BLU E & W H I T E PAG E 2 6

From the Archives 'Rabid Sectarianism and Personal Antipathies': John Dunmore Lang and the Foundation of St Andrew’s College

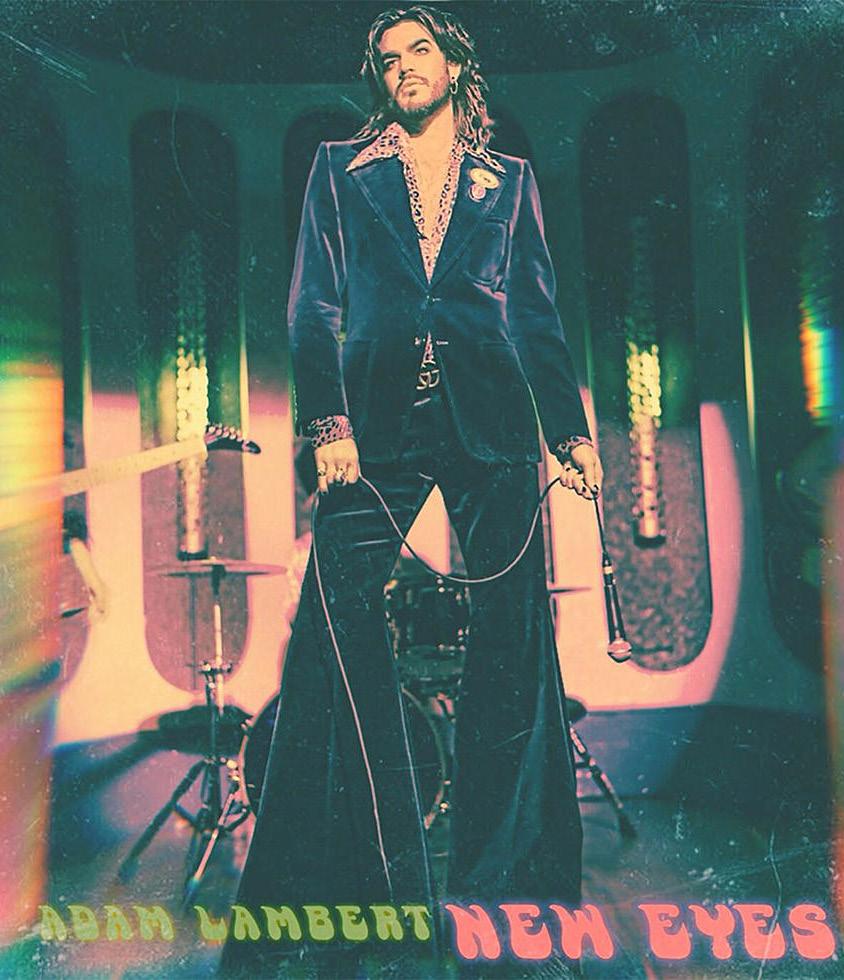

The Senior Common Room’s portrait of J. D. Lang, 1855. This portrait was made while Lang was serving a four-month prison sentence in Parramatta Gaol for libel. The artist, William Griffiths, a fellow prisoner, made this likeness on speculation and allegedly Lang never paid for the work. In the College’s Senior Common Room, grim nineteenthcentury portraits of the Reverend Doctors John Dunmore Lang and Robert Steel glare in opposing directions, refusing to meet each other’s eye. These men, both eminent in the mid-nineteenth-century politics of the Presbyterian Church, played prominent roles in the foundation of the College. However, they were bitter rivals in this project: Lang once described Steel as the ‘veritable Pharisee of the Pharisees’. Nevertheless, there is more to the College’s origins and to Lang than his scintillating invective. The fierce conflict over the future of ten acres in the corner of the University’s grounds revealed the larger divisions in New South Wales Presbyterianism in the nineteenth century. In 1865, the General Assembly of Presbyterian Churches finally achieved a union of the Synod of Australia, the Free

Church (led by Steel), Lang’s Synod of New South Wales, and the United Presbyterians. However, Lang’s 1872 observation that the College Council’s deliberations exhibited ‘the rabid sectarianism and the personal antipathies of the dominant [Free Church]’ shows that the Act of Union failed to heal the divisions of each faction. Suffused by the colonial awareness of creating a new society, the fraught election of the College’s first Principal aggravated these arguments about the doctrinal future of the Church. Lang’s frustrations, originating in the uneasy 1865 Union, manifested themselves dramatically in his contributions to the College’s Provisional Committee and Council. When in 1862 Lang and his brother Andrew began the legislative process of founding a ‘Presbyterian College’, he felt certain his claim as Principal ‘would not be disputed’. Such a post was important to Lang because the College’s 1867 Enabling Act provided for the establishment of a Theological School; whosoever established the traditions of Presbyterian education would hold a doctrinal influence of generational proportions. However, from 1865 the General Assembly and particularly Steel began to exert their influence on the process. They demanded amendments to the College Bill, changed its name to St Andrew’s College, and altered the theological balance of the Provisional Committee. The significance of Lang’s broad vision for the College as the institutional guarantee of the future of Presbyterian education and theological orthodoxy in the antipodes had been recognised by the other factions of the Church. As the College’s Provisional Committee continued to raise £10,000 in subscriptions to match the government’s contribution, Steel and his Free Church colleagues grew in influence. In 1870, ahead of the first impending vote for College Council, Steel returned from the New England district with subscriptions of £1170, whereas Lang was only able to produce £108. Outraged, Lang accused Steel of thinly veiled electioneering. He later argued that by this ‘artful but unwarrantable and unjust appropriation of… a field of exclusive agitation’, Steel had ensured a Free Church majority on Council. The first nominations for the Principalship were fraught and inconclusive. Steel withdrew early leaving the Reverends Adam Thomson and Lang as the main candidates. However, there seems to have been a view that having no college at all was better than a College with Lang as Principal. In 1871,