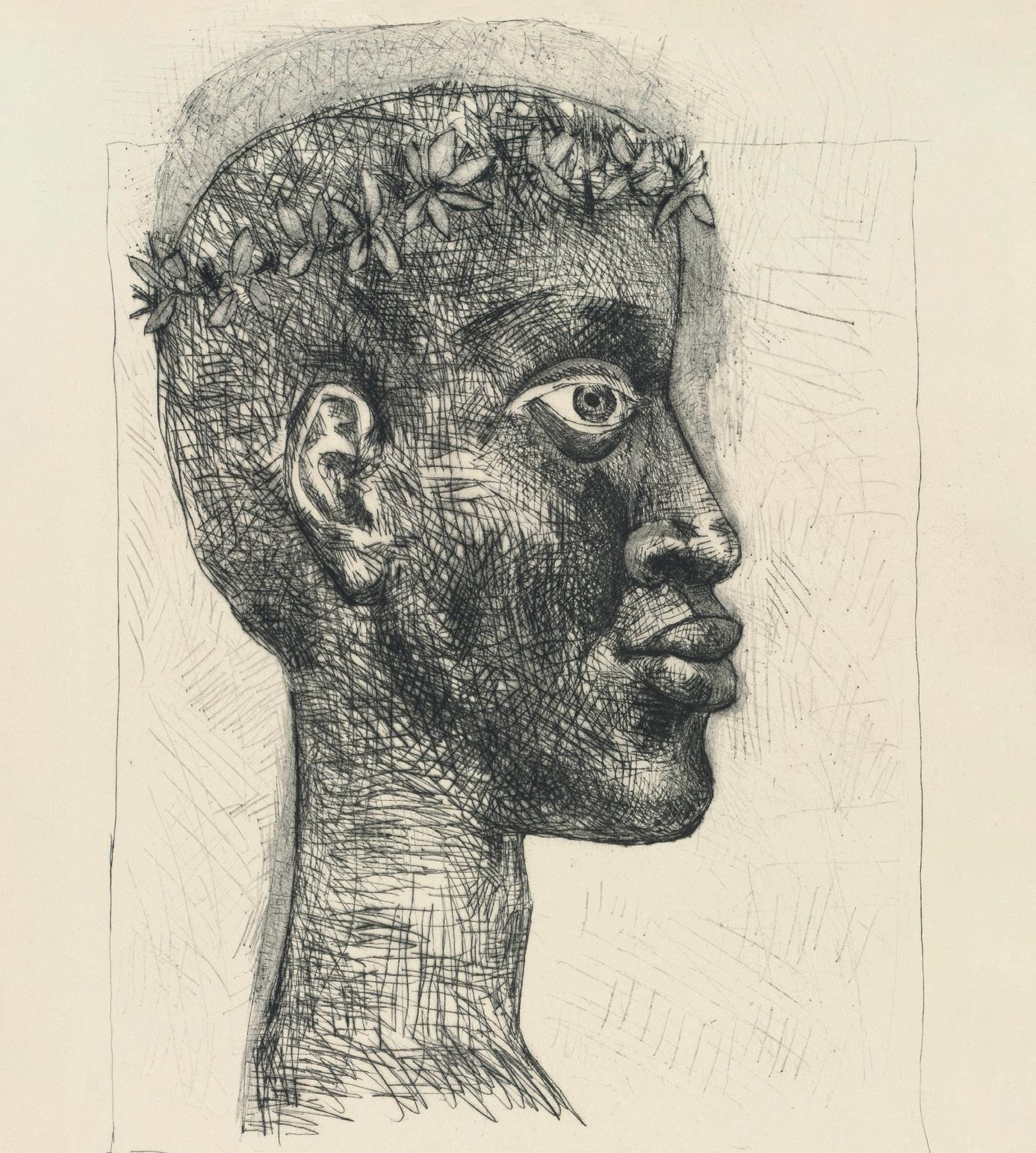

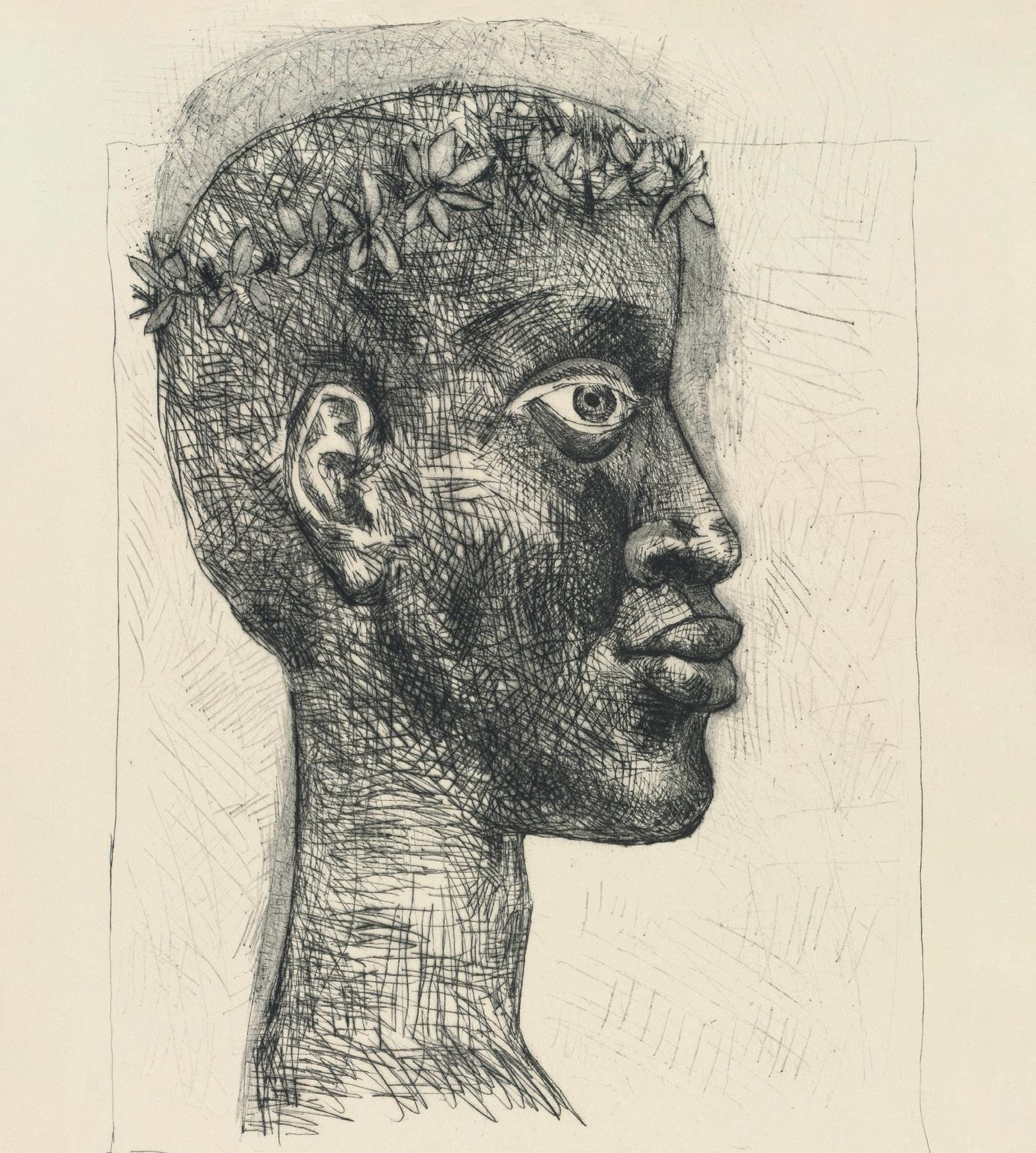

Return to My Native Land

MODERN CLASSICS Aimé Césaire

Return to My Native Land

Aimé Césaire (1913–2008) was a Martinican poet and politician who played a leading role in the struggle to liberate the French colonies of Africa and the Caribbean. Renowned for co-founding the Négritude movement, Césaire was a pioneer in surrealist poetry. His achievements as a writer were recognized worldwide with awards including the International Nâzim Hikmet Poetry Award, the Laporte Prize, the Viareggio-Versilia Prize for Literature, and the Grand Prix National de Poésie; in 2002, he was made Commander of the Order of Merit of Côte d’Ivoire. His works include the plays A Tempest (1969) and A Season in the Congo (1966) , the searing political essay Discourse on Colonialism (1956), and the long poem Return to My Native Land (1950), dubbed ‘nothing less than the greatest lyrical monument of this time’ (André Breton).

John Berger was born in London in 1926. His acclaimed works of both fiction and non-fiction include the seminal Ways of Seeing and the novel G., which won the Booker Prize in 1972; his collaborative translations include Brecht’s Poems on the Theatre and Mural by Mahmoud Darwish. In 1962 he left Britain permanently, to live first in Geneva, then in a small village in the French Alps. He died in 2017.

Russian-British intellectual and feminist Anna Bostock shared Berger’s life during the sixties and early seventies. She was born in China in 1923, moved to Vienna in 1936, then to England and, finally, to Switzerland, where she worked as a translator during the second half of the 20th century. The authors she translated include Brecht, Trotsky, Georg Lukacs and Le Corbusier, as well as Wilhelm Reich. She died in 2018.

Jason Allen-Paisant is a Jamaican writer, poet and academic who works as an associate professor of Critical Theory and Creative Writing at the University of Manchester. He is the author of two critically acclaimed poetry collections: Thinking with Trees, winner of the 2022 OCM Bocas Prize for poetry, and Self-Portrait as Othello, a Poetry Book Society Choice, which won both the Forward and T. S. Eliot prizes. His memoir, The Possibility of Tenderness, will be published by Hutchinson Heinemann in 2025. He’s the author of Théâtre dialectique postcolonial, and a second monograph, Engagements with Aimé Césaire: Thinking with Spirits, is published by Oxford University Press.

PENGUIN MODERN CLASSICS

Aimé Césaire Return to My Native Land

Translated

by

John Berger and Anna Bostock

Introduction by Jason Allen-Paisant

PENGUIN BOOKS

PENGUIN CLASSICS

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia

India | New Zealand | South Africa

Penguin Books is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com.

First published in French as Cahier d’un retour au pays natal by Présence Africaine 1956

Published by Penguin Books 1969

First published in Penguin Classics 2024, edited by Jason Allen-Paisant 001

Text copyright © Présence Africaine, 1956

Translation copyright © John Berger and Anna Bostock, 1969 and John Berger Estate, 2024

Introduction copyright © Jason Allen-Paisant, 2024

The moral right of the author of the introduction has been asserted

Set in 13/16.3pt Dante MT Std

Typeset by Jouve (UK), Milton Keynes

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The authorized representative in the EEA is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin D 02 YH 68

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN : 978–0–241–53539–4

www.greenpenguin.co.uk

Penguin Random House is committed to a sustainable future for our business, our readers and our planet. is book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper

Introduction

I open my old copy of the 1956 Présence Africaine edition of the Cahier d’un retour au pays natal – ‘The Notebook of a Return to My Native Land’ – and scan the first page of the poem. Immediately, I am brought back to the first time that I read it. I am a final year undergraduate at the University of the West Indies, and it’s the year 2000. I am eager to understand, but bewildered, as I hold the book open in a dark seminar room lit by tungsten bulbs in Mona, Jamaica. So many of the words are unfamiliar to me. On the opening page, larbins, hannetons, délaçais, and tourterelles are only a few of the words that are underlined. The poetry seems obtuse and I despair that I’ll ever understand the ideas it expresses, or the mind out of which they have come. Something does open up when I hear the recording of an extract of the poem. It might be from the archives in France; I cannot remember. Somebody is voicing it; perhaps Césaire himself. I begin to connect with it. I hear the beating of the tam-tam, slow and fast. I feel the meditative, plaintive sadness and

v

the surges of elation. But could this be enough? I hide my shame at not being able to connect with Césaire’s poem at the level of ‘thought’.

My second encounter with the poem, and the first time I properly understand it, comes about in Oxford in the autumn of 2011, the year in which I enrol for my doctorate there. I am in the midst of an experience of otherness, one with many colonial resonances. Along with three other people, I perform Return on the stage of a lecture theatre in front of an audience largely comprised of white British undergraduate students. There is a drum, played by an English drummer. Besides him, there are three people voicing the text: an amateur actress from France; a Frenchman who works as a secondary school teacher in Oxford; and me. We’ve chosen our parts, or have been assigned them, based on an audition conducted by one of the Fellows in French. My understanding of the poem grows. It’s an understanding not just of the words, but of their political significance – of the ideas that constellate around Négritude. Négritude is a term that Césaire himself invented. It reclaims and proclaims the cultural heritage of Black people throughout the world, affirming the value of African and Afro-diasporic history, and of African relationships to the natural and cosmic order.

vi Introduction

Introduction

It bodied forth a political awakening. It was in this poem, Return to My Native Land, published in Issue 20 of the Paris-based magazine Volontés less than a month before the outbreak of World War II , that Césaire would immortalize the word.

In time, I became aware that this poem inspired movements of liberation and cultural assertion across Africa and its diaspora. But above all, Césaire’s poem was about my body. It was a sound in which my body was at home. This enchanting sonic power (its rhythms suggestive of the drum, of chanting, of ceremony) is hard to strip away. Still today, even now that I understand the meaning of nearly all its words, I connect with this poem through its sound. Meaning, I approach it not just with my mind but with my entire body: the modulations, the silences, the chanting, the lyrical declamations, the lulls, the mournful passages, the changes in volume and in speed. It’s a poem that must be spoken aloud to be appreciated for what it is, a dramatic poem. I had this realisation while deepening my knowledge of Césaire’s plays in Oxford and observing the ways in which poetry and theatre converge in his oeuvre. As a corporeal aliveness, the poem entered my body. I could feel,

vii

living within me, its anger, the pride of its affirmation of selfhood, and the shock constituted by the discovery of Négritude, the loud, visceral cry that emerged from the need to affirm Black humanity. I could close my eyes and be transported to Martinique, the cradle of Césaire’s Négritude, but I’d also be transported to the inner-city neighbourhoods of Kingston, Jamaica, to landscapes of spoliation and devastation, such as those Césaire describes in the opening pages of the poem, linking them to colonialism and its lingering imprint on the land: the narrow streets [. . .] where the gutter pulls a face among the excrement . . . the river of life listless in its hopeless bed, not rising or falling, unsure of its flow, lamentably empty

A misery, this beach of rotting garbage, the furtive rumps of creatures relieving themselves

Besides this, I was struck by the exactness with which the poem conveyed a certain experience

viii Introduction