5 minute read

From the Archives

'Rabid Sectarianism and Personal Antipathies': John Dunmore Lang and the Foundation of St Andrew’s College

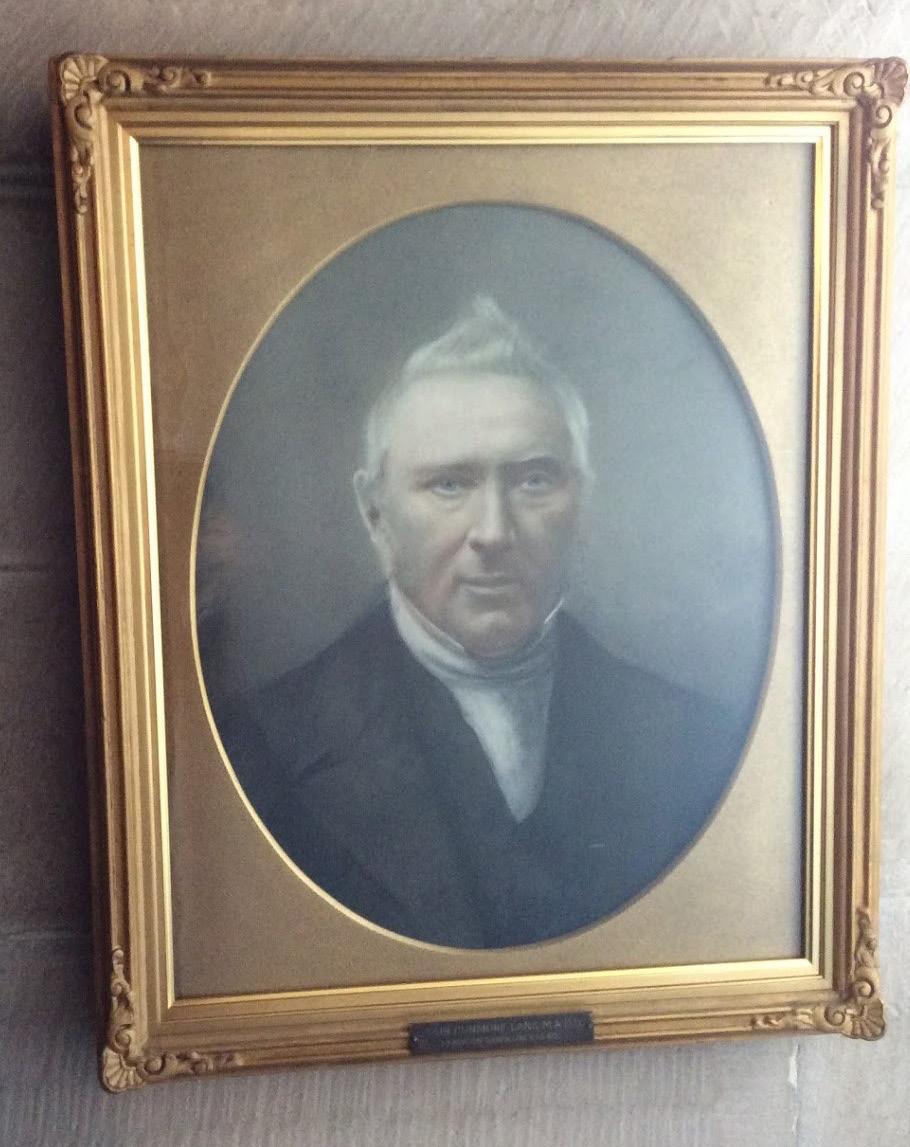

The Senior Common Room’s portrait of J. D. Lang, 1855. This portrait was made while Lang was serving a four-month prison sentence in Parramatta Gaol for libel. The artist, William Griffiths, a fellow prisoner, made this likeness on speculation and allegedly Lang never paid for the work.

In the College’s Senior Common Room, grim nineteenthcentury portraits of the Reverend Doctors John Dunmore Lang and Robert Steel glare in opposing directions, refusing to meet each other’s eye. These men, both eminent in the mid-nineteenth-century politics of the Presbyterian Church, played prominent roles in the foundation of the College. However, they were bitter rivals in this project: Lang once described Steel as the ‘veritable Pharisee of the Pharisees’. Nevertheless, there is more to the College’s origins and to Lang than his scintillating invective. The fierce conflict over the future of ten acres in the corner of the University’s grounds revealed the larger divisions in New South Wales Presbyterianism in the nineteenth century.

In 1865, the General Assembly of Presbyterian Churches finally achieved a union of the Synod of Australia, the Free Church (led by Steel), Lang’s Synod of New South Wales, and the United Presbyterians. However, Lang’s 1872 observation that the College Council’s deliberations exhibited ‘the rabid sectarianism and the personal antipathies of the dominant [Free Church]’ shows that the Act of Union failed to heal the divisions of each faction. Suffused by the colonial awareness of creating a new society, the fraught election of the College’s first Principal aggravated these arguments about the doctrinal future of the Church.

Lang’s frustrations, originating in the uneasy 1865 Union, manifested themselves dramatically in his contributions to the College’s Provisional Committee and Council. When in 1862 Lang and his brother Andrew began the legislative process of founding a ‘Presbyterian College’, he felt certain his claim as Principal ‘would not be disputed’. Such a post was important to Lang because the College’s 1867 Enabling Act provided for the establishment of a Theological School; whosoever established the traditions of Presbyterian education would hold a doctrinal influence of generational proportions. However, from 1865 the General Assembly and particularly Steel began to exert their influence on the process. They demanded amendments to the College Bill, changed its name to St Andrew’s College, and altered the theological balance of the Provisional Committee. The significance of Lang’s broad vision for the College as the institutional guarantee of the future of Presbyterian education and theological orthodoxy in the antipodes had been recognised by the other factions of the Church.

As the College’s Provisional Committee continued to raise £10,000 in subscriptions to match the government’s contribution, Steel and his Free Church colleagues grew in influence. In 1870, ahead of the first impending vote for College Council, Steel returned from the New England district with subscriptions of £1170, whereas Lang was only able to produce £108. Outraged, Lang accused Steel of thinly veiled electioneering. He later argued that by this ‘artful but unwarrantable and unjust appropriation of… a field of exclusive agitation’, Steel had ensured a Free Church majority on Council.

The first nominations for the Principalship were fraught and inconclusive. Steel withdrew early leaving the Reverends Adam Thomson and Lang as the main candidates. However, there seems to have been a view that having no college at all was better than a College with Lang as Principal. In 1871,

prominent layman Mathew Whytlaw wrote to the Secretary of Council saying that he could not ‘conscientiously contribute one farthing’ to College if Lang were Principal. Lang was no less forthright in his condemnation of what he perceived to be ‘a secret conclave of Free Church plotters’.

In an attempt to find a neutral resolution, Steel moved that a candidate be selected ‘from home’ by a committee of churchmen in Scotland. However, in a speech delivered to Council on July 18, 1871, Lang vigorously opposed this compromise. He denounced the plan as ‘a gross insult to every Presbyterian minister in this Colony’ and suggested that it may not be compliant with the 1867 Act, Lang's remarks about the rictus of sectarianism afflicting the Church in Scotland are revealing. Under pressure, Council sought the legal opinion of Alexander Gordon who found that such a course would indeed be ‘inconsistent’ with the law. It was Gordon’s opinion which became a major fulcrum of Lang’s indignation in his 1872 pamphlet in which he gave full expression to perceived personal injustice and the peril of the Church.

After this setback, on a motion of lay Councillor and man of industry, John Hay Goodlet, the Reverend John Kinross of Kiama was elected Principal seven votes to two. Lang made a furious protest that this Free Churchman and ally of Steel’s should be made Principal. Lang further alleged that because Kinross was not already on the Council, his election was ‘contrary to law’. Because of these objections, Kinross recused himself as Principal on 13 August 1872. Hoping to instigate crisis in the Council, Lang declined to attend a meeting for the election of a new Principal. He maintained that ‘all the calamities and mismanagement that have hitherto befallen our institution… have resulted exclusively from [the conduct of the election of Council in 1870]’. These tactics, however, came to nothing during a meeting of Council on 24 September, Lang lost a ballot for the Principalship to Steel’s ally and fellow Councillor, Reverend Adam Thomson.

This loss infuriated Lang and he condemned the College as ‘conceived in sin and brought forth in iniquity’. Nevertheless, he remained on Council until his death in 1878 and continued to cost the College hundreds of pounds in legal expenses through his challenges to the Principalship. Contrary to the largely panegyric biographies of Lang, this conflict shows equally his indignant egotism, and genuine concern for the future of his Church and the Colony. Lang’s determination to wrest control of College away from the Free Church illuminates both sides of this complex personality.

Alex Wright (Fr 2014)

Dean of Studies

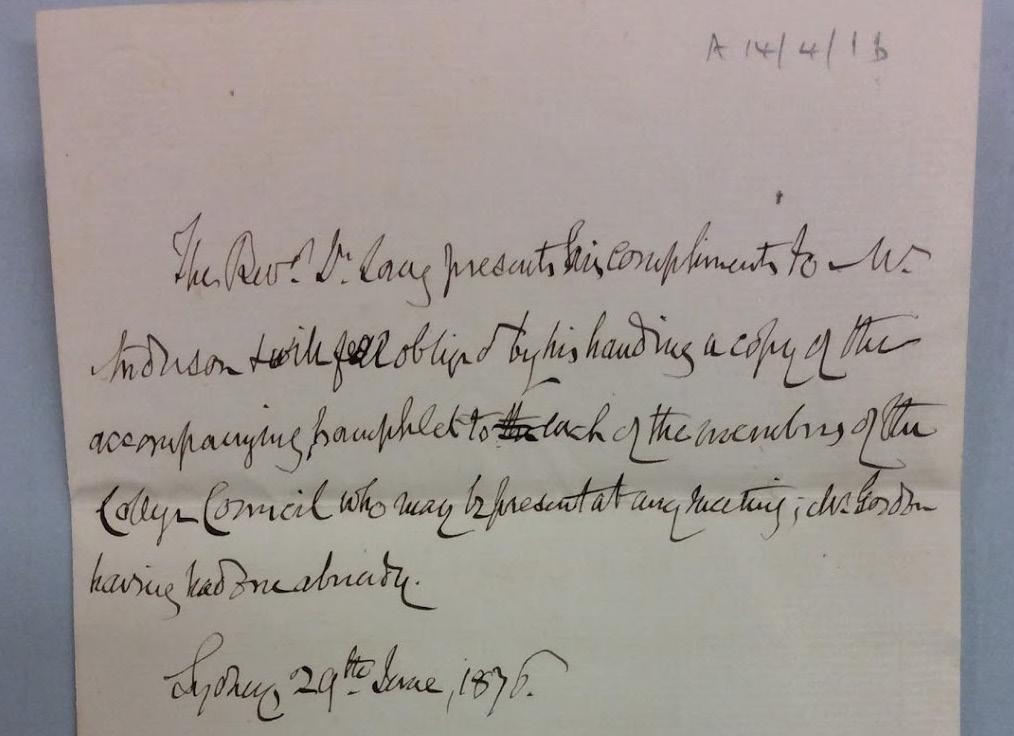

An 1876 letter from Lang to the College Council which sizzles with understated, gentlemanly vitriol: ‘Revd. Dr. Lang presents his compliments’. This letter accompanied a packet of vituperative pamphlets which denounced the College and its Council as being ‘conceived in sin and brought forth in infamy’. Lang’s unique, crabbed hand, made less steady by his 77 hard years, presents a real challenge to an archivist.

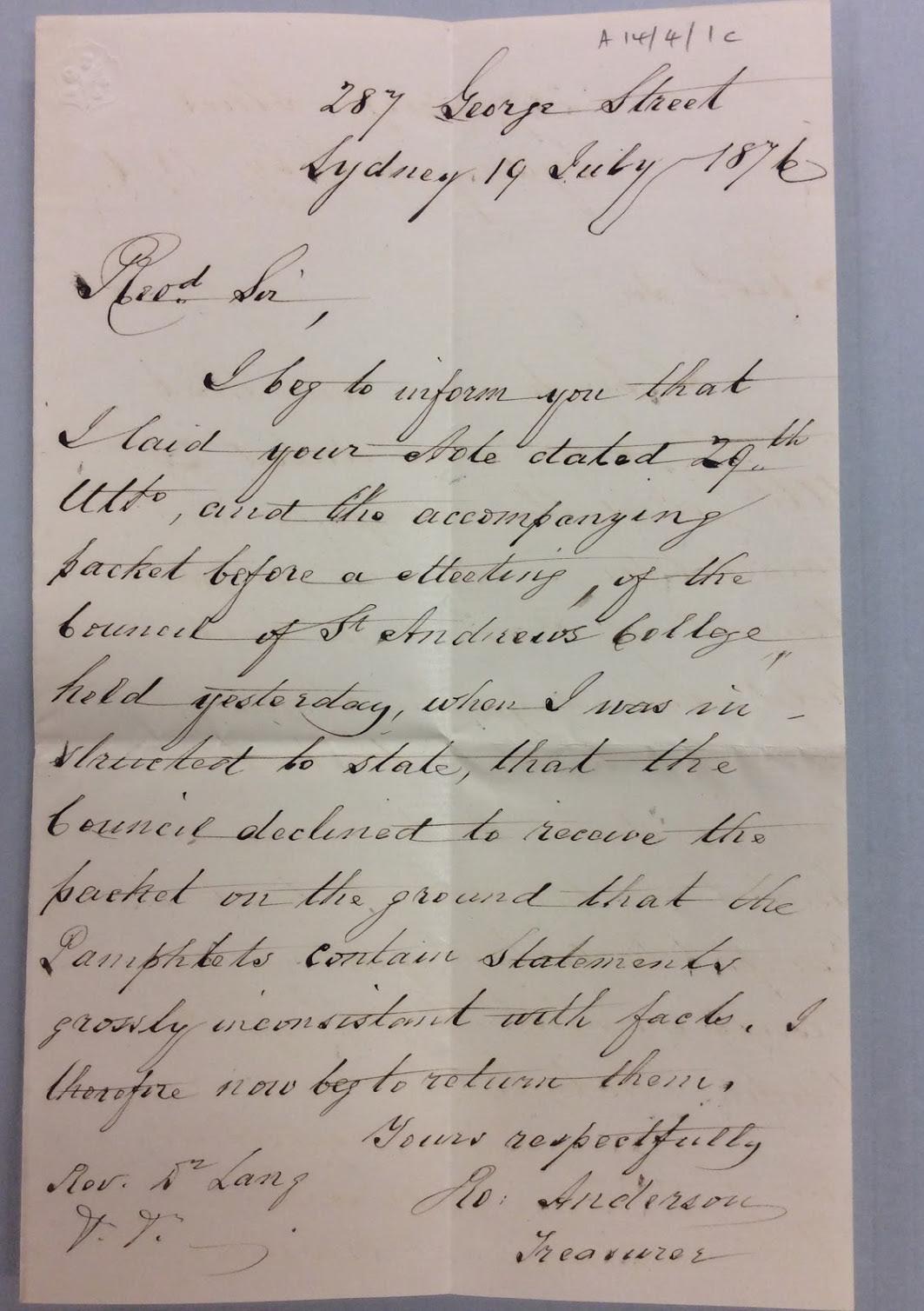

The Council’s haughty reply to Lang’s pamphlets. The style of handwriting is only the meanest difference. Though the Treasurer Anderson signed the note ‘Yours respectfully’, the attitude of the Council was bitter. He told Lang, ‘The Council declined to receive the packet on the ground that the Pamphlets contain statements grossly inconsistent with facts.’