An inspiration to girls and women around the world, Pippi Longstocking has become a feminist icon and a universal symbol of what it means to be Swedish.

By Noelle Norman

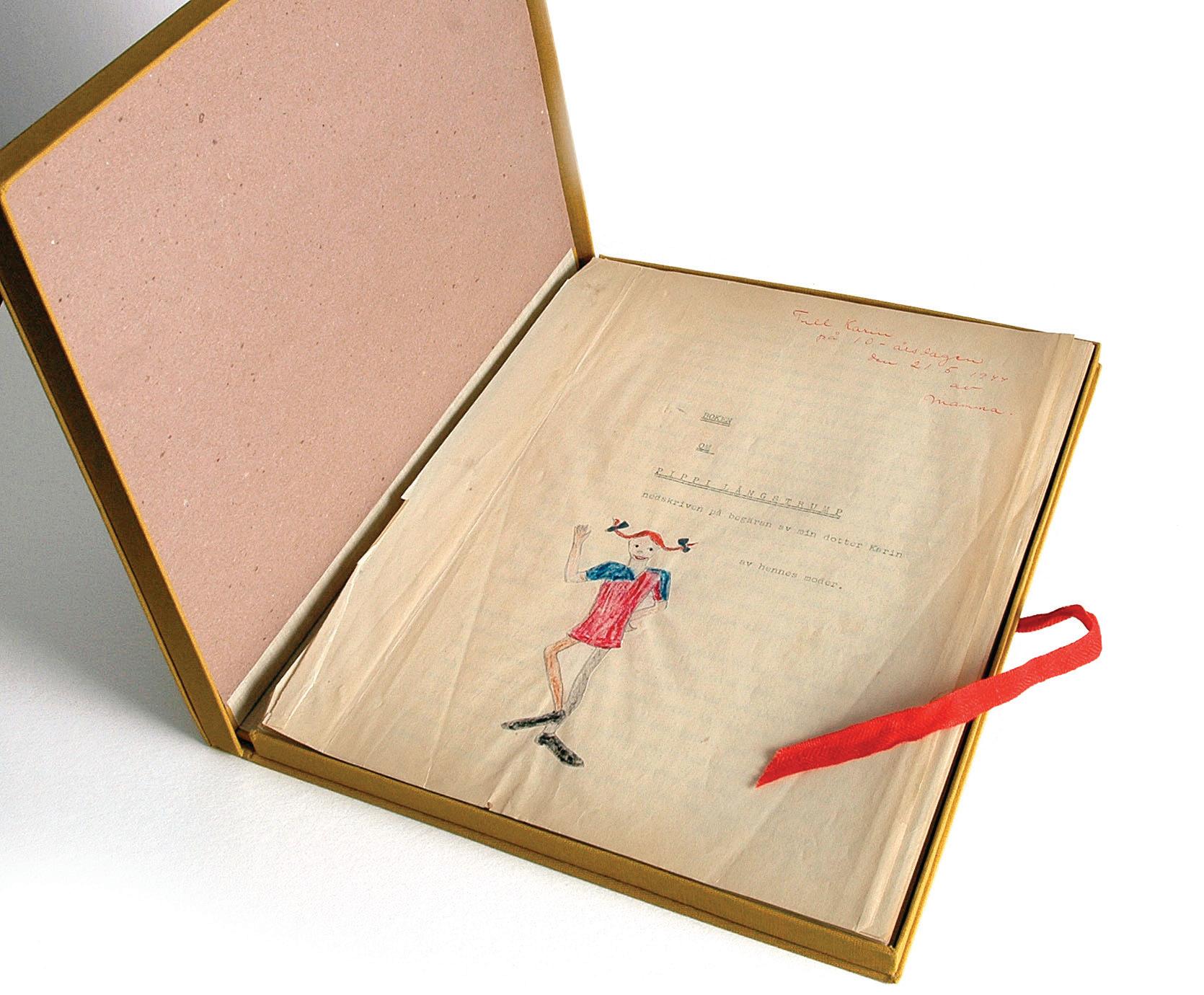

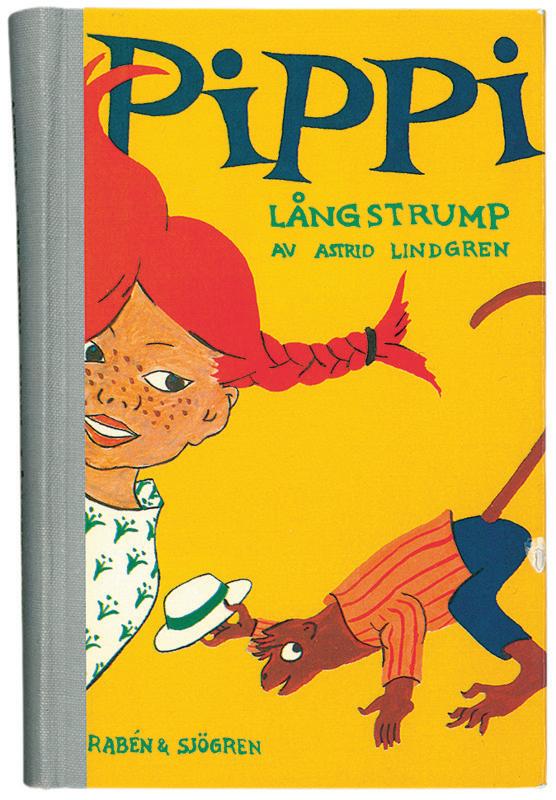

In the winter of 1941, Astrid Lindgren’s 7-year-old daughter Karin was at home recovering from pneumonia. She asked her mother to tell her stories about Pippi Longstocking – a name Karin made up on the spot. Lindgren obliged and improvised stories about an “anything-but-pious” girl with “boundless energy” who also happened to be the strongest girl in the world. Pippi had been born and Lindgren continued to amuse Karin, as well as Karin’s friends and cousins, with stories of Pippi’s adventures. In April 1944, while at home nursing a leg injury, Lindgren wrote down her stories about Pippi. She gave one copy to Karin and sent the other to Sweden’s largest book publisher, Albert Bonniers Förlag. They refused it, deeming it “too advanced”. But their competitor Rabén & Sjögren published the first book about Pippi Longstocking the following year.

With no parents to tell her what to do, a bag full of gold to finance her adventures, and super human strength to take down thieves and bullies, Pippi was completely free to always speak her mind and live according to her own rules. To endow a young girl with that kind of power was a radical proposition for a time when both women and children were meant to know their place, but the book became

an immediate success.

“Its child heroine was widely hailed as a joyful, post-war figure of liberation,” says Leonard Marcus, children’s book historian and critic. “Here was a life-affirming antidote to the terror and destruction humankind had just endured, and coming as it did from a young author already known for her tartly satirical tendencies, here too was a subtle rebuke to the generation then in power. If the grown ups could get things that wrong, Astrid Lindgren seemed to be telling the world, perhaps it was time for the children to have a turn at being in charge, at the very least in matters where their own well being was concerned.”

One prophetic critic called it

“the children’s book of the century”. Someone else referred to it as “a revolution in the nursery.” However, there were critical voices as well as the book stirred controversy over its “anti-authoritarian” tendencies.

John Landquist, a literary critic and professor of pedagogy, called Pippi “an unpleasant thing which scratches at one’s soul,” adding that “she acts like she's mentally ill.” Emotionally unstable, Pippi set a bad example for other children, argued Landquist.

The public, however, did not agree. They loved Pippi from the start.

“For me, today, that’s a little bit surprising because Pippi is in so many ways revolutionary,” says Erik Ullenhag, Consul General of Sweden to New York City.

To mark the 80th anniversary of Pippi, the Swedish Consulate General kicked off their International Women’s Day celebrations by hosting a panel discussion about the impact of Pippi.

“She was like the rain or the wind, she was always there,” says Astrid Lindgren’s great-grandson Johan Palmberg when asked about when he first became aware of Pippi.

Also a jury member for the Astrid Lindgren Memorial Award (ALMA), Palmberg has spent a great deal of time contemplating the spirit and legacy of Lindgren and her literary characters. When asked what Pippi symbolizes, he replies:

“She’s been around for such a long time and she’s become so abstracted that she just symbolizes Sweden in some way. If you go to a soccer match and the Swedish national team is playing, the fans will be wearing a Pippi wig, or maybe a Viking helmet with a built in Pippi wig,” he laughs. Then, on a more serious note, he adds, “she symbolizes a lot of different things to different people. She symbolizes what Swedes would most like people to think about Sweden. This sort of antiauthoritarianism, I guess.”

In 1938, Superman first appeared in American comic books. The following year, the super hero had made it to Sweden. In 1941, Superman was released in cinemas in a series of animated shorts. It is not known when Astrid Lindgren first learned of his existence, but a sketch of Superman on one of the early Pippi manuscripts seem to indicate that Lindgren was in fact inspired to create a super hero herself. Why not a young girl? To Lindgren it was the children who had it all figured out. She once commented that it was enough to observe the

young “to see what the Lord was really thinking when he made people, that they should be good and laugh at life.” “Why can't we hold on to the ability to see Earth and grass, pattering rain and starry skies as blessings all our lives?” she wondered.

Unlike most super hero tales, there is no origin story in the books that explains how Pippi became so strong; nothing to even suggest her powers are magical, notes children’s author Laurie Halse Anderson, the 2023 recipient of the Astrid Lindgren Memorial Award.

“This is how she is. And in truth, she’s carrying within her the powers and strengths of all children. So I find that just kind of earth-shaking,” she says. “Pippi is in her own canon, the only super hero to be a child.”

Reflecting on what Pippi meant to her, Halse Anderson returns to her super natural strength.

“Pippi picked up a horse. Now, I

was a strong kid, and not a small one, and my mother had this notion of what it was to be a female that was very different than what I felt myself to be. And this character picked up a horse,” says Halse Anderson. “That changed me, as did the rest of the story and the absolute bizarreness and the joyfulness of that character. Even when she’s taking on the bullies, she’s doing it very cheerfully, which is a good message for all of us. She returns again to kindness as soon as she dispatches them, and so it left a really lovely mark inside my heart. It helped me find my path.”

Published in the US and Canada since 1950, stories of Pippi have since been translated to more than 80 languages.

“Not every translation was equally faithful to the original,” says Leonard Marcus. “In France, for instance, concern that rigorously logical French children would refuse to believe that

even the strongest girl in the world could lift a horse, prompted a translator there to downsize the horse to a pony.” While this may seem amusing, at some point putting words in an author’s mouth can beome an act of censorship. “A fate that has befallen Pippi to varying degrees over the years, from Norway to Iran and even, some have said, in Sweden,” says Marcus.

He is referring to the fact that the book was banned in Iran, and to the decision by the Norwegian and Swedish Broadcasting corporations to edit phrases that would be considered offensive today. In the TV series about Pippi Longstocking, first broadcast in 1969, Pippi refers to her father as “King of the negroes of the South Seas” and pretends to be Chinese by slanting her eyes – both of which have since been removed with permission from Lindgren’s heirs.

“We want to do everything we can to make sure people don’t get hurt. That’s why we believe SVT is doing

the right thing. Astrid Lindgren stood for values that were the complete opposite of offending people,” explained Nils Nyman, grandson of Astrid Lindgren and CEO of Saltkråkan AB, the company which manages Astrid Lindgren’s rights. The following year, in 2015, Saltkråkan AB also decided to publish an edited version of the printed book.

Outdated language use aside, this now eighty-year-old story has a message which still feels very modern and which continues to transcend culture. Jamia Wilson, feminist activist, writer, Vice President and Executive Editor at Random House, remembers reading Pippi in Saudi Arabia where it had somehow skirted the censors.

“I’m from South Carolina and my parents moved to Saudi Arabia when I was a little short of six years old, and I had to figure out how to make friends with kids who spoke 50 different languages at my school.”

Wilson says she spent a lot of time in the school library where she came across Pippi. The book offered her a way to connect with other kids at her school, in particular her new neighbors from Stockholm.

“It was so wonderful to be able to talk to

them about Pippi,” says Wilson. “I see her as someone who brings people together.” Pointing to her AfricanAmerican braids, Wilson adds, “I was made fun of for having different hair as a child, and I remember telling people I have hair like Pippi’s hair even thought it’s not red. And Pippi is cool! It was nice to have her there, and to sort of say it's okay that I’m different from everybody else.”

Ullenhag believes the message of Pippi still resonates.

“It’s about a young girl living on their own, standing up against stupid rules and oppression, but also standing up for the weaker human beings,” he says. “For me, Pippi Longstocking is one of these feminist icons that for generations of kids around the globe have made them able to take that extra step, to do something or to see that even if you are a young girl or a woman, you have the right to take place in society.”

In 2025, Pippi Longstocking turns 80 years old and her birthday is celebrated around the world, highlighing her global reach and impact. Over the years, much has been lost – and found – in translation.

By Kajsa Norman

It was thanks to Pippi that I left Japan,” says Noboko Wilson, a children’s librarian at St. George Library in Staten Island, New York. “It wasn’t that I didn’t like Japan, but Pippi planted a desire in me to see the world.”

In 1990, Wilson arrived in the US as a graduate student. Raised in Tokyo, she remembers first reading Pippi

when she was about 8 years old. Wilson started with the Pippi books, and soon progressed to Astrid Lindgren’s other works. The stories had such an impact on her that she even started to learn Swedish.

“I listened to introductory Swedish on my cassette player,” Wilson remembers. “I even thought about moving to Sweden, but then I wondered

what I would do there. Besides, I read somewhere that the average height of Swedish women is 166 centimeters, so I thought I’d feel short,” she laughs.

For Wilson, Pippi came to symbolize freedom and taking control of one’s life.

“Although personally I identified more with Annika [Pippi’s friend and neighbor] than with Pippi. I was more

reserved and traditional,” she says. “My strongest memory of Pippi is a scene where Tommy and Annika look in through a window at Pippi all alone in her house late at night. I remember wondering if she was lonely.”

In Japan, Pippi was never surrounded by controversy as the fictional character was never regarded as an example of how children could live or behave.

“In Japan, it was always clear that this was fiction,” says Wilson.

In Sweden, however, the debate regarding whether Pippi constituted a positive role model or not, is perhaps indicative of the fact that independent children were not mere fiction, but about to become a stated goal of the social policies of the time.

Already in the 1930s, Swedish Social Democrats like Alva Myrdal had begun to advocate for the liberation of children from their parents, and by the late 1950s, the standard family constellation—with a male provider and a female housewife—was under fierce intellectual attack. In 1972, around the time the first Pippi movie came out, the Swedish Social Democrats launched a manifesto called “The Family of the Future: Socialist Family Politics.” Citizens were to be freed from the old-fashioned family structures that trapped them in dependencies. True independence and freedom of choice was only possible if everyone was financially self-reliant. This was no longer just about freeing women from their men, but also about freeing children from their parents, and vice versa. By regarding children and youth as independent individuals with their own rights, and guaranteeing them free education and healthcare, the state had freed them from the strong dependency on

their parents that characterizes many cultures. The Swedish family policy reforms introduced in the late 1960s to the mid-70s account for some of the most far-reaching examples of public policy that the world has ever seen when it comes to the individualization of society. Some argue that such radical individualism inevitably leads to atomism, isolation and loneliness. Thus, according to this interpretation, an independent Pippi is likely to be a lonely Pippi. And Sweden, with about half of its population living alone, is likely to be a lonely country.

Throughout 2025, Pippi Longstocking’s 80th anniversary is being celebrated in different ways in Sweden and around the world. In New York City, many public library branches are hosting Pippi events and the CityParks PuppetMobile is performing Pippi Longstocking as marionette theater in parks across the city’s five boroughs. American playwright Zakiyyah Alexander adapted the story for the puppet show, which premiered in Queens

in May. In Alexander’s adaptation, Pippi is portrayed as an unusual but lonely child who misses her parents deeply and the performance ends with Pippi rejoicing when her father finally returns home to his little girl.

Altering the narrative to emphasize American-style traditional family values and happy endings might make for a better cultural fit, but such an interpretation deprives Pippi of one of her most important characteristics – her emotional independence. While Pippi occasionally talks to her mother in heaven and reminisces about her adventures with her father at sea, she actively chooses a life alone at Villa Villekulla and is not one to dwell on feelings of loneliness.

In Swedish, the word “ensam” is a homonym with two entirely different meanings, namely “alone” and “lonely”. The fact that Pippi lives “ensam” (alone) does not mean that she is “ensam” (lonely). In the original story, Pippi throws her dad a party upon his return but decides not to accompany

him when he leaves, nor does she try to convince him to stay. With no idea when, or if, they will see each other again, they wish each other the best of luck as he sails off to sea and she continues her own independent life at Villa Villekulla – alone, but not lonely.

That a 9-year-old girl could live alone without being lonely, is apparently less believable to a North American audience than that she should be able to lift a horse –perhaps because superhuman physical strength is such a common feature in North American pop culture.

While changing a character’s personality traits should be off limits in any translation or adaptation, there is a case to be made for some cultural adjustments. If something is so offensive in a particular culture that retaining it detracts from the main message

of the story, it probably makes sense to remove it.

As part of my survey of the various Pippi events in NYC, I head to the Bronx to attend a local library screening of the original Pippi Longstocking movie from 1973. According to Census data from 2020, almost 90 percent of the population in the Bronx are Black, Hispanic, or Asian and I find myself silently praying that the English-language version aligns with the newly edited Swedish version. I can only imagine the reaction in the Bronx if Pippi proclaims her father to be “King of the negroes”. I needn’t have worried. All content that would be considered racist today has been edited out. This, however, does not mean that we’re in for a smooth ride.

First to show up to the screening is 9-year-old Miles who tells the

room he just finished reading the book about Pippi the previous night and is excited to watch her take on the police officers. “I wonder if she actually does, even in the movie?” he says.

Miles is not disappointed. As police officers Kling and Klang arrive at Pippi’s house with orders to take her to an orphanage, Pippi throws them to the ground and later leaves them hanging off the ladder at the top of her roof until they beg for mercy and retreat in humiliation. We then watch as Pippi walks into the local candy store and demands 18 kilos of candy, nonchalantly tossing a gold coin onto the counter. Together with some kids from the neighborhood, Pippi, Tommy and Annika then proceed to stuff their faces on it all. In fact, the movie is one scene after the other of Pippi following her every impulse – refusing to go

Hope you enjoyed this sample of Swedish Press.

To read more, please click the link https://swedishpress.com/ subscription to subscribe.