Opening Remarks ........................................ Scott Pope

Presentation of Colors ................................. Rankin Safety Patrol

Pledge of Allegiance ................................... Rankin Safety Patrol

Singing of our National Anthem ................ Ashley Flowers

Invocation ................................................... James Ford

Dinner

Welcome ..................................................... Mayor David Moore

Recognition of Special Guests .................... James Ford

Past Inductees

Corporate Sponsors

City and County Officials

Committee Members

Special Thanks

Presentation by............................................. James Ford

Mount Holly Sports Hall of Fame Community Spirit Award

Sponsored by American & Efird ..................... Scott Pope

Presented to Vance Furr

James Mack .................................................. Gary Neely

Lee Edison Hansel, Jr. ................................. Eddie Wilson

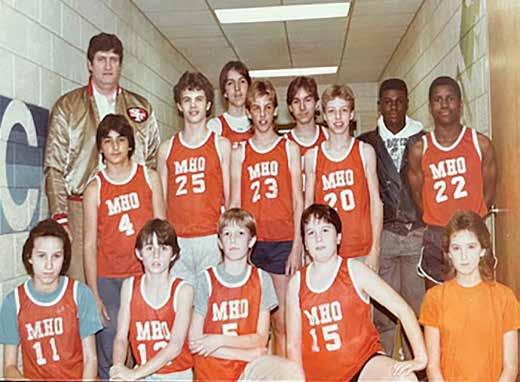

1979 E. Gaston High School baseball team Scott Pope

Jamie Summerlin ......................................... Scott Pope

Chais Schenck ............................................ Doug Smith

Cierra Brooks .............................................. Tyler Berg

Closing Remarks ......................................... Scott Pope

MHHS Song ............................................... Eddie Wilson

EGHS Song ................................................. Ashley Flowers

President - Scott Pope

Vice President - Richard Browne

Treasurer - Doug Smith

Secretary - Eddie Wilson

Committee Members - James Ford, Gary Neely and Tyler Berg

2007

Coach Delmer Wiles

Robert Black

2008

Arthur Davis

Bearl Davis

Max Davis

Wilbern Davis

Bertha Dunn

George Fincher

Neb Hollis

2009

Coach Dick Thompson

Vivian Laye Broome

Tommy Wilson

Don Killian

Ray Campbell

1963 MHHS Football Team

2010

Joe Huffstetler

John Farrar

Coach Joe Spears

Johnny Wike

1990 East Gaston Wrestling Team

Community Spirit Award Winner

Dwight Frady

2011

Bruce Bolick

Wayne Bolick

Frank Love

Perry Toomey

Scott Stewart

T.L. McManus

Jim McManus

Samuel “Dink” McManus

Community Spirit Award Winner

John Lewis

2012

Larry Hartsell

Freddy Whitt

Dawn Moose

Ronnie Harrison, Sr.

William Outen

1967 MHHS Football Team

Community Spirit Award Winner

Bobby John Rhyne

2013

J.B. Thompson

Charlie “Poss” Drumm

Doug Smith

Shane Trull

1940’s MHHS Hawkettes Basketball

1960’s MHHS Hawkettes Basketball

Community Spirit Award Winner

Sarah Nixon

2014

Lois Herring Parker

A.C. Hollar

Larry Lawing

Eddie Wilson

Tracy Black

Richard Dill

Community Spirit Award Winner

Buddie Hodges

2015

Zeb McDowell

Max Sherrill

Phil Roberts

Laura Randall Woodhead

1954-55 Hawks Baseball 1967-68 & 1968-69

Hawks Basketball

Community Spirit Award Winner

Barry Jessen

2016

Barry Grice

Derek Spears

Stephanie Frazier

Jerry Brooks

1991 East Gaston Wrestling

Community Spirit Award Winner

Aaron Goforth

2017

Eddie Wyatt, Jr.

Grant Hoffman Jr.

Carmen Baker

James Ford

East Gaston’s 1977 Golf Team

Community Spirit Award Winner

Carl Baber

2018

Tony Leroy McConnell

William Phillip White

Sue Carlton Whitley

John Logan

Jeff Lee

Hawks Baseball 1964-1967

Community Spirit Award Winner

Henry Massey

2019

1941 Hawks

Howard Horton

Sam Brown

April Harte

Tyler Berg

1978 East Gaston Football Team

Community Spirit Award Winner

Scott Pope

2020

No Inductees due to COVID-19

2021

Reggie Ballard

Donald Fortner

Mike Featherstone

Brooke Wilkinson

Scottie Holden

1992 East Gaston Wrestling

Community Spirit Award Winner

Eddie Womack

2022

Steve Hansel

Robert Nichols, Jr.

Marrio McCorkle

Stewart Hare

1956 Mount Holly Hawks Football

Community Spirit Award Winner

Harry Adams

2023

Mount Holly Girls Basketball 1959-60

John Jessen

Shelton Camp

East Gaston High Warriors 01-02

Tameron Sealey Rushing

Cameron Sealey Flachofsky

Community Spirit Award Winner

Rodney Abernathy

Lydia Frances Walls, NC State University

Pat Hartsell Scholarship

Sponsored by Larry and Jan Hartsell

Shelden Rhyan Clark, NC State University

Jane R Hansel Scholarship

Sponsored by Steve and Jane G. Hansel

Brianna McGinnis, UNC-W

Pat Hartsell Scholarship

Sponsored by Larry and Jan Hartsell

Michael Hunt, UNC-Charlotte or Gaston College

Pat Hartsell Scholarship

Sponsored by Larry and Jan Hartsell

The MHSHOF scholarship is awarded on the basis of a competitive process that considers academic achievement, extracurricular and community involvement and financial need. Four seven hundred and fifty dollar scholarships are paid directly to the recipient’s school, where the student must be enrolled and in good standing.

To be considered for this scholarship, applicants must meet the following criteria:

• A high school senior.

• Maintain a GPA of at least 3.0 on a 4.0 scale.

• Applied to a credited college or university.

• Must not be a dependent of a member of the board of the MHSHOF or of the guidance department.

• Must not be a recipient of a major scholarship of $6000 or more from another source.

The purpose of the MHSHOF Scholarship is to provide college funds to deserving students with financial need. The scholarship is paid directly to the recipient’s school for tuition. The recipient supplies the information needed to submit the payment.

Applications must be submitted on or by April 1 to the Guidance Department at East Gaston High School and Stuart Cramer High School.

* Individual Endorsement Opportunities are Available

e Mount Holly Sports Hall of Fame was established to honor our community’s rich sports history and to recognize the outstanding individuals and teams who have excelled over the last century on behalf of our city.

Our ultimate goal is to educate the community about the outstanding accomplishments of these individuals and teams, instill civic pride in our citizens and promote Mount Holly. Our emphasis on education has led us to develop a scholarship program through our local high schools.

In addition to education, the Mount Holly Sports Hall of Fame supports charitable contributions for youth groups and local civic organizations by committing to pay out 10% of its year end balance of funds to non-pro ts. e MHSHOF has worked out a process of displaying inductee sports memorabilia at the Mount Holly Historical Society for the bene t of the community.

The Mount Holly Sports Hall of Fame Salutes the following Athletes of the Year.

Stuart Cramer Highschool

Drew Croft’s • Madison Lee

Athletic Director: Brad Sloan

Mount Holly Middle School

Leonard Wright • Elise Taylor

Athletic Director: Courtney Radford Wellman

East Gaston High School Selection did not come in before print date

Vance Furr

SBI Agent Vance Furr’s ticket to happiness was helping youth of Mount Holly

This journey begins, innocent, in the backseat of a patrol car.

Vance Furr, a school teacher and ball coach in Cabarrus County in the early 1970s, attended a community law enforcement get-together, where he took an interest in the fancy, spiffed-up police vehicles. A nice officer showed him a car’s interior, and took him for a little ride.

“And then, they began to chase criminals, and the car sped up, and the sirens came on and he thought, ‘Man, I got to get into this,’ so he went to the SBI.” DeLina Furr remembers the day that instigated her future husband’s 30-year career with the North Carolina State Bureau of Investigation.

DeLina, a teacher, met Mr. Furr at Mount Holly Junior High in 1976. “He came to give a drug talk,” she says. “And at that time, quaaludes and marijuana were the big drugs, and my family knew the chief of police, and Vance asked a policeman who I was. We dated a few times, and I thought that was it, that I’d never see him again. We met again at a church retreat, and committed to marriage.”

They wed in 1980.

Their 31-year love story, before Mr. Furr’s death in November 2011, chronicles a man devoted to his faith, his wife, his SBI and law careers and, entwined with all that, his devotion to the children and youth of Mount Holly. It’s that volunteer work – his ceaseless involvement with the Mount Holly Optimist Club, the town’s Field of Dreams project, the athletic building at Tuckaseege Park and a multitude of youth activities – that makes Mr. Furr the 2024 recipient of the Mount Holly Sports Hall of Fame Community Spirit Award.

“Vance was a pretty lively fellow, and he got several awards throughout his life, but I think he would enjoy this the most,” his wife says, “because he loved the youth of Mount Holly and he wanted to work for his community. I’m sure if he were here to accept it, he’d have something witty to say. He might also have a tear or two, because this would mean so much. He got the Order of the Long Leaf Pine, some coaching awards and some from the SBI, but he would say this means the most. He would be witty, but there would be a sincere part.”

Mr. Furr wasn’t always known for sincerity.

“One of the things that attracted me to Vance was the twinkle in his eye,” DeLina says, “especially when he was up to mischief.”

She recalls the day a teenager rang their doorbell and asked for her car keys. “There was one of my students, and he said, ‘Mrs. Furr, we’ve come for your key.’ My key? ‘To your car,’ the teen said. ‘Vance said we could use your car to go to the prom.’”

He got the key.

Mr. Furr’s calling to serve the town of Mount Holly’s children took some getting used to.

“Sometimes he worked undercover with the SBI, but sometimes he didn’t,” DeLina says of their early years. “He’d work long hours, and mostly he’d work drugs and the drug deals took place at night. In fact, I never learned to cook. When we got married, everybody gave me cookbooks, and I tried but Vance would never show up for supper, so I told him, ‘You’ll have to get food where you can.’ So he got stuff out, and sometimes he’d bring stuff home.”

She knew, from the onset, he would be

busy weekdays and weeknights.

Weekends, she assumed, would be reserved for her-plushim.

Then she heard about the children. “I knew when we got married, if we needed anything done around the house, it would have to be weekends,” she says. “And weekends came, and he was never home. My honeydos were not getting done. And I kept nagging him and nagging him.”

One day, they had a heartfelt discussion. As was the way in their household, they called each other by last names, him using her maiden name.

Mr. Furr explained he was at the Optimist Club weekends, or coaching youth leagues, or mentoring children who needed someone to listen. He was a big man – 6-foot-7 and well north of 200 pounds – but he was a gentle friend, with the kids.

“He called me Greene, and I called him Furr, and he’d say, ‘Greene, I see so many things in my line of work, and this is the only place I have to see good things. I see good things in children.’

“And after that, I never bothered him again. He’d go on Saturdays, and from that point on, I understood.”

The honey-dos could wait.

“It was like having two jobs,” DeLina says. “You work with criminals, and you work with youth. And he loved both. I couldn’t keep up with Vance. By Friday (after a week of teaching), I was dead tired and spent the weekend trying to reconstitute myself. And he had so much energy.”

The Optimists concocted a haunted house each Halloween. Scott Pope, president of the Mount Holly Sports Hall of Fame and 2019 recipient of the Community Spirit Award, remembers Mr. Furr’s contribution. “He was a big guy, and we’d make about $5,000 or $6,000 a year on the haunted house, but he’d dress up like (“Friday the 13th” movie character) Jason,” Pope says, “and walk through the parking lot, and he’d scare them before they got in. And I’d tell him, ‘Vance, let them get inside. Then scare them.’ He was a big guy with a kid’s heart, one of those people who stands out and has a deep voice, but he was a gentle giant.”

“To me,” DeLina says, “he was a handsome guy. He was so interesting. And faith meant a lot to him; he was a real Christian. He could come across as gruff sometimes, but he had a heart of gold. He was a really good man.”

Mr. Furr graduated from the University of North Carolina and was a fan of Tar Heel basketball and football. He was a member of Tuckaseege Baptist Church. After retirement from the SBI, he formed Vance Furr Private Investigations. He played softball with the Mount Holly Police Department. Then came lymphoma.

He fought it 16 years before it spread throughout his body. For a while, he was in a medical facility. “Then I brought him home and kept him home for three months,” DeLina says. “It was a choice of going to a home or being in our home.”

Mr. Furr passed away on November 19, 2011. He was 66.

“I called him my Renaissance Man because he had so many interests. He looked on the bright side of everything, and the one thing he taught me is forgiveness,” DeLina says. “He would always forgive and forget and want to be friends again. He really believed in that.” ■

— By Kathy Blake

For: Extensive contributions and devotion to Mount Holly children and youth programs including the Optimist Club, Field of Dreams, Tuckaseege Park, coaching youth sports and having the intangible role of mentor and friend.

James Mack excelled regardless of obstacles

James Mack tells stories about football the way the game used to be, seven decades ago, long before high school stadiums were built of steel and aluminum and synthetic turf and lit bright as a Friday night Christmas.

He tells about kids playing pick-up, in neighborhoods that belonged to only them, in the 1950s, before desegregation changed things.

He tells about being a little guy, about 119 pounds, and suiting up to play for Reid High School in Belmont, where Black children from Mount Holly, Lowell, Cramerton, McAdenville, Neely’s Grove and south Gastonia attended before the school closed in 1966, and its buildings were demolished.

Mack was in the Class of 1961.

“High school games were a lot different. We practiced on a red clay field, and when it rained it was just like practicing on

Mack became a three-year starter at Reid High, at defensive back as a sophomore and halfback-defensive back as a junior and senior. He played baseball three years, as a relief pitcher and outfielder.

cement,” he says. “We played games at the old Belmont Park, and it was half baseball field and half grass. They marked it off in some kind of way, but there was a lot of infield dirt. It’s a lot different now. They got real fields they can play on.”

Mack was born in 1943.

He tells stories about his uncles playing football, including one who got a full ride to Florida A&M.

Mack became a three-year starter at Reid High, at defensive back as a sophomore and halfback-defensive back as a junior and senior. He played baseball three years, as a relief pitcher and outfielder. Colleges, including Elizabeth City State Teachers College in Pasquotank County (now Elizabeth City State University), noticed his football ability, but Mack didn’t sign. “I thought I was too small,” he says.

So he got bigger – up to 165 pounds – and played some semi-pro, with the Gaston Patriots alongside defensive linemen listed as 6-foot-7, 330, double his weight, and 6-foot-7, 275.

The thing about James Mack, a 2024 inductee in the Mount Holly Sports Hall of Fame, is his determination to play the game of football while trying to not be hindered by a physical impairment.

When he was 14, Mack was caddying a golf match in Mount Holly when a ball hit his eye. “I was caddying for a group of players, and I was out in front and one of the guys sliced it,” he says. “I had an operation and they patched it, but I went back the day after Thanksgiving because they missed a spot and they had to take it out. I had already got hit in that same eye with a rock, so I couldn’t see too good out of it.”

Mack finished high school ball with one eye. He played Patriots ball two years, and succeeded.

“It was a little hard at the beginning. I had to learn to judge with one eye, and I was 14 years old at the time, but you learn

to live with it,” he says. “I loved the sport of football.”

In semi-pro, he and a friend tried out. “They found out they (other players) couldn’t hit no harder than I could hit, so the first year I was a kickoff and punt receiver, second team,” he says. “Then I was a linebacker, and we played our first game in Marietta, Georgia, and they played me because I loved to hit.”

Those two 6-7 linemen went on to tryouts with the Colts and Redskins.

“We had some pretty good talent there,” Mack says. “We had another running back drafted in the fifth round by the Falcons and a wide receiver who was contacted by the Dallas Cowboys. I never did make weight, so semi-pro was about as far as I could go. We played about two years and it ended. We was promised money, and that never did happen, so after two years, they just sold it. We got a lot of promising, but if it’s something you love to play, you just do it.”

He later played seven years of softball, with Skidmore Construction Company and Burlington Industries, playing outfield in their open leagues.

He laughs when telling stories about that game being rougher than football.

“I got more hurt in softball,” he says. “I pulled a hamstring all to pieces, tore a rotator cuff, broke elbows. When you play all out, in a construction league, you play all out.”

“If your heart is in it, you should give it a try. If you love a sport, go out and show them what you can do.”

Mack moved to Atlanta for several years, then back to Charlotte in 1995. He enjoyed Falcons games, and Panthers games when the NFL newcomers played in Spartanburg. He worked in textiles and for Frito Lay, then started his own janitorial business when he moved back to Mecklenburg County.

The family returned to Mount Holly in 1997. “I went back into the school system as head custodian,” he says, “and worked for Ida Rankin (Elementary).”

He and his wife, Gloria, had two sons, Andre and Lamont, and a daughter, Lashaunda. They lost Andre in December 2022 to a heart attack. “He was a good athlete, with scholarships for football and baseball, and he tried out with the Red Sox,” Mack says. “They had about 250 guys trying out down in Florida and he was one of 10 they kept over for an extra day. He played football, too, in high school and had offers in both sports.”

The Hall of Fame induction, Mack says, “kind of surprised me. There are some good athletes here in Mount Holly, and it’s good to be selected.”

He tells a short story, directed to athletes of today. They may play on cement-hard clay, or a field of soft, green grass. It doesn’t matter. “If your heart is in it, you should give it a try. If you love a sport, go out and show them what you can do.” ■

— By Kathy Blake

Football: Three-year starter for Reid High School; defensive back and halfback. Started eight games for semi-pro Gaston Patriots. Recruited by Livingstone College and Elizabeth City State Teachers College.

Baseball: Co-captain, Reid High School team.

Softball: Played seven years, Skidmore Construction Company and Burlington Industries.

Bullseye

Lee Edison Hansel reached life’s targets on his own terms

Archery, from the Latin word arcus, meaning bow, has been used for hunting and combat dating to 10,000 BC.

In the United States, the National Archery Association was created in 1879; archery has been an Olympic sport since 1972.

Lee Edison Hansel, Jr., of Mount Holly and, later, Charlotte, competed for the Gaston Archers Club and won the National Archery Association Intermediate Boys national championships at age 16, in 1962, and the Boys 15-18 age group National Archery Tournament in Oakbrook Park, Ill. He was second in the State Indoor Championships in Winston-Salem in 1963 and won the Southern Archery Association championship in a twoday tournament in Stone Mountain, Ga., in 1965.

His success in the sport makes Mr. Hansel, who passed away last October at age 78, a 2024 inductee in the Mount Holly Sports Hall of Fame.

He is the Hall’s only member to have won an individual national championship.

“Ed was brilliant,” says Eddie Wilson, secretary of the Hall of Fame, who remembers Mr. Hansel from childhood.

“He was voted Most Likely to Succeed in his class,” says Patsy Hansel, his sister. “He was the smartest one. When you grow up with someone, you don’t think of them as brilliant; they’re just your brother. He was certainly good at whatever he did.”

“Ed became a national champion and earned the highest award in Scouting, and set an excellent example for all with whom he came in contact,” says Patsy’s longtime friend Caroline Bailey. “He accomplished more in that brief time than many do in a lifetime. Everything he attempted in high school and as a young man, he was successful.”

Archery wasn’t prominent in high schools or college. Mr. Hansel learned through the Gaston club and Boy Scouts, known for their pursuit of developing life skills such as selfconfidence, leadership, wilderness survival and personal responsibility.

“He would go into the forest and shoot at targets, and Daddy bought some and they set them up,” Patsy says. “They had tournaments in different parts of the state, and when he won the (national championship) finals, he won that in New York.”

The “Working Scholars Archery Study Guide” describes the sport’s requirements and techniques: First: Proper stance. Line up, so your feet are in a line toward the middle of the target.

Mr. Hansel stood ready to excel. He became an Eagle Scout at age 13. The 1963 Mount Holly High School yearbook has a list under his name: Graduated with honors; archery wiz; president of band; outdoorsman; bound to succeed; Beta Club; Junior Heart Board; French club; bus driver; Most Likely to Succeed and Most Talented.

“He had an introverted personality, and he was in tune with nature,” Wilson says. “He was so gifted.”

“He was certainly good at whatever he did,” Patsy says. “He played clarinet in the band, and with archery he became the best he could be.”

Second: Put the arrow in the bow, on the arrow rest, which is part of the bow.

Mr. Hansel, set for the next step, enrolled at UNC-Charlotte. He graduated with a degree in mechanical engineering and found work in his field. But something, family members noted, began to interfere with the gears and equipment. Something in the alignment wasn’t pinpointing the target.

Third: Grip the string. Typically, three fingers are used to hold the string.

Sometime after college, Mr. Hansel’s grasp on things changed. He said he wanted to “live outside.” He said he didn’t want to be a burden to anyone and wouldn’t accept handouts. Something interrupted his aim. “He had some kind of mental problem,” Patsy says. “When he first got sick, he had a psychiatrist he really liked, and that psychiatrist told him he should go to Rome someday.”

Fourth: Draw the bow.

Mr. Hansel took his energy, his outdoorsman skills and his fondness for nature and pulled them together, tight, ready to spring him in a new direction.

He set out toward Charlotte.

He spent 50 years on the streets.

“He was very polite and had a lot of friends around town,” Patsy says. “He was a very strong person. People knew he did not drink or do drugs.”

He settled into a comfort place, a covered alcove near St. Peter’s Episcopal Church, where he became the unofficial custodian, picking up trash and yard debris around the church campus. To St. Peter’s members, law officers and business people who commuted along 7th Street and North Tryon in Charlotte’s Fourth Ward, Mr. Hansel was known as the “Good One,” and “Dean of the Streets.”

His siblings visited and “tried to take care of him,” Bailey says. He was the inspiration for Roof Above, an interfaith non-profit formed from the merger of Charlotte’s Urban Ministry Center and Men’s Shelter, to help people on the streets and “end homelessness, one life at a time.”

Fifth: Aim.

One day, Liz Classen-Kelly, CEO of Roof Above, saw Mr. Hansel walking rapidly along the sidewalk, his aim set on something. Focused.

She later told Roof Above supporters: “Boy did he walk … He walked up and down South Boulevard. All through Uptown. If you wanted to talk to him, you had to be prepared to walk with him, and don’t be fooled by his age, he could walk fast. I recall pulling over one day when I saw him walking in South

Charlotte. He let me know he was headed to Rome.”

Rome, Georgia, she asked?

No, he said. Rome, Italy.

Classen-Kelly said she smiled politely, “not believing him for one moment.”

“We found out,” Patsy says of the 2012 event, “when they called from the Embassy, that he was in Rome, Italy. He had a return ticket and somebody took it. But he was provided with a ticket back. He stayed in Rome about a month. We asked him how hard it was to get a passport and he said Roof Above helped him. He talked about going back.”

Sixth: Release.

Mr. Hansel stopped “living outside” in March 2022. He was violently assaulted, his sister says, in his haven behind St. Peter’s. “I don’t know what the people who beat him up thought they’d get,” she says. “He was in a hospital, then in rehab. He died in there, a year and a half later.”

Mr. Hansel – who went by both Ed and Lee, depending –could aim for a target 230 feet away, or a country 4,800 miles across the sea, and hit each smack in the center.

“My father once said that Ed was very independent and didn’t want to be beholden to anybody,” Patsy says. “And some people said, you can’t be any more independent than living on the streets. The other way of looking at it is, you’re completely dependent.”

Roof Above offered Mr. Hansel a bed in its shelter. Except for nights of unbearable cold, he declined.

“I am grateful,” Classen-Kelly said in her speech to Roof Above supporters, “to have known this remarkable survivor who lived life on his own terms.”

A “Charlotte Ledger” newsletter, ‘Ways of Life,’ on November 21, 2023, stated: “One more thing. Lee’s family was and forever will be sad. But they understand. They agree that Lee was at peace. It wasn’t so much a question of ‘Was he happy?’ as it was a question of ‘Did he live life his way?’ The answer is yes.” ■

— By Kathy Blake

Archery

• 1962: National Archery Association Intermediate Boys national champion.

• 1962: Boys 15-18 Age Group National Tournament champion

• 1963: State Indoor Championships, second place

• 1965: Southern Archery Association champion.

Base Paths

Jamie Summerlin’s baseball skills took him from playing to coaching, and catching a few summer days with the pros

As a little kid, Jamie Summerlin threw baseballs at the walls of his house. And his grandparents’ house.

He’d watch baseball on television, then go outside and transform himself into a 5-year-old Major League superstar pitcher, determined to not break a window.

“We’d also play Wiffle ball, my brother and the kids in the neighborhood,” he says, “pretty much all day long in the summers.”

His television – this was the 1980s – got 12 channels. “We had the old dial TV, where there were only 12 dial numbers on the set and TBS just happened to be Channel 12, so that was the station for the Atlanta Braves,” he says. “So I grew up with a bad team, other than them having Dale Murphy. I’d get the newspaper and look in the sports section to see who was playing well in the majors, and we’d go outside and have fantasy leagues. We thought we were the players. If they batted a certain way, we’d try to do it their way.”

Summerlin took that childhood desire and transitioned it into successful years in youth ball, junior high and high school

teams, college and coaching. For his list of accomplishments, he is a 2024 inductee in the Mount Holly Sports Hall of Fame.

“When I was told (about the Hall), it was kind of a surprise. I don’t really feel worthy, to be honest,” he says. “I’m just honored and humbled to be chosen. I have a close personal friend who was inducted a few years ago (basketball player Stewart Hare in 2022), so it’s an honor to be in there with him. And my wife’s grandfather (Bob Black) was inducted in the first class.”

Summerlin’s intro to organized ball was a Stanley 10-under Dixie Youth team that, when he was10, finished as state runners-up. “We were one of the first teams in Stanley to accomplish that,” he says.

He alternated playing first- and third base, and in seventh grade switched to catcher. “I’d never caught before, and the coach told the team, ‘Hey, we need a catcher,’ and I’d never caught but I thought it would be a way to get on the field,” he says. “It was rough for a while, getting used to it, and it wasn’t a whole lot of fun getting beat around, but it was a way to be on the field. Slowly but surely, by ninth grade, I had it down.”

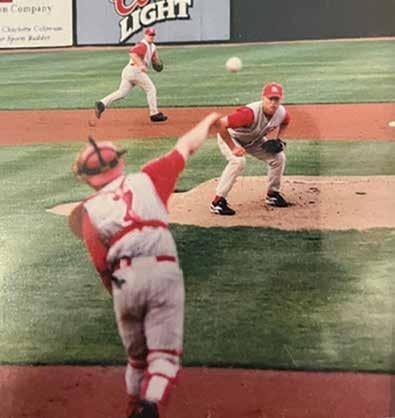

Summerlin started at catcher three years for Stanley Junior High, then three years at East Gaston High School, where he was senior captain in 1998 when EG was MEGA 7 4A co-champion.

“Looking back, one thing I laugh about is how times have changed. Back then, we would always take the school’s 15-passenger van to away games,” he says, “and I was considered one of the more responsible guys so I would drive one of the vans, with all the players in it. It just amazes me –that would never happen today. I can’t believe I was a senior on the team and responsible for 15 other lives.”

High school summers meant American Legion ball, and Summerlin played for the Gaston Braves. He was recruited by Belmont Abbey College and a handful, he says, of smaller schools but chose to stay local.

“Fun fact is, it was an interesting transition having grown up as a Southern Baptist kid in a Southern Baptist church, and here I go off to a Catholic college with a monastery,” he says. “It opened my eyes up to a lot of new things.”

Belmont Abbey, at the time, was not a baseball powerhouse. “They were kind of a bottom-dweller,” Summerlin says. He was starting catcher his freshman season, and “we won, like, 15 games. Sophomore year, we won, like, 19. And my junior year, we won the conference and made NCAA Regionals for the first time in school history. So, we went from worst to first and won over 40 games. My senior year, I was co-captain and we were Conference Carolinas champs. I was proud to be on the teams that turned the program around.”

That senior season, the Abbey hired an assistant coach named Kermit Smith, who became the Crusaders’ head coach

the following year at age 23.

“He took over, and he was, like, 22, 23 so he was a year older than the senior class,” Summerlin says. “We actually played against him (versus Pfeiffer University) in years prior. So, we learned together and I ended up coaching with Kermit for about eight years after that with the summer Legion team, the Gaston Braves, so I saw him come through the ranks and now he’s at App.”

Smith became head coach at Appalachian State University in 2017.

Summerlin spent some of his college summer days in Fort Mill, S.C., as a warm-up catcher with the Charlotte Knights. “It was a wonderful experience, because I got to go on the field and hang out with the players, kind of live the life, and warm up some of the guys,” he says. “It put money in my pocket but also helped me develop my skills, because I was catching pitchers who were really, really good.”

He also has worked with Gaston Christian’s team and for the last three years has been an assistant coach to Devon Lowery, formerly with the Kansas City Royals.

Summerlin works for a financial services firm that specializes in retirement plans and finances for ministry-based organizations and is part of the Southern Baptist Convention. He and his wife, Anna, have three children – Cooper, 17; Sadie, 13; and Maggie May, 7.

Cooper plays baseball. He’s a left-handed pitcher/ outfielder who is being looked at by a few colleges.

Cooper once played 10-under ball, like his father. “I did some Stanley rec coaching,” Summerlin says, “and it kind of

came full circle. When I was 10, we lost in the championship game. When my son was 10, he played for the same recreation department, and I was head coach and we won the state championship. It was a neat little moment.” ■

— By Kathy Blake

Baseball:

• Stanley Junior High – 3-year starting catcher. Gaston County conference runner-up, 1994.

• East Gaston High – 3-year starting catcher. Senior captain, 1998. MEGA 7 4A champions 1996 and co-champions 1998. Defense award, 1998.

• American Legion – played / coached 12 years. Won Don Dycus Award, 1998.

• Belmont Abbey College -- Starting catcher, freshman year. Co-starter, sophomore-senior. Senior year team captain. Academic All-American. Academic All-American. Carolinas Virginia Athletic Conference all-conference, four years.

Basketball:

• East Gaston High School – 2-year starting point guard.

Coaching:

• Gaston Braves American Legion team – Assisted Appalachian State Univ. head coach Kermit Smith and Belmont Abbey head coach Chris Anderson.

• Stanley 10-under baseball – Head coach, won 2017 state championship; finished 3rd nationally.

• Stanley 12-under baseball – State championship runners-up (year?)

• Overall – coached more than 60 college signees/ professional draft picks.

Other:

• Graduated from Belmont Abbey 2002, Bachelor’s in Finance. Board member, North Carolina Council of Economic Education. Served on Mount Holly Recreation Commission, three years. Married to Anna Black Summerlin. Three children – Cooper, 17, Sadie 13, Maggie May 7.

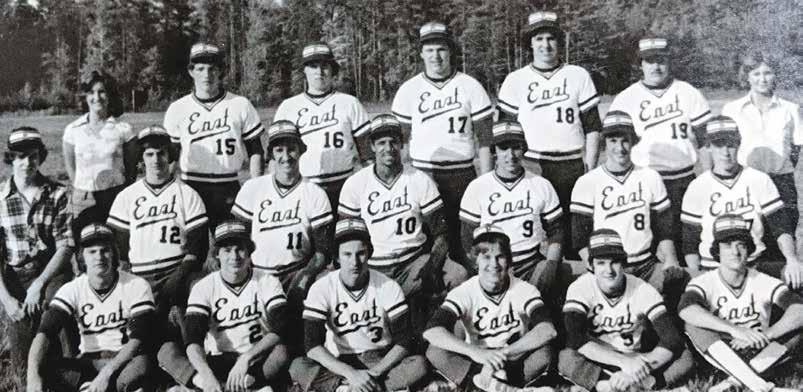

The history-making season of East Gaston’s bat pack gang of ’79

It was 1979, a year lodged between “Saturday Night Fever” and the Reagan administration.

SONY invented the Walkman that year, McDonald’s introduced the Happy Meal, the 205th and final episode of “All in the Family” was broadcast on CBS, and in Cleveland, Bobby Bonds hit his 300th home run, making him the second player to have 300 homers and 300 stolen bases.

In Mount Holly, East Gaston High School’s baseball team, a family-like gang of teenagers, was making news headlines on its own field – a literal diamond in the very-rough remembered, kindly, as a natural habitat with tall grass, uneven terrain and maybe a water hazard or two.

“If you put a fence and two benches out in the middle of a pasture, that was our baseball field,” says outfielder Tracy Black. “We used to crack ourselves up because opposing teams would show up to play on our field and we would hear, ‘You’ve got to be kidding me.’ We did have some home games in ’79 though.”

“Where the field sits now, home plate would have been way off in right field,” says pitcher Wayne Kinley. “It was a cow pasture.”

“Pasture might be too kind of a word for it,” says

centerfielder Kevin Collier. “I mean, we had no outfield fence; somebody put up two poles and a fence for a backstop and scraped off some grass to put bases down. We had some rubber for home plate, and we played baseball out there.”

East Gaston’s boys of spring also were the Warriors’ boys of fall, and winter.

“The core of that team did a lot of winning in all areas, baseball, basketball and football,” Kinley says. “Coach (Jerry) Adams was the duo coach.”

“The football coach was coaching the baseball team, so of course we went to the state championship,” says third baseman Shawn Devinney.

“We went because of a bad hop in the outfield,” Collier says. “We advanced to the playoffs because our field was so uneven, there was a bad hop and it let us clear the bases and win the game. The other team was furious.”

“It was good,” Kinley says, “but it was 100 years ago.”

This year, the 1979 team joins the Mount Holly Sports Hall of Fame. Its success in advancing to the school’s only state championship season became an inspiration for the EG program.

In 1979, Darrell Van Dyke was a first-year teacher and assistant baseball coach. The school’s current baseball field is named for him.

East Gaston took an 18-5 record, one published story says, into the 1979 State Championship series after beating T.C. Roberson 7-3 in Fairview in the second round of the state 3A

playoffs and defeating South Stokes 6-2 in Belmont to win the Northwest 3A Conference championship The team advanced to the North Carolina 3A State Finals to play the winner of the White Oak-South Johnston game.

They played White Oak, of Jacksonville, at its field.

White Oak’s pitcher was Louie Meadows, who played at N.C. State and was a Houston Astros second-round pick. His high school record was 28-0.

“We did not win,” Black says.

But they put up a good fight.

“There was a skirmish. Call it that,” Collier says. “Shawn, our third baseman… the runner was coming back at him, and Shawn lowered his shoulder to keep from getting run over, and lifted the guy up and the benches came out and we had a little skirmish. Shawn lowered his shoulder like a football player, and most of us did play football together.”

“Of course,” Devinney says, “a couple of us got thrown out. I got wound up and got into it with another guy, and their coach came out, and when they started comin’, Coach Adams was like my daddy out there, telling about it. So we both finished the game outside the fence.”

White Oak aside, the guys already were winners.

“The ’79 class was actually the same group of guys who won the county championship when we were in junior high at Mount Holly Middle,” Black says. “So we won that, then it took us three years to win another conference championship when we were seniors.”

The sophomore class, Class of ‘81, Collier says, already had won four state championships together at some level: “I heard Coach Adams joke one time to another coach, ‘I just roll the balls out there and make the line-up and get out of the way.’ That’s what made it fun. He let us enjoy the game and play.”

The gang played American Legion ball together in Belmont. Mick Mixon, whose first radio job was at WCHL in Belmont and who later became the Carolina Panthers play-by-play announcer, called the games.

“He was in high school over there in Belmont, and we thought he was a nerd and wouldn’t give him the time of day,” Collier says, jokingly. “And he traveled with us to our games. I remember when (teammate) Derek Spears was playing at Clemson, he gave him an interview. It’s funny – we played Legion with the Belmont guys, who were our rivalry, and (South Point High School coach) Phil Tate was our coach, and he started more of the East Gaston guys than his own guys, even after they won the state championship.”

“East Gaston was one of the best teams I’ve ever played on. There were a lot of incredible players on our team,” Kinley says. “We, as sophomores, were really fortunate to have those seniors. It meshed really well.”

A few after-graduation stories:

Tracy Black: Played Class A ball with the Twins

organization in Visalia, California. “It was in the middle of the state, hot as heck, 40 miles from Bakersfield. We were nowhere near water. I worked hard to get out of there. Then, I played AA in Orlando. It was still the middle of the state, but it was better than the desert.” Black was switched from outfield to first base, where he had a career-ending injury. “I gave myself a five-year plan to make the majors, and I was going on three years at the time. I was married and had a son back here (N.C.), and I would have had to go down two levels and work my way back. As much as I loved it, I had a responsibility.”

Today, Black lives in Fletcher, near Asheville, and works for Wilsonart, a specialty shop for designer laminate counter tops. He and his wife, Jill, have a blended family with seven children.

On his induction to the Hall: “We were just a bunch of guys who grew up together and played baseball and loved it and had success at the end. Even though it wasn’t the exact success we went for, we still did pretty good.”

Wayne Kinley: Drafted out of high school in the 17th round by the Seattle Mariners in 1981. “I went to Bellingham, Washington, just outside of Seattle, at 18 years old with $20 in my pocket, on an airplane and I’d never flown before, and was 3,000 miles away from home. Then I went to AA, and it was called the Wausau Timbers (in Wisconsin), in the Midwest League. Our second-baseman was a guy named Harold Reynolds, who’s the broadcaster on ‘Baseball Tonight.’ I eventually was released because of shoulder issues, rotator cuff.” Kinley went to work in the soft drink business, traveled the country and now lives in Calabash with his wife of 37 years, Debbie, and their son, Austin.

Kevin Collier : Played for UNC-Charlotte. He took a job in sales for a glass company, was on the Gaston County Board of Education for 24 years and now is sole owner of Riverside Millwork in Charlotte, which specializes in handcrafted doors and windows. He and his wife Mary have two daughters and a son.

Derek Spears: Shortstop, second base. Three-sport athlete: baseball, football, track. Played for Clemson. He was Class of 1981 at East Gaston and was quarterback for the football team when it won its first conference title. ■

— By Kathy Blake

State championship runners-up

Players: Derek Spears, Doug Criswell, Kevin Collier, Todd Kitchen, Jackie Lewis, Tracy Black, Wayne Kinley, Shawn Devinney, Chuck McGee, Scott Brannon, Vance Cleveland, Joey Huffstetler, Phil Jonas, Robert Kaylor, Steve Perkins and James Rhyne.

Chais Schenck watched, learned and practiced, then won the best wrestling match of his career

It was the last match of Chais Schenck’s senior year, the finals of the 2000 4A State Championships.

Across the mat from the East Gaston wrestler stood Brandon Palmer of Riverside High in Durham.

The two had met five times during the previous three years. Each time, Palmer won by one point.

One tiny point.

“And at the end, this last match, I thought, ‘I can not beat this!’” Schenck says of the streak.

“But my parents and my coach believed in me, and in that last match I beat him by three points. I still carry that with me to this day. I can overcome, and that taught me a lot. Keep believing.”

Schenck wrestled at 112 pounds his senior year and at 103 as a junior when he was 4A State runner-up. He was a threetime conference and regional champion and finished his East Gaston career with that state title and 139-20 overall record.

His success has landed him in the Mount Holly Sports Hall of Fame.

“Honestly, it’s an honor,” he says. “It was a surprise to get that call (from the committee), but at the same time it’s

“Honestly, it’s an honor. It was a surprise to get that call (from the committee), but at the same time it’s amazing to be recognized. That’s not why I was wrestling, to get into the Hall, but it’s great to know I had that impact in that short a time frame.”

amazing to be recognized. That’s not why I was wrestling, to get into the Hall, but it’s great to know I had that impact in that short a time frame.”

Schenck learned how to wrestle by watching, studying, reviewing moves in his mind. “You hear about football players watching film, and I was essentially watching film without realizing it,” he says.

His older brother, Tius, wrestled for Stanley Junior High, coached by Randall Fortenberry. “And my brother allowed me

to start going to practice, so I started learning from watching him when I was in fifth grade,” Schenck says. “I fell in love with it, and watching my brother and Coach Randall gave me the work ethic I had.

“My dad wrestled in high school, so that’s how we found out about the sport. My brother is five years older than me, and he came home after learning wrestling moves and practiced them on me.”

Who needs mats when you have a living room floor? “It was fun. Looking back at it now, a lot of my accomplishments were because of my brother and Coach Randall. I’d also watch my brother’s teammates and study and learn the whole time.”

While wrestling is an individual sport, because of weight classes, it’s also very much the union of a team, and that camaraderie and bond motivated Schenck through high school.

“Winning conference tournaments and regionals, that was always a big deal. Even though I won or placed at States, any time the team accomplished great things, that was good,” he says. “Sophomore year we had the state record for pins. Things like that involve the whole team, and that meant a lot to me. To this day, I consider all of them family. If they called me today, I’d be there tomorrow if I could.

“I want to thank my parents, Earnest and Judy, and Coach

Randall Fortenberry and all my high school coaches and all my teammates,” he says. “Even when I won State, I felt like I was winning for everyone.”

“All the practices, all the traveling, seeing each other outside of school, us pushing each other to be the best we could be… it’s really a family.”

Schenck didn’t pursue wrestling after high school. He lives in Greensboro now, with his wife Courteney and 12-year-old daughter, Zoe. He works for Apple and plays drums in a band, or wherever his music is needed. In June, he traveled to New York City to play two shows with singer Maia Kamil, at The Bowery Electric nightspot near Lower Manhattan then across the Hudson in Montclair, New Jersey.

“I’ve always been a musician, and in chorus,” he says, “so I

still play.”

Schenck turned 42 in July. He doesn’t wrestle anymore, not even on the floor. After high school, he says, “I told myself I was finished.”

He has people to thank for those high school victories, the teamwork and the friendships.

“I want to thank my parents, Earnest and Judy, and Coach Randall Fortenberry and all my high school coaches and all my teammates,” he says. “Even when I won State, I felt like I was winning for everyone.” ■

— By Kathy Blake

East Gaston High School (head coach Scott Goins): 4A State Champion at 112 pounds, 2000; State runner-up, 103 pounds, 1999. Three-time conference and regional champion.

Do the Math

Basketball’s Cierra Brooks put up the stats, collected the awards

Before she ever stepped into a uniform, before any sideline stats-keeper with a folding chair and No. 2 pencil scribbled her progress, Cierra Brooks’ basketball numbers told her story.

She was 7; the backyard goal was 10 feet. Two of her brothers, William and Christopher, weren’t lowering it for a girl. “That’s the earliest I can remember playing,” she says. “We had a 10-foot goal, and I was always better than my brothers. I was always outdoors. As long as I was allowed to be outside, I was always playing.”

When she took her game inside, at Mount Holly Middle School, the 5-foot-7 guard added AAU ball with the Mount Holly Stars, until her senior year when she played for a team in Hickory.

Two AAU teams equals more game time.

“With AAU, we traveled a lot throughout the weekends, like multiple games on Fridays, Saturdays and Sundays,” she says, “and you play three or four games in one day.”

It wasn’t tiring. “It was more like, this is my everyday life. This is what I do,” she says. “That’s what happens when you truly love the game of basketball. During that time, I always

thought it was fun. It didn’t become a job until I got to college.”

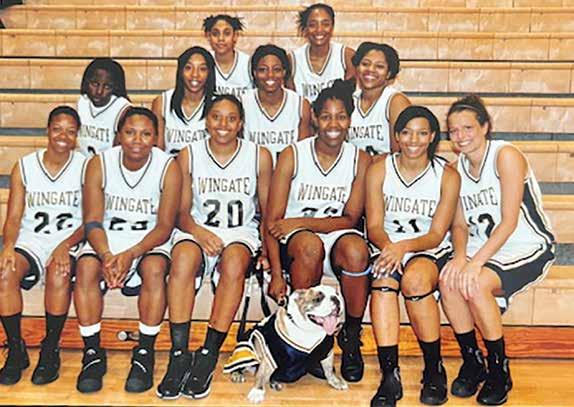

Brooks’ exemplary play at East Gaston High School and Wingate University has placed her in the Mount Holly Sports Hall of Fame.

Even her induction has numbers attached.

Her 2024 induction is the Hall committee’s second attempt. “When it was first presented to me, Tyler Berg asked me about it last year, and I declined the offer,” she says. “Then this year, I guess he talked to (East Gaston’s) Coach Bridges, and he called me and said, ‘Now, C, somebody is going to be calling you, and the answer needs to be yes.’ And I said, ‘Yes, sir,’ because how was I going to tell him no?”

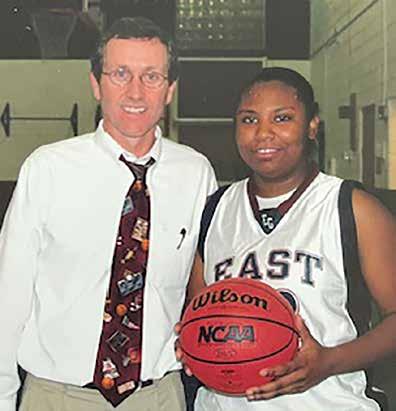

Ernie Bridges coached Brooks at East Gaston from 2003 through 2007, but his impact on her life started earlier.

“The first time I met him I went for a summer camp, the summer between eighth and ninth grades. East Gaston had a camp, and I got introduced to him and he asked me a question and I answered ‘Yes,’ and he said, ‘That’s going to be yes, sir.’ He continued to give me structure and discipline,” she says. “I honestly don’t think I would have made it without him.”

There are a number of reasons.

He gave her game a meaning, when it needed one. And he helped Cierra Brooks – nicknamed CC – the person, as well as the athlete.

“When I was around 14 ½, right before I went to high school, my dad got sentenced to prison for eight-and-a-half years, so he didn’t see any of my high school or college games,” she says. “It was me and my mom. And when I was 16, my mom suddenly passed away. It was something we weren’t expecting; we didn’t know she was sick like that. So I was raised by my brothers. I was grateful to have Coach Bridges, because he kept me motivated and he really took me under his wing. I’m forever grateful to him, and to Kim Sealey, one of my teammates’ (Cameron Sealey) mom. She helped look out for me.”

Bridges helped Brooks, the athlete, start putting up numbers on the basketball court.

She won the team’s rebounding award, its Most Versatile award,

was an MVP and co-MVP. She was three-time All-Gaston Gazette, two-time All-Gaston Observer and three-time AllConference.

By the end of high school, she had 1,332 points, 490 rebounds, 298 steals and 250 assists.

One night in 2006, Bridges stopped a game during play to honor Brooks with scoring her 1,000th point.

“They stopped the game and wrote on the ball and gave it to me,” she says. “They blew the whistle and stopped it. I still have that ball. It was special, and Coach Bridges helped me understand that, but he knew I was one of those players who didn’t care so much about points, I just wanted to win more than anything.”

Brooks went on to play for Wingate University, where she continued to put up impressive stats:

She appeared in 33 games as a freshman in 2007-2008, scored in double figures nine times and had 15 points against Augusta State in the Sweet Sixteen. She was third on the Wingate charts the next year at 9.2 points per game and second with 47 steals. In 2009-2010, she started six games and scored in double figures in each.

“That was the one college that I visited, and Coach (Barbara) Nelson and I just clicked,” Brooks says. “Not having my mom around and not having that guidance, that was the place I needed to be. And it wasn’t that far from home.”

When Brooks graduated from East Gaston, at the ceremony in which Bridges awarded her the co-MVP award, his speech had a number of compliments:

“She has the complete package with her running, jumping,

shooting, passing and ball-handling skills…”

“She has some of the most extraordinary God-given gifts that I’ve ever witnessed while at East Gaston…”

“I believe the future is bright for her as she takes her game to the next level in college …”

After Wingate, Brooks worked for a group home for special needs adults, then for the Mecklenburg County Sheriff’s Office. She’s now an officer with the Gastonia Police Department.

No need for big numbers these days – she’s single, a household of one.

“I like to travel,” she says. “I can just pick up and go.”

Of this second time around with the Hall of Fame, she says, “It’s most definitely an honor. I understand. I would just say that I had amazing teammates and great coaches, and one of the best all-time Gaston County girls basketball coaches, and I wouldn’t be in the position I am today without my brothers and Coach Bridges.” ■

— By Kathy Blake

Basketball:

• East Gaston High School (2003-2007): Total points – 1,332. Rebounds – 490. Steals –298. Assists – 250. Free throws – 411-564 (73%). Team captain – two years. Team record – 76-30.

• Three-time All-Gazette player.

• Two-time All-Gaston Observer.

• Three-time All-Conference.

• Other: Team rebounding award; Most Versatile award; MVP; Co-MVP; A/B Honor Roll.

Wingate University (2007-2011): Total points – 946. Rebounds – 324. Steals – 147. Assists – 202. Highlights – Played 33 games as a freshman, averaging 6.6 points and 2.3 rebounds. Third on team charts 2008-09 at 9.2 ppg; season-high 23 points in 84-7 overtime win over Mars Hill. In 2009-2010, scored in doublefigures 11 times; played 26 games, starting six. Season-high 28 points at Lincoln Memorial.

The Mount Holly Sports Hall of Fame Supports these non-profits.

Mt. Holly Community Relief Organization

Mt. Holly

Middle School Athletics

The Lost Boyz Wrestling

Ida Rankin Elementary Safety Patrol

Mount Holly Athletic Association

The Mount Holly Sports Hall of Fame is a 501(c)3 organization that celebrates Mount Holly’s rich sports history and supports future athletes through its work with local organizations. Classified as a public charity, we welcome your tax deductible gifts. In addition to our practice of supporting local charities, we are also funding college scholarships for deserving local students.

The mailing address for your gift is, 212 Dogwood Dr., Mount Holly, NC 28120.