Review

SchoolGardeningandHealthandWell-BeingofSchool-Aged Children:ARealistSynthesis

TimothyP.Holloway 1,LisaDalton 1,RogerHughes 2,SisithaJayasinghe 1 ,KiraA.E.Patterson 3 , SandraMurray 1 ,RobertSoward 1,NualaM.Byrne 1,AndrewP.Hills 1 andKiranD.K.Ahuja 1,4,*

1 SchoolofHealthSciences,CollegeofHealthandMedicine,UniversityofTasmania, Launceston,TAS7250,Australia

2 SchoolofHealthSciences,SwinburneUniversityofTechnology,Melbourne,VIC3122,Australia

3 SchoolofEducation,CollegeofArts,LawandEducation,UniversityofTasmania, Launceston,TAS7250,Australia

4 NutritionSocietyofAustralia,CrowsNest,NSW1585,Australia

* Correspondence:kiran.ahuja@utas.edu.au

Citation: Holloway,T.P.;Dalton,L.; Hughes,R.;Jayasinghe,S.;Patterson, K.A.E.;Murray,S.;Soward,R.;Byrne, N.M.;Hills,A.P.;Ahuja,K.D.K.

SchoolGardeningandHealthand Well-BeingofSchool-AgedChildren: ARealistSynthesis. Nutrients 2023, 15,1190. https://doi.org/10.3390/ nu15051190

AcademicEditor:JosepA.Tur

Received:24January2023

Revised:20February2023

Accepted:23February2023

Published:27February2023

Abstract: Schoolenvironmentscancreatehealthysettingstofosterchildren’shealthandwell-being. Schoolgardeningisgainingpopularityasaninterventionforhealthiereatingandincreasedphysical activity.Weusedasystematicrealistapproachtoinvestigatehowschoolgardensimprovehealth andwell-beingoutcomesforschool-agedchildren,why,andinwhatcircumstances.Thecontextand mechanismsofthespecificschoolgardeninginterventions(n =24)leadingtopositivehealthand well-beingoutcomesforschool-agedchildrenwereassessed.Theimpetusofmanyinterventions wastoincreasefruitandvegetableintakeandaddressthepreventionofchildhoodobesity.Most interventionswereconductedatprimaryschoolswithparticipatingchildreninGrades2through6. Typesofpositiveoutcomesincludedincreasedfruitandvegetableconsumption,dietaryfiberand vitaminsAandC,improvedbodymassindex,andimprovedwell-beingofchildren.Keymechanisms includedembeddingnutrition-basedandgarden-basededucationinthecurriculum;experiential learningopportunities;familyengagementandparticipation;authorityfigureengagement;cultural context;useofmulti-prongapproaches;andreinforcementofactivitiesduringimplementation.This reviewshowsthatacombinationofmechanismsworksmutuallythroughschoolgardeningprograms leadingtoimprovedhealthandwell-beingoutcomesforschool-agedchildren.

Keywords: communitygardens;schoolgardens;childhoodeducation;experientiallearning;nutrition; foodsecurity;childhoodobesity;realistevaluation

1.Introduction

Copyright: ©2023bytheauthors. LicenseeMDPI,Basel,Switzerland. Thisarticleisanopenaccessarticle distributedunderthetermsand conditionsoftheCreativeCommons

Attribution(CCBY)license(https:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by/ 4.0/).

Accesstoandconsumptionofhealthy,nutritiousfoodplaysacruciallyimportantrole inmaintaininggoodhealthandwell-beingandisafundamentalhumanright[1,2].For manypopulationsworldwide,however,deep-rootedandcomplexunderlyingproblems associatedwithfoodsystemsinfluencetheavailabilityandaccesstohealthydietsand nutritiousfood[2].Foodsecurityexistswhenallpeople,atalltimes,havephysical,social, andeconomicaccesstosufficient,safe,andnutritiousfoodthatmeetsboththeirdietary needsandfoodpreferencesforanactiveandhealthylife[3].Unfortunately,theseconditions remainelusiveformany[4],andinsomeinstances,thisleadstofoodinsecurity.According totheFoodandAgricultureOrganizationoftheUnitedNations(FAO),theabilitytobe foodsecurelargelydependsontheuninterruptedsupplyandavailabilityofdifferent typesofhealthyfood,foodutilization,andthestabilityofeachofthesedimensionsover time[3].Additionally,arangeofsocialdeterminantsunderpinstheinequitiesinhealthy eating[5].Forexample,‘urbanpoverty’,resultingfromlowerincomeavailability,may leadtoinadequateresourcesforpeopleaffectedbysuchcircumstancesinaccessinghealthy

diets,includingfreshfruitandvegetables,andinsteadtendtoconsumehigherquantities ofsugars,fats,highlyprocessed,and/orenergydense,ultra-processedfoods[6].

Globalurbanizationandaccompanyingdetachmentfromtraditionalagriculturalpracticeshaveaccentuatedthedeclineinaccesstohealthyfood,includingfruitandvegetables, andbyextension,theassociatednutritionalbenefits[7,8].Thesedynamicsarefurther complicatedbythespeedoftransitiontourbanlivingandasimultaneousdeclineforsome populationgroupsinunderstandinghealthyfoodproductionandconsumption[7,8].As aresult,aplethoraofpublichealthinterventionsaregearedtowardsincreasingaccessto healthy,nutritiousfood.Communitygardens,aspacemanagedcollectivelybycommunity membersforgrowingfoodandnon-edibleplants[7–9],isagoodexample.

Communitygardensareusedinmanysettings,includingresidentialneighborhoods, prisons,andschools[9].Severalscoping,narrative,systematic,andmeta-analysisreviews suggestthatschool-basedgardensareparticularlyusefulinimprovingchildren’snutritionaloutcomes[10–15].Forexample,studiesreportthatchildren’sfruitandvegetable consumptionincreased[13],andtheyweremorewillingtotasteunfamiliarfoodssuchas fruitsandvegetables,cookingandfoodpreparationskillsimproved,andnutritionalknowledgeincreased[14].Further,recentevidencealsosuggestshealthoutcomeimprovements thattranscendnutritionalorfood-relatedbenefits,suchasenhancedacademiclearning, socialdevelopment,andimprovementsingeneralhealthandwell-being[10,16].Aschildhoodobesityrateshaveincreaseddramaticallyoverrecentdecades,schoolgardenshave specificallybeenidentifiedassettingstoengagechildreninhealthiereatingandphysical activity,withtheobjectiveofobesityprevention[15,17].

Schoolgardeningiswidelyreportedtoimprovehealthandwell-beingoutcomes [10,13–15,17,18].However,systematicreviewsreportthatquantitativeevidence forchangesinfruitandvegetableintakeislimitedandlargelybasedonself-report[10] orlimitedthroughnon-randomizedstudydesigns[13].Althoughqualitativeevidence reportsarangeofhealthandwell-beingbenefitsforschool-agedchildren,thesearerarely substantiatedbyquantitativeevidence[10].Whilemorerobuststudydesignswouldcontributetobuildingtheevidencebase,usingtheory-ledmethodsaddsvaluebyexamining causalexplanationsofhowandwhyschoolgardeninginterventionswork[10].Thisisthe basisthatwesoughttoaddressinthisrealistreview.

Theaimofthestudywastoassessthemechanismswhichleadtopositivehealthand well-beingoutcomesforschool-agedchildrenandanswertheresearchquestion,“Howdo schoolgardensimprovehealthandwell-beingoutcomesforschool-agedchildren?”

Asystematicrealistapproachwasselectedforitsvalueinmovingbeyondaninvestigationof“whatworks?”tofocuson“howorwhyaninterventionworks,forwhom,andin whatcircumstances?”[19].Programtheoryguidestheconductofsuchsystematicreviews, whereinreviewersseektounderstandcomplexinterventions[20–22].

2.MaterialsandMethods

2.1.Overview

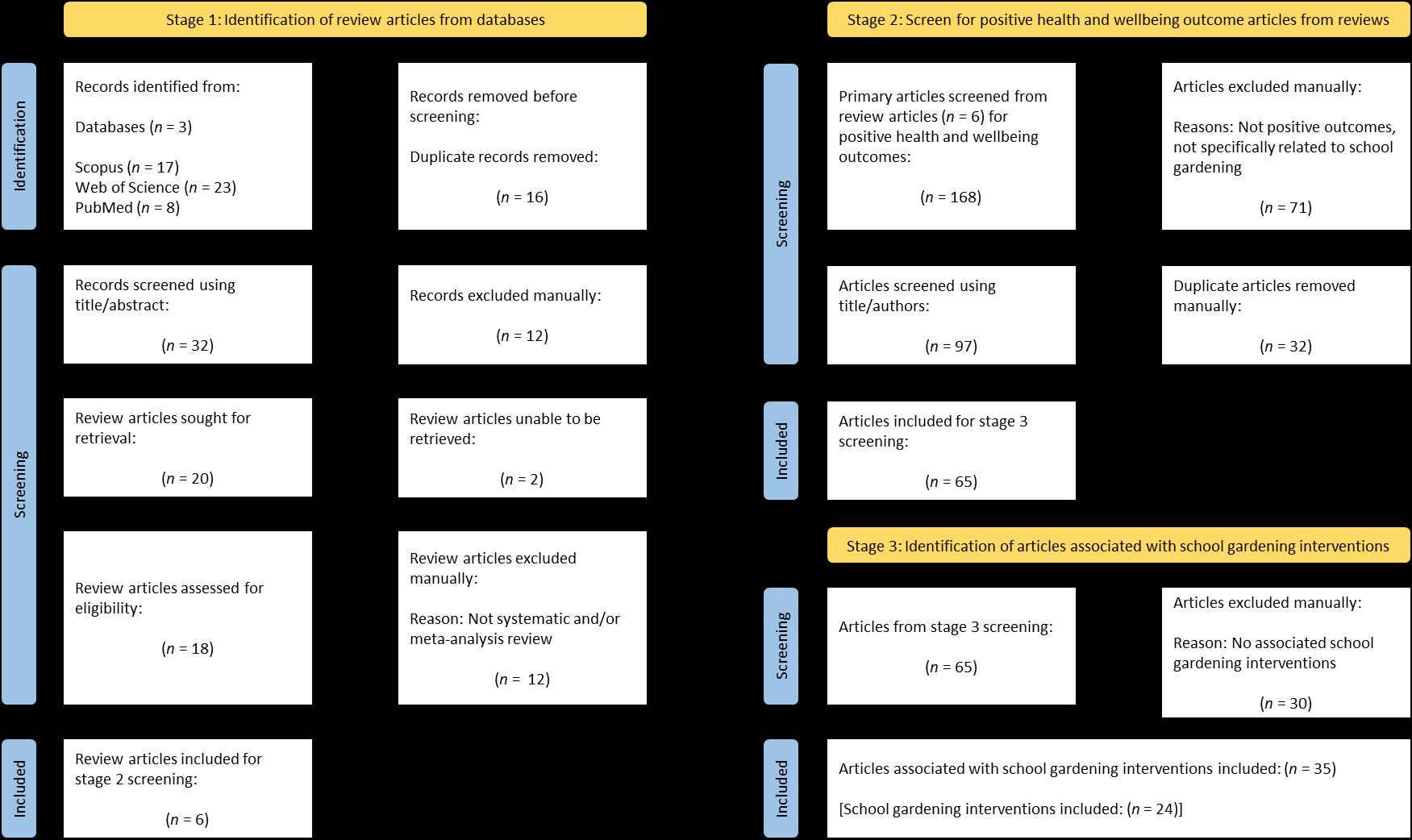

Usingathree-stagedapproach,therealistsynthesiswasusedastheguidingmethodologytoanalyzearticlesreportingschoolgardeninginterventionswithpositiveoutcomes.

Thestageswereto(1)identifyrelevantsystematic,andmeta-analysisreviewarticles, (2)screentheStage1reviewstoextractprimarysourcearticlesreportingpositivehealthand well-beingoutcomes, and(3)usetheprimarysourcearticles(fromStage2)toidentifyspecific schoolgardeninginterventionsthatrobustlyevidencehealthandwell-beingoutcomes.

2.2.SearchingtheLiteratureandDefiningEligibilityCriteria

Threedatabases(Scopus,WebofScience,PubMed)weresystematicallysearched usingtheterm,“schoolgarden*”,whichensuredbroadcoverageofthereviewarticles (Stage1).Inclusioncriteriacomprisedpeer-reviewedreviewarticlesonly,published between2012–2021inclusive,andinEnglishonly.Exclusioncriteriawereappliedto articles,bookchapters,conferencepapers,proceedingpapers,meetingabstracts,books

anddocuments,clinicaltrials,andrandomizedcontrolledtrials.Onlysystematicandmetaanalysisreviewswereincluded,andtheirsearchstrategieshadtoclearlyspecifyandadhere toThePreferredReportingItemsforSystematicreviewsandMeta-Analyses(PRISMA) guidelines[23].Thesereviewarticlesallowedforquickandefficientidentificationof primarysources/articlesreportingonschoolgardeninginterventions.

2.3.SelectionofSchoolGardeningReviews,PrimaryArticles,andInterventions

Identifiedreviewarticles(Stage1)wereexportedtoEndNotereferencemanagement software(EndNote™ 20,ClarivateAnalytics,Chandler,AZ,USA).Duplicaterecords wereremoved.Titlesandabstractsweremanuallyscreenedfortermsrelatedto“school garden/s”or“schoolgardening”,andarticleswereassessedforeligibilityandinclusion.

Stage2includedscreeningthefulltextofeacheligiblearticletoidentifyprimary articlesreportingpositivehealthandwell-beingoutcomes.Positivehealthandwellbeingoutcomesweredefinedbroadlyashavingimprovedchange,eitherdetermined quantitatively(e.g.,increasedfruitandvegetableintake)orimprovedbenefitdetermined qualitatively(e.g.,improvedbehaviorstowardsfruitandvegetables).Positivehealthand wellbeingoutcomeswereidentifiedfromeithertext,tabulateddata,orfiguredata.Allstudy designswereidentified,comprisingquantitative,qualitative,andmixed-methodsstudies. DuringStage3,thefulltextofeachprimaryarticlewasreviewedtoidentifyspecific schoolgardeninginterventions.

2.4.DataExtraction,Appraisal,Synthesis,Analysis,andEvaluation

Publicationdetails,includingauthors,yearofpublication,location,objectives,study design,duration,participants,samplesize,outcomesinvestigated,methodofmeasuring outcomes,anddetailsofpositivehealthandwell-beingoutcomes,wereextractedfromall includedarticles.Tohelpimprovethecompletenessinthereportingofthevariousinterventions,theTemplateforInterventionDescriptionandReplication(TIDieR)checklistand guidelineswereused[24].Dataextractionwassupplementedwithkeycomponents:rationale,materials,procedures(activities),providers,delivery,timing,tailoring,modifications, andplanning.

Dataanalysisdrewontheprinciplesofarealistsynthesisforeachschoolgardening intervention.Thisconsistedofidentifyingtheunderlyingcausalorpotentialmechanism/sactingtowardpositivehealthandwell-beingoutcomesbyproducingaContext–Mechanism–Outcomeconfigurationforeachoftheschoolgardeninginterventions.Ifa numberofprimaryarticleswereassociatedwithasingleintervention,thentheirdatawere combinedduringthisContext–Mechanism–Outcomeconfigurationprocess.

3.Results

3.1.IdentificationofSchoolGardeningInterventions

Stage1screeningidentified6reviewsforinclusion[10,13–15,17,18](Figure 1; SupplementaryTableS1);Stage2screeningidentified65primaryarticleswithpositive healthandwell-beingoutcomes;andStage3screeningidentified35articlesassociated with24schoolgardeninginterventions[25–59].

andarticlesassociatedwithschoolgardeninginterventions.

3.2.

3.2.Context–Mechanism–OutcomeConfiguration

For each intervention identified, a Context–Mechanism–Outcome configuration was developed, using the extracted data together with supplementary information from the TIDier process (Table 1).

Foreachinterventionidentified,aContext–Mechanism–Outcomeconfigurationwas developed,usingtheextracteddatatogetherwithsupplementaryinformationfromthe TIDierprocess(Table 1).

3.2.1.ContextofSchoolGardeningInterventionswithPositiveHealthand

Well-BeingOutcomes Location,GardenSpaces,andFacilitation

Identifiedschoolgardeninginterventionswereconductedacrossawiderangeofgeographicallocations,includingAustralia[25–32],theUnitedKingdom[33–35,57],theUnited States[36–56],India[57],Kenya[57],Bhutan[58],andNepal[59](SupplementaryTableS2). Interventionsmostlyutilizedgardensatschoolorchildcarepremises,withtheexception beingcommunitygardensorasummercampgarden[36,40,44].Childrenandfamilies participatedinthedesignofgardensininterventions[27,29,30,57].Initiativeswereprimarilyfacilitatedbykindergarten,elementary,primary,and/orsecondaryschool,and childcarecenterstaff[25–35,37–55,57–59],withresearchteams[25,26,28,42,44–48,56],Universitydepartments[39,40],andexternalpartnersand/orspecialistscontributinginsome contexts[25,26,29–49,53–56,58,59].

Context(Materials/Activities)MechanismOutcomes(Health/Well-Being)

Howdoyougrow?Howdoesyourgardengrow?[25,26]

10-weekprogramwithGrade5–6students

• “Howdoyougrow?”nutritioneducationcurriculum withtopicsonbody,plants,nutrition,health,physical activity,andgoalsetting

• “Howdoesyourgardengrow?”schoolgarden componentincludedtheuseofagardenandthe productionofaclassroomcookbook

• Newsletterstoencouragefruitandvegetableintake byfamilies

• Hands-onlearningexperiencewithgarden-enhanced nutritionaleducationwithincreasedexposure tovegetables

• Somegender-specificfactors.e.g.,femaleteachersand femalestudentsperformedbettertogether,andgirls socializedmoreincookingandgardening

MulticulturalSchoolGardens[27]

2-yearprogramwith6–12-year-oldchildren

• Higherwillingnesstotastevegetablesandhighertaste ratingsofvegetables,especiallypeas,broccoli,tomato, andlettuce,intheinterventiongroup

• Integrationoftheprogramintotheschoolcurriculum

• Childrenandfamilies(throughthegardeningbuddies’ system)designedthegarden,exchangedcultural activities,andlearnedEnglish

• Experientiallearningthrougha“slow”pedagogical approachthatprovidedinterculturalandenvironmental learningopportunities,togetherwith intergenerationalexperiences

OutreachSchoolGardenProject(OSGP)[28]

6-monthprojectwithGrades5–6and7–9students

• Programenabledincreasedculturalawarenessand sensitivity,increasedsenseofbelongingandsocial connections,andfosteredhealthyeatinghabits

• Nutritionextensivelyintegratedintothe schoolcurriculum

• Teachingstaffrequirednospecificnutritionknowledge orgardeningskillspriortotheproject

• Gardenusedtoassiststudentswithlanguage, mathematics,measuring,problem-solving,writingskills, healthandphysicaleducation,scienceandtechnology, andartanddesign

• Schoolprincipalkeytosupportingstaff,students, andcommunity

• Manycorelessonsabletobeincorporatedintothetheme ofgardenandnutrition,therebyfacilitatingparticipation

• Gardenactsasacatalystforenvironmentalactionand changebeyondtheschool

• Positiveimprovementsinstudent’sknowledgeandskills innutrition,gardening,andphysicalandsocial environmentatschooloverasix-monthperiod

Table1. Cont.

Context(Materials/Activities)MechanismOutcomes(Health/Well-Being)

StephanieAlexanderKitchenGardenProgram(SAKGP)[29–32] 2.5–3-yearprogramswithGrade3–6students

• Childreninvolvedinallaspects,includinggardendesign, planting,nurturing,harvesting,cooking,andsharing multi-coursemealswithspecialiststaff,teachers,and adultvolunteers(oftenparents)

• Programprovidesprofessionaldevelopmentto educators,educationalmaterials,andsupport

• Classesincludeaweekly45mingardenclassand1.5h kitchenclass

• Kitchenandgardenexperiencesareenjoyablefor thechildren

• Hands-onexperientialandsociallearningwith involvementinallaspectsofgardendesign,planting, harvesting,andcooking

• Childrenexposedtoawidediversityoffoods

• Motivationsforvolunteering,includingbeliefinthe programanddesiretosupportschool

GrowingSchoolsandTheGloucestershireFoodStrategy[33] 3-yearprogramswithGrade3andGrade6students

• Increasedstudentengagement,socialskills, andconfidence

• Increaseinchildren’swillingnesstotrynewfoods influencinghealthyeating

• Volunteeringbyparentsledtoenhancedengagement betweenschoolsandthecommunity,formingnew friendshipsandrelationships,leadingtoasenseof belongingandself-worth,andprideandpleasurein thecommunity

• Schoolgardeninginasemi-ruralprimaryschoolwith emphasisonfoodandhealthinthecurriculum

• Childrenparticipatedingrowing,harvesting,andeating vegetablesfromplanters

• Schoolusedhealthycaterersfortheschoolmenu

• Leadershipandvision(specifically,theheadteacher) combinedwithcommunityinvolvement(specifically, children,teachers,parents,andschoolgovernors)

• Acceleratedandeffectivelearningthroughcritical thinking,practicalhands-onapproach,and decision-making,whichhelpedstudentsconnectideasto practiceandprovidedmotivationandasense ofownership

• Improvementinattitudes,awarenessofhealth,andfood

• Improvementinchildren’seatinghabits

RoyalHorticulturalSociety(RHS)CampaignforSchoolGardening[34,35]

1-yearprogramswithGrade3–4students

• RHS-ledinterventionincludedvisitsbyadvisorstowork withteachersandchildren,teachertraining,and provisionoffreeteacherresourcesversusateacher-led intervention,withstandardadvicegivenbyanRHS specialistforsupportindevelopingaschoolgarden

• Knowledgeandattitudesmediatebehavioralchange towardsfruitsandvegetables

• Modelingandactivitybehaviorofteachertowardfruit

• Teachers’willingnesstoengageandtheirown gardeningbeliefs

• Teachershavedailycontactwithchildren

• RHS-ledinterventionassociatedwithagreaterincrease intotalvegetablesrecognized

• Teacher-ledgroupassociatedwithhigherintakeoffruit andvegetablesandwillingnesstotastenewfruits

Table1. Cont.

Context(Materials/Activities)MechanismOutcomes(Health/Well-Being)

DeliciousandNutritiousGarden[36]

12-weekinterventionwithGrade4–6studentsattendingasummercamp

• Gardenplotdesignedandprepared

• Learningaboutplantsandnutrition

• Growing,harvesting,andtastingfruitandvegetables

• Preparinghealthfulsnacks

• Sharingexperienceswithfamilythroughnewslettersand home-basedactivities

• Highvalueplacedonthe“seedtotableapproach”with hands-onactivities,includingplanting,maintaining, harvesting,andpreparingfoods

• Repeatedexposuretofruitandvegetablesthroughtaste tests,gardenwork,andsnacks

• Childrenwereagentsofchangeinfamiliesthrough familyinvolvementinhome-basedactivities

EatYourWaytoBetterHealth(EYWTBH)[37]

6–10-weekprogramwithGrade3students

• Changeinbehavior(askingforfruitandvegetablesat home)andincreasedintakeoffruitandvegetables

• Increaseinvegetablepreferences

• Senseofownershipandprideinthegarden

• LessonspairedwithJuniorMasterGardener:Healthand NutritionfromtheGardencurriculumadaptedtosuitthe needsoftheschoolandcommunitythatfacilitated experientiallearningatschoolandtake-homeactivitiesto dothroughtheinvolvementofparents/guardians

• Parents/guardiansareseenasimportantenvironmental factorsinformingbehaviorandself-efficacy

• Greaterongoingfruitandvegetableconsumptionin thosewithpreviousdiversefruitandvegetable consumption

GardensReachingOurWorld(GROW)[38]

4.5-weekprogramwithKindergartentoGrade5students

• Improvedhealthyfoodchoiceself-efficacyandhigher diversityoffruitandvegetableconsumption

• Microfarmusedasagardeningintervention,with studentsinvolvedingrowing,harvesting,and samplingmicrogreens

• Saladbarincorporatedintotheschoolcafeteriaand presentedtostudentsaspartoftheschoollunchprogram

• Gardeninglessonsandactivitiesmayhaveenableda greaterquantityofvegetablesselectedfromthesaladbar

• Increasedconsumptionofvegetablesperdayduringthe interventionperiod

• Continued,buttoalesserdegree,increaseinvegetable consumptionpost-intervention

Table1. Cont.

Context(Materials/Activities)MechanismOutcomes(Health/Well-Being)

GotDirt?GardenInitiative[39]

4-monthinitiativewith7–13-year-oldstudents

• Smallassistancegrantsprovidedtosetupschoolgardens

• Schoolgardenseitherin-ground,incontainers, microfarms,orcoldframe

• Trainingprovidedforteachersandearlychildhood providerswithschoolgardens

• Childrenparticipatedingardeningactivities

• Gardensimpactinasocio-ecologicalsystemsmanner, includingintrapersonal,interpersonal,organizational, community,andpolicylevels

• Multi-layeredimpactsleadtocumulativeeffectsand sustainedbehavioralchange

GrowingHealthyKids(GHK)[40]

1-yearprogramwith2–15-year-oldchildreninthecommunity

• Increasedconsumptionoffruitandvegetableswith studentstrying/tastingnewfruitandvegetables (especiallythosegrownintheirgarden)

• Choosingfruitandvegetablesinsteadofchipsorcandy

• Communitygardenslocatedatelementaryschools, communityparks,andprivately-ownedland

• Materialsandtoolsprovidedalongwithweeklysessions tolearnandpracticegardeningskills

• Workshopsprovidedinformationandresourcesfor makinghealthyfoodchoices(alsoofferedinSpanishfor Hispanicfamilies)

• Socialeventsenabledwholefamilyinclusionwith dinners,meetings,gardenconstructionactivities,and newsletterproduction

• Gradually,familiesassumedresponsibilityforrunning activitiesandevents

• Communitygardensappealtonewly-arrivedimmigrants bymaintainingculturaltraditions

• Continuedaccesstocommunitygardenswithtechnical supportandresources

• Familiesengagewiththeprovisionofnutritionalclasses

• Projectabletoinfluencepolicychange,enabling longer-termsustainability

• Increasedavailabilityandconsumptionoffruitsand vegetablesamongchildrenofparticipatingfamilies

• ImprovementinhealthasmeasuredthroughBodyMass Index(BMI)

Table1. Cont.

Context(Materials/Activities)MechanismOutcomes(Health/Well-Being)

HealthierOptionsforPublicSchoolchildren(HOPS)/TheOrganWiseGuys(OWG)[41]

2-yearprogramwith4–13-year-oldchildren

• Curriculumcomponentdesigned;educationand instructionalmaterialprovidedtoteachchildren,parents, teachers,andotherschoolstaffaboutgardening,good nutrition,andhealthylifestyles

• Modificationsmadebydietitianstoschool-provided breakfasts,lunches,andsnacks

• Increasedphysicalactivityopportunitiesmadeavailable duringschooltime

• School-based,multi-level,multi-sectorapproach

• Factorsactinginconcord,includingdietarychanges, nutritioneducation,andphysicalactivitycomponents

• SignificantimprovementsinBMIandbloodpressure amonglow-incomeHispanicandWhitechildreninthe interventiongroup

• Curriculumtoolkitusedbasedonextantgardencurricula, includingnutrition,horticulture,andplantscience

• Educatorsledgardenactivities,includingplanting, weeding,harvesting,foodsafety,gardenmaintenance, engagingvolunteers,capacitybuilding,and programsustainability

HealthyGardens,HealthyYouth[42]

2-yearprogramwithGrade4–5students

• Gardening-basedlessonsmaybeaneffectivepedagogical tool,facilitatingareductioninsedentarybehaviors throughmovementsincludingstanding,kneeling, squatting,etc.

JuniorMasterGardener“HealthandNutritionfromtheGarden”[43] Upto12-weekprogramswithGrade2–5students

• Highermoderateandvigorousphysicalactivity, especiallyduringoutdoorgarden-basedlessonsthan duringclassroom-basedlessonsintheinterventiongroup

• Nutritioncurriculumwithmaterialincludingactivity guide“HealthandNutritionfromtheGarden”

• Deliveryofactivities(e.g.,dietaryfiber,budgeting, gardening,plantneeds,healthyfoodpyramid,label reading,andfoodstoragemethods)variedaccording tolocation

• Greaterunderstandingofwhatshouldbeeatenandwhy itshouldbeeaten

• Nutritioncurriculumeffectiveatallages,including youngerandolderchildren

• Nutritioncurriculumenablesabetterunderstandingof foodgroups

• Increasedexposuretofruitandvegetablesthrough gardeningactivities

• Significantimprovementinknowledgeregardingthe benefitsofeatingfruitandvegetables

• Improvedeatinghabitsbyeatinghealthiersnacksafter thenutritionalprogram

Table1. Cont.

Context(Materials/Activities)MechanismOutcomes(Health/Well-Being)

LASprouts[44–48]

12-weekprogramswithGrade3–5students

• Adaptivecurriculumwithculturallyrelevantfocus, taughtbyaneducatorwithanutritionor gardeningbackground

• Interactive,hands-ongardeningactivitiespluscooking andnutritioneducation

• Raisedgardeninthecommunitygardenandschool settingtoprovideparallelclassesforparentsandchildren

• Teachingconductedafter-schooloncampus

• Mealspreparedinsmallteamspreparedvegetable/fruit snacksandsharedinafamily-stylemanner

• Monthlyvisitstolocalfarmers’marketsintegratedinto theprogram

• Studentsencouragedtoreplicaterecipesand conversationsathome

• Successesandchallengesdocumentedbyeducators

• Projectmanagersobservededucator’steachingtoensure adherencetothecurriculum

• Combinationofculturally-tailoredcomponentsand hands-onactivitiesforgardening,cooking,andnutrition educationthatinfluencedattitudes,preferences,and motivationsleadingtoincreasedknowledgeand behavioralchange

• Experientiallearning,beginningwitheasyrecipesto morecomplexrecipes

• Affordabilityofhome-grownfoods

• Efficaciousapproachusedtoteachstudentstogrow, prepare,andeatfruitandvegetables

• Increasedgardeningandcookingattitudes,self-efficacy, motivation,andbehaviorassociatedwithincreased dietaryfiberandvegetableintakeandgardeningathome

• Increasedpreferenceforvegetables,increasedpreferences forthreetargetfruitsandvegetables,andimproved perceptionsthat“vegetablesfromthegardentastebetter thanvegetablesfromthestore”

• FewerLASproutsparticipantshadmetabolicsyndrome afterinterventionthanbefore,whilemetabolicsyndrome increasedincontrols

• DecreaseddiastolicbloodpressureinLASprouts participantscomparedwiththecontrolgroup

• Foroverweightsub-sample:significantincreasein dietaryfiberintake,reductioninBMI,waist circumference,andlessweightgain,comparedtothose inthecontrolgroup

• Gardenplotsavailableinschools

• Classroomgardensmadeavailableforteaching andguidance

• SupportprovidedbyMasterGardeners

MasterGardenerClassroomGardenProject[49] OngoingprojectwithGrade2–3students

• Gardensenabledlearningvaluablemorallessons aboutlife

• Hands-onexperiencesfacilitatedacademiclearning

• Schoolgardeningleadstogreaterhomeandfamily gardening,inturnleadingtomoreactive schoolparticipation

• Rewardinginteractionsleadstopleasantexperiences

• MasterGardenerwasintegraltotheproject

• Positiveeffectsonschoolchildrenincludedgaining pleasurefromobservingtheflourishingof gardenproducts

• Childrenexperiencedincreasedinteractionswith parents/adults

• Childrenexperiencedthelearningofemotionsassociated withharmingthingsofvalue

Table1. Cont.

Context(Materials/Activities)MechanismOutcomes(Health/Well-Being)

NutritionintheGarden[50,51]

1-yearprogramwithGrade3–5students

• Integrationofnutritioneducationintocurricula

• Useofactivityguide‘NutritionintheGarden’ specificallyrelatingtofruitandvegetables

• Thirty-fouractivitiesdividedinto10units,combining horticultureandnutritionsubjectsrequiringtheuseofa gardenorindoorgrowlabandinvolvinggarden maintenance,salsamaking,cookingclasses,planting, harvesting,andconsuminggardenproduce

• Experientialexposuretofruitandvegetablesbuilds self-efficacyandincreasedknowledgeandawareness ofnutrition

• Studentswithagreaterneedforimprovementare moreimpacted

• Youngerstudentsmoreopentonewideas andexperiences

• Femalesaremorereceptivetohealthandnutrition educationandconcernedaboutphysicalappearance

ShapingHealthyChoicesProgram(SHCP)[52] 1-yearprogramwithGrade4–5students

• Improvedstudents’preferencesandattitudestoward fruit,vegetables,andvegetablesnacks

• Participatingadolescentsingarden-basedintervention increasedservingsoffruitandvegetablesmorethan controlschools

• SignificantincreasesinvitaminA,vitaminC,andfiber intakeinexperimentalschools

• Curriculumcomprisedoffivecomponents:nutrition educationandpromotion,familyandcommunity partnerships,supportingregionalagriculture,school foodavailability,andschoolwellness

• Activitiesincludednutritioneducation,cooking demonstrations,schoolgardens,familynewsletters, healthfairs,saladbarimplementation,procurementof regionalproduce,andschoolwellnesscommittees

• Majorfocusonconsistentmessagereinforcementthrough lunchroomconnections,communityconnections,and deliveryatmultiplevenues

• Messagingcoordinatedthroughoutallprogram components,includinggrowing,harvesting,andcooking

• Hands-ongardeningandcookingactivitiesenhancedthe deliveryofthecurriculum

• GreaterimprovementinBMIpercentile,BMIz-score,and waist-to-heightratiointheinterventioncomparedwith controlschools

• Significantimprovementsinnutritionknowledgeand totalvegetableidentificationininterventionschools

Table1. Cont.

Context(Materials/Activities)MechanismOutcomes(Health/Well-Being)

SproutingHealthyKids(SHK)[53]

5-monthprogramwithGrade6–7students

• In-classlessonscomprisedtopicsonhealthyfood,food production,andfoodsecurity

• Farm-to-schoolcomponentenabledlocallygrown vegetablestobeservedinthecafeteria

• Taste-testingofvegetablescoincidedwithfarmers’visits, withencouragementtotrydifferentvegetables

• After-schoolvisitstoenablestudentstoprepareandcook gardenproduce

• Farmvisitstoenableknowledgedemonstrationand assistancewithfarmtasks

• Exposuretooneinterventioncomponentsufficientto changeknowledgeregardingfruitandvegetables

• Behavioralandpsychologicalchangetowardsfruitand vegetablesmaycomethroughacombinationofactivities, includingexposuretotwoormoreintervention components.e.g.,

◦ Interactivepresentationsbyexpertsor“authority figures”suchasfarmers

◦ Exposuretoagreatervarietyoffruitandvegetables throughtastetesting

◦ Provisionoflocallygrownproduce

TexasSprouts[54]

9-monthinterventionwithGrade3–5students

• Comparedwithstudentsexposedtolessthantwo interventioncomponents,studentswhowereexposedto twoormorecomponentsscoredsignificantlyhigheron fruitandvegetableintake,self-efficacy,andknowledge andloweronpreferenceforunhealthyfoods

• Althoughnotsignificant,farmer’svisits,tastetesting, andcafeteriacomponentshadthelargesteffectsizes

• Raisedvegetablebeds,nativeherbbeds,andlargesheds fortoolsandmaterialsbuiltonschoolpremises

• Nutritioncurriculadeliveredbytrainedandpaid nutritionandgardeningeducators

• Includedpreparation/cookingoffruitandvegetables, nutritiousfoodchoices,eatinglocallyproducedfood, low-sugarbeverages,healthbenefitsoffruitand vegetables,eatinghealthfullyinfooddesert neighborhoods,andfoodequityandcommunityservice

• Lessonstaughtbywell-trainedandpaidnutritionand gardeningeducatorsmaybeimportant(although notsustainable)

• Increasedvegetableintakeintheinterventiongroup

Table1. Cont.

Context(Materials/Activities)MechanismOutcomes(Health/Well-Being)

Texas!Grow!Eat!Go!(TGEG)[55]

4–6-monthinterventionwithGrade3students

• Gardencomponentincludedcurriculacenteredaround vegetablesgrownintheschoolgarden

• Bothgardenandphysicalactivitycomponentsincluded intheintervention

• SchoolgardensconstructedbyAgriLifeextension specialists,teachers,students,andparents

• Studentsgrewvegetables,participatedinbothfresh vegetablesamplingandrecipedemonstrations,and take-homefamilyactivities

• Experientiallearningactivities,includinggrowingand harvestingvegetables,learningthebenefitsofeating vegetables,preparingsimplevegetablerecipes,and consumingfoodfromrecipesmadeatschool

• Improvednutritionknowledge,withanincreasein vegetablepreferencesandvegetablestasted

• DecreasedBMIpercentilerelativetochildrenin comparisonschools

WatchMeGrow[56]

4-monthprogramwith3–5-year-oldchildrenatchildcarecenters

• Raisedbedsinstalledatinterventionchildcaresites,with variousfruitandvegetablecropsgrownandproduce integratedwiththecenter’smenu

• Externalhealthandgardeningexpertiseprovided

• Curriculamodulesandactivitiescenteredanddelivered aroundeachcrop

• Publishedchildren’sbooksusedtoencourageconnection toeachcrop

• Whenvegetablesareplacedonplatesforchildrento consume,thismayleadtogreateracceptance ofvegetables

• Morevegetablesservedto;andmorevegetables consumedbychildrenintheinterventiongroup

Table1. Cont.

Context(Materials/Activities)MechanismOutcomes(Health/Well-Being)

GardensforLife(GfL)[57]

3-yearprojectwith7–14-year-oldstudentsindifferentcountries

• Schoolgardensdeveloped,toolssupplied,withthe growingoffruitandvegetables

• Childreninvolvedinthegardenset-up

• Curriculumactivitiesprovidedtoimprove understandingoffruitandvegetables,gardenfeatures anddesign,gardeningactivityandknowledge,and communityandcurriculumlinks

• Experientiallearningpositivelyimpactedcurriculum learninginallsettings,especiallythroughimproved self-esteem

• Mechanismmaydependoncultureandenvironment. e.g.,Englishchildrenviewedschoolgardensforpleasure, leisure,play,andenjoyment,whereIndianandKenyan childrenviewedschoolgardensforlearning,community, security,andpeace,whileIndianchildrenviewedschool gardensinrelationtoconservationissues

VegetablesGotoSchool[58,59]

2-yearprogramwithGrades6–7studentsindifferentcountries

• Tenconceptsdevelopedtocategorizeoutcomes,with generallyhighestscoresrecordedforknowledgeonfruit andvegetables,gardeningactivityandknowledge,and curriculumandcommunitylinks

• Curriculumusedtoteachstudentsaboutgardening, nutrition,andWASH,withemphasison“learning bydoing”

• Projectteamtaughtteachershowtomanagetheschool garden,withchildrencultivatingnutrient-dense vegetablesundertheguidanceofteachers,with parentalsupport

• Promotionalactivitiesusedtoreinforcelessonsand strengthentheimpact

• Linkageofschoolvegetablegardenstocomplementary lessonsinagriculture,foodandnutrition,and promotionalactivities

• Combinationofgardeningandeducationmoreeffective thansinglecomponents

• Collaborationandcoordinationamongnutrition,health, andagriculturalinterventions

• Significantincreaseinchildren’sawarenessaboutfruit andvegetables,knowledgeaboutsustainableagriculture, knowledgeaboutfood,nutrition,andhealth,andstated preferencesforeatingfruitandvegetables

• Increasedprobabilitythatchildrenincludedvegetablesin theirmeals

Abbreviations:OSGP,OutreachSchoolGardenProject;SAKGP,StephanieAlexanderKitchenGardenProgram;RHS,RoyalHorticulturalSociety;EYWTBH,EatYourWaytoBetter Health;GROW,GardensReachingOurWorld;GHK,GrowingHealthyKids;HOPS,HealthierOptionsforPublicSchoolchildren;OWG,OrganWiseGuys;SHCP,ShapingHealthy ChoicesProgram;SHK,SproutingHealthyKids;TGEG,Texas!Grow!Eat!Go!;GfL,GardensforLife.

Rationale

Schoolgardeninginterventionswerepredominantlyusedtoinfluenceschool-aged children’sknowledge,attitudes,and/orbehaviorstowarddietandnutrition,particularlyin connectiontoincreasingfruitand/orvegetableconsumption [25,26,29,34–39,42–48,50–56]. Inmanyinstances,thiswasassociatedwiththeimpetusofaddressingtheprevalenceand preventionofobesity[38–41,44–48,50–55],particularlyaslow-incomeminoritygroups maybedisproportionatelyaffectedbylowerfruitand/orvegetableintakeandexperience higherratesofchildhoodobesity[44–48,55].Additionally,theabilityofschoolgardens toinfluencephysicalactivityandactivelivingformedpartofthereasoningforsome interventions[38,42,55].

ParticipantsandActivities

Mostoftheinterventionswereconductedatprimaryschools,withparticipating childreninGrades2through6.Inmultipleinstances,nutritionandgardeningeducationwasintegratedintothecurriculumitselfanddeliveredthroughschoolgardenand kitchenactivities[27–33,37,42,43,50,51,54–56,58,59].Specifically,childrenwereprovided withopportunitiestoparticipateingrowing,harvesting,andconsuminggardenproduce (usuallyfruitandvegetables),withsomeenablingthesharingofmealstogetherina‘family style’environment[29,30,40,44,46].Parentalandfamilyengagementwerealsoencouraged throughnewsletters[25,26,36,40,52],take-homeactivities[36,37,55],andopportunitiesfor volunteering[29–32].Teachertrainingwasalsoanimportantcomponentinseveralinterventions,particularlywithnutritionalandgardeningactivities[34,35,39,41,58,59].Several interventionsfacilitatedculturalawareness,includingopportunitiesforculturalexchange orappreciationforculturallytailoringinterventionsinaccordancewithdemographic profilesasfocalpoints[27,40,44–48,55,57–59].

Someinterventionswereadaptedfromexistingcurricula,activityguides,peer-reviewed resources,orgarneredfrompreviouspilotinitiatives.Forexample,severalinterventions werebasedonthecurriculumofJuniorMasterGardener® (CollegeStation,TX,USA)and Health&NutritionfromtheGardenprograms[37,43,54],andseveralutilizedtheactivity guidedevelopedbyLinebergerandZajicek(1998)[25,26,50,51].Further,afewinterventions werebasedonthemodelofMontessori(1964)andgroundedinschoolgardeningresearch andgarden-basedlearning[49,57].

Duration,Frequency,andType

Typically,thedurationofinterventionsrangedfrom6weeksto3years[25–59].“Frequency”and“type”ofinterventionalsovariedconsiderablyandincludedamixofweekly lessons(teachingnutrition,cooking,and/orgardening) [25,26,28–30,36,37,40,43–48,53,58,59], occasionalexpert/specialistvisits[30,34,53,56],fieldtrips[46,53],take-homeactivities [52,55], nutritionandcookingdemonstrationsand/orworkshops[40,52],parentallessons [44,47,54], andteachertrainingsessions[34,35].

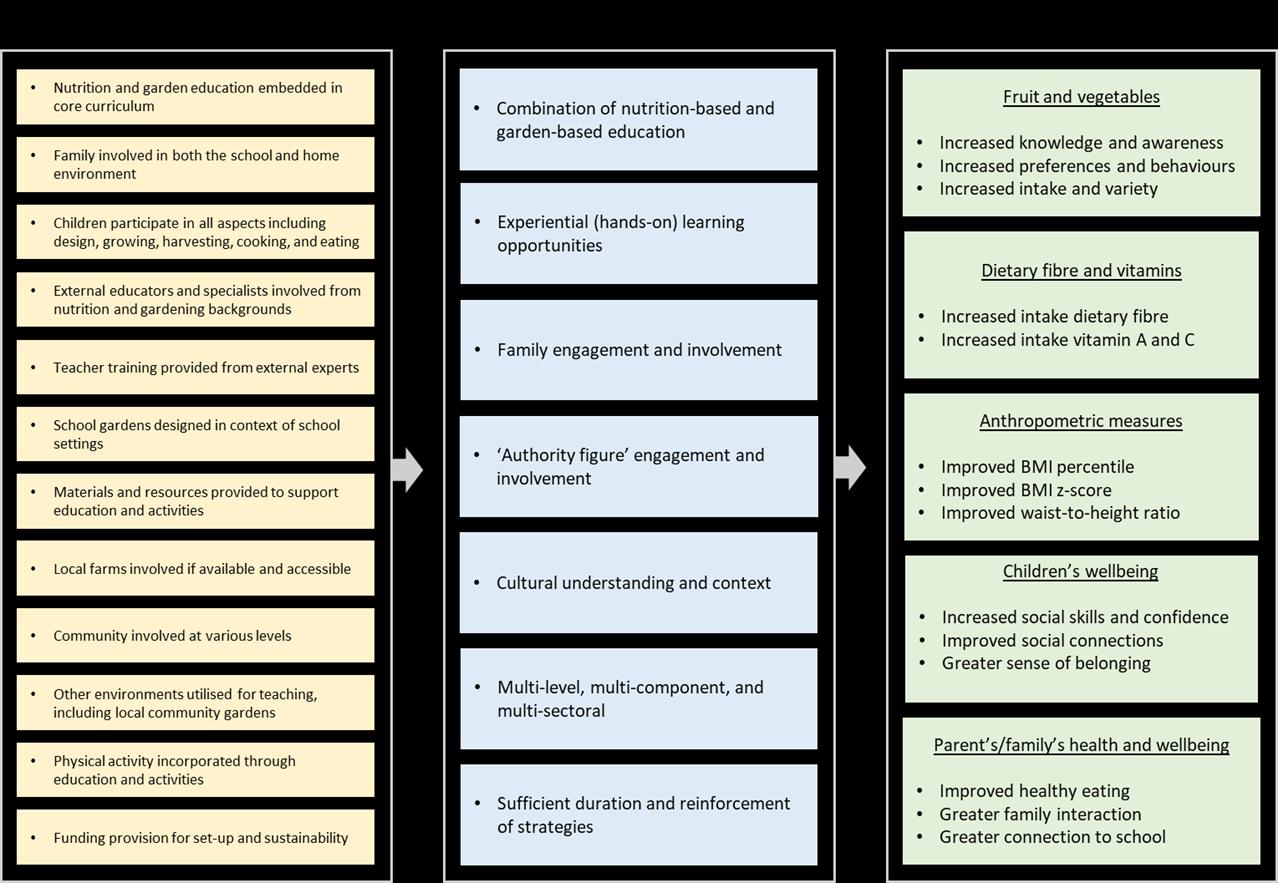

3.2.2.MechanismsLeadingtoPositiveHealthandWell-BeingOutcomes

Thecombinedactionofnutrition-basedandgarden-basededucation,oftenintegrated intothecurriculum,wasacommonmechanismthatcontributedtowardspositiveoutcomes, particularlyinconnectiontofruitand/orvegetables[25,26,33,44–48,50,51,58,59].

Experientialor“hands-on”learningexperiencesforstudentswerealsoacommonstrategyamongstmultipleinterventions,withchildreninvolvedingrowing,nurturing,harvesting,preparing,andconsumingproducefromschoolgardens [25–27,29–32,36,44–51,55,57] Reportsalsoemphasizedtheeffectivenessofexperientialexperiencesasapedagogical learningtoolforstudents,withnewlylearnedknowledgeinfluencingattitudes,behavioral change,andbuildingself-efficacytowardshealthiereating[27,42].

Theengagementandparticipationoffamiliesprovidedopportunitiesforintergenerationallearning,informingbehaviorsandself-efficacyofchildren,andparents/guardians volunteeringatschool[27,29–32,36,37,49].Schoolteachers,principals,andother“authority

figures”wereimportantforbehavioralmodeling,leadership,andexpertiseasnutrition orgardeningspecialists[28,33–35,49,53,54].Someinterventionsweretailoredforminority groups,providingexperientiallearningopportunitiesinthecontextofculturalbackgrounds andopportunitiesforinterculturallearning[27,40,44–48,57–59].

Adistinguishingfeaturewastheuseofmulti-prongedapproaches.Forexample,this includedtheadoptionofmulti-levelandmulti-sectoralmethodologies,withinvolvement fromindividuals,community,andgovernmentalagencies.Inaddition,programsimplementedmulti-componentapproachesincluding,forexample,acombinationofnutritionbasededucation,familyinvolvement,developmentofcommunitypartnerships,support fromtheagriculturalsector,andschoolwellnesscommittees[33,39–41,44–48,52,53,58,59].

Thereinforcementofactivitiesleadingtosustainabilitywasalsoseenasakeymechanism,suchasrepeatedand/orincreasedexposuretofruitandvegetablesduringthe interventionduration.Thenotionofensuringtheimpactsofschoolgardeningactivities wassustainedwasalsoaccomplishedbyconsistentandcoordinatedmessagingthrough multipleinterventioncomponents[36,37,39,40,43,52].

3.2.3.PositiveHealthandWell-BeingOutcomes

Positivehealthandwell-beingoutcomeswereprimarilyrelatedtofruitandvegetables(e.g.,increasedknowledge,awareness,preferences,behaviors,intake,andvariety) [25,26,34–40,43–48,50–59];dietaryfiber,andvitaminsAandC(e.g.,increasedintake)[44–48,50,51];anthropometricmeasures(e.g.,improvedBMIpercentile,BMIz-score, andwaist-to-heightratio)[40,41,44–48,52,55];children’swell-being(e.g.,increasedsocialskillsandconfidence,improvedsocialconnections,andagreatersenseofbelonging) [27–32];andparent’s/family’shealthandwell-being(e.g.,improvedhealthyeating, greaterfamilyinteraction,andgreaterconnectiontoschool)[27,29–32,49].

4.Discussion

Throughthisrealistsynthesis,weinvestigatedhowschoolgardeningimproveshealth andwell-beingforschool-agedchildren,findingthatacombinationofmechanismsoperates intandemunderdifferentcontextsforthesuccessoftheschoolgardeninginterventions toyieldpositiveoutcomes.Theimpetusofmanyinterventionswastoincreasefruitand vegetableintakeandaddressthepreventionofchildhoodobesity.Mostwereconducted atprimaryschoolswithparticipatingchildreninGrades2through6andwerelocated inhigh-incomecountries,includingtheUnitedStatesandAustralia.Themechanisms rangedfromembeddingnutritionandgardeneducationinthecurriculumtoexperiential learning,engagementandinvolvementoffamilyand“authorityfigures”,andtherelevance ofculturalcontext.Typesofpositiveoutcomesincludedincreasedfruitandvegetable consumption,dietaryfiberandvitaminsAandC,improvedBMI,andimprovedwell-being ofchildren.

Thereviewresultsinevidencethatthebenefitsofcombiningnutrition-basedand garden-basededucationareimportantinimprovingoutcomes,particularlywithattitudes andbehaviorstowardfruitandvegetableconsumption.Thissuggeststhatclassroombasedlessonsmaybeenhancedthroughpracticalandgarden-basedlessons.Forexample, intheHowdoyougrow?Howdoesyourgardengrow?intervention,thecurriculum encompassedavarietyoftopicsinrelationtohealthandwell-being,reinforcedthrough ‘hands-on’exposuretogardeningactivities[25,26].Similarly,theNutritionintheGarden programintegratednutritioneducationintothecurriculum,withparticularemphasison apracticalapplicationinvolvingcomprehensivegardeningandcookingactivities[50,51].

Inaddition,findingsfromBerezowitzetal.(2015),throughareviewofschoolgarden studies,concludethatgarden-basedlearningmayfavorablyaffectfruitandvegetable consumptionbutalsopositivelyimpactsacademicperformance[11].Similarly,experiential learningstrategieshaveprovedusefulinimprovingchildren’sknowledge,attitudes,and behaviorstowardeatingmorehealthily,includingthoseinschoolgardensettings[18].

Schools,therefore,havesignificantpotentialtocreategardenspacesforenablingexperi-

entialexperienceslinkedtothecurriculum,leadingtoenhancedlearningandimproved healthandwell-beingoutcomes.

Familyinvolvementinschoolgardeninginitiativeswasatthecenterofimpacting positivehealthandwell-beingoutcomes,demonstratedacrossseveralinterventions,with mechanismsworkingatmultiplelevels.Previousresearchreportsthatfamilyinvolvement helpschangeeatingbehaviorsinschool-agedchildren[14].Consistentwiththe“bioecologicaltheory”and“primarysocializationtheory”,achild’sdevelopmentiscollectively impactedbynumerousproximal(e.g.,parents,peers,community)anddistal(e.g.,cultural norms,laws,customs)influencesandtheircomplexinterdependencies[60].Accordingly, theimportanceofparentsinpromulgatinghealthynutritionbehaviorsinchildrencannotbe underestimated.Garneringthecooperation/participationofasmanyparentsaspossiblein school-basedgardeningcanbestrengthenedusingvolunteeringprogramsandtake-home activities,includingproduceandrecipes.Thesestrategieshaveproventobeeffectiveat meaningfullyengagingparentswithschool-garden-relatedactivities[14].

Visionaryleadershipandinspirationalrolemodelsareintegraltoschool-basedgardeninginterventionsleadingtohealthandwell-beingoutcomes.Strongengagementbetween studentsand“authorityfigures”,includingschoolteachers,schoolprincipals,andexternal experts,hasconsistentlybeenshowntobeassociatedwithpositivehealthandwell-being outcomes.Forexample,GrowingSchoolsandTheGloucestershireFoodStrategyidentified clearleadershipandvisionfromtheheadteacherascriticalforinitiatingchange[33].FindingsfromtheRoyalHorticulturalSocietyCampaignforSchoolGardeningindicatehowthe willingnessofteacherstoengagewiththeinterventionmaybeimportanttowardsagreater intakeoffruitandvegetables[35].Inaddition,Viola(2006)identifiedhowsupportfrom theschoolprincipaliskeyintheOutreachSchoolGardenProject,leadingtoimproved nutritionknowledgeandskills[28].Morerecently,Mannetal.(2022)synthesizedevidence ofnature-specificoutdoorlearningoutsideoftheclassroomonschoolchildren’slearning anddevelopmentandsuggestedthatallteachertrainingeffortsshouldincludeskilldevelopmentactivitiespertainingtothistypeofpedagogicalapproach[61].Integrationof ideassuchastheseisimportantasteachersareoftenhighlyinfluentialduringchildhood educationanddevelopment,asindicatedabove.

Consideringtheincreasinglydiversesocietieswedwellin,itisnosurprisethatmany madeaconsciousefforttoaccommodatethevaryingculturalneedsintheirinterventions. Forinstance,culturally-tailoredcomponents,togetherwithexperientiallearning,werecentraltotheLASproutsprogram,leadingtomanypotentiallybeneficialoutcomes,including changedbehaviorsandpreferencestowardsdietaryfiber,fruit,andvegetablesforchildren ofHispanic/Latinoheritage[44–48].Similarly,Ornelasandcolleagues(2021)reportedthe importanceofdrawingonculturalstrengthsandtraditionalpracticesinaddressingchildhoodobesitythroughschoolgardening,specificallyforAmericanIndiancommunities[62]. Therefore,culturalaspectsand/orethnicdiversitywouldbeanimportantconsideration inthedesignofschoolgardeningprogramstoensurepotentialhealthandwell-being outcomesareculturallysensitiveandsustainable.

Thisrealistreviewhighlightsthatseveralkeyelementsandnumerouspermutationsof contextandmechanismsworkmutually,leadingtopositivehealthandwell-beingoutcomes inschool-agedchildrenthatmaybeobservedcollectively(Figure 2;Table 1).Thesynthesis demonstratesthepotentialforchangewhenimportantcontextualandmechanisticelements aredrawnfromarangeofsuccessfulinterventionsthatmaybeincorporatedintocurrent orproposedschoolgardeningprograms.Thisprovidesguidanceinconjunctionwith publishedsystematicandmeta-analysisreportingonschoolgardeninginterventions.This alsoprovidesatemplateforconsiderationindesigningnewschoolgardeninginterventions orenablingadjustmentandinclusionofadditionalelementstocurrentinterventions.

synthesis demonstrates the potential for change when important contextual

nistic elements are drawn from a range of successful interventions that may be incorporated into current or proposed school gardening programs. This provides guidance in conjunction with published systematic and meta-analysis reporting on school gardening interventions. This also provides a template for consideration in designing new school gardening interventions or enabling adjustment and inclusion of additional elements to current interventions.

Tothebestofourknowledge,thisisthefirsttimeasystematicrealistsynthesiswiththe accompanyinguseofprogramtheoryhasbeenappliedtoschoolgardeninginterventions. Thestrengthofthisapproachliesinusinghigh-levelresearch-basedevidencethrough theidentificationofsystematicandmeta-analysisreviews.Thisinformedidentification ofpertinentpeer-reviewedprimaryarticleswithpositivehealthandwell-beingoutcomes andsubsequentidentificationofschoolgardeninginterventions.Thisapproachenabled theidentificationofevidenceassociatedwithschool-basedgardeninginterventionsas previouslyidentifiedandreviewed,allowingacomparisonofourfindingswiththeexisting literature.DataextractionandTIDierchecklistmethodologiesenabledholisticassessment ofindividualschoolgardeninginterventions,supportingrobustconfigurationofcontext, mechanism,andoutcomesandsubsequentrealistsynthesis.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first time a systematic realist synthesis with the accompanying use of program theory has been applied to school gardening interventions. The strength of this approach lies in using high-level research-based evidence through the identification of systematic and meta-analysis reviews. This informed identification of pertinent peer-reviewed primary articles with positive health and well-being outcomes and subsequent identification of school gardening interventions. This approach enabled the identification of evidence associated with school-based gardening interventions as previously identified and reviewed, allowing a comparison of our findings with the existing literature. Data extraction and TIDier checklist methodologies enabled holistic assessment of individual school gardening interventions, supporting robust configuration of context, mechanism, and outcomes and subsequent realist synthesis.

Notwithstanding the potential for positive outcomes that result from school gardens, it is important to note that the generalizability of the results from these interventions may be limited to high-income countries as most of the programs were based in Australia, the United Kingdom, and America In addition, while a number of programs were based in areas of socio-economic disadvantage, addressing particular health inequities affecting low-income, under-resourced, and/or specific ethnic groups, including a focus on

Notwithstandingthepotentialforpositiveoutcomesthatresultfromschoolgardens, itisimportanttonotethatthegeneralizabilityoftheresultsfromtheseinterventionsmay belimitedtohigh-incomecountriesasmostoftheprogramswerebasedinAustralia,the UnitedKingdom,andAmerica.Inaddition,whileanumberofprogramswerebasedin areasofsocio-economicdisadvantage,addressingparticularhealthinequitiesaffectinglowincome,under-resourced,and/orspecificethnicgroups,includingafocusonchildhood obesityprevention,theresultsmaynotbeentirelygeneralizableandtransferabletoother settings,eitherinotherhigh-incomecountriesorlow-incomecountries.

5.Conclusions

Throughthisrealistsynthesisofidentifiedschoolgardeninginterventions,wehave shownhowvariousmechanismworkmutuallytosupportpositivehealthandwell-being outcomesofschool-agedchildreninparticularcontexts,whichmayassistwithfuture endeavors.Schoolgardeninginterventionspotentiallyholdstrongpromiseinsupporting actiontowardthepreventionofmodernpublichealthproblems,includingfoodinsecurity andchildhoodobesity,bothrequiringurgentglobalattention.

SupplementaryMaterials: Thefollowingsupportinginformationcanbedownloadedat: https:// www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/nu15051190/s1,TableS1:Identificationofschoolgardeningarticles withpositivehealthandwell-beingoutcomes;TableS2:Summaryofschoolgardeninginterventions.

AuthorContributions: Conceptualization,R.H.,K.D.K.A.,T.P.H.,S.J.andA.P.H.;methodology,R.H., K.D.K.A.andT.P.H.;formalanalysis,T.P.H.,K.A.E.P.andK.D.K.A.;investigation,R.H.,K.D.K.A., T.P.H.andA.P.H.;resources,K.A.E.P.,K.D.K.A.,R.H.,N.M.B.andA.P.H.;datacuration,T.P.H.and K.D.K.A.;writing—originaldraftpreparation,T.P.H.;writing—reviewandediting,K.D.K.A.,L.D., R.H.,S.J.,S.M.,R.S.,K.A.E.P.,N.M.B.andA.P.H.;projectadministration,R.H.,N.M.B.andA.P.H.; fundingacquisition,K.A.E.P.,K.D.K.A.,R.H.,N.M.B.andA.P.H.Allauthorshavereadandagreedto thepublishedversionofthemanuscript.

Funding: ThisresearchwasfundedbyaNationalHealth&MedicalResearchCouncil(NHMRC) grant(#113672)aspartoftheCAPITOLProject.Thestudyfunderhadnoroleinthestudydesign, collection,analysis,orinterpretationofthedata,inwritingthereport,orinthedecisiontosubmitthe articleforpublication.Thecontentsofthisarticlearetheresponsibilityoftheauthorsanddonot reflecttheviewsoftheNHMRC.

InstitutionalReviewBoardStatement: Notapplicable.

InformedConsentStatement: Notapplicable.

DataAvailabilityStatement: Notapplicable.

Acknowledgments: TheauthorswishtothanktheUniversityofTasmanialibrarystaffforassistance withliteraturesearchstrategies.

ConflictsofInterest: Theauthorsdeclarenoconflictofinterest.

References

1. AIHW.FoodandNutrition.Availableonline: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports-data/behaviours-risk-factors/food-nutrition/ overview (accessedon14August2022).

2. FAO;IFAD;UNICEF;WFP;WHO. TheStateofFoodSecurityandNutritionintheWorld2022.RepurposingFoodandAgricultural PoliciestoMakeHealthyDietsMoreAffordable;FAO:Rome,Italy,2022.

3. FAO. DeclarationoftheWorldSummitonFoodSecurity;FAO:Rome,Italy,2009.

4. Andress,L.;Fitch,C.Jugglingthefivedimensionsoffoodaccess:Perceptionsofrurallowincomeresidents. Appetite 2016, 105, 151–155.[CrossRef][PubMed]

5. Friel,S.;Hattersley,L.;Ford,L. EvidenceReview:AddressingtheSocialDeterminantsofInequitiesinHealthyEating;TheAustralian NationalUniversity:Canberra,Australia,2015.

6. Vilar-Compte,M.;Burrola-Mendez,S.;Lozano-Marrufo,A.;Ferre-Eguiluz,I.;Flores,D.;Gaitan-Rossi,P.;Teruel,G.;PerezEscamilla,R.Urbanpovertyandnutritionchallengesassociatedwithaccessibilitytoahealthydiet:Aglobalsystematicliterature review. Int.J.EquityHealth 2021, 20,40.[CrossRef][PubMed]

7. Guitart,D.;Pickering,C.;Byrne,J.Pastresultsandfuturedirectionsinurbancommunitygardensresearch. UrbanFor.Urban Green. 2012, 11,364–373.[CrossRef]

8. Kingsley,J.;Bailey,A.;Torabi,N.;Zardo,P.;Mavoa,S.;Gray,T.;Tracey,D.;Pettitt,P.;Zajac,N.;Foenander,E.ASystematicReview ProtocolInvestigatingCommunityGardeningImpactMeasures. Int.J.Environ.Res.PublicHealth 2019, 16,3430.[CrossRef] [PubMed]

9. Gregis,A.;Ghisalberti,C.;Sciascia,S.;Sottile,F.;Peano,C.CommunityGardenInitiativesAddressingHealthandWell-Being Outcomes:ASystematicReviewofInfodemiologyAspects,Outcomes,andTargetPopulations. Int.J.Environ.Res.PublicHealth 2021, 18,1943.[CrossRef][PubMed]

10. Ohly,H.;Gentry,S.;Wigglesworth,R.;Bethel,A.;Lovell,R.;Garside,R.Asystematicreviewofthehealthandwell-beingimpacts ofschoolgardening:Synthesisofquantitativeandqualitativeevidence. BMCPublicHealth 2016, 16,286.[CrossRef]

11. Berezowitz,C.K.;BontragerYoder,A.B.;Schoeller,D.A.SchoolGardensEnhanceAcademicPerformanceandDietaryOutcomes inChildren. J.Sch.Health 2015, 85,508–518.[CrossRef][PubMed]

12. Davis,J.N.;Spaniol,M.R.;Somerset,S.Sustenanceandsustainability:Maximizingtheimpactofschoolgardensonhealth outcomes. PublicHealthNutr. 2015, 18,2358–2367.[CrossRef]

13. Savoie-Roskos,M.R.;Wengreen,H.;Durward,C.IncreasingFruitandVegetableIntakeamongChildrenandYouththrough Gardening-BasedInterventions:ASystematicReview. J.Acad.Nutr.Diet. 2017, 117,240–250.[CrossRef]

14. Charlton,K.;Comerford,T.;Deavin,N.;Walton,K.Characteristicsofsuccessfulprimaryschool-basedexperientialnutrition programmes:Asystematicliteraturereview. PublicHealthNutr. 2021, 24,4642–4662.[CrossRef]

15. Rochira,A.;Tedesco,D.;Ubiali,A.;Fantini,M.P.;Gori,D.SchoolGardeningActivitiesAimedatObesityPreventionImprove BodyMassIndexandWaistCircumferenceParametersinSchool-AgedChildren:ASystematicReviewandMeta-Analysis. Child. Obes. 2020, 16,154–173.[CrossRef][PubMed]

16. Ozer,E.J.Theeffectsofschoolgardensonstudentsandschools:Conceptualizationandconsiderationsformaximizinghealthy development. HealthEduc.Behav. 2007, 34,846–863.[CrossRef][PubMed]

17. Qi,Y.;Hamzah,S.H.;Gu,E.;Wang,H.;Xi,Y.;Sun,M.;Rong,S.;Lin,Q.IsSchoolGardeningCombinedwithPhysicalActivity InterventionEffectiveforImprovingChildhoodObesity?ASystematicReviewandMeta-Analysis. Nutrients 2021, 13,2605. [CrossRef][PubMed]

18. Varman,S.D.;Cliff,D.P.;Jones,R.A.;Hammersley,M.L.;Zhang,Z.;Charlton,K.;Kelly,B.ExperientialLearningInterventions andHealthyEatingOutcomesinChildren:ASystematicLiteratureReview. Int.J.Environ.Res.PublicHealth 2021, 18,10824. [CrossRef][PubMed]

19. Pawson,R.;Greenhalgh,T.;Harvey,G.;Walshe,K.Realistreview—Anewmethodofsystematicreviewdesignedforcomplex policyinterventions. J.HealthServ.Res.Policy 2005, 10 (Suppl.1),21–34.[CrossRef][PubMed]

20. Popay,J.;Roberts,H.;Sowden,A.;Petticrew,M.;Arai,L.;Rodgers,M.;Britten,N.;Roen,K.;Duffy,S. GuidanceontheConductof NarrativeSynthesisinSystematicReviews.AProductfromtheESRCMethodsProgramme;LancasterUniversity:Lancaster,UK,2006. [CrossRef]

21. Noyes,J.;Lewin,S.Supplementalguidanceonselectingamethodofqualitativeevidencesynthesis,andintegrating qualitativeevidencewithCochraneinterventionreviews.In SupplementaryGuidanceforInclusionofQualitativeResearchinCochraneSystematicReviewsofInterventionsVersion;UpdatedAugust2011;Noyes,J.H.K.,Harden,A.,Harris,J.,Lewin,S.,Lockwood,C.,CochraneCollaborationQualitativeMethodsGroup,Eds.;2011.Availableonline: https://kuleuven.limo.libis.be/discovery/fulldisplay?docid=lirias1794168&context=SearchWebhook&vid=32KUL_KUL: Lirias&search_scope=lirias_profile&adaptor=SearchWebhook&tab=LIRIAS&query=any,contains,lirias1794168 (accessedon 13January2023).

22. Tranfield,D.;Denyer,D.;Smart,P.TowardsaMethodologyforDevelopingEvidence-InformedManagementKnowledgeby MeansofSystematicReview. Br.J.Manag. 2003, 14,207–222.[CrossRef]

23. Page,M.J.;McKenzie,J.E.;Bossuyt,P.M.;Boutron,I.;Hoffmann,T.C.;Mulrow,C.D.;Shamseer,L.;Tetzlaff,J.M.;Akl,E.A.; Brennan,S.E.;etal.ThePRISMA2020statement:Anupdatedguidelineforreportingsystematicreviews. BMJ 2021, 372,n71. [CrossRef]

24. Hoffmann,T.C.;Glasziou,P.P.;Boutron,I.;Milne,R.;Perera,R.;Moher,D.;Altman,D.G.;Barbour,V.;Macdonald,H.;Johnston, M.;etal.Betterreportingofinterventions:Templateforinterventiondescriptionandreplication(TIDieR)checklistandguide. BMJ 2014, 348,g1687.[CrossRef]

25. Jaenke,R.L.;Collins,C.E.;Morgan,P.J.;Lubans,D.R.;Saunders,K.L.;Warren,J.M.Theimpactofaschoolgardenandcooking programonboys’andgirls’fruitandvegetablepreferences,tasterating,andintake. HealthEduc.Behav. 2012, 39,131–141. [CrossRef]

26. Morgan,P.J.;Warren,J.M.;Lubans,D.R.;Saunders,K.L.;Quick,G.I.;Collins,C.E.Theimpactofnutritioneducationwithand withoutaschoolgardenonknowledge,vegetableintakeandpreferencesandqualityofschoollifeamongprimary-school students. PublicHealthNutr. 2010, 13,1931–1940.[CrossRef]

27. Cutter-Mackenzie,A.MulticulturalSchoolGardens:CreatingEngagingGardenSpacesinLearningaboutLanguage,Culture, andEnvironment. Can.J.Environ.Educ. 2009, 14,122–135.

28. Viola,A.EvaluationoftheOutreachSchoolGardenProject:BuildingthecapacityoftwoIndigenousremoteschoolcommunities tointegratenutritionintothecoreschoolcurriculum. HealthPromot.J.Aust. 2006, 17,233–239.[CrossRef][PubMed]

29. Block,K.;Gibbs,L.;Staiger,P.K.;Gold,L.;Johnson,B.;Macfarlane,S.;Long,C.;Townsend,M.Growingcommunity:Theimpact oftheStephanieAlexanderKitchenGardenProgramonthesocialandlearningenvironmentinprimaryschools. HealthEduc. Behav. 2012, 39,419–432.[CrossRef][PubMed]

30. Gibbs,L.;Staiger,P.K.;Johnson,B.;Block,K.;Macfarlane,S.;Gold,L.;Kulas,J.;Townsend,M.;Long,C.;Ukoumunne,O. Expandingchildren’sfoodexperiences:Theimpactofaschool-basedkitchengardenprogram. J.Nutr.Educ.Behav. 2013, 45, 137–146.[CrossRef]

31. Henryks,J.Changingthemenu:Rediscoveringingredientsforasuccessfulvolunteerexperienceinschoolkitchengardens. Local Environ. 2011, 16,569–583.[CrossRef]

32. Townsend,M.;Gibbs,L.;Macfarlane,S.;Block,K.;Staiger,P.;Gold,L.;Johnson,B.;Long,C.VolunteeringinaSchoolKitchen GardenProgram:CookingUpConfidence,Capabilities,andConnections! VOLUNTASInt.J.Volunt.NonprofitOrgan. 2012, 25, 225–247.[CrossRef]

33. Lakin,L.;Littledyke,M.Healthpromotingschools:Integratedpracticestodevelopcriticalthinkingandhealthylifestylesthrough farming,growingandhealthyeating. Int.J.Consum.Stud. 2008, 32,253–259.[CrossRef]

34. Christian,M.S.;Evans,C.E.L.;Nykjaer,C.;Hancock,N.;Cade,J.E.Evaluationoftheimpactofaschoolgardeninginterventionon children’sfruitandvegetableintake:Arandomisedcontrolledtrial. Int.J.Behav.Nutr.Phys.Act 2014, 11,99.[CrossRef]

35. Hutchinson,J.;Christian,M.S.;Evans,C.E.;Nykjaer,C.;Hancock,N.;Cade,J.E.Evaluationoftheimpactofschoolgardening interventionsonchildren’sknowledgeofandattitudestowardsfruitandvegetables.Aclusterrandomisedcontrolledtrial. Appetite 2015, 91,405–414.[CrossRef]

36. Heim,S.;Stang,J.;Ireland,M.Agardenpilotprojectenhancesfruitandvegetableconsumptionamongchildren. J.Am.Diet. Assoc. 2009, 109,1220–1226.[CrossRef]

37. Kararo,M.J.;Orvis,K.S.;Knobloch,N.A.EatYourWaytoBetterHealth:EvaluatingaGarden-basedNutritionProgramforYouth. HortTechnology 2016, 26,663–668.[CrossRef]

38. Wright,W.;Rowell,L.ExaminingtheEffectofGardeningonVegetableConsumptionAmongYouthinKindergartenthrough FifthGrade. Wis.Med.J. 2010, 109,125–129.

39. Meinen,A.;Friese,B.;Wright,W.;Carrel,A.YouthGardensIncreaseHealthyBehaviorsinYoungChildren. J.Hunger.Environ. Nutr. 2012, 7,192–204.[CrossRef]

40. Castro,D.C.;Samuels,M.;Harman,A.E.Growinghealthykids:Acommunitygarden-basedobesitypreventionprogram. Am.J. Prev.Med. 2013, 44,S193–S199.[CrossRef][PubMed]

41. Hollar,D.;Lombardo,M.;Lopez-Mitnik,G.;Hollar,T.L.;Almon,M.;Agaston,A.S.;Messiah,S.E.EffectiveMulti-level,Multisector,School-basedObesityPreventionProgrammingImprovesWeight,BloodPressure,andAcademicPerformance,Especially amongLow-Income,MinorityChildren. J.HealthCarePoorUnderserved 2010, 21,93–108.[CrossRef][PubMed]

42. Wells,N.M.;Myers,B.M.;Henderson,C.R.,Jr.Schoolgardensandphysicalactivity:Arandomizedcontrolledtrialoflow-income elementaryschools. Prev.Med. 2014, 69 (Suppl.1),S27–S33.[CrossRef][PubMed]

43. Koch,S.;Waliczek,T.M.;Zajicek,J.M.TheEffectofaSummerGardenProgramontheNutritionalKnowledge,Attitudes,and BehaviorsofChildren. HortTechnology 2006, 16,620–625.[CrossRef]

44. Davis,J.N.;Ventura,E.E.;Cook,L.T.;Gyllenhammer,L.E.;Gatto,N.M.LASprouts:Agardening,nutrition,andcooking interventionforLatinoyouthimprovesdietandreducesobesity. J.Am.Diet.Assoc. 2011, 111,1224–1230.[CrossRef]

45. Davis,J.N.;Martinez,L.C.;Spruijt-Metz,D.;Gatto,N.M.LASprouts:A12-WeekGardening,Nutrition,andCookingRandomized ControlTrialImprovesDeterminantsofDietaryBehaviors. J.Nutr.Educ.Behav. 2016, 48,2–11.e1.[CrossRef]

46. Gatto,N.M.;Ventura,E.E.;Cook,L.T.;Gyllenhammer,L.E.;Davis,J.N.LASprouts:Agarden-basednutritioninterventionpilot programinfluencesmotivationandpreferencesforfruitsandvegetablesinLatinoyouth. J.Acad.Nutr.Diet. 2012, 112,913–920. [CrossRef]

47. Gatto,N.M.;Martinez,L.C.;Spruijt-Metz,D.;Davis,J.N.LAsproutsrandomizedcontrollednutrition,cookingandgardening programmereducesobesityandmetabolicriskinHispanic/Latinoyouth. Pediatr.Obes. 2017, 12,28–37.[CrossRef][PubMed]

48. Landry,M.J.;Markowitz,A.K.;Asigbee,F.M.;Gatto,N.M.;Spruijt-Metz,D.;Davis,J.N.CookingandGardeningBehaviorsand ImprovementsinDietaryIntakeinHispanic/LatinoYouth. Child.Obes. 2019, 15,262–270.[CrossRef]

49. Alexander,J.;North,M.;Hendren,D.K.MasterGardenerClassroomGardenProject:AnEvaluationoftheBenefitstoChildren. Child.Environ. 1995, 2,256–263.

50. Lineberger,S.E.;Zajicek,J.M.SchoolGardens:CanaHands-onTeachingToolAffectStudents’AttitudesandBehaviorsRegarding FruitandVegetables. HortTechnology 2000, 10,593–597.[CrossRef]

51. McAleese,J.D.;Rankin,L.L.Garden-basednutritioneducationaffectsfruitandvegetableconsumptioninsixth-gradeadolescents. J.Am.Diet.Assoc. 2007, 107,662–665.[CrossRef]

52. Scherr,R.E.;Linnell,J.D.;Dharmar,M.;Beccarelli,L.M.;Bergman,J.J.;Briggs,M.;Brian,K.M.;Feenstra,G.;Hillhouse,J.C.;Keen, C.L.;etal.AMulticomponent,School-BasedIntervention,theShapingHealthyChoicesProgram,ImprovesNutrition-Related Outcomes. J.Nutr.Educ.Behav. 2017, 49,368–379.e1.[CrossRef]

53. Evans,A.;Ranjit,N.;Rutledge,R.;Medina,J.;Jennings,R.;Smiley,A.;Stigler,M.;Hoelscher,D.Exposuretomultiplecomponents ofagarden-basedinterventionformiddleschoolstudentsincreasesfruitandvegetableconsumption. HealthPromot.Pract. 2012, 13,608–616.[CrossRef][PubMed]

54. Davis,J.N.;Perez,A.;Asigbee,F.M.;Landry,M.J.;Vandyousefi,S.;Ghaddar,R.;Hoover,A.;Jeans,M.;Nikah,K.;Fischer,B.;etal. School-basedgardening,cookingandnutritioninterventionincreasedvegetableintakebutdidnotreduceBMI:Texassprouts—A clusterrandomizedcontrolledtrial. Int.J.Behav.Nutr.Phys.Act. 2021, 18,18.[CrossRef][PubMed]

55. vandenBerg,A.;Warren,J.L.;McIntosh,A.;Hoelscher,D.;Ory,M.G.;Jovanovic,C.;Lopez,M.;Whittlesey,L.;Kirk,A.;Walton, C.;etal.ImpactofaGardeningandPhysicalActivityInterventioninTitle1Schools:TheTGEGStudy. Child.Obes. 2020, 16, S44–S54.[CrossRef]

56. Namenek-Brouwer,R.J.;Benjamin-Neelon,S.E.WatchMeGrow:Agarden-basedpilotinterventiontoincreasevegetableand fruitintakeinpreschoolers. BMCPublicHealth 2013, 13,363.[CrossRef]

57. Bowker,R.;Tearle,P.Gardeningasalearningenvironment:Astudyofchildren’sperceptionsandunderstandingofschool gardensaspartofaninternationalproject. Learn.Environ.Res. 2007, 10,83–100.[CrossRef]

58. Schreinemachers,P.;Rai,B.B.;Dorji,D.;Chen,H.-p.;Dukpa,T.;Thinley,N.;Sherpa,P.L.;Yang,R.-Y.SchoolgardeninginBhutan: Evaluatingoutcomesandimpact. FoodSecur. 2017, 9,635–648.[CrossRef]

59. Schreinemachers,P.;Bhattarai,D.R.;Subedi,G.D.;Acharya,T.P.;Chen,H.-p.;Yang,R.-y.;Kashichhawa,N.K.;Dhungana,U.; Luther,G.C.;Mecozzi,M.ImpactofschoolgardensinNepal:Aclusterrandomisedcontrolledtrial. J.Dev.Eff. 2017, 9,329–343. [CrossRef]

60. Bronfenbrenner,U.EcologicalSystemsTheory.In SixTheoriesofChildDevelopment:RevisedFormulationsandCurrentIdeas;Vasta, R.,Ed.;JessicaKingsleyPublishers:London,UK,1992.

61. Mann,J.;Gray,T.;Truong,S.;Brymer,E.;Passy,R.;Ho,S.;Sahlberg,P.;Ward,K.;Bentsen,P.;Curry,C.;etal.GettingOutof theClassroomandIntoNature:ASystematicReviewofNature-SpecificOutdoorLearningonSchoolChildren’sLearningand Development. Front.PublicHealth 2022, 10,877058.[CrossRef][PubMed]

62. Ornelas,I.J.;Rudd,K.;Bishop,S.;Deschenie,D.;Brown,E.;Lombard,K.;Beresford,S.A.A.EngagingSchoolandFamilyin NavajoGardeningforHealth:DevelopmentoftheYeegoInterventiontoPromoteHealthyEatingamongNavajoChildren. Health Behav.PolicyRev. 2021, 8,212–222.[CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’sNote: Thestatements,opinionsanddatacontainedinallpublicationsaresolelythoseoftheindividual author(s)andcontributor(s)andnotofMDPIand/ortheeditor(s).MDPIand/ortheeditor(s)disclaimresponsibilityforanyinjuryto peopleorpropertyresultingfromanyideas,methods,instructionsorproductsreferredtointhecontent.