My Name is cain and i never kNew abel the original siN was caste “i have no choice; the poisoN is near...”

My Name is cain and i never kNew abel the original siN was caste “i have no choice; the poisoN is near...”

Honi Soit operates and publishes on Gadigal land of the Eora nation. We work and produce this publication on stolen land where sovereignty was never ceded. The University of Sydney is a colonial institution. Honi Soit is a publication that prioritises the voices of those who challenge colonial rhetorics. We strive to continue its legacy as a radical left-wing newspaper providing students with a unique opportunity to express their diverse voices and counter the biases of mainstream media.

Editors

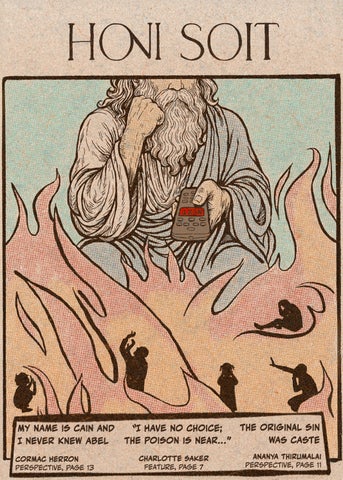

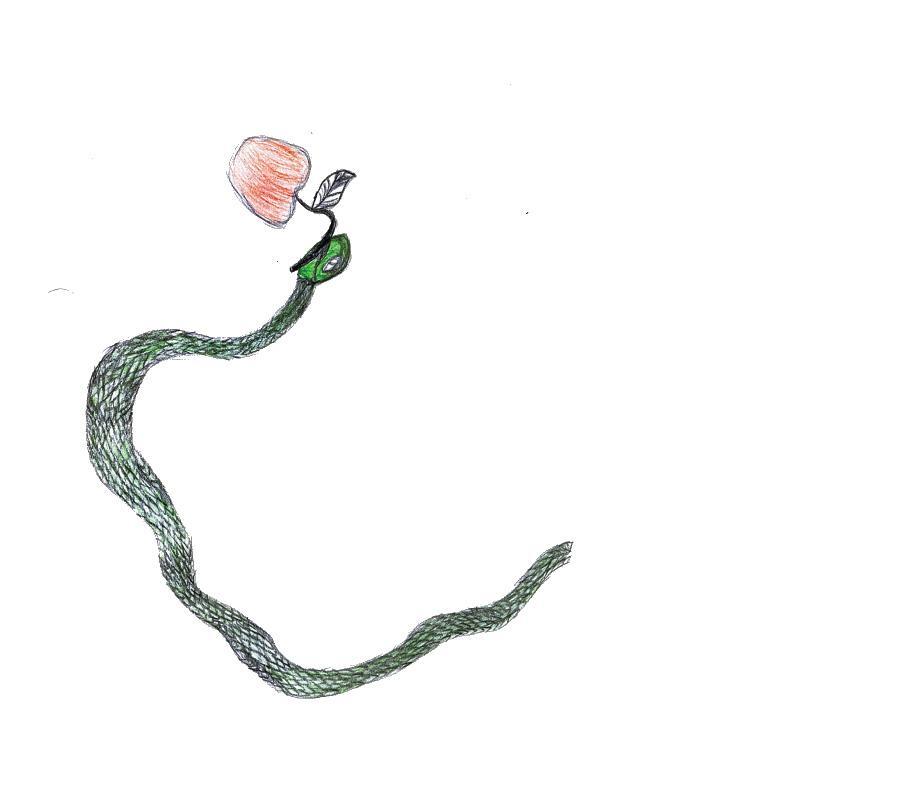

This week’s concept is very dear to my heart. A concept rooted in Abrahamic faiths, ‘The Fallen World’ describes a world corrupted by sin, leading to suffering, death, and separation from God’s “original perfection”. This state of brokenness began with the “Fall of Man”, when Adam and Eve disobeyed God and ate the forbidden fruit in the Book of Genesis.

In Catholicism, my faith, this event marked the origin of original sin, a condition believed to be inherited by all humanity. Despite its heaviness, the concept of the Fallen World also carries the possibility of redemption and salvation through Christ. While religious in origin, the Fallen World does not need to be taken as such. It represents the beautifully fragile human condition and the pursuit of something greater than ourselves.

I think that I was Catholic before I was anything else. I attended a Catholic preschool, a Catholic primary school and a Catholic High School.

Say Catholic one more time.

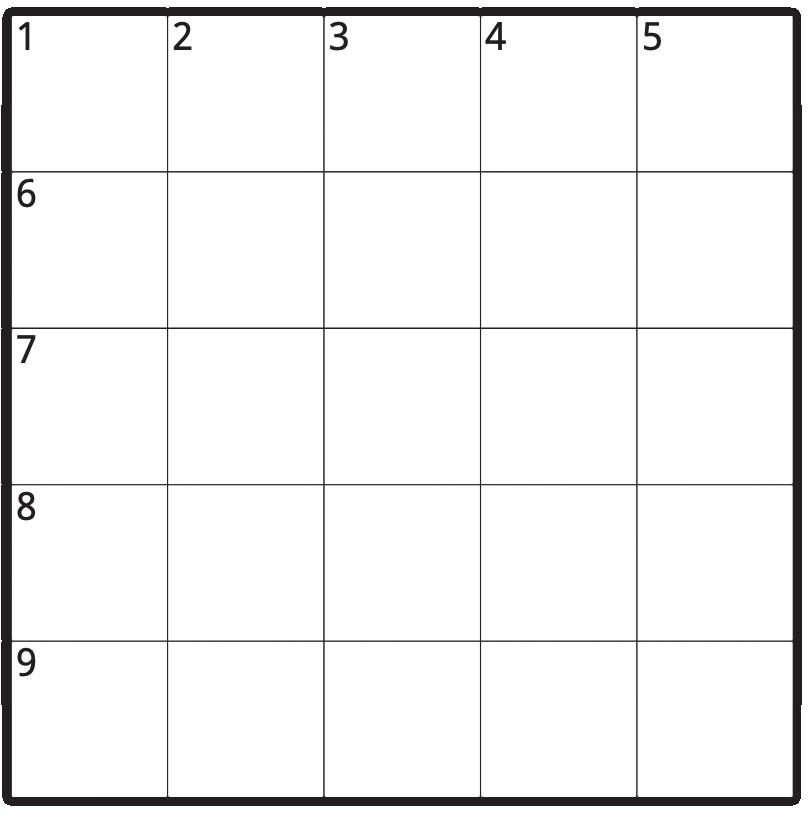

More Puzzles

My education has been completely and utterly rooted in religious teachings and culture until now. At Sydney Uni, it’s secular and new and a little bit freeing, as I sit here editing a newspaper that values the fringe over the traditional.

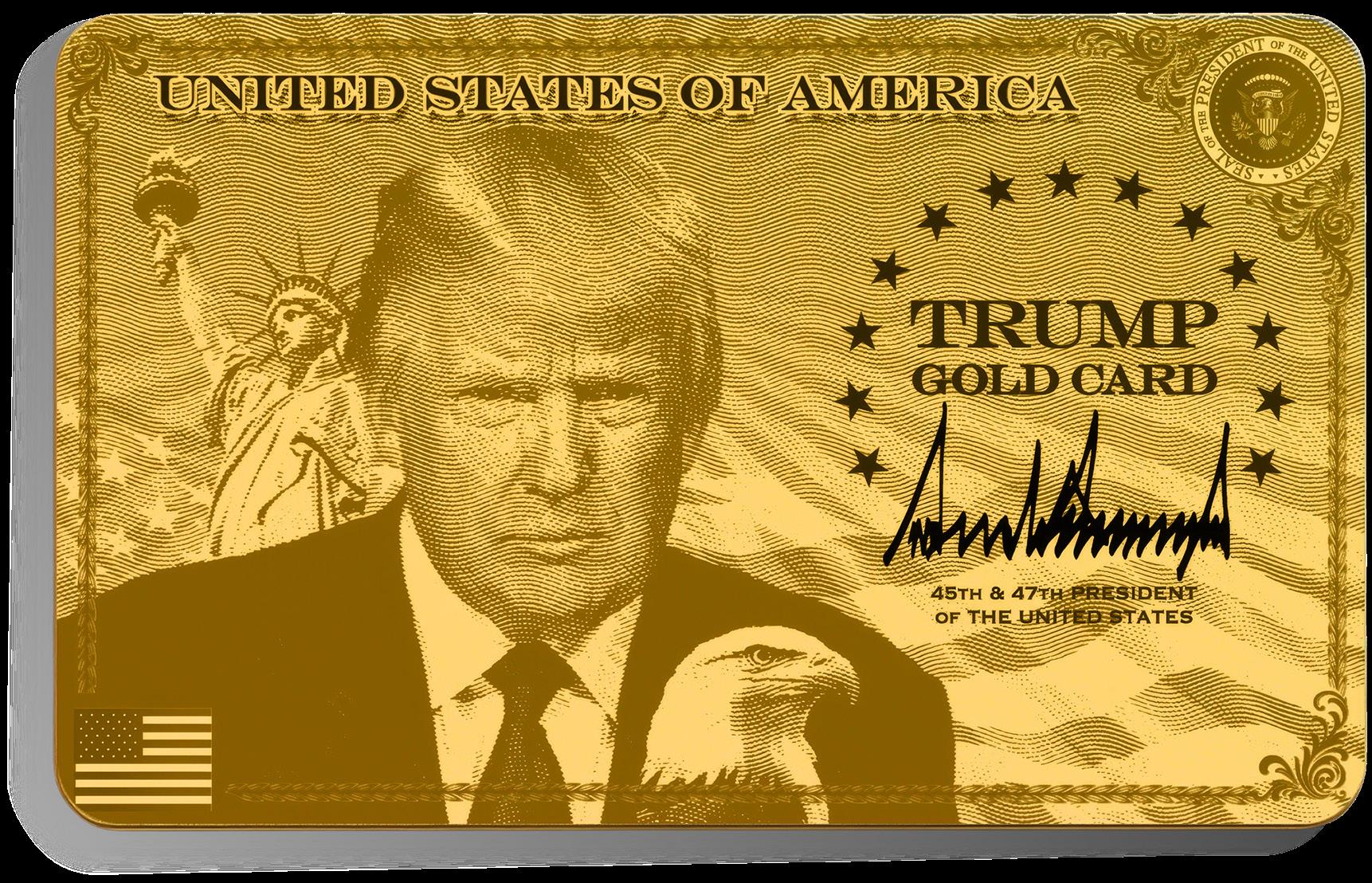

For a few years I’ve struggled with my faith, and so ‘The Fallen World,’ feels both close and distant at the same time. I hoped for the front cover to represent this dissonance. Often, the divine feels passive, simply watching on without action, a notion which hundreds of millions of people feel, of faith or not.

But I also interpret it as God is watching, and He cares deeply. He hopes for us to use our free will and change the world with His guidance. The cover does not intend to attack or offend any religious person or religion, but rather, through the classic archetype of ‘God’, make commentary on both the absence and presence of the divine. One could say the God-like figure represents our world leaders or billionaires, or even us, as the world falls with bangs and with whispers. Is the fire Earth, is it Hell, or are the two indistinguishable?

This cover, God is Always Watching, wrestles with the silence of divinity in times of violence and conflict. God is powerful yet passive, sitting and watching disinterested as flames consume humanity below. It reflects the paradox of belief: an all-seeing God who witnesses suffering but does not intervene. The work is about

Purny Ahmed, Mehnaaz Hossain, Ondine Karpinellison, Ellie Robertson, Imogen Sabey, Charlotte Saker, Will Winter, Victor Zhang

Front Cover

Bianca Pole

His remote is pointed at you.

In this edition, you will read about concepts of original sin in other faiths, the trials of conversion therapy, the experiences of exchange students in the USA, and, in the feature, you’ll learn about the state of forced marriages in Australia and its prevalence among young people, which often goes overlooked.

I hope you enjoy the vintage comic style laced throughout the paper, and the extra puzzles; the people want puzzles! Mostly, I hope that certainty finds you when doubt and fear try to rob you.

I leave you with two bible verses that whiz back and forth in my head quite often:

My God, why have you forsaken [us]?

Do not fear, for I am with you.

With Love, Charlotte

confronting the uneasy tension between divine presence and divine inaction as well as asking “How can a loving God be so cruel?”. By placing viewers among the burning figures, the image asks: if God is always watching, why does nothing change? And what does that mean for us who remain?

Purny Ahmed, Sophie Bagster, Max Dermott, Louis Friend, Cormac Herron, Mehnaaz Hossain, Gabriel Jessop-Smith, Jenna Rees, Imogen Sabey, Charlotte Saker, Jessica Louise Smith, Ananya Thirumalai, Ned Tulip, Sebastien Tuzilovic, Will Winter, Victor Zhang

Artists

Purny Ahmed, Will Winter, Ondine Karpinellison

Hi Admin,

Actually we want to work with you

I have some articles for your website https://honisoit.com/

But have a problem we have not prices your site

Kindly if you confirm the prices and give us discounted offer for our articles so we will happy too work with you

So now i am waiting for your response

Thanks

Owen Lucky

$10,000,000,000,000 per article

Editors, Honi Soit

Are you sure?

Owen Lucky

Yes! I need it NOW

Editors, Honi Soit

Tell me the fair price. This is too much.

Owen Lucky

I will pay you $100.

Owen Lucky

Prove you’re not a bot

Editors, Honi Soit

Are you crazy? What you means?

Owen Lucky

Show us a draft article please xx

Editors, Honi Soit

Happy to provide more info if needed.

Looking forward to your response!

Thanks and Regards, Rose ruck

week we get several silly emails asking us what our price is. We do not accept articles for payment.

Hi,

I wanted to check in regarding my previous email. When you have a moment, I’d be grateful if you could take a look and let me know your thoughts.

Thanks and Regards, Rose ruck

Hi,

I’m Rose Ruck and recently came across honisoit.com

. I enjoyed your latest post and shared it with my team as a great example of quality content.

I’m interested in a sponsored post collaboration and have a few topic ideas in mind. Could you share your rates and contributor guidelines?

Looking forward to hearing from you!

Thanks and Regards, Rose ruck

Hi,

Just following up on the sponsored post idea I sent over. I’d love to hear your thoughts and see if it could be a good fit for your blog.

Hi,

I wanted to follow up on the sponsored post idea I sent over and see if you had a chance to review it. I’d love to hear your thoughts and find out if it might be a good fit for your blog.

If you need any additional details or have questions, I’m happy to provide more information.

Looking forward to hearing from you!

Thanks and Regards, Rose ruck

If you write us letters, and not weird requests like these, we very much appreciate them.

Send your letters to editors@ honisoit.com

SRC Elections 23rd–25th September

Coalition of Women for Justice and Peace Silent Vigil Strathfield Station 25th September, 6pm

Conservatorium Cultural Showcase Night Con Music Cafe 25th September, 6:30pm

Casual Affair Lazy Thinking Dulwich Hill 25th September, 7pm

SRC Election Party

Ask your headkicker

Nationwide March for Palestine Hyde Park 12th October, 1pm

Will Winter’s Honours Thesis is Due November 14th

Purny Ahmed and Victor Zhang report.

The Australian Labor Government has formally recognised the independent and sovereign State of Palestine, as of 21st September, 2025.

The joint statement was released by Prime Minister Anthony Albanese and Foreign Affairs Minister Penny Wong, alongside similar statements of recognition from Prime Minister Mark Carney of Canada and Prime Minister Keir Starmer of the United Kingdom as part of a “co-ordinated international effort” towards a two-state solution.

Albanese’s statement notes Australia’s “longstanding commitment to a two-state solution,” stating it as the “only path to enduring peace and security for the Israeli and the Palestinian people”.

The statement calls for a ceasefire in Gaza, as well as the release of the hostages from the Hamas attack on 7th October, 2023.

The government outlines the “clear requirements” set out by the international community for Palestinian Authority, recognising President Mahmoud Abbas as the head of state, and the removal of the “terrorist organisation Hamas”.

Abbas has restated Palestinian Authority’s “recognition of Israel’s right to exist”, pledging to hold democratic elections and enact reforms to finance, governance, and education.

Further, it states that the international community is undergoing “crucial work” to develop a “credible peace plan”. This plan will aim to enable the

reconstruction of Gaza, build the capacity of the state of Palestine, and guarantee the security of Israel.

However, further steps, such as the “establishment of diplomatic relations and opening embassies” will be considered, and remain contingent, on the Palestinian Authority’s “progress on its commitments to reform”.

Opposition leader Sussan Ley describes the act as a “hollow gesture of false hope” and a “chilling act of concession to the Hamas terrorist”, restating the Coalition’s objections to recognising a Palestinian state.

In its closing line, the Australian government suggests a commitment to “bring the Middle East closer to the lasting peace and security that

is the hope, and the right, of all humanity.”

This statement comes after almost two years of active genocide in Gaza and 77 years of illegal occupation.

Israel continues to besiege Gaza City and intensify settler violence in the occupied West Bank, with hardline members of Netanyahu’s cabinet demanding the West Bank’s annexation in response to Australia, Canada, and the UK’s recognition of Palestine.

On 17th September, an independent UN commission of inquiry found that Israel was committing acts of genocide in Gaza. This has not been acknowledged by the Australian government, who continue to call it a ‘conflict’.

When Australia announced their intent to recognise the state of Palestine, the Australian Palestinian Advocacy Network (APAN) advised that recognition without substantive action, such as sanctions and an end to the two-way arms trade, was a “political fig leaf to deflect from the urgent legal obligations Australia must uphold”.

A recent investigation from Declassified Australia revealed that as recently as early July 2025, F-35 fighter jet parts have been exported directly to Israel.

The Israeli genocide of Palestinian’s has brutally killed an estimated 65,338 people since 7th October, 2023 at the time the statement was released. An additional 166,575 have been injured.

“From Gadigal to Gaza”: USyd students embark on protest tour around campus in solidarity with Palestine and to end the CAP

Jenna Rees reports.

On Wednesday, 17th September, Students Against War (SAW) held a Sanction Israel Protest Tour around the USyd campus. The protest tour started at the F23 building, before heading across City Road to the United States Studies Centre (USSC). From there, the protest moved to the Nanoscience Hub and ended at the Brennan MacCallum building. The tour called to end the following: student exchange with Israeli universities, partnerships with genocide profiteering weapons companies, and western imperialism by closing the USSC.

The tour, emceed by Vieve Carsnew from SAW and Solidarity, started at the F23 building. Carsnew said that “we will not be intimidated” and “USyd’s biggest concern is silencing students’ protests.” She called for the Campus Access Policy to be “completely scrapped” and claimed that USyd is “actively complicit in genocide.”

Carsnew called Angus Dermody from SAW and Solidarity, to the megaphone. Dermody made the crowd aware that “just last night, the UN released a report that concluded that Israel is committing genocide.” He said that USyd management “can’t cut a single tie with Israel” and the “famine, mass slaughter in Gaza” has to end, “no excuse[s].” He remarked that while “Israel

continues to rain down bombs on Gaza”, “we will not be initiated into silence.” He then questioned why USyd continues to send students to an “apartheid state”, referencing the exchange programs that USyd has with Technion, the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, and Tel Aviv University. Dermody also said that the USyd administration knows that “if students organise and refuse to accept [current policies] we can force them to cut ties to Israel.” Dermody declared that “it does take mass defiance.”

While walking to the USSC, Carsnew on the megaphone chanted: “Mark Scott, can’t you hear? We won’t build your weapons here” and “Sydney Uni, you can’t hide! You’re supporting genocide.”

At the USSC, Carsnew invited Grace Street, General Secretary of the SRC, to speak. Street said that USyd is a “colonial institution”, specifically referencing the “Western Civilization course.” She commented on the “gentrification in Redfern” and said that the “fight from Gadigal to Gaza, goes further every inch.” Street commented upon the USSC’s “sinister origins”, supported by Rupert Murdoch. She then mentioned the USU’s recent sponsorships of McDonald’s and Coca-Cola, both companies actively complicit in the war and genocide in Gaza. She noted that “this building

still stands to create legitimacy for western hegemony.” Street ended by saying, “two years too long? More like 77 years too long.”

The protest moved back across City Road. “Albanese, Wong and Minns, we will fight you! We will win!” was being chanted, alongside “Israel out of Palestine! Long live the Intifada.” Notably, as the protest moved along Fisher Road, behind the F23 building, USyd staff were huddled around the windows, watching on as the protest happened beneath them.

The third location of the protest tour was the USyd Nanoscience Hub, where Sargun Saluja spoke. Saluja mentioned that inside the building is the Jericho Smart Sensing Laboratory, a collaboration with the Australian Air Force, and has academic partnerships with Israel’s Bar-Ilan University. Saluja said that “USyd is chasing defence money tied to AUKUS.” After Saluja, Carsnew said once again that we “are here demanding change… demanding an end to all exchange policies”, and to “scrap USyd’s Campus Access Policy.”

From the Nanoscience Hub, the tour moved to its final location, the Brennan MacCallum building. Here, Jesper Duffy from the Queer Action Collective spoke, bringing attention to academic David Brophy. Brophy’s Palestinian flag had been hanging from the building since 2023, and only at the start of this semester was his flag confiscated under the new Flags Policy. Duffy said that this is “an attempt to silence free speech”. Noticeably now, there is a Palestinian flag hanging as well as a keffiyeh from the building window, in support of Brophy’s cause and general solidarity for Palestine.

Duffy went on to say that “the university would love nothing more than to silence the most vulnerable students,” such as queer students and those struggling with mental health. Duffy also mentioned Luna, a transgender international student from Malaysia, who USyd threatened to send home after violating the CAP. Duffy ended by encouraging everyone “to join the fight. To come in clutch for your comrades.” He concluded: “Free Palestine. Fuck Mark Scott. Fuck this university. Fuck Israel.”

Mehnaaz Hossain reports.

University of Sydney Ground staff and Protective Services are interfering in SRC elections by continuously removing campaign corflutes on campus.

From Monday 15th to Wednesday 17th September, staff have taken down eleven ‘Grassroots for SRC’ election corflutes.

In a conversation with Grassroots campaigners on Thursday 18th, Protective Services admitted that the corflutes were likely seen as “offending materials” under the University’s Campus Access Policy (CAP). All of the Grassroots corflutes mention Palestine in some capacity.

The University’s Head of Grounds confirmed that staff were specifically instructed not to touch any SRC election materials. Despite this, “a newer member of the grounds team” removed the materials “in the early morning as part of their routine hard surface cleaning”.

Routine cleaning often involves the removal of CAP-violating materials, such as unauthorised political posters and flags.

A Palestine flag was removed from University academic David Brophy’s office in early August under the new Flag Policy.

Protective Services and the Grounds team then reaffirmed their commitment to not interfere with election materials until 29th September.

Honi has received further notice that between Sunday 21st and Monday 22nd September, campus staff have continued to remove corflutes from multiple campaigns. To our knowledge, these include: 72 from ‘Queer Action’, an additional 22 from ‘Grassroots’ and ‘Free Palestine’, and multiple from ‘Impact’ and ‘Explicit’.

Honi will continue to monitor the situation throughout the election.

Vice-Chancellor

Victor Zhang reports.

The University of Sydney Senate unanimously endorsed the extension of Vice-Chancellor Mark Scott’s term in his current role. Scott’s five-year term is set to begin next July.

Chancellor David Thodey announced the extension of Scott’s term on Tuesday, 16th September. Thodey congratulated Scott in a universitywide announcement commending him “on [starting] an ambitious 10-year strategy”, making reference to the Sydney in 2032 university strategy.

The Sydney in 2032 strategy sets out aspirations for transformational education and research at USyd. The “student-focused education aspiration” is measured through USyd’s standing amongst the Group of Eight universities in the Quality

Indicators for Learning and Teaching Student Experience Survey.

The University of Sydney ranked third last in the 2023 Student Experience Survey.

Scott came under fire for his handling of the Gaza Solidarity Encampment in 2024, with pro-Palestine activist groups and civil liberties organisations condemning the subsequent response through the Campus Access Policy as heavy-handed and draconian.

Scott also faced calls for his resignation from the Australasian Union of Jewish Students for having too light a touch on the Encampment. Scott apologised for his handling of the Encampment in 2024 while under questioning at a federal senate inquiry into antisemitism.

Imogen Sabey reports.

In a change proposal released on 17th September, the University of Technology Sydney (UTS) announced plans to cut 1,100 subjects and at least 134 fulltime jobs.

On 2nd September, Safework NSW had ordered UTS to suspend job cuts, on account of “serious and imminent risk of psychological harm” to staff.

This suspension has since been lifted, allowing UTS to move forward with axing jobs. It had

previously announced that it would axe 150 academic and 250 professional staff positions.

The ABC has reported that 134 jobs will be axed, whilst the Australian Financial Review reported that at least 160 jobs will be axed.

UTS has also announced plans to shut down the School of International Studies and Education (SISE), through a proposal that would remove most of the jobs in the school.

The proposal said that the Trans-Disciplinary and Business Schools would be merged to create a unified Business and Law faculty. The total number of schools will be slashed from 24 to 15.

These changes are part of UTS’ Operation Sustainability Initiative, a plan which aims to save $100 million a year and overcome five years of deficits.

Vince Caughly, the National Tertiary Education Union

(NTEU) NSW Division Secretary, said “UTS management’s plan to close international studies and education, and public health is an abandonment of their duty to staff, students and the wider community.

“They are choosing short-term financial optics over their responsibility to deliver quality higher education.”

NTEU UTS Branch President Sarah Attfield commented “Staff worked tirelessly to unpick the

unconvincing arguments UTS management put forward for the need to save $100 million.

“We also gave viable alternatives to job and course cuts, but UTS management have dismissed our suggestions.”

As part of the change proposal, UTS will undergo a consultation period until 15th October.

Sebastien Tuzilovic reports.

Staff at the Art Gallery of NSW (AGNSW) walked out on 16th September to protest the removal of jobs at the institution, with 51 careers cut from their workforce in August. Nearly 100 staff marched at lunchtime from AGNSW to NSW State Parliament, chanting “No more cuts!” and “Art for all!” This walkout is the second since the cuts were announced, following one on 27th August. Organised by Public Service Association of NSW (PSA) members of Art Gallery staff, these walkouts are the first of their kind for AGNSW in over 10 years.

The demands of the walkout, as detailed in a PSA press release, were to “Stop the Art Attack, save the $7.5 million earmarked for cuts, protect the 51 jobs on the line, reject the NGV comparison model, and the overreliance on unpaid labour.”

The walkout comes after a restructure to AGNSW which, according to management, seeks to “stay within its budget” and “operate sustainably”.

AGNSW defended this decision, stating it must “respond to the changing environment” by “making ongoing savings and planning for the future”. The management plan was introduced after the recent announcement of Maud Page as its newly appointed director.

Both the Chief Operating Officer Hakan Harman and the Chief of Staff Michelle Raaff resigned following Page’s appointment.

The NSW Minns Labor government has also defended these cuts, referencing a state Treasury review from 2024 which found that the AGNSW’s new Naala Badu wing had caused sharp cost increases. They stated that these increases were not

covered by revenue. The 2024 review caused reconsiderations of funding, with a drop from $72 million in annual funding between 2024–2025 to a predicted $66 million between 2025–2026, nearly a 10 per cent cut.

Staff have been publicly critical of the job and funding cuts, with PSA organiser Anne Keneally stating that “These [redundancies] are not excess roles; these are not luxuries; these are the people who are the heart and soul of the gallery. They are more than a number”. PSA Assistant General Secretary Troy Wright also demanded that the cuts be halted immediately: “This is not reform — it’s a calculated attack on the people who bring this Gallery to life.”

Keneally highlighted the jobs which were axed, including

diversity and inclusion managers as well as risk and safety managers. She stated such cuts were negligent to the nature of the dangerous manual work that art installation requires.

The PSA also highlighted the enormous recent success of the AGNSW, stating that there has been a surge in visitorship since COVID of 84 per cent, and over 2.3 million visitors in the last year alone. Wright asked why this success has been “punished”, and stated that “The staff facing the axe are not sitting behind closed doors — they are curators, educators, designers, and publicfacing professionals who make the AGNSW world-class.”

Other institutions of similar cultural standing have faced financial difficulties recently.

The Museum of Contemporary Art (MCA) reported a 2024

operating loss of $2.1 million, which caused director Lorainne Tarabay to indicate that continued austerity measures would need to be furthered. She asserted that “the level of public service that the MCA provides is not sustainable at current funding levels”. Create NSW’s funding has also been recently slashed in June by 25 per cent, with its 91 staff members now in jeopardy of job loss themselves.

The AGNSW walkout represents an attempt by the workers of these cultural institutions to strike back at measures which are stripping them of their livelihoods, and depriving the people of Sydney their arts and cultural spaces that are so treasured and vital.

AGNSW were asked for comment about the walkouts, but did not respond.

Imogen Sabey reports.

On Thursday 11th September, University of Melbourne’s (UniMelb) student magazine Farrago celebrated its 100th birthday in a centenary gala, hosted at the Trades Hall.

The gala was attended by over 160 people, including current Farrago editors, contributors, and readers, as well as Farrago and UniMelb alumni.

Farrago is the oldest student publication in Australia, having been founded in 1925 at UniMelb, originally as a weekly newspaper.

The event began with editors acknowledging the local Wurundjeri Woi Wurrung people and the Kulin Country on

which the gala was taking place.

Farrago Editor Mathilda Stewart spoke about the necessity of student media to report on threats to campus free speech, particularly concerning protests against the genocide in Gaza.

Stewart said “I know that student journalism matters when professional publications do cover campus affairs and they do not report the truth, they spread disinformation and too willingly take statements from the university at their word.

“The genocide in Gaza, the destruction of universities, the targetted killing of over 275 journalists, all of this has been conducted with the effective support

of the University of Melbourne — who have been ruthless in their attempts to repress students and staff and evade accountability.

“In another hundred years, I have no doubt the University will be busy marketing our historic resistance as the appeal of a counter-cultural campus life, and I hope that Farrago will still be here to document the truth and tell students’ stories.”

Ibrahim Muan Abdulla, another Farrago editor, spoke about his experience working as a journalist in the Maldives and feelings of isolation and fear that he experienced reporting in unsafe journalistic conditions.

Abdulla said “To be in those moments, feeling the pressure

of history and the risks that came with telling the truth, was terrifying.

“It was frightening work — often isolating, occasionally unsafe — but it planted in me a conviction that has only deepened: we don’t do journalism because it’s easy; we do it because truth has consequences.”

Mandy Li, an editor of Lot’s Wife (the Monash University student magazine), said to Honi “Farrago is and always has been a powerhouse: 100 years of Farrago means 100 years of student-led, student focused journalism, art, and news.

“Having done the Lot’s Wife 60th anniversary last year, it’s always amazing to speak to past

editors and contributors, and to see the Farrago community, and the broader student media community, thrive. To another 100!”

As part of its centenary celebrations Farrago is hosting an exhibition titled ‘Farrago 100: Showcasing a Century of Student Media’ from 18th September to 10th October. The exhibition is being held at the George Paton Gallery in Melbourne.

According to organisers, the exhibition “displays archival material and contemporary responses to its publication, considering Farrago’s place and purpose in the cultural ecosystem over ten decades of [publishing].”

Honi Soit reports.

The first in-person Honi debate since 2019 did not disappoint. Burn for Honi were represented in the debate by Madison Burland and Anastasia Dale. Flash for Honi were represented in the debate by Sath Balasuriya and Jessica Louise Smith. The debate was moderated by current Honi editors Mehnaaz Hossain and Victor Zhang. Flash deployed an easygoing, playful attitude in their interview that worked well in the room but did not translate particularly well to this debate. Burn, on the other hand, were composed and consistently articulate, having clearly prepared substantially beforehand.

In their opening statement, Balasuriya described the current state of student journalism as “creaky and complacent” with “stories that fail to live up to what student journalism is really about, [which is] reporting by students for students”. They claimed that Flash would “bring student journalism back to its irreverent and unabashedly critical heyday”. Dale presented Burn’s opening statement, saying “it is deeply important to us to maintain Honi’s radical left-wing stance in light of NTEU [National Tertiary Education Union] enterprise bargaining [next year]”. Dale said that during the 2026 NTEU enterprise bargaining agreement (EBA), Burn would provide “reports on strikes, disputes, developments… every day”. Dale added “To us, this isn’t about winning, it’s about reinvigorating the paper we love.”

Flash attempted to spin their relative inexperience as a

strength, which did not entirely hold up to scrutiny. Dale replied that, excluding co-written articles, “you have two members that have [independently] written three or fewer articles”, all from this semester. Flash attempted to rebut with the point that their first-year members could not have written last year, to which Burn responded that “they had all year to write.”

Both teams committed in their policies and interviews to expand on multimedia, a triedand-failed policy of many Honi tickets past. Burn described aims of producing “highlight reels” for events such as SRC Council and protests by training editors on content creation, while Flash said they have ticket members with backgrounds working in social media, spoke to Smith’s video protest coverage, and aimed to have an editor primarily responsible for multimedia. When grilled on the necessary time and energy trade-off when balancing multimedia with the print newspaper and other Honi commitments, neither team were willing to fully acknowledge the inevitable trade-off and de/ prioritisation of written content over multimedia.

In terms of politics, Flash described themselves as “left libertarian” in the Honi interview. When pressed on what this meant, they frequently referred to themselves as “left-leaning” but staunchly unaffiliated with any factions or parties. Vince Tafea (Grassroots) asked Flash to clarify what they meant by “free from internal political agendas” making reference to current and past tickets having editors hailing from various political factions.

Smith responded stating that Flash as a “left-leaning ticket” and their independence from factions allowed them “to take perspectives without fully indoctrinating yourself into an ideology”. However, it seemed their desire to divorce themselves from any political attachment divorced them from the ability to clearly articulate their political beliefs.

Burn criticised Flash for being indirectly affiliated with Labor, through Smith’s former campaign manager Alex Poirier, who in 2024 ran an Artistry for SRC ticket affiliated with Labor Right that had endorsed Angus Fisher’s SRC presidential bid. In response, Smith chose to distance herself from her former faction’s connection to Labor Right. Flash were not able to identify that Burn’s campaign manager, Layla Wang, ran a USU campaign backed by Alex Poirier. As Tafea previously stated, in recent memory, Honi editorial teams have all had editors with some form of connection to political factions on campus.

Hossain grilled Burn on their commitment to publishing “articles which start dialogue”, given their refusal to defend ticket member Ramla Khalid’s discourse about sex work and its structural nuances. Despite the specific and targeted question, Burn had a confident and clear answer, referring to the lived experience of ticket members as sex workers and the need for nuance and community consultation. Whilst this would have been preferable to articulate in the interview, this response was well-composed and provided insight into Burn’s reasoning.

Flash were thrown a similar hardball question when interrogated on what the advertised diversity on their ticket achieves beyond “mere identity politics”, given most recent Honi tickets are fairly racially diverse and queer. They responded well, clearly outlining their unique plans for the first ever International Students Collective autonomous edition, as well as explaining the importance and necessity of international student voices.

The teams were asked to subedit two unseen news articles during the break. Overall, both teams performed well, picking up on many of the same errors, including the need to italicise legislation, and hyphenate the age adjectival. Neither team picked up on the obvious first sentence misspelling of Labor (“Labour Party”). Notably, both teams failed to correct all hyphens to em dashes.

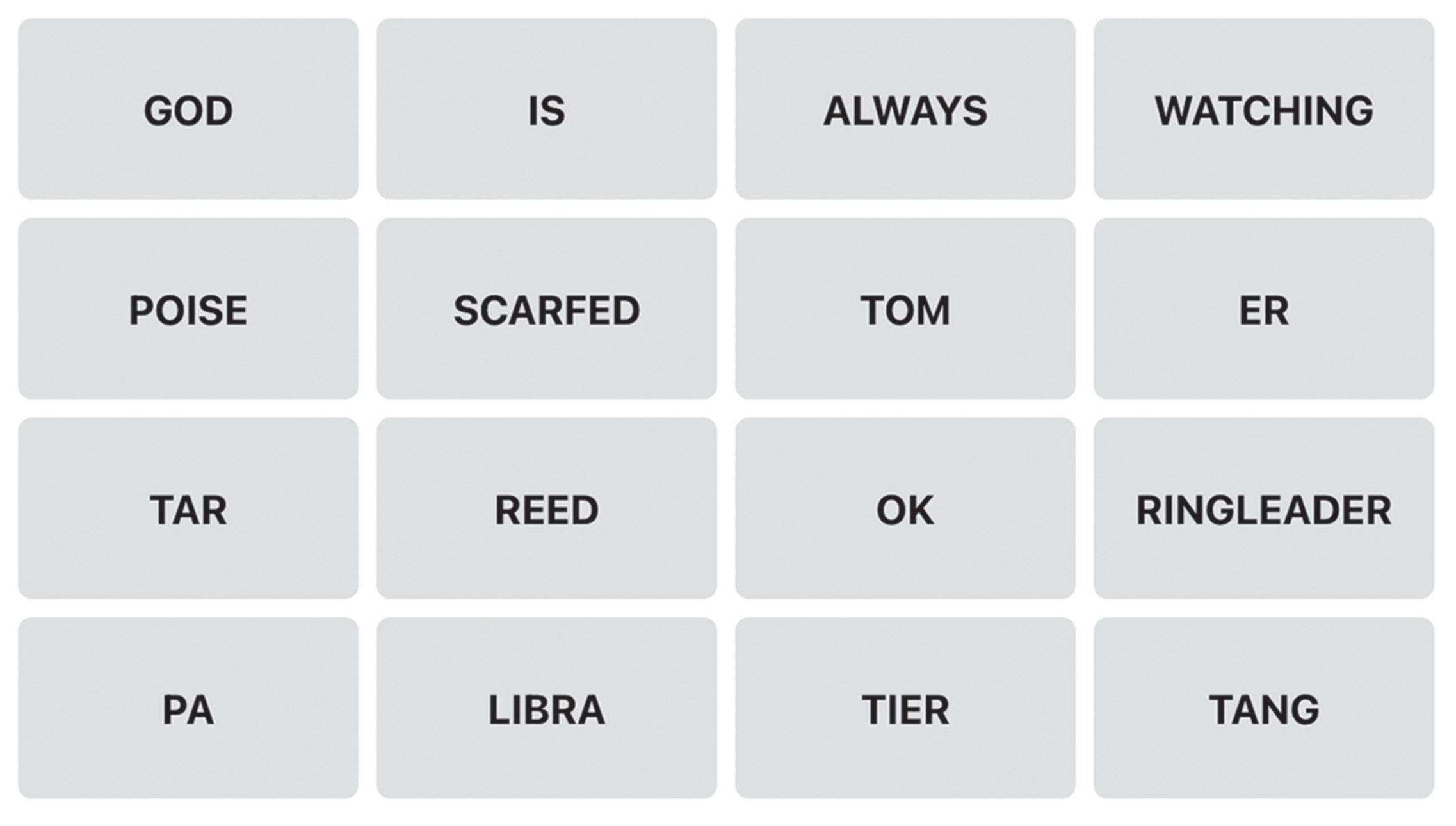

Jo Moran (SLS), as an avid enjoyer of the puzzles section, queried both teams on their vision for the puzzles page. Smith affirmed that the general love for the puzzles page and a desire to continue it. Dale expressed an interest in “New York Times games like Connections and Wordle.”

In Burn’s closing statement, they reiterated their credentials and vision, stating “This is something that we care about. This is something that we feel we are well equipped to do. We are up for the challenge.” They addressed their commitment to “radical reporting with lived experience and political reading as our backing”, which was substantiated by their well-

articulated responses and debate performance.

In their closing statement, Flash spoke about accessibility as people who “understand what it means to be…outside of factional circles” and emphasised that “Since the start of semester two, we have been in every single issue”. Almost the entire ticket has been in every single issue.” However, they then took an ill-judged potshot at Burn member Kiah Nanavati for not responding to a request for comment. Nanavati, who was in the crowd and not participating in the debate, said that Flash were not entitled to her response. Flash’s outburst came off as petty, unstrategic, and poorlytimed.

Overall, both teams put up an admirable debate performance. Flash displayed solid institutional knowledge in the quiz and interview, as well as a strong writing record this year, but were unable to sufficiently articulate their politics, maintain a strategy, or rebut concern about their lack of overall experience. Burn performed worse on the quiz and lacked as much current engagement this year, but confidently and strategically responded to concerns and were successfully able to clearly articulate their politics and vision for Honi.

Lastly, and most importantly, when queried about whether the teams were worried about the 11th-hour mystery contender Mop4Honi, Burn responded “we saw that beautiful illustration and got really nervous” while Flash said that they “were very scared. [Mop4Honi] is kind of like Batman.”

Charlotte Saker investigates.

Who will I complain to? Who will listen?

My own family will not listen; they are my enemies.

The satin maroon bridal dress has come, Laid out like a sheet over a coffin of the deceased.

The jewelry lay out as if I were sold.

Yes, cold for the price of my freedom.

Excerpt from ‘To be forced into arranged marriage’ by South Sudanese woman Chany Nindrew.

Slavery remains one of humanity’s greatest injustices; a system by which countless lives have been reduced to property bought and sold. Its most notorious form, the transatlantic slave trade of the 18th and 19th centuries, saw European authorities forcibly transport millions of African people across oceans into bondage.

Although formally abolished in the 19th century, slavery remains, though

transformed. What was once a public and legal institution has adapted into modern slavery, an illegal system that operates in private and is thus heavily overlooked. Among its most common manifestations today is forced marriage, particularly impacting young women, girls, and students. Defined in international law as a “slavery-like practice,” forced marriage reduces a person to the status of property, stripping them of free and full consent while subjecting them to ownership, control, and coercion under the guise of marriage.

Director of the University of Sydney’s Master of Social Justice program, Associate Professor Susan Banki, defines forced marriage as “a situation where the person who has become a victim of forced marriage is in a relationship that contractually makes them a spouse for reasons that are anything less than voluntary. The pressures that create this less than voluntary arrangement may be physical, economic, social, or religious. In almost all cases, they are structural.”

The distinction between forced marriage and arranged marriage is vital to understand. The latter involves partners who give full, free consent, even if families may broker introductions. Arranged marriage is legal, where forced marriage is not. Confusing the two fuels damaging misconceptions and stereotypes that forced marriages are a ‘cultural’ practice,

confined to migrant, ethnic, and religious groups, when this is not the case.

The issue is structural, and Western countries like Australia are only now beginning to grapple with it. As the study ‘Not the Usual Suspects,’ by E-International Relations puts it, forced marriage remains “an ill-defined, and even worse understood concept.” It is not confined to one faith or ethnicity, but cuts across jurisdictions and social systems, leaving women and girls “lost within and between legal systems.” Forced marriage “has a wide variety of forms” and is best understood as “a multi-faceted and multilayered dilemma involving law, politics, and international relations.”

Structural and legal blind spots falsely reduce the perception of the problem’s scale. Globally, an estimated 22 million people are living in situations of forced marriage on any given day, according to human rights group Walk Free, with women and girls making up nearly threequarters of this figure.

Australia is not immune. Forced marriage was only recognised as a crime in Australia in 2013, through amendments to the Criminal Code Act 1995. Prior, some elements of coercion could be prosecuted under trafficking, assault, or domestic violence laws, but there was no specific offence that reflected the reality of forced marriage.

Since then, in 2019, the Australian Institute of Criminology noted that forced marriage has become the most commonly reported modern slavery offence referred to the Australian Federal Police (AFP). Yet the numbers remain small compared to the likely reality: 69 referrals in 2015-16, rising to 91 by 2018-19, and again 91 in 2023-24. Authorities admit that for every detected case, several more go unreported, generally hidden due to family loyalty, stigma, or fear of authorities.

The clear common factor for all victim-survivors is that those who choose or attempt to resist forced marriage may face estrangement from family and community. Forced marriage can occur with or without violence; it can involve sexual assault, forced pregnancy, or domestic servitude. Other times it relies on quieter but equally destructive forms of coercion such as shame, honour, financial threats, or migration status.

The delay in criminalisation is due to years of dismissing forced marriage cases as either too rare to warrant legislation or as something that only happens “elsewhere.” A 2011 federal discussion paper acknowledged widespread underreporting but still framed forced marriage largely as a by-product of migration, rather than as a violation of human rights in its own right. As a result, Australia lags behind international commitments like the UN Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW), which has long required states to outlaw child and forced marriage. The question centres on whether it is family violence, a migration issue, or trafficking offence. That uncertainty, combined with cultural stereotypes that cast it as a ‘migrant problem’ means the law lagged years behind the reality.

Forced marriage is not tied to any one culture or migrant group, but arises wherever conservatism and patriarchy combine with structural vulnerability. As the E-International Relations study observed, casting forced marriage as a ‘migrant problem’ obscures the reality that it is a multi-layered dilemma involving law, politics, and social structures, and that it occurs across many communities. Chloe Saker, lawyer at Anti-Slavery Australia and My Blue Sky, says “there is a tendency to assume forced marriage is more common amongst particular migrant communities. But we see people affected across a range of communities. Generally, if a family is more conservative or patriarchal in nature, there may be more of a risk but our casework shows it is not possible to single out a particular group.”

Since its decriminalisation in 2013, gaps in the law remain. Victim-survivors who come forward can face investigations that criminalise their own families, making disclosure fraught. Legal remedies do not always align with the needs of students or young people, who may be seeking safety and support rather than prosecution. Chloe Saker explains that Anti-Slavery Australia and their forced marriage service, My Blue Sky, provides free, confidential legal advice around safety and protection, divorce, migration, accessing family mediation services and referral to the Additional Referral Pathway or the Forced Marriage Specialist Support Program. These services, to be elaborated on, are available to any person affected by forced marriage in Australia, including Australian residents who may have been taken overseas in connection with a forced marriage.

The wide spectrum of forced marriage, from subtle family pressure to outright coercion, makes the problem harder to confront through law alone. Forced marriage can look very different across contexts, from whispered family pressure to outright coercion, which has long slipped through the cracks of criminal justice.

It was not until July 2024, more than a

decade after forced marriage was criminalised, that Australia recorded its first conviction. In Shepparton, Victoria, 48-year-old Hazara-Muslim woman Sakina Muhammad Jan was sentenced to three years in prison, with at least 12 months to be served, for coercing her 20 year old daughter, Ruqia Haidari, into marrying Mohammad Ali Halimi. Six weeks after the wedding, Halimi murdered Ruqia in their Perth home.

Jan’s case, while the first successful conviction under Australia’s forced marriage laws, also revealed the limits of criminalisation. Reports from the trial noted that Jan did not believe she had done anything wrong. Having been coerced into marriage herself as a teenager, she carried her own history of trauma and appeared to regard marriage as the only legitimate pathway for her daughter. The sentence punished her, but it did little to confront the intergenerational patterns and patriarchal structures that enabled the coercion in the first place.

Ordinarily, in Hazara culture in Afghanistan, unrelated men and women have very little

social interaction outside family networks. As the court noted, one way around this restriction is the practice of a temporary Nikah, an Islamic marriage contract that legitimises interaction and, implicitly, sexual intimacy.

While intended to allow young people to get to know one another, these arrangements can carry serious consequences for women if they end. A divorced woman, or bewa, is often perceived as diminished in value, a status that reflects not only on her but also on her family’s reputation. In this case, the marriage of Haidari was shaped by a web of expectations around honour and reputation. Justice Tinney states that Ruqia Haidari resisted the marriage and that Jan was “made aware of her wish not to marry Halimi at that time.” In essence, coercion does not exist as an isolated act of parental control but as a product of patriarchal pressures.

The paradox of criminalisation means that while the law rightly condemns forced marriage, punitive measures alone cannot shift deeply entrenched attitudes. Advocates warn that an overreliance on prosecution risks deterring young people from seeking support if they fear their parents will end up in prison. Nesreen Bottriell, CEO of the Australian Muslim Women’s Centre for Human Rights, told ABC Radio: “Education needs to be the priority.”

This case also highlights the gaps in Australia’s support systems. In the case of family violence, victims can access established networks of shelters, counsellors, and risk-management protocols. Forced marriage, by contrast, is often funnelled through Home Affairs and the criminal justice system, where the focus is on securing convictions rather than managing longterm safety. Young people, particularly those aged 15 to 17, who make up a significant share of cases, are not a priority cohort for child protection and are frequently left with no safe options except returning home.

Hence, as Bottriel stated, prosecution is necessary, but it cannot stand alone. Only community-level engagement, coupled with systemic support for victims, can dismantle the structural forces of patriarchy, inequality, migration barriers, and intergenerational trauma that make young people vulnerable in the first place.

Nevertheless, there have been increased efforts to better support victims. The Australian Government introduced the Additional Referral Pathway (ARP) in July 2024. Led by the Salvation Army, ARP provides a new and direct route for victims of modern slavery to access free and confidential support from nongovernmental organisations without going through law enforcement first. The initiative was designed to bypass barriers that deter victim-survivors from seeking help, particularly the fear that disclosing a forced marriage could lead to their family members being prosecuted.

Alongside ARP, organisations such as Life Without Barriers (LWB) have been central in supporting those at risk of or affected by forced marriage. LWB delivers the Forced Marriage Specialist Support Program (FMSPP) which commenced on 2 January 2025. It is the first national program dedicated solely to assisting victim-survivors of forced marriage. The program builds on earlier initiatives like the Support for Trafficked People Program (STPP), established in 2004, which offered support for up to 200 days, including 90 days on the Intensive Support Stream. The STPP

now directs victims to the FMSSP, which is not time-limited, ensuring survivors can continue receiving assistance for as long as necessary. Following on from the STPP, the program provides counselling, education, migration advice and helps survivors navigate access to housing.

Panos Massouris, Director of the Forced Marriage Support Program at LWB, told the ABC that because “forced marriage is under the Commonwealth Act, many child protection services are not eligible for statebased domestic violence services or shelters.” Instead, the organisation carries these services out themselves, supporting people with living allowance, job seeking and education. “It’s based around where they are at and what they need,” Massouris said. Currently, their data shows that more than 40 per cent of clients supported are Australian citizens, not recent migrants, and clients range in age from 15 through to over 50, spanning more than 20 different countries of birth.

Ultimately, LWB’s’ frontline experience highlights that forced marriage cannot be dismissed as a ‘private’ family matter. Like domestic violence, it exposes how the supposedly private sphere of the home is deeply political, as a site where control, coercion, and structural inequality play out. By framing forced marriage as both modern slavery and family violence, organisations like LWB make it clear that community-level education and systemic funding are essential. The patterns of coercion they encounter, across the board from young students to older women, reinforce that this is a problem shaped by patriarchy and structural vulnerabilities rather than culture alone.

Today, around 37 per cent of victims are aged 18-25, and another 26 per cent are under 18. In other words, more than six in ten people affected are under 25, the same age bracket that fills Australia’s lecture theatres and campuses.

Yet, the prevalence of forced marriage among students is often overlooked, dismissed as a private or family issue, or ignored due to lack of awareness about one's rights.

For students, coercion into marriage rarely looks the same. At one end are subtle comments and reminders about “getting older” or “needing to settle down.” At the other, are explicit threats of violence, or ultimatums tied to money, visas, or family reputation. For universities, the issue of forced marriage is not abstract. Campuses are often the first place students disclose what they are going through. “In the university setting, there is a spectrum of pressure, coercion and control that students and young people face by their communities or by their families” Saker says.

financial precarity, visa reliance, language barriers, and limited awareness of their rights. By offering more flexible payment plans, emergency bursaries, or hardship loans that bypass parental control, universities could reduce this leverage. For example, a student whose tuition is paid directly by parents may feel unable to resist family pressure, but if universities provided confidential avenues for alternative funding, it can offer greater agency over decisions.

However, financial stress does not just affect international students. Domestic students who rely on family for accommodation or support are also vulnerable if those resources are threatened. Flexible arrangements from universities, including tuition extensions, emergency housing, and confidential wellbeing referrals, could provide lifelines that make resistance possible. Without them, students may see marriage as the only way to secure continued stability.

forced marriage is unlawful in Australia, or that it is a form of modern slavery. Sometimes people think this is only a private family matter or that it only affects certain communities.”

Forced marriages are not a private problem, but a structural injustice that thrives in the shadows.

Often, the trigger is behaviour seen as “shameful”. “If a student is dating someone their parents do not approve of, are dating at all, or are having sex before marriage, a forced marriage with a partner chosen by the family might be a way to conceal that behaviour or to restore honour,” Saker says. In conservative households, especially where students are seen as having become ‘too Westernised’ by university and independent life in Australia, a forced marriage may be imposed to reassert control. “Students can feel stuck between those two worlds,” she adds, “between their personal desires to pursue their education, their career and independence, versus the fear of losing their family or bringing shame to them.”

This pressure also manifests amongst other minority groups, like LGBTQIA+ communities.

“If a student is dating someone their parents do not approve of, [or] are dating at all, a forced marriage with a partner chosen by the family might be a way to conceal that behaviour or to restore honour.”

For international students, the risks are even greater. Paying tuition fees often twice that of domestic peers, many rely entirely on family for financial support. That dependence can become leverage, with families threatening to withdraw funding unless a student accepts a marriage arrangement. Visa status is another pressure point: a student whose residency depends on their parents may see little choice but to comply. The 2023 Universities Accord Interim Report flagged these risks, warning that international students face heightened exposure to modern slavery, including forced marriage, due to

“LGBTQIA+ students may be forced into heterosexual marriages as a means to control their gender and sexuality, which may be perceived as shameful by their families,” Saker says.

The question then becomes: what can institutions do to protect and support those most at risk?

Universities sit at the front line; young people, often still dependent on their families, make up a disproportionate share of those affected by forced marriage. As the University of Sydney acknowledged in its 2023 Modern Slavery Statement, “we take the global issue of modern slavery very seriously and make considerable effort to address and prevent issues that are reported to us.” University Spokesperson, Provost Professor Annamarie Jagose, confirmed the University received three reports that year showing indicators of possible forced marriage, with students referred to specialised support through its Safer Communities Office.

Universities, then, are often the first line of support. But awareness and preparedness remain patchy. “There are still misconceptions,” Saker explains, “[such as] not knowing that

Through the Safer Communities Office or the Student Wellbeing service at the University of Sydney, these units can connect students with legal specialists at My Blue Sky. However, considering that staff and counsellors are often the first to hear disclosures, Saker stresses that much more should be done. Training staff to recognise the warning signs, starting conversations with students about consent and rights in marriage, and addressing harmful stereotypes that obscure reality, are all crucial steps to preventing this form of modern slavery. Universities are also urged to offer more support to students affected by forced marriage particularly where they are experiencing financial stress, mental health issues or struggling to manage study loads. “There is more work that universities can do as institutions, especially at the initial stages, when students are at risk but don’t know who to talk to, where they can seek professional help or are worried about how seeking help might affect their studies,” she says.

Forced marriages are not a private problem, but a structural injustice that thrives in the shadows. Criminalisation is progress, but law alone cannot shift entrenched norms. Education, awareness, and strong support systems — especially in universities where many young people are at risk — are essential. As long as coercion is mistaken for consent, too many young people will remain trapped between family expectation and their own right to choose.

I leave you with another excerpt from Nindrew’s haunting poem, to remind you of what is at stake: autonomy, dignity, and the right to freedom.

If I accept this man as my husband; I am quiet, I cannot think.

I have no choice; the poison is near.

Just one drop, then two I am now in another world away from hurt; away from deceit

I am in a place of being looked after and loved.

I am with the angels; the hurt has ceased, I am now in total peace.

Gabriel Jessop-Smith is interconnected.

The emergence of the environmental movement in the 1960s saw a significant change in human attitudes towards nature and the earth. Within a very short span of time, it became apparent to the public that human activity was posing a critical danger to the planet. A new era began, characterised by an anxiety over massive resource depletion, species extinction, and pollution overload. This anxiety grew alongside an awareness that the world was an increasingly interdependent, single globe. In 1968, the Apollo 8 astronaut William Anders took an image of the earth from space. He called it Earthrise. A radically new perspective on the planet, Earthrise has been considered by some to mark the beginning of the environmental movement.

In the face of looming environmental disaster, some began to question old perspectives on the earth. Under what assumptions had the human community perpetrated this level of planetary danger? For one, it seemed that the veneration of science and technology, along with the ideology of progress, had ironically brought the human species toward a catastrophic precipice. Humanity lived in the shadow of the atomic bomb —-- a revelation of the terrible possibilities of science. In a 1967 edition of the academic journal Science, historian Lynne White put forward the suggestion that the contemporary ills of science and technology had roots in the Judeo-Christian tradition. White believed that science and technology had adopted from Christianity the habit for the domination of nature.

White argued that Judaism and Christianity had established a conceptual dualism between nature and humanity. In this view, people were seen as masters, not members, of the natural world. According to White, this view stipulates that “God planned all of creation explicitly for man’s benefits and rule”. White’s conclusion was that “Christianity is the most anthropocentric [human privileging] religion the world has seen.” One needed to look no further than the first few lines of the Book of Genesis, wherein God commands humankind to “fill the earth and subdue it; and have dominion over the fish of the sea and over the birds of the air and over every living thing that moves up on the earth.” In time, science had adopted this attitude of dominating and controlling nature.

towards it. For example, the Judeo-Christian division between “nature” and “people” continues to shape our tacit assumptions about the world and our place in it. This is evident in the way we characterise “nature” (as in everything that exists) as “Nature” (as in birds, trees, rivers, etc). For those of us who live in cities, we go “out” into “nature” for short periods, usually to “touch grass.” Then we come back “in” to our urban environments: artificially constructed places which are distinct from the natural world. For many of us, “Nature” has become an idealised object that appears in the form of images or videos on computer and phone screens; beautiful forests or endangered whale species.

most part, green Buddhism involves new interpretations of Buddhist teachings which can support or stimulate secular understandings of environmental thought.

One example of this is the Buddhist concept of “interdependence.” In this context, Buddhist interdependence represents the world as a vast, interconnected web of internally related beings. This Buddhist concept is often compared to other systems of interconnection, such as biological systems or communication networks. Contemporary notions of the world through the concept of interdependence, unlike the Christian concept of lapsarianism, are often characterised by a celebration of the world; of life and its intimacy, complexity, and interwovenness. Such a view comes with an ethical imperative: since humans are a part of this web, they should be considerate of their place in it, caring for and rejoicing in the existence of other beings, such as animals, plants, and even rivers.

This desire to develop new relationships to the earth is clearly borne from an anxious global search for a path out of impending climate disaster. The question is, does the human community need to reframe its place on earth in order to enact change? According to The People’s Climate Vote (2024), the world’s largest standalone public opinion survey on climate change, 89 per cent of the world’s population want stronger climate action from their governments. Despite this, government-driven climate action is negligible. In many cases, such as the current Trump administration, it is even being scaled back. What does the human community need to really change the environmental crisis?

Human belief and practice affect the earth. All beliefs, not just religious ones, become an effective part of ecological systems. They generate the power of human will and channel the forces of labour toward particular transformations of the world. As Lynn White Jr. wrote in 1967, “what people do about their ecology depends on what they think about themselves in relation to things around them.” What then, do we think about our relationship to the world around us? I pose this question to you, the readers of this paper. What do you believe to be your place in the immediate world

White’s article attracted controversy following its publication in 1967. Was it right to blame JudeoChristianity and ‘the West’ for the looming environmental destruction? Other scholars pointed out that the growth of modern Western science would not have been possible without extensive influence from India, China, and the Arab world, and it was clear that White’s implication that ‘progress’ was absent from the worlds of Asia and the preChristian Mediterranean was problematic. The historian Yi-Fu Tuan tersely pointed out in 1968 that Asian and other ancient cultures were just as prone to destroy their natural environments as the Christian West.

Regardless of who, or what, was ultimately more responsible for the growing environmental disaster, the underlying notion of White’s thesis remains potent. White was explaining that “what people do about their ecology depends on what they think about themselves in relation to things around them. Human ecology is deeply conditioned by beliefs about our nature and destiny — that is, by religion.”

In short, what humans believe about the world shapes what they do to it.

How we conceptualise the world defines our actions

original state created by God. This belief in a ‘fallen’ world is otherwise known as lapsarianism (from the Latin lapsus, “a slipping and falling”). If the world is ‘fallen’, then the world is not worth caring for; there is a better world coming.

In the search for ways to reevaluate human-nature relationships, other religious worldviews have been considered. One popular discourse is the idea of Buddhism as ‘science friendly.’ In the West, Buddhism is often considered a ‘non-theistic’ religion, meaning, it does not revolve around the worship of a creator god. Buddhism is seen rather as a ‘philosophy’ that is available to all; eschewing the traditional authority commonly found in other religions. For similar reasons it has been presented as friendly to the natural sciences; fundamentally grounded in empiricism, rationality, and scepticism.

For example, certain concepts from traditional Buddhism have been interpreted as complementing ecological science. This relatively new idea, sometimes called ‘green Buddhism,’ reflects a search for Buddhist doctrines and practices that exhibit ‘environmental’ qualities. For the

Our immediate world involves everything: our lunch today, the shoes we wear, the phone in our pocket; as well as the trees, the air, and the rain. According to the Buddhist concept of interdependence, each of these things and all beings join humans in impacting the web of life that constitutes reality as we know and feel it. With no concept of our place within this ecological community, no grounded imperative to improve human and non-human relationships, and with no universal conceptualisation of an environmental future, what chance do we have at establishing healthy planetary relationships?

Ecological consciousness goes beyond anxiety about the environmental future. Ecological consciousness does not mean staying up to date with frightening headlines online. We need to reawaken to our very ways of being; that is, we must become alive to the significance of the relationships which constantly surround us, and indeed constitute us. Here in our own homes, schools, places of work, and places of leisure. We need to do this both as individuals and as communities. In this, religion may yet play a vital role in shaping our ecological future.

Ananya Thirumalai absolves you of your sins.

If Christianity’s fall was one bite of fruit, Hinduism’s fall was an entire social order. Where Genesis imagines a single moment of disobedience that corrupts the world, Hinduism’s corruption is structural: caste. It is the framework itself, a design that fractures community while masquerading as sacred truth.

The concept of a “fallen world” describes a rupture from divine unity, an inheritance of brokenness. In Catholicism, this takes the form of original sin, an unavoidable condition said to stain all of humanity. In Hinduism, caste performs the same role. Despite lofty claims of oneness — that all souls are bound by atman (the self) and dissolved into Brahman (the universe, ultimate reality) — Hinduism encoded division into its most enduring laws. The Manusmriti (central text in Hindu legal-religious tradition) sanctified hierarchy, elevating some as gods’ mouthpieces and condemning others to eternal servitude.

To call caste Hinduism’s “original sin” is not metaphorical excess. It is the clearest example of a faith that betrays its own ideals. And unlike Adam and Eve’s bite, there was no fall from grace, only the grace of unity lost at the foundation.

Hindu philosophy, at least in its most idealised form, is obsessed with unity. From the Upanishads (final part of the Vedas, India’s oldest sacred texts) to contemporary spiritual discourse, the refrain is the same: all beings are manifestations of the same divine essence, the self (atman) dissolves into the universal (Brahman), and difference is only an illusion (maya). It is a vision of oneness so expansive that even the boundaries between life and death, human and animal, self and world are said to blur into a single cosmic order.

separation as destiny. In this way, colonial rule preserved Hinduism’s fall while making it even less escapable.

Resistance to this order was fiercest from those crushed by it. B.R. Ambedkar, born into a Dalit family, argued that Hinduism was beyond redemption. “You cannot build anything on the foundations of caste,” he declared, “you cannot reform it. You can only destroy it.” For Ambedkar, annihilating caste meant annihilating Hinduism itself. To remain within the faith was to remain within the fall. This historical arc shows that caste was born in myth, crystallised in scripture, and reinforced by colonial power. Caste is the foundation.

If caste was myth in the Vedas and law under the British, it remains blood and bone in contemporary India. The violence is both spectacular and ordinary: Dalits lynched for skinning dead cattle, stripped and beaten for sitting on “upper-caste” wedding chairs, murdered for daring to fall in love across caste lines. These stories break through the news cycle every few days because they are constant.

Universities, which should be spaces of emancipation, often become sites of suffocation.

If Christianity’s fall was one bite of fruit, Hinduism’s fall was an entire social order.

And yet, at the very moment Hinduism claims to erase difference, it enforces it with violence. The Manusmriti and other Dharmashastras (central texts in Hindu legalreligious tradition) canonised this violence as sacred law. The hierarchy of varna and jati (caste), the endless subdivisions of purity and pollution, were elevated to the status of divine truth. It is a ridiculous paradox: a religion that insists all distinctions are false, except the one distinction that matters most. Here lies Hinduism’s philosophical wound: its vision of unity is permanently fractured by the very system it sanctifies. What was meant to dissolve hierarchy instead ossified it, leaving a faith that cannot live up to its own ideals.

If Hinduism’s philosophical contradiction is unity undone by hierarchy, its history is how that contradiction became embedded in every layer of social life. The early Vedic hymns hinted at division in the Purusha Sukta (hymn in the Rig Veda), the myth where cosmic man’s body is dismembered into castes: Brahmins (priests) from the mouth, Kshatriyas (warriors, rulers) from the arms, Vaishyas (merchants, farmers) from the thighs, Shudras (servants, labourers) from the feet. What began as symbolic metaphor hardened into the blueprint for social order. The Manusmriti and other Dharmashastras translated this myth into law, prescribing duties, restrictions, and punishments for each caste, sanctifying inequality as divine command.

Colonialism further calcified caste. British administrators, obsessed with classification, used censuses and legal codes to “fix” fluid social identities into rigid categories. Communities that once negotiated caste boundaries found themselves locked into permanent boxes. Colonial modernity clothed caste in new garments — law, bureaucracy, census tables — but the logic was the same:

The suicide of Rohith Vemula in 2016 — his haunting note describing a life reduced to a “fatal accident” — was not an isolated tragedy but an indictment of caste’s persistence in Indian higher education. Dalit and Bahujan students face systemic barriers, from underfunded scholarships to hostile faculty, their intellectual contributions dismissed as “quota candidates” rather than scholars.

The fall, then, is alive, evolving, and embedded in the very institutions that claim to transcend it.

It does not stop at India’s borders. Caste migrates with people, tucked into surnames, temple committees, and WhatsApp groups. In Silicon Valley, the Cisco lawsuit made headlines when a Dalit engineer alleged castebased discrimination by his Indian managers. But beyond the courtrooms, these hierarchies structure who gets mentored, who gets invited home for dinner, who is considered “one of us.”

in 1956, alongside half a million followers, was both protest and exodus: if Hinduism could not be annihilated from within, it would be abandoned from without. Many Dalits since have followed his path, seeking spiritual belonging elsewhere rather than continuing to live inside the wound.

The contrast with Christianity is instructive. Original sin is framed as universal, but so too is the promise of salvation. Hinduism’s original sin, caste, offers no such redemption. Its victims are not guaranteed deliverance; its beneficiaries rarely repent. The system survives precisely because it insists on permanence. So we are left with a brutal question: if caste is Hinduism’s original sin, why do we still call it a religion of peace? Perhaps redemption lies not in return, but in collapse — in building a new world outside the fall.

Unlike the Fall of Man, there was no Eden to long for, no paradise lost — only a world built already broken, its fractures declared holy. If Christianity’s story offers redemption through grace, Hinduism’s inheritance of caste offers none. The promise of unity collapses under the weight of hierarchy; the dream of oneness is betrayed by a system that denies it at every turn.

The question carried the weight of centuries, collapsing oceans and borders to remind me that the fall is portable.

In Australia, I was reminded of caste’s endurance almost immediately. One of the first questions I was asked by Indian students here was not about my course, my hometown, or my favourite food, but my caste. It was delivered casually, like small talk, an assumption that I would know my place and declare it. The question carried the weight of centuries, collapsing oceans and borders to remind me that the fall is portable.

If caste has followed us across oceans, the question becomes: can it ever be undone? Is Hinduism capable of redemption, or is it condemned to its fall? Reformists often argue that caste is not “true Hinduism,” that it is a distortion layered over a fundamentally egalitarian faith. They point to verses about unity, to bhakti poets who preached devotion over hierarchy, to modern gurus who insist that “all are one.” This is Hinduism’s promise of self-correction: that the original sin was never really part of the religion at all.

But Dalit thinkers cut through this comforting myth. For Ambedkar, caste was not an aberration — it was the skeleton of Hinduism itself. His conversion to Buddhism

of redemption feels hollow when sin is the foundation. To believe Hinduism can be “saved” is to imagine that the house can stand while its beams are rotting.

Art by Purny Ahmed

There can be comfort in hyperbole. I put a callout asking for accounts of lived experience in these institutions. I received responses from people still in Christian high schools to those who attended in the early 2000s. A friend shares “the fact that the joke even has real roots is almost comforting to me: it makes me feel like I was participating in something canonical”. We can conceptualise this as a kind of solidarity: “I wasn’t just some lonely, gender-fucked nerd with a bad haircut, I was one of many gay people, past and future, doing the same old tricks to get myself through the hell of highschool”. We are not the first to go through repressive school systems, nor will we be the last. Queer and genderdiverse people tend to have this power of finding community in oppressive settings, of ‘homosocialisation’, is in our bones. My concern is society’s equation in determining a queer population and an LGBTQIA+ friendly population; the bonds within queer communities being used to dismiss the very real homophobia and transphobia in spaces like ‘all-girls’ Christian high schools.

Have you ever pondered the origins of rhetoric like “everyone is gay at Christian all-girls’ schools’? Hardly the manifestation of the ‘woke agenda’,

this phrase falls in line with the history of eroticising lesbianism and the sexualisation of girls and young women by heterosexual men. A friend accurately delineates to me that “it paints a picture of some lesbian utopia where all these schoolgirls are kissing each other”. A paper written in 1999, Correlates of Heterosexual Men’s Eroticization of Lesbianism, discusses prevalent male viewership of lesbian pornography and the targeting of lesbian media toward heterosexual males as a reflection of the male perception of lesbians as inherently hypersexual or bisexual. Lesbian identity is constantly scrutinised by men who view women as explicitly sexual beings, surmising the female gender as subservient to male pleasure. When school-aged children are brought into this, it brings paedophilic ideation to the surface.

Aside from this jargon’s entrenchment in the vile, ‘everyone is gay at Christian allgirls’ schools’ is constantly used to excuse the need for support systems for young queer people in these environments, which equates homophobia as a rite of passage. A friend reflects on their experience: “Volatile language was a constant throughout my time in highschool: younger students would

call me a ‘dyke’ in the canteen line”. Another writes “a close friend of mine was almost expelled because she was found with another girl who went to the school who was her girlfriend”. Within the conversations I had with those who had relatively positive experiences in schooling, there seemed to be consensus that “while it wasn’t particularly traumatic, it also wasn’t particularly empowering either”, with responders describing a lack of outreach and, for lack of a better word, pride. Someone writes “without a social group or pre-established trusting relationship with a staff member, nothing within the institution of the school offered support or protection to queer members of the student body”.

The use of reductionist jargon like ‘everyone is gay at Christian all-girls’ provides institutions with the opportunity to ignore the needs of queer students since there is already a theoretical comradery based on a ‘common’ experience. This sentiment’s saturation was, according to another friend, “used to spread rumours (about them), and led people to make assumptions” about them, often villainising identity. Another friend reflected that “it was considered predatory to be actively queer in those environments”.

Things grow more sinister as cishetero society lets themselves in on the joke, trivialising queer experiences in what are often oppressive environments. A study conducted in 2021 outlines that over 90 per cent of LGBTQIA+ students hear homophobic language at school. 1 in 3 of these students are confronted by slurs on a daily basis. These students said that, when within earshot distance of this

Jessica Louise Smith is an ‘all-girl’ school survivor.

homophobia, only six per cent of staff intervened. Queer and gender-diverse students are bearing the brunt of a storm that people are laughing at. So many people are forgetting to acknowledge those who suffer under irony, forced to go against belief systems and assumptions.

Power and solidarity can be harnessed by high schoolers who have these shared circumstances, [I wonder if it’s salient to make a point here that power and solidarity should not have to be formed by the students who are often young teenagers, and there should be institutional onus to do so. Further, those who don’t have this identity keenly homogenise queer experience, forming a narrative of ‘what it’s like to be queer’ or accruing queerness to a matter of circumstance — “I’m not queer because I go to an all girls Catholic school, I’m queer because that’s who I inherently am”.

We can laugh at taboos and enjoy the way these help us connect with each other, but we cannot let humour overshadow the need for change in Christian education systems and the experiences of young queer and gender-diverse individuals must navigate them. Rhetoric around queerness in ‘all-girls’ Christian schools is not only damaging for its reductionist outlook, it also further perpetuates an androcentric view of queerness. When women and gender-diverse individuals can’t be imposed on by their oppressors, they create self-gratifying narratives to satisfy the need to control and dominate us. The worst part is, it’s not even true: not everyone is gay at Christian ‘all-girls’ schools… though a girl can dream.

Since I was young, whenever I felt myself to be in an exquisite moment — something representative or beautiful or iconic — I would get goosebumps down my spine. If the moment was particularly perfect, my whole body would shiver.

At 16, in Darwin, this feeling hit me almost every other day. I had rich material, a youth so classic it was almost American: cars, parties, drugs, love triangles, cigarettes, and profundity leaning against a window in the backyard. But there was strangeness too: the orange sun over the Timor Sea,

A sort of grey fog hangs over me these days. The grey fog is the part in a conversation where you will have run out of things to say to each other.

its rays lighting everything that we did. I never really knew what to call this feeling I would get. At one point I would have called it magic, but now I think it was the sense of something running out. The flashes of feeling like the pulse of a drug, stronger and more urgent as it fades.

And then as the scenes changed and the actors got up to play other parts, it did fade. Until eventually, sometime around my arrival in Sydney, I ceased to get the feeling at all.