NATIONAL COASTAL SAFETY REPORT 2025

INTRODUCTION

Australia’s coastline is a national treasure – an iconic part of our identity and an everyday place to recreate, relax, and connect with our community and environment. With 87% of Australians now living within 50km of the coast, it is perhaps not surprising that more than 16 million Australian residents (aged 16+ years) made over 630 million individual visitations to the coast last year, 88% of which were to our incredible beaches. Of the people who visit our coast, swimming remains the most popular coastal activity (57%), followed by boating (16%), then watercraft (13%; i.e. kayaks, canoes and other paddlecraft).

While a source of joy for most, the dynamic and uncontrolled nature of coastal environments means there are also many inherent risks and dangers. The National Coastal Safety Report 2025 reveals a sobering reality: 239 lives were lost in coastal environments. This number includes 154 drowning deaths, the highest ever recorded, representing a 3% increase from 2023/24 numbers and 21% above the 10-year average for coastal drowning. All coastal drowning deaths occurred outside of the red and yellow flags or patrol times. Surf Life Saving is responding, but the challenge is immense and growing – without further resourcing to support the demands of unpatrolled and remote locations.

Behind these numbers are families, friends, and communities forever changed. Comprehensive analysis highlighted that 87% of drowning decedents were male

and that older Australians remained disproportionately at risk, with those aged 55 years and over accounting for 55% of drowning deaths –emphasising the importance of inclusive community programs such as Silver Salties.

Beaches continue to be the leading drowning location (53%), with three in four incidents occurring greater than one kilometre from Surf Life Saving services, all outside of patrol times or at unpatrolled areas. Rip currents remain the leading coastal hazard, contributing to more than one in three beach drowning deaths, while swimming and wading remain the most common activities prior to drowning.

These numbers, while tragic, would have been inevitably much higher

without the enormous efforts of Surf Life Saving (SLS). Our incredible workforce, which includes more than 200,000 members from 316 SLS clubs, has never been more critical— or more impactful. In 2024/25, our volunteer and professional lifeguard services delivered 8,207 rescues, 2.19+ million preventative actions, and 65,942 first aid treatments, providing an estimated $9 billion in value to the community. These achievements are a testament to the dedication, skill and courage of our surf lifesavers and lifeguards, who stand as the first line of defence at many of our beaches. Without the interventions of our surf lifesavers and lifeguards, there would have been at least an additional 1,500 coastal drowning deaths last year alone. That’s the scale of impact of the services we provide.

This report also highlights the importance of innovation and education in reducing risk. Initiatives such as Public Rescue Equipment, Lifesaving CPR training, the Beach Blackspot Drowning Reduction Program and the Beach Passport, as well as the integration of emerging technologies, are transforming our approach to prevention and response. Equally, campaigns such as Stop, Look, Stay Alive and programs targeting high-risk groups, including rural or multicultural communities and older Australians, are essential to building everyday water safety skills and awareness.

SLSA’s vision of zero preventable deaths in Australian waters is aspirational but is intended to drive impactful collaboration across the water safety sector. Meaningful reductions are achievable – but only if we work together. Government, industry, communities and individuals all have a role to play. This report is more than a collection of statistics - it is a call to action in memoriam of the 239 people who did not return home to their loved ones. Any life lost is one too many, and every intervention that prevents tragedy is invaluable.

This report is a wake-up call. It shows us where the risk is shifting, and where our collective effort must go next. We need every water safety organisation, every level of government, and the support of the community to push harder. Together with the support of the Federal Government, we need to step up our efforts in empowering communities to stay safe, future-proof lifesaving infrastructure and resource surf lifesavers to go further. We know what we need to do, backed by research and evidence. We have to act because the scale of the challenge demands it.

As you read this report, I encourage you to reflect on the collective responsibility we share in making our coastline safer. We have a plan, we know where the risks are. We know that with the right support, we can turn the tide on coastal drowning. Together, with additional support and through education, innovation and collaboration, we can ensure that every trip to the coast ends with a safe return home.

Adam Weir Chief Executive Officer Surf Life Saving Australia

UNDERSTANDING DROWNING

WHAT IS DROWNING?

The globally accepted definition of drowning is: ‘The process of experiencing respiratory impairment from submersion or immersion in liquid’. Importantly, there are three outcomes for a person who experiences drowning:

• death,

• survival with morbidity, or

• survival with no morbidity.

Please note: terms such as ‘near drowning,’ ‘secondary drowning,’ and ‘wet/dry drowning’ are incorrect and are no longer used.

COASTAL DROWNING

Coastal drowning refers collectively to fatal or non-fatal drowning incidents that occur in coastal (up to 3 nautical miles) and ocean (3-12 nautical miles) environments, including beaches, estuaries, river mouths, oceans/ harbours, rocks, and coastal rock pools, up to and including 12 nautical miles from shore. Specific definitions can be found in the glossary.

FATAL AND NON-FATAL DROWNING

This report includes information on fatal drowning only, that is people who die from submersion or immersion in water. However, the burden of drowning is not limited to these deaths alone.

Each year, hundreds of non-fatal drowning events occur which have a range of outcomes. Sometimes the person who drowns and survives might only need to visit a clinic or

hospital for a clinical assessment. In other instances, non-fatal drowning events result in permanent, life-altering neurological disability that severely impacts the person who drowns, their family, friends and community.

Preliminary analyses suggest that for every fatal beach drowning, another nonfatal beach drowning incident occurs*, while at other water bodies that ratio grows to three non-fatal incidents**. The exact number of non-fatal drowning incidents is difficult to report with precision, which is why improving data systems for non-fatal drowning is a priority identified in the Australian Water Safety Strategy 2030.

HOW DO WE MEASURE DROWNING?

The coastal mortality section in this report (Section 3) includes counts, proportions, and rates. When analysing drowning data, counts, proportions and rates are presented to offer different perspectives of the data. Each of these measures are useful but serve a distinct purpose.

Counts represent the number of drowning events that occur within a given time frame, geographic location, and/ or subgroup. These are useful for understanding the scope of the problem, communication about the burden, and for determining the required capacity and scale of services or programs. Under some circumstances, when counts are too small to be interpreted meaningfully, multiple years of data are combined.

Proportions refer to the part of a whole, expressed as a fraction or percentage, that represents a specific group of drowning incidents relative to the total number of drowning events. Percentages are often easier to understand and communicate in context, and they allow for simple comparisons between different groups that vary in the number of cases.

Drowning rates (presented here as crude fatal drowning rates per 100,000 residents) take into consideration the size of the population that are at risk of drowning. By using rates, we can compare the drowning burden across populations that vary in size, allowing us to identify groups that are disproportionately affected by drowning and should therefore be considered priority groups for prevention efforts.

• Population-based rates: crude population-based rates estimate the risk at the population level, grouping exposed and unexposed populations together (i.e. both people who do, and do not, visit the coast). This can underestimate drowning risk by including people who are not actually at risk of drowning.

• Age and Sex-specific rates: these are population rates that specifically use only the relevant population groups, i.e. calculating male rates using the number of male drowning deaths as the numerator and the population of males as the denominator. It is more specific than using the whole population but remains an underestimate for the same reason.

• Exposure-based rates: exposure-based drowning rates only consider people actually at risk of drowning (i.e. the proportion of the population who visit the coast and are exposed to coastal drowning risks). This allows for more accurate estimates of drowning risk, which can be further refined by extending calculations beyond the exposed populations (i.e. coastal visitors), to include frequency (i.e. how many times they visit the coast), and duration (i.e. the time spent during each visit). This can be reported as time-exposed (i.e. one incident per number of hours spent each year actively participating) or person-exposed (i.e. one drowning death per 100,000 rock fishers).

For more detailed information please refer to the methodology described in the reference pages.

* Surf Life Saving Australia (2018). National Coastal Safety Report 2018. SLSA: Sydney.

** Peden AE, Mahony AJ, Barnsley PD, Scarr JP (2018). Understanding the full burden of drowning: a retrospective, cross-sectional analysis of fatal and non-fatal drowning in Australia. BMJ Open 2018;8:e024868. doi:10.1136/ bmjopen-2018-024868

THE DROWNING PREVENTION CHAIN

The Drowning Prevention Chain visualises a recognised framework to reduce drowning (International Life Saving Federation 2015). It identifies four causal factors that can lead to death or injury by drowning, visualised in the outer circle of this chain and corresponding mitigation and control strategies that can prevent or reduce drowning.

Figure 01 THE DROWNING PREVENTION CHAIN (International Life Saving Federation 2015)

SLSA’S DROWNING REDUCTION AND PREVENTION FRAMEWORK

SLSA's Drowning Reduction and Prevention Framework (Figure 02) is a holistic approach to reduce drowning and improve coastal risk management. By employing a data-driven approach to reduce coastal and drowning risks, this Framework guides targeted interventions and informs strategic direction to reduce coastal drowning in Australia.

In partnership with stakeholders, SLSA integrates multiple data sources with an iterative, evidenced based approach to analyse and address national coastal safety issues, aiding with establishing national priorities and blackspot locations.

This Drowning Reduction and Prevention Framework outlines an integrative process that supports the delivery of education, prevention and response strategies to safeguard the community. Continuous monitoring, evaluation and engagement ensures delivery remains responsive to emerging risks and community needs. This process facilitates feedback and guides practical interventions such as lifesaving and response services, communication campaigns, and blackspot reduction programs to turn the tide on coastal drowning and improve safety outcomes.

NOITACINUMMOC & C ONSULTATION

Drowning data (fatal and non-fatal)

DATA INPUTS

Operational data Population/ visitation data

RISK ASSESSMENT

Behaviour data

Risk identification | Incident tracking | Coastal risk assessments

Community risk perception and behaviours | High risk locations/populations

RISK ANALYSIS

Epidemiology | Critical incident analysis | Spatial analysis | Case studies

EVALUATION & REPORTING

Incident and mortality report | National safety agenda | Coastal safety briefs

Blackspot identification | National coastal safety risk prioritisation

Surf lifesaving and support services INTERVENTION

Public education and training

Communication campaigns Emergency response Blackspot reduction program

Early warning systems

ONGOING MON I TO R I N G & NOITAULAVE

NATIONAL PRIORITY AREAS

The issues identified through the Drowning Reduction and Prevention Framework form SLSA’s Priority Areas, highlighting high-risk groups, locations and causal factors for coastal drowning. The National Priority Areas inform drowning prevention education, mitigation strategies and communication campaigns.

This Drowning Reduction and Prevention Strategy provides evidence to allocate assets, resources and lifesaving services to areas of need and to develop appropriate public education programs and mitigation strategies to address the coastal safety issues within known blackspots or groups at risk of drowning.

NATIONAL PRIORITY AREAS

Figure 02

SLSA’S DROWNING REDUCTION AND PREVENTION FRAMEWORK

Visualising the cyclical risk management process employed to reduce and prevent drowning and injury along the Australian coast.

SECTION 1 COMMUNITY

16.0

13.4

4.0

AUSTRALIAN ADULTS* VISITED THE COAST IN 2024/25

COASTAL ACTIVITY PARTICIPANTS IN 2024/25

* for the purposes of this section adults include Australian residents aged 16+ years.

AUSTRALIAN ADULTS* HAVE EVER BEEN UNINTENTIONALLY CAUGHT IN A RIP

AUSTRALIAN POPULATION

VISITATION & PARTICIPATION

Figure 03

AUSTRALIAN POPULATION DENSITY PER LOCAL GOVERNMENT AREA (LGA)

This heat map shows the estimated Australian population density per LGA at June 2025. The majority of LGAs with a population density greater than 100 persons per square kilometre are located on Australia’s extensive coastline. The National Coastal Safety Survey 2025 (NCSS2025) collected data on coastal visitation, frequency and activity participation for each state which are also presented here.

1.7M Coastal visitors 3.4 Visits per month 2.1 Hours per visit 1.4M Coastal activity participants 1.2M Summer activity participants

<0.1 persons per km2

0.1 - 1 persons per km2

1 - 10 persons per km2

10 - 100 persons per km2

>100 persons per km2

NT

0.15M Coastal visitors

3.9 Visits per month

1.9 Hours per visit

0.1M Coastal activity participants

0.1M Summer activity participants

QLD

3.4M Coastal visitors

3.7 Visits per month

2.5 Hours per visit

2.8M Coastal activity participants

2.3M Summer activity participants

SA

1.2M Coastal visitors

3.0 Visits per month

2.4 Hours per visit

0.9M Coastal activity participants

0.8M Summer activity participants

NSW

5.4M Coastal visitors

3.7 Visits per month

2.6 Hours per visit

4.6M Coastal activity participants

3.9M Summer activity participants

Summer activity participants

COASTAL VISITATION & PARTICIPATION

NATIONAL TRENDS

NCSS2025: COASTAL VISITATION & PARTICIPATION SUMMARY

Australians love the coast, with approximately 87% of the population living within 50km of the coast. The annual National Coastal Safety Survey (NCSS) explores coastal visitation, activity participation, behaviour, and perceptions of Australian adults (16 years and above) to explore trends around how Australians use our extensive coast. Over the past 12 months, 16 million Australian adults visited the coast 3.3 times each month, spending 2.5 hours on a typical visit. This equates to more than 630 million individual visitations to our coast last year. Males and females visited the coast equally, however males visited more frequently (3.6 visits per month) than females (2.9 visits per month), and participated in coastal activities more, with 7 million participants compared with 6.4 million females.

COASTAL VISITATION

Figure 04

NCSS2025: VISITATION FREQUENCY BY RESIDENCE DISTANCE FROM THE COAST

Australians who live closer to the coast, visit more frequently, with 71% of residents who live less than 10km from the coast visiting at least monthly, compared to only 12% of those who live over 50km from the coast. Furthermore, 32% of residents who live less than 10km from the coast visit three days per week or more.

AUSTRALIAN ADULTS VISITED THE COAST IN 2024/25

2.5 HOURS/VISIT

3.3 VISITS/MONTH 13.4M

COASTAL ACTIVITY PARTICIPANTS 11.1M SUMMER AC TIVITY PARTICIPANTS

8.1M COASTAL VISITORS 3.6 VISITS / MONTH 2.5 HOURS / VISIT 7M

COASTAL ACTIVITY PARTICIPANTS 5.7M

SUMMER A CTIVITY PARTICIPANTS

Figure 05

NCSS2025: WATER ENTRY FREQUENCY

One in seven Australian adults always enter the water when they visit the coast (15%), with a further 27% entering the water most of the time.

7.9M COASTAL VISITORS 2.9 VISITS / MONTH 2.4 HOURS / VISIT 6.4M

COASTAL ACTIVITY PARTICIPANTS 5.4M

SUMMER AC TIVITY PARTICIPANTS

Figure 06

NCSS2025: COASTAL LOCATIONS VISITED

Nine in ten coastal visits were to beaches, with 12% to other coastal areas such as rock platforms or cliffs.

Figure 07

NCSS2025: LAST TEN COASTAL VISITS BY LOCATION

Coastal visitation patterns vary nationally. For NSW residents, 50% of their last ten visits were to a patrolled beach, similar to 46% of QLD residents and 37% of Victorian residents. In contrast, the past ten coastal visits for residents in the Northern Territory, Tasmania, South Australia, and Western Australia were predominantly to unpatrolled locations, either unpatrolled beaches or patrolled beaches outside of patrol hours. One in four visits to the coast by Northern Territory residents were to locations other than a beach, such as rocky areas.

Figure 08

NCSS2025: COASTAL ACTIVITY PARTICIPATION

Participation in and frequency of engaging in coastal activities varies by activity. 57% of Australian adults participated in swimming/wading on the coast in the past year, followed by 16% for boating and 13% for other watercraft, e.g. stand-up paddleboarding, wind surfing, and other paddle craft.

ACTIVITY PARTICIPATION

NCSS2025: DEMOGRAPHICS & FREQUENCY OF PARTICIPATION

Coastal participation varies by activity, sex, age and state/territory. These pages show the number of annual activity participants, the frequency of participation, as well as the proportion of participants by sex, age group, and state/territory. Frequent participants are those who engage in the activity at least once a month, while occasional participation is considered as less than once per month.

4.7M

FREQUENT SWIMMERS 6.8M

OCCASIONAL SWIMMERS

OCCASIONAL SURFERS

1.9M 0.9M FREQUENT PADDLERS 1.7M OCCASIONAL PADDLERS

2.6M

ROCK FISHING

LAND-BASED FISHING

FISHERS 0.75K

OCCASIONAL FISHERS

1.5M

FISHERS

FREQUENT BOATERS 2.3M

OCCASIONAL BOATERS

SNORKELLING

SCUBA DIVING

SEX AGE (YEARS) STATE PARTICIPATION

0.4M FREQUENT RIDERS 0.7M

OCCASIONAL RIDERS

1.1M 0.6M FREQUENT SNORKELLERS 1.9M

OCCASIONAL SNORKELLERS

2.5M 0.2M FREQUENT DIVERS 0.4M OCCASIONAL DIVERS TOTAL 0.6M

COASTAL ACTIVITY PARTICIPANTS

RISK TAKING & SAFETY BEHAVIOURS

2 in 5 female participants feel experienced enough to take risks, compared to 1 in 2 males

Figure 09

NCSS2025: RISK TAKING VS. FOLLOWING SAFETY PRACTICES BY PARTICIPATION FREQUENCY

Overall, female coastal activity participants are more likely to follow safety practices, and less likely to take risks. In contrast, male coastal activity participants are more likely to take risks, and to follow safety practices less often.

Figure 10

NCSS2025: FOLLOWING SAFETY PRACTICES VS. EXPERIENCED ENOUGH TO TAKE RISKS

This play safe index matrix represents risk for coastal activities by participation frequency (frequent - at least once per month; or occasional - less than once per month). It visualises the proportion of participants who feel experienced enough to take risks, against the frequency with which they follow safety practices for each activity. Icons in the upper right hand corner represent the higher risk activity populations, i.e. they take more risk and follow safety practices less often. These include frequent rock fishers and land-based fishers. Icons in the bottom left represent the lower risk activity populations, including occasional boaters, scuba divers, PWC riders, surfers and swimmers/waders.

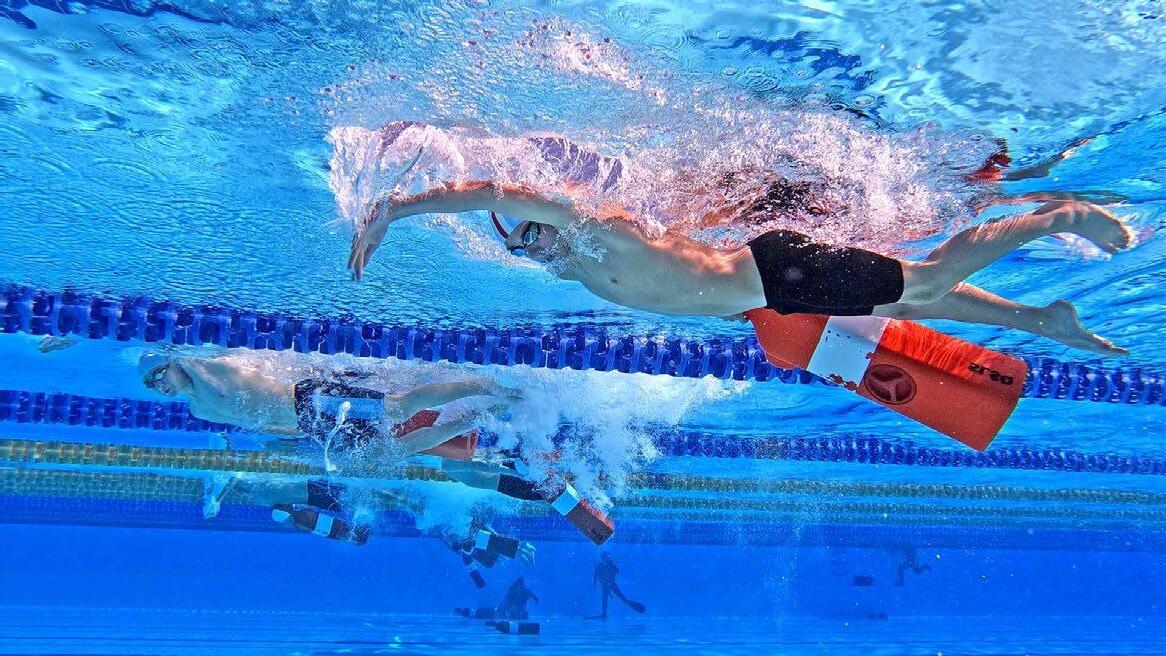

COASTAL SAFETY

SWIMMING ABILITY

Being able to swim is an important factor in reducing drowning risk. However, ability to swim in a pool or other controlled environments does not directly translate across to more dynamic, open environments such as beaches, rivers or in the ocean. Similarly, cost of living pressures and differing demographics influence the prioritisation of participating in formal swimming lessons. Programs such as nippers or rippers provide excellent opportunities to learn about safe swimming and recreating in these natural waterways.

24% Australian-born residents have had open water swim lessons, yet only 16% of residents born overseas.

Figure 11

NCSS2025: ABILITY TO SWIM 50M IN THE OCEAN

Younger residents and those born in Australia are more likely to have had swimming lessons, especially in open environments such as oceans and rivers, compared with older residents.

Figure 12

NCSS2025: SELF-REPORTED ABILITY TO SWIM 50M IN THE OCEAN

Two fifths of Australian adults (40%) believe they can swim 50 metres in open water environments without touching the bottom, but only 28% have done so within the past 18 months. Confidence in ocean swimming ability decreases with age and is also lower in females. Adults of Asian and European backgrounds are the least likely to be able to swim 50 metres and to have done so in the past 18 months.

Figure 13

NCSS2025: HAZARD PERCEPTION OF THE COAST & BEACHES

The coast is perceived as very hazardous by one in four Australians (28%), compared to only 14% for the beach. However, unpatrolled beaches are considered very hazardous by 57% of Australian adults, due to the lack of lifeguards and supervision, rip currents and unsafe or unpredictable water or weather conditions.

Figure 14

NCSS2025: SWIMMING ABILITY BY MOST RECENT SWIMMING LOCATION

Most recent beach visits were to patrolled beaches. Even so, more competent swimmers were more likely to swim at unpatrolled beaches, while less competent swimmers went more to patrolled beaches.

Figure 15

NCSS2025: PERCEIVED RISK OF COMMON COASTAL ACTIVITIES, LOCATIONS & HAZARDS

Rip currents remain the number one coastal hazard for 82% of Australians adults, with fewer considering waves (44%) and surfing (27%) as hazardous. This indicates the varied risk perceptions of similar hazards, and the need to educate coastal visitors about risks associated with different environments, features and activities. N.B. arrows indicate change in perception from last year.

HIGH RISK LOCATIONS

UNPATROLLED BEACHES

57%

Australian adults think unpatrolled beaches are very hazardous

1 in 7

Figure 16

NCSS2025: PERCEPTIONS AND VISITATION OF UNPATROLLED BEACHES

Eastern states have lower unpatrolled beach visitation, more patrolled beaches and a higher proportion of residents that consider unpatrolled beaches to be very hazardous. In contrast, western states/territories and Tasmania have higher unpatrolled beach visitation, fewer patrolled beaches and are less likely to consider unpatrolled beaches as hazardous.

Have experienced difficulty in the water at an unpatrolled beach - 1 in 4 aged 16-24 years

3 in 10

Last coastal visits were to an unpatrolled beach

Figure 17

NCSS2025: REASONS WHY SWIMMERS CHOOSE TO GO TO AN UNPATROLLED BEACH

Swimmers primarily choose to swim at unpatrolled beaches as they perceive the risk as low and are confident or familiar with the location. Reasons to visit unpatrolled beaches differs by population group. Males and confident swimmers are typically more confident in their ability, while females and weaker swimmers do not plan to go deep into the water. Convenience is more important to younger swimmers and weekly visitors, while monthly visitors consider mobile phone signal and the presence of public rescue equipment more important than other groups.

MARINE STINGERS

Marine stingers, especially those found in tropical waters, are consistently rated as the second highest coastal hazard after rip currents. This is perhaps not surprising when one in five Australian adults have been stung by a marine stinger, mostly by bluebottles and while swimming.

Since 2014/15, surf lifesavers and ALS lifeguards have treated more than 440 thousand stings at the beach, with many more being selftreated or even requiring emergency care. SLSA has two significant marine stinger research projects looking to mitigate community marine stinger risk.

The BluebottleWatch project (with UNSW Sydney) is developing a predictive model to identify days that are likely to have a high-risk of bluebottle presence. This is possible because bluebottle movements are driven largely by wind and, to some degree, ocean currents.

The Australian Box Jellyfish First Aid Research Project is a collaborative project (led by SLS with James Cook University, and the University of Hawaii) seeking to clarify national jellyfish first aid guidelines to improve consistency, and to optimise tropical marine sting management.

2ND HIGHEST-RATED COASTAL HAZARD 1 in 5

AUSTRALIANS HAVE BEEN STUNG BY A MARINE STINGER

39% ARE VERY/EXTREMELY CONCERNED ABOUT BEING STUNG BY A JELLYFISH

66%

WERE STUNG BY A BLUEBOTTLE 10%

WERE STUNG BY POTENTIALLY LIFE-THREATENING CUBOZOAN JELLYFISH

Figure 18

NCSS2025: STUNG BY WHICH MARINE STINGER? Bluebottles were responsible for 66% of the marine stings reported, followed by blubbers (10%) and jimbles (6%). Potentially life-threatening marine stingers (Irukandji-syndrome and box-jellyfish species) were also reported.

Figure 19

NCSS2025: ACTIVITY WHEN STUNG Most adults were swimming (64%) and wading (16%) at the time they were stung.

1 IN 3 RECEIVED TREATMENT

Figure 20

NCSS2025: STING TREATMENT PROVIDER

Of the one in three stings that received treatment, almost half (47%) were treated by lifesaving services, while 26% required treatment from emergency care providers (ambulance, doctor or hospital).

Figure 21

2015-25: ANNUAL MARINE STINGS TREATED BY SLS & ALS

Lifesaving statistics have revealed SLS services have treated 441,517 since 2014/15. This is an annual average of 40,138 marine stings treated, with significant interannual variability observed.

26%

AMBULANCE/DOCTOR/HOSPITAL

FRIEND/FAMILY MEMBER 25% 47% SURF LIFESAVERS/LIFEGUARDS

19% SELF TREATED

Figure 22

NCSS2025: CHANGES IN HAZARD PERCEPTION OF MARINE STINGERS Community perception of marine stingers as a coastal hazard has increased since 2015.

RIP CURRENTS

KNOWLEDGE, BEHAVIOURS & SKILLS

1 in 5

AUSTRALIAN ADULTS HAVE BEEN UNINTENTIONALLY CAUGHT IN A RIP CURRENT

1 in 2

ADULTS ARE NOT CONFIDENT TO IDENTIFY A RIP CURRENT 49% ARE VERY/EXTREMELY CONCERNED ABOUT GETTING CAUGHT IN A RIP CURRENT

RIP-RELATED DROWNING DEATHS IN 2024/25

82%

CONSIDER RIP CURRENTS VERY/ EXTREMELY HAZARDOUS 30

Prevalence of getting unintentionally caught in a rip current differed by swimming ability, where more competent swimmers were more likely to have been caught compared to weaker swimmers. This risk is likely due to different exposure to the rip current hazard.

Figure 24

NCSS2025: RIP CURRENT ESCAPE METHODS

Most Australian adults who have been unintentionally caught in a rip current managed to self-rescue (66%), while 30% required assistance from a surf lifesaver, lifeguard or a bystander to return to shore.

Figure 25

NCSS2025: CONFIDENCE & ABILITY TO IDENTIFY RIP CURRENTS

Of the 46% of Australian adults who are confident they can spot a rip current, less than half (45%) were able to correctly identify a rip current when tested using the marked up images.

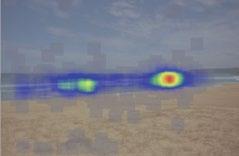

IDENTIFYING RIP CURRENTS

The NCSS2025 trialled a new method to test rip current identification skills. Respondents were divided into two groups, one group were asked to identify a rip current by highlighting anywhere on an image of a beach, while the other group was given four marked potential rip current locations. For the first group with no marked prompts to suggest where a rip current could be, rip current identification ability was lower and varied substantially, with only 6% correctly identifying the rip current in both images, while 36% of respondents in the second group correctly identified the rip current in both images. These results revealed the concerningly low level of rip current understanding/literacy among Australian adults, reinforcing the need for stronger rip current education and drowning prevention strategies. This result also reaffirms the relevance of existing swim between the flags messaging, highlighting the important role beach lifesaving services play and that swimming between the red and yellow flags is the safest place on the beach.

Figure 26

NCSS2025: RIP CURRENT IDENTIFICATION METHODOLOGIES

Participants tested using the new method were less likely to correctly identify the rip in both images, with only 6% able to do so, compared with the original question style for which 36% of respondents succeeded. Additionally, a greater proportion of respondents to the new method were not sure (25%) compared to 12% with the original method.

27

NCSS2025: CORRECT IDENTIFICATION BY RIP CURRENT KNOWLEDGE, EXPERIENCE & SWIMMING ABILITY

Australian adults who have been unintentionally caught in a rip current, are confident to identify a rip current, or consider themselves competent ocean swimmers were better at accurately identifying rip currents than average. This shows that rip current identification skills are improved with greater exposure and experiences with rip currents.

Figure

New testing method

New testing method (response)

Original testing method

SECTION 2 CAPABILITY

316 SURF LIFE SAVING CLUBS

49,750 PROFICIENT MEMBERS

1,469,465 VOLUNTEER PATROL HOURS

8,207 RESCUES PERFORMED

238 AUSTRALIAN LIFEGUARD SERVICES

9 WESTPAC LIFESAVER RESCUE HELICOPTER SERVICES

VALUE TO COMMUNITY

$9,000,003,752

CAPABILITY

CORE SERVICES & OPERATIONAL OVERVIEW

Surf Life Saving’s (SLS) position as Australia’s leading coastal safety authority is based on the national delivery of its essential services. SLS provides these core services through Surf Life Saving Clubs (SLSCs), Support Operations, and the Australian Lifeguard Service (ALS), who are responsible for coastal patrols, surveillance, and search and rescue (SAR) operations. The ability of SLS to carry out these vital functions, including its support in SAR operations, after-hours incidents, and natural disasters, is well-regarded by emergency services and disaster response agencies. The community and partner organisations are safeguarded through our dedication to high-quality training, with 41,707 Bronze Medallion and 8,043 Surf Rescue Certificate holders across 316 Surf Life Saving Clubs.

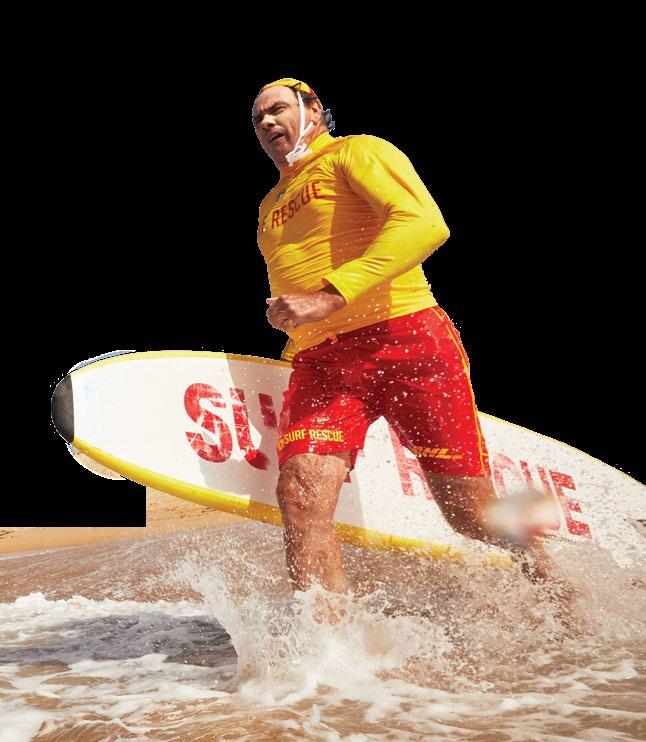

VOLUNTEER SURF LIFESAVERS

Surf Life Saving Australia's (SLSA) success stems from our robust volunteer base, comprising over 207,000 members, making it one of the largest volunteer organisations globally. This diverse and skilled volunteer workforce is vital to SLSA’s achievements. In the past year, 46,307 volunteers contributed 1,469,465 hours of service through patrols. During these patrols, volunteers performed 5,371 rescues, undertook 508,079 preventative actions, and provided 34,394 first aid treatments.

Surf lifesavers are equipped with specialised gear and equipment and trained to use it effectively in various conditions. Rescue boards and tubes are primary tools for surf lifesavers on patrol, complemented by 1,199 inflatable rescue boats (IRBs) that enhance our service reach and capabilities. IRBs enable swift navigation through inshore surf, allowing surf lifesavers to cover greater distances for extended periods. Rescue boards are the most frequently used equipment for rescues (see Figure 34). Land-based roving patrols enhance our aquatic services and are a crucial part of SLSA’s drowning prevention strategy. A fleet of 417 side-byside (SSV) vehicles and 231 4WD vehicles support patrols to monitor coastal locations beyond supervised patrolled areas. Aerial surveillance is facilitated by Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs; Figure 37), broadening our reach and effectiveness. SLSA’s capabilities extend beyond the iconic red and yellow flags, with 226 rescue watercraft (RWCs) and two jet rescue boats (JRBs) allowing for prompt responses in challenging coastal conditions. The organisation also operates four offshore rescue boats (ORBs) and five rigid-hull inflatable boats (RIBs) for offshore rescues and extended surveillance and SAR

operations.

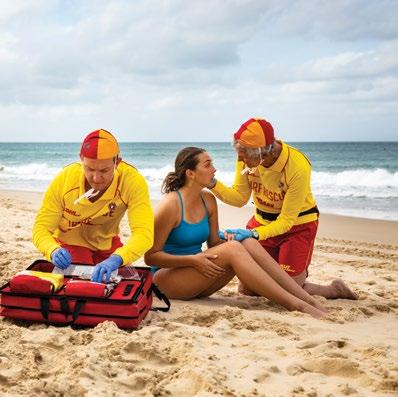

AUSTRALIAN LIFEGUARD SERVICE

The Australian Lifeguard Service (ALS), a division of SLSA, is the largest professional lifeguard provider in Australia, operating 238 services at beaches and pools. With over 1,350 lifeguards employed on full-time, part-time, and casual contracts, the ALS complements SLSA’s volunteer services to provide comprehensive, year-round safety, including 365-day coverage. The ALS logged 483,020 service hours, performed 2,836 rescues, executed 1,686,625 preventative actions, and administered 31,548 first aid treatments. The ALS delivers value by avoiding duplication of assets and efficiently sharing resources with SLSC's. ALS lifeguards are equipped with specialised gear and trained to use it effectively in various conditions. RWCs serve as a primary lifesaving tool in aquatic environments. Their operations are supported by 69 vehicles and 49 RWCs. Lifeguard services managed internally by local governments are not included in this report.

FLOOD & SWIFTWATER RESCUE

In addition to our core coastal safety role, SLSA provides valuable support to communities and emergency services during major flood events. Building on members’ expertise in rescue boat operations, first aid, communications, and community engagement, lifesavers can be trained and equipped to assist in flood response. SLSA’s contribution is focused on surge capacity and support functions, including assisting with evacuations, conducting welfare checks, supporting supply drops, and working alongside lead emergency agencies during disasters. This role is underpinned by nationally consistent training and equipment standards developed through the Centre of Excellence for Flood and Swiftwater Rescue.

Importantly, SLS does not operate as a primary flood rescue agency, but as a trusted partner that can bolster existing emergency response systems. This collaboration ensures a stronger, more coordinated approach when large-scale flood events place significant demand on emergency services.

WESTPAC LIFESAVER RESCUE SERVICES

The nine Westpac Lifesaver Rescue Helicopters and one Offshore Rescue Boat that operate around Australia under the banner of SLS continue to extend capability, response, and reach, providing essential services to more locations in times of need.

The aircraft enable rapid response to areas that would otherwise take several hours to reach by road or water. When lives are on the line, minutes matter and seconds count. This is where the Westpac Lifesaver Rescue Helicopters make a difference arriving in a short period of time and commencing actions to reduce injury and loss of life. In many situations, the helicopters also reduce the risks that members using vehicles or Rescue watercraft (IRBs/RWCs) might otherwise be exposed to.

In the past twelve months, the helicopters have performed more than 2,000 flights, with over 500 of these being Search and Rescue (SAR) missions. Close to 70 flights were undertaken in response to shark detections, either to mitigate risks to water users or to provide assistance where an encounter had occurred. Natural disasters, such as floods, have also been part of the mission tasking. Almost 4,000 preventative actions were undertaken, nearly 200 rescues performed, and a further 214 people treated for first aid, ranging from minor injuries through to CPR. In addition, the Westpac Offshore Rescue Boat was tasked for more than 150 hours including 11 search and rescue missions, six search and rescue exercises with external agencies and water safety for five major community events. Over the past 51 years, the Westpac Lifesaver Rescue services have become an essential component supporting the work of SLS across the country.

SURF LIFE SAVING SERVICES

2024/25: SURF LIFE SAVING SERVICES

SLSA supports 557 services around Australia. There are 316 SLSCs and three affiliated marine rescue services, with 129 in New South Wales, 58 in Queensland, 57 in Victoria, 31 in Western Australia, 23 in South Australia, 15 in Tasmania and three in the Northern Territory. The ALS provides 238 lifeguard services around Australia, with 96 in New South Wales, 70 in Queensland, 42 in Victoria, 18 in Western Australia, nine in the Northern Territory, two in Tasmania and one in South Australia.

2,194,704

VALUE TO COMMUNITY

65,942

1,381,776

8,207 RESCUES

9,000,003,752

483,020

1,952,485

87,689

RESCUES

Figure 30

2024/25: RESCUES PER LOCAL GOVERNMENT AREA

SLS lifesavers, lifeguards and lifesaving services performed 8,207 rescues across 117 local government areas around Australia.

Key to Rescues per LGA

< 14 Rescues

15 - 49 Rescues

50 - 149 Rescues

150 - 399 Rescues

> 400 Rescues

1,072

58 170

2,355

3,494

1,011

47

PREVENTATIVE ACTIONS

Figure 31

2024/25: PREVENTATIVE ACTIONS PER LOCAL GOVERNMENT AREA

SLS lifesavers, lifeguards and lifesaving services performed 2,194,704 preventative actions across 117 local government areas around Australia.

Key to Preventative Actions per LGA

< 1,499 Actions

1,500 - 4,999 Actions

5,000 - 19,999 Actions

20,000 - 99,999 Actions

> 100,000 Actions

10,579

113,724

6,855

617,666

356,236

1,087,710

1,934

FIRST AID

32

2024/25: FIRST AID PER LOCAL GOVERNMENT AREA

SLS lifesavers, lifeguards and lifesaving services performed 65,942 first aid treatments across 117 local government areas around Australia.

Key to First Aid Incidents per LGA

< 49 Incidents

50 - 349 Incidents

350 - 649 Incidents

650 - 2,999 Incidents

> 3,000 Incidents

3,007

233

35,142

851

24,944

1,621

144

RESOURCE CAPACITY

SLS has 49,750 proficient members, 41,707 members are Bronze Medallion holders and 8,043 members hold Surf Rescue Certificates (see below). There were a total of 46,307 members who performed a patrol. Of these patrolling members, 60.4% were male, 39.5% were female and 36 members identified with a non-binary gender (<1%; see above). Members also hold other lifesaving awards, equating to 72,430 additional lifesaving qualifications (See Figure 33). This highlights the extent of training our surf lifesavers undertake to ensure they are highly skilled first responders.

49,750

41,707

BRONZE MEDALLION

8,043 SURF RESCUE CERTIFICATE

* Totals include member holders of multiple similar awards.

Figure 34

2024/25: EQUIPMENT USED IN RESCUES

Rescue boards were used in 39% of rescues, followed by rescue tubes (19%) and rescue watercraft (RWCs; 18%).

EMERGENCY FLOOD DEPLOYMENTS

337 SLS personnel trained for flood and disaster response

Figure 35

75 PERSONS RESCUED/ EVACUATED

10,947 HOURS DEPLOYED

SLS PERSONNEL DEPLOYED

2024/25: SLS EMERGENCY DISASTER RESPONSE

SLS conducted 24 emergency flood deployments across key regions including Northern Rivers, Coffs Harbour, Port Macquarie, Taree (NSW), Townsville/Ingham (QLD), Barwon (VIC), and multiple locations in Tasmania. A total of 296 SLS personnel contributed over 10,947 hours to disaster response operations, resulting in the rescue or evacuation of 75 people. To strengthen capability, 337 members were trained specifically for flood and disaster response operations in the 2024/25 season.

ASSET CAPABILITY

2024/25: SLS MAJOR ASSET LOCATIONS & SERVICE RANGE

Key to Asset Location

Rescue Water Craft (RWC)

Jet Rescue Boat (JRB)

Rigid-hull Inflatable Boat (RIB)

Offshore Rescue Boat (ORB)

Westpac Lifesaver Rescue Helicopter

SLS maintains a fleet of 275 rescue watercraft (RWC), two jet rescue boats (JRB), five rigid-hull inflatable boats (RIB), four offshore rescue boats (ORB), and nine rescue helicopters. Their locations and service ranges are depicted on this map. 50

AVIATION SERVICES

UNMANNED AERIAL VEHICLE OPERATIONS

Figure 37

2024/25: UAV CAPACITY

SLS UAV operations are a critical asset to lifesaving, with 39,065 flights conducted, 36,128 dedicated to shark surveillance, and the remainder supporting beach surveillance, search and rescue, and disaster response. Covering more than 164,586km, these operations are delivered by 761 nationally accredited pilots, operating within State UAV services as well as 95 clubs across the country.

39,065

NUMBER OF FLIGHTS

164,586 KMS FLOWN

761

36,128

SHARK SURVEILLANCE

AVIATION CAPABILITY

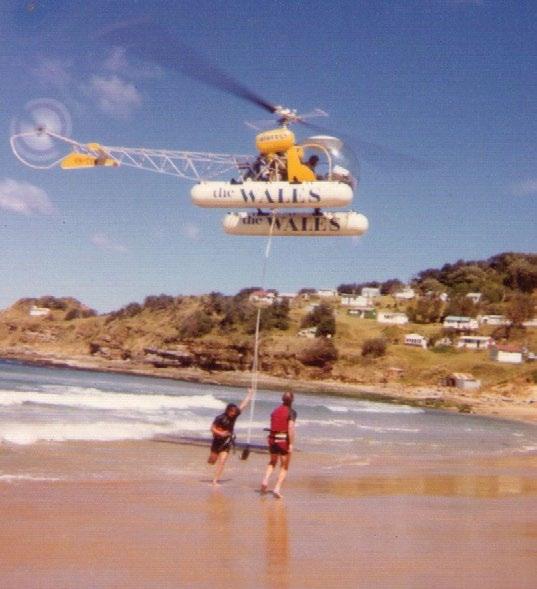

WESTPAC LIFESAVER RESCUE HELICOPTER

The Westpac Lifesaver Rescue Helicopters are recognised not only across Australia but also internationally. Initially founded in 1973 by SLSA, the service has celebrated over 50 years of operations and performed more than 100,000 missions in this time. Importantly, every mission undertaken by services under SLS have been provided at no cost to those we have rescued or assisted.

From humble beginnings, the service first began on 29 September 1973 at Maroubra. This initiative began with Ian Badham and a group of SLS members exploring how rescues could be more time effective and able to be delivered in large seas. With the support of the Wales Bank (later Westpac) and a $25,000 donation, the service launched a trial which, due to the success, quickly evolved and expanded.

Westpac has been with us since the beginning. Thanks to this partnership, there are now nine Westpac Lifesaver Rescue Helicopters across Australia and one Westpac Lifesaver Offshore Rescue Boat in the Northen Territory. Additionally, there are another six Westpac Rescue Helicopters aligned to Ambulance and Police operations in Northern NSW and Tasmania.

Behind every service is a dedicated team ensuring the Westpac Lifesaver Rescue Helicopters are always ready when needed. From pilots, air and rescue crew, through to engineers and administration and support staff and volunteers, it is a team effort that keeps the helicopters flying. While various state governments provide some support, donations and fundraising remain critical to keeping the services in the air and ensuring that no one ever has to pay to be rescued or assisted.

Westpac Lifesaver Rescue Helicopter services around the country have attended numerous major events including but not limited to;

• Granville train disaster

• Milperra bikie massacre

• Thredbo landslide – Stuart Diver

• Sydney to Hobart tragedy –6 lives lost

• NSW & Queensland floods (over several years)

• NSW bushfires

• Shark attacks across South Australia, Western Australia, New South Wales and, Queensland.

SEASON 2024/25 SUMMARY

2,096

TOTAL NUMBER OF MISSIONS

839 SHARK SIGHTINGS

1,372 COASTAL PATROL FLIGHTS

519 SAR (SEARCH & RESCUE)

29 NATIONAL DISASTER FLIGHTS (FLOODS)

194 RESCUES/RECOVERY

214 FIRST AID

3,903 PREVENTATIVE ACTIONS

Each day the services across the country attend to many varied incidents, helping those in need. From wayward surfers, swimmers caught in rips, to rock fishers swept into the ocean, capsized vessels and coastal hazards identification (such as rip currents and shark sightings) –there is always something happening along our coast. Some services go even further, responding to flood events, assisting communities in times of need, searching for missing people in bushland, mountains and alpine regions.

The Westpac Lifesaver Rescue Helicopters support not only surf lifesavers and lifeguards on the beach, but also a wide range of agencies including the Police, Ambulance, AMSA (Australian Maritime Safety Authority), State Emergency Services (SES), National Parks, Marine Rescue, Rural Fire Services, Fire and Rescue, and more. When it comes to saving lives, it is essential we all work together.

INNOVATION DAY

BRIDGING LOCAL EXPERTISE WITH GLOBAL TECHNOLOGY IN LIFESAVING

Stretching thousands of kilometres, Australia’s coastline demands both resilience and adaptability. As beach conditions shift and coastal communities expand, SLS must evolve its existing systems to remain responsive and effective. The SLS Innovation Day 2024 held at Wanda SLSC, brought together lifesaving experts from around the country, technical specialists, and emergency service leaders to examine how emerging technologies can support and enhance rescue capabilities through practical testing, observation, and critical feedback.

A diverse range of technologies were showcased, spanning from wearable automatic flotation technology to autonomous surveillance solutions. Motorised rescue equipment and personal GPS trackers focused on enhancing visibility, safety, and real-time location tracking for lifesaving personnel. Shore-based infrastructure, including emergency response beacons, were also demonstrated to support communication and rapid incident response in unpatrolled locations.

Autonomous and remote controlled innovations also featured prominently. These included innovative unmanned aerial vehicles for coastal surveillance, AI-powered shoreline monitoring systems, and remote rescue craft capable of assisting during complex incidents. Sustainable transport options such as electric powered bikes and motors were introduced as lower emission alternatives for patrol and beyond the flag’s response.

extend not replace the capability of skilled personnel. Human oversight, adaptability, and robust training remain essential.

Sustainability emerged as a strategic priority across several demonstrations. The introduction of electric motors suggested the potential for operational and environmental gains. However, practical considerations such as charging infrastructure, maintenance, and deployment logistics were identified as necessary areas for further development.

Innovation Day reinforced the value of iterative learning, collaboration, and field-based refinement.

A key insight from the day’s activities was the critical role of operational context. Technologies must be shaped by the practical needs of those using them. Lifesaving experts participating in trials identified both strengths and limitations in the innovations presented, particularly around durability in harsh marine conditions, integration with existing workflows, and battery performance.

Some emerging systems, such as AI detection platforms and remote rescue craft, demonstrated real potential to assist with mass rescue and surveillance operations. However, participants emphasised that technology must

Rather than focusing on any single breakthrough, the Innovation Day reinforced the value of iterative learning, collaboration, and field-based refinement. The event highlighted that effective innovation stems from collaboration between the manufacturers present and lifesaving personnel, and that successful solutions must be tailored to meet the varied demands of real-world coastal environments. The outcomes of this collaboration were presented at AFAC2025, and its success was highly commended for building connections.

By combining lifesaving personnel with emerging global technologies, the lifesaving sector can strengthen its ability to prevent, respond to, and adapt to coastal risks. As SLS works toward reducing coastal drowning deaths, fostering this culture of innovation will remain critical to building a safer, more responsive future for all beachgoers.

MOST NOTABLE INNOVATIONS INCLUDED:

ROBODUCKY

Remote controlled rescue craft

ELECTRIC OUTBOARDS

Surveillance technology

ENABLERS OF PROGRESS

• sector-wide and multidisciplinary collaboration

• robust trial and testing approaches

• accessible pathways for user feedback

LIFESAVING CPR

A TARGETED EDUCATIONAL PROGRAM TO IMPROVE CPR DELIVERY IN SURF LIFE SAVING

Lifesaving CPR is an evidence-based, standardised, and simplified approach designed to improve survival rates from cardiac arrest, both on and off the beach.

BACKGROUND

Each year, ~26,000 out-of-hospital cardiac arrests (OHCA) occur in Australia, with only 13% of patients surviving to return home. Survival rates vary based on factors like early provision of cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) by bystanders, AED use, and ambulance response times.

On average, SLSA members respond to 65 cardiac arrests each year while on duty and often also act as first responders in community settings, with many patients requiring CPR. Recognising its broad reach and lifesaving mission, SLSA developed a CPR quality improvement program aimed at increasing survival outcomes.

APPROACH

A pilot study was conducted with qualified volunteer surf lifesavers. Participants underwent a tailored educational intervention based on the Resuscitation Academy’s HighPerformance CPR model, adapted for the Australian surf lifesaving context and branded “Lifesaving CPR.” The educational intervention included theory and practical elements of CPR. The practical element focused on key measurements of improvement, including team-based working, structured approach to CPR, and a focus on technical aspects of skills and individuals. The intervention included:

A 2-MINUTE CPR PERFORMANCE ASSESSMENT (PRE-TRAINING)

THEORY AND PRACTICAL TRAINING

A REPEAT 2-MINUTE CPR ASSESSMENT (POST-TRAINING)

RESULTS

From 159 total participants, 58% completed both the quiz and face-to-face training (n=93) and were included in analysis. Post-training assessments showed statistically significant improvements in CPR performance, including:

INCREASED CHEST COMPRESSION FRACTION

IMPROVED COMPRESSION RATE

REDUCED TOTAL PAUSE TIME AND LONGEST PAUSE

LIFESAVING CPR

KEY AIMS OF LIFESAVING CPR

DISCUSSION

This study showed that targeted training programs can improve CPR metrics, which in turn support better outcomes for OHCA patients on our beaches and within our community. These results prompted broad adoption of Lifesaving CPR across SLS, with all SLS states and territory incorporating the updated techniques into their 2025/26 season Skills Maintenance programs and into new courses.

SLSA training resources for CPR have been updated for Lifesaving CPR, including the Public Safety Aquatic Rescue Training Manual, the Bronze Medallion and Surf Rescue Certificate CPR assessment tasks and online learning.

Footnote:

Adapted from: Reid D, Dixon KM, Equid L, Jacobson C, Lawes J, Hare-Boyd T, Chubb A, Murphy M, Treloar K, Simon P, Douglas N. (2025) Lifesaving Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation: A Pilot Evaluation of a Targeted Educational Intervention to Improve Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation Provision in Volunteer Surf Lifesavers. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/ S0736467925001738

SECTION 3 COASTAL MORTALITY

154 DROWNING DEATHS

COASTAL MORTALITY

2024/25: YEAR IN REVIEW

Figure 38

2024/25: COASTAL DEATH OVERVIEW

Overall, 239 coastal deaths were recorded in 2024/25, with a mortality rate of 0.87/100,000 pop.

Drowning deaths in coastal environments (n=154) accounted for 43% of the national drowning burden (n=357). These numbers are the highest ever recorded, with coastal drowning deaths 3% above last year and 21% above the ten-year average. In addition to the 154 coastal drowning deaths, 85 other coastal fatalities were recorded, 58% of which were unintentional.

The Australian coastline claimed 239 lives in 2024/25, a 7% decrease from 2023/24 (n=258), and a 1% increase from the ten-year average (n=236).

Males remained a high-risk demographic (87%), 6.8 times more likely to drown compared to females. Older Australians have again emerged as the highest risk cohort, with one in four coastal drowning decedents aged 60-69 years (25%) and 55+year olds comprising 55% of the coastal drowning burden.

Beaches claimed 82 lives, all occurring outside patrol times or at unpatrolled beaches away from services. Swimming/wading was the most common activity prior to drowning (32%), followed by boating/PWC (14%), then equally by snorkelling and falls (9% each).

These numbers may have been far worse if not for the incredible efforts of SLS members who are often on duty to protect beachgoers. This section explores these deaths to inform operations and better understand the mortality burden our members and community face.

Figure 39

2024/25: COASTAL MORTALITY BY STATE

NSW recorded the highest number of coastal deaths (n=89; 58% due to drowning) , followed by WA (n=46; 59% due to drowning), then QLD (n=43; 72% due to drowning). WA also recorded the highest mortality rate (1.53/100,000 pop.), followed by SA (1.27/100,000 pop.). Unintentional drowning was the most prevalent coastal death type (64%, n=154).

Coastal drowning

Coastal fatality

Coastal drowning or fatality

27:19

2

18:6

31:12

52:37

20:9

6

40

2024/25: COASTAL DEATH LOCATIONS

Red and yellow numbers indicate the number of drowning deaths and fatalities respectively for each state. For states with small numbers, black numbers indicate combined drowning deaths and other fatality numbers.

2024/25: LOCAL GOVERNMENT AREA BLACKSPOTS

A blackspot is an area where a concentration of incidents are recorded and have a high probability or risk of reoccurrence. These LGAs below recorded the highest number of fatal coastal incidents (both drowning deaths and other fatalities) in 2024/25.

NSW: Northern Beaches, Central Coast, Kiama, Woollahra, Port Macquarie-Hastings, Randwick, Wollongong

QLD: Gold Coast, Queensland Parks and Wildlife Service, Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority, Moreton Bay, Mackay, Sunshine Coast, Brisbane

VIC: Parks Victoria, Greater Geelong, Mornington Peninsula, Bayside, Kingston

WA : Department of Biodiversity, Conservation & Attractions, Stirling, Cockburn, Carnarvon, Joondalup, Wanneroo

TAS: Clarence, Glamorgan-Spring Bay

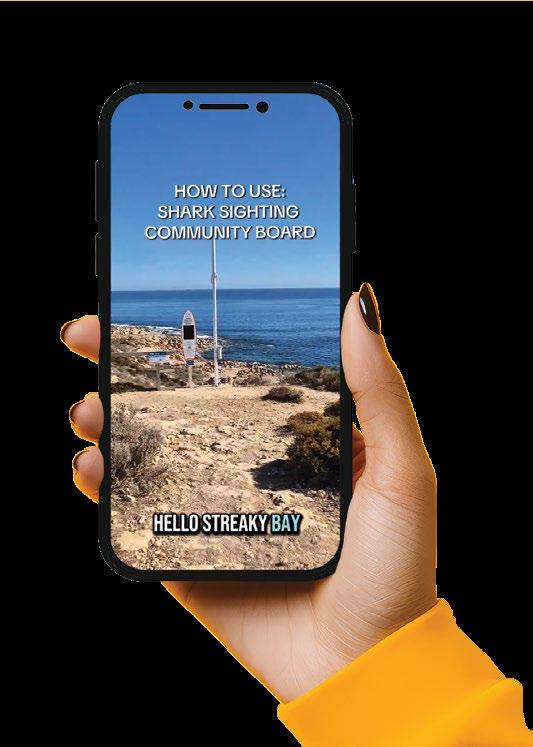

SA : Kangaroo Island, Streaky Bay

NT: Palmerston, East Arnhem

Figure

COASTAL DROWNING

2024/25: YEAR IN REVIEW

The following pages present a deeper analysis of coastal drowning deaths that occurred this year. These descriptive analyses help to understand circumstances around incidents and guide the development of education and awareness programs, initiatives and actions to reduce coastal incidents into the future.

KEY DEMOGRAPHICS

COASTAL DROWNING DEATHS

DROWNING RATE/100,000 POP. 0.56

55% 55+ YEAR OLDS 1 in 4 60-69 YEARS OLD 13%

Males drowned at a rate 6.8x higher than females

Coastal drowning risk was 3.3x higher on public holidays and long weekends

Figure 41

2024/25: COASTAL DROWNING BY AGE & SEX

The highest number of coastal drowning deaths were recorded among 60-69 year olds (25%, n=38), with 55% aged 55+ years (n=85). The highest age-specific drowning rate was among 65-69 year olds (1.53/100,000 pop.), followed by 75-79 year olds (1.21/100,000 pop.). Males were 6.8 times more likely to drown than females (0.99/100,000 males vs. 0.14/100,000 females), representing 87% of drowning deaths (n=134). Medical co-morbidities were reported in at least 23% of coastal drowning deaths (n=35), which could be higher with COD unknown for 69% of cases.

DEMOGRAPHICS HIGHLIGHT

32% SWIMMING/WADING

Figure 42

RIP CURRENTS 53% BEACH 71% >1KM FROM SLS 9% ALCOHOL/DRUGS

33% MEDICAL CO-MORBIDITY

2024/25: 55+ YEAR OLD DROWNING

In 2024/25, 85 drowning decedents were aged 55 years or older, an increase of 29% from last year (n=66) and 70% from the 10-year average (n=50). Most decedents were male (88%), one third were alone when they drowned and at least 33% involved medical co-morbidities.

Figure 43

2024/25: DROWNING DISTANCE TO SURF LIFE SAVING SERVICE

Almost three in four drowning deaths occurred more than 1km from a Surf Life Saving service (73%, n=112). All incidents occurred outside of the red and yellow flags, patrol times, or at unpatrolled locations.

Figure 44

2024/25: DROWNING BY ACTIVITY

Swimming and wading recorded the most drowning deaths (32%, n=50), followed by boating/PWC (14%, n=21), then by snorkelling and falls (9%, n=14 each). Swimming and wading drowning deaths increased by 22% compared to the 10-year average.

1 in 3 beach drowning deaths were due to rip currents

Figure 45

2024/25: REMOTENESS CLASSIFICATION OF DROWNING LOCATION

Almost two in three incidents occurred in regional/remote areas (57%, n=88), 40% in major cities, and 3% offshore. The remoteness classification of an incident location was coded to the Australian Statistical Geographical Standard of Remoteness Areas.

Figure 46

2024/25: DROWNING BY LOCATION & RIP CURRENT DROWNING AT BEACHES Beaches were the leading location for coastal drowning deaths (53%, n=82), followed by rock/cliff (20%, n=31), then offshore (15%, n=23). Rip currents were known to contribute to more than one in three beach drowning deaths (37%, n=30), however, this may be higher as rip involvement remains unknown for 40% of beach cases (n=33).

Figure 47

2024/25: RESIDENCE DISTANCE TO DROWNING LOCATION

Most decedents lived locally to the drowning location (23%, n=35), followed by those who were intrastate visitors (20%, n=32).

47%

OCCURRED IN THE AFTERNOON (12-6PM)

Figure 48

2024/25: DROWNING BY DAY

Two in five drowning deaths occurred on a weekend (37%, n=54), with weekend drowning rates 1.35 times greater than during the week. Four in five drowning deaths occurred between 6am and 6pm (84%, n=129), most commonly in the afternoon (12-6pm; 47%, n=57).

Figure 49

2024/25: DROWNING BY MONTH

Most coastal drowning occurred during summer (40%, n=62), 20% above average. December (17%, n=26) and April (16%, n=25) recorded the highest number of drowning deaths, 127% and 53% above average respectively.

COASTAL DROWNING LOCATIONS

2015-25: TEN-YEAR ANALYSIS

Figure 50

2015-25: COASTAL DROWNING TRENDS (N=1,301)

Annual coastal drowning trends are illustrated above. Tragically, 154 coastal drowning deaths were recorded in 2024/25, 21% above the 10-year average and the highest number since our records began in 2004/05. The 2024/25 coastal drowning rate (0.56/100,000 pop.) was above average (0.50/100,000 pop.), but below 2015/16 (0.58/100,000 pop.).

2015-25: KEY DEMOGRAPHICS

AVERAGE DROWNING DEATHS

DROWNING RATE/100,000 POP.

16% 20-29 YEARS OLD

17% 60-69 YEARS OLD

Figure 51

2015-25: DROWNING ACTIVITY COMPARED TO 2024/25

Drowning incidence varies by activity and over time. Since 2015, swimming and wading has recorded the most drowning deaths (32%, n=418), followed by boating and PWC (19%, n=247), then snorkelling (9%, n=121).

Figure 52

37% of beach drowning was due to rip currents

2015-25: DROWNING DISTANCE FROM A SURF LIFE SAVING SERVICE

Three in four drowning deaths (73%, n=953) occurred greater than 1km from a Surf Life Saving service.

Figure 53

2015-25: DROWNING BY LOCATION

Beaches remain the leading drowning location (49%, n=644), followed by offshore (21%, n=269), then rock/cliff locations (17%, n=221). One in three beach drowning deaths are due to rip currents (37%, n=232), although this is likely higher with 34% of cases unknown (n=217) .

Figure 54

2015-25: REMOTENESS CLASSIFICATION OF COASTAL DROWNING

One in two drowning deaths occurred in a regional/remote area (55%, n=722), followed by major cities (39%, n=503), then offshore waters (6%, n=79). The remoteness classification of an incident location was coded to the Australian Statistical Geographical Standard of Remoteness Areas.

Figure 55

2015-25: RESIDENCE DISTANCE TO DROWNING LOCATION

Most decedents were intrastate visitors to the drowning location (n=383), followed by local (n=346) and nearby residents (n=301).

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

Figure 56

2015-25: VISITOR CATEGORY OF DECEDENT

Most decedents were Australian residents (n=923) followed by short term visitors (n=82) and international students (n= 42).

COUNTRIES OF OVERSEAS-BORN DECEDENTS

Figure 57

2015-25: BIRTH CONTINENT OF DECEDENT

Birth continent is known for 87% of coastal drowning deaths (n=1,126), of these 46% of decedents were born in Australia (n=595), 20% were born in Asia (n=266), and 12% born in Europe (n=162).

58

2015-25: DROWNING BY TIME

Most coastal drowning deaths occurred in the afternoon (45%, n=583), followed by the morning (30%, n=393). The highest density have occurred between 10am and 5pm (52%, n=681; shaded area). Incident time was unknown for 5% of cases (n=71), which were excluded from analyses.

38% OCCURRED ON THE WEEKEND 41% OCCURRED IN SUMMER

59

2015-25: DROWNING BY MONTH & DAY

Most coastal drowning deaths occurred during summer (41%, n=529; Dec-Feb), followed by autumn (25%, n=327; Mar-May). By month, January has recorded the highest number (16%, n=202), then December (14%, n=186). A disproportionate number of coastal drowning deaths occurred on weekend days (38%; n=489), with drowning risk 1.5 times greater on the weekend.

Figure

Figure

COASTAL DROWNING LOCATIONS

18

89

273

469

UNINTENTIONAL COASTAL FATALITIES

2015-25: TEN-YEAR ANALYSIS

Figure 60

2015-25: COASTAL FATALITY TRENDS (N=571)

Annual unintentional coastal fatality trends are illustrated above. The 2024/25 coastal fatality total (n=49) and rate (0.18/100,000 pop.) were below the 10-year average.

2015-25: KEY DEMOGRAPHICS

AVERAGE COASTAL FATALITIES 59 FATALITY RATE/100,000 POP.

22% 55-64 YEARS OLD

21% 65-74 YEARS OLD

Figure 61

2015-25: COASTAL FATALITY ACTIVITY

COMPARED TO 2024/25

Coastal fatalities vary by activity and over time. Since 2015, boating/PWC has recorded the most unintentional fatalities (22%, n=134), followed by falls (12%, n=69) and non-aquatic transport (11%, n=66).

Figure 62

2015-25: FATALITY DISTANCE FROM A SURF LIFE SAVING SERVICE

Three in four coastal fatalities (77%, n=441) occurred greater than 1km from a Surf Life Saving service.

Figure 63

2015-25: COASTAL FATALITY BY LOCATION

Beaches are the leading fatality location (n=276), followed by offshore (n=116), then rock/cliff locations (n=82).

Figure 64

2015-25: REMOTENESS CLASSIFICATION OF FATALITY LOCATIONS

One in two unintentional fatalities occurred in regional/remote areas (57%, n=325), followed by major cities (34%, n=196). The remoteness classification of an incident location was coded to the Australian Statistical Geographical Standard of Remoteness Areas.

Figure 65

2015-25: RESIDENCE DISTANCE TO FATALITY LOCATION

Most decedents lived locally to the fatality location (n=172), followed by intrastate visitors (n=129), then nearby resident (n=113).

SOUTH AFRICA

COUNTRIES

Figure 66

2015-25: VISITOR CATEGORY OF DECEDENT

Most decedents were Australian residents (n=362), followed by short term visitors (n=45). Visitor status was unknown for 27% of cases (n=157).

Figure 67

2015-25: BIRTH CONTINENT OF DECEDENT

Birth continent is known for 75% of coastal fatalities (n=571), of these 49% were Australian-born (n=279), 13% were born in Europe (n=76), and 6% were born in Asia (n=35).

68

2015-25: FATALITY BY TIME

Most unintentional fatalities occurred in the afternoon (38%, n=215), followed by the morning (33%, n=189). The highest density have occurred between 10am and 5pm (48%, n=276; shaded area). Incident time was unknown for 11% of cases (n=60), which were excluded from analyses.

36% OCCURRED ON THE WEEKEND 37% OCCURRED IN SUMMER

69

2015-25: FATALITY BY MONTH & DAY

Most coastal fatalities occurred during summer (37%, n=214; Dec-Feb), followed by spring (25%, n=140; Sep-Nov). By month, January has recorded the highest number (15%, n=88), then December (12%, n=71). A disproportionate number of coastal fatalities occurred on weekend days (36%; n=206), with fatality risk 1.4 times greater on the weekend.

Figure

Figure

COASTAL FATALITY LOCATIONS

2015-25: TEN-YEAR ANALYSIS

19 122

39 50

199

22

COASTAL DROWNING

2004-25: 21-YEAR ANALYSES OF DROWNING

Figure 70

2004-25: PROGRESS AREAS

Rates allow for comparisons relative to the number of people in the popluation. Comparing three-year average rates/100,000 from 2004-07 to 2023-25 we have seen notable decreases in drowning rates for 18-34 year olds, especially with rip-related drowning. Similar decreases have been observed in rock fishing, boating and offshore drowning rates.

DROWNING RATES (PER 100,000 POPULATION)

Figure 71

2004-25: PRIORITY FOCUS AREAS

While progress has certainly been observed in some groups, there are some emerging key areas requiring stronger drowning prevention efforts. Reducing coastal drowning related to falls, older adults (55+ years) and at beaches are crucial to see meaningful decreases.

DROWNING RATES (PER 100,000 POPULATION)

2004-25: DROWNING NUMBERS VS. DROWNING RATES

This feature presents an overview of changes in coastal drowning since 2004/05. Using drowning number and rates, the below information highlights areas of progress but also those that require more attention. Coastal drowning, rip-related drowning, and drowning at rock platform and in regional/remote locations have seen an increase in numbers, but no change when we consider these changes in relation to the population. Drowning deaths involving boating, offshore waters, rock fishing and 18-34 year olds has seen reductions in numbers and rates/100,000 pop. Male drowning, and rip related drowning of two target populations (males and 18-34 year olds) have seen reduced drowning rates, despite increasing numbers. For more information about measuring drowning please refer to page 2-3.

Decreasing rate and numbers, keep going! Some progress, decreasing rate but numbers increasing. Some progress, but needs more work. Increasing rate and numbers needs attention!

BOATING OFFSHORE 18-34 YEAR OLDS

NEW SOUTH WALES

2024/25: VISITATION & CAPABILITY

In the last twelve months, 5.4 million New South Wales residents (16 years and above) visited the coast on average 3.7 times each month. This equates to approximately 20 million individual visitations to the coast.

5.4M COASTAL VISITORS 3.7

3,494 RESCUES 1,087,710 PREVENTATIV E ACTIONS

CAPABILITY $4,315,065,767 VALUE TO COMMUNITY 2.6 HOURS/VISIT

4.6M COASTAL ACTIVITY PARTICIPANTS

163 Searches 236 Shark alarms 557 Lost

COASTAL DROWNING

2024/25: YEAR IN REVIEW

New South Wales recorded 52 drowning deaths in coastal waters, comprising 42% of NSW’s total drowning burden (n=129). This is a 15% decrease from last year (n=61), and 13% above the ten-year average (n=46).

Males were overrepresented, accounting for 88% of drowning deaths. High-risk age groups include 50-59 (25%) and 15-24 year olds (17%), with decedents aged 55 years and above comprising 44% of New South Wales coastal drowning deaths.

Swimming/wading, rock fishing, and falls recorded 40%, 19% and 12% of coastal drowning deaths respectively. Most coastal drowning deaths occurred at beaches (48%), with a further 37% in rock/cliff locations.

0.63/100,000POP. DROWNING RATE

NB: Arrow indicates change from 10-year average

Figure 72

Regional and remote areas, which are harder to access and often have limited resources, recorded 44% of coastal drowning deaths, and 63% occurred more than 1km from a Surf Life Saving service. All coastal drowning deaths occurred at unpatrolled locations, outside of patrol times, or away from the red and yellow patrol flags. 52 COASTAL DROWNING DEATHS

2024/25: COASTAL DROWNING DEATHS

NSW recorded 52 coastal drowning deaths (drowning rate of 0.63/100,000 pop.), above the 10-year average (n=46).

ROCK/CLIFF

REGIONAL/REMOTE 37%

44%

NEW SOUTH WALES

2015-25: TEN-YEAR COASTAL DROWNING TRENDS

Figure 73

2015-25: COASTAL DROWNING DEATH TRENDS

Annual NSW coastal drowning deaths and rates are illustrated above. Coastal drowning deaths and rates in 2024/25 (n=52; rate:0.61/100,000) were above the 10-year average.

2015-25: KEY DEMOGRAPHICS

Figure 74

2015-25: DROWNING DEATHS BY ACTIVITY

Drowning prevalence varies. Since 2015, swimming and wading has recorded the most coastal drowning deaths (35%, n=165) in NSW, followed by rock fishing (17%, n=82), then boating/PWC (11%, n=53).

CAUSAL FACTORS

2015-25: COASTAL DROWNING DEATH NUMBERS & RATES BY BRANCH

(n=39, AVERAGE RATE = 1.87/100,000) FAR NORTH COAST

(n=46, AVERAGE RATE = 2.95/100,000) NORTH COAST

(n=25, AVERAGE RATE = 2.17/100,000) MID NORTH COAST

(n=18, AVERAGE RATE = 1.89/100,000) LOWER NORTH COAST

(n=36, AVERAGE RATE = 0.80/100,000) HUNTER

(n=34, AVERAGE RATE = 0.99/100,000) CENTRAL COAST

(n=38, AVERAGE RATE = 1.42/100,000) NORTHERN BEACHES

(n=101, AVERAGE RATE = 1.12/100,000) SYDNEY

(n=32, AVERAGE RATE = 1.49/100,000) ILLAWARRA

(n=50, AVERAGE RATE = 2.46/100,000) SOUTH COAST

(n=34, AVERAGE RATE = 4.55/100,000) FAR SOUTH COAST

Figure 75 2015-25: BIRTH CONTINENT OF DECEDENT

Almost one in two decedents were born overseas (46%).

BEACH TO BUSH

SLSNSW’s flagship educational program, Beach to Bush, saw a host of volunteer lifesavers heading inland to promote surf safety to primary school students across regional and rural NSW for a 31st year in 2024.

More than 11,000 students were engaged face-to-face and nearly 100 schools were visited over three huge weeks in November.

A major milestone was also achieved this time around, with volunteer lifesavers having now educated more than 300,000 students since the program’s inception in 1994 - a testament to the organisation’s commitment to educating diverse communities across NSW.

For many, the Beach to Bush program is their first interaction with the iconic red and yellow surf lifesavers, with children from regional and remote areas often at higher risk of drowning than those from coastal locations because they are less familiar with the beach and unaware of potential surf dangers.

Students attending the program learn about the role of surf lifesavers, why they should always swim between the red and yellow flags, how to spot a rip current, what to do if they get into trouble at the beach and the different types of marine life along the coast. Surf lifesavers also talk about the hazards of inland waterways.

Feedback received from students and educators alike were extremely favourable, with many impressed by the highly interactive sessions and the knowledge of the volunteers, with the practical sessions proving fun, engaging and, above all, educational.

B2B SCHOOLS

Inland waterways such as Lake Parramatta and Penrith Beach have become increasingly popular destinations for families, swimmers, and water sports enthusiasts. These locations offer a more controlled and accessible alternative to coastal beaches, attracting a diverse range of visitors looking to cool off, exercise, or simply enjoy nature.

However, while these environments may seem safer than coastal locations, they come with their own unique risks. Drowning and water-related incidents continue to occur in lakes and rivers due to factors such as hidden hazards, unpredictable water conditions, limited skillsets and limited public awareness of the dangers. This is where professional lifeguard services play a crucial role in ensuring visitor safety.

This season at both Lake Parramatta and Penrith Beach, the Australian Lifeguard Service NSW provided a flagged service which included many of the same operational offerings as coastal services, including active surveillance, responding to emergencies, and educating the public on water safety. The ALS’ presence not only reduced the risk of drowning, but also offered peace of mind to families and recreational users, allowing them to enjoy the water with confidence.

While ocean lifeguarding is the bread and butter of the ALS, inland waterway lifeguarding presents a distinct set of new challenges that require specialised attention, training and equipment. Unlike coastal beaches, where waves and rip currents are primary hazards, inland water locations come with risks that are often less visible but just as dangerous.

WESTERN SYDNEY LIFEGUARDS

PATROLLING INLAND WATERWAYS

Some key challenges that the ALS team has had to overcome include:

• Submerged objects & uneven depths

• Water quality & visibility issues

• Temperature changes & cold shock

• Limited escape options

• High visitor numbers & unsupervised areas

• Lack of visitor swimming ability and aquatic awareness

To address these challenges, lifeguards at these locations undergo specialised inductions and training that include inland water rescue techniques, first aid response for drowning and injuries, and public education strategies to raise awareness of hidden risks at inland waterways.

As the popularity of these locations continues to grow, so too does the responsibility to maintain high safety standards. Working alongside land managers, investment in lifeguard training, safety infrastructure, and technological innovations will be crucial in keeping visitors safe while they enjoy these beautiful aquatic locations.

Lake Parramatta Penrith Beach

74,002

VISITORS

59,336

104

67

RESCUES

79 FIRST AID TREATMENTS

8,720

8 PREVENTATIVE ACTIONS

6,322

In the last twelve months, 3.4 million Queenslanders (16 years and above) visited the coast on average 3.7 times each month (NCSS2025). This equates to approximately 150 million individual visitations to the coast.

$$$$$ QUEENSLAND

2024/25: VISITATION & CAPABILITY 2,355 RESCUES 617,666 PREVENTATIV E ACTIONS

3.4M

3.7

2.5

2.8M

$2,561,715,805 VALUE TO COMMUNITY

83 Searches 92 Shark alarms

74 Lost children 35,142 FIRS T AID TREATMENTS

19,375 Marine stings

14,649 Cuts/Abrasions

9

COASTAL DROWNING

2024/25: YEAR IN REVIEW

Queensland recorded 31 drowning deaths in coastal waters, comprising 34% of QLD’s total drowning burden (n=90). This is a 35% increase from last year (n=23), and 15% above the tenyear average (n=27).

Males were overrepresented, accounting for 87% of drowning deaths. High-risk age groups include 60-69 (29%) and 40-49 (26%) year olds, with decedents aged 55 years and above comprising 65% of Queensland coastal drowning deaths. Swimming/wading, snorkelling, and equally boating & attempting a rescue accounted for 39%, 19% and 6% of coastal drowning deaths, respectively. Most coastal drowning deaths occurred at beaches (68%), with a further 10% in offshore waters.

Regional and remote areas, which are harder to access and often have limited resources, recorded 55% of coastal drowning deaths, and 71% occurred more than 1km from a Surf Life Saving service. All coastal drowning deaths occurred at unpatrolled locations, outside of patrol times, or away from the red and yellow patrol flags.

0.55/100,000POP. DROWNING RATE COASTAL DROWNING DEATHS

NB: Arrow indicates change from 10-year average

Figure 76

2024/25: COASTAL DROWNING DEATHS

31 coastal drowning deaths were recorded (drowning rate of 0.55/100,000 pop.), above the 10-year average.

YEAR OLDS

MEDICAL INJURY

QUEENSLAND

2015-25: TEN-YEAR COASTAL DROWNING TRENDS

77

2015-25: COASTAL DROWNING DEATHS

Annual QLD coastal drowning deaths and drowning rates are illustrated above. Coastal drowning deaths and rates recorded in 2024/25 (n=31; rate:0.55/100,000) were above the 10-year average.

2015-25: KEY DEMOGRAPHICS

Figure 78

2015-25: DROWNING DEATHS BY ACTIVITY

Drowning prevalence varies by activity and over time. Since 2015, swimming and wading has recorded the most coastal drowning deaths (32%, n=90), followed by boating/PWC (25%, n=71), then snorkelling (16%, n=45).

CAUSAL FACTORS

Figure

2015-25: COASTAL DROWNING DEATH NUMBERS & RATES BY REGION

(n=5, AVERAGE RATE = 8.35/100,000 POP.) FAR NORTH QUEENSLAND

NORTH QUEENSLAND (n=27, AVERAGE RATE = 1.28/100,000 POP.)

NORTH BARRIER (n=23, AVERAGE RATE = 0.50/100,000 POP.)

WIDE BAY CAPRICORN (n=53, AVERAGE RATE = 1.70/100,000 POP.)