www.penguin.co.uk

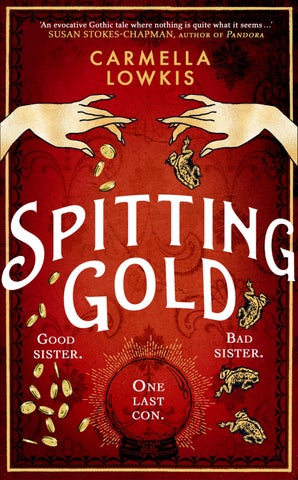

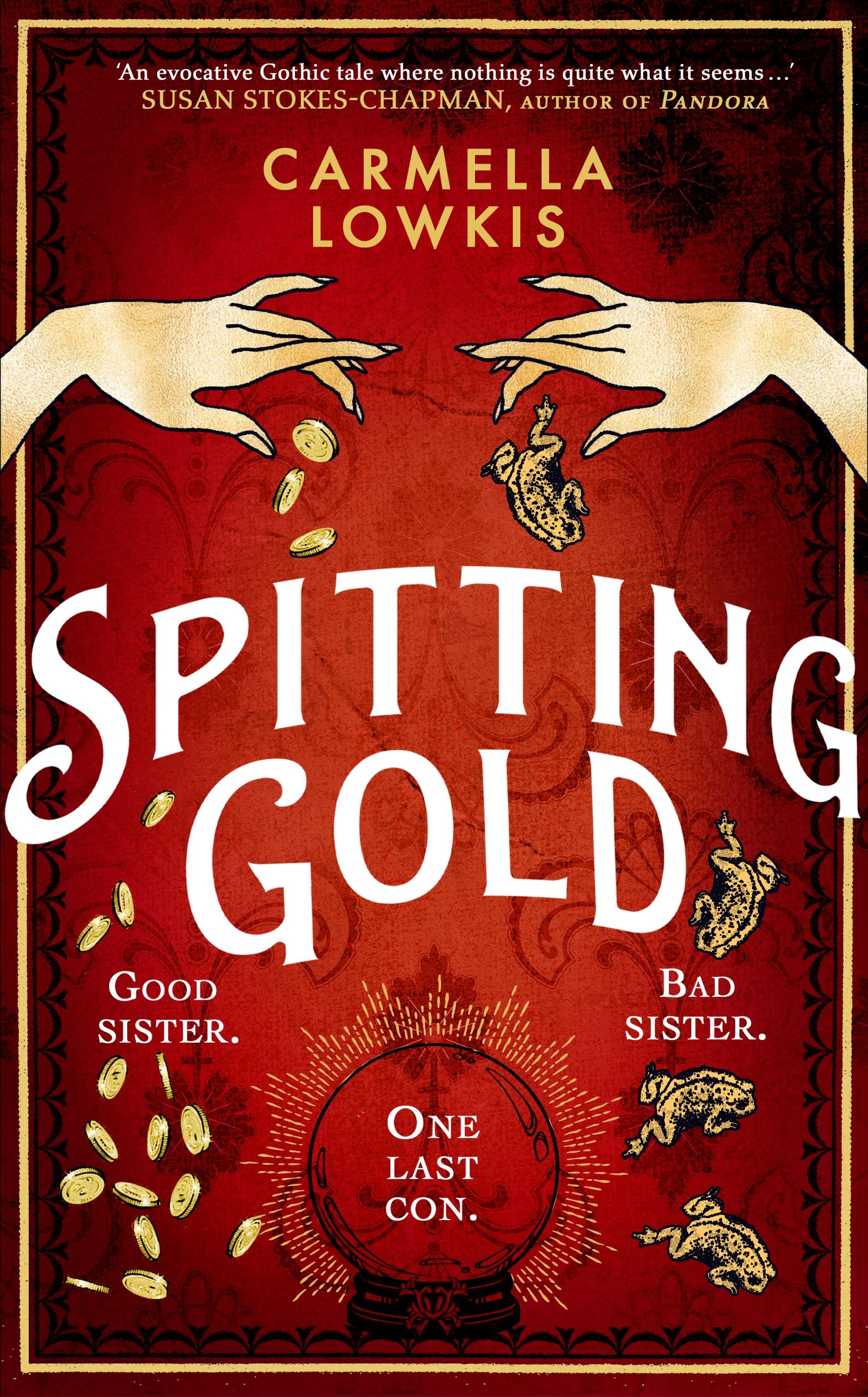

SPITTING GOLD

Carmella LowkisTRANSWORLD PUBLISHERS

Penguin Random House, One Embassy Gardens, 8 Viaduct Gardens, London SW11 7BW www.penguin.co.uk

Transworld is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com

First published in Great Britain in 2024 by Doubleday an imprint of Transworld Publishers

Copyright © Carmella Lowkis 2024

Carmella Lowkis has asserted her right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 to be identified as the author of this work.

This book is a work of fiction and, except in the case of historical fact, any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

Words on p. 3 from ‘The Fairies’ by Charles Perrault, translated by A. E. Johnson

Words on p. 165 from The Skriker © Caryl Churchill (Nick Hern Books, 1994)

Every effort has been made to obtain the necessary permissions with reference to copyright material, both illustrative and quoted. We apologize for any omissions in this respect and will be pleased to make the appropriate acknowledgements in any future edition.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBNs 9780857529466 (hb) 9780857529473 (tpb)

Typeset in Adobe Garamond by Falcon Oast Graphic Art Ltd. Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The authorized representative in the EEA is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin D02 YH68.

Penguin Random House is committed to a sustainable future for our business, our readers and our planet. This book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper.

For my sister

15 July 1866

i am working on a pair of gloves. They are for a man. I wonder who he will be, if he will know where his gloves began their life. Really, I do not need to do this: we mere accused are not obliged to do any work. Most of us choose to, even so. The sewing is something familiar to cling to in this place. From aristocrats to slum-dwellers, we women are all united by our ability to wield a needle and thread. There are no distinctions in Saint-Lazare: all the accused are housed together in the common dormitory. Regardless of crime or class, we all rise together at five a.m., we pray together, we eat the same broth – which includes meat only on a Sunday – and we exercise in the same yard. There are prostitutes, drunks, thieves, vandals, swindlers –some of them children no more than twelve – and murderesses, like me. Word gets around quickly about us, and we are left to ourselves, so I am not bothered by any of the petty in-fighting I sometimes see among the others awaiting sentence. This is a kind of purgatory, for none stays here long. We all wait to hear where we will be sent next. If we are lucky, it may be hard labour in the provinces; if we are unlucky, the Grande Roquette, and the guillotine that resides there. But I do not need to rely on luck.

I am going to walk free.

PART ONE

‘Look what comes out of your sister’s mouth whenever she speaks! Wouldn’t you like to be able to do the same thing?’

— ‘The Fairies’, Charles Perrault, tr. A. E. Johnson

3 April 1866

the figure had been standing across the street for an hour now. When I first noticed it through the window, I had passed it off as simply another pedestrian, perhaps someone waiting for a friend. I was sure that the rain, just starting, would keep it from loitering about: Paris in the rain was a miserable place. The streets would be transformed from pleasant thoroughfares into swamps, churned to mud beneath shoes, hooves and carriage wheels. Grime seeped into the seams of dresses and clung to the legs of urchin children. Watching this from my room, separated from the squalor by only a thin pane of glass, I was thankful for the protection of my warm apartment.

The figure proved hardier than I had imagined. When next I glanced outside, it was still there. Standing in the same spot. The cloak gave it an uncertain shape which seemed to waver at the edges where raindrops blurred the scene. Tall. Reasonably broad. The silhouette of a woman. No clues further than that; nothing to suggest that she was anybody of my acquaintance, but as time wore on I became increasingly convinced that whoever it was, she was waiting for me.

I would get like this sometimes, even as a child: sure that the world was conspiring against me. Papa had called it paranoia; Mama, intuition. I supposed that which parent was correct

depended upon the outcome. Which of them would prevail this time?

I leaned in to look closer, but my breath soon turned the pane as misty as a storm glass. All that I spotted before my exhalations obscured the view was a glint of pale skin beneath the shadow of the hood: her face appeared to be turned towards my building. The sight made me jump, and I stepped quickly back out of sight.

My boudoir was suddenly cold. The fire had burned low, and a creeping sensation was starting across my forehead where it had been pressed to the window. Silly nonsense. Letting my imagination run away with me. A fine habit for a child, but not one suited to a fully formed woman. I would not look again. The figure was surely awaiting an appointment, or perhaps was one of those women of a certain trade – although, granted, the shapeless cloak did not seem to match this latter theory. But what other explanation could there be?

Whether by the grace of this line of thought, or by the gloomy atmosphere of the day, memories of fairy tales and ghost stories began to stir. I could almost hear the whisper of Mama’s voice in my ear as she told the midnight secrets of the graveyard. But this morbidity would not do. I rang for the housemaid, Augustine, and directed her to build up the blaze. A good heat would soon evaporate these phantoms.

The girl set about stoking and piling and conducting the little manoeuvres that one employs to coax a fire. It was an alchemy I knew well – better than Augustine, judging by the trouble she was having with stacking the kindling. The fires back at home had normally been built by Papa; though, when we were older, my sister and I had taken our turn as well. But now I had servants, and it would have been improper to correct

them on their technique. A lady should not know how to perform such menial tasks; to demonstrate my knowledge could have raised doubt about my position. Eventually, Augustine managed to bring the fire to life.

Besides her difficulty with this, she was an otherwise competent girl of sixteen, who had been in my service for about six months now; a hard worker, if a little timid, and with a troublesome habit of neglecting to dust in the corners. Sensible, though. Yes, this would be easy to settle, I thought as I watched her work. Once the fire was satisfactory, I beckoned her over to the window.

‘Do you see that person standing across the road, Augustine?’ I attempted nonchalance in the tone of the question, but the accompanying gesture of my palm rubbing across my forehead likely betrayed my unease – something that I realized only once it was too late. Augustine peered out in the direction I indicated and, when I saw that she had noticed the figure, I said, ‘Yes, that one. Please send Virginie to enquire of the porter who it is.’

Th at done, I hid myself a little behind the curtain, and watched to see what would happen. Presently, the porter hove into view. He was a stout man with large red whiskers: unmistakable even through the rain. As I had requested, he crossed the road and shared some words with the woman. After a moment, she raised one arm and pointed directly at my window.

My heart gave a savage leap against my ribs; I was forced to hurry out of view. Who could this stranger be? And what could she want? My husband always warned me to be cautious: a man of his position was sure to make enemies, sure to merit blackmail. Every secret that I had ever held churned within my brain, as I tried to find one that would explain this strange apparition.

That this person wished me harm, I was certain, as if gripped by premonition. Erring on the side of Mama.

When a knock sounded at my door, I almost cried out in fright. Then I realized that it was Virginie, my lady’s maid. I smoothed my hair and called for her to enter.

‘What word from the porter?’ My voice managed somehow to remain steady despite the gasping of my pulse.

‘Monsieur Coulomb sends his apologies, Madame,’ Virginie replied, ‘but the lady outside would give neither her name nor purpose. She did, however, request that I bring you this visiting card. Only, she directed that neither I nor the porter was to look at it.’

Virginie held the card face-down so that the lettering could not be seen. I took it from her and turned away. It was a simple design, with none of the fashionable miniatures or messages that many of the upper class preferred. All that it bore was a name and address: Mlle C. Mothe, 34 rue de Constantine, Belleville.

At the familiar words, the thrumming of my heart gave way to a strange tranquillity. I lowered the card. There was a mahogany writing desk against one wall of the boudoir, with a drawer that could be unlocked only by the key that I wore about my neck. I crossed to this now, opened it, and placed the visiting card inside. Then I fetched a coin purse and took out a couple of francs.

‘Please show the lady into my rooms,’ I said, moving back over to Virginie. ‘Make sure that my husband does not see –perhaps the servants’ stair would be best.’

Virginie bobbed her head. ‘Of course, Madame.’

‘And Virginie . . .’

‘Yes, Madame?’

I reached for her hand, pressing the money into it. ‘You will not tell anybody of this?’

‘Of course not, Madame,’ Virginie replied. Her expression was unreadable, just as any good servant’s should be. Frustrating when one wished to gauge a reaction, however. I would have to trust that the money would out-value the social capital one might gain from such gossip. And Virginie was not known to be a gossip.

While I awaited Mademoiselle Mothe, I relocked my desk, and then examined myself in the looking glass. It had been over two years – oh, how I had changed in that time! A smattering of grey had already begun to appear in my hair, and my waist was threatening a decline beneath my stays. This was the price of having a paid cook to hand! But my wardrobe was considerably better, my posture more refined: I looked a respectable, well-bred woman.

Taking a seat on the Turkish divan, I tried to arrange myself as impressively as I could, and awaited Virginie’s rap at the door.

When it came, I called out, ‘Enter!’

Virginie led the cloaked figure into the room. This latter was dripping with water from where she had stood so long in the rain, but, appearing now in the warm boudoir, she looked far less ominous.

I directed Virginie to take the cloak and hang it before the fire – which seemed to take an age – then finally dismissed her. At last, I was alone with the woman who had waited so long to catch my attention. ‘So you found me, Charlotte,’ I said. Charlotte only smiled in response. Her smile hadn’t been at all altered by the years. My resolve softened at the familiar features: her square jaw in contrast to my rounded one; her blonde hair honeyed where mine was ashen; her thick, clumsy wrists the disappointing twins of my own. Yet she was in some ways entirely different, more haggard. There was a recent wound

upon her brow, about the length of a little finger and not quite healed. Her under-eyes were dark, her face sallow.

My pose on the divan felt suddenly absurd. I rose hurriedly, leaning to kiss Charlotte’s cheeks in order to disguise the awkwardness.

‘I am truly pleased to see you,’ I told her. ‘Certainly, I should have preferred . . . Well, you are here now; I see no use in quarrelling over it.’

‘I weren’t sure if I should come,’ said Charlotte, all in a rush. ‘I kept turning back, then changing my mind and whirling round again – I must’ve looked like a spinning top! Then I couldn’t get up the nerve to approach that porter of yours. I kept thinking, what if he sends me right away without even listening to what I’ve got to say? Truth told, I thought that’s what he was coming to do just now.’ She finally paused long enough to take a breath. ‘But here we are.’

‘Here,’ I said, ‘come closer to the fire. It will be no wonder if you have caught your death. You never were one to behave sensibly, were you?’

Charlotte allowed me to guide her to the hearth. Her skirts immediately began to steam. ‘I s’pose not,’ she said, but she sounded distracted. ‘You don’t need to talk to me like that, you know.’

I smiled thinly, refusing to be goaded. ‘I have no idea what you mean.’

‘La-di-da,’ she replied. Her eyes were roving around the room, taking everything in. ‘You’ve got a beautiful house. Almost like the ones that we used to play-act. You remember those?’ She adopted a silly, girlish voice for a moment. ‘“When I am grown up, I shall have a carriage with horses, and twenty servants, and a hundred dresses, and I shall eat Turkish delight every day.”’

She paused, peeling off her gloves to warm her hands before the flames. ‘Do you? Eat Turkish delight every day?’

‘Charlotte . . . Why are you here?’

She hesitated, and then said, ‘Papa’s ill.’

‘Not dying?’ I asked, then winced at my own bluntness. It was not as if my sister would have come for anything less, not after how we had last parted. My nerves were beginning to buzz again. I could feel them like gnats in my skull.

‘I . . . I don’t think so, no, for the time being. But if the doctor stops treating him . . .’ Charlotte was looking very carefully at her hands. ‘I’ve burned right through my savings; the man’s good, but very expensive with it. I’ve done everything else I can think of, Sylvie, but I can’t pay the bills any more.’

I shifted uncomfortably. ‘If you have come to ask for money—’

‘That’s not why I’m here, I swear,’ Charlotte said, holding up a finger to urge silence. ‘I know you can’t withdraw all that without the Baron asking why. But I’m desperate. The kind of piecework I’ve been sewing just ain’t enough. Do you know what it pays? And to think that you and I used to make as much in a day as I now make in—’

Having already realized Charlotte’s meaning, I jumped in to interrupt. ‘That is entirely out of the question.’

‘It’d only be one more time,’ said Charlotte. ‘I’ve already found a client.’

‘I want no more to do with all of that.’

‘I don’t remember you being so particular about “all of that” when it was paying your dowry.’

I avoided her eyes. That had been a different time, of course. A time when consequences were something that happened to other people, never to us.

Charlotte reached a hand towards my shoulder, but changed her mind halfway through and let it fall limp between us. ‘Please, Sylvie, you know I wouldn’t ask if I’d got another way out of this. Believe me, it weren’t easy to find you again.’

With good reason. It had been no accident that Charlotte had never received the change-of-address card.

We were silent for a moment as Charlotte repositioned herself to dry her back. ‘Do you never miss it?’ she asked. ‘The thrill, the excitement.’

‘The danger of being found out.’

Charlotte gave a devilish smile. ‘But weren’t that part of the fun? And now here you are: you, Sylvie Mothe—’

‘Baroness Devereux.’

‘A society lady. A pretty wife. Tell me, how is it that you’ve spent your day? Embroidery?’

‘I happen to find embroidery quite stimulating,’ I told her tersely. But Charlotte’s words had stirred up the memories that I had carefully hidden away, like the visiting card I had just locked in the drawer of my desk. I put a hand to the key about my neck.

‘We were the best in the game,’ said Charlotte. ‘Yes, we were,’ I said.

I had meant this to highlight the past tense of the statement, but Charlotte seemed to interpret my words as agreement. She said, ‘You were. Sylvie, I understand your worry. I do. Your husband—’

My husband. That was a thought that instantly dispelled any nostalgic reminiscences. ‘Alexandre is a wonderful man,’ I said, a little sharply. ‘An important man. You cannot possibly realize just how influential one’s reputation comes to be in our circles. Even the smallest whiff of scandal . . . It does not bear

thinking about. I have to consider his career. And our future.’ I absently placed a hand across my midriff as I thought of all that the word entailed.

Charlotte gave me a funny look. ‘You ain’t—?’

‘No,’ I said quickly, heat rising in my cheeks at the misunderstanding. ‘Not yet, but I mean that one day I hope to be. This is what I want, Charlotte. I know that you never wanted a life so . . . so ordinary. With your grand dreams of fame and adventure—’

‘Our dreams,’ Charlotte corrected me. ‘You played those make-believe games as much as I did.’

‘But they were of your invention,’ I insisted. ‘And my point is that those games of yours no longer fit into my life. So you understand that I am no longer at liberty to take the kinds of risks that you propose.’

Charlotte had wandered nearer to the mantelpiece now, and was fiddling with the ornaments kept there. I watched to make sure none went into her pockets. ‘Course I can see why you don’t want to put all this at risk,’ Charlotte said. Her face had the appearance of composure, but there was a slight twitch at the very corner of her mouth. It was the same twitch that always appeared when she was mocking someone.

Surely our first meeting in over two years need not end in a quarrel? With some effort, I ignored the jab at my pride. ‘I wish that I could be of more help,’ I said firmly, ‘but there is nothing that I can do.’

Charlotte did not seem to mirror my qualms about falling into an argument, as she curled a lip and said, with a curdling tone, ‘I knew family meant nothing to you, but I never imagined even you would turn your back on a dying man.’

There was a moment of silence, as if we both were too struck

by the audacity of the accusation to continue our conversation. Rain pattered like fingers at the windowpane.

‘You will leave my house now,’ I said at last.

‘I—’

‘You will leave, and you will not return.’ Saying this, I crossed to the bell and rang. ‘Virginie will show you out. If you do not go quietly, then I will be forced to call for the gendarmerie and tell them about the statuette in your pocket.’

Charlotte sneered and thrust a hand into her skirts, pulled out the statuette and then threw it to the ground. A porcelain Eros with bow and arrow. Luckily, it did not break – it was a favourite of mine, a gift from Alexandre in the early days of our marriage. It was spared from any further acts of destruction by the arrival of Virginie.

‘Please escort this woman back outside,’ I said, raising my eyebrows to indicate that it might prove a difficult task.

‘Cast me from your house, then!’ Charlotte exclaimed. ‘But I hope you enjoy hellfire, Sylvie Devereux, because the Lord’ll surely cast you from his.’ As damnations go, it was an impressive one, but Charlotte only believed in the Lord when it suited her purposes. She shouldered her way past Virginie, who was forced to hurry after her.

Then I was left alone with my anger. And oh, was I angry! It was a swelling, sickly wave in my chest. How dare she come crashing back into my life with this? To talk of family and dreams and God! Charlotte was a hypocrite through to the bone. To suggest that I should feel any hint of filial duty to our father, after all the ill treatment I had endured, years and years of it, before I had managed to escape . . . And now it transpired that my sanctuary was not safe from it all; my old life could come striding in at any time, dripping on my carpets and pocketing

my ornaments. I looked down at the statuette and felt a sudden wave of disdain, as if Charlotte’s touch had somehow sullied it. Before I was quite sensible of what I was doing, I had plucked it up and cast it against the wall. There was a satisfying peal as it splintered into pieces.

And as for Charlotte’s visiting card, that could go, too. I fumbled to unlock the desk drawer, hands shaking with barely contained emotion, and yanked it open, setting the contents rolling out of order. Where had the damned thing got to? I rummaged among my knick-knacks, intending to chuck the card into the fire. I could not find it. It must have skittered under something. I lifted items out, hoping to uncover it: a pair of scissors, a notebook, a little velvet pouch. This last gave me pause. I considered it, and then tipped it up so that the contents fell into my palm with a chink-chink. A locket on a chain. It was a pretty thing, although the silver was tarnished and the hinge was stiff when I eased it open. Inside was a miniature – our mother. A high-browed and pale-skinned face with beautiful dark eyes. Not that the image could capture even a fraction of what her eyes had been in life: those deep, inky irises that seemed to contain other worlds, like windows on to the night sky. Neither I nor Charlotte had inherited these; we had our father’s river-water grey. No, our mother had been an exceptional beauty; a beauty that could occur only once, that could not be passed on.

Gazing into this paltry representation now, I knew what she would say. Be kind to your sister, and forgiving to your father. They need your care more than ever now I am gone.

I thought of all the trouble that Charlotte could get herself into: with her clients, with Papa, with the law. There was good reason that we had always worked as a pair in the past. And as

the elder by six years, it had been my duty to watch out for her for as long as I could remember. But even if I wanted to help, how could I? There was my husband’s position as a deputy prosecutor to think of. Alexandre must be my first loyalty now: he was my new family.

But the locket felt warm, skin-like, under my thumb. Mama’s head was tilted at a slight angle, as if patiently awaiting the answer to some question.

It was probably too late to catch Charlotte. Even if she had put up a fuss, she would have been chased off by now. Would she not?

Shoving the locket into my skirts, I hurried out of the apartment and downstairs.

On the street, there was no sign of my sister. Luckily, Coulomb was there, leaning against the porter’s lodge. A pipe curved out of his lips.

‘The woman who was here,’ I said, dispensing with the usual pleasantries, ‘which way did she go?’

Following Coulomb’s smoke-choked response, I hurried down the street. I hadn’t run like this since I was a child.

What on earth must Coulomb be thinking? And I had not even stopped to put on outside clothes. I was still in my house slippers! Never mind; with luck, I would catch Charlotte before I caught cold. Was that her there? The hem of a cloak turning a corner – yes! I called her name desperately, voice hoarse.

Charlotte turned, a look of surprise painting itself across her face as she recognized me. This was immediately replaced with one of chagrin. ‘Oh, for fuck’s sake, if it means that much to you, you can have it back,’ she snapped, pulling a paper fan from her pocket with a flourish.

I stared at it blankly for several moments, before I realized

that I had last seen it decorating a nook in the entrance hall. Christ, when had Charlotte even had the chance to take it?

‘Never mind that,’ I said, then had to stop when a sharp pain hit my chest; knives of cold exploding within me. I held up a hand: a signal to give me a moment. Once my lungs had stopped screaming, I tried again. ‘I wanted to ask— Not that I definitely will— I still have to— But if I did— What is the job?’

‘You’ve changed your mind?’

‘Yes. No.’ I drew in another breath, concentrating on the feeling of my lungs expanding like a pair of bellows. Expand, contract. ‘I need to know more,’ I said. ‘But not now; we cannot talk here. And it will be dinner soon. Can you meet me tomorrow?’

‘Even better,’ said Charlotte, ‘I’ve got an appointment to meet the clients. Come with me. If it’s too much, you can pack the whole thing in then and there. And if not . . .’

We both let the silence trail on.

‘Very well,’ I agreed at last.

Once we had negotiated a time and place to meet, we said our goodbyes, and Charlotte departed once more. She melted so effortlessly into the bustle of the streets, it would have been easy to imagine her insubstantial. But I knew well enough that even the insubstantial could wield a great deal of power.

Returning to my rooms – giving Coulomb a civil nod when I passed, as if nothing untoward had taken place – I tried not to dwell on the way my afternoon had unfolded. Best to put it out of mind until tomorrow. Seeing the state I was in, Virginie hurried to assist me in changing for the evening meal. Glad as I normally was of her company, that day I sent her away as soon as we were done, preferring to brood alone. I took up a pattern that I had been embroidering, but, before even a minute had

passed, I had thrown it down again in disgust. All that I could hear was Charlotte’s teasing voice. And now here you are: you, Sylvie Mothe. The people who had known me by that name would hardly have believed where I was today. And the people who knew me as the Baroness Devereux, well . . . They never needed to know the details of the rock out from under which I had crawled.

I ought to have been frightened. After everything I had done to reinvent myself, here was the threat of exposure if I committed even the tiniest blunder. Yet that was the thing – underneath the anxiety and irritation, there was a tremor of excitement, just as Charlotte had said. I could feel it fluttering in my midriff like a caged songbird. It had been locked away for over two years, but now it was ready to sing.

4 April 1866

i met with Charlotte the following day in the Jardin du Luxembourg. From there, we took a hansom cab to the clients’ apartments on the place des Chevaux.

‘You are a real Cendrillon. I am quite unaccustomed to such luxury,’ Charlotte joked, using the affected voice she normally adopted for clients. Th e one into which I had now trained myself on a permanent basis. ‘You had better be careful lest I get used to it.’ She had walked all the way from Belleville.

‘You really ought not to travel without a chaperone,’ I told her.

Charlotte cast me a look, as if to say, And just who d’you propose for that job? Whom indeed? Mama was dead; Papa ill; myself gone. But surely Charlotte had friends? As a girl, she had always had some female intimate or another, always some whirlwind friendship with an inseparable companion, until the turbulent attachment would be broken by a ‘lovers’ quarrel’. And then how she would wail and mope! Like a young Romeo thwarted in pursuit of his paramour. She always did get too invested in these entanglements. I was a solitary child by contrast. Secretly, I had preferred it when Charlotte suffered such break-ups; at last I would have my sister to myself again, and would no longer have to feel jealous or excluded. At least until the next charming young thing came along.

But what if there were no more charming young things? Had they been replaced with nothing but loneliness? I had never paused to wonder to what manner of existence I had left my little sister – or, more accurately, when I had wondered, I had put a stop to it when I did not like the conclusions to which it led.

‘Even so,’ I said, ‘you would not want . . .’

‘People to get the wrong idea?’ Charlotte quipped. And the unspoken: Or the right one? ‘Anyway, you don’t need to worry –I’ve always got my knife on me.’

The implication of this sentence settled over me as slowly as a morning frost. ‘You carry a knife?’

‘Don’t you? Really, Sylvie, you’ve got to have the tools to protect yourself.’

I could think of no suitable response to this.

Not yet fully rid of my anxiety that I might be observed, I insisted that the hansom stop some streets away so that we could walk the final stretch. This was the Marais district: the roads here were a far cry from those around my house, all haphazard corners and irregular cobblestones; we might have stepped back into medieval times. Charlotte remained silent as we walked. I wondered if I had said something to upset her.

Underfoot, there was a squelch from yesterday’s rain. The air was heavy with rich decay and the sharper, slicing whiff of sewage. Despite this, the streets were busy, and I found myself checking my pockets every few steps for fear of thieves, hugging my reticule tightly to my side.

It was a relief to reach the place des Chevaux, a square of buildings surrounding a compact park. One half of the square was medieval, the wattle-and-daub now fronted with limestone, giving its structures a sombre look. The other half was of a

later era: four storeys of red brick with blue slate roofs in the Louis XIII style, reminiscent of the place des Vosges, if one were to remove the arcades and allowed for dilapidation. It had clearly once been beautiful, pre-Revolution, but had now gone the same way as the ancien régime nobility who had previously inhabited it. There was rubbish strewn across the cobbles, suspect-looking shopfronts, and the park was unkempt. I spotted an inebriate tottering into one of the alleyway offshoots.

‘What a place,’ I murmured.

It did not seem to bother Charlotte. She led me to one of the buildings on the red-brick side and rang at the door. There was a wait – long enough for me to examine the paint peeling off the doorframe – and then a porter or some other domestic answered.

‘Charlotte Mothe,’ Charlotte informed him, using her high-society voice and presenting one of the now-familiar visiting cards. ‘I am here to see the Dowager Marquise. She ought to be expecting me.’

My first impressions of the de Jacquinot family were not entirely favourable. They received us in a dark little parlour, and perhaps some of the room’s shabbiness discoloured my view of them. It was furnished sparsely, with certain marks upon the floor that made me suspect there had once been more pieces, since removed. Pale outlines on the wallpaper suggested paintings that had similarly disappeared.

‘The Mothe sisters.’

It was our hostess, Madame de Jacquinot, who announced us to the room. Between the silver cap of hair on her head, her grey dress and her squat figure, she reminded me distinctly of a pepper pot. Although I understood her to be the Dowager

Marquise, her clothing was modest and had a low-pointed waistline not popular since my mother’s days. This was evidently an aristocratic family fallen upon hard times.

‘Mesdemoiselles, please, do come and sit with us,’ she went on, beckoning to the settee. This was a funny way to phrase it, as the other members of the family were seated as far apart from one another as was possible. It was as if each had chosen a point on the compass and stuck to it. ‘How was your journey today?’

As we traded niceties, I eyed each of them. The north was occupied by the Dowager Marquise’s son – the current Marquis de Jacquinot. He was maybe twenty or twenty-one; he looked about the same age as Charlotte. Fairly attractive: tall but not particularly broad, with auburn hair and a neat little moustache on his upper lip. Instead of joining the conversation, he was reading a book. Or, rather, he was pretending to read a book, as I caught him sneaking glances at me over the pages.

To the east was a bloodless girl, a little younger than the Marquis, who reminded me for all the world of a wilting flower. This was Madame de Jacquinot’s daughter, Florence. Her features were pretty, but pretty in the way that one had seen hundreds of times before.

Finally, the south was home to an old man, so tucked away in a shadowy armchair that I barely noticed him until he was pointed out as ‘Comte Ardoir, my father’. He might have been a skeleton already, for all the flesh he had upon him.

This left the western portion of the room to Charlotte, myself and Madame de Jacquinot. The three of us were obliged to share an undersized settee, making it rather hard for Charlotte and me to drink the coffee that had been offered to us without elbowing one another.

‘Now, then,’ said Charlotte, once a polite amount of time

had elapsed. ‘I think it will be best if we approach this directly.

Madame de Jacquinot: I believe you are being haunted?’

‘In fact, we all are,’ said Ardoir, in the churlish tone of someone who resented being overlooked.

Charlotte adopted a saccharine smile. ‘Yes, of course, Monsieur.’

Madame de Jacquinot, with a glance at her father, said, ‘Well, I do feel a little silly when you say it out loud . . .’

‘Please put aside all notions of “silly”,’ said Charlotte. ‘My sister and I are here to listen to whatever you have to say. You have . . . sighted a presence in this building?’

‘Oh, not sighted, no,’ said Madame de Jacquinot. ‘I would not say sighted. But I have sensed her, here in the apartments, you understand? She wakes me often at night with all manner of noises: knocking, banging. In the morning, we rise to find things out of their rightful place. And . . . oftentimes, I will feel a chill, as if somebody is breathing upon my shoulder.’

‘Naturally, I would have thought it a case of female overimagination,’ said Ardoir, ‘but I have felt it, too, in fact.’

‘Naturally,’ Charlotte agreed, managing to sound mostly sincere. ‘You know, temperature fluctuations are frequently an indication of spiritual activity, Monsieur.’

The young de Jacquinot coughed behind his book; it was well hidden, but I thought he might have been suppressing a laugh. Apparently Ardoir held the same suspicion, as his fingers tightened, claw-like, upon his armrest at the noise.

There was a stirring from the daughter, Florence. ‘I have seen her,’ she whispered. ‘She comes into my room at night.’

I shared a quick look with Charlotte at this. To have a manifestation before we had even set to work . . . Well, it was no wonder that Charlotte had been so confident about this

endeavour! It seemed almost that there was no convincing to be done on our part at all.

‘What is it that she does, when she is in your room?’ I asked.

Florence kept her face turned down towards the floor, but she did for a moment lift her gaze up to meet mine. Her eyes were pale, with barely a glimmer of spirit in them. ‘She cries,’ she replied.

‘Cries? You mean to say that she wails?’

‘Not at all: she is perfectly quiet. She stands at the foot of my bed and weeps in silence.’

Unusual – in all the stories, weeping spirits were more likely to be heard than seen. I nodded thoughtfully, and waited for Charlotte to take note of this. ‘Have you attempted to touch her?’ I then asked. Lord knows why anyone would want to, but there were always the oddballs who did. And more besides: I was struck with the unwelcome memory of a woman who, having been visited by a handsome young male spirit, claimed to have . . . Well, it did not bear repeating.

‘She runs away.’ The daughter rubbed at her elbow with one hand, as if thinking. ‘Or disappears; it is hard to tell. Grandfather has seen her, too.’

‘I have also seen her,’ Ardoir agreed, magnanimously providing his male credibility.

The son gave a proper laugh this time, setting his book closed in his lap – I saw that it was a volume of Darwin’s work, telling me all I needed to know. ‘Well, there is your evidence: an old man and an unwell girl—’

‘Maximilien!’ cried Madame de Jacquinot.

‘I am sorry, Mother,’ he said, ‘but you know my feelings on the matter. What Florence needs is a doctor, not some spiritist—’

‘This “old man” is running out of patience with you, boy,’ snapped Ardoir. ‘You will not take such a tone with your elders.’

De Jacquinot opened his mouth as if to protest, but then thought better of it. ‘Of course,’ he said. ‘I am sorry, Mother. I did not mean to speak so rudely. But my point is that Flo—’

Ardoir cut him off again. ‘You would do well to remember under whose roof you are living.’

‘But it is nothing more than superstition!’

I thought it best to forestall any further bickering and confront de Jacquinot on his ‘point’ directly. ‘So you do not believe in spirits at all, Monsieur?’ I asked. A cynic in one’s midst is no trouble, so long as one can identify him as such and discredit his protests from the outset.

He looked me candidly in the eye. ‘I am afraid that I find the entire concept to be drivel. Science, now that’ – he tapped the book with one finger – ‘is what I believe in. The observable phenomena of the real world.’ He gave a sly smile. ‘If you will excuse me.’

Charlotte cleared her throat. ‘If I may, Monsieur de Jacquinot,’ she said, ‘as a matter of honour—’

‘Please, I do not believe in titles. Call me Maximilien.’

Not only a cynic and a man of science, then, but also a Republican. Lord have mercy upon us.

Charlotte gave a thin smile. ‘Very well, Monsieur Maximilien: as a matter of honour, I feel I must defend my profession.

‘I assure you that there is no “drivel” about our work. Certainly, there are charlatans out there who will take your money in exchange for their fakeries, but all professions have their crooks, and one does not dismiss the entire field of – for example – medical science as drivel, simply because one has had the misfortune to be tricked by a spurious sawbones. No, one overlooks such anomalies and believes in the abundance of evidence in favour of the field. It is the same with we spiritists.

For every crook, one hears countless stories of successful contact with the souls of the departed. Why, though only through recent advances have we been able to perfect the art, it is hardly a modern science. Since time immemorial, there have been reports of the existence of spirits, of visitations and possessions. Now, I have no way to prevent you from dismissing every single account as drivel – as people lying or being tricked – but, I put it to you, Monsieur, that it is far more likely, given the overwhelming number of cases, that these accounts are authentic. As the law of parsimony states, the most likely explanation is the simplest. And is it not simpler to believe in the existence of spirits than to dismiss an entire profession as “drivel”?’

Maximilien did not look convinced, but he was also unable to find a response. Charlotte’s arguments often had this effect on people – particularly on men, who were not used to hearing a woman defy them so confidently and with such strong rhetoric. Papa used to say that she could have talked Louis Philippe off the throne, if only the Republicans had not got to him first.

Ardoir harrumphed in approval. ‘There, boy,’ he said, ‘may we now return to the reason that we have, in fact, invited these two’ – he paused to find the rest of his sentence, beady eyes appraising us for an unpleasant amount of time – ‘charming young ladies into our home?’

Keen to move along, Charlotte turned brightly to Florence. ‘So, Mademoiselle, are you able to tell me when it was that you first became aware of the spirit in the apartments?’

‘It was just after . . .’ said Florence, but then trailed off. I noticed her eyes kept returning to the cut on Charlotte’s forehead, as if the sight of it disturbed her. She was either squeamish or highly empathetic. Whichever way, it did not speak for a strong stomach; we would have to be careful with her.