Architecture of Evil

Villainy and Its Vessel

By Susie Caldwell

By Susie Caldwell

Thesiscompletedasapartof theBachelors of Architecture program at California Polytechnic State University, San Luis Obispo under the guidance of Ansgar Killing and Greg Wynn during the 20162017academicyear.

Unless otherwise cited, all discourse, images, and graphics are unique products of Susie Caldwell.

Abstract Theories of Evil Kant’s Theory of Evil Perception of Space Deined Arendt’s Theory of Evil Impressions of Emotions Evil Action Theories Evil Character Theories What is Evil in the context of this thesis? Perception Abstract Sculpture Need for Control 22-25 26-33 34-47 4-9 10-19 10-11 26-29 12-13 30-33 14-17 18-19 20-21 Contents

Precedents Design Casa Brutale Site Design Intent Mirage Concept Model Pionen, White Mountain Spatial Implications Architecture of Evil Deined 48-49 50-55 56-85 50-51 56-59 52-53 60-61 54-55 62-65 66-85

Absract

This thesis explores the relationship between villainy and its vessel—what aspects of the villain inluence the lair and how the lair in return shapes the villain. What are the psychological effects of living in isolation? How does the luxury of the residence affect the inhabitant? Are visitors negatively affected by subtle or overt luxury? Can architecture be used as a catalyst for evil? Does the lair itself play a role in the manipulation, control, and ultimate defeat of the enemy? What other features play a psychological role in the triumph over the hero? Furthermore, why is it that villain lairs are often so easily recognizable in ilms and other media? What is it about certain spaces that we instantly identify as being “it for a Bond villain”? Are there speciic qualities that universally indicate the sinister nature of a space? Can space be sinister, or it is a matter of perspective?Doweassociatecertainspaceswithvillainybecausewearefamiliar with the corresponding villain? Are villain lairs and hero hideouts inherently different spaces or do their residents assign meaning and connotation? The psychological aspects both of villainy and of architecture, while complex and luid, serve as the base for this thesis.

4

5

WHAT IS THE ARCHITECTURE OF EVIL? WHAT IS EVIL?

6

7

In order to deine what Evil is, it is important to understand what Evil is not. To do so, we must begin with an understanding of the history of theories that have attempted to deine evil and the criticisms that have shaped the modern concept of evil.

For the sake of this thesis:

Evil focuses only on the most morally despicable actions, characters, and events, excluding natural evils and lesser moral evils. Forgoing the religious ideas that evil is the opposite, or absence of good, as deined by the character of God, Evil is understood as a secular, moral concept.

8

“Evil”

“Evil” is strictly a secular, moral concept that applies only to real or plausibly realistic characters, actions, or events.

9

It is important to note that “Evil” in the context of this thesis does not imply ties to dark spirits, the supernatural, or the devil.

does not reference ictitious monsters, dark forces, Satanic possession, or powers and abilities that defy scientiic explanation or human understanding.

Kant’s Theory of Evil

Evil is having a will that is not fully good.

Kant’s theory of evil states that evil is having a will that is not fully good.1 According to Kant, the only two motivations for actions are moral law and selfinterest. A person with a morally good will chooses to perform morally right actions for no other reason than that they are morally right.2 Beyond this, there are three degrees of evil: frailty, impurity, and perversity of will.

Those who suffer from frailty of will are those who attempt to perform morally right actions because they are right, but ultimately do wrong because they are too weak.

A person with an impure will, however, is motivated both by moral law and self-interest. While a person with an impure will may perform the morally right action, such actions are morally worthless if they are motivated by any amount of self-interest.

10

1. Kant, I., 1785, The Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals, M. Gregor (Trans. and ed.), New York: Cambridge University Press, 1997, 4:393-4:397

The deepest level of corruption is the perverse or wicked will, the person who prioritizes self-love over moral law. Their actions only conform to moral law if said actions are also in their best interest. Kant believes this is the worst form of evil possible for a human being, equating one that possesses a perverse will with an evil person.3

Critics argue that whether a person is evil, and to what extent, is dependent upon details about their motives and the actual harm brought about by their actions. Torture for sadistic pleasure, critics argue, cannot be compared to lying in order to protect the reputation of another, whereas Kant see the two as equally evil.4

2. Kant, 1793, Religion Within the Limits of Reason Alone, T. M. Greene and H. H. Hudson (trans.), La Salle, Illinois: The Open Court Publishing Co., 1960, Bk 1.

3. Kant 1793, Bk 1, 24-26.

4. Calder, Todd, “The Concept of Evil”, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2016 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), URL = <https://plato. stanford.edu/archives/win2016/entries/concept-evil/>.

11

While Kant provides a limited definition of evil that fails to account for possible motives other than moral law and self-interest, his concept of degrees of Evil still holds merit.

Arendt’s Theory of Evil

Radical Evil is incomprehensible, stripping human beings of freedom.

Hanna Arendt, in an effort to understand the horrors of Nazi death camps, ascribes new meaning to the term radical evil. Arendt deines radical evil as a new form of wrongdoing that cannot be captured by other moral concepts.

Whereas Evil might simply replace incomprehensible when describing egregious actions,radical evil involves stripping human beings of any freedom, transforming them into “living corpses.” Radical evil is not motivated by any humanly understandable reasons, such as self-interest, but “merely to reinforce totalitarian control and the idea that everything is possible.”

1

In her exploration on the individual culpability of those who perpetuate evil, such as Adolf Eichmann—the Nazi functionary who organized the deportation of Jews—Arendt discovered that these so-called “desk-murderers” were not driven by incomprehensible motives. Rather, “It was sheer thoughtlessness— something by no means identical with stupidity—that predisposed [Eichmann] to become one of the greatest criminals of that period.”

2 Eichmann’s motives were not monstrous, but rather banal. Arendt argues that ordinary people can be sources of evil in certain situations.

1. Arendt, H., 1951 [1985], The Origins of Totalitarianism, San Diego: A Harvest Book, Harcourt, Inc., 437-459.

2. Arendt, H., 1963 [1994], Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil, New York: Penguin Books, 287-288.

12

Evil can be dividing into three categories, or degrees: Comprehensible, Incomprehensible, and Radical.

Applying the notion of degrees of evil to Arendt’s theory, one could categorize evils as comprehensible, incomprehensible, and radical. Comprehensible Evils are most easily explained in the context of the Second World War, as Arendt ascribes Eichmann’s evils to thoughtlessness. Motives of loyalty to “higher values,” fear, and even ignorance are all comprehensible reasons for the atrocities carried out by members of the Nazi party, but the actions that resulted were nonetheless Evil. Radical Evils, as previously described, are the epitome of heinous actions that so utterly violate the freedom of others without any justiiable moral reasoning.Actions that are carried out with full knowledge and intent of foreseeable harm, lacking in moral justiication, yet do not cross the line into Radical Evils are classiied as Incomprehensible.

It is these Incomprehensible Evils, the middle ground, that serve as the focal point of this thesis.

13

Evil Action Theories

When discussing evil, theorists tend to focus on either evil character or evil action. Kant’s theory looks at the character of a person, whereas Arendt addresses evil actions. This section will discuss various theories on evil actions.

While it is almost universally accepted that wrongfulness is an essential component of evil,1 most question what more is required. That is to say, is evil qualitatively distinct from wrongdoing, or merely quantitatively distinct? In order to answer this question, one must irst deine qualitatively distinct.

Some theorists agree that “two concepts are qualitatively distinct if, and only if, all instantiations of the irst concept share a property which no instantiation of the second concept shares.”2 To argue that evil is quantitatively distinct from wrongdoing is to argue that evil actions possess an extra quality lacking in ordinary wrongful actions. Hillel Steiner argues that this extra quality is the perpetrator’s pleasure.3

1. Card, C., 2002, The Atrocity Paradigm: A Theory of Evil, Oxford: Oxford University Press; Garrard, E., 1998, “The Nature of Evil,” Philosophical Explorations: An International Journal for the Philosophy of Mind and Action, 1 (1): 43–60. Formosa, P., 2008, “A Conception of Evil,” Journal of Value Inquiry, 42 (2): 217–239.

2. Steiner, H., 2002, “Calibrating Evil,” The Monist, 85 (2): 183–193; Garrard 1998; Garrard, E., 2002, “Evil as an Explanatory Concept,” The Monist, 85 (2): 320–336.

3. Steiner 2002, 184.

14

Evil is deined by actions, rather than by character.

Todd Calder, however, argues that qualitative distinction is contingent upon entirely unique essential properties. Thus, evil actions cannot share the same essential properties as wrongful actions. Calder argues that intended harm is an essential quality of evil, whereas wrongdoers need not intend harm to perform wrongful actions.4

Harmful Evil

Are evil actions inherently harmful? While many theorists would argue that they are,5 one cannot answer this question without irst answering the question: what is harm? Most commonly, harm is equated with pain and suffering. For the sake of Calder’s theory, pain is restricted to physical sensations, excluding psychological or emotional traumas. Calder proposes that if the sadistic yet painless destruction of a reputation is considered evil, with the assumption that only painful experiences are harmful, then some evil actions are not harmful.6

*NOTE: If one deines pain as any physical or mental suffering, however, it could be argued that a destroyed reputation can result in mental pain, thus negating the argument that some evil actions are not harmful.

Some theorists argue that sadistic voyeurism, while not harmful, is still evil.7 When one enjoys witnessing, but does not cause, the extreme suffering of another,this act of sadistic voyeurism can be considered evil despite causing no additional harm to the victim. Paul Formosa argues that the true evil of sadistic voyeurism is the lack of intervention to prevent the harm, thus transferring partial culpability to the voyeur.8

4. Calder, T., 2003, “The Apparent Banality of Evil,” Journal of Social Philosophy, 34 (3): 364–376.

5. Card 2002; Kekes, J., 2005, The Roots of Evil, Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

6. Calder 2016.

7. Calder, T., 2002, “Towards a Theory of Evil: A Critique of Laurence Thomas’s Theory of Evil Acts,” in Earth’s Abominations: Philosophical Studies of Evil, D. M. Haybron (ed.), New York: Rodopi, 56; Garrard 2002, 237.

8. Formosa 2008, 227.

15

It can be further argued that the evil component of sadistic voyeurism is the person rather than his or her actions. The voyeur may be an evil person who, in this particular instance, does not perform an evil action because he or she does not cause any harm.9 Lack of opportunity or inability to act does not reduce the evil intent.

Evil involves facing the choice between inlicting tremendous harm and not doing so, and choosing harm. This does not, however, limit evil to a product of intent to destroy. Rather, evil is also the product of the lack of intent to refrain from causing great foreseeable harm.10

Even if we agree to separate evil from the causing of harm, it would appear that evil actions do require some level of harm; someone must suffer even if the evildoer is not personally responsible for the suffering.11

Assuming that evil necessitates harm, one must then ask how much harm is required for a person or action to be considered evil. According to John Kekes, evil harm must be “serious and excessive,”12 specifying that a serious harm “interferes with the functioning of a person as a full-ledged agent.”12 The harm of evil can also be deined as an intolerable harm, one that makes life not worth living in the eyes of the victim. Claudia Card cites the deprivation of basic needs as well as severe physical or mental suffering as intolerable harms.13

Motivations for Evil Actions

Card’s theory deines evil as “reasonably foreseeable intolerable harms produced by inexcusable wrongs.”14 Evildoers, according to this theory, “are motivated by a desire for some object or state of affairs which does not justify the harm they foreseeably inlict.”

15

9. Haybron, D.M., 2002a, “Consistency of Character and the Character of Evil,” in Earth’s Abominations: Philosophical Studies of Evil, D.M. Haybron (ed.), New York: Rodopi, 264.

10. Romig, R. “What Do We Mean By “Evil”?,” The New Yorker, July 25, 2012, http://www.newyorker.com/books/page-turner/what-do-we-mean-by-evil.

11. Russell, L., 2007, “Is Evil Action Qualitatively Distinct From Ordinary Wrongdoing?” Australasian Journal of Philosophy, 85 (4): 676.

12. Kekes 2005, 1-3.

13. Kekes, J., 1998, “The Reflexivity of Evil,” Social Philosophy and Policy, 15 (1): 217.

14. Card 2002, 16.

15. Calder 2016.

16

While Card’s theory covers a multitude of potential motivations, others suggest that evildoers’ actions are the result of a speciic reason, such as pleasure,16 malevolence, malice, the desire to annihilate all beings,17 or the destruction of others simply for destruction’s sake.

Others argue that it is not the presence of a particular motive, but rather the absence of a preventative reason. Adam Morton promotes the notion that evildoers lack the barriers that prevent ordinary people from considering harming or humiliating others.19

Affect: A Necessary Component of Evil?

Some theorists believe that evildoers must feel a certain way when they commit an action for it to be considered Evil. For example, an action would only be considered evil if the perpetrator felt either pleasure from causing harm or hatred towards the victim.20 One could argue that evil consists of only two components: pleasure and wrongdoing, and that “evil acts are wrong acts that are pleasurable for their doer.”21

Critics argue that pleasure is not necessary—it is enough to cause suficient harm for an unworthy goal. Furthermore, it is not necessarily evil to take pleasure in wrongful actions that do not cause harm, such as lying.22

Responsibility for Evil Actions

It is universally accepted that evildoers must act voluntarily so that they are morally responsible, intend or foresee the suffering that their actions will cause, and lack any moral justiication for such actions.23 For the sake of this thesis, it is assumed that the evildoer is not a psychopath, has a normal upbringing, and is acting of their own free will, so as not to cause controversy where blame is concerned.

16. Steiner 2002.

17. Eagleton, T., 2010, On Evil, New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press.

18. Cole, P., 2006, The Myth of Evil: Demonizing the Enemy, Westport, Connecticut: Praeger.

19. Morton, A., 2004, On Evil, New York: Routledge. 57.

20. Thomas, L., 1993, Vessels of Evil: American Slavery and the Holocaust, Philadelphia: Temple University Press. 76-77.

21. Steiner 2002, 189.

22. Russell 2007.

23. Kekes 2005; Card, C., 2010, Confronting Evils: Terrorism, Torture, Genocide. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.; Formosa 2008.

17

Evil Character Theories

Evil is deined by a person’s character rather than their actions.

There are six main types of theories regarding evil character:

The frequent evildoer account deines an evil person as one who performs evil actions often enough.1 How often is “often enough”? What, then, of those who only perform evil occasionally? What of those who lack the ability to carry out the desired evil actions? Inability has no effect on character; it would seem that one could be an evil person despite rarely,if ever,carrying out evil actions.2

Dispositional accounts of evil aim to solve the problem of inability by classifying an evil person as one who is strongly and ixedly disposed to perform evil actions when in autonomy favoring conditions. That is to say, an evil person is someone who is very likely to do evil, is unlikely to change their disposition to do evil, and is not deceived, threatened, coerced, or pressured to act in a particular way.3

1. Kekes, J., 1990, Facing Evil, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 48; Kekes 1998, 217; Thomas 1993, 82.

2. Haybron, D.M., 1999, “Evil Characters,” American Philosophical Quarterly, 36 (2): 132.

3. Russell, L., 2010, “Dispositional Accounts of Evil Personhood,” Philosophical Studies, 149 (2): 249.

18

Affect-based accounts argue that evil people are those who derive pleasure from the pain of others.4 This line of thinking excludes those who perform arguably evil acts of out indifference, as well as those who unintentionally feel pleasure at the pain of others. Those who do not welcome such feelings and reject the reaction of pleasure as a result of others’ pain are not evil—one cannot control one’s initial feelings any more than one can control one’s patellar relex.5

Motive-based accounts argue that an evil person is one who has “a regular propensityfore-desires.”6 Ane-desireisadesireforsomeoneelse’ssigniicant harm for an unworthy goal, provided that there is no self-deception involved.

Consistency accounts consider a person evil only if he or she has consistent, rather than occasional, evil-making characteristics.7 This restricts evil to those who never display genuine positive characteristics, such as compassion or empathy. On this account, one who both participates in frequent torture and cares for the ill would not be considered evil, though most would argue such a claim.8

Extremity accounts deine evil people as thosewho“havecertainbad-making characteristics to an extreme degree.”9 Some argue that evil people possess the worst kinds of vices to an extreme degree. This theory follows the mirror theory: that evil people are the perverse mirror image of moral saints.10

4. McGinn, C., 1997, Ethics, Evil, and Fiction, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 62.

5. Calder 2003, 368–369.

6. Ibid.

7. Calder 2003; Calder, T., 2009, “The Prevalence of Evil,” in Evil, Political Violence and Forgiveness, A. Veltman and K. Norlock (eds.), Lanham, Maryland: Lexington Books; Card 2002; Thomas 1993; Barry, P.B., 2009, “Moral Saints, Moral Monsters, and the Mirror Thesis,” American Philosophical Quarterly,

8. Calder 2009, 22-27.

9. Calder 2016.

10. Barry 2009, 171-173.

19

What is Evil?

“Evil describes the limits of what malevolence we are able to bear.”

-Rollo Romig

For the sake of this thesis:

Evil is the deliberate, intentional control, restriction, manipulation, or inliction of harm for the express purpose of experiencing pleasure, satisfying ego, establishing unnecessary dominance and superiority, or the subjugation of others.

Evil is the self-service of the perpetrator at the expense of others with no regard for the well-being of the affected, if not the express pleasure at their misfortune.

Evil is facing the choice between inlicting tremendous harm and not doing so, and choosing harm.

Evil is the lack of intent to prevent great foreseeable harm.

Evil is a conscious choice, not a condition of birth. One must choose Evil of his or her own free will. Evil cannot be explained or excused as an innate characteristic resulting from anything less than total, unimpeded agency.

20

Evil as a term carries a weight that no number of “very’s” preceding “wrong” will ever match. Evil encompasses the “unfathomable depths of human motivation.”

A villain is characterized by a propensity and ability to carry out Evil actions.

A villain is not a psychopath.

A villain has a normal upbringing.

A villain is acting of their own free will.

A villain is not under the control of another.

A villain is in full possession of all mental faculties.

A villain is solely culpable for all of his or her actions.

This thesis examines Evil and Villainy in a traditionally fictional, theoretical sense and does not address real-life cases of Evil.

21

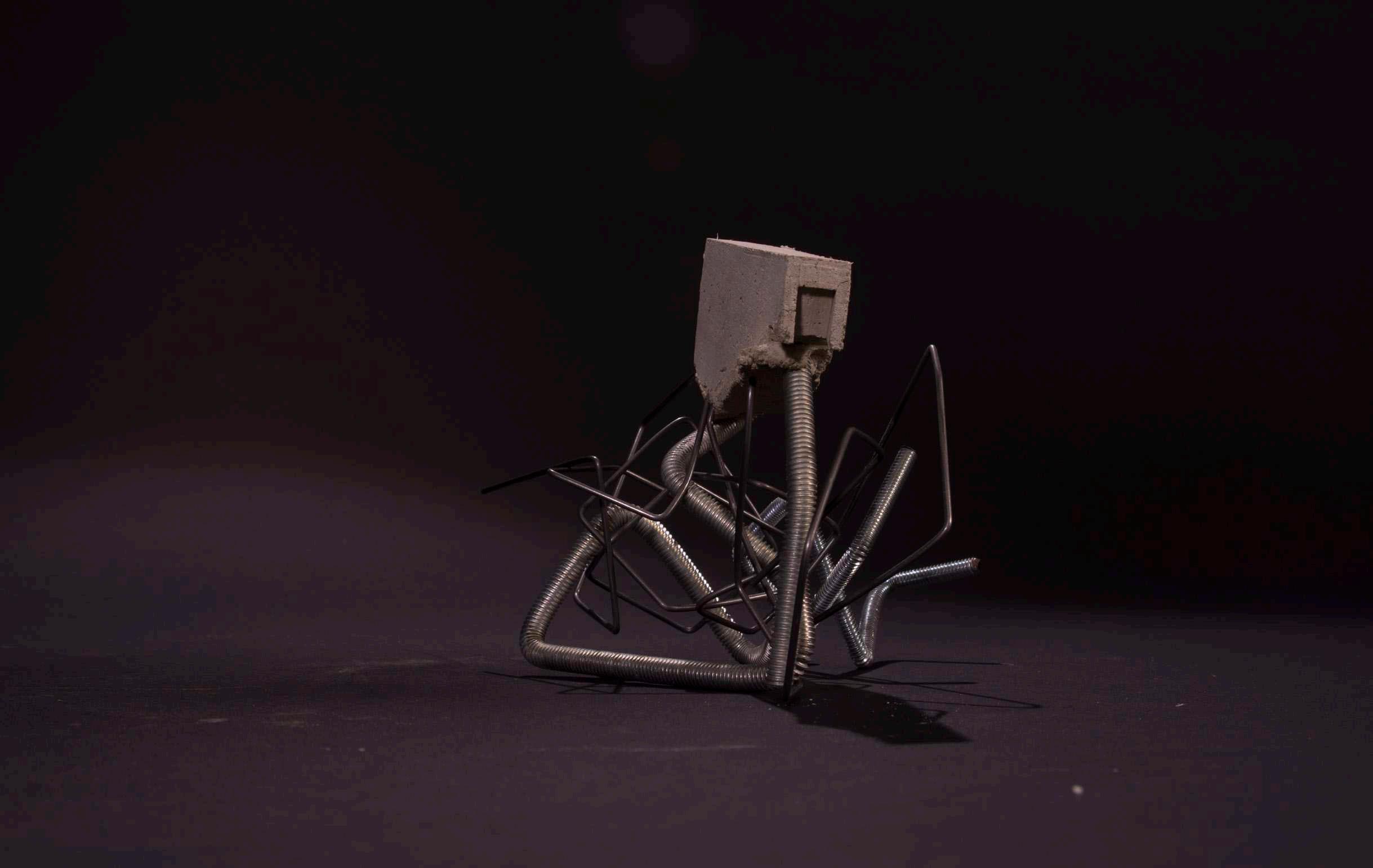

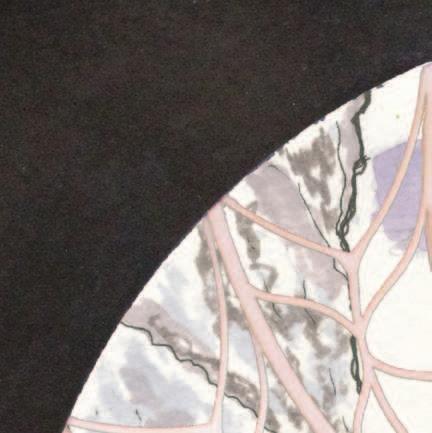

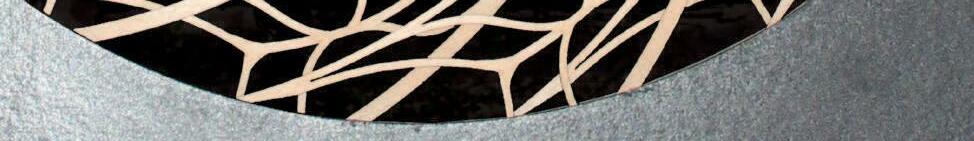

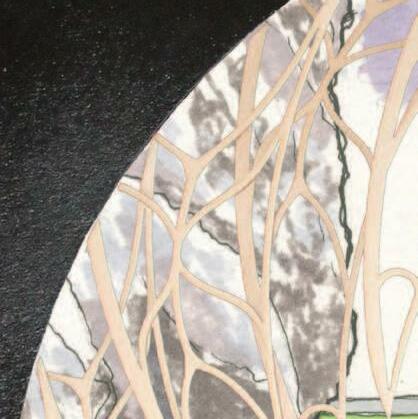

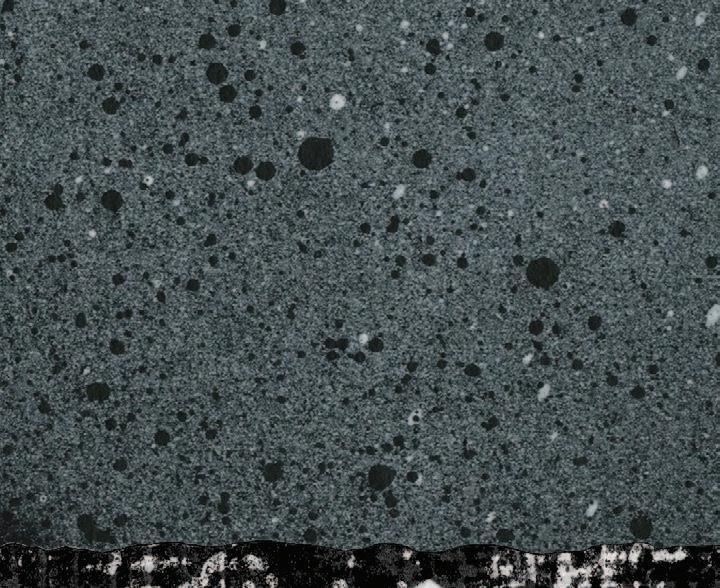

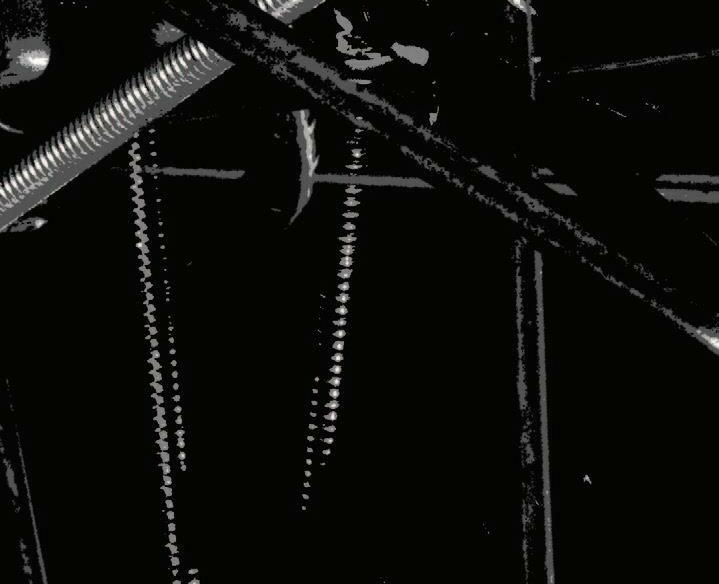

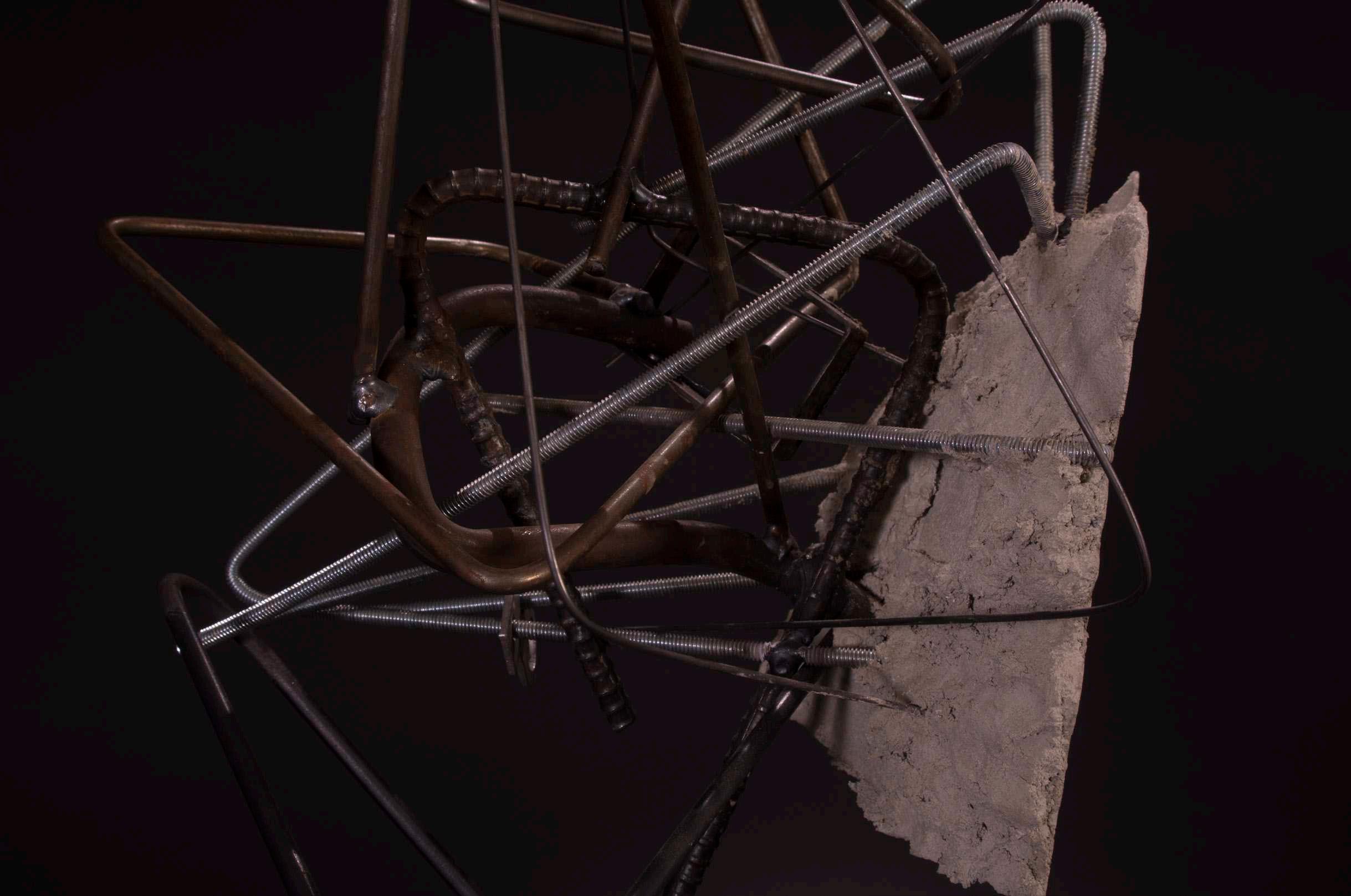

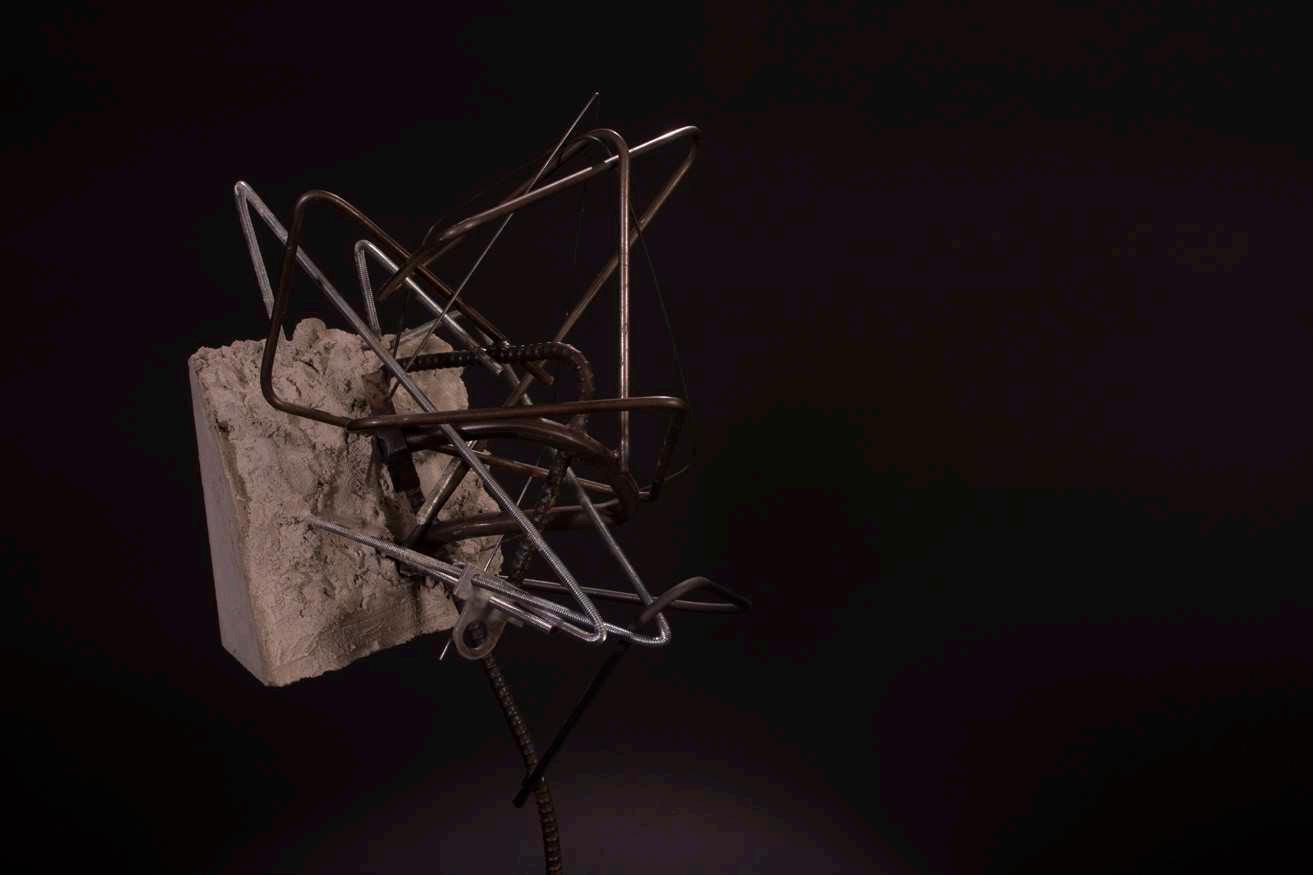

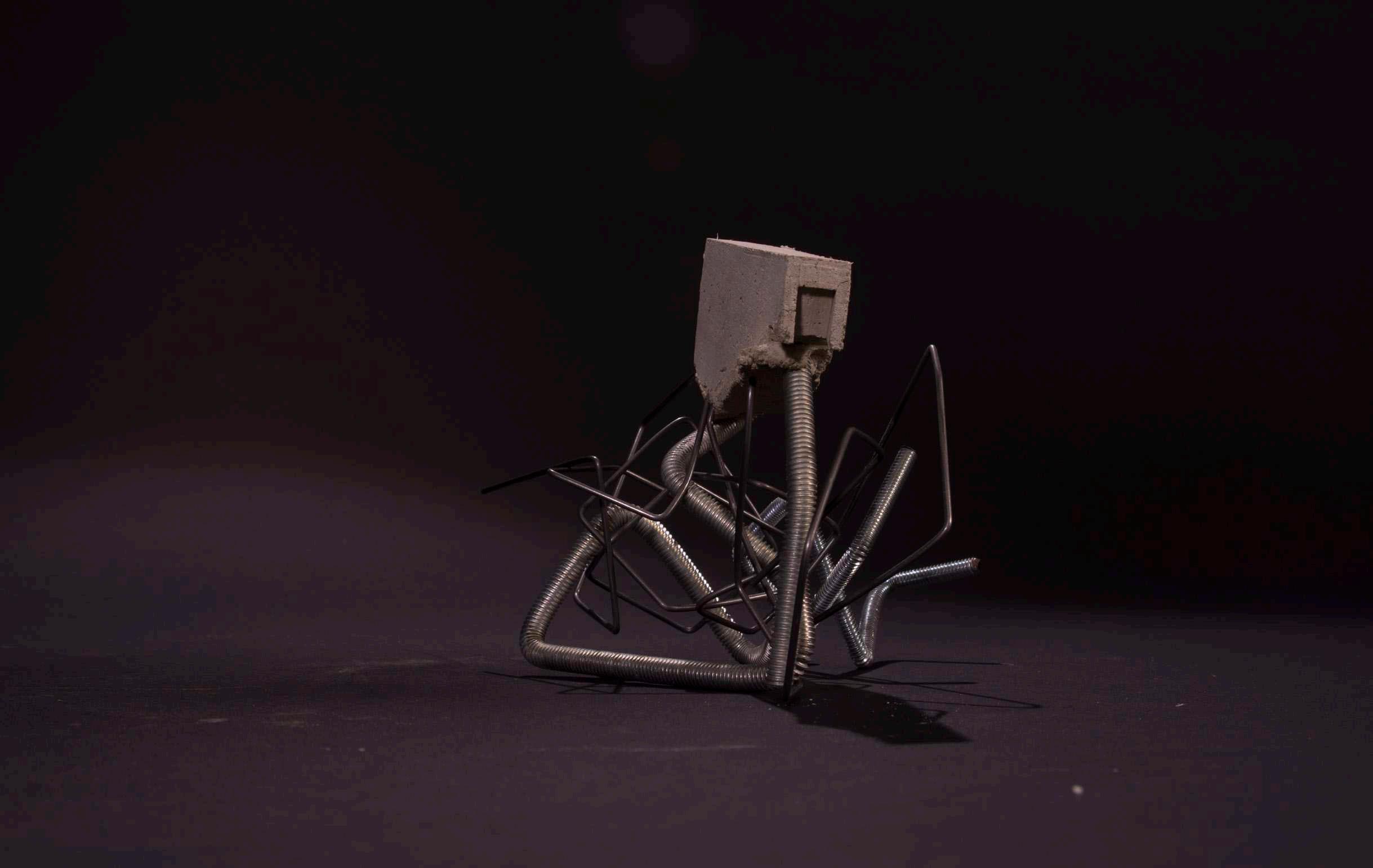

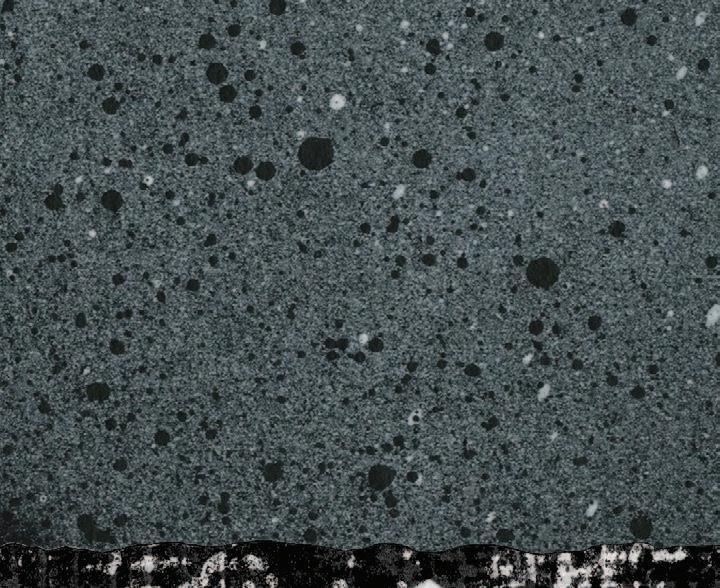

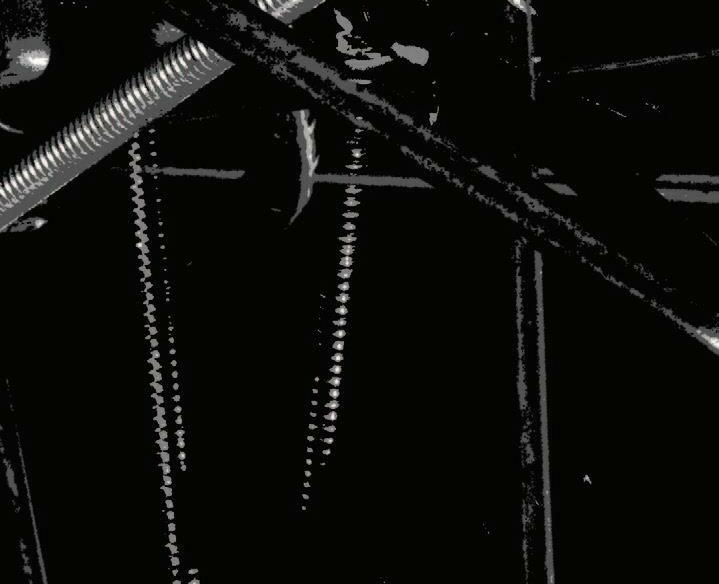

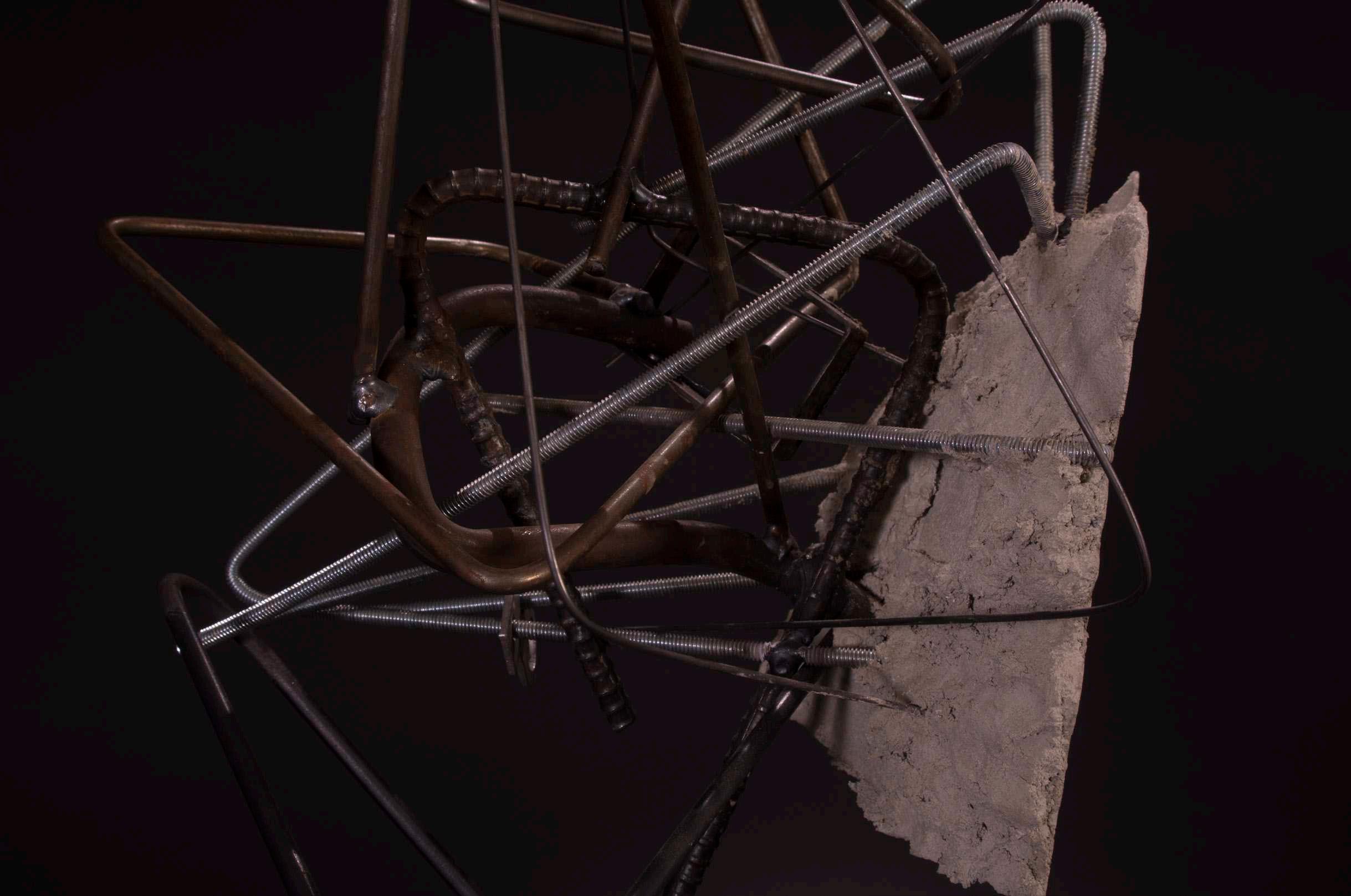

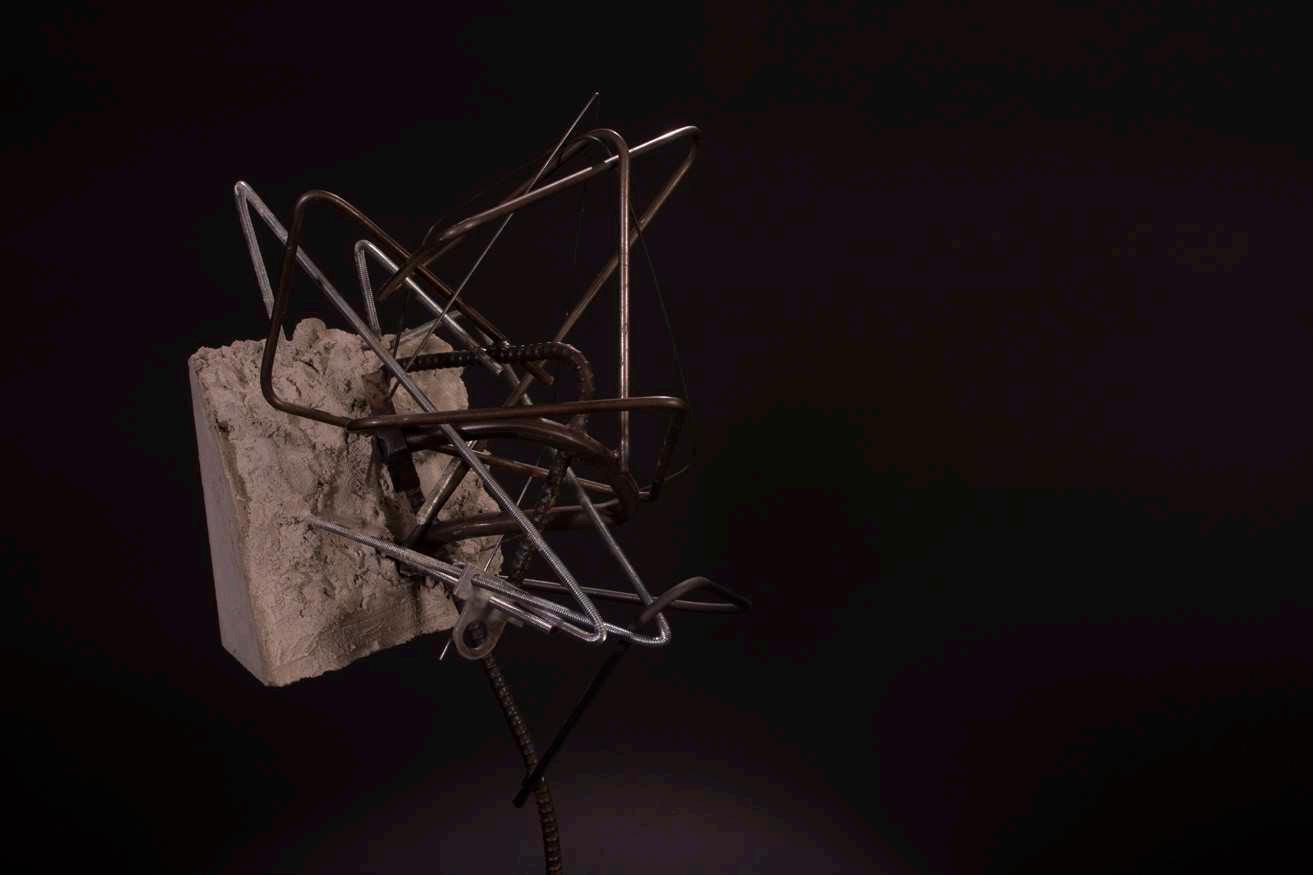

Abstract Sculpture

Evil as a matter of perception. Evil as a dichotomy.

What is evil? What is good? Is there a strict deinition, or rather a luid interpretation depending on the situation? To what extent do good and evil overlap, and how blurred is the line between the two? What differentiates a hero from a villain? Does the concept of evil simply depend on perspective? Can something appear good to one person and evil to another? Or, can the same thing appear good from one angle and evil from another? Who decides which angle is which? Society? The individual? The responsible party? When forced to choose between two opposites, it is easy to see the differences and rank them according to a set standard. But what happens when the distinction between the two blurs as one begins to take on the qualities of the other?

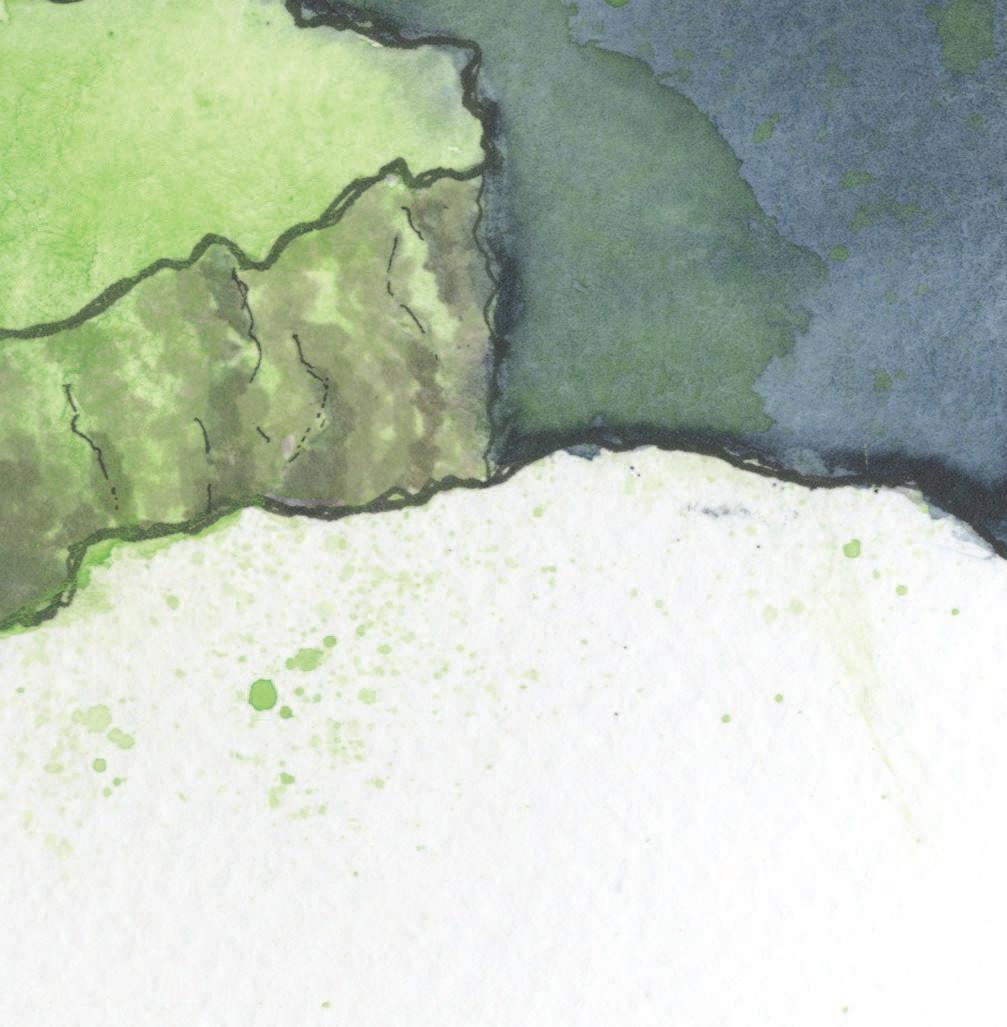

How does one represent the essence of good and evil, capturing the complex and subjective nature of the concepts? By contrasting two materials used in distinct ways, this sculpture seeks to explore the relationship between the

22

concepts of good, evil, and perspective. While the twisted, rusted nature of the metal can represent evil and the smooth face of the concrete can symbolize good, one could reverse these connotations and experience the sculpture in a completely different way. Some may be more drawn to the mass of the concrete, while others may prefer the dark irregularities of the metal. What does this say about their true nature?

Physical perspective—the position of the viewer in relation to the sculpture— changes the interaction and understanding of the piece. From certain angles, the smooth concrete hides the mass of the twisted metal behind. Bits of the pipes sticking out hint at what is obstructed from view, suggesting that there is more than what is currently visible. Similarly, one could look at a villain and merely see the smooth facade presented,yet cracks in the carefully constructed persona can begin to reveal the sinister nature of the individual.

23

24

While the facade of a villain’s lair may appear benign or even relatively normal, the hidden qualities expose a different perspective. Just as the concrete and metal blend together, with the metal supporting the mass, good and evil create a symbiotic relationship—one cannot fully exist without the other—and the line between the two can begin to blur. Are there strict deinitions for the concepts, or are they more subjective? What role does perception play in the determination of where an individual falls on the spectrum of good and evil? This sculpture is intended to provoke the discussion of the duality of human nature, how perspective affects perception, and inspire introspection into the nature of one’s own soul.

25

Perception

Perception is unique to each individual person.

“Every villain is the hero of their own story.” No one truly believes that they are the bad guy, but rather justiies their actions in a way that allows them to see themselves as the good guy. Whether they be serving the “greater good,” establishing a “better world order,” “saving” humanity from itself, or “blessing” the world with a supreme leader, every villain believes that what they are doing is best. In their own mind, they are the hero.

It can be argued that heroes and villains are only deined as such as a matter of perception. Oftentimes heroes must perform morally questionable actions in an effort to thwart the villain. How do these actions differ from the morally questionable actions of the supposed villains? Do the ends truly justify the means? Or are heroes simply villains with pure motives?

Section show afforded the opportunity to gather information on common perceptions of Good and Evil with regard to space and representation. Attendees were asked to rank each section on a ive-point scale from “good” to “neutral” to “evil.” The range of responses supports the idea that the intent of a space depends on the perception of the viewer. The comments section of the survey provided further insight into the reasoning behind the various responses. Some based their perceptions on the connotations of color or contrast, while others found simplicity to be straightforward and “good” in

26

comparison to the deceptive nature of complexity. One viewer thought the third section looked “sciencey,” and that evoked feelings of the unknown, which the viewer associated with evil.

The majority of viewers ranked the irst section as good-to-neutral.

The second section had nearly equal numbers for all ive choices.

The majority ranked the third secion as neutralevil-to-evil.

27

1 2 3

If the concepts of Good and Evil are a matter of perception, this begs the question: what is perception? Perception is “a way of regarding,understanding, or interpreting something; a mental impression.” Perception results from a combination of the internal and external factors that shape the way one thinks and feels about a particular object, event, or situation. The internal factors include personality, disposition, outlook on life, past experiences—essentially everything that makes up who a person is. External factors are directly related to the outside environment. These factors are a little more obvious and are interpreted through our physical senses. No two people have the exact same internal factors; therefore, the external factors will affect each person in a different way, whether those differences be vast or slight. Each individual views the world through a unique lens, shaping the way they perceive something, such as the morality of an action or the qualities and feelings of a space.

“The perception of space can be deined as the process through which one becomes aware of the relative position of their body and the objects around them.”

-Perception of Space Deined

However, the perception of space is more than simple awareness of physical surroundings. Initial judgments that are made as a reaction to that which is immediately received via the senses give rise to emotions and feelings towards the space. As the occupant remains in the space, new judgments often arise. Perception of space is a continual process of discovering the qualities of, as well as one’s own reactions towards, one’s surroundings.

“An interdisciplinary ield that focuses on the interplay between individuals and their surroundings.”

-Environmental Psychology Deined

28

Just as perceiving is more than simply analyzing data, the perception of space is more than simply realizing one’s relative location. In order to understand Architecture,it is crucial to understand how one interacts with that environment. Architecture is designed with a purpose,and that purpose does not and cannot exist without a user. Architecture roots its foundation in sculptural and spatial art; therefore its success relies solely on the individual perceiving it. However, understanding common perceptions of certain spatial qualities gives the designer the power to manipulate the feelings and emotions of the occupants.

29

Impressions of Emotions

Written by Emily Ladeairous

Adapted by Susie Caldwell

“Perception is indeed a very complex process, that involves gathering information through our senses; processing it - which implies analyzing thereceivedinformationandcomparing it against previously gathered knowledge, based on past experiences; and formulating particular responses - also based on previous experiences.

Perceptionisinessenceahighlycreative process: although we relate to the same reality, we will perceive it in a different wayaccordingtowhatthatenvironment meanstoeachof us.”1

30

Architecture creates space and is a therefore a form of art that gives physical form to this concept of perception. In order to design, we must irst understand what perception is—how we can manipulate one’s perceptual experience— and start to delve into what will leave a lasting impression with the user. This conceptual awareness is what begins to shed light on just how powerful architecture is when it comes to deining a space for a user and whether or not a space is performing its intended purpose.

Since perception is such a broad term it is becoming increasingly dificult to deine and will vary across professions:

Experimental Psychology:

-“the manner in which stimuli act upon receptors”

Social Psychology: -“the ability to identify objects within the social environment”

-“the image which the individual forms upon various events, people, objects linked to previous experiences”

Environmental Cognition: -“the whole range of percepts, memories, attitudes, preferences, thus comprising the entire information we pose related to an environment”2

When linking perception to architectural theory it is more dimensional than perception with regard to art. Although in architecture we must also pay attention to color, proportion, light, and shadow, there is more to it than this. There is a process that a user will go through when irst entering a space. We know the architect creates the space that will later be perceived by the user.

1. POP, Dana. “Space Perception and Its Implication in Architectural Design.” Acta Technica Napocensis: Civil Engineering & Architecture 56, no. 2 (December 15, 2013): 211-21.

2. Ibid.

31

The user will initially experience the physical aspects—color, form, material, lighting—then the user will start to understand more dimensions of the space and recognize its function and utility based upon their own past experiences and what he or she has gathered over the course of their lifetime. As a result, every person will perceive a space differently, because no two people have had the same set of experiences or have the same knowledge base. This is why extensive research must be done into a speciic culture for a design to be successful: because the designer’s knowledge base will be different still, yet by expanding that base, he or she can begin to understand how, speciically, the space will be perceived.

“The strength of a good design lies in ourselves and in our ability to perceive the world with both emotion and reason”

-Peter Zumthor

Designers have incredibly speciic intentions when it comes to architecture, yet a vague aspect of design comes down to the way in which every person will react within a built structure. Architecture is so much more to humans than sticks and stones, but rather can be powerfully life-changing, or a place of familiarity, belonging, and comfort, depending on how a person reacts to a space. There is no possible way to design for how every single person will interpret or perceive a space. Therefore architects must do their best to understand a design for a speciic set of people.

In order to have a starting point for a space, such as Evil architecture, one must assume that a majority of people will have something in common, namely similar fears and associations with certain spatial qualities. Usually an architect must do his or her best to have a particular goal or intention for how the space will be perceived, even if in the end some people, undoubtedly, will interpret it differently. Due to the unique nature of every individual person, design can seem impossible. Every person’s entire existence is made up of an complete past consisting of eclectic memories beginning the moment they gained consciousness. How do billions of people from all walks of life get something out of a speciic architectural piece? That depends on their past, their understanding of their own culture, the architect’s grasp on what that culture

32

means, how it is implemented into the design, and inally how the inished project is perceived. While these are all factors in ensuring an architectural piece is successful, architecture will never satisfy 100% of the population, because although it serves a function, it is also an artistic expression, and art is always up for debate amongst people.

Architecture is not meant to be a stagnant structure but rather a multi dimensional experience that utilizes all of our senses and evokes an emotional response in us therefore tying us to a speciic space.

Emotion is the link between architecture and perception—when a building can evoke emotion in someone,it gives a person a sense of place and they can start to understand a space. Architects can take occupants on a journey when they begin to design for the senses—architecture is not solely about what we see,but also what we hear, smell, and feel. The littlest of things can trigger a personal emotion or nostalgic memory for someone, such as a familiar song or scent that can remind one of a previous time in their life or a personal experience. Architecture can work like this, using techniques such as manipulation of light, tactile expression through materiality, patterns and colors, forms, height and width of spaces all can evoke speciic feelings in people.

Designers can use these emotional connections to manipulate the occupants into feeling a certain way. Large, imposing architecture can make a person feel small and insigniicant. Narrow spaces, tilting walls, uneven loors, and strange proportions can create a sense of unease. Twisting, turning pathways that overlap and intersect with no distinguishing characteristics can confuse and disorient those who try to navigate the space.

Diaz, Luis. “Does Design of a Space in a Particular Way Affect User’s Emotions and Feelings?” Quora. June 6, 2012. https://www.quora.com/Does-design-of-a-space-in-a-particular-way-affect-users-emotions-and-feelings. Farooqi, Saif. “PSYCHOLOGICAL ASPECTS OF ARCHITECTURE.” PSYCHOLOGICAL ASPECTS OF ARCHITECTURE. April 9, 2016. Accessed November 25, 2016.

Horan, Deirdre. “Emotional Manipulation Through Spatial Formation (Assignment E).” Wordpress. October 25, 2012. https://deirdrehoran.wordpress.com/2012/10/25/emotional-manipulation-through-spatial-formation-2/.

Lehrer, John. “The Psychology of Architecture.” Wired. April 14, 2011. Accessed November 26, 2016. https://www. wired.com/2011/04/the-psychology-of-architecture/.

33

Need for Control

Everyone has a psychological need for personal control.

34

Control is a fundamental psychological need that must be fulilled. People need to feel as though they are in control of their own lives, otherwise they experience unrest, worry, frustration, and even depression. When lacking a sense of control, people seek to escape the trapped situation that they ind themselves in,rebelling against the system,individual,or circumstance causing the internal tension. Oppressed citizens often insight revolution to overthrow controlling governments, while micromanaged employees harbor resentment and might seek opportunities elsewhere. How can those in positions of power prevent such rebellions?

This need for control can be satisied through two different avenues—power and choice. Power can be deined as the relative control over others or over valued resources1, whereas choice refers to the ability to select a preferred course of action2. Studies show that possession of power affects decision making3 , ability to take action4, focus on personal goals5, and resistance to persuasion and conformity6. Having choice increases positive affect and satisfaction7 and improves task persistence and cognitive performance8 .

1. Magee, J. C., & Galinsky, A. D. (2008). Social hierarchy: The self-reinforcing nature of power and status. Academy of Management Annals, 2, 351–398.

2. Averill, J. R. (1973). Personal control over aversive stimuli and its relationship to stress. Psychological Bulletin, 80, 286–303.

3. Anderson, C., & Galinsky, A. D. (2006). Power, optimism, and risktaking. European Journal of Social Psychology, 36, 511–536.; Inesi, M. E. (2010). Power and loss aversion. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 112, 58–69.

4. Galinsky, A. D., Gruenfeld, D. H, & Magee, J. C. (2003). From power to action. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85, 453–466.

5. Gruenfeld, D. H., Inesi, M. E., Magee, J. C., & Galinsky, A. D. (2008). Power and the objectiication of social targets. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95, 111–127.

6. Briñol, P., Petty, R. E., Valle, C., Rucker, D. D., & Becerra, A. (2007). The effects of message recipients’ power before and after persuasion: A self-validation analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 93, 1040–1053.; Galinsky, A. D., Magee, J. C., Gruenfeld, D. H, Whitson, J., & Liljenquist, K. A. (2008). Power reduces the press of the situation: Implications for creativity, conformity, and dissonance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95, 1450–1466.

7. Langer, E. J. (1975). The illusion of control. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 32, 311–328.; Langer, E. J., & Rodin, J. (1976). The effects of choice and enhanced personal responsibility for the aged: A ield experiment in an institutional setting. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 34, 191–198.

8. Cordova, D. I., & Lepper, M. R. (1996). Intrinsic motivation and the process of learning: Beneicial effects of contextualization, personalization, and choice. Journal of Educational Psychology, 88, 715–730.; Zuckerman, M., Porac, J., Latin, D., Smith, R., & Deci, E. L. (1978). On the importance of self-determination for intrinsically-motivated behavior. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 4, 443–446.

35

Traditionally, power has been viewed as an interpersonal construct (relative dependence on and relative inluence over others9), while choice has been conceptualized as intrapersonal (presence or absence of the ability to select paths and options10).However,new studies suggest that both power and choice satisfy the need for personal control11. A person’s general expectations about whether or not they can control the things that happen to them is referred to as one’s locus of control.12 When a person perceives the results of his actions are contingent solely upon his behavior or relatively permanent characteristics, said person has an internal locus of control. Alternatively, a person could perceive that the results are at least partially, if not mostly, due to chance, luck, fate, circumstance, the actions of a more powerful other, or as unpredictable due to the complexity of the surrounding forces.This individual has an external locus of control. 13 It is the former, internal or personal control, that concerns power and choice.

Research supports the idea that power and choice are sources of personal control; power can convince people of their control over all resources and outcomes, even those determined by chance.14 Choice is not control itself, but rather a source; while the ability to choose establishes a contingency between an individual’s actions and subsequent outcomes15, choice does not always provide a sense of control. Indistinguishable options or extrinsically motivated choices16 can feel limiting or even manipulative rather than empowering.

9. Emerson, R. M. (1962). Power-dependence relations. American Sociological Review, 27, 31–40.; Magee & Galinsky, 2008

10. Averill, 1973

11. Ineis, M. E., Botti, S., Dubois, D., Rucker, D. D., & Galinksy, A. D. (2011). Power and Choice: Their dynamic interplay in quenching the thirst for personal control. Research article. Association for Psychological Science, 1, 10.1177/0956797611413936.

12. Wade, Carole, and Carol Tavris. Invitation to Psychology. Upper Saddle River: Prentice Hall, 2012.

13. Rotter, Julian B. “Generalized Expectancies for Internal versus External Control of Reinforcement.” Psychological Monographs: General and Applied 80, no. 1 (1966): 1-28. doi:10.1037/h0092976.

14. Fast, N. J., Gruenfeld, D. H, Sivanathan, N., & Galinsky, A. D. (2009). Illusory control: A generative force behind power’s far-reaching effects. Psychological Science, 20, 502–508.

15. Zuckerman et al., 1978

16. Botti, S., & McGill, A. L. (2006). When choosing is not deciding: The effect of perceived responsibility on satisfaction. Journal of Consumer Research, 33, 211–219.; Botti, S., & McGill, A. L. (2011). The locus of choice: Personal causality and satisfaction with hedonic and utilitarian decisions. Journal of Consumer Research, 37, 1065–1078.; Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. New York, NY: Plenum Press.

36

Studies show that power and choice can be used interchangeably to satisfy personal control,yet exhibit a threshold effect in their ability to meet this need.17

“Just as people strive to restore control when it is lost or threatened (Roth & Kubal, 1975), individuals who lack power seek to enhance their relative status (Rucker & Galinsky, 2008, 2009), and those whose choice is constrained engage in behaviors aimed at reinstating their freedom (Brehm, 1966; Fitzsimons, 2000).”18

This substitutability hypothesis has roots in studies demonstrating people’s lexibility in utilizing interchangeable means of restoring motivational deicits.19

The threshold hypothesis suggests that “when one source of personal control (e.g., control) is met, additional sources of control (e.g., choice) will provide diminishing beneits, if any at all.”19 People do not strive to maximize their sense of personal control, but rather seeks to maintain an ideal level, following the approach to order20, belongingness21, or meaning22 .

17. Ineis, Botti, Dubois, Rucker, & Galinsky, 2011, 2.

18. Ibid.

19. Ineis, Botti, Dubois, Rucker, & Galinsky, 2011, 2.

20. Kay, A. C., Shepherd, S., Blatz, C. W., Chua, S. N., & Galinsky, A. D. (2010). For God (or) country: The hydraulic relation between government instability and belief in religious sources of control. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 99, 725–739.

21. Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachment as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117, 497–529.

22. Heine, S. J., Proulx, T., & Vohs, K. D. (2006). The meaning maintenance model: On the coherence of social motivations. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 10, 88–110.

37

Various experiments tested the validity of both the substitutability and threshold hypotheses by manipulating either power or choice and measuring the desire for the other, as well as the effects of adding both power and choice on satisfaction with the outcome. The irst four experiments focused solely on the substitutability hypothesis: Experiment 1a and 1b manipulated power and measured the desire for choice,concluding that not only do people in positions of low power prefer a larger choice set, but that they are also generally willing to expend more resources in order to obtain access to said larger choice set. A negative correlation between power and choice was established through an experiment in which participants were assigned positions of either low or high power (mentally establishing this state through memory recall of a high or low power scenario) and asked to choose between larger or smaller assortments of products. Low power participants demonstrated a stronger preference for the larger assortments in comparison to the high power participants.

The willingness to expend more resources in the pursuit of greater choice was demonstrated through an experiment in which participants were asked to decide whether to purchase an item from a nearby (1 mile away) store with 3 options or a store with 15 options that was further away. In a second scenario, the store with fewer options was open and the store with more options was closed, in order to determine how long participants were willing to wait to gain access to more choices. Participants with low power positions were willing to travel further and wait longer than participants in positions of greater power.

Further studies demonstrated that when participants experienced one of the sources, either power or choice, the addition of the other source did not signiicantly increase their satisfaction with the outcome. Thus, one can manipulate others into feeling a sense of control by manipulating the perception of either power or choice. In order to exercise control over others while maintaining their sense of personal control, preventing those with relatively little power from seeking to seize it, one needs only to provide lowpower individuals with a greater abundance of choice. There are, of course, other ways to control those with little power.

38

Control through Intimidation

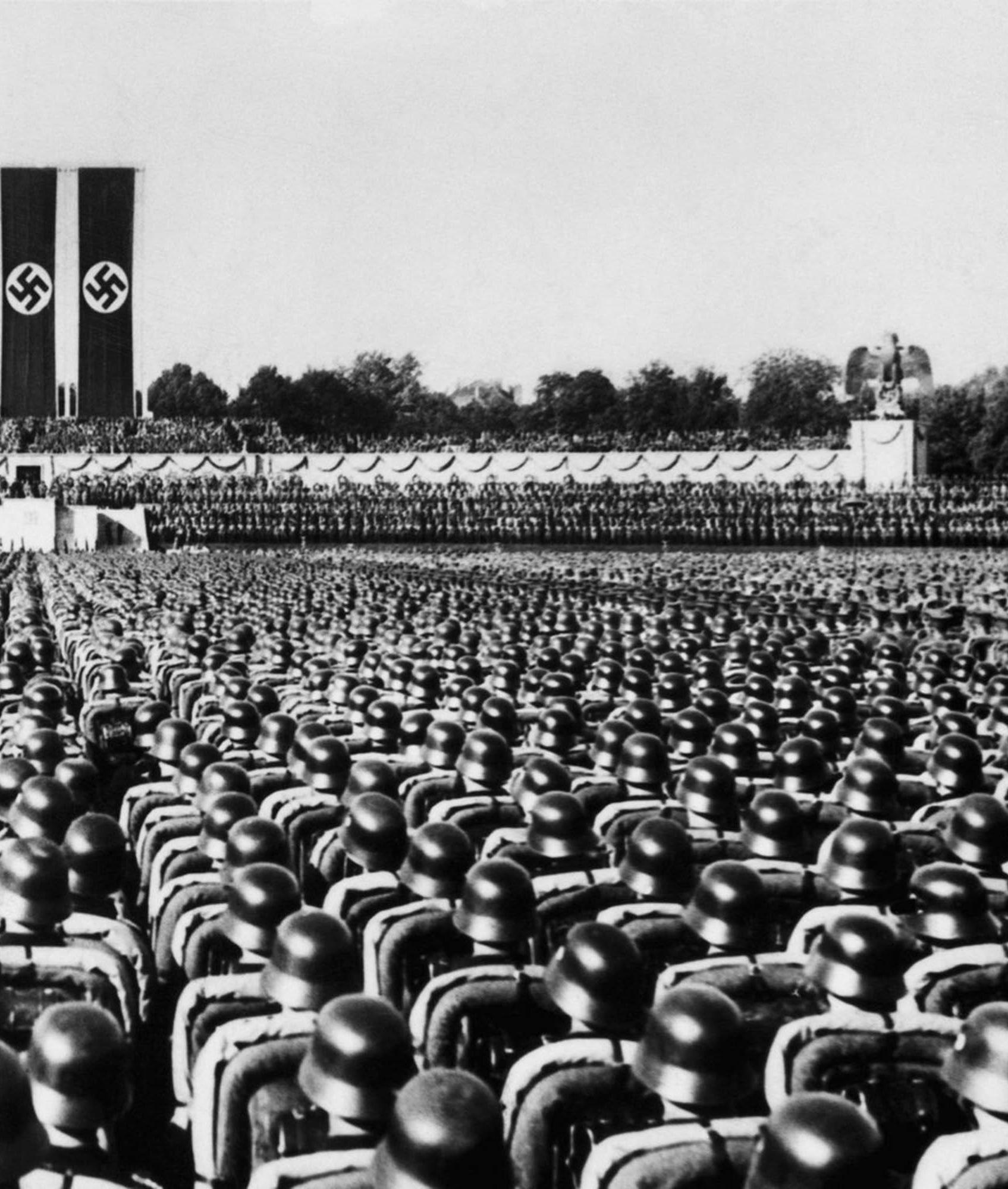

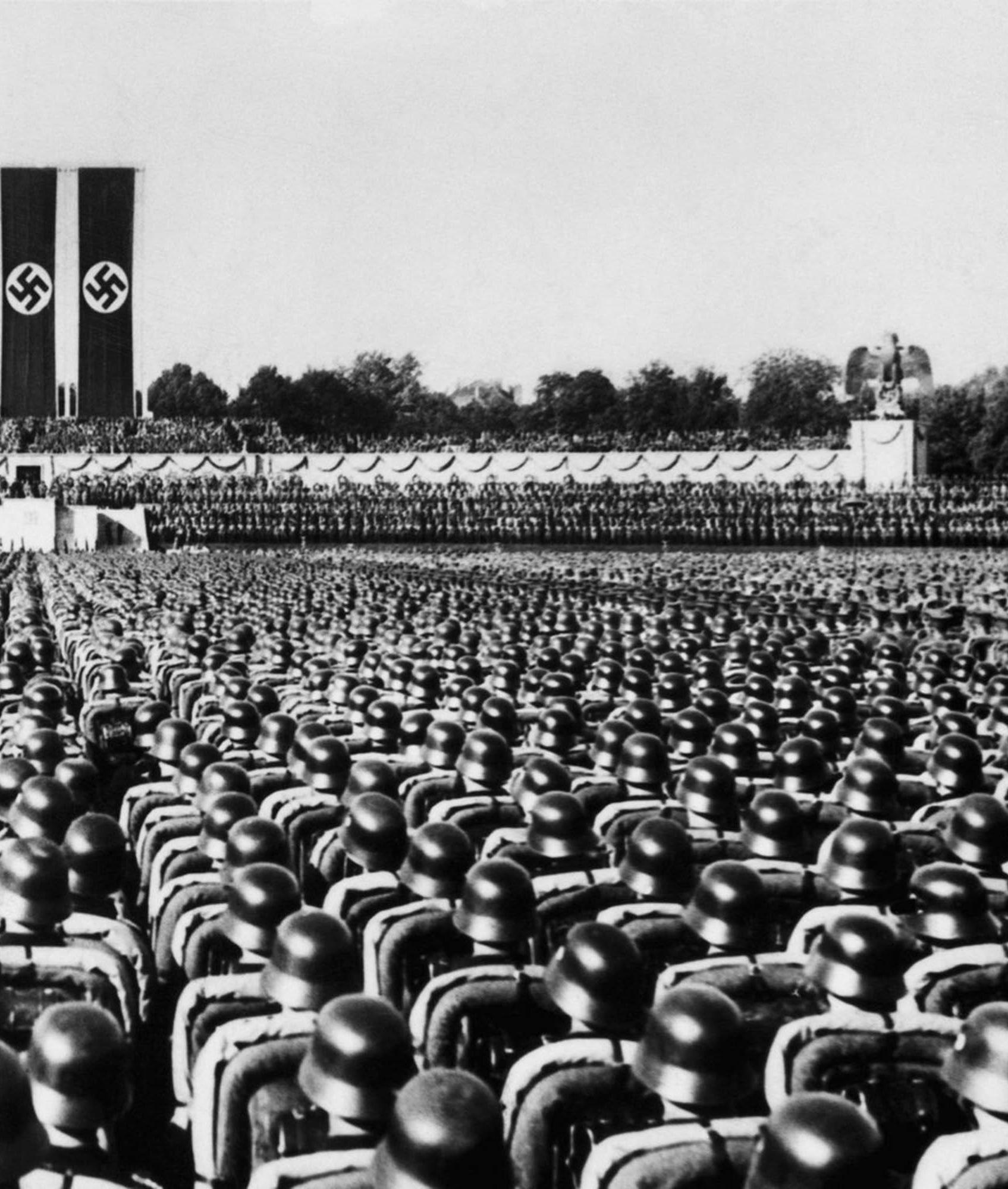

Hitler approached control with his architecture of intimidation. Massive, largescale buildings were designed to display the power and strength of the Nazi party. Perhaps the most inluential individual in realizing Hitler’s architectural vision, Albert Speer, began with the design of the parade ground at the Tempelhof feld rally, at which the new regime wanted to display its power and intimidate its opponents. According to the architect himself,

“We have come to the conclusion that with a ield of 1,000 metres long we must design the stage for the Furhrer’s speech in a way that will make him look particularly impressive to every single person.”

One of his more famous creations: the Cathedral of Light, the Zeppelinfeld stadium for the rally set at night illuminated with a gauntlet of searchlights. Also in Nuremberg, the National Stadium was designed to hold 400,000 spectators and serve as the home for the Olympic games,which Hitler believed would be held exclusively in Germany in the future. Before the start of the war, the congress building was designed exclusively for the speech to 50,000 delegates at the annual party rally. With his eyes on the future of Germany, Hitler proclaimed:

“If God permits poets and singers he has also given us the warriors and the master builders who will ensure that the success of this battle will ind a lasting form in great art. That’s why these ediices aren’t intended for the year 1940 or 2000. Like the buildings of the past, they are to last thousands of years.”23

- Adolf Hitler

23. Hitler’s Henchmen: The Architect Albert Speer. Documentary. Discovery Civilization. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TBWETZYPa5A. Accessed December 2, 2016.

- Albert Speer

39

40

igure 1 // Parade ground. Templehof feld rally. Stage designed by Albert Speer.

igure 1 // Parade ground. Templehof feld rally. Stage designed by Albert Speer.

41

© picture alliance / akg-images

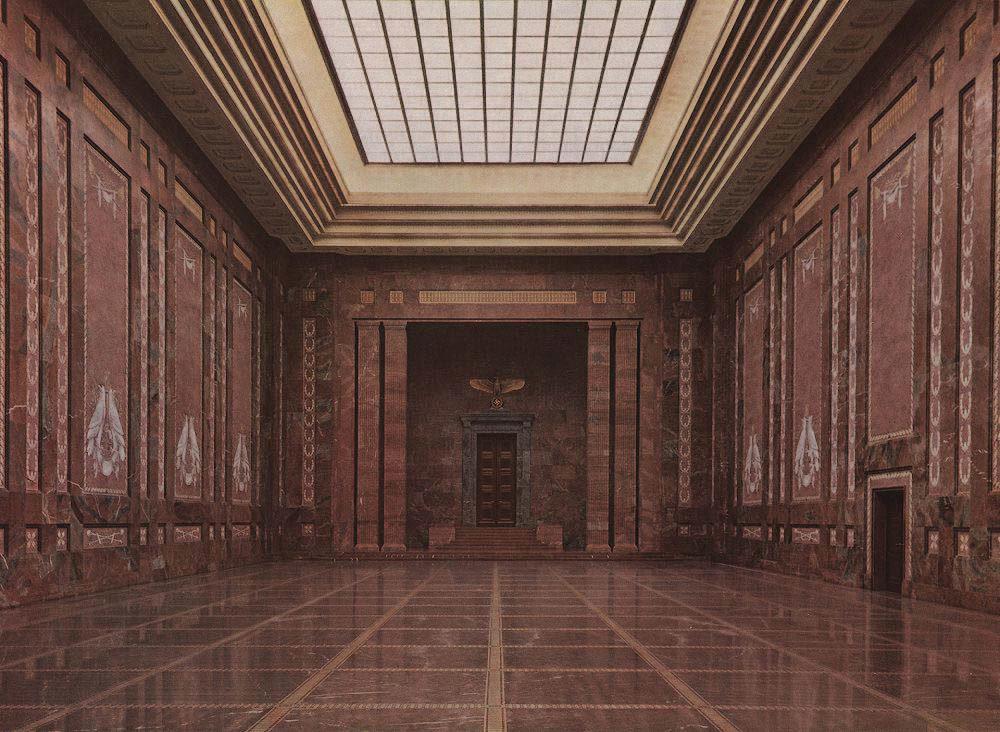

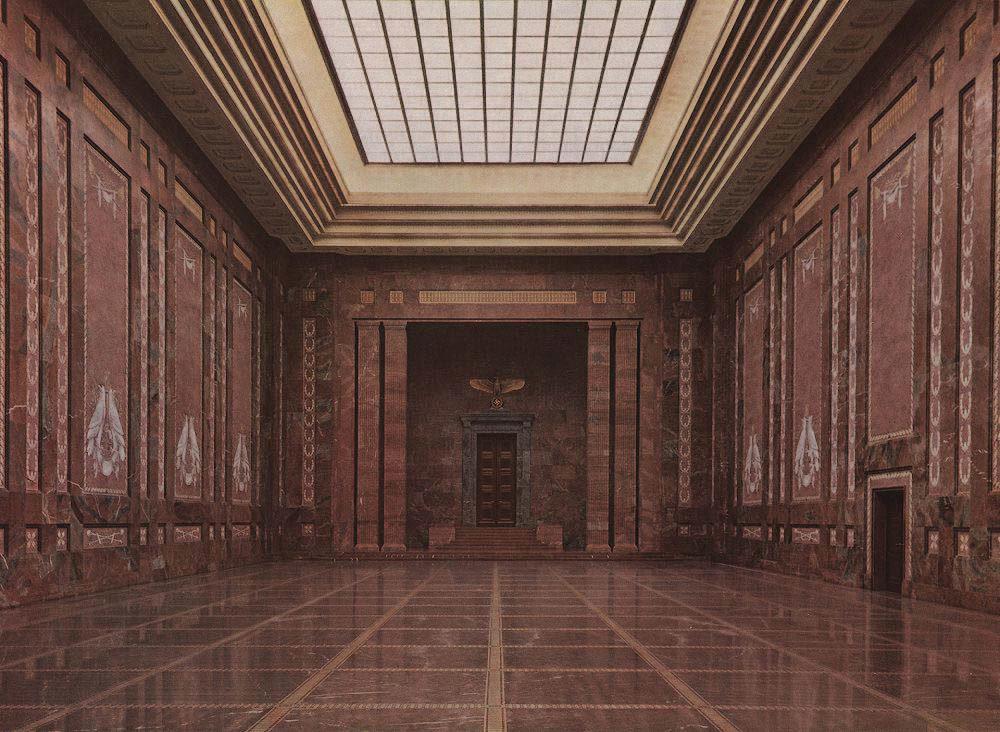

Speer developed a new process of design, the “Law of Ruins,” so that even in decay, the buildings would still be beautiful, “like a temple of antiquity.” Every aspect of Hitler’s regime was calculated to reinforce the strength and pride of Germany. Speer designed the New Reich Chancellory with the speciic intention of intimidating foreign delegates who would visit during Hitler’s New Year’s speech. He asked Speer to design the new capital, Germania, in Berlin. Plans for the grand central square included what would be the largest building ever built, the Great Hall (ig. 3), which would hold 150,000 people. with a dome 16 times larger than that of St Peter’s in Rome.24 Some say that a dome of that size would create its own weather conditions, with breath condensing above and raining down on those inside. Victory columns, gates, and parade boulevards served as reminders of the victory that was to come. Hitler wanted to have delegates from the subjugated peoples to come once a year to “see and marvel.” Through the shear size and widespread application, Hitler sought to reinforce his dominance and demonstrate his national pride through architecture and city planning. After defeating the French in Paris, Hitler changed his plan to destroy the city, choosing to leave it so that it would look “small and pitiful” in comparison to Germania.25

24.

25. Hitler’s Henchmen: The Architect Albert Speer.

figure 2 // Great Hall. Germania. Speer. Plan for the new capital in Berlin.

Roger Moorhouse, “Germania: Hitler’s Dream Capital,” History Today, March 2013.

Roger Moorhouse, “Germania: Hitler’s Dream Capital,” History Today, March 2013.

42

Google Images

igure 3 // Mosaic Hall.

New Reich Chancellory. Germania. Speer. igure 4 // Hitler’s study.

New Reich Chancellory. Germania. Speer. © media-press.tv

43

Photo taken by Hugo Jäger

Control through Destraction

Ratherthancontrollingthepublicthroughdisplaysof strengthandintimidation, those in power can simply distract the masses. The Roman Empire achieved this through the construction of the Colosseum and the implementation of the gladiatorial games. Once a symbol of imperial excess, Emperor Nero Claudius Caesar’s Domus Aurea stood in the center of the city. Opulent to the extreme and covering 100 acres, the Golden Palace marked an era of political greed and self-importance. When Vespasian took power in 69 A.D., he attempted to “tone down the excesses of the Roman Court”26 and focus on the interests of the citizens. In order to give Rome back to the people, Vespasian commissioned the building of a new amphitheater on the site of Nero’s Golden Palace courtyard. Vespasian sought to take a symbol of imperial excess and oppression and replace it with a symbol of imperial generosity and promotion of public welfare, providing a place of entertainment for the citizens of Rome. Titus, son of Vespasian, came to power in 79 A.D. and “oficially dedicated the Colosseum in A.D. 80 with a festival including 100 days of games.” 27

figure 5 // Colosseum. Rome. View of the amphitheater next to its namesake, the statue Colossus Neronis. wikimedia.org

26. History.com Staff. “Colosseum.” History.com. 2009. Accessed April 08, 2016. http://www.history.com/topics/ ancient-history/colosseum.

27. Ibid. 44

The Colosseum was not the irst amphitheater constructed in the Roman world, butitwascertainlythelargest.Over50,000spectatorscouldilltheamphitheater in order to watch the games. Gladiatorial games were a large, all-day spectacle “known as the munus iustum atque legitimum (“a proper and legitimate gladiator show”)”28 consisting of the pompa (morning procession), the venation (wild beast hunt), executions of criminals, barbarians, war prisoners, and other damnati (“condemned”), and inally the gladiators. Spectators had no shortage of entertainment during the periods between the battles, as they were treated to trays of tasty food and tokens for prizes ranging from food to money to housing.

Themaineventofthegamescommandedthemostattentionanditsparticipants gained the most popularity. Gladiators warmed up as attendants prepared whips, ire, and rods to punish unwilling ighters, all waiting anxiously for the editor to signal the commencement of the battle. If a ighter conceded defeat by raising his left index inger, the editor29 would decide his fate. The crowd would express their opinion by shouting “Missus!” (“Dismissal”) for those who fought bravely and deserved to live, and “Iugula, verbera, ure!” (“slit his throat, beat, burn!”) for those who deserved to die. Typically, a thumbs up from the editor signaled life, while a thumbs down signaled death, which gladiators were expected to face unlinchingly at the hand of their opponent.30

28. Mueller, Tom. “Secrets of the Colosseum.” Smithsonian Magazine, January 2011. 29. Person who organized and paid for the games 30. Mueller, Tom. “Secrets of the Colosseum.”

figure 6 // View of the excited crowd focused on the gladiatorial games.

figure 6 // View of the excited crowd focused on the gladiatorial games.

45

Samsung Curved UHD TV Commerical

The games held in the amphitheater were a gift from the Emperor to the people of Rome. In order to pacify the growing population of poor plebs, who had both the power to vote and ability to cause problems in the streets, Augustus focused on public welfare and the supply of food, water, shelter, and entertainment to occupy the people. Augustus realized what author Juvenal famously wrote during the decline of Rome, that:

By supplying the citizens of Rome with food and entertainment, the Emperor couldcontrolpublicopinionandlimitthenumberof internalconlicts.Elaborate gladiatorial games served the dual purpose of demonstrating the wealth and generosity of the Emperor while entertaining the public and providing the opportunity for the common citizens to see their leader in the lesh.

After the rule of Nero,Vespasian sought to restore the reputation of the imperial ofice by returning Rome to the people. The construction of the Colosseum on the site of Nero’s former palace represented a shift from imperial greed to imperial generosity. Rather than spending exorbitant amounts of money in self-service, the Emperor sought to provide public entertainment for the citizens of Rome. Architecturally, the Colosseum is a feat of ingenuity as one of the only freestanding amphitheaters and certainly the largest of its type. Even after its use as an arena for gladiatorial games, the amphitheater continued to provide for the Roman people in various capacities throughout the centuries. The Colosseum continues to attract visitors from all over the world, serving as a symbol of the many accomplishments of the Roman Empire.

46

“the people are only anxious for two things: bread and circuses.”

Another way to quell the possible uprising of the less powerful is to change the public perception of those in power. People are content in positions of low power when they trust those who do hold the power. By choosing who and when they cede control to, one ultimately holds the reins.31 When you like and trust those who have control over you, you are content to keep the status quo. You place your trust in those individuals to make decisions that do not conlict with your own self-interests. Choosing who has authority over you is a way of controlling your life without taking on all of the responsibility yourself. Individuals whose views align with those of the political leaders do not tend to protest or revolt in the way that individuals who disagree with said views. However, these dissenting individuals rarely seek to seize power for themselves as an individual. Rather most rebels seek to replace current leadership with one that more closely aligns with their interests. In doing so, they are choosing a different authority to operate under. They are not putting themselves in the power positions, but still maintain control of their lives by choosing the system and leadership that will operate in the manner that they agree with. Responsibility ultimately lies with those in positions of perceived power, freeing those individuals not in said positions, the apparent low power positions, to carry out more appealing tasks. Leaders do not need to rule through intimidation, but can keep the people satisied through benevolence.

These principles of control can be adapted to interpersonal realtions. In order to satsify those without power, individuals in power positions can provide a wide array of choices or distractions, ensure satisfaction with the power dynamic, or intimidate others into submission. Conversely, the restriction of choice, removal of distraction, and extreme awareness and dissatifcation with the established power dynamic can successfully cause psychological distress.

31. “The Need for a Sense of Control.” The Need for a Sense of Control. Accessed November 27, 2016. http:// changingminds.org/explanations/needs/control.htm.

47

Architecture of Evil

Architecture can beEvil;space can have villainous intent.

The architecture of Evil controls, restricts, intimidates, minimizes, and otherwise inhibits, thus reinforcing the insigniicance of others in comparison to the power and superiority of the villain by exploiting common perceptions of and feelings towards certain spatial qualities.

The architecture of Evil becomes an extension of the villain themself, designed to physically and mentally weaken any potential threats.

The architecture of Evil wholly controls those who enter while giving the false appearance of choice.

The architecture of Evil exploits fears, preying on weakness.

The architecture of Evil provides a false sense of hope,only to allow the intruder to slowly realize that there was never any hope to begin with.

48

What, then, is the Architecture of Evil?

The architecture of Evil relects and ampliies the Evil nature of the villain.

The architecture of Evil protects and caters to the needs of the villain.

The architecture of Evil facilitates the execution of villainous plots.

The architecture of Evil envelops the villain in absolute luxury.

The architecture of Evil inlates the villain’s sense of self.

The architecture of Evil grants the villain total control.

The architecture of Evil empowers the villain.

The architecture of Evil IS the villain.

49

Casa Brutale

50

Architects: OPA SAA (sarkis azadian architects)

Engineering: Arup

Location: Beirut, Lebanon

Size: 270 sqm Budget: 2.5 million USD

Materials: Concrete, glass, wood Mojo: Glass-bottom pool as ceiling Embedded into landscape Stunning view

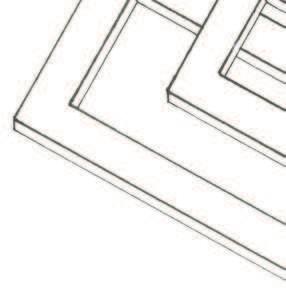

Originally conceptualized as a cliff side dwelling overlooking the Aegean Sea, Casa Brutale synthesizes the modern style and ideal location of a typical villain lair. Hailed as a residence it for James Bond, this sensational building inspires the imagination and elicits tremendous response. As an underground, cliff side dwelling with a simple material palette, Casa Brutale demonstrates how to focus on the interaction of light, shadow, and texture paired with bold gestures such as a grand entrance, secret rooms, and eye-catching glass-bottom pool.

51

Images courtesy of OPA / Terpsichori Latsi (LOOM Design)

52 Architects: Kois Associated Architects Principal architect: Stelios Kois Project leader: Nikos Patsiaouras Design team: Filipos Manolas, Gaby Barbas, Giannakis Konstantinos Location: Tinos Island, Greece Size: 198 sqm Year: 2013 Mojo: Ininity pool roof Disappears into landscape Mirage

Concerned with visibility and privacy, the clients requested a solution that would grant access to the panoramic view while remaining hidden from sight. To accomplish this, Kois designed the residence to disappear by mimicing the surrounding landscape. Dry stone walls reference the traditional walls across the isalnd, while the rimless ininity pool act as an extention of the Agean Sea and relects the surroundings, rendering the building virtually invisible. Taking a Doric appraoch, the program includes only the elements necessary for a comfortable stay. A large portion of the residence is buried into the landscape, with the large outdoor living room overlooking the sea, shaded by the pool above.

Image courtesy of Kois Associated Architects

Image courtesy of Kois Associated Architects

Pionen, White Mountain

Architects: Albert France-Lanord Architects

Location: Stockholm, Sweden

Size: 12,900 square feet; 100 feet underground Year: 2008

Mojo: Repurposed Cold War Bunker Carves out natural rock to form spaces

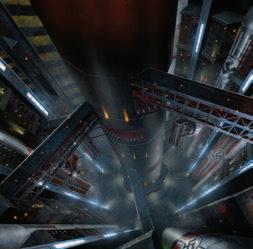

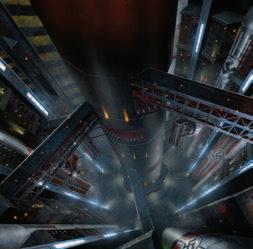

This data center houses the server rooms and ofices for internet provider Bahnhof. The cave-like interior, in conjunction with materials and lighting, create an eerie, sinister atmosphere. Plants throughout the underground spaceaddtothiseffect,seeminglyoutof place.Asaresultof theconstruction method, namely the blasting out of rock, the spaces are irregular and organic, mimicking natural caves.

54

Images courtesy of Bahnhof

Images courtesy of Bahnhof

Lair Locations

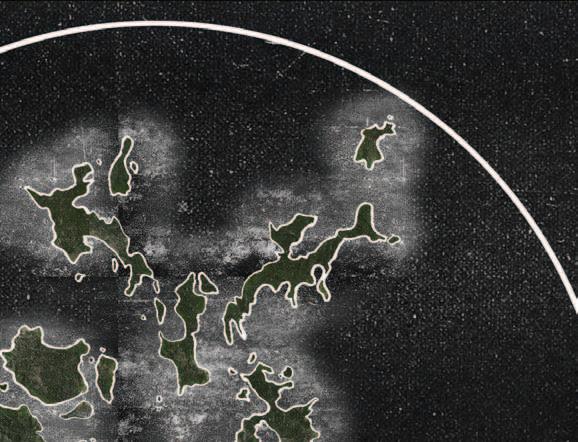

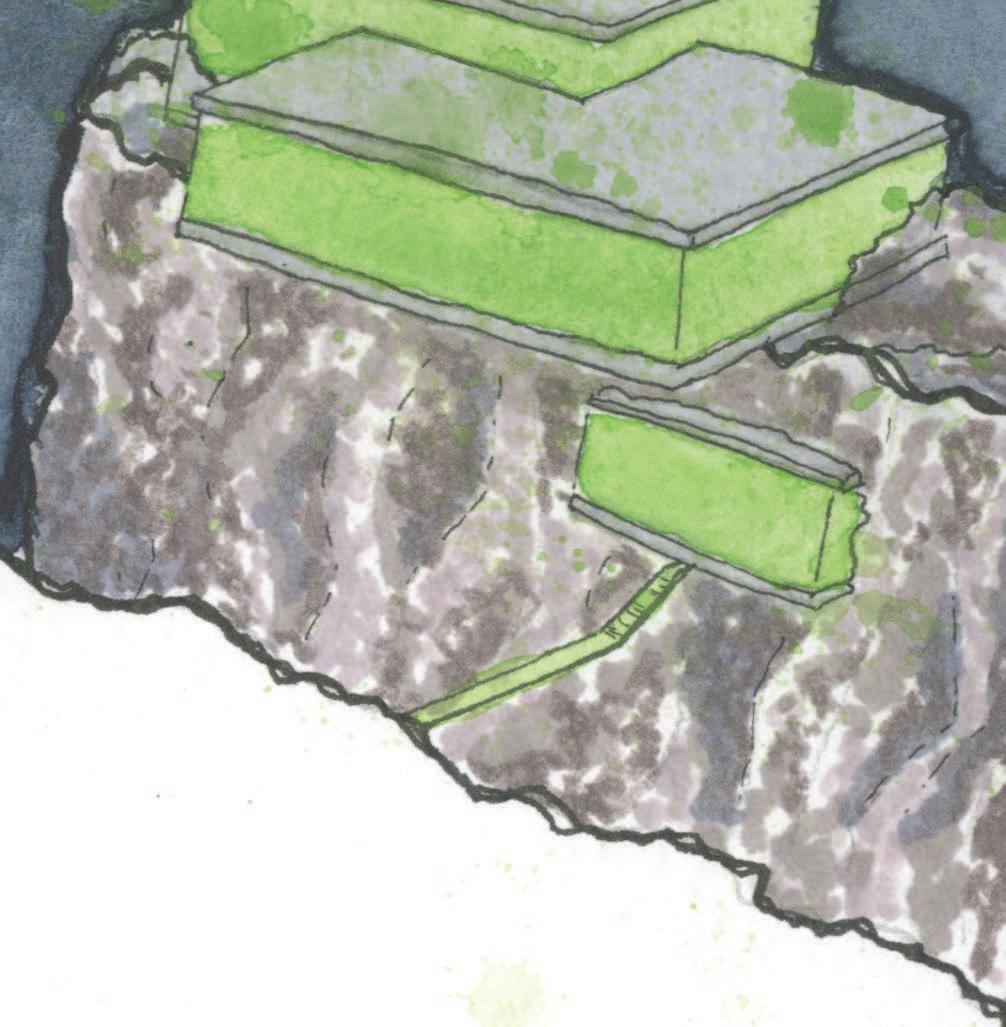

Villain lairs are as varied as the villains themselves, ranging from secluded hideoutstocentrally-locatedmetropolitan penthouses to mobile command centers. This site map highlights a number of possible locations, including ancient ruins, embedded into a volcano or rainforest waterfall, or even underwater. Each location offers different advantages and comes with unique considerations. For this thesis, a hard-to-reach cliffside in a remote European location serves as the site for the villain lair.

56

57

Image courtesy of Google Images

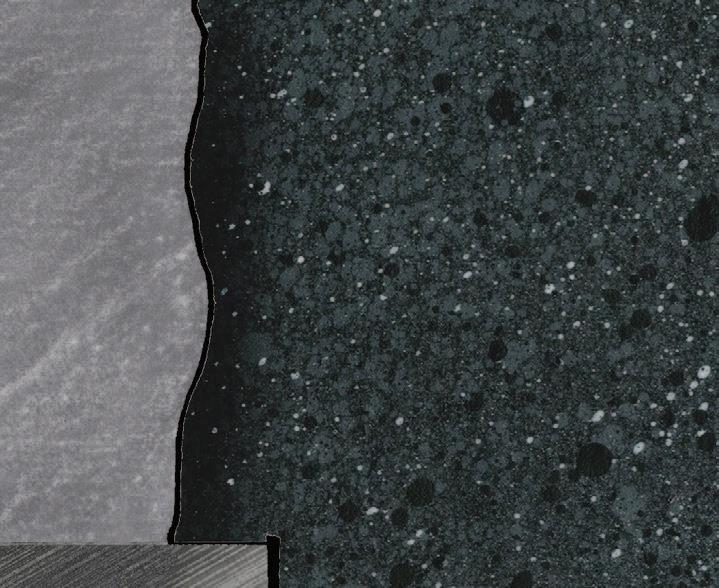

Everyvillainseekingworlddominationneedsalairthat satisies two essential needs—privacy and protection. Only a grandiose, exotic, out-of-reach hideaway will do—somewhere far from prying eyes to allow for overthe-top, resplendent extravagance. An isolated cliff side with stunning views of the sea provides for these needs. An effective lair must be set on a site that acts as an obstacle an psychological barrier that one must overcome in order to access the villain. The obscurity and mystery of the villain lends itself to the symbiotic relationship between architecture and inhabitant qualities of one attributed to the other until the two become synonymous. By residing where the danger is, the villain becomes danger itself. Brutal, massive, destructive—the villain alone has tamed the power of nature that poses a threat to any who dares approach. A workplace beitting a true villain must be perfectly positioned, isolated enough to prevent accidental discoverybyunwantedvisitorsyetpreciselylocatedto launchanattackaimedanywhereintheworld.Dificult to locate, harder to access, and easily defensible. For a villain, traditional practicality is not a concern—there is no luxury too extreme. Any inconvenience created by the isolation can easily be overcome with the right amount of money and power. What is truly important is security that feels like freedom.

58

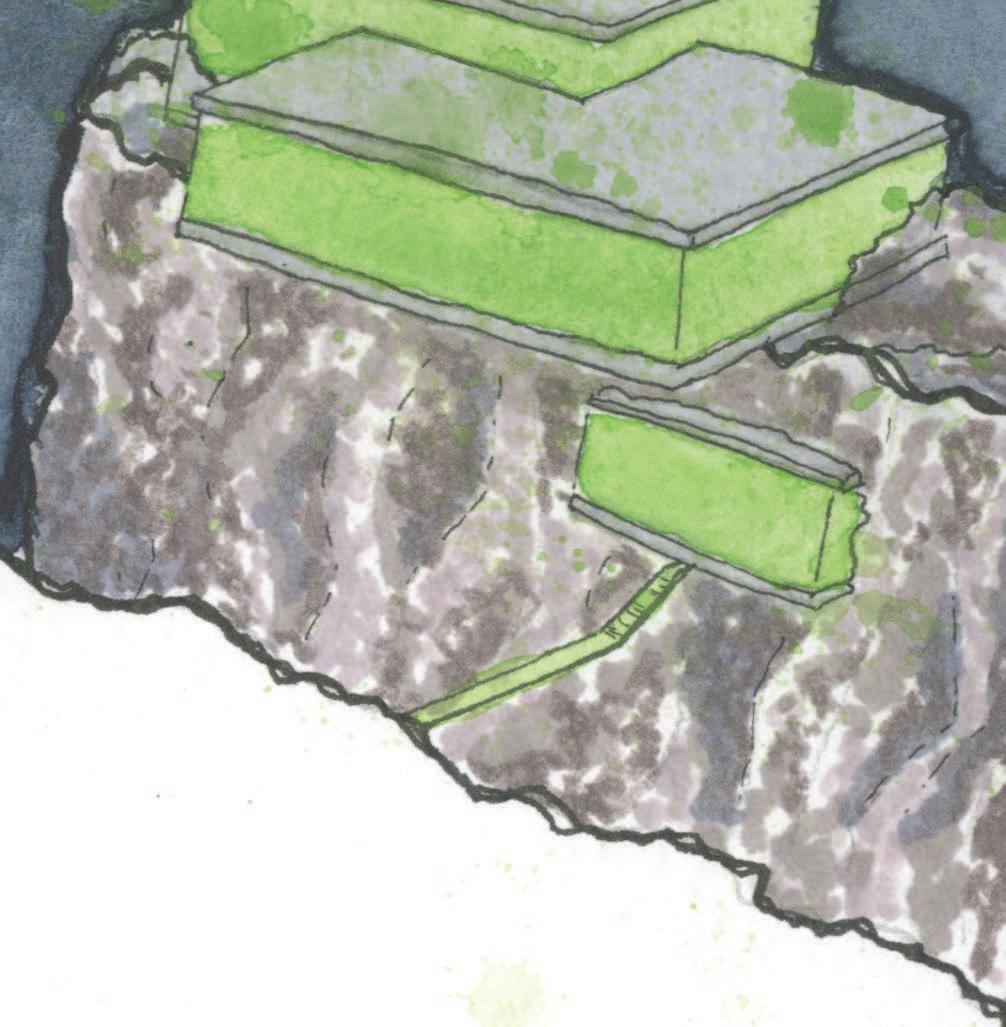

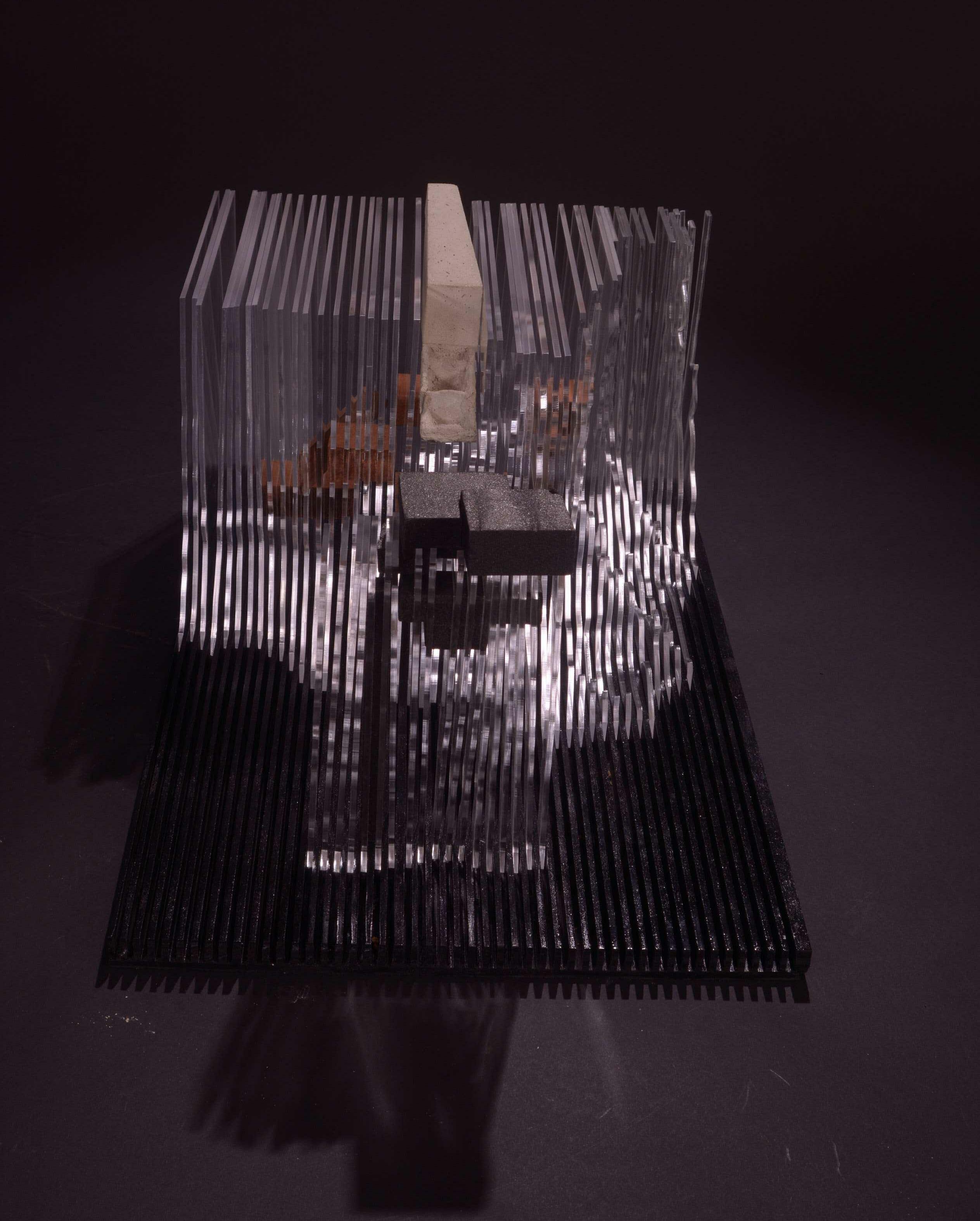

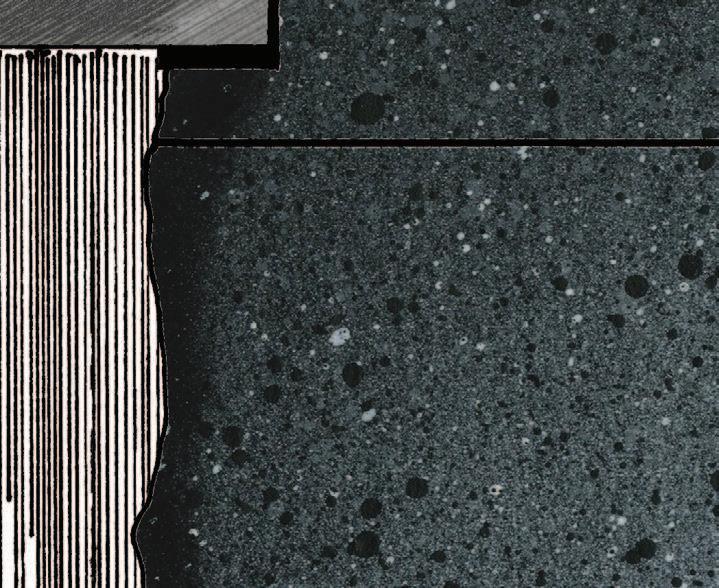

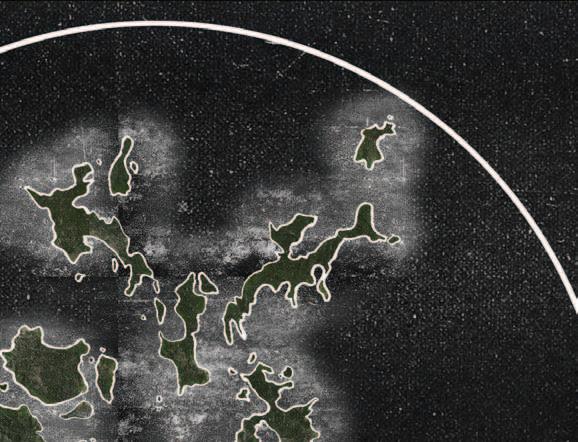

Roughly based on the topography of the islands of Orkney, located in northern Scotland, the lair sits 200 ft above the ocean, connecting cliffside to island with a 150 ft glass bridge.

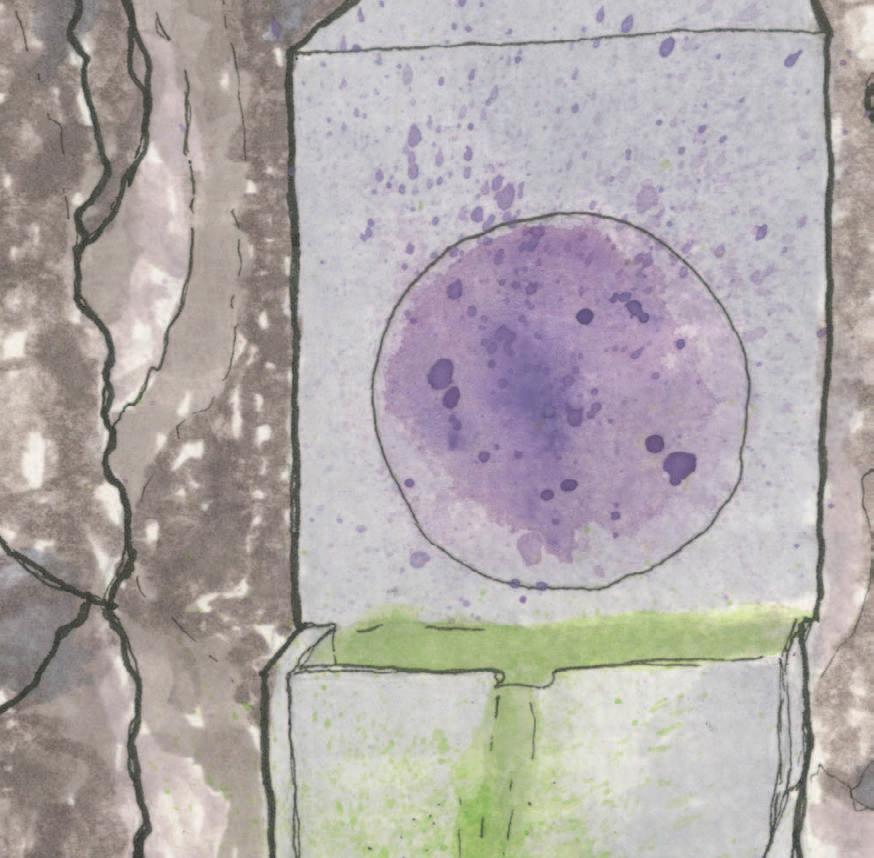

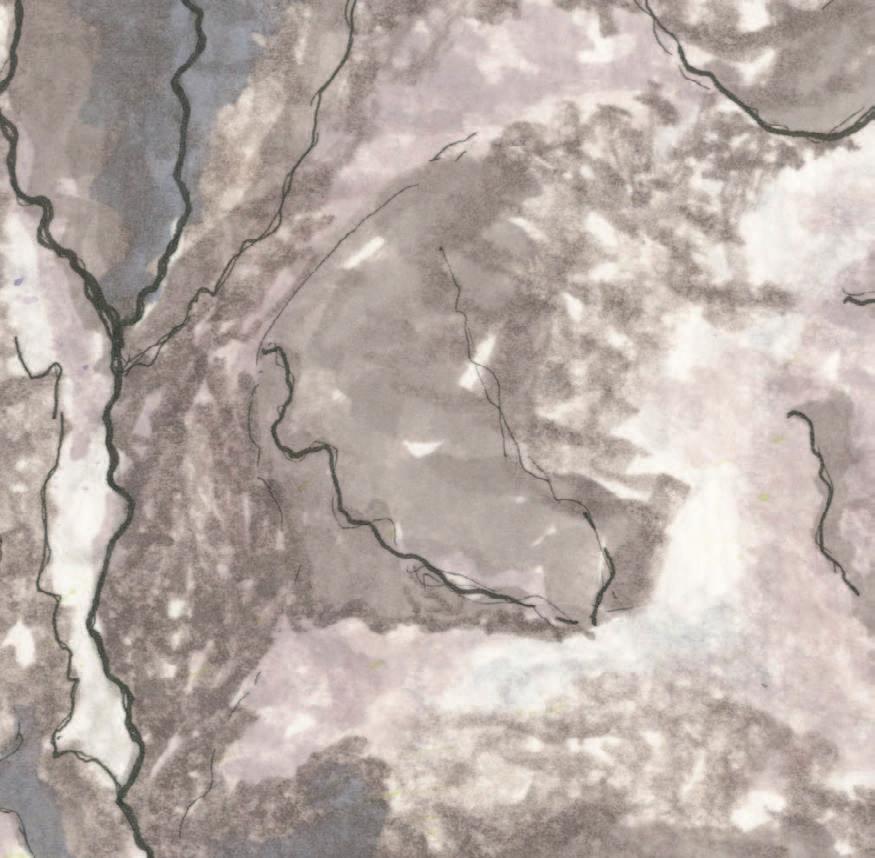

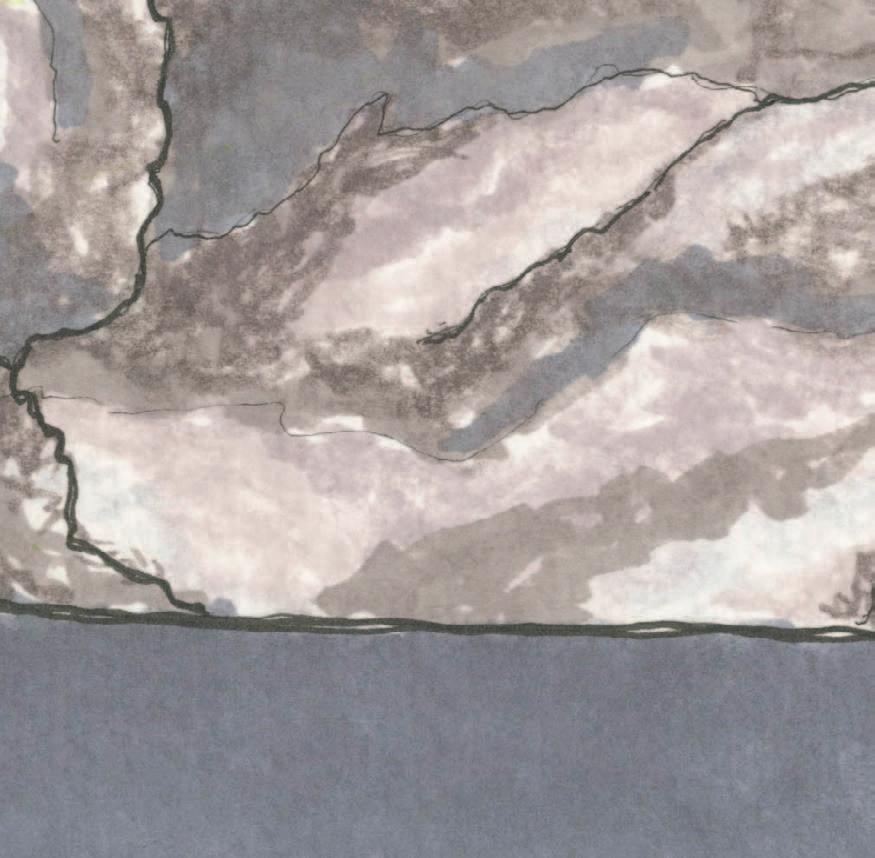

59

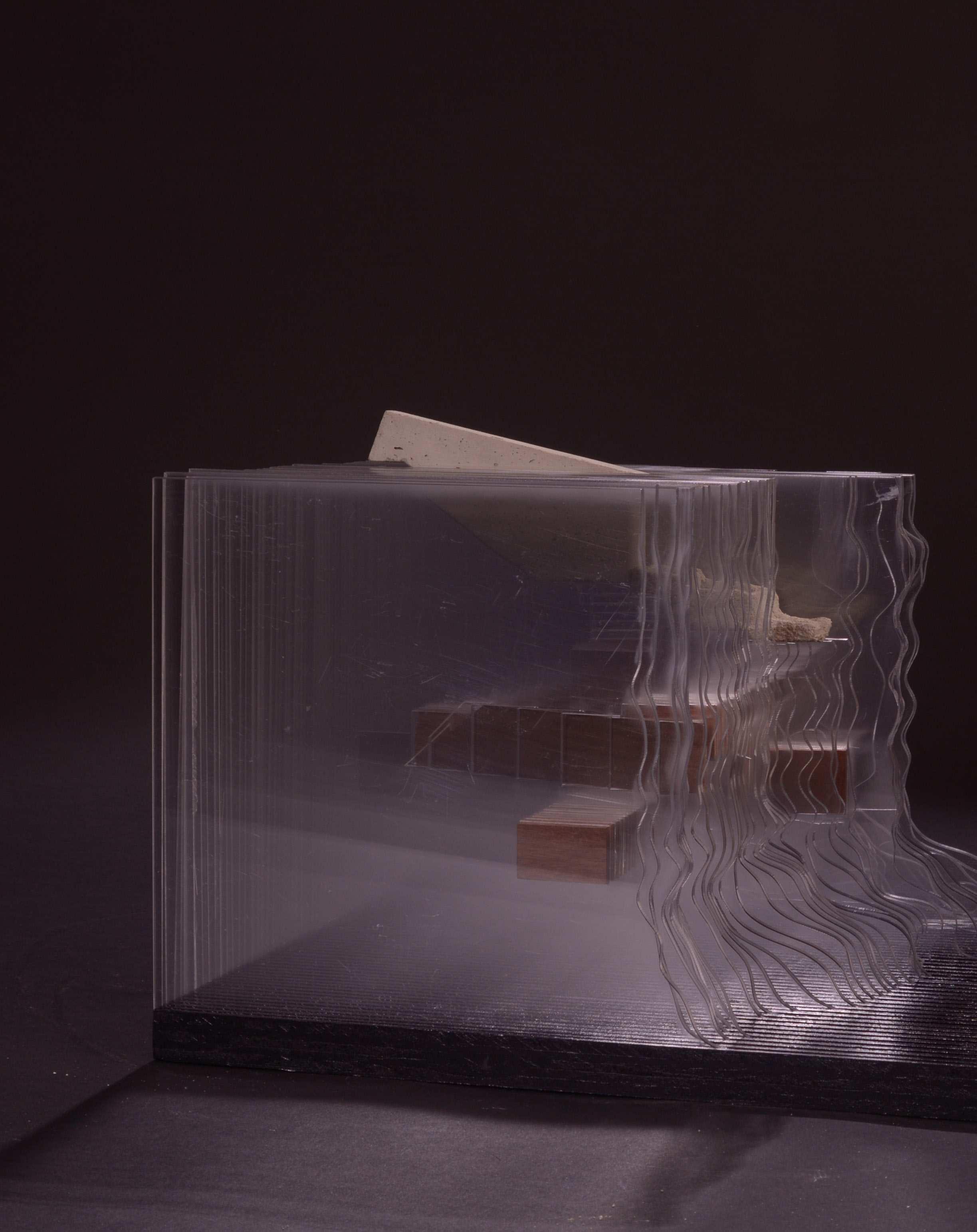

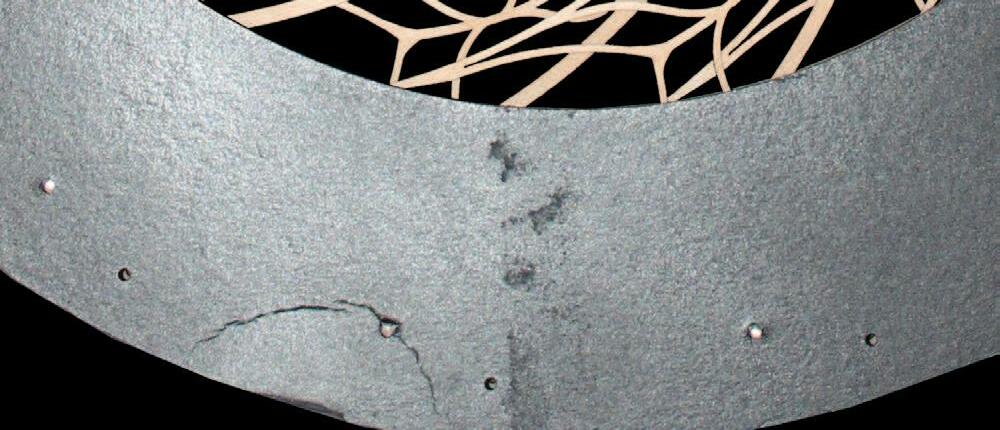

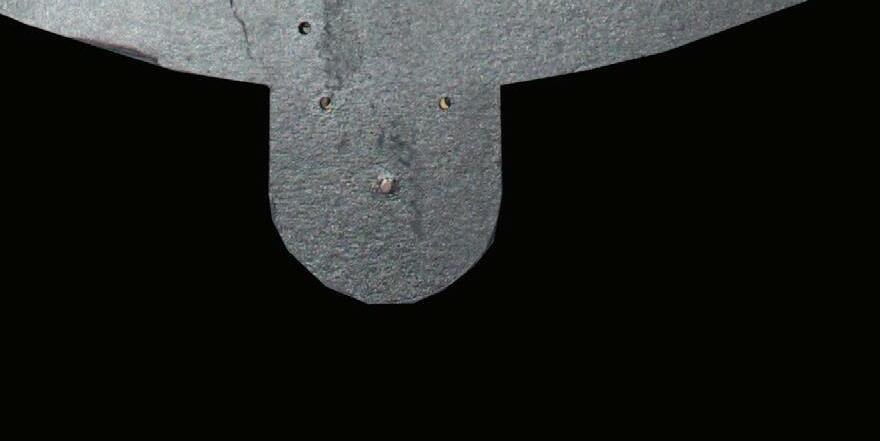

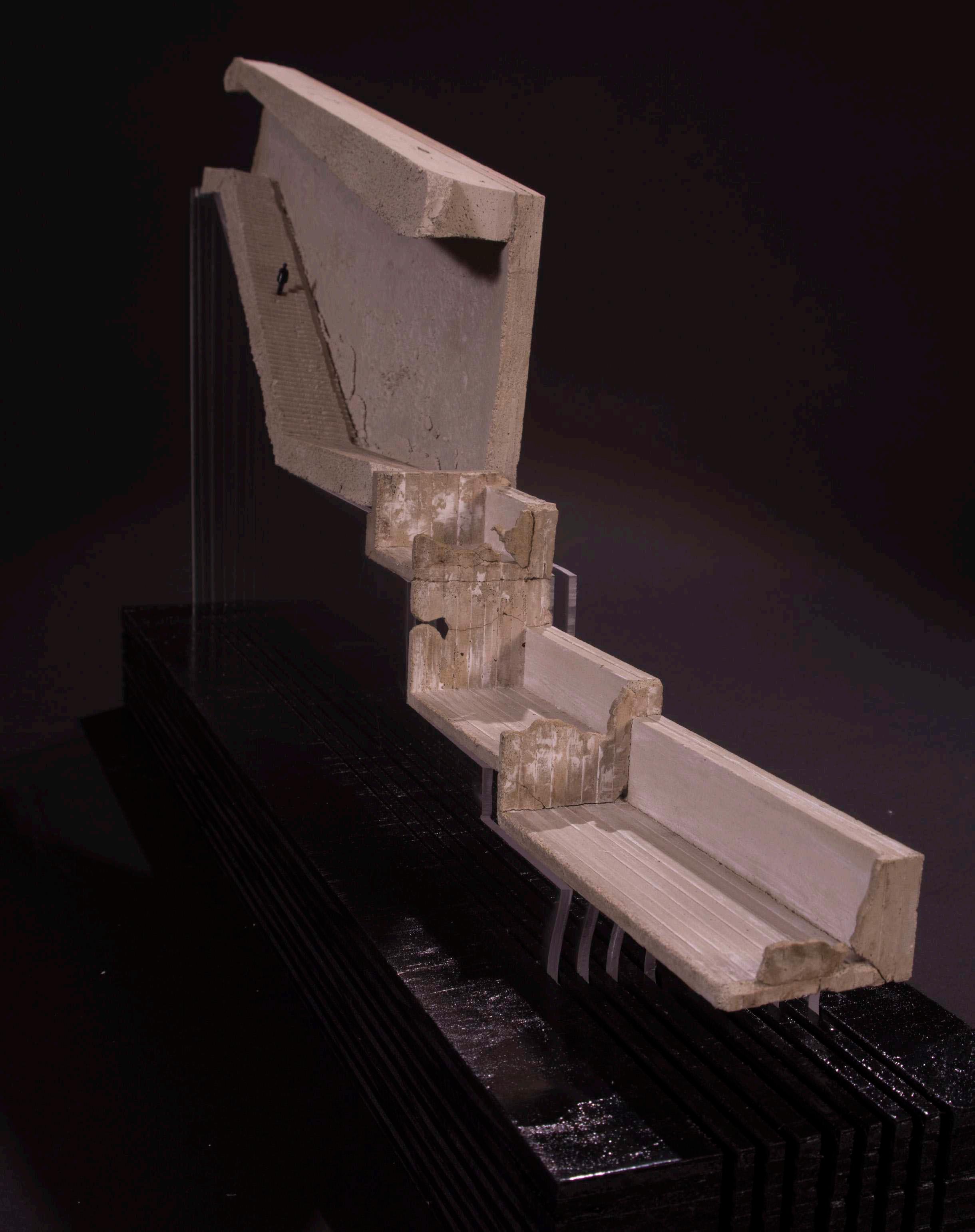

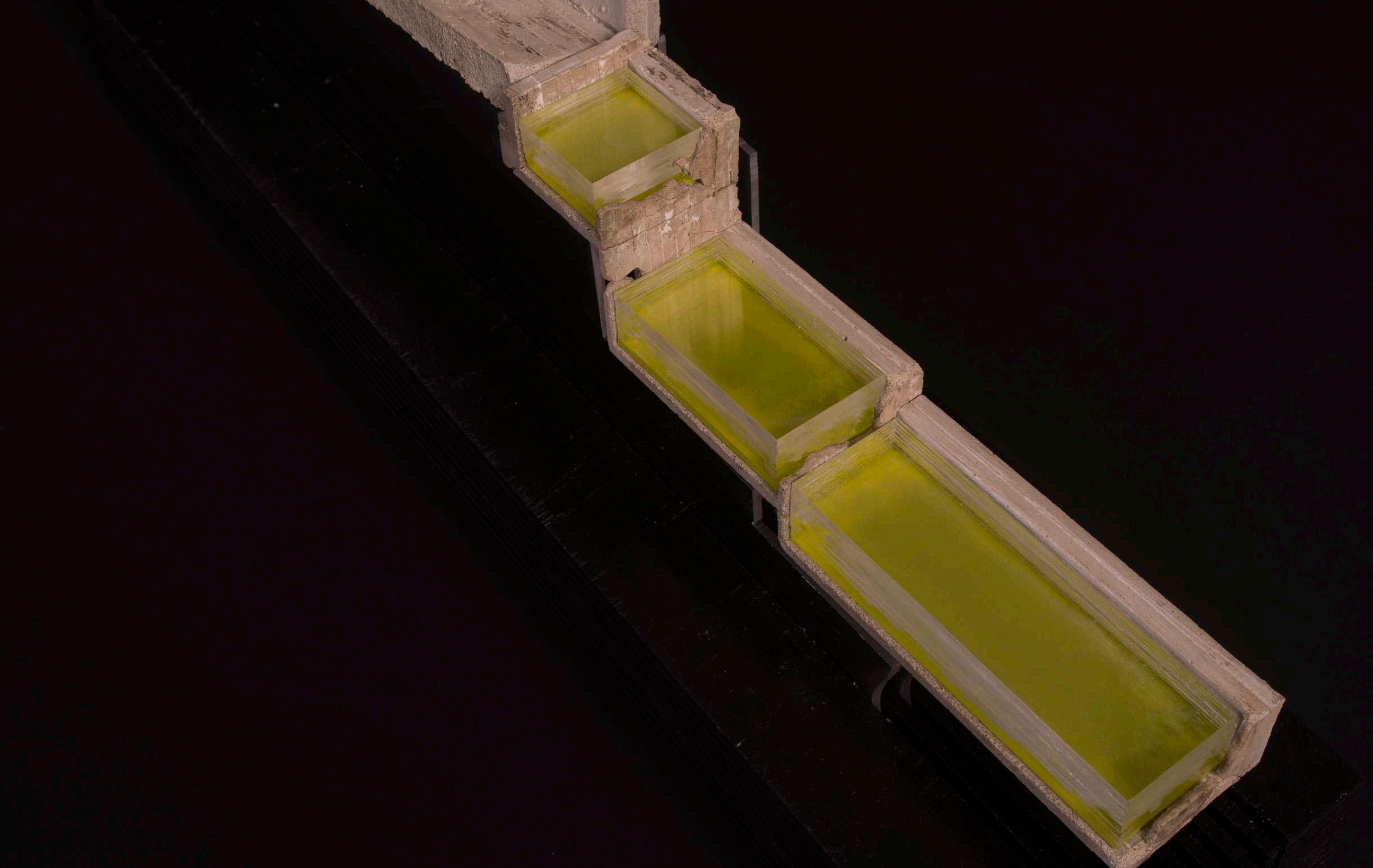

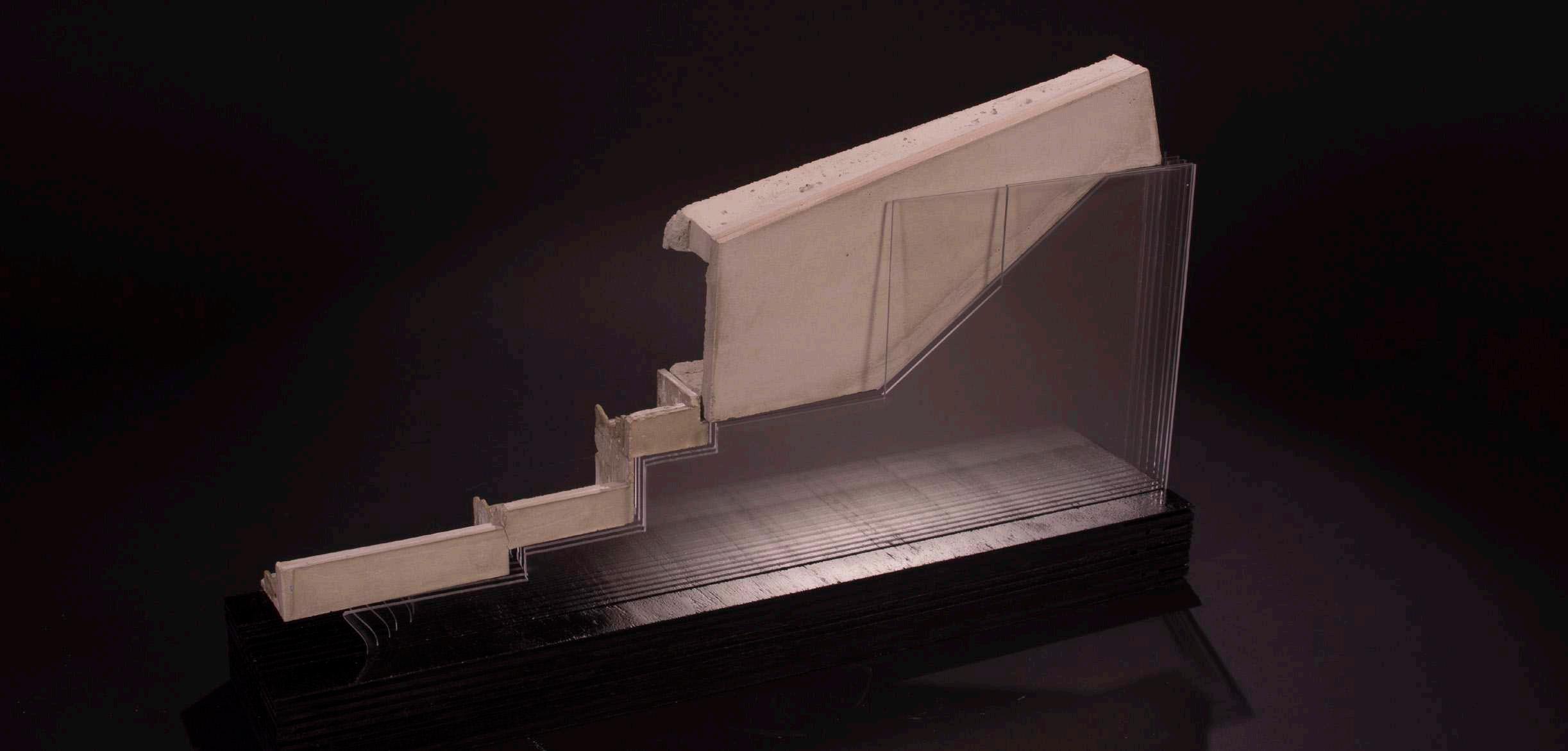

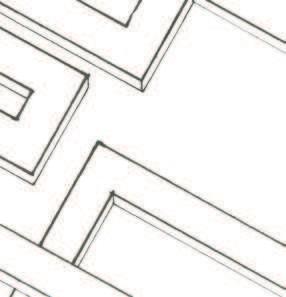

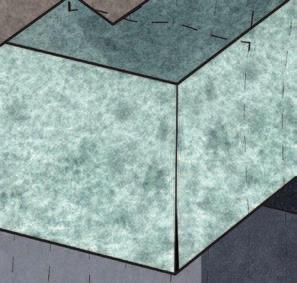

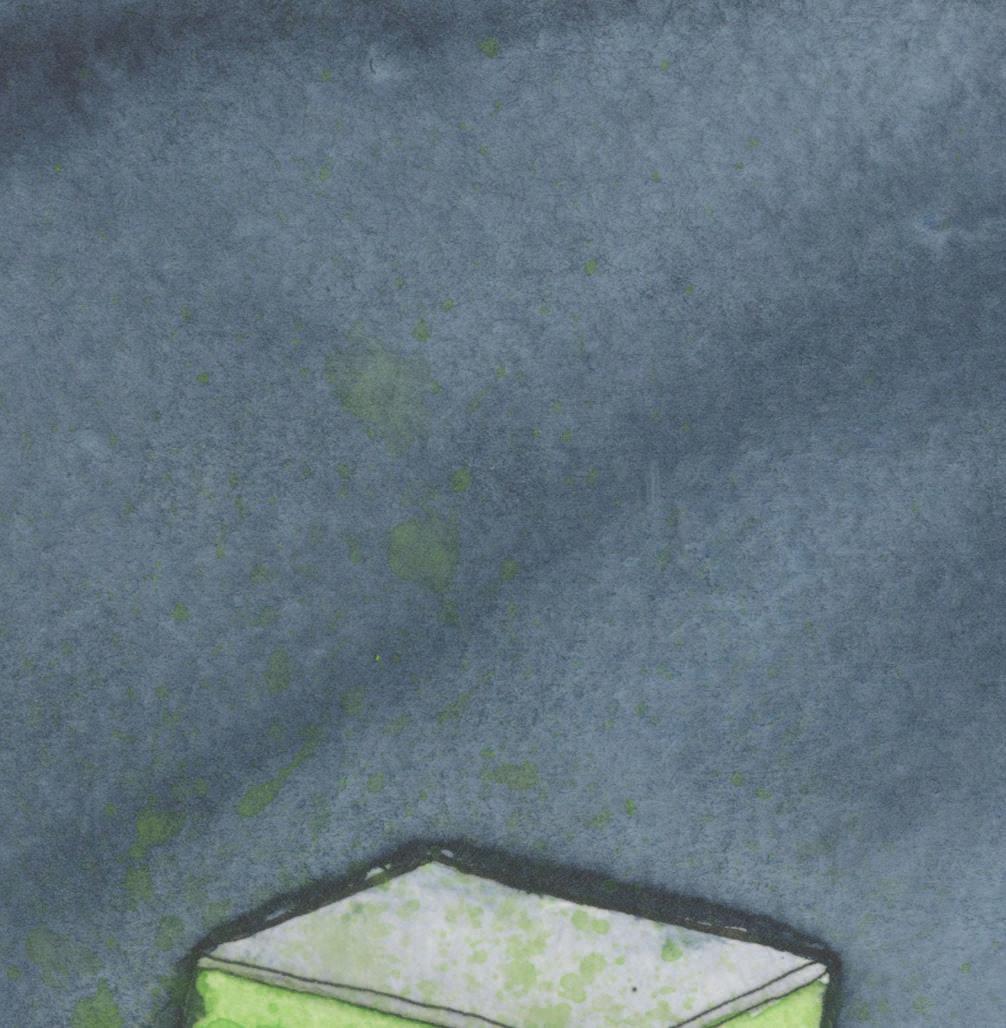

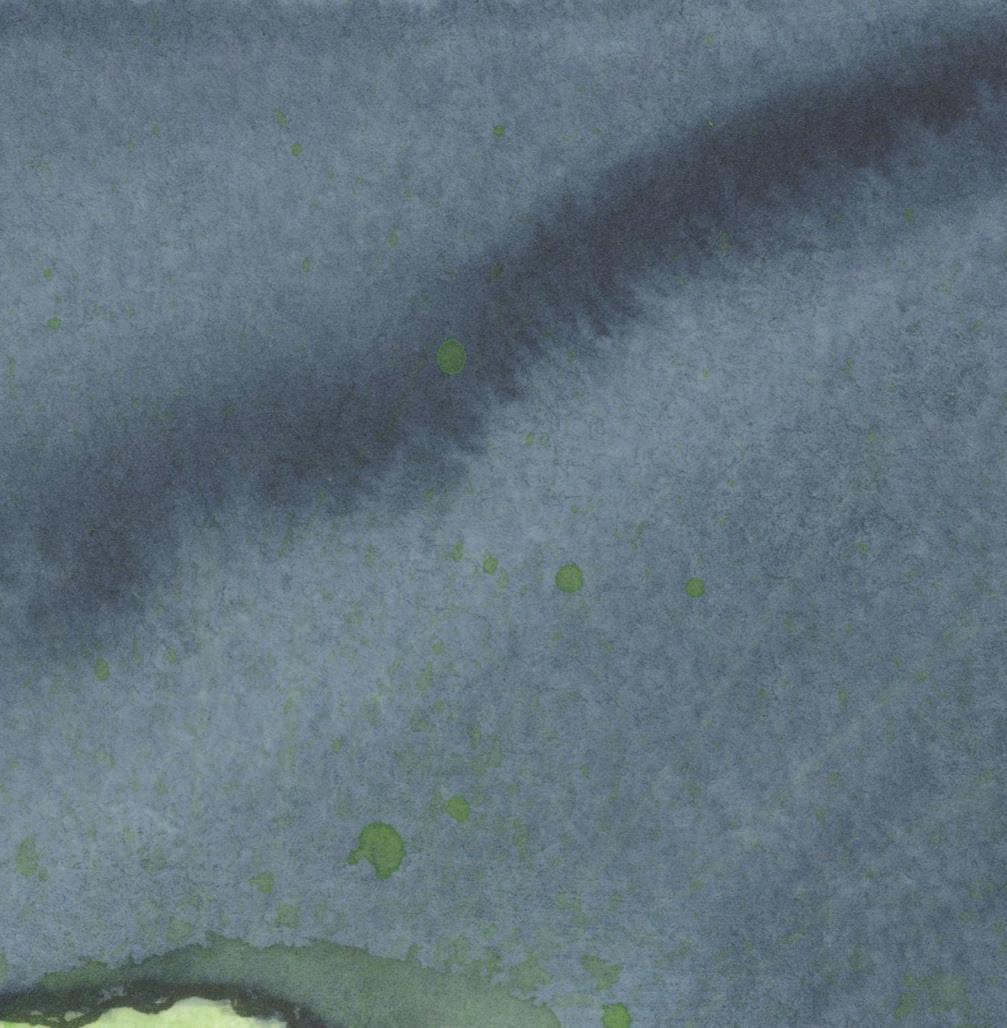

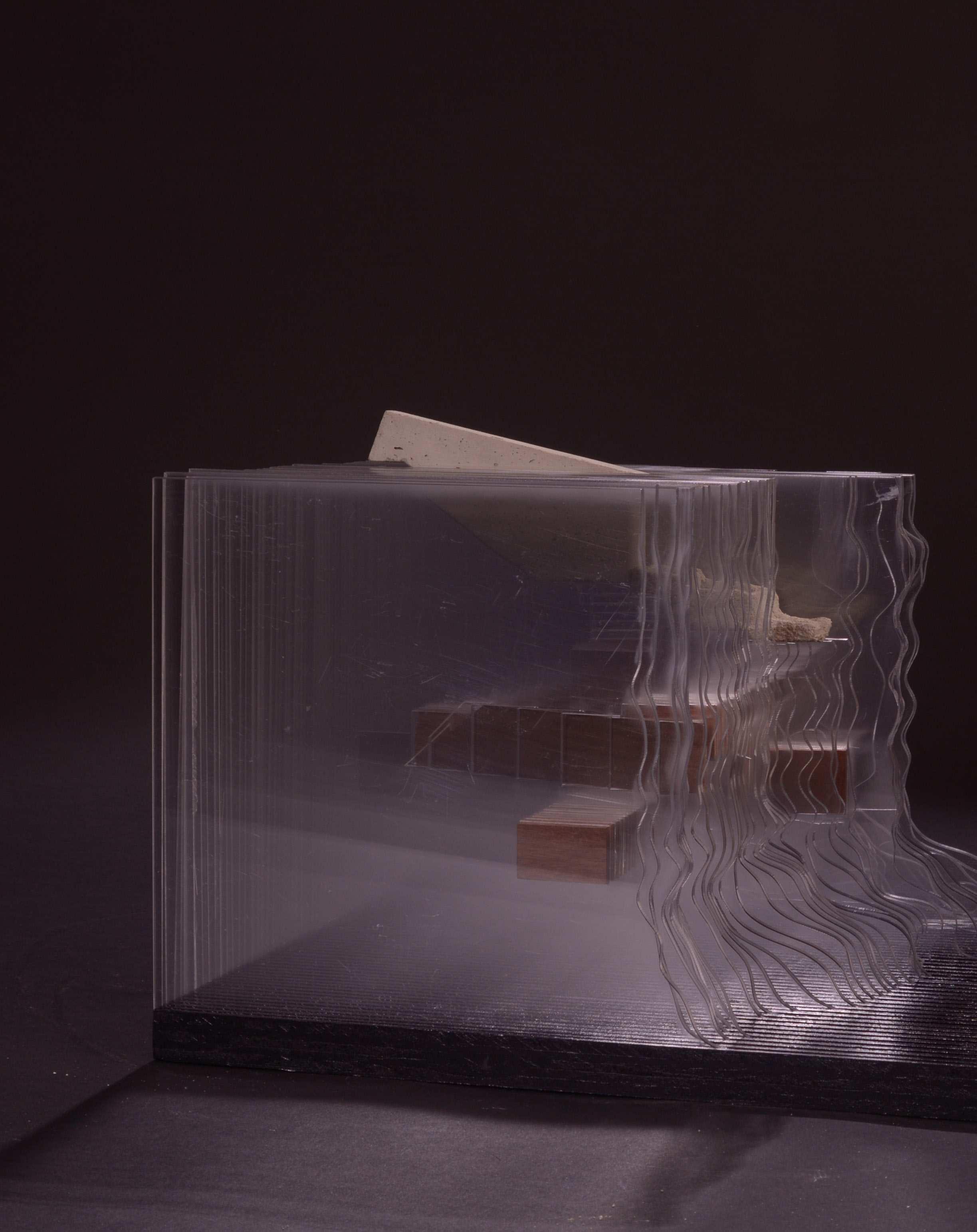

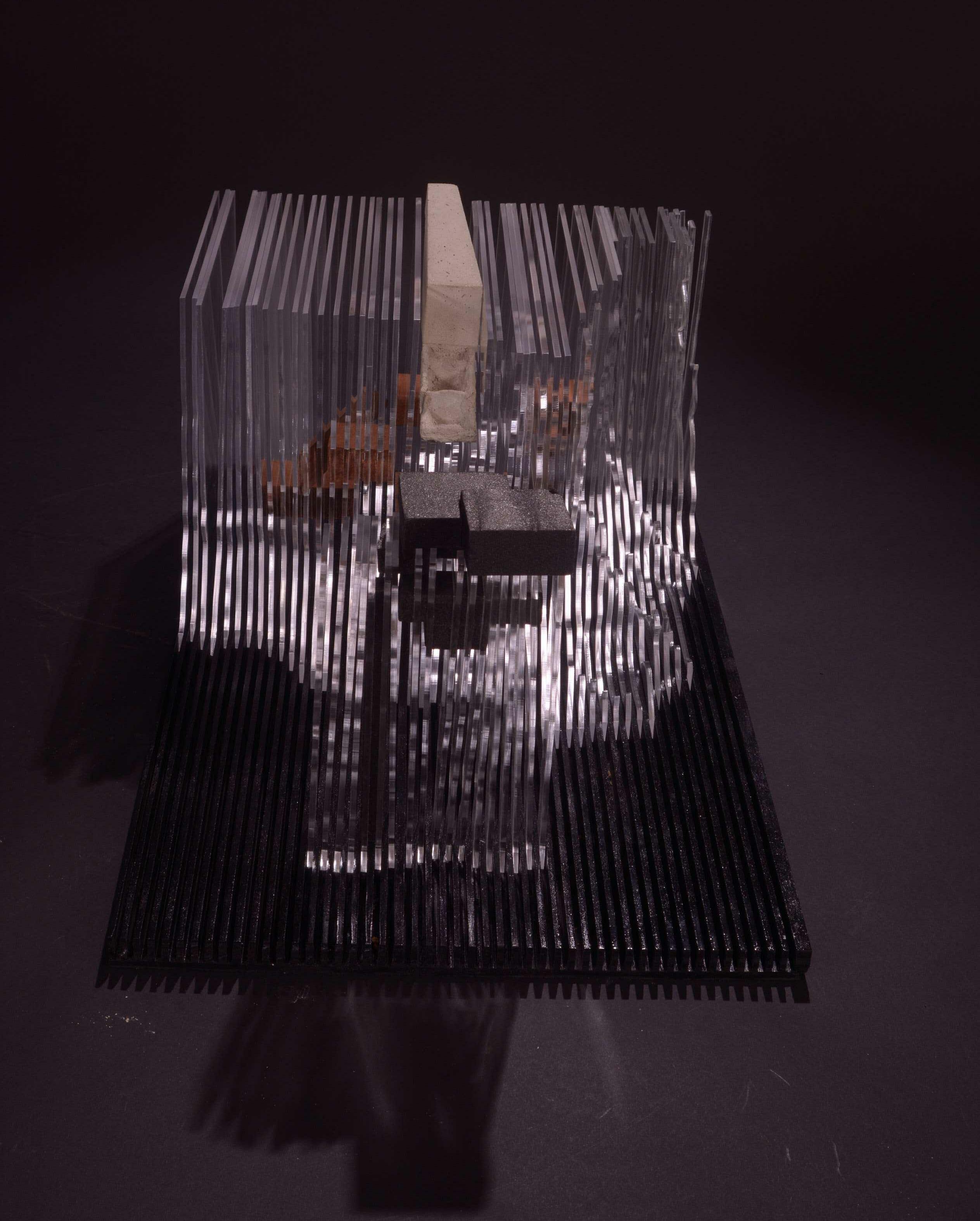

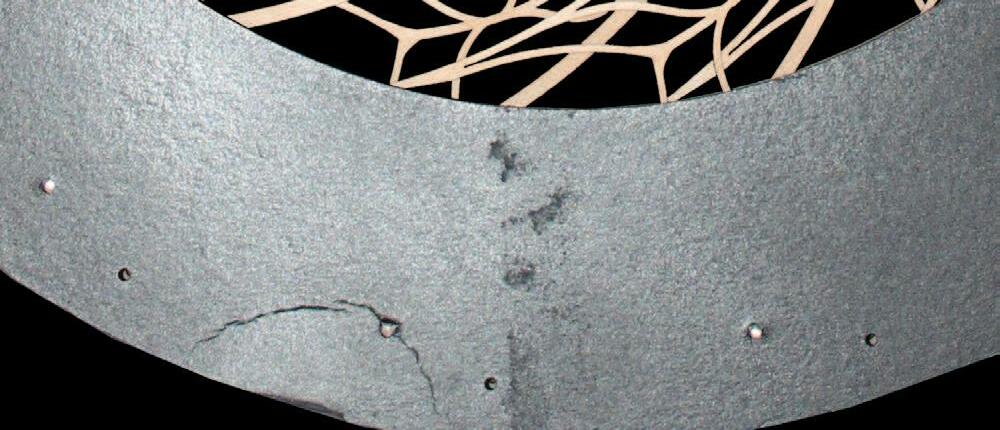

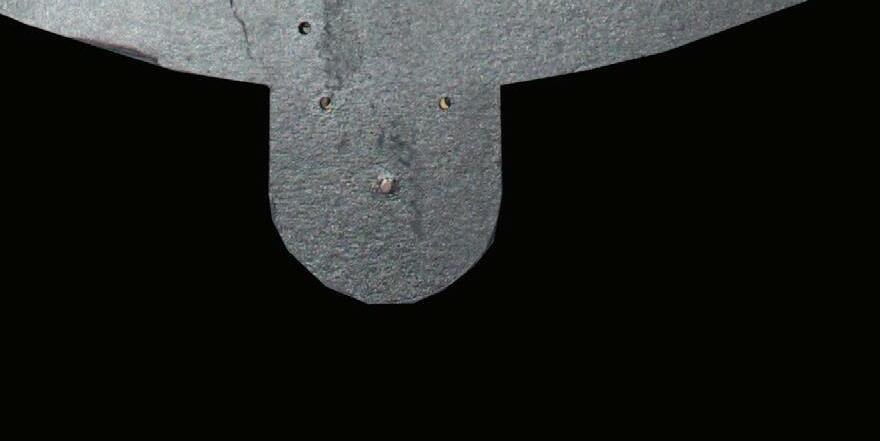

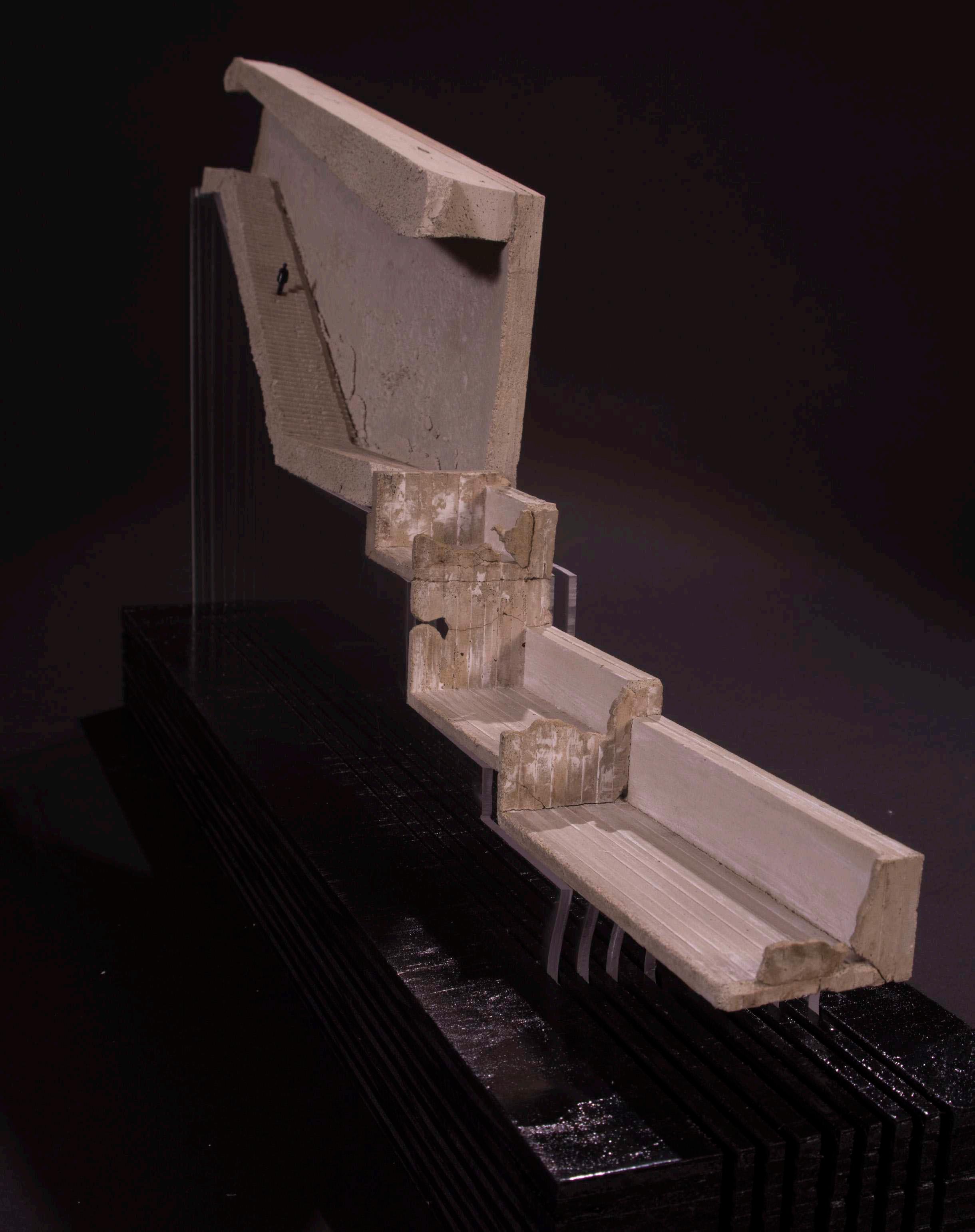

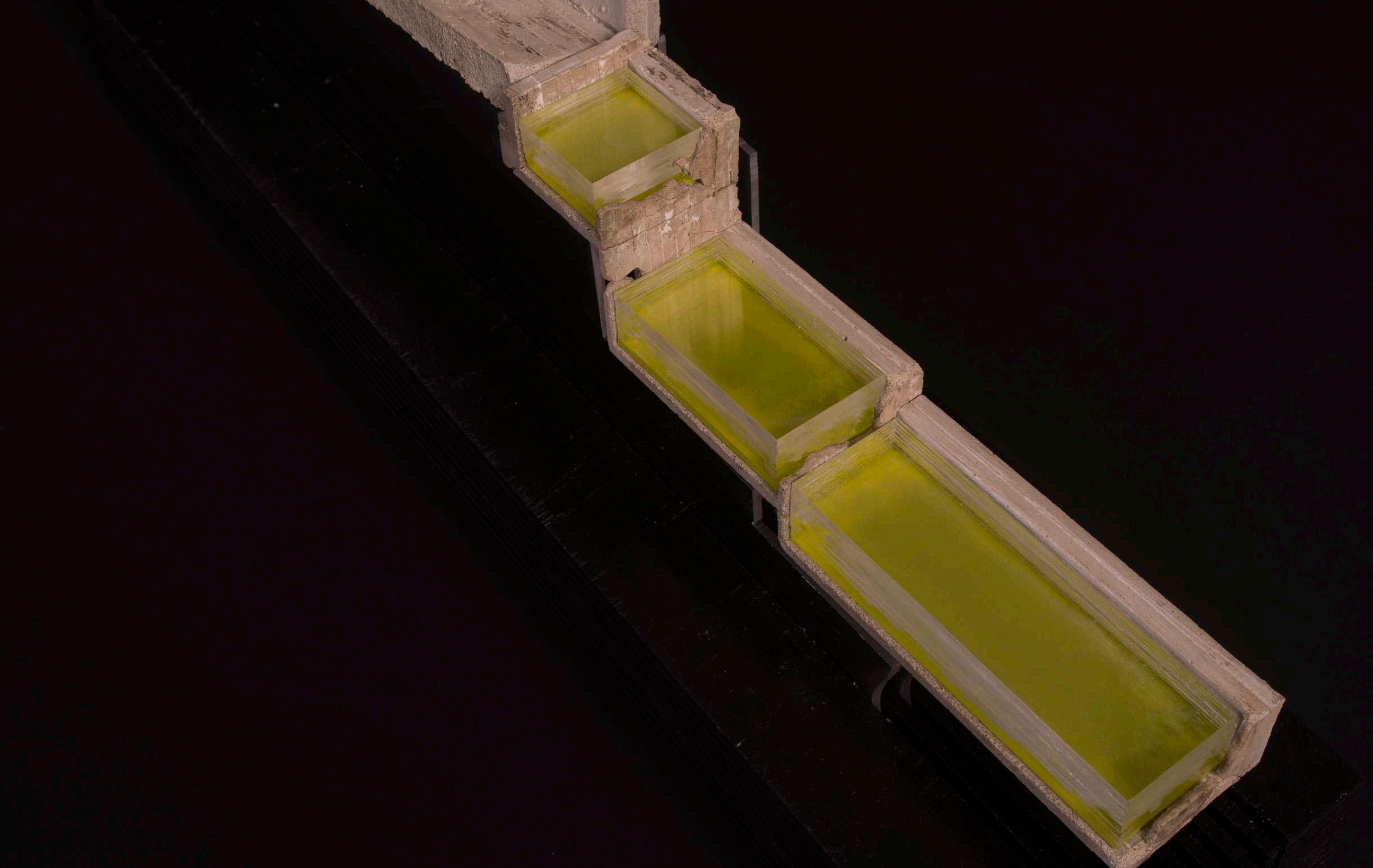

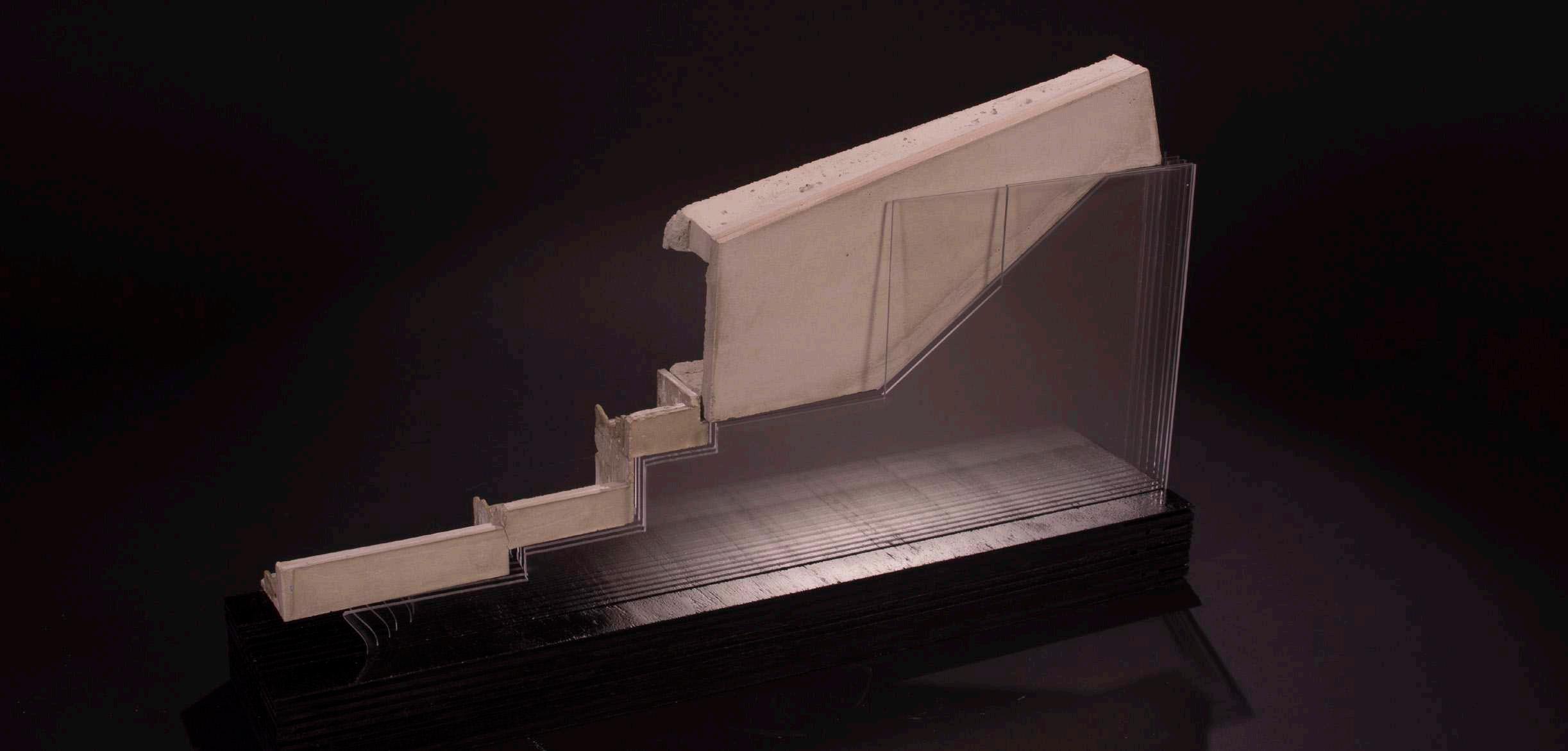

ConceptModel. A smooth, symmetrical, impressive exterior hides the chaos beneath. The relative normality of the massive entrance disguises the uncertainty of the peculiar underground.

60

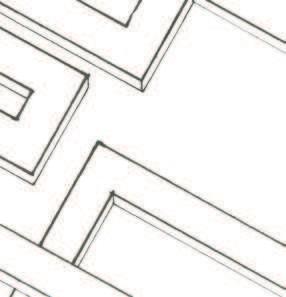

Spatial Implications

What does the architecture of Evil look like? What are the spatial qualities that encapsulate Evil?

The iconic villain lair is a unique typology rarely, if ever, found in real life. Thus it is only through media such as ilm that we get a picture of what these spaces can look like.With Bond villains,we have historically come to expect a modern1 , borderline-futuristic lair set in some exotic locale, oftentimes hidden away where few can ind them. While each lair is unique to the villain, it is possible to create a formula that allows for customization that consistently produces a successful lair.

1. Ian Fleming, the creator of James Bond, is rumored to have named infamous villain Aulric Goldinger after modernist architect Erno Goldinger as a manifestation of his distaste for the widely unpopular modern style. As a result, Bond villains throughout the years often reside in modern homes, thus forever linking the style with villainy.

Fisher, James. “Architecture: Goldinger. He’s the man with the modern touch.” The Independent. August 27, 1998. Accessed January 12, 2017. http://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/architecture-goldinger-hes-theman-with-the-modern-touch-1174530.html.

62

What are there qualities of a space that characterize it as “evil” or “villainous?”

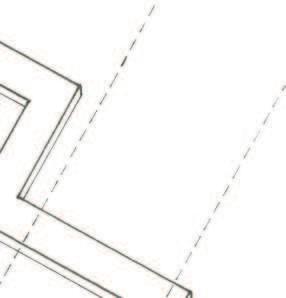

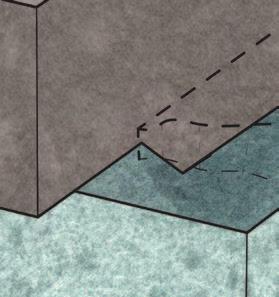

Sequence of experiences as one moves through the villain’s lair

The architecture of Evil looks normal on the outside, concealing the Evil within. Similar to Nazi architecture, the entrance is designed to impress, intimidate, and belittle those who cross the threshold. Shortly after entering, the intruder can see the ultimate goal, the place where they will encounter the villain, but cannot see a direct path.The initial impact of the building form and massive entryway serve to immediately reduce the tresspasser, working in tandem with the visual access to, yet physical separation from the villain to reinforce the desired power dynamic as well as initiate the psychological warfare further manifested in the obstacles.

Thus begins the journey through the fear labyrinth—a daunting series of challenges, obstacles, and tests that require physical, mental, and emotional fortitude. Like any good labyrinth, there is only one correct way to reach the end. Any apparent options simply act as detours,providing additional obstacles while forcing the intruder back to the intended path.The journey is designed to disorient,confuse,and weaken,pairing opposing spatial qualities in sequence while creating unexpected experiences throughout.

63

Those who successfully navigate the labyrinth then face a inal obstacle with the goal in their sights. If the intruder can traverse this challenge, the villain awaits in a grand and imposing fashion.

Control shifts more fully to the villain after the initial encounter—the intruder no longer has any say in how far they proceed into the villain’s residence—access is granted at the will of the villain. Access to the residence takes place in four stages: the ofice, the semi-public living space, the private living space, and the inner sanctum.

What does the architecture of Evil look like from the perspective of the villain?

Any worthy lair makes the villain feel like a god in their own right. Extreme luxury with outlandish features that scream wealth and power. Sleek modernity that indicates the villain is sophisticated and ahead of their time. Absence of personal affects, clutter, and otherwise typical staples of a standard residence adds to the mystery and otherness of the inhabitant. Access for others is restricted to certain areas, yet the villain can move throughout the entirety of the space with ease, uninhibited by the boundaries that apply to all others.The residence allows the villain to constantly take the higher ground, perpetually looking down upon intruders. No lair is complete without a hidden entrance to the inner sanctum—the most sacred space in the residence. The inner sanctum is where the true villainy occurs, the legitimate workspace where the master plots transform from ideas to reality. A secondary entrance provides direct access to the inner sanctum while acting as an escape for quick getaways.

64

OFFICE PUBLIC RESIDENCE ROOFTOP POOL PRIVATE RESIDENCE HELIPAD MOVING FLOOR INNER SANCTUM ESCAPE HATCH 65

Design Intent

How the general principles became

Nestled into the cliffside, the entrance to the lair subtly juts out of the landscape, reducing the visual impact from the surface. As one approaches, only the large, ornately carved wooden door can be seen. Once inside, intruders encounter a massive,symmetrical space with rich materials and stunning lighting that create an intimidating and aweinspiring atmosphere. Upon descending into the entrance space, intruders can look out the large circular window to glimpse the residence beyond. The rose windowesque opening functions as an iris aperture, opening to those who know the proper procedure. For the villain, the panels spiral open as platforms raise out of the acid pools to create a direct path to the residence, located on an offshore island. Those unable to exit through the window must then turn to the large crevice in the wall— the entrance to the labyrinth. To instill fear and doubt into those who dare enter, the sequence of experiences is designed to catch trespassers off guard, contrasting

66

an actual design.

opposing spatial qualities to disorient. Anticipation created by this juxtaposition introduces the opportunity to induce psychological stress when the intruder is presented an extreme without its opposite. Similarly, should the intruder encounter a seemingly familiar and relatively safe condition the established pattern would indicate that an unfamiliar, dangerous experience follows quickly after. The subterranean maze forces intruders to complete challenges, select between dificult options, and face fears. The obstacles focus on different types of strength—of character, will, mind, and body. Circular rooms present intruders with various doors to choose from, each presenting new challenges,some leading back to previous spaces, with only one allowing forward progress.

The labyrinth is not intended to kill, but rather torment.The villain experiences great pleasure in observing intruders navigate the obstacles, relishing the pain and misfortune of those who attempt to gain access to the island. Any who manage to escape the underground trials face a 150 foot glass bridge, narrow, devoid of railings, and nearly invisible. At the end of the bridge is a glass staircase leading up to the balcony where the villain waits, elevated above the enemy, cloak billowing in the wind. For those who survive to reach the island, further entry is granted by the villain, who takes interest in anyone who can reach the point of encounter. Separated from the balcony by a wall of loor-to-ceiling glass, the ofice acts as the irst level of permitted access. Footsteps echo on the polished marble loor as the pair proceeds toward the only item in the room a rich leather chair behind a solid mahogany desk. Hidden light sources illuminate the room, casting strange shadows on the

67

textured black stone lining the walls. Something about the space seems unnatural, unnerving. The utter lack of stuff, whether on the walls or atop the desk, contribute to the otherness of the villain.

Moving to the rear of the room, the wall slides to the right, revealing a tall, empty room beyond. As the two leave the ofice behind, the wall returns to its original position as the loor of the secondary room begins to rise. Bright light loods in as the loor approaches the residence above. What can only be described as a living room inhabits the tiered space. Richly furnished, crafted out of the inest materials, the ultra-modern residence oozes wealth and power. Slightly sunken into the rock, the initial double height space receives light from the openings above.

Crossing the arched bridge,the intruder looks down to see a large shark swimming lazily in the pool below.Ascending the twelve stairs to the ground level, the pair pauses to admire the view of the cliff face from the sleek, futuristic sofas spanning the space. Suspended in the center of the lofty space, half a level above the ground loor, a lounge with a fully-stocked bar awaits those privileged enough to receive access.

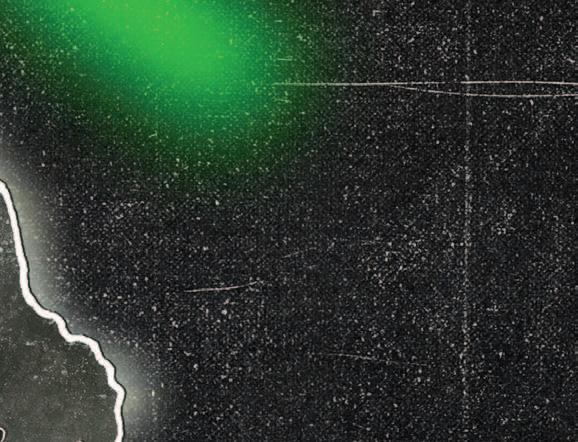

Located halfway between the ground and lounge levels, offsetfromthemainlivingarea,thevillain’sprivateresidence looks out over the ocean to the west, affording glorious views of the sunset on the horizon. From this space, the villain can lead the intruder either up to the roof or down into the subterranean level. The roof provides access to the helipad and ininity pool. Should one be so lucky as to take a swim at night, the water relects the green light of the lames surrounding the edges. The subterranean level can be accessed by another moving loor, leading to the

68

most highly protected space in the lair—the inner sanctum, wherethetruevillainyoccurs.Themassivecavernisdivided into platforms of varying heights connected by stairs and catwalks. On one platform, screens too numerous to count display live footage of various potential targets,computers running scenarios and probabilities for nefarious schemes. Weapons in various stages of development ill another. Vehicles ranging from sleek sports cars to stealth jets to transforming utility transports each occupy their own platform. Illuminated on glass pedestals, trophies from successful conquests line the walls. On the far side of the sanctum,a hidden door opens to reveal another seemingly empty space.This moving loor descends to the base of the island, where the villain stores a wide array of ocean craft submarine, yacht, jet ski, and speedboat. This access point serves the dual purpose of water entrance and secondary escape route.

Only the villain can activate the moving loors any who access the sliding walls without permission will ind themselves trapped in a shrinking space that can only be stopped by the villain. Any part of the residence can be completely locked down while the bulletproof glass is generally suficient to protect the villain from standard attacks, armored panels can slide into place, insulating the space from harm. While this protects the villain, it can also seal in any intruder that loses favor. Every aspect of the residence is designed for the comfort and protection of the villain, with the dual purpose of reinforcing the inhabitant’s superiority through subtle and overt indicators of wealth and power throughout. This indicators have the dichotomous effect of increasing the villain’s sense of self while decreasing that of the intruder.

69

The Architecture of Evil controls, restricts, intimidates, minimizes, and otherwise inhibits, reinforcing the insignificance of others in comparison to the power and superiority of the villain by exploiting common perceptions of and feelings towards certain spatial qualities.

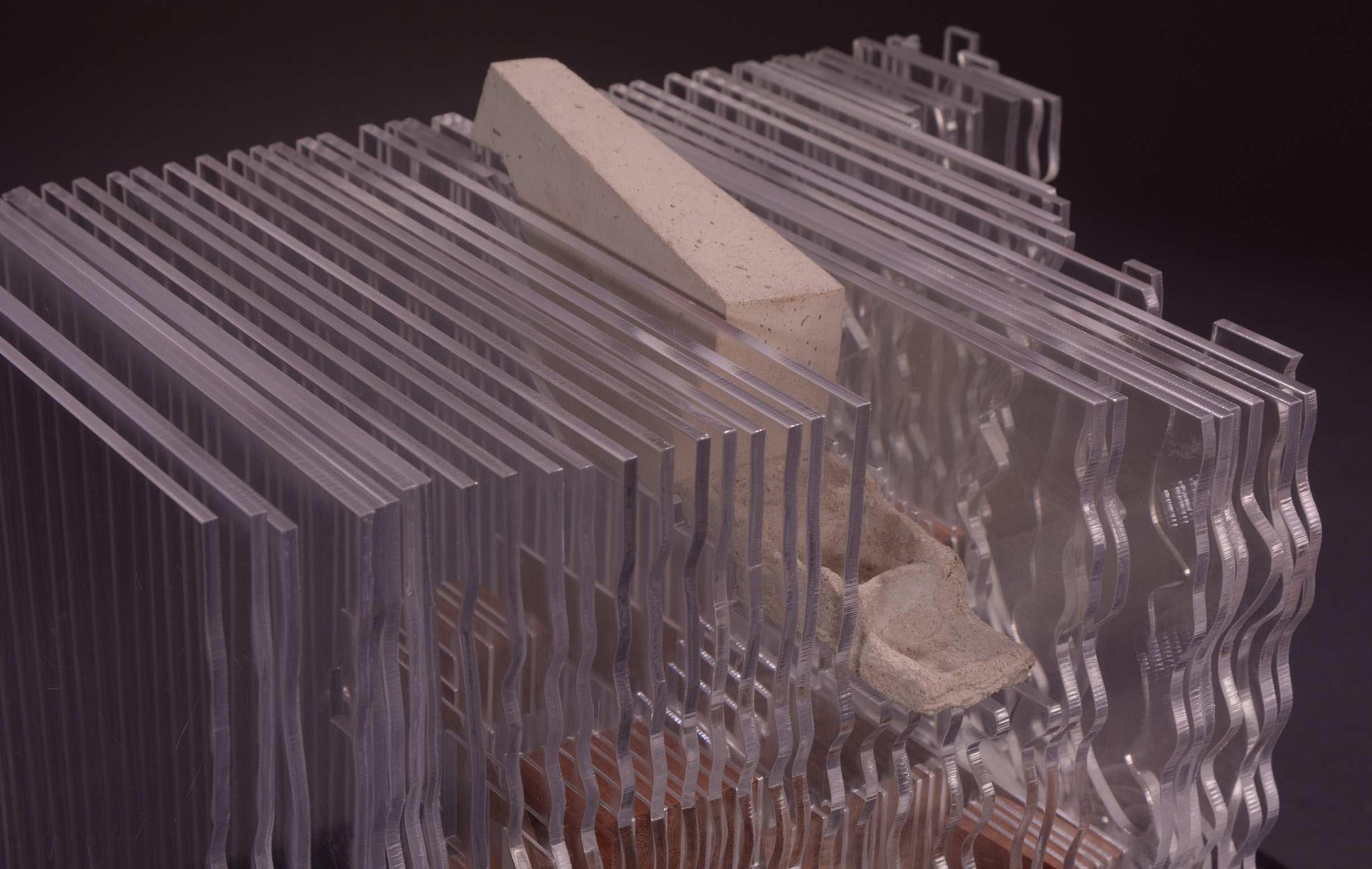

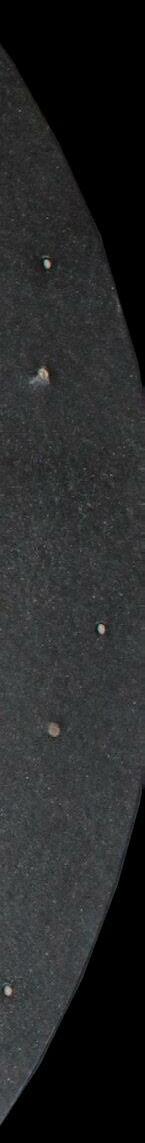

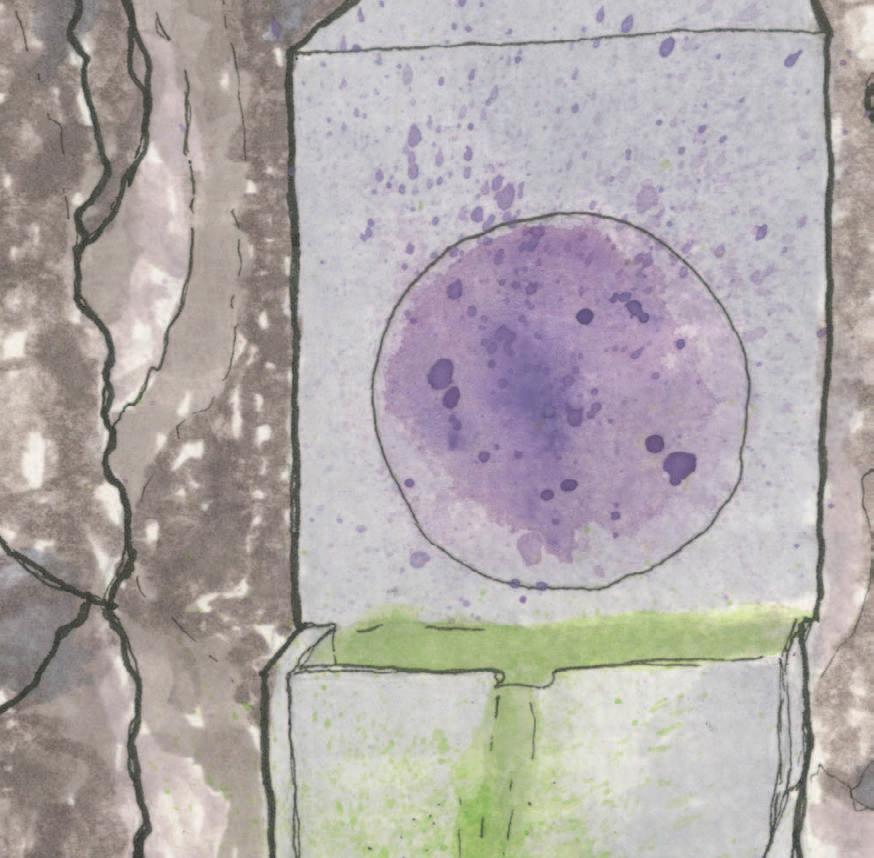

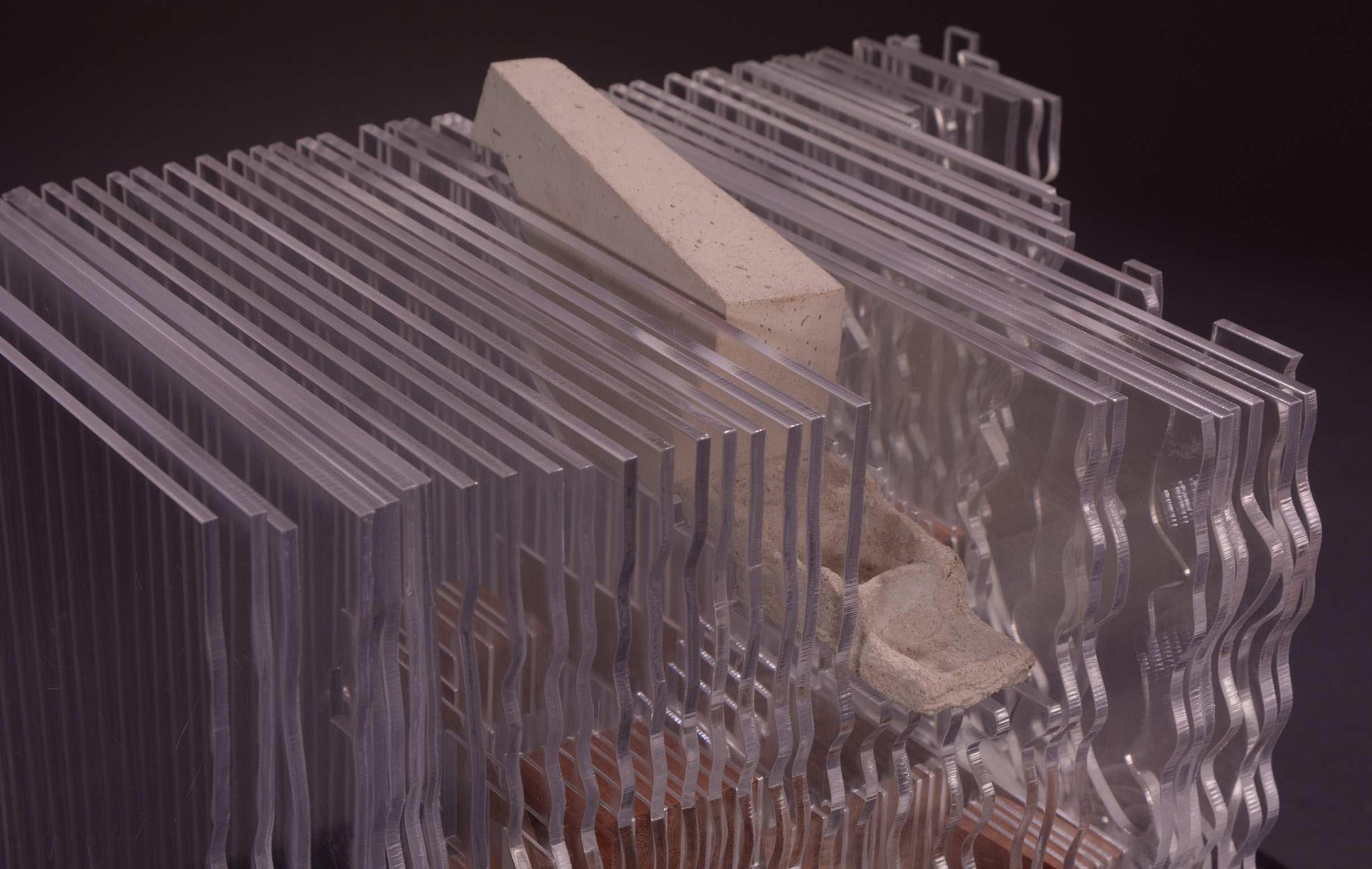

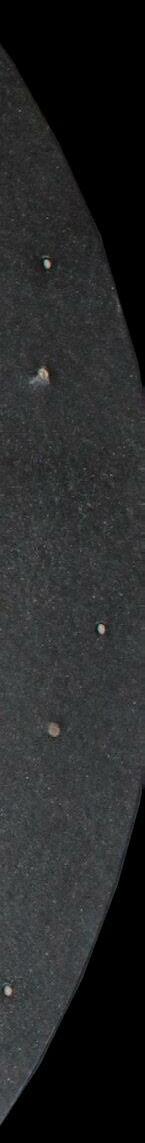

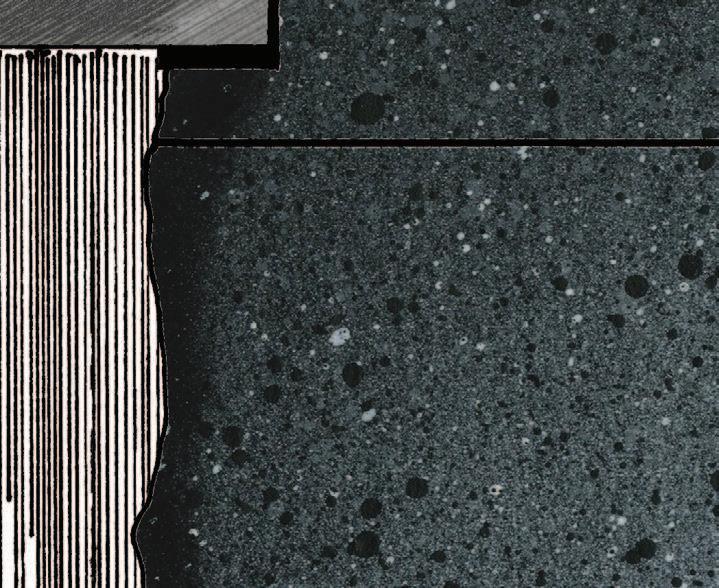

Site Model. Layers of acrylic form the cliffside and offshore island, suspending the lair 200 feet above the ocean. Poured concrete represents the true materiality of the entrance and pool system, while the wood pieces representthevoidscarvedintotheunderground.Across the gap, the black foam describes the massing of the villain’s residence, both hidden and exposed. Physical perspective hides and reveals various aspects of the underground systems as the layers of acrylic obscure the massing.

73

Details. The smooth concrete of the entrance protrudes slightly from the chasm carved into the cliff face. Thecleanlinesoftheresidence cantilever over the edge of the island, granting spectacular views and giving off the appearance of loating.

77

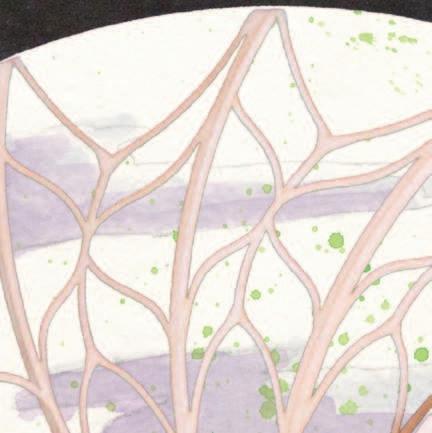

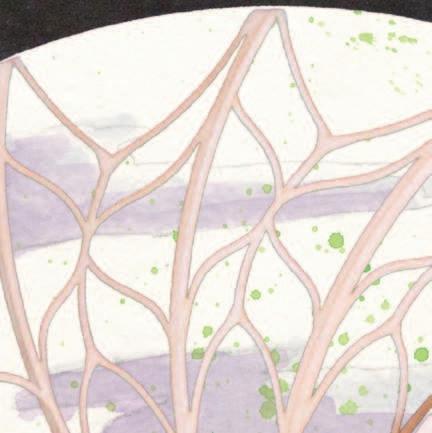

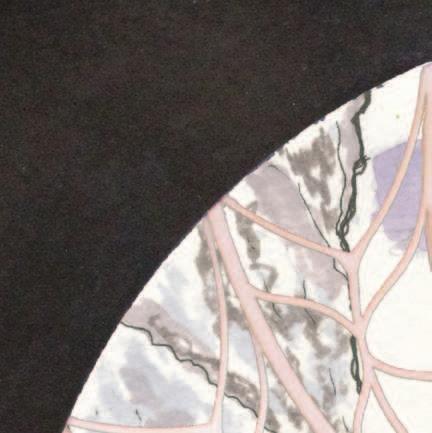

Model of the iris aperture in the closed position, as it would appear to intruders, displaying the view of the island beyond

78

Model of the iris aperture as it opens for those who know the correct sequence, granting access to the island beyond

79

View of the cliff face from the roof of the residence

80

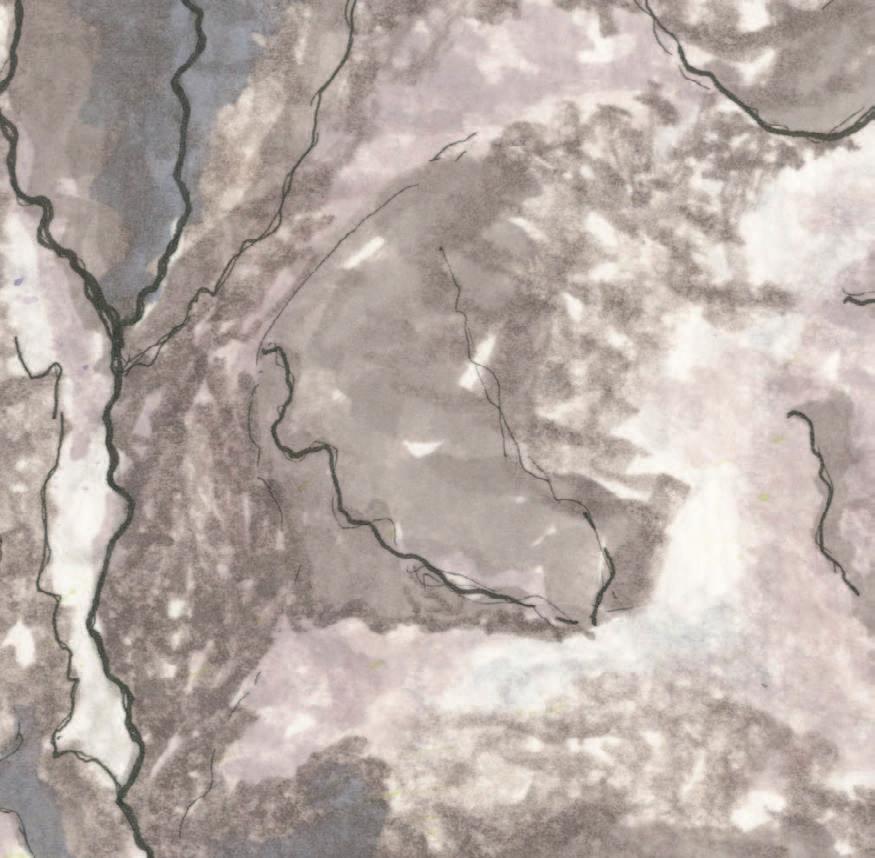

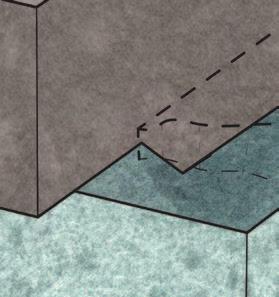

Section Model. Bisecting the entrance and tiered pools, the section model demonstrates the spatial and textural qualities of the space that provides the irst impression of the villain for the intruder.

83

By Susie Caldwell

By Susie Caldwell

igure 1 // Parade ground. Templehof feld rally. Stage designed by Albert Speer.

igure 1 // Parade ground. Templehof feld rally. Stage designed by Albert Speer.

Roger Moorhouse, “Germania: Hitler’s Dream Capital,” History Today, March 2013.

Roger Moorhouse, “Germania: Hitler’s Dream Capital,” History Today, March 2013.

Images courtesy of Bahnhof

Images courtesy of Bahnhof