Coda

She Said: Womanhood in Utah 2 0 2 5

She Said: Womanhood in Utah 2 0 2 5

She Said: Womanhood in Utah - Coda is published by the SLCC Community Writing Center

All inquiries should be directed to:

SLCC Community Writing Center

210 East 400 South, Suite 8 Salt Lake City, UT 84111

Salt Lake Community College (SLCC) and the SLCC Community Writing Center (CWC) are not responsible for the opinions expressed in She Said: Womanhood in UtahCoda, nor do the creative works represent any official position of these organizations. Individual authors are solely responsible for the opinions expressed herein.

Each author retains copyright individually. Reprinting of this publication is permitted only with prior consultation and approval from the SLCC Community Writing Center.

This edition of She Said, Womanhood in Utah was compiled and edited by Kati Lewis, Mia Manfredi, and Francis Cobbe.

She Said: Womanhood in Utah - Coda ©2025

She Said is a series of workshops hosted by the SLCC Community Writing Center (CWC) in collaboration with Amplify Utah.

The She Said workshop series and anthology publication exploring womanhood in Utah and some of the issues affecting the life of women, especially reproductive health and rights, invisible labor, representation in the media we consume, and much more.

The CWC and Amplify Utah are sincerely grateful to each of the women and genderqueer folks who have participated in the workshop series since fall 2022, submitted their art and writing for publication, and who continue to share their voices and experiences with us.

The CWC is sad to announce that this will be our last She Said Anthology. As Salt Lake Community College has made the decision to close our doors come June 2026.

In music, a “coda” (Italian for “tail”) is known as the concluding passage that brings a musical piece (usually a dance) to an end.

Coda marks the final passage. A closing movement, a final gesture. It is not just an ending, but a moment of stillness and reflection.

As this collection symbolizes a close to the She Said community anthologies from the Community Writing Center, we have decided to title this final work ‘Coda’.

The dance we’ve created, through shared truths, has been nothing short of transformative. Thank you to everyone who shared their experiences of womanhood in Utah. Together, we have curated this final collection.

Though this marks a tentative end, this work has become an important part of the CWC’s closing chapter, and we believe its imprint will last.

The community born from these pages will continue to move, echo, and dance, even after the music fades.

Jess Challis

“I laid this suitcase on my chest / So I could feel somebody’s weight” — Brandi Carlile

I learn your heartbeat is dangerously fast by lying on your naked chest, ear pressed tight to your sternum, rising then falling in rhythm—

It’s a condition, you say— my breathing slows and I inhale when you sigh, steal your last awake breath of the day—

I had a hummingbird feeder outside my living room window

when the sun was getting low and my eyes heavy,

I would sit by the window,

watch a tiny green body the size of my thumb flit, dip, pause, sip, oversized heart drumming, suspended in liminality— my Uber home from the hospital today

when I was a girl, a plastic tube of thick sugar water, mundanity disguised with ten drops of red food coloring—

passed a brick building with fat letters in matte black that read—

I love you / say it back

Aubrey Earle

“I quietly rage within the silence, where you left me cold and bare, Abandoned by the wayside, in the shadow of your stare. You watched as I retreated, shamed by who I am, While you basked in fleeting joy, I pondered what I might have done.

You cast me off like trash, worthless in your eyes, Lured me with false friendship, beneath deceitful skies. With open heart I sought you, arms wide with hope unfurled, But you led me to your hollow, your cult-like, vacant world.

You whispered care and kindness, then vanished like the night, Your absence left me wounded, your betrayal seared so bright. No closure to the chapter, no solace for my ache, Just remnants of a friendship that was nothing but a fake.

I’m hurt by how you played me, with charm that turned to dust, Innocence now shattered, left only with mistrust. I deserved a better ending and not this cruel, unjust charade, For in the ruins of our bond, a deeper pain was made.”

There are betrayals that feel like a slap, loud and immediate and undeniable. And then there are betrayals that arrive in whispers... slow, delicate dissolutions that leave no visible scar, only a pervasive emptiness. This is the story of the latter: of the soft erasure performed by a girl named Lilly, but truly performed by many girls like her... especially within the invisible, unspoken social structures that saturate Utah’s dominant culture. I was seventeen when she became my friend. Or rather, when she played the part of one. And I, starved for connection as a foster girl in her 3rd of 7 homes... and gladly accepted the illusion of her friendship.

Lilly was sunshine on the outside and I admired her greatly for it. She smiled when adults watched, wrapped her words in cotton candy, and

performed a kindness that, at the time, I mistook for sincerity. It was only later, much later, that I would realize she had not extended her hand out of empathy or mutuality... but out of expectation. I was never a person to her. I was a project. A number. A numerical project of a soul to save.

I was raised in a religious environment... non-denominational... but with wavering conviction. My family was fractured, I was in foster care up for adoption and investigating the Mormon church at 17, lonely in high school... my mind was tumultuous with the symptoms of a disorder I couldn’t yet name. When Lily approached me in the hallways of our ward building one day, shiny straight hair and composed...unshakably confident... I felt something akin to hope. She saw me. Or so I thought.

She invited me to church and church activities. Young women events. Temple trips where I sat in the lobby til I was actually baptized. At first, I was flattered. Grateful. I assumed she wanted me there because she liked me, because something in me resonated with her. It wasn’t until I overheard her referring to me as “her baptism,” just once, and gave me an annoyed look during girls camp when I hugged her for a photo, that the cracks began to show. Not her friend. Not even her peer. Her baptism. An achievement. A milestone. A box checked. A number. Barely a person she can stand.

The world Lilly invited me into was both enchanting and suffocating. It gleamed with pearly smiles and beautifully braided hair, perfectly hemmed skirts, well manicured nails, fresh clean scents and carefully measured speech. It all preached modesty and virtue, grace and sisterhood... but beneath its surface lurked something colder... a silent but merciless code. You belonged if you conformed. You were welcome if you performed and looked the part. And love was conditional, always, upon your willingness to disappear into the mold.

I didn’t fit the mold. I never could. I was too sad, too intense, my brain not so nearly developed. I wanted to talk about grief, about God in ways that didn’t always match scripture. I asked questions. I made art that unsettled people. And most importantly, I needed something real...

connection that wasn’t tethered to whether or not I prayed correctly or looked “appropriate.”

Lilly began to pull away once she realized I wasn’t going to become the poster child for repentance. She stopped texting. She ignored me in public. Her smile dimmed in private moments, replaced by a subtle disdain I can still see if I close my eyes. It wasn’t rage. It wasn’t cruelty. It was worse... indifference. I had been stripped of my usefulness, so I was discarded.

This wasn’t just about one girl. It rarely is. Lily was a mirror of the broader culture that raised her. In Utah, where the air is thick with both breathtaking beauty and the suffocating pressure to perform holiness, the roles for women are often predefined. Be sweet. Be quiet.Be busy. Be beautiful. Be useful. And above all... belong, or pretend to.

If you don’t belong, and you don’t pretend well enough, you’re tolerated for a while. Pitied. Prayed over. Lovingly prodded back into the fold. But if you keep diverging, if your sadness doesn’t subside, if your mind remains in pain, if your authenticity threatens the façade... eventually, you become invisible.

This is what happened to me. And not just with Lilly. Again and again, I have encountered women in this state who smile but do not see me. Who speak kindly but never call. Who perform closeness without offering it. The wound they leave is not loud or dramatic... it’s a quiet ache. The ache of not being enough. The ache of watching others laugh without you. Of seeing yourself reflected in none of them. Of knowing that your openness is seen as a flaw, and your depth as a liability.

For a long time, I thought this was my fault. I told myself I was too much. Too fragile. Too dramatic. But as I’ve grown, and as I’ve healed... somewhat... I’ve come to understand that the culture itself cultivates this dynamic. Within the specific framework of Utah Mormon womanhood, image is often valued over authenticity. Connection is conditional. Smiles are currency. Vulnerability, unless repackaged as a faith-promoting story with a clean ending, is dangerous.

But life is not clean. Friendships don’t always end with closure. Betrayals don’t always explain themselves. Some hurts linger in the silences. Some wounds fester in absence. And some poems, like the one I wrote, are born from the residue of people who claimed to care but never really did.

“You cast me off like trash, worthless in your eyes, Lured me with false friendship, beneath deceitful skies...”

There’s a cruelty in manipulation masquerading as salvation. In being told that your soul matters, only to find that your humanity does not. I was brought into a circle under the guise of compassion. But it was never about knowing me. It was about fixing me. Saving me. Claiming me. And when I failed to transform into the ideal, I was dropped.

For years I’ve carried the question... What did I do wrong? And the truth is... nothing. I was merely honest. Raw. Messy. I needed what so few people in that culture were willing to offer... unconditional presence. The kind that doesn’t require conformity to exist.

Writing this now, I grieve not just the friendship I lost but the hope I once had in friendships like it. I grieve the girl I was... the one who believed that kindness was always sincere, that friendship meant permanence, that faith communities were safe. I mourn the innocence that Lilly’s departure shattered. And I mourn how many other women I know who have felt the same.

Because Lilly isn’t one girl. She’s a type. She exists in the Relief Society president who won’t sit with the sister who wears too much eyeliner and her bra peaks through her top. In the young women’s leader who praises thinness in every testimony. In the ward member who whispers judgments behind a smile. In the culture that teaches women to perform grace but not practice it.

Still, I do not write this to condemn every woman in the church, nor to pretend that the pain I experienced is universal or irredeemable. There are extraordinary women in Utah, in Mormonism, in the world...

women who break the mold, who offer real friendship, who sit in the mess with you and do not flinch. But they are not always easy to find. And they are often just as wounded by the system as those they try to love.

I write this essay to name the wound. To give language to a betrayal that so many people like me experience and yet are told they must not speak about. Because it’s not “Christlike” to call it what it is. Because it might “hurt feelings.” But silence protects no one. And truth is not cruelty when it is spoken to heal.

My poem, Lilly Of The Field And The Ugly Duckling, began as a scream I couldn’t say out loud. A cry for all the times I was overlooked, patronized, invited in and then quietly excluded. It was a way to claw at the wall of invisibility. To insist that what happened mattered. That I mattered.

“I’m hurt by how you played me, with charm that turned to dust, Innocence now shattered, left only with mistrust...”

In the years since Lilly’s exit, I have worked hard to rebuild trust... not just in others, but in myself. To believe that I am worthy of genuine friendship. That my sensitivity is not a flaw. That my intensity is not too much. That I can write things like this and still belong somewhere.

And maybe that’s the miracle of writing... It gives you a voice where you were once silenced. It turns the ache into articulation. It transforms isolation into shared language. Maybe someone will read this who has also been dropped without explanation. Who has also wandered the clean halls of churches and felt unspeakably dirty. Who has also mistaken performance for love.

If that person is you, know this... You are not alone. The problem is not your need. It’s the culture that taught people to fear it. You deserve friends who see you. Who stay. Who want more than your story wrapped in the bow of redemption. Who can handle your sadness without trying to fix it.

You deserve women who know how to weep without hiding their mascara. Who sit with you on the bathroom floor when the world is too heavy. Who text back. Who show up. Who don’t just say your name... they mean it.

The pain Lilly left behind has shaped me, yes. But it has also refined me. I now recognize the difference between kindness and performance. Between inclusion and tolerance. Between being loved and being used.

I write this to offer something real. Not a sanitized, easy answer. But a witness. A reckoning. A reach across the page.

If the “She Said” anthology exists to gather stories of what it means to live as a woman in Utah, this is mine... I have learned that the worst betrayals are not always violent or loud. They are quiet acts of abandonment in spaces that preach inclusion. They are smiles without sincerity. Invitations without intimacy. Faith without love.

And I have learned to say no to that kind of faith. To seek something truer. To create the kind of community I was denied. To be the friend I once needed.

So if you’re reading this, and you’ve ever felt like an outsider in a room full of sisters, let me say what Lilly never did... I see you. You’re not a project. You’re not a number. You don’t have to perform to be loved. You’re already enough.

And still, even after all these years and all these words, I sometimes find myself searching for her face in crowds. Not just Lilly’s... though hers is etched somewhere permanent in the depths of my overthinking mind... but the face of every woman who ever offered me something she didn’t intend to keep. There is a ghostliness to that kind of memory. It lingers not as a sharp pain but as a dull echo. A familiar hush that returns whenever I feel on the outskirts of belonging.

You learn to live with these ghosts. You learn to eat around them, speak

over them, dress in ways they might have approved of once, even when you know better. And then you learn... if you’re lucky, if you fight... to stop seeking their approval altogether.

Because healing, as I’ve come to know it, is not about forgetting the injury or making peace with what happened too soon. Healing is about understanding it. Giving it language. Letting it live outside of your body for long enough that you can recognize it when it tries to return. Sometimes healing looks like writing a poem. Sometimes it looks like not texting back. Sometimes it looks like leaving the church that baptized you but never held you. Sometimes it’s returning to that church and standing proudly as you are. And sometimes... it looks like standing at a party full of women who all seem to know each other, who all have matching nails and perfect laughter, and choosing not to shrink when they glance past you.

Because you’ve come to realize that you are not invisible. You were just unseen.

And there’s a difference.

I used to think that survival was about changing myself to be less abrasive. Less raw. Less in need. Less “too much.” But I no longer wish to be less. I want to be more. More honest. More complex. More textured and contradictory and vivid. I want to live in full color, even if it makes some people turn away. Even if it reminds them of their own shadows.

Because here’s what they don’t tell you when they praise the quiet girls, the modest girls, the agreeable girls... there is no glory in being palatable if it costs you your voice. There is no virtue in invisibility. And there is no sainthood in swallowing your own ache just to make someone else comfortable.

What I learned from Lilly... eventually very painfully... is that I would rather be lonely and real than loved for a lie.

And it took a long time to say that out loud. I used to pray to be lovable.

I used to cry into my pillow asking God to make me easier to care for, easier to hold, easier to carry. I thought maybe if I could just look more like them... laugh at the right times, wear the right clothes, cry only in testimony meeting and never too much... then I’d finally be enough.

But I no longer want to be easy to love. I want to be loved rightly.

I want friendships that are spacious, that have room for silences and breakdowns and dark nights that don’t resolve neatly by the end of the story. I want women in my life who are brave enough to look me in the eye when I am grieving and not try to smooth it over with a platitude. I want people who stay when it’s inconvenient. Who ask how you are and mean it. Who don’t need you to wrap your pain in scripture to validate its existence.

I want the kind of women who recognize that compassion isn’t a goal... it’s a practice. A messy, inconsistent, holy practice.

And I am slowly becoming that woman for myself.

There are days I still doubt it. Days when I walk into Relief Society... or into any room where women are expected to smile and sit still... and I feel like the odd one out again. I feel the weight of all the times I wasn’t chosen, wasn’t invited, wasn’t seen. But then I remember that I am building something new. A life that does not depend on being chosen to matter.

I am not anyone’s baptism anymore. I am not a soul to be rescued. I am not an emotional errand, a pity project, or an inspirational footnote in someone else’s journal entry.

I am a person. I am a woman. I am a friend.

And even if I walk into every room alone for the rest of my life, I will not disappear again to make someone else feel comfortable.

There is a strange sort of peace in accepting that some people will never

come back to apologize. That some friendships will remain unresolved. That closure, in many cases, is something you build for yourself when the other person won’t give it. I waited for years for Lilly to say she was sorry. For a message. A call. Anything. But it never came. And now I know it never will.

And still... I forgive her.

Not because she asked for it. Not because she deserves it. But because I no longer want to be tethered to the pain she left behind. Because I don’t want to carry her silence with me forever. Because forgiveness, when it is real, is not about excusing what happened. It’s about refusing to be defined by it.

Forgiveness is not the same as reconciliation. It’s not pretending we were ever truly close. It’s not minimizing the wound. It’s simply this... letting go of the hope for a better past.

And in its place, choosing a better future.

One where I am whole. One where I surround myself with people who don’t flinch at my honesty. One where I don’t have to shrink to be accepted. One where I become the woman I once needed when I was seventeen and aching.

Because that girl still lives in me. She still walks the halls of that ward building. She still stands too long near the corner of the room at youth dances. She still waits for someone to say, “Come sit with us.” And I want to be the voice that answers her now.

You don’t have to become what they wanted you to be.

You don’t have to be the quiet one. Or the grateful one. Or the girl who always smiles even when her heart is breaking.

You are allowed to take up space.

You are allowed to be sad.

You are allowed to need more than what they’re offering.

And most importantly... you are allowed to start over.

Because the truth is, for every Lilly who disappears, there are women out there who stay. Maybe not many. Maybe not right away. But they exist. They’re the ones who find you crying in your car and sit with you without trying to make it better. The ones who laugh loud, love deeply, and aren’t afraid of the mess. The ones who say, “I see you,” and mean it.

And maybe you have to become one of those women first.

Maybe you have to build the table before anyone sits down with you at it.

But it’s worth it. God, it’s worth it.

Because there’s nothing lonelier than trying to make yourself small enough to fit into spaces that were never meant to hold the real you. And there is nothing more holy than refusing to do it anymore.

So I’ll end this... not with a final word, because grief is never final... but with an invitation... If you’ve been hurt like I was, come sit beside me. If you’ve been discarded, excluded, reshaped to fit a mold that crushed you, come closer. If you’ve been told you were too much, let me be the one to say you’re just enough.

You don’t have to pretend anymore.

You don’t have to smile if you don’t want to.

You don’t have to wrap your truth in doctrine to make it digestible.

Your grief is sacred. Your story is valid. Your voice is a miracle.

And though I may or may not walk the temple halls again, I’ve found something holier than all the polished sermons and white stone in the world...

A friend who stays. A voice that dares. A woman who writes, even when it hurts.

This is for her.

This is for all of us.

We are no longer ugly ducklings.

We are swans now... wounded, perhaps... but wild and rising.

Ana Holt

Remember the day you told me that I had pulled you out of the water when you felt like you were drowning? Those words touched my heart with a powerful imprint, and as I replayed it time and time again, it took root in me like a seed, blossoming all around my heart. This seed grew rapidly, becoming a powerful sail of passion that constantly carried us to a magical world known only to you and me. You, of course, were the captain, and I was your ever-admiring crew, following your lead. However, this boat that you brought me into is now just a memory of the past. When the first storm came, you, our captain, abandoned ship, leaving me to sink alone.

Ironically, you went on to drown the very person who had pulled you out. The storm hit me relentlessly, swallowing me into dark waters. Fortunately, in the sea of life, I am a strong swimmer. Even during times when I felt hopeless, I managed to pull myself from the depths you left me in. Now, I stand on solid ground, once again able to breathe in the air of hope.

Today, as I reflect on our deep encounter, I find a smile on my face. It’s a smile born from the realization of something you longed for but that I never gave you. One night, you filled my mind with your endless fantasies, where I was your princess waking up next to you after a night spent fulfilling your desires. I smiled—and no, I chuckled at the thought that it won’t be you but another, a true captain who will enjoy your night fantasies you long for.

The purpose of a bowl is to hold, contain, or surround. When you apply this function to a large population of people, you capture an infinite concoction.

And I hide within it.

Pollution is my permanence in this place. The wind does not have the power to erase. My inner voice speaks in uppercase, UNLACE YOUR THREAD FROM THIS SPACE.

Bound by the bowl

I am one of trillions of parts to the whole. Buried beneath the smog like a mole. What I shared, this city stole My shame sinks deep into the frame of the bowl. My mistakes have nowhere else to go.

I try to filter them out dilute with fresher air, but they embed into the clothes I wear. Those around me offer a prayer. But it is a mask I do not dare to bare.

I am trapped inside a place called home. This inverse dome

Just as looming

The collective air consuming. The bowl is brimming. And my desires have reached the rim. Freedom is the bowl’s antonym.

Amie Schaeffer

My proverbial string has snapped

The point of hanging on long since passed

No gentle fraying over time

But abrupt and violent

I am gone

Only twisted fragments remain

And I cannot pick up my own pieces

Lina Vega-Morrison

Hated by many, tiny little creatures bark annoyingly at whoever bothers them. But Mari always defends them to the hilt, even when people complain; she argues and swipes at them, and nobody knows why.

What they don’t know is that once upon a time, Mari’s normal day included a small bucket by her bed, to pick up the pieces of herself before sleeping, right after a 6’4”, 210-pound shadow would break her. Mari had forgotten she was Mari and would go out to a little park in the middle of the day and stand right under the sun, where the shadow could not reach her.

After some years, one of those sunny days at the park, she saw a Chihuahua with a glitter collar just sniffing the grass, minding her own business, when all of a sudden a dog 8 times her size came up to bark at her so strong and so loud that even the grass around her moved. Right there and then Kiki, as her owner called her, stood firm on her skinny brittle little legs and barked with her stomach, her lungs, her little tail and even her 4 or 5 whiskers.

Mari, for the first time, thought she could bark at the beast even if she was only 5’4’ tall. Mari believed in Mari and barked from that night on like Cerberus.

Eventually, Mari left the beast and bought a stuffed dog: some dogs are better off alone.

Jonathan Reddoch

A merlot appeared before Eliza.

“From the gentleman in the brown cardigan,” the waitress shrugged.

Eliza raised her glass to her enthusiastic admirer, guzzled it, then returned to her wrinkled copy of Colossus

“Go on, Henry, steal a kiss,” Jack prodded, pushing his inebriated friend off his stool.

Henry sauntered over, half-speed, to Eliza’s darkened corner booth. He lowered her book with his unclean finger, leaning his crooked teeth toward her succulent mouth.

Her perfect teeth embraced his hooked nose, stripping skin to cartilage clean off.

He ran back to his friend, screaming wee, wee, wee.

She returned to her poetry.

The barkeep reappeared, offering Eliza a cloudy green jar labeled “Pickled Pig Parts.”

Henry’s snout joined un-idle hands, unruly fingers, unmentionable members, even offended eyeballs

Jess Challis

at eleven, I didn’t know god I made friends with the fireflies on my bedspread confined to their two-dimensional sky, a charlatan of cornflower blue, futile webbed wings frozen in flight, sun-bleached yellow splotches, not at all like the first time I witnessed them at dusk in an overgrown field outside a dumpy motel in Iowa one thousand flickers of bliss and chaos in one thousand fated bodies now their effigies are tucked in awkward creases around my heavy heels never noticed the finality of a net I picked this print the greed of a child a jar with a lid screwed on tight

Sharlee Mullins Glenn

I chose you that day— plucked you from the brood, the tangle of siblings, the tumble of home.

I said I needed someone to advance my slides— flickering images in a dim gymnasium meant to hold the attention of two hundred squirming children, K-6— but, of course, anyone could have done that. I wanted you, my beautiful fledgling boy caught between childhood and pubescence. Just you this time.

We left before dawn, drove the two-and-a-half hours north to Nibley Elementary. I felt a flush of secret pride as you watched students and teachers alike (even the principal, and especially the librarian) treat me like a celebrity for having published a few midlist books.

The shadows were growing long as we flittered back to the car and headed south toward home. I let your happy warble wash over me like a mountain stream well-knowing that the unfathomable alchemy of puberty could claim you any day now, silencing your unaffected chatter.

The sign rose sudden— Bear River Migratory Bird Refuge a name as regal as wings in flight. I’d wanted for years to explore this space, let these wetlands whisper their secrets to me, follow the pull of water and sky into this place of precarious sanctuary.

I’d hoped to get home before dark, and time was tight, but there was time enough and when would there ever be time again?

I turned off the exit that unraveled like a seam from I-15. Twelve self-guided miles of wonder, you beside me, your hand tracing the horizon where the river spreads and flows into the northeast shore of the Great Salt Lake.

The marshland shimmered, silver-salted, its reeds raked by wind, its mud teeming with brine shrimp— threadlike lives caught between being and beak.

Here, silence wears feathers. Hundreds of avocets teetered then took flight, ink-tipped wings stroking the sky’s ribs. Tundra swans glided through cattails like tufts of untouched snow. A flock of white-faced ibis— wine-dark bodies, metallic wings— rose like a wave from the pondweed.

The air trembled beneath them.

We were transfixed. It was like seeing birds for the first time: marbled godwit, cinnamon teal, snowy plover— names like incantations lifting them from page to sky. Transient birds, nesting by the thousands on this stolen land (of the Ute, Shoshone, Paiute) on this stolen afternoon.

A great blue heron startled us into silence, its elegance an answer to a question we had not asked. A pelican skimmed low, its wings a shadow over the car.

I slowed to a crawl wanting to stretch time long and straight like the nighthawk’s flight toward some distant, unseen destination.

How I longed to keep you there forever in this place of safety and protection.

When the sun collapsed into the reeds we lingered still watching a solitary shorebird thread its way through the amber haze.

I wanted to tell you: this refuge is a lie. And, yet, it is also the truth. Nothing stays, but here in this place

for a moment everything comes home; everything is safe.

Instead, I said nothing only took the long way back, you nesting against me, sleeping, the car heavy with the scent of water, the beating of wings still sounding in our ears.

Emily Howsley

Born barren in a barren land

But like a cartoon from my youth,

There’s more than meets the eye

But few bother to see

Belt snaps and face slaps

Why can’t I be like the other girls?

Decades of being ignored, passed over, and dismissed

Nah too ugly, he said

Dirt roads after a monsoon

Sweet smells of mesquite as a sunset painted the sky purple, pink, and orange

Rural life with saguaros, scorpions, and rattlesnakes

120-degree summers

Invisible in the shadowed fringes at every dance

A wallflower who never has bloomed

A sweet spirit who ended up in Zion

Broken family led to a broken marriage because according to God, my womb – my whole purpose of existence –wouldn’t cooperate

Ignoring his past drug use and secret relapses causing low counts

Collect calls and bail bonds

No wire bras and metal detectors to visit family locked away

While thinking of family that should have been World traveler still looking for home

Chifles lomo, and English conjugations

Occupying the space between gringa and local

This is the place, but even returning after 70 pounds lost was not enough

Feeling and noticing the judgmental sneer as I looked at mascaras at Ulta because beauty isn’t me

Trying to find balance between faith and reality

Almost no contact with my mother and my abusive father died – but at least they taught me to take care of my teeth – only 1 cavity.

Almost 46 and my female doctor asked me if I was planning on having kids.

Barren hopes held in a barren heart that is still trying to break free.

Michaela Rae

You say you’re lost, marooned on a beach but This ship didn’t sink Spontaneously

You curse the moon, was her tide pulled you in On waves of liquid Your fists pound my shore

Small stars stay quiet, waking in the night To the crashing sounds That drown your sorrow

Sheets caught up in wind, a masthead blares bright The coast guard sighs, ‘Boys, He’s washed up again.’

Jess Challis

Jess Challis

It’s a week of poetics: words on the page, pain in the nerves. I meet parts of my body that before spoke nothing. Ruthless, they teach me that before I knew nothing.

I cry at speech therapy against my will. The thin-lipped therapist finishes the assessment, proving low proficiency, afterward adds “teary” to my medical record and confirms that language, my old lover, has become impassive stranger.

At the infusion clinic, my doctor asks for the latest line. I give him Ada Limón’s:

“Funny thing about grief, its hold is so bright and determined like a flame, like something almost worth living for.”

In turn, he shares a piece from SPAM-ku, says he wishes he had time to study poetry. I quip his profession pays better.

In the hall, new administration installs a whiteboard with well-wishes and inspirational quotes. I hobble over to add:

Iana Noda

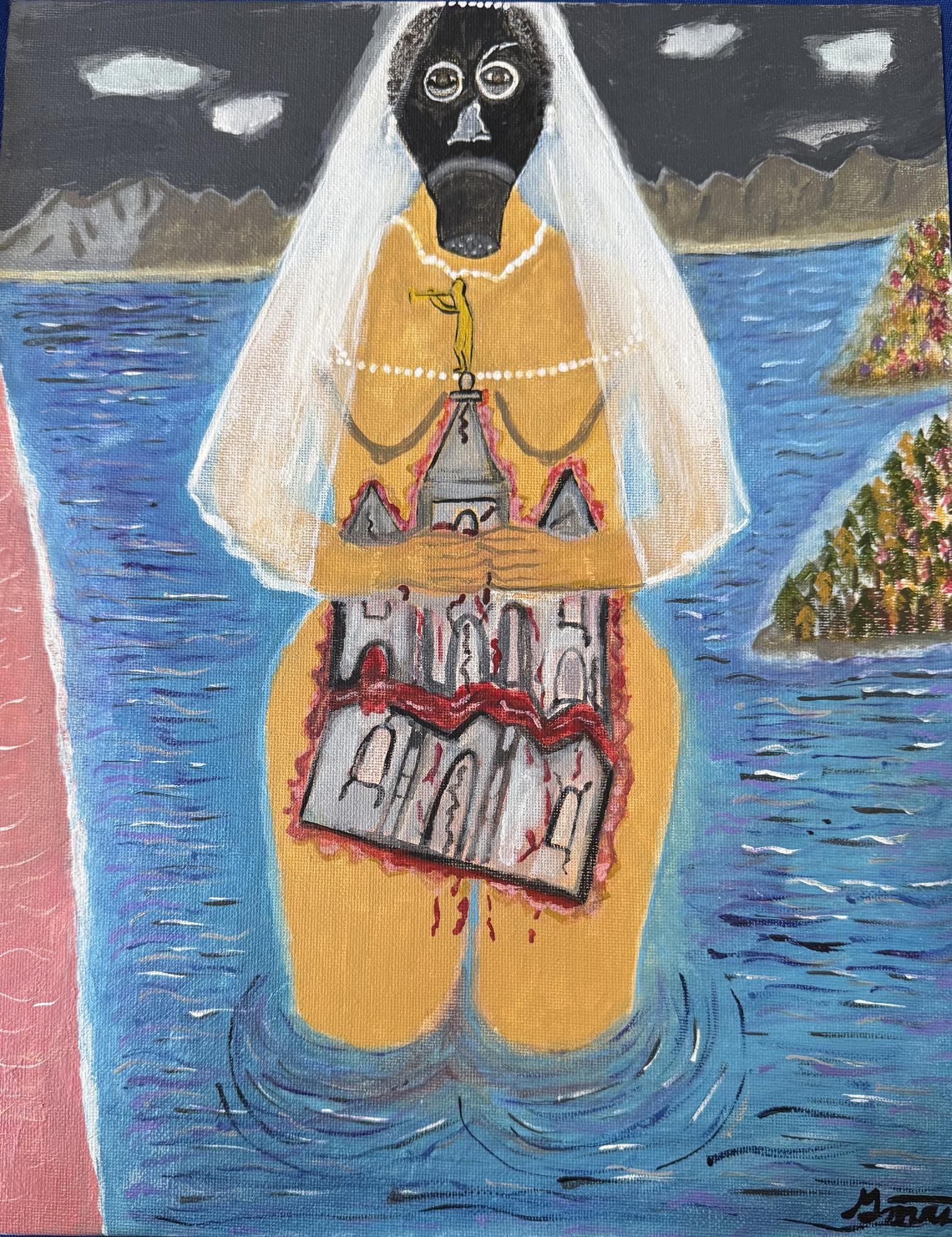

This painting tries to capture something many women know well: the need to look fine while feeling anything but. It’s about the quiet, constant effort to conceal what’s happening beneath the surface. I grew up as a pastor’s kid and lived in different countries. I saw how religion and culture influenced what women were expected to be like. The message was usually the same: be nice, look pretty, and don’t cause trouble. Today, the message has changed, but the pressure hasn’t gone away. The modern woman is expected to do it all—and do it effortlessly. Have a career, raise a family, stay in shape, be stylish, stay positive. It’s supposed to be empowering, but it feels like another impossible standard. In Utah, where tradition and modern ambition meet, a woman gets double the pressure. And when we see other women pulling it off, it gets even tougher to admit we’re struggling. So here we are. Wanting to belong. Afraid we’re the only ones who can’t keep up. Using everything we’ve got just to make it through the day. This painting is both a cry for help and a tribute to the strength it takes to simply hold it all together.

Debra Ma

“Lay by me.”

That’s how it usually started. Little Debra in bed, surrounded by stuffed animals, patchwork quilt wallpaper, and bright red carpet, which took on a burgundy hue in the dark.

“Please, Momma. Lay by me.”

She’d look at me with that stern schoolteacher look. The one sharpened by years of handling rowdy second graders. Then, just as I braced for a “no,” her mouth would soften, corners lifting in a barely-there smile. That’s when I’d know: five minutes, ten if I was lucky. I’d have her.

“Tickle my back!” I’d plead.

She was a master at it. Her fingernails would skate slowly across my arms and back, coaxing out a tingling calm. I would often fall asleep right there.

Other nights, I wanted more.

“Tell me a story.”

Mom had already worked a full day, arrived early, and stayed late grading papers and planning lessons. Her bag was always full of papers, notebooks, and pens, begging her away from me. Some nights, those papers won. But when I got lucky, she’d lean in and whisper,

“I’ll tell you the story of Jackie Menori”

“That one?” I’d groan.

“My story’s just begun,”

“Yes, Momma, please! This time, please really tell me.”

“Should I tell you another, about his brother?”

Yes. Tell me the real story!”

“And now my story’s done,” she would end.

“Oh, not that one! I want another one!”

I’d groan, we’d laugh, and hug. Sometimes I’d steal a few more minutes, a few more tickles. But even on the tired nights when Jackie Menori was all she had to give, I felt loved. It was enough.

Years later, our roles reversed.

In 2012, the world was supposed to end. It didn’t, but our world did in a way. My nephew tragically died. My brother was devastated. Mom’s heart broke. Then it began failing her, literally. I moved her into my home. Dressed her. Bathed her. Held her hand when she couldn’t stand. I installed a chair lift. Changed diapers. Kept a baby monitor by my side so I’d hear when she called out in the night.

Four years later, my daughter’s wedding came. I moved Mom into a fulltime care facility nearby, promising it would be temporary. But when I came back, she didn’t come home with me. My daughter had helped me care for Mom, but she was now starting a new life. I had to decide: quit my job and bring Mom home, or leave her in care so I could keep working.

I made the tough decision to leave her there. I had two boys about to enter those trying middle school years and a husband who had taken on the lion’s share of raising them. Everyone needed more of me. I once asked Mom how I could repay her for all she had done for me, “Just do the same for your kids. That’s all I would ever want.”

I visited Mom often but didn’t stay as long as I should. Some days I was too tired. The kids had homework, or my commute had already taken two hours of my day. Life happened.

It was late one night, Halloween eve. I sat by her side. I talked to her about how I knew it was a holiday she had never enjoyed, even as she ensured I had the best vinyl store-bought 1970s costume that money could buy. She wasn’t saying much. I sensed something wasn’t right, but the nurses reassured me that her vitals were fine. I told her I loved her and kissed her cheek. I was tired. The boys were texting me to watch a scary movie with them. So, I left.

The next morning, a voice nudged me: Call

I picked up my office phone and dialed carefully. The nurse assured me, “She just had her morning shower. She’s resting.”

“Thanks for letting me know.” Feeling reassured, I placed the phone back in its cradle.

Almost immediately, the phone rang again. My brother.

“Debra, I’m here with Mom. She’s gone.”

Gone.

The words echoed through my head as I drove. All I could think about was how I wasn’t there in her last moment–I should have been. I shouldn’t have moved her there. I shouldn’t have left her.

I think about Jackie Menori often. How Mom always tried to give me everything she had, even when she didn’t have everything to give, because life was happening. In those final days, when I couldn’t give her my all, I hope what I gave her was enough.

I googled it, that silly little rhyme. “Jack-A-Nory” was the real British rhyme, but our version was “Jackie Menori.” I’m certain this is because that’s the way my little brain interpreted and repeated the name. I realized changing the name of the main character was another of the many things she gave me.

“I’ll tell you a story About Jack-a-Nory, And now my story’s begun; I’ll tell you another Of Jack and his brother, And now my story is done.”

We laughed, argued, and sometimes cried over that lame, insufficient story. Even so, it was always enough. Love was enough. She was enough. And maybe, just maybe, I am too.

Jess Challis

Cathren Cougill

51 pronouns... and we’re all talking about pronouns these days —which is actually a good thing but do we dare radically challenge or change these 51 yet?

Has our country seriously not glanced at these 51 since they were penned? Do we know where they are located? Have we had conversations about these 51? If so— Obviously, not enough! Do we see that they exist or recognize their damage which still persists?

Have our hearts weighed in on the heaviness these 51 pronouns hold? Find them, count them, hidden in plain sight they are— bold in their implications— Generational consequences!

And what about “Savages”—the word? It, too, still remains in legal print, hanging in another hallowed document

with the ugly clause “three-fifths” of a person…

Or what about the absolute absence of other pronouns— We know the ones— that stand in for those deemed property, legally bound, 2nd class citizens, pretended equality or married into another’s identity? To this day, my address can read Mr. and Mrs. Scott Cougill— Just where did I go?

It’s oh so easy to gloss over pronouns their primary importance or presumed insignificance —not consciously registering absence, presence, or initial intention.

Some might say it was the economy, or immigration, others will emphatically state it was her policy on... —fill in the blank!

But I say... it was the pronoun. Because, as women, we aren’t even found in The Constitution... How could we even begin to think let alone believe... a She would become President?

Earth Michaela Rae

Samantha Stubbs

Peering down the concrete path, the unevenness of the sometimes-cracked payment seems to go on never ending like the paradox of a mirror gazing at another of its own. The sidewalk is coated in yellow and orange leaves from the thick trees that overhang the walkway.

To your left is a brown brick house. White paint peels from the wooden front fence. Standing alone in the yard is a light, its white paint falling away from rust. You cross the crunchy yellow grass to the front door. At its base sits a metal toad with an unending gaze. Behind the door is a darkened red carpet that marries pink walls kissed by many hands.

Up the split stairs and on the second door to the right you stand at the door frame. The sheer window shades across the room sway to brush the oak bed frame that spires in each corner. Many times, you have slept on that floor with your head at the foot of the bed, never looking up at the darkness that seems to huddle near the bottom of the headboard. Laying there you fear that it will reach out. It might gently scratch the crown of your hair, so you always tuck in to hold your head with your arms. The worn carpet is rugged against your skin. You must curl up your feet so that they don’t meet the closet. Behind the bi-fold doors lies a wood foot that pinches. You huddle no differently than the darkness, equally afraid to be touched.

Up the split stairs and on the second door to the right you stand at the door frame.

You are standing at the door frame. Standing at the door frame. Standing. Door frame.

In the room is the grandfather dresser that looms seven drawers tall. When you pull out its drawers it smells of playing cards and pennies. Rummaging through papers and padlocks, you find the pink glass dish that holds pins, picks, and a key. Pinching that key out of the glass, you know you found the one.

Up and out to the hall, you speed back down the stairs, rounding the stair banister to go down the next flight, not stopping until you hop onto the center stair of five.

The railing to your side is missing a prong but it is not quite big enough to fit your head through. On the other side of the railing are books that call to be sung. You don’t know how to sing. Sometimes you splay out the books and cast out your finger to exclaim incantations of trickery. This time you do not reach for the books. You slowly take the last two steps.

Here at the foot of the stairs the light brown carpet meets the lighter brown carpet. Turning the corner, you see the blue flower room where you know a panther sleeps. You hear to leave that door unopened and undisturbed. Further around the corner there is the final set of stairs. The dark stairs. Each stair step disintegrates into darkness as you peer down. The back of your neck tingles, and you squeeze your hands to feel the tips of your fingers. Cool air whispers at your ears, and tickles at your temples. You have gone down these stairs before. Each step is taken with trepidation.

At the bottom of the stairwell there is a hallway of four closed doors. You know to never take the door to the left. Always take the door to the right. You turn the round knob of the right door. The latch clicks free. The door sighs as it gives. Around the door frame, your hand smacks the switch to relieve the dark of its lingering duty.

The concrete floor of the corridor behind the door is revealed by the white paint that has worn away at the center. Reaching to the ceiling are wooden shelves of the same white. At the end of the small room sits a chair. Moving toward the chair, you tiptoe to avoid the uneven and cold cement. You tensely shrug your shoulders inwards in hopes that nothing will reach out. Glancing side to side you take in the contents of each shelf. They are littered with food stuffs and bins, dolls and ornaments. The chair’s seat of piling, polyolefin fabric is home to an array of dusty refuse. Toppled on each other are rusted ice skates and a split cinder block. Fallen over the chair is a cracked glass candy-vending machine. At the metal base of the chair stood a bowling ball, surrounded by stacks

Once at the chair you hesitantly lower yourself to your hands and knees. Ducking your head to look underneath and behind the chair, you stoop lower to lay on your chest. You reach to the wall and brush your fingertips along until you feel a disconnect in the surface. Fixing a fingertip on the seam, you reach down with your other hand to your pocket to grab a purple-stained popsicle stick. Using your fingertip as a guide to the seam, you wedge the stick to pry. The popsicle stick nearly splinters before the concealed door gives way. The stale air hushes from the small opening. With your arms still leading, you leverage your foot against the post of one the shelves behind you to push yourself forward. The underside of the chair scratches at you as you scoot. With your torso through, you grab onto a wood plank ahead to pull the rest of your body in.

Pulling yourself up to your haunches, your head brushes on the familiar low ceiling. You pat at the floor until you find the small flashlight. Illuminating the walls, you pull the little door shut. In the corner is the glossy, black latched box. Fixing the key in the lock, the lid pops. To your surprise, the box’s velveted interior is empty except for an oblong mirror trimmed in gold.

Jess Challis

I’m sick as a dog for months and when I look in the mirror all I notice is how my arms have leaned from atrophy, I finally have a thigh gap, and now I have time for beauty sleep.

When my sister tells me with concern that I look like I lost weight, I hear: You’re finally skinny.

My daughter told me she thought I was dying.

When I was her age, I was spinning in a playground centrifuge, felt the pull in my belly, the urge to give in to the momentum.

Back then, I thought I could throw a rock as far as I wanted, all the way across the river.

Jane Finlinson-Hodgkinson

“How did you do it?” I ask my mother, noticing how her hair is now, mostly the monochromatic hue of what the fire leaves behind.

I avoid glancing at it too long as if the touch of my gaze would cause it all to blow away with an extended sigh.

“Do what?” she lifts her too-small dog onto her lap, lavishing it with attention.

“How is it you became invisible?” I say, biting my lip, comforted that it Stings just a little. Comforted that when she looks up, Our eyes meet.

I expect her to deny she ever had such a power or a curse, but she pauses, as the dog wags its tail expectantly.

“To ask such a question, is to understand, in part, what it is to be a mother.”

The tea kettle’s screech startles the poor dog, who leaps to the ground and barks.

She takes hers hot, without embellishment, and I can’t help wondering if she ever found it sweet enough.

Jane Finlinson-Hodgkinson

Deriving from the wordsmamma, meaning breast gram, meaning recorded.

A recording of the breast via x-ray, searching for the kind of growth that can kill a woman.

I think of the pressure of being,

a mamma, a grandma, a woman.

The squeeze we feel throughout our lives stretched in a million directions. At times a crushing weight, where we feel the pinch of trying to live up to our own expectations.

Daughters, employees, friends and sometimes lovers.

Loving ourselves enough tolay it all on the table, for the opportunity to do it over again another year.

Jess Challis

After my son was born, I went to a mental hospital. When they let me out into the wild world again, I took my children to a botanical garden every morning at 10 am: a space of organized nature manicured by man. Plants were brought there from faraway places, so many burgeoning bulbs planted in the still-frozen grounds. Tulips were their specialty. I preferred the irises, though relatively sparse.

The managers advertise that they have the largest manmade waterfall, which was someone’s victory. Water falling down, down until it was pumped back up to fall again—like the life of a young mother. The fall of one’s strength down down with the next cry or the next shit in a disposable diaper, and the rise of will again to only fall down down down again.

One day I met another mother. Mothers mostly had a way of ignoring each, pushing one stroller past its sister, each going home to our own houses in our respective corner of the suburbs, to our own husbands and our lonesome lives then back again to the overpriced gardens.

The woman I met was different. We were sitting by a fountain in a small garden hidden from the rest of the grounds, garnished mostly in roses— not in bloom yet. Our daughters were splashing together. The mother spoke to me, and I looked up from the fountain, surprised. “Did you see the mama owl? She made a nest on the cliff of the waterfall. Just look down and you’ll see her.”

The other mothers had congregated on the bridge, parking their strollers in the middle of the pathway. “She’s there,” they pointed and I saw her: shifting slowly, shivering her sleek, white feathers, speckled with dark

brown or black; hiding her precious eggs, back turned to the world, she makes it look like the simplest act of all; cooing and hooting softly, like a musical version of the old ladies at brunch. Her nest was on a shallow ledge of a steep cliff. She seemed free of resentment, to not to mind at all the long days and chilled nights, continually protecting her eggs from predators, all while observers gawk and point, the same obnoxious comments over and over.

I came day after day. For a month and a few days, she sat there steadfastly until the eggs hatched and there were babes. Young ones to think of more than herself.

One day, she was gone—the babes too—the nest bare except for piled bones of rodents fed to her young. I was alone again on the path, pushing past one pram after another, staring down at the fine gravel, never to speak again.

Michaela Rae

If I could go back, I’d tell the girl I used to be:

You don’t have to hurry. Adulthood isn’t a prize, It’s just a room with heavier air.

Don’t fall in love just to feel seen. Don’t chase ghosts in the shape of boys, They only know how to disappear.

You are already enough. Even in silence. Even when no one is looking.

Sing badly but often. Make art for empty rooms. Take the long way home.

Write what scares you. You don’t need permission. You never did.

But here I am, and the woman I’ve become admits:

The bright-eyed child remains. Not lost or replaced, marooned by the years.

She became colder.

Skeptical of the trick of joy. Doubtful of the lure of love.

The girl’s just out of reach. Like trying to touch light underwater.

Now, I watch my daughter laugh Sunlight kissing her carefree skin I feel the urge to join her.

But I am wrapped in stillness. I carry this heaviness like a second skin.

Gloria Arrendondo

Gloria Arredondo

De pequeña, rendí honores a una bandera tricolor que tenía incrustada en el corazón

Y ya adolescente, juré fidelidad a otra, menos colorida, que prometía una vida mejor

Con libertad y justicia para todos

Eso constituía todo mi sueño americano.

Canté el himno de mi nueva patria y seguí sus leyes al pie de la letra, esperando por años, con anhelo, un certificado oficial de pertenencia. Aunque nunca pretendí ser mujer blanca, pues mi cordón umbilical yace enterrado en mi tierra.

Mi sueño americano abruptamente se desintegró cuando, de pronto, se hizo un delito existir con mi color de piel.

Y se dijo que yo era menos por eso, y por ser mujer. Mi mente, mi cuerpo y mi espíritu se estrujaron al entrar en esa realidad alternativa y caótica, de mentiras, de odio y promesas estrambóticas, envueltas en la bandera con el lema: “Make America Great Again.”

Todo empezó como una malacanchuncha descontrolada Nos marearon con una emergencia tras otra: incendios, aviones caídos, desplome de sistemas vitales de bienestar, recortes monetarios, deportaciones masivas... Se ignoraron el debido proceso legal, la historia y la lógica elemental.

Y un día, ilegalmente, el Golfo de México ya no era más.

Las acciones de este gobierno

son nocivas para la salud mental: un gaslighting intencional. Desde aranceles ridículos, hasta bullying internacional. Reinan el racismo, el clasismo, el colorismo y todo lo que termina en “-ismo”.

Y a mí me aterra la falta de empatía y humanidad de quienes ejercen mandatos fuera de todo principio legal y constitucional.

Estados Unidos de Norteamérica; ya no queda ni tu sombra, ni el sueño de lo que fuiste. La justicia parece cada vez más y más lejana. Escudándote en la religión, has llamado a la cacería humana y cometiendo crímenes contra la humanidad en nombre de la pureza de raza.

Gloria Arredondo

As a child, I paid tribute to a tricolor flag that was etched into my heart And as a teenager, I pledged allegiance to another flag - less colorful but one that promised a better life Insured by Liberty and justice for all. That’s all my American dream was.

I sang the anthem of my new homeland and followed its laws to the letter, waiting for years, with hope, for an official certificate of belonging. Though I never pretended to be a white woman for my umbilical cord lies buried in my native land.

My American dream suddenly disintegrated when, one day, it became a crime to exist in my skin color. And they said I was less— because of that, and because I am a woman.

My mind, my body, and my spirit were crushed by the weight of this chaotic, alternate reality: of lies, of hate, and extravagant promises, wrapped in a flag bearing the slogan: “Make America Great Again.”

It all began like a tilt-a-whirl

We were spun around with one crisis after another: wildfires, fallen planes, vital systems collapse, budget cuts, mass deportations...

Due process, history, and basic logic were ignored,

and one day, illegally, the Gulf of Mexico no longer was.

The actions of this government are toxic to mental health: an intentional gaslighting. From ridiculous tariffs to international bullying, racism, classism, colorism, and every other “-ism” reigned. And what terrifies me more is the lack of empathy and humanity from those in power— those who act outside every legal and constitutional principle.

United States of America; there’s not even a shadow or a dream left of what you once were. Justice feels farther and farther away. Hiding behind religion, you’ve called for human hunts and committed crimes against humanity in the name of racial purity.

Gloria Arrendondo

Rachel White

Not every apricot can come to fruit without harming the tree— how distressing to pick and choose, break off many to let others grow, and how necessary.

Samantha Stubbs

Solemn wind hushes over an aching desert forgotten by the harsh light of sun. The lividus cloak of dark droops over a solitary house. Through the front window shattered by resentful rocks lingers a dull light. Lazy glows of amber illuminate glass scattered across the worn, weathered wood of the porch. She steps so as not to puncture her shoes as she pushes through the front door left ajar. His body is slumped on the wall, legs splayed out, his boot the aggressor of the lamp lain on its side. In his lap leaks a sloped bottle of spirit. She creeps passed and up the short stairs. ‘Round the corner to the end of the hallway, she gently opens the door. There her children sleep, huddled together in winter coats. She fixes the blanket over them before slipping off her working shoes and nestling next to her youngest.

The cloudy beige countertop is littered with serving bowls, pots on warmers, and a stack of clean dinner plates. The smell of sweet corn and savory roasted beef laze through the air. The warm oak floor underneath the pull-out cutting board is warped. We jump on the raised board to hear it creak, Grandma ordering us out of the kitchen. A tablecloth is thrown into the air before it floats down to the table. Big kids bustle around in turn to set the table. One has the forks, another sets the plates, and a third places the cups. The tabletop fills with serving bowls, salt, pepper, & cayenne. Bums find their places on the squeaky bench that is backed by a loose sliding door. At the head of the table grandpa clears his throat. The wall behind him is adorned with painted decorations. A rosy cheeked witch smiles down at us all.

We had this red and white jump rope. This rope was known for stinging shins worse than any other jump rope. Someone stole it from school and brought it to Grandma’s and I stole it from Grandma’s. The rope was discolored, and the links were scuffed, worn, and sometimes missing. Me and my sister were left home alone, and our usual fighting ensued. I shoved her into her room and held the door shut as she yanked and screamed for me to let her out. With one hand on the door, I reached with

the other to grab the old red and white jump rope that was on the floor. Still holding the door shut, I tied one end of the rope to the doorknob. After securing the end, I backed away from the door, keeping the tension until I reached the open closet door on the other side of the hallway. I tied the remaining end of the rope to this doorknob. Closing the closet door tightened the rope, holding her door closed.

The road curved sharply along jutting faces of stone as we wound upwards to a small town in the mountains. Long before we made it to our street the cracked pavement faded to dirt. The light of the sun was leaving as we slowed to avoid each bump and hole in the road. We eventually pulled to a stop, headlights illuminating rusty metal gates that hung crooked. The cold chain that held the gates together lazed in the dirt. It traced a weak arch in the sand as the gate was swung to let us through.

I wake up to a curved ceiling. I sit up and look around. I am on a mattress on the floor. Behind me there are some storage cabinets and my little suitcase. I can see the morning blue sky through the windows on either side of me. I move for the camper door and pull on the latch. I yank at it until the door bursts open, nearly falling out onto the crooked steps below. Outside the camper door I see a massive overhanging tree, below it there is a roofed, wooden ramada with peeling yellow paint. Through the doorless entry of the structure I could see my dad cooking on a stove. Barefoot, I stepped down into the cool dirt to cross over to the makeshift kitchen. I watch him pour some eggs out of a hot cast iron pan into a blue speckled enamel bowl. He turns to the fridge to grab out a glass bottle filled with orange juice. I sit at a small metal patio table to eat breakfast. Looking around I see that my dad’s home is an old Airstream camper. The wheels are long gone, and the shine of the all-aluminum exterior was dull. In its reflection my attention was brought back to the canopy of the tree looming over us. I twisted in my chair to get another good look at the tree. “You know Dad, I have always wanted to have a tree house.”

- - -

Music is blaring and neons are glaring while brilliant TVs flash. I startle as a bottle crashes to the ground nearby, broken glass laughing. The smell of beer bullies the air. I lean into the computer monitor to make

room as a food runner squeezes by, the hot food teases my empty stom ach. I shift my weight from one foot to the other, shoes clinging to the sticky floor.

6 hot buffalo bone in all flats ranch

A drunken man leans in too close, his alcohol-tinged breath attacks. “Hey, swee har? Yu sh smile more.”

Ezra Jean Hipwell

I read the poetry made by all the thin beautiful girls who had prodigious and worldview shaping sex during high school and college, and how they write in red pens and speak of blood and teeth and menstruation and things female and divine and terrible. I think on how I was once thin and beautiful and how men would teasingly admonish me and slip me crumpled ones and fives while I delivered their plates of heaping food and bussed their dishes and smiled at their babies, labor that would transform me into a hulking and powerful dyke-woman, labor that begets other girls phone numbers and references and friends and husbands who eventually come in and demand to speak to the person in charge, who is me, eternally wiping down a table even when I am somewhere else, someone else. No more am I slipped ones and fives, except by other dyke-women, who smile coyly and give compliments like a wrecked ship gives driftwood. I think on how I once had ratty bleach blonde hair that suited me as poorly as being thin and beautiful did and hid my true nature about as well. I read the poetry the thin and beautiful girls write. I think I understood what they meant once. Maybe. I think of the boring and worldview-confirming sex I had. It was not violent. When it hurt I went somewhere else. When it was good, I stayed. There is not much to say on the matter.

I am a poor judge of whether their poetry is good. I wouldn’t know.

Do you see how we all sway with the wind?

That’s how you should be, my dear— that’s how we are and have always been.

She, she was already tired of holding up the leaves, of giving coconuts, more leaves, and more coconuts, of growing, of thinking about being taller, more flexible.

She stopped talking, stopped absorbing nutrients from the soil, and turned her leaves so even the sun wouldn’t touch her.

She let herself dry out.

She believed, until her very last second, that she would reincarnate as an oak tree.

Dangle to my knees, you milk-making mountains— once perky, now pendulums swinging with stories— of overfilled bras, milk-stained shirts, and babies who knew exactly where to find home.

You fed my children before they ever knew my name. It was us against everything— the world could wait while they drank and I watched, anchored by the rhythm of their need and my giving.

And when you visit my knees, say hello to the soft, silvered map stretched across my stomach— lines not drawn in shame, but in the push and pull of skin becoming shelter.

They call them scars, but I call them lullabies I can hum with my fingers as I trace the ghosts of their tiny feet— reminders that I carried them before the world did.

Oh, body— my body— you have made miracles. You are a miracle maker. A creator. A goddess, full of power embodied.

You are the altar and the offering. The beginning and what remains. A body of work. A work of love.

You are still mine— miraculous, marked, and holy.

So, dangle if you must, you mountains of milk— you’ve earned your rest and carried more then they’ll ever know.

Jess Challis

1. Alaska is to place as I am to Ketchikan Creek, water flowing towards the ocean

2. with the salmon mothers fighting upstream to where it began

3. if I lie very still here in this forest will they discover my liver, claim it as a town

4. will my sunken lungs be captured, christened Clam Gulch

5. how long does it take for every finger of my right hand to be raised and planed into bone timber

6. my gaping mouth, my muted throat the shaft of Red Dog Mine

7. my uterus repurposed for the cog factory [shares a wall with the brothel and the slaughterhouse]

8. my spine sieged, a steep railroad up the crest of my crooked shoulder blades

9. part by fracture we become

Terry Brinkman

Charity of the neighbors absurd

Wolf in Sheep’s clothing we accept Guardians and Monks, we slowly crept

Daughters bearing Palms to cover the Blackbird

Holy youth group sleeping with the Bluebird

Where-on were women blessed slept

Dragon Lilies on robes resting we kept

Watertight boots eyes of Lady-dove

Gradual vaults arise archery

Sprinkled viands baker

Blessed water cereal flakey

Pockets around the house faker

Jaunting equidistant rays shaky Ancient Irish Vellum for the Dressmaker

H.E. Grahame

I build no lofty pedestals because falling from such precarious heights can be fatal and falling is such a human thing to do

I collect phrases and measures like rare gems collected in jars brilliant as sunlight floods through

Cee forged cornerstones and bridges unwavering anchor while Em challenged machination and ruse relentless determination

I fashion no delicate masks because cracking from such fragile perfection can be fatal and cracking is such a human thing to do

I collect attributes and meaning like intricate charms strung on threads radiant as moonlight whispers along

Elle embraced compassion and kindness unapologetically true while Kay cultivated fortitude and resilience weathering every storm

I compose no rose-colored anthems because hoping from such fragile heights can be fatal but hoping is such a human thing to do

Jess Challis

I’ve seen grown women eat baby food from miniature glass jars with metal lids that pop like a jack-in-the-box, their wrists contorting at a familiar angle, delighting in the proper friction and release.

The mothers must eat it with a tiny spoon coated in non-baby-cancer-causing rubber to protect their gnashing teeth.

When I see houses destroyed, boards, shingles and couches strewn strewn across their lawn, I can’t help thinking tornadoes only do their best.

Elizabeth Suggs

Ambur Wood

I made a deal with the devil and sold my sister’s soul to save my own. I told him she was juicier, that she’d make the better meal—one seasoned with unsated hunger, of forgotten children and lost innocence. He agreed, promising I would flourish while she would wither.

No matter how deep I spiraled into my own rabbit hole—telling myself I wasn’t that bad, that maybe I could even save her—he would slit her throat. Not with a blade, but with the drugs she forced into her veins. She’d swell with infection, rot with disease. Then she’d vanish, and the only mark she left on this world—her baby boy—would forget her face. He would become my mother’s son and not my sister’s child.

By then, I’d forget she was my sister. I’d forget that I ever had a sister or ever made a deal with the devil. And I’d live the rest of my life in bliss, allowing myself to really believe I deserved all the good that’s happened to me.

The church can run without me, Or my family, for that matter. I’m not here to be submissive, I can be more than just a mother. You don’t allow us any authority, We bow to your every whim, We don’t have any say, but, We could add more than soprano to your hymns.

We can’t baptize new members, Or our children, as a matter of fact.

We can’t confirm with a laying on of hands, What could OUR blessings possibly detract?

We can’t bless the sacrament, Are we not good enough even for that?

If every woman sat out of church, Would there be any impact?

We can’t be the Bishop, Much less Counselor or Clerk. We’re taught, “It’s best to stay quiet,” Our opinions aren’t valid regarding the work.

We have absolutely no hope, Of becoming the next Prophet, Or even one of the General Authorities, We’d be far too honest for that.

We can’t seal our friends in the temple, We can’t, “preside, protect, provide.”

All a woman seems good for, Is an eternal baby supply.

So, you can keep your glorified boys club, And your wanton disregard.

There’s no way I’m coming to church, To worship your negligent “God”.

Jess Challis

Jane Finlinson-Hodgkinson

Blood begins to flow freely, racing past her upper lip and plummeting down her chin. Brooke instinctively raises her hand to pinch the soft lower part of her nose just below the bony bridge to staunch the menstrual bleeding. Even so, the tips of her fingers are glazed in bright cherry red as if a toddler had attempted to give her a manicure.

A quick trip to the bathroom, and she rummages through the cluttered cabinet. She reaches for an unopened box of tampons. Brooke grabs a couple of them, discards the pink and purple plastic surrounding the hygiene products, and proceeds to stuff the absorbent cotton up her nares. Leaning over the quartz sink, she spits out crimson strings that seem to hang in place before disappearing down the drain.

It’s Friday, so she takes her time walking over to the closet and picks out a nondescript set of dark colored clothing. She fills a steel blue water bottle and then jams everything into her backpack. Brooke is running late as usual. She knows Genevieve won’t care, but Erica will undoubtedly be bitchy about her tardiness.

Brooke opens the gym doors and is greeted by an Arctic blast of air. Her eyes scan the four corners of the building until she spots her friends.

“You made it!” Genevieve, a towering blonde, signals for Brooke to join her by a long row of treadmills. The women each wear an assortment of tight leggings paired with racerback tank tops and overpriced athletic shoes.

Erica glances up from her sleek sports watch and glares at Brooke, raising her eyebrows. Genevieve, who is accustomed to refereeing the long-standing tug and pull between Erica’s neuroticism and Brooke’s freewheeling, elbows Erica.

“You told me you’d cleared the morning, don’t pretend to be so put out.”

“When you have kids, there’s no such thing as a clear schedule.” Erica pulls her dark hair back into a tight high ponytail.

Genevieve nods as if she understands, which they all know she can’t. She doesn’t have kids and has more free time than either of them.

“I told you I’m happy to babysit.” Genevieve offers a mint to Erica. “You need to be doing more self-care.”

Erica pops the pill-like sphere into her mouth and instead of sucking on it, chews the mint loudly.

“I promise you, I set my alarm.” Brooke tries to smooth things over. “I can’t help that my period started this morning.”

“It’s fine,” Erica replies with a not-so-subtle eye roll. “We just won’t have time for coffee after.”

They begin to stretch. Brooke’s arms and legs feel heavy as she struggles to imitate her friends’ more difficult contortions. She’s wishing she could breathe properly through her nose.

“You really ought to hit the dry sauna before our next workout,” Erica advises, watching her struggle. She, of course, matches Genevieve’s positions with cookie-cutter accuracy.

Brooke strains until she feels like her muscles are ripping apart, head still down, her right leg impossibly elevated. She maintains the stance until one of the tampons, soaked and heavy, drops from her face and splatters on the ground. Blood dots the spongy surface of the gym mat like the aftermath of an aerial bombardment.

“Do you want one of my supers?” Genevieve breaks her Kala Bhairavasana pose and passes Brooke a wad of tissues.

Brooke wipes her face and notices an older man with long baggy shorts

eyeing her expectantly. He stares at the bloody mess as if she had allowed her dog to defecate on his front lawn.

The man continues to glare as she gingerly leans over and picks up the saturated product, dropping the tampon by its long string into the garbage can. The man sniffles as she retrieves another tampon from her bag and twists it up into her nostrils. Erica has already wiped off the mat before they walk over to the treadmills together.

“You wouldn’t believe the week I’ve had,” Genevieve tells them, beginning at a brisk walk before easing them into a full-out run.

Brooke looks over at Erica and smiles smugly. The shorter brunette is short of breath and strains to keep pace. Sure, Brooke’s flexibility is subpar, but she can easily outrun both of them.

Energized, Brooke doesn’t wait for Genevieve to crank up her speed. She punches the treadmill screen with her finger, her legs hitting the conveyor belt in a faster cadence, creating an offset beat from that of her friends.

Brooke is still surprised that the three of them have somehow remained friends. Genevieve and Erica were unlikely roommates in college. Despite their differences in temperament, they had an older-sister-younger-sister kind of relationship. Brooke met Genevieve in a tedious history class, they’d missed half the semester sampling different food trucks throughout the city.

Instead of competing, Brooke is disappointed when Genevieve slows down to a jog and begins a long exposition about some terrible guy she met at a bar.

“What I want to know,” Erica interrupts her panting, “is what were you doing at a bar on a Monday?”

Genevieve hesitates before laughing off Erica’s line of questioning. “You think I’d have better luck finding men at the library?”

“About the same luck as finding a keeper here.” Brooke gestures to the out-of-shape middle-aged men they are surrounded by.

“At least when you’re on the flow, they stare, but never approach.” Erica gives up trying to keep up with Brooke and hops off the treadmill while the belt continues to cycle around.

“I guess we’re done running?” Brooke throws her hands up. “That was only a mile.” Genevieve delicately touches her nose, signaling to Brooke that once again she’s about to spring a leak. Brooke is forced to stop and repack her nostrils.

They reconvene by the free weights where a pubescent teen is struggling on the bench press. He sees the women approach and retreats to a machine further away.

“Bar hopping on Mondays is a sign of desperation.” Erica lectures Genevieve. “John promised me he’d set you up with a nice guy at his firm.”

Brooke watches as Genevieve walks over and chooses a lighter set of weights. In general, she doesn’t let Erica’s moods get to her, but it’s obvious she’s on edge.

“And when’s the last time you partied?” Brooke hands Erica a pair of twenty-pounders. Erica grunts a little as her arms are weighed down, but doesn’t put them back.

“Just because you weren’t invited, doesn’t mean parties don’t happen. John and I went to dinner with a couple of friends last week.”

Brooke laughs, “Going out with your husband’s work associates doesn’t count.”

They begin their routine with three sets of overhead presses. Brooke’s nose is itching, but she refuses to scratch it, unwilling to risk another mess. They are almost done with the workout when Genevieve’s hand slips. She drops a weight, narrowly missing Brooke’s foot.

“What the hell is wrong with you today?” Brooke demands, retrieving the errant dumbbell and replacing it on the rack. It’s unlike their usually graceful friend to be so careless.

Genevieve retreats to a nearby bench without a word and plops herself down. She leans forward, face sinking into her hands.

“Sorry, I lashed out.” Brooke places an arm around her shaking friend. Genevieve’s skin feels cold and clammy despite the difficult workout.

“I thought you were maybe a little hungover, but that’s not it.”

“It’s obvious.” Erica interrupts.

“She’s late.”

Genevieve responds by crumpling in on herself again, bending at the waist until her head rests on her knees.

“Is that it?” Brooke asks, passing her a Kleenex. Genevieve gives the smallest of nods and blows clear mucus into the tissue before discarding it.

“I’ve got lunch with my boss in an hour, she’ll know I’m late as easily as Erica did.”

Brooke looks at her friend and worries. The government couldn’t force you to get pregnant, but if you did, there was no getting out of it. Genevieve could easily lose her job, or at the very least be humiliated into taking a test.

She feels her blood stretching her veins, putting pressure on all the tiny capillaries. Brooke imagines a world where menstruation is a private affair. She could think of more efficient places for the blood to flow out of.

Brooke understands she can’t fix this for Genevieve, but she can buy her time. She looks over at Erica, whose eyes dart towards the ladies’ room. As far as they’re aware, there are no cameras in the restroom. She leads

Genevieve to the bathroom, which is abandoned except for the two of them. Erica remains just outside the door, appearing to scroll through her phone.

They stand over the sink, and Brooke helps Genevieve dab the smeared mascara until her face is clear.

“You don’t have to decide what to do today,” Brooke tells her. “It might be a false alarm.”

Genevieve nods, takes a deep breath, and straightens her shoulders. She almost looks like she’s about to begin a meditation. Brooke’s heart pounds erratically, and she tries to relax by mirroring her friend’s composure. She envisions the version of Genevieve who twists and bends in almost impossible ways without so much as pulling a muscle.

She commits herself with a grimace, and then, without warning, smashes her knuckles into her friend’s perfect nose. Brooke can hear and feel the bone popping, but to her surprise, Genevieve does not cry out in pain. Blood pours onto her friend’s tank top, creating a macabre tie-dye effect. This is not the ooze of menstrual blood, but the gush of flood waters.