Stanford d.school Yearbook 2021–2022

CREDITS

Editorial Team

Jennifer Brown, Laurie Moore, and Charlotte

Burgess–Auburn

Data Acquisition and Analysis

Megan Stariha

Creative Direction, Visual Design, and Typography

Daniel Frumhoff and June Shin

Typeface Design and Lettering

June Shin

Photography Patrick Beaudouin

Photo Retouching

Daniel Frumhoff and Patrick Beaudouin

Michael Hirshon

Michael Hirshon

Radostina Georgieva

David Alabo

Michael Hirshon

Rick Griffith

Reina Takahashi

Scott Teplin

Jori Tytus

Michael Hirshon and Khristopher “Squint”

Sandifer with Hope Meng

John E. Arnold

Lala Openi

Art Consultants

Scott Doorley

Nan Cao

Proofreader

Natasha Bach

Colophon

Ziza by Novo Typo

Signifier and The Future by Klim Type Foundry

Neue Haas Unica by Toshi Omagari

All of the work we do is a collective effort made possible by the d.school team, our teaching community, and the students we serve.

5 31 35 55 60 65 71 72 73–74 74–75

Illustrations

102–105 116–117

Stanford d.school Yearbook

2021–2022

Note: Use the QR code at the end of each article to learn more about the work coming out of the d.school.

Stanford’s Two New/ Old Design Degrees: Designing Design Education for the Future

Kelly Schmutte

Creativity in Research Scholars: Supporting PhD Students with Design Capabilities

Jonathan Feiber, Saara Khan, Lars Neustock, and Irene Alisjahbana

COVID Signs: Returning to the d.school Space

Olga Saadi and Hannah Joy Root

Reimagining Campus Life

Glenn Fajardo

Stepping into the Bay: Extreme Immersion

Manasa Yeturu

The Moral Imperative of Teaching Every Student Tech Ethics

Karen Ingram and Megan Stariha

Don’t Throw Out the Joy: Creative Direction at the d.school

Scott Doorley

Coffee with Courtlandt: JEDI Training at the d.school

Courtlandt Butts

Designing Bridges: Building Belonging and Community at the d.school

Milan Drake

Teach & Learn Shaping Curriculum and Community in a Changing World

14

22 26 28 34 36 42 7

8

20

Contents

REP Magazine

Ariam Mogos

Creative Acts for Curious People: Creating a Collection that Celebrates the d.school

Sarah Stein Greenberg

Introducing the d.school Guides: Creative Ways of Cultivating Resourcefulness and Inventiveness

Scott Doorley and Charlotte

Burgess Auburn

Everything Is a Collaboration: Books Edition

Scott Doorley

Faces of Change: Work from the University Innovation Fellows

Leticia Britos Cavagnaro, Humera Fasihuddin, Lupe Makasyuk, Laurie Moore, and Ghanashyam Shankar

Changing the Conversation: About School Safety sam seidel and Barry Svigals

Design in Action: A Case Study from Designing for Social Systems

Thomas Both, Nadia Roumani, and Susie Chang

Masters of Creativity: Connecting Alumni and Worldwide Learners with a Creative Community

Jeremy Utley

Building Future Foundations

Scott Doorley, Leticia Britos

Cavagnaro, Lisa Kay Solomon

Becoming Good Ancestors: The Urgency of Long-Term Thinking

Lisa Kay Solomon

Visions of the Future: A Radical Invitation toward Shaping Collective Futures for Education and Beyond

Ariel Raz, Louie Montoya, Lisa Kay Solomon, and Laura McBain

Positive Deviance For Educators: Using the Brilliance of Our Communities to Find Existing Solutions to Persistent Problems

Devon Young, Jessica Brown, Marc Chun, Peter Worth

Get Down with the Mission: The K12 Lab’s New Learning Deck on Taking Action toward Racial Justice

Jessica Brown, Louie Montoya, and sam seidel

Data

2021–2022 d.school

Contributors

Impact & Access Explore & Imagine Sharing Design Ideas and Tools Building the Future Foundations of Design 53 99

54 58 62 66 76 80 88 92 100 106 112 120 126 134 140

Welcome to a new type of d.school yearbook

By Sarah Stein Greenberg

First initiated by our Academic Director Carissa Carter, in the past five years our yearbook has chronicled the developments and ideas coming out of our academic program. The document you have here represents a transition: as our academic team takes on greater responsibilities for our new degree programs (see page 6), we are starting to publish an annual roundup that showcases learning, innovation, and impact from across the entire d.school.

Introduction Introduction Introduction

4 INTRODUCTION

Introduction Introduction Introduction

he d.school is navigating a time of tremendous transition, both in the world as a whole, and right here on campus. We are aiming to fuse the rigor and depth of our new degree programs with the interdisciplinary vitality of our university-wide course offerings. We’re reimagining our models for spreading design and creating impact alongside professional learners, and we’re developing new approaches for design to meet the most complex and rapidly emerging challenges of our time. This work will unfold in the coming years.

In addition to sharing highlights from classes and our work in supporting a vibrant, interdisciplinary, inclusive

examples throughout this collection that touch on our projects with K12 educators and young people, social sector leaders, and with students and faculty in higher education from around the world. You’ll hear from our teams who have been focused on producing innovative tools, books, and spreading design methods broadly, and even explore some hints and glimmers of where we see design itself heading.

Whatever and however you design, whether you’re interested in learning or teaching, looking for new tools or inspiration, a prolific contributor to our shared work already, or just hoping to get to know the d.school as a whole a little better, I hope you encounter many ideas and resources in this collection that meet you right where you are.

d.SCHOOL YEARBOOK 2021 2022 5

Learn Learn & & & Teach

As campus comes back to life with renewed vitality, our approach to academics embraces the reality that our context is our curriculum. As you’ll read in this section, d.school faculty and students have been designing new ways to navigate a hybrid world, inspiring students from all backgrounds to engage with emerging technology, and interweaving cutting edge research across disciplines with creative abilities. Not only does context deeply shape what and how we teach, so too does community. Read on to see how we are designing

bridges to support students who don’t (yet) feel at home at the d.school, making art-inspired reminders that cue COVID –safe behaviors throughout our space, and crafting a visual language across the work we produce that is a pluralistic expression of joy and hope for the future. Up first: how we are reimagining Stanford’s design degrees to help future students adapt and thrive in a changing world.

→ →

Shaping Curriculum and Community in a Changing World d.SCHOOL YEARBOOK 2021 2022

Stanford’s Two New/Old Design Degrees

Stanford’s Two New/Old Design

Stanford’s ew/Old Design Degrees

By Kelly Schmutte Designing Design Education for the Future

TEACH & LEARN 8

Product Design and Design

tarting on September 1, 2022, Stanford’s longstanding Product Design (undergraduate) and Design Impact (graduate) degree programs moved under the umbrella of the d.school as interdisciplinary programs (IDPs). An IDP is a degree program at Stanford that doesn’t fit neatly within any one department: Human Biology and Symbolic Systems are two of the best known (and loved) IDPs.

Moving these two programs to the d.school opens up an opportunity to build a design program for the future.

And we’ve had a head start. Back in 2013, the d.school undertook a massive project around the future of higher education. We explored questions like:

How can we amplify the ways that learning is transformed by off-campus experiences? How can students move through education at their own unique pace? How can declaring a mission help students put their focus on purpose?

We’re beginning to infuse what we learned through the Stanford 2025 project to help us restructure and reimagine these programs in light of the challenges facing our world now and in the years to come. By combining the design depth and wisdom that’s evolved over decades with the radical multi-interdisciplinary approach of the d.school, design at

Stanford will continue to evolve in a powerful new direction that meets the needs and supports the goals of current and future design students.

Although we have begun imagining what’s possible, our work to explore and shape our future approach to design education has only just begun.

Design Degrees at Stanford: A History of Stretching Across Disciplines

Since they were created in the 1960s, Stanford’s Product Design degrees have been special programs. Professor John E. Arnold came to Stanford from MIT in 1958 and brought with him the idea that design engineering could be creative. It was a radical concept.

The interdisciplinary DNA of the product design programs was born, merging art, science, and engineering, and rooting them in human values. Professors Bob McKim (Engineering) and Matt Kahn (Art) built upon John’s idea to create the Product Design major and the graduate–level Joint Program in Design (JPD), both of which emphasized a human centered, visual thinking, design approach. Rolf Faste and David Kelley integrated even more professional design perspectives, and championed interdisciplinary collaboration across Stanford’s campus. Along the way, Stanford’s Product Realization Lab has been an invaluable partner in helping students bring form to their ideas.

1 2 3 d.SCHOOL YEARBOOK 2021 2022 9

Stanford’s

Impact degree programs have moved to the d.school–signaling a chance to offer a type of education that doesn’t yet exist.

This unique beginning and evolution of the design programs attracted a quirky “I don’t fit in a box” type of student. For a long time, there wasn’t a comparable program at other schools; it took a while for others to catch on to this unique blend of engineering and art. At Stanford, the undergraduate program in particular has grown in popularity over the years. The students who graduate from these programs feel a strong bond, often sharing similar and profoundly transformative experiences.

Throughout this history, one thing has remained constant: Design as a field, a practice, and a way to create impact is continuing to change and evolve. The IDP proposal for the new degrees articulates it as follows: “Designers make things with materials. Historically, these materials have only included media like metal and wood, then plastic and pixels. This is no longer the case. Today’s and tomorrow’s materials of making are complex, interconnected, and unpredictable. They are algorithms and blockchains, synthesized

organisms and DNA sequences, massive data sets and social networks: mischievous materials that continue to morph after they are made or molded. We’ve entered an era when it’s near impossible to predict the impact of our creations because they change us as quickly as we make them. Put something new in the world, and it will ripple. It will grow, heal, evolve, and maybe even destroy. Possibilities will be magnified. Mistakes will be amplified. This ambiguous ecosystem for creative work is our future, and we must prepare Stanford students to be leaders in it.”

Our overriding goal: to amplify the best aspects of the current programs, and bring freshness and evolution where it’s needed. It is critical to honor the legacy of these successful programs, while stewarding them in a direction that stays true to the trailblazing values of the program’s founders and their desire to reimagine what’s possible within design education. The result will be a BS Design and an MS Design, eventually replacing the Product Design major for undergraduates, and the Design Impact degree for masters students.

Four Pillars Guiding the Evolution of Design at Stanford

In shaping these two new degree programs, we were led by four guiding and interconnected pillars, which were articulated by Carissa Carter, our Academic Director. Stanford design students will be equipped with the following knowledge, abilities, and perspectives:

TEACH & LEARN 10

1 2 3 4

Be ready to make in any medium. The knowledge and ability to prototype and make across a wide range of mediums, existing and emerging. Students can contextualize and apply design principles across disciplinary domains. They have broad material literacy and can build and analyze in many mediums, like physical products, code, policy, and emerging technologies.

Develop the care and responsibility to be leading stewards of the planet, all people, and the data we generate. Students know how to work slow and fast, with appreciation and respect for varying time scales of change. They learn from and with other humans and the environment. They realize the importance of equity, ethics, and implications.

Use quirky creativity to produce new-to-the-world ideas. Students see trends, spot new opportunities, and have the courage to boldly try something untested. They relish disciplinary intersections, embrace ambiguity, and can collaborate and communicate with a diverse group of people. They can set visions and the paths to them.

Learn how to learn and have the flexibility of adaptive learners. Students can synthesize and integrate ideas and experiences from across the different aspects of their Stanford education and beyond. They can articulate their own capacity and needs as adaptive learners when tackling open-ended problems. As emerging leaders, they can establish the conditions for others’ creativity to emerge.

In addition to these four pillars, we leaned heavily on the collective insights and wisdom from those who’ve taught in the PD program over the years in order to shape the two programs. As a result, the undergrad and grad degree programs are becoming even more interdisciplinary.

PD has always prided itself on bringing disparate fields together (ME, Art, Psych, CS). Now students will have the opportunity to take classes in even more disciplines. This will be reflected more strongly in our leadership and teaching community. We’ll be forging new faculty relationships across departments.

Here are a few exciting ideas that characterize the new design programs:

Design 1: A new introductory class. Currently, students don’t really get the opportunity to get into the “meat” of PD until their junior year (with a few exceptions). The development of a new introductory course, Design 1, will give degree exposure to students in their first year at Stanford. It is meant to attract students to the major, particularly those that might not have considered an engineering opportunity, and also help them start to calibrate where they’d want to specialize.

A deeper integration of ethics and implications. Students are challenging instructors with increasing care and concern about the impact of their work in the world. Ethics and implications work will lead off and be integrated throughout the design fundamentals sequence.

Methods depths: choosing what making abilities you want to specialize in. Product Design has always been more of a generalist degree, although student interests have been broadening over time (physical PD, UI/UX, design research, entrepreneurship, social impact, and so on). Students will now get to gain professional fluency and elevate their skills and abilities in one of three selected methods focus areas (Physical Design and Manufacturing/ AI and Digital User Experience/ Human Behavior and Multi–stakeholder Research). d.SCHOOL YEARBOOK 2021 2022 11

Domain focus areas: deeply understanding a context for impact. Students will also choose a Domain Focus Area to take a few classes in. This should be an area of interest to them, like a domain or industry, where they’d be excited to apply their design abilities in context, and where we believe human-centered design could add real value. Students will take three courses: one foundational, one applied, and one that examines future horizons. We will begin with these five focus areas:

Climate and Environment

Living Matter

Global Development and Poverty

Healthcare and Health Technology

Innovation

Oceans

We will plan to add others and/or modify these depending on student response. We’re interested in allowing students to propose their own domain area as well as plan to offer an honors option.

Capstone: the culmination of method depth x domain focus. Currently, there’s one Capstone option for everyone, and students often rely on their own self-taught skills and developed interests (outside of PD) to inform how they choose a Capstone project. Within the new IDP, students will choose from several flavors of Capstone experiences, and will scope and execute design work that integrates their methods and domain focus areas.

• • • • • •

Creativity in

Supporting PhD Students with Design Capabilities

Creativity in Scholars TEACH & LEARN

14

Creativity in Research Scholars

By Jonathan Feiber, Saara Khan, Lars Neustock, and Irene Alisjahbana

Creativity

Research Scholars

Creativity Scholars

tudents committed for two quarters to explore a new project at the intersection of their PhD research and growing design abilities. The first quarter focused on applying learning design to various research mindsets and the second quarter focused on pursuing their individual and paired projects with these leveraged intersection points.

The way the students were able to intersect their learnings was beyond what we could have envisioned. Each project the students pursued represented a new take on their PhD work and culminated in something novel and unique. Here are some snapshots of their projects.

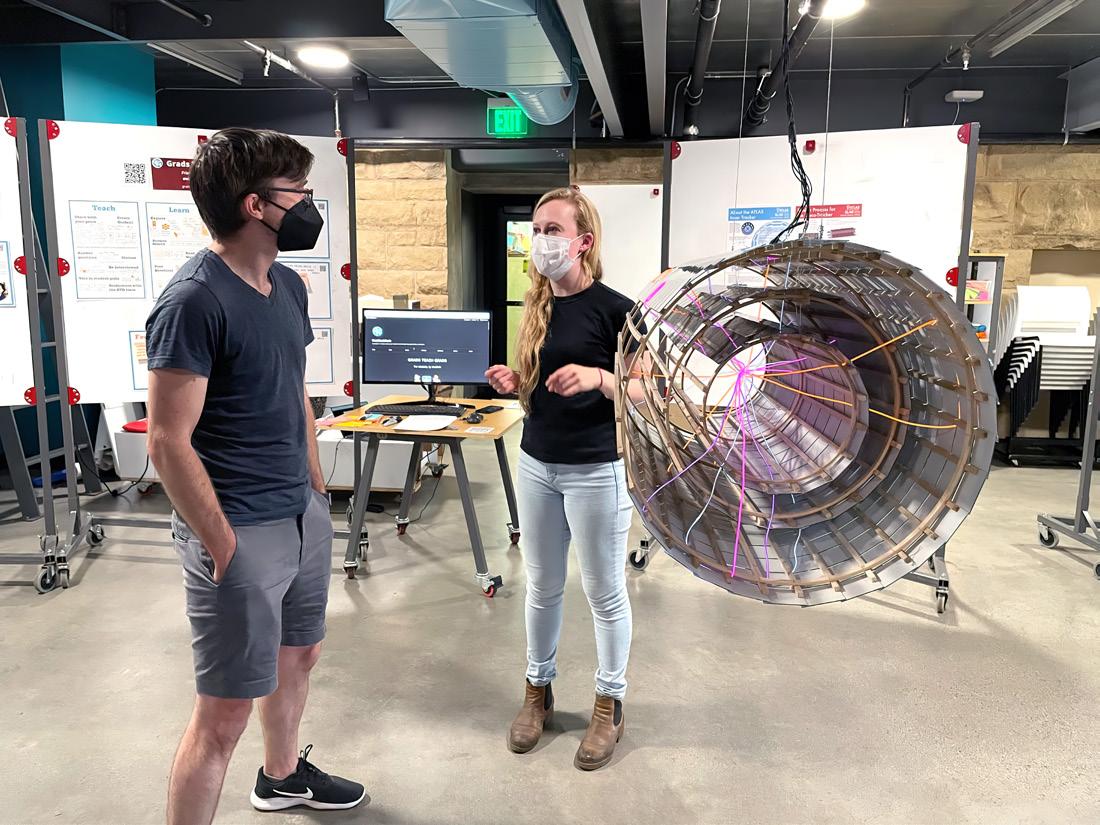

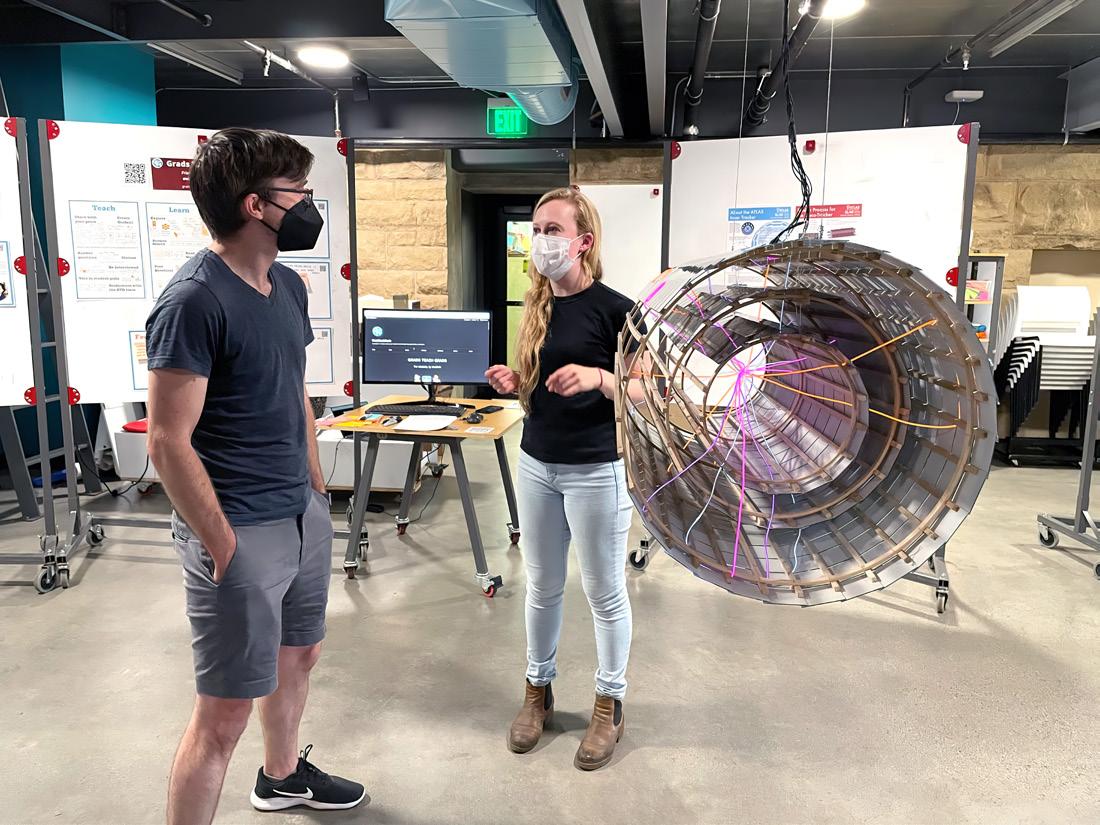

The Discotracker

Jannicke Pearkes (Physics)

Jannicke’s PhD work is focused on experiments via the Large Hadron Collider, a 27 km long particle accelerator sitting between Switzerland and France. She studies the Higgs boson—a particle first

discovered in 2012. By analyzing data from trillions of proton–proton collisions, she looks for collisions where two Higgs bosons are produced at once. Jannicke’s goal was to help create a physical understanding of how the Large Hadron Collider works, by creating a realistic representation on a smaller scale of the particle accelerator. She built (using mirrors, glass, wood, LEDs) an artistic representation of this particle accelerator, which will be on display at the sixtieth anniversary of SLAC and remain on permanent display afterward.

She says, "The Discotracker is an artistic interpretation of a particle detector being built by my research group at SLAC. Every 25 ns, particles collide in the center and produce new particles, which travel outward through the detector. Once constructed, the detector will be flown to Switzerland where it will be installed in the heart of the ATLAS experiment at the Large Hadron Collider. After installation the detector is incredibly hard to access. This project aims to bring the beauty of tracking detectors to a wider audience.”

Creativity

d.SCHOOL YEARBOOK 2021 2022 15

Stanford’s PhD students are often hungry for the tools to take their ideas to the next level. We equip PhD students with design research mindsets to enable the students to explore their research in creative new ways.

TEACH & LEARN 16

Gravity Sandbox

Jared Blanchard (Aerospace Engineering)

Jared studies orbital dynamics, specifically the three-body problem, and wanted to find a medium to teach orbital dynamics in a compelling and engaging way. After exploring and brainstorming several different methods, Jared found VR to be this medium. During the class, Jared taught himself Unity and prototyped several different VR apps to bring his research into the virtual world. He refined his Unity skills, UX skills, and created Gravity Sandbox (which is available for download on the VR App store).

He says, “My project was a VR experience designed to build orbital mechanics intuition in students. I had been wanting to make something in VR for quite a while, and this class provided me the perfect opportunity to do so. Following YouTube tutorials on how to use Unity, I created Gravity Sandbox and uploaded it to the Oculus store. Users can throw spacecraft into orbit around the Earth, create their own asteroid belt, and interact with the classical orbital elements in VR.”

Emotive Design

Tara Srirangarajan (Psychology)

Tara’s PhD work combines insights from behavioral experiments and neuroimaging to understand the dynamic neural substrates of emotion. Despite great advances in our understanding of sensory and motor neural processes, it remains a mystery how the nervous system gives rise to our subjective experiences. Tara sought to tackle this by exploring the intersection of emotional meaning and visual shapes, colors, and movements of objects. Her exploration led her to create a mapping of Emotive Designs that she correlated back to movement, shape, color, and texture.

She says, “I explored how different visual attributes like shape, color, and movement can be effective tools in conveying emotional meaning. These principles have been applied across diverse domains such as graphic design, marketing, animation, and film. I began by analyzing what specific features are most effective in evoking affective responses, based on empirical work in visual neuroscience, cognitive science, and psychology. Merging these lines of thought and finding creative intersections between them was a wonderful opportunity to delve deeper into the interplay between emotion and aesthetics.”

GradsTeachGrads

Nandita Bhaskhar (Electrical Engineering) & Tess Hegarty (Civil and Environmental Engineering)

Nandita’s PhD is on Machine Learning for Healthcare to aid in data acquisition and processing, while Tess’s research is on Climate Change and how it affects marginalized people worldwide. The two of them teamed up to tackle an issue that they saw outside of their core thesis work, but is deeply rooted in their experience as graduate students. They designed a new way for graduate students to learn from, teach, and mentor each other, and to make sense of the many resources that Stanford provides. GradsTeachGrads is a collaborative wiki by and for Stanford grad students, housing a collection of grad student experiences and advice and a curated database of resources from across campus and beyond.

Nandita says, “Grad school can tend to get lonely and isolating as we progress further in our research. I strongly believe that it doesn't have to be. While each of us have our unique paths, there are experiences that everyone goes through. Through GradsTeachGrads, we can share and learn from each other.”

d.SCHOOL YEARBOOK 2021 2022 17

Tess says, “I think we all have something to teach and we all have something to learn from one another.

I hope GradsTeachGrads helps increase the feeling that we are all on the same team in working on research oriented toward making the world a better place, and so it makes sense for us all to ask for and offer help.”

COVID Signs COVID Signs COVID Signs

Returning to the d.school Space

By Olga Saadi and Hannah Joy Root

In anticipation of staff and students returning to campus, the d.school’s Community Manager, Hannah Joy Root, alongside Design Impact masters student, Olga Saadi, designed a series of COVID safety signs to be used in the d.school’s space.

These kinetic, light–utilizing, colorful art pieces aren’t your typical COVID protocol posters. While these signs promote d.school rules (wear a mask, wash your hands) and values (practice empathy), they also act as an art installation. As the light changes throughout the day, so does the art. The transparent sheets adapt and absorb light, so as the sun and studio lights flicker and change in intensity, the art follows.

TEACH

& LEARN

Reimagining Campus Reimagining Campus Reimagining Campus

By Glenn Fajardo

As we returned to campus in Fall 2021, after a year and a half of emergency remote teaching, many of us had ambivalent feelings. We felt joy when we saw everyone face-to-face again. And we felt confusion when faced with campus life that clearly wasn’t the same as it was in March 2020.

TEACH & LEARN 22

Reimagining Campus Life Reimagining Campus Life Reimagining Campus Life

he root word for confusion is the Latin confusionem, which means “a mingling, mixing, blending.” We can think of “confusion” as when we feel mixed up in a way that doesn’t yet make sense to us–and that’s how many of us, educators and students alike, felt when we returned to campus amid the pandemic.

Through the confusion, we could sense that we’re not going back to the way things were. We’re going forward to a new hybrid reality, where in-person and virtual mix.

Design is uniquely suited to help us navigate this new world. Design’s mindsets and methods can help us

create human interactions that feel more human in this confusingly unfamiliar new reality. Design can help us make “mixed” feel less “mixed up.”

In Reimagining Campus Life: Designing Hybrid Experiences, our students prototyped ways to make the hybrid campus experience feel more human.

A seemingly simple viewpoint shift was the turning point. Once we stopped pitting virtual against in–person and instead noticed and distilled the strength of each, the floodgates of possibilities opened up. Our students prototyped hybrid interactions that could be more inclusive, connected, adaptive, and resilient.

d.SCHOOL YEARBOOK 2021 2022 23

Here are a few of their reflections:

Alex Liang

I never thought I would be able to combine space and senses with hybrid and virtual settings. To me that’s something super new.

What if hybrid becomes the norm in the future?

Candice Kim

I never thought I would be able to really parse through the magic of in–person interactions and be able to really think about how we recreate that magic or the heart of in-person interactions in different contexts through virtual interactions. Instead of thinking about recreating the in-person experience, I’ve started looking at virtual interactions as capturing the heart or the energy or the magic of what the in–person experience is. We can then bring that

TEACH & LEARN 24

to life through different media in the best way that media has to offer, which might not actually be the in–person experience.

Michaela Gordon

I never thought that you’d be able to form such close relationships through hybrid settings. I always thought in–person would be the best way to go, but this has taught me so much about the different capabilities of these hybrid environments.

What if we can spread this knowledge to a wider audience?

Charlie Perry

I never thought I’d be able to create a prototype to solve a pretty major problem on such short notice. There’s something to be said about deadlines, and short periods of time, and bursts of brainstorming that I didn't really realize I had until this class.

I’m wondering how to use the benefits of technology to meet the needs of people in reality rather than having something that’s made and have people adjust to it. Instead of ‘how do we adjust to technology’ it is ‘how do we make technology adjust to what people need.’ What if we apply this thinking of adjusting to how people really are for all aspects of our lives, not just technology but anything we’re designing?

Adel Rahman

I never really thought that you’d be able to capture the essential magic of a lot of these things that seem so tied to being in-person. I didn’t realize you could capture aspects of their magic in situations where we’re not necessarily together.

I’m wondering if I can actually make use of any of these ideas to more meaningfully keep in contact with friends who don’t live in the Bay without hopping on a plane all the time.

d.SCHOOL YEARBOOK 2021 2022

the Bay the Bay Stepping into Stepping into Stepping into

By Manasa Yeturu

Extreme Immersion

xtreme student Nabeel Momin reflects, “One of the biggest nights for me was immersion when we had artists come in and talk about some of the socioeconomic discrepancies that have happened right here in Palo Alto. Being new to this area many people in the room never would have known the history here. It opens your eyes to a new part of what it means to be at Stanford, and the privilege that we have to make a difference.”

Curated by Manasa Yeturu, curriculum lead for Design for Extreme Affordability, Stepping into the Bay was a curated class experience set up as an immersive evening where students literally stepped into the sociopolitical history of the Bay Area via Studio 2 at the d.school, which was transformed into an art walkway filled with nods to the deep history of the Bay Area. The evening consisted of dialogue and performances by three spoken word artists—Labika Pittman, Dr. Aseem Hassan Loggins, Kevin Madrigal—Bay Area Natives from East Palo Alto, South San Francisco, and Richmond. Prior to the start of the evening, students had just received their Extreme project teams and challenges. Stepping into the Bay was meant to serve as a powerful reminder of the importance of understanding

the culture, context, and history of a location and the problem spaces they would be working before engaging with and stepping into communities.

Rozy Estaugh, an Electrical Engineering student, shared, “In the spoken word night, the takeaway was to be ‘really real.’ Often at Stanford, thinking is at a higher level, we do not often center lived experience in a real practical way. The artists emphasized why it was important to be humble and real in terms of building relationships. Stanford is a bubble… I started to see my position as an outsider with a lot to learn. It was incredibly powerful to break outside the bubble as we began this work.”

The immersion night was a launch into the first phase of work for the Extreme teams: to create a map of the policies, history, people, and initiatives that had influenced and shaped their challenge statements. They used these maps to host their first co-design session with their non–profit partners—showing rather than telling them that they were keen to understand and build on community initiatives that had come before them. As Nabeel and Rozy shared, immersion and a sociopolitical evening rooted in real talk allowed them to move forward from a place of humility, respect, and care as they tackled challenging issues across the Bay Area.

The Design for Extreme Affordability group curated an immersion night that used storytelling as a bridge to connect students and the community–setting a foundation for real talk and empathy work.

d.SCHOOL YEARBOOK 2021 2022 27

The Moral Imperative Imperative The Moral Imperative

By Karen Ingram and Megan Stariha

TEACH & LEARN

28

of Teaching Every of Teaching Every of Teaching Student Tech Ethics Student Tech Ethics Student Tech Ethics

What do you think about synthetic biology? What about altering a baby’s genes? You likely had a stronger reaction to the second question. But do you know how the two are related?

merging technologies like synthetic biology are all around us and at varying degrees of development and dissemination. Their applications are being tested, products are being built, data is being collected. But by and for whom?

Some instances of scientists or technologists going too far or misusing technology reach the mainstream media and make headlines. That’s probably why you’ve heard of gene-edited “CRISPR babies.” These splashy and sometimes scary situations are more the exception, but illustrate an important point: We should all be paying more attention. That includes students, who are the technologists and ethicists of tomorrow.

Yet while these are important topics to be familiar with, only a handful of students will go into fields like synthetic biology. The real question is: How do we increase access and participation in the creation of emerging technology so that it represents and works for all of us? After all, when it comes to emerging technology, equity in terms of factors like gender and race is crucial.

Schools can start laying the groundwork now. Educators can facilitate conversations around ethics in technology with students so that these technologies develop equitably. In fact, educators have a special role to play in fostering these discussions for students, and design can be the methodology.

Design focuses on identifying challenges and rapidly coming up with solutions and ideas to address them. Using design as a framework allows for greater participation by identifying multiple entry points, circumventing technical jargon, and creating a sense of participation and agency in evolving technology.

Start with the End

For many of us, the term “synthetic biology” is less captivating than “gene–edited babies,” and there’s a reason. The end products of a given technology are more accessible and relevant than any introduction to the technology itself. Centering the conversation on the tech invites participation from enthusiasts, evangelists, and skeptics, sure. But it leaves out huge swaths of the population—those who are indifferent, or apathetic, or don’t feel like the tech is relevant to them.

Imperative

Teaching Ethics

d.SCHOOL YEARBOOK 2021 2022 29

Imperative Imperative Teaching Teaching

Ethics Ethics

Young people—our students— are no different. They occupy the same spaces along the spectrum of engagement when it comes to emerging technologies. Some will be fascinated by the topic; others will evince only a passing interest at first. But we can engage students in the creation of tech by starting with implications.

Centering learning on the first–, second–, third–order implications puts the student directly into the design challenge. Once they’re invested in making an impact or creating change about an issue they care about, they can navigate the layers of opportunity within the space to determine their role. Are they:

Interested in crafting the system governing privacy–protection policy? Building anti-racist datasets? Making novel products with their perspective in mind?

Regardless of where students want to effect change, a layered understanding of the technology and potential implications shows there is a place for everyone in creating well-rounded solutions.

When we lead with implications, students learn what they need to know to form an opinion. Not all students need to become specialists in code, gene sequencing, or logic boards, but it is critical that all students consider the impact of what they’re creating on humans and the broader world.

By accessing a technology through a human-centered lens, we bypass exclusionary jargon and high-tech barriers to entry and have students ask the essential questions:

Is this the best use of the technology? Is it appropriate use of the tech or are there other options? What is gained? What is lost?

Like It or Not, You’re Building Emerging Tech

As new technologies evolve, the range of people impacted expands, whether we are aware of it or not. It’s a fallacy that ambivalence or rejection of technology means neutrality. There is no neutral space to occupy. There is no black and white, but there is a lot of gray area, and that offers room to consider potential impacts, change course and charter new pathways.

All around emerging technology, there is a sense of inevitability. But there is also a sense of helplessness, frustrated resignation, or even panic that tech is something that “just happens” to people. But even if these technologies are inevitable, how they evolve is not. That’s where schools come in, as they help instill in students a sense of agency. Since we’re all participating—whether we like it or not—let’s build technology that serves all of us.

Find the Part You Want to Play

When we use design, we can more easily discuss applications that are about humans and stakeholders in the system, rather than just the tech itself. Design helps you consider why your perspective is important and necessary, and why the perspective of others is just as critical.

Creating with technology doesn’t have to be about coding or gene editing. It can be about coming up with implications to see the potential impacts. It can be about building new systems to create equitable access, collecting new sources of data to represent more users and participants, creating more inclusive experiences, and so much more. In other words, it’s not about the code; it’s about what the code can do.

TEACH & LEARN • • • • • • • 30

It is imperative that we help learners find their agency and the opportunities to participate in the systems in which they exist. The next generation may not call into question whether or not they will participate, but as they are a more diverse, educated, change-tolerant group than those that preceded them, design offers a way to actively create what comes next.

Once we have a starting point, we can start to uncover how we got here and how we can get to where we’d like to go, given what we are experiencing now.

Emerging technology is just that: emerging. Its existence may be inevitable, but we have the agency to determine the impact it has. Design gives us a map to find our own agency in the landscape. Once we’re engaged, we can figure out what to create and what type of impact we, as designers, could initiate.

Implications Systems Experience Products Technologies Data d.SCHOOL YEARBOOK 2021 2022

Since we’re all participating, whether we like it or not, let’s build technology that serves all of us.

By Scott Doorley

By Scott Doorley

Don’t Throw Out the Joy

Don’t Out the Joy

Creative Direction at the d.school

Don’t Throw Out the Joy

There’s a euphemism that has always bothered me, mostly because it’s so ludicrously unlikely: Don’t throw the baby out with the bathwater

.

TEACH & LEARN 34

ack in the day, I bathed my kids in a little tub that we plopped in our kitchen sink. But there is just no possible way I’d accidentally toss out my baby when I dumped out the bathwater. The tub was just too damn unwieldy to gloss over the baby sitting amongst the cloudy liquid. But I get it. And to be clear, I understand the phrase isn’t meant literally. Still, it's just too implausible to be a useful metaphor.

Nevertheless, it sparked a new metaphor for me. I’d like to propose a derivative phrase, one that is far less drastic, but way more likely (if a bit less snappy): Don’t throw the joy out in the name of consistency.

When people think of branding, they immediately think of consistency. By now, we’ve all drunk the juice. That’s not to say consistency isn't important. Consistency is important. It helps an audience find their way. It lessens the cognitive load and makes it easier to connect. But consistency lives in the realm of style. The d.school lives in the realm of personality. Of course, consistency and personality can go hand-in-hand—I’m creating a false dichotomy for effect. But if perchance, it must come down to it, I'll take exuberance over style any day.

Maybe what I’m talking about is a kind of branding devoted to accommodating the multitudes of what we really are— not one monolithic, singular notion, but the radiant mixture of many. Maybe we can call it mixed branding or branditudes! (Or maybe not—I’m open to ideas.) Either way, please don’t throw the joy out in the name of consistency.

And let’s just say it: this year (and then some) has brought with it a lot of strife. No doubt. But I have also seen so much joy. Not perfectly consistent, but full of exuberance, personality, and hope.

I've seen joy spread across the pages of REP magazine. I've seen triumph in the display of the Black Panther photo exhibit. I've seen spirit in the class banners and cards that graced our most recent pitch night and the delicious posters for make/ shift events. I’ve seen optimism and conviction in the movements that animate the illustrations of the K12’s Get Down with the Mission deck. I've seen silly hearts smiling behind the reverse confetti explosions on our Instagram account. I've seen personality—with an emphasis on the personal—in each and every book we published. I've seen giggles in the bright colors looping behind the MOC speaker’s headshots. I've seen care and wonder grace the murals on our bathroom walls. And I've seen magic in the moving light that dances across the home–spun Future(s) exhibit now at the Smithsonian.

d.SCHOOL YEARBOOK 2021 2022 35

Lots of joy. Some consistency. No bathwater. The d.school!

began my JEDI work at the d.school with the intent of adding to and possibly augmenting the multiple energies around equity currently practiced by the d.school. The approach I used is a prototype that encourages me, as the contractor, to get to know the people in the organization before I engage in a d.school-wide training. What this does is that it allows me to gain a better understanding of the wonderings, desires, and needs of the folks in the organization as well as the unique nuances that shape the overall movement of the culture to be considered when engaged in equity leadership experiences. I learned from the folks with whom I engaged and, hopefully, they learned something from me.

This year I had the wonderful opportunity to connect with the d.school, a group of brilliant minds and caring souls, for the purposes of engaging in Justice Equity Diversity and Inclusion ( JEDI) work through my firm LifeGuardian Worldwide.

TEACH & LEARN 36

Courtlandt Courtlandt Courtlandt

Courtlandt Courtlandt Courtlandt

I was able to connect with the d.school through a few different recurring opportunities including, “Coffee with Courtlandt,” one-on-one coaching sessions, and design meetings with some of the school's leadership.

The Coffee with Courtlandt sessions were once–a–month, forty–five–minute jam sessions. Anywhere from two to eighteen folks would join to take a deeper dive into the core of our humanity by exploring an equity–related topic inspired by a song. In this “building space” we explored and grappled with various ways in which some of our social norms impede growth and transformation within our human condition.

The one-on-one sessions were up to sixty minutes and were scheduled through a Calendly link shared with the entire d.school team. I personally grew with each engagement of these sessions, which were intended for

JEDI Training at the d.school

By Courtlandt Butts

coaching specifically around equity, but which also touched on how to navigate around COVID, research projects, and student impact.

The design meetings included considerations of how we move through school–wide equity training experiences in ways that are aligned with the current efforts of the d.school. As one of the co–designers, I always left with a feeling of fruitful possibility and hopefulness.

Although it was not school–wide, I did have an opportunity to lead sessions with the awesome coaches in the Designing for Social Systems program, as well as the University Innovation Fellows program. In both spaces we explored Knowledge of Self and the Shadow Aspects of the Self. Understanding this nature of our being is the precursor to understanding the implicit biases one has around one’s self and others.

d.SCHOOL YEARBOOK 2021 2022 37

In the way of key insights and hopeful takeaways, I would often tell folks, “You are the best design for the transformation needed in the world.”

TEACH & LEARN 40

Once we learn of an innovative approach toward a goal, we need to make the effort to commit to continual and sustainable practice for lasting change to come about. For example, the tools that I introduce in a learning session are not just for the training space. They are for home,

community, and for all time, until that work is internalized as part of one’s being. This work we do around equity is rarely about “us vs. them”; it’s about all of us coming together to interrupt institutional norms that do not serve our collective humanity.

When we transform ourselves we transform the universe. Practice is key. There is no getting around it.

d.SCHOOL YEARBOOK 2021 2022

Bridges Bridges Bridges Designing Designing Designing

Designing Bridges is the d.school’s effort to cultivate more inclusive environments for marginalized instructors and students. Our focus has been on building brave spaces where authentic community and belonging can flourish. It has been my honor to lead this journey for the d.school through storytelling, reflecting, and listening with others.

TEACH & LEARN 42

Designing Designing Designing

Bridges Bridges Bridges

Building Belonging and Community at the d.school

By Milan Drake

By Milan Drake

uthentic community–building requires that we have courageous conversations with both potential instructors and the students who are interested in the d.school and who are seeking encouragement to be included in the community.

When I made it a goal to have more honest and transparent conversations about community, design, race, racism, mental health, and more with the broader Stanford community (faculty and students on campus, those familiar with the d.school, and those outside of the d.school/ design community) a recurring theme emerged. Students overwhelmingly

d.SCHOOL YEARBOOK 2021 2022 43

TEACH & LEARN 44

conveyed a sense of not belonging in the world of design; of not feeling welcome to learn what design is or what designers do; and of diminishing their own potential to work in design due to their life experience, gender, color of their skin, college major, and/or geographical location.

It was through these conversations that I knew something had to change about how I was approaching and defining community-building. In that moment of clarity I went from designing SAFE SPACES to designing BRAVE SPACES

d.SCHOOL YEARBOOK 2021 2022 45

I asked students, I asked faculty, I asked my network, I asked anyone who would listen: “What kind of community do you actually want?” “What truly matters to you?”

“What is community to you?”

Then I asked myself, “Am I interested in gathering a bunch of people into a bunch of rooms who do not respect each other and/or are not empathetic to how each person arrived in the room, or am I about designing deep connections that will require looking and listening to people’s stories and looking in the mirror at our own stories?”

his very valuable, external and internal insight—along with being in tune with happenings on campus and the world around us— was the glue to every thought and action applied to building community throughout this academic year.

The idea and process of Designing Bridges focuses on our community’s culture and how we might gain more empathy and understanding, with the goal of dismantling systemic and oppressive barriers around us and instead create a sustainable pathway toward equity for all who come to learn with us.

These conversations and initiatives are our compass guiding us toward building and sustaining the dynamics

of campus inclusion. We are focused on understanding the extent to which students and practitioners HEAR us saying they belong, BELIEVE they belong, and BECOME an active part of the community that in turn designs more support and representation. Over the last year, these conversations have taken place in multiple ways. Here’s a look at just a few of the projects and initiatives that were my way to build bridges at the d.school.

The Black Community Services Center (BCSC) Admit Weekend + Black Community Welcome

Stanford’s Black student population is just shy of 8 percent. That’s why Admit Weekend for The Black community is important to the incoming students and families and for current student participation as well.

TEACH & LEARN 48

An in–person version of Admit Weekend has not happened on campus since April of 2019 due to COVID –19. The Black Community Services Center (BCSC), also known as The Black House, has worked endlessly to maintain community, even while in a remote state.

However, in 2022, we were able to collaborate and welcome admitted students to the d.school atrium for an in-person experience that provided a brief introduction to Black staff/faculty, Black student organizations and academic resources, and the d.school.

(in)VISIBLE Designers Series

The (in)VISIBLE Designers is a series created to build community between Black and Brown leaders of organizations that represent and serve marginalized communities and whose work/service deserves to be made VISIBLE

Season One consisted of two sessions, with leaders disrupting traditional forms of education, technology creation, art/fashion, and the digital divide.

In collaboration with George Hofstetter, Founder and CEO of GH Tech, we had the opportunity to sit with Akinatunde Ahmad, a writer, podcaster, and filmmaker, and the legendary Dr. Angela Davis, educator, community activist, and former Black Panther Party member.

The community heard the speakers reflect on a series of questions posed by George and me at the beginning of each session. The questions incorporated reflections on life experiences and applied community and human-centered frameworks that each speaker has applied in their daily problem–solving while also giving the speakers metaphorical “roses” for their accomplishments and contributions to the community and world abroad.

The design sprints for each session focused on supporting and challenging attendees to incorporate new frameworks into their daily problem–solving while also encouraging them to create and build their own products, apps, services, and general ideas through community and human centered design work.

Black Panther Party Photo Exhibit with African and African American Studies (AAAS)

The program in African and African American Studies (AAAS) presented the “We Want A Free Planet” Black Panther Party photo exhibition, which was displayed in various spaces on Stanford’s campus in collaboration with community partners, including the Department of Art and Art History, Department of History, Stanford Arts Institute, Institute for Diversity in the Arts (IDA), Black Community Services Center (BCSC), Black Studies Collective (BSC), the d.school and the Vice Provost for Undergraduate Education (VPUE).

The photo exhibition coincided with the 55th-anniversary celebration of the Party's founding. AAAS–PostDoc, Dr. Kimberly McNair, curated the photo exhibit with Mr. Billy X Jennings, a Panther veteran and historian, former personal bodyguard to Huey P. Newton, and the chair of this year's BPP Anniversary committee.

I co–curated the show with Charlotte Burgess-Auburn and Amanda Tiet. Together we printed the photos and displayed them in the d.school atrium. The Black Panther Party photo exhibition opening reception happened at the McMurty Building for the Department of Art and Art History.

d.SCHOOL YEARBOOK 2021 2022 49

All of this represents just some of the work that goes into Designing Bridges. It requires not just one bridge and not just one topic of discussion. It requires working with multiple communities, addressing multiple challenges, and sustaining construction on multiple bridges that bravely and safely make space for the community to engage with the world of design thinking and that, most importantly, ensure all feel welcome to contribute to design for generations to come.

The Beginning (not the end).

TEACH & LEARN 50

& & &

Access Access Access

Sharing Design Ideas and Tools

As designers, we are often quick to move on to the next thing we want to create, build, teach, or imagine. Attending to whatever new challenge or needs are emerging inspires and fuels us. Yet recent months have seen d.school team members engaged in an intense period of documentation: reflecting on what we’ve learned and shaping new tools and publications meant to travel far beyond the d.school’s physical footprint. Our work is aimed at sparking confidence in

young people grappling with what new technologies mean for them as creators, school leaders in need of new ways to address the school safety crisis in the US, innovators in the social sector tackling systemic challenges, and more. This section features a range of new releases from the d.school team in a wide variety of formats and mediums.

Impact

→ → d.SCHOOL YEARBOOK 2021 2022

Impact Impact

REP Magazine REP Magazine REP Magazine

By Ariam Mogos

esigners hold many responsibilities; this is true in any field but particularly in the field of technology due to the way it’s rapidly shaping human societies and the environment. REP magazine was created for young people as a way to explore the ethical and moral implications of tech design. Discovering the impact these decisions can have on various communities and the public can lead to more equitable design.

The first issue of REP, “Build a Bot,” was released in 2021 and is now available for purchase on Amazon and Lulu. Since its launch, the team has been exploring bigger distribution channels with K12 publishers to reach schools, libraries,

and other learning communities. As a result, 2021-2022 was a big year for REP content production, testing, and distribution.

The REP team also continues to test content for new issues with diverse audiences. One exciting crowd we tested with in-person this year was at SXSW. We held a packed session with over sixty participants called “Designing with Emerging Implications.” We also facilitated an activity from the second issue of REP called “Design a Cow,” which is all about synthetic biology. Participants had insightful questions and critiques about the implications of gene editing on the agriculture industry and animal welfare. The REP team also received great feedback for the next iteration of the issue before it goes to print.

At the d.school we think that it’s critical for young people to understand the impact that their work can have in the world. REP magazine aims to support students and educators in their understanding of the responsibilities designers hold in many of the decisions they make.

IMPACT & ACCESS 54

d.SCHOOL YEARBOOK 2021 2022

Magazine agazine Magazine

“I was excited when I ordered this, but woah! This magazine is so much better than I could have imagined. My innovation and design students will love it.”—Alexis Lecznar

Creative Acts for Curious People

Creative Acts for Curious People Acts for Curious People

By Sarah Stein Greenberg

a Collection that Celebrates the d.school IMPACT & ACCESS 58

Creating

hrough the history of the d.school hundreds of people have left a lasting gift: deliberately designed learning experiences. These experiences were created in response to a need to teach a skill or method in a personal, collaborative, or experiential way, and many then evolved over the years through student feedback, iteration, and interpretation by the other instructors who adopted and adapted them.

When I set out to write Creative Acts for Curious People, I aimed to collect and curate a wide range of the assignments we give to learners, and highlight the many different perspectives and ideas that intersect and overlap at the d.school. I hoped that readers would resonate immediately with some, and that others would provoke them to think, act, and make in ways they hadn’t yet considered or mastered. I deliberately mixed old favorites with new gems; a few time–tested practices along with fresh takes from some of our newest instructors.

I also had a major problem to solve. We teach in such a vibrant, improvisational, experiential way: How

on earth could that come to life on the pages of a static object like a book? I realized that the quality (and qualities) of the art on each page would do a lot of this work, and collaborating with illustrator Michael Hirschon was an exceptionally fun part of the creative process. Mike’s sense of the absurd, and his ability to juxtapose images that are tender and sweet with ones that are playful and raucous was incredible fuel for the project, as you can see from the spreads here.

A few people have asked me if the book has achieved the goals we set for it. I’m happy to say yes! Part of the aim of our entire d.school book series is to evolve what we’re known for and help a broad audience learn about the wide range of design practices and ideas in play at the d.school. When I think back to the fifty or so podcasts and articles that were generated about Creative Acts in the first months after it was published, in only one of them was I asked to talk about the old five-hexagon design process model. That gave me forty–nine opportunities to tell the public about everything else we do. And, I’ve seen many unexpected moments of impact unfold in a way that helps paint a picture of all the folks we’re now reaching: the recent grad who self-organized a Creative Acts book club on LinkedIn, the public library in

d.SCHOOL YEARBOOK 2021 2022 59

Over the past fifteen+ years, d.school classroom experiences have been defined by an extraordinary array of designers, educators, academics, and topical or industry experts. Creative Acts for Curious People is a collection of their work—and much more.

Johnson County, Kansas who shared it with all the attendees of their free, annual writers conference, the guy in Australia who wrote me out of excited frustration that his local bookstore wasn’t yet stocking any copies.

It’s been a tremendous honor to create a vehicle that could feature so many different d.school voices. The work of many, many people had to happen first for this book to be possible, and I am grateful that along with Charlotte Burgess–Auburn and Scott Doorley, I got to shepherd this particular creative act out into the world.

d.SCHOOL YEARBOOK 2021 2022

Introducing d.school Introducing d.school Introducing d school

IMPACT & ACCESS 62

Introducing the Guides Introducing the Guides Introducing the

Creative Ways of Cultivating Resource–fulness and Inventiveness

By Scott Doorley and Charlotte Burgess Auburn

Way back in 1947, design pioneer Lászlo Moholy-Nagy predicted the inclusive power of design when he said it should be seen as a “general attitude of resourcefulness and inventiveness” instead of a specialized field only for the few. We love craft and experts, but who doesn’t want to be a little more resourceful and inventive?

d.SCHOOL YEARBOOK 2021 2022 63

IMPACT & ACCESS 64

In this new series of ten books, “The Stanford d.school Guides,” each book introduces unexpected fundamentals, creative mindsets, and practical methods that are destined to become a brick in every reader’s creative foundation. As a set, they are equal parts “how to” and “how come.” They are filled with tactics to help navigate the ambiguous, sticky challenges you face in your life’s work—whatever your field. At the same time, they are full of spirit. These are guides. Like any good guide, they are confident, helpful, full of personality, and at your service. But there’s a small twist: these books are not for designers. They are by designers, but they are for designing. They are about making change for others, with intention, no matter who you are, no matter where you are.

d.SCHOOL YEARBOOK 2021 2022 65

a Collaboration a Collaboration

By Scott Doorley

Collaboration is the only way to make big things happen, but let’s be honest—sometimes you wish it weren’t. Getting everyone to agree on what to do at any given moment is always a trick, and not always a fun one. In a tough collaboration, the sum of the collective work isn’t a sum at all it’s division.

Everything Everything Everything

IMPACT & ACCESS 66

Collaboration

Everything

Everything

Books Edition 67

Collaboration Everything Is

Is

Is

hen a collaboration comes to fruition with grace and gusto, when everyone pitches in their talents and it all adds up—few things are more delightful.

The creation of our recent d.school books, which includes two stand–alone titles and a ten-book series, some of which are not yet published, required (and still requires!) many layers and waves of collaborative effort. We lucked into a delightful “it all adds up” collaboration with the authors and artists generating the content and also with the editors and designers at our publishing partner, Ten Speed Press. With Ten Speed, we all shared the same goal: to etch each author’s ethos onto the page through words and pictures. And they know how to do it. We were also lucky enough to work with a group of artists with diverse talents and backgrounds, who didn’t just augment the work, but transcended it. Each artist took the text to a new level, creating a whole that was truly far beyond the parts. We’re celebrating that beautiful effort on these pages.

Art Is Harmony

There are ten d.school guides, written by twelve authors, with art by a baker’s dozen of illustrators. One of the titles is half–full of comics; one is filled with custom–made manifestos, each in its own style; yet another is filled with giant gatefold murals that spread twenty-two inches wide. That is to say, the interior of each book does its own thing. Wrangling all that delicious, but far-flung exuberance into a coherent set is a tall order.

Enter Hope Meng. Hope is a typography and brand designer based in the Bay. To package this delightful mayhem, she created a custom typeface for the series covers (nicknamed d.sign). Its unwavering

line weight is clean and legible while its curvy and quirky details hint that it’s not so straightforward after all. The vibe is a bit like classic Swiss typography squeezed through a Play–Doh noodle extruder.

Hope’s typeface brings harmony to the series, even as the type treatment varies from cover to cover. Each unique cover lockup is built on the foundation of Hope’s crisp and playful font with varied arrangements that introduce the books on their own terms, and enough consistency to make sure the sleeves don’t clash when they sit next to each other on the shelf.

Who ever said you can’t have consistency and exuberance at the same time? (I did, see page 34).

Art Is Content

In most books, art supports the content. That’s the definition of an illustration— a picture that illuminates the content in the book. In several of the d.school books, the art doesn’t just illuminate the content, it is the content.

For a book on infographics, art is certainly key. But when you fold in a murder mystery, the art takes on many more layers. Part storytelling, part hard–working examples, the art in The Secret Language of Maps by Carissa Carter required two artists with two very different points of view to express the dual aspects of the book.

Charlotte Burgess–Auburn’s book, You Need a Manifesto, shows how to put your values to work by crafting a personal manifesto. The art by Rick Griffith goes one step further—each is a manifesto about what it takes to make a manifesto.

The word “drawing” in the title of Ashish Goel’s book, Drawing on Courage, is a double entendre. It describes the need to summon your courage, but the impetus for “drawing” was actually the more than fifty hand-drawn comics by Ruby Ellis that cover half of the book’s pages.

IMPACT & ACCESS

68

Designing the d.sign Font

By Hope Meng

When we began our collaboration on this group of covers, the sky was blue! Any and every relevant bit of pasta was thrown at the wall—existing typefaces were used, type was integrated with illustration, there were gradients! But it quickly became clear that the covers required cohesion greater than just black type on a solid background—we needed a consistent font, one that was basic enough to absorb a universe of expressive manipulation, but charismatic enough to provide an identifiable personality. It had to be capable of growing vertically or horizontally, get bold or light, and provide every letter width between ultra condensed and extra wide. That’s a tall order for a font!

Formally, I knew what this meant: a sans serif typeface that provides a straight area on both the vertical and horizontal axes. On the vertical axis, this would allow the letterform to grow or shrink in height as needed for the composition. Similarly, the area on the horizontal axis would allow the width to change.

Once these constraints were identified, I set about designing some fairly standard letterforms and their exuberant alternates, fully expecting a request to dial back the personality. Anticipating that I’d inevitably get called out on that weird R or that funky N, I’d have a more straitlaced version in my back pocket.

But the d.school’s laces are anything but straight! I was delighted when the team not only approved the quirky letterforms, but wholeheartedly embraced them. They were a feature, not a bug!

The quirky yet simple nature of this font primed the canvas for a visually expressive and instantly identifiable set of covers. Though each book ranges in mood, content, and style, d.sign conceptually unifies the series under a singular umbrella: bold ideas with an unapologetic dash of personality.

d.SCHOOL YEARBOOK 2021 2022 69

The artists The artists The artists include include include

Alphabetical by last name:

Ruby Ellis London–based comic artist focusing on mental health

Rose Jaffe

D.C. area muralist and activist

Rick Griffith Graphic designer, activist, and letterpress printer

Celia Leung Hong Kong-based graphic designer

Michael Hirshon University of Utah art professor and illustrator

Andria Lo Product, still life, and portrait photographer

Ruby Ellis London–based comic artist focusing on mental health

Rose Jaffe

D.C. area muralist and activist

Rick Griffith Graphic designer, activist, and letterpress printer

Celia Leung Hong Kong-based graphic designer

Michael Hirshon University of Utah art professor and illustrator

Andria Lo Product, still life, and portrait photographer

IMPACT & ACCESS 70

Che Lovelace Trinidadian painter and surfing champion

Gabriela Sanchez Uruguayan art director and illustrator

Scott Teplin Maniacally detailed, NY-based fine artist

Hope Meng Typeface and brand designer

Khristopher “Squint” Sandifer Storyteller, photographer, and creative director

Jori Tytus Bioengineer and collage artist

Jeremy Nguyen New Yorker cartoonist

Che Lovelace Trinidadian painter and surfing champion

Gabriela Sanchez Uruguayan art director and illustrator

Scott Teplin Maniacally detailed, NY-based fine artist

Hope Meng Typeface and brand designer

Khristopher “Squint” Sandifer Storyteller, photographer, and creative director

Jori Tytus Bioengineer and collage artist

Jeremy Nguyen New Yorker cartoonist

d.SCHOOL YEARBOOK 2021 2022 71

Reina Takahashi Intricate cut paper artist

Art Is Design

One of the wonderful things about working with d.school authors is that they don’t think of a book as something to be written. Rather, they see it as something to be designed. Each part communicates the message: the words, of course, but also the layout, the font, and the art. It all adds up and works together, part and parcel of an integrated whole.

In Navigating Ambiguity, Reina Takahashi’s exquisite cut-paper art in grayscale sets the tone and tempo for a book about finding your way through ambiguity.

For Design for Belonging, Rose Jaffe brought the spirit of her large mural work to the project by creating gatefolds that grow and expand beyond the bounds of the book.

Her work brings a sense of flow and energy that extends off the page as an invitation to the reader.

This is a Prototype is what happens when (wacky and wonderful) minds team up with a shared vision. Scott Witthoft’s precision, wit, and love of puns is perfectly amplified by the humor, whimsy, and attention to detail found in the work of fine artist Scott Teplin.

With lines like “Be the badass bouncer of your mind,” the art and design of Grace Hawthorne’s Happen needed to be bold. Celia Leung, a Hong Kong-based designer, brings a strong and innovative design to the book—and she uses neon orange ink!

IMPACT & ACCESS 72

Art Is Connection

The obvious role of art is to help explain the ideas in the book. Great art nails that role and adds an extra layer of context and meaning. When it works well, art can express feelings of joy, identity, and heritage. In several books, the art opened up opportunities to connect to community and culture, people and home.

In Design for Social Change, Lesley Ann-Noel is working with an old friend, Che Lovelace, to integrate his original paintings of their home country of Trinidad and Tobago. His art from their shared home complements writing that delves into how identity and design are intertwined.

Leticia Britos Cavagnaro’s book, Experiments in Reflection is about how we make meaning from experience. She’s taken this message beyond the text to the artwork itself. Hiring an artist from her home country of Uruguay was just the start. Leticia then connected artist Gabriela Sanchez to her father, who gave Gaby stacks of family photos to incorporate in her collage work—adding layers of personal meaning within the art itself.

Creative Hustle by sam seidel and Olatunde Sobomehin is a celebration of the ingenuity and creativity of makers at the top of their game. The collection of profiles feels like the gathering of a community, and this feeling connects to the collaborative effort of the three artists who created the visuals for this book: photographer Khristopher “Squint” Sandifer, type designer Hope Meng, and collage artist Jori Tytus.

d.SCHOOL YEARBOOK 2021 2022 73

Faces of Change Faces of Change Faces of Change

Work from the University Innovation Fellows

By Leticia Britos Cavagnaro, Humera Fasihuddin, Lupe Makasyuk, Laurie Moore, and Ghanashyam Shankar

The first line of the University Innovation Fellows manifesto is “We believe students can change the world.” This belief is at the heart of our program. Each year, we work with hundreds of students and educators to help them make a difference in higher education.

IMPACT & ACCESS 76

hen we founded the University Innovation Fellows program a decade ago, we wanted to give students access to tools and mindsets so that they could contribute to the future of higher ed. Our belief was (and still is) that students know what they and their peers need in order to be forward–thinking, creative leaders in any field after they graduate. So we teach them to use design approaches to identify and address real needs and opportunities in their own contexts. Over time, we’ve created experiences for new communities—faculty, staff and school leaders—to learn the same change-making strategies as their students.

Today, our network extends to thousands of people who are applying human-centered design to challenges at their schools and in the world. Our community members are creating new majors and minors, building maker spaces, designing feedback systems between students and administration, starting K12 and community outreach programs, hosting events and workshops, teaching classes that address real world problems, and much more. The four stories below are just a sample of what students and faculty in our programs worked on in the last year.

d.SCHOOL YEARBOOK 2021 2022 77

My UIF team (Shafeqah Mordecai, Syeedah White, and myself) have been working on increasing student engagement and support for students who commute. We’ve done this by looking at three areas: commuter student lounges on campus; support for students who have children; and updating the BSU app/event calendar. We engaged with campus stakeholders and administrators and adjusted our plans based on their feedback. We worked with the dean of the College of Business to suggest ideas for the lounge. We conducted a survey centered around our suggested improvements to determine what ideas students would like to see happen. We participated in a focus group and interviews with students who are parents, which helped provide more insight and gauge interest in having an on–campus childcare center. Finally, our group was also asked to join a committee that is working to get a childcare center on our campus.

As part of our UIF training, we were taught to analyze problems and find solutions through design thinking. The problem we identified was around student depression and anxiety—both before the pandemic, but especially during it. The COVID –19 pandemic has caused social isolation, yet as we are social creatures, meaningful connection is vital to us. We organized the Meet & Greet so both students and employees could casually gather and connect with one another while abiding by the COVID regulations. We created safe opportunities for students to make meaningful connections. Four Meet & Greet locations were open every day for the duration of the project, and people could walk in anytime as long as it was within the opening hours of the building. We arranged standing coffee tables with conversational cards to help get people talking. This project is expected to continue and improve over time. Before we created this, I used to think that fostering communication always leads to community building. Now I think that communication is only the first step to community building. Engagement, exchange, and mutual experiences are equally as important.

I embarked on this University Innovation Fellows journey as a faculty champion two years ago out of the need I felt to open up spaces where my students could explore solutions to some of the big challenges we are facing. Although the Sophia Fellows have just recently embarked on their journey as changemakers, they are already contributing to their community. Among their initiatives they are facilitating cross-discipline discussions on sustainability between faculty and students; hosting youth-empowerment workshops at secondary education institutions; creating workshops and programs to tackle sustainability issues; and creating events that help participants apply design thinking to campus challenges. Starting on a journey like this with your students may seem daunting. It did for me! At first, all I could see were limitations and obstacles. But throughout any period of self-questioning and self-doubt, I kept reminding myself: “My students need this! And our communities need them!”

Britnee McCauley University Innovation Fellow Bowie State University (Maryland, USA)

Radhika Kapoor University Innovation Fellow University of Twente (The Netherlands)

Britnee McCauley University Innovation Fellow Bowie State University (Maryland, USA)

Radhika Kapoor University Innovation Fellow University of Twente (The Netherlands)

IMPACT & ACCESS 78

Magdalena Ionescu Faculty Innovation Fellow Sophia University (Japan)

Malott Teaching & Learning Studio Fanshawe College (Canada)

During the pandemic, we identified a gap between the skills gained through college programs and future work opportunities for Indigenous learners. Initially, the challenge we were working on was to create a program to help students who struggled academically from the pivot to online learning because of COVID –19. We tried and refined several iterations and versions. The current version of the Niisitaug: Community Innovation program looks to provide students with authentic learning experiences in community design, providing opportunities to practice collaboration, critical thinking, creativity, and Indigenous ways of thinking. Being engaged in an online video environment is tough. The design mindsets and tools I learned during the vTLS helped break down the learning process for learners in a way that got them to be more reflective and engaged. I like bringing design mindsets and toolsets to my work because they help me create space for students to be reflective and curious, and they show that I am on the same footing—I’m also curious and not the expert professor.

“Who are you in this moment?” 400 higher ed students and faculty collaged portraits of themselves in response to this prompt at the University Innovation Fellows Silicon Valley Meetup in March 2022. The UIF team partnered with Aisha Bain and Meredith Hutchison of Resistance Communications for the session, which demonstrated the power of storytelling and artistic expression for individuals who are trying to make a difference in the world. The session resulted in a public art installation showcasing each participant as an individual, as well as a member of a close-knit community. The UIF team and collaborators designed the 2022 Meetup to not only focus on helping community members drive change in higher ed, but also to focus on themselves—their mental health, their journey, their story. “They felt seen,” Aisha said, recalling some of the feedback she received afterwards. “They needed that.”

Brian

Brian

Conversation Conversation Conversation Changing Changing Changing

About School Safety

By sam seidel and Barry Svigals

The d.school’s K12 Lab has been investigating the role design can play in helping make schools safe and joyful spaces for learning. Our work aims to help us think about safety in holistic and creative ways.

IMPACT & ACCESS 80

Conversation Conversation Conversation Changing the Changing the Changing the