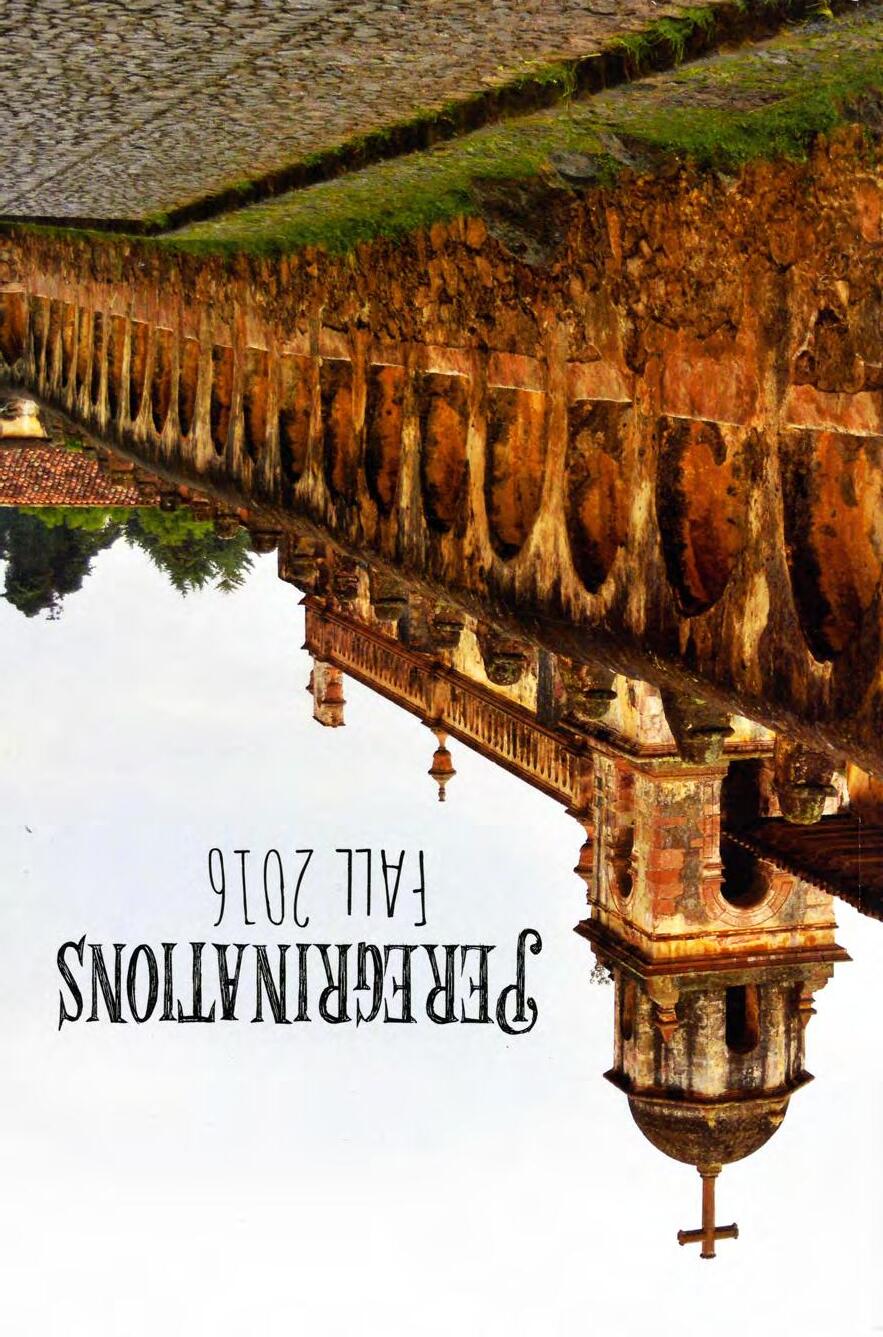

TEREGRINATIONS

covrn An : "MDI(O" ~yNA)HJAM AlVcH l

All artwork has been converted to black & white for print. Please visit www.folioslcc.org to view all of the content in its original form, as well as content published exclusively on our website.

fAll -101~

A))O(1AH D[AN: )HrHfN ~UffU)

fOllO ADV1)0t ~RANDON AlVA

llH~A~i rnnot ~fA1HER GRAHAM

Dt)lGN rnnot lONDA lEUNG

wrn rnnot ~RANDON WAlKER

fOlIO )14H:

1HA~A1A Df )lQUURA

Mf GHAN fl YNN

MICHMl GIRON

MICHfllf GRAY [MllY JAY (HR1)11Nf MAcrHER)ON KfNDRA NU11All

CAMERON ~AYMER

}O)HUA )C0fHlD

}UllANA )OU1HWICK ~ENJ AMIN WAllMAN

1Hrnc 1) WHAT I WOUlD [All THc Hrno JOU~NcY, [All THc NIGHT )tA JOU~NcY, THc Hrno ~Ut)T, WHrnc THc INDIVIDUAl 1) GOING TO ~nNG ronH IN HI) lIH )OMUHING THAT WA) NcVrn HHclD ~ffO~c .

- JO ) cr H[ AMr cll

I GUt)) THAT') THc THING A~OUT AHrnO') JOU~NcY . mu MIGHT NOT )TAn OUT AHrno, AND YOU MIGHT NOT cVcN [OMc ~A[K THAT WAY. BUT YOU [HANU, WHHH 1) THc )AMc A) cVrnYTHING [HANGING. !He JOU~NcY [HANU) YOU, WHnHrn O~ NOT YOU KNOW IT, AND WHUHrn O~ NOT YOU WANT IT TO .

-KAMI GA~UANo MAN') lAND · lINN lUKrn ·1

HMO1HY o: l O· KcNDRA Nun All ·3

)OGG Y}[AN) ·BRANDON WAlKtR ·4

lNNO[[N([ · Mrnrn11H HAR DY· o

1Ht DcrAR1URt ·MI[HAtl GIRDON ·10

1Ht ron ·1HA~A1A Dt )tQUtlRA ·lo

ruRnY IN rovrnn CHtl)H MARHNU. u

HO1 AIR BAllOON ·KIMHRW ruuNG ·10

l111lt BIRD· MADtllNt [Ole· A

OlD fOR1 lcWl) ·lAURtN lcA1HAM ·1o

1Ht )HAMrnA 1WtN1 ·BtN WAllMAN ·n

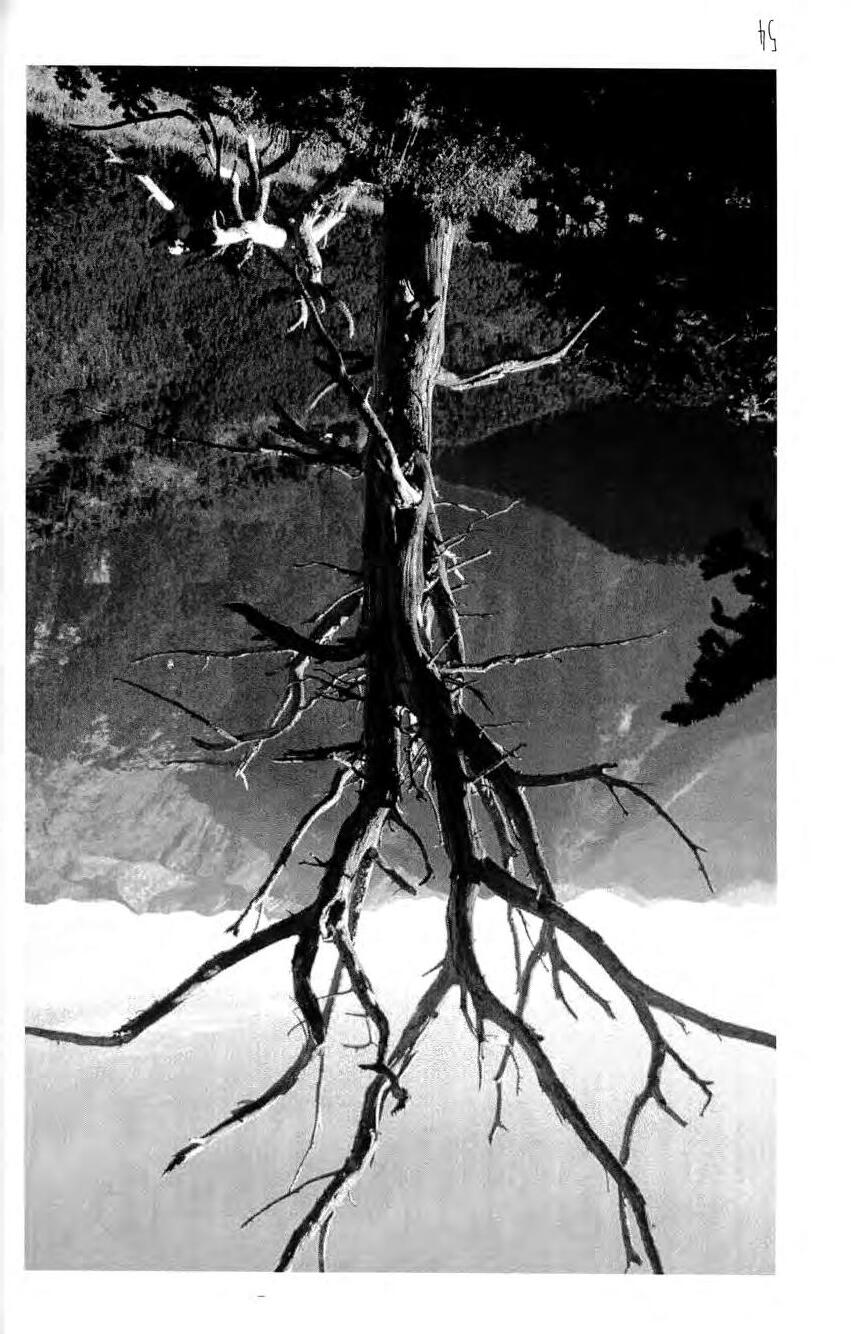

}U)1 ANO1HtR NA1URt lMAGt · BRANDON WAlKtR ·40

)IA~· HcA1Hrn G~AHAM · 44

(ON1rnl · ANNA-KO~~INc HAN(O(K · 4D

MAllN(Hc · KcNNc1H )AN(Hcl ·4i

rHAN10M · ANGclA fHlD) · JL

Hvrn HYMN· llNN lUKrn. )j

1Hc (Y[lc · McGHAN flYNN · )4

A)HONAU1 · (AMrnON ~AYMrn ·)D

low. KcND~A NUHAll · DO

flY AWAY BHDH. KYW )Her Am. D)

MINI A1URc lHc AMONG u) ·CAHO) BA~~rnA · DD

1Hc WOlf le mu NG KID) · [Mll YJAY · Di

(ONflDcN[c. ANNA-KO~~INc HAN(O[K · lO

Mnuo · NA)HJ AM Al vrnu · 14

M) M). JOHN-(HA~m (Ol TON KtUN c· lo

MAGNUI( N0~1H ·HcA1Hrn G~AHAM ·n

ll ~U IDA H·JmHA DOWNING· ~l

1HrnAr Y·KcND~A NUHAll ·

)KY rUll or lINc ·(AHO) BA~HDA -~4

HAN D.1 ·M((ADc GO~D0N · ~o

ODDITY. AlnAND~A Km.~~

~cAl lO Vc·DAVID iAN c) ·~1

Bcnrn WITH (OKc · A)HlcY MOAHAND · ~4

WAl1 WHITMAN· KAUIGH )T0[K ·%

o~~orn) ·[Hn)TlNe MMrHrn)0N ·100

I AM ~me· [llJ AH We)T ·10)

l0Nel y[l0UD. KAM~H rnrn ·lOo

OnAN VUlAGe ·}0)HUA WATT ) ·1oi

MADNm IN Arul ·DANNY l. ~UTHrnfOrn III· 111

1He INK 1m ·l0GAN AlVA ·114

1He rH0eNH ·[Hn)TlNe MAUHrn)0N ·llo

NOTH DAMe ·1HA~ATA De ~IQUernA ·11)

GHAT UHUATI0N) ·A)HlcY MOAHAND ·ln

M0~NING [0NHA)T. KIMH~W ruING. n~

Dmn 1WHIGHT IN WA H~(Ol0~ ·AnGAil MM)HAl ·Bo

the desert doesn't need justification for its existence like I do. when no one is listening, it still makes noise. the arid wind sings its solemn hymn with no one around to conduct it, coyotes howl and sigh to no one in particular about nothing in particular, dead brush whistles in near harmony with the breeze, birds yell overhead, ( dinner plans? selfish soliloquies? ) vermilion sand gets picked up and dropped elsewhere by some invisible goliath's handand this continues forever, without apology, until entropy envelops the earth.

·IMOTHY 6:10

KcND~A NU11 All

They suffocated under champagne chandeliers and jeweled spheres gasping for oxygen and grasping at God between gaps of guilt.

Yet their sheets of silk still keep them warm, during winter storms.

Ml[HAcl ~l~ON

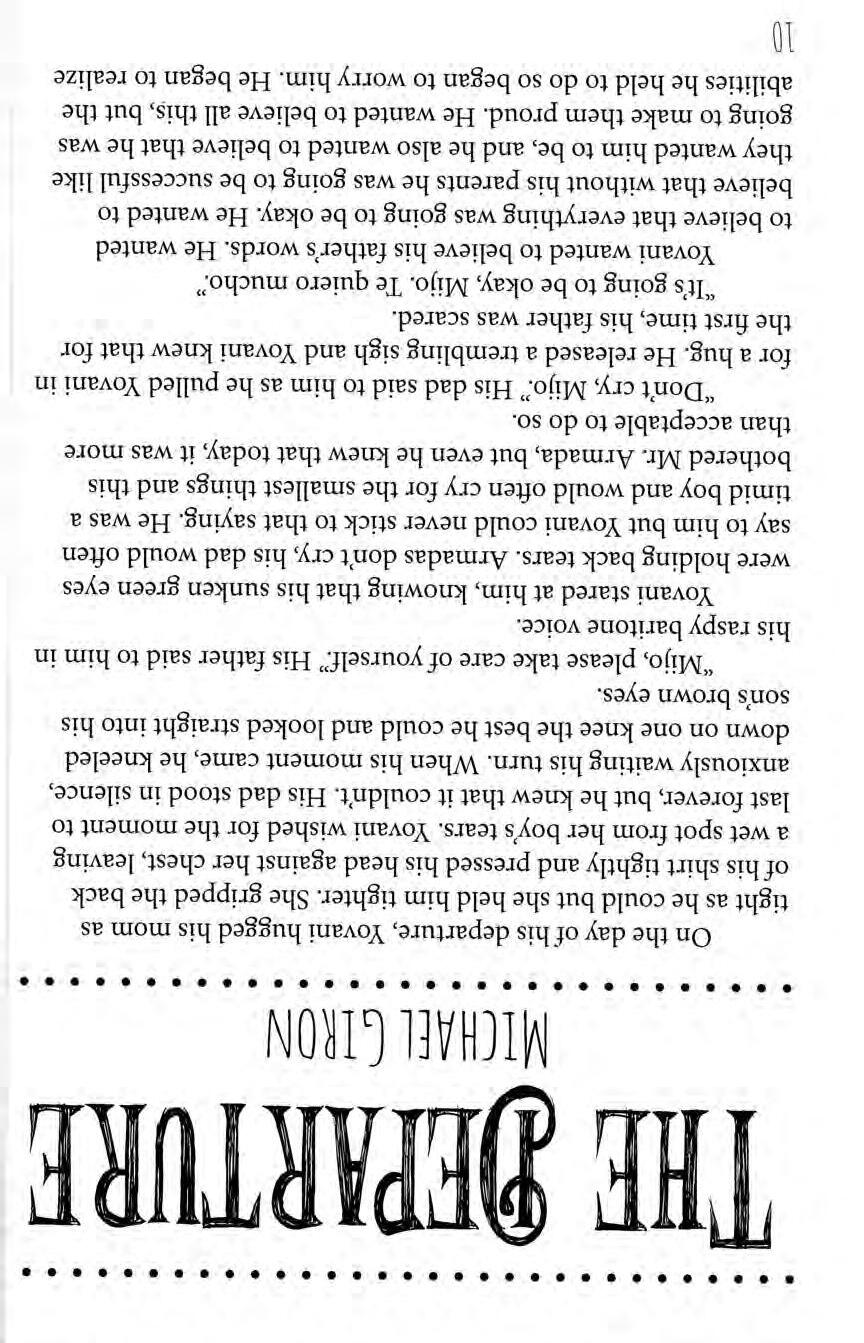

On the day of his departure, Yovani hugged his mom as tight as he could but she held him tighter. She gripped the back of his shirt tightly and pressed his head against her chest, leaving a wet spot from her boy's tears. Yovani wished for the moment to last forever, but he knew that it couldn't. His dad stood in silence, anxiously waiting his turn. When his moment came, he kneeled down on one knee the best he could and looked straight into his son's brown eyes.

"Mijo, please take care of yourself' His father said to him in his raspy baritone voice.

Yovani stared at him, knowing that his sunken green eyes were holding back tears. Armadas don't cry, his dad would often say to him but Yovani could never stick to that saying. He was a timid boy and would often cry for the smallest things and this bothered Mr. Armada, but even he knew that today, it was more than acceptable to do so.

"Don't cry, Mijo:' His dad said to him as he pulled Yovani in for a hug. He released a trembling sigh and Yovani knew that for the first time, his father was scared.

"It's going to be okay, Mijo. Te quiero mucho: '

Yovani wanted to believe his father's words. He wanted to believe that everything was going to be okay. He wanted to believe that without his parents he was going to be successful like they wanted him to be, and he also wanted to believe that he was going to make them proud. He wanted to believe all thi$, but the abilities he held to do so began to worry him. He began to realize

that without his parents, whose support and guidance had been with him all of his life, he wasn't going to be able to do it. He was only nine after all and the thought of all the responsibility began to weaken his knees and upset his stomach.

As the small family of three stood in the middle of an empty field of gravel outside of the city, where they were told to meet at noon, a bus began to approach them. The bus was similar to a school bus, yet its yellow paint job was absent. Instead, It's green paint reflected in the sun and the words "La Santa Maria'' identified it to be the right bus to take Yovani. The distant rumbling sound of the engine began to get louder and Yovani's heart began to beat faster than the bobbling heads inside the bus.

"Vamonos!" a man said to Yovani as he jumped out of the crawling bus before coming to a full stop.

Yovani became frightened by the man's appearance and his thunderous voice. He was known to many as EL Coyote and Raul to a few. Yovani had no desire to know the details. All he knew was that he was a bad man. He was the Mexican reaper who had come to take him away. The man was short with a mustache as thick as his curly hair and as black as the shirt he wore. His belly was held in place by a golden bull that had clearly been shined one too many times. From that point on, Yovani began to refer him as the bull man.

"Look at me;' said Mrs. Armada as she went in for a last hug, making it the strongest one of all. Yovani was not much of a hugger, avoiding them anytime he could but today he welcomed it, wishing it wouldn't end. Mr. Armada joined his family's embrace and the two parents soon peckered their son with kisses, knowing this would be the last time they would ever see or hold their only son.

"Vamos, Vamos, Vamos!" The Coyote shouted after giving a high pitched whistle that scared some nearby ravens.

It was time to go and so Yovani, more scared than he was on his first day of school, picked up his handwoven backpack made for him by his mother and began walking towards the Santa Maria.

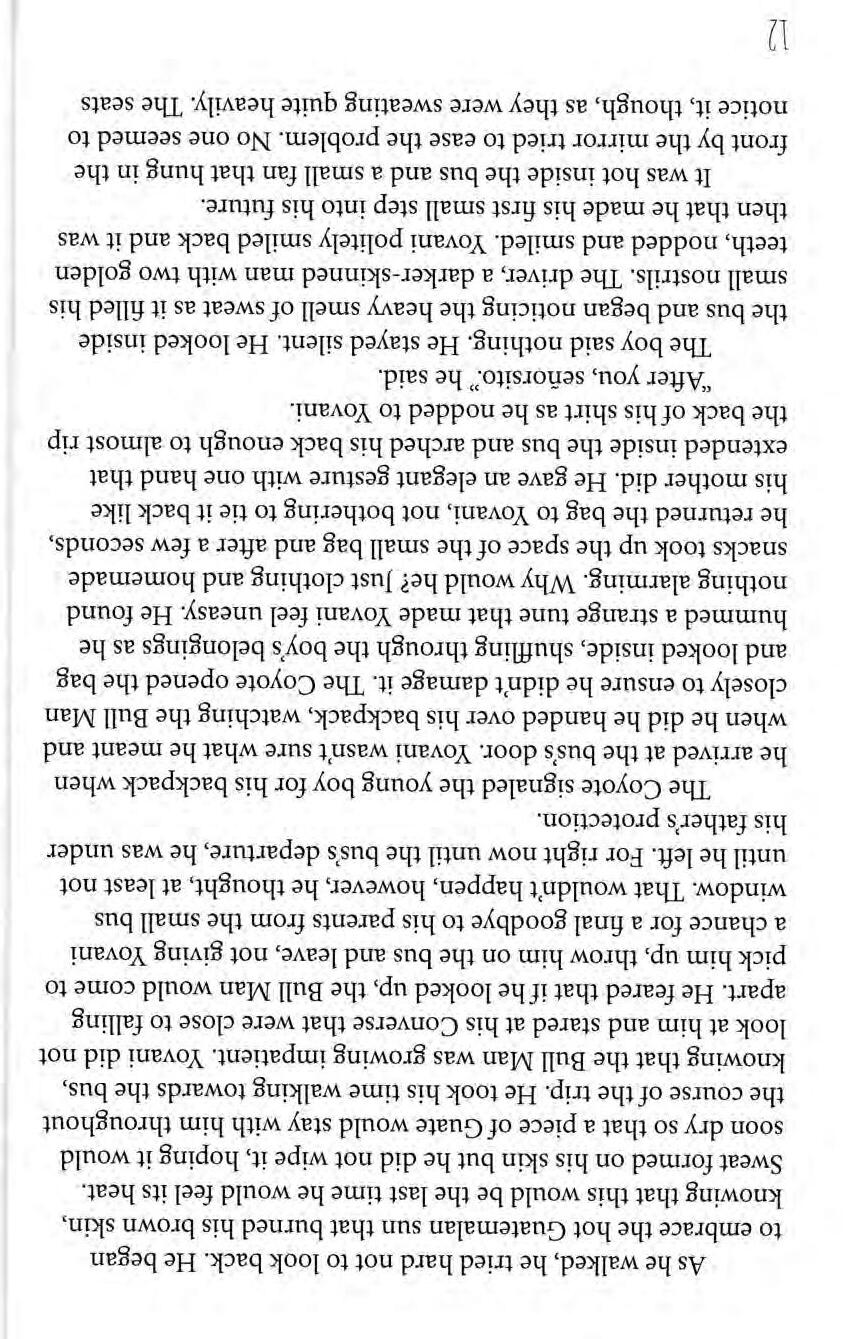

As he walked, he tried hard not to look back. He began to embrace the hot Guatemalan sun that burned his brown skin, knowing that this would be the last time he would feel its heat. Sweat formed on his skin but he did not wipe it, hoping it would soon dry so that a piece of Guate would stay with him throughout the course of the trip. He took his time walking towards the bus, knowing that the Bull Man was growing impatient. Yovani did not look at him and stared at his Converse that were close to falling apart. He feared that ifhe looked up, the Bull Man would come to pick him up, throw him on the bus and leave, not giving Yovani a chance for a final goodbye to his parents from the small bus window. That wouldn't happen, however, he thought, at least not until he left. For right now until the bus's departure, he was under his father's protection.

The Coyote signaled the young boy for his backpack when he arrived at the bus's door. Yovani wasn't sure what he meant and when he did he handed over his backpack, watching the Bull Man closely to ensure he didn't damage it. The Coyote opened the bag and looked inside, shuffling through the boy's belongings as he hummed a strange tune that made Yovani feel uneasy. He found nothing alarming. Why would he? Just clothing and homemade snacks took up the space of the small bag and after a few seconds, he returned the bag to Yovani, not bothering to tie it back like his mother did. He gave an elegant gesture with one hand that extended inside the bus and arched his back enough to almost rip the back of his shirt as he nodded to Yovani.

''After you, sefi.orsito:' he said.

The boy said nothing. He stayed silent. He looked inside the bus and began noticing the heavy smell of sweat as it filled his small nostrils. The driver, a darker-skinned man with two golden teeth, nodded and smiled. Yovani politely smiled back and it was then that he made his first small step into his future.

It was hot inside the bus and a small fan that hung in the front by the mirror tried to ease the problem. No one seemed to notice it, though, as they were sweating quite heavily. The seats

were nearly empty, only being filled by a woman in the back a young boy with his mother towards the middle. The boy stared at Yovani as he slowly looked for a place to sit. When Yovani saw the small boy and his mother next to him, he began to wish that his situation was like theirs. He wished that his parents were with him but he knew that he couldn't hold his breath for such fantasies, and so he began to walk toward the family of two as he looked for a seat.

After sitting down and placing his bag beside him, Yovani looked outside the window and waved to his parents. His mom waved back but he could see that his father had walked over to the Bull Man and handed him a white envelope. The Bull Man grabbed it and placed it in his back pocket, not bothering to shake his father's hand. The Bull Man walked away disrespectfully and his father turned to wave at his son, not letting such rude gestures bother him. Yovani knew what the envelope was. It was the hard work and sacrifice that his parents had made to make it possible for him to be leaving. He knew that inside that envelope was a neat stack of Quetzals, waiting to be spent by the Bull Man and he knew that even though it was a lot of money, it still wasn't enough to cover the cost for the Coyote's guidance and assistance.

Yovani's parents waved at him and he waved back through the small bus window. Yovani saw their bodies becoming more and more distant and eventually disappearing along with the Capital city of Guatemala. He gripped his backpack and wiped his eyes, trying to hold the memory of them as clearly as he could.

"Oye, what's your name, nifio?" he heard a voice say to him from behind after a few minutes had gone by. He turned around and saw the small boy poking his head from the top of the ripped bus seat.

"What?" Yovani said, even though he had clearly heard the question.

"What's your name? Como te llamas?" he said in a cheerful tone that made Yovani wonder why he would be in such a mood.

"Yovani;' he said in a low voice that could almost be mistaken for a whisper. He stayed silent after his response. The boy stared at him, waiting to be asked the same question. When it didn't come, he shifted his body and continued the conversation.

"My name is Joaquin and this is my neighbor, Elma:'

Yovani was surprised, only noticing the lack of resemblance in that moment. Elma turned and gave him a smile.

"Nice to meet you, muchacho:'

"Nice to meet you:' Yovani said to her as he began to feel more at ease.

"Elma lived a few blocks from my house so I've known her for a long time:'

Yovani nodded his head, trying not to be rude, but it was clear that he didn't feel like talking.

"So what are you going to do when you cross--"

"-Joaquin, ya. I think that's enough for now. Let's leave him alone for a bit:' Elma whispered to him loud enough for Yovani to hear.

Without showing it, Yovani thanked Elma for understanding that he needed time to himself. He wasn't in the mood to talk and he wasn't sure if he would ever be.

"Sorry, muchacho. Joaquin likes to talk a lot and make new friends:'

"It's okaY:' Yovani said, wishing he had more to say to them both.

"We brought quite a few things along for the trip so if you need anything at all, don't hesitate to ask, okay mijo?" Yovani nodded.

"We have food, water, and extra clothing for Joaquin that I'm sure would fit you as well. We will let you be. Let us know if you need anything, muchaco:'

"Thank you., said Yovani, overwhelmed at the woman's generosity.

The boy sat back down and began to open a bag of chips. The smell of the chips reached Yovani and his stomach began to

turn again. He opened the small window for air and was hit with a dirty batch of air. He squinted his eyes and looked around for a few seconds. He did not know where he was but then again, that was the point. As he sat in his seat he began to think about all the things that he was leaving behind. He knew he was going to miss the sharp sound of rain hitting the tin roof of his home each fall, or the cold showers that he was forced to take each morning because of the lack of hot water. Even though he wished for more when he lived with his parents, he still had all that he needed to be happy. Food was always on the table and love was never absent even when the money was. All his wishes of electricity, a television or video games began to fade as he sat on the bus. All he wanted was his soccer ball that had been loyal to him all those years and his soccer shoes that his parents had worked so hard to get.

That's why they worked long hours for him, scraping enough money so that he could have a better future. He knew that if they could, they would have come with him, but the constraint of money kept them in the brick structure with a tin roof that they called home.

Yovani knew that it was going to be a new beginning and he couldn't fail. He sat in the bus, dreaming about the success that he could have as he made his way to the first of many safe houses. If all went well, he would be arriving at his aunt's home in two weeks or so. The road ahead worried him but not as much as his failure did. He had heard many stories from people in his town about those that didn't make it, or about those that did but later returned. This frightened Yovani and he didn't want to be one of those people and so he tried to keep a positive attitude. He had to toughen up and do what needed to be done. He knew he was going to make it. He had to. And so, Yovani closed his eyes and began to dream about his life on the other side of the border, making his parents proud of what he had finally become: an American.

HE OET

THA~A1A D[ )IQU[HA

[Hcl~Ic MA~11Ncl

KIM~c~lct rilllNG

ITTLE IRD

MADclINc [Ole

she held the little bird in her hands, cupped together like a child scooping up water in the bath.

trembling hands with snowcapped fingers, iced white by the trembling heart that didn't dare pump its blood toward the bird.

she stared with awe and terror amazed and grateful to be so close to something so pure yet horrified, so horrified, she'd forgotten how the little bird got there. she was afraid she had captured it .

.she dreamt the little bird would soar over the hills of her, dying leaves and bursting capillaries, leaving the mountains flushed red overnight, like the red that greets a lover from the mirror in the morning.

she watched the little bird ruffle its wings as the wind grew too cold to sustain life, the dens of the hibernating animals the only habitable spaces.

flocks of crows drug the bitter northern air through the trees

sucking the life from the veins of the leaves, leaving a splotchy trail of autumn colored devastation. she felt' the snowcapped mountains creep closer, a shiver of familiarity down her spine. but these mountains are too cold for little birds, even in the hands of a young child .

the little bird flew south to keep himself alive. she'd never been fand of the south, bright rays of sunlight to illuminate imperfections, and thick, wet air that could drown a girl whose thoughts don't know how to swim. she'd always felt the north was all she deserved, never lived anywhere else, never cared to fly away for self-preservation, always burrowing deep in the snow, finding comfort in attempting to live off the small fire buried deep within her frostbitten corpse, oblivious to the return of warmer winds. she'd watch the flocks of little birds soaring through the sky, wishing to be with them, but knowing she'd rather stay burrowed in the snowcapped mountains of the north, where her trembling heart could never cause her trembling hands to harm the little bird.

'LD · ·ORT EWI

lAU~cN lcA1HAM

THE ~cN WAllMAN

It started on the third day of school, with a plane crash under the monkey bars . Twelve children lay prone, eyes shut, tongues hanging out , while on their lunch break. The teachers who asked what was going on were given blank stares and the explanation that two planes had hit each other and one plane's wing broke off and then the plane crashed and everybody's dead. The deceased, all between six and ten years old, stayed that way until the end of their break. When the bell rang they calmly go up and, chattering happily with each other, went inside.

It happened again the next day with more children participating. It kept up for the rest of the week, each day with more players. Teachers expected it to run its course and end, replaced by some fresher game. Instead, the game spread across the playground a little farther each day. An epidemic of tragic death had taken over Hawthorne Elementary School.

They died of old age and sickness. They were the victims of horrible circumstance. Some were murdered. As the weeks wore on the rules of the game grew more elaborate. Some children played but didn't die. Instead they were the guilt ridden driver who had fallen asleep at the wheel, sitting a few feet from the innocent life they had taken, wracked with sobs until the game ended. Different parts of the playground were reserved for different styles. The baseball diamond was strictly for accidental death . Murders happened near the drinking fountain. Children eaten away by incurable diseases kept to the basketball courts. The dead never spoke to each other, didn't respond to anything that happened around them until the bell brought an end to their game. The only constants was the swift finality the bell brought and the immediate cheer that the kids showed when the game was over.

It had gone on for almost a month before some of the parents

started to notice, and complain. They voiced their concerns in e-mailed manifestos to teachers. They whispered to each other, heads leaned in until their foreheads almost touched, as they waited to pick up their kids at the end of the day. Rumors started to spread about it: that it had been started by a boy whose father had just died, that it was a reaction to the burden that the children felt attending such a highly-rated elementary school, that it was caused by too much TV, not enough sunlight, fluoride, gay marriage.

Anxiety rolled in like a fog, blanketing the school. Lessons slowed to a crawl. Homework was returned ungraded. The more neurotic staff began to suffer from mysterious ailments, taking sick day after sick day. They tried volunteer supervisors at recess. They sent home pamphlets designed to help initiate a dialogue with children about death and tragedy. They banned recess in favor of a series of in-class activities designed to build self-confidence and improve teamwork, which the children steadfastly played dead through. Despite all efforts, children played dead in droves. Each day that passed the causes grew more sophisticated, the anguish more nuanced.

Principal Kathleen Freck was certain that she was going to be fired any day. She no longer answered her office phone and she counted herself lucky when none of the messages waiting in her email inbox called her a bitch in the subject line. She spent most of her time shut in her office in a state of constant dread, almost wishing something horrible would happen to spare her the anticipation. Work had slowed to a crawl, school staff spent most of their time trying to avoid the belligerent parents that had almost taken over the school. By the time the afternoon bell rang, worried mothers and fathers were lined around the block, the sidewalk so crowded with people it almost looked festive, until you noticed the pacing, the nail biting, the forced . smiles.

Emergency PTA meetings were held twice a week. The meetings were mostly a venue for parents to yell at staff members with an audience. Principal Freck was always there, along with one or two staff members who had been bullied into attending. At a Thursday meeting in early November Principal Freck watched with mounting fear as the crowd squirmed with impatience, waiting to begin. She watched the second hand of the clock tick towards their seven o'clock start tinie like a prisoner on death row.

Immediately when the face showed seven the crowd fell into a hostile silence. Principal Freck stood and approached the podium. Her face couldn't decide if grim seriousness or levity was more appropriate, and spasmed back and forth between the two.

"Hello. I'm glad so many of you care so deeply about your children's education and well-being that you make time to attend these meetings:' She tried to seem approachable but stern, the crowd regarded her with 300 pairs of dolls eyes.

"I understand many of you are upset, I assure you we at the school are treating this issue with every bit as much care as any of you:'

A man scoffed from the first row. His outburst set the rest of the crowd to fidgets and murmurs, like he had broken the dam that held them to the conventions of politeness. The principal, used to small interruptions, continued.

"While we haven't found the right solution yet:' rumbles of ascent from the crowd, "we are confident that we are confident that we will find an answer. And now if you'll give a hand to Mrs. Hopper, the P.E. teacher, she has some exciting things to tell you about implementing yoga and meditation into our Physical Education Curriculum:'

Mrs. Hooper took the stage in stony silence. Principal Freck watched her address the parents. Mrs. Hooper attempted to illustrate the proper method for Ujjayi Breathing, which she assured them was proven to lower stress levels and promoted calming energy. She said she had been teaching the technique to the children with great success. The crowd did not look impressed.

Principal Freck was, for once, glad to feel her phone buzz. It gave her an excuse to leave in the middle of Mrs. Hooper's demonstration. The P.E. teacher had begun to move through a series of yoga poses she said had been specially designed for children. Principal Freck thought she looked like a fish lost on the deck of a boat.

Principal Freck returned to the auditorium to find Mrs. Hooper executing a spirited gymnastics routine and talking about the dopamine release caused by physical activity. It looked like a scene from a vaudeville routine. She walked to the podium.

"Thank you, Mrs. Hooper, I'm sure that will all be very beneficial for the children. I think that shows just how comprehensive our strategy is for dealing with this. We are focused on creative solutions and outside the box thinking. To that effect, I have just received a phone call from

someone who has agreed to come in and help. Dr. Andrew James has agreed to spend a few weeks at our school offer his considerable insight into how we should move forward:' For the first time in weeks of PTA meetings, her smile was real.

The crowd broke into whispers, those who recognized the name enthusiastically informed their neighbors of the Doctor's reputation. Some of the parents even smiled. After a brief question and answer session, people began to leave the auditorium in pairs or little groups. A few stopped to shake Principal Freck's hand. Everyone present seemed confident that the problem was all but solved.

Dr. Andrew James, renowned child psychiatrist, daytime TV fixture, New York Times bestseller and local celebrity had agreed to come to the school. His first email to school staff highlighted, "How much he looked forward to observing such a strange phenomenon occurring in his own backyard:' He would start by observing the normal recess periods each day until he felt he understood enough to make a recommendation. They found a small unused room in the basement for him to use as a temporary office.

Dr. James arrived at promptly nine o'clock the next Monday. Dressed in a sharp navy suit, his yellow visitor pass pinned to his lapel, all the charm and confidence that made him a fixture on morning talkshows on display. Parents and staff loitered by the front of the building, hoping to catch a glimpse of the doctor.

He deposited his small briefcase and laptop in his new office in preparation for his first observation of recess. With ten minutes to · prepare, Dr. James wandered the halls. He stopped to look at art projects pinned above lockers, waiting for the bell to ring. When it did, the flow of children pouring towards the back doors parted around him like he was at the broad hull of a ship, parting a sea of vibrant waves.

He followed the last of the children outside and found the game already well underway. Most of those still standing were in the midst of their death throes. One little girl near him fell to the ground, holding her head, with the deliberate grace of a dancer. A boy lurched, gut shot by invisible murderers, along the sidewalk towards a strip of lawn. He fell to the ground with the grass just beyond the reach of his outstretched hand.

Dr. James' eyes swept over the playground. The children mostly laid on the ground, a few knelt or paced near their reposed friends. The

doctor walked over to a boy curled into a ball under the monkey bars, clutching his chest, his face frozen in a pained gasp. A little girl with downcast eyes sat nearby. She turned to the doctor.

"He smoked too many cigarettes, he smoked ten in a row and they burned up his lungs and he died."

The doctor nodded. He pulled out a small pad of paper and began to take notes, raising his head every few seconds to look at the boy. He noted the posture, he guessed the age and ethnicity, he didn't ask any questions.

At the base of the slide three kindergartners laid in the bark chips with their limbs splayed around them, a fourth knelt holding his head in his hands. The little boy raised his head, eyes glistening with tears. Explaining to him between gasps.

"I couldn't stop. I forgot to get my car fixed. It broke and I couldn't stop and I hit the mommy and daddy while they were walking with their bab/'

He began to sob, deep in his chest, tearing up handfuls of bark that slipped through his fingers and fell to the ground. Dr. James approached him.

"Why didn't you get the car fixed?"

There was no response. The boy didn't even turn his head or acknowledge he had heard anything. Dr. James pressed a bit further.

"Well, could someone have done something to change it? Is it anyone's fault?"

He didn't expect a response and he didn't get one.

Dr. James wandered the playground for the rest of recess. He was able to get stories from the bystanders or grievers in three more scenes. He heard the stories of the victims of a zoo accident, an accidental poisoning, and what sounded like an eight-year-old's description of cancer. Dr. James took notes and asked a few more questions that went unanswered.

When the bell rang all the children immediately stood up and began talking to each other. They laughed at the new inventions of their classmates as they marched inside to line up single file, waiting to be led back to their classrooms.

After attending all three recess periods at the school every day for a week, Dr. James was able to make some early observations. He noticed patterns that fell in line with general opinions he held about

children. A tendency towards fairness emerged in their acting. Each child seemed to have their moment to shine in each of the roles they had devised. A child that spent two days as the hapless victim of circumstance was likely to be the perpetrator of a grisly murder the next. The death tableau's held to the social hierarchy of the school, popular and unpopular children kept to their own class when playing. The stakes of the game were as high as they could go. No one ever survived, every accident was lethal.

Apart from generalizations about children's play in general, Dr. James had few insights. The children did not seem depressed, consumed violent media at a below average rate, had a lower rate of parental divorce than the national average, consumed less refined sugar, slept more, cried less, ate better.

For a time he explored the hypothesis that it was the kid's advantaged upbringing that had created this obsession with death. But he could find no reports of anything like this occurring in any group of children, either those more or less closely parented than the ones at Hawthorne Elementary. He had the water tested, the paint tested, the food tested. He interviewed faculty and staff individually. He sat in on PTA meetings and took notes on the questions the parents asked. The weeks rolled by.

Without any promising leads, Dr. James hoped the game would subside as fall gave way to winter. Instead, when snow fell, the children simply bundled themselves tightly and laid in the drifts. He sat and watched them one recess, looking like brightly colored islands in a sea of white, and realized he had no idea what he was doing.

The tone of the questions asked by school staff had become more frantic. Polite email exchanges had given way to all caps demands for some piece of information to give to parents who had lost much of their initial awe of the doctor. He stopped checking his email. Letters started coming to his office in bundles, held together by rubber bands stretched to bursting, little of it was civil.

Long, solitary, after-dinner walks had become part of the doctor's routine. His wife was used to his need for reflection when it came to difficult cases, but began to worry as the walks took her husband farther afield from their spacious mid-century home. A few times she could smell liquor on his breath when he finally came to bed, often well past midnight.

Christmas came and went. All it brought to the playground was a house fire caused by a dry Christmas tree, an electrocution caused by a faulty strand of lights, three car crashes on icy roads on the way home from grandmother's house, a handful of Holiday dinner chokings and one boy who was gored by a reindeer. Principal Freck was thoughtful enough to send Dr. James a German copy of the DSM-3 with all instances of the word "kinder" highlighted in red. Neither the doctor nor the principal spoke German.

Recess had grown to become a refuge for Dr. James. He liked the quiet stillness that hung over the playground like a blanket, the unbroken peace that reigned from bell to bell. The children had become so disciplined that few even made eye contact with him unless he asked them a direct question. He had begun to look forward to the time he spent wandering there, alone in a crowd of two hundred.

Dr. James had begun to see that the game had a logic to it that dwelt just beyond the edges of adult's vision. A rightness just beneath its surface that defied explication, a hermetic perfection that made the children, in the eyes of Dr. James, into something like tiny monks whose delicate frames were the only instruments finely tuned enough to render a fundamental truth into a form normal eyes could see. Andrew would stand unmoving sometimes, in the center of a calamity frozen in amber, and spin in place, soaking in a feeling of peaceful repose. He felt a necessary part of the game, a player whose purpose was to observe, whose presence elevated the game past frivolity and towards some higher purpose that only another more distant witness could perceive. Until the toll of the bell made the playground rise as one. And the children spoke to each other in a language that Andrew could barely understand.

Sandra James had begun to seriously worry about her husband. His home office looked like it belonged to a detective on the trail of a serial killer. Pictures were pasted on the walls with excerpts from psychiatric journals pinned underneath them. A whiteboard was covered in theories, some written on top of half-erased earlier ideas. Underneath the desk, she found three empty bottles of vodka. Her husband had drank nothing but scotch or wine since before they were married.

In mid-January Dr. James received permission from the PTA to photograph students for his research. In truth, his pictures had nothing

to do with his attempt to offer a diagnosis. Instead, he took photographs merely for the frozen moments of beauty they showed. He flipped through them in his office, admiring the student's dedication and craft. He especially liked the photos he had taken of students in transition, changing in an instant from life to death or death to life.

He was looking at a picture of a Fifth Grade boy, pushing himself up onto his elbow, his face melting into a smile from the blank slackness of death as recess ended. Principal Freck peeked her head around the edge of his doorway, clutching the frame for support. She smiled nervously. He placed the photo back in the red folder where he kept the photos he had taken during recess.

"Hello Dr. James:'

"Hello Kathleen, and again, please call me Andrew:' He smiled back at her.

She nodded politely at him. "Right. Andrew. It's funny, I forget because they always call you Dr. James. On TV. When you're on TV I mean:'

They sat there, nodding happily and smiling at each other for a few more seconds. Principal Freck's fingers drummed a manic beat on the door-frame.

"Say.. .I have been hearing a lot about you lately. A lot of questions, from parents. They, they're just so anxious to hear about any progress you might have made. You might even say they're pushy, or angry maybe:' She laughed, a short staccato burst exactly in time with her drumming fingers. "I was wondering myself if you had anything. Insights or, you know, theories:'

"Oh, I see. Well, not just yet. It's important not to jump to conclusions on these sorts of things:'

Principal Freck wilted against the door.

'Tm sure. Medicine is such a delicate field, I understand. I was just hoping ... Some of the parents have been contacting people with the district, they're trying to get me, moved. I thought maybe if you had something .. :'

She walked into his office and fell into the chair facing his desk. She brought her hands to her forehead and attempted to smooth away the wrinkles. Dr. James could almost see the weight she carried, a thousand little potential disasters that she shouldered every day. A mounting burden that she would carry as long as her life was still the

one she wanted.

"Well Kathleen, if that's the case I suppose I could have something, preliminary findings of course, fairly soon. I have enough material': he patted the red folder on his desk, "to put something together in, I'd say a week:'

"Oh really? Well, that's just terrific! We'll have a staff meeting and invite a few of the more active PTA members. How about next Thursday?"

"Thursday? Yes, I think Thursday will be fine:'

"This is great, I knew you'd have something. To be honest, if you didn't I'd probably be out of a job by the end of the month. Well, I'll let you get to it:'

She stood up and left, giving the desk a friendly slap on her way out. Dr. James listened to the click of her heels recede down the hallway. He opened the red folder and took out a few of the pictures, placing them in a three by three square in front of him. He stared at them for a while, then slowly lowered his head to rest on the desktop .

A few of the Sandra and Andrew's close friends came over for dinner Sunday night. Andrew was as happy as Sandra had seen him for months. He was gregarious, loud at times. Telling jokes and slapping backs and cajoling everyone to stay for just one more drink. She barely recognized him. It was like someone else was wearing the skin of her quietly confident husband.

She tried to talk to him about it the next morning, but he was gone before she woke up. The week before the presentation he was an almost permanent fixture at the University Library, deep into studies of abnormal child behavior. For the first time in weeks Sandra felt like everything would soon be back to normal.

Dr. James barely left the library that week. He would arrive when they opened at seven and stay til close at one A.M. The only time he left was to buy styrofoam containers of noodles from the 7-11 across the street. He hadn't done research this intense since he was a graduate student.

Wednesday evening found him still in the university library, surrounded by stacks of medical journals and textbooks, quietly having a panic attack, no closer to figuring out what was going on. He was on the verge of scattering the entire stack across the floor. When he felt a tap on his shoulder.

"Excuse me, you're, you are him, right? Dr. James?" A short girl with a stack of books in her arm asked him.

"I uhhh. Yes, yes I am. Very nice to meet you, who might you be? " His feelings of panic were hidden by the force of his charm , which flicked on after a shudder, like a fluorescent light.

"Elizabeth, Liz. I'm an undergrad in the Psych program here. This is a bit strange, I remember seeing you on TV when I was in high school, talking about the pathology of psychopathy. I was fascinated:' Her smile was bright and eager. She was the first person Andrew had talked to for two weeks who wasn't mad at him .

"That's very flattering. Please sit, you'll spare me from this dull research for a moment:' ***

The sun shined through the window in a way that finally woke Dr. James at 12:30. He opened his eyes to stare at a strange ceiling. He had slept on the floor, still in h is suit and loosened tie, surrounded by empty beer cans. Leaning up with great effort, he tried to rub the sleep from his eyes and the memories into place. He remembered the greasy pizza place with the dollar beers Liz had taken him to as a break from research. He remembered the dive bar where she called her friends, all psychology undergraduates in awe of his credentials , to meet them. One of them, Derrick, kept buying him boilermakers. He dimly remembered the beers they had picked up after last call to take back to Liz's apartment , where he had asked if he could kiss her, then a black curtain that rolled down heavy in his mind, then nothing.

He made his thick limbs carry him to the bathroom and came out fairly sure he hadn't cheated on his wife. The couch creaked as he flopped into it. He looked at his watch and tried to remember what he had to do today. The thought crawled up from stomach: the meeting with Principal Freck and the PTA in an hour.

The taxi pulled into the school parking lot ten minutes after the meeting was supposed to begin. Dr. James ran to his office to gather some papers . and notes that he hoped would let him talk long enough to get through. As he turned the corner towards his office he nearly collided with Principal Freck.

''Andrew where have you, what are you . .." She trailed off as she took in his appearance . ''Are you , is that smell, are you drunk?" She

looked at him like she had found an injured penguin roaming the halls of her school.

"No. Well, maybe a little. And before you ask, I have no idea. I don't know how this happened. I don't know why I did this. We'll get through, buy me ten minutes to clean up and I'll get through. Kathleen:'

"Ok. Alright. I'll tell them you have the flu, give me five minutes and we'll reschedule for next week. Just make an appearance and give me five minutes and be ready for next week. Andrew, why did you? Are you alright?"

"Yes. No. I might be later. I don't know:' Principal Freck grabbed his hand and squeezed once, "Be there in ten minutes:' She walked briskly back to her office to the six angry parents she knew were waiting for her. She peeled her face into a smile for them.

He's here! Unfortunately, Dr. James is tangling with a rather nasty flu. He's ready to present today but it might be a bit quick. He's promised to have a full presentation next week, though:' She smiled brighter under their glares.

They waited in silence for fifteen minutes. When the two o'clock recess bell rang, Kathleen began to get worried. She pretended to excuse herself for a bathroom break and went looking for Dr. James. His office was empty, scattered across the floor were the pictures he had taken. His suit jacket and tie lay balled in the corner. She picked up one of his notebooks and found it filled with children's rhyme games and the possible things one might die from. She took the notebook and slammed the office door shut.

She ran to the front doors of the school, hoping to catch him in the parking lot as he tried to leave. Scanning the lot, she couldn't find his car or a taxi that might have picked him up. She was ready to go back inside and face the parents when she saw him in the distance, across the playground.

Dr. James lay in a puddle of gray snow-melt, his silk shirt completely soaked through. One arm was pinned beneath him, the other stretched towards the parking lot, his legs were tangled in water two inches deep. As Principal Freck approached one of the students pacing near the doctor's feet turned to her, "A building fell on him. It was old and they didn't take care of it so it fell over and squashed him'' The little girl affectionately grabbed the doctor's hand, tears running softly down her chin.

Principal Freck stared at the man before her. She thought about his expensive home, his fame, his impressive intellect. She thought about how the cold slush must feel as it seeped into his Italian leather shoes. She turned to take in the scene around her, that was so incomprehensible to everyone except those that were part of it.

From the schoolhouse, the sound of the bell rolled softly across the blacktop, as it did every day. She watched the children rise and walk towards the building. She turned to see Dr. James brushing gravel from the back of his shirt. He smiled gently at her as he walked past. As he left the playground she wondered what epiphany had struck him.

***

Kathleen heard later that Dr. James had abandoned psychology and bought a small artisanal cheese farm upstate. He and his wife had three children together and managed their business well enough that they employed four people year round. One morning a cow kicked him in the head while he was milking, knocking him unconscious for fifteen minutes. They treated him at the hospital for a severe concussion, he was lucky there was no fracture in his skull. He made a full recovery.

The children at Hawthorne eventually gave up the game. For their birthday one of the students was given a pack of cards for a collectible trading card game. Over the course of the next few weeks, most of the students were able to beg their parents to buy them their own cards to participate. After months of helpless despair, most parents gave in on the spot. The cards were five dollars for a pack of ten, most kids had at least a few hundred. The company that made them was later fined for the unsafe levels of chromium present in the ink the cards were printed with. Kathleen Freck worked at Hawthorne for six more years, until a car carrying four high schools seniors ran a red light and t-boned her on her way home from work. Everybody died.

~cA1Hc~ C~AHAM

A wintery breeze tickled their faces as they stood atop a shadowy hill, between their glittering city and the vast, star-freckled sky. She had spent so long watching the clouds and hoping for rain that she had forgotten what a clear night looked like. He bounced from foot to foot, swinging his arms wildly as he spoke. His words and movements were intoxicated with too much excitement and gin, making it seem like he was dancing in the silvery moonlight.

They had only been friends for a short time but she had already discovered what his sleepy face looked like at 4 in the morning, how purple made his hazel eyes stunningly vibrant and how they crinkled at the corners when he laughed. She had memorized the angles and bends of his nose and the patterns of freckles that peppered his cheeks. And she had seen the way that he effortlessly reassembled her broken pieces and silenced the turmoil inside her mind. It

had only been a moment but she was already certain that he was something she wanted to keep forever.

Here with him, on this spot above the sleepy city, the inky sky was cloudless and more beautiful than she had ever seen it. It was as if he breathed starlight into the winter air with every hiccupped laugh and awestruck sentence, scattering constellations across a clear dark canvas.

The twinkling of the city and the whisper of the breeze orchestrated a simple song that matched his sloppy waltz and she wondered if they were hearing the same melody. She was sure it sounded like a love song, full of sentimental verses and dramatic choruses, but she knew that their song would never be so mundane as romance and desire - no, their song would be something unique and grand.

His dance faltered slightly as he looked at her over his shoulder and grinned, spilling stars into the night. She had been lost and splintered, longing for rain, but his smile had cleared the clouds and filled the wintery, star-speckled sky with glittering galaxies.

ANNA-KO~~INc

ANG[lA fl[lD)

The feeling of the wind rushing under fingernails trying to force it back as a hand sails from car windows.

The flutter in the water as fingers would move through.

The sharp prick of the stray woody thorn of an oar.

Somehow it will cramp up and wake, tingle as if the sleep wasn't permanent. Reaching out surely it will grasp, but this grip is too much for me.

In one's head, they said, but a bullet to the chest or a fall from the sky jars no less in a dream or in life.

If only a whale to chase, my dear Captain Ahab, to take the focus off, This phantom pain may be the least to me; the grief may be the most.

lINN lUKc~

as blooms recede, the air no longer chokes us with inferno fingers. leaves decay, heat dissipates , summer's warm embrace will soon be nothing but a memory.

despondent winter creeps on careful feet it must be weeping season, I can tell. the pine trees lose their skin, revealing bones that shine a sickly pale against the moon. the snow glints unapologetically underneath.

TRONAUT

KcND~A NU11 All

1.

Nick sits in front of me and turns around, resting his elbows on my desk and perching his chin on his palms. "So, are you high right now?" He asks.

"No, but you are:' I say, looking into his red eyes. He doesn't hide it very well; I can always tell. He stalks off at the beginning of class every day to go smoke somewhere and comes back an hour later with a Snoop Dogg wincing on the toilet expression. I think he joined the newspaper staff just so he'd have an excuse to smoke during school - after all - no one reads the paper, therefore we don't actually have to work during class.

"You act stoned though:' Nick says. "You're always laughing at everything - stuff that's not even funnY:'

'Tm high off life:' It's not true. The truth is, I'm pretty fucking low most of the time.

2

It's senior year; Nick graduated and I quit newspaper. There's not much creative freedom when you're in a school full of rich, white, Mormon kids .

Today, I'm walking towards an abandoned running trail with Lucy and Kara. Lucy managed to procure some weed from a friend and somehow, she's talked me into trying it. I said I would do it, but I don't actually want to; there are too many risks. Okay, one risk. My parents; if they find out, they're going to kill me .

So I end up standing guard while Lucy and Kara fumble over figuring out how to roll a joint. I glance behind me after a while, and I see them laughing - I'm almost jealous . Why do I have to be so scared of what my parents think? They won't even find out. Nevertheless, I'm not trying weed today.

I'm dating a stoner, but he doesn't look or act like one (thank god). His name is Vincent and I think he's perfect. I don't really care what my parents think about me anymore. I'm in college and I'm an adult, it's about time I start trying to make myself happy.

I'm going to smoke pot today and I'm not going to freak out.

Vincent demonstrates what to do, gives me words of advice, I take a deep breath, and-

It's awful. The taste is disgusting . The burning is painful. The cough is agonizing.

And the weed itself doesn't do a damn thing .

Better luck next time?

4.

It's been a month since my last date with Mary Jane. I've been wanting to try again, because I really wanna know what is so fucking great about marijuana. Everyone I know acts like it's the greatest blessing upon the world - they practically worship it. They say it calms anxiety, that it's soothing, that it will help me. I guess I need help.

Vincent says that this time it'll work for sure. He tells me that a lot of people don't feel anything the first time. I'm not too hopeful, but I take a hit from the bong anyway.

I immediately begin to cough and I don't stop until it feels like my throat and lungs are going to fall right out of my body. There isn't enough water in the world to rid me of this pain.

"Do you feel anything?" Vincent asks .

And this time, besides my Sahara desert throat, I do feel something. And it doesn't feel good. Time is moving too quickly. We're watching Star Trek, and before I know it, it's over, and I can't even remember what happened. Vincent is explaining the rules of a board game, but they won't stick in my mind . We're playing it, and I keep glancing at the couch; all I want to do is lie down and fall asleep and wake up when this is over. 5.

I've gone another couple of months without smoking again. I'm starting to think that it's just not for me .

Vincent and his friend are in the kitchen, about to smoke. Vincent always offers me weed, and up to this point I've just been saying no, but for some reason, the presence of another person compels me to say yes. It's not that I actually want to smoke, but I just don't want to feel left out.

This time is worse than last time . Vincent has said before that in order to maximize the chance of having a positive experience, I need

to be as comfortable as possible; that means smoking with people I'm comfortable with. Vincent's friend is someone I am not comfortable with. Overwhelming social anxiety settles within moments of smoke entering my body. Anxiety is something I'm used to, but right now, it's intense. It's amplified and I can hardly handle it. I become aware of every movement I make, every word I say, and it all feels wrong. I'm being annoying, I'm being too quiet, I'm crossing my legs weirdly, I'm touching my hair too much. Everything. I. Do. Is. Wrong.

Vincent's friend leaves to get beer, and when it's just Vincent and me in the apartment, I want to tell him I feel trapped. I'm on the verge of an anxiety attack, and the only reason I haven't fallen apart is because I'm afraid of what Vincent will think of me. He's never seen me cry, and I'm not ready for him to. "How are you feeling?" He asks, and I just say, "okaY:' 6.

I really wish I liked pot. If there was ever a time I needed it, it's now. My dad has just been diagnosed with cancer, and I haven't stopped crying for twenty-four hours. I'm sitting in the car with Vincent, quietly sobbing, and he doesn't say anything, but he has one hand squeezing my shoulder while the other is on the steering wheel.

"I love you;' he says after a silent drive.

"I love you too:' I cry again and drown my sorrows in beer and making out.

7.

I watch Vincent light up, and I envy him.

Vincent is being evicted for smoking pot.

It was a beautiful apartment.

Oh well.

8.

Vincent's been living with his friend for a few weeks, searching for a new place to live. The place is a gross mess, but I can't complain about that. This is just a temporary situation, and at least Vincent keeps his own room clean. There is something I want to complain about though.

Ever since Vincent has moved in here, I've seen him smoking a lot more than usual. I've always considered myself 420 friendly, but I've also always been anti anything in excess. I'm starting to worry about him. Is he depressed? Does he even realize how much he's been smoking? Does he care?

I know smoking weed is safer than smoking tobacco, but I also know smoke of any kind is dangerous for the lungs. I can't help but think that Vincent is damaging his body, that he's putting himself at a greater risk

for lung cancer than he has before. I'm going to lose my dad to cancer, I don't want to lose my boyfriend too.

9.

Mary Jane is Vincent's other girlfriend . And right now, I think he loves her more than he loves me.

I'm worrying more than ever and I know I shouldn't. I'm overreacting. Even if Vincent gets lung cancer, it'll be decades from now, probably when we're both old and ready to die anyway. Besides, he's been smoking for years, damage has already been done whether I like it or not. And why am I not freaking about all the junk food and soda he consumes? That stuff is just as bad, and yet I'm not losing sleep over it.

But I can't stop worrying. I can't keep looking at the pipe sitting on the table or I'm going to fling it out the window. I can't keep sitting alone while Vincent and his friend get stoned . I can't keep pretending that I'm okay with this.

It may be that I'm afraid of the health hazards, but I know there's a part of me that's jealous . Part of me still wishes I liked weed. It's been a few months since the last time I tried it, maybe it's time to try again. One last time. Maybe.

10.

I'm at Vincent's mom's house . Did I mention she smokes weed and cigarettes? Anyway, Vincent is loading up her fancy bong, and I'm sitting on the couch like I usually do, when he asks me if I would like to smoke. He gave up offering weed to me a long time ago, after the near anxiety attack, so I didn't expect him to offer today.

"There's too much for just one person;' he says.

I've been wanting to try again, but I've also been wanting him to cut back. I hesitate, but finally decide that I may as well go for it. I've been feeling shitty lately, and this can't make me feel shittier, right? Except this time, I don't even get high, I fuck it up before smoke even hits me. A splash of water falls on the ground and I'm terribly embarrassed.

"You can try again;' Vincent says, but I just shake my head.

"It's okay, it's okay, I don't want to:' I feel extra shitty.

"You can try vaping;' Vincent says. "It's easier, you won't mess it up, I promise:'

Stupid me decides to give marijuana yet another chance . 11.

Vincent hands me the vaporizer, and once I've inhaled, I immediately notice how much better it feels than smoking. I'm not coughing up my lungs. It doesn't even taste that bad; it's actually clean. But

these positive aspects aren't enough to make up for the rush of anxiety that nearly makes me collapse .

I begin to cry - this is an anxiety attack -a full-blown - nearly unbearable - attack. Vincent holds me. "You don't have to keep trying:' he says. "If it makes you feel like this, don't do it again:'

12.

The anxiety attack was a few weeks ago. Since then, I haven't even thought about trying weed again. I don't ever want to feel those effects again. I honestly don't even want to look at the stuff.

Vincent's new roommate just brought home a plate of pot brownies. He holds one out to me and I don't contemplate taking it. "No thanks:'

"More for us then:' the roommate says, and I watch as he and Vincent take bites.

I disappear into my room alone.

Laughter floats down the hallway and no one hears me scream. 13.

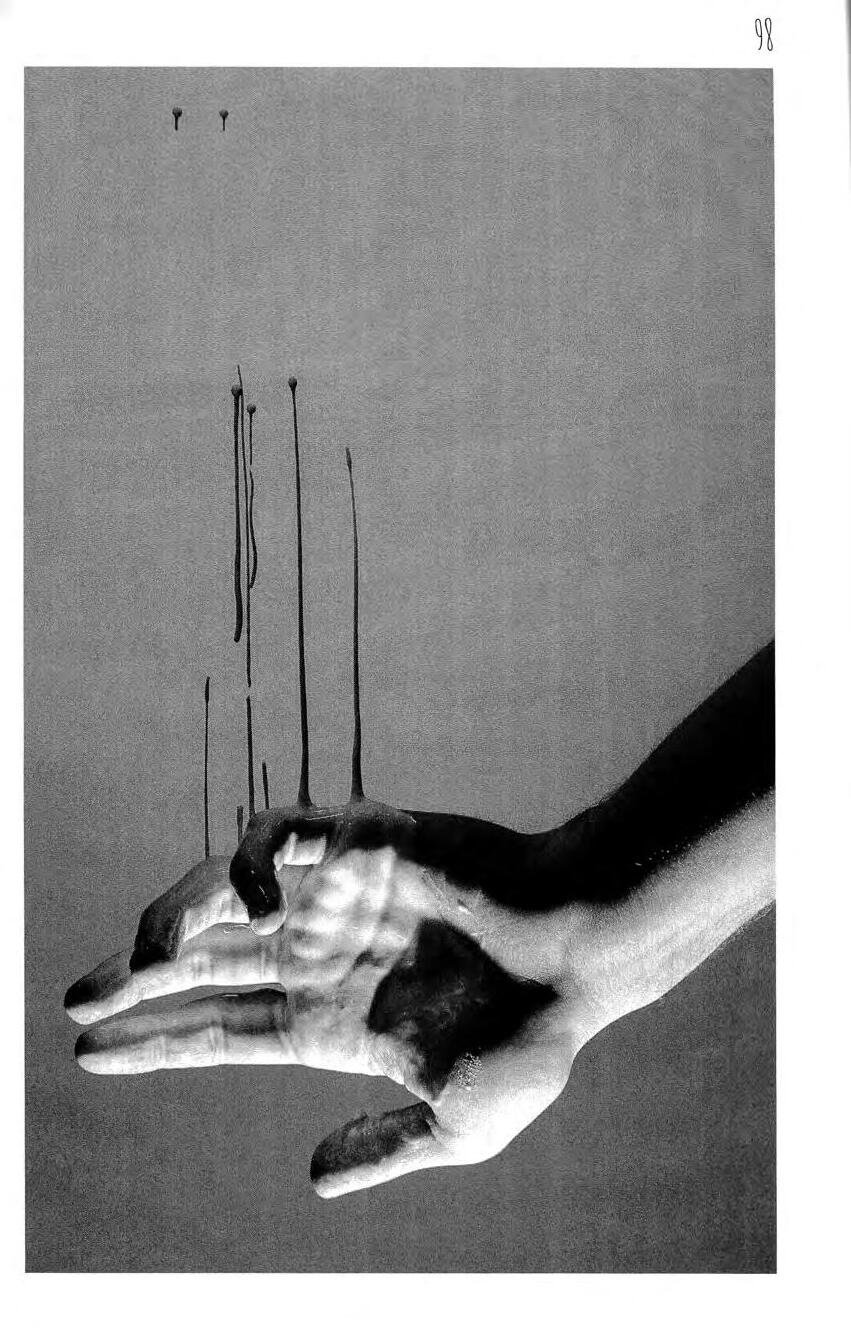

The floor is filled with the shattered remains of a glass pipe and traces of green and brown flakes. Plops of blood drip from my hands as I pick at the embedded shards in my skin. I hurriedly scrub the carpet, like a murderer erasing a crime. Within minutes, there is no evidence except my wounded hands.

When Vincent comes home, I tell him I tripped down the stairs.

"Where's my pipe?" He asks.

"I don't know:'

"Where's my weed?"

"I don't know:'

"Why are you lying?"

"I don't know:'

I don't know.

Canary yellow, exotic parrot green, tinges of toucan beak orange and purple plumage

Peppered throughout with peacock blue that no amount oflight diminishes

The beautiful black-eye bruise rainbow

Uncaged, free lies fly from my mouth as I weakly warble it was an accident

My flock gawks at the clumsiness mottled across my face in such gorgeous hues

They gracefully perch on my precarious tale, at rapt attention

Longing to sing them the truth, extend the branch of honesty to garner me peace

Instead this doting dove, daddy's daughter doesn't speak true

Falcon father fuels her falsehoods forward

His little 'love' lacks luster but lacks less than absolute loneliness

Staying silent, songbird suffers while the gaggle ogle's

From egg hatching to casket latching, this nestling never tells of her hit catching

I vomit blood-soaked stones.

That writer--so nurturing--

I ate her children.

Such soft, somber things!

Free and fresh and fleshy.

But she fooled me: while I dreamt

She sliced my stomach

And sewed in stones.

I noticed no weight (til waking.

Do I still want those kids?

They sound too sweet for me.

But then, my core is already ruined.

I crawl to the well Clumsy, trembling, blood-stained--my own--

I'll never run .again, I realize, But I'm more afraid to hold still.

Hell-bound heavy--

The weighty wolf, stone-starved.

My reflection--she howls laughter, Wolf in sheep's clothing, that prophet:

"Pound your paws with flour, Thrash your throat with honey, Live your lies and swallow What purity will let you near; But you will rest, and you will wake, And find yourself

Still a monster. Always a monster:'

My belly grates--my flesh is too yielding-But flesh was always my weakness. There's the vomit again.

I look down a deep, dismal well:

No source of light, but I'm thirsty

From choking back my own blood.

I lean close to drink

I fall in, And I'm drowning. I drown.

ANNA-KO~~INc ~AN(O(K

}OHN-[HA~lc) [Ol 10N KcUNc

With tears, I'll tell you this, my dearest friend, Should day or night at last come for us all, I shall hold your hand true until the end.

Through words and temper, our mights did contend, As fire does tempest blade in calm and squall, With tears, I'll tell you this, my dearest friend.

Grins and trust in dawn's day to each we lend, With each adventure, whether rise or fall, I shall hold your hand true until the end

Defiant and glad, no need to pretend.

If love be the one word you can recall, With tears, I'll tell you this, my dearest friend.

Our fearful hands, though mad eyes, did extend, In rapid descent, we flew to death's thrall.

I shall hold your hand true until the end

Solemnity dare not need tempt to mend, Grief and pain the least burden of our pall.

With tears, I'll tell you this, my dearest friend, I shall hold your hand true until the end.

RDEAL

I UIDATE }c))l(A

DOWNING

You pick away without realizing With every new fracture you create, a delicate piece descends, dissolving flaws and qualities alike; reduced to a simple puddle.

bird's nest on her head, teeth trapped behind prison bars, and eyes encased in glass; she smiles right now (but just wait until they take her) she'll need therapy when it's over.

cruelty is common for the whales at Sea World and the guppy girl.

KY 'FULL OF INE

~WARD

~AL OVE DAVID ~ANc)

A while ago I was dumped (I'm referring to the first time.) During the long recovery, I learned a thing: The abiding salvation in efforts to survive is the faith a person places in oneself. Simply put: you will keep going for as long as you believe that you can, and eventually, you ' ll catch a break.

Or die

(I always forget about the dying .)

So, when that wonderfully normal creature, with the green eyes and curly hair, ripped the cardiac tissue from my thoracic cavity, what was I to do?

The first thing that came to mind was meatloaf, so I got some. I ate it while lying in the fetal position , listening to the emotionally crippling Half Alive, written and performed by Secondhand Serenade, weeping emphatically between bites.

It became a ritual. I would take two or three bits of meat, cover them in cocktail sauce , then swallow them whole. I would let out two or three deep sobs, crying like the world had died, thinking of my dear true love

It was all so romantic.

I lay centered on the living room floor of my first apartment. I did so with the lights off for effect or because I had never bothered buying a lamp and there were no light fixtures in the room. The older versions of me would never rent an apartment without lights in the living room. It's just too impractical. The me of today probably wouldn't have eaten the cocktail sauce either. Deep in my soul, I've always been a ketchup man, yet on that day I was simply a confused young person going through a bad breakup. And that meatloaf? Store bought and red as the Chinese flag. Now, when my world comes crashing down and it's time to eat my feelings, I stick to carbohydrates; mashed potatoes or pumpkin pie , french fries or goddamn American beer. But I was young then, and dumb too . You have to forgive yourself.

My second great dumping came at the hands of a lovely, petite young woman. For that tragedy, I chose a Wendy's ¾ pounder and Adele's Someone

like you. I ate and cried in turns. And sure, I drank the bottle of vanilla flavored vodka from the freezer. And sure, I vomited up the hamburger and the vodka onto some sidewalk outside of some bar. It was all so tragic, and romantic too.

As I lie there on cold concrete, turning over to throw up in the grass, no one checked on me. This is my favorite detail from that night; I spent the time it took to empty my stomach ten feet from the front door of the bar and no one stopped. The public had simply decided to let me die in peace.

And if I had?

In those moments, the tragic kind, I wanted my scars to last forever. I would seriously describe myself as the ghost of us, to whoever bothered listening. I considered tattooing the initials of my one true love across some piece of skin, under the header "real love lasts forever:' Some older person would talk me out of it, failing to see the romance. Older people never saw the romance.

Could no one understand that the world had cracked and the good in me had died?

My friends were no better than the old They built their lives on purpose and according to plan while I suffered. I was dying in battle with the gods of love and death while some I knew wasted time on things like Algebra and summer internships. Nothing is less romantic than Algebra; nothing more on purpose than a summer internship.

Now, I measure the effectiveness of music on its usefulness during a breakup. I consider which piece of meat blends nicely with the sad pop songs of the day. I suppose Kate Nash's nicest thing was written to accompany the self destructive act of eating a Four-by-Four from In-and-Out, served Animal Style.

And yet I've grown, if not up, then at least upish . I expand my awareness of what a break-up ritual ought to be . Lamb sliders to the theme of Paint it Black by the Rolling Stones, an ostrich burger, slathered in thousand island sauce, consumed to the tunes of Back to Black by Amy Winehouse, or, because why not, a Big Mac eaten in complete darkness while Self Esteem by The Offspring pulls the tears from my skull.

Now that's romance.

That's real love.

'RBORO

Our grandparents and their grandparents said that if you walked deep enough into the forest, it was a dreaming , shifting place. They said there was a beast there, the one who devoured our dead. They said it would someday eat up the town, the smog, and the sun. And then, the world would again belong to the beasts. It was a natural cycle, they said, of day and night, oflife and death.

Our town had a cemetery like every other town. Some gravestones were small and some were large. Some were simple flat rocks in the earth and some towered up to the sky. But they all had one thing in common. If you dug up the graves and opened the coffins, they'd all be empty.

As the air drew cooler it settled down with the fog. I could feel it sink into my lungs, and I took another drag of my last cigarette. The bench was cold and the cigarette was dying. I sighed.

The streetlights in the outskirts of town were flickering, dim, a few tired ones burned out. I walked past the house. I walked past it again. My lung s hurt for another cigarette and I reached into my bag, but my fingers grasped nothing but empty gum wrappers. I stood with my shadow on the front porch, the heavy wooden door in front of me.

My heart pounded like my fist against the door.

The young man in the doorway stared for a second . "Your shoes are untied;' he said softly. His voice was deeper than I remembered. fast:' I looked down at my shoes. Both were perfectly tied.

"Made you look;' he said, smiling.

"Yo u bastard!" I laughed and hugged him, hard. "Yo u grew up way too

He pulled away and shrugged. "You were gone awhile:'

I couldn't argue with that, so I shrugged back.

"Come in, Holli'

Devon led me down the hallway into Morn's bedroom . Except it was

no longer a bedroom.

It smelled of antiseptic, of medicine and tubes and plastic plants. It smelled like someone covered the dusty scents of death with flower petals and hand sanitizer. This was not a bedroom, I realized. It was a dying room.

My mother's eyes were closed as if she was asleep. But it wasn't peaceful. Her limp body gasped every inhale like the breathing was torture and the tubes made her do it.

It seemed like a stupid question "Uhh - is Is she going to wake up?" Devon didn't answer. "Mom;' he said quietly. "Holly's here. Your daughter is here:'

Nothing happened.

The woman I grew up with . The woman who raised me. The only woman I loved and kissed and hit and hated. She was dying in her bed and although we were there, she was alone. I tried to find some words, any words, to comfort Devon, to comfort myself. But all I knew was that she was dying and we were all dying and everything else was dying, too.

I stood there in the doorway for a moment, suspended and weak. Devon stood next to her bed, waiting for me to follow. I took a step forward.

"Do you want to hold her hand?" he asked.

I moved slowly to the bed. I placed her small, pale hand in mine. I watched her face and so did Devon. And we said nothing, as we watched our mother, dying .

I didn't really sleep that first night. In my old room in my old bed in my old life, I sweated and I listened to my nervous beating heart.

Now that I was here, all I could remember were the things I didn't want to. When I was a teenager, I stayed out and drank all night and listened to angry music. I staggered home in the early hours of the morning to screaming matches with my mother. She would pull me by my hair and lock me in the closet with our Bible and a flashlight. I hated the way the book smelled, like rust and rot and death. I hated the way it felt in my hands; leathery and thick, like snakeskin. I hated the suffocating words on the pages. They said that you cannot choose where you are from and you cannot choose where you go when you die. Not to heaven, not to hell. Not in the ground, but somewhere else.

I spent hours burying my anger in its thick, dry pages. And when I was seventeen, I took that Bible and I burned it up in the driveway.

I have never before or since tasted so much blood in my mouth.

I packed up everything I could into a blue backpack and bought a bus ticket to northwest nowhere, to mystical Aunt Kara, whom I'd never met and barely heard of.

Somehow, I found her and I didn't bother looking back. For a while. ***

The dying bed was busy. Liquids went in with tubes, and it came back out with tubes. Breath came in with shallow, desperate gasps. Death is supposed to be smelly, messy, gruesome. But on the dying bed, it was schedules and antiseptic wipes. Morning meds. Afternoon meds. Evening meds . 50mg dose of this, 400mg dose of that. Look at the charts if you get confused. Don't forget to wipe. Don't forget to clean.

Sometimes her eyes blinked open, shining and weary. But by the time a few of my heartbeats had tripped over the others, her eyelids fluttered closed. I tried to tell her I was sorry that I couldn't be the daughter she wanted me to be. I tried to tell her that I wished we could have gotten along better, because she wasn't always so bad . I told her I remembered the orange kitten she'd brought home on my ninth birthday, the one who waited for me back in my apartment a hundred miles from here.

"I don't know if you remember. You taught me how to take care of her, how much food to give her and how to clean up after her. You said that a cat might not love you as much as you love it, or the way that you wanted it to. But it would give you all the love it was capable of;' I said. "Right, Mom?"

She just kept gasping.

Devon went to school. I watched Mom. A few times a week, the hospice nurses watched her and I wandered my old town.

The town was plagued by its admiration and hatred of its traditions. Women adorned their fingers with snakes, their own tails in their jaws. Men mounted plaques of them on their walls. Adolescents cut off the heads of garter snakes and left them at our door, a constant reminder of what was to come .

The streets of the town were cracked and warped at the sides. Those without families wandered the southern ends of the streets at night, wondering who would take them home when it came their turn to die.

I sat on the bench at the park, staring at the sky and smoking cigarette after cigarette . I waited for my mother to die.

One afternoon, Devon came to sit next to me.

"Hey, Holly;' he said.

"Oh, hey, Devon;' I said.

"What's up?"

"Oh, nothing. I'm just sitting around, polluting my lungs:'

"I thought you were a singer;' he said.

I looked at him, half-smiling. "So?"

"Well, you know. You want your vocal cords to last, don't you?"

"Nah. I'm a vocalist for a punk band. You don't need to sing well, it's mostly about the words and the aggression anyway. You just need to make

sounds, like with your throat:'

"I guess you're right:'

"Uh-huh, you got it;' I said, blowing smoke.

He paused for a moment. "It's good to see you back, HollY:'

"Sure:'

We were silent for a moment, and I was okay with that. I thought about how when we were kids, we were always chasing each other, running in circles and fighting and laughing and crying and doing it all again. she .. :'

"Listen , HollY: ' he said . "You know what we need to do after - after

''After she dies :' I stabbed out my cigarette.

"Yeah:'

"Yeah, I know;' I said.

He was talking about the pilgrimage . The way people dispose of the dead in this town.

"There's no getting out of it , is there?" I said Devon shook his head . "But don't most traditions eventually die?"

"I think so;' I said . "But the people in this town believe that when this one dies, the beast will devour us all:' ***

When it happened, it was quiet. Anticlimactic. Her vitals descended slowly through the weekend and plummeted on Monday night. As her only living relatives, Devon and I decided to take her off of life support the following Tuesday. With the hospice nurses, we watched her take her final breaths.

I felt her exhales escaping into the atmosphere, and I tried to hold them somewhere deep inside me . They would last longer if I could hold them , if I could just hold them in my hands. But they slipped through my fingers and they whispered into the air.

And then, they were gone .

We carried her in a neat little box. I held it at the front and Devon at the back. We hiked into the mountains , walking along the same dirt trail that our ancestors had traveled upon for millennia. We were taking our mother to the beast.

We walked across the pine needles and heard the things that whispered behind the trees . We walked far into the dreaming, shifting part of the forest that our grandparents had told us about. We walked through curtains of fog, blankets of snow, and waves of darkness .

We walked deep into the belly of the forest; the trees thick and green. Devon and I finally stopped at the end of the trail , at the mouth of an enormous cave. We set the neat box down and took our mother's body to the

front of the cave's mouth. We heard the sounds of bending metal and scraping rock.

"Should we wait? Or should we just leave?"

"Let's wait a second. I want to see . .." Devon said.

I paused . "OkaY:'

"I've been expecting this for a while . But it wasn't how I expected:' he

said.

I nodded. I was exhausted and my body had nearly reached its limit.

My tired mouth opened and said, "She hated me:'

Devon looked at me harshly. "She didn't hate you:'

I was quiet. I looked at my brother and I thought of his blood, my blood, our mother's blood, in our veins. I thought about her anger and her confusion. I thought about the kitten she had given me on my ninth birthday and what she had said: that it might not love you in the way that you hoped it would, but it would love you with whatever it was capable of giving.

We heard more scraping from the cave. A million tiny snakes began to slither from its mouth, each no larger than the length of my hand . They started to surround my mother's body, all working together to pick her up and bring her corpse inside.

I stared into the darkness of the cave as they took her away and in a sliver of light I saw the beast. It was impossibly huge, its face with metal jaws and steel eyes staring upward at nothing . The snake had its gigantic jaws fixed on its tail, eternally spinning no faster than the speed of the earth itself.

The snake would keep spinning and the cycle would continue. The day would bring night. The light would bring shadows. And because they were born, all things would die.

HIJAH Wt)\

I am here, and here, and here. I am shadows imprinted on asbestos walls and old lace. I have died in this room in the ribcage of acrid men, writhing among their proscenium cavities, paying broken final mirth to their wicked hips that tower and loop back as both broken bone and birth. I hear desperate songs of dripping sorrow, my feet grow into stones, and I am left counting drops of marrow until I am counted by and becoming bone. This is not my home.

I am a raven plucked crimson clean. My wingbeats splatter alabaster walls with iron falls, until bleeding ivory sings, until my bleating caws sink in seas of blood and marrow, and I am pinned by leaden wings. Here amongst this graveyard, I am clean.

Tired fingertips turn to chalk and soon I am a column of bone, dripping, drop, by drop. Each piercing plop singing, home. Horne, please take me home.

Please, I am so scared to always be. Let me become.

DANNY l. ~U1Hc~flclD Ill

Semantic satiation: a scientific term for something we've likely all experienced. When a word loses its meaning, and the meaning loses its word, and repetition kills our understanding of the word. "Insanity, insanity, insanity, insanity, i-n-s-a-n-i-t-Y: ' Repeating this word again and again and over again in your head or out loud, does it start to lose its meaning? Of course, it does . Ironically, many will define ' insanity' as doing the same thing over and over and over once again, expecting different results.

This phenomenon was first mentioned & described scientifically in The American Journal of Psychology by Elizabeth Severance and Margaret Floy Washburn in 1907. "If a printed word is looked at steadily for some little time, it will be found to take on a curiously strange and foreign aspect. This loss of familiarity in its appearance sometimes makes it look like a word in another language, sometimes proceeds further until the word is a mere collection of letters , and occasionally reaches the extreme where the letters themselves look like meaningless marks on the paper: '

Opening up my eyes to cold sweat , I know exactly what's wrong . Night after night after night I've wrestled with the little pink grown-up treats next to the alarm clock on my nightstand My bed seems damp. I'm sweating more than I initially thought. The plates and screws in my lower back seem to be stabbing the interior of my skin, waiting to pierce the flesh. I feel heavy, as if I've been injected with liquid metal in every main artery. I'm mustering strength to get out of bed and walk to the bathroom, but the urge to swallow a pill is stronger Looking in the mirror, I don't recognize myself. Sunken eyes and chapped lips and pale skin, I see a ghost in the mirror, a fucking monster. This image combined with an instinctual and festering need for the drug is making me sick to my stomach .