12 minute read

Annu Wileniuksen ainutlaatuinen Mongoliaprojekti nyt kirjana

teksti: tAinA RAjAnti kuvAt: sAARA HAcklin

TaM, visuaalinen taiteilija Annu Wilenius (1974-2020) oli syntynyt Helsingissä. Hän aloitti taiteellisen uransa valokuvauksen parissa, mutta kuratointi ja taiteellinen tutkimus muodostuivat myös tärkeiksi osiksi hänen toimintaansa. Hän oli kiinnostunut aiheista kuten ihmisen ja luonnon välinen suhde sekä asumiseen liittyvät kysymykset. Joulukuussa 2020 Annu Wilenius kuoli juuri ennen väitösprosessinsa viemistä päätökseen.

Advertisement

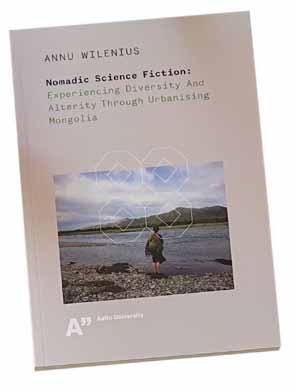

Aalto ARTS Books on julkaissut Annu Wileniuksen taiteen tohtorin väitöskirjaksi tarkoitetun käsikirjoituksen: Nomadic Science Fiction: Experiencing Diversity and Alterity through Urbanising Mongolia.

Kirja kertoo tarinan Annu Wileniuksen viisitoista vuotta jatkuneesta Mongoliaan kohdistuneesta taiteellisesta tutkimuksesta. Alunperin kohteena oli nimenomaan paimentolaisuuden (nomadismi) ja urbanisaation teemat Mongoliassa, mutta projektin myötä Wilenius ryhtyi taiteen keinoin tutkimaan myös kulttuurisia kohtaamisia ja toiseuden kokemusta. Monialainen tutkimusprojekti on tuonut yhteen lukuisia taiteilijoita ja tutkijoita sekä Mongoliasta että Länsimaista.

Myös kirjan julkistustilaisuus 15.3.2022 toi yhteen laajan yleisön. Tilaisuus pidettiin sekä livenä Aalto ARTSin tiloissa Otaniemessä, että online-tapahtumana johon osallistui väkeä niin Mongoliasta kuin Suomesta, Alankomaista, Saksasta, UKsta, ja Kanadasta. Väitöskirjan käsikirjoituksen julkaistavaksi toimittaneet professori Harri Laakso, kuraattori Saara Hacklin ja yliopistonlehtori emerita Taina Rajanti

Kirja on ilmaiseksi ladattavissa pdf muodossa: https://shop.aalto.fi/p/1650-nomadic-sciencefiction/ sekä Wileniuksen vastaväittäjäksi aiottu professori Pauline von Bonsdorff pitivät lyhyet puheenvuorot. Samoin Mongoliasta PhD ja taitelija Tsendpurev Tsegmid, joka on kääntänyt Wileniuksen Bare House -näyttelyn julkaisun tekstit mongoliksi; sekä Englannista tutkija ja arkkitehti Gregory Cowan. Oula Salokannel joka on vuosien mittaan tehnyt yhteistyössä Annu Wileniuksen kanssa useita taideteoksia ja näyttelyitä, oli valmistanut koosteen muutamasta Wileniuksen videotyöstä.

Halusimme muistaa Annun poikkeuksellista rohkeutta, vieraanvaraisuutta ja anteliaisuutta, hänen kykyään muutokseen ja seikkailuun. Ihmiset puhuivat siitä vaikutuksesta joka Annuun tutustumisella ja hänen kanssaan työskentelemisellä oli heidän elämässään. Suomessa emme ehkä edes täysin ymmärrä miten merkityksellinen ja laajakantoinen oli Annun vuosia kestänyt työ taitelijaresidenssien, taideleirien, näyttelyiden ja julkaisujen toteuttamiseksi, ja toteuttamiseksi niin että ne pohjautuivat aitoon vuorovaikutukseen ja taitelijoiden ja töiden vaihtoon Mongolian ja Länsimaiden välillä. Dr Tsendpurev Tsegmid kertoi että hänen mielestään kukaan yksittäinen ihminen ei ole saanut enempää aikaan nykytaiteen hyväksi Mongoliassa, kuin Annu. Hän oli itse juuri väitellyt tohtoriksi Englannissa ja harkitsi sinne jäämistä, mutta Annu ja Annun työ sai hänet uskomaan että nykytaiteella ja taitelijoilla ja kuraattoreilla voi olla tulevaisuus Mongoliassa. Tapahtuma nauhoitettiin ja on puheineen ja esitettyine videoineen nähtävissä tässä linkissä: https://aalto.cloud.panopto.eu/Panopto/Pages/ Viewer.aspx?id=7a335811-46c3-4c1f-b0e4ae59010414bc

Saara Hacklinin ja Taina Rajannin pitämät puheet on tässä julkaistuna erikseen, alkuperäisinä englanninkielisinä versioina.

Saara Hacklin: To Annu on the coming out of her doctorate

As one of the editors and Annu’s friend, I have also prepared to say something. However, thinking about this day has been very difficult and I have felt completely at loss when trying to find the right words. True, I have been reading the manuscript over the years, and last year we worked together with Harri and Taina on it - but we all know it is Annu’s vision that has finally got its physical form in Camilla Pentti’s hands and became one of Aalto Books publication.

But at the same time I would be lying, if I say that I have not been thinking about this day. To see Annu’s book ready, finalising 15 years of her work. And I am sure many of us have waited for this. I even imagined how she would defend her doctorate in a stylish black suit and possibly celebrate the occasion in something green. And I did think about what I would like to say to her. So therefore:

Dear Annu,

I started a journey with you 17 years ago. We had met some years earlier, but we did not really know each other until we stepped onto a train and shared the cabin for several days together with Tiina Mielonen and Rasmus Kjellberg. Those cabin days we were being professional, talking about tourism, Finnish explorers (J. G. Granö, G. J. Ramstedt), landscape, train travel and its history, how one experiences the distance differently, when travelling by land. But there were also evenings and nights, and a lot of talk about more personal things, like our hopes for the future.

Our shared travel to Mongolia was for all of us strange and new. In Ulaanbaatar we met people like Yondonjunain Dalkh-Ochir and Blue Sun people who opened us to new things, and we wanted to continue this shared adventure: we started planning how to return and to invite more people to join, so that we could understand everything better together.

The experience was groundbreaking for me. It was important to be equal with everyone else participating in the project. I was doing something I had not done before. The experience changed me: at first, I did not think of myself as a curator, but following years this started to change. The journey pushed me to a new direction. I also think it changed something in you, Annu: as we were visiting Mongolia the second time, you had already taken the role of organizer, with a vision of artist-curator that later on grew into the complex project Nomadic Science Fiction bears witness to.

But by taking the train in 2005, I became not only a colleague but a friend. This has happened to many of us who know you, as art and life often mixed together and working with you meant also finding a deeper connection, eating dinners and exchanging thoughts on whatever we were seeing or reading at time.

However, there was a point when my involvement in the so-called Mongolian project as a theorist and a curator came to an end: There was nothing dramatic in it, it was more about acknowledging that I had to follow my path and you had to make yours. But I never stopped wondering how the project evolved year by year into something more elaborate, more collaborative, more challenging in the context of artistic research. I admired how your involvement developed, how your visions and efforts were turned into concrete things, Bare House exhibition in Pori but also several new travels and exhibitions, taking different artists to Mongolia, but also to Pori and - Ganzug Sedbazar and Togmidshiirev Enkhbold - to Rotterdam. Not to mention the series of publications with the help of translators - especially Tsendpurev Tsegmid! I was so eager to see how the ever growing web of collaborations would all turn out.

I know our friendship had moments I felt I could not respond to you, I was too occupied with my own thesis, or work or raising kids. Luckily, you knew better: there was a time you simply said you were fed up with waiting and insisted that we meet for feedback over the manuscript. I am glad you did this - we met, discussed and the work and friendship continued.

In a speech you gave at the occasion of my doctorate ten years ago, you described an incident in Mongolia where I was sent to ask guests to stay away from the gallery as the opening had not started yet and the installing was unfinished. You remembered how I was not performing very well, saying to people that they should maybe not come. I was laughing at this “maybe not” person you exposed to everyone, the image of me kindly trying to say no, with a hesitation. I felt you had caught something. Indeed, you had perceptive eyes - wolf like and beautiful, I hear someone saying - and a strong vision that you followed.

For me, you have always been a YES person. Not the kind of yes person who agrees mildly to others’ vision, or a person who is simply overly positive, but a critical person who sees a possibility: be it a connection, a collaborator, an event, an adventure - and chooses to say yes to that. You were very brave and rarely hesitated when the direction was set.

*

Last months I have been reading South Korean philosopher based in Germany, Byung

Chul-Han. I would have loved to hear your view on his thoughts.

Byung Chul-Han writes about the loss of rituals in our era. Our society misses rituals. There is one ritual that I have been thinking about lately, namely the ritual of closure. Our society is driving us towards increased productivity and there is no time for closure, we are always busy running to the next project, next achievement.

Rituals are constituted by symbolic perception: by recognition. Byung Chul-Han reminds us of the origin of symbol, Greek Symbolon: it refers “to the sign of recognition between guest-friends (tessera hospitalis). One guestfried broke a clay tablet in two, kept one half for himself and gave the other half to another as a sign of guest-friendship. Thus a symbol serves the purpose of recognition.”

So the symbol is broken at a dinner to be a sign of mutual hospitality. The symbol reminds us of the recognition and hospitality that we once shared.

You loved a good story - and rituals. You would have loved to get a closure and step over the threshold of the doctorate. Now it has outlasted you, and we are left to look for a closure in the ritual of mourning. Today, we are here to remember the clay tablets that were broken over dinners and evenings. To recognise your hospitality, vigor and artistic vision.

Taina Rajanti: Doing things you don’t know - the journey and change.

(This is an edited version of the talk that was done without a manuscript./ Alkuperäinen puhe pidettiin ilman tekstiä, tämä teksti on toimitettu versio siitä.)

was teaching doctoral courses. But my memory of encountering Annu is that she invited me to do something. Our collaboration and friendship started so that she invited me to talk in a seminar on photography that she had organised in Reposaari, near Pori in the summer 2009.

And I said to Annu: ”But Annu, I am not a photographer and I don’t know anything about photography, I have not studied it in any academic context.”

And Annu smiled at me and said: “It doesn’t matter. And, it’s not true. You have been using photographs and you can say what you have to say about them.”

And then in 2014 Annu invited me to curate a contemporary art exhibition in Tampere with her.

And again I said: “But Annu, I’m not a curator, I don’t know anything about curating or exhibitions.”

And again she said: “It doesn’t matter. And it’s not true.”

And it didn’t go so that I wrote texts and Annu took care of the concrete hanging of works - we did it all together, checking the sites and the works and thinking how to place them.

I met Annu in Pori. At that time I was working as research manager, but I was also teaching - and so I must have met Annu when I

And this is the first thing that came to my mind when thinking about Annu. I come from social sciences, and Annu greatly appreciated my background and perspective, because she was always looking for people who had different perspectives on things that she was engaged with. She didn’t want to look only for people she agreed with completely or people who were doing the same things she was. I think even here (in this book-launch) we can find a surprising amount of really close friends from very different backgrounds and professions and ways of living. So, Annu invited me - but not as a social scientist confining myself to my role of social scientist and commenting on her artwork and curating, but to mess with her thinking, with her artwork, with her curating.

Like Harri just said, Annu was generous, and she offered you the possibility of learning new things, of changing, with her.

And I think it is very fundamental and part of the fundamentals of Annu’s thesis. It is not only an attitude, this ”I don’t know anything about this but I’m doing it anyway”. She discusses at length how she and Oula (Salokannel) built a raft and went sailing down Kokemäenjoki from Pori - not knowing anything about rafts or how to build them or how to row or punt with a raft. And I know punting the raft wasn’t all smooth going, Annu and Oula waded waist-deep in the river when the raft got stuck, though it did make for a unique experience. But the main point is that not caring to do only something you have learned to do and having a diploma telling you have a legitimation to do, you can learn new things, and change yourself - and change how these things are done. And Annu took this notion of “not caring if you know how to do something” further. She introduced me to architects and urbanists who think that we should not only listen to professionals who plan and build our living, our environment and our dwellings, but that also the people who officially “don’t know” but who are doing the dwelling have also valuable knowledge of how it can be done. This is a very fundamental point that comes out in Annu’s book and thinking, and her art and her curating. Her whole work on the ger district of Ulaan Baatar, her video of “The House that I Grew up in” with images from the gers and a voice-over of Annu telling about the area where she lived as a child, illuminating the surprising similarities between the two - well, all of Annu’s adventurous projects in Mongolia really, are based on this idea and thinking and way of doing things.

I would also have wanted to argue with Annu about Ursula K. LeGuin. Damn that people leave us too soon… I feel responsible for there being the topic of “science fiction” in the thesis, as I was the one who introduced Annu to Ursula K. Le Guin. Le Guin is a US author of fantasy and science fiction, but she came from a family of anthropologists; she has been invited by people like Donna Haraway, to talk about methodology for anthropologists. Ursula Le Guin is not just writing fiction, I think she is writing (about) reality. So the way that Annu approached her project, Mongolian urbanisation and topics of dwelling and journeys immediately made me think of Ursula K. Le Guin, and I recommended reading Le Guin to her. Which Annu did, and was obviously very taken by Le Guin, because Le Guin figures high in the thesis. The thing I would have liked to argue with Annu is that she interprets two fundamental books, “The Left hand of Darkness” and “The City of Illusions” as “Bildungsroman”. Thus stories which are based on the life and growth and destiny of one person. I disagree. I think Annu felt this closeness to a Bildungsroman because she was aware that her whole project and research and especially her thesis was all so fundamentally based on herself. So she felt she had a need to find some ways of legitimising this very personal approach in an academic work. But I don’t think Le Guin means to write Bildungsroman.

I recommended Le Guin especially because her work is set in a universe of galactic ecumenia where envoys of the ecumenia are always looking for new cultures, new worlds, and trying to enlist them - but not to conquer them. They want only voluntary new members. So at the beginning they send to a newly found culture only one person. Just one person to tell about the ecumenia, talk about advantages of joining it and collaborating with it. At the end of Left Hand of Darkness the envoy of that story is thinking that this is done not so much to have the ecumenia not appear as a threat to the new culture, but because as the envoy goes there alone, the envoy themselves will be changed. You cannot rely on your friends and what you know through your own culture. You will have to accept that you are a stranger, and that you’re among strangers - but you will have to discover what it is you have in common. You will have to start to understand the new culture and be changed by it. And I think this is the basic idea of Annu’s book and the basic idea of Annu’s work and the project, the things she was doing.

And that with the idea of all this set in the context of a Bildungsroman Annu was being too harsh on herself. A Bildungsroman always has a closure,normally as a story of a success. And when Annu was writing the thesis she felt that the perspectives of her life, that anything can happen and she can do whatever she sets her mind to do were closing in - that she could not see the world open and do whatever anymore, and that this is the closure and end of her story. But Annu, that is not true! The basic thing in any Ursula K LeGuin book is the journey, not a result and an ending. The journey is about change.

Annu had a rare and remarkable talent for change - for changing herself, her friends, people she worked with - groups and collectives and communities she worked in. And this book - the story, the thesis - is also all about the journey, and I’m so glad of the book and the journey, and having been able to go with Annu on it and be changed by it.