THE MAGAZINE OF THE SKIRBALL CULTURAL CENTER 2022

The Skirball Cultural Center is a place of meeting guided by the Jewish tradition of welcoming the stranger and inspired by the American democratic ideals of freedom and equality. We welcome people of all communities and generations to participate in cultural experiences that celebrate discovery and hope, foster human connections, and call upon us to help build a more just society.

Phil de Toledo, chair

Jessie Kornberg, president and ceo

Art Bilger, vice chair and treasurer

Jay Wintrob, vice chair

Cindy Ruby, secretary

Howard M. Bernstein

Giselle Fernandez

Melvin Gagerman

Marc H. Gamsin

Jeffrey Glassman

Marcie Goldstein

Emiliana Guereca-Zeidenfeld

Dana Guerin

Uri D. Herscher, founder

Mitchell A. Kamin

Robert C. Kopple

Lee Ramer

Kenneth A. Ruby

Peter M. Weil, past chair

Susan Hirsch Wohl

D. Zeke Zeidler

Marvin Zeidler

John Ziffren

Skirball Cultural Center

2701 N. Sepulveda Blvd.

Los Angeles, CA 90049

(310) 440-4500

skirball.org

Hal BanfieldJocelyn

“Always have a mentor in their 20s.” Those were the words of my cousin Sonia, then in her 80s, explaining how she maintained her energy and activity. Sonia’s flipping of the traditional interpretation of l’dor v’dor (from generation to generation) was often heard as light-hearted, but was, in fact, deeply powerful. Learning and guidance are rarely best when imagined as one-way relationships. Rather, new perspectives and great insight can come from all directions, including from those much much younger than us. This particular brilliance is front of mind as I reflect on the moments that brought us the most joy at the Skirball this past year.

In the museum’s much-anticipated exhibition on Jewish delis, we heard story after story of favorite meals shared with parents and grandparents. While hosting the Citizen University’s Civic Collaboratory, we beamed as high school students shared how they are building mutual aid projects in communities everywhere from rural Ohio to Atlanta, Georgia. During the inaugural Friedman Prize presentation, we all nodded in understanding as the awardwinning scholar Max Daniel recounted the experience of talking to his father, a Greek refugee from the Holocaust, about other immigrant journeys.

Over and over again, the moment of new learning, the spark of recognition, or the joy of discovery has come through an exchange between generations. Not only is this in keeping with the Skirball’s essential Jewish value to honor memory, it has also felt precious and rare

at a time when intergenerational exchanges seem increasingly brittle. Why might these exchanges flourish here even as they whither elsewhere? The Skirball is, indeed, an oasis. A place of peace and welcome. A place where you can feel safe to experiment and falter. A place of unexpected learning and connection.

As I read this year’s Oasis Magazine, I find enjoyment in discovering new perspectives from surprising sources. And I feel overwhelmed with gratitude for the community who helped to create and sustain these experiences at this place.

Thank you for being part of that community, President and CEO Skirball

Cultural Center

Cultural Center

Skirball’s exhibition on Jewish delicatessens whets the appetite for learning about the endurance of the nation’s most nostalgic cuisine.

More than a place to get a meal, the Jewish deli is a community forged in food. In May 2022, the Skirball opened its original exhibition “I’ll Have What She’s Having”: The Jewish Deli, organized largely with objects drawn from the Skirball Museum’s own permanent collection. Now touring museums around the country, the exhibition explores how Jewish delis continue to reflect their century-old roots in Ashkenazi Jewish immigrant experiences even as they evolve to fit the needs and tastes of new generations.

Just as delis themselves became so much more than the food they served, the exhibition has come to serve as a collection point for thousands of memories of family and food. Waitstaff and customers become like extended family—knowing each other’s habits and preferences, creating special rituals of joy and care. Kaye Coleman, a Nate ‘n Al’s waitress featured in the exhibition, was known for many things—among them, being TV and radio host Larry King’s favorite waitress. One visitor remembered:

sound bites

The Jewish Deli begins with extraordinary archival footage, shot on an early Edison camera, on a street in the Lower East Side of New York City in 1900. Like so many American immigrant communities before and after, Ashkenazi Jews coming from Central and Eastern Europe during this period bought and sold life’s necessities in the street. This footage captures the commerce

Bottom

in action: push carts line the sidewalks, the streets are busy with pedestrians and horse-drawn carriages, and policemen walk towards the camera, swinging their batons, and forcing the street vendors to move. From those carts and barrels, and from new Jewish immigrants’ demand for kosher food, was born Jewish deli cuisine. Think of your favorite order at the deli. What is the taste? Salty? Sweet? Pickled? Cured? These are the tastes of safely preserving food in the street, without access to refrigeration.

“My parents and I used to always go to Nate ‘n Al’s for breakfast and Larry King would be there. One of the waitresses would always greet us and bring me a bagel necklace—a bagel on a piece of string. I was a small kid back then and it felt like the greatest gift in the world, munching on my bagel necklace while waiting for our order.”Facing page: Visitors pose with their favorite deli menu selections at the entrance to the exhibition. Left: Skirball visitors viewed original deli signs, menus, uniforms, and cash registers. right: The Valley Relics Museum loaned the spectacular ten-foot-tall neon sign from the shuttered Drexler’s deli in North Hollywood. The Skirball’s engineers rebuilt components of the sign so that it could be turned back on, not just for the run of the exhibition at the Skirball but also once it returned home. Morgan Foitle Lindsey Best

( serves 12 )

Judy Zeidler was a beloved member of the Skirball community from its inception until her death in October 2022. In Jewish tradition, we say of those we’ve lost, “may her memory be for a blessing,” meaning may those who remember her keep her goodness alive. This recipe is from her much-loved International Deli Cookbook. We hope it will continue to bring you joy and warmth, along with the sweet doodle below, left in The Jewish Deli exhibit by a Skirball visitor.

CHICKEN BROTH

One 5-pound chicken, or two 3-pound chickens, trussed

1 pound chicken necks and gizzards

3 medium onions, diced

1 medium leek, sliced into 1-inch pieces

3 to 4 quarts water

16 small carrots, cut into 1-inch pieces

5 stalks celery with tops, cut into 1-inch pieces

3 medium parsnips, sliced

8 sprigs fresh parsley

Salt and pepper, to taste

In a large heavy Dutch oven or pot, place chicken, necks, gizzards, onions, leeks, and water to cover. Over high heat, bring to a boil. Using a large spoon, skim off the scum that rises to the top. Add carrots, celery, parsnips, and parsley. Cover, leaving the lid ajar, reduce heat to low, and simmer for 1 hour. Season with salt and pepper to taste. Uncover and simmer for 30 minutes. Add water if needed.

With slotted spoon, remove chicken from soup. Let cool to room temperature then chill. Skim off the fat that hardens on the surface. Meanwhile, prepare the matzo balls.

Bring soup to a slow boil and gently drop in matzoh balls. Cover, reduce heat to low, and simmer about 10 minutes (do not uncover during this cooking time). Ladle into heated soup bowls.

THE FLUFFIEST MATZO BALLS

3 eggs, separated

About 1/2 cup water or chicken stock

1 to 1-1/2 cups matzo meal

1/8 tsp salt

Pinch fresh ground pepper

Place egg yolks in a measuring cup and add enough water or stock to fill 1 cup. Beat with a fork until well blended. Set aside.

In a large bowl, using an electric mixer, beat egg whites until the form still peaks; do not over-beat. In a small bowl, combine matzo meal with salt and pepper. With a rubber spatula, gently fold the yolk mixture alternately with the matzo mix into beaten egg whites. Use only enough matzo to make a light, soft dough. Season with additional salt and pepper to taste. Cover and let firm for 5 minutes.

With wet hands, gently shape mixture into twelve 1-1/2 inch balls. Add to and cook in soup according to the directions.

From Oasis, the magazine of the Skirball Cultural Center, 2022. This poster was created for the Skirball Cultural Center’s 2022 exhibition, “I’ll Have What She’s Having”: The Jewish Deli.One of the delis featured in the exhibition, Canter’s Deli in Los Angeles’ Fairfax district, has served for decades as a watering hole for high school students, rock bands, and lovebirds to find sustenance and community at all hours of the day. Just as New York delis like Katz’s and Russ & Daughters started in the Jewish immigrant community of the Lower East Side, Canter’s first opened in Boyle Heights where many Jewish immigrants to Los Angeles lived a century ago. Now run by third-generation members of the Canter family, the deli is a fixture for Angelenos of all ages and cultural backgrounds who have grown up in the glow of its iconic sign.

sound bites

“Canter’s was the first restaurant my Dad took me to. Canter’s was the last restaurant where I took him—more than 60 years later. We both loved the roast tongue.”David George / Alamy Stock Photo Lindsey Best The neon sign from Billy’s Deli, a Glendale institution for 67 years until it closed in 2015, beckons visitors to the deli and popculture portion of the exhibition.

sound bites

“We’re Mexican. My sister is Jewish, believe it or not, and I have a Vietnamese brother-in-law. We’re regulars here. We come to enjoy each other’s company and also the food; they really put their love into it. We’re 24 in my family—we fill up the table in the back.”

Canter’s is one of many multi-generational deli stories on view in The Jewish Deli. Shapiro’s in Indianapolis, began as a horse drawn cart, selling dry goods at the turn of the 19th century. By 1930 it had grown into a brick-and-mortar establishment selling from a towering display of cured kosher meats. Today it continues to sell many of those signature cold cuts but sometimes with a slice of cheese—the hallmark of a deli rooted in Jewish traditions, but now catering to a much broader clientele. For deli lovers, the cuisine is a way to feel a sense of belonging from generation to generation, even as Jewish life in the United States continues to change.

sound bites

Grocers in Odesa, Ukraine for over 100 years, the Shapiro family fled to Indianapolis in 1905 when antisemitic pogroms destroyed their store. Upon arriving in the United States, they opened a pushcart that sold flour and sugar. By 1940, they had opened their first Shapiro’s Cafe, where Abe Shapiro’s famous corned beef was a perennial draw. Today, after two centuries of serving kosher fare, Shapiro’s Delicatessen is run by the fourth generation of the family born in the United States.

“The guy making the matzoh balls, he’s Mexican, Rigo. He makes a matzoh ball you would not believe. Anyone shows up hungry, we feed them a sandwich.”

“I am a second generation American of Bohemian descent. I welcome you to America. I hope you find a place where you can patch together your traditions and history with a new and fruitful life.” — catherine c.

“My ancestors came to these shores over 300 years ago. Many years from now, your descendants, too, will tell the story of how you thrived.” — valerie c.

“My grandparents met at a Japanese internment camp. My father was born in a camp in Colorado. Even in times of despair my Grandpa loved the United States and named my dad Jefferson–after Thomas Jefferson.” — janice a. o.

An installation of hundreds of homemade blankets transforms the Ruby Commons into a space for community connection, mutual aid, and shared experience. The kaleidoscope of color, fabric, and memory connects the Skirball to a national network of refugee resettlement partners.

Since 2015, artist and activist Jayna Zweiman has been collecting hand-crafted blankets and donating them, along with personal notes from the crafters who make them, to thirty resettlement agencies working with United States Customs and Immigration Services to safely integrate immigrant families into new homes. More than six thousand people have contributed blankets to the effort—makers and Americans of every imaginable background and orientation, all connected by a single wish that everyone will find true welcome here.

“Each blanket is a gift, it should be hard to give away,” she says. By engaging the deeply personal work of creativity, fiber arts, and the maker’s own family stories, the project brings together a diverse community that uses design innovation to encourage social change and human connection.

In 2022, Skirball became the hub for the collection of the Welcome Blankets, hanging blankets throughout the campus, including in the Vote Center in Herscher Hall during the 2022 elections, hosting blanket-making workshops, and collecting hundreds of new blankets to add to the resettlement project.

Aside from traditional sewing and crochet, Welcome Blanket uses personal symbols to bring the blankets makers’ own family histories into these heirlooms. Photos of immigrant relatives dating back over a century, historic letters, logos, and iconography of faith and identity have all made their way into these personal, practical gifts. The result is a visual narrative of collaboration and perseverance.

Zweiman’s own family survived the Holocaust. Following her grandparents’ emigration to the United States, she grew up hearing stories of their experiences on two polarities: warm tales of their former lives abroad, and cold distance from what once was. It is tempting to think of the safe arrival of a family in the United States as the happy ending, but it’s also the beginning of a new story. Starting that story with a deeply personal welcome is a powerful way to create a space to discuss how the meaning of “home” can evolve.

“I see people trying to come here, and I feel a connection to my grandparents and the love I have for them,” said Zweiman. “I respect their ability to survive and rebuild while retaining their identities and connections to family.”

Love of learning is an essential value at the Skirball. It inspires school programs, adult classes, and internship opportunities for young leaders. The assistant editor of this year’s Oasis and the primary author of this Welcome Blanket feature is Annalisse Galaviz. A lifelong Los Angeles County resident, Annalisse is a recent graduate of Whittier College where she was the news editor of The Quaker Campus newspaper.

The Talmud tells a story about an old man who spent his dwindling days planting acorns. It seemed a strange vocation for someone so old: the acorns would take years to grow. Someday they would become trees, but the old man wouldn’t live to see them. Why, he was finally asked, did he devote himself to such a task? “Because,” the old man replied, “the world was not barren when I arrived here; I plant for those who come after.”

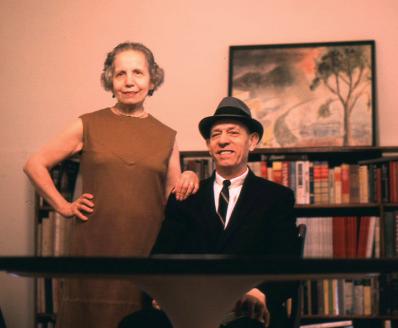

Established by the Skirball Cultural Center in 2021, in memory of the Founding Chairman of its Board of Trustees, Howard I. Friedman, The Friedman Prize supports upand-coming Jewish scholars. Graduate and postdoctoral students are invited to reflect upon themes inspired by Friedman’s and the Skirball’s shared devotion to Jewish values and American democratic ideals.

Friedman’s tenure as Chair, and much of his professional and personal life, was distinguished by an abiding commitment to Jewish heritage, anchored by a profound respect for American democracy and social pluralism. He believed that American Jews do not stand alone, that they are part of a longer history and a wider community, and that by affirming these connections they achieve their fullest potential as Jews and as Americans. These deeply held convictions helped to shape the first generation of the Skirball’s development.

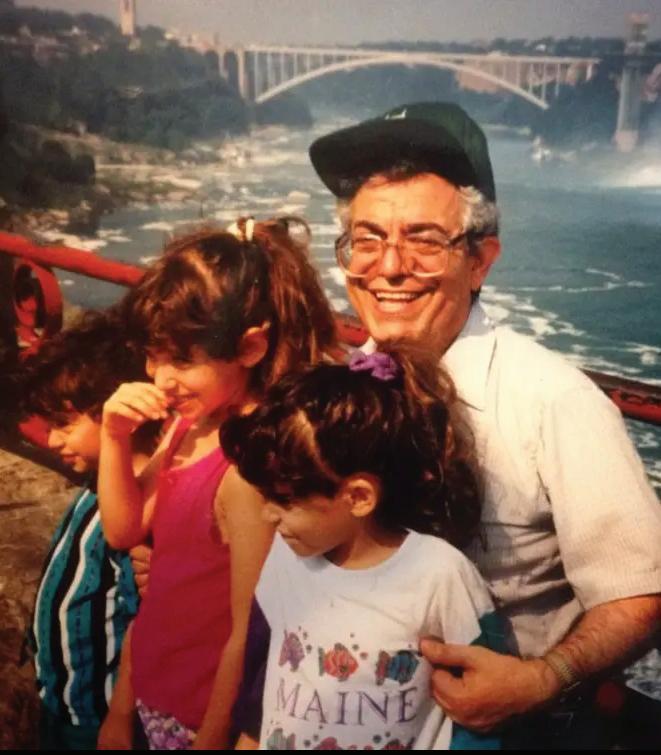

In its inaugural year, the Friedman Prize invited perspectives on a topic central to the Skirball mission: the relationship of Jewish values to American immigration experiences. The prize of $5,000 and publication in Oasis was awarded to Max Modiano Daniel for his essay, “Jews, Immigration, and the Limits of Empathy,” a copy of which you will find in the attached pull-out section. Daniel, the son of Greek Jewish immigrants, was a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of History at the University

of California, Los Angeles, when he received the Friedman Prize. We congratulate him on receiving his doctorate shortly thereafter. He also holds degrees from Columbia University and the Jewish Theological Seminary.

Beginning with his own family history, Daniel’s essay illuminates the robust and sometimes contradictory relationships between Jewish ideals and U.S. immigration policy. Drawing on classical Jewish sources, he argues that while the idealized narrative of America as the Goldene Medina (Golden Land) was a powerful inspiration for immigrant Jews of the early 20th century, it is likely to ring hollow to less fortunate immigrant communities, past and present. “Even those who see empathy with the beleaguered immigrant as a Jewish value risk erasing important differences between the two.” Daniel concludes with a call for Jews and all Americans to broaden their vision and sense of responsibility for the history and future of American immigration, in all its vitality and diversity.

At the inaugural Howard Friedman Memorial Lecture in May 2022, Daniel discussed his essay in conversation with Skirball President Jessie Kornberg. “As a young scholar,” he said, “it is empowering to receive the Skirball’s support and investment in the next generation of critical thinkers on the American Jewish experience.” We wish we wish Max Daniel success in his ongoing scholarship just as we too work to build a society more embracing of immigrant communities.

The holidays of Sukkot and Hanukkah bring favorite annual traditions to the Skirball.

Perhaps more than at any other time of year, the entire Skirball campus is full of festivities celebrating what it means to live Jewishly and visitors engaging in rituals that invite us to imagine a better future.

The celebration of Sukkot, the harvest festival, is beloved. A holiday that invites one and all to share in the bounty of Jewish life—what could be more Skirball?

Artist Gray Hong of Highland Park floral studio Moon Jar Design, erected this year’s sukkah. They began the process by asking visitors a seemingly simple question, “What brings you joy?”

Says Hong, “Joy is a powerful emotion, capable of lifting us to do great things. It is important to recognize our joy(s), to name them and to honor them...I reflect that ‘our joy’ is something different than ‘my joy.’ It is collective, shared, and felt in community with others.”

Hong wove the answers into the floral garlands that hung from the rafter of the Founder’s Courtyard, transforming the space into a sukkah and a glorious physical reflection of our selves. Architect Moshe Safdie has said of the Skirball, “you’re inside while you’re outside and you’re outside when you’re inside.” Sukkot at Skirball brought everyone in, and all our innermost feelings out. This shared abundance was again in full effect during our annual Hanukkah Festival, when generations came together to light the holiday candles. Jewish law commands those who celebrate Hanukkah to make the light of the menorah public and Skirball President Jessie Kornberg reminded us why, “When it feels like the shadows are rising to darken Jewish gathering and celebration, the strength and joy of the holiday comes not just in your own claiming of the light, but in joining your light to a community of others.”

During the Hanukkah Festival, visitors of all ages made hand-crafted torches that were used to lead visitors around the edge of the pond in the courtyard and turn on the pillars of light while families and friends danced in circles to the music of Mostly Kosher, a favorite local klezmer-rock band. And in those joyful dances, as it was with garlands hanging on Sukkot, there was no first and no last, each individual an equally vital link in the chain that strengthens our community.

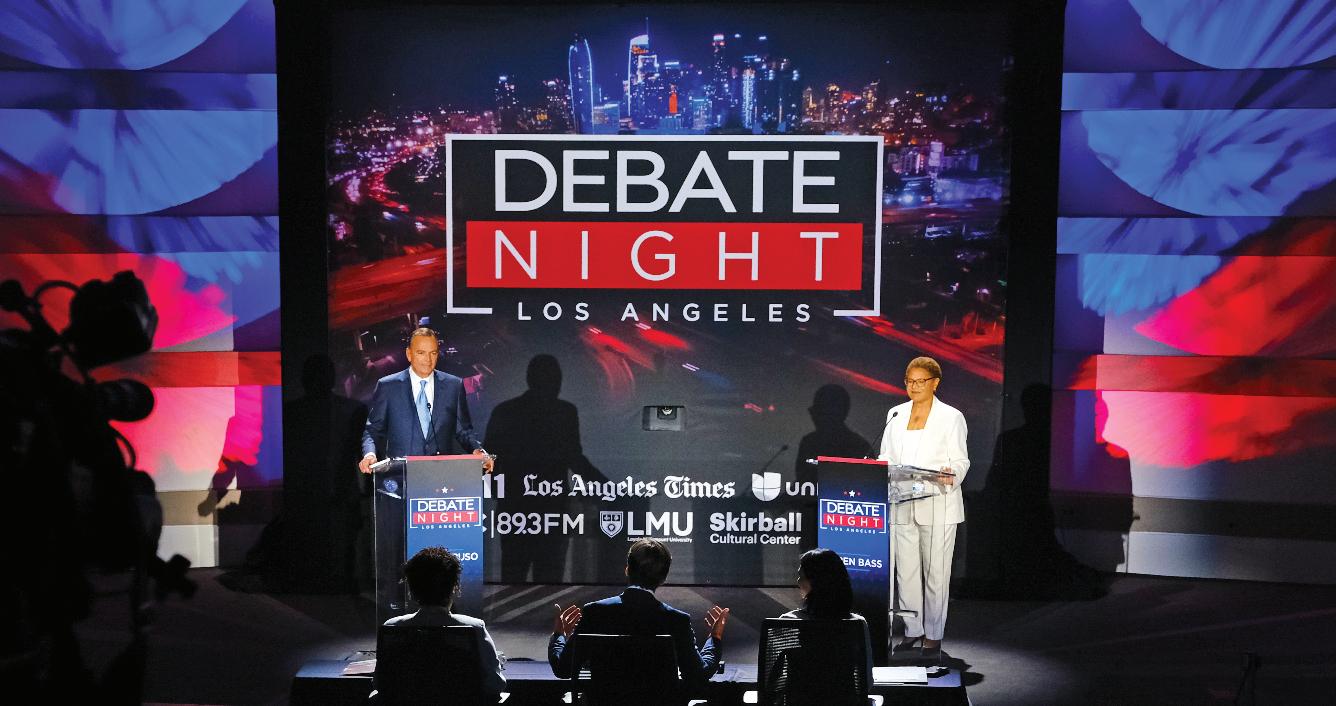

Erika D. Smith is a columnist for the Los Angeles Times writing about the diversity of people and places across California. During the 2022 election cycle she helped moderate the mayoral and sheriff’s debates at the Skirball Cultural Center. Here she shares the meaning and memory of that night.

I’M A WRITER. TV ISN’T REALLY MY THING. But one evening in late September, I found myself sitting under bright lights in the packed auditorium of the Skirball Cultural Center, anxiously waiting for about a half-dozen cameras to go live.

In that moment, I was worried about all sorts of things that didn’t matter. Not smudging the makeup that I never wear. Not rolling backwards off the makeshift platform and into a row of seats.

So I remain forever grateful for what happened next. Jessie Kornberg, President of the Skirball, walked on stage and said a few words to remind us why we were there — for a celebration of American democracy and, by extension, a sharing of Jewish culture.

Five journalists, myself included, were about to co-moderate two pivotal political debates. First, between the candidates running for Los Angeles County sheriff, Alex Villanueva and Robert Luna. And second, between the candidates running for Los Angeles mayor, Karen Bass and Rick Caruso.

It was to be the latest event in a series of them at the Skirball, all focused on the importance of voting, politics and overall civic engagement. Voter education with the League of Women Voters, an exhibition celebrating citizenship and political speech, a film series curated by a constitutional scholar, and now these debates—the series would soon culminate with actual voting at the Skirball.

The cultural center, Kornberg told us, was built to break down barriers, to open minds and to embrace differences. And indeed, as she spoke those words I recalled how that’s exactly what I had experienced.

Most people don’t know just how much preparation it takes to pull off a televised debate. Suffice it to say it’s a lot. Like a lot, a lot.

This was especially true for these debates, because there were so many news organizations and institutions involved. In addition to the Skirball, there was the Los Angeles Times, Fox 11, Univision 34, KPCC, the Los Angeles Urban League, and Loyola Marymount University.

Representatives from each had met over Zoom for weeks, trying to hammer out the logistics and basic power-sharing of the unwieldy partnership. Then some of us huddled in person for a few days, taking over a conference room at the Skirball.

Our job was to come up with questions, from the wording to order in which we’d pose them to the candidates. While we agreed that much about L.A. is broken, we quickly realized that we didn’t always share the same priorities for repairs. Like a lot of Angelenos, we had differing views on how to address homelessness, housing affordability, crime and public safety, policing, guns, climate change and economic development.

We each came from different communities, with different races and ethnicities, and with different concerns. So we argued — well, debated. We got irritated with one another, as we made our respective cases on this point or that point.

We laughed, too. We took lunch breaks in the Skirball’s courtyard, which, with that magnificent pond, I’m convinced is the most calming place in Los Angeles. Then we got back to work. We compromised. And we learned.

I thought about this on the evening of the debates when Kornberg, in her speech, joked with the audience that if they didn’t understand what’s so Jewish about a political debate, they could “join me for a family meal this weekend and see just how Jewish a political debate can be.”

I’m immensely proud of the questions we asked all four candidates and the sometimes contentious process by which we cobbled them together in that

conference room. Taken together, the questions offered a window into the needs and dreams of diverse Los Angeles.

That carries even greater importance, knowing what has happened in the months since.

First, came the leaked audio of three members of the City Council and an influential labor leader having a crass, racist conversation, pitting Latinos against Black people and Jews and framing politics in L.A. in zero-sum terms. And then the surge of antisemitism, culminating with a group of people raising their arms in Nazi salutes and hanging a hateful sign over the 405 Freeway.

Los Angeles is better than that. Or, at least, we should be. We can be.

The Skirball was built by a Holocaust survivor who, Kornberg told us, “imagined this space as one good place, for everyone.” I will always think of my time there as a reminder that, by doing the hard work of collectively participating in our diverse democracy, it’s possible to make that true for L.A. as well.

Above: Debate moderators, from right to left, Erika D. Smith (Los Angeles Times), Elex Michaelson (Fox 11), and Oswaldo Borraez (Univision 34)

Senior Scholar of Jewish Studies Robert Kirschner reflects on interactivity as the hallmark of culturally Jewish experiences at the Skirball.

A century ago, philosopher Martin Buber advanced the concept of I and Thou. Its premise is that human life is fundamentally interpersonal. Human beings are not isolated, free-floating objects, but subjects existing in relationship to one another. Our lives are defined by our interactions. No “I” is an island. As Buber put it, “Living is meeting.”

Interactivity is the signature strength of the Skirball experience. We strive to welcome our visitors warmly and engage them personally, intellectually, and emotionally. In our museum galleries, public programs, educational activities, and participatory workshops, we offer open-ended, multi-sensory, inquiry-driven learning that encourages our visitors to explore, forge connections, and build relationships. At the Skirball, we are hands-on and heartfelt. We strive to make each experience approachable, accessible, age-appropriate, and engaging to a diverse audience.

In these pages of Oasis we offer a glimpse of interactivity and creative expression at the Skirball in 2022—a vivid and joyous affirmation that living is meeting, and no “I” is an island.

In October, the Skirball hosted the Protest Banner Lending Library, a project conceived by artist and activist Aram Han Sifuentes, and brought to life by the many people who have joined the banner making workshops and whose work you see in these pictures. Once they’re made, the banners are left for anyone to come and borrow as they need. Like the welcome blankets, this work draws on the legacy of crafting traditions and immigrant labor that is commonly discounted in society. But rather than offer commentary on what it means to become an American, this project speaks to what it means to be an American and to exercise the freedom and power of expression and citizenship.

Every weekend all summer long, families come to the Skirball for a special performance series in the Zeigler Amphitheater outside Noah’s Ark. Here, children dance to the music of Las Colibrí, an all-female mariachi ensemble. Other summer performances included puppet shows and pan-African dance.

Families make amulets based on Gabrielino/Tongva stonework with artist and teacher Lazaro Arvizu. Throughout the month of October, families took part in archeological digs and engaged in hands-on learning about the history and Native traditions of California.

School tours to Noah’s Ark are an opportunity to engage the curiosity of young learners for storytelling and science. In the storm gallery visitors create wind, thunder, lightning, and rain before they help animal friends in distress board the ark.

Teaching Through Storytelling workshops introduced classroom teachers to Skirball’s values-based curricula and to arts-integration teaching techniques that engage students across subject areas while fostering social and emotional competencies, creative problemsolving, and collaboration.

In the South Arroyo outside Noah’s Ark, children answer the question, “How would you make the world better?” They write their answers on small wooden discs and leave them for the next garden visitor to find and consider. It was one of the many art projects done throughout the year based on Skirball exhibitions, Jewish traditions, and the importance of caring for the world.

To celebrate the addition of artist Tobi Kahn’s ZAHRYZ Tzedek Box to the museum’s collection of Judaic treasures, visitors leave notes inside sharing small acts of kindness. (Photo credit: Bill Massey)

The launch of the UCLA Center for Justice and release of Rebel Speak: A Justice Movement Mixtape were celebrated at the Skirball with the performance of Lyrics from Lockdown, followed by a conversation between author Bryonn Bain and legendary community organizer Dolores Huerta. The For Freedoms artist collective installed Another Justice: By Any Media Necessary in the entrance to Herscher Hall especially for the evening’s gathering, showcasing the art of women incarcerated at Victorville Federal Prison. Through music, visual art, and spoken word performance visitors participated in lively and thought-provoking interactions.

In August as part of the triumphant return of Korean pop-folk band ADG7 to the Skirball’s Sunset Concerts, the Korean Cultural Center Los Angeles partnered with the Skirball to bring together an unforgettable mix of music, food, dance, ritual, art, and community. The visitors engaged in activities such as learning to write their names in the Korean alphabet and trying on hanbok, traditional Korean clothing.

The Skirball’s commitment to honor memory and bring diverse audiences together was at its most jubilant during our 25th season of Sunset Concerts. No one could resist jumping up and dancing to bands like Son Rompe Pera, brothers who blend the traditional marimba sounds they learned at their father’s knee with the punk sounds that spoke to them. No one could resist smiling when lead singer Doni Zasloff’s newborn joined Nefesh Mountain on stage.

The summer culminated in a sold-out night with R&B icon Booker T. Jones. Joined on stage by his son Ted Jones and the Doors’ guitarist Robby Krieger, Jones brought new life to Green Onions and the history of the first integrated rock band at Staxx Records to a whole new generation. Without fail, these concerts gave us new melodies for our age-old calls for liberation and unity. And with them, our voices and bodies rose in hope.

Above: Booker T. Jones and his son Ted Jones brought the sold-out crowd to their feet.

Far left: In July, Mamek Khadem performed the Sufi music of Iran, past and present.

Above: Booker T. Jones and his son Ted Jones brought the sold-out crowd to their feet.

Far left: In July, Mamek Khadem performed the Sufi music of Iran, past and present.

skirball.org

IN LATE 1954 MY FATHER BOARDED AN OCEAN LINER AT THE PORT OF PIRAEUS, GREECE, together with his parents and two younger siblings. Several weeks later they arrived at New York Harbor en route to their final destination, Chicago, where my uncle had already lived for several years. It was there where most of my cousins, siblings, and I were born—the first generation in America.

More than an ocean separated them from their former home. Years of war, famine, occupation, and civil strife had torn through Greece. Few other groups were as impacted as its Jews. Only 10-15% of the country’s prewar Jewish population survived. Seeing no future for Jewish life in a place where the Holocaust was still a fresh wound, my family looked toward America to rebuild.

A commitment to Jewish community and a desire to emigrate were scarcely enough for those who had lost so much. Alongside the passage of the Refugee Relief Act of 1953 that enabled them to migrate to the United States, my family received financial, educational, material, and occupational assistance from Jewish organizations like HIAS (Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society) and the JDC (Joint Distribution Committee), together with local Jewish federations in Greece and Chicago. Among Holocaust survivors and refugees, they were very fortunate.

Family, community, continuity, resilience, aiding the needy, welcoming the stranger—all of these Jewish values shaped my family’s immigration experience. Many other immigrants, Jewish and otherwise, have had their migratory paths shaped by benevolent actors and efforts inspired by similar principles. They were welcomed, taken in, supported, and given opportunities to flourish in their new homes, overcoming many hurdles on their path to America. It is reassuring when the story of American immigration and Jewish values aligns so neatly. These ideals are perhaps nowhere more evident than on the base of the Statue of Liberty, where verses from “The New Colossus” by Emma Lazarus are inscribed. “Huddled masses yearning to breathe free” has become synonymous with the benevolent narrative of America’s attitude toward immigrants, and Jews are always eager to claim the poem’s author, Emma Lazarus, as one of their own.

Indeed, the values of welcoming the migrant, traveler, and stranger are deeply embedded in Jewish tradition, ritual, and history. Before “Jew” or “Israelite” became identifiers, the Torah describes the patriarch Abraham as ha‘ivri, “Hebrew,” a term thought to mean “migrant” or “one who crosses,” referring to the journey from Ur to Canaan. Abraham’s life story advances this theme, describing his subsequent departure to Egypt to seek relief from famine. (Today we might call him a climate change refugee.) The root of the Jewish value of hospitality comes from the Torah story of the three visiting angels who stopped at Abraham and Sarah’s tent. The gracious welcome they received has served as a key lesson and precedent in the Jewish ethical tradition.

From the inception of the Jewish people, migration has been central and foundational, as has the imperative of kindness to travelers and guests. The fall festival of Sukkot commands Jews to build tent-like structures in commemoration of the Israelites’ desert camps. The spring festival of Passover asks them to imagine themselves as slaves fleeing Egypt. Migration and refugee narratives are formative contributors to Jewish identity, emphasizing the value of radical empathy. Jews are to put themselves in the shoes of past exiles in order to understand present ones. This value is codified as a commandment throughout the Torah and rabbinic literature. The classical example is found in Exodus 22:20: “You shall not wrong or oppress a stranger, for you were strangers in the land of Egypt.”

Especially as formulated by Reform Judaism, creation in the image of God (b’tzelem elohim) implies the principle of universal human equality. Jews are exhorted to pursue justice and repair the world (tikkun olam) not only for their own benefit, but for the benefit of all. In keeping with modern Enlightenment and social reform ideologies, interpretations of Jewish values have come to reflect the reality of an integrated and emancipated Jewish public no longer comfortable grounding its ethics exclusively on God-given commandments or a unique historical destiny that risks alienating non-Jews.

Major American Jewish organizations like the Anti-Defamation League, the American Jewish Committee, and the American Jewish Congress have been particularly active in various immigration and civil rights reform efforts. Religious, historical, and universal Jewish values lay behind political and social initiatives to treat the stranger and foreigner well. One example can be found in a 1958 essay by a young U.S. Senator from Massachusetts, John F. Kennedy. His A Nation of Immigrants, posthumously updated and reissued as a book in 1964, was first commissioned by the Anti-Defamation League to help counter xenophobia and advocate for immigration reform. By defining the United States in this expansive way, Kennedy sought to shape an all-inclusive conception of a nation that would embrace, rather than minimize, its residents’ diverse origins.

American Jewish advocacy on immigration issues was prominent throughout the 20th century: petitioning President Theodore Roosevelt to protect refugees from Tsarist Russia in the early 1900s; facilitating the departure of Jews from Nazi Germany in the 1930s; helping to pass the Displaced Persons Act in 1948; and marching in Washington, D.C. on behalf of Soviet refuseniks in the 1970s and 80s. American Jews often explained to the (nonJewish) public that they were acting upon “Judeo-Christian” universal values meant to cast racism and other types of discrimination as un-American. Jewish leaders also hoped such activism would help to discourage antisemitism. Jewish commitments to such objectives have been rooted in centuries-long practices. Redeeming the captive (pidyon shevuyim) has been a consistent pillar of Jewish communal ethics since antiquity, often taking the form of raising funds to rescue Jews from captors or persecutors. Medieval rabbinic commentator Maimonides saw this commandment as paramount, and its longstanding emphasis among Jews likely influenced the wide communal appeal of immigration advocates in our own times.

Especially after the fall of the Soviet Union and the arrival of thousands of Russian-speaking Jews, the primary goals of Jewish immigration advocacy were largely accomplished (not to discount the many immigrant Jews

who continue to rely on such services). Organizations like HIAS have since pivoted toward providing immigrant aid for other communities, and grassroots activists like those behind Never Again Action in 2019 have united Jews in protest against the U.S. Department of Homeland Security’s Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE)’s treatment of Latin American migrants in their custody. Many American Jews active in these efforts draw on their understanding of Jewish history and values of social justice—immediately obvious in the name of Never Again Action, an explicit reference to Holocaust remembrance.

Since the multicultural turn in American life around the late 1960s and its fitful embrace of explicit expressions of ethnic and racial pride, Jews have become more willing to publicly claim their identity as an ethical and moral compass. Earlier generations of American Jews feared anti-Semitic backlash in response to outspoken displays of Jewishness, preferring to work in smaller, less visible settings rather than staging large demonstrations. Tragically, this fear was reawakened in October 2018, when eleven Jews were murdered at Pittsburgh’s Tree of Life synagogue. Claiming Jews were responsible for a national influx of dangerous “invaders,” the gunman targeted the congregation, which had recently participated in HIAS’s National Refugee Sabbath. Yet in spite of this tragedy, there are no indications that Jews have become less public or vocal in their immigration-related advocacy. If anything, it has only increased.

Yet for all the light given off by Lady Liberty’s beacon and its message of promise and shelter, it nonetheless casts a shadow. The poetic summons to the “huddled masses” delivers a patronizing message that assumes inferiority and expects eternal gratitude, an all-too-common refrain directed against immigrants. As the deadly Triangle Shirtwaist Fire of 1911 suggests, newly arrived immigrants living and working in dangerous industrial conditions could only find the promise of “breathing free” to be morbidly ironic.

In fact, the experience of immigration in America, whether Anglos and Scots in the 18th century, Germans, Irish, Jews, and Italians in the 19th century, or Guatemalan, Vietnamese, and Nigerians in the 20th century, has been far from universally positive. In contrast to the benign nature of my own family’s story, others have experienced the break-up of families and communities, culture shock, depression and despair, isolation and exclusion. Even among immigrant Jews, there were those who cursed the day they arrived in America, often with the Yiddish expression a klug tsu Columbus (a curse on Columbus).

Many other Americans, albeit for very different reasons, have had ample reason to curse Columbus as well. Those absent from the idealized narrative of John F. Kennedy’s “nation of immigrants” have tended to be its most victimized. An understanding of American immigration must surely include the trafficking and enslavement of Africans, the expulsions of Native Americans, transitory migrants, displaced people, and the annexations of territories from the Philippines to Puerto Rico. While African Americans and Native Americans are not typically considered immigrants, their experiences have for too long been denied, dismissed, or discounted in dominant American immigration histories.

More recent scholars have foregrounded Black and Native perspectives, showing that the history of American immigration has been decisively shaped by questions of who were deemed fit to do certain kinds of work, who were

eligible to become fully-fledged members of American society, and who were to be marginalized or excluded. One of the first major federal immigration laws was the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, while subsequent immigration regulations similarly focused on race and ethnicity. Jews were not always welcome either; several eugenicist and white supremacist writers and Congressmen helped enshrine anti-immigrant and anti-Jewish attitudes into immigration law as part of the restrictive national origin quota system passed in the 1920s. Race, color, nationality, able-bodied-ness, sexuality, and gender determined immigrants’ fates as well.

Few modern Jews would claim values of bigotry or xenophobia. Those whose attitudes might tend in these directions typically cite the importance of Jewish peoplehood, continuity, safety, or chosenness. None of these justifications inherently lend themselves to xenophobic or anti-immigrant interpretations, but neither do they necessarily translate into their opposite—even if we may think the passage from Exodus 22:20 is unambiguously in favor of welcoming immigrants. Those who would claim to believe in the extension of such values to American immigration might still direct microaggressions at immigrants, undocumented people, or those who appear “foreign.” Not all Jews have been immune from anti-immigrant attitudes toward other Jews, even while believing in their right to immigrate—whether they were Bavarian Jews looking down at Yiddish-speaking “greenhorns,” Ashkenazim doubting and dismissing the Jewishness of Sephardim, or fourth-generation American Jews complaining about their newly-arrived Persian Jewish neighbors. Indeed, in the case of my own family, American Jewish social service workers were skeptical that they were Holocaust survivors at all, since they spoke Ladino but not Yiddish. These disjunctures in the standard, exceptionalist narrative of America as the goldene medina (golden land) reveal a not-so-new but timely reminder that Jewish values, often based on the radical empathy drawn from their history, can risk occluding the experiences of others. The story of American meritocracy, upward social mobility, and the “bootstraps” myth often used by successful immigrants and their descendants obscure the effects of systemic inequality and other barriers to success on those less fortunate. Struggle and failure are seen as evidence of a lack of responsibility and initiative—reinforcing and perpetuating racist tropes and stereotypes. Even those who see historically grounded empathy with the beleaguered immigrant as a Jewish value risk erasing important differences between the two. In the process, Jewish values are reduced to vague, universal platitudes recited when convenient.

I began this essay by citing my family’s immigration story. It is, by and large, a happy one. I do not advocate a complete disconnect between Jewish values and American immigration history. But I do propose that we broaden our vision of what constitutes that history, and the responsibilities it imposes upon us. My own family’s experiences have led me to a deeper understanding, appreciation, and embrace of Jewish values, and a continuing commitment to building a community where every stranger finds welcome.

From Oasis, the magazine of the Skirball Cultural Center, 2022.