FOCUS HIDDEN PRESSURES

STAFF

MANAGING

RONIT

KIRAN

HOLDEN

EMILIANO

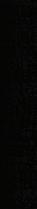

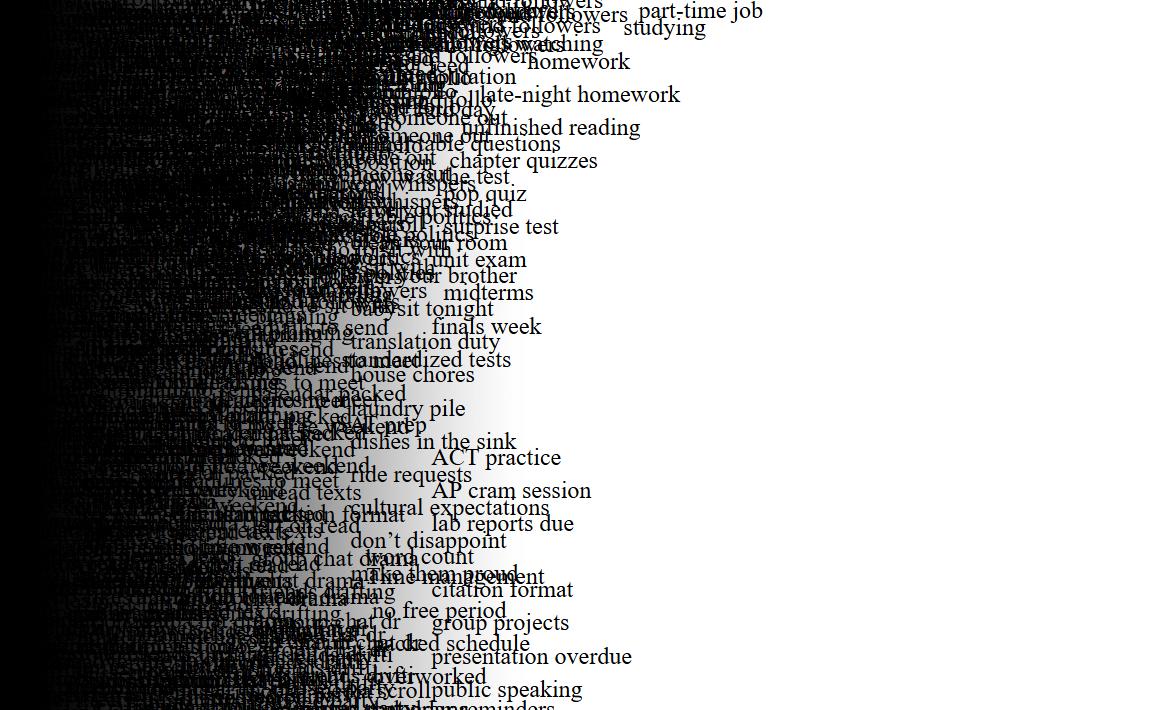

HIDDEN PRESSURES

We run on invisible pressure.

If you stand still long enough, you’ll feel it: the weight everyone carries but few acknowledge. We all have our emotional baggage, buried beneath the surface, building silently until something breaks.

No matter where we are, the people around us who seem perfectly fine might be struggling with something we can’t see.

This magazine brings hidden pressures into the light. It reminds us that we all fight our own battles, and that none of us is truly alone.

Because pressure is everywhere. But when we name it, understand it, and share it, we can stop letting it control us. We can use it.

Andrew Ye and Kayden Zhong Editors-in-Chief

INVISIBLE INFLUENCE

The expectations parents have for their children can affect their performance, but with the proper support, they can also help them improve academically.

BY HOLDEN PURVIS AND DOMINIC LIAW

From the very beginning of Lower School, junior Dylan Bosita knew exactly what his parents expected of him.

No A, no play.

There were no exceptions — if he didn’t bring home straight As, he couldn’t play baseball or participate in any other extracurricular activities.

At the time, those rules felt too strict. But over the years he’s come to see them as essential in developing the work ethic, dedication and focus he needs to achieve his goals.

And as he grew up, those rules gradually became more flexible as he earned trust.

“From a young age, being so involved with my academics, with my studies and with my school career, it really taught me that that was the level of intention, the level of dedication I needed to put into my own studies when I got older,” Bosita said.

Bosita has always had great expectations. Both of his parents attended Stanford University, and he grew up bonding with his dad over the school’s sports.

What started as a shared love for sports evolved into a personal ambition to attend

“

the school himself. And while he used to think his parents pressured him to go there, he realized it was an internal expectation.

“My parents have told me throughout the years they do not expect me, nor do they want to force me to go to Stanford,” Bosita said. “They would love it if I went to Stanford, but they don’t want to put any external pressure on me to go there. They want my love for Stanford to be genuine and for it to be derived from my own heart.”

He had compared himself, sometimes unhealthily, to his two high-achieving older brothers, and he expected the same achievement from himself. When both of his brothers were accepted into Stanford, it only intensified his dream.

But it never altered his parents’ expectations of him.

“My parents, from day one, have told me there are no favorites in this household, and we will never compare you to your brothers,” Bosita said.

He hopes that Stanford can be something that can be experienced by the whole family — a continuation of the unbreakable bonds that have shaped his life.

“We are literally a band of brothers,”

Bosita said.

Ultimately, his parents’ early guidelines helped shape his habits and build a foundation of self-motivation to make him successful. But that drive is now entirely his own.

As the years go on, I think they’ve learned that they can trust us,” Bosita said. “Of course, they’re still there when we want guidance, and they’re still there to offer their opinion and check our grades, to make sure we aren’t straying from the path. But in the end, it’s up to us, me and my brothers, to really push ourselves and not go past that point of diminishing returns.”

Jeanne Rosenfeld finds that her leniency reflects her son, sophomore Bruce Rosenfeld’s work ethic. Driven and self motivated, Jeanne Rosenfeld leans into other aspects of parental roles.

“I do feel like I have a son that puts a lot of pressure on himself. So, for me, as a parent to put pressure, it’s not gonna help him, but I feel like it would hurt him,” Rosenfeld said. “So he does have a lot of inner accountability in his life, and so I feel like it’s my role really just to support and guide him rather than try to micromanage him. Because he does not need that.”

Rosenfeld emphasizes natural consequences as opposed to rigid parental correc-

I do feel like I have a son that puts a lot of pressure on himself. So, for me, as a parent to put pressure, it’s not gonna help him, but I feel like it would hurt him.

- Jeanne Rosenfeld, Parent

tion. In high school, sub par performances become apparent in more than just an academic setting.

“If he doesn’t work hard enough on a paper or hard enough on a report, well, he’s gonna see the grade, and he’s gonna do what it takes. If he doesn’t like that, then he’s going to try to do better,” Rosenfeld said. “So I do feel like natural consequences kids, young adults learn better than a mother or a father harping on them. I don’t feel like that’s gonna make him better. It’s just gonna make him probably make the same grade on the test, but just be stressed out.”

Not all kids are self driven like Bruce, however. Differences in work ethic leads to various approaches.

“I think every kid is different, every parent is different, and I would never be put-

ting my opinion on a family or a parent, because they have a different situation,” Rosenfeld said. “And I have very high standards. I think every parent, especially at St. Mark’s, has very high standards for their kids as I do. I think it’s just a style too on how we deal with our children.”

With challenging classes and high expectations from the school, Rosenfeld recognizes the difficult environment. Thus, she values positive encouragement and praise, especially when school may be harder.

“He’s definitely adapting, but do I feel that there’s a lot of pressure at St. Mark’s,” Rosenfeld said. “I try to teach him, ‘do not compare yourself to others. Be the best you can.’ And that is very difficult, especially with the competition at a school like St. Mark’s, always wanting to

be the best. And again, he pushes himself so hard that I feel I am more of the cheerleader. ‘You are amazing, you are great, you do not need to compare yourself, you just be you.’”

Rosenfeld understands the importance of freedom and independence, but her assistance isn’t sidelined by these values.

“If something gets overwhelming, we’re there, we’re a landing spot, but we’re not the doer, the creator, the time manager, that’s not how we feel our role is,” Rosenfeld said. “But we will always be there when things get super tough. He knows where he can be, where he can come, and we will help him work through any problems or issues, but at this point, he needs to be the one really to come to us.”

The Bosita brothers stand with their parents, represented by expectations the brothers feel they need to achieve.

BY SEBASTIAN GARCIA-TOLEDO AND SHIV BHANDARI

Burnout: no motivation, no enthusiasm, no drive. It is the complete and debilitating, mental, physical, and emotional exhaustion towards an activity, and the chronic condition can affect students even in areas that they once loved, completely eliminating any desire to continue in them. It can impact performance in sports, academics and interactions with family and friends, isolating students as they spiral into disarray.

“Burnout describes the bottom where motivation is completely absent,” Upper School counselor Mary Bonsu said. “It’s just gone. Burnout comes as a result of doing something repeatedly and not getting anything out of it. No joy, no sense of reward, no dopamine hit; it’s just this constant day in and day out activity that (people) just don’t love anymore.”

It is important to differentiate simple low energy or lack of motivation from burnout. Low energy is a common occurrence and easily resolvable, something that is occasional and finite, where burnout is chronic and constant, requiring more rigorous attention and effort to get past.

“Some people get short-term spurts of low motivation, where they need a break from school,” Bonsu said. “If we find ways to motivate them, we don’t call that burnout. Burnout is persistent. It lasts longer than a couple of weeks. It kind of looks like depression in terms of the symptoms where (people) aren’t interested in things anymore.”

Burnout can happen in students and professionals alike, where their passion for their job fades dramatically and their drive to work ceases. According to the Society for

PHOTO EMILIANO MAYO MEJIA

Upper School

Counselor Dr. Mary Bonsu is one of a number of counselors on-campus in the Marksmen Wellness Center.

Students suffering from stress caused by pressures in their lives often enter a state of mental, emotional and physical exhaustion, colloquially known as “burnout.”

BURNT

Human Resource Management (SHRM), 44 percent of United States employees feel burnt out constantly, with up to 76 percent reporting it occasionally. Not only does burnout affect the employee, but the company as well: money allocated to burnout health topped out at $190 billion in 2024, and burntout employees contributed $3,400 of every $10,000 in salary due to lower productivity.

“Burnout can happen around something that someone once loved or around a duty or job,” Bonsu said. “You might see healthcare workers leaving their jobs because they just don’t love it anymore or teachers exiting the classroom and trying to find other jobs because they don’t have the motivation to continue along (their) paths. You might see students having academic burnout, and it doesn’t matter what the subject is: it could have been their favorite subject. They’re just in the constant onslaught of homework, studying and tests.”

Junior Julian Gerstle has suffered from burnout, and his experience aligns with its common tropes: chronic exhaustion, lack of motivation, and an apathetic attitude towards the task at hand.

“I had really bad burnout in the last quarter of my sophomore year because I was just overwhelmed with work. It was a lot of homework and menial tasks. I had an existential crisis,” Gerstle said. “I was doing all this work, but what was the point of doing any of it? My homework was just busy work my teacher was giving me so I can go turn it in the next day. I felt this self-perpetuating cycle, and I was seeing it very cynically.”

In institutions like St. Mark’s, where competition is high, work is intense, and the need to push oneself to be better is er-present, someone can misinterpret the symptoms of burnout as just being normal.

This can lead to them not reaching out, or struggling to do so, because they believe their situation is the default.

“I just assumed that all my friends were feeling the same thing, so I never told anyone that I was feeling burned out,” Gerstle said. “Overworking yourself is definitely a thing here. It’s killing people, but they have to do it to stay ahead.”

The school, however, has readily available mental health resources to help students who may be experiencing burnout. Not only are counselors like Bonsu able to discuss the root of why the student could be experiencing the exhaustion, but they are also able to create strategies with the student to either regain their motivation or move past the object of their burnout.

“There are ways to prevent burnout by checking in with yourself if you’re experiencing low motivation or something’s not fun anymore,” Bonsu said. “Are you putting enough time into the things that you love? Are you spending time with friends? Are you sleeping well? Are you eating well? Are you managing your digital devices well? All of these other factors that can contribute to burnout. So we want to look at all of that and see if we can make some tweaks and some recommendations based on what will give us the most bang for our buck.”

Burnout can also be difficult to diagnose because some individuals can struggle to source it, feeling exhaustion, but unaware that their apprehension towards an activity is actually burnout. This can complicate the process of treating it, but students can be aided by the Health and Wellness office.

“One of the main things about counseling is getting to the root of the (problem),” Bonsu said. “Because everyone’s burnout doesn’t look the same. Somebody might come in burnt out on their sport, and their classes are fine. They’re going to have a different conversation than with someone who doesn’t want to do another math problem. We figure out where that (apathy) is coming from and see if there are factors that we can adjust.”

Bonsu also wanted to highlight the effect that friends can have in the treatment process, especially with getting burnt out students into the Health and Wellness Office. Because peers are the people who would be nearest to a troubled student, it is imperative that they speak up to help their classmates.

“We would love for students to recognize burnout in themselves and reach out for help, but it’s not always easy,” Bonsu said. “If they are stuck in a down place, in a bad place and just emotionally really low, reaching out for help seems like the hardest thing to do. So students can send an email or find my QR code right outside my office and hop on my schedule. Students can come and see Ms. Rosenbloom if it’s an academic burnout situation. Sometimes it’s helpful if a friend notices it and offers to go to the wellness center with (a student). Be the one who doesn’t make a joke about it. Reach out and nudge your friend to come talk to us. We’ll check in with them, and you’ll stay anonymous.”

The chronic exhaustion is a burden upon those who are affected by it, but community involvement and reinforcement, as well help from the Wellness office, provide cushions and aid that can support students past the barriers of burnout and back to full form.

MONEY PROBLEMS

Financial issues are baggage several students carry, forcing those that do to balance school, scholarships and sacrifice.

BY ANDREW YE

A wallet containing just enough money for weekly groceries with no excess money for luxuries.

It’s in these quiet evening hours, when his classmates might be scrolling through social media or watching Netflix, that the senior Benjamin Hernandez carves out hours to work on something most people don’t think about: filling out applications, researching deadlines, and, his least favorite part, writing essays that might make college actually affordable.

The numbers tell one version of his story. Out of St. Mark’s roughly $40,000 annual senior tuition, financial aid covers about $38,000 for Hernandez and his mother.

He lives in a single-parent household, and while they’re not, “to put it bluntly, like dirt poor, (they’re) also not completely free to do whatever (they) want,” Hernandez said. “I know we’re in a different place financially than a lot of other people.”

What his classmates don’t see is the filter that runs constantly in the background of every decision, every choice, every college he considers: What’s this really going to cost us?

When summer arrived, Hernandez spent his summer making pottery, piece by piece, building inventory.

Now, months later, he’s finally listing those ceramic pieces online, hoping they’ll sell and give him some personal spending money, the kind that doesn’t come with guilt attached.

“It’s not some big, fancy business or anything,” Hernandez said, “but it’s what I could do when I didn’t get hired anywhere else.”

But along with bringing in a few dollars manually, there are also tons of opportunities to get grants online. The biggest scholarship application on Hernandez’s radar is the Jack Kent Cooke, one of the most prestigious and competitive awards available to high school seniors.

“I’m not exactly the biggest fan of writing those types of responses,” Hernandez said. “But if it can make paying for college easier and lighten the burden, then I’m willing to at least give it a shot.”

He’s hunting for smaller ones too, a few hundred dollars here, a few hundred there,

most with deadlines stacking up in January and February. Each typically requires one or two essays, which he describes with characteristic understatement as something that “kind of sucks.”

He’s applied to two or three so far. By the end of the school year, he estimates he’ll have completed at least 10, more if he can find ones that don’t require essays. The exact number depends on what’s out there and how much time he can dedicate to everything else.

One of the biggest issues, Hernandez says, is something people don’t see: how conscious he is about spending money.

Music is a huge part of his life. He collects records, vinyl from metal bands like Acid King and Acid Bath, atmospheric artists, and widely-known albums like Radiohead.

And naturally there will always be more he wants, like band merch, new releases, and additions to his collection.

But he hasn’t bought anything in months.

“I don’t exactly have that much to spend in the first place,” Hernandez said. “So, I have to be really careful with what I do with my money.”

It’s a cycle he knows well. He sees something he really wants. He tells himself no. Then he reminds himself that it’s all “novelty stuff,” not something he needs to survive.

“It doesn’t put this complete strain on my emotional state, but it’s definitely this little background pressure that doesn’t really show on the surface,” Hernandez said.

Hernandez doesn’t think about the financial aid every single day. But when he does, the feeling hits hard.

“It really bolsters my opinion of the school as a whole,” Hernandez said. “I already had a pretty high opinion of it because of the academics and how everything functions here, but seeing what they do on the more logistical side, like covering almost all of my tuition, makes me re-

ally appreciate the school even more.”

And the financial support Hernandez receives doesn’t just make him grateful, it makes him determined.

He thinks about what the school has invested in him, what his mother has sacrificed for him, and he feels a weight that’s different from pressure. It’s purpose.

“I really just want to make that worth it,” Hernandez said. “I don’t want this incredible opportunity to just be in vain. I want my time here to actually mean something. That I work hard, I take advantage of what’s here, and then I’m able to go to college, get a good profession, and make something good out of my life overall.”

Long after his classmates have closed their laptops for the night, Hernandez is still at his computer, quietly working toward a future he’s determined to earn.

“

It’s

really easy to just get used to things and stop appreciating them, but you shouldn’t.

- Benjamin Hernandez, senior

It’s that motivation that keeps him going on those late evenings, toggling between scholarship applications when he’d rather be doing “literally anything else.”

If people are going out of their way to support him, he wants to show them it wasn’t a waste.

If there’s one thing Hernandez wants people to take away from his experience, it’s simple: “It’s really easy to just get used to things and stop appreciating them, but you shouldn’t,” Hernandez said. “And especially, don’t forget what your parents have done for you. They’re usually the ones sacrificing behind the scenes, so just remember that and appreciate them.”

TBROKEN ARM

The pressure to perform shortens an athlete’s return-to-play, risking recovery and long-term health.

BY BENJAMIN YI

errence Cao doesn’t know what to think. How to act. How to respond. Months of hard work through practices out in the hot Texas heat and the grueling Dilworth workouts, gone in an instant.

The pain is unlike anything he’s ever experienced. It’s not just the physical; it’s the mental, that kills him inside.

His training unravels. He’s once again going down the long, unpredictable path of recovery, just for the hope that he might ever play football again.

It’s just like the start of any normal day. It’s another Wednesday. Cao goes to school, hangs out with his friends and goes to the Zierk Athletic Center. He’s suiting up for football practice once again. It’s a one on one pass rush. Cao attempts a spin move. He’s hit from the side. Another player trips and falls down on top of him. Coaches and teammates rush to help. Rumors start spreading that the bone is sticking out of his arm.

“My first reaction (was) that I knew something was wrong, but it didn’t hurt at all. So I kind of felt my elbow. I’m like, that’s not supposed to happen,” Cao said.

Cao dislocated his elbow. It’s swollen. He can’t move his arm. There’s possible nerve or blood vessel damage. Recovery will take

JUST A “

about six to 12 weeks before his arm can go back to normal use and about three to four months for a full athletic return.

“Trainer Matt (came) over and he did a really great job keeping my arms stabilized (while) waiting for the paramedics,” Cao said.

The ambulance gives Cao some pain medication and then takes him out to a hospital.

“Specific to return to play, number one decisions are, ultimately, guided by whoever the treating physician is. So we just carry those orders out and communicate those to the coaches and teachers if need be,” athletic trainer Matt Hjertstedt said. “The second level is they have to be able to be functional as well, making sure they’re reconditioned with Coach Dilworth, and then that they have an opportunity to practice and get themselves reacclimated to whatever sport they’re in.”

None of Cao’s bones are broken.

It’s a quick procedure to pop his elbow back in place. Cao gets home late at night.

He hasn’t done any of his homework. He still feels weird from the painkillers.

“If (an athlete) out for six weeks, you can’t just take practice one time in a football practice and then throw them back

in. That ends up being a recipe for disaster,” Hjertstedt said.

This isn’t Cao’s first time either. During a JV game against Greenhill his freshman year, he hurt his wrist.

After being sidelined for two weeks and playing the last few games of the season, the injury came back.

“I went to some out of school tennis training and preseason, and one practice my wrist just gave out,” Cao said. “I saw the doctor, and it turned out that my scaphoid broke completely, and blood flow was getting cut off, so a part of the bone was dying,”

Cao was faced with a decision. If his wrist was left untreated, he’d have arthritis by 25. Cao was ultimately left with two choices. Go into surgery, where the doctors would insert a metal rod into his wrist, which would cost Cao about six months of recovery, or wait with a cast. If after nine months it wasn’t fully healed, the doctors would have to take a part of his hip to graft it to his scaphoid.

“I chose the option of having surgery on it early on so the recovery process wasn’t as brutal. I was in a splint for around three months, and then during that time, did some physical therapy and got back to playing sports,” Cao said.

But now, after two injuries, Cao’s parents

My parents’ first reaction was ‘you’re never playing football again.’ This sport is very contact heavy, and they were scared I was going to re-injure myself.

- Terrence Cao, sophomore

DAY HR. MIN. SEC.

are doubtful of continuing his journey in football.

“But my parents were very supportive during the treatment process,” Tao said. “They will always go above and beyond with physical therapy plans or doctor appointments. They’re trying to do as much as they can tell me faster and at the end, they said that it was up to me if I wanted to continue.”

After approximately two weeks, Cao had regained his full range of motion in his arm with minimal pain.

After another two weeks of

weight training he was back on the field with a brace.

“Especially with my teammates, everybody was very supportive and they were always asking, ‘do you need me to carry your backpack?’

Or ‘Is there anything I can get for you?’” Cao said. “And them I remember last year, during the current season, pre-season, the entire team would be very welcoming whenever I came to watch practice or take photos for a match. So overall, the interactions with my classmates and teammates have been very good.”

PHOTO ILLUSTRATION ANDREW YE, EMILIANO MAYO MEJÍA

Sophomore Terrence Cao sits in the recovery room resting his injury, a countdown showing how long it will take for him to get back on the field.

Balancing visibility with behind-the-scenes preparation, the security team relies on expertise and coordination to keep campus safe around the clock.

BY RONIT KONGARA, RISHIK KAPOOR, ANDREW YE

14 FOCUS 12.12.2025

PHOTO KAYDEN ZHONG

HIGH RISK HAND AT

Parked every morning by Nearburg during carpool, waiting on the sidelines during football games, and stationed around every corner of campus, the security team is a familiar part of daily life here. The officers’ friendly greetings and cheerful demeanors are a constant presence on campus, but backing up each smile is a vigilant officer that is ready to respond to whatever dangers may present themselves.

Most security team members are experienced former Dallas police officers who bring decades of knowledge and skills from their previous job into their roles here. This background in public safety allows them to take a less stressful role while still ensuring that students, faculty, and families are as safe as possible.

Many of the security officers are retired police officers who served in law enforcement for 25-30 years.

“We wanted to keep working, but we wanted to get off the streets with police work,” campus safety officer Brian Feinstein said.

To complement this prior experience, security team members undergo a long training program upon joining St. Mark’s, preparing them for the unique responsibilities that come with working at a school. Security officers must also participate in annual training on marksmanship, tactics and other skills over the summer to maintain their skills if any dangerous situation occurs. This training ensures the security team is prepared to handle everything from routine safety procedures to emergency

situations.

The training covers policies and practices for keeping students, visitors and parents safe, with a handbook outlining staff expectations. The sessions ensure officers stay current and prepared for any situations that might arise on campus.

The school employs a rotating system of guards so that the team can maintain consistent coverage of the campus at any given point during the day. Each officer works certain shifts so that there are always members of the personnel on campus 24/7.

“We’ve got a large team, but we’ll usually have four to five people on campus at any given time,” Feinstein said. “Sometimes we’ll have more personnel for special events like a home football game or an open house. You might not see them all at the same place, there might be somebody back in the back alley or in the office but we have a number to keep while the students are on campus.”

At any given moment, the security officers on campus have to stay in close contact with each other. The security officers are always on a constant alert, and each team member has perfected different skills to ensure that everybody on campus is as safe as possible.

The team monitors numerous cameras throughout campus, with one officer constantly watching feeds from the stadium, Lower School, the Quad, the courtyard and Winn Science Center.

“It’s just the fact that we have so many of us working

If there’s an event or someone drives on campus that we don’t recognize, or if it’s a delivery, we communicate with each other.

- Brian Feinstein, campus safety officer “

overseas. According to security team member Jerry Girdler, in order to prepare for international trips, the security team researches and identifies potential risks associated with the destination of the trip and the specific situation. Risks such as political stability, ease of travel and access, as well as considerations such as the purpose of the trip and the itinerary, need to be assessed when creating a plan. When the Chinese program took students to Taiwan over the summer, the security team did the research and created a schedule to ensure the students and teachers would remain safe.

“Mr. Hoffer, (the Associate Director of Campus Safety and Security) performed pre-trip research on the Taiwan trip to prepare him for this trip,” Girdler said. “Some of his information collection was accomplished through OSAC (Overseas Security and Advisory Council) which is sponsored by the State Department. Additionally, he maintained a list of contacts for the U. S. Embassy and other support functions. He was also prepared to provide initial medical treatment in case a student was injured during the trip.”

Though the presence of security officers is visible on campus every day, ensuring safety, a lot of work also goes on behind the scenes to guarantee that the security team is at its highest level to serve the school and community.

ALL

FOR THE KIDS

Nancy Marmion has dedicated 41 years to teaching Spanish at St. Mark’s. Even while caring for her husband through dementia and after his passing, she found purpose and healing in the classroom

BY CHRISTOPHER HUANG AND RONIT KONGARA

Challenges in personal life are difficult for everyone. For a teacher, it may be even more difficult to come to school every day with a smile on their face and to keep teaching when other things are on their mind. As for many of the students, they may be completely oblivious to what difficulties their teachers are facing in their personal lives.

Ever since she was a child, Nancy Marmion has loved teaching. As she grew up, she also considered other careers to pursue. However, though younger, naive notions often may not translate to adult life, she eventually landed on right back on teaching – specifically, teaching Spanish. It is now Marmion’s 41st year at St. Mark’s after joining in 1985, and she currently teaches Upper School Spanish and serves as the school’s J.J. Connolly Master Teaching Chair.

“I really fell in love with Spanish, and I wanted to share that love of Spanish with other people,” Marmion said. “So I think that those two things combined–it’s just sort of what I’m called to do.”

Unfortunately, earlier this year, on March 29, Marmion’s husband, Bill Marmion, passed away after a long battle with dementia. He was a long-time teacher at St. Mark’s, serving in various roles, including as Chair of the History and Social Sciences department.

After his passing, the community joined together to support Marmion and her fami-

ly, helping her through the difficult times. Throughout his struggle with dementia, the community had been very supportive as well.

“The support and the love I felt from (the community) meant so, so very much … the school was a tremendous support through all of that leading up to when he died, and then afterwards,” Marmion said.

During her husband’s battle with dementia, Marmion continued to teach, balancing her work with having to manage the demands of her personal life. When he was first diagnosed, Marmion’s husband didn’t need much care, with his symptoms not really affecting his daily life. But, as time went on, his condition worsened, eventually leading to a moment where Marmion realized her husband could not be home alone anymore.

“There was a day here at school when I got a call from the Dallas police that someone had found him. He was lost, he was disoriented, and they had taken him

“

to the police station. So that was sort of a real wake-up call. Here I am at school, and all of a sudden, my husband’s at the police station, and I have to go pick him up,” Marmion said.

After the pandemic, her husband’s condition continued to worsen, and balancing her work with taking care of her husband became more and more difficult.

“I would get phone calls here at school, and I would be trying to convince him to either get out of bed or take his shower, or get in the car with the caregiver. And there were a couple of times when I had to go home to make sure he would do that. And so then, at some point, it got to the point where I wasn’t able to sleep at night,” Marmion said. “There were also times when he was in the hospital, and I was running back and forth between school and the hospital.”

Teaching is already a very difficult job, but having to manage personal life concerns involving her husband was even more challenging, as Marmion had to find a way to

It’s been very helpful to be able to come to school and focus on my students, focus on the subject matter, which is something I love, and being able to share that with the students.

- Nancy Marmion, J.J. Connolly Master Teaching Chair

handle all of her students and make time for her husband.

“Things were super hard because trying to balance the pull of wanting to take care of him and wanting to do right by my students was really challenging,” Marmion said.

Though it was difficult for Marmion, she had always loved teaching, and being able to do what she loved, along with the community support, helped lighten the burden on her shoulders.

“It had been a really long journey with my husband, because he had dementia, and so there had been a lot of stress for a long time, but being in the classroom really allowed me to focus on something other than all the other stuff that was going on in my life,” Marmion said.

Teaching gave Marmion a way to focus on and pour her energy

into something else during that difficult period, a tactic that has helped her many times in the past. By dedicating her time to teaching, her students, her advisees, and her fellow faculty members, Marmion was able to fill the void left after her husband’s death.

“It gives you things you have to focus on. It’s been very helpful to be able to come to school and focus on my students, focus on the subject matter, which is something I love, and being able to share that with the students, which is also something I love, and trying to do it in the best possible way,” Marmion said. “This school can pretty much fill up your day and your night, right? So between my teaching, trying to go support my advisees and students at their games and performances, and spending time with fellow faculty members,

all of those things fill a huge void.”

Even though many students may not be able to tell when their teachers are facing challenges in their personal lives, or if the teachers are unwilling to share, Marmion believes that it is still important to be kind to everyone, because no one can know what is going on in another person’s personal life outside of school.

“I do think it’s important that people remember that we don’t always know everything that’s going on in somebody’s life, and it’s really easy to reach a judgment quickly without having all the facts,” Marmion said. “And I think that we need to give grace to other people and realize that we don’t always know everything that’s going on.”

PHOTO ILLUSTRATION RONIT KONGARA, ANDREW YE

Nancy Marmion continued to teach after her husband’s death in March, finding it to fill the void left behind by her husband’s passing

WILL THEY

GET HURT ?

Behind-the-scenes safety work by science teachers protects students during labs involving chemicals and complex equipment.

BY WYATT AUER AND EMILIANO MAYO MEJIA

During sophomore and junior year, stu dents have the opportunity to work with multiple chemicals in their chemistry class. However, that opportunity comes with real risk if students and teachers aren’t careful.

To ensure safety for his students, chemistry teacher Ken Owens’ very first test of the year isn’t about stoichiometry or atomic structure — it’s about safety. The test covers safety rules in the laboratory and where certain chemicals and items are located in the class room.

“You have to know that you all have a draw er and a cabinet of gear that I teach you how to use, and you are mostly limited to that gear,” Ow ens said. “So you get more familiar with it as the year goes by and you’re safer with it.”

Although the test is meant to help students react to any sort of accident, it also helps both the stu dents and the teacher prevent accidents before they happen.

“Part of the attitude you need to have is to think ahead,” Owens said. “You may not remember ev erything on that first safety test, but in the room, somebody does and as long as we are looking out for each other, then you can help each other out.”

On lab days, that mindset shows up in the way Owens prepares his students. Before anyone even touches a ring stand or a beaker, classes move through pre-lab instructions and, when needed, safety videos or demonstrations.

“On the rare occasions where there is special equipment, I will teach you how to use that,” Owens said. “We reduce the amount of chemical you use in a lot of the labs so that there’s less chance for spillage and less chance for a major spill.”

Working with smaller quantities is one of the department’s most important protections.

Owens knows teenagers will sometimes make mistakes, so he designs labs so that mistakes don’t turn into emergencies.

“This is why we work with small amounts of stuff, so that if there is a spill, maybe you get something on your hand and we can wash it off,” Owens said. “The times when you work with a little more, I have to teach you how to do that, and I have to watch you more closely. If we ever get to the point where students cannot be trusted with that sort of lab, then we won’t do it anymore.”

However, safety goes far beyond helping students get ready for a single lab period. Teachers also have to organize all their equipment and carefully order and store chemicals, many of which can be dangerous if they aren’t managed correctly.

“The chemicals are organized in a way that if something on a higher shelf leaks, there will not be a dangerous reaction with anything below it,” Owens said. “We separate the acids and the flammable liquids from everything else and we keep the really flammable stuff in the refrigerator so you have less vapor.”

Storing chemicals is a crucial part of maintaining safety in the lab. With so many different chemicals that react in different ways, checklists and routines help teachers maintain organization and keep track of aging or unstable materials.

“Every five years, I go through every single bottle in that room and I check them all,” Owens said. “I replace what needs replacing, I throw out what needs being thrown out and I don’t keep anything in that room that is not shelf stable.”

Down the hall, in the biology and DNA science labs, the work of keeping students safe looks a little different — but it’s just as constant.

Besides preparing lessons, biology teachers spend hours setting up labs, taking them down and cleaning up the mess students leave behind.

That means loading and unloading dish washers full of glassware, wiping benches and monitoring any bacteria cultures growing in the back of the room.

“As far as bacteria, it’s just a matter of especially for the DNA science, they wipe their lab benches down with a bleach solution before and after the lab,” AP Biology and DNA science teacher Mark Adame said. “When we do work with bacteria, we always wear gloves, wash your hands all the time. A lot of wiping stuff down with ei ther ethanol or bleach.”

If something breaks, teachers have to react quickly to prevent cuts or contamination.

“If anything breaks, we have this glass disposal box that’s made for that,” Adame said. “If it’s glass, I’ll just go and clean it up right away. I don’t really let it sit around.”

Behind the scenes, the department also follows strict procedures to dispose of anything that could be biohazardous. Bright red biohazard bags, an autoclave and clear separation between regular trash and lab waste all play a role in protecting students and custodial staff.

said. “I’m always looking around the lab to see if everything’s in its place, that there are no tripping hazards or anything to bump into.”

Even safety reminders come from experience. After a student once grabbed a hot iron ring and burned his hand, Owens added a new warning to his pre-lab routine.

“It was just red and blistered. It wasn’t permanent,” Owens said. “But now I have to tell everybody, every time, be careful about that. You have to be proactive. You have to be in front of it, because preventing an accident is much, much better than dealing with an acci-

Both in chemistry and biology, teachers say they balance giving students freedom to explore with maintaining strict boundaries

That often means pushing goggles, aprons and gloves even when students complain, or choosing labs that accomplish the same learning with safer materials.

“A lot of schools will stick with vinegar and baking soda,” Owens said. “Here we want you to see more that requires a higher regimen of safety so that you can do it with minimal risk.”

What students often don’t see is the time commitment behind that “minimal risk” — teachers coming in early, staying late and con-

“It’s just what you do. It’s just second nature,” Adame said. “Sometimes you come early to take care of it or get home a little bit later. It all de-

From reorganizing shelves of chemicals every five years to bleaching counters after DNA labs, the science department’s safety work rarely shows up in a

But it’s what allows students to ignite burners, handle acids and culture bacteria without fear of serious accidents.

But not all safety work involves chemicals or bacteria. Sometimes, the most important risk is as simple as a slick floor or a poorly placed piece of equipment.

“If the floor is wet, I’ll wipe it up quick, because these floors can be so slick when they’re wet,” Adame

As Owens sees it, that trust between teacher and student is what makes the whole system work.

“Between me telling you what to do in an emergency, and you guys, between each other, being able to help each other out, we should have it covered,” Owens said.

RUNNING ON EMPTY

PHOTO ILLUSTRATION KAYDEN ZHONG

BY KIRAN PARIKH

After an exhausted commute to 7 a.m. practice ended with a tow truck and hours on the shoulder of Preston and 635, senior Ailesh Sadruddin began to see how strict tardy policies, leadership pressure and heavy homework loads can push students to treat safety as optional.

being late.

thing. I can’t just say I’m gonna miss today because I’m too tired to drive there — even

“

If you know you’re going to have a late night and an early morning, you have to plan for it… do whatever it takes to actually be awake before you start driving.

- Ailesh Sadruddin, senior

tween Preston Road and 635. Even more, the crash left Sadrud din with more than just a damaged car. It left a lesson he couldn’t ig nore. He started rethinking his mornings, his nights, the small choices he had been making for years.

GRAPHIC KIRAN PARIKH

FRIENDLY COMPETITION

Peer pressure can push students to collaborate, study harder, and support each other, but that same competitive instinct can escalate into putting oneself in excessively stressful environments.

BY WYATT AUER AND NICHOLAS HUANG

In a way, academic peer pressure can be more nuanced than the typical form of peer pressure. Most of the time, academic peer pressure acts as a motivator to improve grades and bolster extracurricular activities, but it can also create unhealthy competition between peers.

“For example, if more people are pressured to do more community service hours against their friends in hopes of getting some recognition, or getting into college, ultimately, that serves the community in some way,” junior Nathan Tan said. “And so if there is competition, you know, it’s just like the free market. But I would say, internally, it might cause some conflict.”

Students also tend to feel held back by pressures to attend social events or spend less time on academics. In particular, there’s this fear of missing out on opportunities to spend time with friends.

“There’s definitely some pressure when it’s after school and you have nothing going on, you would rather hang out with your friends,” Tan said. “But I would say, in general, people recognize that at St. Mark’s we have a rigorous course load, and people are understanding of that.”

With an understanding community of peers, academic peer pressures can serve as a net positive, especially when encouraging others to focus and

study during free periods.

“Academically, that kind of pressure to do readings and work like that in the morning exists,” Tan said. “I mean, I would also say to some extent, trying to do better on tests than each other can definitely go too far, but it’s generally a good pressure.”

For example, in Tan’s sophomore year, he took Precalculus Honors, a difficult class taught by Dr. Zuming Feng, Suzanne and Patrick McGee Family Master Teaching Chair in Mathematics. In order to succeed in the class, he and his peers set up a group chat, where they would regularly exchange notes and encourage each other.

Even in class, students would collaborate to write up homework assignments on the whiteboard, where they competed to see who would solve the more difficult problems.

“When you put up problems on the board in Dr. Feng’s class, there’s a friendly pressure to put up the harder problems,” Tan said. “And in order to put up those hard problems, you have to do the homework and do the work. And I would say that’s a friendly, low risk pressure that ultimately helps the students in the class.”

For some students, that same competitive energy shows up outside academics, particularly in trading communities online, where profit screenshots and fast gains can amplify pressure.

In fast-moving online markets, the first “win” often becomes the story students tell themselves about what’s possible. Stevens remembers the exact ticker and the feeling, a moment when speed and volatility felt like opportunity rather than risk.

“My first win day trading, I remember it was a call option on SPX, which is the more volatile version of the S&P 500,” junior Walker Stevens said. “I made about $120 in a minute, and that instant surge of dopamine was surreal. That’s what got me hooked.”

The learning curve arrived just as quickly, reshaping that early euphoria into caution.

As prices snapped back, he realized that the market that rewards speed also punishes hesitation and failures just as quickly, and skill, not luck, determines staying power.

“I definitely knew it was risky,” Stevens said. “After I

traded more, I ended up losing the 120 I initially made. I learned how quickly it could swing the other way. It felt like a challenge, though. It’s not just a game—there are strategies you can use to have a positive win rate.”

For many teens, the on-ramp isn’t a finance class, it’s social media promising freedom and flexible hours. The narrative is seductive: make quick gains early in the day, then coast the rest of the day.

“Yeah, I’d say TikTok got me into day trading,” he said. “You see people showing how much they made in a day and the freedom—trade a couple hours in the morning and the rest of the day is free.”

Once inside those communities, the incentives shift from learning to leaderboard climbing. profits become benchmarks, and progress feels public even when the risks are private.

“You’ll see people posting their profits,” Stevens said. “I’m like, ‘I want to get to that next bar.’ You’re always in competition with those people.”

The emotional swing can be as volatile as the price action.

Stevens describes the hyper-vigilance that comes with watching every candlestick, an indicator of an asset’s price movement, a feedback loop of adrenaline, fear, and second-guessing that lingers long after the trade.

“When I was day trading, I felt a lot of stress and excitement—and regret at the same time,” he said. “If a candle dropped a tiny bit, I’d freak out. When I won, I was excited; when I lost, I felt a deep sense of regret and started overthinking, wondering ‘Where’s my next win going to come from?’”

Experience nudged him toward a slower tempo. Swing trades which take place over a long time frame, reward preparation over impulse and analysis of value over noise and hype, aligning better with school and life.

“Nowadays I don’t really day trade,” Stevens said. “It’s more swing trading. It’s a lot more strategic. Day trading is so volatile—hour-by-hour events can wreck a plan. With swing trading, you’re looking at the company’s outlook and data. Day trading is more like reading candles and trying to predict a quick swing.”

BY JAY PANTA AND NOLAN DRIESSE

It starts with an innocent scroll. A few minutes between homework assignments, a quick view of Snapchat or some reels before bed. But within seconds, the algorithm pulls you into a spiral: photos of friends at a concert; a party you weren’t invited to; a group dinner without you. Your chest tightens, and that familiar thought creeps in: Why wasn’t I there?

FOMO, or “fear of missing out,” becomes a familiar feeling and is almost inescapable in the average teenage life.

“We used to come home from school and just be home, we didn’t know what other people were doing,” Director of the Marksman Wellness Center Dr. Gabriela Reed said. “It was really peaceful in a lot of ways, because you could actually separate school and home, in a healthy kind of way.”

But in a world dominated by social media, that so-called “separation” barely exists. Students can track their peers’ every move without them knowing. They know where each other are, what they are doing and who they are with.

“At this point, unless you purposefully tether yourself away from it, it’s really easy to get pulled in,” Reed said.

The constant comparison and awareness of what others are doing is what gives FOMO its power. It’s not just about missing an event; it’s about feeling excluded, unseen and disconnected in an age where connection is everything.

“Any time where you can actually look and see your four best friends are all together, you’re like, ‘What the heck?’ ‘I didn’t get invited.’ ‘What’s the deal?’” Reed said.

These arising questions send students into a rabbit hole of mental health and obsession, causing their lives to circulate around social media and FOMO.

For many, the sting of not being included comes from Snapchat, a platform uniquely built around knowing where everyone else is. Reed particularly considers the Snapchat maps feature — often referred to as the “SnapMap” — one of the most, if not the most, detrimental to a teenager’s mental health. Being able to view the locations as well as stories of others with just a simple click is, simply put, a recipe for FOMO.

Algorithms shape emotionsand curated feeds distort reality. For today’s teens, social media is a big driving force in creating a feeling of FOMO.

even text, or talk over iMessage, or call, or anything.”

“Most people don’t think about group chat as social media, but it kind of is in a lot of ways,” Reed said.

For sophomore Sam Keon, the best solution has been to opt out entirely. Currently, he aims to carry out a full social media detox, letting go of all possible online engagement — with the exception of messages.

While that decision has helped him focus, it’s not without drawbacks.

“I think, especially Snapchat, could definitely lead to (FOMO),” Keon said. “I personally do not have Snapchat, and it’s almost like I’m missing out on a lot of things, because sometimes people don’t

Even beyond public social media feeds, the problem seeps into private spaces. Group chats, for instance, can create their own systems of exclusion.

Still, Keon believes that disconnection can be healthy, and occasionally, even necessary. Although it’s hard to extract oneself from a social environment these days, solitude is necessary and can be beneficial.

“It’s important to also miss out on certain things if you want to focus on yourself,” he said. “If you’re constantly prioritizing making new relationships over the ones you’ve already formed, then that’s really a sacrifice.”

Keon, who recently missed out on the school’s Homecoming 2025 event due to a preexisting conflict, used his prior experiences with abstinence from social media to shift the situation’s narrative into a new light. Rather than falling into the lure of

FOMO, he instead accepted the situation for what it was and, thereby, successfully overcame the seemingly impossible challenge of escaping FOMO.

“I think what really helps me, and what would help other people, is really just being secure and knowing I miss this for a reason,” he said. “There’s nothing I could have done about it: I’m sure I missed out, but it was unavoidable. So it’s not really missing out.”

That kind of perspective is rare in a culture built around constant comparison. Reed notes that social media platforms are designed to keep users engaged.

Behind every “like,” “view,” and “share” is a hit of dopamine, a biological incentive that keeps users refreshing their screens.

“They’ve basically monetized our eye-

balls,” Reed said.

And what those eyeballs see isn’t reality.

“Unfortunately, what’s on social media is curated. So it’s basically like a museum — we only see the best of everyone else,” Reed said. “People sort of assume people’s lives are better than theirs, and they generally assume that what they see is real.”

The irony, of course, is that many of those “perfect” moments are staged. Post captions, for instance, are often not a true reflection of what truly happens. A person’s comment, as another example, might not express their true feelings. And, of course, the post itself often does not paint the full picture.

“Unfortunately, social media is kind of a place to show off,” Reed said. “That’s why people don’t post pictures of them-

selves picking up trash, they post pictures of themselves on a catamaran.”

Reed pointed to the social app BeReal, which tried to counter the artificiality of curated posts by prompting users to share real-time photos once a day. Giving users a two-minute window, people using the app couldn’t take their time to make a scene for the photo, but instead showed what they were really doing. While the app’s success was short-lived, it encouraged people to provide real content, not just a smokescreen of their life.

“What ended up happening was, the pictures weren’t glamorous enough. That’s why it died, because it was real life,” Reed said.

Facing the reality of life is a struggle for lots of people when they are seemingly forced to show their best selves and keep their feelings on the inside. That pressure to appear effortlessly happy and socially active can be toxic, particularly in high school, where fitting in still feels like survival.

Since social media has the power to elicit FOMO, users also have the power to change how they use it, making the experience better for themselves and others.

“We can handle it for ourselves by restricting how much we engage in looking, but we can also be thoughtful of other people,” Reed said. “I know it’s fun to be in the crowd, but if we’re thoughtful about people who are not invited, it would make a huge difference.”

That simple yet powerful awareness of how posts, tags, or stories might make others feel could be the first step toward creating a healthier digital environment, one that encourages a sense of togetherness, not isolation.

Keon agrees that self-awareness is key.

“I’d say if (social media) does create fear of missing out for you, then you’re probably on it too much,” he said. “Once you start getting (FOMO), that’s probably a signal: ‘Hey, I should step away from my phone.’”

In the end, managing FOMO isn’t about deleting every app or isolating yourself from your peers; it’s about balance. It’s about knowing when to log off and remembering that most of what is seen online doesn’t accurately reflect reality.

And maybe missing out isn’t a loss, but a choice. It’s up to you.

There are still countless pressures out there. Hidden, impossible to see.

But no matter how difficult they feel, none of them are impossible to face.

When pressure builds, we have choices. We can acknowledge it instead of burying it. We can share it instead of carrying it alone. We can ask for help, and we can offer it.

Sometimes the weight we carry becomes the strength we didn’t know we had. Pressure can crush us, or it can forge us into something stronger.

So when you see someone struggling, or even just standing still, try to lighten their load. You might find it lightens yours too.

It’s up to us to determine how pressure shapes us. Will it destroy us, or propel us forward?

Andrew Ye and Kayden Zhong