The Gate

Passage by Fire

The Gate

Passage by Fire

The Gate

Auguste Rodin George Grosz Boris Lurie

A curatorial statement by Akim Monet

The Gates of Hell anchors this exhibition not merely as a sculptural masterpiece by Auguste Rodin, but as a prophetic architecture of human collapse. Conceived in the late 19th century, on the threshold of Europe’s descent into mechanized warfare, Rodin’s tormented figures—twisting, falling, trapped in their own psychic gravitation— offer no redemption, no glory. They are the precursors to a century of trenches, camps, and ruins. In Rodin’s vision, hell is not otherworldly—it is of our making.

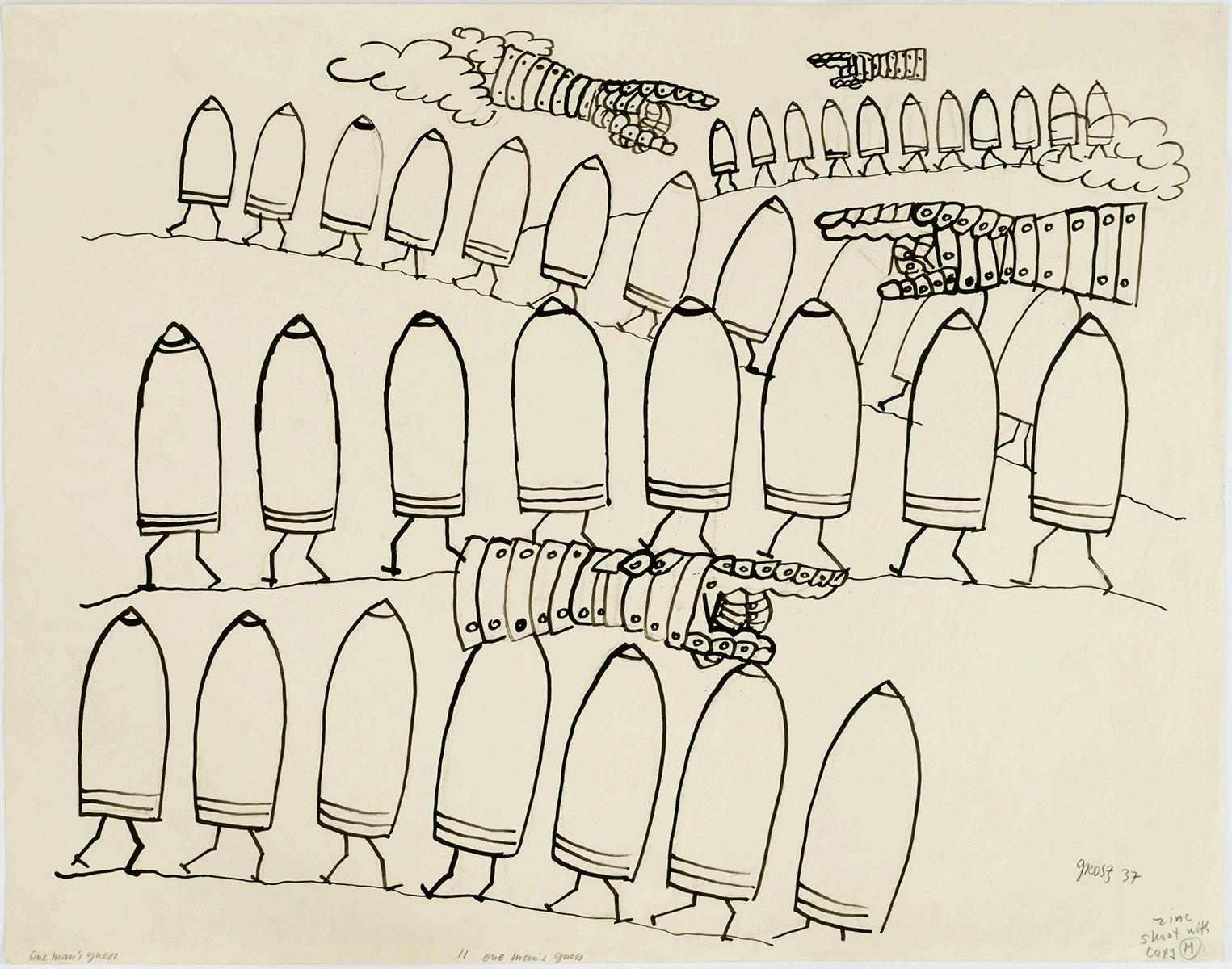

In the wake of that descent, George Grosz emerges from the debris of Weimar Germany, his ink slicing through the hypocrisy of a society that glamorized war even as it limped from its wounds. With savage wit and unsparing clarity, Grosz chronicled the rise of fascism and the banality of evil, exposing the grotesque and complicit faces of modern power. He foresaw what happens when democratic institutions rot from within, and art became his means of holding a cracked mirror to a fractured world.

Then comes Boris Lurie—Holocaust survivor, exile, and founder of the NO!art movement—whose work refuses aesthetic consolation. For Lurie, memory is a battleground. His raw collages and visual indictments confront not only the horrors of genocide but the way trauma is repackaged, commercialized, and sanitized. He rejected the hollowing of history, insisting that to honor memory is not to preserve it in amber, but to activate it against injustice wherever it reappears.

The collective refusal embodied by Rodin, Grosz, and Lurie reverberates into the present. Their works whisper, wail, and scream that art must not look away. Just as Rodin refused to mythologize pain, Grosz refused to laugh it away, and Lurie refused to forget it, we too are called to bear witness—not only to the suffering of the past but to the cries of the living.

This exhibition does not seek to moralize. Rather, it assembles fragments—of flesh, form, and fury—into a shared vocabulary of dissent. To present it in the fall—a season of reckoning, of renewal, of remembering—feels especially urgent. It is the time of Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur. It is the time, too, when the flames of Kristallnacht were first lit.

The Gate invites viewers to walk through these thresholds not toward damnation, but toward recognition: that the inferno is not elsewhere. It is here. It is now. And perhaps, through that recognition, we might yet reclaim our humanity.

Boris LURIE

Auguste RODIN

Raymond DIOR

Raymond Alexandre Jules Dior (1899–1966), elder brother of fashion designer Christian Dior, was a journalist known for his radical political leanings. During the interwar years, he edited several provocative publications, including the September 1936 special issue of Le Crapouillot titled “Les Juifs.” Now considered a rare collectible, the issue is a stark historical artifact. While framed as cultural reportage, it reflects how antisemitism was intellectualized and circulated in 1930s France—legitimized through the veneer of journalism well before the Holocaust began.

George GROSZ

Boris LURIE

Auguste RODIN

George GROSZ

Boris LURIE

Boris LURIE

Auguste RODIN

Boris LURIE

George GROSZ

Boris LURIE

Auguste RODIN

George GROSZ

Boris LURIE

Boris LURIE

Auguste RODIN

George GROSZ

Auguste RODIN

Boris LURIE

George GROSZ

Dr. Philipp HAEUSER

German Roman Catholic priest and a supporter of National Socialism. He is notable for his writings, including a book titled "Jud und Christ oder Wem gebührt die Weltherrschaft?" (Jew and Christian or Who Shall Rule the World?) published in 1923.