9 minute read

POLICING THE STREETS: Business districts accused of harassing homeless

State Law Cracks Down on Free Meals

Food-sharing group’s efforts to feed the hungry face new obstacles

Advertisement

By Yesica Prado // Public Press

Under a golden September sky, surrounded by the endless Mission District din, nine hungry people lined up behind a white table at the 16th Street BART station, waiting for a Thursday evening meal.

Cecylian Tiogone, a Food Not Bombs volunteer, smiled as she pushed a grocery cart full of rattling pots into the southwest corner of the plaza, setting up to share the week’s free offering: sautéed veggies, white rice, lentils, bread, green salad, fruit salad and baked pears encrusted with granola.

The all-volunteer global movement collects surplus food from grocery stores, bakeries, markets and local farmers, sharing free vegan or vegetarian meals as a protest against war and poverty.

Many unhoused residents depend on this humanitarian aid to survive. But state regulations taking effect in January jeopardize Food Not Bombs’ 35-year mission of sharing food outside the confines of government bureaucracy. Gov. Jerry Brown signed Assembly Bill 2178 into law on Sept. 18. It forbids so-called limited service SOLVING HOMELESSNESS charitable organizations from serving food in plazas, parks and other public spaces without a permit. Local officials may confiscate the food and cite the organization with a misdemeanor.

Assembly member Monique Limon, D-Santa Barbara, introduced the bill in response to complaints to local health departments about community groups feeding the hungry, making people ill. Opponents, including Hunger Action LA, argued unsuccessfully that no data backed up the claims of widespread food-borne illnesses.

The law expands the definition of a food facility, which is regulated under the Retail Food Code, to include charitable groups “whose purpose is to feed food-insecure individuals.”

Excluded from the law are food banks, cottage food operations, churches, private clubs or nonprofits that give away or sell food no more than three days in any 90-day period.

Other exclusions cover “temporary food facilities” that operate from a fixed location or a swap meet, and “nonprofit charitable temporary food facilities” in which student clubs or organizations operate under the authorization of a school or other educational facility.

In addition, food sharing is limited to distributing whole, uncut produce and food inside its original packing, reheating commercially prepared foods and distributing commercially prepared cold or frozen foods. Home-cooked meals not prepared in a commercial kitchen are forbidden.

But Food Not Bombs does not define itself as a “charitable organization” and meets none of the requirements for an exemption. The volunteers bear the costs for feeding the unsheltered, unless the group collaborates with a local food bank and works under the food bank’s permit and supervision.

As the name suggests, Food Not Bombs “is a criticism and protest of the grossly misguided priorities of the political economy,” said Eddie Steele, coordinator for the San Francisco chapter. The group shares food “in order to fulfill a basic human need currently unmet by U.S. society.”

On the chapter’s website he writes that the new law “is potentially a weapon for those who want to erase the homeless from the streets and punish people who are helping the homeless. These groups are filling a critical gap, and criminalizing their volunteerism will only add to the misery that the state itself is struggling to find the resources to address.”

Steele noted an apparent double standard.

“You can have a barbecue and share with others in the park, and you don’t have the health department Property, business owners use groups’ assessments to police public streets

By Rob Waters // Public Press

tions to manage key aspects of their downtown and commercial districts and to implement policies that restrict the rights of homeless people, according to an August report from the Policy Advocacy Clinic at the UC Berkeley School of Law. Many of the groups use assessments levied on business and property owners — and collected by local tax authorities — to hire security patrols to keep homeless people moving and limit their presence on public streets.

The groups, known as business improvement districts, or BIDs, lobby city councils, the state Legislature and other government bodies for policies that limit the rights of the homeless, the report said. BIDs also provide security services, business promotions, street cleanings and events.

The lobbying efforts by BIDs are of questionable legality, the clinic contends, because assessment revenues are being used to push for policies that affect large areas or numbers of people, not just to provide specific benefits to property owners. In 2013, a Los Angeles Superior Court judge dissolved the Arts District BID, ruling that its “economic development services,” like distributing marketing materials and organizing real estate tours, provided no special benefits, according to the law clinic report.

The report, which was commissioned by the Western Regional Advocacy Project, an association of homeless rights groups that includes the Coalition on Homelessness San Francisco, cites numerous examples of this type of policy advocacy. San Francisco’s largest such group, the Union Square Business Improvement Dis

The group shares food “in order to fulfill a basic human need currently unmet by U.S. society.” — Eddie Steele, Food Not Bombs, San Francisco chapter

telling you to stop,” he said in an interview. “It doesn’t make any sense.”

Steele added that “there has never been a report of food poisoning or other illness” resulting from the group’s operations.

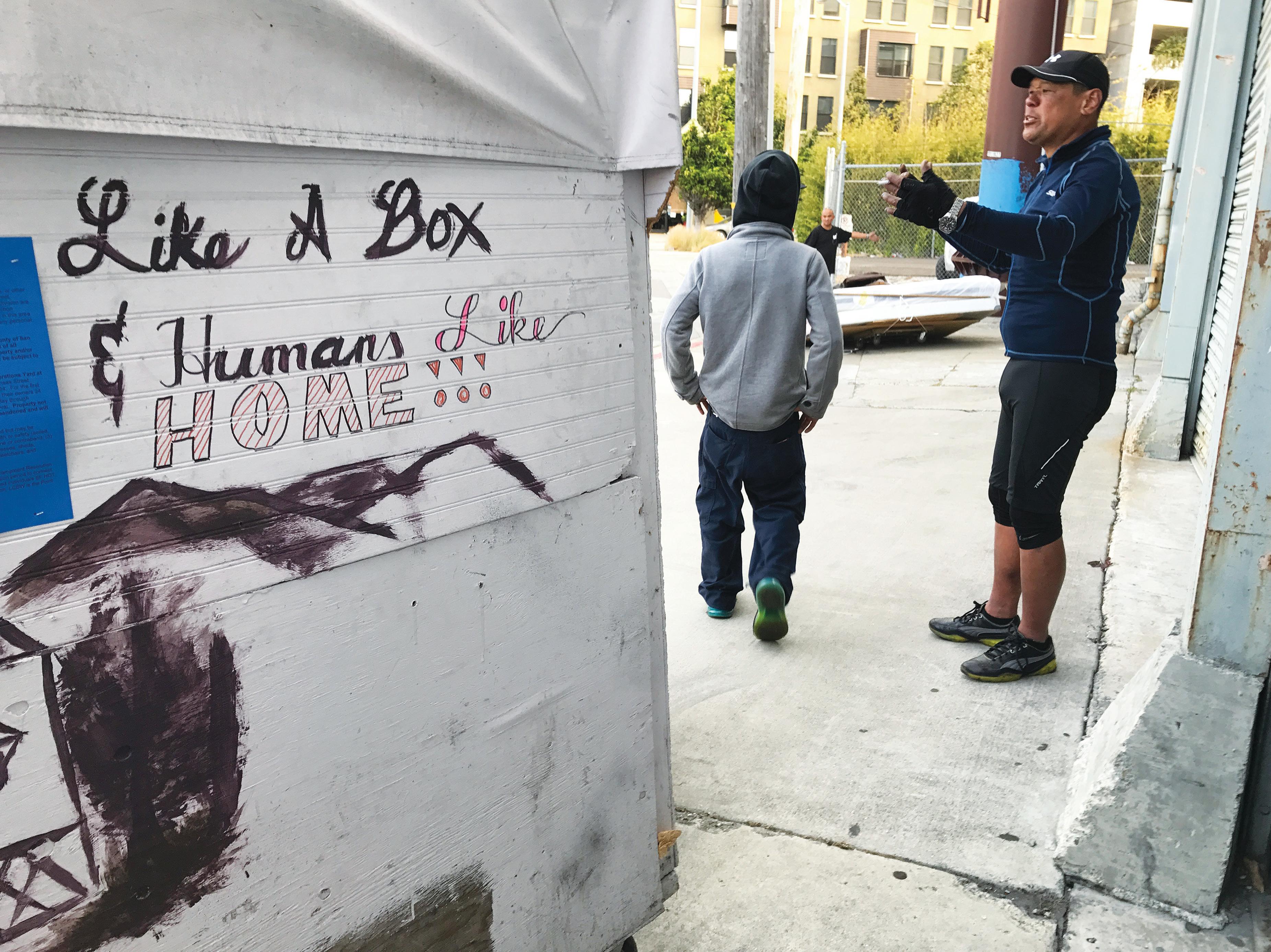

Food Not Bombs is fighting for an exemption. The last Senate amendment before final passage in August might make its case. A private security guard rousting a homeless man outside the S.F. Design Center in Potrero Hill. trict, was a key backer of a 2010 measure approved by San Francisco voters, Proposition L, that barred people from sitting or lying on public sidewalks during the day.

In 2015 and 2016, the California Downtown Association, a network of improvement districts, mobilized members to oppose a “Right to Rest Act” and other bills in the Legislature that would have protected the rights of homeless people to freely use public space. The Downtown Sacramento Partnership, a 66-block BID in the center of the state capital, employed a lobbyist to defeat the measures.

“This is a great example of the potential influence CDA has under the dome,” a reference to the Capitol building, Emilie Cameron, the partnership’s director of policy and communications, told members of the association in an email obtained by the clinic and reprinted in the report. “We have a unique constituency and potentially a very strong voice that can sway legislators on critical issues.”

Emails to the Union Square district and the California Downtown Association requesting comment were

Senators deleted language that would have allowed local health officials to “temporarily suspend the registration of limited service charitable feeding operations during a state of emergency.” San Francisco declared a Homeless State of Emergency in 2016, and other Bay Area cities have followed.

Food Not Bombs chapters in California met in Oakland over the Veterans Day weekend to strategize a not answered.

The creation of business improvement districts is enabled by a series of state laws. According to the Berkeley report, most California BIDs were set up after a 1994 law that allowed a majority of property and business owners in a defined area to petition their local government to establish an improvement district. The law authorized county tax authorities to include the assessments that fund the districts on property tax bills paid by business and property owners.

The law school report estimated that together, California districts bring in “hundreds of millions of dollars” in assessments but did not offer a precise figure. In the 2016-2017 fiscal year, the Union Square BID had assessment revenue of $3.4 million and a budget of $3.8 million.

The report ties the proliferation of business improvement districts to the increasing number of local ordinances controlling or limiting the activities of homeless people. From 1995 to 2014, the report found, 60 BIDs were established in cities across the state and 193 local measures regulating the homeless were enacted.

Many improvement districts hire their own unarmed security forces that typically patrol the district by foot or bicycle and are often referred to as “ambassadors.” While these security operatives do not have power to make arrests, the report cites examples of BID-employed security personnel confiscating the property of homeless people and coordinating closely with police departments to identify “hot spots” and get police to enforce anti-loitering laws.

To Paul Boden, a longtime advocate for homeless people and director of the Western Regional Advocacy Project, the BIDs essentially privatize public space and criminalize poverty and homelessness. The improvement districts want to make sure “that every sidewalk, street and park serve to benefit the businesses,” Boden said. “Public space has become nothing more than the hallways of a shopping mall.”

The report was compiled over two years by law stu

Photos by Yesica Prado // Public Press

Above: Stephanie Le helping to serve meals at the 16th and Mission Street BART plaza in late September. She and other Food Not Bombs workers dish out free vegetarian food every Thursday.

Left: Volunteers Marcos Cruz and Cecylian Tiogone pushing their steel pots back to the group’s home after another weekly feeding.

Far left: Cecilyan Tigone handing out a homecooked meal plate, including steamed vegetables, white rice, lentils and fruit salad.

statewide response to the new law.

In San Francisco, there are 196 food pantries that serve 12 percent of the city’s population, according to the 2013 Assessment of Food Security in San Francisco report. But the demand outstrips supply. Nonprofit food programs are at capacity and always vulnerable to funding cuts from the government and private donors.

Funding is also scarce for federally funded programs like CalFresh, which aids low-income California residents, providing some relief so they can buy healthy groceries. But CalFresh was designed to be a supplemental program and not made to sustain an individual. In 2012, the average individual CalFresh benefit was $149.05 per month, or $1.06 per meal, states the 2013 food security report. The San Francisco Department of Public Health had not released its 2018 reportby mid-November.The Public Press reached out to the health department for comment on this new permit process and policy change, but did not receive a response. At present, there is no procedure to imple

Report: Cities Enable Businesses to Curb the Rights of Homeless

Nearly 200 California cities allow private organiza

Photo by Judith Calson // Public Press

ment. dents working with the Policy Advocacy Clinic. As part of their research, the students identified 189 improvement districts in the 69 largest cities in California and surveyed them about their activities and budgets. They also used public information requests to gather email records, minutes from meetings and other documents.