept of Free Space Optical (FSO) networks was first introduced in the 1960s, utilizing high-powered lasers to transmit large volumes of data through the air as a medium. However, being a Line of Sight (LOS) technology, it had many challenges to overcome.

The biggest advantage of using the optical spectrum in FSO networks is that no licenses are required, unlike other wireless Radio Frequency (RF)- based technologies. This results in significant cost savings on spectrum licensing fees.

FSO networks are also immune to interference from electromagnetic fields, making them highly suitable for co-existence with existing wireless deployments. The current hardware used in FSO networks can mitigate interference between multiple light sources with the same specifications.

Additionally, FSO networks offer advantages over RF-based technologies, such as higher data transmission rates, lower cost, and increased security.

In addition to their rapid deployment and cost efficiency, FSO communications offer various other benefits for future cities. They boast high security, as the light beams used for data transmission are challenging to intercept or disrupt. Furthermore, they are environmentally friendly, as they eschew the necessity for cables or other physical infrastructure.

HIGH-SPEED INTERNET: A MODERN BASIC NECESSITY

The World Bank’s assessment reveals a stark contrast in broadband high-speed internet accessibility, with 80 per cent of the population in advanced economies having access compared to only 35 per cent in developing nations. In this context, “broadband” denotes internet speeds faster than dial-up connections.

FSO communication holds promise for enhancing wireless communication for both those already equipped with broadband access and those lacking it. Optical communication offers bandwidth enhancements ranging from 10 to 100 times that of radio frequency (RF) wireless communication while demanding lower input power.

Additionally, the costs associated with establishing ground-based radio stations to receive FSO signals are notably lower than those of laying new optical fibre connections due to reduced labour and excavation expenses. In certain scenarios, utilizing FSO communication between ground locations proves more cost-effective than deploying optical fibre cables.

WHY FSO?

Topography: The distinctive geographical layout of Indian cities presents a challenge for network planners and engineers, often leading to concerns about network dead zones. These dead zones, areas with poor or no network coverage, are common in such environments. FSO lasers offer a solution to overcome the challenges posed by the unique topography of Indian cities. FSO technology can bridge network dead zones and enhance connectivity in areas where traditional network infrastructure may struggle to reach by providing a longrange, high-speed connection without needing physical cables.

21 CONNECTIVITY IN FUTURE CITIES

GENERAL PROCESS FOR FREE-SPACE OPTICAL COMMUNICATION.

Network Resilience: Smart cities, inherently reliant on data, necessitate strong digital connectivity. Free Space Optics (FSOs) offer a level of redundancy and primary access that align well with the demands of a smart city infrastructure. Recent assessments of FSO technology have demonstrated high-speed capabilities per link exceeding 100 Mbps, even in challenging atmospheric conditions where FSO technology historically faced limitations. These findings highlight the significant potential of FSO technology in enhancing the efficiency and reliability of smart city networks.

Security: Smart cities rely on sensors and interconnected devices to generate substantial amounts of data, which cybercriminals can target, potentially disrupting access to essential resources and even illegally accessing security cameras. For instance, in February 2021 in Florida, hackers manipulated the water supply by increasing the level of sodium hydroxide, which could have resulted in a significant public health crisis if not promptly detected and rectified. Free Space Optical (FSO) technology provides inherent security features by design, preventing unauthorized interception and control of signals, thereby enhancing the security of smart city networks and safeguarding against potential cyber threats.

CHALLENGES

Free Space Optical (FSO) networks offer high-speed wireless communication with built-in security features but face challenges during implementation and operation. Atmospheric conditions like fog, rain, and snow can cause signal attenuation, reducing data rates or causing communication failures. Redundancy systems and optimized network design can improve reliability.

Additionally, FSO networks require line-of-sight (LOS) connectivity, which can be limited in urban areas with tall buildings. Combining FSO with LAN or WLAN networks can overcome this limitation. Precise pointing accuracy is also essential for FSO networks due to

laser-based communication, achievable through tight mechanical tolerancing and steering mechanisms.

FSO networks may experience scintillation, causing rapid signal variations due to atmospheric conditions or ground location differences. To mitigate this, highly sensitive optical systems and tailored algorithms can improve signal reception. Additionally, deploying and maintaining FSO networks, especially in rural or remote areas with limited infrastructure, can be costly.

Assessment

At its core, the Smart Cities Mission (SCM) and its related initiatives represent an ambitious urban renewal and revitalization agenda. The primary goal of retrofitting existing cities is to align with the evolving needs of urban residents and enhance the capacity to address future challenges centred around sustainability, equity, and resilience. FSO can play a critical part in implementing India’s ambitious Smart Cities Mission

Despite the apparent challenges, the advantages of FSO networks, including high-speed data transmission and built-in security, often justify the expenses. Recently, this technology has demonstrated its capabilities as a viable competitor to existing commercial solutions. With the capability for gigabit throughput rates, it is positioned to be a key player in linking future cities.

Recent advancements have led to the commercialization of this technology, with numerous equipment manufacturers and service providers developing products and services that leverage the advantages provided by free space optics (FSOs), including a few in Bangalore.

22 CONNECTIVITY IN FUTURE CITIES

SILICON SAVANNAH IN THE MAKING

In the heart of East Africa, a quiet technological revolution is underway with Kenya rapidly evolving as a dynamic hub of innovation.

KDiya Celine Simon Research Associate in Synergia Foundation

KDiya Celine Simon Research Associate in Synergia Foundation

enya serves as an economic hub in East Africa due to its strategic location, well-developed infrastructure, and vibrant economy. It is a key player in regional trade and commerce, with a diverse economy that includes sectors like tourism, agriculture, manufacturing, and finance. Kenya’s Vision 2030 initiative aims to position the country as a globally competitive and prosperous nation, further solidifying its economic significance in the region.

In the last decade, this popular tourist destination has undergone an impressive rise in tech and innovations, making information and communication technology (ICT) the key growth driver. East Africa has a young and well-educated population, so it is a great place to look for skilled developers. Established tech giants like Microsoft, Google, VISA, and PwC have already recognised its potential.

THE LARGER PICTURE

Kenya gained independence from British rule on December 12, 1963, after nearly 80 years of colonial rule. Since then, Kenya has made tremendous progress. However, British colonial rule which was characterised by unfair labour practices, structural racism, and forced resettlement, needed structural reforms post-independence.

Over 60 major Indian companies have invested in various sectors, including manufacturing, real estate, pharmaceuticals, telecom, IT & ITES, banking and agro-based industries, creating thousands of direct jobs for Kenyans. More recent investments by Indian corporations in Kenya include Essar Energy (petroleum refining), Bharti Airtel, Reliance Industries Ltd. (petroleum retail), and Tata (Africa) (automobiles, IT, medicines, etc.).

Kenya’s political stability in an otherwise volatile region, contributes to its geostrategic importance. Since independence, the country has been a relatively stable democracy with regular elections and peaceful transitions of power. This stability makes Kenya an attractive destination for foreign investment and a key partner in regional peace and security initiatives.

Kenya plays a significant role in regional politics and diplomacy, exerting influence beyond its borders. It is a key member of regional organisations like the East African Community (EAC) and the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA), contributing to regional integration and cooperation. Additionally, Kenya’s involvement in peacekeeping missions and diplomatic engagements on the international stage en-

GLOBAL SCAN

hances its strategic importance in East Africa. Recently, it offered its services to resolve the growing dispute between Somalia and Ethiopia over port access in the breakaway region of Somaliland.

THE INDIAN CONNECTION

Kenya has a long Indian connection, although not always pleasant. For the construction of the railway line from the Kenyan coastline to the Ugandan interior to enable the exploitation of the wealth of Africa, the British colonists brought around 32000 Indian indentured labourers between 1896 and 1901. Over 2500 labourers died, many devoured by the notorious man-eating lions of Tsavo, a death rate of four per mile of track laid.