GATHERING GROUNDS

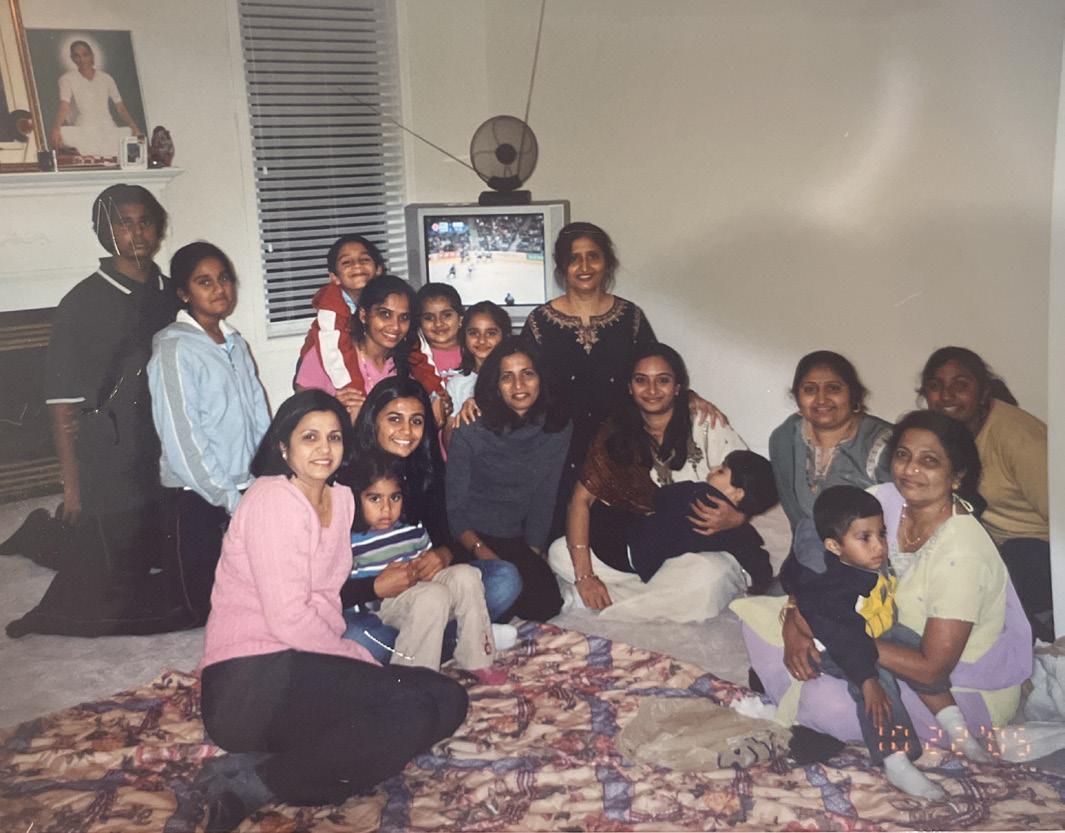

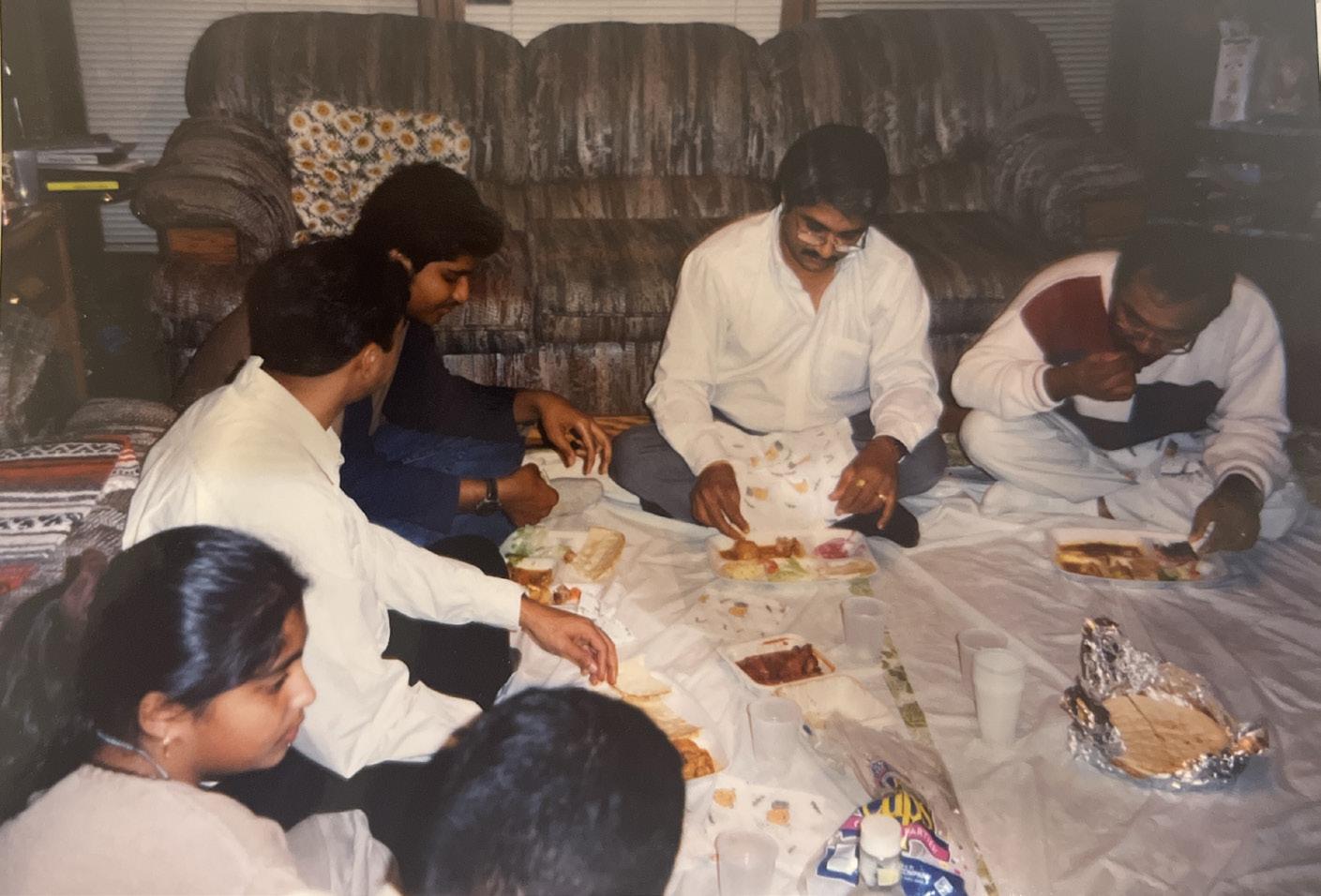

Growing Up in an American single-family home with my extended multigenerational family, I experienced gatherings in unconventional ways—typically in open, unobstructed floor spaces.

Growing Up in an American single-family home with my extended multigenerational family, I experienced gatherings in unconventional ways—typically in open, unobstructed floor spaces.

Growing up, I realized that the way I lived was different from most people in the U.S. I was born into a multigenerational home, where I lived with my great-grandparents, grandparents, parents, aunts and uncles, cousins, and siblings in a single-family home in New Jersey.

The article “Social Norms: Gender Roles and Time Use; Multigenerational Households in India” by Aseem Hasnain and Abilasha Srivastava explores the continued relevance of multigenerational living in South Asian countries. The multigenerational family structure addresses both financial and social needs, which have become increasingly important due to rising housing costs and the expenses of child and elderly care. The authors argue that the joint-family system provides protection and a sense of identity, fostering deeper connections across generations while preserving traditions. They note, “Multigenerational living has evolved from traditional, hierarchical structures with shared responsibilities and simple communal spaces to modern arrangements that prioritize flexibility, privacy, and technological integration” (Hasnain & Srivastava). Thus, my family continued this tradition when moving to the U.S.

“Social Norms: Gender Roles and Time Use; Multigenerational Households in India” by Aseem Hasnain and Abilasha Srivastava

Although, looking back, the house was small, it felt spacious and comfortable for my family, as if we could accommodate even more people. I remember those years of my life as being deeply connected to my family and my culture because we always found ways to gather. Recipes, identity, and traditions were strongly upheld.

“This photo essay by Mary Kang captures Nepali-speaking Bhutanese refugee multigenerational families living in Austin, Texas. The photographer was ‘drawn to their interdependence and reliance on community as a form of resilience while readjusting in their new land’ (Kang). The series of photos reflects my upbringing.

Photo 1: The structure of the house is reflected in everyone’s positions. The oldest family members sit on the couch or in chairs, as they are less mobile. Younger children sit on the floor, as they bear fewer responsibilities and are more mobile. In the middle are the parents, who are working, cooking, and maintaining the household.

Photo 2: Bhutanese Nepali American elders prepare for the citizenship test. Because learning English can be challenging for the elderly, the younger generation assists them in studying U.S. history, as they have a stronger grasp of the language.

Photo 3: Hospitality is a key aspect of Bhutanese Nepali culture. Food plays an important role in maintaining connections to cultural roots. Older generations uphold these traditional cultural identities, especially after moving to the United States.

4: A typical family gathering.

Gathering in my family typically took place in open, unobstructed spaces. I remember the so-called "living room" in our house being the main gathering area; it didn’t have the typical couch and coffee table. Instead, the floor served as the free, open space where we all sat and came together. The furniture that did exist was pushed against the walls and rejected. I recall when visitors would come, my grandmother would guide them to sit on the floor. It was awkward at first, but it helped guests interact with everyone and feel a part of the family and our discussions. This furniture-less space allowed for flexibility and adaptability.

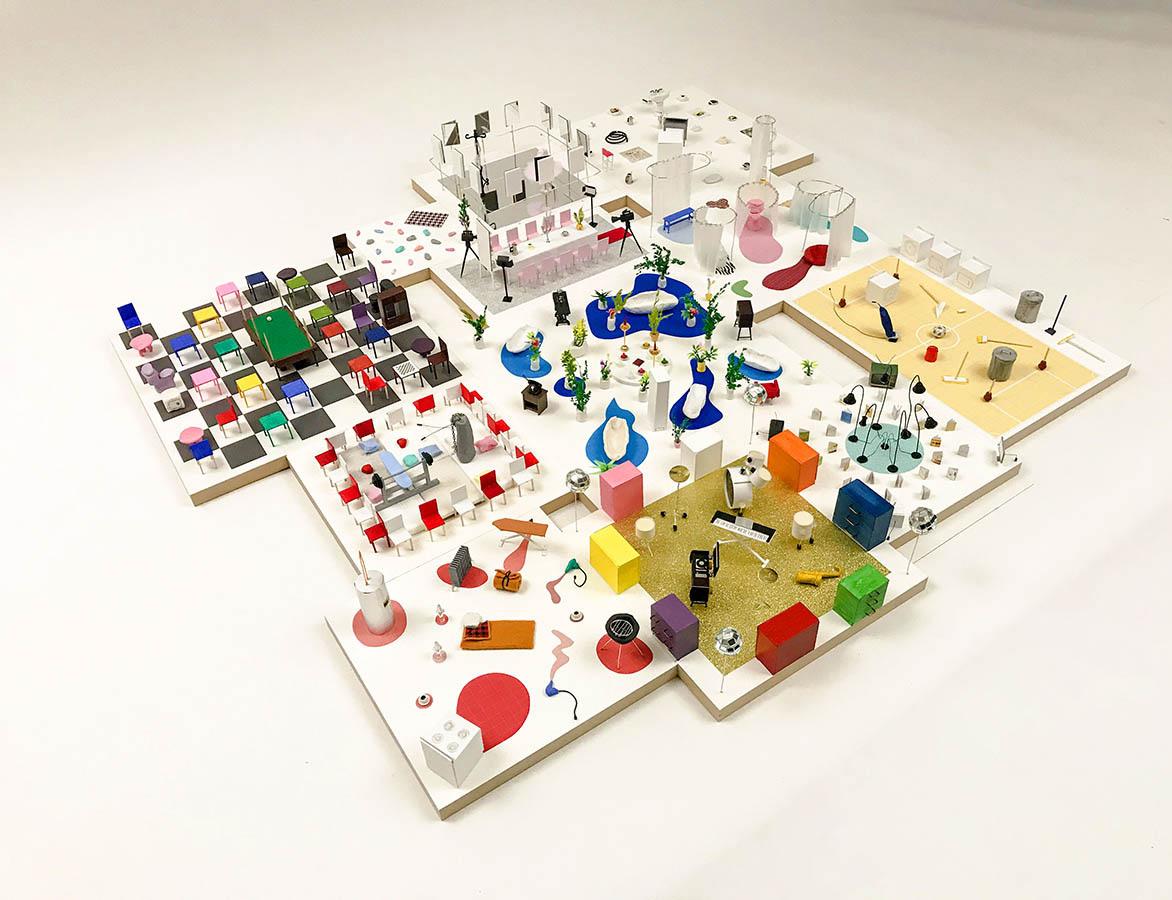

The project "Empty House" by the Harvard Graduate School of Design, instructed by Iwan Baan and Tatiana Bilbao, similarly allows for open interpretation of space. Unlike my family’s home, where the lack of furniture leaves spaces up for interpretation, this project relies solely on furniture to define areas, with no walls.

“By inverting the object and architecture relationship, not only does this liberate itself from the idea of traditional domesticity, but it also allows you to rethink the definition of any given space” (Kim).

This open space holds many fond memories of my family. The floor was our venue; it hosted multiple weddings across generations, baby showers, birthday celebrations, and graduation parties. The floor was our temple, where we held many religious prayer ceremonies. The floor was our dining table; every night, we gathered on the floor to eat together. The floor was our playground, where my cousins and I spent most of our time playing. The floor was our bedroom; with just padding on the ground to sleep on. The floor was our office/workspace; my generation did schoolwork, the generation above did college and office work, my grandparents read the newspaper, and my great-grandparents relaxed, sharing stories and enjoying our company. The floor was everything to us.

Traditional courtyard houses support multigenerational living— something especially relevant in non-Western countries—and are intentionally designed to promote gathering. The article “Courtyards: The Heart of Multi-Generational Houses in India” by Ankitha Gattupalli states that in India, the courtyard is the heart of the home. These traditional houses remain significant as they foster multigenerational living and are designed to encourage communal space. A courtyard is an open-to-sky area, typically enclosed on all four sides (sometimes three), and almost always empty. The rooms of the residence usually face the courtyard, inviting family members to use it as a shared space, regardless of age or status. The courtyard serves multiple purposes, from religious ceremonies to family meals to casual conversation. It is a flexible space that adapts to the moment’s needs.

The photo essay by Anuradha Pathak highlights the different activities that occur in a traditional courtyard house in India. The courtyard is an extension to different activities and aspects of daily life. These rituals are translated by my family in their “American Courtyard”.

Photo 1: Shows the courtyard as an extension of the laundry room. The clothes and blankets are being washed and dried.

Photo 2: The Courtyard as an extension of the temple. The Courtyard is being used to set up for the Durga Pooja.

Photo 3: The courtyard as an extension of the entertainment space. The courtyard is hosting friends and family to play Carrom.

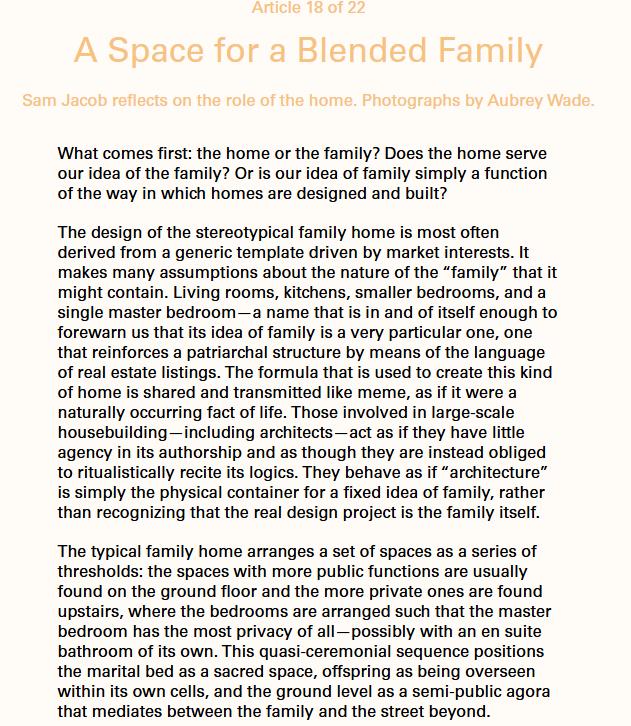

When my family immigrated to the U.S. as a joint family unit, we moved into an American home, but the rigid furniture and compartmentalized spaces restricted our ability to gather. The rooms and walls became isolating, separating us. The design of the house did not reflect the true nature of our connections and undermined the potential for multigenerational bonding and shared experiences. Sam Jacob’s research, “A Space for a Blended Family,” critiques the stereotypical home design for its narrow view of family, pointing out that it’s a “physical container for a fixed idea of family, rather than recognizing that the real design project is the family itself.” The potential for family is much more diverse than just a nuclear model. As the author mentions, “architecture isn’t neutral,” and it needs to evolve to reflect the many ways families live and connect today.

As a result, my family had to start reimagining the elements of the traditional courtyard house within the American home to encourage gathering. By pushing the furniture back, we created open floor space where we could gather. Slowly, the existing furniture was ignored and discarded, and the open floor became our true gathering space, where all of us could sit together.

When we sat on the ground, everyone was on the same level, creating a sense of equality and connection that bridged generations. It was a space where stories, wisdom, and traditions were passed down, and our identities were strengthened. I have vivid memories of learning to roll rotis with my grandmother while she shared her experiences of immigrating to the U.S. I remember my grandparents teaching me how to do rangoli designs, my aunts teaching us how to do garba, my grandpa lighting sparklers with us during Diwali, and my great-grandmother telling me stories of her childhood in India, my parents helping us with schoolwork, my cousin and I teaching the elderly's English and how to read. It was a space where wisdom flowed freely, and through sitting together, we shared conversations, debates, and stories that united us all.

Similarly, the project “Rights on Carpet” by Manuel Herz is a carpet designed to reflect human rights, inviting people to sit and share ideas. The carpet initiates gathering, starting discussion and debates around humanitarianism. The design represents the 4 primary treaties and “becomes an architectural device for curating the exchange between people” (Herz). The flat carpet becomes a mechanism, like the floor, for connection, discussion, and debate.

The concepts of cultural translation, adaptation, flexibility, collective living, and the connection to open, unobstructed floor space were all important and valuable aspects of my upbringing.

I propose a prototype for an alternative form of collective living, one without walls, where all spaces are defined by the neutral gridded floor. The only vertical structures would house the essential private functions: bathroom, circulation, and mechanical systems. The rest of the space would be completely adaptable and flexible, free from traditional compartmentalization. These open areas can be interpreted and used in various ways, allowing for greater freedom and fluidity in how people live and interact within the space.

This concept was essentially an infinite flat grid that, devoid of architectural diversity, would even the playing field when it came to social strata and lifestyles. The gridded design represents all the functions and programs that exist on the grid, creating equal access to essential resources and technology. The film furthers their discussion by proposing life "without three dimensional structures as a basis". They imagined it as a continuous network that anyone could plug into and use when needed. A Uniform surface that would serve all. Where my project, similarly, has the same emphasis on the floor; the floor as a neutral gridded surface, containing all the functions

The grid in “La Maison De La Celle-Saint-Cloud” By Jean Pierre functioned as a rigid framework, controlling every surface, reducing everything to a uniform aesthetic. My proposal uses the grid not as a constraint but as a foundation for adaptability and collective living. In both projects, the grid serves as a neutral yet liberating foundation, defining space while allowing infinite possibilities for use and adaptation.

Baan and Tatiana Bilbao

The proposal is to design a living space where traditional architectural divisions like kitchens, bedrooms, and closets are eliminated. Instead, the design focuses on a flexible, open layout where the space is shaped by the objects people use, rather than predefined rooms. The objects—such as furniture, personal items, and equipment—define the spaces and their function, allowing for a more fluid, adaptable environment. This approach rethinks domesticity by liberating the home from conventional layouts, offering a new way to organize and inhabit space based on individual needs and possessions. In this project and in my proposal, there are no walls, spaces are left for interpretation allowing for flexibility and adaptability.

The Space Odyssey Room is minimalistic, adaptable, and free from rigid boundaries similar to my project. My protoype envisions a collective living space where walls are eliminated, and the layout is defined by a neutral, gridded floor with domestic elements ontop, similar to the room.