Summer2024

Pre-Reformation Theologians

TheJournalofSt.PaulLutheranSeminary

SIMUListhejournalofSt.Paul LutheranSeminary.

CoverArt:

Lucas Cranach the Elder, “The Reformers Luther and Hus Giving Communion to the Princes of the House of Saxony,” (1553)

Disclaimer:

The viewsexpressedinthe articlesreflectthe author(s) opinionsand arenotnecessarilythe viewsofthe publisherand editor.SIMULcannotguaranteeand acceptsnoliabilityforany lossor damageofanykind causedby the errorsandfor theaccuracy ofclaims made by the authors.Allrightsreservedand nothingcan be partiallyor inwholebe reprintedor reproduced withoutwrittenconsentfrom the editor.

SIMUL

Volume 3, Issue 4, Summer 2024

Pre-ReformationTheologians

EDITOR

Rev. Dr.DennisR. Di Mauro dennisdimauro@yahoo.com

ADMINSTRATOR

Rev. JonJensen jjensen@semlc.org

AdministrativeAddress:

St. Paul LutheranSeminary P.O.Box251 Midland,GA 31820

ACADEMICDEAN

Rev. Julie Smith jjensen@semlc.org

Academics/StudentAffairsAddress: St. Paul LutheranSeminary P.O.Box112 Springfield,MN 56087

BOARDOFDIRECTORS

Chair:Rev. Dr. ErwinSpruth

Rev. GregBrandvold

Rev. JonJensen

Rev. Dr. MarkMenacher

Mr. Steve Paula

Rev. Julie Smith

Rev. CharlesHunsaker

Rev. Dr. JamesCavanah

Rev. Jeff Teeples

TEACHINGFACULTY

Rev. Dr. MarneyFritts

Rev. Dr. DennisDiMauro

Rev. Julie Smith

Rev. VirgilThompson

Rev. Dr. Keith Less

Rev. BradHales

Rev. Dr. ErwinSpruth

Rev. Steven King

Rev. Dr.OrreyMcFarland

Rev. HoracioCastillo(Intl)

Rev. AmandaOlsonde Castillo(Intl)

Rev. Dr. Roy HarrisvilleIII

Rev. Dr. HenryCorcoran

Rev. Dr. MarkMenacher

Rev. RandyFreund

EDITOR’S NOTE

Welcome to our twelfth issue of SIMUL, the journal of St. Paul Lutheran Seminary. This edition delves into the historical roots of Lutheranism with several insightful articles about pre-Reformation theologians.

In this volume, Mark Menacher begins our study with a well-researched article on the life and work of John Wycliffe. Menacher examines the similarities and differences between Wycliffe’s theology and later Lutheran thought, while also lamenting his acceptance of the prevailing justification theology of his day.

Former SPLS student and pastor Leah Krotz offers a beautifully-written essay on the work of 15th Century Czech theologian Jan Hus. Krotz explains how Hus’ courageous search for the truth of scripture still resonates today.

This edition delves into the historical roots of Lutheranism with several insightful articles about preReformation theologians.

Mark Ryman takes a somewhat broader approach to the topic, exploring how Hus’ and Wycliffe’s works personally influenced Luther, especially in the formulation of the Reformation doctrines of Sola Scriptura and Semper Reformanda. Ryman also contributes a beautiful hymn entitled “Wyclyf,” sung to the tune of the 1887 hymn “Wycliff,” written by John Stainer.

And I finish out this issue with a book review on Lauro

Martinez’s history (that reads like a novel), entitled Fire in the City: Savonarola and the Struggle for the Soul of Renaissance Florence published by Oxford University Press (2007). What can this little monk from Ferrara teach us about having the courage to stand up against corruptions that might arise in the Church?

What’s Ahead?

Upcoming Issues - Our Fall 2024 issue will tackle the topic of Free Will vs. Bondage of the Will.

SPLS now offers the Th.D. – We are excited to announce that St. Paul Lutheran Seminary is partnering with Kairos University in Sioux Falls, SD to establish an accredited Doctorate in Theology (Th.D.). The Th.D. is a research degree, preparing candidates for deep theological reflection, discussion, writing, leadership in the church and service towards the community. The goal of the program is to develop leaders in the Lutheran church who are qualified to teach in institutions across the globe, to engage in theological and biblical research to further the preaching of the gospel of Jesus Christ, and to respond with faithfulness to any calling within the church. Those who are accepted into and complete the program will receive all instruction from SPLS professors and will receive an accredited (ATS) degree from Kairos University.

The general area of study of the Th.D. program is in systematic theology. Specializations offered within the degree include, but are not limited to: Reformation studies, evangelical homiletics, and law and gospel dialectics. The sub-disciplines within the areas of specialization are dependent upon the

interest of the student provided they have a qualified and approved mentor. Other general areas of study, such as biblical studies, will be forthcoming. For the full description of the program, go to https://semlc.org/academic-programs/ If you are interested in supporting our effort to produce faithful teachers of Christ’s church, contact Jon Jensen jjensen@semlc.org. All prospective student inquiries can be directed to Dr. Marney Fritts mfritts@semlc.org.

Giving - Please consider making a generous contribution to St. Paul Lutheran Seminary at: https://semlc.org/support-st-paul-lutheran-seminary/.

I hope you enjoy this issue of SIMUL! If you have any questions about the journal or about St. Paul Lutheran Seminary, please shoot me an email at dennisdimauro@yahoo.com

JOHN WYCLIFFE: HERETIC OR REFORMER?

Mark Menacher

Controversy regarding the teachings of the Christian Church is as old as the Church itself. As St. Paul testifies in his letter to the Galatians, “I am astonished that you are so quickly deserting him who called you in the grace of Christ and are turning to a different gospel—not that there is another one, but there are some who trouble you and want to distort the gospel of Christ. But even if we or an angel from heaven should preach to you a gospel contrary to the one we preached to you, let him be accursed (ἀνάθεμα - anathama). As we have said before, so now I say again: If anyone is preaching to you a gospel contrary to the one you received, let him be accursed (ἀνάθεμα)” (Gal. 1:6-9 [ESV]).

Scripture as a Means of Resolving Controversy

In fact, it could be asserted that the New Testament was primarily written to remedy the deviations from and the disputes about the gospel of Jesus Christ in the nascent church. Consequently, time and again appellation has been made to

scripture, especially to the New Testament, to identify and to address the controversies which each new generation of sinners seems to spawn. Unfortunately, as St. Paul also indicates (Gal. 2:1-14), the inception, manifestation, identification, and possible resolution of ecclesial controversies also raises questions about authoritative texts, instances of judgement from authoritative persons, and the implicit or explicit hermeneutical principles employed to affirm the truth of the gospel. Not infrequently, appealing to scripture while utilizing faulty methods of its interpretation have given rise to “cures” at least as accursed as the maladies needing to be alleviated.

Was Luther a Wycliffite?

Depending upon one’s perspective, one person’s reformer is another person’s heretic. Lutherans are long accustomed to Martin Luther being considered both. When Luther appeared at the Imperial Diet in Worms in April 1521, he was so charged, “You have come as a spokesman of great, new heresies as well as those long since condemned; for many of the things which you adduce are heresies of the Beghards, the Waldenses, the Poor Men of Lyons, of Wycliffe and Huss, and of others long since rejected by the synods.”1 In Luther’s subsequent letter to the people of Wittenberg in June 1521, he states, “Thus our greatest suffering is that they decry us in the most shameless way as ‘Wycliffites,’ ‘Hussites,’ and

‘heretics.’”2 Could this accusation, however, have some validity? To what extent might Luther have been a Wycliffite?

The Gospel Doctor

John (de) Wycliffe,3 also found spelled as Wyclif,4 Wickliff,5 Wyclyffe,6 Wigleff, Wycleph, and Wikleph7 to cite a few variants, was a fourteenth-century, English philosopher and theologian. “The biographers of Wycliffe all mention the year 1324 as that of his birth,”8 except for those more recently who cite 1330.9 Wycliffe hailed from the Yorkshire village of Wycliffe-upon-Tees, and in 1342 “the family village and manor came under the lordship of John of Gaunt (1340-1399), the Duke of Lancaster and the second son of King Edward III.”10 John of Gaunt was a patron of both Wycliffe and Geoffrey Chaucer, and some speculate “that Chaucer in the Canterbury Tales based his characterization of ‘The Parson’”11 on Wycliffe. Both Wycliffe and Chaucer spoke and wrote in Middle English. In the following excerpt, Wycliffe expresses his sentiments regarding the sacrament of the altar as the body of the Lord, which Lutherans on initial impression might welcome:

Of al þe feiþ of þe gosþel gederen trewe men, wiþ opyne confescioun of þes newe ordris, þat men shulden rette hem eretikis, & so not comyne wiþ hem. for þei denyen þe gosþel & comyn bileeue, þat þat breed þat crist took in hise hondis & blesside it & brac it & ʒaf it to hise disciplis for to ete, was his owne bodi bi vertu of his wordis. & þus þei denyen þat þe oost sacrid, whijt & round, þat bifore

was breed, is maad goddis bodi bi uertu of hise wordis... (see note for author’s translation).12

In 1340 (or 1346),13 at the age of sixteen Wycliffe entered Queen’s College, Oxford as a commoner. Queen’s College was a new college designed for students from the northern counties of England. Remaining there briefly, Wycliffe moved to Merton College, Oxford where Ockham and Duns Scotus are claimed to have been fellows. Notably, Ockham questioned the infallibility of Pope John XXII, and he also advocated civil authority over against ecclesiastical power. This heritage perhaps explains why Wycliffe enthusiastically studied scholastic philosophy. In the scholastic view, Aristotle was deemed to be the safest way to ascertain the meaning of St. Paul. In addition to scholastic studies, Wycliffe diligently studied civil and canon law, with the former based on jurisprudence of the Roman Empire which was adopted in various ways by the nations of feudal Europe. Canon law embodied the decrees of councils and popes which sought dominion over both ecclesial and civil realms. Whereas civil laws often included national innovations, particularly in England, the church sought to recreate the Roman imperial empire. Wycliffe defended English civil law over foreign domination whether civil or ecclesiastical. In contrast to many of his day, Wycliffe sought to establish religious truth based solely on the authority of scripture which won him the name “Gospel Doctor.”14

In 1345, the plague arose in the orient, and by August 1347 when Wycliffe was 23 it had reached England. The devastation in human and economic terms left a lasting impression on Wycliffe. The plague subsided in 1348, and Wycliffe’s first work, entitled the Last Age of the Church dated 1356, seems to reflect the apocalyptic nature of this devastation. Perhaps more importantly, this book allows Wycliffe to express his view of the recompense earned by the Church having grown greedy and haughty. Wycliffe opens his book with a reference to Psalm 107:10 (Vulgate [Latin Bible] 106:10) of “great priests sitting in darkness, in the shadow of death,” which refers to the prelates and friars who “make reservations, which they call tithes, first fruits, other pensions”15 to accumulate for themselves wealth at the expense of the country’s resources. With frequent biblical references and numeric-alphabetical symbols,16 Wycliffe decries this heretical simony as the work of the anti-Christ, which will elicit four tribulations to desolate the church.17 The apocalyptic proportions of this book foreshadow Luther’s critique of the calamitous state and fate of the papal church.18

In 1361, Wycliffe earned his Master of Arts, was ordained in the diocese of Lincoln, became the rector of Fillingham (or Fylingham) in Lincolnshire,19 and was elected the warden of Baliol College, Oxford, both seemingly as rewards for his opposition to the mendicant friars.20 In 1365, Pope Urban (Avignon, France)21 demanded from King Edward III the annual tribute of 1,000 marks, as papal-feudal acknowledgment of his sovereignty over England and Ireland, and also 33 years of arrears. “According to the ecclesiastical theory of the middle

age, the church is the parent of the state, bishops are as fathers to princes, and the authority of all sovereigns must be subordinate to that of the successors of St. Peter.” In response, Wycliffe drafted a series of speeches based on feudal right, civil law, and the precepts of scripture. When parliament convened in 1366, these speeches were delivered by secular lords and affirmed that the king could deny paying the tribute to the pope, could subject all clergymen to civil law and its magistrates, and in certain circumstances could expropriate the church’s possessions.22 Subsequently, parliament also enacted laws to shield the universities from the exploitative proselytizing of the mendicant orders, from any injurious action by the pope, and from the ecclesiastical courts being allowed to favor the mendicant orders in seminary disputes. Wycliffe probably influenced this legislation too. Again, apparently as a reward for his efforts on behalf of the crown, Wycliffe was designated one of the royal chaplains in 1366.23

In 1369, Wycliffe received his Bachelor of Divinity, and in 1370, he started to challenge papal doctrines, particularly transubstantiation in the eucharist.24 Under the secret influence of John of Gaunt and with Wycliffe’s advocacy, in 1371 the English Parliament sought to exclude churchmen from holding high office, a common and pervasive practice. As Wycliffe writes, “Neither prelates, nor doctors, priests nor

deacons, should hold secular offices, that is, those of Chancery, Treasury, Privy Seal, and other such secular offices in the Exchequer; neither be stewards of lands, nor stewards of the hall, nor clerks of the kitchen, nor clerks of accounts; neither be occupied in any secular office in lords’ courts, more especially while secular men are sufficient to do such offices.”25 Because the Avignon papacy was composed mainly of Frenchmen, Edward’s antipathy both to papal demands for the tribute and to other papal assertions of power on the British Isles should be viewed as yet another manifestation of Anglo-French national rivalries ever present during their Hundred Years’ War (1337–1453). In 1372, Wycliffe received his doctor of divinity, and therewith his influence in academia grew.

26

Wycliffe’s political and ecclesial endeavors won him many ecclesial enemies. In February 1377, William Courtney, newly elevated bishop of London and son of the powerful Hugh Courtney, Earl of Devonshire, sought to quell Wycliffe’s ideas and thus summoned him to appear before parliament “to answer to the charge of holding and publishing certain erroneous and heretical opinions.” Accompanied by John of Gaunt and Lord Percy, Wycliffe arrived on 19 February at St. Paul’s Cathedral, but a verbal dispute between Gaunt and Courtney caused the proceedings to descend into chaos with no action being taken against Wycliffe.27 In June 1377, King Edward III died and was succeeded by his ten-year-old grandson, Richard II, who was less accommodating of Wycliffe’s views.

Having issued five bulls against Wycliffe in May 1377, Pope Gregory XI, who had moved the papacy from Avignon

back to Rome, sent letters to the king of England, the archbishop of Canterbury, the bishop of London, and Oxford University calling upon them to condemn Wycliffe and to prevent the dissemination of his teachings.28 In response, Wycliffe issued a protestatio:

First of all, I publicly protest, as I have often done at other times, that I will and purpose from the bottom of my heart, by the grace of God, to be a sincere Christian; and as long as I have breath, to profess and defend the law of Christ so far as I am able. And if, through ignorance, or any other cause, I shall fail therein, I ask pardon of God, and do now from henceforth revoke and retract it, humbly submitting myself to the correction of Holy Mother Church...

[That said] I am willing to set down my sense in writing, since I am prosecuted for the same. Which opinions I am willing to defend even unto death, as I believe all Christians ought to do, and especially the pope of Rome, and the rest of the priests of the church. I understand the conclusions, according to the sense of Scripture and the holy doctors, and the manner of speaking used by them; which sense I am ready to explain: and if it be proved that the conclusions are contrary to the faith, I am willing very readily to retract them.29

Wycliffe continued by offering eighteen articles to defend

his positions and subsequently agreed to “house arrest” in his parish in Lutterworth, to which he had been appointed in 1374. Neither Oxford University nor the government would condemn their prize scholar and patriotic servant, respectively.30 Wyliffe’s self-imposed “exile” became the most prolific period of his life.

The Trialogus

Among Wycliffe’s many volumes of collected works, his Trialogus, structured as a three-way conversation between Alithia (or Alethia), Pseudis, and Phronesis,31 arguably offers the most succinct summary of his theological positions and his arguments against his adversaries. Wycliffe begins Trialogus, Book VI, Chapters I-IX, with a discussion against transubstantiation in the eucharist. “I shall briefly set forth the doctrine as supported by the testimony of Scripture. In the first place, this sacrament is the body of Christ in the form of bread. ... Since this article of catholic belief is so broadly expressed in Scripture, the doctrine [of transubstantiation] contrary to it is manifestly heretical. ... It would be well for the church universal to attend to this matter, ... because this matter is decided with greater completeness, authority, and moderation, in the Gospel of Christ than in the court of Rome.”32 “But how then, by virtue of this sentence [This is my body], comes transubstantiation, or the accident without a subject? ... [T]hese heretics cannot state at what instant transubstantiation, or the accident without a subject, really takes place.” “No one of the saints, prior to the loosing of

Satan, was acquainted with [transubstantiation].”33 “The believer, therefore, hesitates not to affirm, that these heretics are more ignorant, not only than mice and other animals, but than pagans themselves; while on the other hand, our aforementioned conclusion, that this venerable sacrament is, in its own nature, veritable bread, and sacramentally Christ’s body, is shown to be the true one.”34

For also denying transubstantiation, Luther in The Babylonian Captivity of the Church states, “Here I shall be called a Wycliffite and a heretic by six hundred names.”35 Despite this apparent endorsement, Wycliffe’s understanding of the “real presence” in a Lutheran sense, is not present. Further on, Wycliffe states, “The body of Christ is not co-extensive with the body of the bread ... it hath been stated already that the body of Christ is there spiritually ... it should be granted, that the body of Christ is there, beautifully, and really. Yet I dare not say, that it is there dimensionally, or in extent, though it may be bread which is there dimensionally, and in extent.”36

For also denying transubstantiation, Luther in The Babylonian Captivity of the Church states, “Here I shall be called a Wycliffite and a heretic by six hundred names.”

In Chapter XIV “On the Avarice of the Clergy,” Wycliffe seeks to separate clergy from worldly corruption by liberating them from being “possessed” by worldly possessions. “It is plain that the man imbibing the spirit of the Gospel pleases Christ the more, other things being equal, the greater the poverty in which he fulfils his office. ... Thus some understand the words of Christ, ‘And ye shall carry nothing on your

journey, neither scrip,’ &c.; for apostolic men should not be delayed by anything temporal that may impede their affections or their efforts in the discharge of duty. ... [F]or possession in a civil sense, since it necessitates a carefulness about temporal things, and the observance of human laws, ought to be strictly forbidden to the clergy.”37 Philip Melanchthon in the Apology of the Augsburg Confession, Article XVI, takes a different view. “It is also false (vanissimum) to claim that Christian perfection consists in not holding property. What makes for Christian perfection is not contempt of civil ordinances but attitudes of the heart, like a deep fear of God and a strong faith. ... Wycliffe was obviously out of his mind (furebat Vuiglefus) in claiming that priests were not allowed to own property.”38

Regarding the mendicant (begging) orders, Wycliffe viewed begging in two ways. The first pertains to begging from God, as petitioning in prayer, “for it became Christ thus to beg, for the interests of his church.” Other begging seeks something from human beings. “But if the friars make a sophistical use of such begging, and beg stoutly from the people with clamour and annoyance, who can doubt that this begging is a diabolical and sophistical perversion of this act of Christ’s, so full of goodness, and so serviceable to his church? Beyond this the friars defend their falsehood, by adding, that it is not only proper, but absolutely meritorious thus to embrace a life of voluntary poverty.”39 “I see clearly, from the reasons adduced, and from many others that might be brought forward, if need were, that this mendicancy of the friars is not only without scriptural authority, but a manifest blasphemy.”40

In Chapter XXIV “On Indulgences,” Wycliffe states, “I confess that the indulgences of the pope, if they are what they are said to be, are a manifest blasphemy, inasmuch as he claims a power to save men almost without limit, and not only to mitigate the penalties of those who have sinned, by granting them the aid of absolutions and indulgences, that they may never come to purgatory, but to give command to the holy angels, that when the soul is separated from the body, they may carry it without delay to its ever lasting rest.” “In such infinite blasphemies is the infatuated church involved, especially by the means of the tail of this dragon, that is the sects of the friars, who labour in the cause of this illusion, and of other Luciferian seductions of the church.”41 Plainly, Wycliffe’s attacks on the papal institution of indulgences resonate strongly with Luther’s positions.

How Did the Lutheran Reformers View Wycliffe?

Regarding the doctrine by which the church stands or falls, “Melanchthon considered [Wycliffe] unsound on the doctrine of justification.”42 “On the great doctrines of Justification and Merit,” however, “Dr. James quotes passages, which prove Wickliff to have taught ‘That faith in our Lord Jesus Christ, is sufficient for salvation, and that without faith it is impossible to please God; that the merit of Christ is able, by itself, to redeem all mankind from hell, and

that this sufficiency is to be understood without any other cause concurring; he persuaded men therefore to trust wholly to Christ, to rely altogether upon his sufferings, not to seek to be justified but by his righteousness; and that by participation in his righteousness, all men are righteous.’”43 Unfortunately, this particular source provides no citations to support such assertions, but more apparent, Wycliff’s writings are by and large devoid of discussion about or concern for the doctrine of justification.

On the topic of free will, Luther extolls Wycliffe. In the Bondage of the Will, over against Erasmus and the like, Luther sees only himself, Wycliffe, Laurentius Valla (the Italian humanist who exposed “Donation of Constantine”44 as forged), and Augustine on the right side of the debate.45 Later, Luther reduces this group to two. “The third and hardest opinion is that of Wycliffe and Luther, that free choice is an empty name and all that we do comes about by sheer necessity. It is with these two views that Diatribe quarrels.”46 “For I take the view that Wycliffe’s article (that ‘all things happen by necessity’) was wrongly condemned by the Council, or rather the conspiracy and sedition, of Constance.”47 Wycliffe himself, however, seems to advocate more free will than Luther might be willing to accommodate:

Here true men say that as God has ordained good men to bliss, so has God ordained them to come to bliss by the preaching and keeping of God’s word; and so that they shall necessarily come to bliss, they must necessarily hear and keep God’s commands, and herewith serves preaching to them;... [F]or this each man has free will and

choosing of good and evil. No man shall be saved unless he has willfully and eternally kept God’s commands, and no man shall be damned unless he has willfully and eternally broken God’s commands and forsaken thus and blasphemed God [author’s translation].48

Finally, similar to the preceding, Wycliffe regards the catholic Church as the sum of all the predestined.49 This Church is composed of three parts, the blessed in heaven, the sleeping in purgatory, and the militant engaged in conflict on earth. The election of the predestined is solely God’s prerogative. The church has only one head, Jesus Christ. No Christian has the power to determine that the pope is either the head or even a member of the church, for such consists again by God’s predestination and grace.50 According to Wycliffe, Christ came to effect a separation in humanity, however not like their separation from God due to sin. Ecclesially considered, Christ came so that the church could discern and separate heretics from itself. “For this reason, therefore, it is necessary for every catholic to know the holy scriptures.”51 This explains why Wycliffe spent the remainder of his life, until death by a stroke on New Year’s Eve in 1378, working to produce a full translation of the Vulgate Bible into English. Like his richly productive life, the Roman Church could not accommodate Wycliffe’s natural death. In 1415, the

For many, Wycliffe was a heretic. For others, he was the “morning star of the Reformation.” For Lutherans, Wycliffe is a bit of both, not substantially a heretic and yet not truly a reformer, perhaps primarily so because prioritizing St. Paul’s law-gospel hermeneutic seemed not to dawn on him.

Council of Constance condemned Wycliffe of 267 heresies, and in 1428, the pope ordered Wycliffe’s remains to be dug up, burned, and scattered on the River Swift.52 For many, Wycliffe was a heretic. For others, he was the “morning star of the Reformation.”53 For Lutherans, Wycliffe is a bit of both, not substantially a heretic and yet not truly a reformer, perhaps primarily so because prioritizing St. Paul’s law-gospel hermeneutic seemed not to dawn on him.

Rev. Dr. Mark Menacher is Pastor of St. Luke’s Lutheran Church, La Mesa, CA.

Notes:

1Luther’s Works, American Edition, 55 vols., editors, J. Pelikan and H. Lehmann (Saint Louis: Concordia Publishing House and Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1955), 32: 129 [hereafter LW]. See also, D. Martin Luthers Werke - Kritische Gesammtausgabe (Weimar: Hermann Böhlau, 1883-2009), 7:837,13-16 [hereafter as WA].

2LW 48:249 = WA 8:210,22-23.

3John de Wycliffe, Tracts and Treatises of John de Wycliffe, ed. Robert Vaughan (London: Blackburn and Pardon, 1845), [hereafter Tracts and Treatises]. Heretic genealogies have been common in the history of the church, see Ulrich G. Leinsle, “Kollektive Identitäten in spätmittelalterlichen Häresien” in Geschichtsentwürfe und Identitätsbildung am Übergang zur Neuzeit - Geschichtsentwürfe und Identitätsbildung am Übergang zur Neuzeit, vol. 41,2, eds. Ludger Grenzmann, Udo Friedrich and Frank Rexroth (Berlin/Boston: Walter de Gruyter, 2018), 53-54 [hereafter Leinsle].

4Iohannis Wyclif, Tractatus de Ecclesia, ed. Iohann Loserth (London: Wyclif Society by Trübner & Co, 1886) [hereafter Tractatus de Ecclesia].

5John Wickliff, Writings of the Reverend and Learned John Wickliff, D.D. (Philadelphia: Presbyterian Board of Publication, 1842) [hereafter Writings].

6John Wyclyffe, The Last Age of the Church, ed. James Henthorn Todd (Dublin: University Press, 1890) [hereafter Last Age].

7Leinsle, 43 and 55.

8Tracts and Treatises, i.

9Donald I. Roberts, “The Dawn of the Reformation,” Christian History - Special Commemorative Issue Devoted to John Wycliffe and the 600th Anniversary of Translation of the Bible into English, II, 2 (1983), 10 [hereafter Roberts, Dawn].

10Roberts, Dawn, 10. Vaughn considers John of Gaunt, a statesman, military leader, and literary, who had sympathies with Wycliffe’s ecclesial reforming views, to be the fourth son of Edward III (Tracts and Treatises, xxv].

11“A Gallery of his Defenders, Friends and Foes,” Christian History - Special Commemorative Issue Devoted to John Wycliffe and the 600th Anniversary of Translation of the Bible into English, II, 2 (1983), 15, see also 33.

12John Wycliffe, The English Works of Wyclif: Hitherto Unprinted, ed. F. D Matthew (London: Trübner & Co., 1880), 356-357 [hereafter Hitherto Unprinted]. “Although true men assemble in the faith of the gospel, with open confession against these new orders [of mendicant friars], that men should consider them heretics and not commune with them, for they deny the gospel and common belief, that that bread that Christ took in his hands and blessed it and broke it and gave it to his disciples to eat, was his own body by virtue of his words, and thus they deny that the host, sacred, white, and round, that was bread before, is made God’s body by virtue of his words...”

13Roberts, Dawn, 10.

14Tracts and Treatises, ii-iii, v-vii.

15Psalm 106:10 in the vulgate reads, “Sedentes in tenebris et umbra mortis; vinctos in mendicitate et ferro,” translated as “Ones sitting in darkness and the shadow of death; bound in beggary and iron.” One wonders for Wycliffe whether mendicitate (beggary) provided biblical grounds to refer to the greed and hypocrisy of the supposedly poor mendicant friars.

16Wycliffe uses the number of letters in the Hebrew and Latin alphabets multiplied by 100 to signify various aspects of biblical and church historical chronology.

17Last Age, xxiii-xv.

18“For ... the pope’s church is full and swarming with falsehood, devils, idolatry, hell, murder, and every kind of calamity. Thus it is time to hear the voice of the angel in Revelation 18 [:4–5], ‘Come out of her, my people, lest you take part in her sins, lest you share in her plagues; for her sins are heaped high as heaven,’ etc.” (LW 41:206 = WA 51:499,28-32). “Thus we are warned in Revelation (18:4) to depart from Babylon and forsake her; that is, we should completely separate ourselves from the pope’s church, unless we want to perish with it” (LW 3:280 = WA 3:75,40-42).

19“Christian History Timeline: Wycliffe’s World,” Christian History - Special Commemorative Issue Devoted to John Wycliffe and the 600th Anniversary of Translation of the Bible into English, II, 2 (1983), 19 [hereafter Timeline).

20Tracts and Treatises, vxi.

21Under pressure from French King Phillip IV, Pope Clement V, also a Frenchman, moved the papacy from Rome to Avignon, France in 1309, where it remained until 1377, when it was returned to Rome by Pope Gregory XI.

22Tracts and Treatises, vxiii-xx.

23Tracts and Treatises, xxiv-xxv.

24Timeline, 19.

25Tracts and Treatises, xxvi-xxvii. “At that time the offices of Lord Chancellor, and Lord Treasurer, and those of Keeper and Clerk of the Privy Seal, were filled by clergymen. The

Master of the Rolls, the Masters in Chancery, and Chancellor and Chamberlain of the Exchequer, were also dignitaries, or beneficed persons of the same order. One priest was Treasurer for Ireland, and another for the Marches of Calais; and while the parson of Oundle is employed as surveyor of the king’s buildings, the parson of Harwick is called to the superintendence of the royal wardrobe.”

26Tracts and Treatises, xxvii.

27Tracts and Treatises, xxxiv-xxxv.

28Tracts and Treatises, xxxvi-xxxvii. See also “Five Bulls of Pope Gregory XI against Wycliffe,” Christian History - Special Commemorative Issue Devoted to John Wycliffe and the 600th Anniversary of Translation of the Bible into English, II, 2 (1983), 22.

29Tracts and Treatises, xxxix.

30Roberts, Dawn, 12.

31Writings, 36. Printed in 1524, Trialogus “contains a series of dialogues between three persons, characterised as Alethia, or Truth, Pseudis, or Falsehood, and Phronesis, or Wisdom. Truth represents a sound divine, and states questions; Falsehood urges the objections of an unbeliever; Wisdom decides as a subtle theologian. This work probably contains the substance of Wickliff’s divinity lectures, with considerable additions. It embraces almost every doctrine connected with the theology of that day, treated however in the scholastic form then universal.” The editors of Luther’s Works speculate, “Luther may have read Wycliffe’s Trialogue, which had been printed in 1525, but his knowledge of the Englishman’s writings was fragmentary” (LW 37:294 note 222).

32Tracts and Treatises, 133.

33Tracts and Treatises, 136-137.

34Tracts and Treatises, 140.

35LW 36:28 = WA 6:508,3.

36Tracts and Treatises, 154. See also LW 37:294 note 222.

37Tracts and Treatises, 170-172.

38The Book of Concord, ed. Theodore G. Tappert (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1959), 224.9 and 224.11. See also Die Bekenntnisschriften der Evangelisch-Lutherischen Kirche, 13th edition (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1982), 309.9 and 309.11 which rendered more accurately from the Latin says, “Wycliffe was furious.”

39Tracts and Treatises, 186.

40Tracts and Treatises, 188.

41Tracts and Treatises, 195 and 198.

42Life and Times of John Wycliffe: The Morning Star of the Reformation (London: Religious Tract Society, 1884), 151 [hereafter Morning Star].

43Writings, 41.

44The Donation of Constantine was a forged document of the Middle Ages which claimed that Constantine the Great (ca. 280-337) gave Pope Sylvester I (314–335) extensive property and temporal power.

45LW 33:72 = WA 18:640,8-9.

46LW 33:116 = WA 18:670,25-27.

47LW 33:160 = WA 18:699,15-17.

48Hitherto Unprinted, 111. Excerpt from Tract V: Speculum de Antichristo, “Here seyn trewe men þat as god haþ ordeyned goode men to blisse, so god haþ ordeyned hem to come to blisse bi prechynge & kepyng of goddis word; and so as þei schullen nedis come to blisse, so þei moten nedis here & kepe goddis hestis, & herof serueþ prechynge to hem; and summe wickid men now schullen be conuertid bi goddis grace & herynge of his word. And who knoweþ þe mesure of goddis mercy, to whom herynge of goddis word schal þus profite? eche man schal hope to come to heuene & enforce hym to here & fulfille goddis word, for siþ eche man haþ a free wille & chesyng of good & euyl, no man schal be sauyd but he þat willefully hereþ and endeles kepiþ goddis hestis, and no man schal be dampnyd but he þat wilfully & endeles brekiþ goddis comaundementis, & forsakiþ þus & blasphemeþ god. & herynge of goddis word & grace to kepen it, frely ʒouyn of god to man but ʒif he wilfully dispise it, is riʒt weie to askape þis peril & come to endeles blisse; & here-fore synful men owen wiþ alle manere mekenesse & reuerence & deuocion heren goddis word & grucchen not ne stryue aʒenst prechynge of cristis gospel.”

49Tractatus de Ecclesia, 405. “...descripcio autem ecclesie catholice est condicionis opposite, dum recte breviter et plane dicitur quod ecclesia catholica est universitas predestinatorum.”

50Tractatus de Ecclesia, 19. “...non est in potestate alicuius christiani constitucione, eleccione vel acceptacione statuere quod dominus papa sit caput vel membrum sancte matris ecclesie. Nam hoc consistit in predestinacione et gracia Dei nostri.”

51Tractatus de Ecclesia, 41. “Christus ergo venit non ad faciendum primam separacionem que est proprie per peccatum, sed ad faciendum sequentem, ut per eum discernantur heretici et ab ecclesia separentur. Et hec racio - quare oportet omnem catholicum cognoscere scripturam sacram.”

52Timeline, 20.

53Cf., note 41.

JAN HUS: REFORMER AND MARTYR

Leah Krotz

In 1520, almost three years after posting his ninety-five theses on the church doors at Wittenburg, Martin Luther wrote, “I have taught and held all the teachings of John Hus, but thus far did not know it. John Staupitz has taught it in the same unintentional way. In short we are all Hussites and did not know it. Even Paul and Augustine are in reality Hussites.”1

What is a Hussite?

So what is a Hussite? In short, a follower of the fifteenthcentury Bohemian preacher and theologian, Jan (or John) Hus. When he wrote these words, Luther had just finished reading Hus’s treatise on the church, De Ecclesia, and had come to the realization that his own beliefs were similar to those of a man he had long considered to be a heretic, and had despised accordingly.

It turned out that as they studied the Bible independently and more than a century apart, the Holy Spirit had led the two

men to very similar conclusions, particularly regarding the authority of the scriptures. They had much else in common as well—except for the way their reforming tendencies played out. Luther’s story could very easily have ended in the same way as Hus’s, and had that happened, the Protestant Reformation might never have occurred.

Both Luther and Hus came from humble backgrounds; both entered the priesthood and found themselves at odds with the papacy and the church hierarchy after their studies led them to question certain practices. Both were popular preachers and teachers, affiliated with universities in their respective regions of Europe. And both were eventually summoned by the church authorities to answer for their beliefs and asked to recant their teachings. The role that each man’s ruling prince played in supporting them, particularly in regard to the sale of indulgences, proved pivotal in how their respective stories played out.

The Life and Work of Jan Hus

Let’s take a look at the life and work of the lesser-known Jan Hus and see how much he had in common with Martin Luther, the most famous of the reformers and a man considered to be one of the most influential of the millennium.2

Hus was born of peasant stock and admitted that he originally became a priest because he thought it was a path to greater prosperity and status. Around the year 1390 he

enrolled in the University of Prague, and following his graduation in 1394 he received a master’s degree and began teaching at the university. He was appointed dean of the philosophical faculty in 1401.

Hus was a talented speaker and was eventually appointed to be the preacher at Bethlehem Chapel in Prague, where the proclamation was given in the languages of the people, in Czech and German. Also serving as the chancellor at the University of Prague, Hus was well-liked. He was considered to be “a brilliant theologian endowed with an attractive sense of humor.”3

The Czech reform movement was already occurring when Jan Hus was born in 1372 in Husinec, Bohemia, which is now located in the Czech Republic. This religious reawakening in Bohemia was due in part to the emergence of the Czech language and the revival of national identity led by Charles IV, king and emperor, who ruled in Bohemia from 1333 to 1378.4

Charles wanted his capital, Prague, to be a great political and cultural center, and in 1348 he established a university there that he hoped would rival those of Oxford and Paris. In this place of creativity, scholarship, and the flourishing of new ideas and new ways of thinking, Hus and others found the perfect atmosphere to develop their beliefs. The more he studied the scriptures, the more Hus found his faith deepening and his convictions becoming stronger. He was convinced that the Roman church was in error, and was determined to write and speak openly about his convictions.

Hus had been influenced by earlier Czech reformers and preachers Milic Kormeriz (c. 1325-75) and Matthew of Janov (c.

1355-94). Both of these men had preached against the lax morality of the clergy and advocated for a return to the simplicity of the early church. Either Matthew himself or his followers had translated the whole Bible into Czech, and the disciples of Kormeriz were the founders of Bethlehem Chapel, where Hus preached and first gained a popular following.

In his preaching and writings, Hus emulated these men in emphasizing purity of conduct and personal piety. Hus protested the lax morals of the clergy and their abuses of power. He dared to question the authority of the pope, writing in De Ecclesia, “If he who is to be called Peter’s vicar follows in the paths of virtue, we believe that he is his true vicar and chief pontiff of the church over which he rules. But, if he walks in the opposite paths, then he is the legate of antichrist at variance with Peter and Jesus Christ. No pope is the manifest and true successor of Peter, the prince of the apostles, if in morals he lives at variance with the principles of Peter and if he is avaricious.”5

Hus and his colleagues were dismayed by the fact that the church owned about one-half of all the land in Bohemia, and that the higher orders of clergy had great wealth and were guilty of simony—the buying and selling of church offices. The Bohemian peasants also resented the Church, since it was one of the heaviest land taxers. The papacy itself had been greatly weakened by the Western Schism, as rival popes fought for power. All of these factors meant that the time was ripe for a church reform movement.6

Hus was also indebted to the work of Englishman John

Wycliff (ca. 1330-1384), the Oxford scholar and eventual parish priest who had asserted that the Bible was the sole authority of the church. He also opined that popes and cardinals were not necessary for the governance of the church and that unworthy popes should be deposed.7 Wycliff’s followers had also published the first translation of the Bible into the English language. Wycliff’s writings made their way to Bohemia after Anne of Bohemia married Richard II of England in 1382, via Czech students who had studied at Oxford.

Like Wycliff, Hus eventually questioned the doctrine of transubstantiation and advocated for the laity to receive both the bread and the wine in Holy Communion. Although defending the traditional authority of the clergy, he believed that only Christ could forgive sin. Hus insisted that the true Church was not to be found in Rome, but rather was the body of Christ, made up of all the redeemed of every time and place: the elect of God, known only to God.

But Hus didn’t just criticize the church and its hierarchy. He urged his fellow Christians not to obey any directive or doctrine from popes or cardinals that was contrary to scripture. Hus chastised his parishioners for their faith in superstitions, pilgrimages, indulgences, false miracles, and for worshipping images.

He also tried to live up to the standards he set for others. “His purity of character was such that no charge was ever made against it in Bohemia or during his trial in Constance.”8 But although he had a great deal of popular support, Hus also made enemies. Hus was the adviser to a young nobleman named Zbyněk Zajíc when he was elevated to archbishop of Prague in 1403. At first, this connection was helpful to the fledging reform

movement, but later circumstances conspired against Hus. Also in 1403, a German university master, Johann Hübner, drew up a list of 45 articles, supposedly selected from Wycliffe’s writings, and had them condemned as heretical. Because the German masters at Prague University had three votes and the Czech masters only one, the Germans easily outvoted the Czechs, and the 45 articles were regarded as a test of orthodoxy from that time on. Hus did not share all of Wycliffe’s views, but several members of the reform party, including Hus’s teacher, Stanislav of Znojmo, and his fellow student, Štěpán Páleč, did support Wycliff’s more radical teachings.

During the first five years of Zbyněk’s tenure as the archbishop of Prague, his attitude toward reform changed dramatically as the reform opponents won him over to their side. In 1407, Stanislav and Páleč were charged with heresy, and were taken to Rome for examination. Rather than standing by their beliefs, these two men returned to Prague completely transformed. They became the chief opponents of the reformers’ theology. This meant that just when Jan Hus had become the leader of the Bohemian reform movement, he immediately came into conflict with his former friends.9

As the leader of reform, Hus disagreed with Archbishop Zbyněk when he opposed the Council of Pisa of 1409, which was called to unseat the rival popes and reform the church. The Czech masters at the University of Prague supported the council, but the German masters of the university were opposed to it. King Wenceslas, who had taken the throne in 1378 after the death of

his father, Charles, was furious with the German divines. In January of 1409, he undermined the university’s constitution, granting the Czech masters three votes each, while allowing the Germans only one. Most of the German faculty responded by leaving Prague to affiliate with various German universities. In the fall of 1409, Hus was elected rector of the University of Prague, which was now dominated by Czechs.

When the Council of Pisa finally deposed both Pope Gregory XII, whose authority was recognized in Bohemia, and the antipope Benedict XIII, electing Pope Alexander V in their place, Hus and Archbishop Zbyněk completely parted ways. The archbishop, along with other higher clergy in Bohemia remained loyal to Gregory, while Hus and the reformers, along with reformminded King Wenceslaus, accepted the new pope.

King Wenceslaus forced the archbishop to recognize Alexander V as the legitimate pope, so the archbishop retaliated by offering a large bribe to convince Alexander to forbid preaching in private chapels. This edict included the Bethlehem Chapel, where Hus preached in the Czech language. He refused to obey the pope’s directive, which gave Zbyněk the ammunition he needed to excommunicate Hus. But Hus continued to ignore these directives from the church hierarchy, carrying on preaching at Bethlehem Chapel and teaching at the University of Prague. Eventually the king forced Zbyněk to promise Hus his support in his excommunication proceedings. However, Zbyněk died suddenly in 1411, and Hus now had to answer to the church hierarchy with little support from the ecclesial authorities in Prague.

In 1412, a new dispute arose over the sale of indulgences that had been issued by Alexander’s successor, the antipope John

XXIII, to finance his campaign against his rival, Gregory XII.10 In spite of widespread disapproval of the practice in Bohemia, King Wenceslas, who shared in the proceeds, gave his stamp of approval. This led Hus and his former student, Jerome of Prague, to publicly dispute the practice. Following their disputation, they burned John XXIII’s decree authorizing the sale of indulgences. Hus also publicly condemned these indulgences before the university community. By taking this stand, he lost the support of King Wenceslas and thus sealed his fate.

Hus’ Excommunication and Exile

Hus’s enemies renewed his excommunication trial, where he was declared guilty for refusing to appear. In addition, an interdict was pronounced over Prague or any other place where Hus might reside. This meant that certain sacraments of the church would be denied to parishioners in the area under the interdiction. Hus voluntarily left Prague in October 1412 in order to spare the people this punishment. He found refuge in the castles of friends, mostly in southern Bohemia. During the next two years he did a great deal of writing, responding to treatises written against him as well as writing his most famous work, De ecclesia (The Church). He also wrote many essays in the Czech language and a collection of sermons.

Meanwhile, the Western Schism continued. When King Sigismund of Hungary was elected emperor of Germany in 1411,

he hoped to gain status by restoring unity to the church, and he also sought to unite his vast kingdoms in order to fend off the Turkish threat. By forcing John XXIII to convene the Council of Constance, he planned to end the schism and stamp out the reformers’ so-called heresies.

Hus’ Trial at the Council of Constance

Sigismund invited Hus to attend the council to explain his views—but Hus was understandably reluctant to comply. Eventually John XXIII threatened King Wenceslas for noncompliance with the interdict, and this, combined with the fact that Sigismund promised Hus safe-conduct for his travels to Constance and back (no matter what the outcome might be), convinced Hus to make the journey. His supporters feared he was walking into a trap, but Hus apparently believed he would be able to defend the orthodoxy of his views against charges of heresy. In addition, he wanted to show that his followers in the kingdom of Bohemia were also orthodox Christians. Hus arrived in Constance in November of 1414. His safe-conduct was ignored, and soon after his arrival he was thrown into prison, with Sigismund’s implicit consent. He was never given the chance to defend his beliefs, or to respond to specific charges. Instead, Hus’s enemies had him tried before the Council of Constance as a follower of Wycliff and a heretic. Hus protested that he had not embraced all of Wycliff’s teachings— only those that were supported by scripture. He also maintained

that many of the teachings ascribed to him were actually not his beliefs but had been attributed to him by those who sought to discredit him. Hus agreed to recant only if his teachings were proven to be heretical by scripture. “On many doctrines Hus was as orthodox a Catholic as his contemporary accusers. He believed in purgatory and in a form of transubstantiation.”11 But his accusers had little interest in hearing his ideas or engaging in honest debate. “When he tried to argue his case, he was shouted down. Sigismund justified his violation of the safe-conduct by claiming Hus was a great heretic and deserved no protection.”12

On July 1, 1415, Hus once again stated that he could not recant his beliefs:

I, John Hus, in hope a priest of Jesus Christ, fearing to offend God and to fall into perjury, am not willing to recant all or any of the articles produced against me in the testimonies of false witnesses….If it were possible that my voice could now be heard in the whole world, as at the Day of Judgment every lie and all my sins should be revealed, I would most gladly recant before all the world every falsehood and every error I ever have thought of saying or have said.13

The Execution

Four days after this speech, the council ruled that Jan Hus was a “veritable and manifest heretic.”14 On July 6, 1415, executioners led Hus outside the city of Constance to the place of his execution. He was reported to have said, “You are now roasting a goose [the Bohemian word Hus means goose], but God will awaken a swan whom you will not burn or roast.”15

Hus was stripped of his clothes and had a crown placed on his head which depicted three devils. He was tied to a stake and as the executioners lit the fire and the flames surrounded him, Hus sang the Kyrie: “Christ, Thou son of the living God, have mercy upon us.”

Hus’ Legacy

After his death, the remains of Hus’s body were treated with deliberate disrespect. They were incinerated, along with his clothing and shoes, and the ashes were thrown into the Rhine River. The authorities apparently hoped to prevent any of his followers from obtaining relics. However, Hus’s death did not prevent the Bohemians from carrying on his legacy. He was now a martyr who inspired greater determination among those who shared his beliefs and who aroused the national feelings of the Czech people. The Hussite church continued on in Bohemia until the Hapsburgs conquered them in 1620 and forced the restoration of the Roman Catholic Church. Hus still remains a national hero there. Although Hus’s life was tragically and unjustly cut short, he is considered by many to be the leader of the first Reformation. He, like Luther, emphasized study of the scriptures, preaching, and correcting the abuses of the church hierarchy. His courageous life and words of faith resonate still today:

The Hussite church continued on in Bohemia until the Hapsburgs conquered them in 1620 and forced the restoration of the Roman Catholic Church. Hus still remains a national hero there.

“Oh most kind Christ, draw us weaklings after Thyself, for unless Thou draw us, we cannot follow Thee! Give us a courageous spirit that it may be ready; and if the flesh is weak, may Thy grace go before, now as well as subsequently. For without Thee, we can do nothing, and particularly not go to a cruel death for Thy sake. Give us a valiant spirit, a fearless heart, the right faith, a firm hope, and perfect love, that we may offer our lives for Thy sake with the greatest patience and joy. Amen.”16

Leah Fintel Krotz is pastor of Trinity Lutheran Church, LCMC, in Bruning, Nebraska. She received her undergrad degree from the University of Nebraska and her M.Div. from St. Paul Lutheran Seminary. She and her husband, Rick are the fifth generation to live on their family farm and love spending time with their children and grandchildren. She also serves as an ambassador for Hope 4 Kids International.

Notes:

1Ivor J. Davidson and Rudolph W. Heinze, The Baker History of the Church (Ada, Michigan: Baker Books, 2005), 89-90.

2“The Most Influential Man of the Millennium: Martin Luther Tops Secular Lists,” Generations: Passing on the Faith,” n.d., https://www.generations.org/programs/571.

3John D. Woodbridge and Frank A. James, Church History: From Pre-Reformation to the Present Day (Ada Michigan: Baker Academic,2013), 47.

4Timothy George, “The Reformation Connection.” John Hus: Apostle of Truth, February 3, 2023. https://johnhus.org/content/the-reformation-connection/.

5Davidson and Heinze, 65.

6Matthew Spinka and František M. Bartoš, “Jan Hus: Bohemian Religious Leader,” Encyclopedia Britannica, August 8, 2024, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Jan-Hus.

7Davidson and Heinze, 64.

8John Hus, The Church, translated, with notes and introduction by David S. Schaff, D.D. (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1915), viii.

9Spinka and Bartoš, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Jan-Hus.

10Ibid.

11Woodbridge and James, 48.

12Davidson and Heinze, 66.

13Woodbridge and James,. 49.

14Ibid., 49.

15Ibid., 50.

16Timothy George, https://johnhus.org/content/the-reformation-connection/.

THE SWORD OF THE REFORMATION

Mark Ryman

Fourteenth century England was witness to the birth of an odd assembly of men, “clothed with russet cloak, barefooted, and staff in hand,”1 though generally Oxford graduates. Although being men of letters, they had banded together with the common mission of preaching “a plain and simple Christian faith.”2 They were committed to taking the message of the cross of Christ to every town and village in Britain. One might expect these committed men of God to be welcomed in Christian England and Scotland. This was indeed the case, in that they were received well by the so-called common people. These regular folk were captivated by their message, for it was the Word of God in their own language instead of church Latin. Plain, simple, often uneducated people were eager to hear the plain and simple gospel in a language that did not require a university education. However, the established Church which used Latin, not English, was less than enthusiastic.

Common folk were able to hear these russet-robed Lollards (the followers of John Wyclif AD 1330–84, also spelled Wiclif, Wyclyf, Wycliff, and Wycliffe) read and preach the gospel

because they had translated the New Testament from Latin into English. Latin had been the lingua franca of the Roman Catholic Church even before Jerome created his translation of the Bible, the “Vulgate” (from the Latin word vulgata, meaning common, as in the common language), between AD 383 and 404. But it would not be until the Council of Trent (AD 1545–1563) that the Vulgate would become the official Bible of the Roman Catholic Church.3 A thousand years is a long time, during which an institution may become accustomed to doing things a certain way and not liking it when upstart priests, pastors, monks, and theologians begin reforming the status quo.

The Importance of Scripture in the Vernacular

Nonetheless, people like Wyclif and the Lollards knew that preaching the gospel to people who did not understand Latin meant the proclamation must be done in the language of the hearers. This might be manifest to those moved by the apostle’s words, “Forsoth wo to me, if I ʽschal not euangelise.”4 What would be the point of preaching or of reading the Bible aloud to a group if they could not understand what was being spoken? This is a question that still drives the Reformation forward today, even as it drove Martin Luther to translate the New Testament into common German in AD 1522. Arguably, had he not done so, the Lutheran Reformation might have fizzled out, for that is how important vernacular translations were and are for the

proclamation of the gospel, as we will realize in the last sentence of this article.

While numerous translations were written even after Jerome’s day into Latin, the 14th through 17th centuries saw an explosion of English translations by such divines as William Tyndale, Miles Coverdale, Thomas Matthew or John Rogers,5 and the 476 translators of the King James Bible. Yet there were others who were appalled by the same vision that Tyndale so aptly summed up: “I defy the Pope and all his laws; and if God spare my life ere many years, I will cause a boy that driveth a plough shall know more of the Scripture than thou doest.”7 That the ordinary person might hear the Bible in an understandable, common language was a shared concern of many even before the German or Lutheran Reformation came into focus in the early 16th Century.

Wyclif’s Czech Disciple: Jan Hus

Jan Hus8 (c. 1372–1415) was a Bohemian reformer who was eventually burned at the stake for heresy against Roman Catholic Church doctrine. Hus was “the first to preach in the vernacular…revis[ing] and improv[ing] existing Czech versions of the Bible, as well as writing biblical commentaries and translating Wycliffe’s writings.”9 The spread of the gospel and preReformation teachings were at stake, so the scriptures and the writings of Wyclif10 had to be translated from Jerome’s Latin and Wyclif’s Middle English, and ironically, later from Hebrew and Greek.11 Hus was a scholar “but as a reformer, [he upheld] the right of individual believers to read Scripture for themselves.”

How would they do so without the Bible in their own language? Hus not only translated the Bible and pre-Reformation writings into his national language,12 he also preached in Czech, drawing large crowds to hear him opine on topics of morality, corruption in the church, and the need for individual passion for the truth found in the Bible. These topics were not popular with the church establishment. Nonetheless, “Hus consistently asserted that it was more important to follow Christ and the Scriptures than the pope or tradition.”13

It should not be difficult to see how Hus’ writings influenced Luther.

“The story of Jan Hus reads almost like a dress rehearsal for that of Martin Luther a century later. Indeed, it was later said that Hus had told his executioner, ‘You are now going to burn a goose,14 but in a century you will have a swan which you can neither roast nor boil.’ Why did Hus fail where Luther would succeed? For one thing, Hus was not a great theologian: he wrote far less than Luther, and what he did write lacked the genius of the German Reformer. And the time simply was not right: in Hus’s day there was not yet the widespread dissatisfaction with Church practices with which Luther would later be able to connect.”15

Hus shares with Wyclif another reason that he was not of equal success to Luther. Hus and Wyclif both depended upon handwritten manuscripts to promulgate their writings. Johannes Wycliffite Bible

Gutenberg’s combination of a moveable metal-type printing press made the dissemination of Luther’s writings and those of other Reformers spread like wildfire, or in the modern parlance, go viral. Suddenly, his pamphlets, books, and broadsides were in the hands of everyone, and printed in their own language instead of church Latin. This was not the case for the pre-reformers who came before Luther. Not only did it take far longer to create just one hand lettered copy of the scriptures than to print thousands of copies on a press, but these translations were also banned by the church. “Despite the continued validity of the ban until the Reformation, the Wycliffite Bible became the most widely disseminated medieval English work, surviving in over 250 complete and partial copies.”16 Yet, these few copies that remain for us today may also indicate how a relative few were produced at all. The same might be said about Hus’ writings. The inescapable fact is that Luther may have been quite fortunate to have read Hus’ works at all because they were hand lettered and few in number.17 Yet clearly, they did make their way into Luther’s hands.

Hus’s Influence on Luther

In AD 1520 a year before Luther would stand trial at the Diet of Worms, the results of which inadvertently gave him time to produce his German New Testament by AD 152218—after having read some of Hus’s work, Luther wrote to Georg Spalatin, the secretary of Frederick the Wise, saying, “‘We are all Hussites without realizing it,’ including his confessor and superior Johann von Staupitz, Paul, and Augustine as “we.” Lucas Cranach

produced a woodcut showing Luther and Hus distributing communion in both kinds. Luther himself repeated Hus’ legendary words about an unknown future successor: “Now they roast a goose [hus in Czech], but in a hundred years they shall hear a swan singing, which they shall not be able to do away with.’ The parallels between the two reformers are significant…”19

It was even earlier when Luther was first influenced by Hus. “Early in his monastic career, Martin Luther, rummaging through the stacks of a library, happened upon a volume of sermons by Jan Hus, the Bohemian who had been condemned as a heretic. ‘I was overwhelmed with astonishment,’ Luther later wrote. ‘I could not understand for what cause they had burnt so great a man, who explained the Scriptures with so much gravity and skill.’”20

Luther may have been originally surprised by Hus’s positions in those early days of his monastic career, but the effects on him were long-lasting. Luther was so notably influenced by the life and writings of the Bohemian pastor that Martin the German was nicknamed “the Saxon Hus.”2 1 Hus also touched Luther in the realm of music. These words of Hus must have moved Luther: “We not only preach the gospel from the pulpit, but also by our hymns.” A search of Hymnary.org shows 17 titles by Hus; Luther penned 36 hymns.

Some of the writings of Hus found their way into Luther’s hands because a few of Hus’ books were some of the first works printed

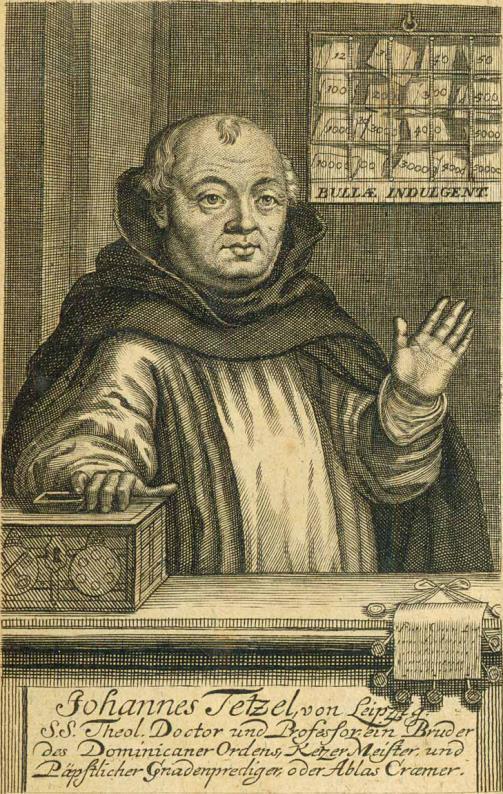

Johann Tetzel

on the new printing press. Lützow explains that, “It is a proof of the great fame of Hus that some of his writings were among the earliest of printed works.”22 “Martin Luther, who always considered the Bohemian reformer as his forerunner, in 1536 published at Wittenberg a translation of four of Hus’s Bohemian letters; among them was the famed ‘Letter to the Whole Bohemian Nation.’ The translation was in German and Latin. A year later a larger collection of Hus’s letters was printed under the influence of Luther, who wrote an introduction.”23 It is obvious that Luther believed Hus’ work important enough that it must be preserved so that others might benefit from his writings. The writings of Hus protested the selling of indulgences a hundred years before Pope Leo X commissioned Johann Tetzel to peddle his indulgences certificates in Wittenberg. Tetzel’s remission-mongering was the final straw pushing Luther to pen “The 95 Theses.” The question is: had Hus’ views against indulgences steeped in Luther for years until they were finally extracted from him in AD 1517?24

Another parallel to Luther’s life was the end of Hus’s own. The Roman Catholic Church demanded Hus recant his writings; he would not and was condemned. Luther too was commanded25 to recant his works but would not do so as it was not right nor safe and would sacrifice his conscience. For this, he too was condemned. The parallels between the two, and the influence of the former on the latter is undeniable. In fact, “Luther was accused of being a follower of Hus’s ideas (or a Hussite), with Luther not only admitting to that charge but boasting about it.”26

Would we boast the same? Would we even vaunt being Lutheran? If so, we would have good cause, for we have been

given reason and precedent. Semper reformanda (always reforming), a slogan that summarizes the spirit of the Reformation must be an ongoing principle in the church of the 21st Century. The idea must not be reformatio causa reformationis, reformation for the sake of reformation. Rather, the guiding principle must be that when the church departs from the Word by promoting the traditions of men over scripture, new reformers must always step up, promoting reform, despite the reaction of those in charge of any current state of affairs. This will almost certainly end in some sort of condemnation such as Wyclif, Hus, and Luther experienced, but it must be done for the sake of the Church of Christ.

True reform that is good and beneficial for the church happens best when another Reformation slogan is being observed. “Sola Scriptura” or scripture alone, is a focus, along with semper reformanda, that Wyclif and Hus would have embraced. Sola Scriptura does not rule out tradition, experience, or even reason, but it does not allow these to trump scripture. As such, the Bible, as the inspired Word of God, is viewed as the sole authority in matters of faith and practice. Reason will come into play, as will experience and tradition, but the final word on any matter is the Word. Even longstanding church traditions and doctrines must be evaluated against scripture and, when scripture dictates, they must be reformed or rejected outright.

Semper Reformanda and Sola Scriptura

This two-edged sword of Semper Reformanda

The Reformation continues only so long as faith may be received by the grace of God through a Word that is understood in one’s own tongue, for “faith comes from hearing, and hearing through the word of Christ.”

and Sola Scriptura are what the pre-reformers and the reformers have given us today. This gladius reformationis must be wielded with the same courage and devotion as those upon whose shoulders we stand. We may not be barefooted or plainly robed, but it is incumbant upon us to preach the plain and simple gospel as did the Lollards, Hussites, and Lutherans before us. We may not have a staff in hand, but the Bible must take its place. The Reformation continues only so long as faith may be received by the grace of God through a Word that is understood in one’s own tongue, for “faith comes from hearing, and hearing through the word of Christ.”27

Rev. Dr. Mark Ryman is married to Susan. He is pastor of St. Paul’s Lutheran Church in Salisbury, NC, and is happy to have received the D.Min. from St. Paul Lutheran Seminary.

Endnotes:

1John Charles Carrick. Wycliffe and the Lollards (New York: Scribner’s, 1908), 133.

2Ibid, 133.

3Bruce M. Metzger, The Early Versions of the New Testament (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1977), 348.

4John Wycliffe, The Holy Bible, Containing the Old and New Testaments, with the Apocryphal Books: Early Version, edited by Forshall, Josiah and Madden Frederic, vol. I–IV, Oxford: University Press, 1850). This is Wyclif’s, or his followers’ for there now is some debate about whether or not he actually completed the translation himself version of 1 Corinthians 9:16b: “Woe to me if I do not preach the gospel!” The Holy Bible: English Standard Version. (Wheaton, Illinois: Crossway Bibles, 2016), 1 Co 9:16.

5In 1537, John Rogers published The Matthew Bible under the pseudonym “Thomas Matthew.”

6King James had appointed 48 translators but one never showed up for work.

7Henry Worsley. The Dawn of the English Reformation: Its Friends and Foes (London: Stock, 1890), 69.

8Jan Hus is also known as John Huss. M. James Sawyer, The Survivor’s Guide to Theology (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2006), 507.

9John F. A. Sawyer, “Jan Hus,” A Concise Dictionary of the Bible and Its Reception, 1st ed. (Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, 2009), 116–17.

10“Most of what [Hus wrote] was little more than a paraphrase of the works of Wyclif… His skill lay in translating Wyclif’s ideas into an enormously popular movement through his own charisma and commanding presence.” (Jonathan Hill, The History of Christian Thought (Oxford: Lion Books, 2013).

11At the time of Wyclif’s translating, church Latin was so ubiquitous that it is arguable whether scholars were even aware of the original biblical languages. By the time of Luther, the English scholar Desiderius Erasmus (1466–1536) had to create a Greek New Testament in 1516 for the church to refer to, Luther using it in his own New Testament translation into German, despite his disagreements with Erasmus.

12The Moravian Church, formerly known as the Bohemian Brethren, has its roots in the teachings of Hus.

13Tom Schwanda, “Hus, Jan.” The Encyclopedia of Christianity, vol. 2. (Grand Rapids, Michigan: Eerdmans, 1999–2003), 617.

14In Czech, “hus” means “goose.”

15Jonathan Hill. The History of Christian Thought (Oxford, England: Lion Books, 2013), 169.

16Elizabeth Solopova, Jeremy Catto and Anne Hudson, From the Vulgate to the Vernacular (Berlin: De Gruyter, 2020), xv.

17However, as I state later, a few of Hus’ works were some of the earliest printed on presses.

18Because the diet, or assembly, ended with pronouncing anathema, or a formal curse, upon Luther, his life was forfeit. Anyone could assassinate him with impunity and likely with a purse for his effort. Luther’s Elector and benefactor, Frederick the Wise, had Martin kidnapped and hidden from the public at the castle in Wartburg. There, Luther spent eleven weeks translating the New Testament from Erasmus’ Greek New Testament into German, and years later he completed the entirety of the Bible, including the Apocryphal books, into contemporary, idiomatic German so that his countrymen could read the Holy Scripture.

19Paul W. Robinson, “Hus, Jan,” Dictionary of Luther and the Lutheran Traditions, edited by Timothy J. Wengert (Ada, Michigan: Baker Academic, 2017), 349.

20Mark Galli and Ted Olsen, “Introduction,” 131 Christians Everyone Should Know (Nashville: Broadman & Holman Publishers, 2000), 369.

21This is a moniker that Luther embraced.

22Francis Lützow, The Life & Times of Master John Hus (London: J. M. Dent & Sons, 1921), 291.

23Ibid., 291.

24AD 1517 is the year Martin Luther famously nailed his “95 Theses” to the castle door in Wittenberg. Even this, 500 years later, is now questioned as being legendary instead of historical. But the fact that Luther did write his theses and that they did quickly go viral throughout Europe is beyond question.

25Luther was commanded to renounce his writings by both the Church and the empire.

26Mark Nickens, A Survey of the History of Global Christianity, Second Edition (Nashville: B&H Academic, 2020), 89.

27Romans 10:17, ESV.

HYMN

“Wyclyf” by Mark E. Ryman

(May be sung to the tune: “Wycliff,” John Stainer - 1887)

Yorkshire raised a godly servant Of the risen Savior King. In his world of priestly favors Words of truth would once more spring.

Corrupt churchmen had no haven; Sanctuary comes by grace. Neither did the unrepentant Find in John a soft embrace.

For the word was his one compass And he would have all to read Those same words of revelation Unveiling thus their lives’ creed.

That Poor Preacher took the goose quill, Translating the ancient Greek Into common, vulgar English So God’s Word we all could speak.

Without Wyclyf you would not have Read the Book in your own tongue. So give thanks to God for Wyclyf; Let his praise be ever sung.

BOOK REVIEW

Martinez, Lauro. Fire in the City: Savonarola and the Struggle for the Soul of Renaissance Florence. Oxford University Press, 2007.

If you think the political climate is a little bit nuts these days, just check out late 15th century Florence with its power struggles, secret societies, inquisitions, and torture. Then add to the mix a little Dominican friar from Ferrara who claimed to be a prophet, told the city’s citizens to burn their valuables in a bonfire, and (spoiler alert) ended up getting burned himself! I guess 21st century America ain’t so bad after all.

Lauro Martines, former professor of European History at UCLA, has written this wonderful history of Girolamo Savonarola, which reads like a novel you can’t put down. Martines begins with the serpentine labyrinth of factions and government councils that made up perhaps the most democratic system of government in the world at the time. But the Florentines had a bigger problem than bureaucracy, one that would plague them for centuries, and that was the Medici family. But the city was enjoying a respite: the family had been expelled from the city and the Great Council (now representing the populo, the city’s middle-class citizens) was restored to its proper place in the government.

And yet shortly after the Medici’s demise, Florence had even a bigger problem: an advancing French army. Savonarola’s role in negotiating a settlement with Charles VIII saved the city

from destruction and solidified his position as the Florence’s kingmaker. An energetic advocate of the Great Council, he worked through intermediaries to defend the newly restored republican form of government. He also leveraged the power of the printing press: publishing his letters, sermons, and doctrinal works in Latin (and at times, perhaps more importantly for its impact on the populace, in Italian). He was the most published Italian author of the late 15th century.

In the decades before, Savonarola had made a name for himself as an A-list preacher who was invited to preside in many of the great cities of Italy. Lorenzo the Magnificent, still in power, was convinced by a friend to invite the friar to move to Florence permanently. Preaching first at his Dominican church of San Marco during Advent 1490, he was then invited the following year to preach at the city’s famous Duomo. Savonarola used these sermons as an opportunity to rail against the corruptions of the church: pluralism, simony, concubinage, and even sodomy. Martines describes the engaging style that the friar used, often entertaining, and then refuting an imaginary opponent’s accusations. For instance, in one sermon he counseled, “Do what I’ve said. Carry out the reform of morals or Christ will do it for you.” The imaginary opponent replies, “O friar, are you supposed to command us?” Savonarola responds, “No I am not here to command you, but Christ is king of this city, and I am his ambassador.” If this were the extent of his messages, one

might commend him on his wit and the power of his persuasion. But sadly, Savonarola went even further, claiming that he was indeed a prophet: “Christ speaks through my mouth,” he asserted.

But where Savonarola succeeded, at least for time, was in cleaning up public morals. He reorganized of the city’s confraternities for boys, organizing them under the four municipal districts and then allotting them a major role in turning Florence into a city of God. Part of this effort involved changing the festival of Carnival into a Christian celebration. During the week before Ash Wednesday, the boys went door to door asking residents for “vanities,” such as playing cards, cosmetics, or dirty books that would then be thrown upon the bonfire during the festivities.

Surprisingly, all these efforts only raised Savonarola’s popularity, and Machiavelli, who lived in the city during these years, later wrote that most of city did indeed believe that he was a prophet. And yet as Savonarola’s disciples multiplied, so did his detractors, which including perhaps the most corrupt pope of all time, Alexander VI. A member of the notorious Borgia family, Alexander was rumored to have assassinated the bishop of Cefalù in 1484, and he openly recognized his mistresses and illegitimate children at the papal palace.

The pope had a number of beefs with the friar. First, he was disappointed that Savonarolan Florence would not align itself with other Italian states in the Holy League fighting against the hegemony of France. Secondly, he sought to reorganize the Dominican houses, a program that would place San Marco under Roman control, a move Savonarola and his friars vehemently opposed. And thirdly, and perhaps most legitimately, the pope

was concerned with Savonarola’s claim that God actually spoke to him, and he ordered him to stop preaching. The friar’s disobedience resulted in his excommunication on May 13, 1497.

Think all this sounds a little chaotic? Well, just wait because guess who’s at the city gate – its Piero de’ Medici, and he’s brought an army! But due to torrential rains and mixed signals with his conspirators inside the walls, the coup fails, and he must retreat back to Siena.