A Caribbean Heritage

traditional

in the Caribbean

Welcome

SPAB Director, Matthew Slocombe, reflects on recent changes to policy affecting heritage

News and views

The latest from the SPAB and the sector

Member repair project

Phillips on the challenges of his home repair project in Stirlingshire and why the SPAB

was the right choice

Events

Booking online now

Book reviews

latest reads reviewed

Technical notes

and advice

Building in Focus

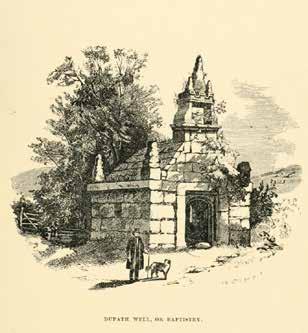

Dupath Well: a chapel of rugged beauty

Visit the members’ area of the SPAB website to view our online property

Remember, you have to be a member to access the list.

Ata recent meeting of the government’s Heritage Council, the SPAB was able to say “well done, we think you’ve got it right,” the Levelling-Up and Regeneration Bill published in May. Although much within the Bill is of little direct relevance to the SPAB, its five heritage clauses are very much our concern. Clause 185 intends a new requirement that local authorities in England must have an Historic Environment Record (HER). HERs bring together information about buildings, landscape and archaeology for owners, professionals and local planning authorities.

Three further clauses (93-5) aimed to tighten loopholes related to enforcement, urgent works and listing and as such were entirely welcome to the Society.

The final heritage clause (92) attempted better alignment between the National Planning Policy Framework and primary legislation: this is sensible in principle, but risked unintended consequences in giving ‘enhancement’ of listed buildings the same status as ‘preservation’ within the law. ‘Enhancement’ sounds good but can be used to justify harmful work of a kind the SPAB would oppose. We have asked that ‘enhance’ should have a clearer definition if it is to have increased statutory force.

The Heritage Council meeting also included an item about tourism trends affecting historic sites. Visit Britain reported that tourism from the US now seems to have returned to pre-pandemic levels, but visitors from China and Northern Europe are staying away. This has significant implications for organisations like English Heritage, Historic Royal Palaces, Landmark Trust and the National Trust.

The National Trust is poised to make a major investment at Clandon Park – the early 18th century house in Surrey severely damaged by fire in 2015. The SPAB is pleased to have been involved in discussions and supports current intentions. When our Fellows and Scholars visited a year after the fire, they felt that the house, laid bare, deserved to be a museum of historic construction techniques. This is, in part, what is now likely to happen.

A further major theme of the Heritage Council meeting was carbon reduction and sustainability – a topic to which the SPAB has a strategic commitment. Much of what is being said by government is positive and worthy of support, but work is still needed to achieve a greater consistency of carbon reduction policy between government departments and their agencies.

At its newly-acquired watermill in Worcestershire (see page 7), the SPAB will be able to promote sustainable energy generation through use of a waterdriven turbine. However, for the owners of many watermills who might wish to emulate this example, matters have become more complicated. Despite government’s aim to reduce carbon emissions and support sustainable power generation, the Environment Agency has just substantially increased fees for turbine installation. The cost is likely to be prohibitive in many cases and could the sustainable re-use of watermills.

Matthew Slocombe, DirectorSPAB STAFF

Matthew Slocombe Director

Douglas Kent Technical and research director

Elaine Byrne Education & training manager

Christina Emerson Head of casework

Kate Streeter Development and marketing manager

Margaret Daly Office manager

Shahina Begum IT manager

Jonathan Garlick Special Operations

(projects & working parties)

Felicity Martin Communications officer

Saira Holmes Development officer

Lucy Jacob Membership officer

Pip Soodeen Fellowship officer

Catharine Bull Scholarship officer

Skye Stevenson Education officer

Mary Henn Technical officer

David John Technical advisor

Catherine Rose Training officer

Catherine Peacock Technical & research administrator

Joanne Needham Casework officer

Elgan Jones Casework officer

Rachel Broomfield Casework officer

Victoria West Archive officer

Lucy Stewart SPAB Scotland officer

Deirdre Keeley SPAB Ireland officer

Louise Simson Properties list officer

Neil Faulks IT advisor

Alexandra Banister Officer to the board

Chi-Wei Clifford-Frith Director & projects team assistant

Merlin Lewis Casework support officer

Silvia McMenamin Mills Section administrator

Felicity Martin, Douglas Kent, Matthew Slocombe

Denise Burrows Editorial assistance

The Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings, 37 Spital Square, London, E1 6DY T. 020 7377 1644 E. info@spab.org.uk W. spab.org.uk @SPAB 1877 ISSN 2051-4239

A charitable company limited by guarantee registered in England and Wales. Company no: 5743962 Charity no: 1113753 Scottish charity no: SC039244 Registered in Ireland: 20158736 Letters: letters@spab.org.uk

Hall-McCartney Ltd, Heritage House, PO Box 21, Baldock, Hertfordshire, SG7 5AH 01462 896688 admin@hall-mccartney.co.uk

Published and printed on behalf of SPAB by CABBELLS

Alban Row, 27-31 Verulam Road, St Albans, Hertfordshire AL3 4DG T. 01727 893 894 E. info@cabbells.co.uk W. www.cabbells.co.uk

Peter Davies E. peter@centuryone.uk

Sean McNamara E. creative@centuryone.uk

Reproduction of content of this magazine in whole or in part is prohibited without prior written permission of the

Views expressed are not necessarily those of the

Products and services advertised

this magazine are not necessarily

You should make your own

by the

seek professional

When you have finished with this magazine please recycle it.

Help us celebrate excellence in building conservation. Our awards champion great initiatives, innovative projects and exceptional craftspeople.

One of our new awards – Best Loved – is for the buildings that are well-maintained and loved by their community or their owner. This award recognises the people who carry out all-important maintenance and look after the building, from owners to professionals to volunteers. There are two categories: public building and private building. Vote for your favourites from our shortlist of worthy winners on our website.

Voting is open until 31 October and the winners will be announced at our Awards Ceremony on 3 November.

Can you envision a new future for a neglected historic building? Our Philip Webb Award is a design competition open

to all Part II students at UK and Irish Schools of Architecture and recent graduates. Applications close at 5pm on 12 September. This year the Award is sponsored by Terra Measurement. Apply on our website.

The inaugural SPAB Heritage Awards will be presented at Conway Hall, the beautiful 1920s home of the Ethical Society, in Red Lion Square, London. We are thrilled to announce that designer, writer and TV presenter Kevin McCloud will be hosting the evening, which will take place on Thursday 3 November to audiences both in person and online. Look out for tickets on our website from September. If you can’t make it to London, join us online and watch our free livestream, register your place online in the autumn.

The SPAB Heritage Awards headline sponsor is Storm Windows. Thank you also to Terra Measurement, sponsor of the Philip Webb Award and Keymer Tiles, sponsor of the Sustainable Heritage Award.

Visit our website to find out more: www.spab.org.uk/get-involved/ awards or get in touch: awards@ spab.org.uk

The Society has been discussing new proposals for Clandon Park with the National Trust. The house, designed by Leoni and dating from the early 18th century, was severely damaged by fire in 2015. In this state of distress it has acquired a new forlorn beauty.

Following an insurance settlement, initial plans have been reviewed and revised proposals developed. The Society feels a sensible and appropriate course of action is being pursued, with the fire-damaged shell to be conserved and re-roofed as first phase. Although skills training seems likely to be embedded into a project, restoration is not the intention. The building is expected to be treated as a showcase for the construction of an 18th century country house, with its damaged state allowing all strands of its fascinating history to be seen and interpreted.

This presentation will set Clandon apart from 18th century houses open to view, with more the flavour of Woodchester Mansion, Gloucestershire, or Wimborne St Giles House, Dorset, where the bones of the building are left on show.

Right Damage and survival within the building

Repairs to the SPAB’s post mill at Kibworth Harcourt – the last of its kind in Leicestershire – are now complete. This work was made possible by the generosity of Enid Lamb, whose legacy allowed the work to happen.

Also deserving praise are all those who

assisted with the project – notably engineer Naomi Hatton, millwrights Dorothea, mills adviser Luke Bonwick, metalwork specialist Carl Edwards and brickwork specialist Lynn Mathias. Mills Section Chair, Mildred Cookson, and Vice Chair, Steve Temple, were closely involved and SPAB Special Operations Officer Jonny Garlick helped coordinate the project. Dr James Wright assisted with a fascinating graffiti survey and Terra Measurement provided invaluable digital surveying support. Dr Martin Bridge undertook dendrochronological research, with Historic England’s support, and established that the mill’s main post dates

from c1600 – some 170 years older than the other timbers in the mill.

Kibworth Harcourt is once again a splendid local landmark and a machine capable of being operated.

The generosity of members allows the SPAB to continue its work. This help comes in the form of voluntary assistance, membership subscriptions, donations and legacies. Legacies are a key component of our annual operating income. David Wynn of Fladbury Mill, Worcestershire, was one of those vital legators.

We are extremely grateful to all those willing to remember the SPAB in their Will. This support provides an enduring legacy that helps protect old buildings and train those who care for or repair them. During Remember a Charity Week, 5-11 September 2022, we hope all members and supporters of the SPAB will consider including the Society in their Will. This was a decision taken by David Wynn, to whom we are enormously grateful. David sadly died in 2021 after a long and productive life. As a young man, he had emigrated from New Zealand to the UK. Here, he developed a varied and fruitful career, involving architecture, engineering, property renovation and even heritage tour-guiding. With his wife Angela, who managed art exhibitions, David took on Fladbury Mill in Worcestershire after assisting the mill’s previous owner Jack Crabtree – a SPAB member and owner of the well-known electrical engineering firm. David was Jack’s natural successor as

WE NEED YOUR VOTES!

Thank you to all the members who have put themselves forward as candidates in this year’s election. We are always heartened by your willingness to serve and support the SPAB.

custodian of the mill. In 2019 David held discussions with the SPAB, his lawyers and his executors and decided to leave the mill, its contents and an amount of money to the Society.

Fladbury Mill is located on the river Avon, between Evesham and Pershore. It shares a weir with Cropthorne Mill on the other side of the river, next to which is a lock for narrow boats. The current Fladbury Mill is Grade II-listed and dates from the 17th century, but the mill site has earlier origins. Much of the current building is of 18th century date and accommodation includes the mill house as well as a separate flat.

Fladbury Mill has great local importance, but is also of national significance. As long ago as 1888, electricity from a waterwheel at the mill was used to power a local country house as well as two other houses in the village. By 1900, two turbines had been installed and a company established which produced power for Fladbury’s street lighting as well as domestic lighting at a

The participation and voices of new Guardians will be crucial in helping to deliver exciting plans for 2023 and beyond. The election is an opportunity for our membership to shape the future of the SPAB and we want to hear from you!

Enclosed in this issue you will find the voting papers and an election booklet with candidate statements and details about the committees. You can also download the election booklet in the ‘Governance’ section of the Members’ Area of our website. Please take the time to review the nominees and make your selection. All ballots are strictly confidential.

penny per light per night. This use ceased by the 1920s, but in the late 1970s a new turbine was installed which now provides electricity for all purposes at the mill, generating more than can currently be used.

The SPAB is grateful to David Wynn’s executors for their support and help and we expect to gain possession of Fladbury Mill by the end of 2022. We have commissioned a business plan for the site, but its likely future uses will include a site for SPAB courses, holiday lets and the exportation of sustainable electricity. We will report further as plans develop.

All gifts in Wills, no matter the size, leave a lasting impact. If, after looking after your loved ones, you decide to remember the SPAB in your Will, please tell us about your wishes. Contact our development team 020 7456 0917 or email development@ spab.org.uk. You can also notify us via our website www.spab.org.uk/getinvolved/legacies

Make sure you submit your vote so that it arrives at our office in London by Friday 21 October 2022. We recommend giving a week for post to be delivered. New Guardians will be announced in the winter issue of the SPAB Magazine

If you have any questions, please contact Chi-Wei Clifford-Frith, director and projects team assistant (director@ spab.org.uk). If you need assistance logging in to the member’s section of the website, please contact our membership officer Lucy Jacob (membership@spab.org.uk).

PROJECT UPDATE

Following this summer’s Working Party, the main phase of the project is ready to begin...

Recent work at the Old House Project has focused on the finalisation of repair details for the west wall and conservation work to other masonry and the east end timber frame. Thanks to support from Historic England, a thoughtful and conservative structural repair proposal has been devised by Malcolm Fryer architects and structural engineer Ed Morton. This year’s works have been out to tender, with Owlsworth IJP now appointed.

Thought has also been given to a range of other issues including the

archaeological conditions of our listed buildings and planning consents, site drainage, services and insulation.

In advance of the main phase of work, some aspects of the planned repair were carried out by specialists and participants involved in this year’s Working Party (see item on page 11).

For further information, see the Old House Project pages of the SPAB website, including a new Project Book chapter on scaffolding

Above Movement of the west wall is closely monitored

Right Historic England visit after awarding a £36,000 grant

This year’s summer Working Party in Kent was one of our biggest ever – 98 volunteers, specialists and staff gathered to help repair our Old House Project and neighbouring Boxley Abbey.

We believe that the best way to learn traditional building skills is through hands-on experience. Our Working Parties are a fun way to learn from some of the country’s leading craftspeople in a relaxed setting. For a week professionals, students and enthusiasts are united in their efforts to help a historic building, working, learning and camping together.

There was a wealth of activities for participants to try and a huge amount of work was achieved, despite the hot weather.

We carried out timber repairs to the medieval brewhouse/barn, giving volunteers the rare chance to hew timber in the traditional way.

Under guidance of our archaeologist Graham Keevil, volunteers and members from local archaeological groups (MAAG and HAARG) dug small trenches in the garden at St Andrews and in a field within Boxley Abbey’s inner precinct.

Experts and volunteers also worked on the Abbey’s historic garden walls –carrying out repointing, soft-capping and gauged brickwork repairs. Our supporters Terra Measurement led volunteers in conducting a drone survey and photogrammetry. Participants were also able to try high-level rope access; learn how to mix lime mortar and, following experiments last year, witness an experimental burn in our field kiln of local material septaria to produce a natural cement.

They also enjoyed a boat trip down the Medway, a guided tour of Rochester Cathedral and a celebratory barbeque at the end of the week. Our 2022 millwright Fellow Owen Bushell demonstrated how to make a clay oven and prepared pizzas for everyone in the evenings using flour

milled by 2009 SPAB Fellow Karl Grevatt at Charlecote Mill.

Above This year’s group in the Rose Garden at Boxley Abbey

Left Repairs to Boxley Abbey’s historic garden walls

Right Participants were able to try high rope access under the guidance of experts

We were pleased to offer six bursaries to attendees this year, to help cover their travel, equipment and other costs. Student Nadim Jacequemond explained: “Equivalent opportunities for hands-on experience were too expensive for me, so I’m very grateful to receive a bursary for the Working Party... It’s been fantastic, given me inspiration and confidence. A week isn’t long enough, I don’t want it to end!”

The public Open Day was a great success and we welcomed over 70 locals and supporters to the site.

Visitors enjoyed a talk from historian Dr Elizabeth Eastlake, an expert on Boxley Abbey, and guided tours of the Old House Project.

Our Working Parties couldn’t happen without a great number of people generously sharing their skills and giving their time. We also had generous support from William & Edith Oldham Charitable Trust and The Kent Archaeological Society, with kind donations of goods from Gallagher’s Quarry, Oxted Quarry, UC Build and ME Fencing and Landscaping. Our sincere thanks to all our volunteers, experts, visitors and our hosts who made it such a brilliant week.

The Levelling-Up and Regeneration Bill, published in May 2022, contains five clauses which directly affect historic buildings and sites. All of these clauses are welcomed by the SPAB since they close loopholes, make it easier to use existing powers or resolve discrepancies between planning and listed building consent regimes.

The most significant clause (185) goes somewhat beyond the others in introducing a requirement that all local authorities in England should maintain a Historic Environment Record (HER). This is already a statutory requirement in Wales. In England, many authorities already have a HER in place, but some do not. HERs provide a valuable resource for all interested in or working with the historic environment, bringing together records about listed buildings and scheduled monuments, archaeological finds and landscape features.

Key to the success of our Working Parties, like any building project, is preparation. We are tremendously excited that in September we are holding a Working Party at the beautiful ruined church of St Mary’s, Caerau outside Cardiff. But in advance we need to source local materials and establish local partnerships.

St Mary’s, Caerau is a medieval church on the site of an Iron Age hillfort, now a fragile ruin lovingly cared for by a local Friends group. To repair it sympathetically we needed to create a mortar that would match what’s been used at St Mary’s in the past. Mortar analysis showed that a local Blue Lias limestone would be suitable.

In May, SPAB staff and specialists along with local craftspeople, volunteers and partners gathered at St Fagan’s National Museum of History to carry out a lime burn. The field kiln – built by the British Limes Forum 20 years ago – is a replica of a medieval

kiln at Cilgerran Castle. The Blue Lias limestone and refractory bricks were kindly provided by Tarmac’s Aberthaw Cement Works and Quarry.

We were delighted to welcome local volunteers and young people to the site.

SPAB Fellows and stonemasons Thom Kinghorn-Evans and Luke O’Hanlon were joined by lime specialists Hugh Conway Morris and Stafford Holmes of our Technical and Research Committee.

The two successful burns mean that we are now ready to help repair St Mary’s, Caerau and the results will feed into our research into the vernacular use of British hydraulic limes.

We are very grateful to Cadw who generously supported this project, along with our partners St Fagans National Museum of History, Cardiff University, CAER Heritage Project and Tarmac.

Ongoing maintenance is one of the pillars of the SPAB Approach to old buildings. Maintaining a building involves simple, regular checks which can make a huge difference to its condition, lifespan and energy efficiency.

When carrying out any maintenance tasks, wear protective gloves, and if you’re climbing ladders or accessing high places, make sure to have someone with you.

Our annual awareness-raising campaign Maintenance Week runs 18-25 November.

Recommended maintenance tasks in the autumn:

n Clear any plants, leaves and silt from gutters and rainwater pipes.

n Check roofs for signs of damage. Debris on the ground from broken tiles

or missing slates and tiles indicate there may be a problem.

n Check that the heating system is working properly with no leaks.

n Clear away any plants from around the base of the walls, gulleys and drains. n Make sure that water tanks and exposed water pipes are protected from frost. n Ensure any airbricks or under floor ventilators are free from obstruction. n Cast iron gutters may require repainting.

n Check masonry for signs of damage. Seek advice on any deeply eroded mortar joints, cracks or signs of movement.

n Get involved in #MaintenanceWeek (18-25 November) and #GuttersDay (25 November) on social media. Follow us on Instagram, Facebook, Twitter and LinkedIn @SPAB1877

Without care, beloved furnishings and fittings will suffer from damage and decay as well. In our online webinars, experts from Trusted Conservators share tips on spotting problems, preventing damage and safe cleaning techniques for historic interiors. Watch our pre-recorded Good Housekeeping webinars from 18 November until 31 January 2023. For details, visit the SPAB website: spab.org.uk/whats-on

Search our online resources spab.org. uk/advice or call our free helpline on weekday mornings 020 7456 0916 to speak to experts. Our advice line is generously supported by Historic England.

Collaboration with other organisations is one of the best ways to reach a wider audience. This year the regular joint conference between the Sustainable Traditional Buildings Alliance (STBA) and the SPAB is being hosted by SPAB Scotland in Edinburgh, and we are very excited to be able to bring you this focused CPD event.

With the retrofit and green agenda firmly in the public eye, we bring you a selection of leading speakers on these topics and provide expert analysis of WUFI, embodied carbon analysis, training opportunities, and much more. Confirmed speakers include Nigel Griffiths, Kirsty Cassels, John Butler and Roger Curtis. The conference will be held from 9.30am - 4.30pm on 12 October. Our venue is the stunning Dovecot Studios, Edinburgh, which is an exemplary conversion of a disused public baths and now housing tapestry studios, conference facilities, exhibition space, a shop and café.

Tickets are £85, with reduced rates available for concessions and students. Book your place on our website or email scotland@spab.org.uk for further information.

SPAB IRELAND

SPAB Ireland has had an extremely busy calendar of events around the theme of traditional buildings and sustainability. The lecture series was launched in the beautiful setting of James Gandon’s Custom House in Dublin. Frank Keohane gave a captivating talk highlighting the importance of surveys and analysis of traditional buildings to understand the parameters before proceeding with potentially unsuitable works.

The series continued with lectures from Feidhlim Harty, Roger Hunt and Féile Butler on the topics of sustainable building practices, with advice on approaches to sustainable development for traditional and vernacular buildings.

SPAB Ireland exhibited at Dublin’s Heritage Buildings Show in June, with on-site practical demonstrations of traditional pointing techniques and soft capping, and a talk on the importance of preventative maintenance presented by SPAB Ireland chair Shóna O’Keeffe. We were delighted to have the opportunity to discuss our initiatives with Minister of State for

Heritage, Malcom Noonan, who officially launched the event.

Also in June, SPAB Ireland held a joint workshop with the Building Limes Forum Ireland at Shankill Castle. The event focused on plasters and renders, and looked at both traditional approaches using lime/earth plasters applied directly onto solid walls and an alternative contemporary approach with lime plasters incorporating insulating cork/ hemp/expanded clay and diatomaceous earth additives.

Speakers included Jacqui Donnelly, Department of Housing, Local Government and Heritage, and Peter Cox of Carrig Conservation. We enjoyed demonstrations from specialist practitioners throughout Ireland and the workshop concluded with a debate chaired by Dr Jason Bolton, which helped to inform owners of traditional buildings of the options to improve the energy efficiency and sustainability of their homes.

Many important and vulnerable historic buildings in Wales are looked after by small rural communities. We recognise the importance of making our educational activities available more widely in Wales, and so, with generous funding from Cadw, we offered free training to over 35 local volunteers in August. We gathered at two beautiful churches in North Wales – St Tysilio’s Church, Llanymynech and St Mary’s Church, Caerhun.

Volunteers who care for churches are likely to be the first to notice problems, so we hope that these free courses –along with a Welsh-language video series on church maintenance which we launched earlier this year – will help them

to understand their faith building and take practical action to look after it.

Simon Baldon, churchwarden at St. Mary`s Caerhun said: “the simple but highly relevant and informative discussions generated by the seminar will have a lasting impact here in this Parish.” Thanks to all who came and to Cadw for their support.

WHEN I FIRST SAW THE CALL for member repair projects, my interest was piqued. We had put a lot of blood, sweat and tears (not to mention capital) into our project and I was pretty proud of what we had achieved, especially as my wife Sarah and I had virtually no prior knowledge or experience of caring for a traditional property.

I began to think about what we have learnt in the process and how this learning might be useful for others in a similar situation. Crucially, I also reflected on what our motivations have been for attempting to take a ‘SPAB Approach’ and the benefits of doing so.

We have what I would describe as a “nice wee hoose” situated in a conservation area in the attractive Stirlingshire village of Drymen, near Loch Lomond, Scotland. The house itself has no particular heritage significance, but it undoubtedly makes some contribution to the overall character of the village.

When we bought the house in summer 2015, the details rather grandiosely described it as a ‘semidetached Victorian sandstone villa’. The house was originally built as two dwellings, now conjoined as one via

some not particularly sensitive internal jiggery-pokery in the 1980s.

On viewing the house, even to the completely uninitiated like us, it was obvious that there were problems with damp. An historic building conservator friend’s advice was: “This house has been standing for 160 years, it’s not going to fall down any time soon, it just needs some TLC.” This prompted us to commission a damp survey from a surveyor specialising in traditional buildings. The results were not terrifying enough to put us off the purchase and gave us a clear list of priorities to tackle.

Above Early 1900s image of Drymen. The gable end of Peter’s house is visible behind the rowan tree and the whitewashed sweet shop (now sadly demolished)

Below Chimney project completed summer 2022 and closely modelled from the above historic image

n Conservation joinery to dormer windows to resolve historic design flaws that had contributed to water ingress and rot to structural timbers.

n Removal of cement render on main gable, conservation masonry to make good rubble wall, re-point in lime. n Conservation masonry to make good party-wall, installation of lead soakers and mortar fillet, lime harl, lime wash.

n Reinstate original three pot chimney at main gable with coursed rubble and dressed ashlar quoins (design closely informed by historic image) to allow for two functioning fireplaces.

What we now know, of course, is that the house was subject to many of the horrors meted out on traditional properties during periods of ‘improvement’ in the mid-late 20th century.

My mission over the last seven years has been to fundamentally improve how the house functions and its living environment (not least as we now have two young children). With that in mind, below is a list of the major external capital works we have undertaken thus far.

n Complete re-roofing in Spanish slate replacing traditional Scots slate (a

notable regret – see below!)

n Removal of cement mortar and re-pointing main elevation in lime

n Replacement of rotten dormer finials (new wooden finials turned and dressed in lead by lead specialist)

The specialist damp survey was instrumental to our understanding and was our first lengthy engagement with an expert. Their report prompted further reading of resources from SPAB and Historic Environment Scotland and provided evidence that allowed us to negotiate a reduction in the asking price and justification to lenders for not using inappropriate industry standard damp treatments.

Our initial approach to finding tradespeople was through the internet. At the time, we didn’t have a sense at all of what makes a good contractor and after a poor experience with one contractor we were fortunate to

My mission over the last seven years has been to fundamentally improve how the house functionsMain elevation and gable of the house

stumble across SPAB Fellow Peter McCluskey (roofer) who ended up running many of the projects above. Speaking to the SPAB and asking around locally can help with suitable trade recommendations.

We certainly rushed into our re-roofing project and this is our one big regret. We were offered some questionable advice and, rather than commissioning a more detailed roof survey, we went ahead with tendering for a roofing project that was subsequently undertaken in one of the wettest Decembers on record (2015).

It’s painfully obvious now that we should have lived with our house before making any big decisions about capital projects. In practical terms, this would have given us more time to

read up on guidance, take advice and pinpoint issues under different weather conditions. Less obviously perhaps, getting to know neighbours can lead to interesting conversations about the history of the house and access to useful sources of evidence including historic images. I really wish we had used a specialist contractor and used reclaimed Scots slate, rather than Spanish.

If we were ever to buy an old property again, my inclination would be to do all the invasive capital works in one go at the start before moving into the house. This would be informed by engagement with experts and specialist trades, and commissioning of surveys prior to purchase to allow an accurate picture of cost and duration.

The more incremental approach we have taken has been quite painful at times – living in a building site may seem romantic on the TV but throw in a growing family, pressured jobs and very limited free time and it soon becomes a pretty stressful existence.

And finally, it goes without saying, but doing invasive external works at the most clement time of year is key. For our recent projects we have carefully negotiated works being undertaken in April-June.

So why take a SPAB Approach? These are questions I’ve pondered given the mounting costs of our project; certainly the market value of our property would not reflect the price tag of the above... yet.

The evidence for taking a conservation approach was clear to us in terms of improving and maintaining functionality of the building and the greater longevity of the work undertaken. But why spend more on a painstaking conservation approach if you only plan to own the property for a few years?

The way we have reconciled our costs is that we have invested our capital on external aspects of the house and really tried to bring back the critical aspects of functionality determined by appropriate roofing, lead detailing, rainwater goods, masonry and use of lime. Internally though we have sought much more of a compromise – yes we have retained original lime plaster where possible but there are large patches of multi-finish as well. We don’t have a bespoke kitchen from a local cabinet maker and we have used off-the-shelf paint from a well-known company in Dorset.

In terms of timescales for return on our investment, we will certainly live in our house for at least 10+ years. And soon we will do a small sensitive extension with oak, glass and zinc to give us a more workable family kitchen. In short, I would expect the costs and benefits of our expensive capital works to begin to balance out over this timeframe.

But taking a step back from this analytical approach, I definitely have a bit of a warm fuzzy feeling when I look at the house. Hopefully our TLC has helped secure its existence for another 160 years of simple, domestic functionality.

Some photos of our 2022 Scholars and Fellows a few months into their training schemes...

Top Scholars and Fellows in discussion with Morwenna Slade, Historic England’s Head of Historic Buildings Climate Change at the SPAB’s Old House Project. Historic England support both programmes

Bottom left Scholars and Fellows briefed by Fellowship Officer Pip Soodeen under the shade of an ancient cedar tree at the 2022 Working Party at Boxley Abbey

Bottom right Fellows Daahir and Steve learn to thatch with 1999 SPAB Fellow Tom Dunbar in Somerset

Top left The group on a sketching day in central London

Bottom left 2022 Scholars Serena, Katie, Jacob and Sinead visit Keymer Tiles who make handmade clay roof tiles in Surrey

Right The group practice traditional signwriting with Owen Bushell at the workshop of 2019 Scholar Christian Montez

Our Scholarship is a nine-month training scheme for conservation professionals, usually architects, surveyors and engineers. The Fellowship is a six-month training scheme for craftspeople, spread out over nine months.

Scholars and Fellows visit some of the country’s most fascinating heritage projects to deepen their knowledge and explore the challenges surrounding repairing historic buildings. Teaching is based on site visits, with an emphasis on the practical approach.

There are no course fees and the SPAB provides a bursary for travel and living expenses. To find out more and apply, visit our website or contact us education@spab.org.uk

“The Scholarship has been an opportunity for me to challenge, change and to gain confidence… learning from some of the best conservation professionals throughout the UK. Whether it be architects, engineers, surveyors or craftspeople, we all have an important role to play in securing the future of our historic buildings and I want to play my part using the extra passion and experience the Scholarship has given me.” Amy Redman, 2021 Scholar.

We’re adding new courses and events all the time so visit the What’s On section of our website for more information. To receive regular updates about our new courses and events direct to your inbox, sign up:

Date: 15 September 2022

Venue: Heritage Skills Centre (National Trust), Coleshill Home Farm, near Swindon Price: £165 per person

This introductory, one-day course led by expert tutors is ideal for anyone new to using lime in building or keen to expand their basic understanding. Through a combination of illustrated talks and demonstrations, it will explain the different forms of lime available and look at a range of uses, from pointing to plastering and lime washing.

This beginner/intermediate course will appeal to builders already working with lime and looking to extend their

Date: 16 September 2022

Venue: Heritage Skills Centre (National Trust), Coleshill Home Farm, near Swindon Price: £165 per person

knowledge, or who want to begin using lime. It is also suitable for owners of period houses or other old buildings looking to develop their understanding of traditional materials, and specifiers wishing to develop or enhance their understanding of lime and its many applications.

video and demonstrations, it will provide insight into hot limes and their use.

Date: 7 - 8 October 2022

Venue: Heritage Skills Centre (National Trust), Coleshill Home Farm, near Swindon Price: £165 per person (FULLY BOOKED - please join the waiting list)

This popular, practical course covers the mixing and application of lime plaster to lath, masonry and modern substrates, which includes pricking up and base coats, float coats and setting coats. It provides a brief introduction to running a cornice in-situ. Ideally, course participants should have practical plastering skills, and experienced plasterers used to working in gypsum will particularly benefit from the course. We also welcome anyone interested in learning about plain lime plastering for their home or old building(s) under their care. The tutors are knowledgeable lime plasterers with decades of onsite experience.

This one-day course, led by expert tutor Nigel Copsey, is ideal for anyone with basic knowledge of lime and who wants to explore the use of hot mixes in more detail. Through a combination of illustrated talks,

Date: 12 October 2022

Venue: Dovecot Studios, Edinburgh Price: £85 per person - non-members £75 per person - STBA / SPAB members

Bursaries - please enquire to: education@spab.org.uk

Concessions - please contact us with your circumstances: education@spab.org.uk

The popular STBA / SPAB annual conference returns in-person this autumn for a full day of presentations and Q&A sessions by UK experts in the field. With retrofit and the green agenda

This intermediate course is especially relevant for builders already working with lime and looking to extend their knowledge and use of hot mixes, and to specifiers wishing to develop or enhance their understanding of hot lime and its applications. It will also appeal to anyone carrying out practical building projects who is familiar with lime but interested in learning more about hot mixes.

firmly in the eye of the public, SPAB Scotland and STBA bring you a selection of speakers who will dive deeper into these topics and provide expert analysis of WUFI, embodied carbon analysis, training opportunities, and much more. The conference will be held at historic Dovecot Studios in Edinburgh Old Town.

accompanied by a series of live online Q&A sessions with speakers and site hosts. The online format provides delegates with an extended learning period until early December, enabling them to view content at their own pace, in addition to offering at least 30 minutes per speaker

for questions. All pre-recorded content will be made available a few weeks before the course date so you have plenty of time to view and consider the materials in advance. Furthermore, the course is now accompanied by our Repair of Old Buildings Course Handbook: a series of articles written by specialists on historic building repair topics, which is provided to all delegates and is exclusive to the course.

Date: November 2022 - January 2023

Price: £40 per person

£18 per person - students

For Maintenance Week, we are re-releasing the recordings from the hugely popular SPAB / Icon 2021-22 Good Housekeeping webinars to watch on demand for a limited time. The talks, presented by experts from Trusted Conservators, focus on regular care (with tips on checking condition, spotting problems, protective and preventative measures) to slow deterioration, safe cleaning techniques, materials and tools. The presentations focus on historic and vintage elements and objects, but the principles are also relevant to more contemporary fixtures and contents.

The presentations from the recorded webinars cover: Agents of Change (covering the wide range of biological, physical and chemical threats to interiors); Hard and Soft Surfaces (including floors, ceramics and decorative stone, metals, windows and mirrors, carpets and rugs, curtains and upholstery); Paper (prints and drawings, wallpaper); Painted Surfaces and Paintings. The total learning time provided by these presentations is just over six hours. You will receive the recording links upon registration, and you can stop and return to the recordings anytime during the access period (ends February 2023).

Date: October - November 2022

Price: £110 per person

This modular, self-paced online course is designed to help you understand the construction and performance of traditional buildings and how to tackle common problems. Topics also covered include: lime and its uses in the

construction and repair of traditional buildings; the legal framework surrounding works to property; advice on working with professionals and local authorities. There is a choice of two dates for a live online group Q&A session with the course tutor – please see our website for more information.

This introductory-level course is relevant to owners and managers of period properties, but also for professionals who may need to brief their clients on understanding their old house. CPD certificates will be available on request.

In its casework the SPAB gives advice to planning authorities, owners and professionals. Cases arise from information received about neglected buildings or planning proposals. Councils in England and Wales are obliged to notify the SPAB of applications involving demolition work to listed buildings. We also hear from parishes, dioceses and cathedrals when certain works to listed churches are proposed. Casework is one the key ways the SPAB campaigns for the future of historic buildings.

The Bevis Marks Synagogue stands just a stone’s throw from the Society’s offices and is a fascinating building with an equally fascinating history. Listed at Grade I, it was constructed in 1701, making it the oldest surviving synagogue in the United Kingdom. The ‘Cathedral Synagogue’ of British Jewry akin to St Paul’s for Christians, it is the only synagogue in the world to have held continuous worship since the time of its construction. It is also the only non-Christian house of worship in the City of London.

The building itself is a plain rectangle of red brick with modest dressings of Portland stone. The interior is equally plain, with a gallery supported on Doric columns to three sides. The fittings are remarkably complete and little altered from the original arrangement, some being older than the present building. There is a finely carved echal or reredos, and seven large brass chandeliers. Its little altered state means the interior is of exceptional historic interest.

In 2019 the Society was made aware of an application for a new tower at 33 Creechurch Lane, in the immediate vicinity of the Synagogue. The 21-storey tower would replace a low-rise 1970s office development east of Foster & Partners’ Gherkin. We wrote expressing our concern that the proposed new development would have a negative impact on the character and significance of the Grade I-listed building.

In early 2021 the Synagogue got in touch to let us know that a revised application had been submitted for a 19-storey building on this site together with an application for another building of 48 storeys sited somewhat further away at 31 Bury Street.

While welcoming the additional greening of the scheme for the Creechurch Lane building, we were still concerned as to the scale of the building. We noted that the Heritage Assessments submitted by the applicant recognised the high communal value held by the Synagogue but had to conclude that the proposals do not respond to this in a meaningful way.

The application argued that the Synagogue is ‘already surrounded by buildings of a greater mass and scale’. We do not accept this as an argument, considering that the height and proximity of the new building was such that it

would adversely affect the setting of the Synagogue. We also said that the revised façade treatment proposed would only slightly lessen the adverse effect of the overall scale and massing of the new building. In relation to 31 Bury Street, we agreed with Historic England’s view that the proposed development, while not immediately adjacent, would further diminish the sense of seclusion within the courtyard of the Synagogue by blocking views of the sky.

In October 2021 the City of London’s famously prodevelopment planning committee rejected the application for 31 Bury Street, despite the fact that it had been recommended for approval. As the Architects’ Journal recently pointed out, the City of London has the highest planning approval rate in the country, granting 99 per cent of applications in 2020. We were equally delighted to hear that the application relating to 33 Creechurch Street was recently withdrawn.

Merlin joined the SPAB’s Casework Team at the start of April this year. Alongside his casework duties, he is also working towards the completion of his Master’s degree in Architectural Conservation at the University of Edinburgh.

Like others in the Society, his route into the world of building conservation has been varied. After completing an undergraduate degree in human geography he joined an e-commerce start up in London and subsequently went on to work for antiques restorer-turned-dealer Christopher Howe, a consistent and vocal champion of traditional techniques and craftspeople. Christopher instilled in him a deep appreciation for materials and makers, and emphasised the importance of considering historic fabric in relation to the context in which it was formed as well as the context in which it may now be found.

Later returning to the Scottish Borders and observing the position of historic textiles mills within the region’s cultural memory, further questions were prompted about how and why historic buildings are valued, and what role they can play in a modern world. A serendipitous tour of Robert Adam’s Gosford House in the summer of 2019, organised by SPAB Scotland, came at just the right time, introducing Merlin to the world of building conservation and bringing together an enthusiasm for architecture, traditional techniques and social history.

Living in Edinburgh, Merlin also offers support to SPAB Scotland on a voluntary basis. He was involved in the, Scottish Mills Weekend in Perth in May this year and alongside the Society’s Scotland Officer he continues to bolster SPAB Scotland’s casework impact north of the border. Of particular interest to him are Scotland’s own building typologies, and he continues to learn and improve his understanding of the past and potential uses of lime in Scotland’s construction story.

Constructed in 1701, it is the oldest surviving synagogue in the UK, the only synagogue in the world to have held continuous worship since the time of its construction and the only non-Christian house of worship in the City of LondonAbove The fine interior is little altered and of exceptional interest Photo Caroe Architecture Ltd David Jackson

Earlier this year Herefordshire Council refused an application for listed building consent for a two-storey extension to replace the existing single storey side extensions to the Grade II-listed 3 Park Terrace. This charming timber framed cottage is the end of a terrace of three and is believed to date from the 17th century.

The proposed two-storey extension was to the south gable and set back slightly from the main elevation. The ground floor was largely glazed, with weather boarding to the first floor and rear elevation. Internally the proposals involved the removal of a section of the gable wall at ground floor level, reconfiguring the layout and creating a larger dining area. On the first floor it was proposed to puncture the gable wall to create access through to a new third bedroom with en suite. The existing first floor window in the gable, which currently serves the second bedroom, was to be blocked and a new aperture created in the rear wall of the cottage.

If built, the proposed extension would have resulted in harm to the building’s special interest and structural integrity. The proposed works required the truncation of several historic timbers and the loss of approximately two-thirds of the ground floor gable wall.

Following the refusal, a new application was submitted earlier this year. The revised scheme is again for a two-storey extension to the gable but is wider and deeper in plan, largely

owing to the inclusion of a new staircase. The benefit of this arrangement is that it would avoid many of the significantly harmful alterations to the historic fabric and structure of the previous scheme. However, despite these major improvements, the SPAB believes that the current proposals would still have a harmful impact on the listed building.

The building’s small-scale and basic form are key qualities of its significance and special interest. While we recognise that there are existing extensions to the gable, these are modest and ancillary, allowing the principal building to remain the dominant element and clearly articulated. The Society feels that the twostorey extension is considerably larger and would challenge the listed cottage. It would also cover almost all of the existing gable.

The external appearance of the extension has also been revised – now a mock timber frame design. However, this is not an improvement, and it is felt that the historicist nature of the design only exacerbates the adverse impact.

The level of detail provided in the application is basic and insufficient and the requisite clear and convincing justification also lacking.

In their consideration of the case, the SPAB’s Casework Committee wondered if the building could be extended to the rear by utilising an existing ground floor door opening to form a small link to a new addition.

While the Society has welcomed the improvements in the revised application it was felt that the proposals would still result in a level of harm that had not been justified. Consequently, we advised the planning authority that the application should either be withdrawn or refused, and that the applicant engages with the Council’s conservation officer to explore if, and how, the building might be extended.

Rachel Broomfield

Rachel Broomfield

This beautiful Cotswold stone property forms part of a picturesque group of Grade II-listed buildings consisting of the Mill House (early 18th century, remodelled in the mid-19th century), the Water Mill (formerly a corn mill, mid-17th century) and the Coach House (mid-19th century), which along with the adjacent bridge, sit around the mill pond and leat fed by the River Dikler. The group lies within the Upper Swell Conservation Area and the Cotswolds AONB in south Gloucestershire.

The converted mill retains its water wheel and some of the machinery and is attached to the Mill House which in turn is attached to the Coach House by a pitched roof link and a modern conservatory in the corner facing towards the pond. The entrance from the road leads to a parking area surrounded by the neighbouring property Old Mill Barn to the west and a lean-to car port, glass house and garden walls. The elevation facing the road with its ‘Tudor’ style windows is quite different to the rear elevations facing towards the mill pond.

We were first consulted on this application in March 2021. The proposed works included a garden room to replace the conservatory, a new outbuilding (on the site of the existing car port), various works to the windows including enlarging the kitchen one, a new external stair to the upper floor of an outbuilding and a replacement rear porch. Internally the building suffers from damp issues in some areas, obviously a very common problem in buildings so close to watercourses, and the kitchen was a very dark space.

We initially wrote a letter of advice to Cotswold District Council to explain the concerns we had about aspects of the proposals. The heritage statement, an important part of any listed building application, required development in certain areas to allow the Council and consultees to assess the full impact of the works on the buildings. Our concerns included the scale and height of the proposed new outbuilding, the enlargement of the kitchen window, and some of the internal proposals to address the damp problems. We suggested that a conservation accredited surveyor was brought in to advise on suitable repairs to address the damp which would be less harmful.

Over the next year the council helpfully consulted us on four more occasions as changes were made and new information provided. The proposals were gradually adjusted and altered, guided by advice from the council’s conservation officer and ourselves. We were really pleased that the owners and Tyack Architects engaged with us, responding to the feedback and suggestions, and by the time we were consulted for the last time in May 2022, we were delighted to be in a position where we could support the application, subject to some conditions.

It is lovely when a difficult scheme finally comes together and consent is granted, and we would like to wish the owners all the very best with this project as it progresses.

Photo Heritage of London Trust School children were invited to watch the stone masons repairing the drinking fountain at St Paul’s in Brentford

With so many drinking fountains falling into disrepair around the UK, Kathryn Ferry looks at how some authorities have reinstated their usage for the good of the community

NOT FAR FROM THE SPAB OFFICE in Spital Square is a drinking fountain designed by founding architect Philip Webb. Located on Worship Street, it forms a corner detail at the east end of the terrace of artisan dwellings built by Webb from 1861-63. These six properties replaced overcrowded slums, each one combining living accommodation, ground floor shop and rear workshop. Although the drinking fountain was unusual as a built-in feature, it was very much in keeping with the socially improving ideals of the client and part of the drinking fountain movement that was gathering pace at that time.

Webb’s drinking fountain is of characteristically simple design. Under a sharply pointed stone gable a granite basin fills the corner space, the weight of the wall above carried upon a polygonal column carved with a finely

moulded capital. Drinking fountains elsewhere could be much grander, sometimes fancy to the point of excess, and appeared in a huge variety of different styles not to mention a range of materials from carved stone to cast

iron and ceramic tiles. Many survive around the country, lots of them enjoy listed status but very few of them still actually provide any running water.

Since the 1960s and ‘70s pipes have been removed and taps taken away so that our historic drinking fountains have been reduced from functional infrastructure to mere street furniture. Whilst this transformation came about in response to the universal connection of British homes to mains drinking water, and in that respect represented a victory for public health, there is good reason to look anew at how these structures can be re-purposed to assist in cutting down our reliance on single-use plastic drinks bottles.

Though we take clean drinking water for granted now the lack of it caused serious problems for our Victorian forbears. Not only did thousands die every year from water-bourne diseases but inadequate supplies also drove hard-working labourers to quench their thirst at the pub or gin palace. Temperance campaigners argued that this alcohol dependence led to crime and destitution so, unsurprisingly, they proved keen supporters of the drinking fountain movement. This began in Liverpool in 1854 when local philanthropist Charles Pierre Melly opened the first of his 30 drinking fountains, inspired by the examples he had seen on a visit to Geneva. Places such as Leeds, Hull, Banbury, Preston and Derby followed suit and on 12 April 1859 the Metropolitan Free Drinking Fountain Association was established in London, to spread the benefits of clean water across the capital.

The Victorian building press published designs for and critiqued the wave of drinking fountains erected by public subscription and private donors. Many

The best candidates for re-instatement are in public spaces with lots of passers-by where local communities can get involved throughout the conservation processPhoto Kathryn Ferry

served a dual purpose as memorials to civic worthies and at each of Queen Victoria’s jubilees there was a new round of fountains put up in her honour. They often assumed the role of communal meeting point so the resemblance of pinnacled and crocketted Gothic designs to medieval market crosses was entirely conscious. Their location at road junctions meant, however, that many of these fountains were either demolished or moved when routes were changed in the 20th century.

The example of the ornately carved drinking fountain now outside St Paul’s Cathedral demonstrates that it is perfectly possible to relocate these structures and re-connect them. Commissioned in 1866 by the united parishes of St Lawrence Jewry and St Mary Magdelene, the fountain was originally situated in Guildhall Yard. It was taken down in 1970 and after 40 years in storage was re-erected in 2010 with a working tap.

Unfortunately, it is far easier to find examples that have been conserved as ‘heritage assets’ rather than usable drinking fountains. One among the many stands to the west of St Woolos’ Cathedral in Newport, Gwent. It was presented to the town in 1913 by a former president of the British Women’s Temperance Association and is highly unusual for being manufactured in ceramic by Doulton of Lambeth. It was moved from Belle Vue Park in 1996 but its lack of function makes it a low priority for maintenance and a target for vandalism; the tiles are now in poor condition and the redundant basin is used as an ash tray.

Since 2016 the Heritage of London Trust (HOLT) has been working to bring neglected fountains back into use. Its Director, Nicola Stacey, is concerned that council schemes have recently displayed an ‘alarming trend’ of pouring concrete into the bowls ensuring they are ‘permanently disfigured’. HOLT’s experience has shown that just putting the taps back can have a massive aesthetic impact, helping to re-engender a sense of local pride in these structures. The best candidates for re-instatement are in

public spaces with lots of passers-by where the trust can involve local communities throughout the conservation process. At St Paul’s Recreation Ground in Brentford, school children were invited to watch the stone masons repairing the drinking fountain. A recent impact survey showed that 97% of those polled thought the park looked better following the work and 72% of people also felt it was safer. Most important of all, 94% of people had used the fountain to have a drink.

Conservation costs obviously differ but in the simplest cases it can cost under £20,000 including water

connection and new taps. HOLT gives grants for drinking fountain projects in the capital and regularly advises local authorities and community groups. Fountain enthusiast Sebastian Bulmer uses his Instagram account (@sebastian.bulmer) to show the many Victorian examples ready and waiting to be renewed. On his travels he has discovered too many places where existing fountains have been so ignored that new ones have been installed right next door. Given a more joined-up approach, our historic drinking fountains could yet become shining beacons of sustainable heritage.

Most people’s vision of a land surveyor is probably of a person behind a tripod mounted with some survey equipment, waving their arm at another person holding a staff or survey pole. This impression is not only outdated but fails to recognise that a land surveyor also maps buildings, structures, mines, rivers, highways, railways and so on.

A more recent term is a ‘Geomatics Surveyor’. The term (‘géomatique’) was originally proposed in France by scientist Bernard Dubuisson at the end of the 1960s to reflect the changing techniques of a surveyor. The only problem with this title is it’s still relatively little recognised. For this reason, we are content to call ourselves ‘Geospatial Surveyors’ and ‘Spatial Data Consultants’ which reflects both what we do and how we embrace the future of 3D spatial information.

Traditionally a land surveyor’s techniques and equipment were very much ‘analogue’ and not digital. The equipment that evolved for measurement surveying, mapping and navigation included level and staff, theodolite, sextant, chains, catenary tapes, compass, etc.

These analogue techniques spanned Millennia - from ancient civilisations including the Egyptians, through the mapping of Great Britain and Ireland by John Speed and Christopher Saxton until the 1960s. Surveying and survey engineering of land and buildings was a slow and labour-intensive process.

In the late 1960s, the first Infrared Electronic Distance Measures became available, and this was the very first

Top left The famous English cartographer John Speed (1551 or 1552 – 1629)

Right Modern geospacial surveying technology

Bottom Engraving by J.B.P. Tardieu of surveying levels and other equipment

transition into digital survey and digital data. Fast forward to 2022 and we have high-speed computers and software algorithms, fast internet access and cloud-based platforms, high-definition digital imagery, high accuracy 3D laser scanners, the list goes on. All the latest technology and innovation has vastly expanded the

uses of a Geospatial Surveyor’s data and an experience friendly to the end-user.

Whether the building or site concerned is a scheduled monument, listed building or is simply one facing modification or reuse, accurate survey drawings or models are necessary to inform assessment, design and planning decisions. Drawings typically include floor plans, elevations (both external or internal), sections, ceiling plans, roof plans and potentially 3D models. Compared to sketches or approximate schematic drawings, measured survey drawings prepared with best practice methods offer accurate and comprehensive information.

What is not often seen by owners, clients or architects is the process through which a survey of this kind is carried out. We ‘capture’ buildings in 3D to extreme detail with high accuracy. In effect we create a 3D digital twin of the building on our desktop workstations, giving the ability to manipulate that building in any way we wish as part of a technical or creative process.

This high accuracy ‘copy’ of a building is a data resource which allows us not only to create survey drawings or models, but to use the data for many other valuable purposes. This brings significant benefits and adds value to the surveying process.

Despite the cutting-edge technology, equipment and software used in 3D

building and structure capture, best practice requires that the process is ‘grounded by’ established land survey and measurement principles. Best practice for heritage context surveys is detailed in the Historic England’s guidance for metric surveys.

When surveyed by experts, using best practice and high accuracy, the data is the ultimate digital documentation of a building down to fine detail. After the survey controls are set up to maintain accuracy throughout the survey areas, buildings and structures are captured with a variety of techniques, including 3D laser scanning and photogrammetry. The results measure and record all the visible surfaces in 3D and the data is formed of millions or billions of coloured 3D points. This is called a ‘point cloud’. When 3D captures take place the aim should be to achieve the highest level of accuracy possible

We are content to call ourselves ‘Geospatial Surveyors’ and ‘Spatial Data Consultants’ which reflects both what we do and how we embrace the future of 3D spatial information

through best practice methods, equipment and software. The benefit is that the resulting data offers digital documentation that can be used for many purposes over decades.

After a software process led by the surveyor, data can be manipulated and sliced in any way we choose and then traced to create accurate 2D drawings or 3D models in Computer Aided Design (CAD) packages. The data can be further processed to create textured surface models for ‘photo realistic’ visualisations. The drawings and models derived from best practice digital twin data are the most accurate possible, particularly compared to traditional methods of taking linear distances with perpendicular corners. This 3D data is the ultimate digital documentation of a building or structure creating an accurate historic record and providing a future resource for structural comparisons and degradation analysis.

There are two very simple differences

between the two methods:

Accuracy: with drawings and models created from expert digital data, the relative accuracy is within 2-10 mm.

Detail: Rather than tens or hundreds of basic linear measurements taken with low accuracy methods and applied to a sketch, a point cloud offers billions of accurate measured points. This ensures that any specific historical recording or retrofit design is appropriate to the space to which it refers to.

This is not to say that these methods completely replace sketching and contextual hand drawings. These are part of a heritage expert’s digestion and understanding when visiting a building. However, the high accuracy 3D data set can offer an immersive experience after a site has been visited which can help reference sketches and develop solutions and understanding.

The methods are complementary, and it is beneficial to every project to have both.

A final difference between the sketching in the digital twin is that all stakeholders can use the 3D digital twin and, most importantly, the property or estate owner can view, keep and use this digital asset for years to come.

Below The SPAB’s windmill at Kibworth Harcourt, Leicestershire

After your building has been captured by experts and there is a colour 3D digital twin data set available, there is much that can be done with it beyond creating drawings and 3D models. This is where the additional value really

starts to emerge because it can be used for visual inspection, structural analysis, virtual reality and visualisations/images. It can be used for fun, technical purposes, visitor experiences or marketing for decades to come. A 3D digital twin is literally an asset for the future, just like the structure or site itself.

One of the most fulfilling uses for 3D digital data is visualisations and virtual reality exploration to enable ‘digital accessibility’. For example, if a digital twin has been captured, it can be used to create an immersive experience for those who cannot view the site due to physical, financial or distance restrictions. This resource not only raises awareness and interest, but in some cases this immersive experience can be monetised by a gateway fee or a donation to help build funds for repairs.

Digital accessibility isn’t just limited to buildings, we can also capture artefacts in 3D. People can then view and ‘handle’ objects that are hidden, fragile or priceless. We can also 3D print artefacts so that people can handle them, which can be particularly fulfilling for people with visual impairments.

Understanding and repairing a building, or its features, can be greatly assisted by a digital copy in the case of a catastrophic fire or collapse.

One of the most poignant examples of this is the disaster recovery from the Notre-Dame fire. The only definitive and accurate information was some existing 3D laser scan point cloud data. This data was not commissioned strategically for historic record and survey, it was completed by an amateur surveyor called Andrew Tallon who was an art historian from Vasser University in New York State. Andrew was, by his own admission, obsessed with the beauty of the Cathedral and took holidays in Paris over a few years with the university’s 3D laser scanner and gradually built up a point cloud of the building.

Andrew sadly died in 2018 before his passion-project was complete, but the Notre- Dame recovery team has extensively used his data when working

on building geometry, timbers and stone. If Andrew had not undertaken this 3D survey, there would have been no other accurate record.

If some of the world’s cultural heritage were to collapse due to natural disaster, war or decay, it is lost forever. The most effective way to document the contextual details and geometry of potentially endangered structures is to capture them with high accuracy point cloud data.

Greatham Old Church, Hampshire. Site of the 2016 SPAB Working Party

Owning an old building can be quite a burden, particularly when it comes to the planning and financing of preventative maintenance and repair. Many old buildings have been surveyed several times, yet the resource may be lost or wasted.

To enable owners, stakeholders and guardians to have the best chance of caring for old buildings, every single penny spent on surveying should be put to good use. In this digital age, the capture of a 3D twin and the ability to offer easy access to this data, means that the resource is never lost and always available to be re-visited, used and interpreted.

Spatial data experts can offer means to view, manipulate and share data and can also advise on how other stakeholders can use the data. This can create a significant benefit and cost saving over the lifetime of a property and avoid the need to repeat surveys or work with inaccurate information.

As a first step before any work is planned, owners and managers should consider having a building captured in 3D so that the spatial data is available for immediate use and on future occasions. The data can be provided to anyone involved in a project. That way owners and managers can be sure that everyone will have consistent and accurate data and that that data will be available to use way into the future.

Patrick Bradley outlines the significant repairs undertaken to a 19th century cottage in Bellaghy, Northern Ireland

DEERPARK COTTAGE, BELLAGHY, IS a fine example of a rural vernacular Irish cottage, a regionally significant Grade B2-listed building.

The building dates back to about 1830. The dwelling is typical in form but rare in accommodation as it has a first-floor level. The house is constructed of solid stone walls, whitewashed and surmounted by a wheat straw thatched roof between cement skews with four squat chimney stacks. A rear and side lean-to extension with a corrugated iron roof are also evident.

The last known renovations to the dwelling were in 2001, but the cottage fell into a state of near disrepair after the thatched roof collapsed inwards and the house lay waterlogged for several years.

Our private client set about repairs to her late aunt’s cottage, and to bring it back to life. The internal layout has been slightly altered to allow for modern day living – additional bathrooms, an extra bedroom and a change in the location of stairs to comply with building standards – whilst retaining as many internal features as possible. Accessibility has been improved with the inclusion of a downstairs bathroom.

The exterior remains true to its historic character and all existing fabric was retained and refurbished, including a fresh coat of limewashed render and completely new thatched roof. The existing timber windows were refurbished. The rear aluminium windows were approved by the Northern Ireland Environment Agency

(NIEA) to be replaced with doubleglazed timber windows for maintenance and heat retention, due to their position on a north-eastern elevation.

The scheme was competitively tendered and awarded to Peter McErlain Contractors Ltd. Regular site visits and monthly progress meetings ensured the scheme came in under budget and on time. The client was awarded an Historic Buildings Grant from the Department of Communities to the value of £43,850 for eligible items for repair. This largely subsidised the works as the contract was valued at £156,000 and was self-funded by the client’s own pocket. The final account of the project was settled at £150,500.

Working with historic buildings can

often be unpredictable as the extent of the works can never truly be anticipated in advance. The cottage itself had been left derelict for many years and the extent of the damage was obvious once the building was cleared of vegetation. However, no contingency funds were used and all items of concern were able to be implemented into the existing works and budget with the approval of all statutory bodies.

Since completion, the building has performed to the highest standard. The solid stone wall naturally retains heat, and there is an oil-fired central heating system expressed through radiators, as well as the open fires and wood burning stoves. The walls also provide a breathable structure which is further

Far left The back of the house after the works were completed

Left Existing timber windows were repaired

Below The front of the house in about 1970

assisted with the limewashed render both externally and internally. The roof has insulation added to the underside of the rafters, with a breathable membrane, to retain the heat whilst allowing the thatch to breathe. The thatch roof over time will require maintenance and the lifespan of this is expected anywhere between 15-25 years, depending on weathering. It is so important we help preserve thatching as a craft and as an sustainable material.

The dwelling has a total area of 194 m2 /2087 ft 2 over the two storeys. This works out, before the grant aid has been deducted, at a rate of £72 per ft 2 – a phenomenal turn key rate and value for money in today’s market. Some items

The cottage itself had been left derelict for many years and the extent of the damage was obvious once the building was cleared of vegetation

such as fireplaces and hearths were original and removed from the house prior to the works commencing but all other sanitary ware, kitchen, tiles etc were a post construction sum included in the bill.

The sustainability of repair versus demolition/replacement is clear. The natural, local materials used have a low impact on the environment and produces less wastage and reduces the amount of transport required for building goods and products.

The original boundary block whitewashed wall was replicated at the road’s edge and all existing wrought iron gates were made good and repainted the striking yellow known on this site. The outbuildings of the cluster were all freshly limewashed with new timber doors to complete the renovations.

The surrounding landscape has always defined the site back and the client was determined to fully restore the gardens and plants using old photos and talking to neighbours.

The local people of Bellaghy are precious about this landmark and were delighted to see the cottage repaired and refurbished. The contractor reported that many people stopped to admire, take photos and even requested to see inside.

Deerpark Cottage has suffered from

Above The building sits comfortably within its landscape

Right Straw thatch is a beautiful, traditional and sustainable material

dereliction and neglect in recent years and has successfully been repaired to preserve its place in history. The client has shown extreme commitment and attention to detail in ensuring the cottage was finished to the highest possible standard to maintain its vernacular Irish roots.

Architect

Contractors Ltd

Following a recent visit to Nevis, John Sell traces the history of the Caribbean island and discovers four heritage sites being protected by the Nevis Historical and Conservation Society

WHEN I ASKED JAHNEL NESBITT, director of the Nevis Historical and Conservation Society (NHCS), what makes Nevis special, her instant reply was “friendliness”.

How interesting that someone whose job it is to care for the heritage and environment of this small island, just 36 square miles and with a population of only 11,500, should mention an intangible value. But not surprising when you realise that for many Nevisians intangible values, intangible culture, intangible heritage mean more than the stone and timber buildings which serve

as a reminder of the harsh history and harsh lives of their forebears.