13 minute read

Claims about rent control derived from incomplete research.SHAKY FOUNDATION?

Even Today, Academia Knows Little About Rent Control

Data-driven research ally have data to back up their claims,” she said. to support policy Partly, that’s because good data can be hard to come by. A well-known study in arguments is lacking Cambridge, Mass., for example, drew no direct conclusions about whether a landor implemented has dwarfed the number kinds of rent control.” mark 1994 repeal of rent control actually By Nathan Collins // Public Press affected rents — because the researchers

Advertisement

As Californians battled this fall over a and Massachusetts Institute of Technology ballot measure to allow cities much economist Parag Parthak. A 2007 study wider leeway to impose all sorts of that did focus on rents themselves relied on rent control, both sides of the debate surveying a sample of renters rather than threw around citations to academic papers, complete, official records. And then there’s economic studies and seemingly compelling the San Francisco study, which cobbled tostatistics. The studies, they said, proved gether the needed data from three different that restricting what landlords may charge sources. tenants either helps preserve affordable In many cases, especially in older studies, housing or exacerbates the crisis by driving the data did not allow direct comparisons owners out of the rental business between different kinds of rent conand killing off construction. Both sides were wrong. There just isn’t enough careful, data-driven economic research to definitively answer questions about rent control HOUSING SOLUTIONS trol, or between rent-controlled and market-rate homes. As a result, Diamond said, those studies may say more about the circumstances — social, economic and political — as it applies to the here and now. in one particular place and time

There are two things we know than they do about rent control. for sure — and that researchers Several studies of rent control in agree on — about rent control: It Europe during and shortly after keeps rents below market rates for those who have it and it helps keep people in their homes longer. There is also evidence that rent control Landlords vs. Renters World War II showed rent control could reduce rental housing stock (and the quality of what remained). But, Garcia said, those studies can shrink the supply of housing, at concerned “hard” rent controls that least in some cases. severely restricted and in some cases halted

That leaves open two of the most imporrent increases, and that bear little resemtant questions in a debate that stretches blance to any policy in place in California back decades: How do different rent control — meaning their conclusions probably do policies affect the supply of housing, and not apply. how does rent control in one place affect To a lesser extent, similar concerns may regional housing markets? apply to the recent San Francisco study.

As a review of research on rent control Although well regarded among researchers, and interviews with policy experts and it is still just one study of one policy at one economists suggest, there is much that point in time. “I think it’s useful, but it’s remains unclear. In the centuries — yes, one point,” Garcia said. centuries — since rent control began, the number of policies that have been proposed ASSESSING REGIONAL IMPACT could not find data on rents, said co-author of reliable studies of modern rent control, Another pressing problem is that it isn’t which researchers said number fewer than clear what rent control policies do on the half a dozen, although even on that number scale of individual blocks and neighborthere was some disagreement. hoods, what they do to other kinds of hous

Economists and policy experts say there ing or how one city’s policy might affect a is just not much data on rents and tenant regional housing market. If there are few and landlord decisions on which to base good studies of rent control generally, there quality research. On top of that, said David are even fewer of those kinds of spillover Sims, an economist at Brigham Young Unieffects. versity, academics have moved on to other, There are some hints, perhaps, from more novel questions in recent decades. research like Parthak and colleagues’ study Economists produced dozens of studies in Cambridge. They found that ending that of rent controls put in place after World city’s rent control, which had applied to all War II, but having reached some conclurentals, raised property values on other sions about those policies’ effects, the field homes in the city. But, again, the Cammoved on. Whatever the underlying reason, bridge policy is very different from anything researchers do not know enough — or at on the books in California. For one thing, least everything they would like to know — Cambridge’s law limited rent increases beabout what any one policy proposal is likely tween tenancies, a policy known as vacancy to do to housing costs in a city, a region or control. California’s Costa-Hawkins Rental a state. Housing Act outlawed vacancy control, but Proposition 10 would have done away with

EFFECT ON HOUSING SUPPLY that restriction had it passed, allowing San

Another consequence, as a recent Univermenting with the idea, if at all. sity of Southern California report suggests, Similarly, although it is possible that is that many of the most strident claims changing policy in one city affects housabout rent control may be based less on ing supply and prices in nearby cities, it solid research and more on the ideology remains less than clear what and how and self-interest of advocates who cite the large those effects would be. What would research. a rent control change in San Francisco do

“It’s an incredibly complex issue,” said to homes in the East Bay? “I would love to David Garcia, policy director at the Terner know more about spillovers, but that’s a Center for Housing Innovation at the very difficult problem empirically,” Sims University of California, Berkeley. “We said. “Measuring it is very hard.” don’t have really good research that tells us what actually happens when we do different SEARCH FOR ALTERNATIVES Francisco and other cities to start experi

The question of how rent control affects Another matter that is not well unthe housing supply is a case study in the derstood is sorting out who ends up in challenges rent control debates face: limited rent-controlled housing. Studies are few data and studies that, even if they were and might not apply to California, again reliable when published, no longer apply. because of policy differences.

The best evidence to date on one aspect But a deeper question — one that gets of housing supply — whether landlords reeven less attention in some debates — is move rental units from the market — comes whether there are alternatives beyond from a study that Stanford Graduate School variations on rent control itself, such as of Business economists Rebecca Diamond, “rolling” rent control, in which rent restricTimothy McQuade and Franklin Qian pubtions on newly developed homes kick in lished in 2018. That study concluded that after a waiting period of some years. The rent-controlled buildings in San Francisco Public Press reported in August that many were about 8 percent more likely to be rent control advocates and detractors have converted to for-sale tenancy-in-common not even thought enough about rolling rent buildings or condominiums compared with control to have an opinion about how it those that were not rent controlled. might work. A May 2018 Terner Center brief sug

STUDY USED DETAILED DATA gested two possibilities. In one, governments could use tax incentives to encour

Their approach is notable for two reaage property owners to create affordable sons. First, they relied on a “natural housing and preserve what is already out experiment,” that is, a change in the law there, similar to policies put in place in that created a test group as well as a very Seattle and Tacoma, Wash. Authorities similar control group to compare it with. could also create a statewide “anti-gouging” In 1994, San Francisco updated its rent orcap setting a maximum increase above dinance to bring owner-occupied buildings the Consumer Price Index and apply to all with four or fewer units under rent control, rental properties, regardless of when they but only those built before 1979, when city were built. That idea would be possible regulations were enacted. only if Costa-Hawkins is repealed by voters

Second, the team had detailed data, through Proposition 10 or by the Legislaincluding individuals’ address history from ture, if that fails. Infutor, property histories from DataQuick And there may be a deeper problem still, (now part of CoreLogic), and building perone that has received very little attention: mit and parcel histories from the San FranThe housing crisis California finds itself in cisco Office of Assessor-Recorder and the is much more complex than the problems Planning Department. From those data, of any one city and more complex than dethe researchers knew how long individuals bates about rent control itself. “Rent control lived at any one address and what hapis designed to solve a symptom — prices pened to a building after someone moved are high,” said Sims, the Brigham Young out. economist.

By putting those together, they could The problem, then, may be that not compare two groups of homes that were enough is being done, by governments or nearly the same, except that one was rent developers, to create new housing, and controlled and one was not — in other that efforts to do so are too local and too words, one of the cleanest possible ways to patchwork to solve what is fundamentally estimate the effects of housing supply. a regional problem. That the problem is

Unfortunately, in that regard, Diamond divided into small pieces when it requires a said, her study was almost alone. “I think wide-ranging solution, Sims said, “is what there are only a handful of papers that redrives this.”

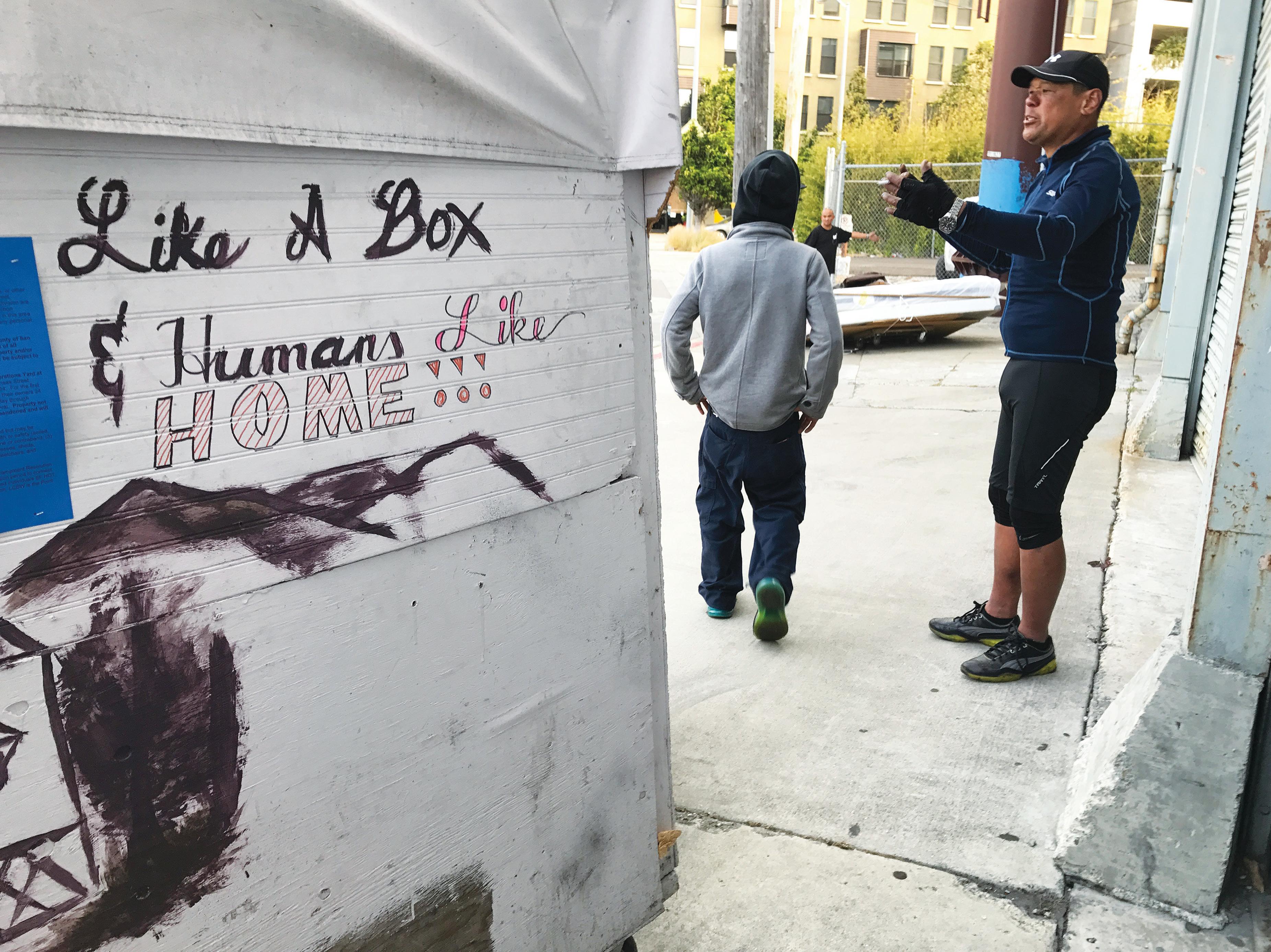

Photo by Judith Calson // Public Press

If implemented, Proposition C would direct money to homelessness outreach and prevention, as the city continues to clear encampments.

Homelessness Fund Might Render More Services if Measure Stands Also, companies leaving the city “would industries,” the report added.

PROP C from Page 1

homelessness programs. In a scenario where the annual revenue reached $250 million, the low-end projection, it would provide assistance an estimated 103,000 times in a 10-year period. This would be total services rendered, not unique individuals served. It counts people for as many times as they receive any type of housing or social service. • That estimate, however, is 40,000 more instances than the official 63,000 figure published by the controller’s office in

September. The city’s chief economist did not include the number of people who could receive mental and behavioral health services, a figure that Friedenbach said she got from the city’s former health director. The controller’s report did not explain the omission. • Friedenbach, executive director of the nonprofit Coalition on Homelessness, estimated that the public health department could provide mental and behavioral health services in about 4,000 instances per year over 10 years, and more if the tax revenue were higher. These services would absorb at least one-quarter of the Proposition C revenue.

BOARD CAN ADJUST SPENDING

Any predictions of the levels of service Proposition C would make possible should be treated as ballpark estimates, despite granular breakdowns contained in the math of the controller and the proponents.

The Board of Supervisors would be able to adjust how the additional tax revenue was spent, within limits, affecting the number of people who received certain types of housing or social services. Under California law, all local tax increases require voter approval. Because Proposition C has no sunset provision, its mandates would remain in effect unless repealed.

Proposition C, which was put on the ballot by signature petitions, has riven San Francisco’s political leadership and the city’s business and technology moguls. The measure’s supporters included Salesforce CEO Marc Benioff, U.S. Senator Dianne Feinstein, congresswomen Nancy Pelosi Phil Ting. It also had backing from the San Francisco Board of Supervisors’ progressive members, as well as new supervisors Rafael Mandelman and Vallie Brown. They argued that the scale and persistence of the homelessness crisis merited tapping the city’s deepest pockets for this additional funding.

THE OPPOSITION

The opposition was led by San Francisco Mayor London Breed, state lawmakers Scott Wiener and David Chiu, the Chamber of Commerce, venture capitalist Ron Conway and Twitter co-founder Jack Dorsey, who is also the CEO of Square. They claimed it would be a giant jobkiller and drive companies out, attract more homeless people, have no spending accountability and complicate future funding because of the lawsuit challenging all signature-driven tax measures.

The measure would raise the gross receipts tax on local businesses with annual revenues greater than $50 million. The tax would vary according to the type of business — 0.175 percent to 0.690 percent — and would generate between $250 million and $300 million in additional PROP. C BENEFICIARIES ECLIPSE JOBS LOST Over the next 10 years, Proposition C would fund housing and services in 103,000 instances. Net jobs lost would be fewer than 400.

40,000 SERVICES RENDERED

35,000

30,000

25,000

20,000

15,000

10,000

5,000

0

Jobs lost Shelter *Mental beds health care Housing Homelessness prevention services

EMPLOYMENT HOMELESSNESS PROGRAMS TYPE OF IMPACT

Graphic by Noah Arroyo, Reid Brown // Public Press Sources: San Francisco controller’s office; *mental health estimates from former director, S.F. Public Health Department tax revenue each year, according to the controller’s report, which was assembled by the city’s chief economist, Ted Egan.

The tax would affect between 300 and 400 local businesses. They make up 3 percent of companies paying the gross receipts tax, and have paid 57 percent of all business tax revenue citywide. With Proposition C, their share would grow to 67 percent. This would make San Francisco’s business tax structure more progressive, hitting larger companies harder than smaller ones, the controller’s report concluded.

But the additional gross receipts tax could cause an estimated net loss of between 725 and 875 jobs citywide over the next 20 years, the report said, adding that it was “difficult to quantify” whether companies might relocate all or some of their operations.

“A significant negative economic risk not included in our direct analysis is that larger businesses may relocate or expand in other cities as a result of the tax, which will raise the cost of doing business in San Francisco,” the report cautioned. “To the extent that this relocation occurs, economic impacts could be more negative than we project.”

have negative multiplier effects on other and Jackie Speier, and state Assemblyman

But it also noted that last year’s cutting of the top corporate tax rate from 35 percent to 21 percent “would outweigh the proposed 0.5% gross receipts tax increase for the majority” of affected companies.

And not all of the controller’s economic forecasts of the new tax on the local economy were negative.

“Additional positive factors, not quantified in this analysis, include an expected improvement in health outcomes, a reduction in acute service costs, and an attractiveness of the City, because of the likely

PROP C continued on Page 11

NEW TAX WOULD BRUISE MANY INDUSTRIES, HELP SOME In the next 20 years, the gross receipts tax from Proposition C would hurt retail trade most, while causing growth in health care and social assistance. Only major industries are shown.

JOB LOSSES JOB GAINS

-183

-146 -133 -131

-117

-95 -86 -84 -70

-49 -39 -33 -32 -32 -29 State and local government Health care and social assistance Retail trade

Accommodation and food services

Finance and insurance

Professional, scientific, and technical services

Management of companies and enterprises Construction

Information

Other services (except public administration) Admin, support, waste management and remediation

Real estate and rental and leasing Arts, entertainment, and recreation

Manufacturing Wholesale trade