African Americans have long defied white supremacy and celebrated Black culture in public spaces by Shannon M. Smith

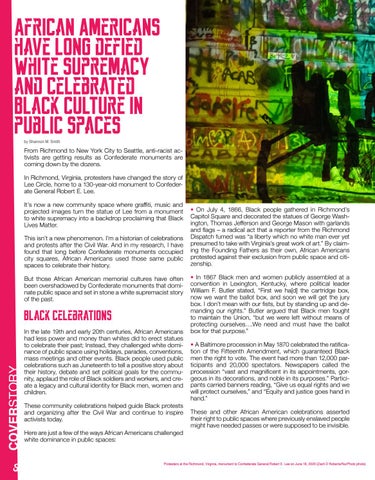

From Richmond to New York City to Seattle, anti-racist activists are getting results as Confederate monuments are coming down by the dozens. In Richmond, Virginia, protesters have changed the story of Lee Circle, home to a 130-year-old monument to Confederate General Robert E. Lee. It’s now a new community space where graffiti, music and projected images turn the statue of Lee from a monument to white supremacy into a backdrop proclaiming that Black Lives Matter. This isn’t a new phenomenon. I’m a historian of celebrations and protests after the Civil War. And in my research, I have found that long before Confederate monuments occupied city squares, African Americans used those same public spaces to celebrate their history. But those African American memorial cultures have often been overshadowed by Confederate monuments that dominate public space and set in stone a white supremacist story of the past.

COVERSTORY

Black celebrations

8

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, African Americans had less power and money than whites did to erect statues to celebrate their past; Instead, they challenged white dominance of public space using holidays, parades, conventions, mass meetings and other events. Black people used public celebrations such as Juneteenth to tell a positive story about their history, debate and set political goals for the community, applaud the role of Black soldiers and workers, and create a legacy and cultural identity for Black men, women and children. These community celebrations helped guide Black protests and organizing after the Civil War and continue to inspire activists today. Here are just a few of the ways African Americans challenged white dominance in public spaces:

• On July 4, 1866, Black people gathered in Richmond’s Capitol Square and decorated the statues of George Washington, Thomas Jefferson and George Mason with garlands and flags – a radical act that a reporter from the Richmond Dispatch fumed was “a liberty which no white man ever yet presumed to take with Virginia’s great work of art.” By claiming the Founding Fathers as their own, African Americans protested against their exclusion from public space and citizenship. • In 1867 Black men and women publicly assembled at a convention in Lexington, Kentucky, where political leader William F. Butler stated, “First we ha[d] the cartridge box, now we want the ballot box, and soon we will get the jury box. I don’t mean with our fists, but by standing up and demanding our rights.” Butler argued that Black men fought to maintain the Union, “but we were left without means of protecting ourselves….We need and must have the ballot box for that purpose.” • A Baltimore procession in May 1870 celebrated the ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment, which guaranteed Black men the right to vote. The event had more than 12,000 participants and 20,000 spectators. Newspapers called the procession “vast and magnificent in its appointments, gorgeous in its decorations, and noble in its purposes.” Participants carried banners reading, “Give us equal rights and we will protect ourselves,” and “Equity and justice goes hand in hand.” These and other African American celebrations asserted their right to public spaces where previously enslaved people might have needed passes or were supposed to be invisible.

Protesters at the Richmond, Virginia, monument to Confederate General Robert E. Lee on June 18, 2020 (Zach D Roberts/NurPhoto photo).