Fall 2022 ISSUE • VOLUME 33

STORK

Stork Magazine is a fiction journal published by undergraduate students at Emerson College. Initial submissions are workshopped and discussed with the authors, and stories are accepted based on the quality of the author’s revisions. The process is designed to guide writers through rewriting and provide authors and staff members editorial support and an understanding of the editorial and publishing process. Stork is founded on the idea of communication between writers and editors— not a simple letter of rejection or acceptance.

We accept submissions from undergraduate and graduate Emerson students in any department. Work may be submitted at stork.submittable.com during specific submission periods. Stories should be in 12-point type,double-spaced, and must not exceed 4 pages for the “flash fiction” issue. Authors retain all rights upon publication. For questions about submissions, email storkstory@gmail.com

Stork accepts staff applications at the beginning of each fall semester. We are looking for undergraduate students who are well-read in contemporary fiction and have a good understanding of the short story form.

Copyright © 2022 Stork Magazine Cover design done by Katherine Fitzhugh

Illustrations done by Hannah Meyers and Katherine Fitzhugh

Typesetting done by Eden Ornstein and Aubrey McConnell

Editors in Chief Nina Powers Hannah Meyers Managing Editors Cindy Tran Kate Rispoli Head Designer Eden Ornstein Design Team Katherine Fitzhugh Aubrey McConnell Jessie Jen Head Copy Editor Anna Carson Copy Editors Ella Maoz Maggie Lu Chris Chin Sage Liebowitz Prose Editors Michelle Moroses Sara Fergang Sage Liebowitz Chris Chin Staff Readers Gabriel Borges Dana Guterman Levy Sam Kostakis Jessie Jen Ryan Forgosh Anthony Ortega Charlize Triozzi Sydney Flaherty Gabel Strickland Aubrey McConnell Ruth Fishman Social Media Manager Georgia Howe Faculty Advisor Stephen Shane

MASTHEAD

Letter From The Editors

We have a tradition at Stork of finding the best fiction that Emerson College has to offer. This year, we have once again continued this tradition. We are pleased to present you with the thirty-third edition of Stork Magazine, containing five marvelous stories written by Emerson authors. With witty dialogue, lush prose, and a touch of humor, all five of our authors have given us incredible fiction that we are eternally proud to publish.

For their endless dedication to the art of fiction, we would like to thank our wonderful Stork team. We truly could not have put out this issue without you all. To our readers, with your insightful conversations and a keen nose for quality fiction. To our copyeditors, with your tenacious grip on grammar and desire to make Stork as polished as it can be. To our designers, with your boundless creativity that continues to amaze us over and over again. Our staff are the heart and soul of Stork, and we could not thank you enough. Thank you, especially, to our authors, for allowing us to share your writing with the world, and a final thank you to all who submitted to Stork this semester. Although we had to pass on so many wonderful

stories this semester, each and every author who submitted to us is supremely talented in the art of fiction, and we honor your vulnerability in allowing us to read and critique your writing.

Although Emerson will never be what it was before the pandemic, this semester is the first in which we have attempted a return to normalcy since the beginning of the pandemic. For many of our staff, this semester was their first time having consistent in-person Stork meetings, which brings an entirely new set of challenges as we have attempted to adapt to a new definition of normal. Time and again, our staff has impressed us with their flexibility and determination to put out this issue. You have worked tirelessly to make this issue a reality, and we are now proud to introduce you to the most recent edition of Stork.

As we have begun reconnecting with one another physically, whether through in-person meetings or newly mask-less faces, our featured authors have presented fiction that explores the body in a variety of ways. Whiskey burns in the throat, eyes glow from the roadside, green goo bubbles, a dog opens its jaw and bites. Follow five tales that push the literal and figurative boundaries of the human body, and don’t forget to check your posture in the mirror.

Once again, thank you to this semester’s incredible authors for trusting our team with your work. These stories contain inspiring vulnerability and depth, and we hope you all enjoy them as much as we have these past three months!

Nina Powers and Hannah Meyers Editors-in-Chief

Fall Fiction 2022

CONTENTS

Tiger Lily

By Rita Chun

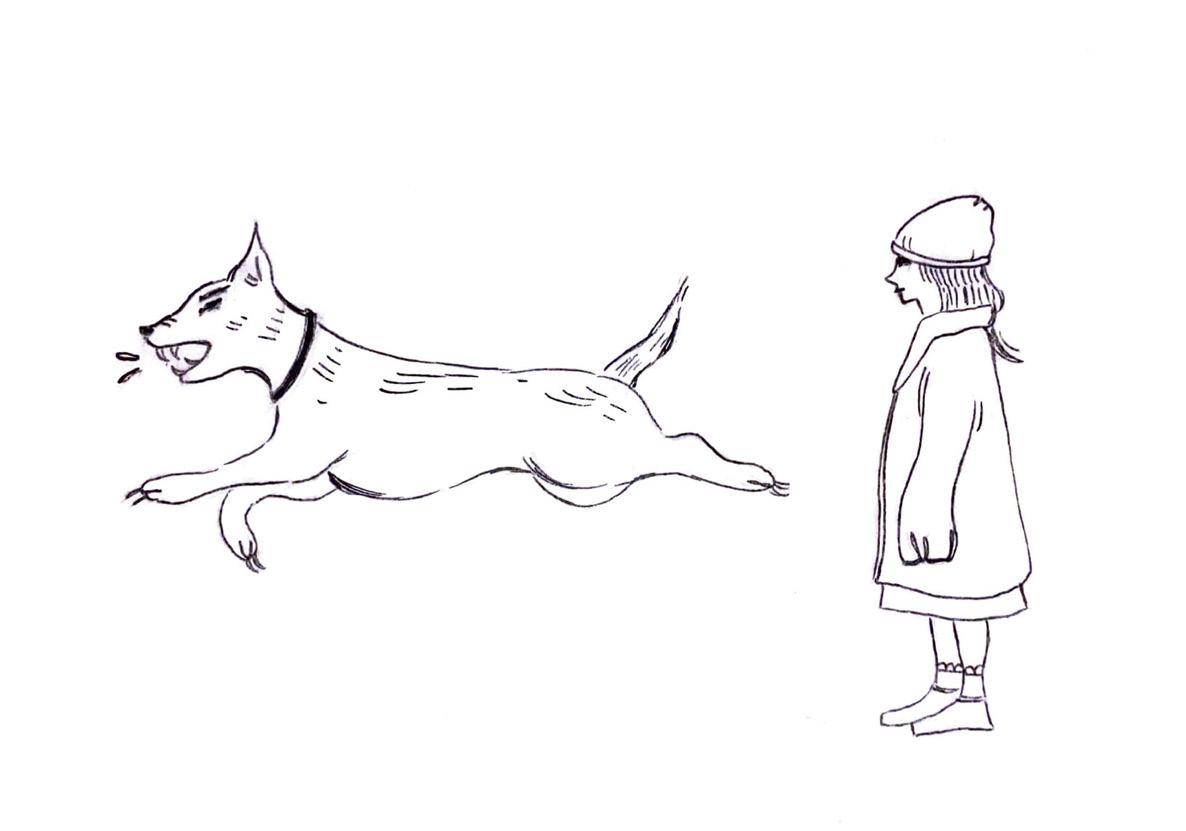

Illustration by Hannah Meyers In The Red Parlor

By Anna Carson Illustration by Katherine Fitzhugh Roadkill

By Margo Heller

Illustration by Hannah Meyers horror story (true story)

By Marin / Spencer Madden Illustration by Katherine Fitzhugh Repetitions

By Abbie Langmead

Illustration by Hannah Meyers

43 63 75

31

13

Tiger Lily

by Rita Chun

Illustration by Hannah Meyers

Adozen cans’ worth of Spam lies in a glorious heap, all cut into bite-sized cubes. The pink lumps gleam as their oily juices ooze onto the wooden chopping board.

I open the cupboard and pull out a bucket of extra-strength rat poison. I unscrew the lid and inhale sharply, letting the wave of garlic and fish shoot up my nose. I love the scent of phosphine.

I push a pellet of rat poison into each Spam cube and place them in a Tupperware box. Now, I’m not counting, but I think I’ve got at least a hundred bait cubes in here. Thinking about the deaths they’ll cause makes me smile.

I rinse my hands off, then change into my costume: a pair of gray overalls with mud stains on the knees, an old baseball cap, and a pair of work boots that are a size too big. I place the Tupperware box in my gardening bucket and toss in a small spade for good measure. Then I’m

13

out the door, whistling a hooligan tune, bucket swinging in my hand.

“You’re that dog killer, aren’t you?”

Startled, I whip my head around. A teenage girl stands over me, arms crossed over her chest. She must’ve crept up behind me. What a sneaky little bitch.

“What dog killer?” I ask. Pretending to be a busy gardener, I grab the hand spade from my bucket and start shoveling dirt over the handful of bait cubes I had just placed under a bush.

I keep my head lowered and glance around. Luckily, the park is mostly empty on Tuesday afternoons. There’s a middle-aged couple on a stroll, but they’re not close enough to hear anything.

“You know, that sicko who’s going around poisoning dogs? It was on the news. You’re that sicko, aren’t you?”

“No, I’m not.” I push more dirt around with my spade, scooping it up then patting it flat in a way that feels professional. “What’s that, then?”

From my peripheral vision, I see her pale finger point to the Tupperware box of bait cubes inside my bucket. Shit.

“It’s fertilizer,” I say, standing up. I tower over her, and I position myself so she can’t look

14

into my bucket. Her big, loony eyes are like camera lenses, framed by freckled cheeks and long ginger hair.

“No, it’s not.” The girl starts reaching towards the bucket.

I grab her arm and grip it hard. “Yeah, it is.”

She screams. The sound pierces through the park like a shrill whistle. The middle-aged couple stops and stares at us.

I quickly drop the girl’s arm. “Sorry, she’s just really scared of spiders!” I holler, pretending to brush away a spider on her shoulder. Then I look at her, shake my head, and say loudly, “Don’t be stupid, spiders can’t hurt you,” and pat her on the head, hard. Then I smile at the couple.

They smile back politely. “She’s scared of spiders, too!” the man hollers back, and pats the woman on the back. She snorts, and they walk on.

“What the fuck is your problem?” I whisper to the girl.

“Says the serial dog killer.”

“Shut the fuck up. I’m not a serial dog killer.” I grab her wrist again and her eyes widen. They’re so thick with eyeliner that she looks like a racoon.

“I’ll scream again, and this time I’m gonna scream that I found the fucked-up sicko serial dog killer.”

15

I let her have her arm back.

Her thin red lips curve into a grin. She’s wearing a long orange skirt with brown polka dots and a tank top that says ‘Peace and Love, Baby!’ in wonky Sharpie letters. She sticks out her hand. “Give me two hundred bucks.”

“What?”

“Give me two hundred bucks or I’ll call the police and report you. I’ll tell the local news, too. Everyone’s gonna hate you. They’ll track you down, all the owners of the dogs you killed. They might even kill you. I mean, you deserve it. Maybe if you only killed a dog or two you wouldn’t. But how many have you killed? You’ve been doing this for months now, haven’t you? How many dog souls do you think equals one human soul?”

There’s nothing in her glinting eyes that tells me she won’t call the cops.

“I don’t have two hundred bucks,” I say. She looks at the dirty overalls I stole from a thrift store and the beat-up work boots I took from a construction worker who was distracted, soaking his feet in a public fountain.

“You kill dogs, you’re dirt broke . . . You’re a sad, sad man, aren’t you?” A deep crease forms between her brows. She presses her lips together and places her hands on her hips. The top of her head barely reaches my shoulder, but she’s

16

looking down at me somehow. I want to grab her shoulders and shove her to the ground.

“Okay, well, give me your number,” she says.

I cock my brow. “Why?”

“So I can call you. So you can, you know, pay up. With interest. You owe me two-ten now.”

I glare at her. She reminds me of this bugeyed girl who used to sit in front of me in second grade. That bitch always pestered me with stupid questions. Do you have a crush on me? Do you wanna be my boyfriend? Can I have an Oreo? I’d sharpen my pencil extra sharp and poke her back with it. She’d tell on me, but I never gave a shit. “Don’t you have better things to do?”

She tosses her hair, ignoring my question. “Also, tell me where you live,” she says. “Just in case you block my number. And tell me your name. Wait, actually, just show me your ID; that’s easier.” She sticks out her palm and wiggles her chipped orange manicure at me.

I imagine poking a sharp pencil deep into her right eye and scooping out the eyeball in one gloopy pop.

She smacks her lips. “Suit yourself,” she says as she dials 911 and shows me the screen. Her finger hovers over the call button. My heart jerks. “Don’t!”

“ID.” Her free hand wiggles its wormy little fingers.

17

I roll my eyes, pull my ID out of my wallet, and slap it into her palm.

“Tom May,” she reads. “That’s a dumb name. Like Tommy but two words. Huh . . . 44 Spero Street. That’s kinda near where I live. Oh, I forgot to introduce myself. I’m Tiger Lily, nice to meet you.” She sticks her hand out. I snort. “That’s your real name?”

“Yeah. It’s cool, right?” “Whatever.”

“My parents are hippies,” she adds, as if that explains anything. She fingers the string of amber-colored beads around her neck.

“Okay, well, you owe me two-ten, Tom May,” she says. Then she turns and walks away. My skin feels itchy. I scratch my elbow, glancing around to see if anyone’s been watching. There’s a homeless man lying on the grass at the other side of the park, but besides that, it’s empty. I pick up my spade and try to dig out the buried bait cubes, but I can’t find them. I open the Tupperware box, dump out the last few, and head home.

A few hours later, as I’m eating pizza (cold, stale, and free; the perks of being a pizza delivery guy), the doorbell rings. I’m in the middle of watching a documentary about The Four Pests Campaign. Apparently, Mao the Dictator once ordered the entire population of China to kill all

18

the sparrows they could find. I’m so engrossed in the footage of Chinese peasants stringing up dead sparrows that I forget all about what happened at the park. So when I look through the peephole, I’m surprised to see Tiger Lily’s freckled face.

I swing the door open and squint at her. “What?”

“It’s the debt collector.” She slinks past me into my apartment.

I close the door and turn around. She’s walking around my living room, pursing her lips and examining my scratched-up leather recliner and coffee table like she’s at some kind of real estate show. On the TV, Chinese peasants wave flags in the air, banging drums and cheering as sparrows fall from the sky.

“Is this all the furniture you have?” she asks, raising her eyebrows.

My chest tightens uncomfortably at the pity in her voice, and I feel my ears get hot. I shrug and say, “Yeah. And a bed.”

“Where’s your bed?”

I point at a door to my left. “In there.”

Tiger Lily skips to the door, flings it open, and gropes for the light switch. She flicks it on.

Her mouth gapes open as she takes in the dog hides hanging from the walls. There’s the

19

dalmatian hanging front and center, flanked by several chocolate labs, golden retrievers, lots of poodles, some bulldogs and pugs. And, of course, a wall covered solely in Jack Russell terriers. It’s my masterpiece-in-progress, a mural of hatred I’ve been working on for over three years now, kidnapping and skinning them. It’s unofficially titled Man’s Worst Enemy.

“That’s a fucked-up patchwork puzzle you got here, Tom May,” she murmurs. She turns to me, eyes all glassy like she’s about to cry.

I look her in the eye and smile. Suddenly, she bursts out laughing, shrieking and clutching her elbows and gasping for breath. She’s cackling so hard she doubles over. It’s the ugliest laugh I’ve ever heard. My ears prickle. I cross my arms and stare at the dog hides on the wall, pretending she’s not there. I have no idea what to say. I expected her to cry and run away screaming, or at least get scared.

She takes deep breaths to calm down, stray giggles still escaping from her lips. “Sorry. Didn’t mean to make fun of you like that. It’s just, is that why you kill dogs? So you can hang them up on your wall?”

“Well, no.”

“Why, then?” Tiger Lily plops down on my bed. The black metal bed frame creaks. She gazes

20

up at me expectantly and pats the space beside her. “Sit.”

I scoff, but I sit down.

“Why do you kill dogs?” Her voice is suddenly very soft.

Something hot flares inside me. “I fucking hate dogs.”

“Why?”

“They’re fucked-up animals. They bite people and shit on the sidewalk. The world’s a better place without them.”

The bed creaks again. Tiger Lily is sprawled across my stained gray comforter like it’s the most natural thing in the world.

“They’re cute, though,” she says.

“No, they’re terrible.”

She stretches and her top lifts up, showing her smooth, pale stomach. The small knot of her belly button sticks out like a tiny tongue.

“Do you ever feel like you’re a big trash can, but no one ever puts any trash inside you?” she asks.

“What?”

“Like someone’s meant to fill you up, but they don’t, so you’re just empty?” She gives me a look, like I’m expected to kiss her or do something romantic. I’m suddenly very annoyed that she came in uninvited, acting like she knows me, trying to talk all deep and get in my head

21

like I’m not some criminal.

“Why are you here? You should leave,” I say.

“You let me in, though, didn’t you?”

“No, you barged in.”

“You opened the door for me, remember?”

“No I didn’t,” I say. Then I realize I’ve been caught, so I look at her sheepishly. Tiger Lily props herself up on her elbows and cocks her head to the side. Her orange hair spills down her shoulder, leaving her pale throat exposed. I’m suddenly tempted to bite her there, and I wonder if she’ll scream like she did in the park. She’d probably let me do it. She came into a serial dog killer’s apartment, after all, talking about trash cans needing to be filled and all that. I stretch myself out beside her. “You didn’t answer my question,” I say.

She turns to face me, but doesn’t move closer or further away. “What question?”

“Why are you here?”

“I don’t know, why are you letting me stay?’ Her eyes are a murky shade of green. “Tell me the real reason you kill dogs,” she says. “Why?”

“I just want to know.” Her eyes bore into me expectantly.

I press my lips together and look away. My eyes wander around the room and stop at the

22

wall of Jack Russell hides. I roll onto my back and stare at the ceiling.

“Well, dogs suck,” I say. “Why?”

“They bite people. Like I said.”

“Did you ever get bitten?”

“Yeah, when I was seven. I was at the park and this dog attacked me.”

She giggles. “So that’s why you kill dogs? You’re crazy.”

I scowl and my ears prickle again. But instead of turning away, I show her my right hand, moving it slowly so she can see the scars that cover it like small, shiny worms. “It bit my hand so many times I had to get stitches at the hospital.”

Funnily enough, I used to like dogs until one attacked me. I’d ask my dad for a puppy all the time, and each time he’d say Fuck no and smack me hard across the back of my head. I kept asking him anyway, because he was always smacking me across the head. But I never hated him for it. At least, not until that Christmas.

“And the dog just came out of nowhere?”

Tiger Lily asks.

“No, some girl commanded her dog to bite me. It was pretty fucked-up.”

That Christmas morning, I ran down the stairs. My dad had told me the night before

23

that he had a present for me: a real puppy. He said the surprise was going to be under the tree when I woke up, which ruined the surprise, but I was so excited I didn’t care. My dad and I never celebrated Christmas; that year was my first and last.

The tree was deformed, already shedding dry brown needles and smelling like sickly rotten pine, but I didn’t care. Underneath it was the precious present wrapped in newspaper. I tore it open. The box wasn’t moving, so I thought maybe the puppy was asleep. I opened the lid slowly, just in case I woke it up. It was an old Nike shoebox with brown stains all over the orange cardboard, and it smelled bad, like rotten meat and cabbages. When I opened it, I screamed. There was a puppy in there, but it was dead; a little curled-up thing the size of a hamburger bun. Its grayish eyelids were bloated, its slick fur rotting and crawling with maggots. I dropped the box, still screaming. The dead puppy flopped out onto the carpet.

My dad heard me and came thundering down the stairs in his stained boxers and smelly t-shirt. He took one look at me and burst out laughing. He slapped his hairy thighs and bellowed, Oh, you stupid son of a bitch! and slapped me across the back of my head. I ran out of the house in my pajamas. There

24

was melted snow on the ground but I didn’t care—I ran barefoot all the way to the park, because I had nowhere else to go. I thought I might find something fun to do, like pull some snobby boy’s pants down, but the park was empty because it was Christmas morning and all the kids were at home.

The girl came out of the playhouse behind the slide. She looked like a kindergartener, too young to be outside alone, but her parents weren’t with her. I still remember how ridiculous she looked. She wore an ugly potato sack dress and an extra-large aviator jacket that went down to her ankles, her arms lost in the thick brown leather. An orange beanie swallowed her entire head.

“Why’d she command her dog to bite you?” “Because she was fucking psycho.”

She had a puppy on a leash. Well, it wasn’t really a puppy, it was a really old dog, gray hairs growing from its brown and black markings. Anyway, I was jealous that she had a dog, and I asked her if I could pet it. The girl squeaked, No! while chewing on a Snickers bar. I was in a nasty mood, so I snatched the Snickers and ate it right in front of her face, strings of caramel dribbling down my chin. I expected her to burst into tears, but the girl stood very still and watched me do it. Then she screamed, and the ear-splitting note

25

rang out like an overboiling kettle. The dog began growling. She pointed at me, and the dog lunged, snarling and gurgling saliva as it snapped at my fingers.

Tiger Lily looks at me strangely. “What breed was it?”

“A Jack Russell.”

She claps her hand to her mouth.

“What?” I ask.

“Nothing,” she says, but she looks giddy, like a laugh’s about to bubble its way up her throat any second.

My ears grow hot and I want to yell, You think that’s funny? But I just glare at the wall. I’ve never told anyone that story, not even that boiled-down version I just told her. Heat spreads across my cheeks and I have to vividly imagine throttling her to cool down.

“When did you start killing dogs?” she asks. I look at the stray mutt hide pinned at the top left corner of the wall. It was the very first dog I skinned. I kidnapped it from the sidewalk and brought it to my kitchen. “I don’t know. Like three years ago.” When I moved out of my dad’s shithole.

“And you kill dogs because all those years ago, that one Jack Rusell bit your hand?”

“Well, yeah.” “That really sucks, Tom May.”

26

I turn to glare at her, expecting a mocking smirk on her face, but she seems sincere and, if anything, kind of melancholy. She scoots closer and drapes her arm across my shoulders. Her skin smells like cinnamon.

“Uh, it’s whatever,” I mumble.

She’s so close I can see the pale roots of her eyelashes, a blank space hovering between her thick eyeliner and heavy mascara. Like she’s about to whisper a secret, she leans in and kisses me, her lips soft like marshmallows.

I grip the back of her head and pull her closer. When I flip her onto her back, she makes a sound like a cat meowing and yowling at the same time. Then she does something to my ear that makes me groan. She wriggles out of her clothes, and I take mine off too.

She doesn’t speak again until we’re finished. As I’m buttoning my jeans, she rolls onto her side and asks, “Do you remember what she looked like?”

She’s fully exposed, her skin covered in a sheen of sweat. I’m tempted to throw a blanket over her, but she doesn’t seem to mind being so naked.

“Who?” I ask as I put my t-shirt on. “You know, that girl who told the Jack Russell to attack you. Do you remember anything about her?”

27

I shake my head, just wanting her to shut up and leave.

“Oh.” She chews her thumbnail, brows furrowed. “Really? Nothing?”

“Nope,” I say, popping the p at the end.

She cocks her head to the side. “Do you ever feel like a lost postcard? Like someone signed ‘Greetings from Paris’ on you, but they wanted to be mysterious so they didn’t write a return address, but your address got smudged in the rain so the post office doesn’t know what to do with you?”

“What?” I yawn.

“I mean, like you’re a lost memory that can’t be found?” She has that look in her eyes again, the puppy-dog eyes, and it makes me not want to look at her.

“It’s kind of late. Shouldn’t you go?” I scratch the back of my neck.

“Yeah, it is late.” She doesn’t budge. “Can you leave?”

She gets up and stretches, standing on her tiptoes and spreading her fingers. For a second, she just stays frozen like that, her pale and naked body reminding me of a tree in the snow. Then she puts on her clothes.

Before she leaves, she walks to the wall of Jack Russell hides and strokes one of them. She turns to me, inhaling sharply as if she’s about to

28

say something, but just starts humming a song that sounds vaguely familiar. Her long orange skirt swishes as she walks to the door and each brown polka dot on the fabric looks at me like a million eyes.

Tiger Lily stops beneath the door frame. She glances over her shoulder and says, “You owe me two-twenty now.” Then she turns and walks away.

29

In The Red Parlor

by Anna Carson Illustration by Katherine Fitzhugh

Margaret Caraway will die today.

***

It will begin in her parlor: a grandiose room, flush with burgundy curtains and lush carpet and gold trimmings. She will have a glass of maple whiskey in one wizened hand—the decanter sits on the antique end table and the amber light of the lamp makes the glass glow. She will be sitting on an extravagantly upholstered chaise, the cushions a deep carmine, and the velvety cloth of them will graze Margaret’s arm like a stranger’s skin.

The chaise was a gift from Edwin, who had given it to her to celebrate her new home. “How far you’ve come, Margaret,” he had crooned, more to the manor than to her. His hawkish face was upturned toward the manor’s turrets and soaring stone arches, and he basked

31

in its extravagance like a cat in the sun. She threw him one of her film smiles, the kind that had made her famous, and did not reply. In truth, she had never loved the chaise. She regarded it the same way she did her great stone manor: lonely in the countryside, picturesquely wealthy, and yet empty except for her.

Of course, she had taken great pains to make the manor a bleak place for herself. Perhaps she sought a reminder of where she had come from—or perhaps she wanted to see the price of how far she had come every day.

Edwin hated it. He despised the chilly white with which she had draped most of the manor’s interior. He claimed her slick metal fixtures and frosty upholstery kept her house from being a home, that he didn’t think Margaret could ever settle down here, that he could never come to love it. More than anything, though, Edwin hated the icy tiles that Margaret used in almost every room of the manor, except for this one parlor.

“It’s freezing in this house, Margaret. Why can’t you at least lay down some rugs?” She refused and offered him a glass of her maple whiskey to warm him instead. He acquiesced, but Margaret knew it would last only until he returned and walked with bare feet around her home, her bedroom. Fortunately, it has been

32

a long time since Margaret paid serious mind to his complaints. Too late, perhaps, had she realized that listening to Edwin speak was the same as running her fingers willingly through a patch of stinging nettle. He loved nothing more than to fling venomous words around to then settle, thick and heavy, in the throats of his girls. Once, Margaret had been one such girl; the first, in fact. But she is not so weak anymore.

She sips her maple whiskey. She savors the sweet burn of it down her throat. It coats her stomach and like coals it sits inside of her, a comforting, nauseatingly insistent warmth. Margaret hates alcohol because of the way she loves its burn, and hates the bottles of it on their oaken shelf in her parlor. She hates the way alcohol numbs even the worst of her pains. She hates it because it is Edwin’s, like so many things are.

She swirls the whiskey around in its glass and admires the way the honeyed light of it dances over the crystal. The glass, too, was a gift from Edwin. It is one of her older possessions. He gave it to her after her first real role, when she was young and foolish and afraid of fame. He told her that whiskey would help with the stress. He told her that she would need something proper to drink it from.

Her first major role was the jilted mistress

33

of a murdered rich man. The film was a tacky noir—every shot was thick with sex and drugs and the gritty murder-romance that so many people seemed to crave at the time. How she hated that role. At the ripe age of eighteen, she spent hours in front of the camera in nothing more than lacy lingerie.

“It is art,” the director assured her. Even now she remembers the acerbic gleam of his eyes from behind the camera.

“I won’t let anything happen to you,” Edwin said to her each night, after the day’s filming concluded. He would wrap an arm around her shoulders and sit with her for hours as she wept for herself, afraid and ashamed and still unable to go back. She would never leave, and Edwin knew it. It was why, when she felt his easy grin in her hair, even as her tears soaked the collar of his silky shirt, she didn’t say anything. She only continued to cry, and cry, and cry.

It was when the director decided to remove her top that Edwin recommended the whiskey. “It’s necessary,” the director had said eagerly, hands already reaching toward her barelythere lace. She ran away. She could hear Edwin reassuring the director, calming him—I’ll talk to her, don’t worry—and she knew that she would go back to Edwin, because she always did. In that moment, when she ran to her dressing room

34

and hid behind the door to weep, she hated herself more than she had ever hated anyone.

“Drink this,” Edwin said to her, softly, gently, as though she was a pet in need of taming. “It will help.” She choked on that first sip, then coughed her way through its burn.

“It hurts,” she said. She drank more. Later, when the director asked her to remove her top, Edwin passed her another glass.

Margaret can’t even remember filming the rest of the movie. She can only recall the sour taste of that cheap whiskey.

***

She places her maple whiskey on the antique end table beside the decanter, and a creeping heat scalds her skin and flushes her cheeks. She raises her hand to her lips and attempts to smother a cough.

Margaret wipes her hand on her gown, and pretends not to see the stain that it leaves on the satin.

The gown is gorgeous. It is not from Edwin. It was something Margaret bought for herself the first time she won an award for a role she was truly proud of. The gown is creamy white and shell pink, a delicate silhouette of soft satin and graceful curves. When she wore it on the red carpet, the media called it her best look to date.

35

Her role for that film was a schoolteacher in wartime France. A bit cliché, of course, but the film was beautiful. Margaret earned several awards for her performance, but the only one that mattered was the Oscar—Edwin had been certain she wouldn’t win it.

“This role wasn’t made for you, Margaret,” he fumed after realizing she had taken the part. She had agreed to participate in the film without his knowledge—she had been personally approached with the script. By then, she was a well-known name in the industry—not as big as some others, certainly, but a recognizable face. Edwin had usually had a stranglehold over her career. The teacher role was one he never would have wanted for her. But he was busy growing his agency—he had used her to create a business, and that meant there were other girls to teach, other girls to manage and shape and control. With every addition to his agency, Margaret slid away from him like a fish slithering off the bloody hook.

She would go back to him, of course. She would return again and again to sit at the end of his stabbing finger as he screamed at her for running away, for not listening to him, for taking roles she had no right to.

“I made you, Margaret Caraway,” he would snarl, his thin face pulsing red with fury. And

36

she would agree, like always, until it was time to run away once more.

Although Margaret has lost her youthful beauty, her gown has lost none of its timeless elegance. She had it tailored the week before to better fit her older stature. The tailor had been confused—the gown was out of style, after all, and Margaret was hardly known for going out these days. But none of that mattered.

As Margaret’s cheek comes to rest on her shoulder, she is glad she is wearing her beautiful gown, the most personal and private of her possessions only because Edwin had nothing to do with it. ***

Edwin found her when she was fifteen. Though she remembers precious little of her career—because of him, because of the whiskey, because of fear—she remembers with strident clarity the day he found her sitting outside of her house, head between her knees, cheeks tearstained and skeletal fists clenched against herself. She was curled up to hide from the rain. He wasn’t tall; he was much like a needle, thin and sharp and exacting. He approached her and held a great red umbrella over her head.

“My name is Edwin Clarke,” he said with a rakish smile. “And I think you will be a star.” It began like this.

37

Edwin, like Margaret, came from nothing.

She knew it because of the way he latched onto her. He gripped her small wrists as though they were lifelines. She could see it in the vigor with which he marketed her—she was his ticket out. From where she never did learn, but in his bright eyes she saw the same hatred she felt in herself every day:a hatred not for the world, but for who they had once been. A shame that crawled relentlessly beneath the skin, bone-deep and oppressive.

Edwin knew what Margaret was running away from. She would slip away from home to learn acting from him. He would style her mousy curls and tell her how to put on makeup and which clothes to wear. He told her what to expect from auditions. He said her beauty was her greatest weapon, but she could use it only if she gave herself completely to him.

Margaret was rejected from her first three auditions because they did not like the look of the bruises on her arms, the ones that couldn’t be hidden with makeup and flashy dresses. Edwin snarled, first at them, then at her.

“Leave them,” he finally said to her. “Leave them, or leave me. If you go back to that house every night, you are not giving yourself to me completely.”

She nodded. Just like that, it was done.

38

She lived with him for two years. She remembers sitting in the tiny office he was renting—soon, Margaret, soon we’ll have a building of our own. He would not have faith in her, but he would have the utmost faith in himself. He would take his whiskey and drink himself through the night, working, always working. He found her countless more auditions—small roles and minor modeling gigs. He advertised her round, youthful face and her sweet skin and her tiny waist. The arid taste of that office’s lifeless air still lingers on her tongue. She would sit in there for hours as Edwin dolled her up for the next audition. She can still feel the cake of cheap foundation and too-thick lipstick. Edwin had always known how to make something worthless look expensive.

Margaret still remembers the way Edwin had grinned when that director snatched her small wrist in his wolfish hands and offered her a role in a real movie. It was the break he needed. He pushed a bottle of whiskey into her hand and dragged her, limp and uncomprehending, into worldwide fame. He made her.

Margaret knew that she would be nothing without Edwin. She would still be in that house, with those people. She would have a black eye and bruises and she would hate her life, but she thinks she would hate herself most of all, for

39

being unable to leave.

She and Edwin were one and the same, in that way. ***

In her final moments, Margaret sees Edwin enter her bloody parlor, the only room in her cold house with carpet and color and a red velvet chaise. She can’t quite lift her head to look at him. Instead, her eyes follow his feet as he approaches, slowly, methodically. He kneels before her and gently pushes a curl behind her ear.

“Look how far we’ve come, Margaret,” he sighs. She sees the brushes of silver at his once golden temples. Wrinkles touch the corners of his summer-sky eyes. His skin has been beaten soft in the same way hers has—age has touched them both. He looks expensive, though— perfectly groomed, easy in his confidence, his solemnity. He is wearing a relaxed suit of fine black silk, smooth against her skin when he leans forward to look into her eyes. She sees in his gaze darkness and sadness and the resignation of a man who has a choice but is willingly choosing the wrong one. He does not need to do this, but Margaret knows why he is. She has become a liability, and this is what Edwin does with liabilities. He removes them.

He pulls on a pair of black gloves, plucks the

40

whiskey glass from her weak fingers, and places it in a black bag.

She says nothing; she can’t speak. She can only watch as Edwin takes a cloth and wipes her lips with tender care. She can’t feel her fingers, or her feet, and her skin is as cold as the tiles on her manor floors. Her lips are waxy gray—she would wet them if she could, but her tongue is a weight in her searing mouth.

“You’ve given me so much,” Edwin murmurs. He sits back and looks up at her. His gloved hands rest on his knees. “Thank you, Margaret.”

He stands and grabs his black bag. He is gone in less than a moment. This is why he does not see Margaret drift off, silently, peacefully, face devoid of the sharp lines of regret or anger that he was so sure would be there. She had accepted this fate, after all. Her life had been a long one, but it had never truly been hers. It brings her joy now, to imagine the disappointment on Edwin’s face when he learns that he did not win, not this time. Margaret smiles at the camera, painstakingly hidden in the creamy folds of the ornate lampshade. The decanter glows still, illuminated by its warm light. Her eyes fall closed. Goodbye, Edwin.

41

Roadkill

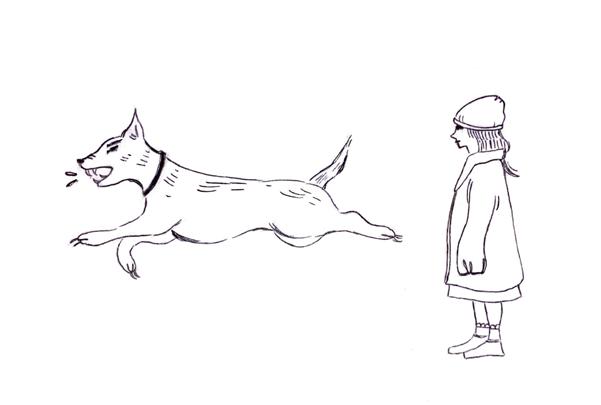

by Margo Heller Illustration by Hannah Meyers

The grass was fading to a heartless cold brown, like a memory being buried beneath years of weary time. The once warm and sticky breath of summer had been traded for chilly, stale whispers. Bears had started excavating dirt below fallen trees to make their cozy dens, and squirrels had begun to tuck away their last helpings of food before their long winter sleep. It was October in Copper Creek. Every Friday, Craig Lowrey got off work early. He was a mechanic and worked long shifts beneath cars, drenched in oil and sweat. Though stocky and strong, he was getting older these days. His beard was thinning and his wrinkles sunk like anchors into his skin. No matter how hard he scrubbed, the black line of grease under his fingernails never left, so at some point he stopped trying to eliminate the evidence of his tiresome blue-collar work.

43

On his way home, he stopped at Bobby Wright’s convenience store—as was part of his routine—for weekend necessities: eggs, milk, bread, and probably a pack of cigarettes he didn’t have the budget for. Scratch that. Definitely a pack of cigarettes he didn’t have the budget for. Enjoying the familiar atmosphere of the store, he ambled comfortably around the aisles before making his way to the only register in the store.

“How ya been, Bobby?” he said in a gruff greeting as he laid everything on the dilapidated counter. The laminate was peeling and browned after years of neglect, which was present in all things around town. Craig thought that the scratch-offs hanging on the wall behind Bobby, displayed in an array of now faded colors, were looking awfully lonely, like strays with wide eyes in an animal shelter hoping to be taken home.

“Been alright. Long week,” said Bobby. He did not have a scanner to check all of the items like they did in other places in Copper Creek. Instead, he added up the prices on a calculator; he knew them as well as his own name after owning the convenience store for as long as he did.

Craig hummed in agreement. “‘Least it’s the weekend. Got time to unwind.”

“Got that right,” said Bobby. He stated the total, to which Craig poked through the bills in

44

his worn wallet and fished one out.

Bobby Wright was about a decade older than Craig, but the visible difference in their ages closed as time passed. Bobby was rather thin from age and kept his face clean-shaven. A black and beige fishing cap, permanently stained with dirt and grime on the brim, was always placed upon his crown, and he spoke slowly, with wise deliberation that stood before every word. Old country tunes weaved throughout the store to drown out the static of isolation. The yearning voices sang about forgotten towns and hard, honest work; they crackled in the speakers as the wind pushed the satellite located somewhere atop the building.

“And how are you, young lady?” Craig asked the youngster perched on a stool behind the counter.

“I’m alright, Mr. Craig,” she said, glancing up for only a moment. It was Violet; she was Bobby’s niece who frequented the store in her boredom. She doodled on a yellow-lined notepad as she spoke. “Been so much roadkill lately though. Makes me sad.”

“Well, it’s breedin’ season,” replied Craig as he tucked his change into the pocket of his jeans. “You can only expect that they’re out more.” Her pen drew slow, precarious strokes down the pad. Two blonde braids draped over

45

her shoulders to the top of her camisole, and tied to the ends were thin pink ribbons in bows. “Which is exactly why people should be more careful when driving,” she muttered.

Craig hesitated. He looked to Bobby, who was not particularly interested in the conversation. He was straightening up the counter, marking the sale in his books. He did not seem to have processed anything outside of the transaction.

“They’re just deer, sweetheart,” Craig asserted. “If anything, it helps keep the population in check.”

The fluid movement of her pen stopped. Her eyes flicked up before her head turned to follow. Strands of gold fell wild around her cheeks, and bright brown eyes squinted in confusion.

“Do you believe in karma, Mr. Craig?”

A breath of a pause lingered after the word “karma,” as if she was letting it sit in the air with an accusatory purpose. Her small, soft-spoken voice drawled with the West Virginian accent she’d surely picked up from her uncle. Craig was about to turn and be on his way, but he stopped on his heels.

His jaw clenched. “I do.”

Violet didn’t say another word. Instead, a barely noticeable pout showed upon her mouth as she nodded, before she returned to

46

her notepad. Craig’s lips pursed and the urge to correct the girl came up his throat as cruel and sour as bile. Her words bounced off each internal wall of his head, exponentially raising his temperature. He felt disrespected by her question. It was rude. It was bad behavior. And he would have thought Bobby Wright would pay a little more attention to his niece, try to instill some good values in her—but he didn’t say a word either.

Something inside him was bubbling up and making him want to stick around and argue, but he made the rare decision against it. Besides, he couldn’t lose one of the only places he was still allowed to step foot into.

He turned around and left, boots clomping over the old cracked tile, receding into his selfaffirming seclusion.

From the window, Violet watched him get into his rust-red pickup truck. She noticed the multitude of dents in the front of the metal, the strangled grate that resembled a cold set of teeth. Then he pulled out and left, throwing the gravel up in a cloud of dust as he drove out of sight.

Craig was no stranger to this practice of leaving when things got too overwhelming. As the town crawled with gentrification and a sickening growth of tourism, the bitterness that consumed him outside of his home was

47

sometimes overbearing. He simply had to remove himself from their ogling eyes. Bobby Wright’s was one of the only places left he could go to in comfort. Just outside the heart of Copper Creek, the property hadn’t yet caught the eyes of greedy real estate agents. As of now, it was too worn down; the investment in fixing it up couldn’t make a profit. So it continued to belong to the locals. In ten years' time? Who knows.

That was the trend. Visitors became residents, and old local businesses closed. He watched his neighbors' livelihoods turn into exposed brick coffee shops that were far too expensive for the old clientele to regularly afford. Not to mention the stupidity they felt when ordering alone. No one could just get a cup of coffee anymore. The simplicity that comforted him as a boy had died.

Craig watched it all, hated it all, and went back to his solitary home to find a way to cope. Tonight, that would mean cracking open a cold one while driving. He bit the beer cap off with gritted teeth and spat it out the window, where it bounced onto the pavement behind him. Crisp air poured into the vehicle as he took a generous swig that rewarded him with temporary relief. Not every coping mechanism was a healthy one.

48

The evening fell over the sky like a mother laying a blanket over her sleeping child. The space between the trees darkened to a navy sea, and the streetlights awoke to dully illuminate the streets below.

The roads, long stretches that slowly transformed from smooth pavement to battered asphalt, were mostly empty. A few cars passed by every so often. The drive home was a long one, as his residence lay far from the heart of town.

Ahead, Craig spotted a small gleam hovering in the black void of night. His body tensed in excitement as he lowered his foot to the gas. When his headlights shined upon it, the gleam revealed a petite doe with hooves frozen to the double yellow line. Her white tail was stuck in the air with not even a swish, as if it was held up by a puppeteer. She did not even blink at the oncoming vehicle.

Craig tightened his grip on the wheel. When he came into range, he tugged just a bit to the left and swerved. The impact was staggering. Though he was sheltered from the chilling noise of his actions inside the car, bones shattered like porcelain as the doe was thrown back, down, and subsequently crushed by the weight of his pickup. He only felt two thumps as she passed under his car.

He sighed. Craig Lowery lifted the bottle

49

from the center console and drank again. He drove away, leaving behind a deer that was no longer what a deer should be. She bled and cried while her body lay mangled, unmoving in the dark. In the morning, black vultures would tear her apart and return her to what she used to be. With her neck sprawled meaninglessly, she died without seeing a star in the sky.

After hosing down the front grate of his vehicle, Craig was finally able to pull his front door open and set his groceries on the counter. His home was small and messy, with stained blankets strewn over the floor and old, crushed beer cans making a comfortable refuge in each dusty corner. The rugs were angled out of place, the dishes were piled up in the sink, and ants crawled over the counter carrying remnant crumbs to their friends. Dim yellow lights buzzed above his head and provided a grave glow to his hermit’s abode.

While his house was firmly lived in, it looked as though no one had stepped foot inside for years.

He breathed in a sour stench and immediately recoiled. Across the room, the refrigerator was open, spilling warm light onto the tile of the kitchen floor. He covered his nose as he inspected. From just looking into the fridge, everything seemed fine. He had to let

50

go of his nostrils and use his smell to find the source. He moved around jars of jam and pickles, shuffled through the stacks of beer, and clinked through glasses of various dressings and sauces. The culprit lay on the bottom shelf.

It was a container full of roasted chicken that had begun to rot, the only perishable item of food he had. Ants swarmed the package, and the odor was absolutely acrid in his nose. The meat had started decaying. It was a shame—he thought it would be fine for another few days, but perhaps the time had passed quicker than he realized. He was hoping to eat it for lunch tomorrow. Too late.

Craig gathered the strength to grab a corner of the package through the ants. As his hand became a makeshift bridge, he felt tiny, scurrying legs float across the skin of his fingers. Ants fell off mid-air, trying to chain back up to his hand as he carried the chicken across the room to the trash can. The meat fell in with a thump, and because the garbage was much fuller than it should have been, bits of the flesh fell out and rolled onto the tile. Craig cursed to himself, but his frustration was met with empty, apathetic walls that could not even offer an echo. He tied up the trash bag, sealing away the meat and ants, and brought it to the can outside. After that debilitating debacle, he sank into the

51

worn cushions of his couch and took another sip of his beer. If one were to look around the place and consider the mess, it would be hard to tell if anything had changed—to any person to whom the mess did not belong, at least. Mess is familiar to those who make it.

So when Craig noticed a hardcover book on his coffee table was open, he became suspicious. Craig hadn’t read in years. The books were purely decorative, though at this point they just cluttered the space. Still, he didn’t recall reading it recently. He reached out and closed the book, sending a cloud of dust into the air.

He shook it off. Instead, he dug into the couch cushion to his right to find the remote. Maybe he’d take a peek at the news, but he’d probably watch whatever sports game his cable could provide.

But then something else caught his eye. The taxidermied buck’s head that hung above his door was crooked. The emblem-shaped plaque was tilted to the right, as if someone had jumped up into it on the way out and knocked it with their head. And the eyes—sickeningly deep abysses. Though they had never impacted Craig in the past, tonight he felt unsettled looking at them. He wondered if there was someone behind the face, using it as a mask to watch him. He tried to pay attention to his show, to the

52

voices chirping with slight static, but the chills kept coming down his back. He had to get up. He stood, plucked his keys from the bowl on his counter, and went back out the door, leaving behind the home that mirrored his murky insides.

It was not uncommon for Craig to end up at the bar. Tonight he went to The Brick, the one establishment that had not yet banned him from its premises. To Craig, it was because all of the new upscale, fancy bars were trying to push out the locals. Not any other reason that might result in someone getting banned from a bar. That’s how he rationalized it, anyway.

He treated himself to a hefty glass of Guinness. Amidst the conversations with the regulars—John, Charlie, and Old Man Gregory—he was having a relatively good night. They talked about when they were young men, swapping stories of fun mischief and brilliant invention and the occasional minor act of arson. Craig laughed with them, and his eyes crinkled at the memories of a town he once knew. But nothing good can ever last. His story of him and his friends venturing along the creek beds in search of gold was interrupted by a boisterous racket. A group of young men dressed up in business attire sat at the end of the bar. They cheered loudly as they downed a round

53

shots, probably celebrating pressuring another local into selling their land so they could start building an apartment complex. Craig scoffed and brought his third beer to his mouth.

One man, a tall brunet with a manicured beard, must have noticed the icy looks being thrown his way. “Excuse me, is there a problem?” he asked.

Craig shrugged. “Not one that you’d be keen enough to see.” He licked the foam from his mustache.

The man’s friends began to tune into the conversation. They stopped their cheering and gathered around, which only propelled Craig further.

“Then please, enlighten me.”

Old Man Gregory disapproved of the escalation, muttering to Craig not to engage. But he was an arrogant man, and just couldn’t help himself. He set his glass down on the counter with a clink.

“The problem,” Craig cleared his throat, “is that people like you come to this town and push people out of their homes. And then you come into our bars and celebrate as if you’re heroes.”

The man laughed uncomfortably. “We’re just doing our jobs, man.”

“And taking away the jobs of the people who live here!” Craig stood to his feet so fast that he

54

knocked the stool to the ground. He got in the man’s face, and the more he looked, the angrier he became. The firm knot of his tie, his crisp white collar, the smell of top-shelf whiskey on his breath.

“Okay buddy, watch it. We’re not trying to start trouble.”

“You already have.”

Craig felt the hot blood pulsing through his veins, and before he knew it, he was swinging a firm fist toward the man’s cheek. Seeing him fall back as he spit out blood rewarded Craig with rushing adrenaline. Shouts erupted from all over the bar, a cacophony of shattering glasses and clattering stools that raised the stakes even more.

The toothy smile that filled his mouth lasted for only a moment before a friend of the man retaliated. In an instant he was stumbling back, being carried away by someone he didn’t have the strength to fight back.

That night, Craig Lowrey was banned from the last bar he was allowed into.

“Don’t come back,” said the bartender from the door. He slammed it closed behind him, sealing Craig in the dirty parking lot.

He dragged his knees up below him and groaned as he pulled himself to his feet. He cracked his back, cracked his neck, and brushed the dust and dirt off of his faded jeans. Ever

55

since The Brick started welcoming in big shots like that, it was on a downward spiral. It was only a matter of time before it was no different from any other bar in town, and Craig concluded that the time had simply come.

He shook it off. Even though he came to the bar to get away from his home, he could still go back and drink there, too. Besides, he didn’t want to be around those people for a second longer anyway—they were all too sensitive. What man can’t take a punch?

Stumbling to his car, Craig thought of Violet at the convenience store. Those types of kids grew up to be the adults he just encountered. Couldn’t take accountability, and couldn’t mind their own business. It was just a shame. He threw himself into his car and located the beer from earlier in the cup holder. It was unpleasantly warm sliding down his throat, but he sighed as if it was morphine for a badly injured soldier with a dismal future.

He put the key into the ignition, felt the familiar rumble of the engine ignite the beating of his heart, and drove home.

The roads were blurry, courtesy of his intoxication, but Craig had done this plenty of times. His muscle memory never failed him on late nights like this. The grip and sway of his knuckles on the wheel directed him to the back

56

roads without hesitance.

It was quiet for a while. There was a lot to think about at times like this. When he passed through these roads, he couldn’t be sure if what he was feeling was fondness for his hometown or regret for never leaving. The forest, which stretched on for miles in the surrounding directions, was more of a prison than any sort of luxurious woodsy getaway, as new rentals in the area liked to advertise. Deep green leaves shrouded light in the canopy, and thick logs of wise oak stood as guards on the forest floor, sealing away Copper Creek with the same old, stale air to collect and fester with no room to escape.

Though his movements were on autopilot, his eyes were trained to search for the innocent glimmer so dear to his soul. Craig was like a hawk scouring for prey as his gaze scanned the abysmal blackness of the forest. One would come soon, and he would be ready.

It felt like only minutes before he spotted a small, pointed glare in the distance. It was a glowing orb in the dark of night floating above the road; he could not yet see it. His heart skipped a beat.

The rusted front of his pickup truck hungrily consumed the asphalt. He veered out into the middle of the road, lining up the right corner of

57

his truck with it. Feeling the preparatory surge of adrenaline, the rush of blood through his pulsing veins, and the pounding of his heart in his ears, Craig closed in on the figure. The space surrounding the glare came quickly into the crosshairs of his headlights, filled with big eyes and soft brown fur and a frozen white tuft of a tail. She stood there, waiting. There was a dull thump as he smashed into her, and his body rocked violently as the wheels passed over her. The pure, rushing euphoria brought a convoluted smile to his weary face. But his unadulterated joy was quickly interrupted by a curtain of tiny lights falling over his sight. At first, he thought it must be a swarm of fireflies blanketing his windshield. He then realized, to his pure delight, that it was even more beautiful: encapsulating gazes waiting for him. It was a mob of his favorite thing in the world. Tens of glares—no, hundreds of glares— quickly approached. He checked the rearview mirror only to see more glares. They were up top in the hills and to the side on the tree line. They were far behind and close in front. But something about these lights was different. These were not bright, swimming with the innocence of mother earth. These were cold, he thought with displeasure, almost aggrieved. His crosshairs were no match moving in on the

58

crowd, but he couldn’t stop the momentum of the vehicle even now. They were too close. Ahead of him, mounds of brown fur belonging to glowing eyes stood there, waiting. It was a sea of his dreams coming to punish him.

He stomped on the break as he crashed into the crowd. Glass burst, metal bent, and a roaring screech of scrapes echoed in his ears. Craig felt weightless as he flew.

When he found the consciousness to blink open an eye, he realized couldn’t move. His cheek and nose were hot and pressed rigidly against the crumbly asphalt. From the one eye that he could barely see out of, he made out his truck deep in the forest, smoking up into the night air. It was completely deformed— lost wheels and shards of metal littered the surrounding shrubbery, and the only reason he could tell it was his vehicle was because of the flames licking up from beneath the hood.

He tried to move his fingers or his toes, but he couldn’t feel anything except the tremendous pounding heat inside his skull. Something skincolored outstretched his view, but his dazed mind could not yet process the meaty, crimson explosion next to his body which spilled out onto the road. He heard the muffled sound of his panicked breathing as it occurred to him that he could not feel his fingers because his arm ended

59

at the elbow.

It appeared as if he was utterly smeared across the road.

Craig’s insides burned as he felt bile rise in his throat, and he didn’t even want to look at the rest of his butchered body. It was as if he was floating atop a puddle of burning oil.

And the glowering eyes, all around, began to close in. He was glued to the ground, waiting. Wet noses, tufts of white, and heavy, huffing growls of angry generations offended by his sins were finally ready.

His curses surrounded him. In the morning, he would be no more than a red mess of flesh and bone, left for the vultures to devour. Violet would drive by with her Uncle Bobby and make a saddened comment, not knowing that she would never again see another corpse along these roads.

Gentle moonlight coruscated over his humbled body. His breath escaped his throat as if pulled out by the passing wind, escaping through the breaks in the trees to the atmosphere far above.

Craig felt a wet sting in his eyes as he looked back at a buck who had lowered his head right in front of him. One rounded diamond ear, full of creamy, light fluff, extended just over his mouth. The sharp tip of his antler poked into Craig’s

60

cheek, and he let out a pained, strangled cry. He could not even see a star in the sky.

61

horror story (true story)

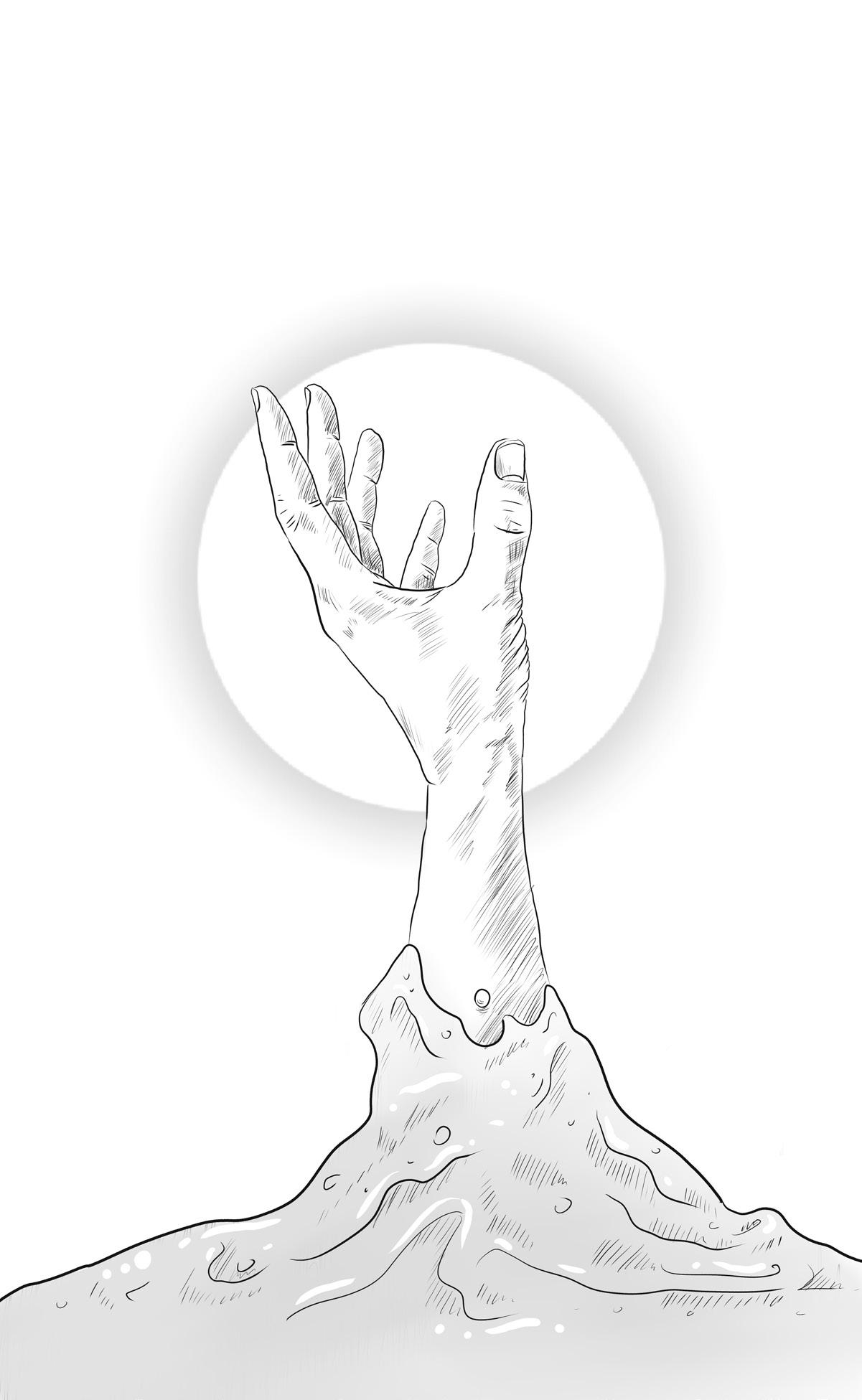

by Marin / Spencer Madden Illustration by Katherine Fitzhugh

You grow up on a planet far away from here. The air is always cold, and it is always snowing and raining. Flowers bloom and die constantly; the trees sweep you up in their branches and cradle you. The stars tell you stories that you still remember for their bittersweet endings. When you’re twelve, the aliens come. They tell you stories too, stories about people who fall in love and get married and have babies; the idea sounds lovely to you. They say you can have it— you can join them—all you need to do is press a big, red button in a temple far away. You agree. You want to feel so safe and loved and happy as those holograms they showed you seem. So you take your books and your sword

63

and your cloak, and you go with them to their planet. You head up the mountain, the button so small you cannot see it.

At thirteen, you find a village of new books. They let you read them, these new stories, but they start to make you uncomfortable, rather than happy, speaking of bodies that look like yours writhing together on a bed. You struggle to picture it, and when you finally do it makes you feel itchy all over, like a virus has infected you. You leave and you try to forget the new stories, reading the old ones you know over and over again, and people call you a child for it. You feel the insult sting, but you rebuild it into a shield and hope it sticks.

At fourteen, you find a bunch of caves. They look like the rabbit holes of your home planet, so you trust them and you fall down freely, landing in sticky goo. You pull yourself free and try to escape, but every cave you enter ends in stickiness. Your books end up trapped in one of these lakes, sinking and sinking even as you try desperately to pull them free and wrap them in yourself; soon you have to leave them behind. You cry the whole way up to the surface, and the rabbits are there waiting for you. They offer you soft books to cradle instead, but when you touch them the books bite you, trying to get through your ribs to your heart, so you drop them and

64

you run and you run and you run.

At fifteen, you find a glittering waterfall. It sings and sings and sings, and you fall asleep every night singing along with it. You miss your books, but you learn to cope with it. You cut down trees and leaves and you carve new stories into them, ones that you make up yourself, and because they’re yours you know they’re safe. No one comes for months and you feel safe here, all alone, without anyone to stare at you or touch you. You start to forget about the red button, and it becomes smaller and smaller. It has almost disappeared when the waterfall starts screeching—these horrible lyrics that evoke such horrid visions, these things you can’t get rid of— and where the water once cleansed you it now traps you, and you see it turning green like the goo that once buried you alive. You cut yourself out of it with your sword, but it sticks to you still, and you can’t slice it all off no matter how hard you try, instead leaving wounds all over yourself for the goo to slip into. You feel dirty and sick and scared everywhere.

At sixteen, the dream you once had starts to feel like a nightmare. Love feels like the waterfall, all sweet and soft and unassuming, but whenever you step foot in its currents, it sweeps you up into something you can’t control. It holds you there as you scream and scream and scream,

65

the green goo coming for you. Marriage becomes an inescapable jail sentence, something that will trap you and keep you from your precious stories, and you stop dreaming of white dresses and start thinking about pajamas. Babies are an evil reckoning, an infestation of terror and pain and risk all tied up with a pretty little bow so everyone tells you they’re a gift, but you see them for what they are and you hate them, you hate them, you hate them. One day you dream of yourself with a growing stomach and a ring on your finger. You wake up in a cold sweat and build yourself a cottage in the dark, desperate for loneliness.

At seventeen, you lose your sword. All of your stories become about darkness and death, and you feel them creeping towards you all night. You build trenches and fences to keep the green goo out, and you board up your windows and you write your stories on the walls. You learn enough magic to get the food to your stove without ever having to leave, and you keep the door locked. One day, an alien stops by. They keep you company, and they let you tell them their stories, and they smile at you. They’re kind, and they’re sweet, and they’re funny, and you think this may be love. With them in your life, love has become safe again; a sweet thing you can almost taste, and so—because you love

66

them—you let this alien tell you a story. It is horrific and horrible, and you cover your ears and you cry and you scream and you shove them out into the suffocating warmth, into the humidity that wets your skin without your permission, and you board up the door. There is green goo on the chair they left—a residue of their wants— and you burn it in the fireplace, and you build yourself a new chair. You realize you left your sword outside where the goo is always bubbling, and you wrap your cloak tighter around yourself, too terrified to move.

At eighteen, your house collapses. There are voices everywhere; all these aliens have come to make you push the red button, and they greet the goo like a treasured friend as they hack down your house with their careless words and invasive hands. You start to run, having lost all your stories and your safety, and you run and you run and you run until finally, you find a pyramid. It is covered in green goo, but you must get away from the aliens that are chasing you. So you climb and you climb and you climb, and your cloak gets stuck and stays stuck no matter how hard you pull, so you must leave it behind, too sweaty in the heat and blinded by the brightness. Finally you reach the top: a huge room with so much space you can run through it, with a tiny red button in the middle.

67

Every day the button grows. At first you can write your stories and paint your wishes and everything is fine, though you feel naked and vulnerable and on the brink of collapse. But soon the button is half the room, and then more, and then more, and then more and more and more, and soon all you have is a corner, your precious little corner, and you can no longer remember how it felt to have your books or your sword or your cloak because they have stripped you of everything, leaving you exposed and bare to do whatever they wish to. You say no and the button falls back, but the new books have been coming through the window, and they bite you with their facts, with the teeth that say no won’t be enough one day and that the green goo is a natural thing to want and that if a baby infects you, you will be forced to carry its sickness and die with it. And so, covered in bite marks and open wounds and green goo, you sit in the tiny corner left by the red button and you cry and you cry and you cry.

Press the button, the aliens chant, coming up the mountain. It’s only normal; press the button. It’s only natural; press the button. It’s only alien; press the button. You cannot breathe. You take your tears and your nakedness and your pain and you start towards the red button, even knowing that pressing it will kill you.

68

You don’t have to do this, says someone else. It’s okay. You’re not an alien. You’re not like them. It’s okay. You can love and marry and adopt children with one of us. It’s okay. You look up and through the door: it’s another You. He has soft dark hair that falls to his big shoulders that could keep you safe if he hugged you. He is standing in front of others: a man in a cloak and a girl with a sword and a person carrying books. He touches you gently and lets go as soon as you ask. He helps wash you of the green goo, and though your skin remains green where it was stuck before, you feel lighter, no longer like a body is pressing down on top of you like stone, keeping you from breathing. They flicker like phantoms, the yous. They don’t seem real, but you cling to them like lifelines as they take you away from the red button. They listen to your stories and they offer their own: they’re all full of wonder and happiness and safety. You walk with them up into the stars, across a bridge of black and gray and white and purple, and in your beating heart, you can feel your home coming closer. Then, one by one, the arrows come. They fall like shooting stars and they pierce the chests of all the yous that protect you, and one by one your shields fall. They are encased in coffins of

69

green goo, and you run for your life toward your home, toward your planet, toward the place you wish you’d never left. You stop dead cold when you reach it. It is covered in red buttons. Like floor tiles, you cannot take another step without pressing one. You fall to your knees, staring up at the aliens. They smile down at you, kind and cruel, and you weep. Please, you say. No. But they don’t care and they don’t listen, and they march you toward the red button, tugging your wrist out and shoving it forwards. You scream—a ferocious last resort—and you sink into the ground, buried in the cold, dark earth.

In your grave, you lie. You hear the aliens moving above you, looking for you. It is lonely here, and boring, but at least it’s safe. It’s predictable. You cry in the dark and you tell your stories, knowing that no one can hear them and no one can see you. You miss your friends and your family and the possibility of love, but you know now that no one wants your kind of love, your pure and clean drink of water. You stay in your grave and you drink alone.

When you fall asleep, you imagine the green goo dripping into your tomb. You wonder what ill they speak of you, the dead. Your name

70

means nothing, your love means nothing, your life means nothing. The aliens do not care about your traditions or your feelings or your oddities. Where you see special, they see a child. Where you see uniqueness, they see a liar. Where you see happiness, they see a freak.

You lie there, alone, in your grave. You can hear the other yous screaming, lured by promises of impossible dreams. You imagine a child you could’ve helped without birthing it, and you imagine a ring on your finger you were comfortable wearing, and you imagine a person who tells stories like yours that make you feel safe and loved and happy. You imagine these impossible things, and you think of the aliens; how they came and slaughtered you and your similars with their ignorant words and social conventions and inhumane laws. You imagine yourself like you were before they came, and you wish and hope and plead that other planets are saved from this ravaging.

Your tombstone crumbles. They shave off the word human even as you brave the green goo, crawling from your grave to shove their hands away. They smile at you—so helpful, so wellmeaning, so stupid—and they tie you naked to what they call the “Tree of Life.” You watch them write ALIEN on your tombstone—the last thing of yours that you had left—as the green

71

goo slithers towards you and encases your entire fucking body in itself. You hate it, and you hate them, and you love yourself.

You miss your shield of child. You dream of synonyms like asexual and normal. You die in that green goo, crying, asphyxiating in its grip. You die in that green goo, screaming, wondering how anyone could want its stickiness. You die in that green goo, pleading, starving for the aliens’ fucked-up blood.

You die young—when they decide—because they can’t understand a life like yours, and you know it. You hear their empty promises and you wonder if this starving well inside of you will ever be full enough of stories, knowing it needs love to be filled. You twist yourself and your dreams into something even you don’t recognize, but at least it will keep you from the green goo. It may be cold and dark and dead, but at least you won’t be touched. At least you won’t be an alien.

Please, a human asks the aliens. Let me go.

72

73

Repetitions

by Abbie Langmead Illustration by Hannah Meyers

The only way you can tell the time is by staring through the mirror. You look right above Isabel’s reflection at the end of the ballet barre so you don’t face the wrong way. The clock is only as consistent as when Mel changes the batteries. Unfortunately for all of you, Mel claims she is far too busy to get around to it. The clock reads 8:17, but that can’t be right. No, it’s been much longer than that. It all started back when you were four years old. That’s already much later than most start, but there would still be hope for you. There would still be hope for you. You had passion.Your parents took you to see The Nutcracker the winter before you started dancing, and you came away from it with a childhood fixation on Tchaikovsky and standing on your tiptoes.

Did you want all of this, even when it started so small? Maybe. At that age, none of you did

75

anything unless your parents wanted it a little, too. The day of your first dance class, you clung to your mother as you wore a pink tutu, itching at the sequins sewn onto the front. She tried to push you along, but you’ve always been stubborn. No, stubborn is too negative. You’re determined. You’re obligated. That’s what keeps you here.

When you were little, braver and luckier girls ran into this room, reaching up to the barres, planning to hang off them even though it wasn’t safe. Julia Wyndham stayed behind, coaxing you in. She showed you the pretty pictures of the big girls on the lobby walls. You both could be like that too, you just needed to try. You both were supposed to be like that.

Julia Wyndham left years ago, but it seems like you’ve never left this room, with this gray floor and these white walls. Back to the clock— no, scratch that. You’re starting.

Mel skips through songs on her phone, clapping out the rhythms until she realizes they don’t fit the exercise. A waltz, that won’t do. The slow movements of an adagio won’t work either. Skip again. A staccato piece in 4/4. She claps along to the time and you count in your head.

“What does pique mean?” She calls out to the class.

“To prick!” you all reply. She calls out, “One and two! Three and four!

76

Five, six, seven, eight. . .” demonstrating with her hands. You translate the combination into your footwork, setting it all in stone. Don’t just mark the movements like the others do. Prepare. Full out, every time. That’s what’s expected of you. “Good?” Mel asks the class. When nobody responds, she replies to herself: “Good.” Body check. Your chin is up, eyes ahead. Your shoulder blades press into each other, but your rib cage should stay closed. You go into prep, rounding out your arms at your side. Extend your knees. You push your feet into the ground, heels pushed into each other in first position.

You make space for all the scuffs on the floor, at the edges of your slippers. You could’ve made those marks yesterday, or years ago, or maybe not at all. You wouldn’t even know—your eyes should be up. Look up.

You’ve been in this same spot on the barre since you were twelve years old. You used to be in the corner next to Isabel and the clock, hiding all your flaws in the back of this classroom. Where you stand now was once Julia’s spot—her prized spot.

Everything changed when Mel started using you as an example more often. You got excited. You stayed late to watch the older dancers in their pointe shoes. You dreamed of their poses

77

and images, working to become them. You beamed every time Mel called your name, and she called your name more and more often. You slipped away from Isabel, past Kaitlyn and Lauren, and became too far away to talk to any of them. They were all at the same school and a year younger than you, anyway, so it wasn’t like you missed out on much. You had a job to do, being the best that you could be, and you did it. In time, you stood in the prized spot, the front corner right next to the speakers. You used to flinch when you felt the bass from the speakers creep through the air. Julia sneered as she stood right behind you. She’d swing her hip as hard as she could and kick you during her front grand battement. When you did the back side, you’d kick her too. It was an accident, at least for you. Now you don’t flinch—you use the synchronization between the music and your heartbeat to help you keep the rhythm. Now you don’t cause accidents.

At the time, you insisted that you deserved the spot more than Julia. You wouldn’t watch TV on the couch. You sprawled across the carpet and did your splits during ad breaks, like Mel recommended you all do. You took photos of yourself in every position and leap, searching for imperfections outside of classes. You applied every correction Mel gave you; her word was law.

78

You went to the prestigious summer intensives that Mel recommended. Your parents put their investments in, buying leotards and pointe shoes that go dead every two-and-a-half weeks. You make them proud, and that’s what matters.

Julia just didn’t work, or wouldn’t work, you told yourself. It was her fault you took her spot. She’d have to earn it back. You earned the top spot fair and square.

Now you’re sixteen, and you know you got lucky; you’re five-foot-five, light enough for a boy to toss around in a pas de deux. Of course, there aren’t any boys to toss you around in a pas de deux. Alex is the only boy your age at the studio, and he only takes jazz and tap. You two avoid each other in the hallways at school, both pretending you never see each other outside of the school walls. Mel says it doesn’t matter—the fact that somebody could partner with you is lucky enough.

It’s luck, that’s all this is. That’s what Mel says this whole world is. She reminds you at every class and every private, so much you could probably recite her whole lecture by heart. What got her the scholarship that brought her to a ballet conservatory at seventeen? Luck. What got her working in San Francisco before a knee injury cut her corps de ballet career short at twenty-five? Luck. How should you all feel to

79