LeaveHim Here Aja Lind

TheStory of Jonas Jacobsson The World's GreatestMaleParalympian

Youwon’t become the best by doing whateveryoneelsedoes.

JonasJacobsson

LeaveHim Here

ISBN: 978-91-8097-194-2

AI-generatedtranslation of theoriginal Swedishedition Lämnahonom här,publishedin2021

ISBN 978-91-986022-1-0

Some editorial adjustmentshavebeen made to enhance accessibilityfor an internationalreadership.

This AI-generatedtranslation hasbeenreviewedand correctedat ageneral level. As such,occasional linguisticorgrammatical errors mayremain.

Thank you, Peterand Michele, foryourhelpwith reviewingthe text.

Text:Aja Lind

Coverdesign: AjaLind

Coverphoto:SylviaHerden/private

Publisher: BoD· BooksonDemand, Östermalmstorg 1, 114 42 Stockholm, Sweden,bod@bod.se

Print: LibriPlureosGmbH, Friedensallee273, 22763 Hamburg, Germany

©Aja Lind

Allrights reserved.Nopartofthispublicationmay be reproduced, storedina retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means —electronic,mechanical,photocopying, recording,or otherwise —withoutthe priorwritten permission of theauthor

PROLOGUE

London 2012

This is it.

It’s theParalympics,and JonasJacobsson is in what maybe hisfinal competitionatinternational level, aftera more than thirty-yearcareerasa sports shooter.

In thestandssitshis family:MotherIngrid, Father Gert,and wife Aja. It’s araresight —his parentshaven't seen him competeina Paralympicssince the1980s,and Ajausually doesn'taccompanyJonas to competitions.

That beautifulSeptember morning, when thefamilyleftthe hotel, everyone wasfilledwithanticipation. They looked forwardtoseeingJonas proveonceagain whyheisthe best shooter in theworld.

Inside thefreezingshootingrange,the mood haschanged. Things aren't goingwellfor Jonas. Hisshootingisoff, andthe gold medalseems outofreach.Thisishis ninthParalympic Games— andhehas wonatleast onegoldinevery single one. Will he nowhavetosettlefor twosilvermedals?

Whereisthe spark, thekillerinstinctthathecan usually summon when it really counts?Inthe standing airrifle event, he came close— second place. Butinthe 50-meter prone event, he didn’t even make thepodium.

Thelastevent —and thelastchancefor gold —isinthe so-calledthree-positionmatch.It'sthe marathon of shooting

andJonas’s specialty. Afterthe qualifyinground, whereJonas hadtofight forevery point, he is in second place, trailing Israelishooter DoronShaziri by twofullpoints— abig margin in sports shooting.

Afterthe qualifiers, thetop eightshootersmovetothe finals hall to prepare. In addition to Jonasand Doron, there's China’sChaoDong, Abdullah Sultan Alaryani from theUAE, andfourother strong contenders.

Theaudiencegetsa welcomebreak,and Jonas’sfamilyand friendsgatherfor amomentinthe arena’sdiningarea. The conversation is subdued— things don’tlookpromising for Jonas. Theshootersinthe finalare strong,and if they all performwell, thepoint gapfromthe qualification round may be toolarge to close. ForJonas to have ashot, he’llneedto shoot exceptionallywell— andhopethatDoron makesa mistake.

At thescheduled time,the eightfinalists andthe audience take theirplacesinthe finals hall.The shooters arecalledin onebyone andplacedaccording to theirqualifyingscores.

Doron, thecurrent leader,isassigned lane one, andJonas,in second place, takeslanetwo.Since Doronisright-handedand Jonasisleft-handed,theycan look directly at each otherif they turn slightly.

Thefinal matchbegins. Thereferee givesthe signal,and the firstshotisfired.

Jonashas ashaky start. Hisfirst fewshots arenines,and he losesmoreground. Theannouncer readsout thescoresas they’reupdated,and DoronShaziri remainsatthe topofthe

leaderboard. With eightshots left,Doron hasincreased his lead to threefullpoints. Things look bleakfor Jonas.

On theblue-and-yellow sectionofthe stands,the mood is sombre.Familyand friendsknowJonas won’tbesatisfied leavingthe Gameswithonlytwo silver medals.A miracleis needed forSwedentoclaim awin.

Jonasand Doronhavefaced each othermanytimes before. Doron, nowchasing hisveryfirst Paralympic gold,which puts extrapressure on him. Jonasonthe otherhand, tendsto elevatehis performancewhenitmatters most.IfJonas can somehowshake Doron’sfocus,there mightbea glimmerof hope.But time is running out.

Andthen, somethingchanges.

No oneinthe stands quiteunderstands how— but suddenly it’s there. Jonas’sfightingspirit. With just afew shotsleft, it’s as if everything fallsintoplace.His blue eyes darken with fierce focus, anditseems like he’s entereda trance.One perfectten afteranother.Everythingisclicking now.

Afterseven straight tens,Doron firesa poor shot —and Jonas overtakeshim,now listed as number oneonthe scoreboard. Goingintothe finalshot, Jonasleads by 0.8points. It all comesdowntothe last round.

Doronlines up andshoots. Aseven!Thatshouldnever happen at this level. Awaveofsurprisesweepsthrough the audience.Jonas is readybut hasn’t pulledthe triggeryet.His eyes areonthe target,and he doesn’t seeDoron’s result.He hearsthe audience react— but doesn’tknowwhatitmeans. Wasita badshot? Or areallygoodone?

Jonasfocuses,aims, andfires.Another ten.

Afinal tenthatsecures Jonas’sseventeenth Paralympic gold. He nowhas atotal of thirty Paralympic medals.Withthe victoryinLondon, he becomesthe only athleteinthe world to have wongoldatnineconsecutive Paralympic Games— cementinghis legacy as thegreatestmaleParalympian of all time.

During themedal ceremony,Jonas shakes hishead. It seems even he can’tquite believeit.

Solna, Sweden,1965

‘You don’tneedtoworry.You canleave himhere, andwe’ll make sure someonetakes care of him.’

Ingrid andGertJacobssonhad just received thenewsthat wouldchangetheir livesforever.Their three-month-oldson Jonashad been diagnosedwithparalysis from thewaist down.

Theexamination hadtaken severalhours.Whenthe team of doctorsfinally came outtothe worried parentstoshare their findings,Ingridfainted.Still,the moment sheregained consciousness, sherememberedwhatshe hadjustbeentold. Jonas. Paralysed.

‘There areinstitutionsthatcarefor children like Jonas,’one of thedoctors continued. ‘Mostlikely, he will spendhis life lyingina bed. Leavehim here andgohometoyourother children!’

JonasJacobsson wasborninJune1965. HismotherIngridwas Rh-negative, whichposed ariskofdevelopingantibodiesthat couldcause anaemiainthe foetus.Because of this,her pregnancywas closelymonitored,and shegavebirth at Karolinska Hospital in Solna, just outsidecentral Stockholm, insteadofinNorrköping, wherethe family lived. Therewas greatreliefwheneverythingseemedtogowell, anda healthy-lookingbabyboy wasbornjustbeforeMidsummer.

Butsomething bothered Ingrid.She couldn’t quite put her finger on it,but shefeltthere wassomething oddabout Jonas’slegs. Hisfeetwereatstrange angles,and shecouldn’t shakethe feelingthatsomething wasn’t right.

Weekspassed, andshe occasionally voiced herconcernsto Gert,the childhealthclinic,and others shespoke to.But even though Ingrid wasalready themotheroftwo boys andhad worked as apaediatricnurse,noone took herseriously.Her worries were dismissedasimagination.Typical newmother!

Notuntil Jonaswas threemonthsold wasIngrid’sinstinct confirmed. It wastimefor histhree-month vaccination,and Gert droveIngridand Jonastothe clinic in Norrköping. When theneedlewentintoJonas’s thigh, he didn’t reactatall.Not a blink. Nota cry. Somethingwas definitely wrong, andIngrid’s concerns couldnolongerbedismissed.

Gert andIngridwentstraighttoStockholm with Jonas. Karolinska Hospital hadSweden’sbestpaediatricians, and sinceJonas hadbeenbornthere,theyagreed to examine him.

Theverdict washarsh:Paralysed from thewaist down.Jonas wouldnever walk.Hemight spendhis entire life lyingina bed.

‘Leave himhereand go home to your otherchildren!’

Gert andIngridwerefaced with alife-changing decision. What should they do?Shouldtheylistentothe doctors’ advice andleave Jonasthere,orgoagainst therecommendations?

ForGertand Ingrid,the decision wasn’t difficult. Of course, Jonaswould come home with them.Hewas part of the family,and regardless of hisdisability, he wouldberaisedjust like hisbrothers.

CHAPTER1

Oneofthe OtherKids

Igrewupina yellow brickhouse in Krokek,Kolmården,just outsideNorrköping. From ourhome, it wasabout sevenor eightkilometres to KolmårdenWildlife Park,and roughly halfwaythere,deepinthe forest,was theshootingrange whereI spentmostofmytraininghours.Sometimes,when we were practicing at therange,you couldhearthe lions roaring. Notevery shootercan saythat.

My mother came from Lindö, on theother side of Bråviken — thelonginlet that stretchesfromthe Baltic Seato Norrköping. My father wasfromSkåne in thesouth of Sweden andended up in thecountyofÖstergötlandthrough hiswork. As ayoung man, when he took thetrain from Skåne to Stockholmand passed Bråviken,hethought to himself, ‘That’swhere I’dliketolive.’And so,hedid.Myparents met at adance in Norrköping in 1950. They gotengaged on New Year’s Evein1951and were marriedin1954. My brother Göranwas born in 1955and my otherbrother Ulf, or Uffe as we always call him, in 1962.Three yearslater,I came along.

Mumwas atrained paediatric nurseand worked in Norrköping. When theheadofher workplacefound out aboutmydisabilityand that sheneededtostayhomewith me,she said ‘lucky forhim,thathegot youashis parents.’I agree. Iwas luckytohaveMum andDad as my parents.

My oldest brotherGöran wasa bitofa rebeland movedout when Iwas just five.After spending some time at amaritime

school in Kalmar,hegot ajob on supertankers that travelled theworld.Whenhecamehome, it wasalwaysexciting. He oftenbrought back giftsand flagsfromfar-off countries.

Uffe andI played together alot.Our favouritegamewas cowboysand Indians. We were obsessed with everything to do with theWildWest, andwhenthe TV show Howthe West waswon with TheMacahan Family wasaired,wewereglued to thescreen. BeinganIndianwas themostpopular role.Uffe always wanted to be theIndian, andsince he wasolder and thoughthewas in charge,I always hadtobethe cowboy.

We used smallplastic figurestoact outdifferent scenarios that we made up as we went along. Uffe made theprops.He wasalwaysgood at buildingand creating things andcould turn acardboard boxintoa stable,a boat or ahouse.

We also hada doginthe family.Wehad afew over theyears, but my favouritebyfar wasFia,a Scottish Terrier.I used to put on boxing gloves and‘box’ with her. Sheloved it.Assoon as Iput thegloveson, she’dgowild,but themomentI took them off, sheunderstoodthe game wasoverand wouldcalm down.Fia wastough andbrave,but also very well-behaved at leastwhenwewerewatching. Irememberoncewhenwe were feedinga hedgehog that hadcomeintothe yard.Fia sat next to us watching thehedgehogeat,calmand composed. When we left,she stayed behind.A little later, shecameback inside pretending nothinghad happened —but shehad two hedgehog spines sticking outofher nose.

Most of my childhoodmemoriesare good.I went to the Karolinska Hospital forvarious examsand procedures,but that’s notwhatstandsout when Ilookback. What I remember most areall thedaysspent on thewater.Mum

andDad hada Villiamcruiser —a sailboat just over 8meters long.Wewould head outassoonasthe weatherallowed.We explored thearchipelago of Östergötland,often stopping to go ashore on differentislands andislets. We swam alot.

At thebackofthe boat,Dad hadinstalleda platform.From there, Icould hopintoa dinghy we always towedbehindus. Nowadays,manyboats have asimilar setup, but back then,it wasrare. Iwould rowaroundand explore, goingonmyown little adventures whenever we anchored somewhere. It made me feel free.

Once,I hadtohandoverthe dinghy to Fia. Afterwehad been ashore,she came runningback— coveredinmuckshe had rolled in.Itwas almost impossibletoget herclean,and she smelledawful.Dad puther in thedinghy, andshe rode behind theboatall theway home.Itwas afunny sight— Fia sitting aloneinthe dinghy,stinkingand ashamed.

In thewinters,weoften went skiinginthe skiresortSälen. When Iwas very young,Dad carried me in aseatonhis back. Later, he modified awooden sled that he wouldpullmein. It waslikea toboggan, andhefitteditwitha canopy to keep my legs warm.Sometimes,our friends’ bigBoxer dogwould pull me instead.

Thoseare thekindofmemoriesthatcometomindwhenI thinkback. Ihad averygood childhood.

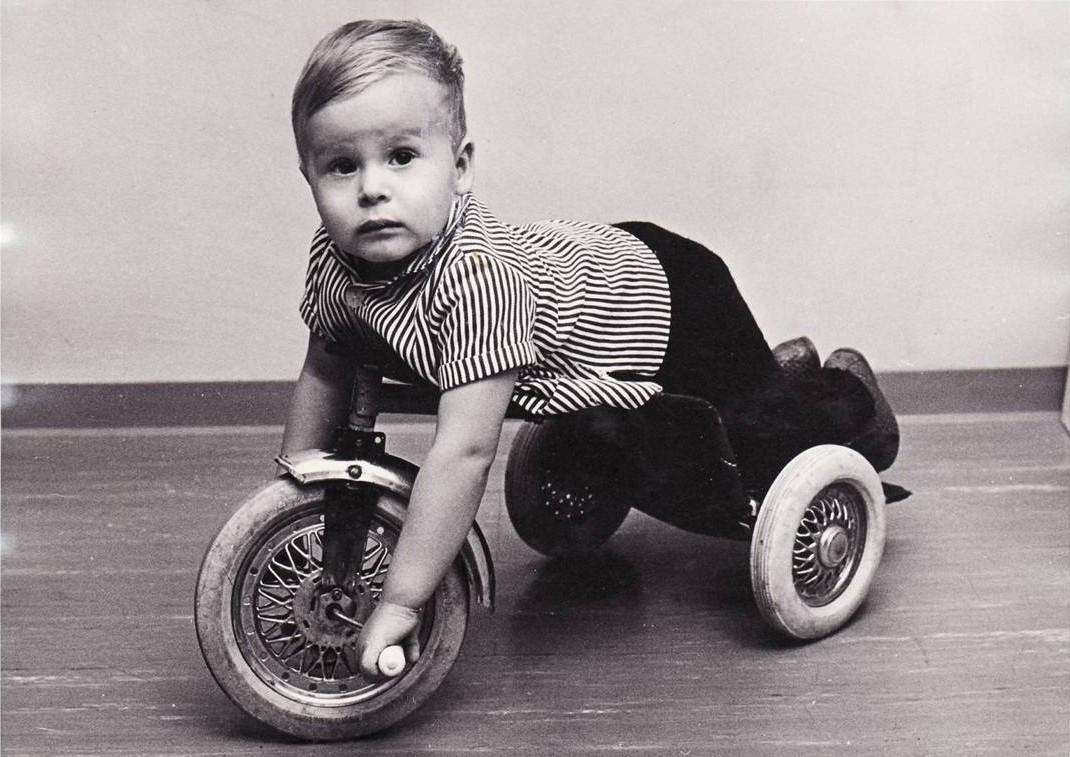

Istarted hangingout with theneighbourhood kids earlyon. When Iwas aboutthree or four,I went to Sundayschoolat theScout Hall in Krokek.I broughtalong my lay-down bike that Dadhad builtfromUffe’sold tricycle.Ithad aplatformI layon, pedallingwithmyarms. Thebikewas fast andlooked

cool,sothe otherkidsalwayswantedtotry it.While they took turns, I’djustsit somewhereand wait formyturntoget it back.

When that bike became toosmall,I hada handcycle. We were givenitfromthe localassistivedevicecentre— or whatever it wascalledbackthen. Irememberfalling backward andhitting my head thefirst time Itried it.Dad was furious! Apparently,the balancewas offfor me.I endedup with aconcussion andhad to rest indoorstorecover.Dad rebuiltthe bike to balanceproperly, andI used it everytimeI went outtoplay. Thewheelchairs availablebackthenwere bigand clunky —not idealwhenyou wanted to be fast and keep up with friends. So firstitwas thelay-downbike, and then thehandcycle.

Themainthing we didasneighbourhood kids wasplaying street hockey.Below ourhouse wasa smallhillthatled down to aplaza whereweusedtogather. Ourkitchen window facedthe plaza, andwhenitwas time fordinner, Mumwould open thewindowand blow awhistle to call me home.

Kids from alloverthe area joined in,and theagesvaried. I sometimesplayeddefence,but mostly Iwas aforward.My jobwas to stay in frontofthe goal andbeready to deflectthe ball in when someonepassedittome.

Sometimes, my school andhomeroutinesblended seamlessly into dailylifewiththe otherneighbourhood kids.Whenit came time forschool, we received anoticefromEkhaga, a boarding school forchildrenwithdisabilities— thesame institutionwhere doctorshad originally thoughtI should live. Theauthorities insisted that it wasthe proper placefor me. Mum, Dadand Iwentthere fora visittoatleast give it a

chance,but Iinstantly disliked it.Maybe it sounds harsh, but I thoughtthe otherkidsthere seemed weird. Iwas used to my friendsinKrokekand didn’t feel comfortablearound allthese unfamiliarchildrenwithdifferent kindsofdisabilitiesI’d never encountered before.I wanted to go to school at home with my friends. Thankfully,myparents agreed.Theytoo believed it wouldbebetterfor me to attend aregular school alongside thekidsI hadgrown up with.

Theirviewonmyeducation wascontroversial.Atthe time,it wasn’t common forchildrenwithdisabilitiestoattendregular schools, so my parentsfaced resistance.Someone from the School Boardcametoevaluateme. They wanted to administer an IQ test to determineifI was‘fit’ to attend a mainstream school.Thatwas thelaststraw forDad.Heasked Mumtoopenthe door,thenessentially threwthe official out, saying,‘None of my othersonshad to take an IQ test,sothis onewon’t either.’

That made me oneofthe firstchildrenwitha disability in the countyofÖstergötlandtoattenda regularschool. My parents knew severalstaff membersatRåsslaskolan, thelocal school, andhad agoodrelationshipwiththe principal, whosaw no issuewithmeattending.Hehad arampbuilt foraccess to the cafeteria, andwhenthe school wasrenovated later, he had an elevator installed.

To andfromschool,I used asmall powerchair.I hadone wheelchair at home andone at school.WhenI gothome, I parked thepower chairinthe garage,hoppedintomymanual chair, andplugged in thepower chairtocharge. At school,I didthe same in adesignatedstorage room forwhich Ihad the key. This meantI couldgotoand from school by myself,just

like theother kids.Theybiked,and Idrove my powerchair. Sometimeswe’draceand pretendwewereina speedway competition.

Iwas luckytoend up in aclass full of kids wholoved sports. We oftenplayedsoccerwitha tennisballduringrecess. The olderkidsusedthe bigfield,sowedidn’tdaregothere.Well, Isometimes hidthere when thegirls were chasingthe boys Iknewnogirls wouldfollowmeout there.

Magnus andAri were thebestathletesinthe class. Iwas pretty good too, but of course,I hadmylimitations.So, we made up specialrules forme. Icould steerthe ball into the goal with my hands, but Iwasn’tallowed to grab or hold it. We kids came up with thoserules ourselves— no adulthad to step in.

Arioften picked me forhis team.Hecould throwthe ball across theentireschoolyard, andI’d be waitingbythe opposing goal to deflectitinwithmyhands.

We even invented ourown game.Itwas aballsport where youhad to throwa tennis ball over abeamundera covered outdoorarea. Thesidepanelsunderthe roof actedlikewalls, so youcould bounce theballoff them andtry to scoreagainst thepersononthe otherside. It could’ve been an official sport —fully thoughtout with rulesand everything.

Most of thetime, we boys played together duringbreaks. We played sports,while thegirls usuallyjumpedrope. I remember in firstorsecondgrade we didplaywiththe girls sometimes. Forsomereason, therewerehay balesbehind theschool, andweplayed‘horse’.The boys were thehorses, andthe girlstookcareofus. Iwas apopular choice —I guess

Iwas both horseand carriage.I’d lieinthe hayand get pampered fora while, then hopintomywheelchairand take aspin. Thegirltakingcareofmecould standonthe footplate and‘drive’ thehorse andcarriage. That wasprobablybeforeI startedhidingfromgirls amongthe olderkids.

Aftera fewyears,our classmoved to anew school, Uttersberg.Now we were theolder ones whoclaimed the real soccer fieldfor ourselves. Almost everyrecess, we played soccer.I wasthe goalkeeper.The problemwas that thearea around theschoolwasn’tquite finished.For instance,the grasshadn’tbeenlaidyet,soinspring, theschoolyard turned into amuddymess. My wheelchair wouldtrack in huge amountsofdirt. That ledthe teachers to banmefromplaying soccer fora fewdaysduringthe worstofit. Iwas nothappy aboutthat.

School gymnastics wasalwaysmyfavourite subject. We kids hadalready figuredout howI couldparticipate in allsorts of activities,and that carried over into gymclass. During equipmentexercises,I’d repeat thestationsI coulddoa few extratimes,and if theclass went outfor orienteering,I always found someonewitha cold to stay behind andplay tabletenniswithinstead.

In middle school,someone gotthe idea that Ishoulddo physicaltherapy during gymclass insteadofjoining the others.I hatedit! No waydid Iwanttomissthe most fun subjectjustsosomeone couldstretch andbendmylegs. It lasted only onesemesterbeforeI refusedtogototherapy andwentbackintoregular gymclass —where Istayeduntil 9thgrade andevenearnedthe highestgrade possible.

People oftenask if Ifeltdifferent as akid,but Ireallydidn’t. I neverfeltthatmyfriends treatedmeany differentlyeither. Most of thekidsinclass hadknown me sincewewerevery young,sotheywereusedtome. Ionlyremembera coupleof momentswhensomething unusualhappened.

Onewas in second grade, when we hadour firstswimming lesson. Dadhad builta pool at ourhouse,soI learnedtoswim early— probably by thetimeI wasfive. By thetimesecond graderolledaround, I’dbeenswimmingfor years. Butthe swim instructor refusedtobelieve it.She didn’t even letme into thepooland said I’dprobablysinklikea stone.

Iwas furious. Ijustwantedtoswim! Eventually,theycalled Mum, whodrove herlittleVWBeetledowntothe pool.She hadtosit thereand watchasI swam back andforth.All the otherkidshad floatation devices, butI swam on my own. Finally, even theinstructorhad to admitI couldswim, and Mumdidn’thavetobethere anymore.

Theother time wasinmiddleschool, when we hada special themeday aboutdisabilities. We watcheda movieabout variousconditionsand what it wasliketouse awheelchair. Suddenly, oneofthe girlsinclass turned around andlooked at me wide-eyed: ‘Whoa! We have oneinour class!’she said —asifithad only just occurred to herthatI used awheelchair. Andhonestly, maybeithad.After shesaidthat, no one really cared. ButI sometimesthink abouthow that moment showed howlittlemydisabilitymatteredtothe people around me.

When the Swedish Paralympic shooterJonas Jacobsson was three months old, doctorsdetermined that he was paralyzed from the waist down. It was likely he would spend his entire life confined to

His parents chose to follow their convictions and defy the doctors' advice. Theytook Jonas home and fought to givehim the conditions

Forty-sevenyears later,theysat in the stands in London and watched Jonas win his 17th Paralympic gold medal. That victory madeJonas Jacobsson the only Paralympian to have won at least one gold medal at nine consecutiveParalympic Games,making him the most successful male Paralympic athlete of all time. He has a bed, and the message to his parents was clear: Leavehim here! he needed to be able to takecare of himself in the future.

total of 30 Paralympic medals and 38 World Championship medals.

LeaveHim Here is Jonas Jacobsson's autobiography, outstanding accomplishments. areflection on his childhood, life, and athletic career, shaped by hardshipand triumph, humour and

The story is filled with humour and moments of laughter.This book is not just for sports enthusiasts, but for anyone seeking inspiration and acaptivating storyabout daringtotakerisks in order to trulywin something.

The book is written by Aja Lind, who has listened to Jonas's stories for over 15 years -and has been part of manyofthem herself.