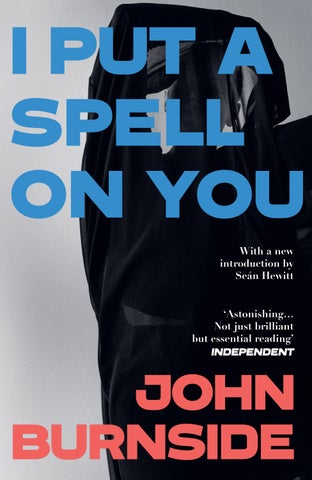

I Put a Spell on you JOHN Burnside

Seán Hewitt

JOHN BURNSIDE

John Burnside was among the most acclaimed writers of his generation. His novels, short stories, poetry and memoirs won numerous awards, including the Geoffrey Faber Memorial, Saltire Scottish Book of the Year and, in 2023, he received the David Cohen Prize for a lifetime’s achievement in literature. In 2011 Black Cat Bone won both the Forward and the T.S. Eliot Prizes for poetry. He died in 2024.

ALSO BY JOHN BURNSIDE

The Hoop

Common Knowledge

Feast Days

The Myth of the Twin

Swimming in the Flood

A Normal Skin

The Asylum Dance

The Light Trap

The Good Neighbour

poetry

Selected Poems

Gift Songs

The Hunt in the Forest

Black Cat Bone

All One Breath

Still Life with Feeding Snake

Learning to Sleep

Ruin, Blossom

The Empire of Forgetting

non-fiction

A Lie About My Father

Waking Up in Toytown

The Music of Time: Poetry in the Twentieth Century

Aurochs and Auks

The Dumb House

The Mercy Boys

Burning Elvis

The Locust Room

Living Nowhere

fiction

The Devil’s Footprints

Glister

A Summer of Drowning

Something Like Happy

Ashland & Vine

JOHN BURNSIDE

I Put a Spell on You

Several Digressions on Love and Glamour

WITH AN INTRODUCTION BY

Seán Hewitt

Vintage is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies

Vintage, Penguin Random House UK, One Embassy Gardens, 8 Viaduct Gardens, London SW11 7BW

penguin.co.uk/vintage global.penguinrandomhouse.com

First published in hardback by Jonathan Cape in 2014 First published in Vintage in 2015 This edition first published in Vintage in 2025

Copyright © John Burnside 2014

The moral right of the author has been asserted

Introduction copyright © Seán Hewitt

Lines from Civilization and its Discontents by Sigmund Freud are reproduced by permission of the Marsh Agency on behalf of Sigmund Freud Copyrights and W.W. Norton.

Lines from ‘Canto LXXXI’ by Ezra Pound, from The Cantos of Ezra Pound, copyright © 1948 by Ezra Pound. Reprinted by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp.

Penguin Random House values and supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes freedom of expression and supports a vibrant culture. Thank you for purchasing an authorised edition of this book and for respecting intellectual property laws by not reproducing, scanning or distributing any part of it by any means without permission. You are supporting authors and enabling Penguin Random House to continue to publish books for everyone. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner for the purpose of training artificial intelligence technologies or systems. In accordance with Article 4(3) of the DSM Directive 2019/790, Penguin Random House expressly reserves this work from the text and data mining exception.

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The authorised representative in the EEA is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin D02 YH68

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 9781529962864

Penguin Random House is committed to a sustainable future for our business, our readers and our planet. This book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper.

i.m. Theresa Burnside

The idea, you know, is that the sentimental person thinks things will last – the romantic person has a desperate confidence that they won’t.

F. Scott Fitzgerald

My love seems to me like a deep, bottomless abyss, into which I subside deeper and deeper. There is nothing now which could save me from it.

Leopold von Sacher-Masoch

Digressions, incontestably, are the sunshine; they are the life, the soul of reading . . .

Laurence Sterne

Seventh Digression: On the Mountains of the Moon

INTRODUCTION

It was mid-January, and the sort of early dusk where the world seems to fizzle out around you, as though you are inside a film and someone is slowly turning down the contrast. When I had set out, there had been a mist enveloping the tops of the trees, but now it had lowered, and the dark had settled in, and everything beyond me, as I walked, had become a species of shadow. The beeches and the oaks at the top of the hill in front of me seemed to reach up into a hidden place overhead, and I became more aware than usual of being so small, so subject to gravity, inhabiting just six feet of all that available air. It has been my habit, for the best part of a decade, to walk along the banks of the River Liffey, or through the woods and fields of the Phoenix Park, once in the morning, and once in the evening. I like to see the deer, moving their shadows between the trees, or to hear them locking their antlers together in late summer during the rut. Sometimes I am bored by the walk, sometimes not. I have hoped, for a long while now, to find a discarded antler, but I never have.

I had thought I was well acquainted with the park, or as well acquainted as one might reasonably hope to be. Perhaps the word ‘park’ is a red herring, where this park is concerned. Once a royal hunting ground, the place is almost as large as Dublin city centre, its high wall enclosing over 1,700 acres of woods, meadows, and

fortifications sitting on hilly outcrops, the spectres of a colonial past. There is a hospital, and the president’s house, and a disused military barracks. Of course, the park changes, as landscapes do, with the passing of the year, but it is, in many ways, the most civilised of landscapes: there are rangers, cars, football pitches, and a zoo. But it is also, particularly at dusk and after dark, to my imagination at least, a remnant of wildness.

This evening, there was something particularly disorientating about the dusk, and the way the fog lowered, casting the headlamps of the cars far ahead of themselves, distorting my perception of distance. I had been listening to a podcast, but I had taken out my earphones, unsettled by the narrowing of my senses as the dark closed in around me. I was up past the Papal Field, walking alongside an oak woodland bisected by a long avenue which, in classic eighteenth-century style, channels a rolling vista of the Wicklow Mountains. I could not see the mountains, nor the field, nor the herd of deer, though I knew each was there, just beyond my vision. I could hear, occasionally, the movement of branches, the rustle of fallen leaves, and I had stopped by the woods because the fog was beautiful, and because the chill of the air seemed rare and fresh and felt good to stand in.

And it was then that I became aware of a noise, just far enough away to be rendered indistinct, though at first I thought it was a person, whooping strangely, out of terror or joy, I could not tell. And then I thought it was an owl, though as it continued I knew that it was not. And then, weirdly enough, I thought it sounded like some sort of primate, because the call was full and loud and had an emotional core, an expression to it, which

seemed to haunt the distance between the human and something primitive, ancestral. It was coming, I thought, from inside the woods. I paused, listening, for so long that for a moment I convinced myself I was imagining it – it did not belong to the world I knew. But then I walked, tentatively, quite afraid by this point, into the trees, and the sound came louder, and had a degree of pain to it which I had not perceived earlier.

The grass was frozen, and the earth was sodden underneath where I broke the ice. Water ran into my shoes, and I could hear the sucking of the mud beneath me, but I carried on, further from the path, as though I was under a spell. My eyes did not adapt quickly to the dark, because the fog had a quality of whiteness to it, and because the shapes of the trees seemed to loom and spread and move as I moved. But, after a time, maybe just a hundred metres or so into the woods, I saw the shadows of deer. I kept walking, despite my fear. Curiosity, or something else, had overtaken me. Some of the deer were shifting, tentatively, nervously, between the oaks, but further ahead was a larger mass, a gathering almost, and I thought they were standing in a circle there, and that that was where the sound was coming from, because the hollow, pained shout was getting louder as I approached.

I wondered if the deer had gathered because they, too, had heard it, and fallen under its enchantment. I was concerned – if I found an injured animal, what would I do? Could I help? I could barely see, and had no signal on my phone, and I knew from experience that injured animals could be vicious. But as I stood there, halted in a state poised between wonder and fear,

a branch snapped beneath my foot, and the deer all suddenly bolted – the full, dark circle scattering through the woods – and the sound, which had seemed so primal, so utterly of another world, immediately stopped.

Why do I tell you this, by way of introducing the book in your hands? For a start, this is a book knotted with brilliant digressions – ‘the sunshine; . . . the life, the soul of reading’, as Laurence Sterne has it in the epigraph – and so beginning somewhere else makes sense. This is a book about so many things that it is hard, in some ways, to say what it is about. But, if I had to make an attempt, I would say that this is a book about mystery and about wildness. I say that because, under the canopy of those words, Burnside places music, love, romance, sex, religion, and almost everything concerned with what it means to be human. I Put a Spell on You accumulates as it moves, turning backwards and then rejoining itself, gathering towards a vision of grace and enchantment. It is not an ordinary memoir: it follows its own glimmering logic. John Burnside’s prose is so precise, so sensory. And because he is as sharp and graceful in the mode of the essay as in the excavation of experience, we feel we are always there beside him, in a room in a pub in Cambridge, a kitchen in Cowdenbeath, a cabin in the isolated arctic north of Norway. But, really, I tell you this because there is something in John Burnside’s writing, his poems and his prose, which has made me feel, over and over again, like I am standing in those woods, on the precipice of a mystery, and because standing there is an exhilaration, both of the nerves and of the mind, which brings me, brings us, closer to the living, enthralled, perilous and, as

Introduction

Burnside would have it, erotic nature of the world. This is a book about falling under the spell of music, under the spell of love. It is also a book whose spell I have fallen under.

I can still remember the places where I have been as I first encountered Burnside’s writings. When I first opened Still Life with Feeding Snake, his 2017 collection of poems, I was in my bedroom in Liverpool, on the ground floor of an old mansion building originally home to wealthy Victorian shipping merchants. The flat was cheap and grand. At that time, I was living on a meagre stipend as part of my PhD, but I was happy. If I was to have no money, I reasoned, I would rather live in a fallen place, a place that gestured to a sort of elegant decrepitude. There were mice in the kitchen. The old sash windows were so draughty that they funnelled cold air across the rooms, slamming the doors. When I left, after three years, for Ireland, I found that the books I had kept on a shelf against the wall were spotted with black mould, and the pages had crinkled with the damp. It gives me a strange sense of companionship to hear of Burnside, in a rented caravan guarded by a Rottweiler, in a backyard in Cambridge, listening to Britten and reading Proust. Anyway, one day, I was working in bed, and I opened Still Life with Feeding Snake at random, and landed on the poem ‘Confiteor’. I did not know what the title meant, or even how to pronounce it, which scuppered, at first, my usual habit of reading poems aloud to myself. Still, I proceeded:

I heard something out by the gate and went to look.

Dead of night; new snow; the larch woods filling slowly, stars beneath the stars.

If I had any sense, I probably stopped there, and started again just to savour those opening lines. Full of intrigue, beauty, an echo of Robert Frost, but darker, rippling with a perceptible fear. Of course, I was hardly in my bedroom at all by that point.

Four lines of a poem, and I was somewhere else entirely.

In I Put a Spell on You, Burnside circles around glamourie, a Scots word that retains the old link between glamour and magic. This is, for him, a moment in which the soul is ‘like a door ajar’, when we experience ‘the physical world immediate and intimate and erotic, invested with new energy and light and, at the same time, beautifully perilous’. If there was a poem that charts that feeling, it is ‘Confiteor’. The poet, like me in the woods in Dublin, hears a sound, and does not know what it is, and by the end of the poem he still does not know, but as he approaches his house again, he is haunted by:

That far cry in the dark behind my back

And deep in the well of my throat

As I live and breathe.

I was struck, and still am, by that final line’s ambiguity. Is the poem as real as life, or as surreal as life? Is that final line an oath, a declaration of the truth of the experience, or something even stranger, a sense of that cry persisting, inhabiting the poet, for as long as he lives, and as long as he breathes? I have not decided. I have chosen, in fact, not to decide. There is a glamourie in the

poem, or a glamourie in reading the poem, which any decision on my part might call into question. In not deciding, I am still there, poised on the cusp of the night, experiencing a sort of beautiful peril. Do I believe in the cry, or in the haunting, or in neither, or in both?

As any writer of a memoir knows, one cannot speak about oneself for very long before someone, somewhere, arrives with the idea that to do so is narcissistic. Who are you, after all? Why do you think your life is worth writing about? And why, really, should I care? I am not sure that Burnside is thinking necessarily about this, but nevertheless, in his digression on Narcissus, he comes up with perhaps the best answer I can think of. His answer gives words to an experience all of us have had, where our sense of smallness in the world is fused, in a state of wonder, to an overwhelming love or, as some might call it, an experience of grace.

In Ovid’s Metamorphoses, Narcissus, as we know, finds himself in the woods, all of his words repeated back to him by the nymph Echo. Narcissus leans over a pool, and sees his own reflection and, so the popular reading goes, falls in love with himself, birthing a handy name for all manner of pop-psychological theories of power, arrogance, selfishness and self-deception. But Burnside thinks otherwise.

In that first glimpse, he loves what he sees; only later does he understand that what he loves is actually himself. He sees himself in the pool, along with all the other things (the sky, the trees, the world all about him), and he finds

this vision beautiful – and this is the cause of his initial delight. Having believed himself to be alone, looking out at a world that was separate from him, he all of a sudden sees that he is in that world. He is as real and mysterious and beautiful as that world is – and yet he is also a separate, potentially knowable being.

This is also why I began this introduction by telling you about hearing that noise in the woods. Burnside’s book, as with all of the very best books, articulates something I had only felt. There was a moment, standing there, listening, when I was under a spell, and it was partly the spell of the world, but it was also, partly, the spell of myself. How lucky was I, how blessed, not only to be a witness to the world, but a part of it?

This book is haunted by the failure of masculinity, the curtailment of wonder and expression. ‘What would real success look like,’ Burnside asks, ‘for a boy who chose not to be that kind of man, but grew at his own pace into the creature he could have been, had his future not been decided for him years ago?’ The word ‘creature’ here is no accident: a reconnection with the wild, with Narcissus’s sense of beauty, is intended.

But, from the title to the final pages, I Put a Spell on You is threaded with the counterbalancing influence of the feminine. From Nina Simone to his cousin Madeleine, who first played him Simone’s music and with whom he was briefly, youthfully, in love; from his mother to the girls he meets in cafes, in pubs, in chance encounters, this is also a book about women, and about men’s hopeless, irrational response to being enchanted by

them. On unrequited love, Burnside is perfect: ‘now I knew different because, now, I was in love, and love felt very odd, like hearing the first few lines of a story I would never read to the end, because the end belonged to somebody else.’

And even when the love is requited, love itself seems often too sacred to put into language, so opportunities are missed, and lovers become ghosts in the memory. Burnside renders these encounters in beautiful chiaroscuro. In one scene, with a Midwestern woman called Christina, the beginning of love is marked out as ‘a perfect piece of cinematography’. Christina, standing in her flat, has ‘the look of a woman in a Dutch painting, all the available light seeming to fall on her and single her out’. And then, later, when called to make a declaration of his feelings, he tells us that ‘nothing I said would come anywhere near the breathless, awed sense of the other I experienced whenever she and I were in the same room.’ We have the sense, all the way through these pages, of a man so attuned to beauty that it renders him speechless; of a man so haunted by mystery that the world is rewilded in his gaze.

Too often, perhaps, we talk about wildness as something out there, something beyond the human. Our job is only to remove ourselves from the equation. But, compellingly, Burnside sees the possibilities of rewilding the human soul. It is not only in the woods, or in the midnight, snow-hushed wilderness, that the wild is perceptible. Love, too, is a sort of wildness. Beauty is wild; it reminds us of our wildness. I Put a Spell on You is, above all else, about that sense of otherness that makes us feel alive: the look of a woman who makes us breathless, the sound of a voice that leaves us awed, the perception of some strange element in

nature that reminds us of Narcissus, feeling part of the world at last. Burnside calls this the thrawn – another Scots word meaning many things, but principally ‘contrary, cross-grained . . . an essential and virtuous wildness’.

Fresh from an encounter with the thrawn, I begin to see that the societal you is as much a pretence, as much a mask, as the societal I – and I am glad. [ . . . ] This is why we should count ourselves fortunate when we discover that thrawnness in our companions and neighbours, for they are a manifestation of the wild right here in our midst, where they are totally unwarranted and, for that very reason, should be made all the more welcome.

Standing in the misty woods, hearing a sound we cannot locate or identify, we might be in the throes of the thrawn, and the throes of love, caught ‘on the point of possession’, at once having and not having, knowing and not knowing. Though the prevailing tenor of this book might be nocturnal, lamplit and wintry, the prevailing mood is one of profound grace. ‘I am,’ Burnside writes, ‘in some modest and ineffable way, supremely happy. Or perhaps not happy so much as given to fleeting moments of good fortune, the god-in-the-details sense of being obliged and permitted to inhabit a persistently surprising and mysterious world.’ If I Put a Spell on You is anything, it is an invitation to inhabit that world more fully, more breathlessly, so that we become, simultaneously, both the enchanter, and the enchanted, of the earth.

Seán Hewitt, 2025

I PUT A SPELL ON YOU

(Nina Simone, 1965 )

In the spring of 1958, my family moved from a rat-haunted tenement on King Street to one of the last remaining prefabs in Cowdenbeath, on the very border between the rubble-strewn woods behind Stenhouse Street and the scrubby farmland beyond. It was a move up, in most ways; the prefabs had been built as temporary wartime accommodation but, to my child’s mind at least, the cold and the damp, the putty-tainted pools of condensation on winter mornings and the airless heat of August afternoons were minor concerns, compared to the pleasure of living on our own garden plot, in what was, essentially, a detached house, just yards from a stand of high beech trees where tawny owls hunted through the night, their to-andfro cries so close it seemed they were right there with us, in the tiny bedroom I shared with my sister. Just beyond that stand of trees was Kirk’s chicken farm, where the birds ran free in wide pens and Mr Kirk, who lived in an old stone house that I took for a mansion, walked back and forth all day, distributing feed, collecting eggs and mucking out the henhouses. Later, when I was old enough, he would let me walk with him, and I took great pride in keeping pace with a grown man as

he went about his business, peering into the incubators and manhandling heavy buckets of grain from here to there, while he watched with contained amusement. On the other side of the house, towards what I liked to think of as open country, the fields ran away to the strip woods in one direction, and the grey, leechy waters of Loch Fitty in the other, and I wandered out there whenever I could, imagining myself a child of the countryside, like the boys in picture books, or one of the chums from the Rupert annuals my Auntie Sall gave me every year for Christmas.

I was only three years old when we moved to Blackburn Drive but it wasn’t long before I grasped the idea that we really were ‘coming up’ in the world. By the time I was seven, we actually had a television set and on Sundays, even though it was school the next day, Margaret and I would occasionally be allowed to sit up, eating ice cream from Katy’s van and watching Sunday Night at the London Palladium. I don’t know why I ever thought of this as a treat; the show wasn’t very interesting to a sevenyear-old and, though they sometimes had pop stars on the bill, it was mostly dancers and novelty acts. Soon, my loyalties switched to Juke Box Jury, where you could hear the latest releases and the panellists were slender and nice-looking, with beehive hairdos and mod dresses, like my cousin Madeleine. They weren’t as beautiful, though, and when Madeleine came round to our house, as she sometimes did on a Saturday afternoon, I would sit for hours at the kitchen table while she and my mother chatted, fascinated by her long, slim fingers and the cherry-red or powder-blue varnish on her nails. Every time she came, she looked different – new nails, new hair, a

I Put a Spell

new dress – but she was always Madeleine. The very first time we met, at another cousin’s wedding, I had fallen in love with her – and I’ve been in love with her ever since, in various guises. She was ten years older than me and engaged to a merchant seaman called Jackie, but she was the one who led me to understand that the lyrics of all the love songs I’d heard on Juke Box Jury, or on my mother’s radio, actually meant something. I’d thought they were just words, snippets of gibberish and hyperbole that nobody could possibly take seriously; now I knew different because, now, I was in love, and love felt very odd, like hearing the first few lines of a story I would never read to the end, because the end belonged to somebody else.

I don’t want to pretend that this infatuation was ever a real problem, however. Even my nine-year-old self knew I was suffering from a crush and, besides, there was so much to love back then, in an easy, boyish way that I suspect most men wish would last forever. At nine, I loved almost everything, more or less unconditionally. The hushed theatre of the year’s first snow. Teeming thaw water in the ditches and gutters. The arc of a well-thrown ball in the summer sky. That faraway look in Judy Garland’s eyes when the dull storyline pauses and she opens her mouth to sing. Kyries and the black vestments on Good Friday. The blur of the host on my tongue and the taunts of the high-school girls as I walked home along Stenhouse Street and up through the woods by Kirk’s farm. Most of all, I loved the older sisters of my school friends. Still-slender girls turning into more or less beautiful women and undamaged, for now, by wedlock, they were wonderful, free creatures with money in their purses and sweet, lipsticky smiles for the soppy kid who

crossed their paths from time to time. All these things made me happy, and it didn’t bother me that such happiness was an affair of the moment. A few minutes, an hour, a September afternoon in the park – the moments came, and then they were gone, so they remained mysterious and uncontaminated: a gift, rather than a burden.

Then, one rainy Saturday afternoon, just after Madeleine and Jackie got married, my mother took me to visit them in their new flat, and Madeleine played us a record she had just bought. It was ‘I Put a Spell on You’ by Nina Simone and in the space of two and a half minutes I reached the conclusion that this was the most beautiful sound I had ever heard. Everybody stopped talking to listen and, when it was over, we all sat round the table, dumbstruck, until Jackie got up and put it on again. Never having heard the song before, I thought Simone’s was the original version and this magical, if slightly sad, afternoon stayed at the back of my mind for years, with the snapshots of my mother and Madeleine in Pittencrieff Park, and the sound of Janice Nicholls on Thank Your Lucky Stars saying, ‘I’ll give it foive,’ strands in the fabric of myself that remained more or less dormant, but were there all the same, like the creatures in a fifties horror film, asleep for now in the Black Lagoon, but ready to be reawakened by the smallest shift in the weather or the tide.

I must have heard that song many times, in several versions, over the next decade or so while my father was noisily planning his escape from Cowdenbeath, first via Australia, then Canada and finally, much to my disappointment, by taking a job at the

I Put a Spell on You

steelworks in Corby, designated a ‘New Town’ under the 1946 New Towns Act, which had been set up to create ‘planned communities’ run by the Great and the Good on behalf of the common folk.1 The move south tore my mother away from her entire family and put an end to my cousin Madeleine’s visits, but nobody said anything about that because, according to my father, it was another move up, to a real house, not a prefab, a better job, better schools, better everything. It had to be better, because it had all been planned by professional people who knew what they were doing. In that, at least, I suppose he was right.

Corby was a disappointment in every way, and for my mother it was something close to a personal tragedy. Our ‘better house’ had three bedrooms, but the kitchen was smaller than the kitchen in our old prefab, and there was no room for a table,

1 New Towns were run, not by the Local Authority, but by an appointed Development Corporation. The Act states: ‘For the purposes of the development of each new town the site of which is designated under section one of this Act, the Minister shall by order establish a corporation (hereinafter called a development corporation) consisting of a chairman, a deputy chairman and such number of other members, not exceeding seven, as may be prescribed by the order; and every such corporation shall be a body corporate by such name as may be prescribed by the order, with perpetual succession and a common seal and power to hold land without licence in mortmain.’ The chairman at the time Corby was designated was Mr Henry Chisholm, the deputy chairman was the Rt Hon. Lord Douglas of Barloch, KCMG. A history of the Chisholm family notes that Henry was ‘knighted in 1971 for his public services, largely from 1950 on for creating and developing Corby, a new town [sic]. Henry was widely known and respected in financial and industrial circles for his many interests in several of Britain’s companies and industries.’

what with the clunky fitted units. Nevertheless, she put a brave face on it. She went out and bought a new, portable radio and set it on the windowsill, to keep her company, she said, while she baked and cooked, or when she was out in the garden, planting wallflowers. My father had bought a new television too, an ugly cumbersome thing perched on its own stand in a corner of the flock-patterned living room, but the rest of us continued to ignore it and our new home quickly divided along the old fault lines – horse racing and the football results on the goggle-box in one space, Sing Something Simple and the new BBC radio stations in another. So I would have heard various covers of ‘I Put a Spell on You’ over the years, but I didn’t pay it any mind till a girl called Annie leaned over the back of her seat and sang it to me one Saturday afternoon in the Charolais cafe, her breath smelling of white rum and instant coffee, her painted smile just inches from my face, her delivery less Nina Simone than a cross between Creedence Clearwater and Arthur Brown, though there might have been a touch of camped-up Janis Joplin in there too. Either way, it was quite a performance.

I was startled by this. I didn’t know Annie that well, though I’d often noticed her when she came in, because she was always laughing, always making desperate, slightly hysterical fun of everyone around her, especially herself: a careless, naive, somewhat fearful girl of nineteen, clinging blindly to the sense she had acquired somewhere that, if you didn’t take anything too seriously, there would never be anything to worry about.

So I had noticed her, and we’d said hi a few times, but I’d never paid her any obvious attention and I wasn’t attracted to

I Put a Spell on

her, which was always the dividing line, back then, between the girls you bothered with and the ones who blurred into the wallpaper. I did know one of the gang she went around with, a very thin blonde with smudgy blue eyes called Charlotte – and that day, I was aware of her, just off to one side, watching the performance with the rest of the cafe, while Annie carried on singing and I sat frozen, mesmerised by the proximity and the publicness of it all. I’d actually gone out with Charlotte a couple of times, but after a drunken night in Coronation Park it had all come to nothing, and when she started turning up at the Charolais on Saturday afternoons, it came as relief that she had obviously decided to pretend we’d never met. Now, though, she fixed me with a grim, oddly vengeful stare and waited to see what would happen next.

The Charolais was a greasy spoon in Corby’s planned community shopping precinct where people from the pubs round about whiled away the afternoon over a coffee or a bowl of ice cream. It was a short walk from most places, and almost next door to my usual Saturday hangout, a dark, faux-timbered bar room called the Corinthian, where you could buy anything from Benzedrine to a cut-price bridesmaid’s dress – and this made it doubly convenient because, for a long time, I spent every single Saturday at the Corinthian, right up until the bar staff threw me and the last malingerers out at two forty-five. More often than not, I would be nursing that cup of coffee for hours because I’d spent everything I had by last orders. That didn’t matter, though. I didn’t go to the Charolais to eat; I went for the company.

Or rather, I was there to wait, with the company, till Karen

showed up. Usually, she arrived mid-afternoon, after a trawl round the shops with her friend Kay; because she was married, she didn’t sit with me, but we had evolved a Byzantine system of signs and prompts that allowed us to communicate back and forth across the room, a system that, nine times out of ten, was effective enough that, when the moment was right, we could slip out and meet somewhere, away from prying eyes. That day, however, she turned up just in time to witness the impromptu serenade and, when Annie broke off suddenly and slumped back into her seat to laugh at her friends, she was the first person I saw among the half-dozen amused spectators in my immediate vicinity. She had obviously just stepped through the door and (still, I thought, more or less in role) she was regarding me with what would have seemed, to an indifferent observer, nothing more than amused puzzlement. Yet something else was visible in her eyes and, for a moment, I thought she was hurt, not by some imagined romance with Annie, but by the fact that, because I was single, and a man, I could involve myself in any silliness I liked, while she had to stand by and pretend that she didn’t care, not just for her own sake, but also for mine. Her husband, Patrick, was well liked by the Rangers Club heavies and, if our affair was ever discovered, she knew exactly what would happen to us – especially to me. Still, whatever the emotion was that I had seen in her face, it quickly melted away as she nodded briefly, not at me, but at the clutch of girls around the next table, then joined Kay, who had already found a free place some distance away. Kay knew, of course, but she had been sworn to secrecy – a secrecy she resented, partly because she thought I was an

I Put a Spell on

idiot, but mostly because her husband, Jimmy, was Patrick’s best friend and, if things ever came out, she would have some difficult explaining to do. Now and then Kay’s intense dislike of me would sometimes come to the surface, and that posed a real threat to our shabby little secret because, as everybody knows, there’s a thin line between love and hate and, sometimes, a casual observer will mistake one for the other, with potentially disastrous consequences.

My mother didn’t like television to begin with; she preferred to stay in the kitchen and listen to the radio. She would sing along with novelty items from her own era – ‘Mares Eat Oats’, say, or ‘What did Delaware, Boys?’ – but when a love song came on, she would stop peeling potatoes or sifting flour, and stand by the window to listen. One favourite, as I recall, was Andy Williams’s version of ‘Can’t Help Falling in Love’ – which, in some ways, is the flip side to ‘I Put a Spell on You’. To fall willingly, helplessly, under that possibly malevolent spell had, to my child’s way of thinking, a troubling innocence to it and, for various reasons, that innocence has beguiled me ever since. Time and time again – helplessly, inevitably – I have rushed in ‘Where Angels Fear to Tread’ (another Andy Williams favourite) and then, guilty for having made the mistake yet again, I’ve wondered vainly how to rush back out. Time and time again, I haven’t worked out how to deliver the appropriate goodbye and, like my mother, perhaps, I have waited – because, in waiting, there comes a grim satisfaction that while it isn’t quite penitence can feel awfully like it.

It’s dishonest, of course, this penitential condition. Soon,