THE SPIRIT OF DEDICATION.

Commitment that’s one of a kind. Agribusiness solutions you trust.

•Digital tools for fast, secure payroll and payments

•Business checking, savings and credit card solutions

•International trade expertise and financial guidance

•Agriculture term loans and open lines of credit

It’s just one of countless examples of determination and a drive to survive, a combination of necessity and knowledge that’s helped the family farm reach its sesquicentennial milestone, no easy task in an industry whose fortunes can change on the whims of the weather and world markets.

It’s no wonder the family wanted to celebrate.

The 150th birthday bash featured a hog roast, Bingo, games of corn hole, fishing, paddle boating on the lake, yard games, Euchre, shooting hoops onto a hay baler, and a petting zoo from P&C Little Rascals of Chadwick.

“We decided to have a day of fun,” Jeanie said. “Our family wanted to celebrate our farm being in the family for 150 years. It was an idea of wanting to celebrate, so we decided to have a party,” and the kids were more than happy to give Mom and Dad a celebration to remember. “All five of our kids had been working really hard at it,” Jeanie said, “And our fourth generation — Nancy, Larry and I — did the least amount of work.”

Only a handful of farms in Carroll County have made it to the 150-year mark (read the story on page 30 to learn about another sesquicentennial farm in the county, Lamoreux Family Farms), and it is the first among farms in York Township, which comprises of the area around Thomson, Argo Fay and Ideal Corners.

aesthetics, it served a practical purpose too: when a chicken house caught fire, the water from the pond was used to battle the blaze.

“There was no rural fire department,” Green said, “so Dad put in the pond and it was a bucket brigade.”

Like the farm itself, the stream that gave it its name has stood the test of time, carrying water since the Smiths have owned the farm, though nature almost turned a cold spring into dry one — the most recent time was during the summer drought of 1988. What little water it did have that summer had to be prioritized, with the livestock getting first dibs, Judd recalled.

The pond and stream are the farm’s signature sights, Jeanie said, and the water once gave Julie an idea as a teenager.

Go to facebook.com/coldspring.farms to learn more about Coldspring Farms in rural Thomson. Coldspring Farms' sweet corn is sold in July and August at Ray's Time Out bar and grill, 1815 Manufacturing Drive in Clinton, Iowa. Cost is $4 for a dozen ears. Check the website for more information.

When their sesquicentennial farm sign comes from the Illinois Department of Agriculture, they’ll swap it with the centennial sign posted near the farm’s windmill, which is one of the first things people see as they travel west on the gravel road toward the farm. Passersby can also get a glimpse of the nearby pond before the hilly road dips down and it disappears from sight.

The pond was built in the mid-1940s, around the same time as Green’s house, fed by water from the stream. It was rehabilitated in 2014. The pond wasn’t just something for

“One of the things that I remember a lot about this farm growing up is thinking of Julie, and her always having friends over and they would love the water here,” Judd said. “Julie thought about it and told me about this idea of her bottling the water.

“[I said,] ‘No one would ever buy bottled water,’” he added with a laugh.

People have, however, bought ears of corn that the Smiths grow. For the past few years in July and August, they load up a trailer at Ray’s Time Out bar and grill in Clinton, Iowa, about 10 miles away, selling bundles for $4. They’ve shared stories of life on the farm with their customers, some of which have become well-acquainted with them enough to celebrate the family’s milestone achievement with them.

“It’s a once-in-a-lifetime event,” Julie said. “Many of us will probably never see the next 50-year mark.”

But if the past is any indication of the future, there’ll still be Smiths around to celebrate the farm’s bicentennial. After all, hope isn’t the only thing that springs eternal, Coldpsring has become practically eternal, too. n

Cody Cutter can be reached at 815-632-2532 or ccutter@shawmedia.com.

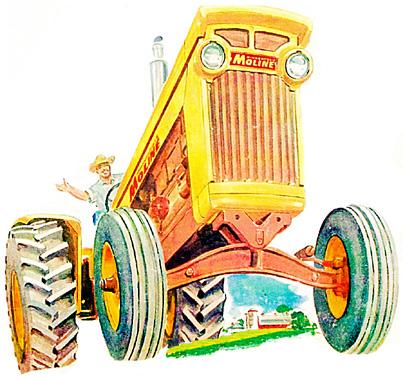

ichael Jahn remembers visiting his grandfather’s garage and MinneapolisMoline dealership in Lee Center as a kid, marveling at the tractors and equipment brought there for repair, and the latest models of Prairie Gold gleaming in the sun.

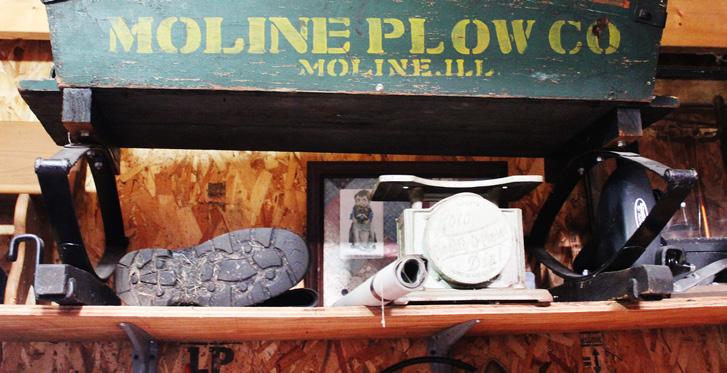

Jahn never got to be a farmer himself, but seeing all that MinniMo equipment as a boy gave him a deep appreciation for not only the machines and the company that made them, but one of its predecessors: the Moline Plow Company.

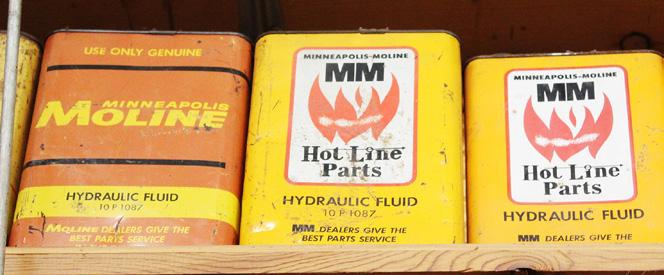

Over the past 30 years, Jahn has built up a collection of both Moline and Minneapolis-Moline memorabilia: machines, catalogs, advertisements, wrenches made specifically by the companies, and a whole lot more.

JAHN cont’d to page 14

An occasional feature of Northern Illinois Ag Mag looking at well-oiled farm machines and the people whose elbow grease keeps ‘em going

Jahn got hooked on Minnie Mo’s at his grandpa’s shop, Johnie’s Garage, in Lee Center. Though the business has long been closed, the building remains, with a Minneapolis-Moline sign hanging on front as a nod to its history. Jahn honors his grandfather with a 1954 Ford F-350 that he owns, a truck his grandfather would have had in the 1950s.

JAHN cont’d from page 12

You don’t see many Minneapolis-Moline tractors working on farms today, but they’re still out there — parked at tractor shows, parading in tractor drives, powering through tractor pulls — and they remain popular with collectors. Even harder to find are working pieces from the Moline Plow Company. Jahn would like to see more — or at least see the ones that do remain stick around. That’s why he’s doing his part to help preserve the history of a company that once rivaled John Deere for Quad Cities ag machine supremacy until the Great Depression, as well as its successor, whose Prairie Gold powerhouses were once plentiful around eastern Lee County.

Jahn’s grandfather Louie, a German immigrant, sold Minneapolis-Moline equipment for 25 years; the garage continues to stand in what was Lee Center’s small downtown area (today little more than the village Post Office), with replica signs hanging on the building, a reminder of its glory days, and Jahn still calls the community home.

JAHN cont’d to page 15

“My grandfather was a dealer here,” Jahn said. “My interest started about 30 years ago, but he was long gone and the building was all closed up and there wasn’t much left. Being from a farm area, of course, you’re naturally around old equipment, and I’ve always liked old things. So I started out trying to put together a lineup of tractors and machinery that he would have handled.”

Del Monte Foods plants in Rochelle and Mendota provided work for many Lee County residents, and for several decades — especially during the 1950s’ post-war economic boom — the company exclusively used Minneapolis-Moline tractors and equipment, Jahn said. When Del Monte upgraded their equipment, it sold its old ones to employees who would use them on their own farms, with many making their way to Louie’s garage from time to time.

The first tractor in Jahn’s collection came unexpectedly, while he traveling near Harvard in McHenry County. It was a 1950 Minneapolis-Moline R-series that had just begun its search for a new owner, and it didn’t have to look long.

“The farmer had just got off of it and put up the ‘For Sale’ sign as we went by,” Jahn said. “I said [to my wife], ‘Turn around, we’re going back!’”

Jahn has about a dozen working machines from both Moline Plow Company and Minneapolis-Moline, as well as a few more in varying states of repair. As his collection grew, he became deeply interested in the Moline end of the hyphen, especially with the city being only about 60 miles west of Lee Center home.

The Moline Plow Company began in 1865 and merged with the Minneapolis Steel Machinery Company and the Minneapolis Threshing Machine Company in 1929. Two of Moline’s most notable machines are the Flying Dutchman plow and the Universal tractor, and Jahn has one of each in his collection: an 1884 plow (a first-year model) and 1918 tractor.

The Universal design was acquired after Moline bought the Universal Tractor Company of Columbus, Ohio, in 1915; the design, akin to riding a horse, was designed to improve the cultivation of row crops. Universals were made until 1923, and they were manufactured at a plant in Rock Island that would later become the site of International Harvester’s Farmall Works. Another tractor in Jahn’s collection is a 1926 Twin City 17-28, made by Minneapolis Steel Machinery. When it merged with Moline and Minneapolis Threshing, the Twin City tractors became the model for future Minneapolis-Moline machines.

The old Flying Dutchman plows were made for a better draft that was much easier for the horses to work with; they were the first three-wheel sulkies on the market. The tale of the Flying Dutchman — one of toughness and perseverance on the seas, Jahn said — became a theme and mascot for the Moline Plow Company. Two-and-a-half-foot thin, zinc-cast statues of a Flying Dutchman adorned the desks and offices of company executives. They are one of the rarest pieces of Moline memorabilia out there — but Jahn managed to find one in Ohio about 20 years ago and restored it.

JAHN cont’d to page 16

Big and small, common and rare, Jahn boasts an impressive collection of pieces from Minneapolis-Moline and the Moline Plow Company. He started collecting tractors and machinery that his grandpa would have handled in his shop, and it just kept on growing from there.

The first Minnie-Mo tractor in Jahn's collection: a 1950 Model R, purchased from a farmer in rural Harvard in McHenry County.

Before Jahn acquired this buggy seat, it spent years on display at the Moline Dispatch newspaper. JAHN cont’d from page 15

This Moline Plow Company Flying Dutchman is believed to be one of only two such plows left in existence from its first year, in 1884.

“As the years went on, I started to develop an interest in just the Moline Plow Company, which was one of the original three companies,” Jahn said. “It was one of the largest agricultural manufacturing companies in the world at one time. They had a full line of machinery, other than tractors.”

Jahn became a member of a Minneapolis-Moline collector’s club, and travels throughout the Midwest to shows in search of items to add to his collection. He also has displayed some of his collection at regional shows, such as the Living History Antique Equipment Association show in Franklin Grove, and the Antique Engine and Tractor Association show in Geneseo. He also took some of his memorabilia to a John Deere show a couple of years ago when its Quad Citybased collectors organization held a show honoring the various ag machine companies in Moline and Rock Island.

“You get to know other collectors, but you also get to know other areas where there would be Moline Plow Company items,” Jahn said. “The Midwest is all good, but you can get out in the northwest, too, up in Washington or Montana, and Moline Plow Company had a distributorship out there. In the south, they were really strong, and even in the east.”

JAHN cont’d to page 17

A Moline Plow Co. hit-and-miss.

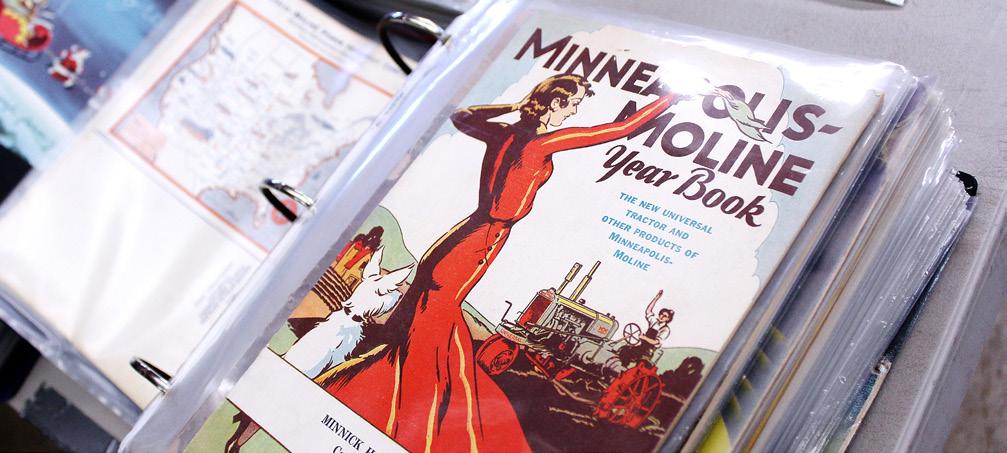

Catalogs, brochures, trade newspapers and ads make up the jewels of Jahn’s collection, the oldest of which are from the 1870s. One method of attracting customers to Moline Plow Company’s products in the early days was the use of colorful ads, during a time when color printing wasn’t as common as it is today. Many of the pieces till retain their color, even after 100 years, and Jahn takes special care to keep them that way.

“It was better to have this color in the early days,” Jahn said. “They were known for using a lot of color in their early catalogs, promotional pieces and sales brochures. That may not sound like much, but in today’s collector world having a lot of color with something that was in 1880 is big. They were very alive and vibrant with them. That’s something very interesting with collecting Moline Plow Company stuff.”

tions learn about and appreciate the hard work that went into farming, what it took to make the machines, and the elbow grease that went into the care of equipment in the days before modern technology took hold — and who knows: Maybe some of them will get hooked on the machines like he did, and they’ll want to breathe new life into some rusty gold.

“I like to hope that they realize the design and manufacturing of this old equipment wasn’t on a computer,” Jahn said. “People actually sat down to develop the equipment, and a lot of it in the old day was by trial and error. They would go into the shop and make a piece and go out there and try it to see if it works. If not, they bring it back in for redevelopment.

Just the appreciation of what it took to manufacture in the old days is really something when you think about it.”

Got a classic that’s still crankin’?

Do you have a classic tractor that looks as good as new? Or is your antique power rough, rusted , and ready to go?

Either way, we’d like to share your story with our readers in Ag Mag’s “Still Crankin’ After All These Years,” a feature that celebrates the people who keep farm history alive through their classic tractors.

Preserving the heritage and lessons of farm life from century ago is something Jahn takes great pride in, and goes beyond just his collection. He’s also a board member of the Living History Antique Equipment Association, which has an annual show Aug. 3-4 in Franklin Grove. In that role, he helps organize the show’s activities and displays, and he also runs the Association’s unrestored, 1870s flour mill machine, a task that leaves him looking like a friendly ghost, covered in white powder as he happily goes about his business of showing attendees of all ages how the mill works.

Jahn hopes the shows will help younger genera-

Jahn’s mission to preserve and preach the importance of local farm history in his own way adds to the rich heritage of the Lee County farming scene, one with several sesquicentennial farms and active FFA and 4-H organizations that all play their part in helping feed the world while strengthening local family roots.

“I’m so lucky to have pieces that are one of a kind,” Jahn said. “Being from this little town here, I always had an interest in local history. With my grandfather having the tractor business, it was just natural to have that interest to begin with.” n

Cody Cutter can be reached at 815-632-2532 or ccutter@shawmedia.com.

These are the people who will work on their tractor until to the cows come home. They’ll swap stories and swap parts. They’ll scour websites and catalogs and tractor shows to hunt down that hard-tofind piece for their project. They’ll do what it takes to get that tractor to go the extra mile — and when they get those machines to pop and sputter and roar to life, it’s music to their ears.

Whether you’ve rebuilt or restored a ride, or you’ve got a project in progress, drop us a line and let us know about it, and we may just share your story in a future issue of Ag Mag. Email rschrader@ saukvalley.com.

n an age when technology and tomorrow go hand-inhand, pushing us ahead faster and faster, there’s still a desire to pull back, slow down, and appreciate yesterday. That’s true in the world of farming as much as anywhere else.

Computers in combines, GPS looking over farmers’ shoulders, eyes in the sky mapping out crop rows and eyes on weed sprayers telling them where to spray with pinpoint precision.

Where did the days go when hands and horse power — with real horses — got the job done?

Mary Lynn Sondgeroth (left) and Dar Wujak of the Breaking the Prairie Museum in Mendota help share the stories of farm history from the Bureau, La Salle and Lee county area through artifacts and machines from a century ago.

They’re at the Breaking the Prairie Museum in Mendota, where farm history isn’t gathering dust and dirt in a sagging old barn, but put on display for people of all ages to see, enjoy, and learn from.

Artifacts, pictures and personal stories housed in a barn-style building tell the tales of a time when farming was more about toil than technology.

MUSEUM cont’d to page 20

The museum is owned by the Mendota Historical Society, which also operates the Union Depot Railroad Museum across the street, as well as the Hume-Carnegie Museum of local history, which is housed in a former library. Breaking the Prairie was established in 2001 as the youngest of the three, spearheaded by farming brothers Melvin and Earl Mathesius as a way to promote the Mendota area’s agricultural scene.

Dar Wujek served as the society’s president from 2014 to 2021, and continues to serve as a volunteer docent. Her late husband, Rick, was president of the Breaking the Prairie board, and the couple oversaw the museum’s growth in artifacts and visitors in recent years.

“We promote the agriculture connection,” Wujek said. “There was plenty of industry here, and Mendota is here because of the railroad, but farming was the main industry around here.”

Even the museum’s name is a nod to the history of farming, when farmers would clear the prairie, till the soil, and plant seed — known as “breaking the prairie.” Legendary artist and Iowa native Grant Wood even used the term in one of his pieces: “Breaking the Prairie Sod,” a large mural commissioned by Iowa State College in Ames during the Great Depression and on display today in the university’s Parks Library. It was designed by Wood and painted by students under his direction and depicts mid-1800’s era farmers breaking the prairie.

Mendota once had three railroad companies in town: Chicago, Burlington and Quincy (now BNSF), Illinois Central, and

“Serving

the Area for Over 30 Years”

the Milwaukee Road. Larger cities such as Chicago, Galesburg, Dubuque, Bloomington and Rockford were accessible through the three lines, which ran on either side of Breaking the Prairie. Local farmers didn’t have to travel very far to have their crop or livestock delivered, and that made farming a chief industry in the Mendota area — which also includes towns such as Compton, Sublette, Paw Paw, LaMoille and Troy Grove.

Breaking the Prairie has hundreds of artifacts ranging from machines, tools, advertisements, pictures and other everyday items that farmers from the 1800s and early 1900s would have utilized in some fashion for grain and livestock. Along with many smaller items, the museum’s larger ones include a model replica of a John Deere tractor that would have been used on farms more than 100 years ago, potato planters, a feed scale, and an 1890 Phaeton Buggy that was manufactured in town. Each item in the 1,400-square-foot building is described in detail, and most have a picture of it being used in some way.

The pictures help visitors who may not be familiar with farming’s past — especially younger ones — see just how the items were used.

“My goal was to start pulling out pictures that show some of these things being used,” Wujek said. “It gives it that local feel. It’s really added a lot to the museum. When people come through, like with a hog butcher or something, they can get a feel like, ‘That’s my grandpa!’ Some people didn’t even realize that happened on the farm, and are learning more about it.”

MUSEUM cont’d to page 21

Sometimes the pictures are helpful when it comes to trying to write the descriptions accompanying the pieces, many of them written by volunteer Mary Lynn Sondgeroth, who farmed for many years in the area with her husband Allen.

Mary is also a good source for highlighting the other partner on family farms: the farm wife. While, traditionally, much of the work on farms was done by men, women played a vital role on the farm, too, something the museum strives to emphasize with artifacts that tell the women’s side of the story of farming.

Women played an active role on the farm, raising chickens and selling eggs for income to supplement the farm, Sondgeroth said.

“We’re fortunate to have actual photographs of the people using the products,” Sondgeroth said. “They’re local people. Being a farm wife myself, I tried to include things [in descriptions] that people would wonder about.”

Wujek grew up on a nearby farm that grew produce for Del Monte (and take a guess as to what tractor brand it used; the answer is on page 15). Her grandparents also farmed nearby, and it’s the memories of those days that she aims to preserve and use as teaching tools with her service with the museum. MUSEUM cont’d from page 20

MUSEUM cont’d to page 22

Visitor to the museum will find pieces of farm history both inside and outside: implements and equipment, a rare, mid-1800s Elgin Hummer windmill, and a replica German-style church building

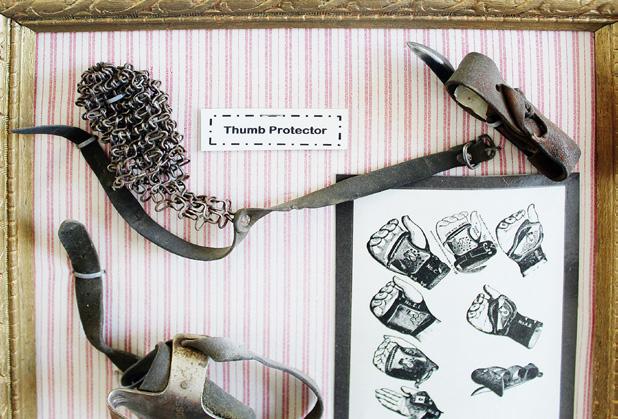

Signs, farm equipment, tools, books, photos and more, the Breaking the Prairie Museum is full of farm history. Among the collection are pieces used by the family who led the effort to create the museum, Melvin and Earl Mathesius, including the thumb protectors below.

“My grandma had chickens and my grandpa took care of the cattle and the farming,” Wujek said. “I can remember the one time of the week that I would stay with my grandparents and I might be chicken butchering. You get to learn all about that. We’d either have pot roast or fried chicken for dinner.”

The museum’s collection has pieces both inside and outside. Implements and equipment are lined up along the side of the museum overlooking the busy BNSF railroad line, including a rare, mid-1800s Elgin Hummer windmill that once stood on the farm of longtime historical society member Dean Otterbach.

The museum is open by appointment only, which can be arranged by calling the historical society (details on page 23).

Elsewhere on the museum grounds, there’s a replica German-style church building, The Country Chapel, which tells the stories of the familiar churches that dotted the rural landscape. The church, built in 2004, was a component of Otterbach’s plan to expand the museum into a working farm that could be used to demonstrate how things were done — that part, however, hasn’t come to fruition yet. The church has a restored pipe organ that was made in town in the 1880s, a stained glass window from one of Mendota’s churches, and a pulpit that once was part of Immanuel Lutheran Church in nearby Compton. It also can be rented out for small weddings.

“Dean Otterbach’s vision was to have a chapel to accompany the working farm,” Wujek said. “The Sunday church was part of farm life.”

Breaking the Prairie has attracted visitors of all ages and backgrounds. It’s been a field trip destination for local schools and ag clubs, such as 4-H. Nursing home and assisted living facilities have made it part of their activity calendars as well, visits that can be particularly enjoyable for residents, and fun for the museum staff. Pieces in the museum can trigger memories for many of the older visitors, Wujek said, who have their own stories of life on the farm.

“Some of the fun tours to do are with nursing and senior citizen homes, because they love it because some of them remember using those things,” Wujek said. “When you do a school group, they may not know what the things are. On one tour, there were 11 people with wheelchairs, and some high school students volunteered to push them and they learned a lot. When they saw their faces light up, it sometimes feels like Christmas morning to them, and then it gets them talking about it.”

Sondgeroth also worked on that visit.

“The senior citizens would be telling them about when they used them, and [the kids] were like, ‘This is so cool,’” Sondgeroth said. “That was a good trip. If you’re in a nursing home, you’re not always going to get out. When you do, you want to make the most of it.”

Museum volunteers make the most of those visits, too, listening to the stories as they accompany their guests on a trip down memory lane, picking up bits and pieces of priceless information from them as they go along.

“We always learn something, too,” Wujek said. “They’re the people that actually did it. I remember butchering chickens and doing all those things with my grandmother as a small child, but to hear these people talk about everything is pretty cool.” n

Cody Cutter can be reached at 815-632-2532 or ccutter@shawmedia.com.

The Breaking The Prairie Museum, 684 Eighth St. in Mendota, is open by appointment. Call 815-539-3373 or email mmhsmuseum@yahoo. com to arrange a tour or for more information.

More museums ... The Breaking The Prairie Museum is operated by the Mendota Historical Society, which also has two other museums that have ag-related items among their displays:

The Union Depot Railroad Museum, 783 Main St. — housed in an active Amtrak station, features items from the town’s railroad lines

The Hume-Carnegie Museum, 901 Washington St. — features more than 150 years of Mendota history.

Find Mendota Museum and Historical Society on Facebook, call the number above or go to mendotamuseums.com for more information.

Want to help?

Donations to help the society’s operations in any of its museums can be made by mail to the Mendota Museum and Historical Society, P.O. Box 433, Mendota, IL, 61342.

Get the financial solutions you need to achieve the success you deserve.

Kewanee • Annawan • Bradford • Dwight

Manlius • Reynolds • Seneca • Sheffield • Tampico

“The Bank for All the People”

By Cody Cutter | Sauk Valley Media

eeping a multi-generational family farm going involves not just a ton of hard work, but also learning the importance of being able to do one simple thing.

Listen.

Ted Jacobs has done a lot of listening during his decades on his family farm. He’s heard stories handed down and lessons passed along from those who tilled the soil before him and turned the land into a livelihood, and they’ve all helped him as he’s played his part in the 94year history of Jacobs Farm.

All told, Jacobs, 62, owns and farms about 1,900 acres of land in Rock Falls and Sterling, growing Pioneer and Wyffels commercial corn, Syngenta seed corn and soybeans. The hub of it sits on the flat and somewhat sandy lands seven miles south of Rock Falls, where the original family home from the 1930s still stands (though that may change; Ted said he plans to take down the house at some point). Sitting alongside that piece of family history are more modern signs of the times — newer buildings that house machines and implements, towering silos, and equipment that keeps up with the demands of today’s farm operation, helping ensure that the Jacobs legacy will be around for another 94 years.

cont’d to page 26

They

supported

Tim Jacobs (left) and his father Ted operate Jacobs Farms south of Rock Falls.

are

by Tim’s wife Morgan (second from left), Ted’s wife Jill, and grandchildren Noah (center) and Jack.

JACOBS

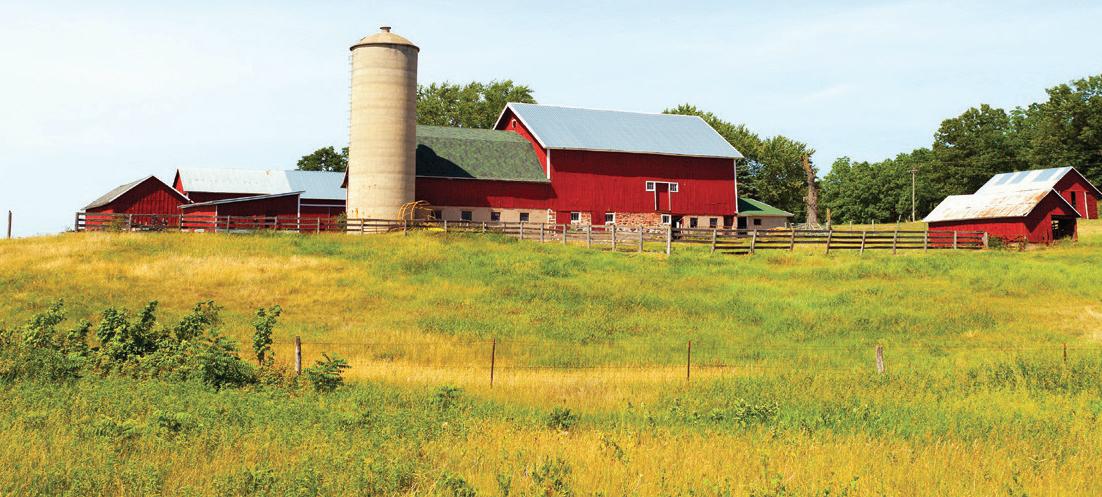

Jacobs Farms, located between Rock Falls and Tampico, has been family owned since 1930, and today is operated by Ted Jacobs and his son Tim Jacobs. Much has changed at the farm since the 1930s when Ernest and Rose Jacobs first settled on it. Only the two-story white house (at left in the photo at top) remains. All else has been razed and rebuilt.

The world of agriculture is always changing — techniques and technology evolve, markets shift, rules and regulations change — but what ages gracefully on the farm are the stories passed down from generation to generation, threads that become family ties, woven together to create a rich tapestry of tales told and lessons learned on the family farm.

Among all those memories are two that come to mind when Ted looks back on his life on the farm — one of which involved his father setting him straight.

“When I started planting corn, when I actually started running the planter, I was riding with my dad when I was 14, 15 or 16 years old, and I kind of made a smart aleck comment to him,” Jacobs said. “I said, ‘That’s all the straighter you can plant?’ We would usually kid one another back and forth. But this time he stopped the tractor and started walking. I said, ‘What are you doing?’ He said, ‘You think you can plant better and straighter, go ahead.’ I’ve been planting ever since.”

And he’s been getting better ever since, too.

JACOBS cont’d to page 27

“I guess you have to be careful about what you say, unless you might be doing it yourself. I got back to the end and he goes, ‘That’s all the straighter you can plant?’ I said, ‘Yeah, I get it.’ It took a long time and a lot of years to get better. It was not straight as an arrow, but it wasn’t crooked, either. I just made the comment, and he fixed me.”

Reaching even further back, Ted remembers other things he learned growing up on the farm. One of his earliest memories was when he was 5 years old, raking hay. It was fun, Ted recalls — for about 20 minutes; then it became work. Another time, he had to take the lead milking cows one day as a fifth-grader when his father had to tend to Ted’s ill grandmother. There was a lot to take in at a young age, but the experience earned and the lessons learned helped Ted when the time came for him to teach the next generation of Jacobs.

He’s taken what father and farm taught him and turned it into his own way of teaching, helping guide his own son as he and Tim tend to the operation — and it didn’t take long for Tim to feel comfortable in the driver’s seat.

Tim’s first time taking charge in a tractor went a little differently than Ted’s first solo run on the corn planter.

“The very first time he got in the tractor, and I showed him how to do it, I left and told him to holler if he had any questions,” Ted said. “I didn’t hear from him all day, so I called him and asked him how things were going. I said, ‘Did you get done?’ He goes, ‘Yeah, I got it moved over to the next field.’ ‘Did you change everything

over?’ ‘Yeah.’ ‘You didn’t have any problem?’ ‘No.’ I said, ‘Well, I haven’t heard from you.’ He said, ‘Well, you said to call if I had problems, and I don’t have any problems.’

“I said, ‘Do you know how to make an AB line and everything?’ He said, ‘Yeah, you showed me.’ I showed him one time. He picked up on that pretty good.”

All those lesson passed down from fathers to sons have paid off. Ted and Tim recently cranked out some of their best corn and bean crops.

Ted represents the third generation of the farm, and Tim the fourth. Ted’s grandparents, Ernest and Rose Jacobs, bought the farm in 1930 and moved into the house a couple of years later. Kenneth, 96, recently moved into an assisted living facility, and Ted’s mother, Julia, died in 2014. Tim’s young children, Jack and Noah, are regular visitors to the farm.

“They love riding in the tractor and the combine,” Ted said. “They like coming over and coming to the shop and riding the toys around. I try to give them a big area to play with. The combine’s their favorite. I like when they come and ride, it’s always a fun time. Sometimes your day ain’t going the best, and then the grandkids show up and it turns out to be a good day.”

Cattle were a part of the first two-thirds of the farm’s history, but when Ted took over in 1993 — recovering from a broken leg at the time — they got out of the cattle business. That’s not to say beef doesn’t play an important role the farm, though — and in the community, too.

JACOBS cont’d to page 28

Ted Jacobs is a thirdgeneration farmer on the family farm his grandparents started in 1930. “I get people that ask me when I’m going to retire, but why would I want to retire?” he said

Jacobs also enjoys giving back to the community, and his biggest contribution is hosting an annual event, the Sauk Valley Area Chamber of Commerce’s Steak Fry in the County, which raises money to help future generations of farmers.

The event, on Aug. 1, is in its 39th year and is a fundraiser for the Sauk Valley Area Chamber of Commerce’s agribusiness scholarships, awarded by the Chamber’s agribusiness committee to high-schoolers within the service area of Whiteside Area Career Center in Sterling (which encompasses parts of Bureau, Carroll, Lee, Ogle and Whiteside counties). Several one-year scholarships are awarded, including $1,500 to students attending an accredited fouryear college or university, $750 to students attending Sauk Valley Community College in Dixon, and $750 for students attending other two-year colleges.

Kris Noble, former executive director of the Sauk Valley chamber, enjoyed having the Jacobs’ host the event, and seeing more than 400 people come together inside the family’s 90-by-150-foot garage for an evening of sizzling steak, delicious cake and friendship on the farm.

“This event brings together the ag community to celebrate and to acknowledge the importance of agriculture in the Sauk Valley,” Noble said. “Ted and Jill Jacobs’ willingness to host this event and welcome over 400 ag supporters is a tremendous example of their generosity and belief in supporting the local ag community. They are really kind people who have been willing to work with this committee to make sure the Steak Fry event runs smoothly. We are truly grateful for their support.”

The farm has hosted the event nearly every year since 2018 (not held in 2020 due to Covid), and it’s seen an uptick in attendees in recent years. All Ted has to do is get his garage prepared for it, and the Chamber does the rest.

JACOBS cont’d to page 29

“Everybody at the Chamber is great to work with and are great people,” Ted said. “They do a real nice job, they’re very professional. I enjoy having it. It makes me clean up my shop a little bit, and you get a lot of people together and you see a lot of people you haven’t seen since the year before. It gets you together to where you visit and kind of find out what the other half of the world is doing.”

As Jacobs approaches an age where most people would think about retirement, he’s thinking about the family farm’s future instead. He’s been at the helm for more than 30 years, and like his crops, he’s still growing. The changing world of agriculture always offers him new les sons to learn and new technology to tackle, and he’s not ready to hand over the keys to the tractor just yet, he said.

“I enjoyed farming, and I still do,” Jacobs said. “I still like doing it. I get people that ask me when I’m going to retire, but why would I want to retire? I like doing what I’m doing. Why wouldn’t you? You look around here, why wouldn’t you?

“If my health holds, I’ll stay at it.”

While there’s much to learn on the farm, for Jacobs, the key to making it all work is simple: Keep your head up no matter what happens. That drive and determination has gone a long way in keeping the farm in the family as it nears its centennial status.

“I always try to stay positive,” Jacobs said. “There can be gloom and doom at times, but you don’t let that get you down. You got to keep a positive attitude and do the things that you can do to make it right, and then the rest of it’s going to happen.” n

Cody Cutter can be reached at 815-632-2532 or ccutter@shawmedia.com.

The 39th Steak Fry in the Country will be at 5:30 p.m. Thursday, Aug. 1, at Ted Jacobs Farm, 6700 Hickory Hills Road, south of Rock Falls. The event allows the community to gather and celebrate agriculture in the Sauk Valley and raise funds for agriculture scholarships and other educational activities, such as Ag in the Classroom, Whiteside County 4H and FFA programs. Desserts made by members of the organizing committee will be auctioned.

The 2023-24 scholarship recipients who will be recognized are Dana Merriman, Marisa Folkers, Sean Fitzpatrick, Emma Dinges, Emma Stabler, Jace Urish, Katelyn Stoller, Katie Shafer, Landon Whelchel, Brieann Spoerlein, Lane Near, Molly Ziegler, Troy Anderson, Owen Farral and Wyatt Wessell.

Tickets are $25 and at saukvalleyareachamber.com/events, by calling 815-625-2400, or at the Sauk Valley Area Chamber of Commerce, 211 Locust St., Sterling. Tickets are limited; deadline to register is July 26. More info: Email Kris Noble at knoble@saukvalleyareachamber.com or call the number above for more information about the event. Go to saukvalleyareachamber.com/scholarships to learn more about the Chamber’s agriculture scholarships.

BY

ou Lamoreux knows the value of a good commodity. The 74-year-old has spent almost his entire life as part of a farm operation in rural Lanark that’s been in his family since 1867.

His fellow members of the ag community know a good commodity when they see it, too: Lou’s expertise.

Through the years his knowledge has been highly sought after among farm leaders throughout Illinois, and he’s always managed to make time to share it, even as he focused on the family farm.

Lamoreux’s rural resumé includes memberships on the Illinois Corn Growers Board and the Illinois Beef Association Board; being a delegate to the United States Grains Council, as well as serving in several other state ag associations — each of which he was persuaded to join by others.

LAMOREUX cont’d to page 32

PHOTO PROVIDED

BETTY HAYNES

“It’s satisfying to be called and asked, rather than to seek some of these places. It’s gratifying to know that there are people who can recommend you for something” he said.

Earlier this year, some people recommended him for yet another honor.

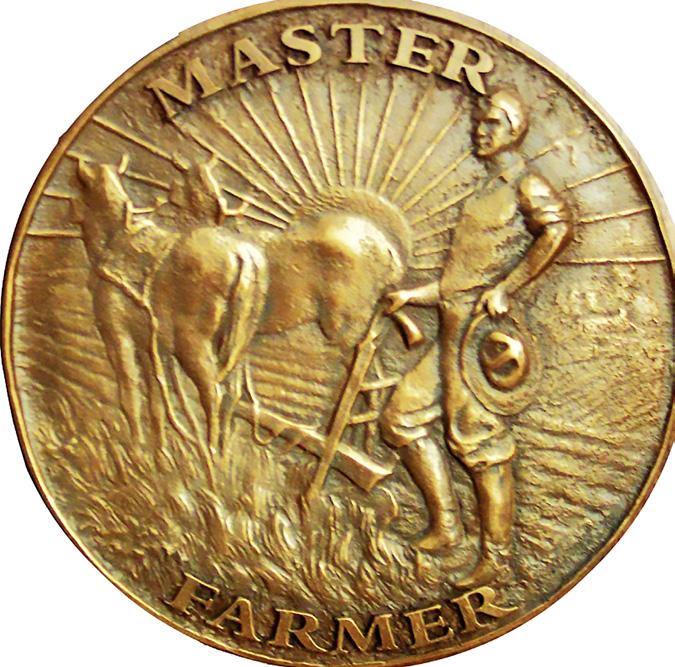

Lamoreux was thought highly enough by both the state corn growers and beef boards to nominate him this year for a prestigious Illinois agriculture accolade: Prairie Farmer magazine’s Master Farmer award, and on March 28 the title became official when he was named one of four honorees at the magazine’s ceremony in Bloomington.

Several members of Lamoreux’s family joined him at the ceremony to congratulate him on the honor, one of which only around 300 other Illinois producers heave earned during the award’s history, which stretches back to 1925. Family is an important part of Lamoreux’s life, helping him maintain a farm that’s been in his family for centuries, and stepping up to carry on that legacy.

Lamoreux Family Farms is an operation equally shared by Lou, his brother John, son Nathan and nephew Dan.

Boone Co., 164 acres, Spring Twp., tillable/timber . . .

“I tell people the Prairie Farmer award has my name on it, but it’s really about those who are back home who keep the day-to-day operations going,” Lou said. “I was afforded the opportunity to do a lot of things I’ve been doing because I have people at home who I knew I could lean on to take care of it.”

John added another name to the list of people who made the award possible: their father, Russell, who passed away in 1991 at age 83. Like Lou after him, Russell served as a state director for the Illinois Agricultural Association and the Illinois Farm Supply during the 1960s.

“It’s probably really an award for our father,” John said. “He started us all off many years ago.”

While being on state ag boards allowed Lamoreux to help others, he’s learned from being on them, too — knowledge he took back to his own operation, as well as those close to home in Carroll County. While happy to serve, he didn’t want to make a second life out of it, he said, especially during the years in which he and his wife of 53 years, Sue, were raising their four children, who also include son Zachary and daughters Calli and Cara. That would have meant spending more time away from the farm than he would have liked. He’s even turned down some opportunities to join other state boards.

Lamoreux is someone who would rather play a hands-on role in the operation: growing corn, soybeans, wheat, alfalfa and rye, as well as raising cattle all alongside his family.

“A long time ago when I first started, I told my wife when I started doing some of these things that I’m only going to serve if I’m going to be elected chair or president of any of these organizations, and I only want to serve a few years,” Lamoreux said. “There are a lot of people who are qualified and have good ideas, and I didn’t want to be one of those who gets entrenched in it and is there for 20 years.”

LAMOREUX cont’d to page 34

. . ASKING $10,900/acre

Boone Co., 74 acres, Spring Twp., all tillable, 113 PI .

Lee Co., 61.12 acres, 58.2 tillable, 123.7 PI

Lee Co., 131.4 acres, mostly tillable, 113 PI

LaSalle Co., 80.65 acres, all tillable, 142 PI

.ASKING $9,900/acre

SOLD $12,900/acre

SOLD $9,500/acre

SOLD $17,700/acre

Winnebago. Co., 199.72 acres, all tillable, class “A” farm, 137.4 PI

$16,975/acre

Winnebago Co. 133.65 acres, all tillable, class “A” soils .

. SOLD $16,500/acre

Ogle Co., 164 acres (MOL), mostly tillable, productive soils 124.5 PI

Ogle Co., 40 acres, Pine Creek Twp., mostly tillable, 114 PI

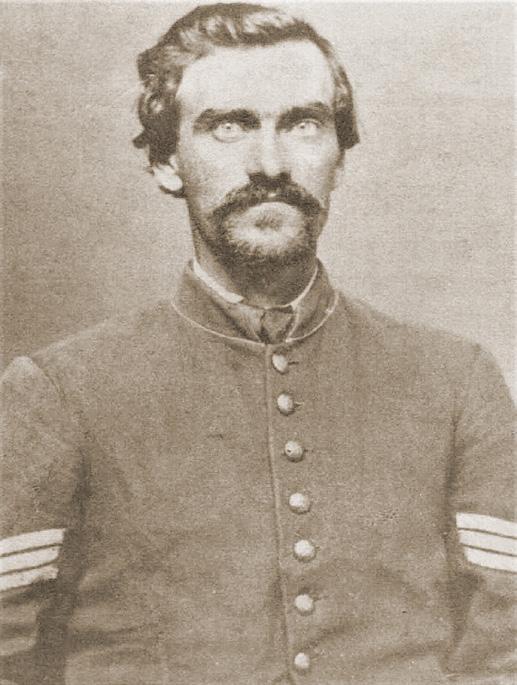

Generations of Lamoreuxes have kept the family farm in the family for 157 years. Lou (seated in photo at far right) is a fourth-generation farmer of cattle, corn, soybeans, pasture, wheat, alfalfa and rye alongside his brother John (standing in photo at far right), son Nathan and nephew Dan. The sixth generation are already learning about the farming industry as they grow up (photo at left). At the 2023 Carroll County Fair, Lleyton, Hawken and Maren Lamoreux were Reserve Grand Champions for their carcass beef and also took home first place in quality grade and average daily grain (5.69 pounds). “Right now they’re very interested in the farm,” grandfather Lou said. “We have hopes that they’ll eventually make their way in.” Center: Lou is seen here receiving the Master Farmers award with his wife, Sue (center), and Prairie Farmer senior editor Holly Spangler.