VOICES

Edition 3 / The terroir issue explores how a sense of place, literal and conceptual, informs creativity – be it in wine, food, music or art.

IN WINE, WE FIND LIFE

In wine we seek truth, craft and the passion of discovery. In life, we seek to build a community connected by a love for wine and wine culture. We are Maze Row Wine Merchant. We inspire a culture of fine wine discovery, a life that talks of people and their sense of place, of truth, craft and endeavor. An enriching journey, encompassing heritage, terroir, culture and philosophy. Through our curation of wines, stories and immersive experiences, we share the best of life with the adventurers, the bon vivants, the passionate connoisseurs.

Welcome to VOICES, the publication by Maze Row.

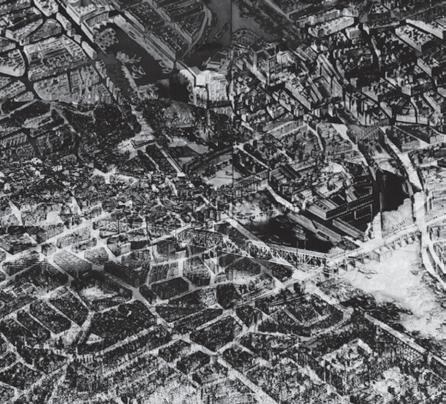

Jane Jacobs believed in the critical importance of communities. In her seminal 1961 study “The Death and Life of Great American Cities,” the American author, theorist and activist argues that modern urban planning which favors high-rises, malls and highways, destroys organic encounters that happen on ground level within intimate neighborhoods. These chance meetings can lead to the exchange of ideas, ultimately expanding our knowledge and understanding of individuals, local communities and the wider world.

You may ask: what on earth has urbanism got to do with wine? But if we apply Jacobs’ theory to, say, a publication like VOICES, then perhaps nurturing a safe space that encourages expansive conversations, forming a tapestry of ideas among seemingly disparate people, will naturally lead to knowledge sharing. Who knows, it may even spark up something unexpected. This is what we are striving for within these pages. And we hope you, our community, will join us to enrich these conversations.

For this edition, we are embracing the theme of “terroir,” interpreted in its broader, more conceptual meaning to be about our sense of place – physical, ideological, spiritual – and how this informs our creative process, be it in wine, gastronomy, music, or the arts, with plenty of diverse expressions that we hope will whet your appetite to explore more.

Jancis Robinson, the undisputed queen critic of wine, discusses taste and wine and grapes with the aesthete Stephen Bayley; we learn how Riesling, Mosel and Paris informed the underground musician Skinny Pablo’s album, and why visual artist Almudena Romero’s delicate ethereal photography speaks of the fragility of this planet.

In Chianti, Barbara Widmer of Brancaia continues her quest to craft wines of distinction that express these luxuriant Tuscan hills; while from his base at The Language of Yes in California, rebel vintner Randall Grahm talks candidly of his uncompromising support for Rossese/Tibouren to create wines of place.

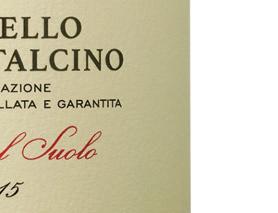

We catch up with Pietro Ratti who speaks of the challenge he faced with the 2019 Barolo to make a wine of distinction from Nebbiolo grown on the highest elevation at the Piedmont winery. Similarly, at Argiano we learn how the work of soil expert Pedro Parra and winemaker Bernardino Sani has transformed the Tuscan winery’s vintages, as illustrated with the 2018 Brunello di Montalcino Vigna del Suolo.

Meanwhile, on the subject of food, a panel of Michelin-starred chefs from California to London speak of the potential of pairing wine with Japanese, and sake with fine French cuisine. We look at why Atlanta’s gastronomy remains a potent expression of its past and present identities, and head to Michael’s Genuine to see how this neighborhood joint manages to also be a top wine destination in Miami.

Elsewhere, the traditional language of wine (a bit of a hot topic) goes under inspection, and we begin our new series on fine wine investment which promises to be a useful tool for all aficionados. Plus, there are plenty of travel pieces to ignite the spirit of adventure in us all, including a sprinkling of la dolce vita from Marie-Louise Sciò, the creative director of the chic Pellicano Hotels, who shares her irresistible secret Italy.

We hope you enjoy the collective conversations we’ve gathered here from those who choose to move between more than one culture. And as you head off to explore this edition, we’d like to invite you to join us, and help us broaden our perspective. VOICES is about the intersection of wine, food, and culture. Our guiding philosophy is: In wine, we find life. Get in touch. Share your view.

VOICES editorial director, Nargess Banks

CONTENTS

STARTERS

WELCOME

In the third edition of VOICES by Maze Row, we continue our mission to view and explore the world of wine through different lenses.

MEET THE COLLECTIVE

We are a group of winemakers, sommeliers, educators, writers, connoisseurs and food and wine lovers with a shared passion for life.

THE WINES

05 50 100 102 110

08 50

12

UNSUNG HERO

Randall Grahm, the rebel Californian vintner, champions the much underrated Rossese/Tibouren while sharing his outlook for The Language of Yes and Popelouchum.

UNDER THE TUSCAN SUN

Swiss transplant Barbara Widmer has put down strong roots at Brancaia in the Chianti hills, where she aims to create wines that are an original expression of the local terroir.

LIQUID ASSETS

Chosen with care like fine art, wine can be a great investment. But what are the best ways to get started? We investigate the perils and potentials of investing in fine wine.

GROUND CONTROL

With soil mapping transforming winemakers’ knowledge of their land, we meet Pedro Parra, whose work with Argiano has led to the highly praised 2018 Brunello di Montalcino.

RAISING THE BAROLO

We quiz Pietro Ratti on his new 2019 Barolo vintage, produced with Nebbiolo grapes grown on the most elevated plot of his renowned Piedmontese vineyard.

DRINKING & DINING

A QUESTION OF TASTE

How does the mystery of taste apply to wine? Stephen Bayley, the aesthete who has made it his life’s mission to unravel the riddle of taste, asks the queen critic of wine, Jancis Robinson.

40 78

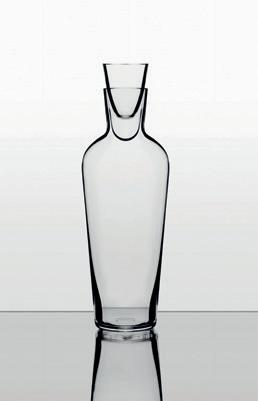

CRYSTAL CLEAR

What makes an ideal wine glass? We ask designer Richard Brendon, who collaborated with Jancis Robinson on a collection of handblown, single crystal glassware.

SOUTHERN CHARM

Atlanta’s gastronomy is an expression of its past and present identities. Two local chefs and a sommelier shine a light on this unique food destination.

74

32 44 82

78 6

EAST MEETS WEST

The versatility, acidity and delicacy of Old World wines can help bring out the best of traditional Japanese ingredients, say a panel of Michelin-starred chefs.

FRENCH CONNECTION

In the heart of London’s Mayfair, Michelin-starred chef Michel Roux of Le Gavroche is exploring the potential of tasting fine French dining with a sip of sake.

AT THE BAR

Having led the way for Miami’s refined fine dining scene, Michael’s Genuine is both a neighborhood joint and a gourmet hotspot, and it is one of the top wine destinations in Florida.

ARTS & IDEAS

DOORS OF PERCEPTION

How wine critics, educators and sommeliers discuss wine is evolving to be more inclusive. But can language invite and engage wider communities and speak to global audiences?

FIELD NOTES

MJ Towler meets underground music producer and Riesling aficionado Skinny Pablo to see how his debut vinyl album Paris Mosel brings wine and terroir into play.

PLANTING SEEDS

Spanish artist Almudena Romero has been questioning production and puts a spotlight on consumption with her ephemeral organic photography.

FIRST IMPRESSIONS

What does your bottle and label say about your winery? We investigate how brands are rethinking packaging in terms of both style and substance.

WANDERLUST

SECRET ITALY

Marie-Louise Sciò, the creative director of Pellicano Hotels and founder of Issimo, opens her little black book and shares with us some of her favorite spots around Italy.

THE STEEPER THE BETTER

Some of Europe’s steepest and most labor-intensive vineyards produce wine as spectacular as the scenery. We speak with the brave vintners on the challenges and rewards.

SIPPING IN THE SUNSHINE

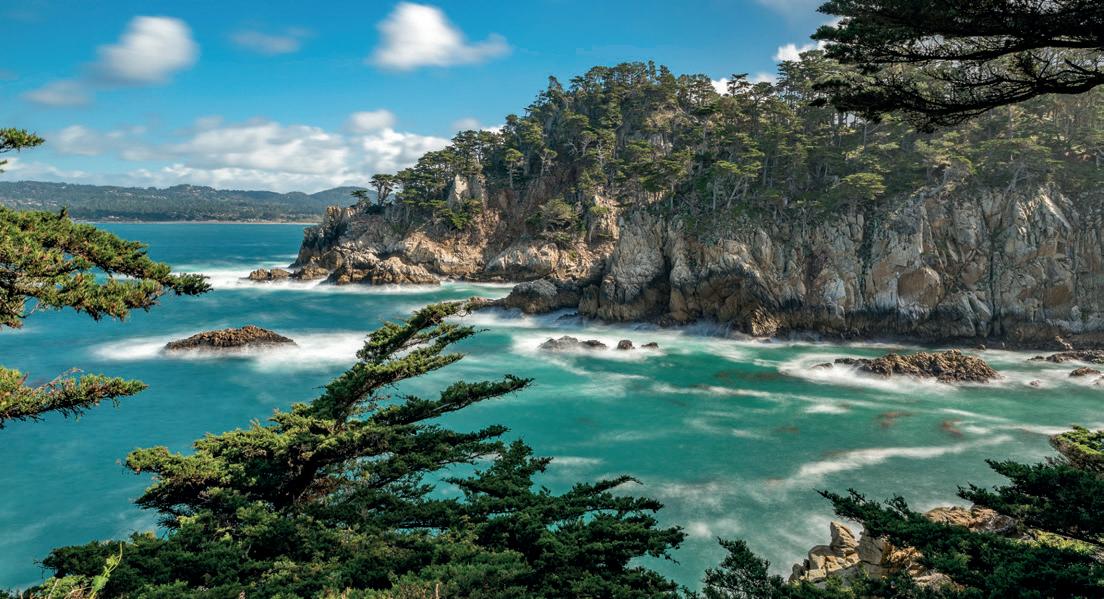

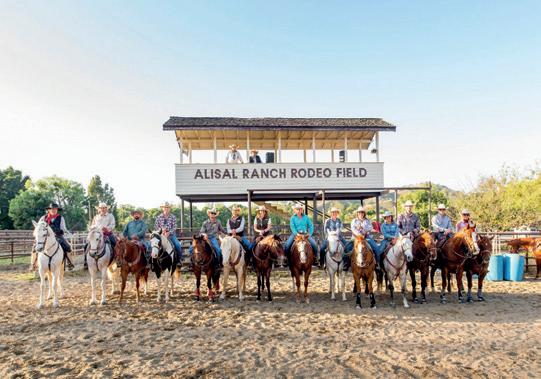

When in California, it’s best to go nowhere fast. Take a leisurely road trip from LA to Santa Cruz, then stop off at Napa for a heavy pour of wine country.

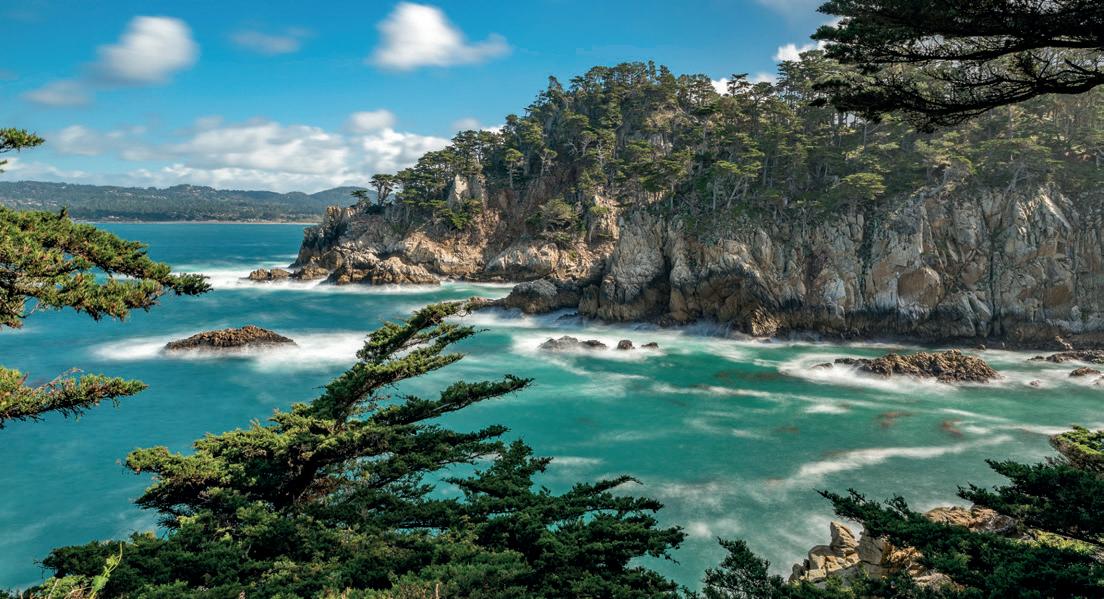

WINE TRAILS OF CALIFORNIA, CENTRAL COAST

Hit the road through the center of the Golden State to taste the many fruits of California’s famous wine country.

120

26 20 86 96 26 120 128 138 140 86 128 7

Jancis Robinson

One of the most respected wine authorities in the world, and the author of several key wine books, talks with Stephen Bayley on p32 about taste and grapes over Maze Row vintages.

Stephen Bayley

The co-founder of London’s Design Museum, and the person for whom the term “design guru” was coined, Stephen discusses the mystery of good taste with Jancis Robinson on p32.

Jordan MacKay

The writer speaks with soil expert Pedro Parra and Argiano’s Bernardino Sani about the science that led to the highly praised 2018 Brunello di Montalcino on p102.

Barbara Widmer

The Brancaia winemaker creates wines that are a unique and elegant expression of the local Chianti terroir, as she tells Nargess Banks on location at the Tuscan winery on p50.

Randall Grahm

The pioneering winemaker explains on p12 how his belief in vin de terroir continues to guide his journey to craft wines of distinction at The Language of Yes and Popelechum.

Pietro Ratti

The owner of Ratti, the celebrated Piedmont winery known for its unique expression of Barolo, talks on p110 about growing Nebbiolo on the higher elevations of Serradenari.

Bernardino Sani

On p102 the Argiano CEO and winemaker tells Jordan MacKay how scientific soil mapping helped him produce the acclaimed Brunello di Montalcino 2018 vintage.

Marie-Louise Sciò

As creative director of the Pellicano Hotels and founder of style platform Issimo, she is the embodiment of sprezzatura with her effortless style. On p120 she reveals her secret Italy.

THE COLLECTIVE

8

We are a community of wine producers, food and wine connoisseurs, passionate writers and photographers, artists, bold thinkers and creatives

Le Gavroche’s Michelin-starred chef has made the unusual choice to pair a traditional French dish with sake. On p78 he takes on a culinary journey from France to Japan via London.

Hailing from a dynasty of worldleading chefs, with her own Notting Hill restaurant, Emily pairs classic French cuisine and sake with her father Michel Roux on p78.

Originally from Guam and based in Long Beach, California, the Riesling enthusiast creates underground music, art and fashion, as he shares with MJ Towler on p26.

The writer and content strategist heads to California’s Central Coast on p138 to explore the region’s unique food and wine culture, noting the best places to eat, drink and visit.

Abbie Moulton

With winemakers looking at alternatives to traditional heavy glass, what does your bottle and label say about your winery, asks the wine writer and co-author of New British Wine on p96.

The founder of The Black Wine Guy Experience podcast meets the cutting-edge musician Skinny Pablo on p26 to discuss his new album, inspired in part by Mosel’s vineyards.

The Spanish artist questions production and consumption, and our human connection to nature with her ephemeral organic photography, as we discover on p86.

A seasoned food and drinks writer and regular columnist at The Bold Italic, Distiller and Gin Magazine, Virginia discovers why Japanese food pairs so well with Old World wines on p74.

Michel Roux

Skinny Pablo (aka John Phillips)

Jillian Anthony

MJ Towler

Virginia Miller

Emily Roux

Almudena Romero

Michel Roux

Skinny Pablo (aka John Phillips)

Jillian Anthony

MJ Towler

Virginia Miller

Emily Roux

Almudena Romero

9

THE COLLECTIVE

An editor at Esquire UK whose visit to Bordeaux’s Château d’Yquem first enticed him into the world of wine, Will takes us on a whirlwind tour of Europe’s steepest vineyards on p128.

Influential sommelier and director of beverage at The Genuine Hospitality, the Miami native joins John Irwin to see why Michael’s Genuine has become a Miami classic on p82.

The Unsukay chef fancies himself a Southern gentleman, full-time whiskey drinker, and general ne’er do well. On p44 he shares his enthusiasm for Atlanta’s culinary scene.

As wine director at Lazy Betty in Atlanta, Marvella likes to pair sought-after wines with highend dishes through the Atlanta restaurant’s tasting menu, as she discusses on p44.

The executive chef and partner at Lazy Betty in Atlanta, Aaron shares his thoughts on why the spirit of community is at the heart of Atlanta’s culinary scene on p44.

The director of training for Empire Distributors, Eric gathers around food and wine specialists from Atlanta on p44 to talk local cuisine and the region’s gastronomic scene.

Passionate about photographing all things drinks related for the last 20 years, he shoots the Maze Row collection of fine wines throughout the publication.

Our lifestyle photographer heads to Tuscany to shoot Brancaia on p50, and to Pall Mall in London on p32 to capture Jancis Robinson in conversation with Stephen Bayley.

Helen Cathcart

Will Hersey

Marvella Castañeda

Chris Hall

Aaron Phillips

Eric Crane

Robert Lawson

Amanda Fraga

Helen Cathcart

Will Hersey

Marvella Castañeda

Chris Hall

Aaron Phillips

Eric Crane

Robert Lawson

Amanda Fraga

10

JOIN THE VOICES COLLECTIVE

Roberto

The photographer was seduced into a life in wine growing up in Piedmont. On p110 he heads to Ratti to capture the winery’s highest elevation Serradenari vineyard.

Nargess Banks

The VOICES editorial director heads to the Chianti hills on p50 to meet Brancaia’s Barbara Widmer who, through respecting land and nature, is making exquisite wines.

Adam Thomas Spinach Branding’s partner and co-director leads an international team who believe in timeless yet timely design, as he demonstrates as the creative director on VOICES.

Leigh Banks

The partner and co-director at Spinach Branding loves nothing more than helping businesses reveal their most unique and engaging brand stories, as he demonstrates with VOICES.

The Spinach Branding assistant has a passion for investigating art history’s influence on modern culture. On p40 she asks designer Richard Brendon what makes an ideal wine glass.

The Maze Row wine specialist taps into the art of wine talk on p20, then on p82 sits at the bar at one of Florida’s top food and wine destinations, Michael’s Genuine.

The Maze Row director is a student of life and a disciple of the art of hospitality. Food and wine help her understand the world, as she looks into investing in fine bottles on p100.

A year studying for an international MBA in Veneto catapulted her into the world of wine and wine culture. As part of the Maze Row team, she helped bring VOICES to life.

John Irwin

Fortunato

Emma Mrkonic

Theodora Thomas

John Irwin

Fortunato

Emma Mrkonic

Theodora Thomas

us widen our lens. Contact us: editorial@mazerowwines.com

Help

Suzanne Denevan-Brown

11

UNSUNG HERO

Randall Grahm, one of California’s more innovative vintners, shares his thoughts on the much underrated Rossese/Tibouren variety, and his pioneering outlook for The Language of Yes and Popelouchum

Iam a contrarian to the core and when the crowd is moving in one direction, I am generally headed in the opposite one; I’m in with the “out crowd, ugly duckling.” Grapes are my métier, my schtick. More than 20 years ago I put this temperamental disposition into practice by introducing a line of wines which I imported under the aegis/ marque of Il Circo – Italian wines made from obscure, oddball grapes that were generally undervalued and under-appreciated. As part of my research, I was lucky enough to spend some time with Luigi Veronelli, editor of Gambero Rosso, and asked him about the truly unheralded, genius Italian wine grapes. Signor Veronelli was kind enough to share with me his thoughts on what was presumably his favorite subject; if memory serves, perhaps highest on his list was a rather obscure, very old variety called Rossese di Dolceacqua, grown on terraced vineyards not far from Genoa in Liguria. Veronelli was incredibly generous to offer his assistant, Daniel Thomases, to act as my escort and interpreter, arranging visits to some top producers. I spent the day with Daniel, visiting maybe five domaines; I confess that at the time I was unable to truly grok the genius of the variety at all. The wines (all red) were for the most part fairly light in color, seemingly light in body, high in acid and slightly herbaceous; the grape’s charms were subtle at best.

Rossese is indeed a lot more like Pinot Noir than like, say, a dense Sagrantino; I had been thinking fast ball and was served up perhaps a knuckler. Chalk it up to a still relatively immature palate, or possibly to one that worried o’er much about how a subtle wine would play in Peoria to those who needed the reassuring qualitative imprimatur of density and imminent power. Still, I suspected there was something interesting going on, but it was something that I would have to revisit down the road. I can’t really discuss the details of how it happened but somehow I found myself gifted with a few sticks of Rossese budwood; I put them in my vine collection and pretty much forgot about them for quite a while.

CHANGE OF HEART

In the intervening years, my palate seems to have matured slightly and I began to gain an appreciation for wines that were not so dense and certainly not over-extracted, wines that were “agile,” capable of movement or evolution in the glass. About ten years ago I found myself at Marea restaurant in New York City, and something possessed me to order a bottle of Rossese di Dolceacqua. It was from Maccario Dringenberg, although I’ve failed to remember the specific vineyard. But, the wine was just a revelation as far as its elegance and complexity. The stars had realigned. This was a

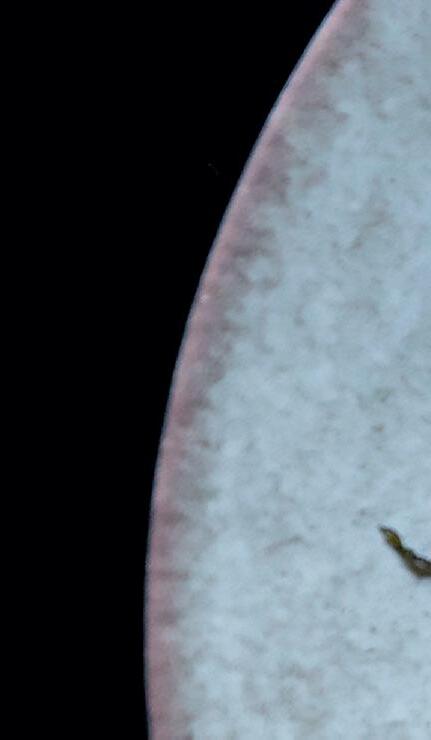

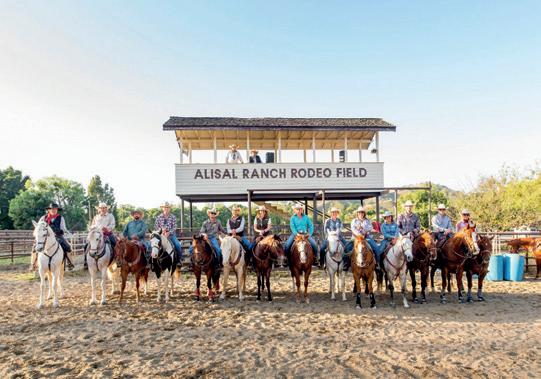

POPELOUCHUM VINEYARDS

quasi-Burgundian wine conveniently not composed of that pesky Pinot Noir.

I became obsessed with my rediscovery and began tracking down as many Rossese bottles as I could find – not so easy to find as it turned out. There was a brilliant article by Andrew Jefford which appeared in Decanter in 2015, titled “Rossese, A Wine Made by Empty Spaces,” in which he argues that Rossese may well be a grape that satisfies the insatiable Burgundian itch, in part due to its flavor geometry, if you will. The “empty space” is not the physical geography that separates the steep hillside plantations one from the other, but rather the spaciousness of the wine itself on the palate, and its ability to move through that gustatory space the way a musical note persists through the silence of the unplayed notes. I imagine Rossese as perhaps the Miles Davis of grapes.

SAME DIFFERENCE

At about the same time, I had developed a small, controllable dependency on Clos Cibonne rosé (and red, to some extent), as any Bay Area would-be wine hipster does. This was a different grape from a different part of the world, Tibouren from Provence. I especially loved their old vine offering, Cuvée Spéciale des Vignettes. Somewhere in this time frame I had the occasion to spend some time with Andrew Jefford and he delivered to me a bombshell that rocked my

SANTA MARIA VINEYARDS

14

TLOY WINERY

CENTRAL COAST

world: Rossese di Dolceacqua and Tibouren were in fact genetically identical. It was a bit like finding out that you had two friends who knew each other independently of yourself and happily enough, got along famously. Phew!

Here are some of the differences I perceive between Tibouren and Rossese, at least understood from where they are traditionally grown: Tibouren is found in somewhat warmer and dryer sites than Rossese and there may well be some clonal differences between them. Tibouren, as a red wine, is to my palate somewhat more “rustic” than Rossese, typically richer in body and in alcohol, with slightly lower acidity. It is said that Tibouren is a superb vehicle for the transmission of ambient flora, known locally as garrigue. My sample size (of one) is not scientifically significant but one feature I did happen to observe of the Tibouren at Clos Cibonne was the pretty radical disparity of ripeness between bunches and even within the bunches themselves. Rossese grown in Paso Robles, San Juan Bautista or Liguria, does not seem to share this same tragic flaw to nearly the same extent.

While most certainly the aromatic terpenes of ambient vegetation both in Provence and Liguria play a role in the unique character of Tibouren/Rossese, it’s also quite possible that the presence of pyrazines from less than totally ripe fruit might also play a role. I’ve noticed that

the slight herbaceousness of red Clos Cibonne, especially in greener years, seems to morph into a wonderful mintiness with the passage of time. It’s just an impression but I imagine that Rossese has slightly more spaciousness, as described by Jefford, in its palate as compared to Tibouren. As in a musical rendering, fewer notes are played but they echo and play with one another, conveying depth and resonance.

GIFT OF GRAFT

My experience of Tibouren/Rossese in California has been enormously encouraging and I feel that I’ve experienced still but a glimpse of its immense potential. I was able (amazingly) to persuade a grower friend of mine to initially graft an acre of Tibouren in the El Pomar District of Paso Robles. Rather warm and very dry during the day, cool at night, with beautiful calcareous soils – not so dissimilar to, ahem, other places where Tibouren is grown. We grafted Tibouren/Rossese on some frankly pretty distressed 30-year-old Sangiovese vines, ones that had all sorts of “issues,” leading to somewhat borderline productivity, compromised root system, somewhat uneven ripening (likely non-genetic in origin), etc – in short, a bit of a mess.

And yet despite the numerous challenges of this particular site, the grapes it yielded produced the most stunning pink wine I had ever experienced in California. The color of

the fruit – nothing to write home about. Many bunches failed to properly color up at all. But there was a quality to the wine that I can only describe as possessing a kind of life-force, a dramatic savoriness and persistence of flavor as it evolved in the glass. The fragrance, while discreet, was haunting – almond and cherry blossoms in particular. Oh, to be able to sip this wine in Kyoto in springtime.

WARMER CLIMES

Under The Language of Yes brand [a collaboration between Randall and Joe C. Gallo, the founder of Maze Row], I’ve now made three commercial vintages and the Tibouren, blended with a lesser volume of Cinsault and occasionally Mourvèdre, has consistently amazed and delighted me. We’ve allowed the wines to go through malolactic fermentation, so that they may be bottled without the need for filtration, preserving their remarkable texture and impressive finish. The scant production comes from two acres of ruinously shy-yielding Tibouren planted at Paso Robles, and those vines are likely not too much longer for this world.

But, entretemps, after numerous and exhaustive Rossese/Tibouren dinners with corporate management, what I mean is, after additional comprehensive, in-depth research, I have been able to persuade my colleagues at The Language of Yes of the unique beauty and potential

©Helen Cathcart 15

of the variety in California, especially in younger, healthier and slightly cooler vineyard sites. We were able to locate such a vineyard, not far from King City and grafted approximately two acres this last spring with an additional 2.5 acres to graft this coming spring. The vines are proving to be remarkably vigorous and healthy. I expect them to produce on the order of 25 tons of fruit when they are fully bearing, which will be just a few short years away.

Why do I imagine that this relatively small planting of Tibouren will be interesting for the wine industry in general? We have in recent years been experiencing the dramatic effects of global climate change everywhere and California has certainly not been spared. Moderate and cool sites on the Central Coast, once suitable for producing elegant varieties like Pinot Noir, are often moderate and cool no more. Put another way, what do you do if you are determined to produce wines of elegance and balance from varieties that were once capable of delivering the goods, but perhaps are no more?

Conversely, Tibouren is a variety, as is perhaps Cinsault, that I believe is capable of producing a particularly haunting and elegant wine in a relatively warm climate. It appears, as does Cinsault, to be relatively drought tolerant as well. Maybe equally germane is the fact that the wine world is getting smaller and consumers everywhere have the new opportunity to try

wines made from exotic grapes they’ve never seen before. Yes, there has been a great consolidation of large and mid-size producers and wine distributors and wine shelves and lists are crowded with familiar faces, but I suspect that has created a counter-demand for the less common styles, for the heterodox. At the end of the day, there is always a place for wines of unique personality and distinction.

TESTING GROUND

I’m growing Tibouren at my own Popelouchum vineyard in San Juan Bautista as well, just a modest plantation of a little over an acre but at the same time I’m doing something utterly unique with the variety. I’ve harvested several thousand seeds from self-crossed Tibouren to see if I might not come up with an interesting variant that may well be better to our growing conditions than its parent. At the same time, I’m toying with the hypothesis that genetic variants of a given variety, even if they are in some sense “inferior” to their parent, may enable one to potentially create additional nuance and complexity in a field blend.

The “best” clone of a given variety might well be a composite of many biotypes or variants of that variety. The notion of a heterogeneous planting, which flies in the face of conventional viticulture with its emphasis on uniformity, may afford a unique opportunity for the observation

and selection of unique individuals with particularly useful traits – drought or heat tolerance, superior (or complementary) taste profile. But, most significantly, it allows one the opportunity to observe and learn and ultimately select for the future, as not all viticultural knowledge is vouchsafed upon cursory inspection.

It is my hope that Popelouchum can serve as a laboratory for The Language of Yes, exploring not just new varieties (or heterogeneous combinations thereof), but the implementation of new and progressive grape growing and wine-making methodologies – from the use of biochar and inoculated cover-crops (as a means of enhancing the biotic potential of soils) to experimentation with the air-drying of grapes to lignify stems, thus allowing for superior structure in the wine and improved fermentation kinetics.

At Popelouchum, we are in the process of creating/discovering entirely new and unique varieties through the somewhat tedious but time-tested conventional grape breeding process, grapes bred not to solve a particular winemaking or viticultural problem, but rather in the hopes of discovering something strange, new and beautiful. It is my hope that at least one of these varieties might find a home in The Language of Yes. (How could anyone say “no?”)

“I imagine Rossese as perhaps the Miles Davis of grapes. It has the ability to move through the gustatory space the way a musical note persists through the silence of the unplayed notes”

16

Randall Grahm

17

A SELECTION OF THE LANGUAGE OF YES RELEASES

THE LANGUAGE OF YES SYRAH 2021

Co-fermented with 14 percent Viognier, The Language of Yes Syrah is aromatic and high-toned, reminiscent of St. Joseph, but with a piney blue-fruited boost given by its California provenance. Remarkable for its drinkable restraint.

THE LANGUAGE OF YES PINK WINE

“LE CERISIER” 2021

A blend of Tibouren, Cinsaut, and Mourvèdre with a little bit of skin contact, this pale-pink wine is rich with aromas of stone fruit and flowers with a textured, creamy palate and a salty finish. Decant before serving.

18

The 2021 vintage released a red, the Syrah, and a rosé, the Pink Wine ©Rob Lawson

19

DOORS OF PERCEPTION

Is the essence of a wine more important than the way it is described – in Shakespeare’s words, “would a rose by any other name smell as sweet?” Or could it be that the words we use to describe our favorite bottles influence our enjoyment of them? Is it possible that we think, therefore we taste? John Irwin delves into the art of wine talk and explores how our individual cultural backgrounds influence how we see the world – and taste it.

PROUST’S MENCÍA

In November of 2022 Punch contributor John McCarroll wrote an article titled “The Wine Flaw of Our Times” about a retronasal aroma on the finish of some wines commonly referred to as “mousiness.” The “…of Our Times” part of the title refers to the fact that it’s a descriptor almost exclusively associated with natural wines, thought to be caused by some combination of long fermentations, warmer global (and therefore cellar) temperatures, and less-than-reductive winemaking (basically, “Spring Break, Daytona” for bacteria). “Mousiness,” when present in a finished wine, inspires such exotic aroma descriptors as “hamster cage,” “corn chips,” or – depending on whom you ask – “authenticity.”

I have drunk many mousy wines, dozens, maybe even hundreds, over the years. Except… I never knew it. I had heard the term here and there and understood the general idea but never thought, “oh, this wine is mousy.” But when I read McCarroll’s article, I learned that the smell is correlated to Brettanomyces (a type of yeast also known as Brett, which I am sensitive to), and that little factoid lodged itself into an accessible part of my brain.

So, a day or two later, I ordered a bottle of Mencía from a natural-leaning producer that I love, gave it a sniff, noted the unusually high concentration of Brett, and then tasted the wine. And, there it was, in a flash of awareness: an unconscious resurfacing of memories of my first pet, a hamster named Snickers. The wine was mousy, clear as a bell tone. But, not only that. I also had the Proustian recognition that I had tasted this before. Many, many times. Another door of my perception had opened. My life was forever changed.

With a misplaced obligation of politeness to the world around me – as if I’d uncovered a conspiracy that threatened all human order –I continued to sip the wine. I did not enjoy it. My wife, who was with me, having not yet bit into the fruit from the Tree of Knowledge, blissfully polished off a couple of glasses. “Good wine,” she said and smiled.

MORNING BOYS, HOW’S THE WATER?

WHAT THE HELL IS WATER?

COMING OF AGE

Do you remember the moment – you were probably a teenager, looking at the stars or a lava lamp – when you initially recognized that our experiences are limited to our individual perception? It probably went something like this: “Ok, but what if, like, the blue that I see is different than, like, the blue that you see? Like, what if your blue is my red?”

It’s rote and universal but profound, so allow me to resurrect this stoner philosophy to new ends: what if, like, the wine I’m tasting is different than, like, the wine you’re tasting? Like, what if your “pear” is my “pineapple”? And, yet further into the unknown: what if I’ve never had a pear? Is my perception of the wine the same or different? How much of our perception is influenced by upbringing, culture, exposure, and language? And within that question, what is right in front of us that we cannot see?

SOMETHING BLUE

“Blue didn’t always exist.” This, as with all provocative or insane statements, begs for context. In his 2010 book, Through the Language Glass, linguist Guy Deutscher recounted an intriguing discovery made in the mid-19th century by a British politician named William Gladstone. Gladstone moonlighted as a classics obsessive; ten years before becoming the Prime Minister of the UK, he published a 1,700-page opus entitled Studies on Homer and the Homeric Age. It was received with the kind of rapture you would expect, which is to say that most people – if they paid any attention at all – were more amazed by his obsession than the work itself.

But, only an obsessive could have discovered a fascinating little detail about one of the most famous books in the history of Western literature. In Homer’s Odyssey, throughout 24 volumes and 134,560 words, the author does not utter a single word that could be taken to mean “blue.” In fact, what Gladstone discovered is that Homer’s world was remarkably colorless. Words that mean “red,” “yellow,” “green,” and “violet” made brief cameos, but they were used almost at random, more to get at the idea of saturation than color. He called honey “green” and iron “violet.” And as for the Mediterranean Sea itself? The aqueous object upon which the mighty Odysseus sails for verse after verse? That is not blue but “wine-dark.”

It would be a strange but meaningless historical footnote if this were an outlier. Perhaps

Homer made an artistic choice, or maybe he was colorblind and lacked a good editor (the legend that Homer was fully blind is a myth). But it’s not an outlier. Another researcher named Lazarus Geiger pulled on Gladstone’s tantalizing thread some years later and discovered more peculiarities. It turns out the Old Testament never mentions the color “blue.” Ditto the Koran and the ancient Icelandic sagas. And the Hindu Vedic hymns, where they describe all the colors of heaven? Blue was left off the guest list. A millennium of ancient texts and nary a mention of that which colors the sea and the sky.

SHADES OF MEANING

The Russians have two words for what we know as blue: “siniy” (to us, a dark blue) and “goluboy” (a light blue). Both of these colors would appear, to any westerner, as two shades of the same color. But to a Russian, these colors are as distinct as green and yellow would be to us.

This is to say that color is a cultural construct. Where I, as an American, will distinguish between blue and green, other cultures – like Russia – might establish more nuance, adding additional vocabulary for what they’re perceiving. The opposite is also true: in most scenarios, the Japanese lump what we would call, separately, “green” and “blue” into a single word: “aoi.” (As an aside: “midori,” the term used in Japanese to refer to the concept of “green” as a color, was not widely adopted until after World War II. So, when traffic lights were imported from the US, they were described by the local newspapers as having lights of “red,” “yellow,” and “blue,” which is how they are still described today).

If you point out “yellow” school buses and “white” clouds to any child, you are not perpetuating an objective visual sense but a subjective way of dividing up the world based on how those things were once presented – and then reinforced – to you.

Back to Gladstone, Gieger, and Homer: if color is cultural, maybe our ancient forebears didn’t have a word for blue. It didn’t occur to them because it wasn’t necessary; ocean and sky aside, blue is not a color you see very often in nature. Much like the Japanese are building a new relationship between blue and green, our ancestors likely demarcated their color world over generations. From that lens, it becomes easy to understand why Homer’s sea was “winedark.” He was describing it in relative terms.

What’s interesting is how these cultural differences may affect how we think. For example, a 2008 study conducted by a joint team from Stanford, MIT, and UCLA showed that Russians could identify different shades of blue faster than their western counterparts. A similar study conducted in 2005 offered the flip side of the equation; the Himba tribe of Namibia, who have no word for blue, were demonstrably slower than English speakers to identify a color difference between blue and green. Yet, the Himba have several terms for “green.” When they were shown different shades of the color, they were predictably faster than the control group at identifying them.

Language, then, strongly relates to how we perceive the world. To quote Deutscher: “Is it possible that linguistic differences can be the cause of differences in perception?” Or, to put it another way, if Homer didn’t have a word for blue, could he even see it?

COLOR TO TASTE

If you were to crawl into a time machine and zap yourself back, you would likely discover that Homer could see a color difference between the ocean and, say, a boat. It’s not that he couldn’t perceive differences; without categorization through language, context probably would have been a crucial ingredient to recognition.

In wine, we experience this all of the time. Blind taste a wine-agnostic friend, and they will have no idea what the wine is or any meaningful descriptions. But, if you blind taste them two wines, then they can expound on the differences through their cultural totems (“this is more like lemonade,” “this has more fruitiness,” etc.). It’s a common belief that, with time and experience, we evolve our language to describe what we’re sensing. However, it’s more often that the opposite is true; language comes first, opening the door to perception.

In his 2022 research paper for the Institute of Masters of Wine, Justin Martindale (MW), conducted a case study on the “Evolving Language of Minerality in Wine Tasting.” He evaluated more than 20,000 Decanter magazine tasting notes from 1976 to 2019 and found that the term “minerality” was not common until the early 2000s, hitting its peak in 2010 when it appeared in more than 15 percent of all tasting notes. How could something so familiar be nearly unheard of just a couple of decades ago?

24

“How much of our perception is influenced by upbringing, culture, exposure, and language? And within that question, what is right in front of us that we cannot see?”

Did wines before the new century not exhibit minerality? More likely, as in Homer’s colorless world, we’re not processing the presence if we don’t have the language. It’s a “tree falls in the forest” problem; if a wine has minerality, but no one’s there to name it, is it ever really there?

HOW’S THE WATER?

I’m not arguing that language invents experiences (though I’m not closing the door on that, either), but it can sharpen them into focus. To quote the writer Joshua Rothman, “to describe our thinking is to domesticate it.” My experience with a mousy Mencía mirrored my experience with other aromas like petrol, reduction, petrichor, and corked wines. In all cases, language pre-dated my perception.

What’s profound about this isn’t just how it affects individuals but how they add to a dramatic whole; how entire cultures, civilizations and eras can perceive the world differently due to little more than a cosmic clerical error. It’s as if, through our life and history, we’re unlocking new doors to perception through language and slowly filing in.

All this brings to mind a well-known parable from author David Foster Wallace: “Two young fish are swimming along, and they come upon an older fish swimming in the other direction. The older fish nods and says, ‘morning boys, how’s the water?’ The two young fish continue swimming along for a bit before one turns to the other and says, ‘what the hell is water?’”

It can be frustrating to feel at arm’s length of a thing, that liminal space just outside of perception. When you learn about wine, you can scrape the edges for weeks, months, or years, living on the edge of recognition. But from another lens, this is the greatest gift of our lives; in wine and colors – as well as in art, science, and nature – there is always something new, something to be discovered, and the challenging, glittering truth that there is more we cannot yet see. This life is endless because we cannot know what we do not yet know.

If only we had the words.

25

John Irwin is a Maze Row specialist and Italian wine ambassador with Vinitaly International.

FIELD NOTES

MJ Towler meets underground music producer and Riesling aficionado Skinny Pablo to see how his debut vinyl album Paris Mosel brings wine and terroir into play

Making wine and music involves a combination of art and science. In both cases, the process requires a great deal of skill and knowledge, often involving specialized tools and equipment to achieve the desired result. There is something else though. Something that is both tangible and intangible. In wine, we call it terroir. In music, it’s the recording studio.

The Foo Fighters first explored this connection with their highly acclaimed 2014 album and eight-part mini-series Sonic Highways. For the project, the band recorded in eight iconic US studios around the country, visiting town after town and taking in the “terroir,” then writing and recording a song, before moving on to the next city.

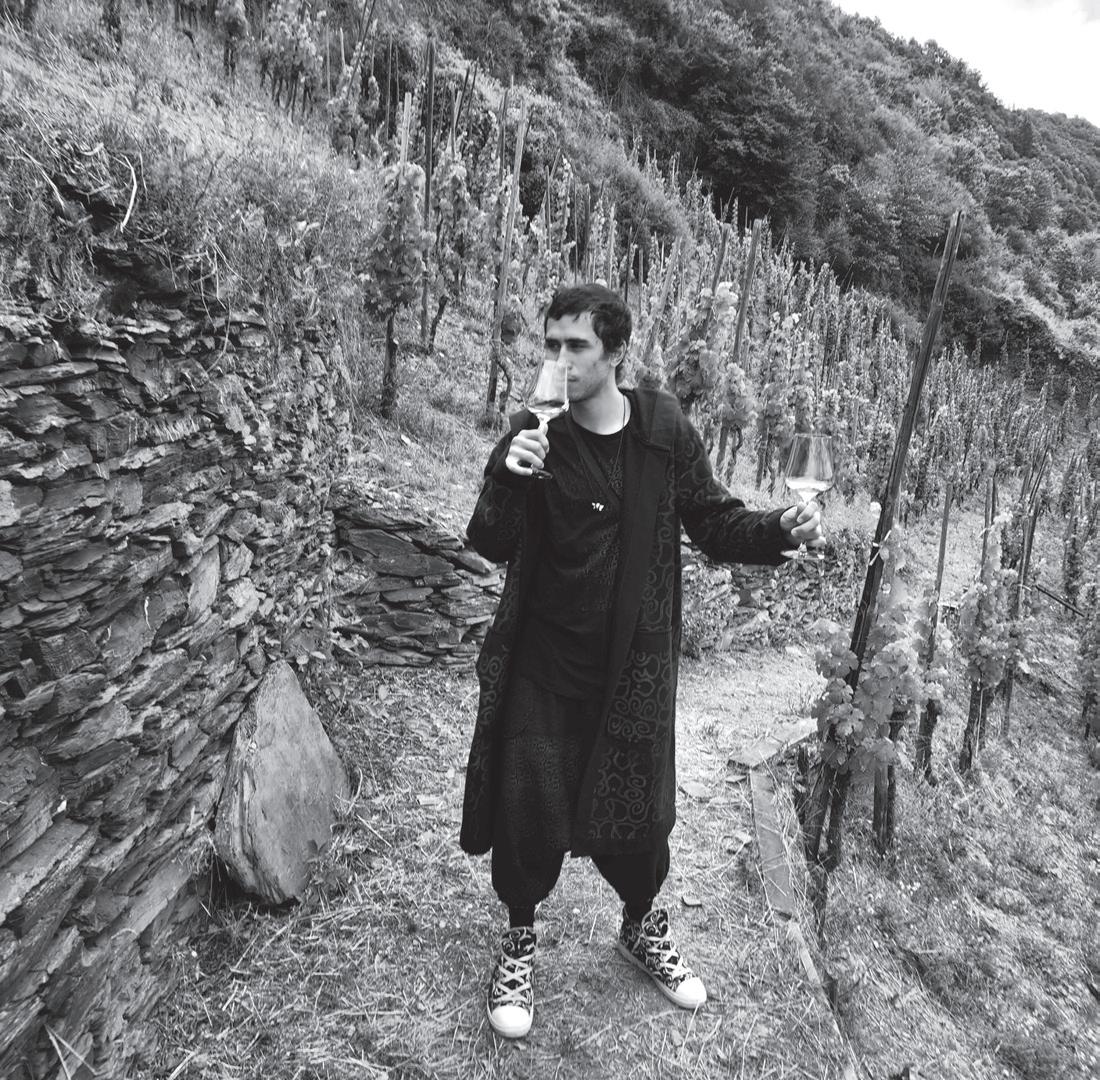

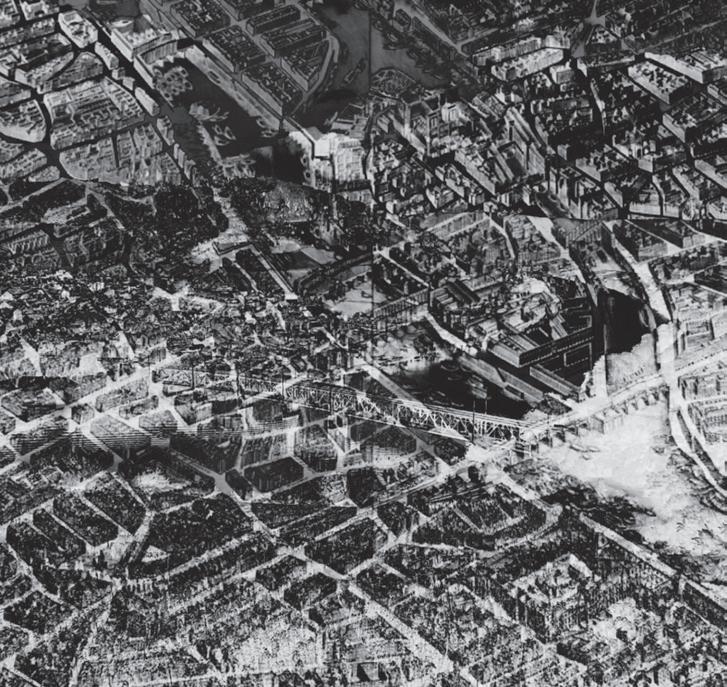

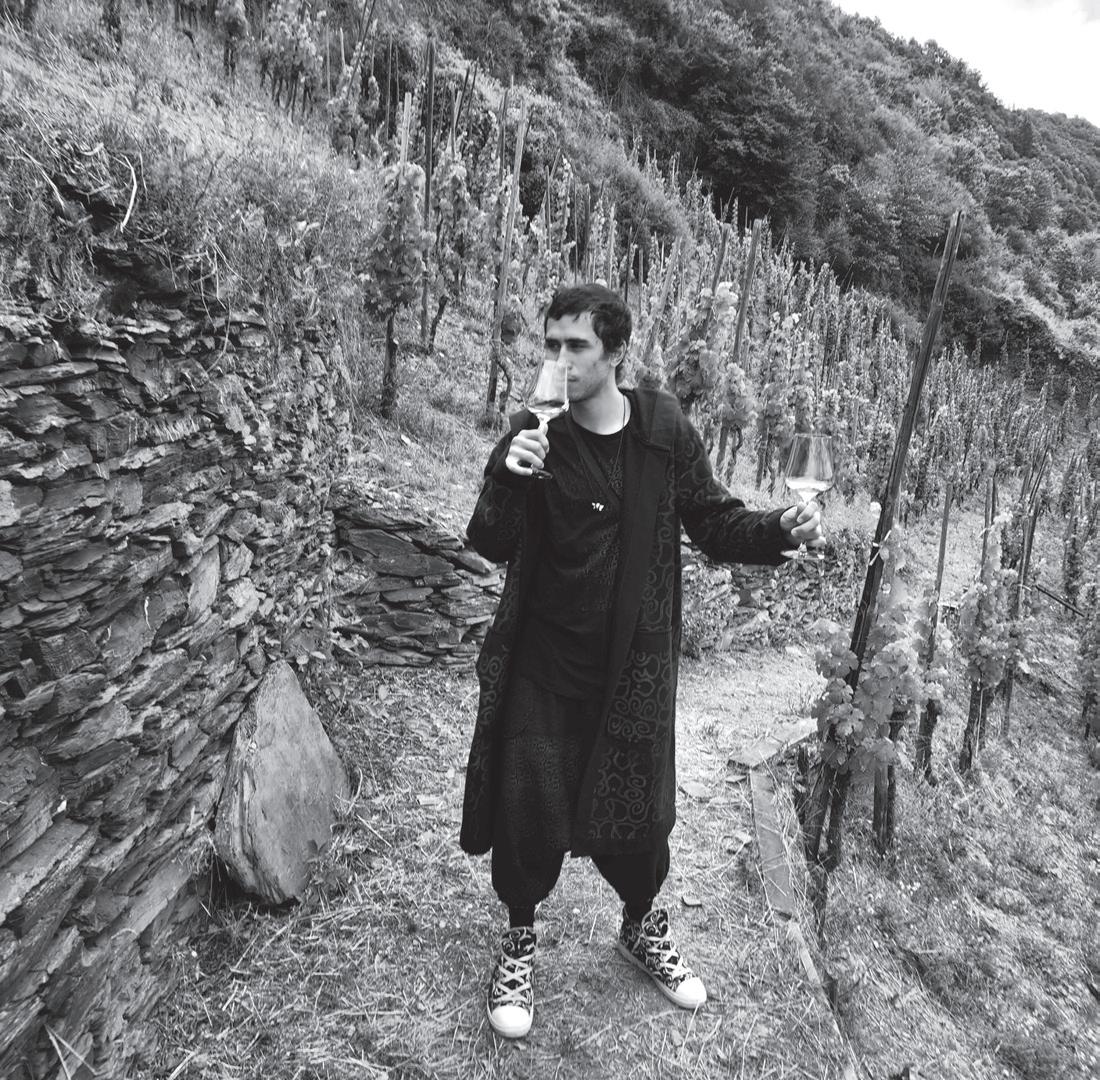

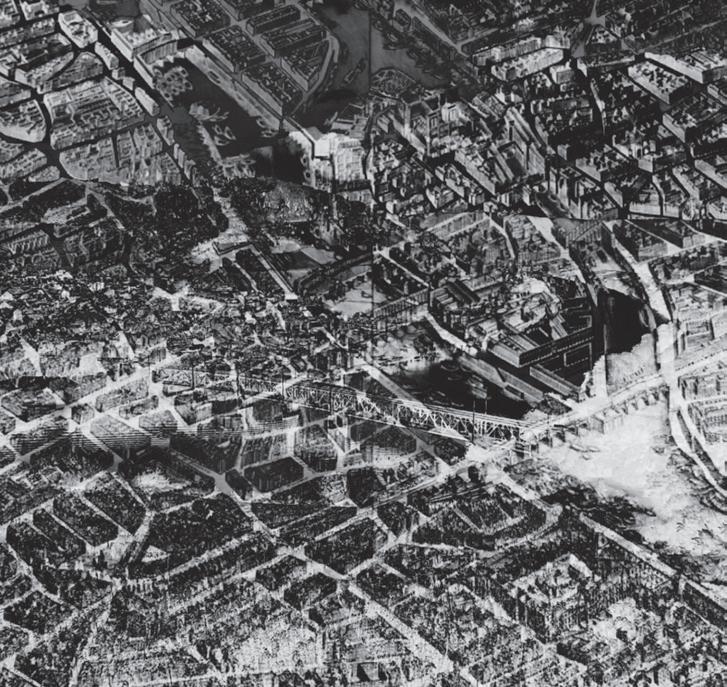

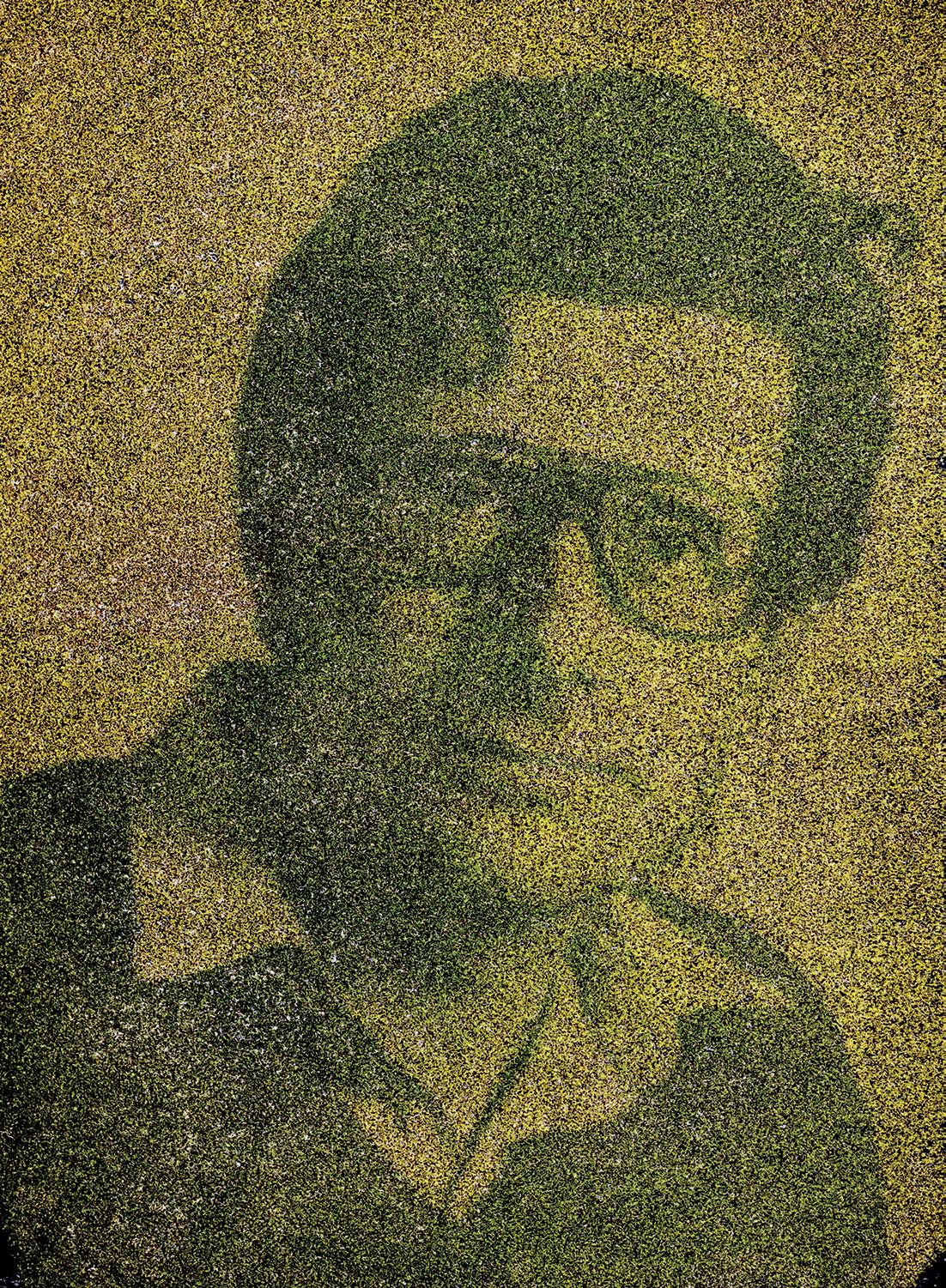

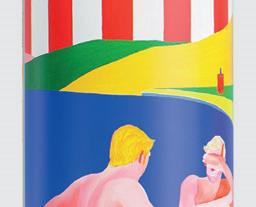

Skinny Pablo is breaking similar ground with his debut vinyl album Paris Mosel. This is music inspired by terroir, in this case the urban fabric of Paris and the Mosel’s ancient vineyards. I am meeting Skinny on the heels of the album’s release to understand his creative process.

Hailing from Guam and based in Long Beach, California, John Phillips, aka Skinny Pablo, is an underground music producer, Riesling aficionado and self-described disruptive child of the avant-garde. Skinny tells me the first half of the album was recorded electronically utilizing samples. It’s his musical interpretation of Paris –inspired by the cuisine, fueled by croissants, and an ode to the streets of this artists’ mecca with his musical journey finding its way through La Bastille, Montmartre and Pigalle as well as hip

eateries Les Enfants du Marché and El Nopal.

The second half of the album was made in Mosel – the mystical and rugged winemaking land in Germany with century-old vineyards. This is the home of Ulli Stein, the revered winemaker celebrated for making Rieslings of distinct character. Stein lives in Alfer Hölle, initially constructed as a hotel in the late 1800s, where in the dining hall sits a grand piano overlooking the Mosel river. Here, Skinny composed and recorded the piano portions of Paris Mosel during the harvest of 2022. And it became a musical diary of his time at Alfer Hölle, Sankt Aldegund and Bullay.

Process is critical to the creation of Paris Mosel. Skinny talks of the acquisition of a device called the T560 Vinyl Recorder. “It’s made in Germany, and you can’t just buy a machine,” he tells me clearly enamored by the musical equipment. “You have to fly there and be trained by its creator.” The T560’s inventor is audio engineer Ulrich Sourisseau, whom Skinny describes as a “mad scientist” living in this small town near the Swiss border.

Skinny had been awestruck by the recorder when he had encountered it six years ago since it had been his lifelong dream to make a record. He says his first thoughts were: “I can make my records!? I mean, digital’s cool. Tapes are pretty dope, but, you know, the dream is to have a vinyl record, just like everybody else back in the day.” After 18 hours of continuous training in a tiny shed, Skinny learnt to operate his T560. It’s what he’s using to press the vinyls for Paris Mosel

FROM MOSEL TO PARIS

The Paris Mosel project has its genesis in gratitude and collaboration. Skinny narrates the story. He had been invited to the Mosel by the wine and vinyl collector Robert Dentice (aka Soilpimp) and Stephen Bitterolf, owner of Vom Boden Imports. It was Dentice’s way of thanking Skinny for all he has contributed to the Riesling Study community. Conceived in 2020, the project began as a way to articulate the nuance and diversity of Riesling. Now it includes other German wines having grown organically into a community of creatives with site-specific events bringing together food, wine and music.

Following two weeks of touring the vineyards of the Mosel and meeting the producers, the group celebrated at Ulli Stein’s Alfer Hölle. Skinny says he was blown away by the place and was psyched to play some beats. Dentice asked Skinny how he would like to return during harvest and write a record? “We’ll talk to Ulli about it, you can stay here,” he said. “While they’re harvesting grapes, you’re writing music. How do you feel about that?” Skinny’s reply was a resounding yes.

While waiting for the harvest season to start, Skinny decided to take a break and make his way by train to Paris. “I’m spontaneously in Paris, and it’s such an inspiring city for art,” he recalls. “So I said: okay I’ll do Paris Mosel It’s going to be a musical diary of this kid from Guam flying into the Mosel drinking a bunch of wine, then going to Paris, eating, drinking. and instead of writing words, I am going to make music.”

28

In Paris, Skinny set up a crowdfunding campaign and made beats all day, every day. He had brought along a small sampler called the Octatrack, and the entire album was made using his phone and the sampler. He didn’t even have a laptop with him. He rented a studio and recorded drum tracks – something he had never done before. It was here that he began developing the record in his mind, working tirelessly until his return to the Mosel.

Once back in Germany, his frenetic pace continued. Skinny made beats morning, noon and night, composing them on the piano at Stein’s house. He drew inspiration from the treacherously steep terraced vineyards, ancient mineral-rich limestone soils, and 70 to 120-yearold gnarled vines that made him think about the texture of his music.

A lover of dub music, Skinny saw parallels in the terroir of the Mosel. The rugged terrain reminded him of the low-fidelity, dirty and dusty sounds of old-school Jamaican dub in the style produced by the legendary Lee Scratch Perry. In 2020 Skinny had fulfilled another lifelong dream when he had collaborated with Perry on his single “Rain Inna Babylon.” Says Skinny: “You take what you have to work with and then add your own texture and style – the same way a winemaker works with the terroir and creates their unique spin on things.”

Other than his sampler, for Paris Mosel Skinny used a drum set and a piano. He took the two recordings using two entirely acoustic instruments, both percussive, with no amplification. He combined them in the way a winemaker

would using different lots from specific vineyard parcels. Skinny describes the beats from Paris as a bit more refined and processed, whereas the piano and the Mosel were a little edgier. He combined the two to create new recordings.

Stein had compared Skinny’s music-making process to Naturwein, or natural wine, made with minimal intervention by the winemaker. Skinny concurs, saying his recording style’s minimal use of electronics mirrored this idea of minimal intervention.

Finally, to pay homage to his time in the Mosel, Skinny included a transcription of “Mosel Weinlied” with the LP. According to local folklore, the song was awarded a Fuder (1,000 liters) of the finest Riesling for winning the 1864 Traben-Trabach Casino songwriting contest.

Skinny describes Paris Mosel as stuff that many people have never really heard with influences from his favorite musical genres: dub, hip hop and electronic psychedelic styles. And because of the terroir, he’s created a special “blend” for the album.

Through his music he hopes to shed light on great Rieslings and a good life of pairing music with it. Ultimately he wants to inspire, to get his listeners in the mood to drink a great bottle of wine, enjoy delicious food with good friends, and have a great time.

When grapes are planted somewhere new, they will give a different interpretation of a wine. An artist, in this case, a music producer from Guam, can also create differently in a new setting. When the environment becomes the muse, something completely different emerges.

My conversation with Skinny Pablo makes me think of the rapper Rakim’s lyrics, “It ain’t where you’re from; it’s where you’re at”.

The Paris Mosel vinyl was released on December 24, 2022. Each cover design of the first run of the physical LP is one-of-a-kind, hand-drawn in pen and ink by Skinny Pablo.

MJ Towler is the founder of The Black Wine Guy Experience podcast.

SIGN UP TO VOICES the publication for Maze Row:

Stay informed with industry news, reviews and interviews. Receive regular updates on new vintage releases. Gain member-only invitations to special events and tastings.

Left, Skinny Pablo enjoying a glass of wine in Paris. Right, his Paris Mosel album cover features a combination of images of Paris and the Mosel. Each cover is individually hand-drawn in pen and ink by the artist ©Skinny Pablo

Left, Skinny Pablo enjoying a glass of wine in Paris. Right, his Paris Mosel album cover features a combination of images of Paris and the Mosel. Each cover is individually hand-drawn in pen and ink by the artist ©Skinny Pablo

29

30

31

“You take what you have to work with and then add your own texture and style – the same way a winemaker works with the terroir and creates their unique spin on things”

A QUESTION OF TASTE

How does the mystery of taste apply to wine? Stephen Bayley, an outspoken commentator on modern culture, art and design who has made it his life’s mission to unravel the riddle of taste, heads to 67 Pall Mall London to ask the queen critic of wine, Jancis Robinson

Iwas staring out of the window, thinking about Proust and neuro-aesthetics when Jancis Robinson walked in.

Jancis is one of the most respected wine authorities in the world. Self-taught, too. If it does not sound inelegant to say so, her nose is unrivaled. Her palate as well.

And her technical mastery of wine is, by consensus, unmatched.

Marcel Proust, with no column in The Financial Times newspaper, has fewer readers, but nonetheless wrote the best ever account of taste and memory. What he called “l’édifice du souvenir,” that moment when a madeleine dipped in tisane began an avalanche of recollections inspired by what it did in his mouth.

Meanwhile, neuro-aesthetics is that emergent discipline whose fundamental proposition is that our brains are hard-wired to appreciate some things more than others. Our preferences, neuro-aestheticians argue, are not based on intellect, culture, desire and acquired learning, but inalterably built into the structure of our brains. Beauty is not in the eye of the beholder, it’s in the amygdala. It seemed a good moment to ask the author of The Oxford Companion to Wine some questions about taste.

We settled into our positions on the banquette. When I said that any disinterested study

of the history of visual arts showed that taste changes from one period to the next, often hilariously, Jancis agreed the same applies to wine. There are no absolutes. “Wine evolves in the same way as fashion.”

This is a tricky proposition since no-one really understands how fashion evolves, only that it changes. “In the 1990s we liked big, oaky, dark, alcoholic fruit bombs. Now we prefer lighter and cleaner and less alcoholic wines,” Jancis explained. “There is no right and wrong about wine.” And there’s no right or wrong about skin-tight jeans versus flares. Maybe the neuro-aestheticians are wrong.

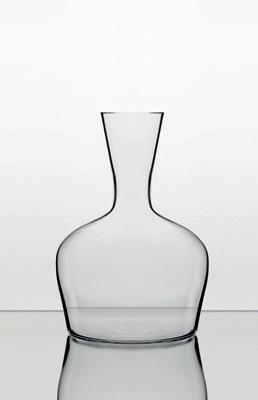

A sommelier came to arrange glasses in front of us, different shapes for the various different wines we were about to taste (or, in my case, drink). Jancis did a small eye roll. “You actually only need one type of glass,” she said.

This is a personal conviction, but also, she said, a reflection of a zeitgeist – her word – that prefers simplicity to elaboration. Such is her commitment to simplification, she has had contemporary product designer Richard Brendon design a standard glass for her (p40).

Swirling a luscious Pieropan Soave around an inferior glass, I asked if the “legs” were an indicator. I’d always believed that the Marangoni effect, those viscous dribbles, was something

to look out for. And it seems I was wrong: “You can disregard legs,” said Jancis. “Length is the indicator of quality.”

“Length,” in wine terms, being the lingering taste: Proust’s “souvenir,” a memory that lasts. I asked now about the notorious terroir, and how wine reveals stories about places, taking you on an aesthetic adventure without leaving your banquette or bar stool. My slight reluctance to enjoy Welsh wine, I said, even as a proud Welshman, is because I prefer being prompted about the Rhône than Ebbw Vale, but she did not concur while failing actually to endorse the emerging viticulture of Wales, saying instead: “I am certainly excited about English wine.” Recently, she has become interested in Swiss wines, too.

Now, even as we were drinking Italian wines, I wanted to quiz her about the absurdity of Bordeaux, whose business proposition could not exist in any other area but the feudal complexities of the wine trade. I mean: “I will sell you an expensive wine right now which you might be able to drink with pleasure in 30 years. But, then again, perhaps not.”

She agreed. “I have been railing against en primeur for decades. Bordeaux is pulling the wool over our eyes. They don’t need the money (up-front). Just compare it to Rioja. The top

“Wine very rarely tastes of grapes, except Muscat!”

Jancis Robinson

34

Stephen Bayley and Jancis Robinson at 67 Pall Mall, London, with a selection of Maze Row wines

makers only release their wines when they are actually ready to drink.”

And, I wanted to know, the en primeur scam apart, what about that obfuscatory stuff tasters say about Bordeaux. Doesn’t “complex” just mean difficult? Jancis replied: “No. Complex means nuanced.”

There is no special discipline for training tongue and nose, just a lot of practice. I mentioned the great Victor Hazan’s simple and perfect tasting rules. Sniff the primary aromas of the wine sitting still in its glass. Give it a swirl and sniff the secondaries. Look at it, and do you see brightness or dullness? Taste it. Do you find it long or short? And do not forget to note whether it is red or white, or, nowadays, orange. That’s all you need to know. She did not demur.

But I wanted to understand why tasters always use an abecedarium of associations: apricot, cherry, blackcurrant, tobacco, pipi de chat, lychees, biscuit, cedar, farmyard, pear drops, petrol, vanilla. Unforgettably, she told me: “Wine very rarely tastes of grapes, except Muscat!”

I stared into what was now my new glass of Ratti Barolo and remembered a visit to HautBrion where one taster sniffed and said, “I think I am getting a little Brazilian woman,” which has become my all-time favorite taste association.

Then there was Robert Louis Stevenson who described a wine “as red as a November sunset and as odorous as a violet in April.” Or John Armit saying a good red Burgundy should smell of manure, although he used a shorter word. Jancis was too discreet to follow this mucky lead.

As a coup against oenological obfuscation, I brought the critic Walter Benjamin into the conversation. Benjamin believed if you can copy a work of art perfectly, which nowadays you can, why bother with an original? Is it just the snobbery of direct association with a maker, say Leonardo? If you like the taste of, say, Château Palmer 1970, then someone in a lab can imitate it for you with a so-called “Frankenwein,” named for the composite monster, just as delicious and much less expensive. Jancis was not so sure. “No-one,” she said firmly, “has done ‘Frankenweins’ properly.”

But maybe one day they will. Montaigne believed if you take pleasure in drinking good wine, you are bound to be disappointed when you have to drink bad. “To be a good drinker, you must not have too tender a palate,” the philosopher in his Gascony tower said. This inevitably led to the question about catering methodology: does she start a dinner with wine of a certain level and then work up to a climactic

resolution with the very best? “It depends how boozy your friends are,” she replied.

Translated, if you have friends who enjoy wine, start them off on a little of the good stuff and let them get greedy later with volumes of vin ordinaire. So now I know that if I visit Jancis and my first glass is a 1945 Latour, I have been categorized as a boozy hog.

The mysteries of taste reveal themselves slowly. They are arbitrary, but pedantic. They involve prediction and surprise, delight and disappointment. Knowledge has its uses, but so too does innocence.

Tasting, I think, is not a pseudo-science. It is not a science at all. Like all the best things in life, it’s irrational. Like love. I winked at my Barolo and carried on.

©Helen Cathcart

Jancis Robinson and Stephen Bayley tasted Pieropan Calvarino Classico 2020 and Ratti Conca Barolo 2018. For more on the wineries, visit mazerow.com.

35

Pieropan ranks among Italy’s greatest producers of white wines, bottling definitive expressions of Soave Classico.

WELCOME TO THE CLUB

At 67 Pall Mall in London members can discover more than 1,000 wines by the glass and up to 6,000 by the bottle

The wine members club isn’t a new concept. Wine lovers have long enjoyed the privilege of exploring vintages in a private setting and with kindred spirits. What’s thankfully changed are the exclusive nature of such clubs reserved primarily for men. New establishments make it their mission to attract and welcome diverse communities. And this is exactly where 67 Pall Mall sits.

Disappointed at being unable to enjoy fine wine at sensible prices, in 2015 Grant Ashton, a former London banker, decided to open a wine club for wine aficionados and industry professionals alike but with a more relaxed feel. Unlike most wine programs, 67 Pall Mall works on the basis of a small cash mark-up so as to entice members to discover new wines, be explorative and share their interest.

Central to the club’s offering is the diverse iPad wine list, which is unique to each location be it in England, Switzerland, Singapore or France. In London, members can discover more than 1,000 wines by-the-glass and up to 6,000 by-the-bottle, with expert service from a team of 16 sommeliers. Showcasing the lesser known to the most iconic, the lists have been curated to excite, challenge and captivate and is peppered with reviews, tasting notes and producer profiles.

Ashton followed the London club in 2021 with an outpost in the Swiss Alps, 67 Pall Mall Verbier, where members have access to wine as well as a Ski Concierge service. Meanwhile the Singapore Club, which premiered the following year, has the largest sommelier team in South East Asia on hand to help navigate some 5,000 wines, and there is a Whisky Wall boasting 430 bottles. Soon, 67 Pall Mall Beaune will open as the club’s first French location, situated in the heart of the gastronomic quarter in the wine capital of Burgundy.

©67 Pall Mall

39

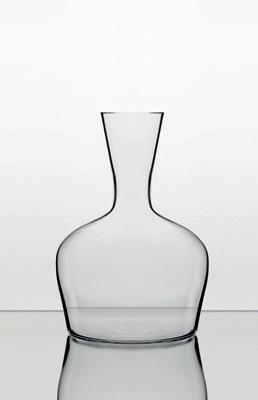

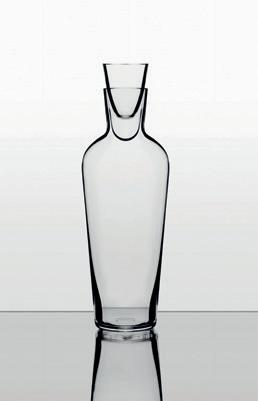

CRYSTAL CLEAR

Wine expert Jancis

Robinson and designer Richard Brendon have collaborated on a hand-blown, single crystal, dishwashersafe glassware collection designed to enhance any type of wine. Theodora

It is no secret that the glass can hold the key to enhancing the full sensory experience of wine. Collaborating with the renowned wine expert Jancis Robinson, Richard Brendon has sought to do just this through a refined collection of handcrafted glassware. The British designer is quick to bust some of the myths surrounding conventional wine glass shape and size, championing universality in a market of seemingly never-ending choice.

What are the advantages of the Slovenian crystal used to make the glasses in the collection?

My priority in all of our products is to make them the best they possibly can be. This means sourcing the best materials in the world, and so far we have found the best to be in Slovenia. However, should we find that other regions are able to compete with this quality then we would consider them too. As long as we’re working with expert craftspeople and an exceptional quality of glassware, we know we’ll be creating an incredible product.

How was the glass design developed to capture the nose and mouthfeel of red and white wine?

When I first approached Jancis Robinson in regards to creating a collaborative collection, she made it clear from the outset that it should be absolutely feasible to create one glass that can serve all wines to their best ability – as long as it was the perfect glass! It immediately became our priority and goal to achieve something completely universal, and we are truly delighted with the result.

The tulip-shaped bowl allows the wine to breathe, whilst capturing the aroma to enhance

the experience of every sip. And the curvature of the bowl maximizes the wine’s surface area when the glass is filled to a 125ml pour. The gossamer thin glass, meanwhile, allows the drinkers to be in as much direct contact as possible with the wine itself to ensure a rounded, fully immersive experience.

What are the myths surrounding glassware –particularly pertaining to the idea that red wine requires a larger glass than white?

When Jancis and I first started talking about the perfect design for our glasses, one of her particular irritants was the trend of white wine glasses being routinely smaller than those designed for red, despite the fact that white wines can be equally complex and deserving of aroma enhancement. This was one of the reasons we combined the tulip-shaped bowl with a narrower opening, to ensure that any wine being served would have the opportunity to fully display its aroma and any particular notes that may otherwise be harder to detect, regardless of its color.

Which glass shape is most suitable for Champagne and sparkling wine, to hold the bubbles best and maximize the taste experience?

Our Jancis Robinson Wine Glass, of course. It is a totally universal glass, from Champagne to Port and everything in between. The combination of the deeply rounded bowl and narrower opening once again presents a number of advantages when it comes to sparkling wines, as their aromas can be beautifully presented, especially in comparison to when served in a typical flute, and the narrower opening ensures the bubbles aren’t lost.

Thomas finds out what makes an ideal wine glass

40

Designer Richard Brendon and Jancis Robinson with (this page and next) the glassware collection

41

©Richard Brendon Studio

SOUTHERN CHARM

Atlanta’s

identities.

destination

In the ever-changing American culinary landscape, certain places remain true food destinations. Some of these cities and regions are known for their unique style of cuisine, while others are famous for a particular dish. Then there are those that benefit from a rich food history found in the diversity of the people.

The latter is what makes Atlanta one of the great food destinations in the country. Many would have had a layover in Atlanta at least once, and sure, the airport – the world’s busiest – has great places to enjoy world-class pizza and cocktails, and even elevated dining in some terminals. But it is when you head out to discover the city that the true magic happens.

There is so much to discover in Atlanta’s food culture. The city is fortunate to have so many cultural influences on the dining scene. The Centennial Olympic Games of 1996 pumped a lot of life into the local restaurant landscape and it has only grown since. While classic Southern staples are easily found, the diversity of the population brings influences from Asia, Latin America, and all over the globe.

From award-winning chefs such as Hugh Acheson of Empire State South and Steven Satterfield of Miller Union, who are redefining Southern flavors, to Christopher Grossman who reimagines the American bistro at The Chastain, there are plenty of restaurants for the traditional diner. Elsewhere, local institution Lucian Books and Wine show how restaurants can be so much more than just a place to eat with its thoughtfully curated book selection, while a trip through Buford Highway sheds light on flavors from around the globe, from Korean

to Thai to Indian. Even the diner is given fresh life, with Kevin Clark’s Homegrown serving up one of the best breakfasts in the country. The city is able to offer something to everyone, from the mind-blowing Lemon-Pepper wings at Magic City to the tasting menu at Gerry Klaskala’s Aria.

To get a fuller picture of what food and dining mean to Atlanta, we rounded up chefs Chris Hall of the Unsukay restaurant group and Aaron Phillips of Lazy Betty, along with the restaurant’s sommelier Marvella Castañeda, who shine a spotlight on this unique region and, along the way, share their personal culinary journeys.

gastronomy is an expression of its past and present

Eric Crane asks two local chefs and a sommelier to share their personal stories and shine a light on this unique food

44

What’s your favorite part of the Atlanta culinary scene?

CHRIS HALL: The camaraderie. Atlanta’s chefs really believe that a “rising tide lifts all boats” and there is a level of camaraderie, care and learning from one another that is inspiring. It’s collaborative and vibrant. The culinary scene here is growing and evolving with more great neighborhood restaurants now than ever before. There are more pop ups, more regionally focused ethnic dining places as well as destination restaurants.

MARVELLA CASTAÑEDA: It’s passionately alive, creatively vibrant, and pushing boundaries everyday. Atlanta is full of passion-driven professionals, whether in food or wine. No one does anything half-way, you can always experience 100 percent intention.

AARON PHILLIPS: The people. There is so much talent in Atlanta. The people working in restaurants make this an amazing place. Diversity is embraced and we are at the forefront of inclusivity and pushing the needle to embracing all cultures. Hopefully more cities can embrace Atlanta’s philosophy.

What cuisine (and wines) do you specialize in?

CHRIS HALL: One of my mentors told me something I have adopted as my culinary mantra: “You can’t argue with delicious.” I enjoy cooking many types of food and loathe boundaries so the philosophy of “cook delicious food” resonated with me. That said, I

believe firmly in cooking seasonally and using the best ingredients you can find.

AARON PHILLIPS: I would say global eclectic, I don’t have any real parameters on me as far as what style of cuisine. My technique is clearly French-inspired with modern philosophies and old-school approaches. As far as flavors go; it could be Peruvian, Caribbean, Japanese or from anywhere. I’ll pull inspiration and flavors from all over the world.

MARVELLA CASTAÑEDA: Lazy Betty is a tasting menu restaurant, and since the food is culturally diverse and constantly changing, the wine program features selections from all over the world with the intention of exposing guests to new styles and regions.

Who have been mentors and what have you learnt from them?

CHRIS HALL: My two most formative mentors are (chefs) Gerry Klaskala and Gary Mennie who taught me about food and its many elements. As a young cook, they helped me with different techniques of cooking that became the metaphorical tools in my toolbox. They also taught leadership, how to run a kitchen, the financial aspects of the restaurant business and, most importantly, hospitality – the backbone of everything we do.

AARON PHILLIPS: As a young chef in New York, the list is vast: Ronald Hsu, Adam Plitt, Adrienne Cheatham and Éric Ripert have all been influential. A specific dish? Chef David

Bouley taught me how to make a seared foie gras when I was 21 and that’s been on my mind ever since.

MARVELLA CASTAÑEDA: The education of wine is an entire language, and I’m fascinated with the history, the laws, the climate and geographical influences. I get to work with such intelligent and helpful sommeliers, wine specialists, representatives, distributors, even influencers. It’s a community that I’m grateful for.

How has your cooking evolved through the years?

CHRIS HALL: There are very few chefs that are doing something “new” with food, and I’m certainly not one of them. Instead I tend to take familiar dishes and flavor combinations and tweak them, and cook with a sense of humor. Food should be evocative: if it brings back memories, then that is incredibly powerful. At Unsukay we’re constantly evolving our food. As I’ve grown as a cook, I have tended towards simplicity. As a young chef, there’s the tendency to try to prove something, demonstrate your skills. Now I try to let the ingredients speak for themselves. Less is more.

AARON PHILLIPS: All dishes are a natural progression and evolution. I want my food to inspire creativity in other chefs. How can we make a dish be the best version of itself? That’s the evolution of food: having the freedom to be creative, and pushing dishes to be better than they have ever been.

45

This page, pizza at Unsukay. Opposite, clockwise from far left, chefs Chris Hall of the Unsukay restaurant group and Aaron Phillips of Lazy Betty, along with the restaurant’s sommelier Marvella Castañeda

47

This page, roasted dry-aged duck at Lazy Betty. Opposite, Hungry Man platter at Local Three, one of Unsukay group’s four restaurants

48

©Layla Ritchey, Erica Botfield and Michael Mussman for Unsukay ©Andrew Thomas Lee for Lazy Betty

What style of cuisine has a surprising wine pairing affinity that is not traditional?

MARVELLA CASTAÑEDA: Fried food, 100 percent. Pairings such as fried chicken and Champagne, or Lambrusco, Riesling, Furmint, Grenache, Assyrtiko and Chablis. There are endless fun possibilities.

Who are your typical customers and guests?

CHRIS HALL: We run neighborhood restaurants, and we are fortunate to cultivate relationships with so many of our guests. I am beyond fortunate to have formed so many friendships with people who dine in our restaurants: guests are now friends. That has enriched my life immeasurably.

AARON PHILLIPS: We welcome anyone who wants to have their life changed by food and the experience. Our mantra is about respect and inclusivity. We want them to be treated in a way they have never experienced, taste things they have never had before, and most importantly to transport them from the stress of everyday life.

How does the restaurant experience enhance the taste of food?

CHRIS HALL: My goal is to transport people away from the daily grind and provide them with an experience, so we focus on the experiential as opposed to the transactional. So, the atmosphere matters, the decor, and the music play a role. The biggest differentiator for us is our staff who care deeply. Their excitement for a dish or a new cocktail or bottle of wine is transferred to our guests.

AARON PHILLIPS: The restaurant experience is a symphony, a play, an orchestra. There is a

holistic team energy that has to be achieved from the host to the dishwasher, and to work together in unison. It can’t be fake, it has to be real. If we achieve that within our ranks then the staff can transport guests to something more than food on a plate. I am inspired by our team; they’re the ones doing the work, creating the restaurant experience.

Do you use a curated wine program to help elevate the flavors?

MARVELLA CASTAÑEDA: Over 50 percent of our Lazy Betty guests will opt for the wine pairings. They are designed to be a part of the food; to not just pair easily, but intentionally enhance the meal evolving into an immersive experience with educational wine descriptions.

CHRIS HALL: I curate the wine programs at all our restaurants so yes, wine is an integral component to our dining experience from pizza to foie gras. Wine can elevate food and vice versa. It’s something we work on constantly.

AARON PHILLIPS: It is absolutely crucial. And just as important is the front of house staff knowing how important that experience is. It is more than just pouring something in a glass. There are stories to be shared which is another element that adds to the experience.

How does the restaurant experience enhance wine service?

MARVELLA CASTAÑEDA: The price has to match the quality. Perhaps they try a wine or a pairing that they will never forget. This means that we work with high-end quality wines and rare gems in the regular menu. Servers are well equipped with information necessary to explain the wines. We let the guests know that

the wine pairings are a full service experience; we pour and we talk about the wine and answer questions if any, and then the food is served. The food is also described in detail.

What is your best or most interesting food and wine pairing experience?

MARVELLA CASTAÑEDA: My top three moments are: Kopke 1979 Colheita Port with tamarind-banana tart with caramel and coconut sorbet; Tissot ‘Traminer’ Savagnin 2018 with a yuzu-poached halibut in bonito beurre blanc; and Au Bon Climat ‘Hildegard’ 2020 with white alba truffle and parmesan risotto.

CHRIS HALL: I’ve been fortunate to have some incredible meals with brilliant chefs and sommeliers. I tend to like to pair the rare with the common: homemade onion dip & chips with caviar. Cheeseburgers and First Growth Bordeaux, pizza and old Barolo.

AARON PHILLIPS: I had a memorable dinner at Per Se and asked for the “full glass” serving for their food and wine pairing menu and it was unbelievable. It was excessive and over the top and I still remember it to this day since it was the perfect culmination of my love of food and wine, and expertly delivered hospitality.

Opposite, top, a bird’s eye view of Local Three’s fare. Bottom, scenes from Lazy Betty including a dish of caviar 46

Atlanta is packed with great places to eat, great chefs and a really interesting culinary scene”

Chef Chris Hall of Unsukay

“

49

Swiss transplant Barbara Widmer has put down strong roots at Brancaia in the Chianti hills, where she aims to create wines that are an original expression of the local terroir. Nargess Banks visits the estate

UNDER THE TUSCAN SUN

52

Barbara Widmer wasn’t born into a wine dynasty. Quite the contrary. The Swiss native was heading towards a career in architecture when, one harvest, her destiny took a turn as she swapped Zurich city life for the Tuscan hills. Now, 34 years on, as CEO and winemaker at Brancaia, she leads a team who craft a measured portfolio of wines that are structured and elegant, and are an original expression of her estate.

For Widmer, winemaking is a philosophy – one that is in constant appraisal. She mentions this quite a few times during our conversations, and the Brancaia website is clear about this ethos: “Every vintage, every floor, every idea that is realized is a new beginning, a new attempt to raise the quality level even further.” Brancaia’s quest to improve each vintage is methodical. It involves exploring clones from indigenous and international vines, and experimenting with different cultivation and fermentation methods. This means working with both traditional and modern vinification practices, aging the wine in wooden barrels of various sizes, as well as cement and steel tanks. In short, for Brancaia winemaking is a never-ending process of discovery.

And you sense this intellectual approach, as well as a respect for detail, at every touchpoint at Brancaia. To start with, the architecture of the winery and visitor center sits perfectly in harmony with the Tuscan landscape. The menu served at Osteria Brancaia is inspired by local gastronomy and made largely with vegetables grown on the estate. The staff are friendly and informed, while the label design is clear, considered and timeless. And, as a small gesture that says so much, the website has the entire team, including the grape pickers and cleaning staff, listed by name and the number of dedicated years at Brancaia. Then there is Barbara Widmer herself: sincere, worldly and very real.

We are meeting at the main winery and visitor center in Radda, perched on the Chianti hills between Florence and Siena. “The most challenging part of being a winemaker is to be committed to what you want to do, but at the same time have an open mind,” she begins as we settle in what was once her family home – a pleasantly restored farmhouse at the foothill of the winery, overlooking a pond filled with waterlilies and a pool nestled in natural stone. Earlier we were treated to a tasting menu at the Osteria Brancaia, on the terrace with vistas of the vineyards and the lush woodlands of cypress beyond. This really is a picture-postcard spot.

Barbara Widmer, CEO and winemaker at Brancaia, in the winery’s cellars

53

TUSCANY FLORENCE SIENA

BRANCAIA WINERY & RADDA VINEYARDS CASTELLINA VINEYARDS MAREMMA VINEYARDS

A TALE OF TWO CULTURES

When the estate was purchased in 1981 by Barbara’s parents, Bruno and Brigitte Widmer, the house and land were in complete ruins. Many local Tuscans had abandoned the area after World War II, relocating to nearby towns or big cities in search of work and the new Italian dream. The Widmers’ first act was to restore the land and plant new vines, and the family would often spend summers vacationing here. Later, Barbara Widmer raised her own children at the house, in 2014 moving to another restored property at a walking distance. Now the Radda house is enjoyed by visiting family and friends.