somersetwildlife.org/honeygar

somersetwildlife.org/honeygar

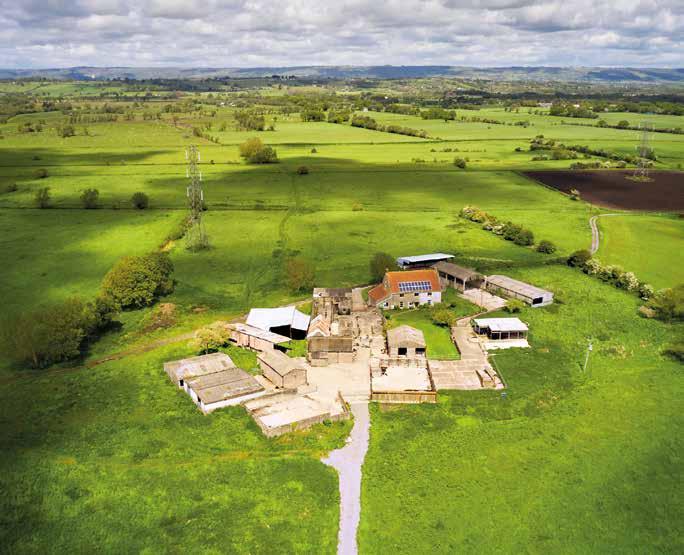

Honeygar has always been about possibility. In 2022, we set out with a bold ambition: to take land left devastated after years of intensive farming and show how it could be restored for wildlife, for climate, and for people. Three years on, the results are here to see – peat being restored, nature thriving, and knowledge growing every day.

This report marks an important milestone. Thanks to the generosity of our supporters, we have been able to complete the first phase of Honeygar’s restoration: buying the land, carrying out the first interventions, and putting in place the monitoring that tells us how the landscape is responding –creating a benchmark for our work in years to come. This latest report demonstrates everything that’s been achieved over three challenging, but remarkable years, and is an opportunity to celebrate what we have achieved together.

But the work does not stop here.

The coming years will be about taking forward what we have learned, to identify how we support the site as it keeps moving towards a richer, wilder state. We will build resilience for the future, and, most importantly, create a new hub at Honeygar – transforming its buildings into a place where research, innovation and inspiration can flourish for the benefit of all.

This record is both a celebration of what has been achieved so far and a first glimpse of the next chapter in Honeygar’s story.

Georgia Dent, Chief Executive Officer

“Honeygar is no longer just a farm – it is a meeting place for ideas, a catalyst for change, and a bridge between past and future.”

Honeygar lies at the centre of the Avalon Marshes – a landscape shaped for millennia by water, peat, and people. Generations have worked this land, cutting peat, farming, and adapting to the ever-changing water levels, leaving a rich cultural identity.

That history is still written into the land, in the patterns of the fields, the ditches, and the peat beneath our feet. Today, the reserves that neighbour Honeygar – Westhay Moor, Catcott, and the Tealham and Tadham Moors – form a connected chain of habitats, with Honeygar now becoming a central part of that living landscape.

Honeygar’s location makes it more than just one isolated site. By holding water on the land, trialling new grazing systems, and testing how peat can be brought back to life, Honeygar is influencing how we manage the wider Somerset Levels. It has quickly become a demonstration of what is possible when we work with nature, not against it.

Peat is an accumulation of partially decayed vegetation or organic matter over 100s – and in the case of Honeygar – 1000s of years. It is uniquely formed in natural wetlands, where flooding or stagnant water obstructs the flow of oxygen from the atmosphere, slowing or even halting the rate of decomposition. The result of this lack of decomposition means that the Carbon accumulated in the vegetation during the season of its growth is effectively captured by the peat indefinitely if water remains stagnant and is kept at a level that saturated the peat.

Water is the key to maintaining the peat, as it is for retaining the biodiverse wetland features. On Honeygar we have deployed water holding features to give us the best chance of retaining enough water to maintain the peat and reduce the potential for decomposition. The intense monitoring on Honeygar has started to identify how and where this is working.

James Grischeff, Director of Nature Recovery, Somerset Wildlife Trust

Over the past three years, Honeygar has been given new life. What was once intensively farmed land is now beginning to recover. Its peat is in a healthier condition, grasslands are responding to new grazing, and a plethora of wildlife has started to find its way back.

Careful targeted hydrological work has improved moisture levels in the peat and created seasonal pools, while pioneering trials such as solar pumping have helped to stabilise water levels and protect the peat.

Alongside this, a new grazing system is restoring the structure of the land, and innovative science is giving us fresh insights into everything from greenhouse gas emissions to bird song. Volunteers have played their part too, surveying wildlife and helping us with the ongoing restoration of the land.

Here are some of the standout changes so far:

• Peat now holding more water than ever before

• Rotational grazing reshaping grasslands and soils

• Bunding and sluices raising water tables

• Solar pumping trial showing early success

• Science reveals changes from greenhouse gases to bird calls

• Honeygar emerging as a living laboratory

• Volunteers helping to survey and restore

340,000m³ of water stored in 2024 — equal to 136 Olympic swimming pools

Water table rising on average 15cm each year since interventions began

45cm rise in water table between March 2023 and March 2024

4 million bird calls analysed through AI bioacoustics

120+ bird species detected — including night heron, bittern and snipe

Two consecutive years of harvest mouse surveys have now found over 100 nests, showing small mammals returning, such as shrews, water voles, field voles and many species of mouse.

Dozens of volunteers active through the Honeygar Rangers

One of the most important steps at Honeygar has been to hold more water on the land in order to begin restoring its deep peat. Over the past three years, we have installed a series of sheet metal bunds in the streams and waterways that allow us to manage Honeygar’s water table independently from the wider drainage network of the Somerset Levels. This independence is crucial – it means we can raise water levels to suit the unique need of the site without affecting neighbouring land, slowing the degradation of peat and creating the conditions for new wetland habitats to return.

The benefits are already visible. Where once summer droughts left fields dry and cracked, we now see seasonal ponds forming and water being retained for much longer. This extra water benefits not just the peat, but the whole living landscape — supporting fen vegetation, creating niches for invertebrates and amphibians, and buffering the site against dry summers. At the same time, our innovative trial of solar pumps has shown how small amounts of water can be moved efficiently around the site.

There is still more to do. Parts of the site are yet to undergo hydrological interventions, and we know that climate extremes – from droughts to sudden intense downpours – will test the system in years to come. The next phase of work, including new bunds planned for autumn 2025, will help strengthen the site’s resilience.

Honeygar’s story is also part of something bigger. As a pilot site within the Adapting the Levels Landscape Recovery Project, the lessons we learn here – from solar pumps to seasonal water storage – will help shape how the wider Somerset Levels adapt to climate change.

When Honeygar was first acquired, the land was being managed as an intensive dairy farm. An excessively large herd of cows and constant grazing had left soils compacted and grasslands degraded. Over the past three years, that system has been replaced with a new approach — one that works with nature rather than against it.

Today, Honeygar is home to a small herd of around forty cattle, managed through a low-density, rotational system. Instead of grazing the same pastures continuously, the animals are moved through different areas in turn, giving the land time to rest and recover. This approach improves the length and composition of the grass, helps soils breathe again, and reduces nutrient loads — all of which are crucial for protecting the site.

The difference is already visible. Grasslands are developing greater variety, with tussocks, herbs and flowers returning. Wetter fields are creating space for wading birds and invertebrates. And the cattle themselves, slower-moving and lighter on the land than intensive dairy herds, are shaping a landscape that is more diverse, more resilient, and better for wildlife.

By farming differently, Honeygar is showing that productive land management and nature recovery can go hand in hand. This new system protects the peat, restores the grasslands, and demonstrates a model of farming that could be adopted more widely across the Somerset Levels and other low lying land.

Rotational grazing means moving cattle between fields instead of leaving them in one place. Each area gets a chance to rest and regrow, improving soils and creating varied grassland that supports more wildlife. At Honeygar, it also helps protect the peat by keeping vegetation healthy and reducing nutrient pressure.

Even in just three years, Honeygar feels more alive. As water levels have risen and less intensive farming practices are introduced, the land has offered new opportunities for wildlife to return. Seasonal ponds appear across the fields, drawing in wading birds and insects. Longer, more varied grasslands are providing cover for small mammals. And the air is rich with birdsong — a chorus recorded and revealed through our pioneering bioacoustic monitoring supported by innovative artificial analysis (AI) analysis.

The signs are already encouraging. More than 120 bird species have been recorded, from wrens and skylarks to bitterns and even the rare night heron. Snipe are drumming over wetter fields, harvest mice have been found nesting in tussocky grass, and moth surveys are adding hundreds of species to the site’s growing list. Each new find tells the same story: that once land is given a chance, wildlife responds positively.

Honeygar is still at the start of its journey, but the early recovery is a powerful reminder of what is possible. Every call, footprint, and nest is a marker of change — and a glimpse of the wilder future that lies ahead.

Baseline surveys record skylark, meadow pipit, and reed bunting, while plant surveys note grass-dominated land with few wetland herbs — a clear picture of what recovery must build from.

Snipe begin drumming over wetter fields, joined by reed and sedge warblers. First flushes of rushes and sedges appear in damper areas, and early moth surveys reveal a surprisingly rich nocturnal community.

Harvest mouse nests discovered in tussocky grassland — a milestone for small mammals. Bioacoustic monitoring detects more than 120 bird species, from wrens and goldfinches to rare night herons and booming bitterns. Marsh marigold and meadow buttercup spread through wetter pastures, adding colour and structure to the grasslands.

The list of moths grow into the hundreds, dragonflies and damselflies expand into new seasonal ponds, and barn owls are seen quartering the fields. Wetter soils support an increasing mix of sedges, rushes, and flowering wetland plants, creating more niches for invertebrates and breeding waders alike.

Honeygar is more than a project in isolation. Its position between Westhay Moor, Catcott and the Tealham and Tadham Moors, makes it a vital link in the chain of reserves that make up the Avalon Marshes. By restoring its soils and water, Honeygar is helping to stitch these sites together into a more resilient whole – creating the kind of connected landscape that allows wildlife to thrive and move freely across the Somerset Levels.

That influence extends beyond the land itself. Over the past three years, Honeygar has become an open-air classroom – a place where farmers, researchers, and conservationists can see peat rewetting, grazing changes and monitoring technology in action. From university students and school groups to the information shared with local farmers and landowners, what has been learned here is already shaping decisions far beyond Honeygar’s boundaries.

The people of the Somerset Levels have also stepped forward to play their part. The Honeygar Rangers volunteer group is now a regular presence on site, supporting surveys and helping the monumental changes to land management. Their work shows how a project rooted in science can also grow into a community of guardians, with people as much a part of the landscape’s renewal as the wildlife itself.

Honeygar is also central to wider change. As part of the Adapting the Levels Landscape Recovery Project, it is a testing ground for ideas that could reshape how water and land are managed across the Brue Valley. Here, trials of bunding, solar pumping and watertable management are providing lessons that will influence the future of farming and nature conservation across Somerset’s peatlands.

“What happens at Honeygar does not stay at Honeygar – it ripples out across the Avalon Marshes, shaping the future of the Somerset Levels.”

“Here, science, community and landscape come together – showing what is possible when we work with nature, not against it.”

Through consultation, open days, and regular updates, Honeygar has become a place where people can see the possibilities of a different future for the Levels. What began as an ambitious idea to restore a single farm is now inspiring others to think bigger, to share knowledge, and to imagine a landscape where nature and people thrive together.

The first three years at Honeygar have shown just how quickly change can happen — and laid the foundations for what comes next.

Over the coming years, we will deepen and extend the work already begun. More water management including more bunds and sluices being installed, and our trial of solar-powered pumping will be scaled up, helping to keep water tables high and stable so that the peat beneath our feet is protected for the long term. Grazing will continue to evolve, with carefully managed, low-density herds reducing nutrient loads and keeping soils in better condition. Our science will expand too, from greenhouse gas monitoring to our continued work with bioacoustics, ensuring Honeygar remains a real-time laboratory where we can learn how restoration unfolds.

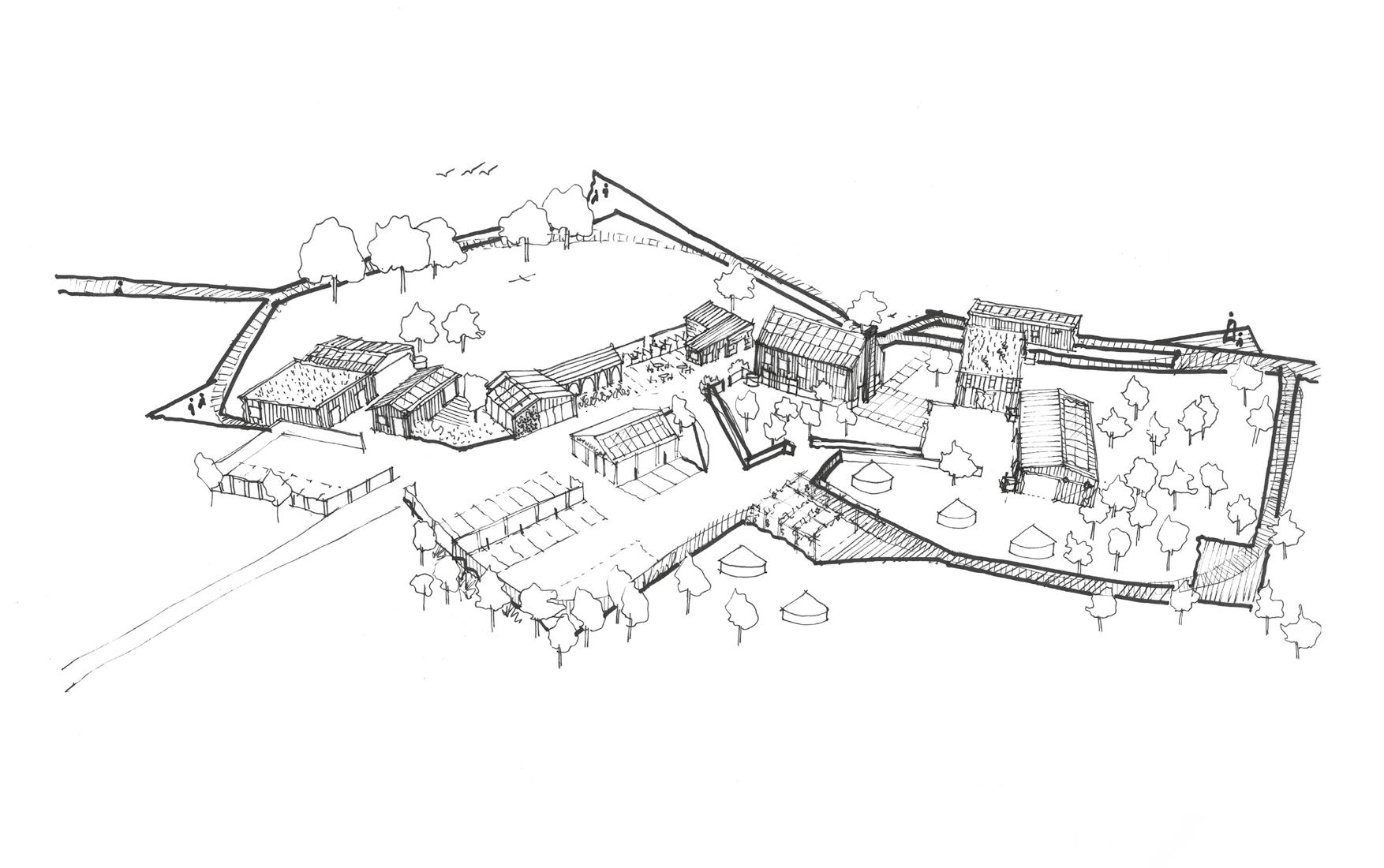

But perhaps most significantly, this period will mark the beginning of a bold new chapter: the transformation of Honeygar’s buildings into a UK centre for research, learning and inspiration.

“Honeygar is a place of learning as much as it is of restoration – every pond, bird call and water level tells us something new.”

From the outset, Honeygar was more than restoring a single farm. It was about creating a place that could influence and inspire change far beyond its boundaries. The next phase will bring that vision into focus, as the old agricultural buildings are reimagined as a centre for lowland peat research and collaboration.

Specialist laboratories and field facilities will allow scientists to test and process data on water, soils, greenhouse gases, and biodiversity at pace, accelerating what we can learn from restoration. Flexible teaching and workshop spaces will welcome students, farmers, and practitioners, turning Honeygar into a place where ideas and solutions are shared. For the wider community, a lookout and exhibition space will provide an opportunity to see and understand the changes happening across the landscape, connecting people more closely with the story of recovery and a sense of place.

The buildings themselves will embody the values of the project. They will be low-carbon and climate-ready, aiming for zero-carbon operation, flood resilience and off-grid energy use. They will remain rooted in place, retaining the character of Honeygar’s farming heritage while re-using materials wherever possible. They will be nature-positive, with features that support wildlife woven into their very design. And above all, they will be inclusive and accessible, welcoming people of all abilities and backgrounds.

It is an ambitious undertaking, but one that grows naturally from the success of the past three years. With the land secured, the water restored, and the monitoring in place, we can now look ahead with confidence. Honeygar is no longer just a farm in transition – it is becoming a centre of knowledge, resilience and hope for peatlands everywhere.

“Rooted in its farming heritage, but designed for a climate-positive future.”

In just three short years, Honeygar has changed beyond recognition. What was once drained and farmed intensively is now a recovering landscape — wetter peat, richer grasslands, and wildlife beginning to return.

Careful interventions and bold experiments have given the land space to heal, and the results are already clear: Honeygar is becoming a place where nature, farming, and science work hand in hand to shape a better future –for nature and climate.

The story of Honeygar is still unfolding — and the most exciting chapters are yet to come. Providing financial support is one of the ways that you can be part of the Honeygar’s story. Please get in touch to find out more about the range of ways you can provide vital funds to support this very special project.

The Accomplishment Trust

The Banister Charitable Trust

Garfield Weston Foundation

Golden Bottle Trust

Green Recovery Challenge Fund

The Harris Foundation

John Swire 1989 Charitable Trust

Nature for Climate Peatland Grant Scheme –Discovery Grant

Royal Society of Wildlife Trusts

The Steel Charitable Trust

Supported by Players of People’s Postcode Lottery

Wilder Sensing

Barbara Cheney

Dame Margaret Drabble

Mark and Marnie Franklin

Patrick Thomson

Professor Michael Sleigh

Pioneers who wish to remain anonymous

In memory of Heather Corrie

The estate of the late David Whishart

Members of Somerset Wildlife Trust and supporters who have donated to the Honeygar Appeals

Stay in touch with the Honeygar

somersetwildlife.org/honeygar

To discuss progress and see how you can support our work to make our vision a reality, please contact:

Amanda Strowger

Grants and Project Development Manager

Telephone: 07596 327495

Email: amanda.strowger@somersetwildlife.org

Michael Woodman

Philanthropy Manager

Telephone: 07525 595205

Email: michael.woodman@somersetwildlife.org

Somerset Wildlife Trust 34 Wellington Road Taunton

Somerset TA1 5AW 01823 652400

Charity number 238372

Design: specialdesignstudio.co.uk October 2025

All images © SWT, unless where stated.

Company number 818162 somersetwildlife.org