STRATEGIC VISION for Taiwan Security

Celestial Ambitions

US-China Space Race No Rehash of Cold War

Japan Steps Up in Indo-Pacific Region

Nguyen Vo Huyen Dung

China Cool to Suffering in Myanmar

Hon-min Yau

Trump’s Trade War With China

Shao-cheng Sun

Intelligence Community in South Africa

Bheki Mthiza Patrick Dlamini

Volume 8, Issue 42 w June, 2019 w ISSN 2227-3646

Tonio Savina

STRATEGIC VISION for Taiwan

Security

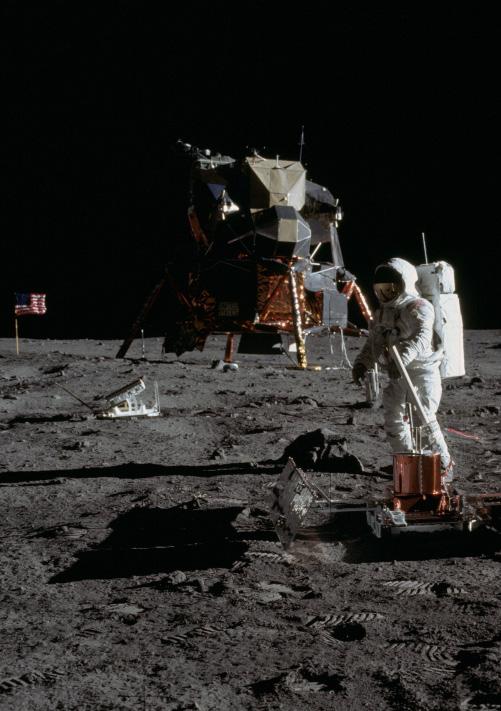

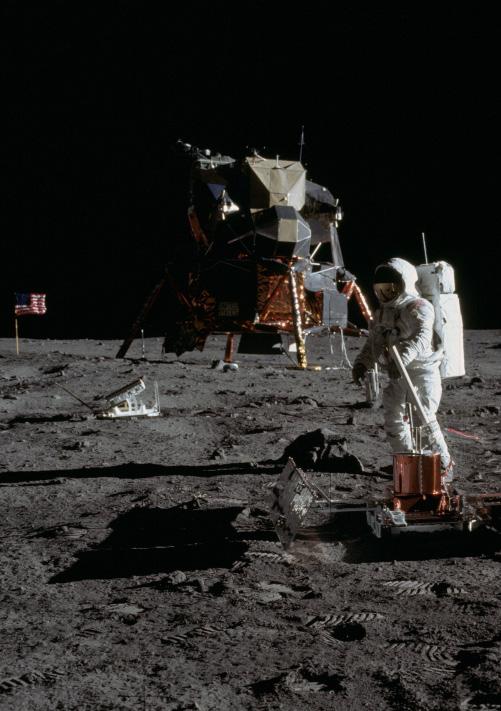

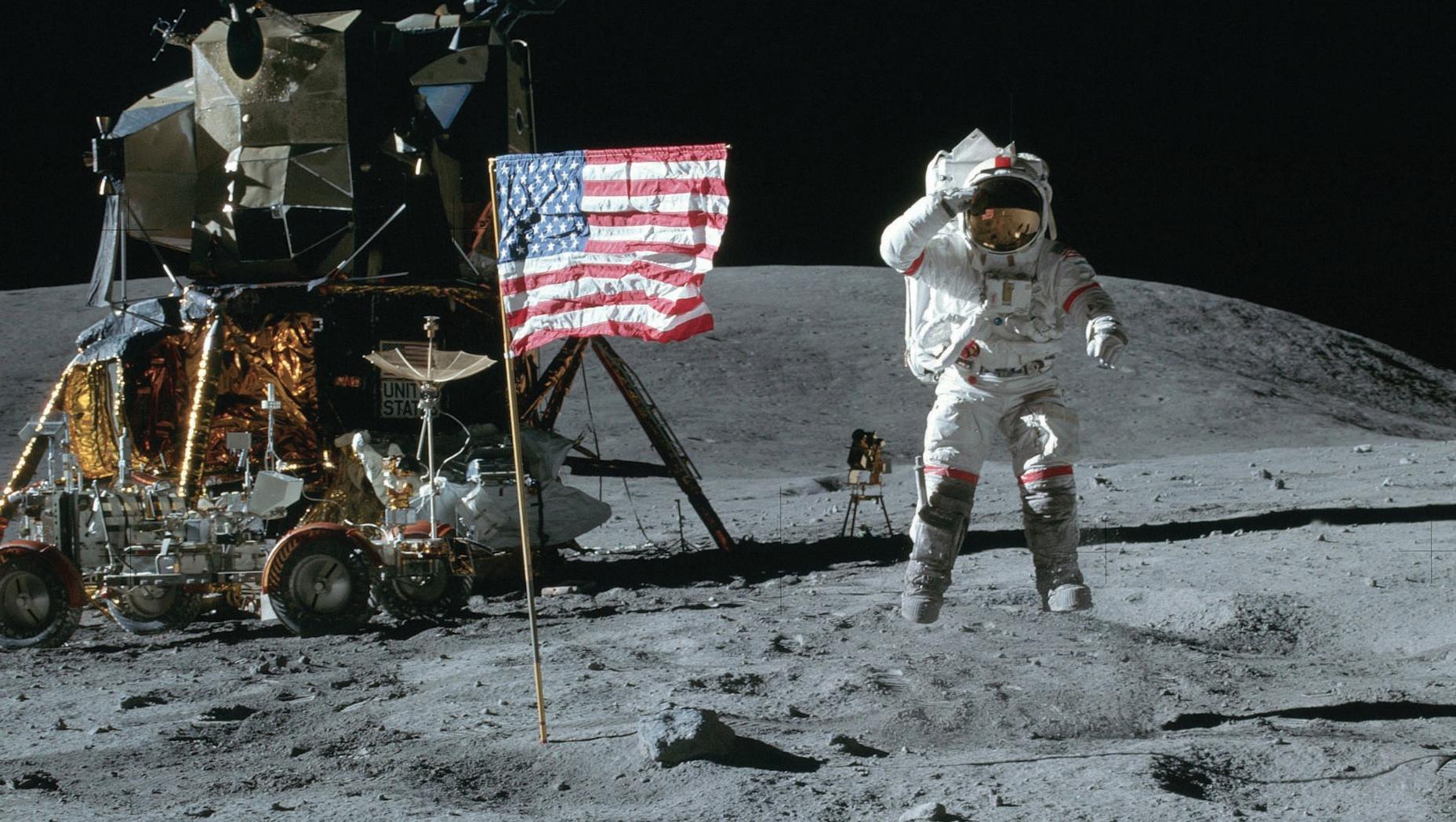

Submissions: Essays submitted for publication are not to exceed 2,000 words in length, and should conform to the following basic format for each 1200-1600 word essay: 1. Synopsis, 100-200 words; 2. Background description, 100-200 words; 3. Analysis, 800-1,000 words; 4. Policy Recommendations, 200-300 words. Book reviews should not exceed 1,200 words in length. Notes should be formatted as endnotes and should be kept to a minimum. Authors are encouraged to submit essays and reviews as attachments to emails; Microsoft Word documents are preferred. For questions of style and usage, writers should consult the Chicago Manual of Style. Authors of unsolicited manuscripts are encouraged to consult with the executive editor at xiongmu@gmail.com before formal submission via email. The views expressed in the articles are the personal views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of their affiliate institutions or of Strategic Vision. Manuscripts are subject to copyediting, both mechanical and substantive, as required and according to editorial guidelines. No major alterations may be made by an author once the type has been set. Arrangements for reprints should be made with the editor. Cover photograph of Astronaut Edwin E. Aldrin Jr., lunar module pilot, deploying the Early Apollo Scientific Experiments Package during the Apollo 11 extravehicular activity on the Moon is courtesy of NASA.

Volume 8, Issue 42 w June, 2019 Contents Japan steps up in Indo-Pacific region ............................................4 Space Race with China unlike that of Cold War .......................... 12 Chinese national interests and the suffering in Myanmar .......... 19 Trump’s trade war with China .....................................................26 Problems with South Africa’s intelligence community ............... 32 Nguyen Vo Huyen Dung Tonio Savina Hon-min Yau Shao-cheng Sun

Bheki Mthiza Patrick Dlamini

Editor

Fu-Kuo Liu

Executive Editor

Aaron Jensen

Associate

Dean

Editor

Karalekas

Editorial Board

Guang-chang Bian, NDU

Chung-young Chang, Fo-kuan U

Richard Hu, NCCU

Ming Lee, NCCU

Raviprasad Narayanan, JNU

Chris Roberts, U of Canberra

Lipin Tien, NDU

Hon-Min Yau, NDU

Rui-lin Yu, NDU

STRATEGIC VISION For Taiwan Security (ISSN 2227-3646) Volume 8, Number 42, June, 2019, published under the auspices of the Center for Security Studies and National Defense University.

All editorial correspondence should be mailed to the editor at STRATEGIC VISION, Center for Security Studies in Taiwan. No. 64, Wan Shou Road, Taipei City 11666, Taiwan, ROC.

The editors are responsible for the selection and acceptance of articles; responsibility for opinions expressed and accuracy of facts in articles published rests solely with individual authors. The editors are not responsible for unsolicited manuscripts; unaccepted manuscripts will be returned if accompanied by a stamped, self-addressed return envelope.

Photographs used in this publication are used courtesy of the photographers, or through a creative commons license. All are attributed appropriately.

Any inquiries please contact the Executive Editor directly via email at: dkarale.kas@gmail.com. Or by telephone at: +886 (02) 8237-7228

Online issues and archives can be viewed at our website: www.csstw.org

© Copyright 2019 by the Center for Security Studies.

Articles in this periodical do not necessarily represent the views of either the CSS, NDU, or the editors

From The Editor

The editors and staff at Strategic Vision would like to express our thanks to our loyal readers, and we hope we can continue to provide the most timely and reliable analysis and information on topics affecting cross-strait and regional security. To that end, we are pleased to offer this, our latest issue.

We open this issue with an examination of Japan’s recent moves, under Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, to take on a more proactive role in the Indo-Pacific region, by Nguyen Vo Huyen Dung, who is head of the International Relations Division at the University of Danang in Vietnam. Following this, Tonio Savina, a doctoral student at the Italian Institute of Oriental Studies at Rome’s Sapienza University, examines the competition between China and America in the realm of space, and how this differs substantially from the space race with the Soviets.

Next, regular contributor Dr. Hon-min Yau, an assistant professor at the ROC National Defense University, looks at the reasons behind Beijing’s use of its UN veto power to prolong the ongoing humanitarian crisis afflicting Myanmar’s Rohingya people.

This is followed by an article by Dr. Shao-cheng Sun, an assistant professor at The Citadel, who looks at the ins and outs of the ongoing trade war between the Trump administration and China. Finally, Bheki Mthiza Patrick Dlamini, a Master’s student at National Defense University’s Graduate Institute of Strategic Studies, explains the problems that South Africa is experiencing with an intelligence apparatus that has insufficient oversight.

We hope you enjoy this issue, and we look forward to following the topics that affect our lives in the Asia Pacific as we move in to the autumn season.

Dr. Fu-Kuo Liu Editor Strategic Vision

Strategic Vision vol. 8, no. 42 (June, 2019)

Rising Sun

Japan

assumes

expanded role in Indo-Pacific region under Shinzo Abe

Nguyen Vo Huyen Dung

In recent years, international relations in the Asia-Pacific have become extremely complicated due to the rise of the People’s Republic of China (PRC). The revival of Quad 2, India’s Act East Policy, the promotion of Japan’s soft power, and strategic adjustments by US President Donald Trump, with its new focus on the “Indo-Pacific” (as opposed to the formulation “Asia-Pacific,” espoused by the previous administration) are just some of the major developments. The US Free and Open Indo-Pacific (FOIP) Strategy is contributing significantly to shaping and dominating the structure as well as the power balance in the region.

As a member of the US-Japan alliance, Japan is actively confirming its role in the FOIP strategy. With certain successes of the Abenomics policy, the Cool Japan policy, and the decision to reinterpret Article 9 of the 1947 Constitution, Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s administration is striving to take advantage of opportunities as well as to ease certain challenges when facing global and regional complex movements.

The term “Indo-Pacific” was first introduced by Indian strategist Gurpreet S. Khurana in 2007 and then later was used in turn by Abe in 2007 and former US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton in 2011, and was

4 b

Nguyen Vo Huyen Dung is a lecturer and head of the International Relations Division at the Faculty of International Studies at the University of Foreign Language Studies, University of Danang, Vietnam.

photo: Whitney C. Houston

A Japanese landing craft, air cushion approaches Langham Beach, Queensland Australia, July 16, during Exercise Talisman Saber 2019.

included in Australia’s Defense White Paper in 2013. However, it was only when Trump used the term in his opening speech at the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) Forum in Da Nang, Vietnam, as well as during his two-week Asia tour in November 2017, that this term was once again became officially noticed and widely used. In May 2018, just before the Shangri-La Forum, the United States announced the renaming of the Pacific Command to the Indo-Pacific Command, which added emphasis to America’s IndoPacific strategy.

Subjective and objective

Among the issues affecting the introduction of the FOIP strategy, there are two main factors—the subjective and the objective—that should be considered. The subjective factor is the role of the United States and its impact on the US-Japan alliance. The implementation of the FOIP strategy will not only ensure a stable, free, and democratic United States, but also maintain its position at the leading super-

power. Meanwhile, the objective factor is directly related to the rise of China, especially the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

It can be said that China’s belligerent moves and complicated regional changes have forced the US to strengthen and expand its alliance network instead of

focusing on bilateral alliances (US-Japan, US-Korea) as before to indirectly counter China’s ambitious policies and strategies. These are also the main and most important targets of the FOIP strategy of the Trump administration, with the three main pillars of economy, governance, and security.

Under Abe, Japan has a shared interest with the United States in upholding the FOIP strategy. In August 2007, in his speech to the Indian Parliament, Abe described the strategic link between the Indian

Japan’s Regional Aspirations b 5

photo: Jacob Moore

Warships of the US Navy and the Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force conduct training as part of Exercise Keen Sword.

“With the success of Abe’s last re-election, the FOIP strategy is expected to be further developedandexpanded.”

Ocean and the Pacific Ocean. This could be seen as the initial idea of Japan’s FOIP strategy and, through this, Abe affirmed that, “with this wide, open, broader Asia, it is incumbent upon us two democracies, Japan and India, to carry out the pursuit of freedom and prosperity in the region.”

Developed and expanded

Five years later, when Abe returned to the position of Japanese prime minister in 2012, he once again invoked this strategy when referring to the formation of a security diamond in the Asia-Pacific: the implication of the revival of Diamond Quadrilateral with Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (QSD). By November 2017, phrases like “Security Quadrilateral” and “Free and Open Indo-Pacific” were reiterated by Abe during President Trump’s visit to Japan just before the APEC High-Level week. With the success of Abe’s last re-election, the FOIP strategy is expected to be further developed and expanded by both countries during the implementing process.

With the launch of the FOIP strategy, the IndoPacific region promises to see significant changes. It will see a strong, free, and proactive economic development of nations, an increase in defense investment and cooperation between countries, as well as the return of the QSD. In addition, the re-

gion will witness escalating tensions from China’s BRI and the US FOIP strategy. This may indirectly produce an arms race, with China on one side, and the United States and its allies on the other. The Indo-Pacific region will therefore be significantly impacted, and it is also the time when major powers and alliances will demonstrate their role and influence in the region.

Japan has a chance to define its positive role in the economic context. According to the Asian

6 b STRATEGIC VISION

“Japan and other countries in the region share common risks andinterestsintheSouthChina Sea.”

photo: Kremlin.ru

President of Russia Vladimir Putin and President of the United States Donald Trump speak on the sidelines of the 2017 APEC Economic Leaders’ Meeting.

Development Bank, in 2017 the Asia-Pacific region accounted for 42.6 percent of global GDP, major economies in the region also have diversified their participation in production networks, contributing to one-third of global exports.

Potential growth

In addition to the indicators that show potential growth, complicated movements with hidden risks challenge regional peace and stability in the Asia-Pacific and the broader Indo-Pacific, have made it progressively more difficult to secure the regional security structure. In this context, with a positively recovering and growing economy and considerable soft-power influence, Japan’s opportunities to identify and enhance its position in the region are huge.

The FOIP strategy and the increasing role of large countries in the Indo-Pacific region will create favorable conditions for Japan in particular, and the Japan-US alliance in general, to become more active in adjusting security policies and cooperation strategies—especially in the field of security and defense—to expand the scope and scale of their impact in the region. This will have an effect of the distribution of regional power and directly involve those large countries in the process of shaping the Indo-Pacific security structure.

Japan and other countries in the region share common risks and interests in the South China Sea. Japan is the world’s third-largest economy, and it will have certain opportunities and advantages in the power race compared to other countries in the region, especially given the growth of the Japan Coast

Japan’s Regional Aspirations b 7

photo: Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force Warships from the United States, India, Japan, and the Philippines transit the international waters of the South China Sea on 5 May, 2019.

Japanese PM Shinzo Abe

Guard. Japan’s policy towards the South China Sea is clear and consistent in terms of international cooperation contributing to improving law enforcement capacity and maintaining peace and self-assurance at sea.

Facing challenges

Countries along the South China Sea such as Vietnam, the Philippines, Malaysia and Indonesia are the main partners supporting the construction of a maritime legal capacity to help these countries strengthen their law enforcement capabilities at sea. This will obviously strengthen Japan’s ties with these countries in particular and Southeast Asia in general, which will greatly promote Japan’s role as a regional and global power. It can be said that the structure of the Indo-Pacific region requires consensus among major countries, and Japan is taking an important role in shaping the region.

Japan’s role in the FOIP strategy also faces a number of challenges. Japan’s first challenge is to adjust Article 9 of its pacifist Constitution. Although Abe has always advocated a reinterpretation of the Japanese Constitution to fit the current situation, this ambition will be a significant challenge for Abe’s government, and may result in indirect difficulty in the implementation of Japan’s defense and security activities. However, even when Japan succeeds in adjusting Article 9, which will formally recognize the role of the Japan Self Defense Forces as a true military force, this move will inevitably encounter opposition from South Korea and China.

Japan’s defense budget has increased continuously for the past five years under Abe, and is currently the eighth-largest defense budget in the world. Japan has begun to develop its own defense industry and will likely become a stronger militarily power. This could push Northeast Asia into an arms race as countries increase spending on defense. If this oc-

8

b STRATEGIC VISION

Personnel from the US Air Force and the Japan Air Self Defense Force discuss operations during an exercise at Iruma Air Base, Japan.

photo: Machiko Arita

curs, the possibility for other countries in the region to pursue the development of nuclear weapons may well increase.

Writing the rules

The second challenge is the rapid rise of China and its growing economic, cultural, and especially military influence. The development and modernization of the Chinese military along with its national security strategies in recent years have forced Japan and other countries to make strategic adjustments. In a 2015 interview with The Wall Street Journal, former US President Barack Obama opined, “If we don’t write the rules, China will write the rules out in that region.”

Clearly, China’s geopolitical and strategic rise is the biggest challenge for Japan in the region. In addition, North Korea’s nuclear and missile programs, as well as increased Russian activities in the Far East, will also be potential challenges affecting the balance of

power in the Indo- Pacific region.

The third challenge lies in the long-term alliance with the United States, especially as the Trump administration uses slogans such as America First, and once warned Japan about the instability in trade relations between the two countries. Japan is truly the cornerstone of the FOIP strategy, and the US-Japan

alliance plays a very important role in Japan’s security strategies in the region. Therefore, improving trade relations to ensure the healthy maintenance of this alliance will also be one of the challenges that Japan must face and overcome in the future.

The final challenge is that as Japan increasingly asserts itself and adopts a more important role, it will unintentionally reduce its dependence on the

Japan’s Regional Aspirations b 9

“Japan’syears-longefforttoincrease both its hard power and soft power hasprovidedthecountrywithagreat opportunity.”

photo: Tanner Lambert

A service member with the Japan Self Defense Force on a simulated reconnaissance mission of exercise Talisman Sabre 19 in Australia on 21 July, 2019.

American security umbrella, the US-Japan alliance will be affected to one degree or another. The FOIP strategy will therefore also be affected and the challenge now for Japan is how to improve its position in the region and at the same time not affect the implementation of the FOIP strategy.

Japan’s years-long effort to increase both its hard power and soft power, particularly under Abe, has provided the country with a great opportunity to assert its role and position as a comprehensive power in the region. However, Japan will also certainly face challenges, including the existing limitations of the decision to reinterpret Article 9. New opportunities and new challenges will be set for Japan, which means that greater effort will be required to timely and proactively address new regional movements and trends. In a speech in Brussels in February 2016, Japanese

Ambassador to the European Union Keiichi Katakami said that Japan’s military forces plan to play a more active role in self-defense, peacekeeping and conflictprevention. Clearly, Japan is determined and ready to change its image and position in the region and in the world. In other words, Japan will no longer just be a passive international actor, standing outside the political and security games while concentrating solely on trade and development assistance. In contrast, Japan will be more actively involved, with a greater role and influence in the process of forming a regional structure, particularly through the FOIP strategy. Therefore, the development of military forces and investment in defense will be one of the top priorities of Abe’s administration in addition to economic development, stability, and social security assurance.

ASEAN ties

Japan will also strengthen relations with Southeast Asian countries, as the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) plays an important role in regional

10 b STRATEGIC VISION

photo: Lisa Ferdinando

US Defense Secretary James Mattis meets with his counterparts from Japan, Takeshi Iwaya (left), and South Korea, Jeong Kyeong-doo (right).

“Japan’s military forces plan to play a moreactiveroleinself-defense,peacekeepingandconflict-prevention”

affairs. Last June, the 34th ASEAN Summit held in Bangkok, Thailand, adopted the ASEAN Outlook on the Indo-Pacific, affirming ASEAN’s immutable principles and setting orientations for ASEAN’s conduct in its relations with other countries.

This not only reflects ASEAN’s ability to cooperate and unite in responding to external challenges and changes, but also delivers ASEAN’s message to the world about its support for a peaceful, stable, and prosperous Indo-Pacific region. Moreover, ASEAN Outlook will also orient its behavior with the regional cooperation strategies and initiatives of major countries, which certainly include the FOIP. Therefore, this will create a springboard for ASEAN to further promote its leading role in Indo-Pacific region.

At the same time, Japan will also advocate building multilateral relations and reinforcing the foundation for security cooperation—an important framework for maintaining peace and stability in the Indo-Pacific region.

In short, the FOIP is expected to provide a stra-

tegic framework for its member countries, which currently include the United States, Japan, India and Australia, to promote cooperation. Japan faces opportunities and challenges that will change its regional and global role through this regional connectivity agenda.

Economic strength can promote Japan’s political position, but only military strength can allow Tokyo to truly become a political power. This is, of course, not welcomed by many countries, especially China. On the other hand, although Japan does seek to use the FOIP to counter China’s growing influence via the BRI, the more important goal is to build a peaceful, free region marked by democracy, stability, and prosperity. Therefore, the FOIP strategy is not expected to directly prevent or oppose Chinese investment in infrastructure through the BRI, but it will keep up the pressure and force China to respect international laws and rules during the investment process. Obviously, that pressure will only work if it comes from countries that receive this investment. n

Japan’s Regional Aspirations b 11

photo: Whitney C. Houston

A Japanese Defense Force soldier mans his turret on Kings Beach in Bowen, Queensland, during Exercise Talisman Saber 2019.

Strategic Vision vol. 8, no. 42 (June, 2019)

Celestial Ambitions

New space race between China and America breaks the Cold War mold

Tonio Savina

Tonio Savina

On January 3rd 2019, China’s lunar probe dubbed the Chang’e 4 landed on the far side of the moon, deploying the rover Yutu 2 on the lunar surface. Only a few months later, on 13 May, US President Donald Trump announced the ambitious goal to send American astronauts back to the moon by 2024—four years earlier than the previous target of 2028.

This decision has triggered an intensive international debate, with experts raising concerns about a possible new space race between China and the United States. According to this view, both countries seem to follow a primacist strategy in pursuit of their

Astropolitik interests.

However, it is important to note that we are not in the 20th century competition between two Cold War rivals, and that the space race paradigm is no longer enough to understand the current national space programs. Interpreting space strategies requires us to take different variables into account, such as the emergence of new space nations, the growing role of non-state actors, and the role of economic and socio-political factors.

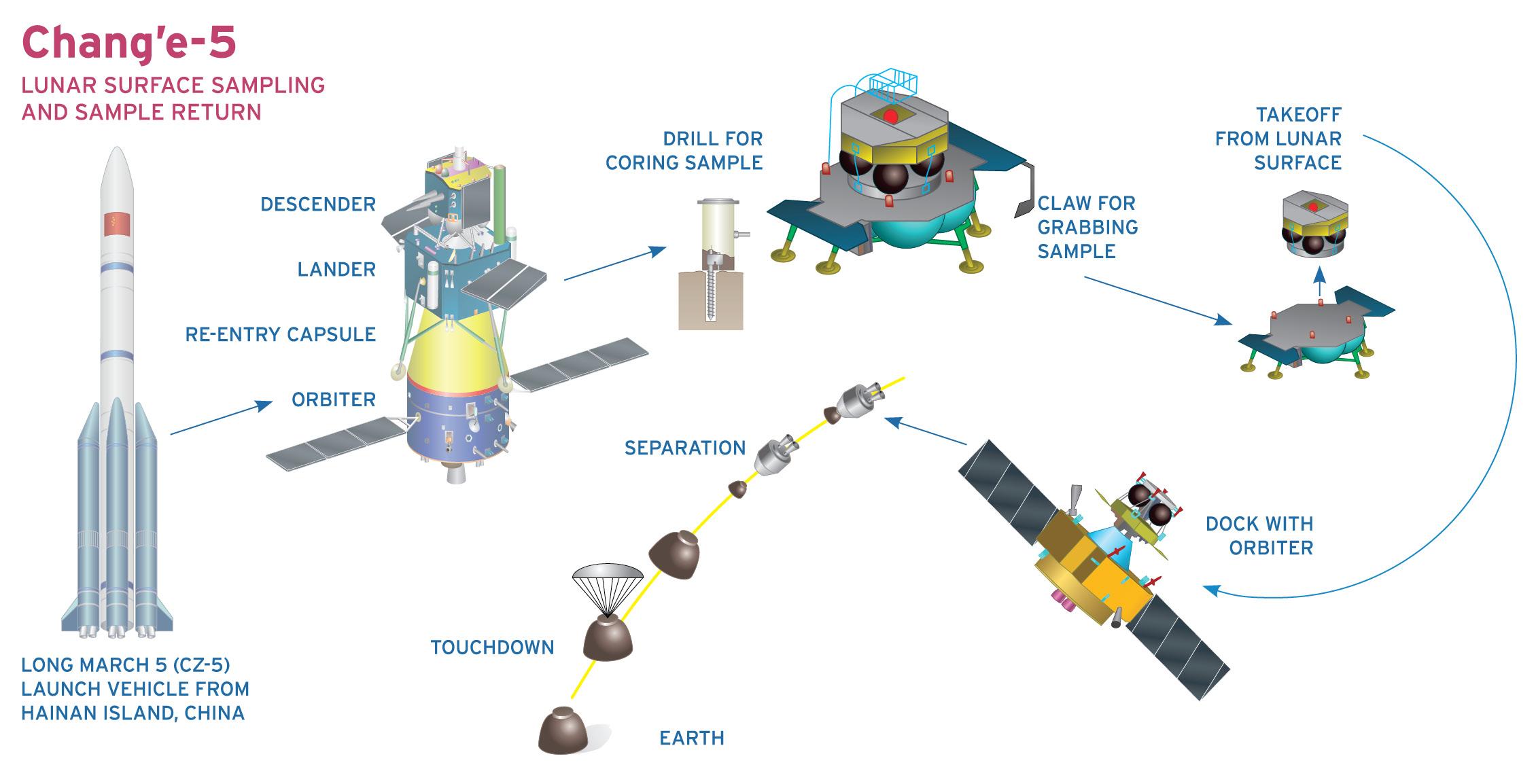

The Chang’e 4 moon mission was part of a larger Chinese lunar exploration program originally divided into three steps: the first one included the

Tonio Savina is a Ph.D. student from the Italian Institute of Oriental Studies at Sapienza University of Rome. He can be reached for comment at tonio.savina@uniroma1.it

12 b

photo: Jaymantri

The first space race ended with the first successful US mission to the moon in 1969. The new one was launched as China seeks a greater global presence.

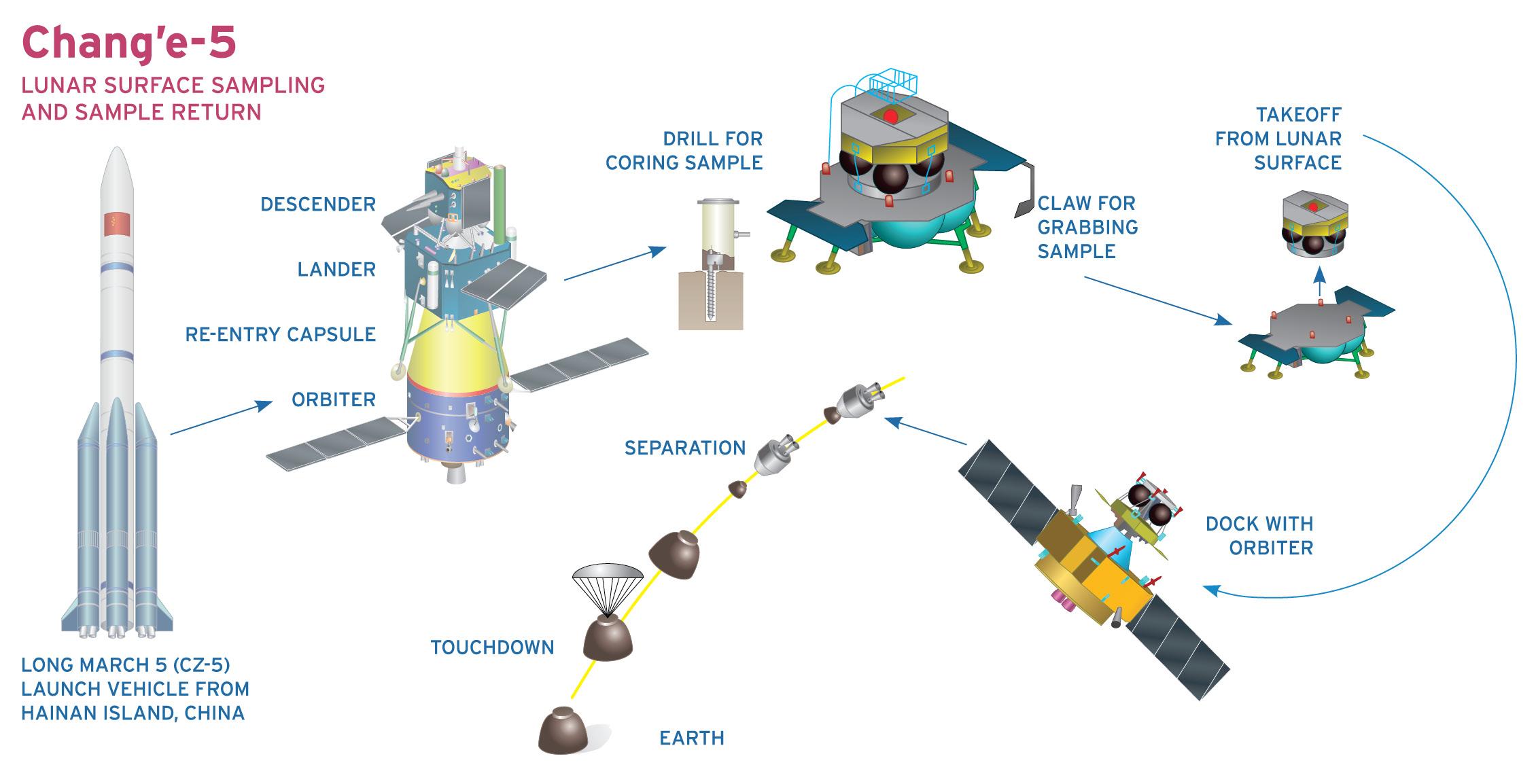

orbital missions Chang’e 1 and Chang’e 2, respectively accomplished in 2007 and 2010; the second one incorporated the Change’3 mission (achieved in 2013) and the aforementioned Chang’e 4 mission; the third phase will entail the sample-return mission of Chang’e 5, which is expected to be launched by the end of this year.

However, following the success of the Chang’e 4 mission, the State Council Information Office of China (SCIO) held a press conference unveiling new details about the future of the Chinese lunar exploration program. Among the future goals is the launch of the Chang’e 6 (to bring samples back from the moon’s south polar region), the Chang’e 7 (to focus on the moon’s south pole environment and composition), and of the Chang’e 8, whose mission would be to test new technologies, such as 3D printing.

Turning to the United States, in December 2017, Trump signed a memorandum that prioritized the moon over Mars, departing from his predecessor’s space policy and its rejection of any American return

to lunar soil. The new program is based on a moonto-Mars exploration approach because it directs the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) to focus on returning humans to the moon, thus to develop the technology needed to eventually send astronauts to Mars.

Twin of Apollo

The new lunar exploration program will be called Artemis, after the twin sister of Apollo and the Greek goddess of the moon. Artemis will rely on the Space Launch System (SLS)—a massive rocket that is running years behind schedule—and on the capsule Orion. Orion will carry astronauts to the Lunar Gateway, a space station that will orbit the moon and from which astronauts will eventually go down to the lunar surface.

According to the space race perspective, the rivalry between the ongoing Chinese lunar program and the American plan to go back to the moon could be

Celestial

b 13

Ambitions

photo: NASA

Army Astronaut Lt. Col. Anne McClain takes the oath of office during an underwater promotion ceremony in NASA’s Neutral Buoyancy Laboratory.

VISION

interpreted as an attempt by the two countries to be the first to land (or re-land, in the US case) astronauts on the moon, thus enhancing their power in the international arena.

This interpretation seems to be reinforced by the statement made by US Vice President Mike Pence during the fifth meeting of the National Space Council held 3 March, 2019: “We’re in a space race today, just as we were in the 1960s and the stakes are even higher. “China became the first nation to land on the far side of the moon and revealed its ambition to seize the lunar strategic high ground and become the world’s preeminent spacefaring nation,” Pence added. This statement reveals what could be called an Astropolitik view. Astropolitik, as defined by Everett Dolman, is a determinist political theory that manipulates the relationship between state power and outer-space control for the purpose of extending the dominance of a single state over the whole of the Earth.

Drawing on geography’s strategic thinkers, Dolman conceived Astropolitik as a classical geopolitics of outer space. Inspired by Mackinder’s Heartland theo-

ry, Dolman distinguishes between four astropolitical regions: Terra, or Earth; Earth Space; Lunar Space; and Solar Space. The first region includes the Earth and its atmosphere, stretching from the Earth’s surface to the Kármán line, the imaginary and theoretical boundary between Earth’s atmosphere and outer space located 100 kilometers above sea level. The second region extends from the Kármán line to geosta-

tionary orbit (about 36,000 Km). The third region is described as the region just beyond geostationary orbit to just beyond lunar orbit. The last region—Solar Space—includes everything in the solar system beyond lunar orbit. In this sense, American and Chinese lunar exploration programs could merely be read as an attempt by each to extend their control over Lunar Space, with the ultimate goal of achieving hegemony over the first astropolitical region: the Earth.

Dolman explicitly draws on Alfred Mahan’s dis-

14

b STRATEGIC

“Space, like the sea, is crossed by natural corridors that facilitate the movementofspaceships.”

The Yuan Wang 6 supports the People’s Republic of China’s space and military programs with its satellite tracking capability.

photo: Michael Perry

cussion of naval choke points. As is well known, for Mahan, a state does not need to have control of every point on the sea; it only needs to manage strategic narrow international waterways (like the straits of Dover, the Suez Canal, the St. Lawrence Seaway, and so on). Similarly, for Dolman, there is no need for a state to command every point of outer space: space, like the sea, is crossed by natural corridors that facilitate the movement of spaceships. Consequently, as Mahan advocated the establishment of naval bases at point locations with strategic or commercial value like the Philippines, so Dolman suggests controlling strategic locations in outer space like the Lagrange Points: five points of gravitational equilibrium (L1, L2, L3, L4, L5) where the force of gravity exerted by the three celestial bodies—the Earth, Sun and moon— essentially balance each other out, thus allowing a satellite to remain stable.

Indeed, the effectiveness of Lagrange points has already been tested by different countries, including China. In 2011, Chang’e 2 lunar probe completed its lunar mission and subsequently proceeded to the

L2 point in order to test Chinese telemetry, tracking, and command systems. Moreover, since direct communication between the Earth and the far side of the moon is not possible, China put a communication relay satellite in a halo orbit around L2 before launching its Chang’e 4 lander and rover.

In the opinion of some experts, the pursuit of Astropolitik interests by the two countries is confirmed by trends toward the militarization of space. Indeed, both Chinese and American space sectors have recently been undergoing major transformations to enhance the role of the military in managing space operations.

New war-fighting domains

In 2015, Chinese General Secretary Xi Jinping launched a reform of China’s military, aiming to respond to the growing importance of new technologies and war-fighting domains. Among other things, the reform included the replacement of the former People’s Liberation Army Second Artillery

Celestial Ambitions b 15

photo: US Air Force

The Joint Interagency Combined Space Operations Center, or JICSpOC, at Schriever Air Force Base in Colorado was activated in 2015.

Force (PLASAF) with a new service, dubbed the PLA Rocket Force (PLARF). Unlike the PLASAF, the PLARF is co-equal to the Army, Navy, and Air Force, and it is responsible for all missile-related activities. Moreover, according to a report published in 2017 by the RAND corporation, the PLARF would play a significant role in space operations. More importantly, the reform led to the establishment of the Strategic Support Force (SSF), that is charged with developing and employing the PLA’s space capabilities. The aforementioned report states that the creation of the SSF “signifies an important shift in the PLA’s prioritization of space and portends an increased role for PLA space capabilities.”

Revived space body

A reorganization of the space sector is occurring in the United States, too, though the process will not be completed easily. An initial step was taken in June 2017, when Trump issued an executive order to re-establish the National Space Council, appointing Pence as chairman. This body, formed in 1989 by President George H.W. Bush and disbanded four years later, has

now been revived with the aim of reviewing space policy and developing recommendations for national space activities.

The Trump administration is also trying to form a Space Force as a sixth branch of the armed forces. The establishment of the Space Force is an attempt to reform the Department of Defense and it would include the formation of three bodies: the US Space Command, the Space Operations Force, and the Space Development Agency. According to remarks by the vice president on the future of the US military in space, the first one, “will establish unified command and control for the Space Force operations, ensure integration across the military, and develop the space warfighting doctrine, tactics, techniques, and procedures of the future.” The second one will be formed by military men and women who will support the combatant commands with their expertise in times of crisis and conflict. Finally, the Space Development Agency will be focused on innovation and experimentation to provide the Space Force with cutting-edge warfighting technologies.

Although the space race model seems to provide us with a suitable theoretical framework for interpreting

16 b STRATEGIC VISION

The mission profile of the Chang’e 5, a robotic Chinese lunar exploration mission scheduled for launch in December 2019.

photo: Loren Roberts

the recent developments of Chinese and American space programs, it would be naïve to think that it could give us a full picture of the current situation in the space sector. It is important to note that we are no longer embroiled in the 20th century competition between the United States and the Soviet Union, and that monitoring the developments of American and Chinese lunar exploration programs requires us to take into account a series of different factors.

New paradigm

First of all, China does not seem interested in joining the race. Beijing continues to follow a slow, gradual and step-by-step lunar exploration plan that seems not to be intended as a race against the United States, at least not officially.

Indeed, in almost fifteen years, China has launched only four lunar missions: too few to fit a space race model, especially if compared with the number of Apollo missions launched by NASA in the same length of time during the 1960s.

Furthermore, China is not able to bear the costs of such a race. Even though it is difficult to determine the budget for China’s space activities, it is certain that China’s expenditures are far lower than those of the

United States. A report published by the Center for Strategic and International Studies states that, “in 2017, it was estimated that China spent almost US$11 billion on space, while the United States spends almost US$48 billion.”

In addition, China may not be technologically ready for such a race. As Andrew Jones, an expert on China’s space program, has recently pointed out, China’s lunar missions could be facing delays due to an unspecified issue affecting the Long March 5, the heavy-lift rocket that has already suffered a failure in July 2017, and that was expected to launch the Chang’e 5 mission by the end of 2019. Hence, in this alleged race, the United States could end up striving against itself more than against China, in order to regain the capability of sending astronauts back to space—a ca-

Celestial Ambitions b 17

photo: NASA

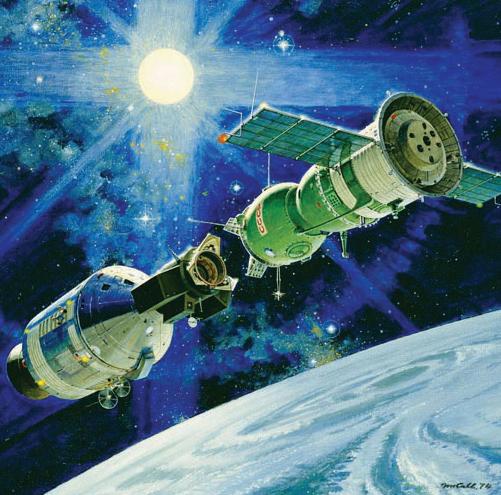

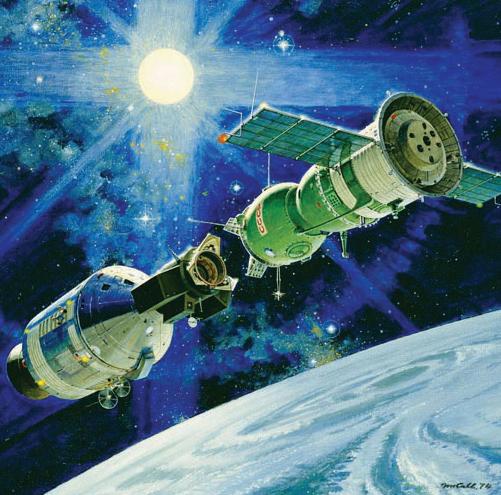

A 1974 painting by artist Robert McCall depicts the docking of the American Apollo and Soviet Soyuz spacecraft.

b STRATEGIC VISION

pability that it lost with the Space Shuttle’s retirement in 2011—and to reassert the symbolic dominance on the moon it enjoyed with the Apollo missions. Moreover, the space race framework is based on a rivalry between two superpowers that does not fit to the current situation in space. The dichotomy of US vs. China risks oversimplification in its neglecting the role of emerging space nations. India, for example, is ready to launch its Chandrayaan-2 lunar exploration mission.

In addition to nation states, there are also non-state actors like private firms and organizations that are joining space exploration activities. Indeed, private companies are no longer simply engaged as contractors of national space agencies but are themselves playing a guiding role. In April 2019, for example, Israeli’s organization SpaceIL tried but failed to launch its first privately funded moon mission, Beresheet.

Finally, even though the actual space legal framework is lagging behind the rapid development of space activities, it is important to recognize that

outer space is no longer terra nullius, as it was at the beginning of the Space Age. According to Professor Fraser MacDonald, “the legal character of space has long been enshrined in the principles of the Outer Space Treaty and this has, to some extent, prevented it from being subject to unbridled interstate competition.” Therefore, no nation—even the ones that seem to pursue Astropolitik interests by testing the military potential of outer space locations (like the Lagrange points) or by reforming its space sector—has or could claim sovereignty over space, or occupy it.

In conclusion, thinking out of the space-race box would lead to a better understanding of the current developments in American and Chinese lunar exploration programs; moreover, it would also help governments realize that it is time to thoroughly review current space policies and legislation, thus responding to the new challenges posed by the changing international context and contributing to a more sustainable and less rhetorical approach to space exploration.

18

n

photo: NASA

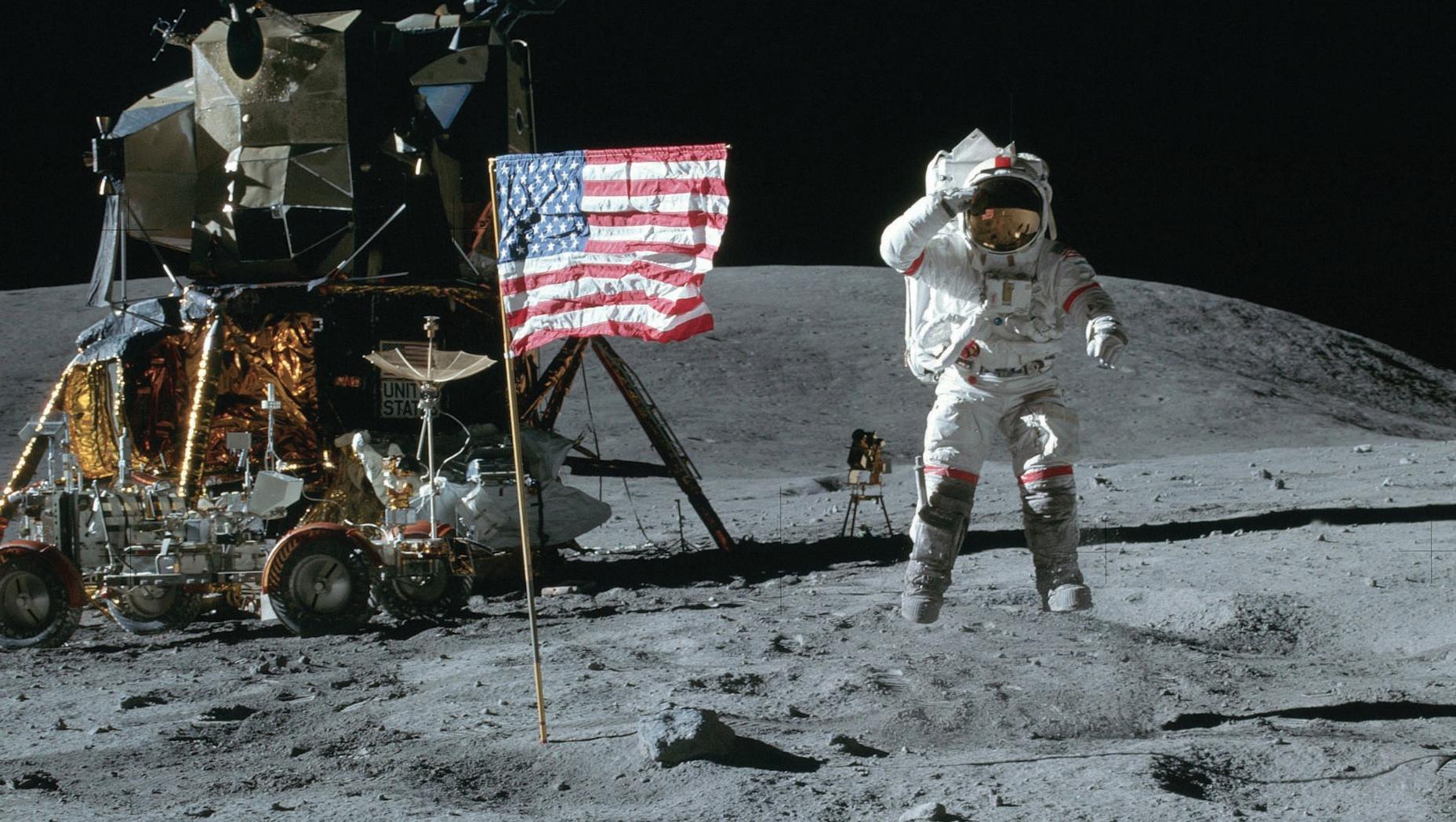

Astronaut John Young salutes the US flag at the Descartes landing site on the moon in April 1972 during the Apollo 16 mission.

Seeking Response

National interests preclude Beijing from getting involved in Rohingya crisis

Hon-min Yau

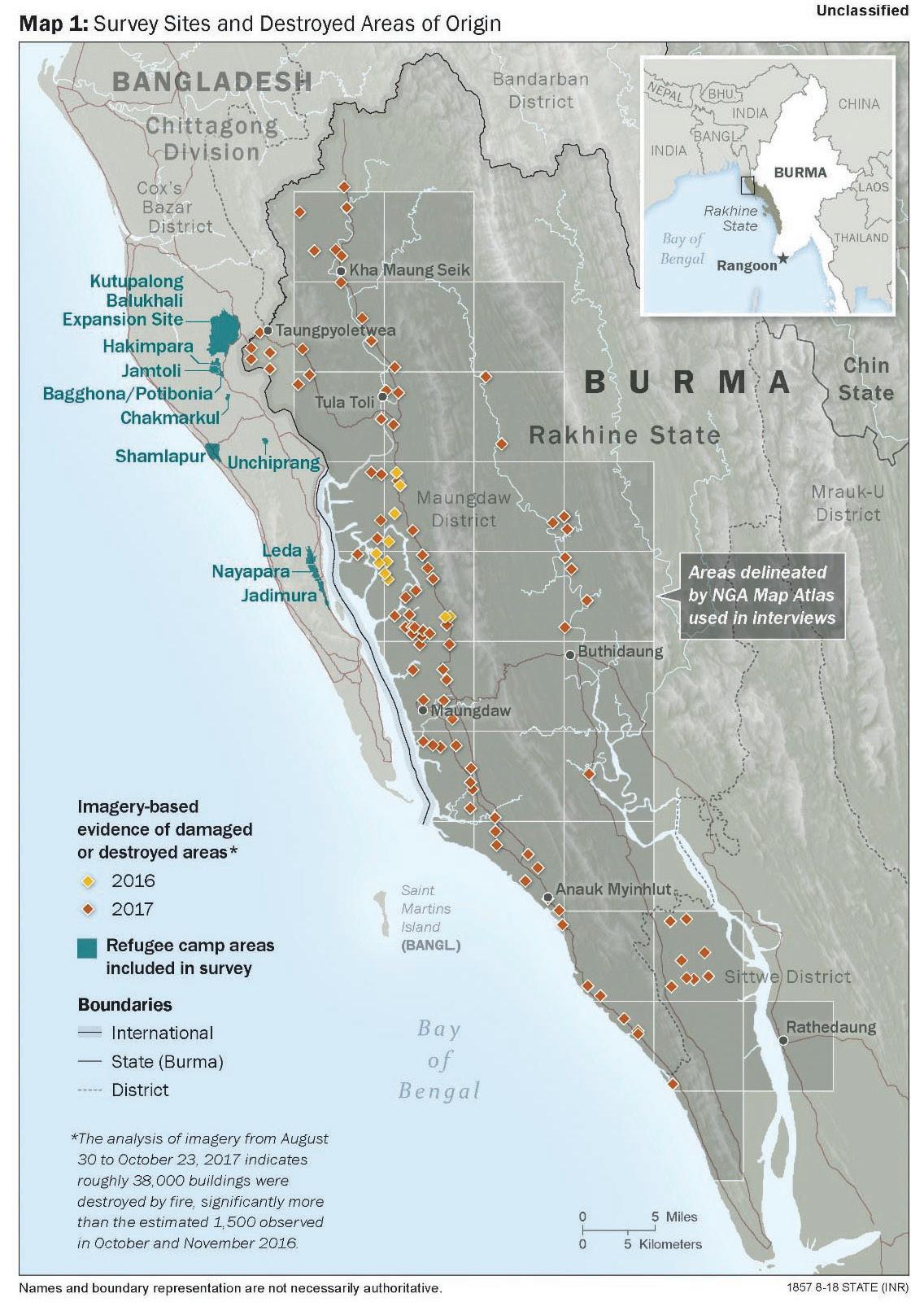

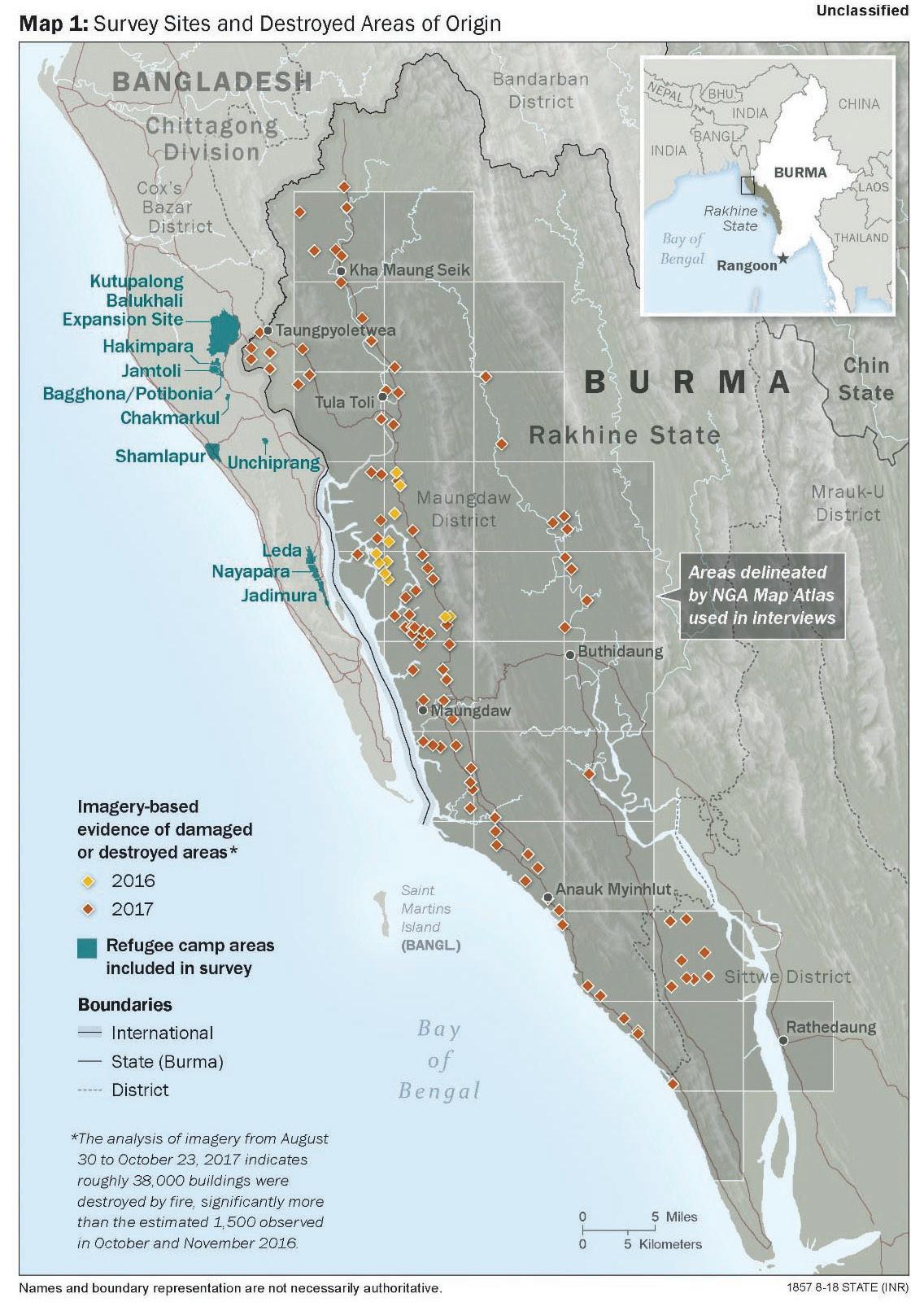

Since 2016 the political and military suppression by the Myanmar government of the Rohingya people has come to the attention of the international community. Due to complex historical and cultural entanglements, this Muslim minority group has been constantly living in a hostile environment surrounded by other, unfriendly ethnic groups. In 2017, the Myanmar Army, known as the Tatmadaw, conducted a brutal crackdown in response to armed resistance on the part of the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army and the Arakan Army. After this violence, a large number of Rohingya people began

to seek sanctuary in neighboring countries, especially Bangladesh. As indicated by the United Nations (UN) Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, by early 2019 it was estimated that there were about 745,000 Rohingya refugees, mostly children, who had fled to Bangladesh’s coastal city of Cox’s Bazar. As a result of this development, the Bangladesh government has continuously been seeking a resolution to ease this migration crisis.

On 25 June, 2019, the Bangladesh Foreign Minister AK Abdul Momen pleaded for China’s support in convincing Myanmar to fulfill its commitment to

b 19 Strategic Vision vol. 8, no. 42 (June, 2019)

Dr. (Colonel) Hon-min Yau is an assistant professor in the National Defense University. He can be reached for comment at cf22517855@gmail.com

photo: UK Department for International Development

Emergency food, drinking water and shelters are provided to help people displaced in western Burma’s Rakhine State.

repatriate the Rohingya refugees now living within the territory of Bangladesh. Although a repatriation deal was signed between Myanmar and Bangladesh in early 2018, there has been no concrete progress in returning these refugees. In early July, Bangladesh’s Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina visited the People’s Republic of China (PRC), where she urged leaders to support Bangladesh in its efforts to return Rohingya refugees to Myanmar. As China’s outsized importance in this crisis seems to stand out given recent developments, this article seeks to examine China’s significance in resolving this humanitarian crisis.

The Rohingya are a group of Muslim minorities, not recognized by Myanmar, who live in the western part of that country, mostly in Rakhine State. Before 1989, this place was called Arakan, and Rohingya were widely known as the Arakanese. Myanmar is a country containing 135 official “national ethnic races,” including the Shan, Kachin, Chin, and other minorities. The Bamar ethnic majority accounts for 68 percent of the total population: By religion, 88 percent of the population is Buddhist, 6 percent Christian, and 4 percent Muslim. Anger and hatred directed

towards the Rohingya people cannot be attributed to religious differences alone, as there are other Muslim minorities.

Colonial relic

The non-Western narrative within Myanmar paints this group of people as a relic of the colonial power during World War II, as they were mercenaries from current-day Bangladesh that the British employed to combat Japanese troops and the pro-Japan independence forces in British Burma. The most notorious incident of a bloody clash was in 1942, when members of this Muslim group clashed with the local Buddhist community, which resulted in 100,000 casualties. Although the exact death toll is disputable, the resentment towards the Rohingya continued after the independence of Burma in 1948. At the beginning of this new country, the first citizenship law in 1948 offered Rohingya minimal rights, but a new citizenship law enacted in 1982 completely stripped the Rohingya not just of citizenship, but of their identity. As such, the Rohingya are treated as refugees from Bangladesh

20 b STRATEGIC VISION

photo: mohigan

A closed mosque in Sittwe. Few traces of traces of the Muslim community remain, whereas the Rohingya once made up 40 percent of the population here.

within Myanmar. This social and legal discrimination limits the Rohingya’s access to basic schooling and health services and inhibits their livelihood and freedom of movement.

Why does Bangladesh see China as a possible facilitator in resolving the current humanitarian crisis? China’s role can be viewed from both security and economic angles. From the security perspective, Myanmar’s strategic location offers a land bridge for China to access the Indian Ocean, and Myanmar is also a neighbor sharing a 2,204 kilometer border with China. For this reason, China has invested huge amounts of money in strengthening its military cooperation with Myanmar. The Stockholm International Peace Research Institute indicates that 90 percent of Myanmar’s military vehicles are supplied by the PRC. Beijing also provides military equipment in the form of missiles, radar, naval vessels, and aircraft. Hence, as Myanmar’s largest neighbor and closest security partner, China has always been very supportive in backing Myanmar’s position regarding its handling of the Rohingya Crisis: When the UN called Myanmar’s actions “ethnic cleansing” in September 2018, China

supported Myanmar’s officials, who labeled the incident an act of counter-insurgency.

In November 2018, Myanmar received a sharp US rebuke when Vice President Mike Pence criticized the Rohingya’s persecution at the hands of their own government. In contrast, PRC Premier Li Keqiang

structionofoil-gaspipelinesandrail-

presented a clear stance to support, “Myanmar’s efforts in maintaining its domestic stability.” Clearly, it is in China’s interests to continue to block any international interventions that would allow Western-led action to take place in its doorstep.

From an economic perspective, it is noteworthy that Myanmar has become part of China’s Belt and Road initiative (BRI), and economic cooperation between the two countries is very strong. China is now involved in Myanmar’s rail, road, telecommuni-

Seeking Response b 21

“Kyaukpyu ... where the Rohingya people reside ... has received massiveChineseinvestmentsforthecon-

road links to China.”

National leaders meet in Beijing for the second annual Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation in April, 2019.

photo: Kremlin.ru

cations, hydro-power, and airport development. According to the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, China contributed to Myanmar’s GDP growth to the tune of 5.5 percent in 2012, and 6.5 percent in 2013. Also, the China-Myanmar Economic Corridor (CMEC) of the BRI will allow China’s Yunnan province to connect the Indian Ocean through two major ports, Yangon in the south and Kyaukpyu in the west of Myanmar. Tellingly, Kyaukpyu is located in Rakhine State where the Rohingya people reside, and has received massive Chinese investments for the construction of oil-gas pipelines and railroad links to China. In November 2018, a contract was renewed with China’s state-owned investment company, CITIC group, to develop Kyaukpyu as a Special Economic Zone. China’s political support to Myanmar supports its economic interests.

Cooperative partnership

Beijing has prioritized its interests over the Rohingya’s, and Myanmar is returning the favor. In April 2019, when the commander-in-chief of the Tatmadaw, Senior General Min Aung Hlaing, visited China, the Chinese Communist Party’s official mouthpiece Xinhua reported that Xi Jinping sees “China-Myanmar military cooperation as an important part of the comprehensive strategic cooperative partnership between the two countries.”

Min Aung Hlaing also stated that Myanmar would continue to back the BRI in response to China’s international support. Later that month, the de facto leader of Myanmar, Aung San Suu Kyi, met with Xi

Jinping and signed multiple agreements with China in the Second Belt and Road Forum. China has exploited this opportunity to establish a closer relationship with Myanmar, which is beleaguered by Western countries.

Even if China and Myanmar are not putting the Rohingya Crisis at the forefront, what are the UN’s actions in the matter? In response to this humanitarian crisis, the UN established an independent factfinding mission in March 2017 to investigate alleged human right abuses by Myanmar. However, lack of support and cooperation from the Myanmar government created difficulty to access the needed information on-site. In September 2018, the UN fact-finding

22 b STRATEGIC VISION

mission issued a 440-page report which concluded that Myanmar’s military had conducted multiple crimes, including rape and sexual violence, as part of a deliberate strategy to intimidate, terrorize, or punish the civilian population, and as a tactic of war. The United Nations Security Council (UNSC) still failed to act in any way to mitigate the ongoing humanitarian crisis: as reported in December 2018 by Reuters, China, along with Russia, blocked another British-drafted resolution demanding the return of refugees and accountability for the criminal incidents.

As the Rohingya crisis continues, under-resourced Bangladesh is severely strained by the huge influx of refugees. This has multiple implications: First, the country’s per capita GDP in June 2019 was US$1,827, up from US$1,675 a year earlier,

and there are 6 million people still living in extreme poverty. The immediate impact for Bangladesh is the unbearable financial burden, and its citizens are growing impatient with the already low domestic living standards. Second, as Bangladesh is not wealthy enough to offer underprivileged Rohingya people economic opportunities, it can be expected that this flow of migrants could move to other destinations, and destabilize the already frail regional economic stability amid the uncertainties wrought by the Sino-US Trade War.

Finally, while Myanmar continues to conduct its indiscriminate “clearance operation” on the Rohingya populace, extreme Islamist movements can emerge from such an environment. In 2017, Al Qaeda already issued a declaration urging global Muslims to mount an

Seeking Response b 23

Prime Minister Sheikh Masina of Bangladesh.

Mrauk U town in northern Rakhine State. From 1430 until 1785, it was the capital of the Mrauk U Kingdom, the most powerful Rakhine kingdom.

photo: Go-Myanmar.com

armed rebellion in support of the Rohingya people. Along with the migrations of Rohingya to countries other than Bangladesh, this combination potentially creates the perfect conditions to facilitate the radicalization of a new wave of Islamic extremists in Asia.

Human rights violations

In June 2018, it was reported by The New York Times that the Myanmar government had closed the Internet connection to the Rohingya’s hometown in Myanmar, Rakhine State. Many Western analysts saw this decision as either a precursor to, or a cover-up of, massive human rights violations. Without concrete improvement in security conditions and the removal of the social and political discrimination practices in Myanmar, the Rohingya people fleeing overseas will not be willing to return to their homes in the near future. The special rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Myanmar, Professor Yanghee Lee, cited the UN Security Council itself as the primary roadblock to any progress. Speaking in a 27 June,

2019, interview with Radio Free Asia, she pointed out that “China is backing the Myanmar government [by] objecting to a Security Council resolution for referral to the ICC [International Criminal Court]. China and Russia often work together in this kind of situation, which I think is shameful, so that the Security Council cannot move beyond this.”

To stop the vicious cycle and end the Rohingya crisis, the international community needs to encourage China to change its existing policy. However, the problem is that the international system has long been considered as a state of anarchy, and there is no central authority to monopolize legal violence or even to justify right from wrong. Any state, including China, will act in its own interests. While very few countries possess similar material capacities of military and economic power like China, how can China be compelled to act out of concern for the Rohingya’s predicament?

It is necessary to create a powerful international discourse regarding China’s stance on the Rohingya people. The appropriateness of a State’s policy is not

Members of the Myanmar Police Force patrolling in Maungdaw, a town in Rakhine State in the western part of Burma, in September 2017.

photo: VOA

24 b STRATEGIC VISION

merely decided by its interests but also acted upon by international norms. International norms are determined by social interaction among states, and they have no fixed truth, like domestic law, since there is no concrete political process to legitimate them.

Infrangible sovereignty

International norms are legitimated as truth only through discourses created by power exercised by international actors, including both government and non-government bodies. For example, the sovereignty of the State used to be infrangible but has now been redefined by international human right laws, just as whale hunting used to be legally justified as States’ right to harvest natural resources but is now interpreted as an act of endangering natural species. People attribute this new “regime of truth,” in Foucauldian terminology of the international relations, to the successful discourses of non-governmental organizations (NGOs) such as Amnesty International and the International

Whaling Commission, which use their discursive powers to convert knowledge through various meanings into social reality.

While these NGOs have no material power, like military aircraft or tanks, they can still contribute to the legitimacy of international human rights law and anti-whaling campaigns. This suggests that, instead of relying on material forces, discourse can still be an enabler of change in a State’s behavior. That is to say: international criticism of China’s stance on the Rohingya Crisis has the potential to enact a change of policy.

To sum up, the challenge lying ahead for the Rohingya Crisis is to encourage China to value humanitarian concerns over its own geostrategic interests, with respect to the conditions of the Rohingya people. This task is not an easy one, and cannot merely rely on the efforts of the Rohingya people nor the Bangladesh government alone; it requires collective investments from both State and non-State actors to focus global attention and spur continuous discussion of the Rohingya situation. n

Seeking Response b 25

The United Nations Security Council meets. A proposed UN statement of concern over the tense situation in Myanmar was blocked by China in March 2017.

photo: US State Department

Trade Frictions

Challenge, uncertainty surround ongoing trade war between China and US Shao-cheng Sun

America’s economic relations with China have expanded steadily since that country opened its economy to the world in 1978. Bilateral merchandise trade exploded from US$2 billion in 1979 to US$660 billion in 2018. However, tensions have surfaced over several economic issues that include the trade deficit, cyber espionage, and violation of intellectual property rights (IPR). The administration of US President Donald Trump has dedicated itself to decreasing the US trade deficit. On 8 March, 2018, President Trump announced additional tariffs on steel (25 percent) and

aluminum (10 percent) against China. In retaliation, China raised tariffs (from 15 percent to 25 percent) on US products.

On 5 May, 2019, Trump stated that the previous tariffs of 10 percent levied on US$200 billion worth of Chinese goods would increase to 25 percent. In response, China imposed a 25 percent tariff on US$60 billion worth of US goods on 1 June, 2019. During the G20 Osaka summit on 29 June, 2019, Trump and his Chinese counterpart President Xi Jinping agreed to something of a truce in the trade war: Prior tariffs would remain in effect, but no future tariffs were

26 b Strategic Vision vol. 8, no. 42 (June, 2019)

Dr. Shao-cheng Sun is an assistant professor at The Citadel specializing in China’s security, East Asian affairs, and cross-strait relations. He can be reached for comment at ssun@citadel.edu

photo: Shealah Craighead

US President Donald Trump and PRC President Xi Jinping meet during the G-20 Summit in Germany.

to be enacted. Trump delayed the proposed tariffs to encourage renewed trade talks with China. This article looks at why Washington initiated the trade war, how Beijing has responded, and what impacts can be expected.

Intertwined economies

At present, China is America’s largest import country (US$540 billion), the largest foreign holder of treasury securities (US$1.1 trillion), and the third-largest export market (US$120 billion). In 2015, US exports to China and bilateral Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) flows provided 2.6 million jobs for Americans. Chinese visitors spent US$33 billion in the United States in 2016 (the largest visitor spending). Boeing Corporation delivered 202 planes to China in 2017 (26 percent of global deliveries). Despite the bilateral trade being closely intertwined, there are other interests that triggered the trade war.

The US trade deficit with China set a new record in 2018. US trade in goods and services with China totaled a whopping US$737 billion. Exports were US$179 billion and imports were US$558 billion. The deficit reached US$379 billion. The Trump administration thinks that this deficit is detrimental to the US economy because it had eliminated or displaced 3.2 million US jobs between 2001 and 2013. Some

US policymakers view this as an unfair trade relationship. Reducing the growing deficit has become Trump’s priority as he strives to create more jobs for Americans.

China’s lack of IPR protection has been criticized by US firms as one of the most significant problems they face when doing business in China. US business and government representatives have voiced concern over the economic losses suffered as a result of China’s IPR infringement. Global IPR theft costs the US economy US$300 billion, of which China accounts for between 50 percent (US$150 billion) and 80 percent (US$240 billion). The US Department of Homeland Security reported that in 2017, goods from

China accounted for 78 percent of seized counterfeit goods, with a value of US$941 million. It is little wonder, then, that Trump has criticized China’s poor IPR protection laws.

From Beijing’s perspective, China has made progress in improving IPR protection by citing the fact that Chinese IP royalties paid to the United States increased from US$3.46 billion in 2011 to US$7.2 billion

Trade Frictions b 27

“TheUSintelligencecommunitybelievesthattheChinesegovernment isamajorsourceofcybereconomic espionage.”

in 2017. Beijing has also established 16 IP courts in China, and increased penalties for trademark violations from US$73,000 to US$436,000. Mark Cohen, a senior fellow at the Berkeley Centre for Law and Technology, says, “No doubt China has made good steps in improving IP protection, but China is not addressing US concerns.” For the US, it is also about issues related to theft of trade secrets and technology transfer.

The US intelligence community believes that the Chinese government is a major source of cyber economic espionage. Chinese hackers are the most active perpetrators in the world. Tom Donilon, the former National Security Advisor, stated that China should take serious steps to investigate and stop cyber-espionage. On 19 May, 2014, the US Department of Justice issued an indictment against five officers of the People’s Liberation Army for cyber-espionage.

On 25 September, 2015, President Xi and thenPresident Barack Obama announced that they had reached an agreement on cyber security and agreed to set up a high-level dialogue mechanism to address cybercrime. The decision was made to implement a cyber-hotline, enhance investigations and infor-

mation exchange, and combat cyber theft for commercial gain. Despite these mutual agreements, the US intelligence community has identified ongoing Chinese cyber activity.

Technological edge

Chinese firms have invested billions of dollars in the US technology industry, raising concerns that Beijing has gained access to critical US technologies. These investments demonstrate China’s intentions of developing high-tech industries to continue economic growth and to increase its military strength. Most US scholars suggest that policymakers should boost innovation in the US economy to maintain a technological edge rather than try to block Chinese investment.

The Trump administration has raised security concerns over global supply chains of advanced technology, such as information, communications, and telecommunications (ICT) equipment. China is the largest foreign supplier of ICT equipment to the United States: In 2018, US ICT imports from China totaled US$157 billion (60 percent of US ICT imports).

28 b STRATEGIC VISION

The Nimitz-class aircraft carrier USS Theodore Roosevelt (CVN 71) transits the Gulf of Alaska after participating in Exercise Northern Edge 2019.

photo: Anthony Rivera

Trump, on 15 May, 2019, issued an Executive Order on Securing the Information and Communications Technology and Services Supply Chain. The order enunciated the administration’s view that US purchases of ICT from foreign adversaries (China in particular) posed a risk to the United States and banned certain ICT transactions. The Trump administration believes that increased Chinese investment in US high-tech sectors could undermine US economic competitiveness.

Beijing has gradually taken a tougher approach in response to US tariffs. In the beginning, China offered concessions, such as agreeing to purchase an extra US$1.2 trillion of US products and allowing US companies to gain access to the financial, automobile, and energy sectors. However, President Xi presided over a high-level government meeting and called on all officials to be prepared for a full-scale trade war. Chinese leaders see Trump’s tariffs as a US plan to prevent China’s rejuvenation. As a result, the Chinese government responded with hostility. China

has taken the following approaches against US tariffs. The first approach has been to push the US to back off. The Chinese ministries of commerce and of foreign affairs have responded to US tariffs with a vow to fight to the end. After Washington increased tariffs on US$50 billion of Chinese goods on 15 June, 2018, Beijing announced its own tariffs on the same scale and intensity in return. Every time the US has esca-

lated the fight, China has talked tough. On 21 June, 2019, Xi met with a foreign delegation and told them that China would fight back against US trade tariffs. Both countries intensified their trade dispute on 6 May, 2018 as Beijing said it would increase tariffs on US$60 billion worth of US products. China’s Finance Ministry announced that it was raising tariffs on a

Trade Frictions b 29

“Beijing has used its nationalist propaganda to stir up public sentiment and to prepare its citizens for the trade war.”

Presidents Barack Obama and Xi Jinping inspect troops during a welcome ceremony held at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing on 12 November, 2014.

photo: Chuck Kennedy

VISION

wide range of US goods from 10 percent to 25 percent. Next, China has used a “talk and fight” approach to US tariffs. When the global stock market plummeted in 2018, it created an opportunity for Xi to engage Trump, and they agreed to a three-month truce at the end of 2018. The message that China is sending to the United States is, essentially, “If the US wants to fight, China will fight to the end; If the US wants to talk, China is ready.”

Popular support

Beijing has used its nationalist propaganda to stir up public sentiment and to prepare its citizens for the trade war, and to resist what it calls US “bullying.” Clearly, the leaders in Beijing are garnering popular support for a trade war. China might also stop purchasing US agricultural products, reduce orders from Boeing, and dump US Treasuries.

Since Trump launched punitive tariffs against China, many economists have expressed concern over the impact of the trade war. Most predicted that both the United States and China would experience economic slowdowns, with China being hit especially hard. However, Lawrence J. Lau, a Professor of Economics at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, believes that China can weather the effects of a trade war with only a marginal drop in economic growth. The immediate impact is psychological, particularly in the stock markets. Many of the Chinese stock markets have already declined. US consumers of targeted Chinese products, as well as producers, will also be affected immediately. In the broader picture, there are likely to be several major developments from the trade war between the US and China.

First, it is unlikely that the trade war will improve the US trade deficit. Trump’s top economic adviser, Larry Kudlow, acknowledged that the United States and China would suffer as a result of the tariffs, but he claimed that the United States would benefit in

the end if the trade war forces China to give better treatment to US businesses than it had in the past. With growing US protectionism aimed at China, US imports from China are declining. From January through April 2019, the United States imported US$20.6 billion less from China than in the same period a year earlier. Increased imports from Mexico, South Korea, and Taiwan reflect shifts in global value chains. The US deficit with China decreased by US$11.7 billion in the first four months of the year, but the US deficit with other countries went up. The total US deficit increased as well. The protection aimed at China does not improve the US trade deficit because value chains relocate to other countries. The trade war is unlikely to reduce the US deficit.

Second, there will be no winner in the trade war. Economists Dan Hanson and Tom Orlik concluded that if tariffs expand to cover all US-China trade, global GDP will experience a US$600 billion hit in 2021. On 4 August, 2018, China fell from second- to third-largest market capitalization. On 4 December, 2018, the Dow Jones Industrial Average declined near-

would be more severe.”

ly 600 points due to the trade war. Now China has imported soybeans from Brazil instead of from the United States. According to a study by the National Retail Federation of the United States, a 25 percent tariff on Chinese furniture would cost US consumers an additional US$4.6 billion in annual payments. In October 2018, United Technologies and Ford made forecasts that the tariffs would cost them US$100 million and US$1 billion, respectively. US exporters may have to reduce costs and lay off workers to remain competitively priced.

Third, the trade war will impact Taiwan businesses

30 b

STRATEGIC

“If Trump levied a 10 percent tariff on US$200 billion worth of other Chinesegoods,theimpactonTaiwan

in China. Taiwanese companies are an integral part of the global supply chain. In June 2018, an assessment by Taiwan’s National Security Council said that US sanctions would have little effect on Taiwan’s related industries and Taiwanese companies based in China. However, a spokesman for Foxconn said that the trade war was the biggest threat it faced. Presidential Spokesman Alex Huang admitted that if Trump levied a 10 percent tariff on US$200 billion worth of other Chinese goods, the impact on Taiwan would be more severe. There are 50,000 Taiwanese companies invested in China and Taiwan is a major supplier to China. These exports made up around 2 percent of Taiwan’s GDP. Many of these products are shipped to the US and could be seriously affected by US tariffs. Now many Taiwanese businesses are considering whether to move their manufacturing operations out of China. Such a move would be expensive.

Consultant Oxford Economics predicted that the trade war could cost the global economy US$800 billion in reduced trade. Despite the United States and China renewing trade talks, there are reasons the

conflict could continue for a while. First, negotiators have made little progress resolving the essential USChina disagreements. For example, Beijing has not been doing enough to stop theft of US intellectual property in China. Second, the US negotiating position has been heavy on punitive sanctions and light on constructive dialogue. Third, with the increasing tariffs, the need for greater concessions from China to justify these costs becomes less likely to be met, as China does not want to appear weak in the face of US pressure.

The trade war will have a great impact on the United States and China, and even Taiwan. Taiwanese companies with operations in China might suffer a significant hit, and they may have to reconsider the benefits of returning to Taiwan. Indeed, Taiwanese businesses in China should diversify their investments and consider moving back to Taiwan. The government in Taiwan should observe developments in the trade war closely and continue to come up with countermeasures for diminishing the impacts felt by Taiwanese.

n Trade Frictions b 31

photo: Steve Jurvetson

An electronics factory in Shenzen, China. Taiwanese companies with operations in China may have to reconsider the benefits of returning to Taiwan.

Watching the Watchers

Better civilian oversight called for over Intelligence apparatus of South Africa

Bheki Mthiza Patrick Dlamini

Bheki Mthiza Patrick Dlamini

Although the Republic of South Africa is currently facing socio-political challenges, the country remains a regional hegemon, both economically and militarily, mainly because of its functional democratic institutions, in particular the intelligence community. Geographically, the nation of South Africa also serves as a gateway for almost all of southern Africa’s products on their way to global markets, thus its security posture affects the entire continent. The existence of strong State institutions is plainly provided for in the country’s constitution regardless of its racial segregation legacy.

The demise of apartheid South Africa in the early 1990s, which coincided with the end of the Cold War, ushered a new era within the country’s security architecture, in particular within the intelligence community. For realists, the demise of apartheid South Africa at the end of the Cold War was inevitable as the apartheid regime primarily survived the wrath of the liberation movements through the efficient utilization of its “Total Strategy.” Through this securityand intelligence-driven national security strategy, the liberation movements were branded as communist or terrorist in order for the apartheid regime to appeal

32 b Strategic Vision vol. 8, no. 42 (June, 2019)

Bheki Mthiza Patrick Dlamini is a Master’s student at the Graduate Institute of Strategic Studies, National Defense University of the ROC. He can be reached

for comment at bhekid765@gmail.com

photo: GCIS

President Jacob Zuma observes the twenty-one gun salute outside Parliament ahead of the State of the Nation Address in Cape Town.

for sympathy from the international community, in particular the Western powers. Consequently, it evaded economic sanctions and arms embargos whilst receiving enormous support from some powerful countries. This paper will examine the ever-changing role of the South African intelligence community and its shortcomings and challenges.

Multiple agencies

The South African intelligence community is headed by the Minister for State Security at the cabinet level who serves as the political head of the State Security Agency. The two main intelligence organizations in South Africa are the National Intelligence Agency and South African Secret Service. Other members of South Africa’s intelligence community include the South African National Defence Force, Defence Intelligence, which is accountable to the Chief of the South African Defence Forces; the Crime Intelligence Division of the South African Police Service within the South African Police Service; and the Intelligence

and Research element within the Department of International Relations and Cooperation. The National Intelligence Coordinating Committee serves as the bridge in the quest for synergy and information sharing.

South Africa’s constitution defines the concept of national security as being “free from fear and want, wherein South Africans, as individuals and as a nation, to live as equal, to live in peace and harmony.” This definition indicates a paradigm shift from the former apartheid government, which was Statecentric, to one that is centered on a human-security approach, which may be the result of the preeminence of liberal democracies in the post-Cold War era. In retrospect, the role of the intelligence community changed from supporting the narrowly defined national security concept of the apartheid regime to a broad, democratically defined one. The South African White Paper on Intelligence defines intelligence as “the product resulting from the collection, evaluation, analysis, integration and interpretation of all available information, supportive of the

South African Intelligence b 33

Minister Naledi Pandor attends the 35th Ordinary Session of the Executive Council of the African Union (AU), in Niamey, Niger.

photo: DIRCO

policy and decision making processes pertaining to the national goals of stability, security and development.” Therefore, from a systems-analysis approach, it is clear that South Africa’s intelligence community makes important contributions to many of South Africa’s national policies.

Evaluated information

According the South African Strategic Intelligence Act, the mission of the intelligence community is to provide evaluated information with the following responsibilities in mind: the safeguarding of the Constitution; the upholding of the individual rights as enunciated in the chapter on Fundamental Rights (the Bill of Rights) contained in the Constitution; the promotion of the interrelated elements of security, stability, cooperation and development, both within South Africa and in relation to Southern Africa; the achievement of national prosperity whilst making an active contribution to global peace; and other globally defined priorities for the well‐being of humankind.

The four major functions and missions of South Africa’s intelligence community are: collection, analy-

sis, counterintelligence and covert action, whilst the main objective for executing these functions being a quest to protect South Africa against any act that might undermine national security, whether said act be perpetrated economically, militarily, or otherwise. When examining the role the role of the National Security Intelligence Services of the Republic of South Africa from a systems-analysis approach, these services are vital to the policymaking machinery of the State. For instance, intelligence-driven operations contribute immensely to the effective employment of law enforcement agencies by the State to thwart heinous crimes in the quest to protect the people of South Africa and their property from criminal elements. This is all the more important when considering that some criminal activities can easily manifest into national security threats, especially organized crime. In the diplomatic sphere, the national intelligence agencies also play a critical role in collecting relevant foreign-policy information in support of South Africa’s foreign and defence policies, which are both crucial for the country’s national security.

The State exercises some degree of control over the intelligence community in line with democratic

34 b STRATEGIC VISION

Tobeka Madiba Zuma delivers an address at the Defence Intelligence Women’s Day Celebration.

photo: GCIS

norms in the quest to avert abuse and improve efficiency. Notwithstanding that relationship, the South African intelligence community has had its fair share of scandals. Most prominently, the former director of the National Intelligence Agency, Billy Masetlha, was alleged to have conducted an illegal intelligence operation against officials and businessmen affiliated with the African National Congress who were in support of then-President Thabo Mbeki.

Taking sides

This scandal reflects the intelligence community’s involvement in the battle for succession between Mbeki and his eventual successor, Jacob Zuma. Furthermore, the intelligence community is also reported to have been involved in laundering money, claiming it was part of an intelligence operation against foreign exchange control violations. This serves as clear evidence that the country’s intelligence apparatus can all too easily be abused, either by the ruling party or the

State, or even by intelligence personnel, for individual gain in the absence of proper control mechanisms. These escapades took place in spite of the existence of oversight structures within the country’s three pillars model, made up of executive, parliamentary, and civilian oversight. This model provides for both internal and external structures such as the multi‐party parliamentary committee, called the Joint Standing Committee on Intelligence, and the Office of the Inspector-General, provided for in the Intelligence Services Oversight Act 40 of 1994.

It is clear that South Africa’s intelligence community needs better oversight and accountability. One area for improvement would be to improve the access of South Africa’s Parliament to the intelligence community. Currently, parliament does not have very effective access to the intelligence community. Creating better communication and access between parliament and the intelligence community could help to increase accountability and decrease politicization within the intelligence community. n

South African Intelligence b 35

President Jacob Zuma addressing the launch of the Presidential Press Corps held at the Union Buildings in Pretoria.

photo: GCIS

Visit our website: www.csstw.org/journal/1/1.htm

Tonio Savina

Tonio Savina

Bheki Mthiza Patrick Dlamini

Bheki Mthiza Patrick Dlamini