Summer2025

ConferenceEdition:OfficeoftheMinistry

TheJournalofSt.PaulLutheranSeminary

SIMUListhejournalofSt.Paul LutheranSeminary.

ISSN:3066-6996

CoverPhoto:“Weimar Altarpiece,” Lucas Cranach the Elder and Lucas Cranach the Younger, 1555, Church of Sts. Peter and Paul, Weimar, Germany.

Disclaimer:

The viewsexpressedinthe articlesreflectthe author(s) opinionsand arenotnecessarilythe viewsofthe publisherand editor.SIMULcannotguaranteeand acceptsnoliabilityforany lossor damageofanykind causedby the errorsandfor theaccuracy ofclaims made by the authors.Allrightsreservedand nothingcan bepartiallyorinwholebereprintedor reproduced withoutwrittenconsentfrom the editor.

SIMUL

Volume 4, Issue 4, Summer 2025

Conference Edition: Office of the Ministry

EDITOR

Rev. Dr. DennisR. Di Mauro dennisdimauro@yahoo.com

ADMINSTRATOR

Rev. JonJensen jjensen@semlc.org

AdministrativeAddress: St. Paul LutheranSeminary P.O.Box251

Midland,GA 31820

ACADEMICDEAN

Rev. Julie Smith jjensen@semlc.org

Academics/StudentAffairsAddress: St. Paul LutheranSeminary P.O.Box251

Midland,GA 31820

BOARDOFDIRECTORS

Chair:CharlesHunsaker

Rev. GregBrandvold

Rev. JonJensen

Rev. Dr. MarkMenacher

Rev. Michael Hanson

Rev. Julie Smith

Rev. CulynnCurtis

Rev. Dr. JamesCavanah

Rev. Jeff Teeples

Rev. Judy Mattson

TEACHINGFACULTY

Rev. Dr. MarneyFritts

Rev. Dr. DennisDiMauro

Rev. Julie Smith

Rev. VirgilThompson

Rev. BradHales

Rev. Steven King

Rev. Dr. OrreyMcFarland

Rev. HoracioCastillo(Intl)

Rev. AmandaOlsonde Castillo(Intl)

Rev. Dr. Roy HarrisvilleIII

Rev. Dr. HenryCorcoran

Rev. Dr. MarkMenacher

Rev. RandyFreund

EDITOR’S NOTE

Welcome to our sixteenth issue of SIMUL, the journal of St. Paul Lutheran Seminary. We had an amazing conference this year from May 12th-14th at St. Paul’s Lutheran Church in Salisbury, NC. This was our first conference since COVID and wonderful teaching and fellowship was enjoyed by all. The topic of the conference was the “Office of the Ministry,” and we thought that it would be helpful to publish the talks in this issue of SIMUL so that those who missed the conference might read these amazing articles at their leisure.

Julie Smith started the conference by explaining that pastors are “called to faith,” using the examples of the biblical figures Abraham, Moses, Jonah, Peter and Paul. The next day, she returned to the same biblical figures, but this time she demonstrated how they were also “called to go,” sometimes quite a distance from home, in order to preach God’s word. Brad Hales explained how visiting may be the most ignored, and yet most important ministry for any pastor. Randy Freund lamented the 18th and 19th Century transition from “pastoral care” to “pastoral counseling.” He offered a Hippocratic Oath for pastors to “do no harm” by espousing a “theology of the cross” over a “theology of glory.” Mark Ryman explained the benefits of lectio concordia, or “reading in harmony,” as a pastoral devotion. He

This edition includes the talks from our annual conference which was held from May 18th20th at St. Paul’s Lutheran Church in Salisbury, NC.

even gave us a preview of his upcoming book on the same topic! And I finish off this issue with a review of Kennon Callahan’s classic book, Visiting in an Age of Mission.

What’s Ahead?

Upcoming Issue - Our Fall 2025 issue will deal with the important subject of “Senior Ministry.” While the church places much emphasis on youth ministry, church planters and revitalizers have found that a focus on senior ministry is better tailored for church growth today. Senior ministry also attracts youth, since seniors often bring their grandchildren into the church.

Conference 2026 – Join us again for the St. Paul Lutheran Seminary Theological Conference which will again be held at St. Paul’s Lutheran Church in Salisbury, NC, tentatively scheduled for May 18-20, 2026.

SPLS now offers the Th.D. – We are excited to announce that St. Paul Lutheran Seminary is partnering with Kairos University in Sioux Falls, SD to establish an accredited Doctorate in Theology (Th.D.). The Th.D. is a research degree, preparing candidates for deep theological reflection, discussion, writing, leadership in the church and service towards the community. The goal of the program is to develop leaders in the Lutheran church who are qualified to teach in institutions across the globe, to engage in theological and biblical research to further the preaching of the gospel of Jesus Christ, and to respond with faithfulness to any calling within the church. Those who are accepted into and

complete the program will receive all instruction from SPLS professors and will receive an accredited (ATS) degree from Kairos University.

The general area of study of the Th.D. program is in systematic theology. Specializations offered within the degree include, but are not limited to: Reformation studies, evangelical homiletics, and law and gospel dialectics. The sub-disciplines within the areas of specialization are dependent upon the interest of the student provided they have a qualified and approved mentor. Other general areas of study, such as biblical studies, will be forthcoming. For the full description of the program, go to https://semlc.org/academic-programs/ If you are interested in supporting our effort to produce faithful teachers of Christ’s church, contact Jon Jensen jjensen@semlc.org. All prospective student inquiries can be directed to Dr. Marney Fritts mfritts@semlc.org.

Giving - Please consider making a generous contribution to St. Paul Lutheran Seminary at: https://semlc.org/support-st-paul-lutheran-seminary/.

I hope you enjoy this issue of SIMUL! If you have any questions about the journal or about St. Paul Lutheran Seminary, please shoot me an email at dennisdimauro@yahoo.com

CALLED TO FAITH

Julie Smith

These days I spend more time than I would have anticipated in churches that are having some sort of trouble, or with pastors who are having some sort of trouble. Sometimes those two things are connected. Sometimes they are not. I also spend a lot of time with churches that are looking for a pastor and have a lot of conversations with pastors who are looking for a church. As I go about this work, there are a couple of recurring themes that I find troubling. One is that a lot of churches do not respect the pastoral office. The other is that a lot of pastors do not respect the pastoral office. In particular, the office is not respected as a calling. That might manifest itself in congregations not seeing much value in having a properly trained pastor. It might also be demonstrated by pastors who think ministry is a career choice, and a particular call is one they will take or leave based on compensation or proximity to Target.

I don’t imagine that we will get to the bottom of that in our time together this week, but hopefully we will start to peel back some of the layers. Then maybe we will stop imagining that our present “clergy shortage” is something that is going to be solved with a clever program from a seminary or church headquarters. Rather, it will take a shift in the attitudes and expectations of all of us who have been called into Christ’s church. I’m not talking about adopting an authoritarian view in which everyone defers

to the almighty pastor. I’m talking about remembering that the office of pastor is a holy calling and ought to be recognized as such, including by those who occupy that office.

I’m going to look at two aspects of the call to pastoral ministry. In this first session, we will hear the call to faith that is built into pretty much every call story we find in scripture. Tomorrow, we will consider the call to go, and our understanding that this is an itinerant vocation. So first, let’s take a look at some call stories of biblical figures, none of whom were actually called to pastoral ministry as we now practice it. And as you listen to these stories, if you find yourself thinking, “wait, she’s leaving out some important stuff,” we will get to that tomorrow.

Abram – Even When It Seems Impossible

If you have a Bible with you and like to follow along, please turn to Genesis 12:1-3. We will start with the call of Abraham, and the call to faith even when it seems impossible. “Now the LORD said to Abram, “. . . I will make of you a great nation, and I will bless you, and make your name great, so that you will be a blessing. I will bless those who bless you, and the one who curses you I will curse; and in you all the families of the earth shall be blessed.”1

I’m talking about remembering that the office of pastor is a holy calling and ought to be recognized as such, including by those who occupy that office.

The call of Abram kind of comes out of nowhere in Genesis. Everything before it is what biblical scholars refer to as “prehistory.” We get a lineage from Noah’s son Shem that finally arrives at Abram, son of Terah. But in the generations since

God scattered the people after the tower of Babel fiasco; we have no stories of God interacting with the people between Shem and Abram. All we’ve got is a lineage. And then one day the Lord speaks to Abram, a relationship that leads to the great covenant that defines the Old Testament.

And the Lord makes a promise to this childless husband of a barren wife. “I will make of you a great nation.” At this point in his life, maybe Abram hoped he would die rich, and his nephew would be his heir. But as it stood, perhaps he would be remembered for one generation. As a childless person, this might be a little projection on my part. But the possibility that he would be the father of a great nation couldn’t really have been on his radar at this point.

In the list of things that are possible and things that are not possible, this falls squarely in the “not possible” category. A man with no sons can’t hope for something like this. But it’s into this moment, this circumstance in Abram’s life, that the Lord arrives with a promise. “I’m going to make of you a great nation. And not only that, in you all the nations of the earth will be blessed.” The Lord’s work in the world is going to be attached to Abram and his descendants.

The easiest response in the world to such a promise would be, “that seems unlikely.” Because it’s not something that Abram’s will or effort can possibly accomplish. That’s the trick to this whole business. It’s going to be the Lord’s work, carried out through Abram. And any time Abram or Sarai try to take that work into their own hands, things go awry. We see that with the Hagar episode. We see it when Abraham decides to protect Sarah by saying she is his sister, only to see her

married off to another in Egypt.

The call of Abram is, first and foremost, a call for him to trust in the one who is calling. Trust in the one who has a mission he is carrying out in the world. And trust that he can accomplish what we cannot. This is an important thing for a pastor and a congregation to remember. God’s mission in the world is possible, even when it looks impossible to us. He is carrying it out in and through us, in spite of all evidence that we are barren and hopeless.

Moses – Even When We Are Afraid

For our second call story, we’re going flip to Exodus and the call of Moses, who was called in spite of his fear.

“Moses was keeping the flock of his fatherin-law Jethro, the priest of Midian; he led his flock beyond the wilderness, and came to Horeb, the mountain of God. There the angel of the LORD appeared to him in a flame of fire out of a bush; he looked, and the bush was blazing, yet it was not consumed. Then Moses said, “I must turn aside and look at this great sight, and see why the bush is not burned up.” When the LORD saw that he had turned aside to see, God called to him out of the bush, “Moses, Moses!” And he said, “Here I am.” Then he said, “Come no closer! Remove the sandals from your feet, for Moses

the place on which you are standing is holy ground.” He said further, “I am the God of your father, the God of Abraham, the God of Isaac, and the God of Jacob.” And Moses hid his face, for he was afraid to look at God. Then the LORD said, “I have observed the misery of my people who are in Egypt; I have heard their cry on account of their taskmasters. Indeed, I know their sufferings, and I have come down to deliver them from the Egyptians, and to bring them up out of that land to a good and broad land, a land flowing with milk and honey, to the country of the Canaanites, the Hittites, the Amorites, the Perizzites, the Hivites, and the Jebusites. The cry of the Israelites has now come to me; I have also seen how the Egyptians oppress them” (Exodus 3:1-9).

Most of us probably remember the burning bush story. We remember the command to Moses to remove the sandals from his feet because he was standing on holy ground. I had forgotten the line that Moses was afraid to look at God. Of course, that’s a recurring theme in the Old Testament, but somehow, I had forgotten all about it.

Moses has had a rather complicated life up to this point. Pharaoh had attempted to kill him and all the other Hebrew baby boys. His mother, his sister, even Pharaoh’s own daughter had been enlisted by the Lord to intervene on Moses’ behalf. He’d been raised as an Egyptian but had some sense of his Hebrew roots. But now he was a man without a people, having fled Egypt in fear for his life.

And then the Lord, who had been active in his life every

step of the way, makes himself known to Moses, appearing to him in a way he had never appeared before. Moses is understandably afraid. He’s afraid of what he’s seeing―afraid of what might be expected of him. He thought he was safe out there shepherding his father-in-law’s flocks. I find myself picturing those movies that begin with our action hero having retired to a quiet life somewhere far from the action, only to be called back into service once more.

Moses had gotten himself out of the mix. He had escaped from his complicated life in Egypt. He had escaped from the consequences of killing an Egyptian. But now the one who had been quietly in the background his entire life moved front and center after hearing a divine call. But Moses was afraid. He was afraid to face the God of his fathers―afraid of what might lie ahead for him.

When the Lord calls us, he doesn’t call us to what will make us comfortable. He doesn’t say, “well . . . I know that would be hard for you, so I’ll find something else for you.” Often, he calls us right into the heart of our fears. Thirty-one years ago, I was very reluctant to apply to seminary because the idea of public speaking made me sick. The call to ministry is a call to the faith that overcomes fears. It’s the call to faith that trusts the Lord to be our strength when our hands, our knees, our voices are shaking.

Jonah – Even When We Don’t Like the Mission

It would be a shame to talk about biblical call stories and

leave out one of the best ones ―the call of Jonah, who was called even though he didn’t like the mission to which he was called. “Now the word of the LORD came to Jonah son of Amittai, saying, ‘Go at once to Nineveh, that great city, and cry out against it; for their wickedness has come up before me.’ But Jonah set out to flee to Tarshish from the presence of the LORD. He went down to Joppa and found a ship going to Tarshish; so he paid his fare and went on board, to go with them to Tarshish, away from the presence of the LORD” (Jonah 1:1-3).

Jonah wasn’t afraid of the Lord, and he didn’t think what the Lord had in mind was impossible. It was quite the opposite. He was entirely convinced that what the Lord had in mind would be accomplished. And he didn’t like it. He didn’t agree with God’s plan to save the people of Nineveh. He wanted them to suffer. And he certainly wanted no part in working on their behalf.

Faith is not only trusting that God can do things. It is trusting that what God wills to do is right, righteous. It is being conformed to God’s will, when God refuses to be conformed to ours. It’s one thing to be called to deliver a word to people you care about, people you want to be saved. But to trust that God knows who needs saving and has a plan to accomplish it, even if you’re entirely sure that the ones God is concerned about are not worthy of his concern, that’s rough. That’s not a calling that many of us would have been any more eager than Jonah to receive.

It’s one of the most miraculous aspects of the Bible, I think. That it bears witness again and again and again to the reality

that God’s beloved people, his chosen ones, just think he is wrong so much of the time. This is the heart of our original sin, and the Bible does not make even the slightest attempt to hide the depths of it. Again and again, we see people who should be pillars of faith, who should be examples for us to follow, instead actively defying God’s will, and just saying “nope” to his commands.

Faithfulness in ministry means trusting that God knows what he’s doing. Trusting that especially when we don’t like it.

Faithfulness in ministry means trusting that God knows what he’s doing. Trusting that especially when we don’t like it. When we find ourselves thinking, “why did the Spirit gather these particularly heinous sinners into the flock that I’m now called to shepherd?! Why couldn’t he have just given me a nice congregation that practices great stewardship, great hospitality, great service, is attentive to worship, and overflows with Christ’s love in every possible way?! But nope, I got a bunch of sinners. Sinners who don’t fully appreciate how lucky they are to have me as their pastor.” Tarshish looks better and better all the time!

Sunday Schools and Bible camps have lots of fun with the story of Jonah. It’s simply brilliant on many levels. But right at the center of it all is the decidedly not fun reality that God’s servants – you and I – have a deeply ingrained instinct to second guess him, to go our own direction in defiance of his call. And that’s really not a laughing matter.

Peter – Even When We Are Fickle

Now let’s switch to the New Testament, and we’ll start with

Christ’s call even when we are fickle, as seen in Peter’s confession in Matthew 16. As a general rule, I’m not a huge fan of Peter. The Peter we meet in the gospels is just a little too brash, a little too quick with an answer, a little too quick to put himself forward. And the Peter we meet in Paul’s letter to the Galatians is a much bigger problem than any of that. Those traits that are just kind of annoying in the gospels are deeply problematic once Peter is out there at work in the church. And yet, listen to his conversation with Jesus in Matthew 16:13-17.

“Now when Jesus came into the district of Caesarea Philippi, he asked his disciples, “Who do people say that the Son of Man is?” And they said, “Some say John the Baptist, but others Elijah, and still others Jeremiah or one of the prophets.” He said to them, “But who do you say that I am?” Simon Peter answered, “You are the Messiah, the Son of the living God.” And Jesus answered him, “Blessed are you, Simon son of Jonah! For flesh and blood has not revealed this to you, but my Father in heaven.”

In a moment driven completely by divine intervention, Peter is right on the mark in his response to the central question of the day. Just who is this Jesus? Peter knows the answer. Because it has been revealed to him, not with his own eyes, but through the power of God. For one moment, Peter got out of his own way and the truth was revealed through him. And upon this confession of faith Christ makes an astounding promise in v. 18, “And I tell you, you are Peter, and on this rock

I will build my church, and the gates of Hades will not prevail against it. I will give you the keys of the kingdom of heaven, and whatever you bind on earth will be bound in heaven, and whatever you loose on earth will be loosed in heaven.”

This faith that Peter so boldly, almost unconsciously, proclaims, is that Jesus is the Christ, the Son of the Living God, upon whom the church will be built. And nothing, not even the gates of Hades, will be able to overcome it. What a huge moment! What a powerful witness to Jesus! Peter must be so proud of himself!!

But, of course, we know how things go with Peter. He will do something amazing one moment, in the grip of the Holy Spirit. And the next minute, his ego, or his need to be liked, or even the devil himself will get ahold of him, and he will set himself up against Christ and his Gospel. He will tell Jesus he can’t possibly go to Jerusalem to die. He will break bread with the Gentiles in Antioch, as long as no one is around to see it, and then back off when powerful leaders from Jerusalem arrive on the scene.

Constancy is not one of Peter’s gifts. But Christ Jesus puts him to work in spite of himself. He gives him the Word when he needs it, even when Peter’s own words and actions are in conflict with the word he’s been given to proclaim. Can you imagine it? A leader in the church who is not perfectly consistent? One who sometimes caves to the pressure of those she wants to impress? One who doesn’t always want to go all the way to the mat for his convictions, but would like to find a middle way, a painless

Constancy is not one of Peter’s gifts. But Christ Jesus puts him to work in spite of himself.

way? One who loves to be loved?

Christ Jesus calls us out of ourselves into the faithfulness where he is the center, not us. The faithfulness that means death to the self in favor of life in Christ. If all we’ve got is our own capacity to keep people happy, we will quickly realize our limits, our hypocrisy, our desperation. We won’t survive it. But that’s ok. Because our death is precisely what such a situation requires, in order that faith might come to life.

And finally, we will consider God’s call of those who have simply been wrong, about him, about themselves, about life, about death. We will consider the call of Paul.

Paul – Even When We’ve Been Wrong

We will let Paul tell his own story, rather than the story Luke provides in the Book of Acts. In Galatians 1 we hear Paul describe his former life. “You have heard, no doubt, of my earlier life in Judaism. I was violently persecuting the church of God and was trying to destroy it. I advanced in Judaism beyond many among my people of the same age, for I was far more zealous for the traditions of my ancestors” (Gal. 1:13-14).

Paul had everything figured out. He was a rising star. He had impressed the right people, was making all the right moves. He was making a name for himself. And in his day that required a specific focus. There was this movement afoot of those who were following an allegedly false messiah. They were gaining momentum in Jerusalem, in Damascus, and in a variety of other places. Paul knew with certainty that his responsibility was to stop this movement―at any cost. He violently

persecuted the church of God because he was convinced that that was what he was supposed to do.

Until one day he was called to be a witness to this same Jesus he had been trying to destroy. That’s a bit of whiplash. To be certain you have to destroy something, and then be equally certain you are called to serve what you were trying to destroy. Paul would have had no reason to think anyone would listen to him—no reason to think anyone would trust him. The easy solution would have been to say, “Okay, I’ll stop persecuting the church. I’ll shut up. I’ll maybe even become an active member of a congregation somewhere. But it makes no sense at all to imagine I have some sort of particular calling to serve this church I’ve been trying to destroy.”

And yet, he did. There was no way around it. The Spirit grabbed hold of Paul, and the rest is history. It turns out that God doesn’t only call those who have the correct resume. He doesn’t only call those who have no missteps, no ugly incidents in their background. He actually turns people around and makes them new. He did that with Paul. He can do that with anyone he chooses to―even you.

Summary

The call to the office of ministry is first and foremost a call to faith because pretty much everything we do is an act of faith. We stand up in front of a congregation and deliver the gospel trusting God’s Word that that is how he has decided to redeem sinners. We He actually turns people around and makes them new. He did that with Paul. He can do that with anyone he chooses to―even you.

stand there and talk believing that this is God’s saving work. We visit the homebound, bringing a word of hope when hope seems foolish or naïve. We stand at hospital beds and gravesides announcing Christ’s defeat of death. We sit in council meetings understanding that even this tedious discussion of the budget is part of the work of Christ’s church, through which the lost are being found. We baptize children whose parents we’ve never seen before, with faith that Christ’s word accomplishes what it says, hoping against hope that, even if we don’t ever see it, the Holy Spirit is bearing fruit in that young life.

The entire enterprise is an act of faith, from beginning to end. It’s when we imagine it as our work and not the Lord’s that we start to find ourselves in trouble. Like when Abraham tried to find an alternate route to a family, or when Moses thought he could hide in the wilderness and forget about his people, or when Jonah thought he could thwart God’s will to save the Ninevites. We even see this attitude in the apostles, when Peter put his own reputation ahead of what he knew to be true and when Paul was convinced that Jesus needed to be stopped. It happens in all those times when our own agenda moves to the center and the Lord’s will gets shunted off to the side―that’s when things go awry.

But God is not so easily thwarted. Our best efforts for the last 2000 years, and Israel’s best efforts for a couple thousand years before that, could not stop God’s will from being done. He’s quite good at being God. He’s been at it a long time. In the face of our faithlessness and doubt, he just keeps calling us back, seeking us out, setting us on the right path. And the amazing blessing of the office of ministry is getting to be a part

of that mission.

Rev. Julie Smith is the service coordinator for Lutheran Congregations in Mission for Christ (LCMC), and she teaches at St. Paul Lutheran Seminary.

Endnotes:

1The Holy Bible: New Revised Standard Version (Nashville, Tennessee: Thomas Nelson Publishers, 1989), Gen. 12:1–3. All subsequent Bible citations in this essay are from the NRSV translation.

CALLED TO GO

Julie Smith

When I went to seminary, the system was very clear and mostly unmoving. You moved to a residential campus where you spent two years taking full-time classes. Then you moved to an internship site. Then you moved back for one more year of classes. In the middle of that final year, you were assigned to a synod for your first call. At that time, you were paid about $10,000 a year for that. Adjusted for inflation that would be just under $20,000 a year today.

There were two moments over the course of those four years when a student got to state some preferences. You could make some requests concerning about internship – what type of church you were interested in, and in what part of the country. Every year a number of Luther Seminary students would restrict themselves to the Twin Cities for internship. But they had to be able to demonstrate that moving again was an insurmountable hardship for their families. At least that was the stated requirement. The reality was that if there were a pastor in the Twin Cities who wanted that student as his intern, he could flex his muscles and make it happen.

Students were also allowed to list their top three choices for synodical assignment. Again, there was some opportunity to restrict oneself to certain synods, but this was a little more difficult to pull off in the call draft than it was for an internship

assignment.

In both of these moments when students got to express some preferences, it was understood that no internship sites and no bishops were obligated to honor their preferences. In the end, you would go where the church sent you, or you would be looking for some other type of work while you waited for a call to open up and a bishop who was willing to submit your name for it. It was clear who held the cards in this process.

This was, by no means, a perfect system. It was primed for all sorts of abuse and cronyism. But there was one thing that this system did very, very well. It taught you, from the moment you began your theological education, that you should expect to move. You should not expect that you were going to settle in somewhere and stay there. You should not expect that your children would graduate from the same school district in which they went to kindergarten. You should expect that you might never buy a house, moving from parsonage to parsonage, or that you might buy many houses in markets where it might be difficult to sell them very quickly when it was time to move. There were always pastors whose lives were exceptions to this general rule. But they were exceptions. There was an understanding that no one was entitled to these exceptions. There was an understanding that pastoral ministry was a calling of the church, and the church exercised authority over

But there was one thing that this system did very, very well. It taught you, from the moment you began your theological education, that you should expect to move.

it.

I've been involved with online theological education for many years now. One of the things I have worried about in relation to this form of education is that it can instill a sense that theological education and the pastoral vocation are matters of personal convenience. Apart from the classwork itself there shouldn't be any hardship involved with becoming a pastor. All impediments or barriers to entry should be removed, if possible, so that anyone who feels called to be a pastor can become one. The danger with this is that we end up with people who are trained to be pastors but cannot or will not move from their current location. Rather than this being the exception because of unusual circumstances, it has become the rule. Many pastoral candidates simply do not consider this to be an itinerant vocation.

Somewhere between a system that seeks to exert ownership over pastoral candidates and one in which pastoral candidates feel little to no sense of obligation to their church body there lives a third way. A way in which candidates understand what's involved in this calling while congregations and church bodies respect the challenges that pastoral candidates face. This is especially necessary as many seminary students are second and third career students. Their spouses might be established in a career that makes it difficult for them to relocate. They may have children and grandchildren that need them to stay in a particular location.

Today we're going to return to the call stories that we looked at yesterday. While yesterday we focused on how this was first and foremost a call to faith and trust in the living God and his mission in the world, today we will focus on how each

of these callings included the need to go. Every one of the people God called in these ways was sent somewhere by this calling. We will begin with Abraham.

Abraham – Away from Home

Now the LORD said to Abram, “Go from your country and your kindred and your father’s house to the land that I will show you. I will make of you a great nation, and I will bless you, and make your name great, so that you will be a blessing. I will bless those who bless you, and the one who curses you I will curse; and in you all the families of the earth shall be blessed.” The Lord's very first word to Abraham was “go.” With no prior introduction, Abraham was called away from his father and his family and everyone he knew. The mission and the promise God had in store for him were going to take place somewhere new. And not only somewhere new but in a place that hadn't even been identified yet. Abraham was just told to go with the promise that he would find out the destination along the way.

Despite the tremendous promise attached to Abraham's call―that he would be the father of a great nation, that his name would be great, and that through him all the nations of the earth would be blessed—it's not that difficult to imagine Abraham objecting to this call. Why did it require leaving everything he knew? Why couldn't God give his family the land of Haran as their promised land? Didn’t the Lord understand how important Abraham’s country, kindred, and father’s house

were to him?

But Abraham doesn’t object at all. The Lord says go, and without a single question or comment, Abraham goes. The questions and comments will certainly come later. But in this moment, when he receives this call, he goes. He leaves behind everything that defined him―country, kindred, father—in favor of something new that will define him and will define him more deeply than anything else ever had or could.

Can we imagine such a thing? Can we imagine such openness to getting up and going, leaving behind everything that is familiar? I know there are some people in this room who have made big moves, away from family and friends, away from support networks, away from the known. That came with sacrifice, perhaps with some arguments at the dining room table and some tears shed. But that also seems to be increasingly rare.

The question I am most likely to get when I’m out on the road is whether we have enough pastors and what we’re doing to solve the problem. For a while I flipped that question back around to congregations, asking them when the last time was that they sent someone to seminary. Then I decided even that was a bit too abstract, a bit too easily dismissed as someone else’s responsibility. So now I ask if they would encourage their children or grandchildren to become a pastor. Folks are pretty quick to change the subject at that point.

But one day the guy who had asked the question had an answer for me. He would not encourage his children or grandchildren to become a pastor because he didn’t want them to move away, and he didn’t want them to miss family

holidays. On the one hand, there is something refreshingly honest about that. On the other hand, it is truly appalling.

On the one hand, there is something refreshingly honest about that. On the other hand, it is truly appalling.

Here's someone who’s engaged enough in the life of his congregation that he has stuck around after worship for a forum on denominational affiliation: someone who has some sense of the difference a faithful pastor can make in the life of a congregation. But this person is also crystal clear that it is more important that the family all be gathered around the tree to open Christmas presents. I wish I had another crack at him and could let him know what, perhaps, most of the people in this room know. That Christmas dinner tastes just as good on New Year’s Eve or the Saturday between Christmas and New Year’s, or sometime in January. That the gift buying is actually cheaper if it happens after December 25. That family traditions can be changed, trips can be made. That working weekends can get you out of a lot of things you’d like to say no to anyway. That it is possible to adjust.

The pressure to stay put is no small thing. It’s part of what makes online theological education so appealing to people. But we may need to at least consider the possibility that this isn’t about our convenience. Last night, we were having a discussion about how we could facilitate getting more of our students to this event, which I think would be great. So, we were talking about finding ways to subsidize their travel, in addition to subsidizing their registration and housing costs. The seminary administrator in me loves that idea. I’m pretty

much a pushover when it comes to students and I want us to do what we can to provide them with learning opportunities and a deeper sense of community. The church bureaucrat, on the other hand, wants to say, “Just make it a graduation requirement. Make them get some skin in the game. A threeday trip is nothing compared to being required to move three or four times to get through seminary!” But we also know from the long history of the church that just adding requirements does not automatically weed out those who aren’t sufficiently committed to the pastoral vocation. It does, however, weed out those who have unusual circumstances to deal with. The challenge of the moment, it seems to me in my entirely unscientific survey of the landscape, is that almost everyone thinks that their circumstances are unusual and ought to be given special consideration. Almost everyone can give a compelling and heartfelt reason for why their call to pastoral ministry does not include a call to “go.”

Moses certainly wasn’t looking for a call to “go.” But he ended up being on the move for the rest of his life, without ever actually arriving.

Moses – Back to Where You Came From

When Moses fled from Egypt it seems likely that he never planned to go back there. He had severed the connection with his Egyptian family, and it was his fellow Hebrews who had accused him of murder when he rose to their defense. Moses left and started a new life in Midian. He got married and settled down and went to work for his father-in-law. His life

was finally starting to look somewhat ordinary. Egypt was becoming a memory – a vivid and complicated memory, but still a memory.

And then he stumbled upon the burning bush, and he heard the voice of the Lord. While Moses had been trying to forget and move on from his life in Egypt, the Lord had remembered his people in Egypt. The Lord was about to do a new thing for the Israelites. He was about to rescue a people who thought he had forgotten about them entirely. And he was going to use Moses to carry out his plan. Moses would have to go back to Egypt. Sometimes the call of the Lord sends you back to where you came from.

I grew up in a town of 1400 people in southwestern Minnesota. Like most of the rural areas in the United States it has experienced what is referred to as “brain drain.” Basically, if you leave town to go to college you don't come back again. The assumption often built into that is that these places are uninteresting and not suitable for people who have pursued higher education. They are not places you'd want to live if you could live somewhere else. In fact, my college advisor called me into his office my senior year to let me know that his biggest concern was that I didn't have a plan and I might end up back in my small hometown. As far as he could tell this would be a total waste of a good education. I did my seminary internship in a town of 150 people. It was a rough town with rough people. But I was a small-town person, so I knew how to live there. For my first call I moved to

a town of 1000 people. It was exactly the kind of town I had moved away from to go to college. In fact, it was in the same high school sports conference as my hometown. And for the rest of my working life, I have been in towns of fewer than 2500 people.

There are times when the small town thinking that says “if you can move away you do,” creeps into my mind. And I wonder about the places I have served. Are they the places I should have served? Or was there something bigger and better out there that I just didn't pursue? When that thinking creeps in it undermines the work I’ve done in those communities and those congregations. It suggests that my time there was of no value or at least not much value.

I suspect if you were to look at the call histories of most pastors, the movement is from small town to large town. And why wouldn't it be? As you gain more experience you move up the ladder. And every assumption in our culture is that moving up the ladder means moving to bigger and better things: better pay, in better towns, in better churches. The idea that you might ever be called to go backwards hardly makes sense to us. That is surely a sign of failure.

But the people in that town of 150 people had no less need for the gospel of Jesus Christ than the people in the largest church in our association. And while the work done there might look different, it's no less challenging than the work done somewhere bigger and allegedly better. When God calls us, he calls us to go where he needs us to be. He calls us to go where there are people who need his word. And sometimes that means going to exactly the kind of place we've just left—

the kind of place we never thought we would return to.

That was my call. That’s certainly not everyone’s call. It may not be your call. But if it is your call, drive out those voices that would tell you that’s failure. Drive out the voices that would claim you’re going the wrong direction if you’re not constantly going up. And rejoice in the fact that when you are called back to the sort of place you thought you had left forever, you have an advantage. You understand the culture as only an insider can. You know where the landmines are.

Drive out the voices that would claim you’re going the wrong direction if you’re not constantly going up.

Just as a silly little example of that, I have now moved to a metropolis of 12,000 people and I no longer have a parish. In fact, I only know a couple of people in town. And when it came time to replace my car, for the first time in my life, I bought a foreign car. Because somewhere deep in my memory was my father’s observation that only teachers and pastors drove foreign cars. In a small town, a foreign car was a sure sign that you were an outsider: a completely unnecessary wedge between you and the people you serve. With so many other wedges between pastors and parishioners it was no sacrifice to never let the car I drove be one of them.

To serve in a place that doesn’t require a lot of cultural translation can be a real joy. As long as those voices that tell you “I’ve moved on from all of that,” don’t overtake you.

Of course, sometimes there’s another reason not to go where the Lord is calling you. It’s not that you’ve left a place behind with no plans to return. It’s that, like Jonah, you just can’t stand the people living there.

Jonah – Where You Don’t Want to Go

Why on earth would the Lord want one of his prophets to go to Nineveh?! There were plenty of issues to deal with right at home. There were plenty of the Lord’s own people who needed to hear his word. Why would energy need to be wasted on enemies, foreigners?

Jonah was not even a little bit subtle about his objection to the Lord’s plans for Nineveh and the part he was expected to play in those plans. In Jonah’s mind, the Lord had no business saving Nineveh and it was completely unreasonable to expect Jonah to be part of that effort. His attempts to thwart God’s plans are comical. And God’s intervention is a clear reminder of just who was (and is) in charge here.

We’re a little loose these days with terms like “enemies.” We don’t bat an eye at calling members of an opposing political party “enemies.” We imagine people lined up against us, trying to destroy us and everything we hold dear. And they imagine the same about us. Neither of us usually stops to consider that the others are just people going about their business, trying to live their lives, just like we are.

The Ninevites were political enemies of Israel to be sure. But the people of Nineveh weren’t sitting around trying to figure out how to destroy God’s people. They were living their lives. But even if they didn’t belong to the nation of Israel, they belonged to God, as the whole creation belongs to God. Their well-being was of concern to him.

In our current culture wars, it is all too easy to imagine that God is on my side and is against anyone I’m against. God cares

about who I care about. God wants to redeem those I think worthy of redemption. God loves those I love. But our God is the God of the universe. The Creator of all that is. All of this belongs to him. And he seeks to know and be known by all those he has made.

All this means that you may be called to go to places you would just rather not go―to live and serve among people who are not your people. These are people whose values do not match your own, people whose voting record appalls you, people you have nothing in common with. You might think that these people aren’t worth your time and effort. And yet, there you are, sent to deliver a word to them.

A pastor friend of mine in India tells the story of going to a remote village on an evangelism trip. They were met by the local medicine man who wanted nothing to do with them and would not let them enter the village. As they turned to leave, Pr. Duggi felt something nip at his ankle. He woke up days later in the hospital, having been shot with a poisoned dart by the medicine man.

All this means that you may be called to go to places you would just rather not go―to live and serve among people who are not your people.

Most of us do not experience quite that level of resistance to our proclamation of the gospel. People who don’t like the changes we’ve made to the worship service or the confirmation program might feel like poison darts from time to time, but we will probably survive that opposition. On the other hand, our call to a particular congregation might not survive that opposition if we insist on dying on every hill.

But wherever we are sent, there is one thing that is certain. The people in front of us are people for whom Christ died,

even if we can’t figure out why. We don’t have to figure that out. And we don’t have to like it. But like Jonah, we have to deliver the message, even if we’re secretly hoping they’re not listening. Luckily for us, the Holy Spirit takes over from there.

Peter – Back and Forth

In some ways, Peter had the trickiest of all the calls we’ve been talking about. Because he was called to go back and forth between two communities. On the one hand, there were the Jews, his people, the people he knew and loved, the people he understood and could relate to. And on the other hand, there were the Gentiles, people who had always been seen as “other,” but whom Christ had now brought into the fold.

Peter had to find ways to speak to both of these groups. And he wasn’t always very good at it. The temptation he had was to preach a different gospel to these two different groups, to tell each what they wanted to hear. This was different than what Paul meant when he talked about being all things to all people. It seems that Peter waffled a bit on how Christians were expected to relate to the law. Or maybe, and perhaps more accurately, Peter worried about offending either of the two groups he ministered to. And this fear of offending, which may have reflected a fear of being cast out by either group, started to control Peter’s witness―at least that’s what it looked like from Paul’s perspective.

So rather than being laser focused on what lies at the heart of the gospel and then finding ways to speak that truth into the experiences of Jews and Gentiles, he offered a slightly

different gospel to each, which, in the end, meant no gospel at all. In the end, a compromised gospel can only undermine faith. It can never grant or feed true faith.

To be called to go back and forth between diverse communities, with different expectations and different assumptions, can easily cause us to get tripped up and forget what the main thing is. We can get so focused on what they want that we forget that we all need the same thing. We all need the unconditional promise of the gospel, uncompromised by our cultural assumptions, and unedited by our preferences or traditions.

We are called to be all things to all people, to go back and forth between all sorts of different cultures. And that requires knowing different languages, different preferences, different styles. It requires using different examples, even behaving in different ways. But it cannot, it must not, mean changing the message to suit the tastes of those before us, no matter how deeply held their convictions may be.

It is one thing to wear vestments because that is the expectation of the people in front of you. It is something else entirely to affirm a conviction that there can be no proper worship without vested clergy. It is one thing to do all the communion visits because that is the tradition of the congregation. It is something else entirely to agree that the sacrament is only valid if it comes from your hand.

It is one thing to wear vestments because that is the expectation of the people in front of you. It is something else entirely to affirm a conviction that there can be no proper worship without vested clergy.

Understanding the needs and expectations of your congregation when they don’t match your own requires constant discernment. It means constantly asking, “now why am I doing this? Why am I saying this?” And it’s quite easy to get it wrong. But that doesn’t relieve us of the call to go to those whose traditions, whose expectations, and whose fiercely held beliefs, have to be challenged from time to time.

Paul – Wherever the Holy Spirit Sends You, Even to Death

Abraham’s call was to a specific, but not yet revealed, destination. Paul’s was a little different. He was called to go wherever the Spirit sent him. There was not a specific destination in mind. He might have had a rough outline of his missionary journeys, but they were pretty open-ended. He would go wherever the Spirit drove him. There was only one thing about Paul’s journey that was clear. He was headed toward his death. He would not be retiring. He would not someday land at his permanent call where he would live out his days in peace. He was going to be preaching this gospel, without apology or compromise, until he finally ran into someone who had the authority to respond to the offense of the gospel with the power of the sword.

Some of us may indeed run into the power of the sword in opposition to the gospel. But that is not likely to be the story for most of us. But we will run into opposition―that is guaranteed. The gospel does offend people, and sinners do all kinds of sneaky things to undermine this word, and replace it with something else.

I hope you will consider the possibility that your call to ministry might take you to places you have not yet thought of. I hope your vision of the future possibilities in this office might be expanded. But if not, one thing is certain, the call to serve the gospel is a call to die to yourself and your plans and ambitions, only to be given a new life, new plans, and a new identity. Maybe you will go where you are called to go, maybe you won’t. But the life you now live is not your own. It never will be again. It is Christ in you. And he has a way of getting his will done even by those inclined to resist.

Conclusion

The call to faith and the call to go go hand in hand in the life of those called by God to be his witnesses. Faith without going is an abstraction. It’s faith that doesn’t cut to the heart of us, doesn’t break through our defenses and excuses. It’s faith kept at arm’s length. It’s faith that says all the right things while leaving you unchanged.

Faith without going is quite safe. Going without faith, on the other hand, is deadly. Going without faith is going in your own name, to a destination of your own choosing, for purposes of your own imagining. Going without faith results in building the kingdom of Julie, not serving in the kingdom of God.

Faith without going is quite safe. Going without faith, on the other hand, is deadly.

If we learn anything from the call stories we’ve been looking at this week, it’s that God can get his work done in spite of our efforts to thwart it. He can work through those of little faith or hope, and he can work through those who are reluctant to go.

Jonah, for all of his opposition, was the most successful prophet in the entire Old Testament. The people actually repented based on his half-hearted proclamation. And Isaiah’s beautiful 66 chapters had to be delivered, at least in part, to a defeated people in exile, but his prophecy gave the Israelites hope.

God can get his work done in spite of you. And he keeps calling extremely challenging people into the service of his mission. Perhaps one of these servants of God resonates more closely with your own story. Perhaps you see yourself in one of them, for better or worse. Or maybe your story is more like the life of Isaiah, Deborah, Gideon, Mary Magdalene, Thomas, or Hosea. Whatever your story is, there are two certainties –you’re part of it and God is part of it.

Maybe you want to toss yourself into the sea in response to this calling. Maybe you’re eager to go, but just not where you’re needed. Maybe this call will be the death of you. Maybe there will be days you love and days you would rather be doing anything else . . . if only you could. But in any and all of these circumstances, the Lord is making a way. He is getting his work done. So maybe it’s time for you, servants of God, to just give up the fight. Resistance is futile.

Just listen to how Paul, whose calling would be the death of him, described it in Romans 1. “First, I thank my God through Jesus Christ for all of you, because your faith is proclaimed throughout the world. For God, whom I serve with my spirit by announcing the gospel of his Son, is my witness that without ceasing I remember you always in my prayers, asking that by God’s will I may somehow at last succeed in coming to you. For I am longing to see you so that I may share with you

some spiritual gift to strengthen you or rather so that we may be mutually encouraged by each other’s faith, both yours and mine. I want you to know, brothers and sisters, that I have often intended to come to you (but thus far have been prevented), in order that I may reap some harvest among you as I have among the rest of the Gentiles. I am a debtor both to Greeks and to barbarians, both to the wise and to the foolish —hence my eagerness to proclaim the gospel to you also who are in Rome” (Romans 1:8-15).

As seen in Paul’s words above, this sharing of the gospel is not just something you are obligated to do for others. It is also mutually encouraging. The same church that frustrates and infuriates you will pick you up in your lowest moments. The same community that seems indifferent to the work you are engaged in will give you moments of profound joy.

The office of pastor is not easy. It’s not glory unto glory. It’s not always held in high esteem by the world around us. And yet, it is a tremendous gift and privilege to be called into this work. And when faith finally breaks through all of our agendas and we can see this work as God’s work to save, then we get to know not only the deep joy of the gospel, but also the profound satisfaction of living into our vocations. What a great combination.

Rev. Julie Smith is the service coordinator for Lutheran Congregations in Mission for Christ (LCMC), and she teaches at St. Paul Lutheran Seminary.

Endnotes:

1The Holy Bible: New Revised Standard Version (Nashville, Tennessee: Thomas Nelson Publishers, 1989), Gen. 12:1–3. The NRSV version is used throughout this essay.

VISITING FOR MISSION

Brad Hales

“No one wants to be visited anymore...people are too busy to be seen...individuals do not want their personal space violated...visitation is just paying the rent.” These are just a few of the pessimistic comments I have heard over the years about pastoral visitation. Unfortunately, church leaders and members do not always see the great benefits of visiting church members and other people in the community, however, the benefits are numerous. Visiting makes mission the central focus of the congregation, it builds relationships, it allows for the proclamation of the Word and the sharing of the Sacrament, it provides care, support and encouragement to church members, and finally, it sparks congregational renewal.

Scriptural Support for Visiting

Several examples of visitation can be found throughout Holy Scripture and the early Reformation church. In Genesis 18:1-15, the three-in-one God visits Abraham and Sarah to assure them that even in their advanced ages, they would be blessed with a child to continue the covenantal promise which the Lord had instituted. The angel Gabriel visits Mary in Luke 1:26-38, to announce that she would be the mother

of the Lord. In Matthew 9:35, scripture clearly tells us that Jesus went throughout all the cities and villages preaching, teaching, and healing. As a part of his visitation ministry, Jesus has an encounter with the tax collector, Zacchaeus, in Luke 19:1-10 and visits his home. In the final judgement account found in Matthew 25:36-40, we are reminded that when we visit the sick and those in prison, we are encountering Christ himself. And in Acts 15:36, Paul and Barnabas go back to visit the believers in every city where they had originally proclaimed the Gospel and planted the church.

Early Reformation Support for Visiting

Still another example of the power of visitation can be found in what was called the “Visitation to the Churches in Saxony.” Between 1528-1531, Luther visited all the congregations in Electoral Saxony to check on their “spiritual temperature.” But sadly, Luther was shocked at what he found. In the introduction to the Small Catechism he writes, “The deplorable, wretched deprivation that I recently encountered while I was a visitor has constrained and compelled me to prepare this catechism, or Christian doctrine, in such a brief, plain, and simple version.”1

The Bread and Butter of Parish Ministry

Pastoral visitation is the “bread and butter” of parish ministry. Along with sharing the sacraments, Lazarus Spengler

speaks about this important role of a minister when he writes that, “This [visiting obligation] is the same as their obligation to preach, comfort, absolve, help the poor, visit the sick, as often as these services are needed and demanded.”2

Both lay and pastoral visitation can be done in differing settings depending upon the need and other factors. Home visits provide an opportunity to minister to others in a personal, comfortable setting. There are very few professions where one is invited into someone’s personal space, but pastoring still affords that luxury.

But visits need not only take place in the home. Restaurants are often good places to connect with others over a meal or cup of coffee. Hospital visits are also vitally essential to check on a person’s health condition, and to offer encouragement in the face of difficulties. Offering prayers for strength and healing is usually welcomed in these encounters. Care facilities, such as nursing homes, assisted living communities, rehabs, and memory units all offer ample opportunities for pastors to visit those who suffer from serious health issues.

One of the most effective ways to reach out to those with memory issues is by having sing-a-longs with them. The part of the brain which is receptive to music continues intact for a longer period than the memory centers of the brain. I am amazed when I encounter older adults with Alzheimer’s disease, who can’t remember what they ate for breakfast, but who nevertheless can clearly belt out, “You Are My Sunshine” and “Jesus Loves Me.”

Workplace visits can also be effective but can be limited due to time or working conditions. However, meeting someone for

a coffee break or lunch may be beneficial, and a way to maximize a member’s time. During the COVID-19 pandemic, we quickly learned that outside/doorstep visits were essential in connecting with others, especially for combatting isolation and loneliness. Using devices has become a central aspect of our daily lives, and they can be used in the realm of visitation as well. Telephone/text/face-time visitations can offer instant encouragement, and a quick way to “check in.”

Community Visitation

But what about visiting folks outside of the church? Community visitation may seem unnecessary if we are just focused on connecting with “the flock.” And some falsely believe that if you are going to reach out to the community at large, it is done for the sole purpose of getting new visitors into the church. However, there are so many more benefits to community outreach. First of all, community outreach demonstrates that the parish wants to offer its services to the community. Second, community visiting is an opportunity to build relationships with others, especially non-believers. And third, community visiting opens the door to further ministry when needs arise. In his book entitled, Visiting in an Age of Mission, Kenyon Callahan speaks about visiting in the community when he writes, “God invites us to visit with persons in our community. We are not called to visit members only. We are invited to visit with community persons. The

term affirms that we live together in the same community. It affirms that our visiting has to do with more than getting people churched. To be sure, community people are not members of a church. They do not participate in the congregation. That is fine. They are people whom God has given us for mission. God encourages us to help them. As one wise, caring person once said, “We are put on this earth to help others.”3

Relationship Building

While there are various venues to facilitate visitation, what happens in the context of the visit itself will have long-lasting ramifications. One benefit of visiting is the building of relationships. Ministry is relational. In connecting with others, we have the privilege of developing our relationships with Christ, with other believers, and with non-believers. Visitation is evangelistic and has missional implications.

Pastor Dennis Di Mauro of Trinity Lutheran Church in Warrenton, Virginia, is an example of just such a relationship builder. When he visits several care facilities in his area every month, always playing his ukulele, he is not just visiting the residents. He has harvested intentional relationships with staff members and families, which have yielded numerous ministry opportunities. As relationships develop, ministry opportunities multiply. Care, concern, and encouragement are the main ingredients for visitation success. I once pastored a church where a long-time minister had retired after forty years of faithful work. While preaching wasn’t necessarily his forte,

his visitation and outreach efforts were legendary. Because of that focus, his Jesus-centered church grew and prospered. The intentional visiting of the homebound, those struggling, and periodically every member of the flock, will go a long way to pastoral success and longevity.

Visiting as a New Pastor and Dealing with Conflict

Perhaps one of the most beneficial times to visit is when a pastor first enters a new congregation. This is because when a pastor starts at a new congregation, there is a certain sense of uneasiness among the laity. And while there is some level of respect for the pastoral office, congregants are often uneasy in these early days because they suspect that a new pastor will immediately try to change things. On the day of installation at my current call, a couple of church members were heard saying, “This guy [new pastor] might make us do something.” So visiting members at the beginning helps prevent the sometimes-rampant speculation that the new shepherd is trying “to throw the baby out with the bath water.” In addition, it helps to strengthen trust, calm initial negative perceptions, and developing the needed support for future changes which might be required for the effective sharing of the Gospel.

Active visitation also helps with congregational conflict management. Now I realize that it is often easier to “sweep stuff under the rug” and not confront discord. But left unattended, these

On the day of installation at my current call, a couple of church members were heard saying, “This guy [new pastor] might make us do something.”

conflicts may “blow up” into crises that can threaten the very existence of the congregation. Jesus tells us in Matthew 18 that we are to go directly to the person that we have a conflict with and attempt to resolve the disagreement. But if this is unsuccessful, we might need to try again with the consultation of one or two others. During my visits I have also been informed about various incidents and conflicts, which have then assisted me in cutting things off at the pass. Visitation and conflict resolution go hand in hand.

The Cure of Souls

I remember one visit years ago in which an aging Lutheran told me, “I hope I go to heaven.” These words still make the hair on the back of my neck stand up straight, but during our visit I was able to ease her fears. I told her that in fact we are saved by grace through faith alone, and so we can know for sure that through faith, eternal life is ours.

Visitations also allow us to refute commonly held heresies and false teachings. This might include correcting the false belief that we must execute good works to be welcomed into heaven. We might also be called to council a parent whose adult child has been attending “new age” leadership retreats, where he or she is encouraged to keep paying more to become “enlightened.” Or we might have the opportunity to council an individual who has been “love bombed” into a cult and then mind-controlled into believing that his family and the generational church are his enemies. Visitation can shed light on these misconceptions, and many others, and allow us to share the true Christian faith.

Shut-ins

When the church visits, we bring the church to those who cannot attend. This is why sharing the sacrament is paramount in the congregation’s ministry. Along with providing the forgiving body and blood of our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ, we are literally connecting ourselves with those saints who have faithfully served their parishes for decades. They have the right to be remembered, to be nourished from the table, and to feel a part of the body of Christ. When I start working in a new congregation, the first visits I make are to the homebound, making sure that they receive Holy Communion. Visiting also includes responding to emergencies. When people are hurting, the church needs to be present. When grief support is needed, a congregation may want to start a Grief Share ministry, or even train Stephen ministers to help people navigate through loss.

When I start working in a new congregation, the first visits I make are to the homebound, making sure that they receive Holy Communion.

If a congregation is serious about renewing itself, then visiting can be a catalyst for that renewal. Renewing a congregation is like a puzzle. Different pieces of the puzzle are needed to create the picture. The puzzle pieces for renewal include a focus on prayer, on knowing the word, on evangelical worship, on confronting darkness, on outreach, on faithfully using our assets/gifts, and, of course, on visitation. By visiting, the vision of renewal can be cast. By visiting, excitement and enthusiasm can be shared. By visiting, existing connections are

strengthened and new connections are formed, and by visiting Jesus is continually exalted, as it is Christ who revives His Church.

In the community where I live, I have heard the story of a deceased Baptist pastor who was a teacher, coach, and a preacher. I am not sure where he found the time, but a significant part of his ministry was visiting. One of the phrases that he liked to repeat was, “If I go see them, they will come and see me.” Simply put, visitation can yield worship participation. While I have never seen a study to prove this proposition, it simply makes sense. When we endeavor to spend moments with individuals and families, Christ is present. And when people feel heard and cared for, the Holy Spirit is working in their hearts. If the Church believes that going out and seeing others is an integral aspect of its ministry, then those being visited will respond in kind. I cannot count the number of times that church members have told me I was the first pastor who had ever visited them. Aren’t we missing something by not visiting?

Visitation in the Community

Earlier in the article, we discussed the importance of community visitation. And it has been my experience that community connections and outreach bear much fruit. A couple of times a week, I have coffee or breakfast at one of the diners in town. I am usually there visiting with a church or community member. Through this simple ministry of presence, I cannot tell you all the contacts and relationships which have

developed. Through these encounters, prayer has commenced, souls have been soothed, faith is shared, and some are even moved to worship. And that happens just because I am present and available in the community. Whether it is in a diner, sitting on a local community board, being at a local festival, or attending a Friday Night football game, when we are out in the area visiting, the Spirit is providing us with “entry points” for the Gospel. Now, I realize that there are some churches that do not understand this. They think the pastor should attend to their needs only. But sadly, they do not comprehend that this is exactly what the clergy are called to do. They are called to be out in the community, sharing the Good News, and walking along side those also created in God’s image. Isn’t the New Testament always calling us out into the world?

Practical Tips for Visiting

This article has focused on various venues for visitation, and the multitude of benefits received in making these calls. But what might transpire during the encounter itself? Here are some things to consider. First of all, how long should a visit last? While this may be subjective, we certainly do not want to overstay our welcome. A home visit may last up to one hour, and a visit at a hospital or nursing home might hover around thirty minutes. Each situation is different, so use your best judgement. Listen more, talk less. Practice active listening, clarifying what is being said. Listening

A home visit may last up to one hour, and a visit at a hospital or nursing home might hover around thirty minutes.

is more than words, so be cognizant of your body language, tone, and facial expressions. During homebound visits we share information about the congregation and offer the sacrament of Holy Communion. While visiting, we should try to ascertain information about family members and neighbors, to see if there are needs that the church can respond to. Also, if an older adult speaks about someone taking care of his/her finances and personal needs, this may be a “red flag” for an elder abuse issue. Also, identifying things in the house is important. Are there smells? Are the dishes piling up in the sink? Is the individual shabbily dressed? Does there appear to be memory issues? At the end of the call, ask the person visited if there are any things that need to be reported or completed. Visits should end with prayer.

Include the Laity

While many visits within the church might be done in the context of pastoral work, a visitation ministry cannot be complete without the laity. They are the backbone of the church. A congregation will only function if the ministry of the laity is uplifted and expected. But what does lay visitation look like? First, we must identify those who are called and have a passion to connect with others. Second, equipping and training is essential, especially about the importance of confidentiality. Third, who will the visitors be accountable to? And fourth, who will be visited?

The need for lay visitation is huge, as the clergy cannot possibly attend to all the needs in the parish. Holy Scripture

provides a framework for this ministry. In Galatians 6:2 it is written “bear one another’s burdens and so fulfill the law of Christ.”4 And in I Thessalonians 5:11 it says, “Therefore encourage one another and build one another up, just as you are doing.”

Conclusion

Visiting for mission needs to be central to the ministry of Christ’s Church. Even though some devalue its effectiveness, they are sadly illinformed. When pastoral and lay visitation becomes a priority inside and outside of the body, Jesus is shared, care is given, and outreach happens. Please do not listen to the naysayers who say that visiting is outdated in a technological society. What else can combat loneliness, isolationism, and build relationships for the kingdom? Visiting will strengthen your congregation and promote pastoral effectiveness/longevity. Visit and see God’s Holy Spirit at work.

Please do not listen to the naysayers who say that visiting is outdated in a technological society.

Rev. Brad Hales is Pastor of Reformation Lutheran Church in Culpeper, VA and he teaches at St. Paul Lutheran Seminary.

Endnotes:

1Martin Luther, Small Catechism, in The Book of Concord, ed. by Robert Kolb and Timothy J. Wengert (Minneapolis, Minnesota: Fortress Press, 2000), 347.

2Lazarus Spengler in Martin Luther, Luther’s Works, Volume 49, Letters II, ed. Jaroslav Pelikan and Helmut T. Lehmann (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1955), 358-359.

3Kennon Callahan, Visiting In an Age of Mission (San Francisco: Harper Collins, 1994), 5.

4Crossway Bibles, The ESV Study Bible: English Standard Version (Wheaton, IL: Crossway Bibles, 2008). The ESV version is used throughout this essay.

DO NO HARM: A HIPPOCRATIC OATH FOR PASTORS

Randy Freund

When asked to address the conference title, “The Office of the Ministry,” I was given wide discretion. Having recently addressed a related theme at the Augustana Theological Convocation (LCMC) on "Pastoral Care: Battling Doubt, Despair, and Desperation,” I decided to take up where I left off on that topic as it relates to this one. But the odd title, “Do No Harm—A Hippocratic Oath for Pastors?” should suggest a different landing.

Pastor Care or Counseling?

At the February conference, I mentioned that pastors need to think carefully about words, and how they are used and how they change and how they can subtly shape the way we minister and understand the office of the ministry. Starting in the 18th and 19th centuries (with its fullest expression in the 20th Century) the term “pastoral care” was largely switched to pastoral counseling. It doesn’t seem like a big deal, but it turned out to be―especially as we think about the importance and uniqueness of the “Office of Ministry.” The change was

made largely because the word “counseling” seemed more acceptable in the academic world, generally, and the professional world of counseling, specifically. Pastors, of course, want to be taken seriously, we are “professionals,” after all! So, we went along with this.

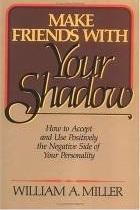

But with this change came other meanings. What was traditionally seen as “care of soul” shifted to “transformation of the mind.” And worse, “absolving sin” moved to “accepting sin.” One of my CPE instructors wrote a book that demonstrated this, called –“Make Friends with Your Shadow.”

Applying the Hippocratic Oath to Theology

All of this got me to thinking about what it might look like if we were to apply the Hippocratic Oath to theology, and more specifically, to the office of the ministry. This oath, to which medical doctors are to subscribe, is loosely translated: "First, do no harm." A related phrase is found in Epidemics, Book I of the Hippocratic school, and goes like this: "Practice two things in your dealings with disease: either help or do not harm the patient." When a colleague of mine noticed my title, he said, “Do not harm?” he thought that would be an interesting case to make when the whole point is to kill to make alive. I realize this and will address this.

The Hippocratic Oath struck me as a rather minimalist way of thinking about the role of a doctor. In the oath, one does not sense an aggressive motive to Heal! Cure! Be bold! Save lives! And if one were to apply it as an “oath” for pastors, it might read this way: "Practice two things in your dealings with sin (rather

than disease): Either help or do not harm the parishioner." This reminded me of a new term I learned from Dr. John Pless (one of the speakers at the AD theological convocation). It was the term “Clerical pessimism” or what I might term, “clerical shyness.” It refers to the way how we often underestimate the power of the Word and what God does with it. Part of the point of this presentation is to reflect on God’s word and the gift of faith as it relates to the specific and unique role of this office we hold. Martin Luther’s “one little word” is the greatest power on earth. It needs to be released! It needs a voice. We are the vessels of it, but it is all on God. That fact is good news. We not only seem to forget this, but we can actually undermine, that is, do harm to the very Word we proclaim the greatest power on earth (clerical pessimism).

So going back the Hippocratic oath as applied to pastors, we understand the Word of God as accomplishing far more than simply “helping” or at least “not harming” our parishioners. Jesus came that we may have life and have it abundantly. The new life offers a bit more than “helping” or “not harming.” All of this implies a death! We all get that. But in this presentation, I want us to think about how we use words and how we perceive their effect as we carry out our office in the daily life of being a pastor. As mentioned earlier, something not helpful, even harmful, happens when we forfeit the office by submitting to the subtle shift in pastoral ministry from “pastoral care” to “pastoral counseling.” This shift in language is not insignificant. It can actually derail us from the core of our pastoral office as it relates to the absolution of sinners. Again, this may not simply “not help,” but could “do harm.” The same can be true about the way we use phrases like “theology of glory” versus “theology of the cross,” “law/gospel,” and “right-hand-” and “left-hand-

kingdoms.”