‘This book changed my life’ Elizabeth Day

Psychotherapist and co-host of the Best Friend Therapy podcast

Discover the Four Blind Spots That are Holding You Back, and How to Overcome Them

‘Beautifully observed, insightful and validating’ Julia Samuel, psychotherapist and author of Grief Works

Emma Reed Turrell What am I Missing? am I

What am I Missing?

What am I Missing?

Discover the Four Blind Spots That are Holding You Back, and How to Overcome Them

Emma Reed Turrell

PE NG UI N LI FE a n i mp ri n t o f

ng ui n boo ks

pe

PENGUIN LIFE

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia

India | New Zealand | South Africa

Penguin Life is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com.

First published 2024 001

Copyright © Emma Reed Turrell, 2024

The moral right of the author has been asserted

Set in 12/14.75pt Dante MT Std

Typeset by Jouve (UK), Milton Keynes

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The authorized representative in the EEA is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin D02 YH68

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

isbn : 978–0–241–62498–2 www.greenpenguin.co.uk

Penguin Random Hous e is committed to a sustainable future for our business , our readers and our planet. is book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper

To my parents, Ingrid and Keith

Contents Introduction 3 1. Blind Spot Therapy 17 2. The Profiles 32 3. What am I Missing in My Family? 56 4. What am I Missing in Friendships? 92 5. What am I Missing in Romantic Relationships? 132 6. What are We Missing as a Couple? 163 7. What am I Missing at Work? 209 8. What am I Missing about Myself? 250 Conclusion 306 Acknowledgements 315 Notes 317 Index 323

Introduction

When people come to therapy, there’s usually a piece of the puzzle that they’re missing. They’re anxious or depressed but they can’t put their finger on why. A conversation with a friend or relative has really thrown them, and they can’t figure out why it bothered them so much. They keep coming up against the same issue at work, or they find themselves having the same arguments at home, and they’re at a loss as to what to do about it.

My job as a therapist is to help them notice what they haven’t spotted yet, to find out what else might be going on and what patterns are at play, and to look for the common denominators in the dilemmas they face. To help them answer the question ‘What am I missing?’ and make sense of their situation in a way that means they know what needs to change. My goal is to increase their awareness and their insight so that they can reassess their options and make more conscious decisions that will get them closer to the results they want – whether that’s to build healthier personal relationships, be more successful at work or become the parent they want to be to their children. I do this by asking different questions, ones that they might not have asked themselves, and by examining the edges of their world for information that lies outside their direct line of sight. I’m looking for the thoughts, feelings and beliefs in their peripheral vision that may be the cause of their repeating challenges but have so far gone unseen. These areas of patchy awareness are their ‘blind spots’ – assumptions and shortcuts that drive their daily lives but are based on fiction not fact, or on the past rather than the present. Once we know what we’re missing, we can see the bigger picture and work out what to do. And that’s what I want you to get from this book

3

What am I Missing?

too. To finally make sense of the blind spots that have been getting in your way, to give you the tools to better understand them, where they came from, how they show up in different areas of your life (because the way we are with our friends, family and colleagues are very rarely the same, for good reason) and, most importantly, show you ways that you can start to overcome those blind spots, put things in perspective and live a more authentic, happy and fulfilling life.

Although it might sound like a daunting concept, we all have blind spots in our awareness. It’s a design feature of the human brain to bypass slow processes of cognition, speeding up our responses by coming up with a best guess or a prediction based on our previous experiences. To demonstrate how this shows up in real people’s lives, I will take you through the case studies of my clients who came to understand their blind spots, learned how to see things as they really were and left with a clearer idea of how to move through life freely and more wholly. It will guide you through the questions and techniques they used to view situations from different angles so that you can fill in your own blanks and understand why you act the way you do. In a world where we understand the value of therapy but are not always able to access its benefits, this book will give you the tools to see what you’re missing and feel empowered to take the next right step for you.

If you have ever listened to my podcast ‘Best Friend Therapy’, co-hosted with Elizabeth Day, you will already be familiar with the truth bombs and lightbulb moments that come out of our conversations, and how I make therapeutic practices and theories accessible in a way that enables listeners to apply them to their own lives and reap the rewards. My aim is that this book offers the same combination of compassion and common sense – I hope that by offering the insights that I’ve learned over the course of my career as a therapist I can enlighten, empower and equip you to design a more fulfilling, authentic and happy life for yourself.

4

What am I missing here?

This is the question that I’m asked by clients every single day. It’s the starting point of every therapeutic journey and is crucial to every client whatever their issue, background or demographic. It’s the one that unlocks our understanding and helps us put things into perspective. To answer it, I’ll usually start by explaining how our awareness works.

At the back of the eye, there is a small circular area where the optic nerve enters the eyeball. Here there are no photoreceptors, no light-detecting rods and cones to pick up the light and convert it into images. This part of the field of vision is rendered invisible, and we call it a blind spot.1 In everyday life, you’re likely not to notice you have one because your brain fills in the missing information – you can’t see the whole street as you walk down the pavement, but you know what’s there, or at least what to expect, so your brain fills in the gaps for you.

The truth is, although we place a lot of importance on the validity of our vision and use phrases such as ‘plain as day’ or ‘crystal clear’ to argue how confident we are in something, the information that our eyes feed to our brain is only half the story. Even if you can see what’s around you, your brain won’t necessarily rely on your eyes for its understanding. Our senses are slow and, by the time we’ve converted an image into information, the snapshot is often out of date. We’d never hit the ball if we reacted only to what we saw; we’d be less coordinated and more likely to get hurt if we relied upon our sense of sight. Instead, our brain predicts a path of motion before it happens, it tells us a story about where the ball is heading, and this story becomes our reality. We strike based on a prediction and not the real-time feed.2 Likewise, hearing is contextual, and our brains will re-hear sounds up to a second later, returning to fine-tune our original understanding like an auditory autocorrect.

Introduction 5

What am I Missing?

Your brain’s ability to infill, predict and reframe is an evolutionary advantage to a biological system. In the wild, it’s safer to run on recognition than to take a second look.

Your brain fills in gaps with perception, not reality.

You this read wrong.

Your ability to read jumbled words comes from your brain’s recognition of sequences, rather than a clunky requirement to read letters. It allows you to skip over individual mistakes and read the the whole sentence (without noticing ‘the’ repetition).

Bombarded by 11 million pieces of information every second and having only the mental capacity to process around forty, 3 your brain relies on perception to run you on autopilot, finding patterns and predicting outcomes, to make 90 per cent of your decisions without you ever realizing you’re even making them.

Presented with these numbers, 2 – 4 – 6 – 8, which of the sequences below do you think follows the same pattern?

2 – 7 – 19 – 25

12 – 14 – 16 – 18

11 – 27 – 44 – 63

If you, like most people, identified that the numbers in the first sequence all increase by two, you might have suggested the middle sequence as the match. But what if I told you that all three sequences follow the rule?

Because the rule is simply that the numbers increase.

You needed more information to accurately identify the pattern, but your brain took a shortcut and, just as we can apply the wrong rule to a number puzzle, so we can apply the wrong rule to life. Our senses can be distorted by prediction and context, and so can our beliefs.

6

Mental gymnastics

Without all the facts, we can’t see the complete picture and we’ll jump to conclusions from a glimpse – a stick can be mistaken for a snake, or we’ll assume that there’s no smoke without fire – and when it comes to relationships, we can be equally quick to perceive someone’s actions as something they aren’t. Whether it’s drawn from shorthand or out of ignorance, our reactions can lose objectivity and become disproportionate. When my daughter suffers a bee sting during a handstand, in the wrong place at the wrong time, it could mean that she avoids doing gymnastics for the rest of the summer, and subsequently the rest of her life. Her fight-or-flight system flares when it’s time for PE and she must talk herself down to perform her cartwheels. My son has only to look at a car to feel travel sick. These are the automatic reactions of a nervous system that uses prediction to protect us.

Our nervous systems make unconscious inferences all the time, never conceding, ‘Look, I’m only guessing here.’ But we’ll have more than a fear of bees or car journeys to contend with when these primitive processes are left in charge of core beliefs and life-changing decisions. Just as your brain will predict the path of an object, so will it predict the path of a conversation, a relationship or a career, if we let it. In a bid to minimize surprise, your brain will screen out material that might be contradictory or unpleasant and direct you down a tunnel of assumption and snap judgement. When your vision is blurred by blind spots, you might not see someone for who they really are, or you might fastforward new scenarios to the familiar but unhappy conclusion you expect.

Take the example of a new job. Your brain can tie together snippets of information about a person you’ve just met and, using generalizations, present you with a best guess and a forecast for the future. Helpful when you’re assessing a new environment,

Introduction 7

but what if the mannerisms you see in your boss remind you of a critical parent or a bully from school? You might find yourself putting two and two together and making five. Your brain fires off a prediction of attack that becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy, and the resulting anxiety prevents you from being effective in your job. You quit or get fired, but it wasn’t your boss making life difficult, it was your blind spot.

Switching the light on

I see the results of blind spots in my psychotherapy practice every day. The husband who gaslights his wife and capitalizes upon her susceptibility to illusory thoughts. The worker paralysed by imposter syndrome, founded in a fixed but false sense of incompetence. The couple caught in a toxic relationship, prioritizing familiarity over fulfilment. Clients often come to therapy when the picture their brain presents is causing them problems, leading them to make the same mistakes or to uphold a critical view of themselves that is holding them back. They feel held back by anxiety or flattened by depression, perpetually in the wrong relationships or frustrated at work. These are the people who feel lost or trapped, unable to see a way out by themselves when the escape route is hidden by a blind spot.

For most people, the impact of their blind spots thankfully isn’t as pronounced or extreme as these examples, which is perhaps why you picked up this book, as a starting point before seeking therapy to find an answer to something that has been niggling you. It might be that you aren’t looking for any answers and are just curious about the therapeutic process or learning more about what is going on underneath the surface for you and your loved ones. Wherever you are on your journey right now, my aim is that the insights in this book will help flick a switch in your brain and enable you to see things in a new light and reach

8

What am I Missing?

the therapeutic goal: perspective. Regardless of where my clients are coming from, what their symptoms are or what profile they fall into (more on that later), my aim is to help every single one of them to remove any obstructions and view their lives with true, unfiltered perspective – and now that includes you too.

case study

Alison

Alison was a client who came to therapy because she felt there was no other option. A tireless and uncomplaining social worker in her forties, she had never been to therapy before (she told herself this, too, was self-indulgent) but now she was suffering from debilitating panic attacks and, despite her best efforts, focusing on the positives was not making the negatives any less overwhelming. From our first meeting, I could see that her low self-worth was getting in her way; it had stopped her making changes in her life and left her feeling anxious, but, for things to be different, we needed to know what she’d been missing. She told me that she felt unseen at work and taken for granted by her bosses, but also that she shouldn’t expect attention and didn’t believe she was important. Her recent panic attacks had brought her into therapy but, when we dug a little deeper, we saw that life had been like this for as long as she could remember and she had a blind spot that was hiding her self-worth and encouraging her to sacrifice her own needs as a result.

As the eldest child, she had looked after her younger brothers, bathing them and helping them with their homework while her parents ran the pub downstairs and drank with the locals after hours. Social expectations had reinforced a traditionally female role of care and compliance in the household and her father’s quick temper meant she automatically assumed

Introduction 9

What am I Missing?

the blame whenever there was conflict. As an adult, she still gave others the benefit of the doubt, but, having worked on the front-line throughout the pandemic, she found herself weary and disillusioned. Budget cuts and politics had brought her to the end of her tether, and she felt unable to let things slide, as she always used to.

A few weeks into our work, I asked her: ‘So, why do you think your parents asked you to take care of your brothers? Why do you think your bosses ask you to take on the cases no one else wants?’

‘Because I’m the only mug that will do it?’ she said, smiling, before continuing, ‘And they always said I was good at it, my parents I mean, they said I had a wise head on my shoulders, and they trusted me. That felt good at the time. Come to think of it, that’s what my bosses tell me now: they know I can handle whatever’s thrown at me. Which is true, I suppose, but it doesn’t mean I want them to keep throwing it!’

‘So, you’re good at it, that makes sense. But why else do you think they asked that of you?’ I pressed.

Alison looked at me blankly, so I offered her an alternative view of events.

‘Is it possible that it suited your parents to overload you with responsibility? That it met their needs to be downstairs working, or drinking, while you took care of their kids? That it meets your bosses’ needs now to dump tough cases on you and get the problem off their desk?’

‘Maybe.’ Alison thought for a moment. ‘But that would mean it wasn’t about me, and whether I was good enough or not. That would mean it was really about them, and the problems they needed me to solve.’

That’s what she’d been missing. Her blind spot had hidden the possibility that her worth was not in question, it was the way others had chosen to value her. She was of high value but zero worth to the people she’d supported, prized for what she

10

could do for others without being of importance herself. Her resilience had been encouraged when it had suited others, but she had lost her identity in the process.

Over the weeks to come, Alison had to come to terms with the uncomfortable information that her blind spot had concealed for decades – the mistakes her parents had made in the past, the bosses who were mistreating her in the present, and the resentment that she harboured on both counts. Over the course of our conversations, she came to see things as they really were and reclaimed the self-worth that had been out of sight. She raised her complaints with her managers and put the wheels in motion for some changes at work that would protect her, as well as the clients she supported.

Alison had prejudged people and situations, based on her blind spot. It meant that she expected to be an endless support to others and gravitated towards relationships and situations that would undervalue her and reinforce her already low selfesteem. Her brain, like ours, was less concerned with finding fulfilment and more focused on continued survival, and there was a certain safety in the familiarity and predictability of relationships similar to those she grew up in and knew best.

We use the past to forecast the future and knowns to predict unknowns, even when those past experiences were clouded by their unique context and were likely subject to the blind spots of others. Viewed in isolation, these scraps of understanding, gathered from moments of subjective internal interpretation, can’t usefully serve us and our brains as a foundation upon which we can build beliefs and make decisions. Regardless, it is this patchwork of patterns and preconceptions, with all its inherent blind spots, that paves our way through life, even when the events it’s predicated upon might seem small, insignificant or misunderstood to our objective, adult selves. If we don’t stop to question our beliefs or behaviours, these prejudgements, based on fragments of information or hearsay,

Introduction 11

What am I Missing?

can go on to inform whether we expect to succeed or fail in life, whether we’ll rely on others or must go it alone, whether the world will be a place of hostility or hope. Just as Alison discovered, this therapeutic process is exactly that: therapeutic, and not self-indulgent. If we don’t stop to look back, we will continue to move forward in the dark.

Prejudgement versus judgement

Unconscious assumptions born out of blind spots can guide our life choices without us ever knowing. I’m no exception. University was an unhappy time for me, and I concluded that I wasn’t cut out for academia. I assumed that I was the problem, that I didn’t have what it took and I wasn’t smart enough to keep up with the others. In the years that followed I avoided reading altogether and wouldn’t dream of voicing my opinion in public. Eventually I found my way into therapy as a client and got hooked on the psychology of what makes us tick. I enrolled for a degree in counselling, this time on my own terms and in a subject that I was passionate about, and realized I’d been wrong about myself. I wasn’t the problem; it was an archaic institution, riddled with its own blind spots, that had failed me.

If we don’t go back and check out our assumptions, bringing objectivity, agency and awareness to this process, we risk delimiting our own lives and slamming the door on every challenging experience. We’ll miss the opportunity to do gymnastics wherever we want, self-sabotage our relationships and bring unconscious bias into our homes and workplaces. We’ll fall back on prejudgements to keep us safe, yet find they only keep us trapped. And the more frequently we gloss over our blind spots, the more deeply ingrained they’ll become, until we convince ourselves we see things clearly while everyone else is in the dark.

12

Previously, Alison had tried to get by on kindness, never judging others for fear of getting it wrong or causing offence. But, while judgement is often considered a negative trait in our society, we risk greater damage when we opt out of making our judgement conscious. Staying silent doesn’t resolve our differences, it just drives the discussion into the dark, where no growth can occur and no change can be made. Each week, Alison practised the skills she would need to become a more reliable witness in her own life, and left, some months later, a better judge of character with a clearer sense of self and healthier boundaries at work.

Assuming the worst or hoping for the best, ignoring red flags or ruling out change, might avoid conflict, but it also makes you a bystander in your own distress and, perhaps, even an accomplice at times. So, in a world where you can be anything, don’t be kind, be responsible, and, when it’s time to pick a side, be sure to look from every angle first. Judgement – of the enlightened, informed, accountable variety – is the antidote to prejudgement and the remedy to blind spots. My aim is that this book will show you how to uncover your blind spots, like Alison, to shake off those shackles that have been weighing you down, step into the rest of your life with your eyes wide open and to enjoy it, fully and freely.

Blind spots

Blind spots are fast becoming the central topic of conversation I have with clients in therapy. It has become the therapeutic lens I look through first, when faced with anyone who knows there’s a problem but can’t quite make it out. It all starts with one essential question that opens our minds to the possibility of multiple perspectives and new alternatives. What am I missing? To help you answer that question for yourself, I will share the stories of clients who took a closer look at their own blind spots, to discover the

Introduction 13

limiting beliefs that were holding them back and the blinkers they bore without realizing it. I describe how they learned to trace their blind spots back to their beginnings, how they gained insight and gathered alternatives, and how they began to move forward with their eyes wide open. However, to maintain confidentiality, their names and identifying details have been changed and any similarities to individuals are purely coincidental.

In my fifteen years of clinical practice, I have observed the four most common blind spots among my clients and developed them into ‘profiles’ to help identify their characteristics. These are the four typical ways that people act based on the shortcuts or blind spots that their brains have formed, each named after the way in which these manifest in their life: the Rock, the Gladiator, the Hustler and the Bridge. In the chapters that follow, I will offer you the opportunity to recognize your own blind spots, as well as those of the people around you. Through the different profiles, the way they form and how they impact us today, we’ll explore the biased relationships we develop with ourselves, others and the world, and tackle some of the common issues they create – from imposter syndrome to addiction, burn-out to co-dependency.

By the end of the book, you will have the means to recognize your own blind spots and the blind spots of others. You will see how your blind spots lead you to behave differently in different scenarios. You will understand why you hit the same brick walls, why other people around you get the wrong end of the stick, and how blind spots can come together to create friction and confusion in your personal and professional relationships. You won’t always like what you see, but at least you’ll know what you’re up against. And a series of reflective exercises will shine a light on what you need to do differently to resolve conflict, build healthy relationships and make decisions confidently – to live a life that feels intentional and fulfilling.

14

What am I Missing?

What are you missing?

Mental plains.

I use a visual image with clients to explain the way our brain struggles to let go of old blind spots and why our brain can sometimes make it hard to see what we’re missing, especially when we’re used to reading the story as it was written for us.

Imagine your mind as a wide, open plain covered in tall grasses. In order to connect a thought, we must cross from one side of the plain to the other, and our brain is designed to look for the easiest route. This will be one that we’ve travelled along before, so the grasses will be flattened and the route will be unobstructed. Our brain crosses at that familiar thought, and each time it does, that route becomes the most obvious way to go.

Many of you will be familiar with the practice of mindfulness, which teaches us to separate ourselves from the content of our thoughts and notice them as mental events that are happening to us but are not the same as us, to recognize thoughts as thoughts, not facts. When we want to change a repeated, intrusive or unhelpful thought pattern, we must notice our mental plain and see how easily our brain could send us across that tried-and-tested path. And how we have the ability to bring ourselves back to the start and notice other options, other pathways that we could take. We might have to push through the long grasses and feel the resistance at first, but in time, if we can keep bringing ourselves back to the beginning and take a single different step, we will begin to create other routes, ones which suit us better and get us closer to what we want. It will be tempting to jump back into the thought ruts that we’ve trampled down for years, but if we resist their pull for long enough, those grasses will grow back up and over, and the old paths will no longer look so compelling.

Introduction 15

The good news, I tell clients, is that we’re not trying to find the next path, the right path, or the best path. To begin with, we’re just looking to take a single step on any path other than the old faithful one we zoom across. We want to first become open to the existence of other paths and other thoughts and allow the original path to blur just a little. Once the existence of alternative possibilities exists, we’ll be able to explore which ones feel like good options for us now. It isn’t easy to break new ground and walk a different path, but your future self will thank your present self for gaining perspective and putting you on track to a happier, healthier destination.

Fresh perspectives

You may have noticed that I’ve used the word ‘perspective’ a few times now, and while it might sound appealing to some of you who have come to this book feeling like you are struggling to see things clearly, it might sound fairly innocuous to those of you reading this from a place of curiosity rather than concern. However, the reality is that ‘perspective’ is the unsung hero of our mental wellbeing. Whether we realize it or not, our judgement is constantly being clouded by our life experiences, and these compound year after year to become roadblocks that prevent us from getting where we need to be. The purpose of doing this work, of sticking our head above the parapet, is to see what is going on, to get the perspective that will reveal what we’ve been coming up against, and how to navigate through it. That’s why I refer to it as our therapeutic goal – the more we work through our blind spots, the closer we get to achieving that complete, true perspective. More on this later, but before we look at how to heal, let’s look at how to identify the ways in which your blind spots might be affecting you.

I Missing? 16

What am

1. Blind Spot Therapy

Clients often arrive in therapy with a definition of the problem. They tell me they are unhappy in their relationship, overwhelmed by grief, stressed at work, or struggling to sleep. This much they know, but they don’t yet know why. They don’t know why they’re affected this way, why it keeps happening, or why they can’t seem to change the situation. I developed blind spot therapy to help them answer these questions, to explain the patterns they repeat and uncover good reasons for bad feelings. In this way, by directing them behind the symptoms towards the cause, we reveal the autonomy and agency they need to heal.

The creation of subjective reality from an individual’s perception of events was introduced as cognitive bias 1 in 1972 by psychologists Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman, and has explained the way humans make decisions and judge situations in terms of mental shortcuts which offer estimates and assumptions about unknown outcomes. Much work has been done since to understand unconscious bias and implicit stereotype,2 as defined in 1995 by psychologists Mahzarin Banaji and Anthony Greenwald, whose research on implicit memory suggested that a past experience can influence future responses, even without our explicit memory of the event. Unconsciously, we store experiences and distort later aspects of reality in order to screen out difficult or divergent information, maintain the gaps in our awareness and preserve a perspective that’s familiar and predictable.

While working with organizations to understand the potential impact of unconscious bias on their employees, I became curious about how these mental shortcuts are formed in the first place

17

What am I Missing?

and, underpinned by the psychoanalytic theories of transactional analysis, I sought to develop a new way of working with clients in my private practice that could shed light on the unconscious bias at play in their daily lives. I called it blind spot therapy.

In blind spot therapy, I help my clients to fill in the gaps in their understanding with all the information they’ve been missing, leaving no stone unturned in order to do so. It’s important to pay close attention to the assumptions they’ve made, the context they’ve lived through and the identity they’ve been allocated. With a more complete package of awareness, they can say, ‘OK, well, that makes sense. I make sense. Now what?’

When we can understand our reactions as normal responses to abnormal situations, we free ourselves from the internal tension and confusion that keep us stuck and spinning our wheels. No longer at odds with parts of ourselves, we can believe what we see and control how we act in a way that is true to ourselves and live with the courage of our convictions.

‘ When we can understand our reactions as normal responses to abnormal situations, we free ourselves from the internal tension and confusion that keep us stuck and spinning our wheels. ’

Why blind spots develop

A blind spot is an area of low or no psychological awareness, a black hole into which unfamiliar or unexpected information disappears, even when that information is reasonable or relevant to the actions we need to take. When we’re missing the alternatives, we end up doing what we’ve always done and getting what we’ve always got.

18

Our brains form blind spots to make our worlds more predictable, to manage our expectations, to save us time and energy and, in a sense, to protect us from danger and disappointment. There’s less chance of my daughter being stung by a bee if she doesn’t do handstands on the grass, so her brain lets her believe it’s not a risk worth taking, while the relatively low odds and the ability to enjoy a fun activity get lost in a blind spot. If you’ve been on a few bad dates or missed out on past opportunities at work, your brain might let you believe there’s no point putting yourself out there rather than encouraging you to try again. These assumptions might leave you lonely or unfulfilled, but your brain will choose the lesser of two evils if the alternative is a rejection that you’re not set up to handle. Whatever frustration you feel as a result will be a feeling you’re at least accustomed to and, according to our nervous systems, when it comes to choosing between risks, it’s a case of better the devil we know.3 When we fail in ways that we’ve already anticipated, it can feel less confronting than failure that comes out of the blue.

We constantly make micro-predictions as a result of our blind spots, whether those are the well-documented associations between the colour red and danger4 or the way our startle reflex sees us flinching at a sudden loud noise before we even know what made it. It’s clear how these compressed thought processes are beneficial to our safety, and they can even help us in situations that are not life-and-death, such as avoiding putting a red sock into a white wash or making us pack an umbrella when there are grey clouds overhead. But they might be less helpful if they lead us to text our partner for reassurance when they’re out with friends and we’re feeling insecure. The more we understand about the way our brain is constantly acting like a concertina, and the more we can slow down the thought super-highways that take us straight from stimulus to response, the more able we are to see what else we might be missing and what other options we might have, so that the next time we’re feeling insecure we don’t

Blind Spot Therapy 19

What am I Missing?

outsource the responsibility to someone else and we feel empowered to help ourselves.

The predictions we make can form and re-form throughout our lives as experiences shape us, but the interactions we have in early life are crucial, as they will inform our primary expectations about ourselves, about others and about life in general. We will form a view of who we are from how others respond to us, and these snippets of early life experiences will calcify into our most rigid beliefs, reinforced by events that follow and preserved by blind spots that defocus alternative possibilities. This resulting shorthand for life is a phenomenon that the transactional analysis school of therapy would call our script.5 Transactional analysis, or TA, is my primary model of therapy, although having trained and worked with a number of approaches, I consider myself an integrative therapist today. TA will always have a special place in my heart, however, as it made sense to me in a way that nothing else had when I first discovered it in my mid-twenties, and for that I will always be grateful. Its simplicity, humanity and accessibility help me offer others the same experience today, guiding clients to understand how their scripts have informed their life choices, based on what they believe instead of how they feel.

‘ When we fail in ways that we’ve already anticipated, it can feel less confronting than failure that comes out of the blue. ’

What am I missing about my feelings and needs?

Feelings function as units of information that we can listen to, act upon and communicate to the outside world. A baby that feels hungry or cold will cry to communicate a need. At this stage in their life, it won’t be a need that they can understand. For that,

20

they are reliant on an adult who is willing and able to attune, to translate a cry into a request and, usually through trial and error, to meet the need and help the discomfort pass.

This process remains largely unchanged throughout life. Let’s say a child has a feeling of frustration because their younger sibling gets more attention. This feeling is a signal that communicates a need. Their frustration is a signal to the child that something is wrong and, hopefully, a signal to their adults that something is amiss. Easily remedied if the adult is willing and able to attune, to adjust the attention in the household or make space for the older child to express their grief as they come to terms with a new world where their parents are no longer entirely at their beck and call. In this way, they are helped to evolve their relationship into something healthy, sustainable and realistic, with an imperfect yet loving and available parent – coined the ‘good enough mother’ by psychoanalyst Donald Winnicott in his book

Playing and Reality 6

But this clean process of feeling, needing and resolving can be derailed if the adult in charge is preoccupied or lacks their own experience of positive parenting. If the child senses that their feelings and needs are unacceptable, unwelcome or cause their adults distress, they may learn to silence them. For others who don’t have an attentive caregiver, the reality may be that a remedy is not available, and the reality of their social or economic disadvantage will mean their needs go unmet.

If we don’t have experience of our needs being met by the people looking after us, or if our basic needs were met but our emotional needs were not, we might find a way to not need in order to protect ourselves from pain. (We will explore this more in the section on attachment theory on p. 164.) Or, if the family we were born into didn’t show vulnerability or needs themselves, we might deny our own in order to fit in. Perhaps we only got attention when we were ill or needed help, so we continue to depend on others as adults as a means to feel seen and maintain

Blind Spot Therapy 21

relationships. Or, as the old adage goes, if the one who asks gets last in your family, you might still be waiting to be offered to and accepting attention as it comes. If something impacted your early life, be it a family break-up, a bereavement or a crisis, your parents’ best-laid plans may have been flooded by trauma and your needs may have sunk to the bottom.

Here’s where our blind spots come in. When we’re faced with unmet needs and unresolved feelings, our brain subconsciously blurs our awareness to psychologically protect us. We form and fix perceptions of ourselves, others and the world that will help bring greater predictability and a sense of safety into our existence, in place of real security. An example of a blind spot I see in clients more than most is the one which preserves the ‘perfect parent’: even as adults, clients will resist a view that includes the limitations of their parents. As children, the only possibility worse than feeling your own flaws is feeling the flaws of the people taking care of you. Better to believe yourself as the creator of your chaos than believe there is no hope for order, and no one who knows better, as Gabor Maté describes in his brilliant book The Myth of Normal. 7

I remember the moment in a session when a client finally acknowledged that, all those times he had crossed the road holding tightly on to his mother’s hand, it had not been for his safety but for hers. She was an alcoholic and, by the end of the school day, she could pose a danger to herself. Still, he’d kept the image of his protective mother intact and persuaded himself that he’d been safe growing up and that she was taking care of him. He couldn’t reconcile the latent level of anxiety that he carried throughout his life until he acknowledged the reality of his mother’s unavailability and the impact of her risky and erratic behaviour. Accounting for the fear he’d dumped into a blind spot helped explain why he still sought safety in the most unsafe of places, burning out to get the next promotion at work

22

What am I Missing?

and maintaining friendships that led to nights of reckless selfendangerment.

Blind spots can be born of trauma, privilege, attachment style, conditioning or prejudice, and are reinforced by experience. Like a vacuum, assumptions and prejudgements pull in their surrounding material: like attracts like; and experiences that resemble the original belief blur into an ever-expanding blind spot, making any evidence to the contrary disappear. A fear of public speaking morphs into generalized anxiety, and a betrayal in one relationship casts a shadow of mistrust on all who follow. Agoraphobia8 grows not out of an all-encompassing fear-based blind spot of leaving the house, as is often depicted in fiction, but from a creeping fear of everything, until the only safe place that remains is behind your own locked door. Sunken into this vast blind spot are all the alternative realities and options for resolution and safety, and the longer a blind spot goes unchallenged, the bigger and more pervasive it gets, until it loses its very definition as an area of invisibility at all. It stops being seen in relief and becomes the lie of the land.

‘ Like a vacuum, assumptions and prejudgements pull in their surrounding material: like attracts like. ’

Shades of grey

To what extent these blind spots become ingrained will depend on the degree of distortion we make to preserve them. Transactional analysts Eric Schiff and Ken Mellor outline this idea in their work on ‘discounts’ – a term given to ‘an internal mechanism which involves people minimizing or ignoring some aspect of themselves, others, or the reality of a situation’.9

23

Blind Spot Therapy

What am I Missing?

Building on this work, information can be lost from view at three levels when a blind spot is formed:

1. Most severe would be our awareness of the situation’s very existence in the first place.

2. Next would be our acknowledgement that the problem is of significance.

3. And ultimately that we have options to change our circumstances.

In this way, blind spots can vary in depth and severity and some of the gaps they create in our awareness will look more like a patch of grey than an endless black hole. Blind spot therapy has become an area of specialism within my practice and, like many therapies, begins with information gathering and assessment. I work with my clients to build an overview of the blind spots that are getting in their way, to understand how deeply ingrained they are, and to develop a treatment plan that will be most effective.

Let’s consider how the different degrees of blind spot might look if we were dealing with a physical symptom. For example, if someone knows they have an unusual lump under their skin, they know this warrants their attention and they understand that they can make an appointment with a doctor. You could describe this as someone seeing the problem with 20/20 vision without any blind spots clouding their judgement. However, the situation will look different at each of the three levels of their discounts:

1. Most concerning would be the blind spot that means they don’t see a lump in the first place and they deny it exists at all. They have a blind spot around the existence of this fact, and we’ll have much more work to do to help them uncover the reality of their situation, the significance of it and the options available to them.

2. With a less deeply ingrained blind spot, they might know they have a lump but not acknowledge the importance of

24

that fact, let alone seek medical attention. This would tell me that they have a blind spot around significance, that they disregard its relevance to their wellbeing or that they disregard their wellbeing altogether. We’ll have to address this before we can get them to consider their options for help.

3. If they know they have an unusual lump and they recognize this should be looked at but they don’t believe this option is available to them, or they believe that there’s nothing that can be done, there may be a blind spot here around their right to treatment or their value as an individual.

Part of my job is to look for the origins of a client’s blind spots, to help them see the good reasons why they shield themselves from a situation and to plot a course out of the darkness and the difficulties they encountered there. To uncover the depth of their blind spot, I’ll often illustrate our assessment process as a trip to their ‘psychological optician’ to help them improve their sight, no matter how good or bad it is to begin with. You too can begin your journey towards greater authenticity and happier relationships with a check-up at the psychological optician, using my Psychological Sight Test to assess your level of awareness (adapted from Schiff’s ‘discount matrix’).10

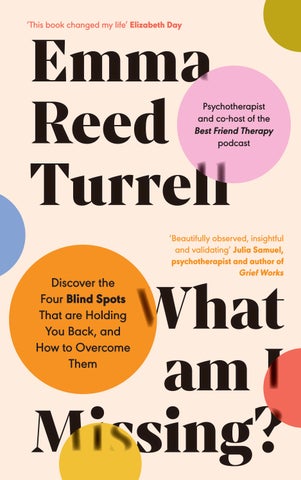

The Psychological Sight Test

Imagine you had a problem with your eyes – maybe you’ve been struggling to read road signs or you’re experiencing headaches. You book a sight test with an optician who asks you to look at the wall opposite you and read out the letters on the chart. Normally the first row is big and easy to see, but as you scan down the rows the letters become smaller and blurrier and you start to stumble and make mistakes.

The same applies for blind spots in our psychological sight. The top row is relatively easy to read, so most (although not all)

Blind Spot Therapy 25

What am I Missing?

people can see this information – it relates to the existence of a problem. It goes without saying that 99 per cent of the clients I see can read this row, as they have felt the need to come and speak to me. But the threefold nature of blind spots means that our work together usually focuses on helping them to see the significance of their issue and their options for change. existence significance options

Problem?

What problem?

It can’t be helped . . .

It’s no big deal . . .

26

fig. 1. psychological sight test