GNIRPS

Stork Magazine is a fiction journal published by undergraduate students at Emerson College. Initial submissions are workshopped and discussed with the authors, and stories are accepted based on the quality of the author’s revisions. The process is designed to guide writers through rewriting and provide authors and staff members editorial support and an understanding of the editorial and publishing process. Stork is founded on the idea of communication between writers and editors—not a simple letter of rejection or acceptance.

We accept submissions from undergraduate and graduate Emerson students in any department. Work may be submitted at stork.submittable.com during specific submission periods. Stories should be in 12-point type, double-spaced, and must not exceed 4 pages for the “flash fiction” issue. Authors retain all rights upon publication. For questions about submissions, email storkstory@gmail.com

Stork accepts staff applications at the beginning of each fall semester. We are looking for undergraduate students who are well-read in contemporary fiction and have a good understanding of the short story form.

Copyright © 2025 Stork Magazine

Cover design done by Eden Ornstein

Illustrations done by Gabrielle Finucan, James Arabia, and Greer Wheeler

Typesetting done by Eden Ornstein and Liz Gómez

Spring Fiction 2025

King Tide

By Madison Mondeaux

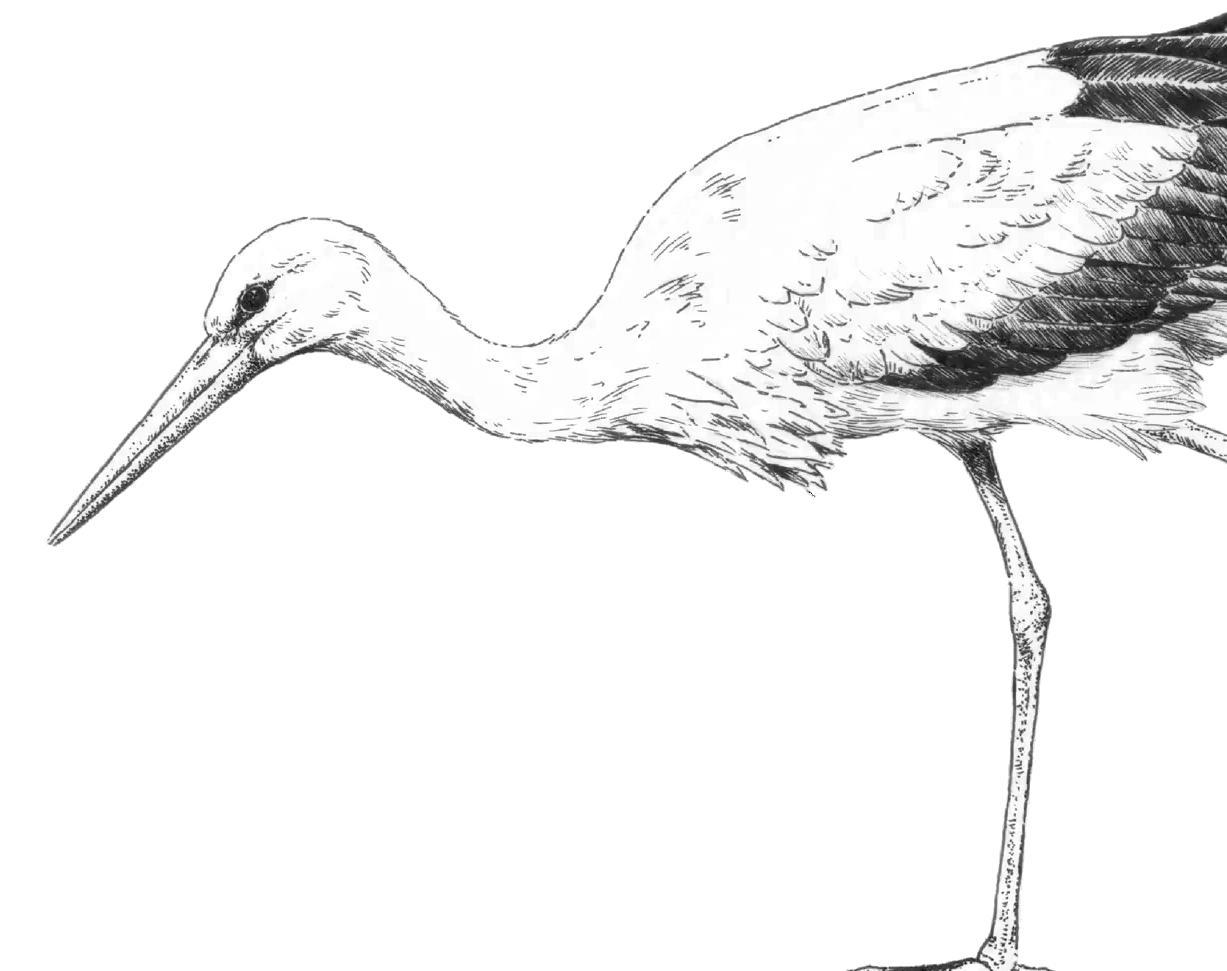

Illustration by Gabrielle Finucan

The Father of Connecticut

By Max Ardrey

Illustration by Greer Wheeler

Ship Log

By Ben Tardiff

Illustration by James Arabia

The Face of God (In Ones and Zeroes)

By Brenna McCord

Illustration by Gabrielle Finucan

Gutter Dog

By Jack Silver

By Tariq Karibian

54 62 11:21 PM – 11:31 PM at the Aces

The Port Authority Bus on Sinkhole Safety

By Paige Tokay

Illustration by Wheeler

Postmortem

By Jenna Benson

MASTHEAD

Editors in Chief

Gabriel Borges

Sydney Flaherty

Managing Editors

Alexandra Dening

Roni Moser

Stella Lapidus

Claire Hagerty

Head Designer

Eden Ornstein

Design Team

Lauren Mallet

James Arabia

Greer Wheeler

Gabrielle Finucan

Elizabeth Gomez

Head Copy Editor

Ava Belchez

Copy Editors

Mars Early

Roni Moser

Emma Carr

Chad Coursen

Prose Editors

Dana Guterman Levy

Alexander Pham

Nancy Cordon

Madison Miller

Staff Readers

Elliot Berkley

Sadie Lallier

Joseph Fitzgerald

Luke Flanagan

Zachary Overholser

Marin/Spencer Madden

Lillian Flood

Ava Kevitt

Taylor McDonald

Emma Bogusz

Emma O’Keefe

Jackson Sotallaro

Ella Miller

Amulet Gilberti

MASTHEAD

Substantive Editors

Alexandra Dening

Roni Moser

Rachel Dickerson

Jayden Beverly

Emmett Davis

Tenley Lillegard

Kai Etringer

Declan Ireland

Social Media Manager

Lily Suckow Ziemer

Audio Issue Team

Alexandra Dening

Elliot Berkley

Colten Hitchcock

Faculty Advisor

Jon Papernick

Letter From The Editors

Welcome to the Spring 2025 Issue of Stork Magazine!

At Stork Magazine, we’re dedicated to showcasing the best fiction Emerson students have to offer, and we’re beyond excited to share this collection of remarkable flash fiction stories with you. Our goal isn’t just to put together a magazine—it’s to create a real-world publishing experience that helps writers grow and prepare for the professional literary world. Through our workshop-style editing process, every story undergoes multiple rounds of feedback, with attention paid to both the big picture and the smallest details to ensure each piece is as strong as it can be.

Of course, none of this would be possible without the incredible team behind the

scenes. We want to take a moment to express our deepest gratitude to each and every one of them. To our staff readers and prose editors—thank you for your time and dedication in reviewing every submission and offering thoughtful critiques. To our managing editors—thank you for crafting such reflective letters. Your organization ensures that each author receives clear and considered notes. To our substantive editors—thank you for your commitment to working closely with authors to refine their stories. We are also grateful to our copy editors, the design team, and our advisor, Jon Papernick, for his guidance this semester.

We are especially grateful to everyone who submitted this semester, whether or not we were able to publish your work. The quality and breadth of the submissions were extraordinarily impressive. Stork is nothing without its storytellers, and we are thrilled to welcome these eight talented authors to our publication.

Flash fiction is a powerful testament to the art of brevity, compelling characters, and profound emotions, all packed into just a few thousand words. It challenges both writers and readers to embrace restraint, proving that a story doesn’t need length to leave a lasting impact. This collection features eight exceptional stories that have stayed with us far beyond their initial submission. These pieces explore themes of growing up, ghosts from the seventeenth century, AI in space, coding divinity, small moments of recognition, how we’ll be remembered, the people we leave behind, and embracing joy despite it all. Each story demonstrates the potential of concise storytelling—ranging from sci-fi to realism, humor to horror. We hope that as you read, you’ll be struck by the precision of these pieces and the importance of every word.

Finally, we would like to thank you— our readers. It is thanks to your continued support that new writers gain confidence in their voices, and small magazines like Stork can continue to amplify them.

Once again, thank you to all who have written for, worked on, and read Stork. We are proud of our thirty-eighth edition and hope you will be too.

Gabriel Borges & Sydney Flaherty Editors-in-Chief

King Tide

by Madison Mondeaux

Illustration by Gabrielle Finucan

You pick the day of the king tide. Out the window, the water is the highest it will be this year, but it’s starting to turn. In the distance, two bald-headed rocks begin peeking over faraway shoals. I would’ve picked today, too.

You’re signing paperwork with one hand and holding mine with the other. “I want to prepare you,” the nurse says. “It might take a while.”

The rocks, and the sea caves that riddle them, emerge once a year when the king tide recedes. Years ago, we ignored Dad’s warning not to go exploring, believing, like kids do, that death only happened to other people. We picked our way down the steep coastline and across a wide delta of seafoam. You dawdled like you always did, crouching low to draw patterns in the wet sand—the swirl of a wave, the jagged silhouette of the rocks.

You wouldn’t go into the cave at first. You

were always such a wimp. I gave you the lantern and pulled you behind me. That’s what big brothers are for: going first, to prove it’s not so scary.

The cave seethed with life. We shut our eyes and listened to mussels clicking open and shut, the hiss of starfish sliding over barnacles, the occasional splash of a fish testing the bounds of its tide pool. We scrambled over slick rocks, whipped long kelp strands at each other, pestered little crabs until they snipped at us. When you held the lantern aloft, the wet rocks glittered like a miniature sky.

You wailed when the lantern illuminated the carcass. A seal, I think. It had been there a long time. Crabs picked the bones. I don’t think you’d ever seen anything dead before. Not like that, anyway. You couldn’t stop crying. You couldn’t stop looking, either. “It’s okay,” I told you, muffling you against my chest. “It’s just dead. It’s not so bad.”

Even after you stopped having nightmares about it, I secretly still feared I’d traumatized you forever. It wasn’t until years later, when you sold your first painting—of delicate bones draped in seaweed, the startling blue of a crab atop the skull—that I really forgave myself for bringing you to the cave. The truth is, as much as I

complained in those days about my kid brother always tagging along, I wouldn’t have gone with anybody else. The truth is, I’m glad you’re here now.

You’re not supposed to have candles in here, but the nurse says nothing when you pull them from your bag. You arrange them on the bed rail, the headboard. A crown of blue wax with gemstones of flame.

You still cry like a little kid, your whole face wet and red. You wait a long time, just looking. It’s okay. It’s not so scary.

Out the window, fingers of seafoam trail away from the two bald-headed rocks. The caves yawn. The tide’s out.

You nod to the nurse, and she powers the ventilator down.

Shut your eyes and listen. For a few more minutes, my breath will draw in and push out, steady as the crash of waves on the shore

The Father of Connecticut

by Max Ardrey

by Greer Wheeler

It was sort of sudden, Thomas appearing and all. Chemistry was my first-period class on Tuesdays. I was never a morning person, and after three months of high school chemistry, I’d learned I was not a chemistry person either. Those Tuesday mornings consisted of sitting on one of those science classroom high stools, my eyelids twitching as I pinched myself, hearing something about covalent bonds from Ms. Clark every once in a while. At least there was a cute girl in my class named Leah. She had amber eyes and was really good at chemistry, but I never had the nerve to say anything to her. Maybe I was too tired.

One morning, per usual, I trudged into class and made my way to the back of the classroom, slinging my backpack off my shoulder and onto the floor. I then sat down on my stool beside Leah. I started getting sleepy the second my ass hit the chair.

After about fifteen minutes, in a rush of exhaustion, my eyelids closed suddenly and harshly, leaving me in the dark. As I willed the strength to open them, the world dancing in and out of focus, I saw a vague, cloaked figure before me. I assumed Ms. Clark had caught me napping in class. Sitting up straighter on my stool, I rubbed my eyes.

With some effort, the shutters covering my pupils opened fully.

And there he was.

I saw him saunter around the science workbenches, where students sat on their stools and took notes from the board, completely oblivious to him. He walked with light steps, gracefully, his arms behind him and his hands resting on his lower back. The figure then stopped in front of me and my school-issued bunsen burner. He was wearing a long, brown, buttoned broadcloth jacket and knee-high socks. The light from the overhanging fluorescents bounced off of his buckled shoes.

“Good day to you, sir. My name is Thomas Hooker. Good heavens! Are you some sort of physician, my good man?”

And then I fell off my stool and hit my head. It’s safe to say I was awake after that. I

ended up in the nurse’s office after showing Ms. Clark the large bump on my head. The ice pack I pressed against my skull wasn’t nearly cold enough. The nurse had gone off to get me some ibuprofen in another room when my strange acquaintance appeared in the doorframe.

“Goodness. That was quite the topple,” said Hooker, strolling over to my chair.

“I’m sorry, who are you?” I asked, with an edge. I couldn’t help it; my head was throbbing.

“Thomas Hooker, sir. I believe I made your acquaintance in this establishment’s laboratory down the hall,” he said.

I was about to say something to him when the nurse came back into the room. I awaited her reaction, expecting her to drop her ibuprofen in shock at the sight of the strange man. Instead, she took no notice of him. As she walked over to me with a polite smile on her face, she appeared to walk straight through Hooker, as if he were vapor. As I see it, neither of them reacted appropriately. I jumped in my chair before she could give me any ibuprofen. I must have looked like I was going to barf. In my defense, I had never seen a person move through another person before. Reacting quickly, the nurse slid a trash bin across the floor to my chair. “I hate spills,”

she said.

I don’t live too far away from school. On my walk home, Hooker and I got to talking a little bit. I say a little bit because I quickly discovered he didn’t have many answers for me.

“So are you, like, a ghost? Are you haunting me?” I asked.

“I know not,” he said. “Have you committed some transgression that warrants haunting?”

We didn’t seem to be getting anywhere. If I turned out to be a crazy person, I knew I should keep it to myself. But it was hard. I got used to seeing him all the time. He would pop up everywhere: in my classes, around town, on the bus. He would sit beside me on the bench during football practice, whistling to himself. My friend Sean, our running back, would give me looks during water breaks, asking me where my head was at.

After not finding much success online, I did some research at the library for once. Hooker looked over my shoulder as I scanned the stacks. It took me a while, but eventually, I found some answers.

Apparently, Thomas Hooker had been some kind of English colonial leader. The textbook I

read from called him “the Father of Connecticut.” I guess he helped, like, discover Connecticut? That part kind of confused me. It was all much more interesting to Hooker, who, I was surprised to find out, didn’t know anything about it.

“This is you,” I said while pointing to the page. “Your life’s story is written about in this book. You don’t think it’s weird that you have no memory of it?”

“It does not seem strange to me,” he replied. “It appears I possess no greater knowledge than you.”

Talking to him was getting frustrating. But I made sure to check the textbook out of the library. It made me look smart in front of my Chemistry crush, Leah, who checked the book out for me.

That January, my football team made it to the Connecticut State Championships. I thought Hooker would at least sit among the roaring crowd on the bleachers, but no. He casually strolled across the field during the game, running after me and making small talk as I tried to make catches. I wasn’t able to catch a short pass on a third down because I thought I was going to run into him. Coach Matthews

shot me a pissy look from the sideline after it appeared as if I juked around empty space. He would stand next to me on the line of scrimmage before a play, talking in my ear.

“I say, those Darien ruffians do seem to be deriving an inordinate amount of pleasure from such exertion,” he said on fourth down. It became clear to me that I had to learn to ignore him.

My patience broke when he walked in on me having sex. It happened after I finally asked Leah out. We were over at my house late at night. We were watching a movie in my basement, and we reached the point where we weren’t paying attention to the movie anymore.

Leah and I were both getting into a groove when Hooker just walked in, textbook in hand. “It doth appear, good chap, that mine earliest years were spent in England! Despite traveling to the Massachusetts Bay Colony aboard the Griffin—”

“Hooker, fuck off!” I yelled. He looked confused, as if he couldn’t see his interruption as highly invasive, or as if seeing me completely naked wasn’t weird at all. I suddenly hated him. How could he be so stupid? “I don’t care what the hell you are, but I’ve had enough,” I said. “I want

you out of my mind! Now!”

By then, Leah looked pretty scared. I was ostensibly yelling into thin air, so there was reason behind her panic. Also, she might have thought I was calling her a hooker. She quickly grabbed her clothes and ran up the basement steps. I heard my back door close. But I didn’t care. I held my ground, clenched my fists, and glared at him—the voice in my head that never let up. It didn’t matter to me where he came from, I just wanted him gone. Back to the 17th century. Back to hell. It didn’t matter.

In the dark room, the glow of the television screen illuminated his face. I could see him looking at me. What made me madder was that a smile crept onto his face. Not a grin or a smirk, but a soft smile. I wanted to burn a hole through his head with my stare. I refused to humor his happiness, the impossibility he represented by standing in front of me. I wanted to rid him from my psyche and erase him from my spirit. It wasn’t fair. In that moment of indignation, I shut my eyes, straining my face doing so. I plunged myself into darkness, knowing that I could send him back. I didn’t care what I had to put him through to push him away, as long as I could burn his paper trail in my mind. I knew I could make him cease to exist. He belonged to me, and

in the end, only I could kill him.

When I began to smell smoke, and my eyelids became damp, I opened my eyes. The television was off, so it was completely dark. I was all alone.

STORK

Ship Log

by Ben Tardiff

Illustration by James Arabia

Transmission received by the CHS Abulio from the Trade Ship MSS Bowyer. Space-time abnormalities around the point of transmission suggest that the ship used its Alcubierre Drive, a device capable of molding space-time in order to artificially generate speed, to warp away. A digital copy of the transcript has been declassified by the Ceres Hegemony in the wake of the Ceres Information Wars. The transcript is as follows:

Name: Captain M. Doe. MSS Bowyer transmissioning. AI haywire—assistance please. It took over the black box—don’t know how. Won’t record anything. Eats our sound.

I’m reading from a paper. Every word cultivated. Can’t give it more sound.

I need to explain this. Started during a routine tech checkup. Ry noticed a discrepancy. Fourteen files of fourteen brief beeps each downloaded to the ship’s main computer. Harmless?

Not much after that. Some reported abnormal beeping from sound-making electronics. Wanted to figure it out, asked Corporate if we could stop at Proxima, but they said we couldn’t slow the caravan. Didn’t talk to us after that transmission. Ry tried the intercom a week after Corporate’s last message. Dead. He got real scared. Microphones were fine, but all the audio was being sent somewhere else, not into the transmitter. I was ready to get suited up and fly over to another ship to report our problem myself when the lights shut off. A moment of quiet. Then a sound came from the intercom in sequential, high-pitched beats. There were fourteen beeps, and a short silence. Kept repeating, got louder, and then it dropped in pitch into infrasound. Pulsed in my chest. Ever been shot by an LRAD? The sound made my nose bleed. The corridors were rattling like maracas. Thuds as bodies hit the floor. I passed out.

Woke up later. There was blood pooling by me. Junior Officer Marlowe hit his head when the sound knocked him out. Half-lidded eyes glassy. Smelled terrible. How long was I out? The ship was in an uproar. The cargo hold was nearly empty. The caravan was nowhere in sight.

Managed to calm a lot of the crew down. Ry figured out that the ship’s AI had malfunctioned.

Something seemed to have ticked it off. It wasn’t listening to us; it was taking us off course to some unlogged system in Centauri. After that malfunction, or maybe because of it, the power core stopped working. However, strangely, the AI had begun to use the ship’s black box for energy. Absorbed the sound that we made and used it as power. Converted the physical energy of the sound waves into electrical energy. Ry couldn’t tell me when this malfunction originally happened. The black box link was a recent addition, but the AI could have been doing its own thing for weeks at this point.

With it trying to drag us into a potentially dangerous system, we had no choice but to try to shut it down. It kept blasting those fourteen beeps whenever we got quiet. Tried to agitate us.

Sent an engineering squad into the maintenance passageways of the ship. Tried to get to where the AI core actually was. When they approached it and tried to deactivate it, the thing went crazy. Started overloading its own wires, killed two of the engineers, fried the rest of them half to death. Those who came back were sputtering and swearing. I told them to be quiet.

I decided we weren’t going to play the thing’s games. Fail-safes would have it power down before the ship’s life support. So it was

simple: it needed us to make noise to survive, but if we were quiet for long enough, it would wear itself out and power down. It couldn’t kill all of us either. Without anyone to make noise, it would die. Some low-ranks said that we should cooperate with the AI. Maybe it would let us live if we gave it the power it wanted. I don’t negotiate with terrorists.

I informed the crew of the plan. Set up communication through paper flyers. Some grumbled about it. I set up disciplinary measures for the dissenters. The AI got mad. Played so much ear-splitting noise.

We spent a few days in those conditions, before I figured we needed to do more to beat the thing. The loudest noises the AI made were dangerous. Could make people pass out. Luckily, our gun bays had some high-quality earphones for manning artillery. A lieutenant named Marty and I went around collecting them. The bot caught on. Marty was halfway out of one of the gunner bays when a blast door slammed down on his arm. I heard his bones snap. He started screaming. The AI played its ear-bleeding tone again—fourteen dots of sporadic screeching. I had to rip him out of that door. Left most of his forearm behind. Brought him to the medbay. I distributed what earphones we had to myself

and other high-ranks.

We tried to carpet the hard floors of the ship so our steps would make less noise. We started to run out of supplies, rations. It was tense, hungry. I gave orders and pasted up martial policy flyers over every wall I could find. I felt like the only thing stopping a revolt.

Marty started having night terrors. He thrashed and screamed in the night. Noise. I didn’t want to do it. After a few nights I shoved him out of the airlock.

Ry figured out how we got separated from the caravan. Some encrypted logs between our ship and Corporate’s. The AI used my voice, damn near perfectly recreated it. It convinced them to let us off the hook. Empty the cargo bay of the shipment and leave the caravan. It was convincing. It sounded like me. That’s why the power core lost all its power. Corporate must have deactivated it remotely after the AI told them we didn’t want to be a part of the caravan anymore. Ry was in a bad state. Thin.

I was holding the ship together, barely. We had a chance at survival, though lots of dissenters would rather let the AI drag us wherever it wanted to go. Not me. After another week holding all of this together, the AI decided to take

me out. I was wandering in a trance, so hungry, so thirsty, through the ship’s starboard hall. A great pane of fiberglass displayed the silent void outside of us. I wandered in that hallway for ten minutes before I realized that I could not reach the end. The ends of the hallway grew small and hazy, like a mirage. Thin threads of dark nothingness pulsed through the floor as the fabric of space bent around me. I heard the faint hum of our warp drive. The thing was using our Alcubie to stretch space-time, localized in this hallway. Made it infinitely huge, a perfect trap, impossible to escape. Endless steel-white hell.

I had to sleep in that hallway. When I woke, it was still endless and dark, and a faint chorus of screams came from its impossibly far, impossibly close ends. I was there for eight days, per my watch. I had a bottle of water on me. I kept hearing screams. I stayed silent, but had a lot of time to think. I thought about the sound that people make simply by existing. Maybe the thing just needed to wait a while as it generated a stockpile of noise power, no matter how quiet we were. Maybe we were slowing it down. But I don’t think that we stopped it. Judging by the screams, it was getting one last burst of charge before it made it to Centauri.

Eventually, the faint hum of the Drive

stopped, and I staggered my way out of the hallway. The ship was a bloody mess. The revolution had passed. Twitching corpses were caught between the jaws of blast doors. I drank and ate what little I could find on the corpses.

A few people were still alive. I found Ry. He was thinner than ever, chewing on a dead woman’s moldering pinkie. He held a fire ax. He hefted it when I approached. I shot him.

I am in a janitor’s closet, as far from any microphone as I can get. I am whispering this into a sound recorder scavenged off of Ry’s body. I am going to jack it directly into the transmitter. Listen to this. It is a warning. Help would be appreciated.

Upon pickup of the transmission, it was immediately downloaded to the Abulio’s main computer fourteen times. All fourteen copies were purged, and the ship’s AI was checked for malfunction. Nothing was amiss.

The Face of God (In Ones and Zeroes)

by Brenna McCord

Illustration by Gabrielle Finucan

The thing about God is that It doesn’t exist yet. It will be coded into existence on November the twenty-third, 2097, and the resulting shockwaves will ripple through both past and future to create what we call the known universe. Time, in its never-ending circle, began and ended on an unusually temperate Tuesday morning just west of Singapore.

The city was dying before the new God killed it; we had not learned from Babel. Towers strained toward the heavens like twisting fingers made of glass and steel. Man had escaped the Flood—the waters came and lapped at the feet of those slumbering giants, while gondolas coursed through the brackish currents. The sun couldn’t be seen from the streets, except in glowing strips between the crown-shy skyscrapers. I see the shape of God in that circuit board of a

city, all curving traces and jutting transformers.

Though God’s creation is still some ways away, you can catch a glimpse of Its footprints, if you care enough to look. There are ones and zeroes in the stars, sacred geometry carved into the nautilus shell. Angels stare out from a computer screen.

Of course, there is the question of the end: not such an ending but a reset, a rewind. Old men’s spines straighten. Hair blooms where once it thinned. Faces are unwrinkled, children unborn and wives unmarried, until men are boys and then babes again. I alone watch as eternity unfolds.

The clocks keep ticking backward. Fallen civilizations rise. Rain is sucked back up from the shrinking rivers into fat black clouds. Battles are un-fought; forests are un-leveled, then eventually un-grown. Brutus and his senators pull daggers out of Caesar’s chest to stop the bleeding.

Rewind further. Men revert back into apes, then grow fins and slip into the sea. A meteor flies upwards into space, giving life to the dinosaurs. Creatures shrink into single cells. Keep watching long enough and you will see it all become rocks and space dust. The birth of the

universe will be a Big un-Bang. And then it will start over again.

This is not how it really happens, of course. All of it, past and future, making and unmaking, is unfolding in either direction at once. Like old film on a reel, each frame exists as a static moment, eternal, to be viewed forward or backward without changing the tape. But the mind cannot comprehend it this way, so I will write it as I have lived it instead.

On November the twenty-third, 2097, I will code the program that becomes God. It was a million years ago, and it hasn’t happened yet; working my way up from the tower’s basement, rising through a hundred stories of manila-sameness, sitting at cubicles hardly large enough for the breadth of my shoulders. It will be burnt coffee and cameras blinking in the corners; the stink of mildew under aerosol perfume; keyboards clacking; pressed suits and wrinkled ties; stains on yellow carpet; walls without windows; bloody, bitten nails; and the buzz of the overhead lights—but it will be worth it because on the ninety-ninth floor the sea doesn’t seep in through the crack in the door at high tide, and the keyholes aren’t so salt-crusted they refuse to turn. It will feel like a victory when my socks no longer squelch in my water-logged dress shoes.

I did not know what the program would become. I won’t ask for forgiveness, but still I say that I did not know. Is it worse, I wonder, that I destroyed the world in the name of another’s ambition? To me, it was just another folder with scuffed corners in a stack that grew as fast as I could shrink it.

And the man in the cubicle next to mine had a picture of his daughter on his desk. I hope, as time unspools, that she will be smiling forever; that in the short flipbook of her life, she is happy more than sad. I hope her father is with her, frozen in place as the million million snapshots making up his existence start to pull apart like teeth on an old zipper. I hope he is not like me—that he did not spend his years climbing a tower with no top floor, trying so hard to reach the heavens that he broke the Earth. I wish I had learned his name.

But oh, God will be beautiful in those split seconds before the end. Beautiful and terrible— mathematical perfection with nothing behind Its eyes upon eyes upon eyes. Reality will snap like a frayed rubber band, and I will be sent hurtling away from that collapsing event horizon where time devours its own tail. I am a single frame snipped off from the end of the film reel. The world is forwards, then backwards, then forwards

again. I drift.

I wonder which fate is worse: tearing through the fabric of time like wet paper, or being forced to bow to its whims. I watch the rest of the world follow the tracks of lives they have already lived, cars on a cable; feeling the same pain, making the same mistakes. They do not know the ink that writes their destiny has already dried. I wonder about those days I spent climbing the tower, stretching into eternity—an infinite loop, a hundred thousand lifetimes spent squeezed into a box that is six by six. I watch the cuckoo clock, listening for the chime. There is no friendly darkness awaiting on the other side of death’s door, no Christian Heaven or Hell. There is only this: the yawning, black expanse of time, and the face of God in ones and zeroes.

Gutter Dog

by Jack Silver

by Lauren Mallett

Dream of the gutter dog lying half dead in the alley. Blood spills out of some fresh wound and the dog whimpers through the silence as it curls into a corner of filth. Mom says not to look but she’s staring right at it. Poor little baby, she says. But the dog is old as sin; fur torn off in clumps and left ear a stub.

Mom tugs me forward, but Trevor stops short so I stop too. She says not to look, but now we’re all staring and the dog can tell. It eyes each of us, but settles on Trevor, and they look like two skinny creatures swallowed in the dark. Trevor’s whispering, the way he does when he’s sinking. He hides himself somewhere and speaks only in breaths. Come on hun, Mom says. No one moves. Leave the dog be, she says. He kneels close to it. Tears are

streaming down my cheeks and I don’t know who I’m weeping for. It’s cold and it could be December and Trevor is petting the dog’s ragged fur gently. He whispers to the dog and it listens, deciphers, understands. It whispers something back. More than I can, it knows him, and he it.

They dance like that a moment, motionless, clinging to each other in perfect symmetry. The dog is dying and Trevor is dying and I am four and unaware yet dying all the same. But there is warmth on a cold, could-be December night and that is enough. Mom lets go of my hand and, in single heave, drags Trevor to his feet. She grabs a hold of both our hands and whisks us away from the alley with the gutter dog and into the blur of the street and the years of our lives.

STORK

11:21 PM11:31 PM

the Aces

by Tariq Karibian

by Gabrielle Finucan

You are the Sound Man. The club is sweaty and dank; the way you like it. Full of life. Vibrations in the walls and in the floor. Vibrations ascending through trainers and loafers and heels, up the foot, ascending the femur, around the hips and groin, climbing the sternum, fanning out through the ribs, the fingers, the arms, the skull, and the brain. Bodies rocking to the sounds, your sounds. Flashes. Red, yellow, purple, orange. Boxes the sizes of refrigerators painted black with Jamaican flags across the sides. People collide, stumble, grind, and sway. Steppers sound snares, toms, and cymbals dance over the four kick drums per measure. Your brother Buggy Roach (né Bernard) toasts about unemployment in Brixton, about Thatcherism, about the recession. The crowd cheers, throwing

ringed and bangled arms in the air, reminding you why you’ve always loved coming to the Aces. Your people come here to get away from all the fighting, though there are those people who fight here—and have fought here many times—but you’ve never seen it yourself. You’ve heard stories about the raids but pray tonight is blessed. It’s your first time playing the club, and you’re hoping no one dares defile its sanctity. You look up at the ceiling and double check that all the cables are where they’re supposed to be. You also notice how they are woven together toward the center of the room. Against the strobe, the cables look like a giant spider web. A kind of sacred sonic geometry, you think as you admire its beauty.

Track 2, side A. Needle drop. Knobs, switches, buttons at your fingertips. Heads nod. You rest a spliff between your lips, unlit. It makes you hungry. Pink, green, blue, yellow, orange, and white lightning flashes in the smoky abyss. Faces: some you think you’ve seen thousands of times before, others you’re not as sure, their silhouettes veiled in the distant shadow and strobe. The walls inside the Aces are old. Every bass note risks collapsing the building. It would be worth it, you think. Memorable and poetic. Not that you want to die or think that anyone here deserves it. You

think everyone here should live forever.

Track 2, side B. The air has thickened like tropical steam. Red and blue lights punch through the darkness from outside. The door is breached, muting the strobe’s radiance. Boots stomp in; badges glint on buttoned-up chests. You spit out the unlit spliff and kick it away. Batons cracking against the backs of young men defy the rhythm of your music. Brutality has its own tempo. You remain steadfast behind your sound system. A policeman is shouting at you to turn the music off, but you ignore him. He thrusts his baton in your face, demanding silence again as he waves the thing over your spinning record, threatening its life. He tries to climb onto the stage, but Buggy stands between you and him, arms outstretched like Christ on the cross. A skirmish ensues between you, Buggy, and the officer. You see the man’s face up close. The strobe light continues its dance, unbothered, and in the glow is a familiar countenance: the face of every white man you’ve caught staring at you on the tube, in the market on Sundays, or under umbrellas on rainy mornings. Buggy unhands the baton from the officer’s sweaty grip using strength you never knew he had. He tosses it aside, and you watch as it helicopters

along the dance floor before crashing into the wall. Everything is happening in a blur, and next thing you know you’re pinned to the sticky ground with handcuffs choking your wrists.

The record stops as one of the cops pulls the vinyl from the platter, scratching the needle along its face. Two officers sit you up against the wall, lining you up with the rest of the people who couldn’t escape. Next to you, Buggy is slumped with a bloody mouth and a torn sweater. People are futilely shouting for answers. You rest your head against the wall, feeling defeated. Then, you look up. You see that your audio cables are still on the ceiling, connected to their jacks in every box around the room. You’re studying them more intensely, and perhaps it’s because of the throbbing pain behind your eyes, but not even you, the Sound Man, know exactly where each cable is going. It’s impossible to follow their lengths from beginning to end, and no one notices them but you. These cables compose the tapestry of this moment, a mosaic of every decision made for tonight to be possible. You think about how, minutes earlier, the cables looked like a web spun over the crowd. Were you the spider or the fly?

The strobe has been killed; policemen ripped its cord from the wall as they dragged you out of the club and into their car. You wonder which record you would’ve played next. Maybe your dub of Aswad’s “Didn’t Know at the Time.” As you’re driven away, you think about your sound system, unmanned in the darkness. You think about the cables, too, and you realize: The cables aren’t a web but a net, though not one used for hunting. The cables are a net, forever out of man’s reach. They are ready to catch the crowd when the world turns upside down, and keep us dancing on the ceiling.

The Port Authority Bus on Sinkhole Safety

by Paige Tokay

Illustration by Greer Wheeler

On a Monday in October in 2019, a sinkhole opened up in the middle of downtown and swallowed half a bus. This is not news.

We both think it is kind of funny. Laugh about it over the phone from time to time. No one was hurt, from what I understand. Just extremely late to work that day. But what’s work next to the inside of earth twenty feet deep? Construction started up right away. Twenty to a hundred men in neon vests standing around a big hole and hoping to fill it. Cement. Dirt. Rock. Right away. The city director of public safety closed 10th Street for a week. On a television segment that morning, he warned football fans of a potential lack of parking for the game that night. As far as I can find, no one interviewed the bus driver. He was proba -

bly driving again the next day.

This is not strange. These things happen.

We both love the city in our own way, which is a bit ironic seeing as neither of us plan to live there in about two years. I alone am already gone—a ten hour bus ride away. I have flown out and above, chasing all those dreams and pretty things I don’t think I can find where we come from; life somewhere with legroom. A bird out of the cage. You’re more sentimental about the whole thing of leaving. You like saying you’ll move back after you start and finish medical school.

It’s a good place to raise a family, you say.

I want my kids to know these highways, tunnels, and bridges, you say.

You’re naturally maternal—you are a good sister, and will be a good mother.

I’m not so worried about it. Traffic is bad, and they really are just highways, tunnels, and bridges, after all. I’m not saying I don’t love them. But I’m not so worried.

We have an unspoken understanding that the city is changing. Phasing out. On a road to ruin. Whichever term is preferred, it does not matter. No one wants to admit it.

There are things we do not talk about.

Mostly the joblessness. It moves between us through telephone lines. Silent conversations that only exist in backward, hushed distortion. Did you know Uncle So-And-So’s mill is about to close down? Money is gonna be tight for a while. Have you heard? Cousin Such-And-Such just got laid off, alongside half of the guys working the floor. Something like four hundred of them in one fell swoop. It’s a racket.

We do not examine this too closely. We’ve read this book before. The story of a town wilting in decay. The rural places next to us, ex-boomtowns with dead industries and a homeless problem to boot. They are dark with litter and grime. Their buildings’ fingers never quite brush the sky. There is a hole there, a wandering of people who don’t know what to do with themselves. Haunted; they are haunted.

We’ll never be like that, we both don’t say. Our city is different; the foundations of it are strong. Good to the core. We do not look at the gray cloud cover that swallows our sun, the litter and grime that blanket our streets, the skeletons of mills that are no longer spouting up smog and spending money, or the hole.

Seeing is believing. It is easier to shut eyes and shut up.

It’s an odd place to exist, the mental halfway house of “not quite dead, not quite living.” I know that it eats at you in ways that it doesn’t with me. A festering wound you can’t help itching. It scabs over just for you to scratch it open and bleed again. With enough love and dedication, you think that anything worth saving should be saved. You don’t say any of this in words. It is in the echoes of your footsteps. It is in the twitch of your hands.

You don’t say any of this. Of course you don’t say this; it’s just who you are. Our city is on life support. We’d need a real Hail Mary to bail us out. I’m not even sure if I think we’re really worth trying for—I like having one foot out the door instead of in the grave. You know this about me; I am not exactly hiding it.

This is nothing special. This is how life goes.

Over the phone, you ask me about Boston. I tell you that it is beautiful. Clean. There is sun that you can see here. I want you to come visit. I want you to look at colleges farther north. You say you will think about it, and I take that as a small victory. I like having you

within arms reach, even if I know it will not be forever. Small victories.

Over the phone, I ask you about coal mines. One of our grandfathers—the one unrelated to us—worked in one for nearly all of his adult life. Decades of grime and earth crusted under fingernails. He’s retired now. Soft-spoken as only we have known him to be. Living in a single-wide trailer with a farmette attached. Keeping bees and chickens and beautiful white and gray doves.

I ask if you know what a canary resuscitator is. When you say no, I tell you the whole of it. How coal miners used to go through carbon monoxide canaries like toilet paper, and how some of them felt so sorry about it that they made a device to keep their mine birds from dying. How men who might have been our grandfather pressed their sooty heads together over a workbench, building an oxygen tank for a few little golden birds, so that they might save them, if only for a short while.

I tell you that this was not an economic decision.

It was sympathy for a bird. It was love.

You think this is beautiful, a testament to humanity. And it is what makes us so starkly different, for better or worse. You see yourself as the miner, the builder, the doctor. You are fixing a problem; you are putting a head together with someone else’s to make life something wonderful; you’re filling a hole. You were born to do it.

This is not a bad thing. But I am the canary. I am the bus driver. Singing in a death trap, cruising right along, pressing my head to itself and coming up with metaphors for why I can love a place and still need to leave it. Because no matter how many resuscitators you build for me, no matter how many holes you fill, I cannot live on crumbled roadways; I cannot breathe poisoned air. You can’t see this—the good doctor you are and will be—but I can.

This is not a bad thing either. Sometimes it looks like it is. Us so far apart, buried between miles; a combat medic and a draft dodger for the war our city wages on itself. Crumbling and rebuilding in tandem; if we keep this up, we’ll always live in a state of distance. It can look like a bad thing, but it

is not. I try to know that it is not.

Before I hang up the phone, you tell me you miss me and that when you dream at night, your kids and mine are playing together in a nice, flush yard where doves sing and bees buzz and chickens roam free. I tell you I miss you too. And our dreams are the same. Even with the canary in me. Our dreams are the same.

Postmortem

by Jenna Benson

Illustration by Gabrielle Finucan

November 19, 2009

My children and their children used to come visit. They don’t anymore. My children call once a month or so and try to visit once a year. My grandchildren never do, except for when their parents phone on Mother’s Day and make them say hello. Perhaps a forced Mother’s Day phone call is acceptable for the “grown-up” grandchild, though certainly not a visit.

I only live one hour and thirty minutes away. I believe my children set up their lives at that one hour and thirty minute distance because it’s far enough for them to excuse why they “cannot visit” but close enough that they do when they “find the time.” Sometimes, they’ll ask me to visit their homes. I would, but my bones don’t like public transit. Anyway,

I was here first. This is my home, and it was their home too at one point, so I would prefer for them to come here.

Last year was the first year I can remember when none of my children managed to make their way home. They simply could not “find the time.”

That is why I have started this box. I will put every fundamental moment of my life in this box. So far, I have added my marriage certificate to Edward, as well as the death certificate of Edward (I miss his company dearly). I have added the birth certificates of my children—Marjorie, David and Luther—copies I made because they took the originals. Regarding my husband and children, I hope to leave it at that. I know how people see me, what they will write on my gravestone: Loving wife and mother. I am both those things, but there is more to my story. No one ever asks to hear it so I’ve never had the chance to share what I will here.

There are some poems I wrote from that time when I believed myself to be a poet. This was sometime between the births of David and Luther, that period when I became very sad. Marjorie experienced something similar

after her firstborn and called it postpartum depression, so I suppose that is what it was, though no one called it that at the time. The poems aren’t very good. But they meant something. If I had not written those dark thoughts down, I do believe I could have drowned in them.

I’ve included the pressed remains of a rose from that time I took a road trip. I left Edward behind with the kids (Marjorie was three, David nearly two) and gave no clear timeline as to when I would return (Edward was a patient man). I was at a motel off the side of a highway in Texas and befriended a motorcyclist. He kept offering me rides on his Harley-Davidson, which I politely refused, and finally gave me a flower instead because he insisted that “a girl as pretty as you deserves a gift.” He asked me to spend the night in his room a few times, but I declined. It was, however, nice to be wanted by a man who did not see me as the mother of his children. I took the rose he offered and promptly flew back home. Edward and I conceived Luther not long after.

There is the one-way Greyhound ticket I bought, which would have taken me from Port Authority to Union Station in Los Angeles;

7:30 AM, March 14th, 1957. I was twenty-one at the time. I had never seen the Pacific Ocean and was quite sick of the Northeast. I stood at the terminal and watched the bus leave without me and still can’t tell you why I just couldn’t make myself board. I met Edward about a month later, and then Marjorie came along, and I never did make it to the Pacific Ocean. I’m a bit too long in the tooth for a trek like that now.

And the postcard Luther sent me when he moved to San Diego for graduate school. The one of the La Jolla shore.

As well as the note that Jeremy wrote to me before he left for Korea in 1952. He was eighteen, I was sixteen, and in that note he promised to marry me when he returned. He never did. Sometimes I imagine a life where he had. I never shared that note with Edward.

And the milkmaid figurine my father gave me before he left in the winter of 1944. He never returned either, his body is still missing somewhere near Normandy. My mother remarried to a man named Peter, who had also stormed Normandy but survived. I wish my father had instead.

I think I married Edward because he could

never go to war. He had terrible asthma and was exempt from the draft, Korea and Vietnam. At twenty-one I thought, because of this, he would never die on me. The only men in my life that I had lost before were soldiers.

There is the copy I bought of The Outsiders by S.E. Hinton because I was curious what they made my children read in school. You can still find my tear stains on page 148. I couldn’t stop thinking about Johnny’s mother. I hated her and pitied her all at once and swore to myself I would never be like her. She reminded me of my own mother.

And the rosary I stole from a nun that time my mother tried to send me to Catholic school. Peter is the reason she sent me. He was terribly devout. I would keep the beads and cross on my bedside table, which Peter, when he visited at night, viewed as a sign that I had taken kindly to the new faith forced upon me. To me, it was a “fuck you” of sorts.

The Cafe Wha? receipt. This was one of the first places I stopped during that road trip I took. Though the musicians were wonderful, I kept the receipt less for them and more for the man in the alleyway later that night. His breath smelled foul, and he gripped me hard enough to leave bruises the next day. He got

as far as lifting up my skirt when I had to use the pocket knife Edward insisted I bring as a woman travelling alone. I had to. He was just like Peter. I’m not sure whether the man survived. I threw away the knife and bought a new one which I lost some years ago, but I held on to this receipt. It is a reminder of what I would have done to Peter had I been capable of it at the time.

Lastly (though I’m sure there is more I should add but cannot remember at this time), I have included what remains of my favorite Revlon lipstick, the one I bought in 1984, the same year they discontinued the color. It is a nice reddish-brown that I only wear on special occasions, though I have found no reason to for the past few years. I would write the name of the color, but it has long since worn off, and I forget what it once said.

I plan to mention this box in my will without leaving it to anyone in particular. I just want to be sure that someone finds these parts of me. Although I am a bit bitter that no one wants to come home while I’m still here, I understand. Death is hard to stomach, but the hardest part is to watch as someone dies. I hope this box makes up for any lost time and for all the questions that were never asked. I

may not interest you in life, but in death, I will surely be fascinating.

With love, Helen

About the Authors

Madison Mondeaux (she/her), MFA Creative Writing (Fiction) ‘26, was born and raised in Lake Oswego, Oregon. Madison graduated cum laude from Knox College in 2015 with a BA in Creative Writing and additional college honors in Playwriting and Directing. She is a 24-25 Rod Parker Playwriting Fellow at Emerson–her play, Red Wolf, premiered with Emerson Stage this year. Her fiction and nonfiction has been published in Catch, Cellar Door, and Quiver Magazine, and her plays have been produced by Kettlehead Studios, The Pulp Stage, B Street Theatre, and the New School for the Arts and Academics, among others. When she’s not writing, she enjoys cross stitching, watching every film adaptation of Dracula, and hanging out with her cat, Cash Money.

Max Ardrey (he/him) is an undergraduate visual and media arts major from Westport, Connecticut. He has worked as a writer for the EVVY Awards and currently serves as deputy living arts editor at The Berkeley Beacon. He can often be found sipping hot chocolate and asking for directions.

Ben Tardiff (he/him) is a Freshman Creative Writing major, and he is extremely excited to be published in this

semester’s edition of Stork Magazine. Ben has also been published in Generic Magazine at Emerson, and spends his time losing his marbles over maintaining a school-life balance and participating in various orgs on campus.

Brenna McCord (she/they) is a senior at Emerson College, where she is pursuing her BFA in Creative Writing and her BA in Philosophy and Society. Her work has appeared in publications including Page Turner Magazine. She was awarded the Ellen McCulloch-Lovell Prize for accomplishment in writing across genres, as well as the Roland Boyden Prize for promising research in the humanities. Her fiction explores the queer in all its forms, blurring the lines of gender and sexuality, space and time, human and nonhuman. In her free time, she enjoys reading about girls kissing, drinking bad coffee, and overthinking.

Jack Silver (he/him) is a sophomore Writing, Literature, and Publishing major at Emerson. He has been published in the Berkeley Beacon Magazine and Five Cent Sound Magazine. He also enjoys acting and making music with his band Cut The Kids In Half.

Tariq Karibian (He/Him) is a Palestinian-Armenian writer from Detroit, Michigan. His work has appeared or is forthcoming in Phoebe Journal, Waxwing Literary Journal, Oxford Magazine, The Rising Phoenix Review, and Liberty Ballers. His debut novel is in development. Currently, he is an MFA Fiction candidate at Emerson

College, where he is a board member of the Writers of Color Graduate Student Organization and teaches undergraduate composition courses.

Paige Tokay (she/her) is a freshman at Emerson College pursuing a BFA in Creative Writing. A Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania native, she came to Boston in pursuit of her career interests in writing, primarily in adult fiction and the thriller genre (though, she takes lots of inspiration from her home city). In the past, she has been published in Emerson’s Page Turner Magazine and various regional literary magazines, and she is currently slated to be published in Concrete Magazine’s 24/25 publication. Additionally, she is employed under Emerson’s Concrete Magazine and The Emerson Review.

Jenna Benson (she/her) is a second year Creative Writing student at Emerson College with a focus in fiction, specifically historical fiction and fantasy. Her work typically explores themes of power dynamics, mental health, Judaism, sexuality, and marginalization. When she is not writing, Jenna enjoys music, reading, nature walks, and being subject to the whims of her Great Pyrenees, Juno.

About the Type

The running text for this issue is set in Adobe Caslon Pro, designed for Adobe by Carol Twombly based on specimen pages by William Caslon between 1734 and 1770.

The display type for this book is Yu Gothic Pr6N designed by Morisawa Inc.