25 minute read

EDUCATION

Boosters cite charter results, but critics say they drain funds and cherry-pick students

By Rob Waters // Public Press

Advertisement

When students at Malcolm X Academy returned to their elementary school in the Bayview neighborhood of San Francisco in August to begin a new year, they came back to a changed environment. Over the summer, part of their school building had been taken over by KIPP Bayview Elementary, a charter school operated by the Knowledge Is Power Program, the largest charter network in the country and in San Francisco.

For Malcolm X students and staff, the KIPP school was hardly welcome. The San Francisco Board of Education had voted unanimously in 2017 to reject KIPP’s application to open a new school, its third in the neighborhood and fourth in the city. Teachers and students at Malcolm X were also opposed and marched around the neighborhood in May in protest.

But local preferences didn’t matter. The State Board of Education overruled the city’s school board and approved KIPP’s application. The conflict between the two schools — and activists on both sides of the issue — reflects a growing battle playing out in San Francisco and across the state.

Critics say charter and traditional public schools aren’t operating on equal footing — that charters take less than their fair share of the most challenging students, including homeless children and those with learning disabilities, and that they suspend and expel students at higher rates. That selectivity may boost charter test scores, but it erodes hard-won progress in public classrooms and siphons resources from public schools, these critics contend. They argue that the increasingly aggressive, privately funded push for charters amounts to a massive effort to privatize public education by turning public dollars over to private, self-governing entities.

ENROLLMENT DECLINING

This conflict may have a profound effect on the future of the city’s public schools. Enrollment has been declining for years, as poor and middle-class parents flee the city’s high housing costs and affluent families send their kids to private schools. The number of African-American students in district schools dropped from 10,136 in 1996-1997 to 3,925 in 2016-2017. The district has grappled for years with large gaps in test scores and graduation rates that leave African-American and Latino students far behind whites and Asians.

Those gaps have created a hunger for change by black and brown families, and an opportunity for charters. “All parents, including and especially parents in lowincome communities, deserve to have public school choice and to have many options,” said Beth Sutkus Thompson, chief executive officer of KIPP Bay Area Public Schools.

The backers of charter schools are led by the San Jose nonprofit advocacy group Innovate Public Schools, which is bankrolled by Silicon Valley technology investors and the Walton Family Foundation, the philanthropy started by the founders of Walmart. In the past year, Innovate has stepped up its activities in San Francisco, hosting public forums, hiring community organizers and publishing a stream of reports and social media posts that promote charter schools and highlight the poor performance of the city’s public schools in serving African-American and Latino students. It also acts as an incubator, underwriting the costs of developing new charters.

Opposing the charter advocates are parents, teachers and local school board members who have been working to improve the city’s public schools, especially those serving African-American and Latino students. They charge that Innovate portrays itself as community based, but manipulates low-income parents of color, using parents’ frustration with the school system as a way to recruit kids for charter schools.

“They’re fake,” said Alison Collins, a member of the district’s African American Parent Advisory Council and co-founder of SF Families Union, which pushes for equity and improvement in public schools. “If you say you’re working with black families, you should be connected to black families in the community. But they’re not. How can you say you’re championing our issue when you have no connection with us?” Collins, a middle-school mom and former teacher, was elected in November to a seat on the San Francisco school board. Her bid was fueled in part by her anger at the incursion of charter schools.

Innovate cofounder and chief executive Matt Hammer, the son of former San Jose Mayor Susan Hammer, said his organization is “all about great public schools for low-income kids” — whether they are run by traditional school districts or by charter school operators. In the Bay Area, he said, “charter schools are serving underserved kids at a significantly higher level, providing a better education.”

State education data compiled by Innovate show that Latino and African-American students attending district-run public schools in San Francisco far lag white and Asian students in math and English scores, graduation rates and eligibility to attend state universities. And among schools with large percentages of Latinos and AfricanAmerican students, charter schools tend to rank among the highest performers, especially at the high school level.

But that paints an inaccurate picture, opponents say.

“To get into a charter, you have to navigate the application process, and the most

CHARTERS VS. DISTRICT THE BATTLE FOR SAN FRANCISCO PUBLIC SCHOOLS

marginalized families don’t have the wherewithal,” said Mark Sanchez, a former San Francisco principal now serving his second stint on the city’s Board of Education. “They will default into the district school closest to home, and we will gladly serve them.” This may lower the school’s performance on test scores and “allow charter schools to say, ‘We’re doing a better job than you.’ But they’re not reaching the hardest-to-serve students.”

Asked about this during an interview, Hammer and Geraldine Anderson, a Bayview parent who recently joined Innovate’s board, said in unison, “That’s not true.” But state Department of Education data bear out the point: Although a similar percentage of students in district and charter schools are socioeconomically disadvantaged, district schools are serving about four times as many homeless children as charter schools and greater numbers of English-language learners and students with disabilities.

Thirteen charter schools operate in San Francisco, with about 4,300 students. Like all charters, they call themselves public schools and don’t charge tuition. They are not answerable to the school district, and they set their own curriculum, hiring and discipline policies. They receive state funds for every student they enroll, taking money that the local district would otherwise receive.

Across the state, 250 school districts are facing budget cuts, and charter schools — where 10 percent of public school students now attend classes — are a significant cause, according to a report released in May by In the Public Interest, a think tank that studies the impact of privatization of public services. The proliferation of charter schools is draining funds from districts, contributing to gaping deficits, school closings and layoffs, said the report’s author, Gordon Lafer, an economist at the University of Oregon.

Lafer examined the finances of three districts and estimated that, for the 2016-2017 school year, charter school expansion cost the Oakland Unified School District $57 million in lost revenue, forcing the district to cut back on counselors, school supplies and toilet paper. He pegged the cost to San Diego at $66 million and to Santa Clara’s East Side Union High School District at $19 million. San Diego laid off almost 400

“It’s a state of emergency, but charter schools are not the answer.” — Shamann Walton, District 10 supervisor-elect

teachers and East Side plans to eliminate 66 jobs over the next two years.

When students leave district schools to go to charters, it doesn’t do much to reduce expenses, which are largely fixed, but spreads them over a reduced number of students, Lafer said. The loss in revenue means many schools are forced to cut optional services like art and music classes, he said.

Lafer didn’t look at the impact of charter expansion on the finances of San Francisco’s public schools, but he has no doubt it is doing harm. “If you have a declining student population, the last thing you want to do is say, ‘Let’s open more schools,’” Lafer said.

One way to look at the impact on San Francisco is this: If the 4,315 students attending charter schools were instead going to district schools, the district would have additional revenue of about $43 million, based on the $9,865 the district gets from the state for each student enrolled. (Additional funds are provided based on the number of students who are socioeconomically deprived or have special needs.)

To Hammer, the fact that district schools may lose revenue to charters is immaterial. “If federal and state dollars are flowing to public charter schools that are serving kids well, that is a great use of public money,” he said.

At first glance, the forum held at a church in San Francisco’s Bayview district in May had the look and feel of a grassroots campaign for economic and social justice. Young community organizers, mostly black and Latino, signed people in on Apple computers as they arrived. A man wearing a multicolored African kufi cap roamed the hall with a clipboard.

At the front of the hall, a “parent volunteer” was speaking. “I don’t know about y’all, but I’m tired of the community not having control of how it’s policed,” she said. “I’m tired of seeing my family and friends pushed out of the city because they aren’t able to afford living here anymore. … And do you know there are schools in this city where almost none of the black students are able to read or do math at grade level?”

Another woman, alternating between English and Spanish, took a turn. “The only way we’re going to make sure our kids have a bright future is to stand together: Latinos, African-American, Pacific Islanders, whites, standing up for our kids,” she said. “I’m originally from Mexico and all I want – todo que querido – is for my children to have a good future.”

The sentiments were sincere and heartfelt, the problems real. But the call for unity that issued from the podium stands in sharp contrast to the battle unfolding in social media and at school board hearings.

When the application for KIPP’s elementary school came before the board in November 2017, Innovate staff members and parent volunteers packed a public hearing to support KIPP’s bid and to blast the school district for failing African-American and Latino children. They asked that a “state of emergency” be declared.

When the public speakers were done, school board member Shamann Walton, a Bayview resident and newly elected as District 10 representative to the Board of

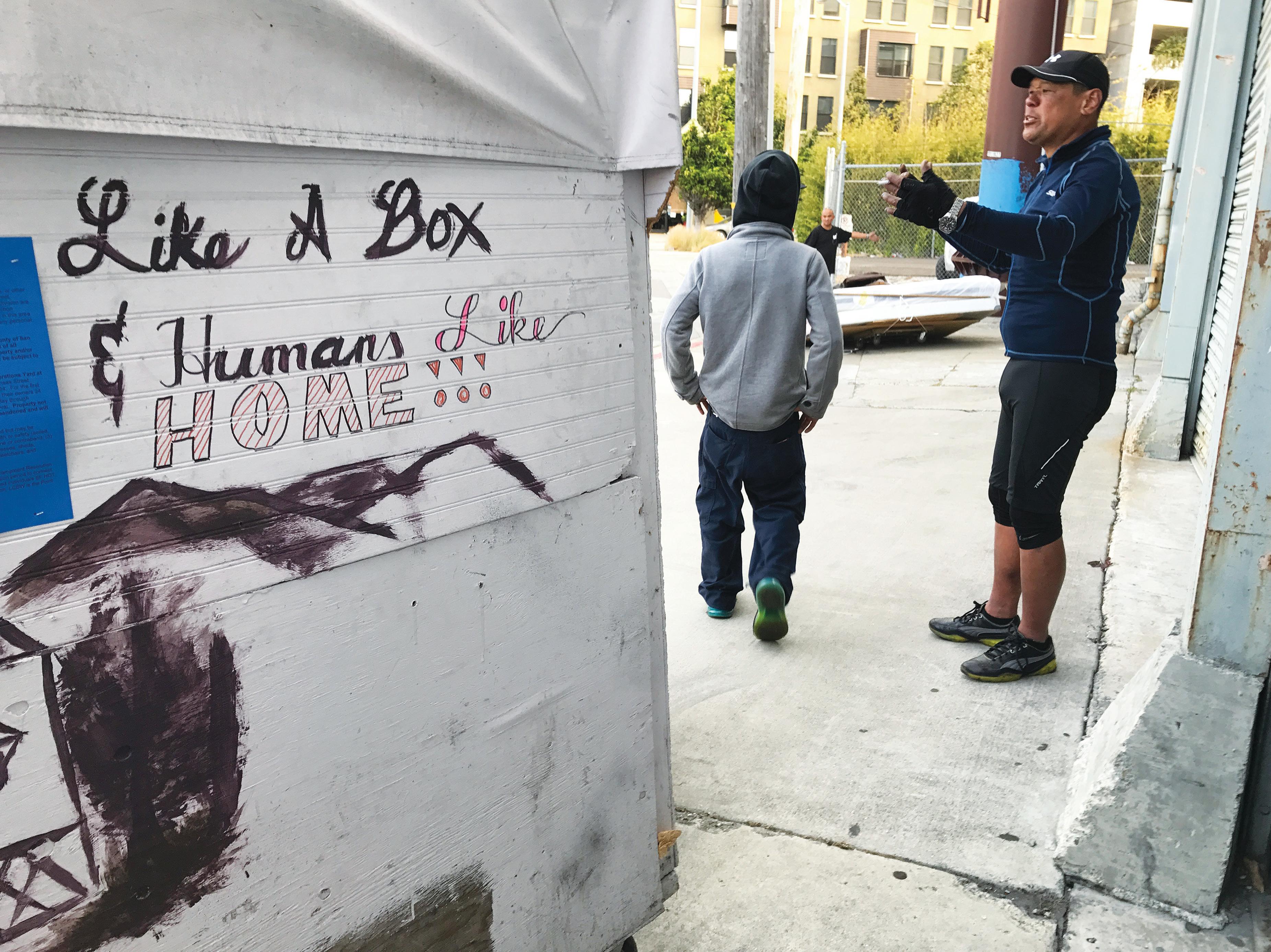

Photo by Rob Waters // Public Press

Malcolm X Academy students and staff marched in spring to protest plans to open a charter inside the Bayview elementary school.

Bayview School Feeling Squeezed by New Charter

By Rob Waters // Public Press

Malcolm X Academy sits atop one of the peaks that gives the Bayview district its name. It has commanding views of the bay and downtown San Francisco. The front of the school is decorated with brightly colored murals of the school’s namesake, maps of Africa and the motto of both the slain black leader and the school: “By any means necessary.”

That motto is being tested as the school and its 105 students — up from 90 last year — share space with 90 prekindergartners, kindergartners and firstgraders attending a new charter school in the same building, KIPP Bayview Elementary.

Thirty-one years ago — when teacher Gina Bissell began working at Malcolm X, and the district still bused children to achieve racial balance — it had more than 400 students and was ethnically diverse. For the past seven years, its census has fluctuated between 90 and 120, according to former Principal Elena Rosen, who left the school in June. About 70 percent of students are African-American.

On an overcast Thursday morning in May, a group of children in red shirts walked up the path to the school, holding onto a long belt and their teachers’ hands. They came from a neighborhood preschool to get a glimpse of the school they would soon attend — a way to help them feel comfortable, Rosen explained. She welcomed them and led them down the hall to join a kindergarten class for circle time.

After a few minutes, the kids headed to recess, each kindergartner holding hands with a preschool buddy. While the kids romped on the large school playground, kicking balls, tossing Frisbees and jumping off a climbing structure, Bissell offered a reporter a school tour.

Bissell, a reading recovery teacher, showed off her room, a corner space with bookshelves, posters and a small table for working with kids one-on-one or in small groups. Every day, she pulls 15 to 18 kids who are reading below grade level out of their regular classroom to help them. Although this work could happen on the sidelines of classes, that can cause “noise and interruptions — and students less focused on learning,” she said.

Since KIPP moved in and took over six classrooms, Bissell is sharing her space with a Malcolm X resource teacher who helps children with special needs. Their meetings are supposed to be confidential, so Bissell and her colleague must figure out how to manage the space and protect the children’s privacy.

As Bissell talked, a thin 8-year-old boy — we’ll call him Derrick — came in and gave Bissell a hug. He had transferred to Malcolm X six months earlier and has since moved up four reading levels. “I get a lot of help from Miss Bissell,” he said. “She’s my favorite teacher.”

At his old school, he said, he had stomachaches and got in trouble for staying too long in the bathroom, ending up with six suspensions. Now, he likes coming to school.

Bissell worries that the strict behavioral rules employed in many charter schools won’t work for kids like Derrick. “It’s too rigid,” Bissell said. “He’s thriving in an environment where it’s more engaging and activated. He’s built trusting relationships with adults and wants to be here.”

On the second floor, an outdoor education classroom used four days a week was lined with seedlings and potting soil. Two doors down, a therapist worked oneon-one with a child. These classrooms, and others used last year by Malcolm X’s afterschool program, have been turned over to KIPP.

Malcolm X has made progress in recent years. By the end of last year, 72 percent of Malcolm X students were reading at or above grade level, up from 55 percent in previous years, Rosen said, the result of experienced, collaborative staff members providing intensive resources and forging partnerships with community programs.

“We’re seeing systematic growth in our reading data,” she said. “We’re closing the gap.”

The sudden decision last May to place KIPP at Malcolm X left staff, students and parents feeling anxiety and worried that some of their fragile progress may be undermined. “It’s hard to share our space,” said librarian Deirdre Elmansoumi. “But we are trying to be cordial and make the most of it.”

Despite the tension, Malcolm X’s new principal, Marco Taylor, and KIPP Principal Allie Welch each pledge to be cordial, professional and positive. “We are committed to being good neighbors,” Welch said in an email to the Public Press. That may get more difficult in the years ahead as KIPP tries to expand, adding one grade each year for the next three years on the way to becoming a pre-kindergarten to fourth-grade school. Supervisors, took a turn.

“There’s a record of charter schools which some of you may not know,” Walton said. “They use our black and brown families to promote certain narratives and propaganda. They get them to start and participate in charter schools and then our most challenging students are weeded out. It’s a state of emergency, but charter schools are not the answer.”

Walton and his colleagues unanimously rejected KIPP’s application — but theirs was not the last word. KIPP appealed, and in March the 11-member State Board of Education overturned San Francisco’s decision.

The state’s decision was inappropriate, Vincent Matthews, San Francisco’s superintendent of schools, told the Public Press. “We evaluated the charter honestly and fairly,” he said. “Those who are closer to what’s actually going on should be the ones to make the determination. I do not believe the state should be overturning local control.”

In June, this process repeated. Another proposed charter school, also backed by Innovate and intended for the Bayview, came before the school board. Backers hope to open the sixth-through-12th-grade school in the fall of 2019 and to name it for Mary L. Booker, a well-known Bayview artist and activist who died last year. The proposed school was represented by Terrence Davis, a former charter school special education teacher from San Diego who was hired by Innovate as a “school founder-in-residence.”

In an interview, Davis said the proposed school would have a social justice philosophy and use restorative justice practices,

“Students’ human rights are being violated. We need immediate action.” — Geraldine Anderson, Innovate Public Schools board member

including a regular Friday community circle. He said he developed the model with help from Innovate and a design team of 10 to 15 parents from the Bayview and Mission districts.

“I sat down with hundreds of parents in coffee shops and homes,” Davis said. Community involvement will be a “core value” of the proposed school, according to the school’s application.

Anderson hopes to eventually send her 7-year-old son, Kingston, to Booker academy, on whose board she sits. Last spring, she pulled him out of Charles Drew Elementary in the Bayview when a spot opened at the New School, a charter that opened last fall in Potrero Hill. She was concerned about violence at Drew and learned from Innovate about how poorly Drew students were doing in math and English. “I was in disbelief,” she said. “Are we really doing that bad?”

But Diane Gray, a Bayview resident and founder of 100% College Prep, a 20-yearold after-school program that helps neighborhood youth get ready for college, said the proposed school didn’t arise from the community. Rather, she said, Innovate developed the idea and began “pounding the pavement” to win support from Bayview parents whose children attend local public schools.

“Innovate and folks who want to open charter schools are targeting our schools and families of color, who believe that by enrolling in charter schools, they’re getting a private school education,” Gray told the Public Press.

STATE OVERRULES S.F. BOARD

As it had with KIPP, the board unanimously rejected the Booker application. The school appealed to the State Board of Education, which unanimously overturned San Francisco’s decision in early November, following a recommendation a month before by the state Advisory Commission on Charter Schools.

The commission is stacked with charter school supporters, said Clare Crawford, a senior policy adviser with In the Public Interest. Five of its eight members are current or former staff members of charter schools, and it votes in favor of charters most of the time, she said. The State Board of Education, whose members are appointed by the governor, has also been highly pro-charter, overturning rejections by local school boards 72 percent of the time charter applicants file appeals, according to an analysis by In the Public Interest.

Gov.-elect Gavin Newsom has suggested he would bring more balance to state charter policies. His Democratic opponent in the June primary, former Los Angeles Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa, received more than $22.5 million from a pro-charter independent expenditure committee, including $7.5 million from Netflix founder Reed Hastings, a member of KIPP’s board of directors. As Villaraigosa faded in the days before the primary, Hastings hedged his bets with a $29,200 donation to Newsom.

Advocates hope to revise the state’s charter school law to force charter schools to be more transparent in their operations and to make it easier for local school districts to monitor and reject them. Some are calling for a moratorium on the creation of charters. In San Francisco, school board member Sanchez has more modest goals. He introduced a resolution in June calling for the district to increase its oversight of charters by tracking the number of homeless, newcomer and special-need students; to analyze the district’s loss of revenue to charter schools; and to track the suspension, expulsion and disciplinary policies of charters.

“To put it bluntly, state laws around charters really disadvantage local districts,” Sanchez said. “We’re at a point where we need to take a break and assess the impact of charter schools in San Francisco.”

VERITAS from Page 1

ings when new tenants move in. “If we’re able to repeal Costa-Hawkins and look at the vacancy-control option, then that gets at the root of their business model.” Hirn described the strategy as “speculative acquisition.” That means that “to pay back the loans they’ve taken out to buy and rehab these buildings, they have to raise the rent on existing rent-controlled tenants through a variety of ways, or they just have to get them out.”

“This is not a new business model,” said Hirn. “But they’re just doing it on a scale, and with a sophistication in San Francisco that I don’t think we’ve seen before.”

But housing advocates were dealt a big blow in November, when voters overwhelmingly rejected Proposition 10.

HARASSMENT COMPLAINTS

In a survey the Housing Rights Committee circulated among 75 Veritas tenants, nearly half reported “receiving a three-day notice that seemed unwarranted, baseless or unfair,” whereas just over half claimed that they, or someone in their household, had suffered a physical ailment or health issue, as a result of construction. Nearly 40 percent of those surveyed said they had to temporarily vacate their units because of construction, almost always without the required advance written HOUSING SOLUTIONS notice. The committee has testified before the Rent Board to raise ethical concerns about Veritas’ practice of contracting with companies founded or run by family members. “We see a lot of inflated Landlords vs. Renters costs, potentially fraudulent costs and also we see their web of contractors, which is really problematic,” said Hirn. “They create these shell companies that are owned by family members of the CEO and they circulate money within themselves.”

Sixty-eight tenants in 30 buildings sued Veritas Investments Inc. on Oct. 11, 2018, accusing San Francisco’s largest landlord of illegal and unfair business practices intended to force seniors and other long-term residents from rent-controlled apartments. Lawsuits have also been filed by tenants in two other Veritas buildings.

Among the allegations are that Veritas Investments and its CEO, Yat-Pang Au, have harassed tenants with extended shutoffs of power, gas and water; engaged in disruptive, incomplete or shoddy construction; violated San Francisco Rent Board regulations on temporary evictions for repairs; and tried to raise rents with questionable pass-through costs or by assessing tenants for interest costs on high-rate loans Veritas secured for its portfolio of more than 300 buildings.

“We have not been served, so we cannot respond to allegations we haven’t seen. However, we dispute all claims that we are hostile or negligent toward our valued residents in any way,” Veritas Chief Operating Officer Justin Sato said in a statement, the San Francisco Examiner reported.

THE VERITAS STORY

Veritas became San Francisco’s largest residential and commercial property owner in 2011 when it purchased a massive portfolio of housing from notorious CitiApartments, which reached a multimillion-dollar settlement with the city attorney over allegations it harassed tenants and did not make repairs. Veritas specializes in purchasing old, rent-controlled properties and rehabbing them for high-end renters. The firm says it manages nearly $2 billion in real estate assets in San Francisco and the Bay Area overall, with almost 200 apartment buildings in San Francisco, mostly 20 to 50 units. Its “vertically integrated business” includes RentSFNow and Greentree Property Management.

Although rent control benefits Veritas by depressing the purchase price of the properties, it restricts the company’s ability to raise rents to meet profit targets. That’s

“The incentive to pressure tenants to leave is created by ‘vacancy decontrol.’” — Brad Hirn, Housing Rights Committee of San Francisco

why, overall, Au has said rent control constrains his ability make upgrades and reduces the supply of modern housing. It requires landlords to wait for units to turn over to higher-paying tenants, or, as tenants-rights advocates contend, to pressure them to leave.

“Investors are realizing that upgraded, classic buildings offer residents the unique, non-cookie-cutter, amenity-rich lifestyle in great demand today,” Au wrote in 2017 in the trade publication Multi-Housing News. “These types of properties form a highly valued and appreciating asset class that, due to its desirability and stability, can provide excellent returns for our investors due to the lower initial cost and significant potential return. And because smaller properties are generally owned by smaller, individual entities, it’s exceedingly difficult for newcomers to aggregate portfolios of a meaningful size to take advantage of the economies of scale.”

Veritas did not respond directly to requests for comment about its business or allegations involving tenants. Violation

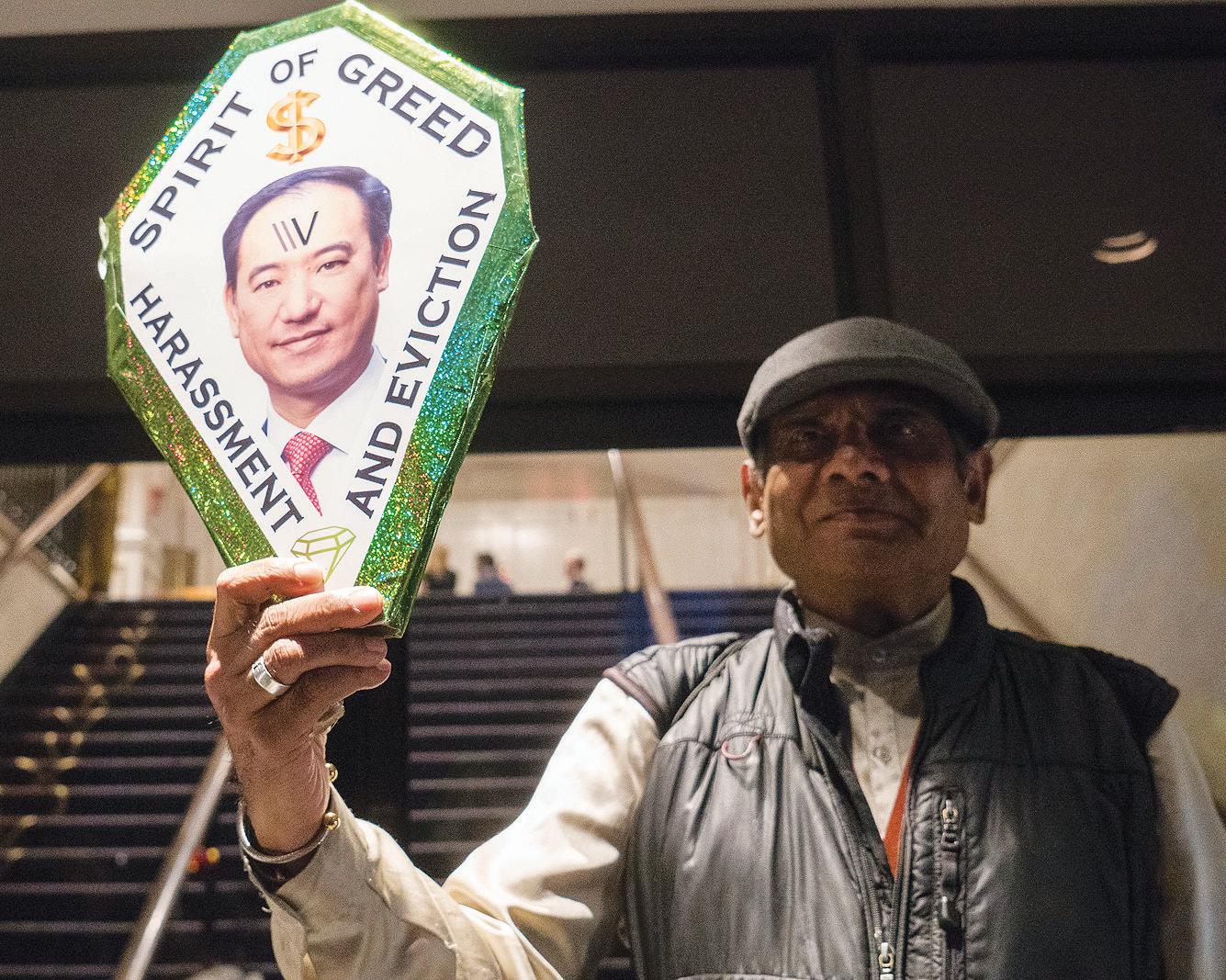

Photos by Yesica Prado // Public Press

In Huntington Park, on Nob Hill, Father John Jimenez and John Dessing joined in a September memorial to pay respects to tenants who died after evictions from Veritas buildings.

Gunvant Shah with the “award” tenant advocates attempted to present to Veritas Investments CEO Yat-Pang Au at the Fairmont hotel.

About 25 protesters showed up atop San Francisco’s Nob Hill in late September to sound off about treatment of rent-controlled tenants and their living conditions.

Radar, a firm Veritas pays to track building code complaints and violations, said in an email that “Veritas has a lower-thanaverage rate” compared with other San Francisco landlords. the most proactive and has the best track record at responding to, and resolving, such complaints.”

He added that “I’ve noticed a greater than 10% decrease in active building code violations against Veritas properties over the past year.”

There is little public data available for Veritas’ properties. That is because each building is its own limited liability company, and there is no requirement that landlords report to local officials all buildings they own under a single entity.

A 2013 structural and collateral term sheet filed with the Securities and ExMembers of the Do No Harm Coalition, which is made up of health professionals and activists, marched from Huntington Park across the street as part of the protest.

change Commission for a loan financing 44 Veritas properties throughout San Francisco offers one window into Veritas’ business model. It shows just under 99 percent of the units were occupied when Veritas bought the buildings. It also shows which is illegal.” with Veritas tenants, approached the

that the company “has achieved an annual turnover of 30.7 percent of total units.” In other words, Veritas replaced nearly one third of its tenants in a year. When a unit turns over, the rent increases, on average, by 466 percent.

THE ROLE OF ‘PASS-THROUGHS’

The Housing Rights Committee’s Hirn cited a host of what he called “abusive” practices, including unlawful rent hikes, habitability code violations, eviction threats and unsafe construction zones. Lawsuits have been filed on behalf of tenants in two buildings: 634 Powell St. and 300 Buchanan St. These suits focus on violations of Section 37.10B of the city rent ordinance, arguing that Veritas’ behavior amounts to tenant harassment.

Central to these lawsuits are allegations that Veritas has exploited regulations about so-called rental pass-throughs. Landlords may petition the Rent Board to ing the building exceeds the amount the landlords receive in rent. Pass-throughs can legally and permanently increase tenants’ rents by as much as 7 percent of their base rent.

Rent Board Executive Director Robert Collins said his agency received passthrough petitions on 1,161 units last year, a fivefold increase from a decade ago, when only 228 units had petitioned. Veritas was targeted during public debate in May, when the Board of Supervisors unanimously passed legislation cracking down on landlords that exploit the law to pass along the cost of loans and property taxes, rather than improvements.

“The goal of pushing these costs onto tenants is to price them out of their units so they can be re-rented out at market rates,” former District 8 Supervisor Jeff Sheehy said at the time.

However, these new laws do not address some of the pass-through violations alleged in the lawsuits filed against Veritas.

CITY ATTORNEY APPROACHED

“We have evidence of them passing on costs from renovations on other units,” said Hirn. “In fact, we have evidence of them passing on costs from renovations in other buildings. They’ve even passed through the costs of correcting housing code violations,

The Housing Rights Committee, along increase tenants’ rents if the cost of operat

City Attorney’s Office about taking action against the company. Spokesman John Coté would not say whether the city attorney is investigating, stating that investigations are confidential.

“Tenants have no power. We need more protection.” — Gunvant Shah, Veritas Investments tenant

After the activists’ protest at the “Spirit of Life” award ceremony, Veritas tenant Gunvant Shah said that rather than make philanthropic donations, his landlord “should take care of our tenants first.” Shah has lived at 698 Bush St. for over 40 years.

“I paid for their mortgages,” he said. “And I have to go to food banks. The conditions I live in … in my old age, I’m living disgracefully.”

Shah’s building has 46 units, 17 of which are single-room occupancies with shared bathrooms. He said that unsafe construction had exposed him and his neighbors to asbestos, lead and other toxins. “I have lead poisoning — 10.9 percent in my blood,” he said.

Shah campaigned to pass Proposition 10 and expand rent control. “Tenants have no power,” he said. “We need more protection.”