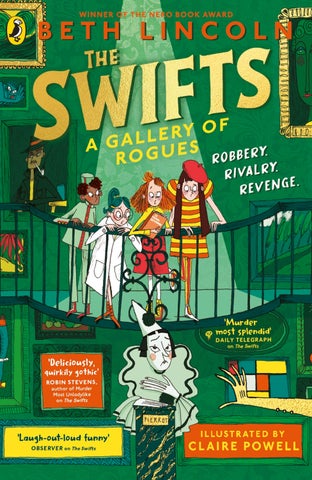

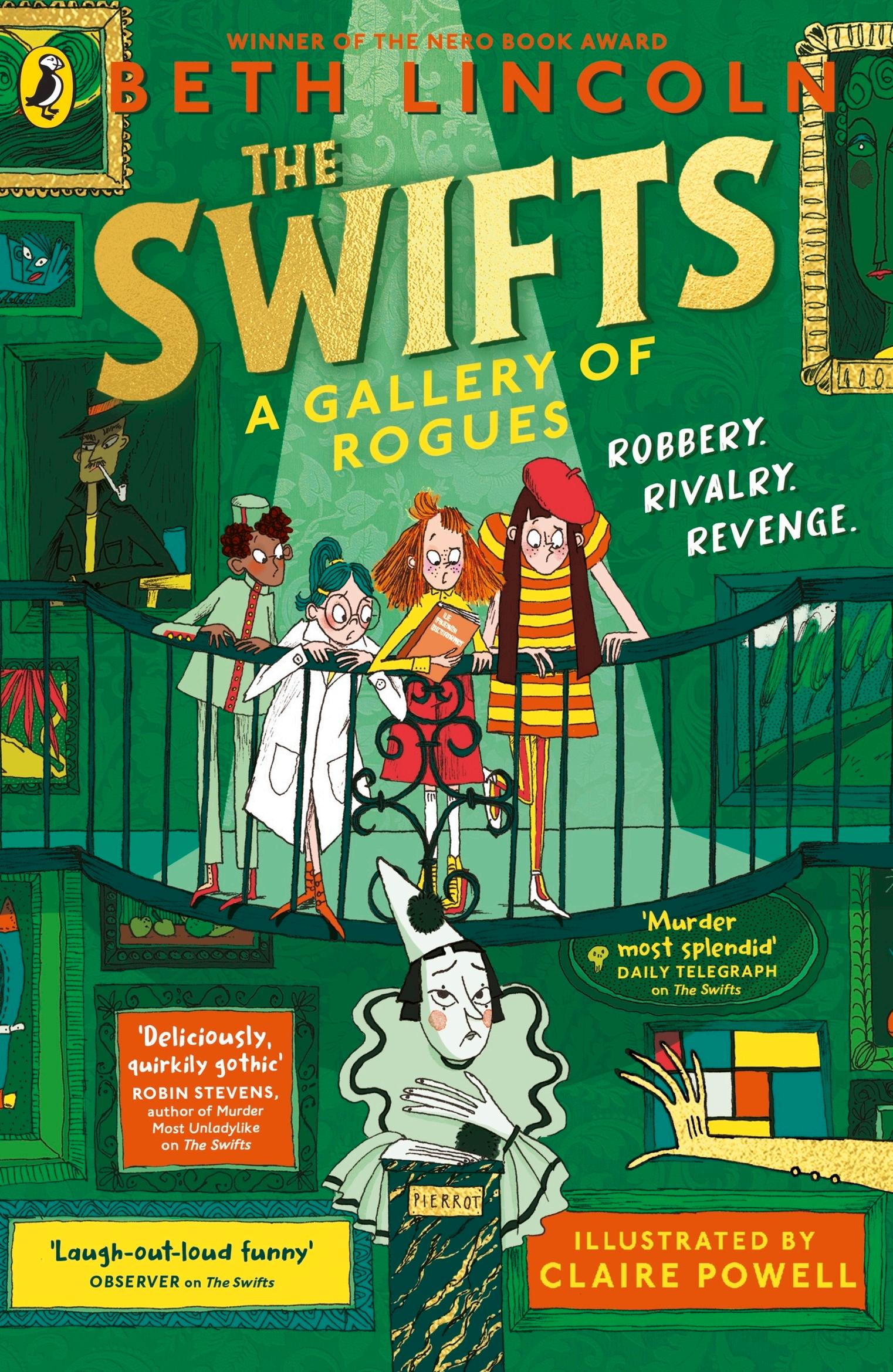

PRAISE FOR THE SWIFTS WINNER OF THE NERO BOOK AWARD FOR CHILDREN’S FICTION

‘A stunning debut . . . This is an exquisitelywritten book about identity and wordplay that’s as warm, masterful, and up-to-date as it is laugh-out-loud funny’

Kitty Empire, Observer

‘Deliciously, quirkily Gothic’

Robin Stevens, New York Times book review ‘Murder most splendid in this ghoulish debut’

Emily Bearn, Telegraph

‘Gothic mystery brimming with bonkers characters and boundless energy’ Daily Mail

‘A fun read with diverse characters and an enticing setting’

Alice Clifford, The Sun

‘A mystery that is as clever and impish as its heroine’ Publisher’s Weekly starred review

‘An absolutely delightful debut’ Kirkus Reviews starred review

‘A witty confection of highly colourful characters’ The Horn Book

Also by Beth Lincoln The Swifts

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia India | New Zealand | South Africa

Pu n Books is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com.

www.penguin.co.uk

www.pu n.co.uk www.ladybird.co.uk

First published 2024 This edition published 2025

Text copyright © Beth Lincoln, 2024

Illustrations copyright © Claire Powell, 2024

The moral right of the author and illustrator has been asserted

Penguin Random House values and supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes freedom of expression and supports a vibrant culture. Thank you for purchasing an authorized edition of this book and for respecting intellectual property laws by not reproducing, scanning or distributing any part of it by any means without permission. You are supporting authors and enabling Penguin Random House to continue to publish books for everyone. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner for the purpose of training arti cial intelligence technologies or systems. In accordance with Article 4(3) of the DSM Directive 2019/790, Penguin Random House expressly reserves this work from the text and data mining exception.

Typeset by Jouve (UK ), Milton Keynes

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The authorized representative in the EEA is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin d 02 yh 68

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

isbn : 978–0–241–53647–6

All correspondence to: Pu n Books

Penguin Random House Children’s One Embassy Gardens, 8 Viaduct Gardens, London sw 11 7bw

Penguin Random Hous e is committed to a sustainable future for our business, our readers and our planet. is book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper.

For Stuart, my favourite.

In Morbidity Swift’s De nitive Ranking of Painful Deaths, Drowning is quite far down the list, sitting squarely in the Merely Unpleasant tier. It is well below Starvation, Bear Attack, and Acid Vat, and well above Having a Piano Dropped on One’s Head, or Dying Peacefully in One’s Sleep Whilst Having a Lovely Dream About Butter ies.

This thought was a comfort to Shenanigan Swift as she struggled for air. Things could always be worse. She squinted through the murky water at the rope round her ankle. It was tied securely in a bowline knot. Shenanigan was good at knots, and she had tied and untied a bowline a hundred times before. But this one stubbornly refused to loosen – as did its twin, which she had looped round the heavy brass microscope now

half-buried in the soft mud of the lake bed, as snug as a tooth in a gum.

A rebellious bubble snuck out of Shenanigan’s left nostril and made a break for the surface. Her lungs burned, and her throat contracted desperately. Her body was telling her rmly that she needed to take a deep breath right now, and wasn’t listening to any of Shenanigan’s reasons why that was a bad idea. With a gurgle of e ort, she pulled the bread knife from her belt and began to saw desperately at the rope. Something interesting was happening to her vision. It was going dark at the edges, as if she was squinting through dense cloud.

The rope snapped. Shenanigan rocketed upwards, expelling air as she went. Above her, light danced in broken beams on the water’s surface, a rippling glass roof that she shattered with the force of a hurled stone.

Shenanigan burst into the hot sun of mid-morning, coughing and gasping as she hauled oxygen into her lungs. She scooped water in her now-empty hands, and looked down to see the bread knife winking merrily away into the depths of the lake. Cook would not be pleased.

‘Oh, there you are. I don’t suppose you’ve seen my microscope, have you?’

Shenanigan jerked in surprise. Phenomena had got quite stealthy lately. She stood at the end of the jetty, her lab coat glowing in the sun, aiming a raised eyebrow at her half-drowned sister.

Shenanigan thought fast. ‘Well, yes,’ she replied. ‘I have seen your microscope. Many times.’

‘But recently. In, say, the last hour or so?’

Shenanigan never lied. She merely told a version of the truth. This was infuriating to everyone, including Shenanigan, who constantly had to come up with creative ways of telling the truth that wouldn’t get her into trouble. She often considered writing a guide.

‘It has been . . . some time since I last saw it,’ she hedged. Technically, a minute counted as ‘some time’. But Phenomena had grown up with Shenanigan, and had come into the conversation with the unfair advantage of knowing most of her tricks.

‘It’s just that when I asked Cook,’ Phenomena went on, ‘she said she hadn’t seen it either, but had seen you heading into the garden with a covered object she described as “microscope size”.’

Shenanigan resolutely did not look below her kicking feet, where the microscope snuggled ever further into the mud. ‘Are you sure she didn’t say “microscopic”?’

‘I’m sure,’ said Phenomena. She squinted through her glasses. ‘It doesn’t take a scientist to collect the data and draw a conclusion.’

‘Didn’t you once tell me,’ tried Shenanigan, ‘that correlation does not equal—’

‘My microscope is in the lake, isn’t it?’

‘It is in the lake, yes.’

Phenomena sighed, and held out a hand to help Shenanigan op on to the jetty.

‘I didn’t expect it to get stuck,’ Shenanigan muttered apologetically. ‘I was going to pull it back out again.’

‘Like the statue, the candelabra, and the ornamental doorstop?’

Shenanigan winced. The bottom of the lake was now a backyard Atlantis, in which strange objects loomed out of the silt like relics from a long-lost civilization. Shenanigan would never have taken Phenomena’s microscope if she hadn’t run out of other heavy, less important things.

‘And I don’t suppose you’ll tell me what you’re up to?’ Phenomena asked.

‘Will you tell me what you’re up to in the hidden room, with the EEK ?’

‘Oh, of course not.’

The sisters grinned at one another, each delighted in their own secrets, and headed back to the House.

For weeks, Shenanigan had been dodging her Family’s questions about what she was doing in the lake. She’d told them that she was training to be an escapologist, which was half-true. Escapology was a very useful skill to have, like juggling, and could be helpful in all sorts of situations. But the truth was that she needed the weights to pull her to the lake bed as quickly as possible, so she’d have more time to ri e through the sludge for Grand-Uncle Vile’s long-lost treasure.

Shenanigan had once read that Harry Houdini could hold his breath for over three minutes. So far, she was up to two minutes and two seconds. She had been disappointed in her progress, until she remembered that his lungs had been much bigger than hers; but then, since his body was also much bigger, perhaps he needed more oxygen than she did? The question of who had the better lung capacity would have been an excellent one to ask Phenomena, but Shenanigan couldn’t, because she had promised herself that she

wouldn’t tell her relatives about the treasure until she’d gured out what to do with it.

It wasn’t that she couldn’t decide. She decided at least three times a week. Lying in bed, staring at the rain drumming on her skylight, she’d think, I’ll use it to take Arch-Aunt Schadenfreude on holiday. She won’t want to go, but I’m sure if we put blinkers on her, like on a horse, we could get to a train station without her bolting. Listening to Cook tell her how to make an omelette, she’d think, Maybe I could buy up all the green bell peppers in the world and sink them to the bottom of the ocean, and then no one would ever have to eat them again. While reading in an out-of-the-way pocket of the House, she’d think, Maybe I’ll give the money to an orphanage, like some old woman with no heir and a terrible secret. I’m sure I’ll have a terrible secret one of these days. And round and round the ideas went, until her dreams were a whirl of gold and silver and cheering children, who all had lisps.

As Shenanigan picked pondweed out of her hair, Phenomena passed her a slip of paper. ‘I found this in my sandwich,’ she said. ‘We’ve got another Family meeting.’

Shenanigan squinted at the writing, barely legible beneath the peanut butter. It said:

I welcome you with arms wide to the place where the sun is saved.

When Arch-Aunt Schadenfreude had retired several months ago, she had named their second cousin Fauna as the new Matriarch of the Swift Family. Fauna was the ideal choice. She was compassionate, forwardthinking, and optimistic, the opposite, in many ways, to Aunt Schadenfreude. As part of her new role, Fauna had moved into Swift House, separating for the rst time from her twin, Flora.

It had been an adjustment for everyone. Fauna travelled into town on sunny days, squashing rumours that Swift House was a den of vampires. She invited Suleiman, their intrepid postman, to come for tea. She had taken an active role in Aunt Schadenfreude’s funeral rehearsals, and impressed her deeply by crying every single time.

But the hardest thing to get used to was her insistence on Family Meetings. Aunt Schadenfreude considered it coddling to speak to the children more than once a day, and the idea of sitting around discussing their feelings, plans, and accomplishments had not gone down well with the inhabitants of Swift House. In an attempt to win them over, Fauna had taken to holding

each meeting in a di erent room, with the time and location hidden in a riddle, cleverly deducing that their competitive spirit would ensure they turned up.

‘ The place where the sun is saved could be the conservatory,’ suggested Shenanigan.

‘A room where the sun is “conserved”, or saved, yes,’ said Phenomena.

‘And arms wide ?’

Phenomena held out her arms as if wanting an embrace. ‘Imagine I’m a clock.’

‘Oh! Your hands would be at nine and three. So, quarter to three?’

‘Or a quarter past nine, but that seems a little late.’

Shenanigan picked up Phenomena’s wrist and checked her watch. It was twenty to three.

‘I thought I’d better come fetch you,’ Phenomena explained. ‘There will have been a note in your sandwich as well, but no doubt you ate it.’

It was hot in the conservatory, the plants drinking in the sun and exhaling a green smell Shenanigan found a little sti ing. Fauna was sitting in a rattan chair, answering a few of the extended Family’s messages. Several lengths of washing line criss-crossed the room,

with envelopes xed to it by brightly coloured pegs. Now and then, Fauna would pull on one of the lines, and with the rattle of a pulley another set of letters would rotate towards her. With her loose, wavy red hair and new taste for owing dresses, she looked like an elf tucked among the giant leaves of the monstera and potted palms.

Shenanigan wrung her hair out into the nearest plant pot, and sprawled on the oor by Uncle Maelstrom’s chair. He raised his considerable brows at the rope still knotted round her foot.

‘That looks familiar,’ he said.

‘Does it?’

‘Mmm. It looks like Manila rope. I remember leaving a length of it on my desk the other day after rehanging my hammock.’ He took a penknife from his pocket, selected a blade from between the ballpoint and fountain pens, and carefully sawed through the knot at Shenanigan’s ankle. This was greatly appreciated, as her foot was turning purple.

‘It might interest you to know that this sort of rope swells when wet,’ he added, ‘which means any knot you tie in it would lock tight underwater.’

‘Oh,’ said Shenanigan.

‘In damp environments, it’s better to use synthetic rope, and tie it loosely. The stu I have looped round my umbrella stand is waterproof, for example.’ He winked.

This was why Shenanigan loved Uncle Maelstrom. If she’d announced she was going to leap out of a plane, he wouldn’t try to stop her. He’d teach her how to make a parachute.

‘Thank you all for coming,’ said Fauna, pouring tea with one hand and replacing a peg with the other. She had a faint frown on her face; it made her look like her sister. ‘How are we today?’

She surveyed the circle of relatives. There was Aunt Schadenfreude, lounging comfortably with a battered paperback and something green smeared all over her face; Cook, sleeves rolled to the elbows and her cropped hair streaked with motor oil; Phenomena, making notes in her journal; Maelstrom, squashed into his too-small chair with one of Fauna’s tiny Japanese teacups cradled in his hand; and nally Shenanigan, coaxing some feeling back into her toes. The eldest of the Swift children was not present. Felicity was abroad, staying in Paris for a few weeks with Flora and Daisy. She phoned, when she remembered, and peppered her conversation with little French phrases to show she was sophisticated now.

The only other resident of Swift House was John the Cat, and he was not present either, as he wasn’t very good at riddles.

‘This had better be quick,’ snapped Aunt Schadenfreude. ‘I was just getting to a good part of this very silly book.’

The book in question had an image of a woman on the cover, swooning in the arms of a muscular werewolf. Schadenfreude had really dedicated herself to retirement. Cook had even bought her a pair of u y slippers, which Aunt Schadenfreude had insulted viciously and worn every day since.

‘Noted,’ said Fauna. ‘Cook? Maelstrom? You’re well? Good. Girls?’

‘We’re ne,’ Phenomena and Shenanigan chorused.

‘Not missing Felicity?’

‘Nah,’ said Shenanigan.

‘I forgot she was even gone,’ said Phenomena. ‘Who’s Felicity?’ added Shenanigan.

‘It’s alright to miss her, you know,’ said Fauna. ‘You’ve been together your whole lives. It’s a big change.’

‘I know it’s alright.’ Shenanigan sighed. ‘But I really don’t.’

‘She’s probably having the time of her life,’ added

Phenomena. ‘Conjugating verbs at people, and buying silk scarves.’

Fauna’s smile was sad. ‘You can be glad she’s living her life without you, and happy you’re living yours, and still miss her,’ she insisted. She blinked hard. ‘Since she’s in Paris, and very far away, and your best friend.’

‘She’s not my best friend,’ Shenanigan muttered as Cook handed Fauna a handkerchief. ‘She’s not even my best sister.’

This made Cook tut, but Shenanigan and Felicity had ended their long grudge a few months ago. They still insulted each other, but now Felicity smiled when she called Shenanigan a pest, and Shenanigan removed spiders from Felicity’s room rather than putting them there.

‘Anyway –’ Fauna blew her nose – ‘Felicity is actually the reason I called you all here.’ She plucked a letter from the line above her head and smoothed it over her knee. ‘Your sister has sent us a letter, and – well, before I read it, let me just say that I don’t think we need to be concerned.’

‘Always so reassuring to hear,’ muttered Aunt Schadenfreude.

‘It’s just that I know you’re going to react badly,’ said

Fauna, ‘and I really think there’s no need. Um. I’ll just read it.’

Felicity had learned to write from romance novels set in the 1800s, the kind where people fall into near-fatal fevers at any minor inconvenience. To Shenanigan, her letters all sounded as if they were about to announce either her imminent marriage or imminent death. This one read:

To my beloved family, from whom I am separated so cruelly (and also Shenanigan),

I write to you from a café on the Champs-Élysées, with a pot of co ee to my left and an Opéra cake to my right, and a perfect view of Paris’s most fashionable citizens between them. Daisy was kind enough to purchase this petite gâterie (that’s ‘little treat’) for me, and I think it cost as much as my last pair of shoes. She and Flora are currently in a parfumerie (that’s ‘perfume shop’) across the street, and if I squint I can see them in the window, spritzing.

An event occurred yesterday that will be of great interest to you. Whilst I was visiting La Garde- robe (a fashion museum), I was approached by one of our

cousins! Her name is Pomme, and I found her charming and most agreeable, and she has invited me to stay with our French relations, the Martinets, at their hotel. I was quite surprised, as I didn’t even know we had French relations, let alone ones with a special surname and a hotel of their very own!

I have decided to take Pomme up on her o er, and shall be parting company with Flora and Daisy forthwith. Of course, I know it is common for young women of my age to Go Into Town with their aunts, but I do believe my chaperones could do with some unchaperoned time themselves (please imagine I am giving you a meaningful look, Fauna). I will be heading to the Hôtel Martinet tonight, and have enclosed the new return address for your letters.

À bientôt (that’s ‘see you soon’, basically),

Felicity

It seemed like a perfectly normal letter to Shenanigan, but Aunt Schadenfreude nodded grimly. ‘Well, that’s it, then,’ she said in a brisk tone. ‘Felicity’s as good as dead.’

Shenanigan could feel her hair beginning to dry, sticky and uncomfortable and smelling vaguely of lake water. Felicity, dead?

Fauna sighed. ‘This is what I was worried about. You’re being dramatic , Aunt Schadenfreude. Our relationship with the Martinets might be . . . strained, but it’s hardly murderous.’

‘Not for years,’ put in Maelstrom.

Shenanigan blinked. She had definitely missed something important somewhere. She had never heard of the Martinets before, and felt certain that if there was a vendetta going around she should have been the rst to know about it.

‘Besides, Auntie, they’re Family,’ added Fauna.

‘Exactly,’ sni ed Schadenfreude. ‘Untrustworthy creatures, the lot of us.’

‘’Scuse me,’ said Shenanigan, ‘are you saying we’re at war with our cousins?’

‘No! It’s just a silly feud,’ insisted Fauna, rubbing her temples. ‘We haven’t been at war in a long, long time.’

‘But we were ?’

Schadenfreude wiped the last of the green goo from her face with a napkin. ‘Not exactly. As a rule, Swifts try to stay out of the military. There are far too many parades, for one thing. But England and France have been at war so often throughout history that it was inevitable that the Swifts and the Martinets would sometimes nd ourselves on opposite sides.’

‘And that’s why we hate each other?’ asked Shenanigan.

‘Oh no,’ said Schadenfreude dismissively. ‘That’s just politics. We all understand that one cousin might occasionally bayonet another. No, we hate each other because we can’t agree who came rst.’

Imagine two unpleasant children who live on opposite sides of a long stretch of water, and throw stones at

each other every chance they get. That’s England and France.

In 1066, after the English King Edward the Confessor died, William I, the French Duke of Normandy – thereafter known in England as ‘William the Conqueror’, for reasons that will become obvious – packed up a bevy of archers and sailed across this stretch of water to claim the throne. Unfortunately, Harold Godwinson, Edward’s successor, was already sitting on it. After a brief scu e that bathed the elds of Hastings in blood, William got the throne, and the Normans moved in.

The Normans stayed for a very long time. Long enough, in fact, to become English themselves. But meanwhile, across that stretch of water, France was still there. The Norman Conquest had only been the start of a con ict that would rage for centuries. For the next six hundred years, England and France went through revolts, squabbles, political marriages, genuine attempts at peace, false attempts at peace, assassinations, occupations, and violent disagreements over who could colonize which parts of the world – disagreements in which, it should be noted, the people already living in those parts were not consulted. Until about 1900, wars

between England and France were as reliable as buses – you could always count on one coming along in the next decade or so.

What does this have to do with the Swifts and Martinets? Well, with England and France tossing people and languages back and forth for so long, no one in the Family could agree if someone with the last name Martinet came over to England and changed their name to Swift, or if a Swift went over to France and changed their name to Martinet. They are undoubtedly the same Family – a martinet and a swift are the same bird, whether in French or English – but who was rst? Archivists have pondered this for generations, but there is simply no way to know for sure. In the meantime, Martinets generally don’t come to Swift Family Reunions. And when two cousins do meet at a party, it soon stops being a party and instead becomes an axe-throwing contest, a drag race, or a good old-fashioned st ght.

‘Cousin Fletching lost an eye playing darts with Chouette Martinet,’ said Aunt Schadenfreude, ticking people o on her ngers. ‘Trefoil Martinet broke a leg skiing with my grandmother Dauntless, and never forgave her. Luxe and Yonder both perished on the Titanic, which was hardly our fault—’

‘That’s all history, Schadenfreude,’ said Fauna. ‘There hasn’t been a Swift–Martinet death in over a hundred years.’

‘Oh really?’ said Schadenfreude archly. ‘I thought a Martinet just died in this very House. Pomme’s brother, in fact. How glad I am to learn I imagined it.’

That brought Fauna up short. Pamplemousse de Pastiche Martinet – raconteur, émigré, and noted duellist – was the newest resident of the cemetery behind Swift House. An excitable man, fond of antique weaponry, creative insults, and board games, he had met his end in a Scrabble match during the recent Swift Family Reunion, at the hands of a rogue relation intent on seizing Grand-Uncle Vile’s lost treasure. Shenanigan had been forced to abandon her own hunt for the Hoard in order to catch them.

‘That was di erent,’ argued Fauna.

‘And you think they will care? It’s entirely possible the Martinets want to even the score, and Felicity is conveniently in reach.’

‘So Felicity is staying in the Family murder hotel?’ demanded Shenanigan, who felt that an important injustice was being overlooked. ‘How come I don’t get to stay in the Family murder hotel?’

‘Please don’t call it a murder hotel,’ said Cook, growing pale. ‘Your sister is not staying in a murder hotel.’

‘Not yet,’ muttered Aunt Schadenfreude.

‘Felicity is ne,’ said Fauna, raising her voice ever so slightly. ‘And, actually, I think we should view this as a positive step towards Family unity. Felicity was invited there – how long has it been since that happened? Maybe we can build on this. I think we should join her.’

Maelstrom leaned forward. His eyes were sparkling.

‘I think that’s an excellent idea.’

‘You know, I went to culinary school with a Martinet,’ said Cook. ‘Perhaps we should reach out.’

‘Ha!’ sco ed Aunt Schadenfreude.

‘Auntie, please. This is a real opportunity to heal the rift between us!’

‘Well, I don’t know why you’re trying so hard to convince me,’ hu ed Schadenfreude. ‘This is a decision for the Matriarch. That’s you, my girl.’

Fauna blinked. She looked round at the washing lines criss-crossed with letters, as if remembering that, yes, there was a reason she was sitting at the centre of them. Schadenfreude regarded her with smug satisfaction.

‘Then . . . then that’s what we’re going to do,’ Fauna said. ‘We’ll visit the Martinets, and talk things out. No matter how we say our last name, we’re Family.’

Maelstrom stood abruptly, disturbing the cloud of steam rising from Shenanigan.

‘Well said, Matriarch!’ he boomed. ‘We should set sail tomorrow, at rst light.’

‘Hold on,’ said Fauna. ‘That was a general “we”. I can’t go. As Matriarch, my place is at Swift House. As you can see –’ she gestured to her washing line – ‘I’ve a laundry list of tasks. I thought perhaps you and Cook—’

‘I can’t,’ said Cook, looking wretched. ‘Travel is . . . complicated for me. I don’t have a passport.’

‘I haven’t left this House in decades, and I’m not about to leave now,’ added Schadenfreude.

Maelstrom shrugged. ‘Then it will just be me and the girls— Why those faces? Obviously Shenanigan and Phenomena are going.’

‘Obviously.’ Shenanigan shivered. It felt as if every organ in her body was switching places, but in a good way. Unfortunately, her excitement was short- lived. The bigger her smile grew, the more concerned the other adults started to look.

‘I’m not sure that’s a good idea, Maelstrom,’ said Cook.

‘Why? If the Martinets try anything, I’ll be glad of their protection.’ Maelstrom winked at Shenanigan, who brandished her sts.

‘It’s more – well, this would be a diplomatic visit,’ said Fauna.

‘You don’t think we can be diplomatic,’ challenged Phenomena, folding her arms.

‘It’s not that ,’ said Fauna, and Shenanigan could see the trace of a lie by her ear. ‘I just think we need someone who knows the history between the Swifts and Martinets. Who has authority within our Family, if I can’t be there. As our Archivist, I think Aunt Inheritance is our best chance.’

It was quite possible that no one in the history of the world had ever said those words in that order before. Shenanigan gaped.

‘What?’ she and Maelstrom cried in unison. To be kept from a potential adventure was bad enough, but to have Aunt Inheritance – a cup of lukewarm milk in human form – chosen over her ? Unthinkable.

‘By all means, send Inheritance as well,’ said Maelstrom – ‘she is the expert in Family a airs – but when it comes to charm—’

Fauna held up a hand. ‘I hear you. Girls,’ she said

evenly, ‘I think we adults need to have a terribly boring chat. Why don’t you go and, ah, write a letter to Felicity? I have the address here . . .’

Shenanigan didn’t take her eyes o Uncle Maelstrom. If there was ever a time to manifest psychic powers, it was now.

Convince them to let us go, she thought at him. Don’t betray our sacred bond.

Maelstrom didn’t look her way, but he did scratch his ear as she was walking out, so maybe something had got through.

Shenanigan’s boots were already half o before the conservatory door closed behind her. She wasn’t taking any chances. Phenomena rolled her eyes.

‘Really?’

‘Shh! D’you know, you look so much like Fliss when you do that.’

Shenanigan shoved the boots into her sister’s arms. They waited; ten seconds . . . fteen . . . then:

‘We know you’re listening at the door, girls!’ called Cook.

Shenanigan groaned theatrically. ‘IT ’S NOT FAIR !’ she wailed, throwing in a few extra decibels for good measure. ‘COME ON , PHENOMENA ! LET ’S GO !’

She gestured hastily. With the ease of experience, Phenomena dangled Shenanigan’s boots by the laces, one in each hand, and walked them alongside her down the corridor. It was an old trick of Shenanigan’s. As long as you weren’t listening too closely, it sounded like two sets of footsteps walking away. The hardest part was trying not to laugh at the hunched-over walk Phenomena had to adopt to make sure the boots hit the oor.

As the sound of one person and four shoes faded, Shenanigan heard Cook’s voice.

‘Maelstrom, have you been drinking seawater?’ she hissed. ‘Now you’ve introduced the kids to the idea, they’ll be begging to go. If we don’t say yes, Shenanigan will be hitch-hiking to Dover come morning!’

‘Oh, I don’t think so,’ protested Maelstrom. ‘She’s perfectly capable of stealing a car.’

Shenanigan had to bite her knuckles to keep from giggling, even though she could hear Cook grinding her teeth through the door.

‘I think what Cook is trying to say,’ said Fauna soothingly, ‘is that when making decisions regarding the children, we should discuss our options together rst, and present a united front—’

‘What? No,’ snorted Cook. ‘I’m saying that Maelstrom’s jumping at the chance for a trip without thinking about the girls’ safety!’

‘They did well sorting out that business at the Reunion,’ noted Aunt Schadenfreude. Her tone indicated that she was barely paying attention to the conversation. This, Shenanigan knew, was a ruse.

‘But they shouldn’t have had to,’ said Cook. ‘That was a lot to go through, and it was only a few months ago! Now you want to send them abroad for the rst time in their lives? Alone?’

‘Alone?’ retorted Maelstrom. ‘What am I, a feather duster?’

‘No, but I think it’s sel sh of you to drag the girls across the Channel just because you’re bored !’

Suddenly, Shenanigan wished she wasn’t listening. Cook and Maelstrom argued occasionally, but always about silly things, like the correct way to x the plumbing or who the best blues singer was. This was a real ght, the kind she used to have with Felicity before they called a truce. And they were ghting about her.

She heard Cook sigh. Then, her voice softer now, she said, ‘I’m sorry, Maelstrom. That was unfair. But

you’ve been restless lately – we’ve all seen it. How much of this is actually about you wanting another adventure?’

Maelstrom’s chair creaked. His voice was low and embarrassed as he said, ‘I won’t deny it. My feet itch.’

‘Of course they do. When was the last time you got out of the House?’

‘Several grey hairs ago, I’ll warrant,’ said Schadenfreude, and Maelstrom chuckled ruefully.

‘Maelstrom, you don’t have to tether yourself so tightly to the House,’ put in Fauna. ‘If you want to travel, then, by all means, go. Take a holiday! Or, if you truly want to go to Paris, go to Paris. Someone would need to go with Inheritance, anyway, to compensate for her . . . personality.’

‘Just go? Without the children?’

‘ Without the children ,’ said Cook. She was quiet but rm.

Say no, thought Shenanigan furiously. You are my ally. Say you won’t go without me.

‘I’ll . . . think about it,’ said Maelstrom.

Shenanigan sulked for the rest of the day. She had half a mind to challenge Fauna to a duel, but she’d gone o

them a bit since Pamplemousse had been killed on their front lawn. She wasn’t even sure if it was Fauna she should be ghting, as she was angry at all the adults in the House. Maelstrom had already had his adventures, so many he was writing a book about them. That he would consider going o to have even more without her – and without Phenomena too, she supposed – was a betrayal of the highest order. Maelstrom only got a pass for leaving Shenanigan out of his previous exploits because she hadn’t been born yet.

The thing that irked Shenanigan most was that Cook had been right: Uncle Maelstrom had been a little restless recently, as if he had an itch that wouldn’t go away. She understood, because she often had that same feeling. It had worsened over the months and had become unbearable once Felicity left for France. Shenanigan wanted out.

Since it lacked a jungle, a mountain, or dangerous local wildlife, Paris had never been high on Shenanigan’s list of places to visit. But now that it was within touching distance Paris became the most interesting destination in the world. Every building in the city would have corridors she’d never run down, corners she’d never turned. She would even get to experience

streets. Plural! The local village only had the one. Paris must have at least ten.

Shenanigan considered what she actually knew about Paris, and found that most of it was at and cartoonish – oppy hats, striped shirts, and long bread – so she spent the rest of the day reading every book she could nd about the city, carefully avoiding losing a hand to one of the library’s traps.

By the time she headed to bed, it was dark and near-silent but for the rumbling of her stomach (she had skipped dinner out of protest) and a low hum emanating from the once- secret room that held the Ecto Electric Kin- communicator. Phenomena had been spending more and more time with the EEK recently, trying to gure out how it worked. She was probably quite happy to stay home with her research, Shenangian thought glumly.

Felicity was in Paris. Uncle Maelstrom was headed there too. Even Aunt Inheritance was going, and would probably take her grandchild, Erf, Shenanigan’s cousin and best friend. She ung herself down on her bed, startling John the Cat, who was snoozing on her pillow. On her wall was a collage of postcards sent by her parents over the years, from the many corners of the

world they had visited. Greetings From Reykjavik! G’day from Down Under! With Love from Lagos!

She fell asleep reading Wish You Were Here over and over again.

Shen anigan woke at four in the morning, when sleep grips the tightest and you have to really wriggle to get out of its grasp. She might have decided to go on a hunger strike, but her stomach had not agreed. She lay in the dark for several minutes, arguing with it, but a stomach is incapable of listening to reason. She got up, intending to head to the kitchen for an early breakfast.

It was still dark, but Shenanigan didn’t turn on any lights. When you have lived in a building for long enough, it becomes an extension of your own body. You can sense movement within its boundaries the same way you might feel an insect crawling over a tiny patch of skin, or a breath ru ing a stray hair. Which meant that by the time Shenanigan reached the third- oor

corridor she knew something was wrong by the way the back of her neck had started prickling.

She stopped next to the charred door of the EEK ’s room, listening. She could hear the machine humming – Phenomena must have left it on – and at rst she thought that was what had unsettled her. But her neck prickled all the way along the corridor and down the stairs until she looked out over the hall and saw the intruders.

There were ve of them, clad in mismatched black and masked by balaclavas. One was bent over a small object on the oor. Another was shaking out an immense length of fabric, and one was holding a at, square object under one arm. They worked quickly and silently by the light of camping lanterns.

They saw her the same moment she saw them, and paused in the middle of their tasks.

People respond in odd ways when they are surprised. They don’t always scream, or run. Often the brain takes a holiday, and the body does something embarrassing, like ail wildly and drop things. The sight of ve uninvited people in her home was so unexpected that Shenanigan didn’t bother to panic, and her stomach,

which was still upset about the hunger strike, reached up to take control of the situation.

‘Good morning,’ Shenanigan found herself saying. ‘D’you want some breakfast? I was thinking of making eggs.’

The intruders sprang into action. One of them, a whip-thin person with spiked hair sticking out of their mask, dropped the fabric they were holding. Another darted to the side, glasses ashing, and icked a switch. There was the whine of a motor starting up, and the intruders sprinted away through the open front door.

‘OI !’ Shenanigan shouted, snatching a helmet o a nearby suit of armour and throwing it down the stairs with a crash loud enough to wake the whole House. She leapt on to the banister. Someone was running, and that meant she had to chase them. Her stomach was still in control of her mouth, and she bellowed, ‘ DO YOU PREFER YOUR EGGS FRIED OR SCRAMBLED ?’ as she slid downstairs. At least this sounded like a threat.

She hit the ground, and almost tripped over something, shining dimly in the light of an abandoned lantern. Liquid sloshed over her shoe. Behind her, she heard the

door down to the kitchen slam open as Cook burst in, wearing fuzzy socks and brandishing a barbell.

‘JUST YOU TRY IT, YOU LICKSPITTLE — My word, what is that ?’

The whine of the motor rose in pitch, and Shenanigan turned to see something moving on the oor between herself and Cook. It was a huge dark shape, misshapen and monstrous, heaving itself upright like a giant struggling to rise.

Light blazed. Cook had hit the switch, and Shenanigan winced in the sudden glare. In the centre of the hall was a vast puddle of fabric, twitching and jerking as it lled with air. A withered limb, brown and curved backwards, shot out and knocked a painting o one wall. A second later, its pair emerged with a faint thwump , knocking over something metallic and full of water.

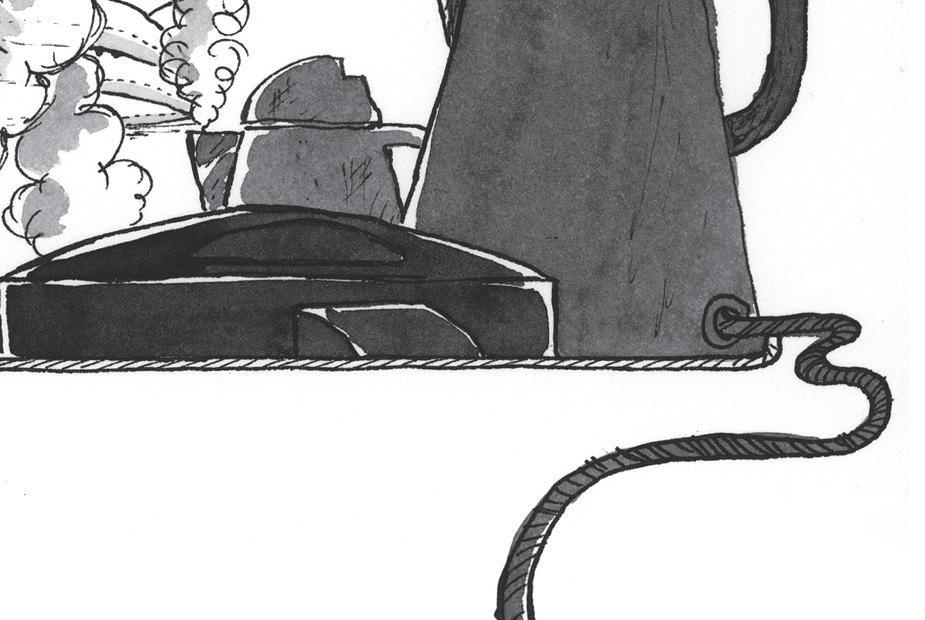

‘Some kind of balloon?’ Shenanigan heard Cook say, almost to herself. ‘And are these . . . kettles?’

Shenanigan looked about her. In fact, the hall was full of kettles: kettles on hotplates, kettles on portable stoves, kettles set over Bunsen burners and balanced on radiators. The scene was so absurd and unexpected that Shenanigan felt a laugh bubbling

in her throat, a laugh that became a scream as the shape in front of her abruptly doubled in size. It was recognizable as a bird now, wings spread, though its de ated head still lolled over its breast as if its neck was broken. As air lled the body, the head snapped upright, bobbing in place and xing her with one golden, glaring eye.

Shenanigan took a step backwards. She heard Cook swear. Several of the kettles were beginning to boil. It was then, as the ridiculousness of the situation reached its peak, that she heard a squeal of brakes, a bang of a car back ring, and a bush sped past the front door at around forty miles an hour.

Shenanigan ran outside to see the bush turn a corner at speed, losing a couple of branches to unforgiving physics. Underneath the foliage was a van, blocky and old-fashioned, with a thickset gure in a sparkling black leotard clinging to the roof. A person with a long black plait hung out of the passenger window, looking to see if they were being followed.

‘OI!’ Shenanigan shouted again, but she already knew she couldn’t catch up. With smooth, sinuous grace, the gure in the leotard swung themself o the roof and through the open back doors of the van. The last

member of the group reached out to haul the doors closed, and for a second, their eyes met Shenanigan’s. That one second seemed to stretch on for an hour, until Shenanigan felt as if a whole conversation had passed between them – though one she couldn’t have recounted if asked.

Then the burglar gave her a small ironic salute and shut the doors. The van ung itself round another bend in the drive, and then it was gone.

Inside, the kettles were beginning to whistle. The bird’s wings squeaked as they pressed against the walls of the hall. Its eyes bulged. Shenanigan could just see Maelstrom and Fauna at the top of the stairs, each face mirroring the other’s ba ement.

‘Blow me down! Is anyone hurt?’ Maelstrom shouted.

‘I’m ne!’ cried Shenanigan.

‘Where’s Phenomena? And Schadenfreude?’

‘I’m here,’ creaked Schadenfreude, lurching down the stairs, beating back one of the in atable wings with her stick where it pressed against the banister. ‘For goodness’ sake,’ she shouted to Cook, ‘help me get this thing down!’

Shenanigan could see white stitching on the bird’s swollen belly. It strained and puckered, threatening to

split. The whistling of kettles became a scream as the built-up pressure reached one multi-pitched shriek, the enormous bird’s demented, wailing song, and then –

Shenanigan felt the explosion in her spine and stomach. Where there had been a huge bird, there suddenly wasn’t. In its absence, a shower of gold confetti rained down over the hall. It settled in her hair, and in the pools of spilled water. It settled on Cook and Aunt Schadenfreude, who were bent over a rattling electric air pump. Aunt Schadenfreude was hitting it with her stick.

Shenanigan picked up one of the pieces of confetti, a round disc of gold, like a paper doubloon. She looked up. Tattered strips of fabric from the bird’s body had caught on the chandelier, reminding Shenanigan unpleasantly of chicken skin.

Heavy footsteps announced Maelstrom. ‘Shenanigan, where’s your sister?’ he panted.

‘I don’t know.’

‘She’s not here. The intruders – did they take her? Did you see?’ Maelstrom looked on the verge of panic.

‘No. At least, I don’t think so—’

‘Think! We—’

There was a loud sneeze.

A dishevelled Phenomena appeared at the top of the stairs, blinking and yawning.

‘What’s all the noise about?’ She wiped her glasses on the hem of her lab coat, replaced them, and squinted down at the hall. ‘Oh, have we redecorated?’

‘Tell us again,’ said Fauna, pushing a cup into Shenanigan’s hands.

They were sitting on the grand staircase. There were so many kettles about that Cook had simply ducked down to the kitchen to get some teabags. Maelstrom was not yet convinced they were alone, and was patrolling the House with an ornamental sword, checking every room ‘for stowaways’. Aunt Schadenfreude was poking at the fabric from the bird with her stick, though it wasn’t clear what that was supposed to accomplish.

‘I dunno what else you want me to tell you,’ Shenanigan grumbled. ‘I was hungry. I came down to make breakfast – which I still haven’t had, by the way – and I found the ve of them setting up . . . whatever that bird thing was.’

‘You’re sure there were ve?’

‘Yes.’ Shenanigan closed her eyes, picturing them.

‘One of them was fat and graceful, in a sparkly leotard. One of them was very pointy at the elbows. One of them had their hair in a long plait, one had glasses, and one of them saluted.’ She shook her head in outrage. ‘They were all in black. I can’t tell you much more. I’ll nd them, though,’ she said darkly. The surprise was wearing o , and she was getting angry. ‘No one breaks into my House, leaves behind an in atable bird, and gets away with it.’

‘Yes, what was the point of that?’ complained Schadenfreude.

‘Maybe they were sending us a message,’ said Cook.

‘A threatening letter would have been clearer. And it wouldn’t have taken them as long to set up.’

‘They got in and out pretty quickly,’ said Phenomena. ‘Though I suppose they could have been in the House all night, waiting for us to fall asleep.’

Fauna looked ill. ‘We need to go over our security,’ she said. ‘Is this my fault? Is this because I took the chains o the gates?’

‘Of course not,’ said Maelstrom, returning from upstairs and patting her arm. ‘There’s no point blaming yourself. The important thing is that no one was hurt, and nothing has been taken.’