SIMUL

Uses of the Law – 2 or 3?

Vol.1,Issue4

Summer2022 TheJournalofSt.PaulLutheranSeminary

SIMUListhejournalofSt.Paul LutheranSeminary.

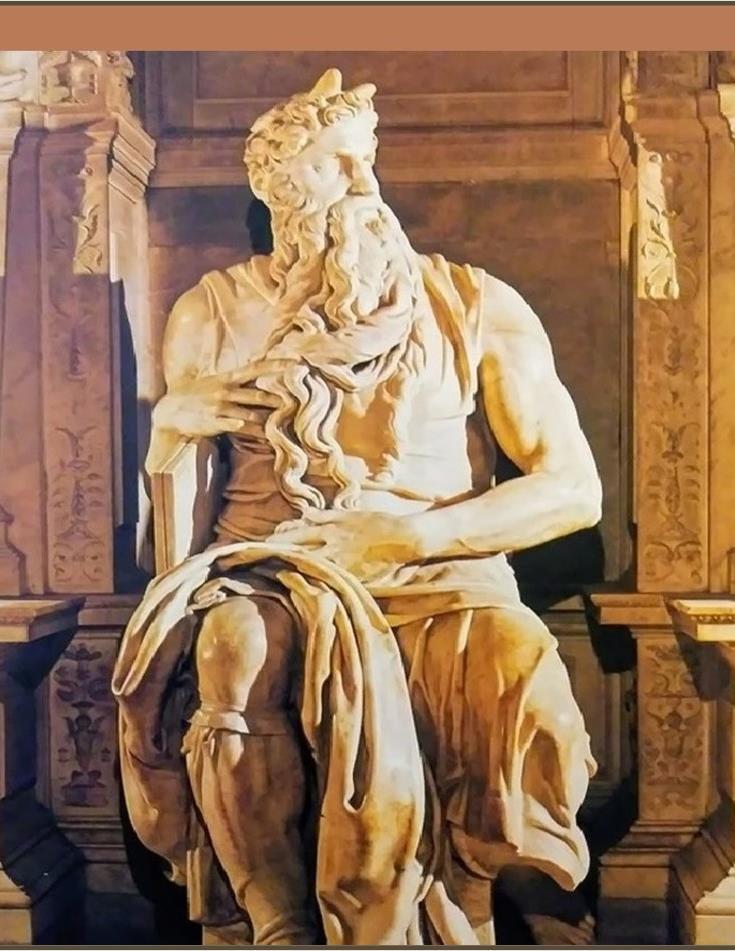

CoverPhoto

This issue’s cover photo is Michelangelo’s“Moses” (1505)

Disclaimer

The viewsexpressedinthe articlesreflectthe author(s) opinionsand arenotnecessarilythe viewsofthe publisherand editor.SIMULcannotguaranteeand acceptsnoliabilityforany lossor damageofanykind causedby the errorsandfor theaccuracy ofclaims made by the authors.Allrightsreservedand nothingcan bepartiallyorinwholebereprintedor reproduced withoutwrittenconsentfrom the editor.

SIMUL

Volume 1, Issue 4, Summer 2022 Uses of the Law – 2 or 3?

EDITOR

Rev. Dr. Dennis R. Di Mauro dennisdimauro@yahoo.com

ADMINSTRATOR Rev. Jon Jensen jjensen@semlc.org

Administrative Address: St. Paul Lutheran Seminary P.O. Box 251 Midland, GA 31820

ACADEMICDEAN Rev. Julie Smith jjensen@semlc.org

Academics/Student Affairs Address: St. Paul Lutheran Seminary P.O. Box 112 Springfield, MN 56087

BOARD OFDIRECTORS

Chair: Rev. Dr. Erwin Spruth Rev. Greg Brandvold Rev. Jon Jensen Rev. Dr. Mark Menacher Steve Paula Rev. Julie Smith Charles Hunsaker Rev. Dr. James Cavanah Rev. Jeff Teeples

TEACHINGFACULTY

Dr. James A. Nestingen Rev. Dr. Marney Fritts Rev. Dr. Dennis DiMauro Rev. Julie Smith Rev. Virgil Thompson Rev. Dr. Keith Less Rev. Brad Hales Rev. Dr. Erwin Spruth Rev. Steven King Rev. Dr. Orrey McFarland Rev. Horacio Castillo (Intl) Rev. Amanda Olson de Castillo (Intl) Rev. Dr. Roy Harrisville III Rev. Dr. Henry Corcoran Rev. Dr. Mark Menacher Rev. Dr. Randy Freund

SIMUL SIMUL| Page 2

SIMUL

Volume 1, Issue 4, Summer 2022 Uses of the Law – 2 or 3?

Table of Contents

Editor’sNote 4 Rev.Dr. Dennis R. Di Mauro

Letters 7 TheLaw’sThirdUse-AreYouFeeling RejectedandCondemned? 12 Rev.Dr. Mark Menacher

AnExplorationintotheThirdUseofthe Law:ABiblicalMeditationand TheologicalInquiry 27 Rev.Dr. Henry A. Corcoran

TheUsesoftheLaw–2or3?APastoral Perspective 38 Rev.Dr. James L. Cavanah

RevisitingtheThirdUseoftheLaw,Again 52 Rev.John W. Hoyum

BookReviews: PeterLeithart’sTheTen CommandmentsandGilbertMeilaender’s ThyWillBeDone 64 Rev.Dr. Joshua Hollmann

3

Editor’s Note

Welcome to our fourth issue of SIMUL, the journal of St. Paul Lutheran Seminary. This edition will discuss the uses of the law, and whether there are two or three of them.

In this issue, Mark Menacher starts us off with a theological review of the origins of the three uses, Henry Corcoran looks at the topic through the lens of Ignatian spirituality, Jim Cavanah takes a pastoral look at the law’s application in the parish, and John Hoyum closes us out by advocating a fidelity to the confessions, even by those who would reject article six of the Formula of Concord.

Our Theological Conference

This issue will discuss the uses of the law, and whether there are two or three of them.

This past April, we had an amazing conference in Jekyll Island, GA. For those who have never been there, Jekyll Island was a hunting and beach club for the rich and famous in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, and its membership included members of the Vanderbilt, Rockefeller, Pulitzer and Goodyear families. Today, the club is a beautifully renovated beach resort.

4

SIMUL

Jekyll Island Club

This year’s conference featured Dr. Marney Fritts, who spoke on Luther’s two kingdoms theology, and Rev. Julie Smith, who explained how to read the Bible by properly distinguishing law and gospel. Mark Ryman introduced his new visual catechism, and Steve King gave a presentation on a new update of the old Crossways material. The updated Crossways resources are available from Sola Publishing, and you can contact Mark Ryman about the visual catechism at revryman@gmail.com I also provided a hands-on demonstration on how to access and read SIMUL online.

So please mark your calendar for next year’s conference, also at the Jekyll Island Club, April 11-12, 2023. The speakers include Rev. Brad Hales, Rev. Julie Smith and others to be announced.

What’s New?

Letters - We are now including a letters section for those who would like to comment on any of our articles. If you would like to send a letter to the editor for possible publication, you can email it to me at dennisdimauro@yahoo.com

Book Reviews - We also seek to include a book review or two in each issue. As you can see, Josh Hollman has written wonderful reviews of two works by Peter Leithart and Gilbert Meilaender for this issue.

What’s Ahead?

Upcoming Issues - We are so excited about this coming year.

5

SIMUL

Our Fall 2022 issue will cover the sacraments, a topic which has come under much discussion during the COVID-19 shutdowns. Our Winter 2023 issue will be on renewal in the local church, responding to Bradley Hales very successful class of the same title which had over one hundred students representing twenty-two different churches. Luther’s theology of vocation will be the subject of our Spring 2023 issue.

India Classes – St. Paul Lutheran Seminary has partnered with the Lutheran School of Theology in India to provide education for their pastoral candidates – they had eleven students in their first graduating class! Unfortunately, we have no funding for our American professors, and they have been providing their services pro bono. While their generosity has kept the classes going for the time being, this situation is sadly unsustainable. If you would like to support our commitment to educating Indian pastors for ministry, please consider making a generous contribution at https://semlc.org/support-st-paul-lutheran-seminary/

I hope you enjoy this issue of SIMUL! If you have any questions about the journal or about St. Paul Lutheran Seminary, please shoot me an email at dennisdimauro@yahoo.com

contribution.

Rev. Dr. Dennis Di Mauro is the pastor of Trinity Lutheran Church in Warrenton, VA. He teaches at St. Paul Lutheran Seminary and is the editor of SIMUL.

6

SIMUL

If you would like to support our commitment to educating Indian pastors for ministry, please consider making a generous

LETTERS

To the Editor:

John B. King’s “pronomian model” for mixing the two kingdoms, “Toward a Conservative Lutheran Social Ethic,” vol. 1, Issue 3 (Spring 2022), is the very antithesis of Reformation Lutheran theology. It is an imagined “Lutheran social ethic” being contrary to St. Paul’s teaching that no one is pronomian, no one loves the law, no one is moral or ethical. Paul writes, “No one is righteous, no, not one; no one understands, no one seeks for God. All have turned aside, together they have all gone wrong; no one does good, not even one” (Romans 3:1012, RSV). “Using the law as an ethical standard” totally undermines the gospel and is the very definition of free will. If we can be pronomian, who needs Christ? “Christ is the end of the law” (Romans 10:4, RSV).

His assertion that “a separation of church and state does not entail a separation of Bible and state,” shows his unfamiliarity both with Luther’s Sachsenspiegel and Article XVI of the Apology which states, “The gospel does not legislate for the civil estate,” is not “something external, a new and monastic form of government,” but only “brings eternal righteousness to hearts, while it approves the civil government.”

7

SIMUL

Luther underscored the point to Robert Barnes in 1531 on the question of applying biblical law to the secular court of Henry VIII. “If we are forced to observe one law of Moses, then by the same reason we also ought to be circumcised, and ought to observe the whole law, as Paul argues in Galatians 5. Now, however, we are no longer under the law of Moses, but are subject in these matters to the laws of the state” (LW 50.34). That is, we interact with the state via our civitas, not as Christians.

Luther further declared the mixing of the two kingdoms to be demonic alchemy, saying in his exposition of Psalm 101, “Constantly I must pound in and squeeze in and drive in and wedge in this difference between the two kingdoms, even though it is written and said so often that it becomes tedious. The devil never stops cooking and brewing these two kingdoms into each other. The false clerics and schismatic spirits always want to be the masters, though not in God’s name, and to teach people how to organize the secular government. Thus the devil is indeed very busy on both sides, and he has much to do. May God hinder him, Amen!” (LW 13.194-195)

Günther Bornkamm rightly warned, “Once the message of justification has been displaced from the middle and has sunk to becoming a matter of course and a concern of pious inwardness, the search begins for a metaphysical foundation for political service, a general synthesis of the kingdom of Christ and the empire, and the myth of the world-ruler reappears in Christian form, albeit as a bad copy. But Jesus Christ does not let himself be subjected to this metaphysical alliance with

8

SIMUL

Caesar. Therefore, the question to the church is especially this: whether it decides, as the Apostle Paul, to know nothing other than Jesus Christ, the crucified (1 Cor. 2:2); that means to deliver the word of reconciliation, and nothing else.” (Early Christian Experience, p. 24-25).

9

SIMUL

Pastor Kristian Baudler St. Luke’s Lutheran Church of Bay Shore, NY and Prince of Peace Lutheran Church, Brentwood, NY

Dr. King Responds…

Pastor Baudler takes issue with my central claim that Christians should use God’s law as a norm for judging and formulating public policy. In response, let me begin with a concrete example to illustrate my thesis. In terms of public policy, I believe that abortion is the unlawful killing of an innocent child and is thus prohibited by the fifth commandment against murder. For this reason, I further believe that Christians should use every legal means to make abortion illegal. Does Pastor Baudler believe this too? Would Martin Luther believe this? He seems to think that Luther would not. To this end, he quotes Luther as saying that to use even one commandment would put the state under the entire Mosaic law. However, this is not what Luther says in the Large Catechism: This much is certain: those who know the Ten Commandments perfectly know the entire Scriptures and in all affairs and circumstances are able to counsel, help, comfort, judge, and make decisions in both spiritual and temporal matters. They are qualified to be a judge over all doctrines, walks of life, spirits, legal matters, and everything else in the world (LC, Preface, 17).

Baudler also accuses me of mixing the two kingdoms, even though I take pains to separate them along institutional lines. Against me he quotes Article XVI of the Apology, “The gospel does not legislate for the civil estate. . .” However, this proves nothing since Melanchthon believed that civil law already

10

SIMUL

embodied the Decalogue through natural reason (AP, IV, 7, 8, 34).

He further states that using the law as an ethical standard is the very definition of free will. But he fails to notice that I use the law as a standard of civil righteousness, not as a basis for works-righteousness. If memory serves me correctly, civil righteousness is something of which we are capable. Baudler reminds us that Christ is the end of the law. However, since Christ’s kingdom has not yet dawned in its eschatological fullness, we still need civil laws to preserve order. Why then can’t we use the fifth commandment to stop the slaughter of unborn children?

Finally, Baudler’s approach is both antinomian and legalistic since he turns the gospel into a negative law (legalism) that prevents us from using God’s law for ethical purposes (antinomianism).

11

SIMUL

THE LAW’S THIRD USE

ARE YOU FEELING REJECTED AND CONDEMNED?

Mark D. Menacher, Ph.D.

Introduction

The Confessions of the Evangelical Lutheran Church, generally known as the Book of Concord (BoC) in English, conclude with the Formula of Concord (FC). The FC is composed of two parts, the Epitome (Ep) and the Solid Declaration (SD).1 As the names imply, the FC and the BoC were written and compiled, respectively, then published in 1580 to bring concord within Lutheran lands between contending parties whose doctrinal differences after Martin Luther’s death in 1546 threatened Lutheranism itself. By and large, the BoC and the FC have accomplished their task. Unfortunately, Ep Article VI and SD Article VI regarding the “third use of the law” have not been so successful, especially in recent decades. Why might this be the case, and why is it important for both parishioners and pastors?

If you do not know what the law’s “third use” is or, worse,

12

–

SIMUL

do not regard it too highly, the consequences are harsh. Ep VI.8 concludes, “Accordingly we condemn as dangerous and subversive (schädlich) of Christian discipline and true piety the erroneous teaching (widerwärtige Lehr und Irrtumb) that the law is not to be urged (getrieben), in the manner and measure above described, upon Christians and genuine believers, but only upon unbelievers, non-Christians, and the impenitent.” Similarly, SD VI.26 states, “Hence we reject (verwerfen) and condemn (verdammen), as pernicious (schädlich) and contrary to discipline and true godliness, the erroneous doctrine (nachteiligen Irrtumb) that the law in the manner and measure indicated above is not to be urged upon Christians and true believers but only upon unbelievers, non-Christians, and the unrepentant.” Because not teaching the “third use of the law” is “dangerous and subversive,” to be “rejected and condemned,” those failing to do so frequently face the same fate. To paraphrase the catechism, what does this mean?

References to the law’s use (usus), application (Gebrauch), or office (officium) are routinely employed by Luther. According to Luther, God

“Hence we reject (verwerfen) and condemn (verdammen), as pernicious (schädlich) and contrary to Christian discipline and true godliness, the erroneous doctrine (nachteiligen Irrtumb) that the law in the manner and measure indicated above is not to be urged upon Christians and true believers but only upon unbelievers, nonChristians, and the unrepentant.”

13 SIMUL

uses the law to address human sin in two ways. The “first use,” often called the political or civil use (usus politicus, usus civilis), reflects God’s efforts to protect sinful human beings from each other and from themselves through civil government and laws. Through the “second use,” known as the theological or spiritual use (usus theologicus, usus spiritualis), which is effected through the church’s preaching and teaching, God reveals sin, thereby terrifying consciences and humbling sinners, in order to drive them to Christ.2 When Christ and his gospel are then proclaimed to such terrified consciences and when Christ’s promises invoke and evoke the faith alone in Christ by which these same sinners are justified, “we are freed from the law, sin, death, and all evils and are made partakers of grace, righteousness, and life, and then are appointed lords of heaven, of earth, and of all creatures. The law is added over reason in order that it might illuminate and aid a human being and might show him what he ought to do and to omit.”3 For Luther, this addition of the law does not represent a “third use” but rather reflects the function of the law within its two divinely established uses. “In true theology,” according to Luther, “this is effected first, that a human being is to become good through the regeneration of the Spirit, who is a sure, holy, and bold Spirit. Then, as from a good tree, it happens that good fruit also sprouts forth.”4 These good works as good fruit are not coerced but follow faith voluntarily (sponte).5

14 SIMUL

Luther

The Third Use

The concept of a “third use” of the law was formulated in the wake of the First Antinomian Controversy6 by Philip Melanchthon, who arguably was Luther’s right-hand man. Beginning in 1527, another close associate of Luther, Johann Agricola, began to contest Melanchthon’s understanding of Luke 24:47 “that repentance and the forgiveness of sins should be preached in [Christ’s] name to all peoples, beginning from Jerusalem.” Agricola asserted that both repentance and the forgiveness of sins were affected by the gospel without any use of the law. Agricola and his followers were subsequently branded as “antinomian” (from anti + nomos in Greek meaning “against the law”).

Luther and Melanchthon responded differently to Agricola’s dissolution of the distinction between law and gospel. Between December 1537 and September 1540, Luther published six series of theses in four Disputations against the Antinomians, 7 a theological tour de force. Melanchthon countered by adding more law to the 1535 edition of his Loci Communes, which he initially described as a “third office” of the law (tertium officium legis),8 later adding the term

15 SIMUL

Melanchthon

“threefold use” of the law (triplicex usus legis). In Melanchthon’s scheme, with the “first use” (usus paedagogicus or politicus) God wants to restrain (coercere) all human beings from committing outward sins. In the “second use,” God wants to show sin, accuse, terrify, and condemn all human beings for their corrupt nature, and to demonstrate the need for repentance. The “third use” is applied to the regenerate or the reborn (usus in renatis). According to Melanchthon, although the regenerate are free from the law, nonetheless the law must be preached to teach them so that they might exercise obedience towards God.9

A Speed Limit

Perhaps an example will help clarify these concepts. Think about a speed limit sign. The sign represents one law with three uses. The first use, drafted by civil politicians, is established to protect human beings from speeding and thus potentially endangering their lives and the lives of others. Second, when used in conjunction with a vehicle or roadside speedometer, the same sign “shows,” “accuses,” and “condemns” speeders, revealing that they are corrupt and should repent by slowing down. Third and finally, that same sign tells those reborn in Christ not only that it is God’s will for them to observe the speed limit but also that doing so is pleasing to God.

So, when was the last time that you observed any “speed limit” with the dual goal of being obedient and pleasing to God? Furthermore, when was the last time that such

16 SIMUL

adherence to “speed limits” was preached to you by a Lutheran pastor? Finally, when was the last time any “speed limit” sign at any time exercised any inherent power to oblige you to comply? Viewed another way, despite the energy invested in defining and debating its various uses, the law is inherently impotent.10

After Luther

When Martin Luther died on 18 February 1546, the Reformation within the Lutheran fold fell quickly into disarray. By June 1546, the Pope and the Emperor had entered into a pact to attack the Lutheran lands and to force them to return to the papal church. Against such a threat, years before the Lutheran territories had organized themselves into an alliance called the Smalcaldic League after the town of Smalcald, Germany where the agreement was drafted. Due to disunity and betrayal among some of the Protestant princes, the emperor quickly won what is now called the Smalcaldic War in late May 1547. Earlier in May 1547, Wittenberg itself was occupied, and the university was temporarily closed. In May 1548, the Emperor mandated interim arrangements to “re-papalize” the conquered Lutherans in preparation for the implementation of the final decisions of the recently convened Council of Trent. This edict became known as the “Augsburg Interim” after the city where it was decreed. Unfortunately, along with his many other failings during this period, Philip Melanchthon refused to

17 SIMUL

Emperor Charles V

speak against the Interim publicly.11

Due to these events, a considerable theological vacuum developed in Wittenberg and many controversies arose, one of which is known as the Second Antinomian Controversy. Despite the peaceful coexistence of Luther’s and Melanchthon’s differing delineations of the law, in the 1550s former students favorable to one side (Genesio-Lutherans) or the other (Philippists), respectively brought Luther’s duplex and Melanchthon’s triplex uses of the law into conflict.12

Because the former rejected a “third use” of the law, they were also dubbed “antinomians,” although in light of the Eighth Commandment perhaps “two-thirdsnomians” would be more accurate. To make matters worse, some Philippists started to espouse antinomian positions similar to Agricola.13 To resolve these and many other controversies among Lutheran factions, the concordists compiled the Book of Concord and formulated the Formula of Concord hoping to ensure that such discord would remain just an “interim” moment of chaos. Unfortunately, in relation to Ep VI and SD VI such concord has remained elusive.

So, do you find that you are not always observing the speed limit “from a free and merry spirit” (SD VI.17)? Does the Old Adam in you sometimes have you speeding despite the threat of a ticket to coerce compliance

To resolve these and many other controversies among Lutheran factions, the concordists compiled the Book of Concord and formulated the Formula of Concord hoping to ensure that such discord would remain just an “interim” moment of chaos.

18 SIMUL

(SD VI.18)? Do you sometimes think that going even one mile per hour under the speed limit makes you somehow virtuous or even holy (SD VI.20.21)? Are you aware that not knowing the difference between the first, second, or third use of the law is no excuse (ignorantia juris non excusat)? Wittingly or unwittingly, should any or all of the above necessarily make you dangerous and subversive (Ep VI.8), to be rejected and condemned (SD VI.26), especially by fellow Lutherans gesticulating profusely or profanely at you in your rearview mirror? In other words, is Article VI of the FC the touchstone of being faithfully and confessionally Lutheran?

Contrary to passing perceptions, the answer is not straight forward. The numerous, various, and even valiant attempts by confessionally-minded theologians to find a “third use” of the law in Luther’s theology or to marry Lutheran terminology with Melanchthonian methodology or to interpret FC VI Christologically in the hope of complying with Ep VI and SD VI, would be not only superfluous but non-existent if concord had been adequately formulated in the FC regarding Lutheran uses of the law.

Again, what does this mean? First, when the concordists included Luther’s Smalcald Articles (SA) and the FC in the same corpus of confessional writings, they (presumably unintentionally) codified discord into the Book of Concord. In SA III.II “The Law,” Luther describes only two uses: (1) “Here we maintain that the law was given by God first of all to restrain sins by threats and fear of punishment and by the

19 SIMUL

promise and offer of grace and favor. But this purpose failed (ubel geraten - fell afoul) because of the wickedness which sin has worked in man, ...” (SA III.II.1), and (2) “However, the chief function or power of the law is to make original sin manifest and show man to what utter depths his nature has fallen and how corrupt it has become, ... that he neither has nor cares for God or that he worships strange gods, ... [and] is terrorstricken and humbled, ..., etc.” (SA III.II.4). In contrast, following Melanchthon’s theology, the concordists in Ep VI.1 and SD VI.1 prescribe three uses: (1) “to maintain external discipline against” ... “disobedient men/people,” (2) “to lead men / bring people to a knowledge of their sin through the law,” and (3) “to give [the reborn] ... a definite rule according to which they should pattern and regulate their entire life” that “those who have been born anew through the Holy Spirit, ... [can] learn from the law to live and walk in the law.” The Ten Commandments show the regenerate “what the acceptable will of God is (Rom. 12:2) and in what good works, which God has prepared beforehand, they should walk (Eph. 2:10)” (SD VI.12.21). Consequently, on one hand the FC itself not only considers Luther to be the foremost teacher (doctor) in the churches of the Augsburg Confession but also considers his doctrinal and polemical writings to provide the true understanding and meaning of the Confessio Augustana (CA),14 which Lutherans confess

20 SIMUL

Augsburg Confession

to be founded on God’s word (holy scripture) as a pure, Christian symbol.15 On the other hand, the “third use” of the law in Ep VI.1 and SD VI.1 only appears to build upon Luther’s two uses found in the SA. In reality, however, because Luther only teaches two uses of the law, his teaching in the SA and in his “other doctrinal and polemical writings” cannot escape being rejected and condemned for being “dangerous and subversive” (Ep VI.8), as being “pernicious and contrary to Christian discipline and true godliness” (SD VI.26). That is the law in FC VI, but which use is that exactly?

Using Different Language

Second, whereas Luther and Melanchthon (and the concordists) may appear to be using the same language because they often cite the same biblical passages, due to Melanchthon’s divergence from Luther’s biblically based theology in favor of his own humanist, Aristotelian oriented approach,16 their similar language masks substantial differences. According to the FC, the “converted are freed through Christ from the curse and coercion of the law, ...” and “have been redeemed by the Son of God precisely that they should exercise themselves day and night in the law” (Ep VI.2). Likewise, “when a person is born anew by the Spirit of God and is liberated from the law (that is, when he is free from this driver and is driven by the Spirit of Christ), he lives according to the immutable will of God as it is comprehended in the law...” (SD VI.17). For Melanchthon and the concordists, the law mediates the relationship between God and human beings, and Christ is reduced to reconciling fallen humanity

21 SIMUL

with God by restoring them to and reinstating them in God’s eternal, immutable law.

For Luther, by contrast, if one collects “all the wisdom of Moses, the Gentiles, [and] the philosophers, ... you will discover that before God (coram deo) these are either idolatry or feigned wisdom or, in the political sphere, a wisdom of wrath.”17 “This is because Christ is Lord of the law, to whom the people, the father’s house, and the universal law must submit. That is so because the law has been delivered by servants. Now, however, the Lord himself, the king and God, is present.”18 “Christ, then, is not a servant but the Lord Himself; not the Mediator between God and humanity according to the law, as Moses, but he is the mediator of a better Testament.”19 Because of Christ the gospel is eternal.20 Therefore, Luther admonishes here to differentiate between the Giver and the gift. God has given many gifts, like Moses, the law, etc., but incomparably to those, God, the Giver, has given himself in Christ. Consequently, everything must yield to Christ as Lord of all, including the law.21

Luther Left Out?

Finally, the strength of the FC’s assertions regarding the centrality of the law in the economy of salvation seems to rest upon the notion that the law as the expression of God’s will is not only eternal but unchangeable/immutable (unwandelbarEp VI.6, SD VI.3.15.17). The “word ‘law’ here has but one meaning, namely, the immutable will of God according to which man is to conduct himself in this life” (SD VI.17). This

22 SIMUL

seems to reflect Melanchthon’s view that the “divine order remains unchangeable” (manet immutabilis ordinatio divina).22 So conceived, the “third use” of the law found in FC VI seems unassailably established. Unfortunately, the concordists do not seem to have taken the foremost doctor in the churches of the Augsburg Confession into account. As Luther proclaims in relation to John 6:38-39,

This is a new sermon from which we want to learn what the Father’s will is and how one might do God’s will. The papists have said that God’s will is to keep his commandments. They mingle everything together and relate God’s will to good works. ... Therefore [Christ] speaks here about another will of God the Father, which pertains greatly to other matters and which is a will other than keeping the Ten Commandments or preaching the law. For the blind leaders, the papists, have invented it in their heads and purported that it is God’s will to keep God’s Commandments. They have inserted faith into the law, entirely mingled them together, and then shoved their notions and dreams into this text. They persist in this and refer to God’s Commandments as the divine will. Therefore, one should let them take a hike. ... All that [regarding the law] is his will, but how

23 SIMUL

“They have inserted faith into the law, entirely mingled them together, and then shoved their notions and dreams into this text.”

much of that is of his will? For here he does not speak of that at all, but instead here he deals with the right will of God, the heavenly Father, which does not pertain to the Commandments and the law; to wit, “Whoever believes in the Son shall not perish but have eternal life” [Jn 3:16]. Therefore, you also must not mingle these wills one in the other but [must] speak thereof as Christ himself does and as the text here states. Now, it is another article, yes, another thing than when one says, “Honor your parents.” Here he speaks of another will, and you must not brew and stew (brewen und kochen) one in the other. ... For as Christ also says in another place, “This is the will of him who has sent me, that whoever sees the Son and believes in him will have eternal life, and I will raise him up on the last day” [Jn 6:40]. That certainly does not mean to shove away from himself but to keep close by himself. That is another will entirely from the one which the law demands of us. One must separate such wills of God from one another.23

As Luther reminds, “[W]hoever knows well how to discern the gospel from the law should give thanks to God and know that he is a theologian.”24 In contrast, for Luther, “stewing and brewing” (kochen und brewen) God’s domains together is the devil’s work.25 The failure to differentiate gospel from the law, and the readiness to brew and stew God’s two wills together in Article VI of the Formula of Concord has, does, and will continue to create discord among Lutherans, to the devil’s

24 SIMUL

delight. So, the next time that you see a fellow Lutheran gesticulating profusely or profanely at you in your “third use” rearview mirror, keep in mind that God wills there to be no condemnation for those who are in Christ Jesus (Rom. 8:1).

Rev. Dr. Mark Menacher is Pastor of St. Luke’s Lutheran Church, La Mesa, California

Endnotes:

1See The Book of Concord, ed. Theodore G. Tappert (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1959), 464-636 (hereafter as BoC). References to the Epitome and Solid Declaration are by article and paragraph(s), i.e. VI.1. See also Die Bekenntnisschriften der Evangelisch-Lutherischen Kirche, 9th edition (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1982), 735-1100 (hereafter as BSLK).

2Cf., D. Martin Luthers Werke - Kritische Gesammtausgabe (Weimar: Hermann Böhlau, 1883-2009), 40,1:528,6-20 [hereafter as WA]. Unless otherwise stated, translations are the author’s. Corresponding references to the same material where existent are cited from Luther’s Works, American Edition, 55 vols., editors, J. Pelikan and H. Lehmann (Saint Louis: Concordia Publishing House and Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1955), 26:343-344 [hereafter as LW].

3WA 40,1:306,13-18 = LW 26:183-184. “Moreover, the spirit is freedom (libertas) from law, sin, death, curse, hell, wrath, and judgement of God, etc.” WA 40,1:455,35-36 = LW 26:293. Also, WA 40,1:672,18-21 = LW 26:447, “This is not because the conscience does not experience terrors of the law. Certainly, it experiences them, but in such cases the former cannot be condemned and driven to despair, because ‘now there is no condemnation for those who are in Christ Jesus,” (Rom. 8:1); likewise, “if the son has set you free (liberaverit), you will be truly free (liberi),” (John 8:36).” For Luther, freedom in Christ is not a theological category but an existential reality as exemplified by changing his surname’s spelling from Luder to Luther to reflect the theta (θ = th) in the Greek word ἐλεύθερος (eleutheros) meaning “free,” see Bernd Moeller and Karl Stackmann, “Luder–Luther–Eleutherius: Erwägungen zu Luthers Namen,” in Nachrichten der Akamemie der Wissenschaften in Göttingen. I. Philologisch-Historische Klasse, (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1981).

4WA 40,2:433,28-31 = LW 12:385.

5WA 39,1:46,28-30 = LW 34:111.

6Cf., Friedrich Bente, Historical Introductions to the Book of Concord (St. Louis, Missouri: Concordia Publishing House, 1965), 161-171 [hereafter Bente].

25 SIMUL

7

Cf., Bente, 163-168. For an excellent Latin-English compendium of Luther’s theses against the antinomians, see Holgar Sonntag, Solus Decalogus est Aeternus - Martin Luther’s Complete Antinomian Theses and Disputations (Minneapolis: Lutheran Press, 2008). N.B. Sonntag’s editing deviates from the presentation of the same in WA 39,1:359-584 and WA 39,2:122-144.

8Loci communes theologici recens collecti et recogniti in Libri Philippi Melanthonis, Corpus Reformatorum, volume 21, ed. C.G. Bretschneider and H.E. Bindseil (Brunswick, 1854), 406 [hereafter as CR].

9CR 21:717-719.

10See Gerhard Ebeling, Luther - Einführung in sein Denken, fourth edition (Tübingen: J.C.B. Mohr [Paul Siebeck], 1981/1990), 140-141.

11Bente, 93-99.

12Bente, 169-171.

13Bente, 171-172.

14BSLK, 983,34; 984,41 = BoC 575,34; 576,41.

15BSLK, 45,8; 830,4 = BoC, 25,8; 502,4.

16Cf., James A. Nestingen, “Changing Definitions: The Law in Formula VI,” Concordia Theological Quarterly 69 (2005), 259-270, especially 264-265.

17WA 40,2:489,38 - 490,16-17 = LW 12:210.

18WA 40,2:584,19-21 = LW 12:280-281.

19WA 40,1:494,30-32 = LW 26:319.

20WA 40,1:494,23 = LW 26:318.

21WA 40 2:584,22-36 = LW 12:281.

22CR 21:719.

23WA 33:91,42 - 92,6; 92,38 - 93,1-10; 93:20-36; 94,1-11 = LW 23:62-63.

24WA 40,1:207,17-18 = LW 26:115.

25Cf., WA 51:239,22-30 = LW 13:194-195.

26 SIMUL

AN EXPLORATION INTO THE THIRD USE OF THE LAW: A BIBLICAL MEDITATION AND THEOLOGICAL INQUIRY

Henry A. Corcoran, Ph.D.

Peacemaking

I make peace.1 As a peacemaker, I look for common ground; I search for paths forward that honor the central values of the parties involved. As one scouting the disputed territory, in this case the ways God uses the law in pursuit of those he loves, I try to listen carefully to the disputants. I observe that contenders for the evangelical and biblical truth. If they disagree, they often have in their respective camps canons of proof texts, differing foundational community stories, argument-specific analogies and language,2 and finally, and most importantly, a love for God that is rooted in a core value to which they cling. The intensity of the dispute, the ferocity of disagreement, the absence of gentleness, and the

27

SIMUL

refusal to lay down their swords demonstrates that the core value each party defends is seen as being crucial to how they view God.3 For example, within the ‘canon’ of those who argue that instruction for holy living ought to be included among the uses of the law, Psalm 1 comes to mind. This Davidic poem was the first text cited by Martin Chemnitz, et.al., in the Solid Declaration (Formula, VI, 4) to support the teaching of a third use. Unfortunately, they read the Psalm having already determined the meaning of torah.

Torah Torah, Hebrew for instruction, embraces a variety of literary forms: from gripping narratives to concise legal codes, from swaggering genealogies to vibrant poetry, from impassioned prayers to fiery prophecies, from didactic instruction to subversive parables. The word stretches to include God's word of law and gospel: law as exemplified in Exodus 20 and gospel as trumpeted by Genesis 15:6. To require that torah mean ‘Exodus 20’ law in Psalm 1 not only conflates the range of possible meanings of the word but transforms a song of life into a funeral dirge, a transformation inconsistent with the fruitful, verdant, flowering, and prospering image of a tree central to the poem.

On the other hand, among the argument-specific

28 SIMUL

Chemnitz

analogies used by those who deny third use might be the complete absence of moral imperatives for Adam and Eve in the garden, save the one denying them consumption of the fruit of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil. The analogy might go: as with our first parents, so for us, too. If they didn’t require instruction, neither do we. Unfortunately, such an analogy argues from ignorance, as if all the details of our first parents’ torah were made known in the Genesis account, especially in the light of the well-established paucity of detail characteristic of biblical narratives.4

Perhaps having alienated both parties in just three paragraphs, allow me to see if I can name the core value that compels each camp and win back a hearing. For those arguing two uses, the image of a new creature wholeheartedly held by God's grace, with eyes fixed on the beatific vision of Christ, claims first place. From this side, they might urge: How can such a one act except in love for God and his creatures? And as we all agree, love completes the law, right?

But for those arguing three uses, simul iustus et peccator claims center stage. One justified in Christ cannot be but sinner. To believe differently offends Christ and consequently, the triune God. From this side, they might ask: How can one offend Christ and simultaneously assert a single-hearted love for him?

Based on previous experience, the two

29 SIMUL

Based on previous experience, the two entrenched parties can no longer hear what the other says, will not look past their own proof texts, will not listen to new stories, nor explore opposing perspectives.

entrenched parties can no longer hear what the other says, will not look past their own proof texts, will not listen to new stories, nor explore opposing perspectives. I would propose an alternate way forward, a biblical meditation with several soulsearching questions followed by a practical theological inquiry ― an experiential approach.

Quantum Leap

The apostle Paul frequently refers to Christian believers as those ‘in Christ.’ For instance, in his greeting to Christians in Ephesus, Paul calls his readers, “holy ones” and “faithful followers” in Christ (έν Χριστώ, Ephesians 1:1). Rather than turn our conversation into a left-brain mini lecture on the precise meaning of the New Testament Greek term, en Christo in Paul’s writings, I invite you to engage in an exercise of the imagination. Like the Scott Bakula character from the old TV show, you suddenly find yourself ‘quantum leaped’ into Christ Jesus. Seated on the bank of a large loop of the Jordan River, the air feels warm and dry. A puffy sky island shades you from the sun. A slight breeze briefly shakes the leaves in the shrubbery across the stream. A dozen or so people wade in the water. In a simple loin cloth, you slide into the cool flow. The water’s chill balances nicely with the warm air as several strong splashing strides bring you to the

30 SIMUL

Scott Bakula

prophet.

As you approach him, tan and lean, you note that he is barely covered by the typical homeless-guy’s camel-skin girdle. You trade words of disagreement with John the Baptizer, a genuine Near-Eastern eccentric. You want his baptism; he feels unequal to the task. You win. The baptizer positions himself to your side. He places his left-hand squarely in the center of your back, and whispers, “Lean back.”

Chilled to the bone, and bathed in streams of light which pierce the churning waters, the river then darkens as you sink deeply into the flow. Standing again, the breeze nips you as water drips into the Jordan. Hands raised high, Hebrew prayers bubble up, and then snatches from the psalms take wing, as you lift your eyes to the heavens. God breaks in.

He rips apart the cloud and the golden sunlight pours upon you. Like a dove, the Spirit lights on your shoulder, leaving surface scratches where claws try to find a perch. God speaks in His thunderous voice, “You are my beloved child; in you I am delighted.”

Do you hear what God says? God says, “You are my beloved,” not “You need to pray more.” God whispers, “You are my beloved,” not “I’m unhappy with you.” God breathes into your ear, “I delight in you,” not “You are such a loser.” God roars before every witness in heaven, on earth, and under the earth, “In this one, I am

31 SIMUL

John the Baptist

well-pleased.”

God’s strong and sustained affirmation of all those in Christ has practical value. It provides a place for us to stand. Here we are survivors of a world gone crazy, struggling with a variety of challenging emotions. Did you ever wonder what sustained Jesus as He faced rejection and hostility? In Mark’s gospel, Jesus turns from His baptism and goes into the Judean wilderness for forty days. How did He fill those endless hours without electronics, without companionship, without comfort food (or any food for that matter), and without the scheduled activities that structure daily life?

It seems reasonable that in His wilderness retreat that He fired up the memories of His baptism, that He engaged memories of the smells, sights, sounds, and textures of that day. He tasted again the water as it coursed off His head and hair, felt the rough texture of the vegetation upon which He sat on the riverbank, and relished the rupture of the clouds between He and the “deep heavens” that ushered in His experience of God. As neurologists say, ‘What fires together wires together.’ Jesus’ focused meditations on His baptism and the God experience fired and wired His brain with sustaining neurological connections that enabled Him to bring a positive perspective and the emotional energy to face some daunting enemies with both courage and love.

As those in Christ, can’t we also engage our imaginations on His and, therefore, our experience in the Jordan River? We could listen to the sounds of streaming water, splashes from

32 SIMUL

As neurologists say, ‘What fires together wires together.’

the baptized and baptizers, and their quiet conversations. We could feel the warm, dry air, the refreshment of the water flow, and the joy of hearing God’s voice as He delights in us. Indeed, could we not endlessly listen to the divine declaration, “You are My beloved; in you I am well-pleased?” And perhaps then, as we rehearse the event in our daily meditations, might such a scene provide us the buoyancy to face our challenging life circumstances?

When the apostle Paul writes to those “in Christ,” he writes to you. The affirmation God gave Jesus in the descent of the Spirit and the rumble of His voice, “You are my beloved child; in you I am well-pleased” reaches you because by faith in the gospel, you are in Christ. By divine shout and Spirit baptism, God celebrates you, in Christ.

I hope that you fully engaged this little exercise in your imagination, paying close attention to the details Mark provides in his narration of the baptism of our Lord Jesus. Assuming you have (and inviting you to do so if you haven't), let's examine the experience. Perhaps like me, at first, you found such an exercise difficult. Were you able to picture yourself freshly baptized; hearing God’s thunderous affirmation? Were you personally affirmed? What did you feel? Did you find gratitude bubbling up in your heart? Joy? Peace? Irritation?

As I reflect further on my experience, I enjoyed the positive divine affirmation, but I struggled to accept it. What in me resists such affirmation and especially this divine testimony?

33 SIMUL

Did you find yourself resisting the idea of Jesus rehearsing the events and sensate experiences of His baptism during the forty-day fast, but as you pondered on it, found it plausible, even likely? Like me, did you want to learn more about this form of biblical meditation ? Were you better able to see what being in Christ might look like? Did you notice with further reflection that the justification fiat has been reframed from a courtroom context to a narrative setting, where God is presented as adoring parent rather than judge? Did you observe that as the storyteller applied the divine decree to his audience, the primary focus shifted from the justification concern for the forgiveness of sins, a reality assumed, to the silencing of internal accusations and the quieting of voices of shame?

As I weighed it out, the storyteller’s goal isn't so much to cause gratitude to boil up in the hearts of his hearers, but rather that they would appropriate their new identity in Christ. Would you affirm that to hear and believe God as He says, “You are my beloved,” shifts those baptized in Christ from old creation to new? As you reflect on this experience, were you fully engaged and present to God's word of gospel? Or did you hold a part of yourself aloof? Unmoved? Unwilling? After exercising theological reflection, have you disengaged even further from the event? Have you now positioned yourself as critic, rather than as a participant in the meditation?

34 SIMUL

Paul and Forde

These questions provide a kind of Pauline ‘litmus’ test of the flesh. One of Gerhard Forde’s gifts to the church was his clearheaded observation that Paul positioned the natural person, the flesh (σάρξ) in opposition to God’s word of law AND gospel.5 In Galatians 5, the works of the flesh clearly act in opposition to the divine moral law. Paul also demonstrates in Galatians 3, that works of the flesh battle against the gospel. My response to the in Christ meditation (perhaps yours too) makes me better aware of the presence and activity of the flesh in my life.

Like Paul discussing someone in Christ “caught up to deep heaven,” reluctantly I mention a seminarian in Christ who, studying the uses of the law, crafted a sermon intending that his hearers be sanctified by his enthusiastic proclamation of the third use of the law. In His goodness, God allowed a messenger of Satan to torment the budding theologian until he repented. For it is God the Holy Spirit, and God alone who deploys the law as needed. Not a foolish pastor-in-training but the living God, as He accomplishes His alien work through His law preached, who restrains, accuses, and instructs the various hearers. As I listen carefully and thoughtfully to voices on both sides of the discussion on third use of the law, I have promised myself to remember this well-meaning seminarian, lest I think

35 SIMUL

Forde

myself master of these uses rather than recipient, as theologically above rather than below the Word.

Including Right-Brain Experience

In part, this essay attempts to shift the discussion from solely left-brain analysis to include right-brain experience by means of a meditation on Jesus’ baptism and by means of the series of questions about one's responses to the experience. I assert that only with this ‘thorn in the flesh,’ only with this shift from argument alone to lived experience of God’s Word, can a theologian rightly discern how God uses his law. In terms of Luther’s rubric for the making of a theologian: oratio, meditatio, tentatio, discernment of God’s uses of law comes only through tentatio, or even Anfechtung, as God himself restrains, accuses, or instructs one's own heart.

What I have discovered about my own heart humbles me. In this exercise, the law has accused me, but the gospel delivered me. In this reflection I have come face to face with one who resists God’s word law and gospel, revealing the presence of the accursed flesh. Having met my own heart, I cannot imagine that I would ever be so free of flesh, so centered in gospel that I would not know the restraining and accusing power of God's law, a necessary condition to determine from experience whether my spirit requires the law’s instruction or not. Friend, how about you? Having glimpsed your own heart, can you imagine yourself or any human this side of eternal life being freed of the flesh, the flesh that opposes the Word of God, law and gospel? If you cannot, and I cannot, wouldn’t you agree that this dispute

36 SIMUL

argues over hypotheticals?

Rev. Dr. Henry A. Corcoran is Senior Pastor at Christ the Servant Lutheran Church, Conway, SC

Endnotes:

1As example, see my attempts to negotiate the secular and faith divide in my dissertation, Henry A. Corcoran, “A Synthesis of Narratives: Religious Undergraduate Students Making Meaning in the Context of a Secular Research University,” University of Denver, 2007(a), and 2007(b), or to reframe the insights of the psychology of forgiveness into Lutheran theological structures, see Henry A. Corcoran, Forgiving "Unforgivable" Injustices: A Lutheran Interpretation of the Processes of Interpersonal Forgiveness,” Lutheran Education Journal, 2009, 143 (2): 97-110.

2For a more complete exploration of communities of scholars sharing the exact same body of knowledge but interpreting that knowledge using widely differing paradigms, see Thomas Kuhn, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (Chicago: University of Chicago Press) 2012.

3A useful analysis of four Western cultures, especially, the prophetic and reformer culture discussed here, see John W. O’Malley, Four Cultures of the West (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Belknap Press, 2004.

4See Robert Alter, The Art of Biblical Narrative (New York: Basic Books, 2011).

5See Gerhard Forde. “The Lutheran View [of sanctification],” in D. Alexander, Ed., Christian Spirituality: Five Views of Sanctification (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 1988).

37 SIMUL

THE USES OF THE LAW –2 OR 3? A PASTORAL PERSPECTIVE

Rev. James L. Cavanah II, Th.D.

Introduction

In this issue of SIMUL, we seek to address the topic, “Uses of the Law – 2 or 3?” Therefore, the question is one that is both theological and practical in nature. Pastorally, the answer to the question is firmly established in the revealed truth of the Word of God. It is the task and calling of the pastor to preach and teach all God’s holy truth (i.e., Acts 20:27). Sola Scriptura!

On the night in which He was betrayed, our Lord Jesus prayed in the garden. In His High Priestly Prayer (John 17), He petitioned His Father on behalf of all of His disciples in every age and in every place. In His prayer, He petitioned the Father and said, “Sanctify them through thy truth: thy word is truth” (John 17:17, KJV). Those words are personal. They have divine

38

SIMUL

origin, they are practical in nature, and they come directly from the lips of our Savior.

Indeed, we find the inspired divine revelation of God only in scripture (see John 6:68; Romans 1:16). Stephen J, Nichols, president of Reformation Bible College, explains that “in response to the medieval church, which had misplaced the Word of God, Luther places the Word at the very heart of the church’s practice and life.”1 The Word alone is the very foundation upon which the Reformation was established. Luther sets forth a clear and enduring principle, the Word of God alone is our only authority in all matters of faith and life.

The words of Luther resound with a theology filled with practical application for every aspect of life. Luther embraced Paul’s exhortation to Timothy, “But continue thou in the things which thou hast learned and hast been assured of, knowing of whom thou hast learned them; And that from a child thou hast known the holy scriptures, which are able to make thee wise unto salvation through faith which is in Christ Jesus. All scripture is given by inspiration of God, and is profitable for doctrine, for reproof, for correction, for instruction in righteousness: That the man of God may be perfect, thoroughly furnished unto all good works” (II Timothy 3:15-17, KJV). Paul’s desire for Timothy and for all followers of Christ is to be “thoroughly furnished unto all good works.” Luther believed this. The major Reformers embraced this. But how is it possible?

39 SIMUL

Stephen J. Nichols

In the Holy Scriptures Luther found this divine assurance, “Therefore, whenever anyone is assailed by temptation of any sort whatever, the very best that he can do in the case is either to read something in the Holy Scriptures, or think about the Word of God, and apply it to his heart.”2 To apply the Word of God to our hearts is to embrace the truth espoused by Paul, “Even the mystery which hath been hid from ages and from generations, but now is made manifest to his saints: To whom God would make known what is the riches of the glory of this mystery among the Gentiles; which is Christ in you, the hope of glory” (Colossians 1:26-27, KJV). Note the words, “Christ in you, the hope of glory.”

For every pastor, it is essential to faithfully preach both law and gospel. To this end, Paul sums up the basis of our redemption, “For by grace are ye saved through faith; and that not of yourselves: it is the gift of God: Not of works, lest any man should boast. For we are his workmanship, created in Christ Jesus unto good works, which God hath before ordained that we should walk in them” (Ephesians 2:8-10, KJV). The gospel is never about what we do for God. The gospel is always about what He does for us.

Therefore, how are we to understand these “good works” that God intends for His people to do? In his letter to the Corinthians, Paul reveals the practical means through which God establishes His goal of making His people “his workmanship, created in Christ Jesus unto good works” (Ephesians 2:10, KJV). He affirms the fact that our salvation and renewal in Christ (see Romans 12:1-2) comes only as we, God’s people, are “in Christ” – “Therefore if any man be in

40 SIMUL

Christ, he is a new creature: old things are passed away; behold, all things are become new” (II Corinthians 5:17, KJV).

On the night of his betrayal, Jesus said to His disciples, “If ye love me, keep my commandments” (John 14:15, KJV), “He that hath my commandments, and keepeth them, he it is that loveth me: and he that loveth me shall be loved of my Father, and I will love him, and will manifest myself to him” (John 14:21, KJV), and “If ye keep my commandments, ye shall abide in my love; even as I have kept my Father's commandments, and abide in his love” (John 15:10, KJV).

Only “in Christ” (i.e., Romans 3:24, 8:1-2; Galatians 3:26-2; Ephesians 1:10, 2:6 and 10) is the Christian justified and sanctified. To this end, Christ loves us and brings us into fellowship with Himself and with one another in His church as one body.

The Second Use of the Law

The second use of the law has been called by some “the principal use.” By it, we discover our natural estate, separated from God. We are dead in trespasses and sins (i.e., Ephesians 2:1; Colossians 2:13). We are without hope and under the condemnation of the law (see Romans 5:16 and 18). It has also been said that the law is a reflection of God’s holiness, righteousness, and justice. When confronted with the power of the law, the second use of the law, we see our unholiness, unrighteousness, and utter depravity. This fact is clearly evident in Scripture and was the

41 SIMUL

The second use of the law has been called by some “the principal use.”

personal experience of three well-known biblical figures: (1) Isaiah (Isaiah 6:5), (2) Peter (Luke 5:8), and “the disciple whom Jesus loved,” John (Revelation 1:17). The second use of the law has often been referred to as a mirror. It reflects to us our real and true identity. We are, by nature, lost sinners!

In his first letter to Timothy, Paul wrote, “But we know that the law is good, if a man uses it lawfully” (I Timothy 1:8, KJV). The law of God has been given to restrain sin. This is the first use of the law (the civil use) and to condemn sin which is the second use or the accusatory use of the law. This brings us to the question: “Uses of the Law – 2 or 3?” As a pastor, I must answer the question and I say, “Yes!”

Martin Luther embraced the fact that preaching is the power of the gospel to both kill and to make alive. Consider these words, “Whereas most theologians emphasize the progressive nature of God’s work through law and gospel first to terrify, then to comfort and convert, and finally to guide the believer, Luther stresses the ongoing and simultaneous quality of God’s work to put to death sinful persons and raise to life new persons in Christ Jesus. From the moment Christians come to faith, Luther contends, they live as people who are simultaneously sinful by nature and righteous by God’s declaration and deed, a condition he describes as living simul justus et peccator.”3

“There is, then, one law of God that works in us and on us in two distinct ways. Further, both uses of the law are related to God’s creatures; through the first to sustain and protect the creation by promoting civil conduct, and through the second

42 SIMUL

to lead people to salvation in Christ.”4

To this end, “God speaks in two fundamentally different ways. He speaks a word of law that threatens sinners with divine punishment, delivers wrath, and brings death and condemnation. Yet He also speaks a word of Gospel that promises grace to underserving sinners, bestows forgiveness of sins, and delivers life and salvation.”5

In Lutheran theology, the child of God, who is both saint and sinner, is constantly hearing the law and the gospel. The law drives us to understand our sinful estate and then Christ comes to us. This is an important point. We do not come to Christ. Rather He comes to us. In His divine power, Christ brings the power of the gospel (Romans 1:16) to us, sinners who are dead in sin, and He works in us to make us alive, to give us the gift of faith whereby we repent of our sins and find forgiveness in Him alone.

Sanctification

Justification is the act of God. So, also, sanctification is a work of Christ through the gospel. In Christ, we are set free from sin and the penalty of sin. In Christ, that is Christ working within us through our gracious union with Him, we are freed to engage in the works that God has ordained for us to do (i.e., Ephesians 2:10) but only as Christ works within us. In other words, we are freed by God, in Christ and Christ in us, to begin to live the life that God intends by the power of the gospel (see Ephesians 1:9 and 3:20; II Peter 1:3).

Justification is the act of God. So, also, sanctification is a work of Christ through the gospel.

43 SIMUL

“While the Law of God promises life to those who keep it and threatens punishment to all who break it, it is powerless to make a person righteous in the sight of God. It is only the Gospel that declares sinners righteous, not on account of their morality or good intentions but solely because of the work of Jesus Christ, who has fulfilled the law, suffered under its condemnation in our place, and been raised from the dead as our Brother.”6

In Luther’s Commentary on Galatians, he appeals to two uses of the law. Yet, in his Instructions for the Visitors of Parish Pastors, Luther does draw near to the third use of the law when he touches upon “the doing of good works” that include “to be chaste, to love and help the neighbor, to refrain from lying, from deceit, from stealing, from murder….”

In the first preface to his Large Catechism, Luther wrote a similar sentiment, “For it is certain that whoever knows the Ten Commandments perfectly must know all the Scriptures, so that, in all circumstances and events, he can advise, help, comfort, judge and decide both spiritual and temporal matters, and is qualified to sit in judgment upon all doctrines, estates, spirits, laws, and whatever else is in the world.” After having addressed all of the Ten Commandments, Luther added these words in his conclusion, “Thus we have the Ten Commandments, a compend of divine doctrine, as to what we shall do, that our whole life may be pleasing to God, and the true fountain and channel from and in which everything must flow that is to be considered a good work, so that outside of these Ten Commandments no work or thing can be good or

44 SIMUL

pleasing to God, however great or precious it be in the eyes of the world.”

“Because of fleshly lusts, God’s truly believing, elect, and regenerate children need the daily instruction and admonition, warning, and threating of the Law in this life. But they also need frequent punishments. So that will be roused and they will follow God’s Spirit” (i.e., Psalm 119:71; I Corinthians 9:27; Hebrews 12:8).7

As man is semper simul – always sinful and only made just or righteous by the unmerited love, mercy, and grace of almighty God – the power of the law was looked upon in days past, and by some in our present time, as a means of somehow guiding us or helping us to grow in our relationship with God and our neighbors, but nothing could be further from the truth! The Law is not a guide or a spiritual “punch list” for the Christian. This misunderstanding of the law was the failure of the Pharisees and made obvious in Paul’s own words of personal confession (Philippians 3:2-11).

The Law is not a guide or a spiritual “punch list” for the Christian.

The law kills and condemns. It does not provide a means of merit to enhance our justification or our sanctification. The law reveals our total and complete sinful nature without Christ. Rather than saying that the law drives us to Christ, perhaps it would be best to say, the law drives us to complete hopelessness, despair, and death. Then, Christ comes to us with the message of the Gospel and gives us complete forgiveness, comfort, and peace.

45 SIMUL

Third Use of the Law

It appears that Martin Luther and Philip Melanchthon both wrote about the third use of the law without ever using the phrase “the third use of the law.” Rather, they used words like Gebot (commandment), mandatum (command), and praeceptum (precept). The terminology may be different, but Luther and Melanchthon were in agreement, God alone works in man to accomplish His divine will.

In both the Short and Large Catechisms, Luther refrained from explicitly using the phrase “the three uses of the Law.” Perhaps, upon deeper reflection, there is good reason for this. Is it possible that Luther preferred words such as “commandment”, “command”, “precept” or “rule” to distinguish God’s guide for life (i.e., John 14:15 and 23; John 15:10) from the law (lex) that accuses (lex simper accusat)? Is it possible that this distinction in terminology was a way of differentiating between the law that always condemns and the “command” (mandatum) that guides the justified who are in Christ in proper godly living?

We need to see and understand the law’s perfection only in Christ (Matthew 5:17; Luke 24:44). Only in Christ is there a full and perfected fulfillment of law and gospel. In Him and in Him alone, is there direction for the new earthly life of the Christian. One cannot add to what Christ has done. Therefore, in Christ, there is the command (the third use of the Law) to

46 SIMUL

embrace and appropriate the words of Paul, “I beseech you therefore, brethren, by the mercies of God, that ye present your bodies a living sacrifice, holy, acceptable unto God, which is your reasonable service. And be not conformed to this world: but be ye transformed by the renewing of your mind, that ye may prove what is that good, and acceptable, and perfect, will of God. For I say, through the grace given unto me, to every man that is among you, not to think of himself more highly than he ought to think; but to think soberly, according as God hath dealt to every man the measure of faith” (Romans 12:1-3, KJV).

The Formula of Concord, Article VI, clearly defines three uses of the law: “God’s Law is useful (1) because external discipline and decency are maintained by it against wild, disobedient people; (2) likewise, through the Law people are brought to a knowledge of their own sins; and also (3) when people have been born anew by God’s Spirit, converted to the Lord, and Moses’s veil has been lifted from them [I Corinthians 3:13-16], they live and walk in the Law [Psalm 119:1]”.8

Pastorally speaking, we must embrace the words of Jesus which describe all of His followers in every age and place, “Ye are the salt of the earth: but if the salt have lost his savour, wherewith shall it be salted? it is thenceforth good for nothing, but to be cast out, and to be trodden under foot of men. Ye are the light of the world. A city that is set on a hill cannot be hid. Neither do men light a candle, and put it under a bushel, but on a candlestick; and it giveth light unto all that

47 SIMUL

Book of Concord

are in the house. Let your light so shine before men, that they may see your good works, and glorify your Father which is in heaven” (Matthew 5:13-16, KJV).

The great plague of the Roman Church in Luther’s day and among many Christians in our day, is a false and vain obedience or pretense of self-righteousness based upon manmade rituals, practices, or acts. These were a plague upon Luther’s personal life as well, prior to the work of God in revealing the truth of the gospel to him. The second use of the law condemns and accuses but we must also recall these words, “But we know that the law is good, if a man uses it lawfully” (I Timothy 1:8, KJV). The law must be used lawfully!

The great plague of the Roman Church in Luther’s day and among many Christians in our day, is a false and vain obedience or pretense of selfrighteousness based upon manmade rituals, practices, or acts.

The impact of this fact is seen in the first of Luther’s 95 Theses. Clearly, it challenges and affirms the true Christian life, “When our Lord and Master, Jesus Christ, said ‘Repent,’ He called for the entire life of believers to be one of repentance.” It is the function of the law to work daily contrition and repentance in life and not some type of one-time experience of conversion. With this in mind, it is a function of the law to work within us daily calling us to contrition and repentance (second use) and to guide us (third use) in doing the “good works” that Christ produces in us. These works are the work of Christ in us.

48 SIMUL

These are not our good works. They are the manifestation of the new man living within us.

At the Bedside of the Dying

It has been said that the real enemy of human freedom is not the law of God but the power and allure of sin and temptation. Against these forces the law and the gospel remains the only divine revelation of truth. The mirror and the guide of God’s divine law remains the only wholesome witness to the goodness of God and His power in this world. The pastor is often times called to the bedside of the dying to offer hope, peace, and to bring comfort in the final hour. At that time, it is not the law or one’s sanctification or alleged “good works” that needs to be mentioned. Rather, it is the glorious message of the gospel that must be heard! The Christian must be reminded and called to focus upon Christ alone as the only means of salvation – the vicarious suffering\death, and resurrection. This is what brings peace and comfort.

As to the question: “Uses of the Law –2 or 3?” As a pastor, I must answer the question and I must say, “Yes” and return to the words of Paul, “But we know that the law is good, if a man uses it lawfully” (I Timothy 1:8, KJV). Therefore, we may refer to the second or

As to the question: “Uses of the Law –2 or 3?” As a pastor, I must answer the question and I must say, “Yes” and return to the words of Paul, “But we know that the law is good, if a man uses it lawfully” (I Timothy 1:8, KJV).

49 SIMUL

the third use of the law as a means of making fine theological distinctions. We may refer to a mirror or a guide. We may see complete separation between the second and third uses or perhaps a degree of practical overlapping. However, for the pastor who is called to preach, teach, and proclaim the whole counsel of God, the most important truth is the scriptural edification of God’s holy people (I Peter 1:16, 2:5 and 9). Therefore, the law affirms that it is God’s will that His people, redeemed by Christ and are in Christ, should walk in a new life. Paul supported this view of God’s plan for His people with these words, “Therefore we are buried with him by baptism into death: that like as Christ was raised up from the dead by the glory of the Father, even so we also should walk in newness of life” (Romans 6:4, KJV). In Christ, the law is fulfilled. In us, be it called the mirror (the second use) or the guide (the third use), we discover this truth – “For we are his workmanship, created in Christ Jesus unto good works, which God hath before ordained that we should walk in them” (Ephesians 2:10, KJV). Therefore, it is the responsibility of the pastor to properly and correctly preach, teach, proclaim, and walk in law and gospel and to encourage others to do the same, living Coram Deo!

Endnotes:

1Stephen J. Nichols, Beyond the 95 Theses (Phillipsburg, N.J.: P&R Publishing, 2016), 200.

50 SIMUL

Rev. James L. Cavanah II, Th.D. is Pastor of Holy Trinity Evangelical Lutheran Church in Springfield, Georgia

2August Nebe, Luther as Spiritual Adviser (Philadelphia: Lutheran Publication Society, 1894), 178.

3David J. Lose, “Martin Luther on Preaching the Law” Word & World, Vol. XXI, No. 3, (January 2001), 256.

4Ibid., 255.

5John T. Pless, Handling the Word of Truth: Law and Gospel in the Church Today (St. Louis: Concordia Publishing House, 2004), 25.

6James A. Nestingen and John T. Pless, eds., The Necessary Distinction: A Continuing Conversation on Law and Gospel (St. Louis: Concordia Publishing House, 2017), 15.

7Timothy McCain, Edward Andrew Engelbrecht, Robert Cleveland Baker, and Gene Edward Veith, eds. Concordia: The Lutheran Confessions: A Reader’s Edition of the Book of Concord (St. Louis: Concordia Publishing House, 2006), 557-8.

8Ibid., 559.

51 SIMUL

REVISITING THE THIRD USE OF THE LAW, AGAIN

Rev. John W. Hoyum

Introduction

To what does the sixth article of the Formula of Concord (FC) commit us? That’s the question – no doubt raised over and over again before – to which I’d like to venture an answer. There is a widespread suspicion that mainline Lutheranism has embraced moral mayhem because of its underlying antinomianism, and that at the root of this antinomianism is a rejection of the third use of the law.1 Without the third use, so the story goes, we are left with a kind of limitless freedom that entitles us to reconstruct human relationships and update sexual norms as culture changes.2 The third use of the law, in this case, is a kind of anti-gnostic mechanism that prevents us from detaching Christian moral conduct from the structure of creation, which itself mirrors God’s goodness. Accordingly, the law is a neutral standard which expresses the moral character of the divine being as the highest good (summum bonum). The law in its effects reveals and accuses sin, but this belongs not

52

SIMUL

to the law’s own essence but to the temporal situation in which divine holiness meets human sinfulness. All this culminates in the contention of Lutheran orthodoxy that the law is eternal (lex aeterna).3

Others have profitably engaged this account of the law’s third use and its entanglement with other topics, especially the doctrine of God and the apparent divergence between Luther and the tradition which succeeded him.4 The rejection of the third use on theological grounds and with respect to Luther’s writings is well-established, in my view. But even so, the confessional question remains, especially for those of us who claim to be confessional Lutherans. Does the rejection of the third use of the law involve the rejection of the Formula as a confessional document for Lutherans today? Instead of rehearsing the arguments about Luther’s doctrine of the law and its difference from the doctrine that emerges in Lutheran orthodoxy, I wish instead to make the case for the Formula’s position to the skeptics of the third use. My contention – contrary to that of both advocates and skeptics – is that subscription to the Formula doesn’t obligate us to adhere to a third use in the strict sense, nor its dubious implications like the lex aeterna. 5 First, I will take up the question of confessional subscription today and why it is of enduring importance for Lutherans. Then, I will work with the text of FC VI to make the case that in it there is no third use of the law to be found. Finally, I will

53 SIMUL

Does the rejection of the third use of the law involve the rejection of the Formula as a confessional document for Lutherans today?

conclude with some reflections on what it means to subscribe to this document today.

Confessional Subscription Today

At least two important questions mark the matter of confessional subscription. First, what does it mean to subscribe to a set of confessional documents? Second, to which documents should one subscribe? When it comes to the third use of the law, both of these are in play. Concerning the first, I’d point to the promises made by the ordinand that lie at the heart of the ordination rite. The most convenient place to look is the Occasional Services book attached to the Lutheran Book of Worship (1978). In addition to stating that the Lutheran church holds that the “Holy Scriptures are the Word of God and are the norm its faith and life,” the rite adds that “We also acknowledge the Lutheran Confessions as true witnesses and faithful expositions of the Holy Scriptures.” In turn, the ordinand is asked to pledge that they will “therefore preach and teach in accordance with the Holy Scriptures and these creeds and confessions.”6 This brief promise – “I will, and I ask God to help me”7 – is for all intents and purposes a quia, instead of quatenus, form of subscription. One subscribes because (quia) these Confessions are “faithful expositions” of scripture, not “insofar as” (quatenus) they faithfully confess what the Bible says.8

LBW

54 SIMUL

Occasional Services

The second important question when the third use of the law is up for debate is this: which Confessions are we talking about? This is tricky because the ordination vow doesn’t include any particular list. For this, we have to turn to things like denominational constitutions. It’s not up for debate that the churches descending from the old Synodical Conference subscribe to all the documents of the 1580 Book of Concord, which of course includes the Formula. But for churches like Lutheran Congregations in Mission for Christ (LCMC) or the North American Lutheran Church (NALC), this is more contested. The reason for this is that both these churches inherit a debate about the extent of the Lutheran confessional writings that extends back into the nineteenth-century. Because of how the Reformation proceeded in Norway and Denmark, those churches accepted only the Augsburg Confession (1530) and the Small Catechism (1529), without signing on for the other documents. Whatever political circumstances led to this situation at the time of the Reformation, Herman A. Preus has shown that this by no means involved a rejection of the doctrine of the Book of Concord, particularly among the most conservative Norwegian Lutheran immigrants to the United States.9

But regardless of this history, both LCMC and the NALC subscribe to all of the documents of the Book of Concord. Both constitutions set forth the Augsburg Confession (AC) as the

55 SIMUL

Herman A. Preus

primary Reformation-era document, and LCMC adds the Small Catechism (SC). Yet both constitutions list the other documents of the Book of Concord as well, calling them either “further valid expositions of the Holy Scriptures” (LCMC) or “further valid interpretations of the faith of the church” (NALC). The NALC’s constitution closely follows the verbiage inherited from the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America (ELCA), while LCMC’s description of the Book of Concord as scriptural exposition follows the language of The American Lutheran Church (TALC ).

While one might quibble with the vagueness of the word “valid,” taken alongside the unqualified nature of the ordination vow, what we have in both of these constitutions is a fairly strong, and classically Lutheran, understanding of confessional subscription. The practical reality on the ground in these churches is of course another matter entirely. But for those exiles from the ELCA, the retrieval of the Lutheran Confessions is paramount – not least because doctrinal indifferentism and poor discernment of the spirits was one of the root causes of mainline decline among American Lutherans. A return to the Lutheran confessional writings needn’t take the form of casuistry, as if we were dealing with mere canon law. Rather, Lutherans today might learn from these confessions as “charters” of evangelical freedom –setting forth the proper theological foundation to make sure that when we preach and confess, it’s actually the gospel.10

A Reading of FC VI

Having now explored the nature of confessional

56 SIMUL