THE WHITBY

Academic Journal

St Hilda’s College

The University of Melbourne Second Edition 2022

St Hilda’s College acknowledges the Wurundjeri people, Traditional Custodians of the Kulin nation, the land on which our college lies upon today, and pays respects to their Elders past present and emerging.

Editors Note

The Whitby is an annual accumulation of essays, research papers, poetry and art crafted by the talented members of our College. This year, as the pandemic settled and we found our new normal, the excitement of studying on campus was a new challenge for first, second and third year students alike. This year’s Whitby is a timestamp of the drive and inspiration that these unique circumstances brought us, as we more than ever appreciated the opportunity to collaborate and interact with our peers.

The Whitby was designed and edited by students, and all works are presented as they were submitted.

Bess Hamshaw Academic Convenor

Acknowledgements

Editor in Chief: Bess Hamshaw

Cover Art: Lucca Harvey

We wish to acknowledge and thank the talented contributors of this journal:

Isabelle Auld

Imogen Quilty

Lucca Harvey

Zodie Bolic

Hannah Lilford

Ally Hardy

Georgie Macho

Hanah Denison

Finlay Etkins

Anoushka John

Money can’t buy happiness, but it can buy healthiness

Imogen Quilty

Essay examining a fictional ‘Agouti’ virus and uses it as a lens to look at how low socioeconomic status is impacted by and perpetuates disease, medicinally, ecologically, psychologically, and geographically.

Despite rapid social development in the 20th century, poverty and its burden of disease still play a prominent part in today’s world, continuing to threaten the poor and vulnerable. The recent Agouti virus outbreak can be classed as a pandemic. Its wide geographic expansion from East Asia to South America and Australia has already shown its capacity for intercontinental spread. Infection leads to severe disease with a fatality of 20%, which is particularly concerning given the virus’ high attack rates. In addition, the novelty of the disease combined with its high mutation rate allows it to spread so rapidly, as populations have minimal immunity (Morens et al., 2009). While Agouti may pose a risk on a global scale, this threat however cannot be applied to every country and population in equal measure. Global inequality continues to widen, the United Nation’s 2020 World social report finding that more than 70% of the world’s population is living in countries with an increasing wealth gap. This has serious impacts on the wellbeing of those with low social-economic status, which corresponds to lower rates of education, employment opportunities and wealth, and ultimately leads to poor health outcomes (Smith, 2005). Therefore, the spread of infectious disease can be contemporarily viewed as an indication for

social inequality, with countries with lower economic prosperity taking the brunt of these infections (Singh, 2008). This phenomenon can be inspected through a multidisciplinary lens understanding how low socio-economic status is impacted by and perpetuates disease, medicinally, ecologically, psychologically, and geographically. Displaying the historical and contemporary idea that disease and poverty have a cyclical compounding relationship, as succinctly summarized by a Liberian epidemiologist during the 2014 Ebola outbreak, “those that didn't have basic sanitation, who had the most distrust of institutions they also had the most disease.” (Eisenstein, 2016).

Agouti is known to be a highly virulent zoonotic virus. Viruses are obligate intracellular parasites that consist of nucleic acid genome surrounded by a capsid protein coat (FRCPath et al., 2012). The Agouti virus enters the body through exposure to infected dust, saliva, faeces and urine. Upon infecting a cell, the virus is able to hijack the cell’s machinery in order to replicate and produce more copies of itself. As a zoonotic disease this means that its transmission occurs between animals and humans, allowing for reservoirs of animal populations to be infected with the virus (Ramachandran &

Aggarwal, 2020). In the case of Agouti, wild rodent populations are the primary sources of infection. Therefore, rural, and semi-rural communities with high rates of interaction between animal and human populations are where the disease will stem from. This concept underlines a key aspect in how not just Agouti, but other zoonotic diseases are more likely to impact rural and agricultural areas. This is of concern as rural communities globally are often critically underfunded and understaffed in terms of healthcare (Strasser, 2003) leading to both increased infection rates as well a lower baseline for general health of the community. Due to the fact the disease spreads through fecaloral transmission, this creates an opportunity for outbreaks in underprivileged communities with poor sanitation infrastructure. The origin point of Agouti is in East Asia where typically there is a lack of sanitation infrastructure (Chakravarty, et al., 2017) often due to water management issues (Asit, 2013). Therefore, dense, and highly mobile populations, such as slums, where inhabitants have poor access to public health are the perfect breeding grounds for this type of infectious disease (Eisenstein, 2016), allowing for rapid growth of the virus within communities of lower-socio economic standing.

Social inequality is by no means a new concept, it something that has been seen in civilizations since ancient times (Milanovic, 2007). It is theorized to have originated when humanity first made the shift from a hunter-gatherer lifestyle to organized societies, deemed the first epidemiological transition (Armelagos, et al., 2005). Which refers to a drastic shift in

disease ecology, with the introduction of social stratification, increased population size and cultivation of plant and animals as livestock. While this transition laid the foundations for social hierarchy that threatens the poor and underprivileged today, the second epidemiological transmission is much more pertinent to problems arising from the current Agouti threat. Predicted in the late 1960’s, the second epidemiological transition was said to be the largescale shift from prevalence of infectious diseases to “chronic” diseases (McKeown, 2009). This sentiment created a general belief in the Western world that pandemics were a problem of the past and initiated the shifting of reasources to battling lifestyle diseases (Armelagos, et al., 2005). However, in recent year this theorized transition has come under scrutiny, with many pointing out that it fails to recognize the significance of disease epidemiology, cultural and social beliefs and values, political influences, and health policy in developing countries (Defo & Barthélémy, 2014). This is in addition to added threats, such as the emergence of novel disease, i.e., Agouti, reemergence of historic diseases and double burden of communicable and noncommunicable diseases (Defo & Barthélémy, 2014). This shift of focus away from infectious disease late last century has led to the underestimation of infectious disease outbreaks, which has manifested in a lack of preparedness for pandemics. While Agouti is still in the early stages of spread, it can be predicted by looking at outbreaks such as COVID19, that authorities do not possess the infrastructure needed for tackling a pandemic level threat. Almost unanimously countries globally were

unable to provide an effective response to the COVID-19 pandemic, with many failing to rapidly perceive the threat that COVID-19 possessed (Villa, et al., 2020). This once again most impacted those of vulnerable low-income countries, with their inadequate health system capacities (Josephson, et al., 2021). From this comparison we can conclude that the Agouti threat would have a similar response, with poorer areas bearing the brunt of the impact. Not only are there physical health factors to bear in mind, but also many psychological factors to consider in the context of Agouti. These primarily include the set of beliefs held populations around the world that provide hurdles to overcoming a pandemic threat. These ideas are heavily intertwined within social hierarchies of cultures and incorporate their socio-political-economic factors. When focusing on dynamics within impoverished groups, it can be noted that there is a correlation between lower socioeconomic status and increased levels of governmental distrust (Eisenstein, 2016) (Shoff, 2012). Simultaneously it can be observed that higher levels of governmental distrust correspond to lower health outcomes, (Blair, et al., 2017) (Lee, et al., 2016) i.e., increased mortality rates in a pandemic context. This occurrence of distrust can be linked to the presence of historical systematic discrimination present in low socio-economic groups (Taylor-Clark, et al., 2005) producing lower levels of compliance with governmental regulations. This was witnessed with the 2014 Ebola outbreak in Liberia, where Liberians who distrusted government took fewer precautions against Ebola (Blair, et al., 2017). Similarly, in the

US during the 2003 childhood vaccination program, parents with higher governmental distrust government were seen to be more likely to doubt vaccine advice and seek alternative medicine (Lee, et al., 2016). This depicts a global trend that transcends geographic barrier, making it easy to denote a similar tendency in the emerging Agouti response. Furthermore, examination of external beliefs is also pertinent in understanding the psychological Agouti impact. As due to the origin point of the virus in East Asia and its tendency to affect rural and semirural communities, there is the high likelihood of the virus adopting stigmatization on global and national levels. This impact can be understood as the social burden of illness, resulting in exclusion, rejection, blame, or devaluation towards people or groups identified with a particular health problem (Weiss & Ramakrishna, 2006). The propensity for this behavior can be witnessed in the influx of racially motivated hate crimes against Asian people in the US, due to the similarly East Asian originating COVID19 virus (Gover & Harper & Langton, 2019). The impact of this behavior is still being examined but the potentially traumatic effects of these anti-Asian sentiments are likely to impact population mental health in profound ways (Misra, et al., 2020). However, already research shows that racial discrimination has been clearly linked to lower mental health, increasing likelihood of disorders such as depression, and anxiety (Vines, et al., 2017), allowing for the possible projection of negative mental impacts on Asian populaces globally due to Agouti future impact.

A key aspect of understanding any disease is to observe how the geographical environment interacts with pathogens, vectors and hosts, and their dynamic equilibrium (Mayer, 2000). Agouti is a virus that has originated in East Asia, where a recent La Niña event has caused an abundance of natural food sources (insects, vegetation) for the wild rodent reservoirs of Agouti. This abundance of food increased the wild rat population by ten-fold, allowing for the rapid growth and transmission of the virus within the animal population that lead to the human-animal zoonotic interaction. The frequency of extreme weather events such as this one is on the rise, with the rate of La Niña years projected to double from 1 every 23 years up to 1 every 13 (Cai, et al., 2015). This is a direct response of increasing greenhouse gas levels their exacerbated effects on climate change, primarily effecting already vulnerable tropic and subtropic regions by increasing the frequency and magnitude of flood events (Eccles, et al., 2019). For tropical regions such as Southern and Eastern Asia that are already prone to disruptive weather patterns such as monsoons and typhoons this increase could prove catastrophic. These impacts include not only the mortality rate after the initial event, but also its destruction of agriculture, livelihoods, and infrastructure (Ebi, et al., 2021). Essential infrastructure such as public health facilities, roads and trains, energy grids, and water treatment could be destroyed or rendered inaccessible during the initial incident and then unable to be reconstructed due to resultant economic losses (Bell, et al., 2018). The resulting lack of infrastructure can cause the outbreak and spread of a potential disease such as Agouti, as lack of

sanitation and unclean drinking water will produce more infections, that will then be unable to be treated due to destruction of public health services. This downward spiral not only creates more Agouti cases but also produces increasing severity of future outbreaks, contributing to the intensified devastation on these concentrated regions.

The emerging zoonotic Agouti virus is a current pandemic that, starting in East Asia, has spread intercontinentally to South Africa and Australia. The spread and impact of this disease has devastating impacts for principally those of low socioeconomic standing. This unequal burden is a global trend that manifests medically, ecologically, psychologically, and geographically. Increased rates of transmission occur in rural and semi-rural communities, as higher human-animal interactions are present. This is of critical concern as this rural healthcare is consistently found to be lacking in terms of funding, staffing and infrastructure, producing sizeable disease growth in low wealth communities (Eisenstein, 2016) This lack of infrastructure can be viewed as a systematic and historical process and are results of missteps such as the “second epidemiological transition”, when healthcare systems shifted priority to prevention of chronic diseases rather than infectious. Systematic issues also prevail to produce phycological impacts that heighten the spread of the virus. As it is observed that low socioeconomic status can be a product of historical discrimination which manifests in resistance to governmental procedures, contributing to a lower overall health baseline for impoverished communities. In

addition to this, stigmatization of groups associated with the virus can face negative psychological ramifications, specifically people of Asian decent due to Agouti’s origin point. Lastly, an observation was made concerning the increasing impacts of natural disasters in the tropics due to climate change. The economic loss and destruction of key infrastructure compounds the aforementioned scarcity of healthcare increasing transmission and mortality of the virus. From this multidisciplinary analysis of inequality, it becomes clear that addressing infectious pandemics like Agouti in a more holistic manner it is paramount to our survival not just as individuals, but on a global scale. As the wealth gap widens, more and more of our world will fall into the gaping chasm of poverty, falling ill and staying ill with no exit but mortality. We look towards structural and lasting change from the ground up, that will have cascading effects that improve wellbeing on an international scale.

Art X Nature

Lucca Harvey

Visual Analysis Using Gillian Rose’s Framework

Anonymous Visual imagery, more than ever, is embedded into every aspect of the world around us. Analysis of visual imagery can therefore provide critical insight into the current cultural, political, and economic landscape of our society. Gillian Rose has developed a framework for such interpretation. Central to the concept of her framework is the suggestion that there is no single way to interpret the plethora of visual stimulus that we encounter (Rose, 2016). The meaning of images is instead fluid through time, space, cultures, and audiences. Rose suggests a framework that evaluates four different sites at which meaning is made within the cycle of an image becoming part of our visual culture (Rose, 2016). These are the context in which the image is created (production), the content and composition of the image itself (image), the way in which the image is transmitted amongst its audience (circulation), and finally, the way in which it is received and interpreted (audiencing). Rose’s work further

suggests that at each site, three modalities of meaning making are at play. These are technological, compositional, and social (Rose, 2016). Through use of this framework, we can better understand the past, present, and future cultures of societies across the world.

On June 11th, 1997, tech entrepreneur Phillippe Kahn waited patiently in the Sutter Maternity Centre for the arrival of his daughter. As he waited, he devised a plan to create a system that would send a photograph of his newborn daughter to family and friends directly from the maternity ward. He connected a personal camera to his mobile phone using the speakerphone from his car. He then connected this device via a long wire to his laptop, which was connected to the server at his home. Shortly after, 2000 of his family and friends received a photograph via email, the first ever to be sent from a mobile phone (Nicholls, 2022).

Production

Friedrich Kittler argued that the technology used in the production of an image defines its form, meaning and effect (Jefferies, 2011). In this case, the photo itself was taken on a Casio QV, which was the first ever consumer-grade digital camera (Baguley, 2013). Given the technology available at the time, the camera specs were limited, captured at a resolution of 320 by 240 pixels. The images were also heavily compressed into JPEGS to save memory space, as the camera’s memory capacity was approximately two megabytes (Baguley, 2013). Given the development in camera technology since, this image would now be perceived as very low quality. The QV also had a split body which allowed the lens portion to rotate so the live image on the screen could be seen while shooting a self-portrait (Baguley, 2013). It is this feature that defined the form of the photograph, as Phillippe held the camera in one hand and his daughter in the other as the shutter snapped (Nicholls, 2022). This feature also predated the selfie trend that would come nearly two decades later.

In accordance with Kittler’s theory, beyond form, the meaning and effect of the image can also be defined by the technology used to produce it (Jefferies, 2011). Positivism is an approach to studying societies that gives validity and objectivity to empirical evidence (Ray, 2021). Positivistic naturalism regards the photograph as a mechanical copy of a scene, which requires minimal human interference. Those who view images from this perspective would perceive this photograph as containing an objective truthfulness that is not as prominent in other forms of imagery such as paintings (McQuire, 2018). Phillippe’s use of his Motorola StarTAC flip phone and Toshiba 430CDT laptop to immediately send the image compounds this effect on its audience (Nicholls, 2022). By reducing the time and human interference between when the shot was taken and when the audience received it, a positivist may perceive the technology

to be producing a more truthful representation of the natural scene. This use of the camera phone in this way established a certain trust between the audience and the photographer, therefore enhancing the gravity of the image.

Image

The content of the image itself carries vastly different meaning across different contexts and times (Rose, 2016). Roland Barthes work in semiotics primarily concerned how different signs within images can be interpreted differently across time and culture (Rose, 2016). He interpreted signs and signification as dynamic elements of the social and cultural fabric of societies. He further made the distinction between denotation, the literal meaning of a sign, and connotation, the secondary, cultural meanings of signs. While Barthes’ theory argued that as members of the same culture, we draw upon the same cultural codes to interpret images, it can be argued that there are even differences in how images are interpreted between individuals. For this reason, John Fiske argued that the audience is the most prominent site of meaning production, which directly opposed the previously accepted auteur theory (Mambrol, 2019).

This image, for example, may carry great significance for those to whom it is private. For the child’s parents, family and family friends, the context of the child’s birth is known and influential on their lives, and therefore the image representing this birth is significant to them. To others who do not know the context of this child’s birth, the image may carry its own personal connotations relative to the individual’s personal experiences. For example, to a woman is who trying to get pregnant but is having difficulty, the image may be a source of sadness and grief. Contrastingly, for parents who have recently become empty nesters, the photo may evoke nostalgia. The signs of the image thus convey a different meaning amongst different individuals.

Barthes’ theory that images are interpreted differently over time, however, can be used to further understand the meaning of this photograph. At the time it was taken using this new technology, the image was a source of curiosity for those who did not understand how it was possible. Decades later, the image is symbolic of the birth of a technology that would be carried daily by billions worldwide and transform the media landscape (McQuire, 2018). Of course, this interpretation of historical significance is dependent on if the context of the image is given. The linguistic text that can be seen underneath the image therefore plays a fundamental role in shaping it’s meaning. Barthes refers to this captioning as ‘anchorage’, as the text somewhat fixes the meaning of the image crosscontextually.

Circulation and Audience

The meaning of this photograph can further be drawn from its mode of circulation (Rose, 2016). Shortly after it was taken, the image was sent digitally to the emails of 2000 of Phillippe’s family and friends. Walter Benjamin highlighted that by the 1930’s, people were more likely to encounter an image in a newspaper or book than in a gallery (Shaw, 2021). In this case, the original recipients of the image are not only not viewing it in a gallery but are likely viewing it on a small screen within their own homes. Marshall McLuhan’s theory that the medium is the message provides a useful way to interpret how this affects the meaning of the image. McLuhan argues that the medium through which content is carried is fundamental to how it is perceived (McLuhan, 1973). When viewing an image in an art gallery, there are certain conventions that are followed such as not eating, remaining quiet, taking time to absorb the image, and viewing the image in a form that is of a certain quality. In the case of a family photograph such as this, it would have once been conventionally received while on the wall of someone’s home, where different specific set of spectating conventions apply. When receiving this photograph via email instead, such conventions are

removed. This greatly affects how the image is interpreted as elements of the home that would have once contextualized the image are no longer present. This mode of reception also renders recipients more prone to distractions, such as notifications on the device, which may impact their capacity for interpretation.

While mass image sharing can be argued to reduce the quality of an image and degrade the viewers ability to interpret it, it also must be acknowledged that this mode of reception has drastically broadened the audience that can see an image. Where the act of visiting art galleries was once a sport of the upper classes, this novel mode of circulation meant anyone with a digital device could immediately receive images at the same time as everyone else (Bourdieu & Darbel, 1997). This ultimately opens the image up to a greater range of interpretations across different cultures which may be seen to enhance its overall meaning. This digital circulation further facilitates the audience’s much more active role in contemporary art practice, compared to the very passive act of viewing images in galleries or on the walls of family homes. Thus, the way this photo circulated can be perceived as symbolic of the birth of increased autonomy for the everyday person to capture and circulate images on their own accord. This ultimately led to a mass shift of power from large media conglomerates to the public, allowing them to share their perspectives and thus help to shape the narrative on political and social issues. This increased flexibility in the organization of production techniques is described by David Harvey as the visual representation of a move away from the postmodernist orbit (Rose, 2016).

In 2016, TIME magazine included this photo in their 100 most influential images of all time. What may be initially interpreted as a mundane example of everyday photography has transformed into an image of great historical significance for what it represents in terms of the birth of autonomous and instantaneous image sharing

practices. Gillian Rose’s framework allows us to understand this transformation of meaning as we analyse the images movement through the sites of production, composition, circulation, and reception (Rose, 2016). The framework is particularly useful as it considers images in their social, economic, and technological contexts. Therefore, the interpretation gathered through use of this tool is never stagnant and would likely produce a different outcome over time and across different cultures. For example,

while this image may now represent the autonomy that image sharing has afforded us, in the future, it may carry connotations of a shift toward a world that is over reliant on digital technology and lacking authentic human connection. Such exemplifies the process of the evolution of meaning of visual images and highlights why visual analysis is so fundamental to understanding societies.

Father Time I

Georgie Macho

Stretched out from his mother’s womb, Kronos wielded a scythe a blade brandished in moonlight, sharp enough to cut even the godliest golden flesh. It had been a gift from his mother, perhaps she too had wished he would unleash the weapon on his father. With one swift swing, Kronos struck Ouranos, castrating him. The act of a vengeful son.

A final blow from son to father left Ouranos a still corpse, and in the chaos of the fight, the castrated scraps of masculinity were flung into nearby water. His flesh fizzled and foamed. Out of its bubbling trail, a woman arose. One of such otherworldly beauty, time itself stopped to watch her birth.

Yet nothing can truly stop time. And as it passed, the heroic titan fell victim to the fate of Ouranos. Cursed with the same plague of paranoia, he devoured his six children. Each one buried within the pits of his bottomless stomach, alive and well they waited for the trickery of Rhea and Zeus to rescue them.

History repeated itself. Yet again did son battle a tyrannous father and succeed. Though Kronos’ fate was one worse than death. Banished to Tartarus for eternity in unending suffering. But Father Time lives on, stealing the lives from the unexpecting.

Father Time II

Georgie Macho

Days in the sun freckle our faces memories carve wrinkles in my mother’s skin years of happiness frame her smile in gentle grooves, reminders of time unpromised.

How do you know when you will be taken? Sent to drown in the river of souls. Will the midnight tick of the corpus clock be my last?

Steady streams of sand flow, slip through gaps of greedy fingers that try to hold on. I coat my hands in honey to try and retrieve all the grains But I can’t get it all. I can’t bring back the moments I’ve lost I can’t hold onto the present.

If I go today, have I wasted my time worrying about just that? Do I accept destiny and fall into the cradling arms of death?

Father Time have mercy, I cannot go yet, for I have not lived.

Growing an Australian seed: Graeme Murphy and Sydney Dance Company

Zodie BolicHow do we come to know dance and what are the social, political and cultural forces that influence what dances survive and come to be appreciated as part of a dance canon?

G Graeme Murphy is arguably Australia’s foremost choreographer, working across ballet, contemporary dance, musicals, film and even ice-skating. Appointed at just 26 as Artistic Director of Sydney Dance Company (then named Dance Company (NSW)), it was his 30 years of leadership that guided Sydney Dance Company to the very forefront of Australian dance and allowed him to develop both his talent and his reputation as a choreographer. Murphy reflects on his time with the company and his career with great eloquence, describing the Australian dance industry as an Australian plant. While imported dance trends are pretty, like a rose garden from overseas, they will fail to survive the first ‘harsh attack of the elements’ because they are not suited to the Australian context (Murphy, Graeme Murphy interviewed by Hazel de Berg in the Hazel de Berg collection, 1981) Murphy asserts that for dance to survive in Australia, it must reflect this country and be of this country. In this essay, I will argue that Murphy himself has survived in the Australian dance industry because of his willingness to cultivate an Australian seed, being his own Australian dance idiom. I will illustrate this by discussing Murphy’s ability and willingness to collaborate with other Australian artists and his dancers, his influence on other Australian choreographers, his ability to

situate work in Australian contexts by discussing his adaption of The Nutcracker, alongside some of his other works, and the effort he has put in to documenting his works and processes for the future.

Murphy’s work with Sydney Dance Company shows a great reliance on Australian creatives, and this reliance is an integral part of Murphy’s success as an Australian choreographer. Murphy’s first full length work at Sydney Dance Company, 1978’s Poppy (based on the life and art of Jean Cocteau), has been described as a ‘landmark’ in Murphy’s use of Australian composers, with the work being performed to an original score by Carl Vine (Murphy, Interview by Martin Portus, 2016). Vine had been the Company’s rehearsal pianist before Murphy asked him to compose, and thus was deeply familiar with the company and its dancers (Murphy, Interview by Martin Portus, 2016). Vine would remain a close collaborator of Murphy’s during his time at the helm of Sydney Dance Company, with his music being utilised multiple times, up until Murphy’s resignation in 2007 (Murphy, Interview by Martin Portus, 2016) (Stell, 2009). Another musical collaborator of Murphy’s is Michael Askill, of the percussion group Synergy. Featured in Synergy with

Synergy, and Free Radicals, Askill is a true Australian artist with an Australian career (Daly, 1997). Kristen Fredrikson (born Frederick John Sams) was another favoured collaborator, and despite his New Zealand birth and citizenship, had a very Australian career (Murphy, Interview by Martin Portus, 2016). Fredrikson worked with Murphy on many works, but to notable acclaim on 1985’s After Venice, 2001’s Tivoli and 2002’s Swan Lake (Murphy, The Heritage Collection, 2022) It is these collaborations with Australian artists that makes Murphy’s work so uniquely Australian. Rather than ‘kangaroos or beer cans’, Murphy’s work is Australian because of the Australians he works with (Daly, 1997). Murphy himself stated that ‘the Australian Opera are so world class because its artists, its singers, its designers, its directors, are all Australian’, and Sydney Dance Company under Murphy’s leadership therefore can be no different (Stell, 2009). Jill Sykes (2007) writes that Murphy’s work ‘emerges from an Australian sensibility’ because Murphy himself knew he would survive if he focused on originality. The originality of Murphy’s work is its Australianness. Thus, through his collaboration with Australian artists, Murphy makes his work uniquely Australian, setting himself apart from his overseas contemporaries and ensures a legacy in the Australian dance world.

Under Murphy’s directorship, the dancers are equally as important to this collaboration as the designers are, and therefore the dancers’ Australianness is just as key as Murphy’s designers. Murphy remarked that dancers should be ‘contributing artists’, rather than just the ‘instrument’ of the choreographer

(Sparshott, 1995). Good dance collaboration between dancer and choreographer, rather than prescription (Stell, 2009). Therefore, we see this ‘Australia sensibility’ emerge again, due to Murphy’s use of homegrown dancing talent (Sykes, 2007). Sydney Dance Company’s ranks under Murphy were representative of Australian talent and multiculturalism (Sykes, 2007). Murphy rejected ballet’s conventions in terms of appearance, taking on talent no matter the shape and size. Murphy even remarks that while not all his company dancers (in the early stages at least) were necessarily the most technically profit, they were ‘creatively sublime’, and, Australian (Murphy, Interview by Martin Portus, 2016) (Murphy, An Interview by Paul Taylor, 1980). Therefore, when involved in the creative process, as Murphy wished his dancers to be, their innate Australianness influences the work, and nurtures the idea of this Australian plant.

In a 1980 interview with Paul Taylor, Murphy asserts that Australian dancers are ‘easily picked’, due to their ‘virility’ (Murphy, An Interview by Paul Taylor, 1980). Murphy exploits this virility throughout his works, adding another layer to his work that makes it uniquely Australian. If virility is a characteristic American dancers do not possess, they therefore cannot dance any dance that is built around it (Murphy, An Interview by Paul Taylor, 1980). This results in another layer of originality for Murphy’s works, and further cements him as Murphy as an original, Australian choreographic voice. Graeme Murphy has remained a relevant cultural force in Australia because of his willingness to be Australian, and work closely with Australian talent of all kinds.

Murphy’s willingness to nurture other creatives has also resulted in him remaining a force in Australia’s dance scene. Under Graeme Murphy’s leadership, Sydney Dance Company welcomed many artists who would go on to become leaders in Australia’s cultural scene. Gideon Obarzanek (founder of Chunky Move and current chair of Melbourne Fringe), Stephen Page (Artistic Director of Bangarra Dance Theatre from 1991-2021) and Paul Mercurio (star of Baz Luhrmann’s Strictly Ballroom and founder of Australian Choreographic Ensemble Hastings) all danced at Sydney Dance Company at the early stages of their careers. Murphy supported his dancers to explore their own choreographic pursuits, providing opportunities through Sydney Dance Company for the staging of their works (Murphy, Interview by Martin Portus, 2016) (Sykes, 2007). These opportunities provided by Sydney Dance Company under Murphy’s leadership speak to his willingness to nurture Australian talent. It is then of course, clear why Murphy has remained so at large within the Australian world. If so many of Australia’s modern-day artists can be linked back to Murphy’s Sydney Dance Company, it is clear that Sydney Dance Company and Murphy provided an environment rich for collaboration and growth. Murphy’s long history of collaborations with the Australian Ballet and the Australian Opera have also allowed his work to survive (Murphy, Interview by Martin Portus, 2016). With multiple opportunities for the display of his art, Murphy ensures that he will remain a force in the Australian Arts industry simply because his work is everywhere, and not easily escapable.

Graeme Murphy’s 1992 work Nutcracker: The Story of Clara (created for the Australian Ballet) shows Murphy’s success in creating work for Australian audiences, and thus his ability to last as a choreographer and artist and nurture this ‘Australian seed’. In Murphy’s work, he recontextualises the classic ballet to become a quintessential Australian tale. In his version, Clara is an aging Russian ballerina who once danced in the Imperial Ballet (Potter, New Narratives from Old Texts: Contemporary Ballet in Australia, 2021). Murphy takes us back in time to trace her life, witnessing her early ballet training and her career, before her life is changed by the Russian Revolution. Her lover leaves for war, and his death shatters Clara. She departs Russia for the Ballet Russes, which eventually leads her to Australia (Potter, New Narratives from Old Texts: Contemporary Ballet in Australia, 2021). As the 2nd World War ends, Clara joins the newly established Borovansky Ballet, the company which was the foundation for the establishment of the Australian Ballet. Murphy’s radical adaption has been called the ‘gumnutcracker’ for its unique Australianness, as Murphy has undeniably made an Australian text (Potter, New Narratives from Old Texts: Contemporary Ballet in Australia, 2021). Despite it’s Australianness, the work still holds universal appeal in its themes (Potter, New Narratives from Old Texts: Contemporary Ballet in Australia, 2021). While Nutcracker is perhaps the most obvious example, all of Murphy’s work show his deep understanding and ability to appeal to Australian audiences. For Murphy, there is no point in simply recreating what had been done before (Murphy, Interview by

Martin Portus, 2016). Work had to appeal to specific audience to be successful, and Murphy’s audience was Australia (Murphy, Interview by Martin Portus, 2016). Another of Murphy’s work that clearly establishes an Australian context is his Rumours trilogy, in which we see an exploration of Sydney that is both ‘serious and sensitive’, and instantly recognisable to Sydney audiences. (Sykes, 2007) Rumours provides a study of the Sydney lifestyle in great clarity, and therefore holds great appeal for a Sydney audience. While not all of Murphy’s work is as blatant as Rumours or Nutcracker in its portrayal of Australia, all his work is inescapably Australian. 1982’s Homelands is never explicit in its setting, but the harsh landscape that is depicted evokes feelings of the Australian bush all the same (Sykes, 2007). Yet again, it maintains a universal appeal with its tale of longing and fragility. It is Murphy’s willingness to create work specifically for his Australian audiences that has allowed him to maintain a career here. By feeding his Australian plant with Australian work, it is nurtured and grows, however his work also succeeds on its own merits because of the universality of its theme and content.

Like a plant or a flower, Murphy demonstrates his own interest in his and his work’s survival through his own efforts to immortalise him and his work. Murphy is one of Australia’s most documented dance figurers, but much of this documentation is the fruition of Murphy’s own efforts. Notably Murphy presents The Heritage Collection (with the support of filmmaker Philippe Charluet), which documents most of his career prior to 2007 (Murphy, The Heritage Collection, 2022)

This collection is extremely rich, featuring remastered videos of works, links to reviews and the original compositions. It also provides a work’s synopsis, any choreographer’s and music’s notes if available, a complete credit list and photo gallery (Murphy, The Heritage Collection, 2022). Amongst Australian dance figures, it is possibly the most complete, and easily accessible collection. Many of Murphy’s works are available to study now, with more coming soon. Murphy is also the subject of many interviews, demonstrating a willingness to speak about his career to anyone who may be interested. Without the desire of Murphy to share and preserve his work, it is questionable Murphy would remain in Australia’s memory. However, because he has done so and to such a high quality, Murphy has all but guaranteed the continued existence and influence of his work long into the future. When a young choreographer can look up Murphy’s work with ease, Murphy cements a legacy of his work through those to come. Murphy’s success in preserving his work guarantees it will remain an influence in Australia dance scene, and therefore illustrates to us how Murphy intends his dance to survive.

Almost 15 years since his departure from Sydney Dance Company, Murphy still looms large over Australia’s dance scene. Whether it is a comparison of Murphy’s Swan Lake to the recently opened Australian production of Rodgers and Hammerstein’s Cinderella, a solo by Isaac Clark in Sydney Choreographic Ensemble’s Galileo recalling Murphy, or a return season of Murphy’s adaption of Madama Butterfly, Murphy casts a shadow no one can escape. Because of Murphy’s

utilisation of Australian designers and dancers, his work is uniquely Australian, and therefore original. His nurturing of other Australian creatives through opportunities at Sydney Dance Company have made him a key part of other’s legacies, and therefore ensures he survives if they survive. Furthermore, Murphy’s ability to create dance for his Australian audience and utilise Australian context also sets him apart, as well as creating a large appeal for his audiences. Finally, Murphy’s willingness to document his work himself in detail ensures he remains a source of knowledge for Australia’s dance industry, and therefore he ensures his place as an influence for the future. All this combined show how Murphy has cultivated an Australian plant through a uniquely Australian career, and thus ensured he and his dance survive as a force in Australia’s dance industry.

.

Urban Design Techniques: Ohonua Tonga

Philippa McWilliams

Urban Context and Site Analysis Existing Neighbourhood Context Analysis

Spatial Analysis: Movement

2. Distance from a Local Household

1. School Bus Route

4. Current Road Conditions - Accessibility

3. Road Quality

Stakeholder Analysis Report

Vision

Our vision will support a socially and environmentally resilient response within the volatile site. Our project in blocks 4 and 5 of Ohonua, Eua will allow local residents to feel they can live safely and sustainably whilst celebrating their cultural traditions. The community will feel proud of their invigorated residential area and spend quality time in the new public open spaces. A locally specific design will respond to the small scale and agricultural setting. Our vision will aim to support a resilient yet attainable proposition within a volatile natural environment

Design Principle 1: Restoration of Roadways

The restoration of roadways will help contribute to safe travelling and accessibility. Due to the 2022 tsunami and weathering, current road conditions are unreliable. Mitigation of potholes, rocks and extreme terrain differences will alleviate damage to vehicles, and aid in effective and efficient road transportation.

This benefits the overall community, especially elders who may rely on vehicle transportation to navigate the island

Design Principle 2: Increase Accessibility Through the Construction of Bike Paths and Pavements

As a small town, the reliance on efficient walkability is crucial for day-to-day life, hence the development of bike paths and pavements aids in a green method of movement. The degraded condition of ‘Ohonua’s roads create an unsafe environment for cyclists. Dirt roads and uneven land can deter residents from utilising certain routes, affecting travelling time and ease of movement when commuting to jobs, school, or other areas of the island. The construction of defined bike lanes upon concrete paving promotes

active and eco-friendly transportation around the area, allowing locals in previously unreachable areas to now have accessibility. Furthermore, define bike lanes and walking pavements create a sense of safety, as the threat of automobiles is now mitigated.

Conceptual Plan

Due to the small scale of the town of ‘Ohonua, many residents navigate the area by foot or bike. With poor road quality evident in ground images, many areas present hazardous conditions to all modes of transport. Hence implementation of a concrete road systems is needed for a functioning community

Effective transportation systems also aid those living on the island with mobility issues. With limited resources available on the island, elders and people with disabilities can have more accessibility to various areas of the island previously unobtainable

Replacing the grassland outside of the property, pavements allow for defined walking areas, as well as the ensured safety from bikes and cars. Having raised pavements further set boundaries for vehicles, providing safety to those travelling around the island by foot.

Concrete is a reliable material. Its longevity allows for 20 to 40 years of usage and is a much greener option than asphalt. Moisture within the soil and rain

are unable to penetrate the concrete, hence resistant to deterioration, especially in Tonga’s humid and wet climate

Drawbacks

Drawbacks include the cost of concrete as it requires heavy machinery and labour to implement. Furthermore, repairs are costly due to the entire slab needing to be replaced, as opposed to just filling a pothole

Analysis of the features and applications of 1080 (Sodium fluroacetate) as a pest poison

Bess HamshawIntroduction

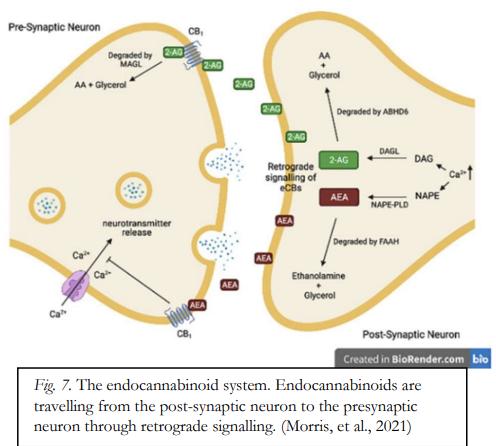

Sodium fluoroacetate (FCH2CO2Na) is an organofluorine that is colloquially referred to as ‘1080’, which designates the catalogue number of the colourless, tasteless poison. 1 Sodium fluoroacetate is used as a pesticide to control invasive species including foxes in countries including Australia and New Zealand.2 It is found in flowering plants of the genus Gastrolobium which are native to Africa and Brazil, but are most abundant in Australia.3 Notably, Indigenous Australian animals including Trichosurus vulpecula (Brush-tailed possum) and Macropus fuliginosus (Western grey kangaroo) have no adverse response to consuming plants containing sodium fluoroacetate2. In introduced species however, sodium fluoroacetate causes metabolic inhibition when either consumed directly or through secondary poisoning.4 Therefore, through being relatively species specific along with odourless and tasteless, 1080 has been considered an effective and efficient means for controlling introduced species. However, due to the methods by which 1080 is distributed, unintentional poisoning of non-target species, notably domestic and working dogs is unfortunately common. This ramification along with the features and alternative solutions to invasive species will be discussed in this report.

Features of sodium fluoroacetate and method of implementation

Fluoroacetate has a similar chemical structure to acetate, a molecule which is used in cellular respiration to combine with coenzyme A to form acetyl-CoA. 3 If 1080 is consumed, fluoroacetate will instead bind with coenzyme A, resulting in fluoroacetyl CoA. This molecule will then enter the tricarboxylic acid cycle, resulting in the allosteric inhibition of aconitase and the cycle being inhibited.3 As oxidative metabolism is impaired, this results in decreased energy production and restriction of gluconeogenesis, generally leading to the death of the consumer within 6-48 hours.5 In addition to being relatively fasting acting and species specific, 1080 is a favoured toxin due to being water soluble, meaning the likelihood of bioaccumulation and secondary poising is reduced.1 Additionally, through acting to decrease the number of invasive species in habitats, adverse effects such as environmental degradation and loss of biodiversity are decreased. Moreover, sodium fluoroacetate is dispersed through baiting programs, whereby small pellets containing 1080 combined with carbohydrates and proteins are distributed via methods like helicopter drops.2 As a result, the toxin can be quite easily dispersed in large areas, targeting high numbers of pests.

The repercussions for domestic and working dogs and why this occurs Different animals have different sensitivities to 1080 and this is reflected by

the LD50 or the dose that produces a lethal effect in 50% of the population.3 In particular, vertebrate, introduced animals are very sensitive to sodium fluoroacetate and this is why the toxin is a means of targeting non-native species. However, as a result of the method of distribution, sodium fluoroacetate has large risks for non-targeted species, notably dogs. Species within the family Canidae are particularly sensitive to the toxin and have a lower LD50 than other species such as birds and aquatic animals. 5As dogs and foxes are both members of the family Canidae, this presents concerning disadvantages for the use of 1080 as a means of invasive species control. Dogs have a very low LD50 of 0.06 mg/kg, meaning only a small quantity of 1080 is required to induce death. 5 This, combined with the fact that the toxin itself is embedded within easily consumed and appealing pellets means the risk of dogs consuming the pellets is serious.

Upon consumption of 1080 in dogs, symptoms including muscle contractions, seizures, vomiting and rigor mortis are common to occur before an almost certain death.6 These symptoms are generally synonymous between species, which presents another issue of if this poison is humane for even targeted species, as these symptoms can continue for many hours and up to two days.5

Even with early detection, it is unlikely for a dog to recover from 1080 due to the rapid onset of symptoms and lack of antidote.6 As a result, sodium fluoroacetate has an approximate 75% mortality rate in dogs.4 In areas where 1080 has been distributed, this has had devastating effects

on domestic and working dogs, both emotionally and financially.

Alternatives to sodium fluoroacetate

To address the detriments caused by the use of 1080 as a pesticide, alternative solutions to combat invasive species should be considered. One option for this, is the use of immunocontraception or controlling pests through fertility. 7 This focuses on inhibiting the ability for invasive species to reproduce rather than mortality and often uses a vector to transmit a pathogen which will damage the animal’s fertility.7 This method however, is extremely complex and expensive due to the need for large amounts of research. Another alternative is using cyanide as a toxin. Cyanide is more fast acting than 1080, with the mean time between consumption and death being 18 minutes, compared to 1080 which is 11.5 hours.4 It is also rapidly broken down by the animal, and hence the risk of secondary poisoning is very low. 8However, cyanide does not specifically target species and so there is still a high risk of non-target species ingesting the poison. A final alternative is trapping. An advantage of trapping is that it is easier to target particular animals through being able to select the type of trap, bait, pheromones and the location. 9Additionally, traps kill animals quickly and can be monitored remotely due to wireless connection. However, it can be challenging to implement in rural areas and is expensive.2

Conclusion

Sodium fluoroacetate is a toxin used to control vertebrate invasive species, and inhibits aerobic metabolism through

allosterically inhibiting a key enzyme in the tricarboxylic acid cycle.3 It is a odorless and tasteless substance which is often distributed in pellets, combined with macronutrients such as carbohydrates and proteins to appeal to pests.2 However, due to this distribution method, LD50 distribution is non specific and often results in the death of non-target species such as dogs.6 This repercussion, along with the inhumane death which results from ingestion indicate that it is important that the ramifications of its use be mitigated. Due to the specificity and cost effectiveness of 1080, it is suggested

therefore to implement stricter restrictions on the use of Sodium fluoroacetate due to the lack of better alternatives. These could include better warning to communities, restricting where it is distributed, placing the pellets individually in specific locations and collecting the bodies of animals that have died from poisoning. These changes would aid in reducing the detriments of sodium fluoroacetate so that the benefits can be utilised to manage the growing issue of invasive species and the environmental, ecological and economic impacts they incur.

Romanticism

Anonymous

I wasn’t sure why I did that. Why I got attached and invested so quickly. I think I just romanticised it. The same way I romanticised everything.

Created a story of how I wanted it to be. Laid this in the place of what it was. Ignored the truth, Preferred to enjoy those moments of utter fiction.

A beautiful lie crafted Gently, perfectly, idealistically In my hopeless, dreamer mind. I wished I would stop doing it.

For there is not much worse than that cold Kiss of reality when dawn comes.

Shining a cruel light through my pretty façade, And presenting the world in all of its’ loneliness.

Always wept.

Anonymous

For the joy of reclaimed kingdoms And happy endings and The dread of returning To my world of mundanity.

Of the evil being more Surreptitious and underhand Than is possible to reveal Let alone overcome.

And the princesses who didn’t Really fight wars and save kingdoms, But cried in rooms over stupid boys Who weren’t knights after all.

This place where reality Threatened to crush me, If I dared remove my nose from Between those crisp, white pages.

Justice for Extinction

Ally Hardy

What duties of justice, if any, are owed in the present as a function of harms done in the past to people now dead, or future interests of people not yet born?

The extinction of species due to direct and indirect human actions has increased substantially in the last century, causing necessary reflection around what kinds of justice, if any, are owed and to whom. Using the case study of the passenger pigeon, this essay will argue that duties of justice ought to be owed to living members of species for extinctions that otherwise could have been avoided. This expands upon John Rawl’s Theory of Justice and marries the disciplines of environmental justice and political theory to extend justice to non-human animals, as well as ruminate on responsibility for historical injustices. The first section will outline Rawl’s conceptualisation of the “original position” and then situate this with non-human animals (henceforth animals). The next section will pair the original position with species extinction and demonstrate how duties of justice necessarily arise from this. Then, in section three, I will briefly introduce the passenger pigeon and argue that duties of justice ought to be owed because of the severity and precedence of the multiple harms committed. In light of this, the fourth section will examine to whom these duties are owed and what form these duties take, questioning whether the harm reflects the need to use restorative justice like deep de-extinction. The final section will present two counterarguments against de-extinction and instead offer reparative justice for current individuals of

species as a more reflective duty of justice for the harm caused. I, therefore, reiterate that humans alive today ought to owe reparative justice towards current members of species as a function of injustice committed to the extinction of species as a result of direct human harm.

While John Rawls’ Theory of Justice does not include animals as benefactors of principles of justice, the idea of the “original position” can and should extend to non-human members of society. Rawls’ (2004, p. 13) defines justice as a socially ordering principle by which members of society ought to be given what they are due. This is conditional on two key caveats: that citizens are (1) moral equals and (2) can freely agree upon basic principles of a fair society, ie. principles of justice. Once satisfied, citizens are asked to decide upon society’s basic principles but must do so unclouded by “circumstances of the existing basic structure”, assuming the “original position” (Rawls 2004, p. 18). This thought experiment removes one’s background and identity and asks what a fair and just structure of society would be without this information. At face value, the original position has considerable merit for theorising some kind of universal idea of equality for many members of society, especially for those that are marginalised under current institutions. Yet, from the first caveat, animals have their membership

excluded from these considerations. As Plunkett (2016, p. 14) contends, while animals may have ethical status, they “do not have the same ethical standing” as human beings and so, they are not morally equal. This means that they are naturally excluded from participation or even consideration in the original position. Many scholars, Rawls included, have stood by this conclusion as the end of discussion around justice for animals. However, the original position itself provides the necessary framework to extend Rawlsian justice to animals.

Casting away the two caveats for a moment, the original position offers an appropriate theoretical basis for conceptualising duties of justice for animals. In removing the awareness of one’s situation in the real world, Elliot (1984, p. 100) surmises that citizens might, upon revealing their actual position, “find that they are animals”. The original position only requires participants to be rational, self-interested beings, not necessarily human, with some knowledge of what the world could hold for them. Rawls’ (1971, p. 137) original contention disagrees with this as it purposely sets out that participants “know the general facts about human society”. However, such a statement does not remove the possibility of information concerning animal interests and desires to be interjected into the original position (Gardener 2010, p. 5). We can understand their ability to feel pain and pleasure – their sentience – as reason enough for them to be appropriate objects of moral concern and so, know what the world would entail (Valentini 2013, p. 39). Additionally, Rawls’ (1971, p. 448-9) himself outlined that he does not believe a “capacity for a sense of justice” is necessary to be owed duties of justice and be included

in the original position. Subscribing to such a belief would mean the exclusion of humans incapable of this from justice such as infants and those that are cognitively impaired. The original position necessarily includes those without that capacity to ensure all beings with ethical status are owed duties of justice despite being unable to reciprocate the same principles. In this light, it would be unjust to exclude animals from the original position. Therefore, the original position applicability to nonhuman beings suggests that duties of justice can and ought to be extended to animals.

Now that animals are afforded duties of justice, what happens in the context of entire species where these duties have been harmed in the past? There are multiple variables at play so for the sake of narrowing the scope, the focus will be on duties of justice owed to extinct species that were directly harmed by avoidable human activities. Regarding what the duties of justice could look like, Valentini (2013, p. 39) outlines the two universal duties that are generally acknowledged: the first a “very stringent” duty to not harm others and the second, a duty to help when others are in need. The former is most suitable to discuss justice in the case of extinction. If animals are included in the original position, which we believe they are, then individual animals are afforded the duty to be not harmed by other citizens in society. So, in the case of extinction caused by avoidable human harm, it would appear that such a duty is easily transferable and constitutes an injustice on behalf of that species. Yet, species are not individuals and therefore, do not have the same sentience that the original position and duties of justice are predicated on (Rolston 1985, p. 723). This would suggest that species cannot be wronged the

same way that an individual animal can be wronged. But, as Rolston (1985, p. 721) indicates, species are “living historical form, propagated in individual organisms, that flows dynamically over generations”. So, an injustice committed against one individual where there is identifiable and consequential harm to other members of the same species would constitute an injustice against the whole species. Weinhues (2020, p. 149) echoes this point, suggesting that “extinction of a species indicates … that severe injustice has been done [to individuals] by heavily impeding their flourishing and ability of survival” and resulting in the species termination. It is thus apparent that although duties of justice do not arise for species per se, harms committed against individuals that ultimately lead to the extinction of a species is an injustice that deserves subsequent duties. This understanding is best represented through the case study of the passenger pigeon.

The extinction of the passenger pigeon provides the perfect example of a historical injustice where duties of justice ought to be owed. Regional to the eastern parts of North America, the passenger pigeon was a species so abundant in size that is numbered in the billions (Guiry 2020). Yet, by the turn of the 20th century, there were only a few hundred in captivity. Bucher (1992, p. 23) believes this to be a result of “mainly habitat destruction and fragmentation, coupled with the initial intense human predation”. If this is true, it would appear that the harm was largely unavoidable because the moral concern of human resources would have outweighed the moral concern for trees and the species relying on those trees for food. This follows Welchman’s (2021, p. 520) argument that

when there is no certainty around injuring a wild animal’s life prospects, “we cannot be obliged to avoid harming them” or owe them justice for harms committed. However, Bucher’s account differs significantly from more contemporary research by Guiry (2020) where it was found that the unregulated commercial pigeon industry and sport hunting were the most “important drivers” behind the passenger pigeon’s extinction. This would suggest direct avoidable harm was taken against individuals within the species which culled their population to a size no longer recoverable. To this end, duties of justice ought to be owed for the extinction as it was direct avoidable harm on individuals’ capacities to pass on genetic information and contribute to the continuation of the species. But to whom are these duties owed? And what should they look like?

As duties of justice are highly contextual and require different remediations depending on the harm, to whom the duties are owed and what they are must adequately reflect the injustice committed. Regarding this case and what has previously been argued, one would assume that the duties’ recipients ought to be the individuals who were harmed, and those that committed the harms must pay forward. Yet, the historical nature of the injustice makes it especially hard to owe those duties because “none of the parties directly involved remain alive” (Welchman 2021, p. 522). This, however, does not remove the severity of the injustice and the kind of precedence it sets for current and future generations.

One possible restorative duty that could reflect the severity and moral obligation could be deep de-extinction. Sherkow and

Greely (2013, p. 32) describe deep deextinction as an umbrella term for three main scientific techniques aimed at ‘bringing back’ species: “Back-breeding, cloning, and genetic engineering”. This type of duty is advocated for on the premise that humans “have done something wrong” to cause the extinction and if we have the technology to do so then current generations owe it to extinct species to bring them back (Sandler 2014, p. 355). This position is further accentuated in cases where direct, avoidable human activity was the main reason for the extinction and so, the species would still be alive today if that injustice had not been caused. Hence, deextinction appears to ‘right the wrong’ and make it so that the species was never extinct in the first place.

While de-extinction appeals to the severity and the moral obligation of the harms, there are many reasons why de-extinction does not directly address the injustice caused. The two main reasons are (1) the ramifications it will have for individuals ‘brought back’ and (2) how it attempts to owe justice directly to the extinct species, rather than the individuals. Firstly, those animals born from the de-extinction process “could end up suffering” either from the process itself or the genomic variation they end up with (Sherkow & Greely 2013, p. 32). In both circumstances, there is a compromise on the duty to not harm other individuals for the sake of the rebirth of the species. And, as stated before, a species cannot be afforded duties of justice because it is not a rational, selfinterested being – only individuals within said species are afforded justice. To this, Welchman (2021, p. 529) argues that duties to extinct species should be “owed to living individuals of other species, not the extinct

species itself”. This not only satisfies the historical nature of the injustice but also shifts the narrative away from the past harm and instead, towards remedying the precedence the injustice sets. This adopts a “repatriation and rehabilitation” approach to justice, focusing attention on the very practices and institutions which continue to allow these same harms to occur (Sandler 2014, p. 356). Thus, the current human population owes a duty of justice to living individuals of species who suffer the precedence of the passenger pigeon’s extinction.

Anthropogenic activity on Earth continues to place animals in situations of direct and indirect harm. Many Rawlsian scholars do not recognize this harm as constituting an injustice because they do not equate nonhuman animals as moral equals and so, excluded them from the original position. Yet, the original position, with its inclusion of all rational and self-interested beings, provides the necessary framework for extending justice to animals. Following this line of thought, humans owe a duty to not harm other individuals, especially concerning direct and avoidable harm. So, if this has been breached, which is the case for the extinction of the passenger pigeon, there is a duty of justice owed. But for such historical injustices, the duties of justice must reflect the severity of the harm while also understanding the intergenerational nature of the injustice. A restorative duty like deep de-extension considers the seriousness but does not address justice for individuals, rather solely looks at justice for the species which cannot be afforded. A more satisfactory justice approach sees duties owed to current living individuals of other species and aims to address the institutional harms resulting in the

passenger pigeon’s extinction. I, therefore, conclude that duties of justice ought to be owed to present animals as a function of the

multiple avoidable harms committed against extinct species.

Geology of the Buchan Valley

Luella DrinnanAbstract:

The Buchan Valley is a synclinorium featuring volcanic bedrock and overlying sediments formed as early as the Late Silurian period. Sedimentary and karstification processes are still occuring in the landscape, although many of the sedimentary units were formed during the Devonian period. Fossils indicate the environmental conditions of each unit, ranging from deep marine to coastal lagoon ecosystems. The Buchan Valley area has experienced stress and tension resulting in folding and faulting within in multiple units. The analysis of fossils, traits, structural features, relative stratigraphy and location of the units suggest that the Buchan Valley area experienced fluctuating coastlines, environmental conditions and biotic diversity, tectonic stress and intrusive magmatic processes with continued experience of sedimentary and karstification processes.

Introduction:

This report discusses geology in the Buchan Valley in East Gippsland, Victoria (Fig 1) and interprets the observations taken in the field on a week-long study in June 2022. Direct field observations were taken from Area 2 (Fig 2), with data in the broader Buchan Valley Area taken by fellow geologists on the field trip.

Figure 1 The red marker shows the location of Buchan in Victoria.

Figure 2. The broader Buchan Valley area ranging from Buchan to Murrindal. Area 2 study area was located in the northern area around Murrindal.

Stratigraphy:

The Buchan District features volcanic bedrock with overlying sedimentary units, displayed in the Figure 3. Each unit is described below in stratigraphic order.

Diagram of the stratigraphy in the Buchan Valley.

Snowy River Volcanics: Early Devonian - Late Silurian, 425-407mya

The Snowy River Volcanics unit is the underlying unit in the Buchan Valley region (Fig 4). It is an extrusive volcanic rock, erupted from violent, predominantly subaqueous composite volcanoes. The Volcanics consist of hard, erosion-resistant rhyolite with small black feldspar specs and small quartz crystals in a pink-tinged

Spring Creek Member: Early Devonian - Mid Devonian, 420-392 mya

The Spring Creek Member is a mixed layer stratigraphically between the Snowy River Volcanics and the Buchan Caves Limestone, representative of the transition from early lacrustine volcanism and sedimentation to marine sedimentation in the late Early Devonian. It features nonfossiliferous carbonate nodules of dark grey, secondary dolomite within a matrix of orange-yellow, coarse-grained, clastic but soft non-carbonate clay (Fig 7).

Ignimbrites consist of very soft, lightcoloured ash beds featuring small, rounded, elongated fiamme pits (Fig 6), porous pumice clasts that have undergone diagenic compaction. The light colour of the beds indicates high silica content, characteristic of high-energy stratovolcano eruptions. Subaqueous formation is demonstrated by graded bedding.

Figure 7 cutting.

Buchan Caves Limestone: Upper EarlyLower Middle Devonian, 407-387 mya

Buchan Caves Limestone lies directly above the Snowy River Volcanics and beneath the Pyramids Marl (Fig 8). The Buchan Caves Limestone group features a

dark grey, calcitic limestone. The Buchan Caves Limestone is relatively soft has a fine grain size without crystals. Buchan Caves Limestone at the Buchan Caves Reserves strikes north-south and has significant dip (Fig 9).

Figure 9. The strata of the Buchan Caves Limestone strikes North-South and has a significant dip. Strata feature fluctuating presence of brachiopods, some disarticulated and overturned

Fossils found in the Buchan Caves Limestone included rugose corals (Fig 10 & 11), brachiopods (Fig 12), particularly Chalcidophyllum and Spinella buchanensis, and gastropods. The lack of tabulate coral fossils distinguishes the earlier and deeper-deposited Buchan Caves Limestone from the more recently deposited McLarty Limestone and Rocky Camp Limestone units. Relative dating of its Acrospifier buchanensis brachiopods with the similar European Acrospirifer laevicosta indentifies the Buchan Caves Limestone as Middle Devonian.

Figure 10. A rugose coral fossil, likely Chalcidophyllum, in Buchan Caves Limestone. The fossil, approximately 6m in length, shows a segment of the radial-shaped rugose corals.

Figure 11. A small (approximately 1cm in diameter) rugose coral with fringing texture on its circumference.

These fossils are found predominantly in the middle and upper layers of the Buchan Caves Limestone. The intermittent fossiliferous and non-fossiliferous beds represent environmental changes. Layers with brachiopods upturned and dearticluated represent mass extinction from storms and other natural disasters.

The Buchan Caves Limestone in the Buchan Caves Reserve features abundant fossils, primarily brachiopods (Fig 13) and rugose corals, particularly Spinella buchanensis and the conical-shaped Chalcidophyllum respectively, as well as some gastropods and ostracods (Fig 14) preserved with calcite in mudstone. A fish head was also found preserved with calc

Dolomite:

Dolomite is a form of limestone where the calcium in the calcium carbonate has partially been replaced with magnesium through dissolution and reprecipitation. This often occurs in hypersaline lakes and marine settings.

Primary dolomitisation occurs in the same temporal and spatial setting as deposition while secondary dolomitisation occurs diagenically with perculation of permeable rock, through fractures and faultlines or via metamorphism with heated and pressurised limestone and magnesium-rich fluids.

Buchan Caves Limestone primary dolomite appears similar to sandstone with a yellow-brown tinge and with a slightly coarser grain size than non-dolomitised limestone. It also features large, white calcite crystals. There were no fossils seen in the primary dolomite, indicating a poor environment for marine biota, likely due to hypersalinity. Secondary dolomite appeared a dark grey colour with a leatherlike surface and deformation fractures (Fig 16).

17 & 18) with poor outcropping and some calcite veining. Fossils in the Marl’s limestone nodules included rugose corals (Fig 19), burrows, brachiopods (Fig 20) and pteropods Styliolina and Tentaculites

The general lack of fossils indicate a harsh environment for biota.

Figure

Pyramids Marl: Lower Middle Devonian, 393-387 mya

The Pyramids Marl lies stratigraphically between the Buchan Caves Limestone and the McLarty Limestone. It contains dark fossiliferous limestone nodules within a clay matrix, sometimes featuring compression folding. The soil of the Pyramids Marl appears reddish brown (Fig

McLarty Limestone: Lower Middle Devonian, 393-287 mya

The McLarty Limestone is a grey, soft and fossiliferous carbonate-rich limestone which lies between the Pyramids Marl and the Rocky Camp Limestone. The unit is very fine grained and has no crystals, although can feature calcite and quartzite veining. The McLarty Limestone also features stylolites from pressure deformation of soluable minerals in the

limestone (Fig 21). The unclear boundary between the McLarty and Rocky Camp Limestones indicate that the McLarty Limestone was still being cemetented and lithified at the time of Rocky Camp Limestone formation.

The McLarty Limestone is highly fossiliferous. Tabulate corals Syringopora Favosites are very common and distinguish the McLarty Limestone from the Buchan Caves Limestone (Fig 22) while its lack of Receptaculites distiguish it from the new Rocky Camp Limestone. Other fossils in the Limestone include rugose corals (Fig 23), brachiopods, crinoids and gastropods, which show a significant improvement of the intertidal and shallow marine environmental conditions since the deposition of the Pyrmaids Marl.

Rocky Camp Limestone: Middle Upper Devonian, 387-382 mya

Rocky Camp Limestone is a fine-grained, crystalless and bedless limestone ppearing stratigrpahically above the McLarty Limestone. It is fossiliferous and displays decent outcropping. Rocky Camp Limestone is very soft and has a high calcium carbonate content.

coral, likely Xystriphyllum, approximately 7cm.

Figure 22. A radial

Figure 23. A tabulate coral approximately 10cm. Note the structure of the coral is non-radial but rather with a flowing appearance.

Fossils identified in the Rocky Camp Limestone included brachiopods, nortiloids, crinoids (Fig 24), tabulate corals such as Favosites, gastropods and algae Receptaculites (Fig 25 and 26), which is characteristic only of Rocky Camp Limestone. Some brachiopod fossils were calcified, leaving a protruding texture on the limestone surface.

The abundance of well-preseved fossils, particularly of the fragile atromataporoids, and presence of photosynthesising algae Receptaculites (Fig 27) suggests a calm, shallow depositional environment, likely witha depth less than five meters. Stromactis voids cemented with calcite and marine cements suggest that the Rocky Camp Limestone outcrops were previously mudmounds with high biodiversity.

The lack of bedding and pale white colour indicate that sediment was continuously precipitated by marine biota during its formation and contains largely calcium carbonate with very little other organic contaminants. The Rocky Camp Limestone likely formed in a coastal lagoon or shallow, low-energy marine embayment. This reflects the location of

the shoreline in the middle Devonian period of the Buchan Valley.

Figure 27. 1-2cm crinoids and a 4cm diameter tabulate coral preserved in Rocky Camp Limestone.

Taravale Marl: Middle Devonian, 390382 mya

The Taravale Marl is a gravel-like marl with poor outcropping sitting stratigraphically above the McLarty Limestone and Rocky Camp Limestone. Taravale Marl observed in a roadside cutting (Fig 28) was very soft and could be crumbled manually while the limestone nodules could be scratched easily with a pick hammer. The Marl had cleavage which was parallel to the axis of its folds and vegetated brown soil at its surface.

The fossils found in Taravale Marl include abundant pteropods and brachiopods as well as rugose corals, tabulate coral and nautiloids. The Taravale Marl has a distinct lack of shallow-marine algae and an abundance of nautiloids and brachiopods, reflecting the deep marine depositional environment of the unit.

Cephalopod fossils in the Taravale Marl are helpful in determining the age of the unit. Gyroceratites was present during the upper Early and Middle Devonian while Lobobacrites was present in the Middle and lower Late Devonian. The presence of both these cephalopods in the unit date the Taravale Marl to the Middle Devonian.

Tertiary Gravel: Tertiary, 66-2.6 mya

The Tertiary Gravel is a nodulous mixture of limestone and pyrite deposited in the Tertiary period. The Gravel is likely a mix of Snowy River Volcanics, Buchan Caves Limestone and McLarty Limestone with a Pyramids Marl and Taravale Marl clay matrix. The deposit of Tertiary Gravel was likely the result of a landslide, which fractured limestone and pyrite rocks settling in what was the Murrindal River