‘U erly brilliant.’

JAMES HOLLAND

‘Superb.’

DAVID

THE CLASSIC BA LE TOLD AS NEVER BEFORE

‘U erly brilliant.’

JAMES HOLLAND

‘Superb.’

DAVID

THE CLASSIC BA LE TOLD AS NEVER BEFORE

TRANSWORLD PUBLISHERS

Penguin Random House, One Embassy Gardens, 8 Viaduct Gardens, London SW11 7BW www.penguin.co.uk

Transworld is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com

First published in Great Britain in 2024 by Bantam an imprint of Transworld Publishers

Copyright © Al Murray 2024

Al Murray has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 to be identified as the author of this work.

Every effort has been made to obtain the necessary permissions with reference to copyright material, both illustrative and quoted. We apologize for any omissions in this respect and will be pleased to make the appropriate acknowledgements in any future edition.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBNs

9780857506566 hb

9780857506573 tpb

Typeset in 11/15.5pt ITC Giovanni Std by Jouve (UK), Milton Keynes Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The authorized representative in the EEA is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin D02 YH68.

No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner for the purpose of training artificial intelligence technologies or systems. In accordance with Article 4(3) of the DSM Directive 2019/790, Penguin Random House expressly reserves this work from the text and data mining exception.

Penguin Random House is committed to a sustainable future for our business, our readers and our planet. This book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper.

To Jim, for walking and talking the ground

0000HRS

1. THE BESIEGED: Lt. Col. Frost assesses state of play: buildings on fire, ammunition will need to be conserved.

0100HRS

0200HRS Enemy attack the school: knocking everyone out with a ‘bazooka’.

5. THE GENERAL: Maj. Gen. Urquhart stuck in the loft of 14 Zwarteweg.

0245HRS

0300HRS Germans surround the school. Mackay and his men repulse this attack.

2. THE EMBATTLED: Attacks into the Town called off for now. Remnants of 1st Para Bn out of touch with 3rd Para Bn. 2nd Bn South Staffs and 11th Para Bn are moving into Town to join effort to reach Bridge.

8. THE COLONELS ON THE RIVER ROAD: Decision to attack. 1st Para on the lower River Road, 2nd South Staffs along the Higher Road towards The Monastery, 11th Para Bn on South Staffs’ left flank and in reserve.

3rd Para Bn, unknown to the others in the Town, attack along River Road.

0330HRS

0400HRS

0430HRS

0500HRS

0600HRS

1st Para Bn as they attack meet 3rd Para Bn retreating along River Road: Dorrien-Smith ‘not bloody likely’.

Hand-to-hand combat along the River Road, German armour in evidence.

2nd South Staffs push on up the Higher Road to The Monastery, despite German armour making an appearance.

3. A QUIET NIGHT?: Div. HQ under Brig. Hicks trying to make sense of what to do in Maj. Gen. Urquhart’s absence. Rumour is the Bridge has fallen.

6. DIVISIONAL HEADQUARTERS – THE BRIGADIERS: Brig. Hackett argues with Hicks in Maj. Gen. Urquhart’s absence about what to do. Returns to his HQ having ‘written himself some orders’ to attack in the Woods.

7. THE GUNS. 1ST LIGHT AIRLANDING REGIMENT, RA: 1st Airborne’s firepower – is it up to the job?

4. WAITING FOR TOMORROW: 4th Parachute Brigade successfully clear of its DZs. Brig. Hackett unhappy with the situation as he finds out about it. Decides to visit Divisional HQ

7th Bn KOSB move to Johanna Hoeve area to protect the LZ for the arrival of the Poles. They encounter the enemy east of the LZ and decide not to engage.

156 Bn are ready to attack in the Woods, towards the high ground to the east. With them glider pilots, including Louis Hagen. 10th Para Bn also moving up to make their attack on the Amsterdamseweg.

0600HRS 9. TOTTERING ABOVE THE BOILING TIDE

10. THE DOCTOR: Capt. Stuart Mawson prepares his aid post.

0630HRS

0700HRS

0730HRS

0745HRS

0800HRS

0830HRS

0900HRS

0930HRS

German attacks intensify. Maj. Gen. Urquhart sprung from his loft by passing South Staffs. Sets off back to Divisional HQ. Meets Capt. Mawson at aid post.

11. THE BATTALION: 11th Bn faces the problems of fighting in a built-up area.

12. THE MONASTERY: 2nd Bn South Staffs make it to The Monastery and dig into the hollow there.

1000HRS

Radio contact made with 2nd Army, who promise relief today once they’ve got across the river at Nijmegen.

1100HRS

1130HRS

1200HRS

1300HRS

17. NO RELIEF

Fighting at The Monastery ends. Remnants of 2nd South Staffs withdraw to the Bottleneck.

16. ON THE BRINK: 11th Bn and the South Staffs attempt to take the high ground at Den Brink. Both battalions caught in the open – 11th Bn overwhelmed, Staffs also. Retreat.

Light Regiment engaging targets in support of the attacks in the Town.

15. THE BRIGADE: Brig. Hackett’s 4th Parachute Brigade prepare to attack in the Woods.

156 Bn attack goes in, initial ‘anti-climax’, seems the enemy are not present.

10th Bn moves up to the Amsterdamseweg. Timings uncertain – there is no War Diary for the 10th Bn.

13. DIVISIONAL HQ AND ELSEWHERE: Padre Pare witnesses return of Maj. Gen. Urquhart to Div. HQ: ‘an air of confidence’. Then sets off to bury Generalmajor Kussin.

14. ALARUMS AND EXCURSIONS IN THE WEST: 1st Bn the Border Regiment hold the line at the Landing Zones.

A Coy of 156 Bn meets extremely heavy resistance.

Hackett visits 156 Bn HQ: unaware of how badly it’s going.

156’s HQ joins the attack. Things going wrong.

18. DISENGAGE: With his attacks having failed in the Woods, Hackett tries to extract his Brigade from contact with the enemy.

Crowds of men retreat to the railway line. 4th Squadron RE discover the tunnel under the railway line.

1400HRS

1430HRS

1500HRS

1530HRS

MkIII Panzer attacks. 19. 1500 HRS: SKIES OVER ARNHEM: The Supply Lift arrives, followed at 1530 by the Poles in their gliders.

Focke-Wulf Fw 190 hits the church tower. Rejoicing.

1600HRS

1700HRS

1800HRS

1900HRS

26. ALL AFIRE: Systematic in their tactics, the Germans seek to burn out Frost’s men building by building.

Three Tiger tanks attack, firing AP rounds directly into the buildings around the Bridge.

2000HRS Padre Egan wounded.

2100HRS Capt. Mackay considers holding on to be almost impossible.

2200HRS

2300HRS

Capt. Queripel covers his men’s withdrawal.

22. THE CHURCH: Lt. Col. Thompson saves the Division from being cut off at the river, organizing the men retreating from the Town into a defensive posture.

21. CRUMBS OF COMFORT?: Major Powell discovers supplies in the Woods. In the Village Capt. Kavanagh tries to recover supplies.

23. LIFE AND DEATH AT THE CROSSROADS

20. ENGLAND AND THE WOODS: THE POLES: Fog-bound, Sosabowski and his men wait to leave for Arnhem; his heavy equipment goes anyway.

25. LAST BATTALION LEFT: 1st Bn the Border Regiment, who have had a relatively quiet day, repel a probing attack in the west. A taste of things to come?

Remnants of 4th Parachute Brigade start to assemble, 10th Bn south of the Wolfheze level crossing, 156 Bn further east in the woods south of the railway line.

24. FINAL DECISION: Brig. Hackett decides to dig in for the night and only move into the Divisional area in the morning.

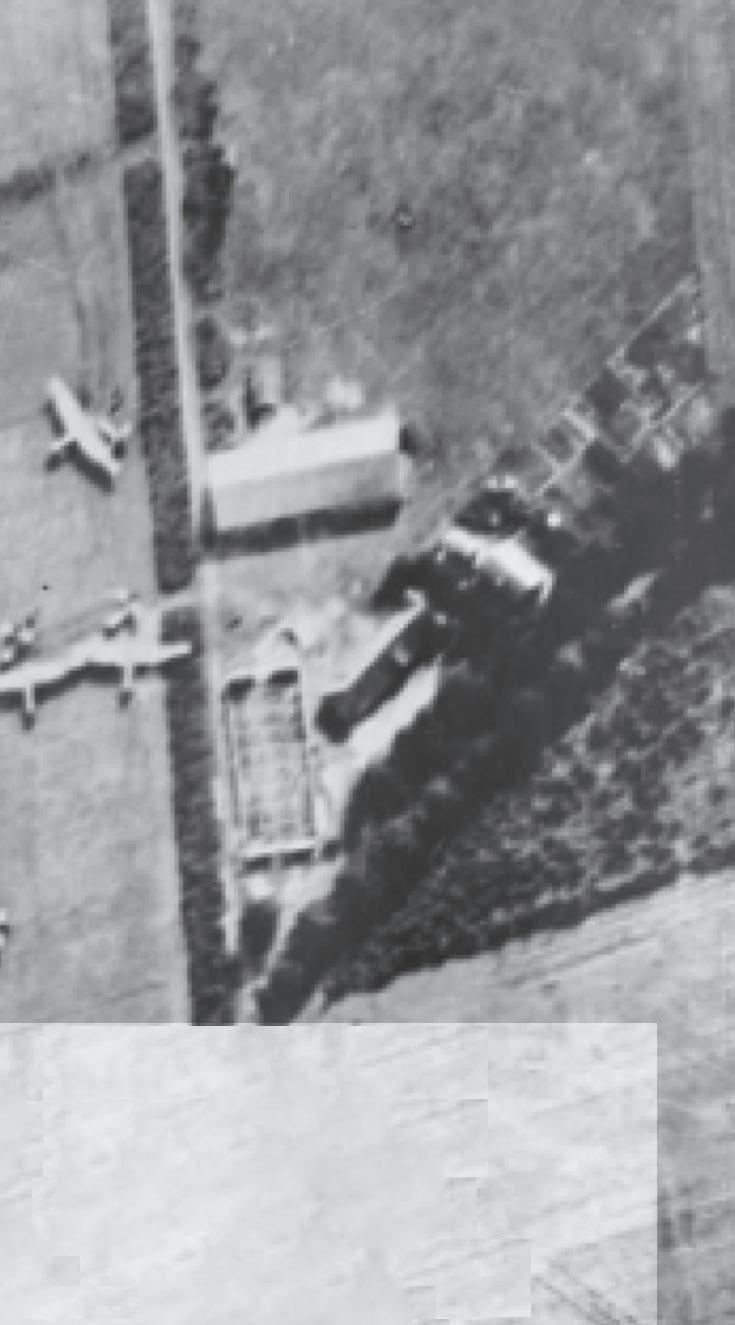

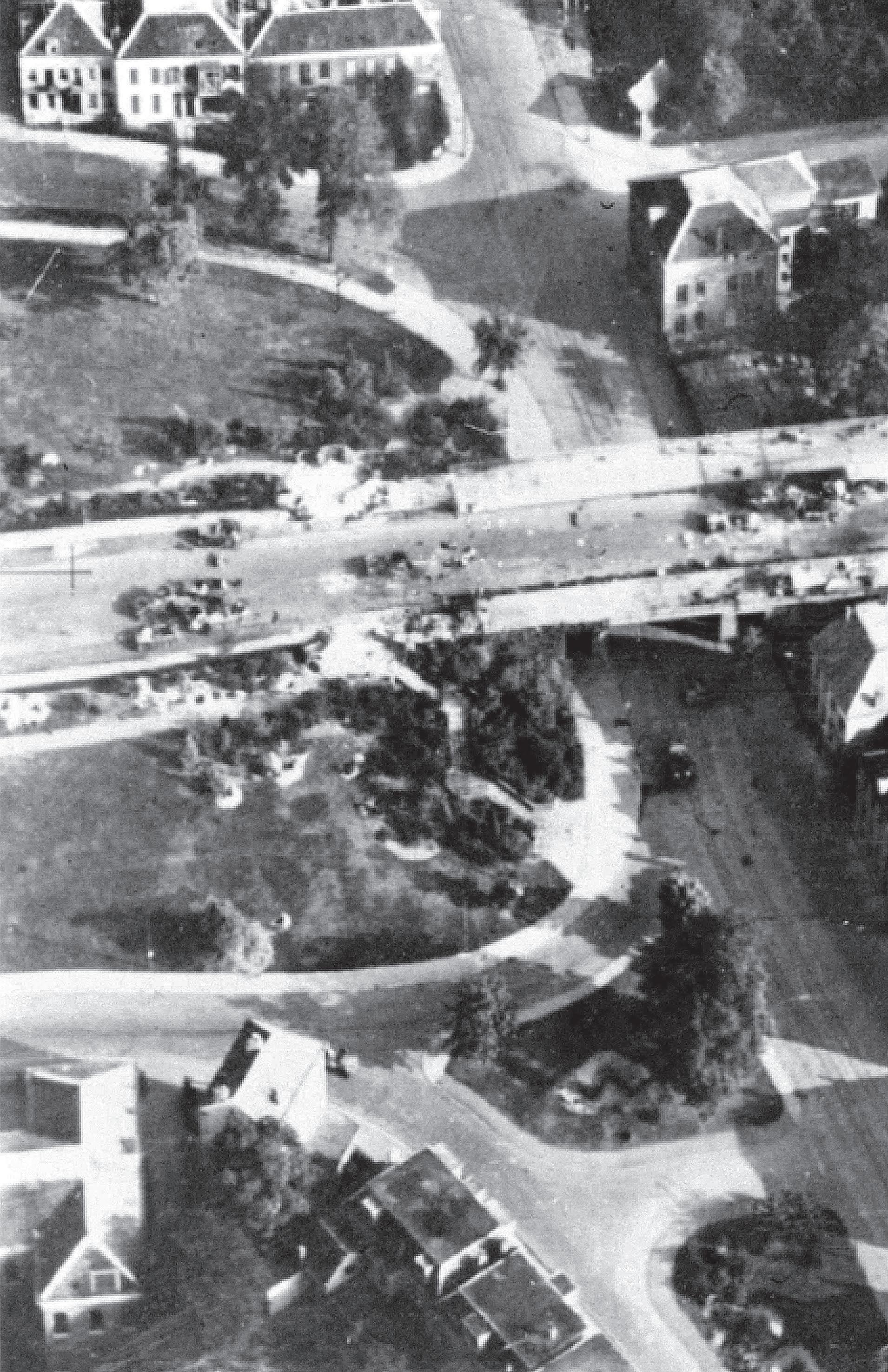

Gliders on Landing Zone ‘L’ around Wolfheze. A vast fleet of 320 gliders had set off for Arnhem on Sunday, 17 September: these large fields were ideal for a massed glider landing. Visible are the gliders’ detached tails, each one a story of a crew trying to unload their glider and get off the LZ as quickly as possible.

Countdown: 48 hours to Black Tuesday

The Hague

Ro erdam

r rijn

Utrecht

Waal

Dordrech

Moerdijk

Geldermalsen

S-Hertogenbosch

Vught

Breda

Bergen op Zoom

r n Scheldt

Tilburg

Ijsselmeer

Apeldoorn

Beekbergen

Oosterbeek ( THE VILLAGE )

Wolfheze

Ede

Rankum

Wageningen

Zelfen

Zutphen

Deelan

Driel

Nijmegen

Neogel

St. Oedenrode

St. Oedenrode

Brest

Brest Son

Eindhoven

Valkenswaard

Neerpelt

Brug Weert

Embarkation bases for Arnhem

1 Barkston Heath – C-47s (1st lift only)

2 Saltby – C-47s (1st & 2nd lifts)

3 Spanhoe – C-47s (2nd & 3rd lifts)

4 Harwell – Stirlings

5 Broadwell – Dakotas

6 Fairford – Dakotas

7 Down Ampney – Dakotas

8 Blakehill Farm – Dakotas

9 Keevil – Sterlings

10 Tarrant Rushton – Halifaxes

11 Manston – Albemarles

4th Para Bde (Hacke )

DZ ‘Y’ GINKELSE HEIDE

DUE MONDAY MORNING

1st Para Bde (Lathbury)

DZ ‘X’

SUNDAY AFTERNOON

1st Airlanding Bde (Hicks)

LZ ‘S’

SUNDAY AFTERNOON

Wolfheze

Divisional troops (Urquhart) LZ ‘Z’

SUNDAY

Heelsum

3rd Ba alion (Fitch)

1st Ba alion (Dobie)

Polish heavy equipment

LZ ‘L’

DUE TUESDAY MORNING

SUNDAY

Main Road

GERMANS

GERMANS

2nd Ba alion (Frost)

Hotel

Hartenstein

KEY

Gliders

Paratroopers

Infantry

Armoured division

Allied movement

German movement

Supply Zone

Oosterbeek (THE VILLAGE)

Lower Road

Railway bridge blown up

SUNDAY EVENING

THE BRIDGE Pontoon

SUNDAY

1st Polish Independent Para Bde (Sosabowski) DZ ‘K’

DUE TUESDAY MORNING

Countdown: 24 hours to Black Tuesday

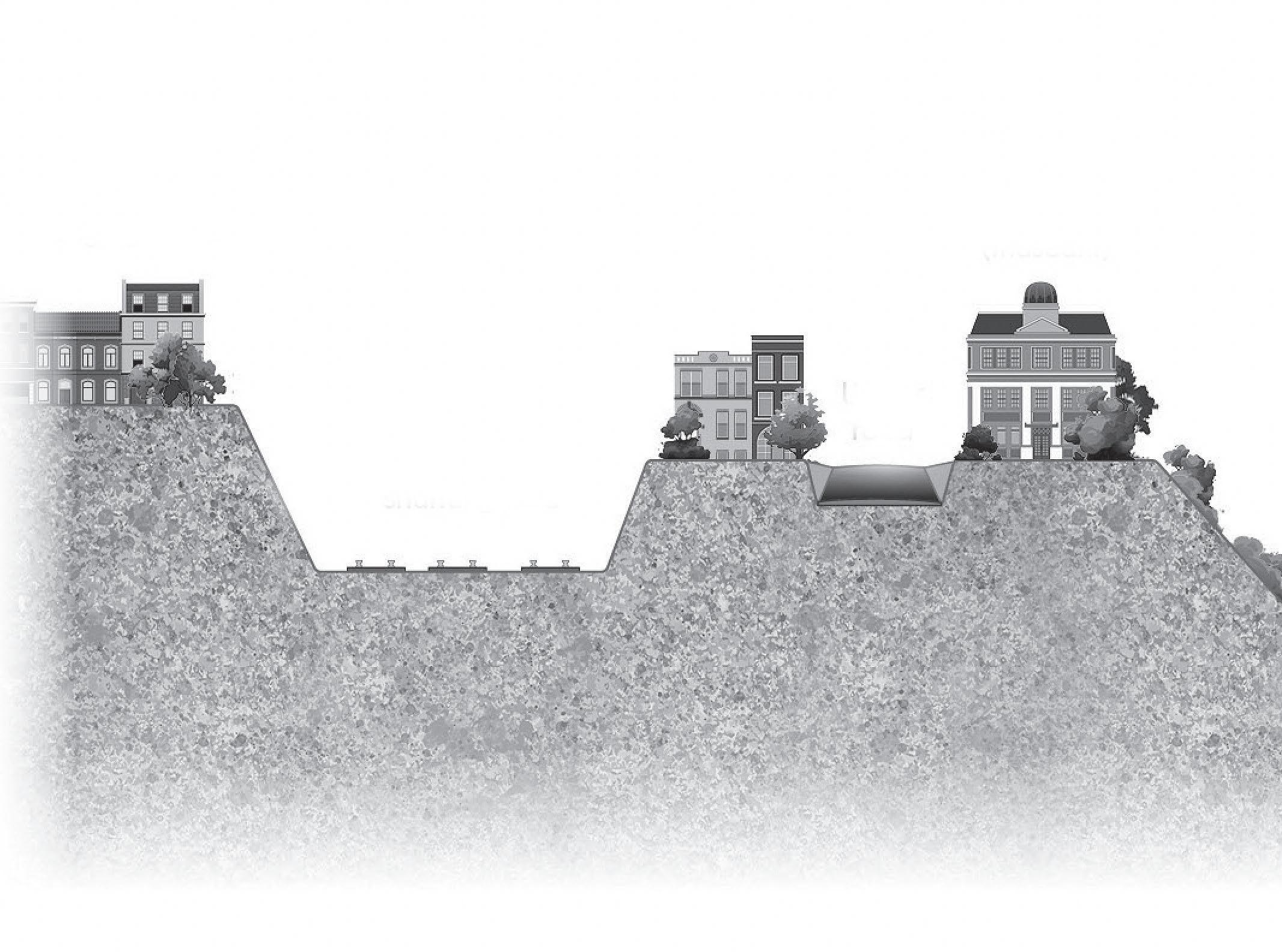

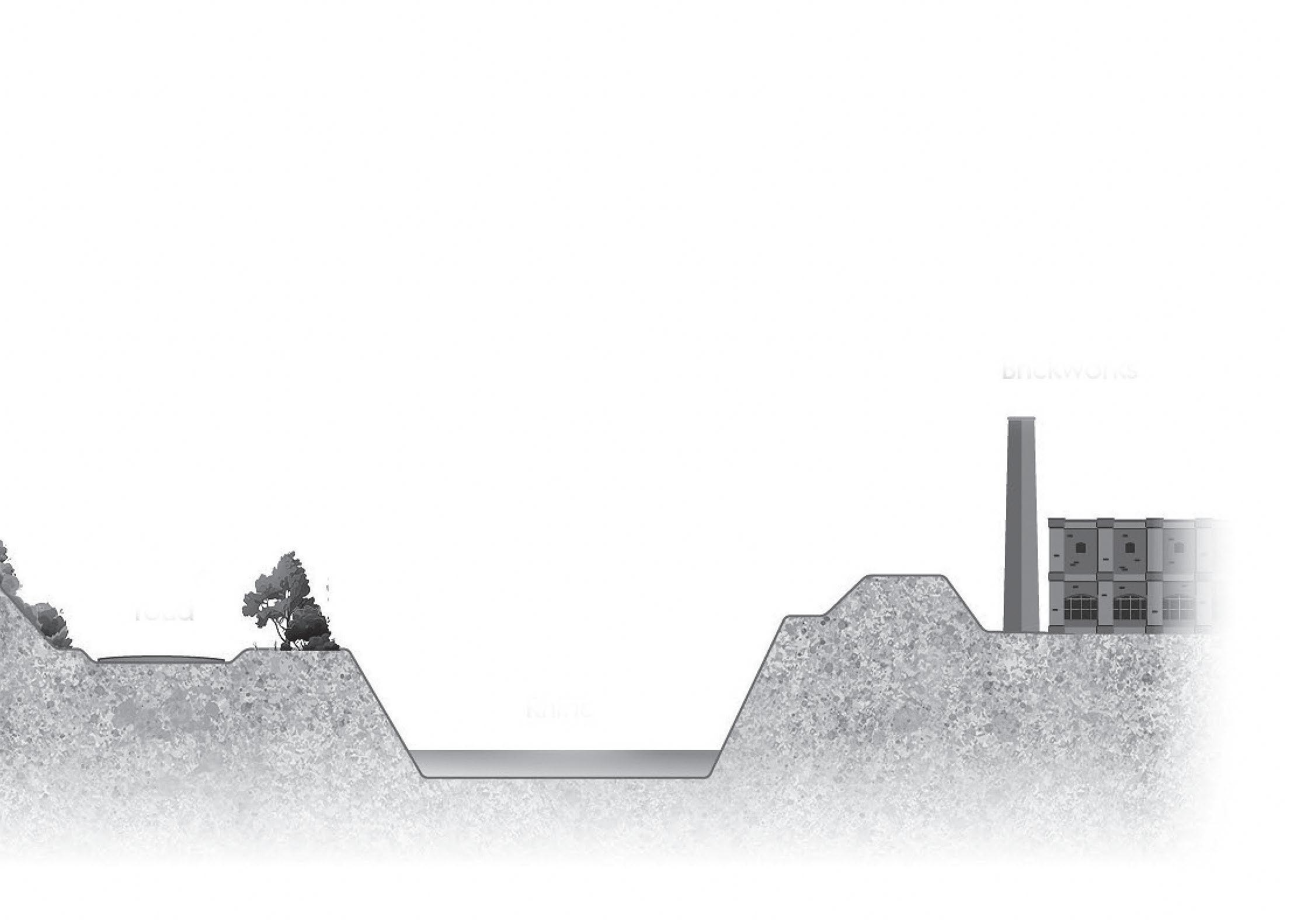

Level crossing at Wolfheze

10th Battalion

Although this is a modern aerial view, the underlying terrain is basically unchanged from 1944. Map base © Google

Dreijenseweg

5) 11th Battalion and South Staffs overwhelmed

6) Survivors retreat

Although this is a modern aerial view, the underlying terrain is basically unchanged from 1944. Map base © Google

THE LOFT

High ground

Monastery (Museum)

Upper road (Uphill slope)

Railway shunting yard

Below: German troops close in on The Monastery, the airborne men inside having no option but to surrender. Being captured was something few men had considered.

Brickworks

Lower road

Below: Self-propelled guns, panzers, armoured fighting vehicles: with the element of surprise that airborne landings relied on long gone, the German defenders held all the cards on Tuesday morning.

SCHOOL (Mackay)

GERMAN ATTACK

BRIGADE HQ

GERMAN ATTACK

SLIT TRENCHES

BRITISH DEFENCE PERIMETER

MORTAR PIT Pt. Lygo

BRITISH DEFENCE PERIMETER

BRITISH DEFENCE PERIMETER

This photo was taken on Monday afternoon. On Tuesday the area was contested all day long, and the positions were constantly changing.

HQ and Reserve

Continuous covering fire No 1 section

Initial covering fire No 2 section

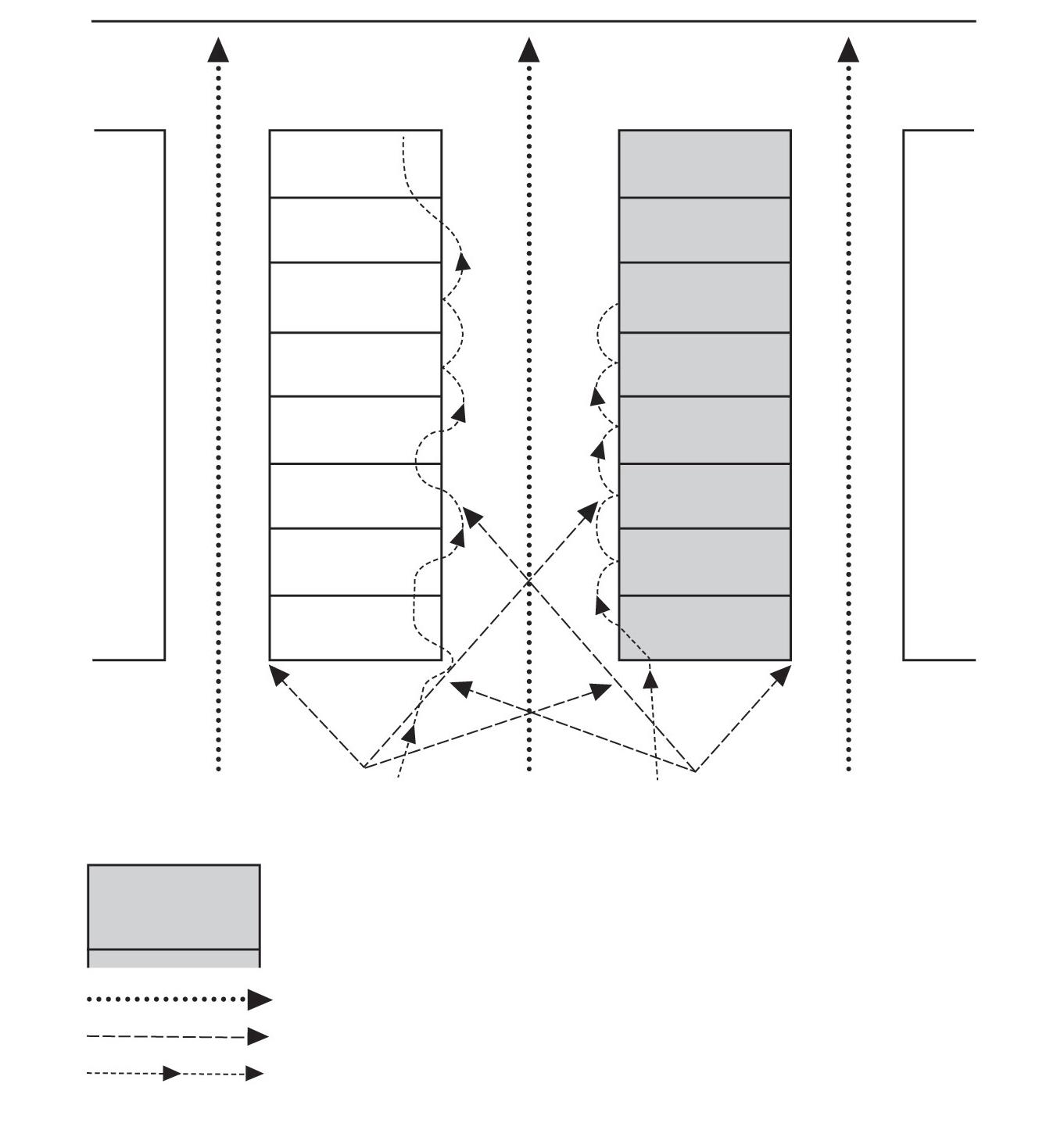

Street fighting was manpower-intensive, and, as the manual said, a three-dimensional space – the enemy might be upstairs. Every room of every house had to be cleared, and while every house offered cover, every open street offered clear lines of fire, every corner a new ambush. This diagram from the instruction manual for clearing one street makes clear the challenges faced by the battalions attacking in the Town.

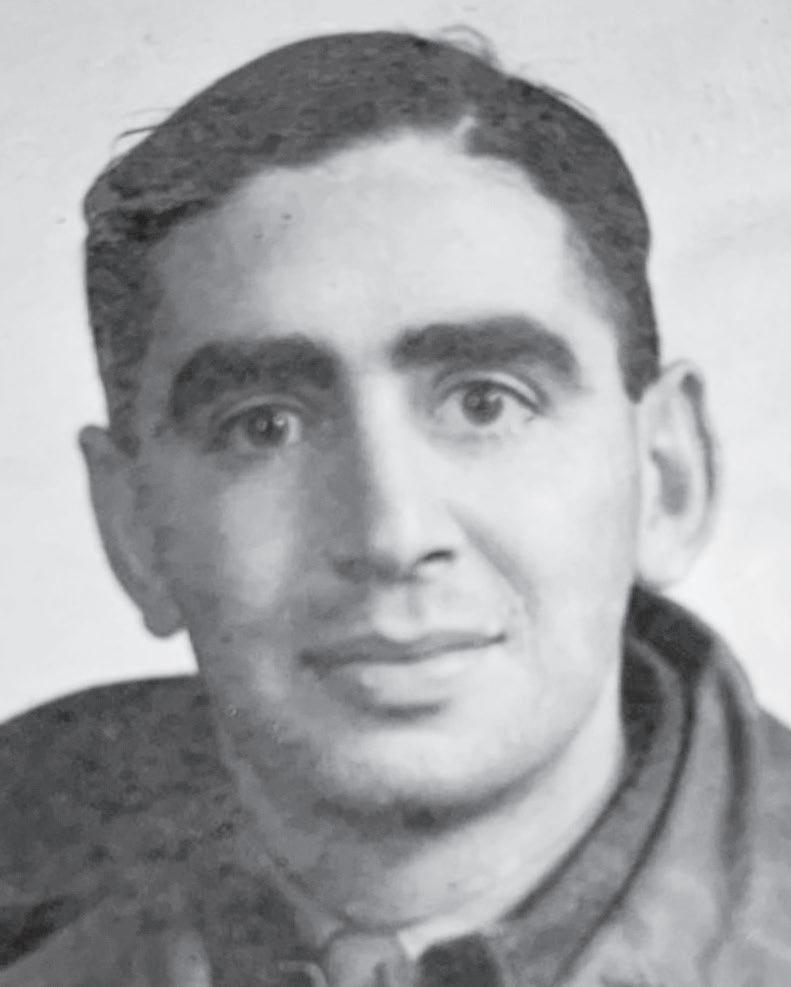

Major Robert Cain: in the desperate battle for ‘the Monastery’ and then at the high ground at Den Brink, Robert Cain of 2nd Battalion South Staffords did everything he could to keep the men together as the battalion was destroyed in the Bottleneck.

Bernard Egan

Egan was at the Bridge at Arnhem with Frost and his men. He was injured when the German panzers started to close in on the men at the Bridge on Tuesday evening and ended up in a cellar with the wounded he had been tending to.

Lieutenant-Colonel John Frost: here (centre) on his return from the Bruneval raid, Operation

unequivocally successful British airborne operation of

Brigadier John ’Shan’ Hackett: (centre) with his boss, Roy Urquhart, on his right and their boss, Monty. Smiles all round. Hackett was cleverer than those around him, and he and they knew it.

Captain Alexander Lipmann Kessel, RAMC: discovered firsthand German attitudes to the wounded that he found shocking but not exactly surprising.

Brigadier Philip Hicks: the most experienced man on the ground, ‘Pip’ Hicks kept his head down and got on with playing the poor hand he had been dealt.

Brigadier Gerald ‘Legs’ Lathbury: principal architect of the plan to take the Bridge at Arnhem which had misfired on Sunday and Monday. On Tuesday what was left of his leaderless Brigade would have to pick up the pieces.

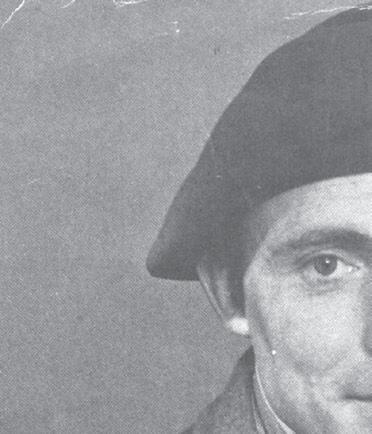

Captain Eric Mackay (right) of 1st Parachute Squadron, Royal Engineers, spent Tuesday fighting in and around the school on the eastern side of the ramp that ran north of the Bridge into the Town, ignoring a piece of shrapnel in his foot.

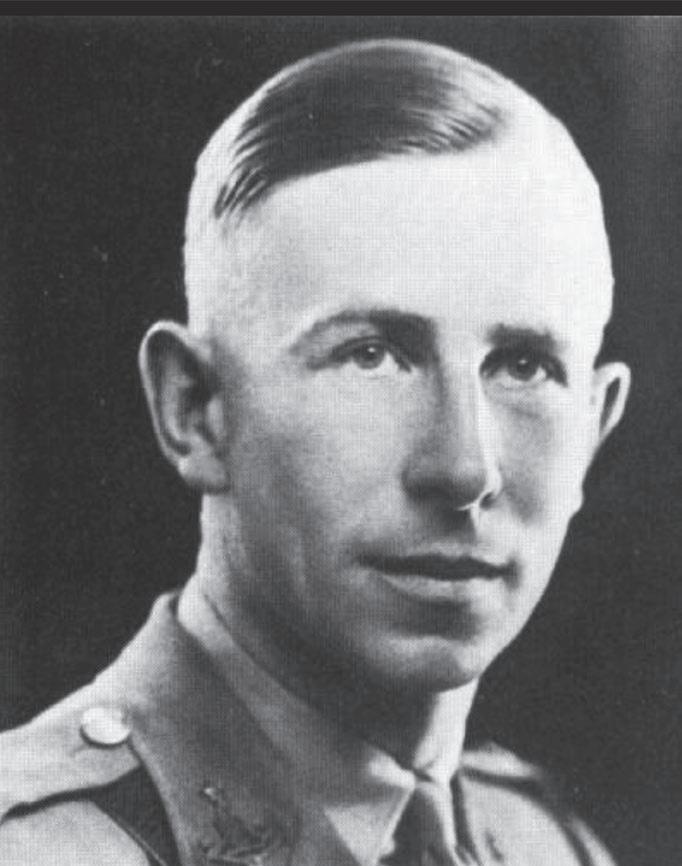

Captain Stuart Mawson, RAMC: Medical Officer with 11th Battalion. Stuart Mawson witnessed the aftermath of his Battalion’s disintegration on Tuesday, saying it was like men fleeing a forest fire.

Major Geoffrey Powell: fighting as a company commander in 156 Battalion, Geoffrey Powell witnessed the destruction of 4th Parachute Brigade first-hand.

Captain Lionel Queripel, of 10th Battalion. Queripel’s devil-may-care attitude in the battle in the Woods, crossing a road under enemy fire, smoking his pipe, was a source of inspiration for the men fighting on the Amsterdamseweg, even when events ran out of control.

Major General Stansilaw Sosabowski: (left) languishing in England, fog bound, his parachutists unable to go to Arnhem, Sosabowski’s Poles were at the back of the airborne queue. How Tuesday ran for the Poles could not have made this clearer. In this picture he is most likely fending off Lieutenant General ‘Boy’ Browning (right) attempting, yet again, to persuade him to cede control of the 1st Polish Independent Parachute Brigade.

Major-General Roy Urquhart: (right) once he had made it back to Divisional Headquarters at the Hartenstein Hotel, Urquhart could get on with making decisions and taking command. But had the die been cast?

The history of a battle, is not unlike the history of a ball. Some individuals may recollect all the little events of which the great result is the battle won or lost, but no individual can recollect the order in which, or the exact moment at which, they occurred, which makes all the difference as to their value or importance.

The Duke of Wellington

T HE B ATT l E o F Ar NHEM , Operation Market Garden, has been present in my imagination for as long as I can remember, a peculiar and powerful singularity.

I have been drawn to it almost my entire life. Writing about it has felt both inevitable and impossible. As I have sidled up to history as a parallel career, the time to grasp this particular nettle has snuck up on me. So much excellent ink has been spilt, by brilliant writers, amateur and professional historians alike (I’ll leave it to the reader to decide who is who). It is a battle that is talismanic and indeed dominant in the British post-war narrative about the final year of the Second World War in Europe, overshadowing other epic, shattering, bloody victories of the eleven months following D-Day. In contrast to the ruthless German Army crushing machine that the British Army had become in 1944, Arnhem offers a last stand, our last proper defeat of the war, and it casts an irresistible shadow for

anyone who wants to feast on failure, futility, heroism and drama at a time when the war was headed in only one direction.

Arnhem, of course, comes to most people via the movies, in a way that has become impossible to ignore. It is that rare thing, a battle that lives in the popular imagination. The extraordinary Theirs Is The Glory set the tone. It is perhaps hard to think of a stranger cinematic artefact: made on the battlefield itself in 1946, the burnedout tanks still present, vivid in black and white, using footage shot during the Battle alongside re-enactment, the players themselves veterans of the Battle. Then, in the 1970s, up against Star Wars came A Bridge Too Far, Richard Attenborough’s paradoxical anti-war movie that made gallant defeat seem so attractive, his camera feasting on the maroon beret glamour his panoply of stars offered him, a glamour that had been tarnished in that decade by more recent bitter events in Northern Ireland. With its gee-whizz can-do Americans, its steely Germans and a heavy helping of tea-drinking Brits, some of whom are awfully unhelpful chaps in the RAF, William Goldman’s screenplay set the popular narrative in stone. Chipping away at that narrative seems Sisyphean, but here we are.

The Battle came to me via my father. After his National Service in the mid-1950s, which came at a time of Imperial withdrawal and nuclear expansion, Dad stayed in the Territorial Army as a parachute engineer; he had an appetite for the challenges that being an airborne soldier offered. They played hard, they lived a life of adventure, and the sappers were ‘triple hatted’: soldiers, engineers, parachutists all at once. It’s the parachuting I remember, of course. His squadron practised jumping into the sea off Guernsey, so there were photographs and tales of that when I was a small boy (I suspect now, like so much of this kind of activity, it was an excuse for a jolly), and trips to see him jump from a balloon. I have a vivid, and no doubt embellished, memory of trying to help him with his reserve ‘chute’ by picking it up by its red handle and being told rather emphatically what a bad idea that was. I’d have been fired across Salisbury Plain by its spring. But Arnhem was part of this picture; officers Dad knew,

such as Eric MacKay, had been at Arnhem (as well as others who had fought in Normandy, of course), and one of his NCOs in his TA establishment had fought at the Bridge.

So we went to see A Bridge Too Far. I remember the crashes and the bangs, the utterly mind-blowing scenes of the parachute landings, done for real, en masse, but I also remember his niggles with the film: wrong tanks, actors’ haircuts, rotten saluting, the mischaracterization of people he knew and events he’d heard about first hand. But I was bitten by the Battle’s bug. It became a subject to return to again and again, and something we could and would discuss ad infinitum. We don’t do football, see? For my O level I produced a project about the Battle of Arnhem, even visiting the National Archive (or Public Record Office as it was then, presenting a letter from a history teacher as a reference on arrival) where I read the War Diaries. We visited Arnhem on the road from Wolfheze into Oosterbeek where I drank a delicious cold cider – that memory has stuck – and was almost run over by a moped in the cycle lane by the Bridge, a place offering fresh danger forty years after the Battle. Each new book that appeared would get the once-over. Each time I’d find myself willing on the men of 1st Airborne to succeed this once, and each time I’d be disappointed.

When Dad retired, I suggested that he write about Arnhem. This got short shrift: there’s nothing new to be said, he said. I found it hard to disagree. And yet, new scholarship emerges, time passes, and fresh perspectives force their way forward, even though the nine days’ fighting of the Battle tends to force all accounts of it into the same shape. Once the struggle at the Bridge has ended, the Battle in the Oosterbeek Perimeter becomes a British Alamo, and amidst the endurance, sacrifice and suffering, an echo of repetition and fatalism emerges. So now, in writing finally about Arnhem, how does one avoid these patterns? How can the story be approached afresh?

After all, one of the attractions about the Battle is that it was short and relatively contained. It has this in common with D-Day, the celebration of which often overlooks the ten weeks of savage

fighting that followed it, as well as the months of naval and aerial battle that prepared the battle space. The Battle of Arnhem occurred in a contained area too – while the Drop Zones and Landing Zones may be ‘too far’ from the Bridge, you can cover the distance in an afternoon, and take in most of the key locations along the way. The shape of the place now is essentially as it was then, the relatively new road bridge in the Town notwithstanding. And 1st Airborne’s ten thousand or so men is a reasonably finite number of people to keep track of, at least compared to the numbers involved in the colossal actions in Normandy which preceded it and the vast offensives that followed. The Battle’s fame has helped it to be well recorded and remembered, and narratives from the men as well as their officers, whose versions of events have tended to dominate the story, are plentiful, abundant even.

So what is your author’s approach, and how have I arrived at it? To try to say something new, or perhaps, better put, something else, about the Battle of Arnhem, I am going to focus on one day, Tuesday 19 September 1944, and the Battle that was fought by 1st Airborne Division and 1st Polish Independent Parachute Brigade, as well as the RAF troop transports, who were as much a part of that effort as anyone else. 30 Corps, 101st US Airborne Division and 82nd US Airborne Division, and their efforts to the south to make sure that 2nd Army reached the Rhine at Arnhem, do not feature.

Why? Well, because what I’m hoping to do is place 1st Airborne’s experience on the Tuesday in its own context: they had no idea what was happening to the south, all they knew was that the relief they expected by Tuesday had not materialized. They didn’t know the ins and outs of what was happening; it was an unknown over which they had no influence. Battalion commanders, Battery commanders and brigadiers see only as far as their battalions, batteries and brigades can see – if they’re lucky, and luck was something in short supply at Arnhem. So in this book we don’t see what lies beyond, because they couldn’t see it. Similarly, the Germans and the decisions they were making were opaque to the British. Whatever

decisions General Model made are felt in terms of their consequences rather than explained to the reader, because again, the men in Arnhem had no knowledge of those decisions, only the immediate consequences of them.

Furthermore, I want to try to avoid some of the fatalism and hindsight with which the Battle is inevitably freighted. What will happen next? How are the decisions being made on the day, and the potential pitfalls of an airborne landing, to be brought back to life without my solemnly declaring that everyone should have known better, that the Landing Zones selected were too far from the main road Bridge in Arnhem, and so on? Men may have known, and even said so at the time, but there’s little doubt they felt the risk was worth it. Certainly getting there and holding the Bridge would have felt well within their capabilities.

On that Tuesday, the inheritance of what had gone before in airborne operations played itself out. North Africa, Sicily, Normandy: these are the key to so much of the Arnhem story. The anatomy of 1st Airborne Division, its muscles, its sinews, its eyes, its ears, its brains, all were tested to their very limit on Black Tuesday. To investigate this anatomy means we will have to leave Arnhem and look at their origins and evolution, but I’ll try to do that in the context of how they were understood at the time. These rabbit holes, or digressions, are, I hope, the body of institutional memory, such as it was, that the men at Arnhem carried with them, which subsequently informed how the day went.

To try to express this I have decided to create my own convention for how to discuss the Battle, and divide it into four locations, and avoid place names and street names. Indeed, in the orders for the operation, street names were substituted with British street names; the Arnhem to Ede road was dubbed Ermine Street, for instance. The fighting happened at the Bridge, in the Town, where 1st Parachute Brigade did all it could to reach the Bridge, the Woods, where 4th Parachute Brigade did what it could to flank the Germans and get into the Town, and the Village, Oosterbeek, where 1st Airborne

Division had set up its headquarters and Divisional Administrative Area. We will go to England and elsewhere from time to time, but these four areas will serve as our primary locations. Many of the men present weren’t as familiar with the street names and locations on maps as later historians have become. Not everyone had a map, and some of those who did could not read them. Main roads were ‘main roads’ rather than the Utrechtseweg. This cannot be a hard and fast rule, but it feels true to the chaos of the day. Furthermore, although this is an account of one day, it is necessarily incomplete, the way anyone’s picture of the day would have been. This was perhaps a choice between a slender volume or the world’s biggest doorstop volume. I know on your e-reader this is a difference of nano-microns, but I wanted Arnhem: Black Tuesday to be a manageable read.

The day itself I have divided into four easy quarters, Midnight, Morning, Afternoon and Evening, and while events do not naturally conform to any such tidy schedule, I have tried to keep the narrative as close to the chronology as possible. One challenge is that Black Tuesday was a procession of relentless ‘Meanwhiles’. Three o’clock on the afternoon of 19 September 1944 may not have been the day’s climax as such, but everything was happening everywhere, all at once.

To explain where everyone starts on the Tuesday at midnight I will necessarily have to report what happened on Sunday and Monday. What happened on Black Tuesday was about so much more than the two days that preceded it. The shape of the book tries to reflect this: the storm passes, night falls, and the men brace themselves for whatever is to come. Incredibly, one of the units in this story has what could be described as a quiet day on 19 September 1944. What happened to them thereafter is another story.

The experiment of looking at a single day does not change the core element of the story of the Battle of Arnhem. The men of 1st Airborne Division and their Polish comrades fought with extraordinary tenacity and courage, and while the Battle attracted five