58 minute read

agencies using surveillance technology

“The connection between race and surveillance and policing has become more evident to people. It seemed like Oakland was in a good position to create some good examples. To think about how the introduction of technology would affect not just privacy, but equity and fairness issues.” — Deirdre Mulligan, professor and privacy law advocate

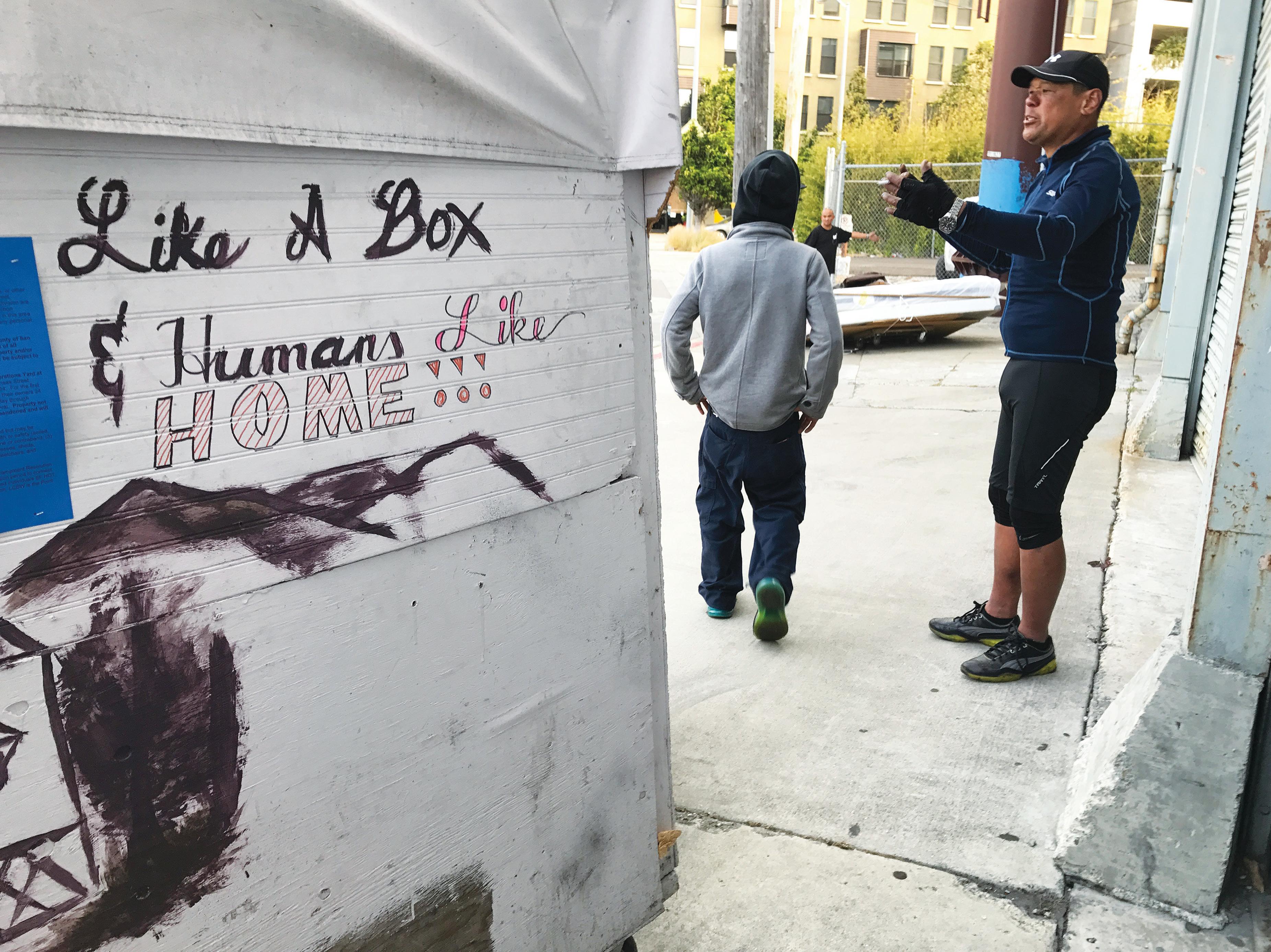

WHY PRIVACY NEEDS ALL OF US Oaklanders, alarmed at law enforcement and corporate overreach, push back

Advertisement

An excerpt from “Habeas Data: Privacy vs. the Rise of Surveillance Tech” (Melville House, 2018)

By Cyrus Farivar

There is one American city that is the furthest along in creating a workable solution to the current inadequacy of surveillance law: Oakland, California — which spawned rocky road ice cream, the mai tai cocktail, and the Black Panther Party. Oakland has now pushed pro-privacy public policy along an unprecedented path.

Today, Oakland’s Privacy Advisory Commission acts as a meaningful check on city agencies — most often, police — that want to acquire any kind of surveillance technology. It doesn’t matter whether a single dollar of city money is being spent — if it’s being used by a city agency, the PAC wants to know about it. The agency in question and the PAC then have to come up with a use policy for that technology and, importantly, report back at least once per year to evaluate its use. The nine-member all-volunteer commission is headed by a charismatic, no-nonsense 40-year-old activist, Brian Hofer. During the PAC’s 2017 summer recess, Hofer laid out his story over a few pints of beer. In the span of just a few years, he has become an unlikely crusader for privacy in the Bay Area.

In July 2013, when Edward Snowden was still a fresh name, the City of Oakland formally accepted a federal grant to create something called the Domain Awareness Center. The idea was to provide a central hub for all of the city’s surveillance tools, including license plate readers, closed circuit television cameras, gunshot detection microphones and more — all in the name of protecting the Port of Oakland, the third largest on the West Coast.

Had the city council been presented with the perfunctory vote on the DAC even a month before Snowden, it likely would have breezed by without even a mention in the local newspaper. But because government snooping was on everyone’s mind, including Hofer’s, it became a controversial plan.

Some of the original and continuing members of the privacy commission: Brian Hofer, Deirdre Mulligan, Raymundo Jacquez, Reem Suleiman, Saied Karamooz

After reading a few back issues of the East Bay Express in January 2014, Hofer decided to attend one of the early meetings of the Oakland Privacy Working Group, largely an outgrowth of Occupy and other activists opposed to the DAC. The meeting was held at Sudoroom — then a hackerspace hosted amidst a dusty collective of offices and meeting space in downtown Oakland.

Within weeks, Hofer, who had no political connections whatsoever, had meetings scheduled with city council members and other local organizations. By September 2014, Hofer was named as the chair of the Ad Hoc Privacy Committee. In January 2016, a city law formally incorporated that Ad Hoc Privacy Committee into the PAC — each city council member could appoint a member of their district as representatives. Hofer was its chair, representing District 3, in the northern section of the city. Hofer ended up creating the city’s privacy watchdog, simply because he cared enough to do so.

On the first Thursday of every month, the PAC meets in a small hearing room, on the ground floor of City Hall. Although there are dozens of rows of theaterstyle folding seats, more often than not there are more commissioners in attendance than citizens. While occasionally a few local reporters and concerned citizens are present, most of the time, the PAC plugs away quietly. Turns out, the most ambitious local privacy policy in America is slowly and quietly made amidst small printed name cards — tented in front of laptops — one agenda item at a time.

Its June 1, 2017, meeting was called to order by Hofer. He was flanked by seven fellow commissioners and two liaison positions, who do not vote.

The PAC was comprised of a wide variety of commissioners: a white law professor at the University of California, Berkeley; an African-American former OPD officer; a 25-year-old Muslim activist; an 85-year-old founder of a famed user group for the Unix operating system; a young Latino attorney; and an Iranian-American businessman and former mayoral candidate.

Professor Deirdre Mulligan, who as of September 2017 announced her intention to step down from the PAC pending a replacement, is probably the highestprofile member of the commission. Mulligan is a veteran of the privacy law community: she was the founding director of the Samuelson Clinic, a Berkeley Law clinic that focuses on technology-related cases.

For his part, Robert Oliver tends to sit back — his eyes toggling between his black laptop and whoever in the PAC happens to be speaking. As the only Oakland native in the group, an army vet with a computer science degree from Grambling State University, and a former Oakland Police Department cop, Oliver comes to the commission with a very unique perspective. When uniformed officers come to speak before the PAC, Oliver doesn’t underscore that he served among them from 1998 until 2006. But he understands what a difficult job police officers are tasked with, especially in a city like Oakland, where, in recent years, there have been around 80 murders annually.

“From a beat officer point of view, who doesn’t have the life experience — and of course they’re not walking around with the benefit of case law sloshing around in their heads — they’re trying to make these decisions on the fly and still remain within the confines of the law while simultaneously trying not to get hurt or killed,” he told me over beers.

The way he sees it, Riley v. California is a “demarcation point” — the legal system is starting to figure out what the appropriate limits are. Indeed, the Supreme Court does seem to understand in a fundamental way that smartphones are substantively different from every other class of device that has come before.

Meanwhile, Reem Suleiman stands out, as she is both the youngest member of the PAC and the only Muslim. A Bakersfield native, Suleiman has been cognizant of what it means to be Muslim and American nearly her entire life. Since Sept. 11, 2001, she’s known of many instances where the FBI or other law enforcement agencies would turn up at the homes or workplaces of people she knew.

“It felt like a prerequisite as a Muslim in America,” she told me at a downtown Oakland coffee shop.

After leaving home, Suleiman went to the University of California, Los Angeles, to study, where she also became a board member of the Muslim Student Association. After graduation and moving to the Bay Area, she got a job as a community organizer with Asian Law Caucus, a local advocacy group. She quickly realized that a lot of people, including her own father, take the position that if law enforcement comes to your door, you should help out as much as possible, presuming that you have nothing to hide.

Suleiman would advise people: “Never speak with them without an attorney. Ask for their business card and say that your attorney will contact them. People didn’t understand that they had a right to refuse and that they [weren’t required] to let them enter without a warrant. It could be my father-in-law. It could be my dad, it was very personal.”

This background was her foray into how government snooping could be used against Muslims like her.

“The surveillance implications aren’t even in the back of anybody’s heads,” she said. “I feel like if the public really understood the scope of this they would be outraged.”

In some ways, Lou Katz is the polar opposite of Suleiman: he’s 85, Jewish and male. But they share many of the same civil liberties concerns. In 1975, Katz founded USENIX, a well-known Unix users’ group that continues today — he’s the nerdy, lefty grandpa of the Oakland PAC. Throughout the Vietnam era, and into the post-9/11 timeframe, Katz has been concerned about government overreach.

“I was a kid in the Second World War,” he told me over coffee. “When they formed the Department of Homeland Security, the bells and sirens went off. ‘Wait a minute, this is the SS, this is the Gestapo!’ They were using the same words. They were pulling the same crap that the Nazis had pulled.”

Katz got involved as a way to potentially stop a local government program, right in his own backyard, before it got out of control.

“It’s hard to imagine a technology whose actual existence should be kept secret,” he continued. “Certainly not at the police level. I don’t know about at the NSA or CIA level, that’s a different thing. NSA’s adversary is other nation states, the adversaries in Oakland are, at worst, organized crime.”

Serving alongside Katz is Raymundo Jacquez, a 32-year-old attorney with the Centro Legal de la Raza, an immigrants’ rights legal group centered in Fruitvale, a largely Latino neighborhood in East Oakland. Jacquez’s Oakland-born parents raised him in nearby Hayward with an understanding of ongoing immigrant and minority struggles. It was this upbringing that eventually made him want to be a civil rights attorney.

“This committee has taken on a different feel postTrump,” he said. “You never know who is going to be in power and you never know what is going to happen with the data. We have to shape policies in case there is a Trump running every department.”

As of late 2017, the PAC’s most comprehensive policy success has been its stingray policy. Since the passage of the California Electronic Communications Privacy Act, California law enforcement agencies must, in

Photos by Sharon Wickham // Public Press

“The surveillance implications aren’t even in the back of anybody’s heads,” says Reem Suleiman, Oakland PAC.

nearly all cases, obtain a warrant before using them. But the Oakland Police Department must now go a few steps further: As of February 2017, stingrays can only be approved by the chief of police or the assistant chief of police. (In an emergency situation, a lieutenant or above must approve.) In either case, each use must be logged, with the name of the user, the reason and results of each use. In addition, the police must provide an annual report that describes those uses, violations of policy (alleged or confirmed), and must describe the “effectiveness of the technology in assisting in investigations based on data collected.”

PROP B from Page 1

submitted to the board before June. “It’s time that San Francisco and the nation start actually evolving policies where your location can’t be tracked without your consent,” said District 3 Supervisor Aaron Peskin, who authored Proposition B. “This is a teachable moment. San Francisco can lead the nation in privacy-first policies.”

The Charter Amendment, which was put on the ballot by a unanimous vote of the Board of Supervisors, had split advocates and groups that are normally allies — and that otherwise enthusiastically support 99.9 percent of the measure.

The opposition came primarily from journalists and First Amendment watchdogs. They’re concerned that a small subsection of the measure, only 36 words long, could water down San Francisco’s legendary Sunshine Ordinance, which mandates transparency in city government. They argue — and Peskin and the city attorney dispute — that the language could give the mayor and Board of Supervisors the power to restrict access to public records, meetings and ordinance oversight without voters’ approval.

Notably, there was no vocal objection from Silicon Valley, which appears to be holding its fire for the rulemaking process.

THE GUIDING PRINCIPLES

So what exactly does Proposition B propose? It contains 11 principles that will apply to city officials, departments, commissions, boards and “other entities”; all contractors and lease holders, and anyone with city-issued licenses, permits or grants. Many principles exceed the scope of the new state law, including:

• Opting out of handing over personal data but still receiving a company’s services. • The right to move about the city and not be tracked without consent. • Discouraging the collection of personal information regarding race, religion. sexual orientation, disability and other potentially “sensitive demographics.” • Anticipating and mitigating bias in data collection and the use of algorithms.

But exactly what the policies will look like is still unknown. Now that Prop B has been approved, the principles will simply guide the city administrator in writing a new ordinance that must be presented to the Board of Supervisors by May 31. Public hearings will follow before the board votes.

“This proposition is just really a stepping stone,” said Sameena Usman, with the Bay Area Council on American Islamic Relations, or CAIR. The group endorsed Proposition B, and is most interested in how any resulting privacy legislation would address surveillance.

“When you have local cities that might be gathering this surveillance data and potentially sharing it with the federal government, that’s very concerning,” she added, noting the Trump administration’s interest in tracking Muslims. Her hope is that Proposition B could lead to a separate surveillance ordinance.

BIG DESIRE FOR DIGITAL PRIVACY

Data protection remains a major issue in the Bay Area. A May 2018 Silicon Valley Leadership Group survey of 1,843 voters in five counties found that 86 percent were concerned about the security of the personal and financial data they’ve given to companies or placed online. More than two-thirds have had their data compromised, and more than half the respondents supported more government regulation of how companies use that information.

Among all voters, 51 percent backed more regulation, 34 percent preferred about the same degree of regulation and 8 percent wanted less. Liberals were far more likely than conservatives to favor tighter regulations (57 percent versus 38 percent). Both about equally supported no change (38 percent for conservatives, 33 percent for liberals), while conservatives were six times more likely than liberals to want less government intervention (3 percent versus 18 percent). By comparison, a Reuters national poll in March found that 46 percent of adults supported increased regulation, 20 percent said current laws are sufficient and 17 percent wanted less regulation.

“In an ideal world, Congress would have taken this up, but most of the congressional action has not been helpful,” said Shahid Buttar, with the Electronic Frontier Foundation. “It has fallen to states and cities to innovate and to protect innovation and to protect user rights.”

In the past few years, Oakland, Seattle and Chicago have adopted privacy programs. California legislators went further in June, passing the nation’s strongest privacy safeguards, which Gov. Jerry Brown signed. Taking effect in 2020, the California Consumer Privacy Act includes a European-style “right to erasure” of one’s personal information, and permits consumers to sue for damages after data breaches. But many advocates say more is needed.

THE RIGHT TO RETAIN YOUR DATA

“Tech is neither good nor bad; it doesn’t have a built-in morality,” said Peskin. “Right now, companies know literally everything about you.”

Crucially, he added, whereas the state privacy law allows customers to opt out of their information being sold, the principles in Proposition B allow opting out of that information being collected in the first place. Even if a consumer didn’t consent to share private financial or personal information, those companies will still be required to make their services available to San Fran

Photo by Sharon Wickham // Public Press

“It has fallen to states and cities to innovate and to protect innovation and to protect user rights.” — Shahid Buttar, Electronic Frontier Foundation

ciscans.

“If you deny, you should not be denied the service,” Peskin said. “If you are not willing to accept their standards, you should still be able to use Facebook or to get your scooter ride.”

The privacy policies of Skip and Scoot, which were recently granted permits to operate rentable scooters in San Francisco, differ significantly on this point. While Scoot’s terms of service state that customers’ “user name and profile picture may be publicly available and that search engines may index your name and profile photo,” Skip’s has an option more in line with Proposition B’s principles, allowing customers to “use the Services without providing us with information.”

“Should Proposition B prove successful … it could go a long way towards informing the kind of a regulatory frameworks you could see emerging from other jurisdictions,” said Buttar, of the Electronic Frontier Foundation, who evaluated the measure while it was being drafted.

The First Amendment Coalition and the Society of Professional Journalists Northern California support Proposition B’s intention to enhance privacy protections, but campaigned to defeat the measure because of concerns about potential harm to the city’s voter-approved Sunshine Ordinance and its task force, an 11-member body charged with protecting the public’s interest in open government. They were joined in their opposition by the League of Women Voters San Francisco and the San Francisco Labor Council, among a dozen other groups. The San Francisco Green Party, Republican Party and Libertarian Party were also opposed.

Task force chair Bruce Wolfe calls the ordinance “one of the strongest in the country, if not the world,” primarily because of the option of an “immediate disclosure requirement” — a 24-hour deadline for the city to provide requested information, and a focus on accountability of individuals, not just a particular department or agency. (Public Press Publisher Lila LaHood is a task force member.)

PRO-TRANSPARENCY CULTURE

Reporter Matt Drange has first-hand experience with the Sunshine Ordinance’s benefits. He said that while doing a story on gunshot-surveillance technology for the Center for Investigative Reporting he was able to easily get data from the San Francisco Police Department that was not forthcoming from other Bay Area cities.

“There is a definite pro-transparency culture that I think it’s helped to shape,” said Drange, who co-chairs the Freedom of Information Committee of the Northern California chapter of the Society of Professional Journalists. “And that’s what we’re most concerned about losing.”

That fear refers to one particular sentence in subsection (i), on the fifth page of Proposition B. Although the Sunshine Ordinance is not mentioned, it’s the reason those disputed 36 words were included, Peskin said.

All parties agree that the 19-year-old ordinance needs to be updated, but because it was approved by voters, they would also have to authorize any changes. San Franciscans for Sunshine member Richard Knee wrote that his group hopes to put a package of reforms on the November 2019 ballot. “But it’s a struggle because the group doesn’t have sufficient funds to gather enough voter signatures,” he said. (Knee, a freelance copy editor for the Public Press, co-authored the official ballot argument against Proposition B.)

Most pressingly, one of the task force’s members must be nominated by New America Media, which was founded by legendary journalist Sandy Close and closed in November 2017. Until voters approve a change for that process, the seat will remain empty, hampering the body’s work.

Peskin said the language in subsection (i) will allow the Board of Supervisors to replace New America Media with another entity. The supervisors could also make other bureaucratic fixes to the overall ordinance should they arise. It reads:

… the Board of Supervisors is authorized by ordinance to amend voter-approved ordinances regarding privacy, open meetings, or public records, provided that any such amendment is not inconsistent with the purpose or intent of the voter-approved ordinance.

“We were trying to do a solid for the sunshine advocates,” said Peskin’s aide Lee Hepner.

But sunshine advocates complained that

“If you are not willing to accept their standards, you should still be able to use Facebook or to get your scooter ride.” — Aaron Peskin, District 3 supervisor

they weren’t consulted on the wording.

The phrase “intent and purpose” is central to the debate, said First Amendment Coalition Executive Director David Snyder.

“That’s a very subjective, squishy phrase,” said Snyder, who served as the Sunshine task force’s attorney from 2010 to 2012. “It’s kind of a circular thing: ‘Consistent with the intent and purpose’ means whatever the Board of Supervisors deems to be ‘consistent with the intent and purpose.’”

Added Drange, “Essentially it would give them the power to check themselves. We’re handing over the authority that currently rests with the public and saying, hey, if you guys want to make changes to the ordinance, go ahead.”

Although the First Amendment Coalition was officially opposed, Snyder still believes “the overall stated purposes and the overall purpose of Proposition B is a laudable one.”

“I doubt that that sentence was put in there as a kind of intentional poison pill,” he added. “But the problem with wording like that is that it can ultimately be used that way, regardless of what the original intent was.”

Peskin said worries about an attack on the Sunshine Ordinance are unfounded.

“I think they’ve misread it,” said Peskin of the journalists’ organization. “I respect them, but I think that their fears are misplaced.”

He and the measure’s supporters, including the San Francisco Democratic Party and the San Francisco League of Pissed Off Voters, maintain that the language is clearly in support of open government.

Peskin said the phrase “is not inconsistent with the purpose or intent of the voter-approved ordinance” means that no changes could be made to the task force, or the Sunshine Ordinance itself, that didn’t maintain its strength.

“The sentence is very clear,” Peskin told the Public Press. “It cannot in any way diminish the purposes of Sunshine.”

“Any notion that public records laws may be weakened is not only legally impossible, it is a distraction from the important privacy rights that Proposition B would advance,” he wrote in rebuttal to the opponents’ ballot argument.

Before the election, the city attorney supported Peskin’s notion, saying in a written statement that upon passage of Proposition B, “we will advise the City Administrator, Supervisors and Mayor about any proposed privacy ordinances that could impact the Sunshine Ordinance to help ensure they are consistent with the voters’ intent.”

But Drange said the journalists’ organization was “caught off guard” in July when it learned how Proposition B might affect the task force.

“It was already on its way to the printer,” Drange said. “The ship had sailed in terms of trying to get it altered or get it removed.” The Society of Professional Journalists already submits names for two of the 11 task force seats, and had been part of previous conversations seeking a fix for the New America Media vacancy.

“It’s bizarre that no one in government let us know,” he said.

Drange said there have been “attacks on the task force” in the past, and he fears a future Board of Supervisors could change its makeup for political reasons, or in other unproductive ways. “They could add a representative for tech companies,” he suggested.

“There was a purge of many members of the task force back in 2012 who had publicly disagreed with a couple of the supervisors at that time, and a couple high-profile cases,” said Drange. “And then following that, the SPJ nominations for task force members in 2014 were actually delayed for months.”

Task force chair Wolfe said they were “not notified at all” and learned about subsection (i) when it was too late to suggest different language. “We had to find out from members of the public and from opengovernment advocates,” he said.

Peskin’s office also pointed out that the measure’s text was publicly available for 60 days, and noted the irony that groups focused on transparency didn’t take advantage of that window.

TECH WATCHING, WAITING

Facebook didn’t take a position on Proposition B. “We look forward to working with policymakers in San Francisco on finding approaches that protect people and support responsible innovation,” the company said in a written statement.

Hepner said Facebook and several other tech companies initially approached Peskin’s office when they heard a privacy policy was in the works. But they “stayed out of opposing it, probably because they would like to know how the trailing legislation forms” next spring.

The American Civil Liberties Union and the Electronic Frontier Foundation spoke with Peskin’s office during the drafting process but took no position on the measure.

While digesting election results, it’s important to remember that the passage of Proposition B didn’t change any laws, just cleared a path toward new policies.

“For the sake of expediency in getting some simple amendments changed,” the measure “could be helpful,” said Wolfe, the chair of the Sunshine Ordinance Task Force. He was “neutral” on the measure, “because the meat of it is so important.”

But “transparency is extremely important these days,” he added. “These laws are really important and they need to be protected with the utmost of care.”

Photo by Noah Arroyo // Public Press

During a youth-run election forum, moderators Kierre Garrett and Tyjaya Lynch asked 12 school board candidates how they would involve students in policymaking and improve academic achievement. Candidates, from left: Monica Chinchilla, Faauuga Moliga, John Trasviña, Phil Kim, Michelle Parker, Alison Collins, Alida Fisher, Lex Leifheit, Martin Rawlings-Fein, Gabriela López, Roger Sinasohn and Paul Kangas.

By Noah Arroyo // Public Press

It was another election forum, another school night, and most of the candidates running for the three open seats on the San Francisco school board were arrayed on a stage, facing their two questioners.

But this fall night of ask-and-answer was different. These candidates would be grilled by representatives of the constituents who matter the most in education but who are seldom heard from in the scramble toward Election Day: the students themselves.

Moderators Kierre Garrett and Tyjaya Lynch, both 17, controlled the program that night, firing questions at 12 of the 18 candidates and calling on selected students to ask what was on their minds.

And Lynch did not hesitate to be the enforcer. When candidates, several of them educators, didn’t follow instructions to keep answers brief, she checked them: “Yes or no, please.” When they talked past the time chime, she was the sheriff.

The late-September forum, at the African American Art & Culture Complex in the Fillmore District, was unique in this election season. It was designed and run by members of Youth Council, ages 16 to 24, part of the My Brother and Sister’s Keeper initiative by the San Francisco Human Rights Commission. Questions revolved around how the district could foster equity among schools, how to close the achievement gap — or “opportunity gap,” as some called it — between white and minority students, and how to involve students in key policy decisions.

About 80 parents and students turned out for the forum, which was co-sponsored by Black Young Democrats, Black Community Matters and the Public Press.

RACISM AND SEGREGATION

An audience member asked the candidates how they felt about the “school-toprison pipeline and its effects on students of color.” Alison Collins, a former educator of 20 years who writes an education blog, answered last. She didn’t mince words. The other candidates had offered ideas for dismantling the pipeline, like increasing literacy or reducing policing on campus. But none had put a name to the reason such policies were necessary in the first place.

“Systemic racism is a problem,” said Collins, the only African-American on the stage. “If we’re not going to talk about racism — and actually say ‘racism,’ which nobody wants to say — we’re not going to fix problems that are related to racism.

“There are also kids that behave in totally normal ways, and are criminalized for it. Our children are labeled violent, angry, problematic, too loud, I mean, you see it all over the country, right? And it’s happening in our schools,” Collins said. “I’m a mixedrace person, my kids are treated differently, based on the color of their skin. And that’s something that really needs to be talked about.”

With that, the forum had placed its finger on these well-documented facts: The district’s African-American students have long lagged their white and Asian counterparts in scholastic achievement, while exceeding them in suspensions.

Garrett, who attends City Arts and Tech High School, and Lynch, a student at Raoul Wallenberg High School, underscored fundamental inequalities in the city’s educational system during a series of quick yes-no questions to the candidates.

“Do you believe the curriculum is inclusive of all people’s histories, specifically people of color?”

“No,” the candidates replied, one by one.

“History is written by the rich,” candidate Paul Kangas, a Navy veteran, private investigator and father of three, interjected.

“Do you think the current studentassignment system has made the schools more segregated?”

“Yes,” they all said.

Segregation is nothing new for the dis

YOUTHS TAKE CHARGE

Students grill school board candidates on inequality, systemic racism

Photos by Michael Winter // Public Press

At the African American Art & Culture Complex in the Fillmore District, the audience listened closely as candidates answered questions. At right, Alison Collins, who was one of three to be elected, spoke as Michelle Parker and Phil Kim waited their turns.

trict. The Public Press found in 2015 that the problem was getting worse, but in December 2017, the district reported that the number of schools with more than 60 percent of a single racial or ethnic group had fallen from 22 to 17 schools since 2011. The issue resurfaced in September when school board commissioners called for changing the current assignment system.

Asked how he would close the achievement gap, social worker Faauuga Moliga suggested that schools should open more “wellness facilities,” where therapists, social workers and pediatricians would help students grapple with problems that influence and go beyond scholastic achievement. “Some of these kids and families are coming from really tough places,” Moliga said.

Michelle Parker, former president of the district Parent Teacher Association, said the district should “make sure that all of the children in San Francisco have access to two years of high-quality preschool before they come to kindergarten. We know that that works.”

She also noted that other districts were using an “equity index” to determine how to divvy up money among schools. In their calculations, the districts weigh rates of gun violence and asthma in the surrounding neighborhoods. San Francisco could follow that example, she said.

FUNDING INEQUALITY AMONG PTAS

One audience member said “it seems wrong” that some parent-teacher associations raise hundreds of thousands of dollars for their schools while others do not, and he asked how the candidates would address this. (The Public Press reported in 2014 that fundraising provides some schools with supplies and extracurricular programs that others cannot afford.)

Most candidates liked the idea of pooling PTA-raised money from schools and redistributing it based on need — as long as parents were involved in that decision.

Parker said the district could “get creative” about raising money, and she referred to her previous efforts courting corporations to donate to the district.

Phil Kim, manager of Science & Design, Computer Science and Engineering for KIPP charter schools, said he liked the model employed by Circle the Schools, an initiative by San Francisco Citizens Initiative for Technology and Innovation, headed by tech heavyweight Ron Conway, in which “nonprofits and companies actually sponsor schools.” Kim added that it “would be really fascinating to see friendships spring up between schools, who are sharing resources, sharing professional development opportunities, in addition to sharing PTA funds.”

Political organizer Monica Chinchilla suggested soliciting contributions from residents who live near schools and “don’t have kids but still want to help. They believe in education and have dollars to spend.”

Throughout the night, there was broad agreement about other problems that hamper student equity. They said that teachers should be paid more and receive more staff support in classrooms, and that the district should hire more black and brown faculty.

POLICYMAKERS INVOLVING STUDENTS

One audience member, a senior at Mission High School, said that policies on discipline, safety and curriculum are often made without consulting the students.

“What system will you put in place to ensure you are collecting input from students?” he asked.

“Students should be sitting on every district committee we have,” said education consultant Alida Fisher, a mother of four African-American students. “We have parents sit on a lot of them, but students? No.”

Lex Leifheit, who works for the San Francisco Office of Economic and Workforce Development, said that in such a scenario, “I think we need to think about stipends and about paying them for their time.” Other candidates concurred.

Parker suggested that students lead district discussions, emulating some parentteacher conferences. “I think that makes it much more relevant to you,” she said.

Many other ideas surfaced. “I would love to see students have a seat on the board,” said Martin Rawlings-Fein, a bi/ trans parent employed by the University of California, San Francisco. Gabriela López, a teacher at Leonard Flynn Elementary School, suggested that every school have a student representative, similar to how they all have union representatives. Roger Sinasohn, a writer and technology worker married to a city teacher, said that board members could visit schools more often, and that the homeroom period would be an appropriate forum for meeting with students to discuss policy. Collins said the district could also use online polls to get student feedback.

Kim said students should be able to

weigh in on district expenditures. “Students should be looking at those budgets and telling us which items are actually making an impact,” he said.

Taking a slightly different tack, John Trasviña, who served as the Department of Housing and Urban Development assistant secretary for fair housing under President Barack Obama, said the district should support student newspapers because they “can expose a lot of things that are going on within the district, and be a voice for students.”

IMPORTANCE OF BEING HEARD

What sparked students to organize and run the forum?

The Youth Council had been playing with the idea of an election event when De’Anthony Jones, a liaison at the Mayor’s Office of Neighborhood Services who works with the council, attended a mayoral forum in May sponsored by San Francisco Young Black Democrats, Black Community Matters and the Public Press. That inspired the Youth Council — also the San Francisco Community Action Team for Opportunity Youth United, a national civic-engagement organization — to do something similar to inject student voices into a process that parents and other adults generally control.

“They said, ‘Hey, let’s focus on the school board.’ It’s something they’re directly affected by,” Jones said.

Yolanda Flakes joined the council in part to figure out how to elevate underrepresented voices. She was one of about 15 youths who crafted the event’s questions.

At 17, Flakes’ complex identity gives her a unique perspective into the cultural friction playing out in classrooms. She is African-American and Filipina, raised by her black birth mother, but for the last eight years, she has lived with her white foster parents. She spent her first two years of high school at a private school she characterized as better resourced than Mission High, where she is a senior. These experiences have shaped the way she speaks and carries herself.

“When people first meet me, they assume something about me, because I’m a black person, but they note something that isn’t stereotypical about me,” Flakes said. “They’ll look at other black people differently.”

She said teachers often discipline other African-American students more harshly than her and her white peers. From her vantage, “looking at it from the outside,” she said that teachers should try harder to listen and make space for students to share how they feel about their experiences and the punishments they receive in class.

“If they were given the chance to explain themselves, the teachers would be able to fix the problems,” Flakes said. “The more and more we’re not able to say what we want to say, the more fueled we are to want to say it. And it just keeps adding up, and adding up, until a bad situation happens. And we get blamed for being bad kids.”

Jones suggested that teachers employ restorative-justice practices instead of suspending students.

“As opposed to kicking them out, limiting their access to education, we should be giving them an opportunity to actually learn what they did,” Jones said, “giving them solutions on how to self-manage, handle stress. A lot of these teachers don’t realize the kind of trauma students go through at home.”

Jones suggested that the district take this approach on a larger scale by holding town-hall-style events, where school board members could hear directly from students about the problems affecting them.

“I can’t say it can be solved entirely, but it is their job to come up with the solution,” Jones said of the board.

Way back, decades before the current investigations and faked tests and lawsuits over the cleanup of the Hunters Point Naval Shipyard, people in southeastern San Francisco neighborhoods knew their ground and air were dirty. They worked on the Navy ships among the exposed asbestos, they breathed the emissions from the Pacific Gas and Electric Co. power plant, they heard the rumors about the nuclear waste poured down the sink at the radiation research lab just down the hill from public housing. Once, a brushfire smoldered for more than a month underground, releasing wild blue and green smoke into the sky. They knew about the toxic dust kicked up every time a construction project rolled through, the smell of the rendering plant, and the kids who snuck through the fences to sit by the power plant outflow pond on the shore of the San Francisco Bay.

They also knew help wouldn’t come from outside. “Government agencies have a poor track record of keeping residents safe and healthy during the cleanups,” one BayviewHunters Point community newsletter concluded. “Taking care of residents while the cleanup and construction work happens is the main concern.”

So the people who lived here became informed and active. They gathered their own data. They led so-called toxic tours to show people the sites that jeopardized community health. They prepared reports showing what environmental injustice looks like: A 10 percent asthma rate in 2004 among Bayview-Hunters Point residents that was almost twice the national average. One in 6 kids with asthma. A rate of birth defects, 44.3 per 1,000 births, much higher than the 33.1 per 1,000 countywide. Infant mortality rates 2.5 times higher than the rest of San Francisco’s.

They led town hall discussions, started newsletters covering everything from housing developments to what fish was safe to eat, and held a “People’s Earth Day.” And by the 1990s, they started to win. A proposal for a second power plant was shut down. The Port of San Francisco abandoned a proposal for a new shipping terminal. The Environmental Protection Agency and Navy started the Superfund cleanup process at the former naval shipyard. The EPA’s Brownfields Program authorized numerous localized cleanups. And in 2006, PG&E closed its Hunters Point power plant and the long road to site cleanup began.

This summer, I joined nine high-school and transitional-age kids from the neighborhood to tour their southeast San Francisco backyard, to walk toxic ground that connects the local fight for environmental justice with their futures. The young folks, interns with the group Literacy for Environmental Justice, are spending the summer gathering air quality data in their neighborhood, because as LEJ community programs manager Anthony Khalil tells them he’s learned in nearly two decades of work in this corner of the city, “it doesn’t mean anything until we can come together, get organized and share this data.”

Khalil co-captains the tour and drives the van. Riding shotgun is Raymond Tompkins, who is commonly referred to as “Dr. Raymond,” an elder environmental activist and former chemistry teacher who claims to be retired, but hasn’t stopped teaching yet.

Iride in the back with the interns. Present, but unmentioned, is a shared understanding that as the battle for clean air, soil and water carries on in the Bayview, another threat looms. We all know the numbers, and we all know we are touring a lot of toxic places whose cleanup — if it happens — and redevelopment will change this neighborhood’s character and displace many existing residents, including perhaps these kids.

The tour starts as we pull out of LEJ’s headquarters at the Candlestick Point Community Garden, where Tompkins sounds the first note about the future. “You have Candlestick,” he says. “In the next 20 years, that property is going to be worth $100 billion.”

“100 billion?!” I say, overly pronouncing the b.

“Yes, sir. Not million, billion,” Tompkins confirms.

Heading north, continuing through the neighborhoods that follow the shoreline in Bayview-Hunters Point, we wind around Yosemite Slough, where California State Parks and the EPA have worked for a decade to clean up toxic soil from nearly a century’s worth of sewage, dumping and industry. Behind chain-link construction fences, a trail now leads out past a few muddy artificial islands for nesting birds. The narrow inlet widens into a curving stretch of the bay, separating the public housing projects in the Double Rock neighborhood from the south edge of the Hunters Point Naval Shipyard.

The 500-acre shipyard is a Superfund site with a two-decades-long, scandal-ridden history of cleanup of radioactive material, most recently slowed down by the discovery last summer that a portion of the site’s clean soil sample results was falsified. Tompkins shows us the place where the blue-green fire burned and the former lab where workers poured nuclear waste down the sink. As we exit the shipyard, we see a giant magenta billboard with the logo for developer FivePoint in one corner and “Come Back Soon” in big letters.

A few minutes later, Khalil pulls the van onto a freshly paved surface that overlooks India Basin, the inlet north of the shipyard, and parks. The kids jump out of the van and stand firm in their Nikes on the cement yard adjacent to where the PG&E power plant’s cooling pond once stood. At the moment, the pavement is used as a community event space by the group Now Hunters Point. But that’s a temporary setup.

“What’s next?” Khalil asks the group. A bike rider casually coasts past in the distance toward the restored wetland park at Heron’s Head. “How do you develop this in a way that’s not only environmentally sustainable, but is just for existing communities?”

I don’t think the question is rhetorical, but it doesn’t garner an answer from the teenagers. Khalil continues, “I personally have this feeling, and I bet you all would agree with me, that we have a long way to go.”

“When we look at this site,” Tompkins says, “we not only look at the victory as well as the challenge of shutting down the power plant, but we also look at how the neighborhood develops and builds up.”

Listening to Tompkins, I think about the people who have lived here over the past seven decades and have made this place. Bayview-Hunters Point, the southeastern chunk of San Francisco east of Highway 101 (or more officially ZIP code 94124), is the city’s last major African-American neighborhood. Many of them moved here from the South to build ships during World War II and until the last few decades made up more than 65 percent of the neighborhood’s population. They were once relegated to this neighborhood by redlining and housing covenants, and they made the most of what they were given. They were and are blue-collar workers, who labor in factories and plants. They were and are artists who serve as culture keepers, amplifying the story of a people on the backside of the most scenic city in the world. Despite being disregarded by local and federal governing bodies — not to mention overly policed — the effort put forth by the people who care about this community laid the foundation for what’s next in southeast San Francisco.

The official “next” includes more than 13,000 new homes split between two major

DO PARKS PUSH PEOPLE OUT?

Parks improve health and fight climate change. But not all parks affect a community in the same way — and the question is: ‘Who’s it for?’

Pendarvis Harshaw wrote this story while participating in the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism 2018 California Fellowship

developments. At least 75 percent of those homes will sell as market-rate luxury units, which will more than double the number of housing units in Bayview-Hunters Point. So once it’s cleaned up, who will live here in two decades? Who will shop in the planned 700,000 square feet of commercial and retail space and work in the 3 million square feet of research and development space between Candlestick Point and the Bayview? Who, a lot of residents ask when they look at those numbers, is this cleanup really for?

I got a hint after I plugged the shipyard’s developer, FivePoint, into an Internet search query and started to get targeted email and social media advertisements for tours of their new luxury homes. The marketing images show modern glass-andearth-tone housing, with just a couple of horizontal wooden slats on the exterior — because what says “new development” more than those damned wooden slats?

What this cleanup and overhaul is for, according to the city, is a once-in-a-generation development integrated fully into an urban ecological utopia. The city, developers and park advocates envision a 13-mile “Blue Greenway” from where the San Francisco Giants currently play baseball, at AT&T Park on China Basin, south to where they used to play, at Candlestick Park. “Think ‘Crissy Field meets the High Line,’” the San Francisco Parks Alliance page introducing the Blue Greenway plan reads, as an introduction to its park-and-nature-centric ambition for these neighborhoods. “Could an Overlooked Cove in San Francisco’s Bayview Become the Next Golden Gate Park?” a KQED headline asked in August.

Developer renderings for Candlestick, the Shipyard and India Basin show parks connecting all the new housing developments to each other and to the bay. The Blue Greenway map shows native plants and birds where once there were industrial plants and warehouses. Wetland-fringed shoreline parks feature prominently along the entire Blue Greenway, connecting residents to the regional goal of a restored San Francisco Bay. At 900 Innes Ave., a former industrial site now owned by the city’s Recreation and Parks Department, federal government brownfield grants will help clean up and fill the largest remaining gap in the San Francisco Bay Trail — connecting India Basin developer BUILD LLC’s proposed “Cove Terrace,” a “prominent public-private plaza, lined with active ground-floor restaurants and cafes,” to the India Basin Shoreline Park and a new public pier and kayak launch site.

The end of my toxics tour takes place just up the street from where that new pier will be. We stand in a group looking out at Heron’s Head Park, where the Bay Trail picks up again and leads out to the water. A few terns fly over the blue-green water of the former power plant cooling pond. The sound of the offshore breeze is overwhelmed by the noise of construction trucks laboring in the distance, building a future for this neighborhood that looks nothing like what it is now.

“Who is it for?” Tompkins asks.

Marie Harrison, who has “lived, worked and played” in the Bayview since she first moved there as a teenager in the late 1960s, says that whoever the greening of the neighborhood is for, it’s not for her or her children and grandchil

Illustration by Emeric L. Kennard

dren. “They call it ‘green’ to give it a more natural kind of a feel,” she told me by phone from Stockton, where she moved two years ago. “To me, it’s more or less the idea of moving folks out and replacing them with new folks. With us in particular, it’s all about gentrification. I don’t care what you call it. You can dress it up and give it a new name if you like. But it still boils down to gentrification.”

Academics have coined the term “green gentrification” to describe the phenomenon in which environmental cleanup, restoration and neighborhood greening prepare the ground for displacement of existing communities. It sums up what some residents say is beginning to happen in southeastern San Francisco, and how more universally the arrival of parks or cleanup of legacy pollution isn’t always fully welcome. For some, new parks can feel no different than tech shuttle stops or gastropubs: a signal that they are about to see a lot of richer, whiter neighbors. Green gentrification has already happened, or is a source of tension, in urban enclaves around the United States.

Along the Los Angeles River, for example, community organizations have formed to fight riverside gentrification as the city maps out restoration of the 51-mile river path. In Washington, D.C., longtime residents of the Anacostia River have filed a class action lawsuit against the city, claiming its plans to “alter land use” and lure millennials to the area through luxury waterfront housing and parks constitutes discrimination against the current, older black community. In the recent Resilient by Design competition around the San Francisco Bay, designers proposed community housing trusts to protect residents from displacement as the region deals with sea level rise. In perhaps the most famous case, the High Line in New York City transformed an abandoned railway to a green pathway park, changing the neighborhood character entirely. “The High Line,” a New York Times op-ed by Jeremiah Moss, author of Vanishing New York, declared, “has become a tourist-clogged catwalk and a catalyst for some of the most rapid gentrification in the city’s history.”

Even the High Line’s developers now say their project is something of a cautionary tale; in 2017, High Line Executive Director Robert Hammond started a website called The High Line Network to advise how similar projects might restore land without disrupting surrounding neighborhoods. In a 2017 interview with Fast Company, Hammond said, “When we opened, we realized the local community wasn’t coming to the

S.F.’s Southeast Might Be Site of ‘Green Gentrification’

GREEN ENOUGH from Page 6

park, and the three main reasons were, they felt it wasn’t built for them, they didn’t see people like them there, and they didn’t like the programming.”

It’s not that parks necessarily cause gentrification. But the way they’re designed and built hints at the future of the neighborhood, as evidenced by the ambivalent attitude toward the Blue Greenway I heard from the longtime Bayview-Hunters Point activists, residents, and community organization members and leaders. Look at those redevelopment drawings closely and ask who they’re for, and one’s whole perspective might shift. When Tompkins was highlighting the capital-B-billion-dollar value of that shipyard development, he was calling our attention to the big-picture forces shaping the future here and what it likely means for people who live here now, especially the renters who make up 48 percent of the Bayview-Hunters Point ZIP code.

“Parks are not discrete spaces,” says UC Santa Cruz sociologist Lindsey Dillon, who has spent more than a decade researching environmental justice in Hunters Point. “If you build parks but are not protecting people from market forces, which in San Francisco are so rampant, then parks are going to become unwitting participants in displacement. It’s not about intentionality, or about parks per se. It’s about urban planning more broadly.”

In other words: Of course people want parks in their neighborhoods. But they told me repeatedly that they want the parks to be built for them. At the most basic level, that means proceeding with extreme thoughtfulness. It means, Bayview activists say, beginning with a toxic cleanup that hews to the same standards as those in Crissy Field, San Francisco’s 78 percent white Marina District. To people like Marie Harrison, it means incorporating job training for neighborhood residents in park development, designing parks with widespread local consensus and building them with local workers. And it means not conceiving of them as amenities to increase the sales point on soon-to-be-built luxury housing, as some Bayview residents told me they see the Blue Greenway’s parks.

“It would be positive if they cleaned up the parks and made them really nice and left open space, because it used to be a community of children,” Harrison says. “Unfortunately, the plan is to tear down and make walkways. To tear down all of the old buildings, to partially clean — or clean what they only have to. Put grass over it. And make a few docks and restaurants where people with boats from as far away as Oakland, Richmond and San Jose can sail up and pull over at Innes Avenue and have lunch or dinner. Nice restaurants and music areas, stroll through the wetlands and that kind of thing. And I’m thinking, ‘Wow. How many folks do you know that live in public housing, personally? And how many of them do you know own boats?’”

The complexity of remaking the Bayview-Hunters Point shoreline can’t be overstated, with multiple Superfund and Brownfields cleanup projects underway and three commercial developers, at least half a dozen city agencies, numerous advocacy organizations and the public all involved. The Blue Greenway has been intertwined with the redevelopment since the city, under then-Mayor Gavin Newsom, launched a Blue Greenway task force in 2005 and tried to include a wide swath of input from interested parties: more than 16 public agencies, more than 40 neighborhood associations, nonprofit entities — including environmental advocates SPUR, the Bay Trail and the Trust for Public Land — businesses and concerned residents. Among the many goals laid out in the Blue Greenway task force document “Vision and Road Map to Implementation” is “build community support.” It’s stressed repeatedly.

The San Francisco Parks Alliance (the driving force behind the Blue Greenway), the developers Lennar and BUILD, and the San Francisco Recreation and Parks Department have held hundreds of community meetings over the last decade. They say they’ve shaped their plans accordingly.

“I don’t think our organization thinks that investing in a neighborhood in a positive way creates displacement,” S.F. Parks Alliance Chief Executive Officer Drew Becher told me. “It’s like people saying you shouldn’t have nice things.”

The Parks Alliance, a nonprofit that advocates for the city’s parks, has helped secure more than $38 million for the Blue Greenway. Becher says the Alliance has invested in numerous community gardens and residential parks in San Francisco and seen, in fact, increased sense of community and no displacement. That’s what he expects now from the redevelopment of southeastern San Francisco, he told me.

“The Blue Greenway was made to benefit every neighborhood it touches and the entire city,” Becher said. “I strongly believe that every community wants to have great open space, and that’s what we’re advocating for.”

Ultimately, Santa Cruz sociologist Dillon says, whoever will feel represented by the Blue Greenway comes down to who thinks their concerns were addressed. At this point, Dillon says about who feels heard, “Longtime black or southeast Asian Bayview residents, probably not — no one that I know feels that way.” One of Dillon’s dissertation chapters, which she’s now turning into a book chapter, focuses on attitudes toward Heron’s Head, the restored wetland park built on top of the cleaned-up rubble of a shipping terminal. Conservation groups that have helped steward the park through its restoration see it as an environmental justice victory, a place where birds and native plants have conquered formerly toxic waste and where it’s surprising that more local residents don’t visit. Conservationists, Dillon writes, tend to see the nature in the park as redemptive, purifying, separate from the industrial or human processes in the surrounding neighborhoods. Many local residents Dillon interviews, though, don’t separate the park’s long, complicated history — which they’ve lived through and been a part of — from its present so easily.

“To my mind,” she writes, “these diverging opinions of the wetlands also reveal the complex relationship between the nature projects and the market-driven redevelopment process in Bayview-Hunters Point, which many residents experience as a form of displacement, and connect with a longer history of racism in San Francisco.”

Longtime Bayview-Hunters Point resident Harrison explained divisions within the community this way: “When you sit a room full of poor folks on one side and homeowners on the other side, who are trying to bring all of this quote ‘greening’ into our areas, and trying to pass if off as something that’s going to be good and healthy for you, and you can’t see through that? And I’m saying, ‘Good Lord! We’re black, we’re not stupid.’”

You can ask the same questions of all redevelopment projects, green and otherwise. Who’s making the decisions, and who’s getting what they want, and who is being represented, and whose urban planning aesthetic is the priority?

Staff for San Francisco Board of Supervisors President Malia Cohen, who has represented Bayview-Hunters Point for the last eight years and is described on the Blue Greenway website as a “dedicated champion of the Blue Greenway,” did not respond to repeated requests to discuss the project.

San Francisco isn’t alone in facing these questions. The Bay Area’s housing crisis and high number of renters make residents here particularly susceptible to displacement of any kind. From restoration and park enhancement on the Guadalupe River in San Jose to street tree planting in East Palo Alto, to shoreline restoration and creek daylighting projects throughout Alameda and Contra Costa counties, the same question hangs over the work: Who is this for?

Across the bay from San Francisco, in the flatlands of Richmond, a woman named Toody Maher stands in Elm Playlot wearing a shirt that reads “Pogo Park” on the lapel. “We’re a nonprofit in Richmond,” says Maher, the organization’s executive director. “We worked with community residents to reclaim this park.”

Maher is in the green picnic area as she describes what the park used to be like. “First of all, all of the houses around the park were boarded up and abandoned,” she says. “And people were squatting and living in them, and men were coming to the park all day to just drink. The park was nothing but broken glass. People used to bring their dogs to fight or train.”

She says the city installed a quarter of a million dollars’ worth of new play equipment in the early 2000s, “and within weeks, people tried to burn it down.”

Then Maher’s Pogo Park came and announced its interest in adopting the park from the city. They signed an agreement, allowing Pogo Park to work with the city closely, but, as Maher says, “We were allowed to reimagine the park with the community.” This let Pogo Park employees and local residents design the park’s barbecue grills, trash cans and even a custom fence with cutout profiles of the people who worked on it. They designed it all at a local fabrication laboratory — the same one that made the humongous glove in the outfield of the Giants ballpark in San Francisco, overlooking the northern limit of the pro

Photos courtesy of Pogo Park

Richmond residents helped design and build the amenities at Elm Playlot — including a fence with profiles of those who helped build the park — as well as create the programming for kids and adults. Programs included a small-animal petting zoo and free eye exams.

posed Blue Greenway.

Inside the Pogo Park office in Richmond, which was once an abandoned house adjacent to the park, there are photos of community members welding the equipment for the park. “We bought the house next to the park, and got a $300 fridge from craigslist, and started serving lunches out of it,” Maher says. “We’ve served like 12,000 meals.” Pop-up events helped bring the park to life, slowly building momentum in the community. In 2006, California voters approved Proposition 84, a $5.4 billion bond that included $490 million for park improvements, and Pogo Park won a $2 million grant from the state to build the park the way Maher says all parks should be built — involving the community in every step from start to finish.

Pogo Park’s head of research, Joe Griffin, explained how the towering plane trees in the park stand as a metaphor for Pogo Park’s approach to working with the community. The trees signal who the park is for. “It wasn’t just replacing the beauty that’s already in the neighborhood, but adding to it and uncovering it, so it could actually grow,” he says. “Which is the same thing we’re trying to do with the community itself: We’re not trying to replace people, we’re trying to work with the strengths that we have.”

Southeast SF/Blue Greenway

Richmond/Elm Playlot

Census tract boundaries Study area

70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 Black Asian/Pacific Islander 2000 Percentage of Population >

Hispanic 2016 White

Southeast SF 2000 2016 Total Population 19,572.00 20,613.00 Bachelor's Degree 10.7% 26.4% Poverty 27.4% 24.4% Renters 57.7% 56.2% Average of Median Household Incomes $58,509 $58,441

Census tract boundaries Study area

70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 Black Asian/Pacific Islander 2000 Percentage of Population > Hispanic 2016 White

Census Tract 3760 Total Population Bachelor's Degree Poverty Renters Median Household Income

2000 2016 5,959.00 5,547.00 5.2% 11.5% 23.8% 27.4% 64.3 % 69.7% $37,786 W hat’s happened in Richmond’s Elm Playlot also has a name in academic circles. In a 2012 paper about environmental gentrification in Brooklyn, N.Y., Winifred Curran and SUNY Buffalo geographer Trina Hamilton looked at what they describe as a different model of urban redevelopment. In the Greenpoint community, longtime residents were actively involved in reshaping their neighborhood. “Neighborhood residents and business owners seem to be advocating a strategy we call ‘just green enough,’” Curran and Hamilton wrote, “in order to achieve environmental remediation without environmental gentrification.” The phrase has become a rallying cry for many community advocates.

“The ‘just green enough’ strategy depends on the willingness of planners and local stakeholders to design green space projects that are explicitly shaped by community concerns, needs, and desires rather than either conventional urban design formulae or ecological restoration approaches,” UC Berkeley College of Environmental Design Dean Jennifer Wolch and colleagues Jason Byrne and Joshua Newell wrote in a journal article in 2014. In a conversation at her office in Berkeley, Calif., Wolch told me that it’s not just about drawing up blueprints for housing and showing up from another part of the city to plant native plants. “Part of the process has been heavy community outreach,” she said.

As environmental justice has become more explicitly part of legislation, the calculus in other developments has started to change. I talked to Rico Mastrodonato, a senior government relations manager at the Trust for Public Land, who helped write equity policies into the state’s newly approved park funding bond, Proposition 68. Mastrodonato is not convinced that creating parks in urban areas causes displacement. A resident of the Mission District for the first 20 years of the tech boom, he thinks San Francisco’s gentrification issue has more to do with skyrocketing tech salaries and a lack of renter protections. “Parks are not amenities,” he says. “They help lower emissions that contribute to climate change. They help the social fabric of communities, and they provide recreational and quality-of-life benefits that are extremely important.”

But he does note that community involvement in the development of urban parks is essential: “If you don’t have community involvement in the park, it’s a failure. The park has to be a reflection of the community. They have to help with the design of the park. If you get that, and you really take seriously community participation, then they take ownership over it. They care about helping to maintain it.”

Tonie Lee, who works with Maher at Pogo Park, is one of those community members photographed using welding tools to build pieces for the park. Lee said she used to play in the park as a kid; she’s happy with how the park has changed and how the formerly boarded-up houses in the surrounding community are now housing families instead of vagrant drug users. But she has noticed that even positive change comes with a cost.

“This house right here was up for sale,” says Lee, pointing to a building just across the street. “On their website and on their flyers, they included the park as promotion to sell their place.” She was dismayed.

“That was one of our big things, like, ‘Really, they’re using it as advertisement?’ They never did come and even give a dollar as a donation or anything, but you’re using it to promote the sale of your place?”

It’s hard in some ways to compare central Richmond and southeastern San Francisco. There are enormous market forces and decades of individual history acting on each. But these tensions around housing, parks and the future are shared. It was striking to me that one community has mostly embraced its park, while another community continues to organize to prevent the future “green” vision from arriving. (Various Bayview-Hunters Point community groups plan to create a “Save Bayview Hunters Point Coalition” specifically to fight gentrification in the future Blue Greenway.) It was striking to me that in Richmond, Pogo Park set up in a house next to the park and asked community members to weld playground equipment, while in San Francisco, Marie Harrison told me, one park hired an outsider to paint African-motif art on the walls. Maybe you can’t directly compare the neighborhoods or their parks. But the more you compare the process, the way they’ve gone about building a greener future, the more it’s clear who they’re building for.

Afew days after visiting Pogo Park, I met with Joe Griffin at a cafe in Berkeley. In addition to his Pogo Park role, Griffin is a doctoral candidate at UC Berkeley’s Institute of Urban and Regional Development. He says he hasn’t seen Pogo Park mentioned in any real estate ads, but he’s interested in seeing more resources come to the community — so as long as it’s done properly: “We want people to come and invest, but not at the cost of displacement of all the families. ... You see so many other neighborhoods where they’re not being able to enjoy the fruits of their labor.”

Much like Bayview-Hunters Point across the bay, the community around Richmond’s Pogo Park has seen its share of environmental injustices. It’s in Richmond’s Iron Triangle — where there’s a crossing of three train tracks. Toxic clouds from the Chevron Richmond Refinery can float by with a simple gust of wind. The city and residents sued the refinery for emissions released during a fire in August 2012; the case was settled earlier this year, with Chevron agreeing to pay $5 million.

“All of those environmental pollutants are in the area, but to an extent, it’s become normalized,” Griffin says. “I grew up in Richmond; everyone had asthma. I went to college, everyone doesn’t have asthma. What’s going on?”

Griffin says the focus of his studies at UC Berkeley is the health impact of the public redevelopment of Pogo Park, particularly toxic stress (suffered for elongated periods, often during formative years) within members of the community. He plans on using mixed methods, data and experiences, to tell the full story. He’s just getting started collecting statistical data and where he’ll present his findings is still to be determined. But it will definitely include a presentation at the park, open to all community members who are available to come.

Before we parted ways, I had to ask Griffin the question at the center of my study: How do you revitalize a neighborhood and keep people there?

“That’s a huge question. ... I think that plays into a lot of the fear when you see something in a neighborhood revitalizing,” says Griffin. “In the neighborhood I’m from, when we started seeing bike lanes, we were like, ‘Wait a minute, why are there bike lanes there? Why did they fix those light poles and what is that bench doing here?’ You get scared.”

He says that even though working to improve the community could price out longtime residents, it didn’t stop the Pogo Park team from making the community better. It was their project.

And then he noted the most important piece to the puzzle about including a community in redevelopment plans: “It can have an effect on the social environment — how people are connected to each other.” Griffin turned into a bit of cafe orator as he continued. “And it can affect the economic environment — that’s the importance of having staff members who are also local residents — and being able to pay them, so it’s not just a nights and weekends thing. This is a part of what they do and how they feel financially secure in the neighborhood. It affects place in a lot of different ways.”