amenities are first class,

Now with two

excellent and the residents can’t help but enjoy

El Castillo and La Secoya de El Castillo provide

place to enjoy your senior years.

years of

start now.

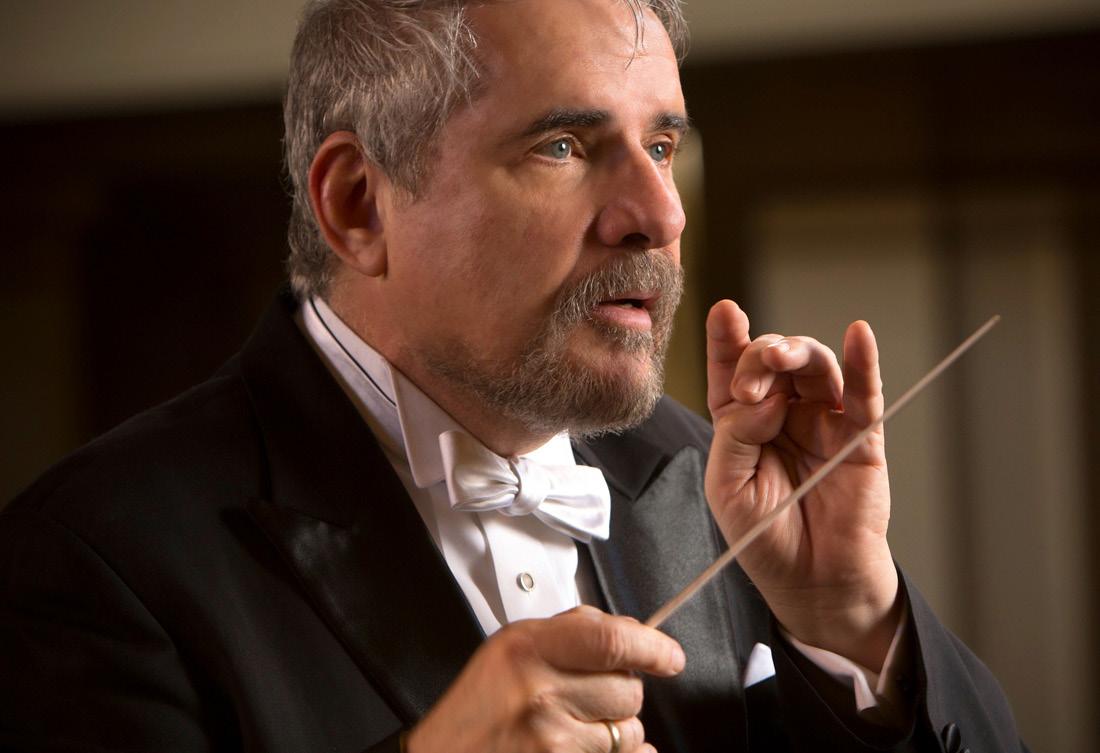

It is with great enthusiasm that I welcome you to this season of masterworks, new works, guest artists and conductors, women of distinction, renowned string quartets, and the Pro Musica Orchestra and Baroque Ensemble. We invite you to join us over the winter holidays for an exciting Bach Festival, become a member of our Coda Circle, and take part in artist dinners to experience the music beyond the concert hall and meet our visiting and local musicians.

At Pro Musica, we value and appreciate our role in the community. We provide free public education and outreach programs to increase familiarity and access to great music, “Meet the Music” lectures before each orchestra concert at the Lensic, regular student field trips to orchestra concerts throughout the season, masterclasses and in-school visits from artists, and a Youth Concert digital library for teachers, students, and families. We are delighted to nurture young artists through our apprentice programs and we welcome two violinists and a stage manager to our program this season. We are grateful to you, our musicians, donors, business partners, and audience members for your support and participation with us.

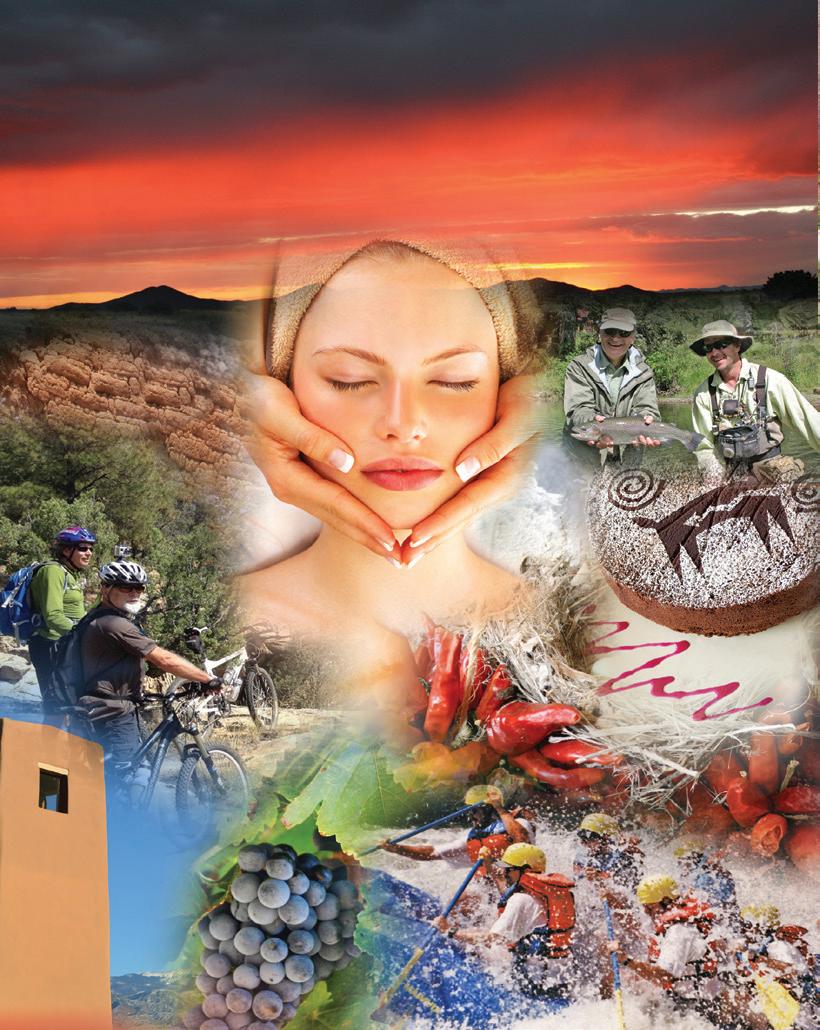

Together with you, we contribute to the rich arts culture of New Mexico, bring our community together, and support Santa Fe as a destination where amazing artists and audiences love to visit. I am grateful to our founders, staff members, volunteers, and our Board of Trustees for their dedication and excellence. And I thank you, our generous friends, for your support of classical music and Pro Musica!

Thank you Santa Fe for over 40 years of generous support! Back in the late 1970s, I started out on my musical journey, destination unknown. With a small ensemble of my friends, including my husband (and Pro Musica co-founder) Thomas O’Connor, we played free classical music concerts throughout New Mexico, including at senior centers, the public schools, the pueblos, and even the state’s penitentiary. Then Tom and I created a concert series in Santa Fe, and our touring ensemble was renamed Santa Fe Pro Musica. Gradually, our concerts evolved into three distinct concert series—orchestra music, chamber music, and baroque music—offering a wide variety of classical music experiences to an ever-growing audience. Pro Musica grew because of you!

And now we present Pro Musica’s 41 st season! Our Orchestra Series features the artistry of conductors Ransom Wilson, Robert Tweten, Sarah Ioannides, Mei-Ann Chen, and our conductor laureate Thomas O’Connor, presenting the works of the classical masters alongside the newest voices of the 21 st century. Our popular String Works Series brings five international string quartets to Santa Fe’s stages, including Quartetto di Cremona from Italy, the New York–based Escher Quartet, the German–based Schumann Quartet, the Danish Quartet (Vikings!), and the U.S.–based Dover Quartet. Our Baroque Series features both an action-packed Bach Festival and a more introspective concert experience for Holy Week.

Join Santa Fe Pro Musica as we enter our fifth decade of bringing together outstanding musicians to inspire audiences of all ages through the performance of great music!

CAROL REDMAN | MUSIC DIRECTOR

Welcome to the 2022–2023 season of spectacular music by Pro Musica! The season’s lineup of performances is incredibly diverse, from 17 th-century Baroque Bach to a 21 st-century contemporary commission by the gifted young composer/performer, Xavier Foley. Along with Pro Musica’s Board of Trustees, I am honored to be a part of your experience.

This program was conceived by a group of talented musicians under the creative genius of music director Carol Redman. Along with Carol, the program is being managed in the capable hands of executive director Andréa Cassutt and her skillful staff.

I would be remiss if I did not give a big shout-out to the jewel in our crown—the outstanding GRAMMY-nominated orchestra and each and every one of its musicians—who emphasize precision, brilliant interpretation, and pre-eminent musicality. And other performances in our treasure chest will be given by the Pro Musica Baroque Ensemble, Bach Ensemble, and five world-renowned string quartets.

We are truly grateful for the generosity you have demonstrated in your support of Pro Musica and look forward to your continued support of our future great programs for our community.

Looking forward to seeing you at performances!

SCOTT R. BAKER | PRESIDENT, PRO MUSICA BOARD OF TRUSTEES

Sep 21

Sep 23

Sep 24–25

Sep 25

Oct 23

Oct 30 |

Nov 5–6

Nov 17

Nov 2

Nov 4

6

Dec 21–24

Jan

Jan

Jan

ORCHESTRA CONCERTS

LENSIC PERFORMING ARTS CENTER

September 24–25 | Season Opening Orchestra Concert November 5–6 | Fall Orchestra Concert

January 28–29 | Winter Orchestra Concert

March 11–12 | Spring Orchestra Concert April 30 | Season Finale

STRING WORKS SERIES

NEW MEXICO MUSEUM OF ART | ST. FRANCIS AUDITORIUM

October 23 | Quartetto di Cremona

October 30 | Escher String Quartet with soprano Susanna Phillips November 17 | Schumann String Quartet

LENSIC PERFORMING ARTS CENTER

January 22 | Danish String Quartet February 12 | Dover Quartet

BAROQUE CONCERTS

NEW MEXICO MUSEUM OF ART | ST. FRANCIS AUDITORIUM December 21–24 and 29–30 | Pro Musica Bach Festival

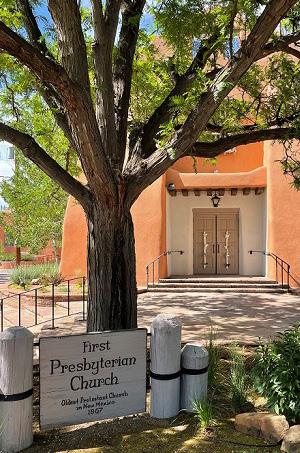

FIRST PRESBYTERIAN CHURCH April 1–2 | Baroque Holy Week

ARTIST DINNERS & RECEPTIONS

September 25 | New Mexico Museum of Art—Courtyard November 6 | Santacafé

January 22 | Santa Fe School of Cooking March 12 | Restaurant Martín

YOUTH CONCERT SERIES

September 23 November 4 January 27 March 10

COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT EVENTS

December 28 | Bach Exploration

January 22 | Danish String Quartet Masterclass February 13 | Dover Quartet Event TBD March | Xavier Foley Events TBD

CODA CIRCLE EVENTS

September 21 | Mozart’s Sinfonia Concertante November 2 | Conductor or Soloist—Who Takes the Lead?

January 25 | Earth—A Musical Reflection March 8 | Xavier Foley—Forging Unique Paths

All programs and artists are subject to change.

The Mission of Santa

Founded in 1980 by Thomas O’Connor,

Carol

Mexico

world-renowned

variety

an

Santa Fe Pro Musica has received many accolades, including a GRAMMY nomination, a five-year affiliation with the Smithsonian Institution, recognition for our decades-long support of women composers in classical music, and a successful, multifaceted community engagement program that encourages people of all ages to develop a life-long relationship with the power of music.

At CHRISTUS St. Vincent, the providers you know and trust have direct access to Mayo Clinic’s medical knowledge and expertise. This means, as a CHRISTUS St. Vincent patient, your expert providers can request a second opinion from Mayo Clinic specialists on your behalf and access Mayo Clinic’s research, diagnostics and treatment resources to address your unique medical needs.

This clinical collaboration allows you and your loved ones to get the comprehensive and compassionate care you need close to home, at no additional cost.

CHRISTUS St. Vincent and Mayo Clinic Working Together. Working for you.

CHRISTUS ST. VINCENT AND MAYO CLINIC

CHRISTUS ST. VINCENT AND MAYO CLINIC

The Overture to La Scala di Seta is scored for one flute, two oboes, two clarinets, one bassoon, two horns, and strings (6 minutes).

Rossini, the leading Italian composer of the early 19th century, composed 38 operas within 19 years. He possessed a keen musical wit, a gift for melody, and a flair for stage effect. Rossini’s one-act comic opera La Scala di Seta (The Silken Ladder), written in 1812, features a profusion of misguided lovers, suitors, tutors, and secret trysts in a whirlwind of events and misunderstandings. In the overture’s six minutes of music, Rossini captures the opera’s entire plot, including romance, bumbling antics, finger-wagging, and a chorus of chuckles and laughter. The action revolves around the heroine, Giulia, secretly married to Dorvil, who welcomes him every night into her room by letting down a silken ladder (la scala di seta) from her balcony.

Sinfonia Concertante in E-Flat Major, K. 364 is scored for solo violin and viola, with an orchestra composed of pairs of oboes and horns, with strings (30 minutes).

The sinfonia concertante was the Classical period’s successor to the Baroque concerto grosso, and is a synthesis of the classical symphonic structure with the Baroque concerto treatment of multiple solo instruments. Mozart’s Sinfonia Concertante, K. 364 is considered, though not confirmed, to date from the summer of 1779, after his return home to Salzburg from a trip to Paris where the sinfonia concertante form was especially popular.

During his years in Salzburg, Mozart played violin and composed five concertos for the instrument. Once he moved to Vienna (1781), he put away the violin and neither played nor composed any more concertos for it, preferring to play the viola in the famous string quartet with his friend Joseph Haydn and other distinguished musicians.

It is assumed Mozart wrote the demanding solo viola part in the Sinfonia Concertante for himself, and he took care to ensure that it would make a brilliant effect. The part is actually written in the key of D, with instructions to tune the instrument one half step higher to E-flat “and perhaps a shade sharp” so that it would stand out more effectively against the orchestra. It is not known for whom he wrote the solo violin part.

The first movement, Allegro maestoso (Fast, majestic), is full of thematic substance and variety. The second movement, Andante (Flowing), is a poignant dialogue between the two soloists. The Finale Molto vivace (Very lively) is filled with mischievous high spirits, using the wind instruments most effectively, and giving special prominence to the horns.

Shift, Change, Turn is scored for one flute, oboe, clarinet, bassoon, horn and trumpet, with timpani and strings (12 minutes).

Montgomery was born and raised in Manhattan’s Lower East Side. She is a violinist in addition to a composer, and studied at the Juilliard School, New York University, and Princeton University. In 2019, the New York Philharmonic selected her as one of the composers for their Project 19, marking the centennial of the ratification of the 19th Amendment, granting equal voting rights for women in the United States.

Montgomery’s music interweaves classical music with elements of popular music and improvisation, creating an especially 21st-century American sound. Her music has been described as “turbulent, wildly colorful and exploding with life” (The Washington Post).

Her work Shift, Change, Turn was commissioned in 2019 by the Orpheus and the Saint Paul Chamber Orchestras. She writes that “Shift, Change, Turn is my opportunity to contribute to the tradition of writing a piece based on the seasons, as change and rotation is something that we all experience as humans.”

Symphony No. 1 in D Major, Op. 25, “Classical” is scored for pairs of flutes, oboes, clarinets, bassoons, horns, and trumpets, with timpani and strings (15 minutes).

Prokofiev wrote his first symphony in the summer of 1917, soon after his graduation from the St. Petersburg Conservatory. A relatively untroubled work, his Classical Symphony is 18th century in its form and 20th century in its idiom. Prokofiev wrote that “As soon as I began to progress in my work, I rechristened it the Classical Symphony, first, because it sounded much more simple, and second—out of pure mischief—‘to tease the geese’ [i.e., the academics who had attacked him for his modernity] and in the secret hope that eventually the symphony would become a classic.” With its impish humor, impeccable craftsmanship, and charming melodies, the Classical Symphony is like a breath of fresh air and has remained one of the composer’s most popular works.

The first movement, Allegro (Fast), is brilliant, playful, and full of good cheer. The second movement, Larghetto (A little slow), is relaxed but with a certain dignity until Prokofiev presents a long lyrical melody in the very highest stratosphere, mocking what we expect a warmly romantic theme to be. Prokofiev again surprises us in the third movement, Gavotte. Non troppo allegro (not too fast), where he replaces the expected courtly menuet with a heavy old country dance that features foot stamping and country bagpipes. About the Finale. Molto vivace (Very fast), Prokofiev remarked that it was “lively and blithe enough for there to be a complete absence of minor triads in the whole movement, only major ones … the only thing I was concerned with was that its gaiety might border on the indecently irresponsible.”

The Italian-born Boccherini achieved widespread fame in his day both as a virtuoso cellist and as a prolific composer. He wrote almost 100 string quartets and over 200 chamber works for various other instrumentations.

Boccherini’s String Quartet in C Major, G. 164 was published in 1761 as part of a set of six quartets dedicated to “Amateurs and Connoisseurs of Music.” This quartet, like the others in the set, contains three movements: a fast first movement, a slow middle movement, and a closing minuet. One trend during the late Classical period was to conclude a work with calm elegance meant to assuage any heightened emotions the listeners might have experienced, quite a departure from the exhilarating finales that today’s audiences expect.

Boccherini launches the spirited first movement (Allegro con spirito) with a forthright chord, followed by a gradual descent of sequences, with an undercurrent of pulsing repeated notes that lend energy and forward motion. He then introduces the minor mode and more sinuous lines before the merriness returns. The brief slow movement (Largo, broad) contains a wealth of ideas—melancholy chromaticism, gentle sighing leaps, paired triplets, and descending gestures answered by emphatic chords. The concluding minuet swings along, relying on loud-soft contrasts. After a more introspective middle section, the cheerful minuet returns to round off the movement.

Giuseppe Verdi (1813–1901)Best known for his operas La Traviata, Falstaff, and Aida, the Italian Romantic composer Giuseppe Verdi is considered the preeminent opera composer of the 19th century. In the spring of 1873, while living out of a hotel room in Naples, Italy, Verdi found himself with some unexpected free time as the production of his opera Aida had encountered setbacks. During this downtime, Verdi wrote his first and only string quartet.

This quartet contains wonderful melodic ideas, skillful string writing, and, if one listens carefully, quotes from his operas. The first movement, Allegro (Fast), centers around a melancholy wisp of an idea. The second movement, Andantino (Flowing), contrasts graceful outer sections with an agitated middle section. The extroverted third movement, Prestissimo (Very fast), begins appropriately at a lightning speed and imparts an impish offkilter effect with many irregular phrase lengths. The contrasting middle section has the cello singing an expressive melody to light pizzicato

accompaniment. Verdi shows off his contrapuntal prowess in the finale, Scherzo Fuga Allegro assai mosso (Fast, with much motion). This is a gossamer fugue, however, not majestic nor weighty as we’ve come to expect. The composer himself labels it “Scherzo Fuga,” employing the term scherzo in its original meaning of a merry jest.

Giacomo Puccini (1858–1924) Crisantemi, SC 65 (6 minutes)

Puccini was born into a Tuscan family of church musicians and it was expected that the young boy would succeed his father as the music director at the San Martino Cathedral, a position that had been held for four generations by a Puccini family member. After seeing a performance of Verdi’s Aida, the 15-year-old Giacomo was inspired to write opera, and ultimately became one of the world’s most successful and famous opera composers.

In the United States chrysanthemums (crisantemi) are usually regarded as cheerful flowers. However, in many Asian and European countries, chrysanthemums symbolize death. It is in this context that Puccini wrote Crisantemi, a dark-hued elegy written in response to the death (1890) of his friend, the Duke of Savoy. This work is based on two plaintive melodies. The first is restless, building its power from chromatic figures moving in contrary motion. The second is a mournful theme that sounds over accompanying pulsations. A brief return of the opening music closes the lament.

Ottorino Respighi (1879–1936) Quartet No. 3 in D Major, P. 53 (32 minutes)

Respighi was born in Bologna, Italy, and studied violin, piano, and composition at the local music school. After a brief sojourn to Russia in 1900, where he played principal viola in the Imperial Opera Orchestra and studied composition with Rimsky-Korsakov, he lived most of his life in Rome. He is most famous for his colorful orchestral works, especially his tone poems (Fountains of Rome, Pines of Rome), though he also wrote operas, ballets, and chamber music, including eight string quartets.

The String Quartet No. 3 dates from 1904. The opening Allegro (Fast) begins with an uplifting main theme followed by a playful syncopated second theme, providing contrast with its leaps and silences. The highly chromatic slow movement unfolds as a moody theme and variations. The third movement Intermezzo opens with a tender introductory gesture that launches into a lightly scampering scherzo (joke). The finale, Allegro (Fast), features a galloping, almost frantic, main theme as if hurtling through a dark woods at night. The contrasting second theme provides a calming, hopeful respite. Respighi pulls us through the terror and the piece ends triumphantly.

From 1790 to 1792 Haydn resided in London where his latest string quartets, including Op. 71, were fêted by the nobility and loudly cheered by the clamoring crowds. These adventuresome quartets are as if “Haydn were pushing open a door through which Beethoven was to pass” (Rosemary Hughes, Haydn String Quartets, 1966).

Haydn’s Quartet, Op. 71, No. 2, begins with a slow introduction (Adagio, at ease) that juxtaposes explosive chords with gentle phrases. The following Allegro (Fast) is built upon a frolicking theme interspersed with references to the gentle phrases of the introduction. The Adagio cantabile (in a singing style) is a noble and richly decorated song. The Menuetto is a jocular blend of the elegant and the rustic. The Finale is built upon a theme of restraint, which by the end is overcome with hilarious merrymaking.

Quartet No. 2 in F-Sharp Minor, Op. 10 is scored for soprano and string quartet (30 minutes).

Schoenberg’s Quartet No. 2 was written during 1908 and reflects a turbulent time in his life when his music had been soundly rejected by the critics, and his wife left him for another man. Tellingly, this quartet is dedicated to his wife.

This work is colored with the extended tonal palette of the late Romantic period with suggestions of the revolutionary twelve-tone system for which Schoenberg became defined. The first movement Mäßig (Moderate) is emotionally complex. Based upon a sighing figure, it ranges from yearning to anguish to outrage. The second movement, Sehr rasch (Very brisk), is skittishly playful, verging on the macabre, with veiled references to a Viennese street-song, “Ach du lieber Augustin.” For the last two movements, Schoenberg includes a soprano reciting poems by Stefan George (1868–1933). From the third movement, Litanei Langsam (Litany. Slow), we hear despair—“Long was the journey, my limbs are weary/ The shrines are empty, only anguish is full.” And from the fourth movement, Entrückung Sehr langsam (Rapture. Very slowly), we hear resignation—“I am only a spark of the holy fire/ I am only a whisper of the holy voice.”

Il tramonto is scored for soprano and string quartet (15 minutes).

The Italian composer Respighi set to music several poems written by the English Romantic poet Percy Bysshe Shelley (1792–1822), including The Sunset, translated into Italian (Il tramonto) in 1921 by Roberto Ascoli. The poem describes a young couple on a walk, hoping to glimpse the sunset. Yet the two lovers find that they have missed it—“I never saw the sun! We will walk here/ To-morrow; thou shalt look on it with me.” However, there is no tomorrow. “That night the

youth and lady mingled lay/ In love and sleep—but when the morning came/ The lady found her lover dead and cold.”

The grief stricken woman lives out the rest of her life in a state of mourning—“Her eyes were black and lustreless and wan/ Her eyelashes were worn away with tears/ Her lips and cheeks were like things dead—so pale.” At the end a violin solo gently and warmly concludes the piece in the major key, conveying not despair but quiet resignation—“Whether the dead find, oh, not sleep! but rest.”

Selections from Cypresses are scored for string quartet (9 minutes).

In 1865, the 24-year-old Dvořák fell in love with a 16-yearold piano student. In an ardent outpouring, he composed a cycle of 18 love songs for voice and piano with texts selected from a volume of poetry titled Cypresses by the Moravian poet Gustav Pfleger-Moravský (1833–1875). Twenty-three years after that first flush, Dvořák selected 12 of the songs and transcribed them for string quartet, but without voice, and provided them with the new title Echo of Songs. Seventeen years after Dvořák’s death, these were published under the title Cypresses, an obvious link to the original poems by Pfleger-Moravský.

Each of the Cypresses features a solo melodic line faithfully rendered from the original vocal line and beautifully set within the four-part texture of the string quartet. The accompaniments feature rich, colorful textures using a range of string techniques, counterpoints, and rhythmic nuances. The composer exclaimed, “Just imagine a young man in love—that’s what they’re all about!”

Handel was born in Halle, Germany, and trained in the German music tradition. He spent three years in Italy where he learned the Italian art of vocal music and opera, and then sailed to England where he was in service to the royal family for 45 years. Handel had an extraordinary ability to musically depict human character, bringing to the aria a consummate range and subtlety of emotion and expression.

Ogni vento ch’al porto lo spinga “Whatever wind blows him to port” (from Agrippina, 1709). Agrippina delights in the thought that her son Nero will be the next emperor— “my one hope, my son reigns.”

Da tanti affanni oppressa “Oppressed by so many woes” (from Admeto, 1726). Antigona yearns for Admeto who is married to another—“Never shall you cease to grieve, till, wandering soul, you cease to live.”

Da tempeste il legno infranto “When the battered boat safely reaches harbor” (from Giulio Cesare, 1724). With this aria, Cleopatra joyfully sings that her beloved but beleaguered Caesar has returned to her.

Symphony No. 4 in B-Flat Major, Op. 60 is scored for one flute, pairs of oboes, clarinets, bassoons, horns, and trumpets, with timpani and strings (35 minutes).

During a visit to Silesia (now the Czech Republic) in 1806, Beethoven met with Count Franz von Oppersdorf. The Count’s orchestra had already performed Beethoven’s Symphony No. 2, and so he commissioned another from the famous composer. Beethoven was in the midst of writing his explosively dramatic fifth symphony, but he put it aside and turned to composing a symphony for the Count. Considering that Count Oppersdorf especially liked the more subtle classical style of the Symphony No. 2, Beethoven tips his hat to his patron in the creation of the more classically shaped Symphony No. 4.

Beethoven’s Symphony No. 4 is a lighthearted masterpiece full of mischievous musical jokes. Instead of an epic journey from darkness to light, as is so much of Beethoven’s music, this symphony is a beguiling work full of comedy and enchantment. Lindsay Kemp (BBC, 2014) describes this symphony as “taut with muscular strength, propelled with unstoppable momentum … it purrs with the mature assurance of Beethoven’s middle period compositions and, like so many of those, is among his most lovable and appealing creations.”

The first movement, Adagio—Allegro vivace (Slow— Fast and lively), begins with a slow, mysterious introduction, which is quickly dispelled with the appearance of a bubbling theme, some counterpoint, some beautiful lyrical sections, a stormy outburst, and then comes to a standstill as if all these contrasting ideas simply cannot be resolved. The second movement, Adagio (Slow, at ease), contains yearning melodies undergirded by a rhythmic motif like a heartbeat. The third movement, Scherzo. Allegro vivace (Fast, with life), is full of rhythmic games, sudden changes of mood, and unexpected turns. And the finale, Allegro ma non troppo (Fast, but not too much), is a cheery romp with the best jokes saved for last.

Caroline Shaw (b. 1982) Entr’acte is scored for string orchestra (12 minutes).

Caroline Shaw is a New York–based musician who appears in many different guises. In 2013 she became the youngest (age 30) winner of the Pulitzer Prize for Music. She is a GRAMMY-winning singer in the vocal ensemble Roomful of Teeth and a violinist with the American Contemporary Music Ensemble (ACME). She has performed with the Mark Morris Dance Group, and has appeared incognito as a backup singer and violinist on Saturday Night Live with Paul McCartney, on the Late Show with Dave Letterman, and on the Tonight Show. Shaw has been a Rice University Goliard Fellow (busking and fiddling in Sweden)

and a Yale Baroque Ensemble Fellow. In addition to maintaining a busy freelance career as a violinist and singer, she has written over 100 works for leading names in the arts industry including Yo-Yo Ma, Renée Fleming, Kanye West, Dolly Parton, the orchestras of Baltimore, Cincinnati, Los Angeles, New York, and Seattle, and others.

Caroline Shaw writes that “Entr’acte [meaning between acts] was written in 2011 after hearing the Brentano Quartet play Haydn’s Op. 77 No. 2. My piece is structured like a minuet and trio, riffing on that classical form but taking it a little further. I love the way some music suddenly takes you to the other side of Alice’s looking glass, in a kind of absurd, subtle, Technicolor transition.”

The Piano Concerto No. 23 in A Major, K. 488 is scored for solo piano, one flute, pairs of clarinets, bassoons, and horns, with strings (25 minutes).

In 1781 Mozart broke loose of Salzburg and his family, and moved to Vienna. As the capital of the Austrian Empire, Vienna was the economic, political, and cultural center of a domain that stretched from the Netherlands to Russia. Noble families from across Europe maintained second homes in Vienna, and concerts and entertainment flourished there. Mozart was at the height of his popularity in Vienna, in demand as a composer and celebrated as a pianist. Here he wrote 17 of his 27 piano concertos. The piano concerto, in Mozart’s hands, offered the chance to exploit dual protagonists—piano and orchestra—of comparable versatility and weight, and he became the master of articulating the various shades of alliance and rivalry that this relationship afforded.

In this concerto, Mozart omits trumpets and timpani and replaces oboes with clarinets, creating a work with an unusually warm and glowing atmosphere. The first movement, Allegro (Fast), is written in traditional sonata form with a double exposition: the thematic material is first presented by the orchestra and then restated by the soloist. The movement overall is graceful and serene, though with excursions into sunny confidence, smiling joy, and, briefly, disturbing gloom. The second movement, Adagio (At ease), presents some of Mozart’s most heartbreaking music. With profoundly expressive wind writing and the interplay between the soloist and orchestra we revel in the intimacy of chamber music more than the grandeur of orchestral music. The final movement, Allegro assai (Very fast), is joyful and full of mercurial wit and humor. Themes are tossed back and forth between the soloist and orchestra as they chase each other through unexpected key changes until we’re finally back in A major and the work races to a playful conclusion.

Quartet in C Minor, Op. 18, No. 4 (25 minutes)

Beethoven’s sixteen string quartets round off in a burst of glory, the great tradition already carried to miraculous heights by Haydn and Mozart. Between these three composers are more than one hundred works which represent some of the most sophisticated, daring, intellectual, and intimate music ever written. There is much that can be expressed in the private world of the string quartet that is not suited for the more public forms of the symphony or opera.

Beethoven’s six Op. 18 quartets were written between 1798 and 1800, inspired by a commission from Prince Franz Joseph Maximilian von Lobkowitz. The prince was called “the greatest fool for music one can imagine,” and his palace was nicknamed “the true residence and academy of music.” It was always open to musicians and frequently one would discover several rehearsals going on at the same time in different rooms throughout the palace.

The first movement of the Quartet Op. 18, No. 4, Allegro ma non tanto (Fast, but not too much), dives right into early Romanticism and is filled with drama and urgency. The second movement, Andante scherzoso quasi allegretto (Amusing and flowing, somewhat fast), is poised and delicate with overlapping entries, gentle dissonances, use of repetition for effect, and sonorously choral-like passages. The Menuetto Allegretto (A little fast) appears traditional in structure, but Beethoven fools us by discarding expected repeated sections, suddenly faster tempos, and using syncopation that keeps us slightly off-balance throughout. The final movement, Allegro. Prestissimo (As fast as possible), brings us back to the dramatic storm, but is contrasted with surprising interludes. The last time the theme returns, it’s at breakneck speed galloping to a dramatic end only to fall into histrionics at all the hubbub.

Fritz Kreisler, the famous violinist and composer of exquisite miniatures for violin and piano, also wrote a single string quartet and was himself a regular string quartet player. The Quartet in A Minor was completed in 1922, after the classical music world witnessed a decade of tumultuous musical trends, including the shocking works of Schoenberg and Stravinsky. This quartet is considered his most ambitious creation, a lyrical but harmonically ripe

work. The composer declared, “This is my confession or avowal to Vienna, what that city meant to me, and my great love of the Viennese spirit.”

The opening movement, Fantasie Allegro moderato (A fantasy, moderately fast), strikes a note of tragic drama with the opening cello solo, and remains eerie and haunted throughout. The following Scherzo Allegro vivo con spirito (Jokingly, fast, lively with spirit) dances along, bursting with energy, but also bends toward waywardness. The slow movement, Introduction and Romance. Andante con moto (Flowing, with motion), is poignant and yearning. The finale, Allegro molto moderato (Fast, but moderate), has a rhythmic gaiety to it, like an updated version of a Viennese dance tune. Slowly the music builds to a dramatic climax that is capped by the restatement of the tragic utterance of the cello solo from the beginning of the first movement. The music ends quietly, perhaps eulogizing the brilliant Vienna of the closing decades of the Hapsburg Empire that was destroyed by the First World War.

Johannes Brahms (1833–1897)

Quartet No. 3 in B-Flat Major, Op. 67 (35 minutes)

Brahms began writing string quartets as a teenager, but because of his rigorous and relentless selfcriticism, he did not publish his first quartet until he was 40. He reported to a friend, “It is not hard to compose, but it is fabulously hard to leave the superfluous notes under the table.” In 1875 he wrote his third (and last) string quartet, Op. 67. It was written quickly, between August and November of 1875, and was given a private hearing by his longtime friend, the great violinist Joseph Joachim and his string quartet in the home of Clara Schumann on May 23, 1876.

The opening Vivace (Lively) is marked by bucolic hunting calls and polka-like snippets. It is fast-paced, merry, and dance-like. The serenely lyrical second movement, Andante (Flowing), is one of Brahms’s most beautiful instrumental songs, a peaceful melody occasionally interrupted by dramatic outbursts. The subsequent Agitato Allegretto non troppo (Agitated, but not too fast) is a darkly driven waltz, with the viola prominently displayed against its muted companions. Brahms remarked that this was “the tenderest and most impassioned I have ever written.” The last movement, Poco allegretto (A little fast), presents a simple folk-song melody, which is followed by seven variations of increasing complexity. Finally, the hunting horn calls the players together and the quartet ends joyously.

Concert Support | WESTAF (the Western States Arts Federation)

Thank you to the New Mexico Museum of Art for their support of Pro Musica’s String Works Series.

Discography:

Exclusive

New York, NY

Though commonly referred to as Bach’s Sonatas and Partitas for Solo Violin, the composer himself titled them Sei Solo a Violino senza Basso accompagnato (Six Solos for Violin without Bass accompaniment). Profound in spirit and monumental in scope, these works are considered the pinnacle of writing for the violin and demand a corresponding degree of skill from the performer. The beautiful autograph of this music, which dates from 1720, remained in the possession of the Bach family until the middle of the 19th century. In 1890 the manuscript resurfaced and passed through the hands of Johannes Brahms before it came to the Berlin Imperial Library in 1917.

This set consists of three sonatas with Italian-style movements alternating with three partitas with French-influenced dance movements. The sonatas follow the established Italian four-movement model: a lyrical introductory movement, followed by an academic fugue, then a slow meditative movement, and concluding with a finale of rapid passagework. The partitas are French suites or sequences of dances. The term partita may also denote a set of variations, and Bach indeed includes those too. Most of these dances have their origins in Renaissance folk music, which was then adapted and refined for noble ballrooms. By Bach’s time, the dances had become highly stylized pieces and only distantly reflected their origins.

Partita No. 3 in E Major, BWV 1006 (18 minutes) opens with a brilliant Preludio (Prelude) followed by the Loure (from the instrument of the same name, a small bagpipe originating in Normandy), a Gavotte en rondeau (a dance involving kissing or the presentation of flowers), two contrasting Menuets, a lively Bourrée (clog dance), and concluding with a happy Gigue (jig).

Sonata No. 1 in G Minor, BWV 1001 (15 minutes) opens with a majestic and richly ornamented Adagio (Slow, at ease) followed by a four-voice fugue. After a swaying, quiet Siciliano, the sonata ends with a whirling moto perpetuo (Presto, fast).

Partita No. 2 in D Minor, BWV 1004 (30 minutes) Bach presents us here with the most common sequence of dances. This work opens with the Allemande (from the French word for “German”) in a moderate quadruple meter dance where couples form a line, and always holding hands, parade back and forth the length of the ballroom, walking three steps, then balancing on one foot. Then follows the Corrente (from the Italian word “running”), a fast dance in triple meter, also for couples, and performed with small, back-and-forth, springing steps. The Sarabande is initially from the New World Spanish colonies, and is

a slow, serious processional dance, in triple meter, with emphasis on the second beat. The standard dance sequence ends with a Giga (from the British Isles, “jig”), a lively dance with a jaunty up-beat and swinging triplets.

However, Bach does not stop here but concludes this partita with an astonishing Ciaconna that exceeds in length all the other four movements combined. Like the sarabande, the ciaccona (Italian) or chaconne (French) originated in the Spanish colonies, and was a slow, intense dance. Bach’s monumental conception contains a set of 31 variations over a fourmeasure bass line (Pachelbel’s Canon is perhaps the most famous example of this form). “From the grave majesty of the beginning to the fast notes which rush up and down like the very demons; from the tremulous arpeggios that hang almost motionless, like veiling clouds above a dark ravine to the devotional beauty of the D major section where the evening sun sets in a peaceful valley: the spirit of the master urges the instrument to incredible utterances. At the end of the D major section it sounds like an organ and sometimes a whole band of violins seem to be playing. This Ciaccona is a triumph of spirit over matter such as even Bach never repeated in a more brilliant manner.”—Philippe Spitta, 1873, from his biography J.S. Bach.

Sonata No. 2 in A Minor, BWV 1003 (24 minutes) opens with a heavily ornamented, rhetorical Grave (Serious), followed by a fugue of great diversity, an Andante (Flowing) reminiscent of the well-known Air on the G String, and concluding with a restlessly energetic Allegro (Fast).

Partita No. 1 in B Minor, BWV 1002 (20 minutes) consists of the four most common dances, each followed by a variation or “double.” The irregular and complex rhythms of the opening Allemanda are followed by a Corrente and a Sarabande. This Partita concludes with a darkly energetic movement curiously marked Tempo di Borea. It is most often translated as Tempo di Bourrée, suggesting the commoners’ clog dance that was refined at the French court. But perhaps it really was a reference to the cold winds (borea) that rush into northern Europe during the winter?

Sonata No. 3 in C Major, BWV 1005 (23 minutes) opens with a somber Adagio (Slowly, with ease) and serves as a preface for the magnificent fugue that follows, based on a quotation from the Pentecost antiphon Veni Sancte Spiritus (Come Holy Ghost). After a touching Largo (Broad), the sonata ends with a dizzying moto perpetuo (Allegro assai, very fast).

is scored for a solo violin, flute, and harpsichord, with string ensemble (20 minutes).

Bach’s six Brandenburg Concertos are recognized as supreme examples of Baroque instrumental music—“a kaleidoscopic treasure.” These concertos survive in Bach’s handwriting and are humbly titled Concerts avec plusieurs instruments (Concertos with several instruments). The exquisite manuscript was rediscovered in the Berlin Imperial Library during the 19th century and published in 1850. The popular name Brandenburg Concertos was bestowed in 1873 by Philipp Spitta from his biography J.S. Bach. It can only be surmised why Bach wrote these pieces, and volumes have been devoted to possible scenarios. Regardless of their origins, the pleasures of these gems have captivated artists and audiences since their rediscovery.

Bach bases his six Brandenburg Concertos on the concerto grosso form, one of the most popular instrumental forms of the Baroque period. This form features a group of solo instruments (concertino) supported by and contrasted against a larger group of instruments (ripieno). (For more information about Bach’s Brandenburg Concertos see page 37).

The Brandenburg Concerto No. 5 opens with the strings playing a robust, ascending figure. The solo flute enters with a contrasting lyrical sighing gesture, with the solo violin joining in this gentle conversation. The harpsichord kindly creates a filigree background throughout, but becomes increasingly impatient, and then finally bursts into an extended solo cadenza, fully constructed by Bach, and considered one of the most astonishing cadenzas ever written. In the second movement, Affettuoso (With feeling), only the soloists play, with the violin and flute frequently paired and gently contrasting against the harpsichord, creating a touchingly intimate conversation. Bach begins the third movement, Allegro (Fast), simply with the soloists, and gradually brings in all the other instruments, ultimately creating a dizzying web of melodies.

Coffee Cantata, BWV 211 is scored for soprano, tenor and bass voice, with flute, string ensemble, and harpsichord (30 minutes).

Starting in the early 1600s, the university students in Leipzig, Germany, were convening at collegia musica, or musical clubs, known for their rowdy crowds and exuberant conversation, but with the expressed intent to play music together. Bach, upon his arrival in Leipzig in 1723, took over one such collegia based at Zimmermann’s Coffeehouse where Herr Zimmermann hosted music on Friday evenings during the winter and in the garden on Wednesday afternoons during the summer. Bach’s concerts there became so well known that not only university students but visiting musicians and touring virtuosos would eagerly drop in and contribute to the music-making.

In addition to music and regular pub fare, the introduction of the new and exotic beverage—coffee—offered further stimulation. However, coffee was not initially considered a benign substance and was even condemned by some. It was described as a “decoction of the Devil” and supposedly tasted like the “syrrop of soot” or the “essence of old shoes.” Bach was clearly aware of coffee’s mixed reputation, and in 1735, for one of his coffeehouse concerts, he wrote a short comic cantata (a work for voices and instruments, usually unstaged and without props and costumes), now commonly referred to as his Coffee Cantata

In the Coffee Cantata and in the eyes of Bach’s fictional overprotective father Schlendrian, coffee was no beverage for a girl from a good family, and coffeehouses were no places for respectable women. In 18th-century Germany, women were indeed discouraged from loitering in coffee shops, but they nevertheless persisted and organized all-female Kaffeekranzchen (coffee circles) that provided a place for them to congregate, drink coffee, play cards, and converse. The chorus at the end of this cantata hints that Lieschen had probably picked up her coffee habit from her female relatives who frequented these coffee houses: “Just as cats do not give up mousing, mother adores her coffee and grandmother also drinks it, so who can blame the daughter?”

Schlendrian pulls out all the stops to make his daughter Lieschen give up her coffee habit. He cajoles, he threatens—no more jewelry, no new dresses. Lieschen remains unfazed and jousts amicably with her father. But then he ups the ante—he will not approve of any husband for her, unless she gives up coffee. However, the vibrantly confident Lieschen finds a way to have it all.

“Mere words cannot express the general delight of this work of Bach; one must hear it, following the libretto, to appreciate all its charms, and then lament that Bach never produced a full comic opera for the ages. This is as close as he gets.”—The Bach Choir of Bethlehem

Brandenburg

Santa

Brandenburg

Tatum

in G

in G Major,

Jennifer

Brandenburg Concerto No. 6 in B-Flat Major, BWV 1051

ma non tanto—Allegro David Felberg and Laura Chang,

Organ

in D Minor, BWV 1052

David Solem,

Thank

Musica’s

From 1717 to 1723, Bach worked for Prince Leopold of Anhalt-Cöthen and produced for that court some of his most imaginative instrumental music, including the solo violin partitas and sonatas, the solo cello suites, and the orchestral suites. We have no evidence that Bach was unhappy in this courtly position, but we do know that in 1720 he applied for another position in Hamburg (he was rejected). And then in 1721 Bach sent an extraordinarily beautiful set of six concertos to Christian Ludwig, the Margrave of Brandenburg. Such gifts were usually presented as solicitations for possible employment. However, Bach was not offered employment there and he ultimately moved on to Leipzig. The manuscripts for these concertos were rediscovered in 1849 in the Prussian Royal Library, and found to be in pristine condition, suggesting that they had never been performed. (For more information about Bach’s Brandenburg Concertos, see page 35).

The Brandenburg Concerto No. 3 is scored for three violins, three violas, three cellos, plus harpsichord and bass (12 minutes). Throughout the two fast movements, Bach combines and recombines the three trios of instruments, having them echo and contrast with each other. The inner movement, Adagio (At ease), is a single measure connecting the two fast movements. It is conjectured that Bach’s intention was an opportunity for the harpsichordist or first violinist to provide an improvisation.

The Brandenburg Concerto No. 4 (15 minutes) is scored for a trio of solo violin and two flutes, supported by the ripieno (string ensemble and harpsichord). Within the solo group, the violin is the most virtuosic participant, investing the music with the texture of a solo concerto. The flutes most often work in tandem and can be considered a solo unit rather than separate soloists. The three solo treble instruments create a brilliant sonority.

The Brandenburg Concerto No. 6 is uniquely scored for two solo violas, with cello, bass, and harpsichord (12 minutes). The unusual sonority created by the exclusive use of middle and low register strings is dark and mellifluous. This concerto is a virtuoso showpiece for the viola players. Full of astonishing contrapuntal writing in the first movement, followed by a poignant Adagio ma non troppo (Slow, but not too much), the work concludes with buoyant energy and optimism.

The Organ Concerto in D Minor, BWV 1052 is scored for solo keyboard (originally organ or harpsichord) and strings (22 minutes).

From 1708 to 1717, Bach was music director at the royal court in Weimar. His patron Prince Johann Ernst, an avid and skillful musician himself, maintained a music library with much contemporary music, including the “new” concertos of the Italian violinist and composer Antonio Vivaldi (1678–1741). Though Bach and Vivaldi never met nor corresponded, the Italian composer’s influence is recognizable in the instrumental works of Bach. Indeed, Bach’s two oldest sons remarked that their father learned the Italian method by transcribing Vivaldi’s violin concertos for the keyboard—“Vivaldi’s concertos served our father as a guide. He studied the chain of ideas, their relation to each other, the variation of the modulations, and many other particulars.”

From Vivaldi, Bach learned how to organize musical material through the use of repeated orchestral sections (ritornellos) and the alternation of solo and tutti (from the Italian, “together”). In the fast movements, Bach utilized Vivaldi’s preference for short musical motifs that allowed greater opportunities for exploration and elaboration. In the slow movements, he adopted Vivaldi’s concept of singing melodies (arias) that were simply supported by repeated bass figures. And from the “sinfonia” that opened 18th-century Italian operas, Bach adopted the balanced sequence of movements: fast—slow—fast.

Bach’s reputation was initially established because of his prodigious skills as an organist, performing and improvising upon the pipe organs in churches. Later, he gravitated to the harpsichord, a more secular instrument that was readily found at courts and upper class households. Bach frequently recycled his music, rearranging older works for newer environments. For his D Minor Keyboard Concerto, the original version, now lost, appears to have been for violin. Bach also reworked the first two movements for inclusion in his Cantata 146 and the last movement for Cantata 188. Bach was a busy man, and recycling his music was just a fact of life for him, rearranging his works to fit a particular situation, whether music for church services, or court events, or evenings at Zimmermann’s Coffeehouse.

The D Minor Concerto, Bach’s best known keyboard concerto, presents an earnest and dark-hued world. The work opens with a powerful, jagged theme that opens up to virtuosic keyboard writing culminating in a dramatic cadenza leading back to the opening material that will now end the movement. A more introspective Adagio (Slow, at ease) follows, structured on a repeating bass line (basso ostinato or ground bass). Upon these stately utterances, the soloist plays a poignant and lyrical cantilena. The third movement Allegro (Fast) returns to the forceful driving rhythms presented in the first movement, culminating in a brief cadenza that leads to the closing ritornello.

Quartet in G Minor, Op. 20, No. 3 (25 minutes)

Haydn wrote 68 string quartets over a 40-year period, but it was his Op. 20 (1772) that earned him the sobriquet “the father of the string quartet.” With this set, Haydn developed the string quartet form that was to define the medium for the next 200 years. With these quartets we have equality of voices— like “listening to four rational people conversing among themselves” (Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, 1749–1832). These quartets also shifted from being mere entertainments to conveyors of emotional complexity, standardized the sequence of movements, and adapted 18th-century conventions for the string quartet including sonata form, the minuet-trio complex, variation form, rondo, and fugue.

The first movement of this quartet, Allegro con spirito (Fast, with spirit), presents three characters. The first one is distinguished by jagged, combative leaps. The second one involves unpredictable silences. And the third one presents hushed declarations by the whole quartet in unison, evoking a Greek chorus commenting on the action. The Minuetto. Allegretto (a little fast) is a somber work with phrases of irregular length, creating a more rhetorical and less dance-like atmosphere. The third movement, Poco Adagio (a little slow), presents two ideas, a melody played by the first violin, and an intricate counter line first played in the cello. The finale is a fiery Allegro di molto (Very fast) with strong Romani undertones and an atmosphere of dark-hued merrymaking.

Quartet No. 7 in F-Sharp Minor, Op. 108 (13 minutes)

As a child Shostakovich witnessed World War I. As a teenager he lived through the Russian Revolution. As a young man he survived Stalin’s purges. As a mature artist he saw the horrors of World War II and the Nazi blockade. Finally, at the end of his life, he experienced the thawing of Soviet society. Political interference, as well as social and cultural oppression, blighted his entire career.

Shostakovich completed his Quartet No. 7 in March 1960. It is the shortest of his fifteen string quartets and is dedicated “In Memoriam” to his young wife Nina, who had died unexpectedly. This true-life drama is reflected in the composer’s choice of key for the work, F-sharp minor, which is traditionally associated with pain and suffering, loss and bereavement.

The first movement, Allegro (Fast), simmers with nervous energy. It is alternately harsh and biting, animated with impish humor, or fleetingly morbid. The movement fades away into the dream-like and seductive second movement, Lento (Slow). Its lyrical phrases are initially soothing and soporific, however once we slip into deep sleep, we find ourselves in a disturbing dreamscape. Floating back into consciousness, we are rested but poorly

prepared for the shock which now awaits us. With the commencement of the third movement, Allegro (Fast), we are suddenly confronted with “the loud yapping of a dog, then an accusatory, vitriolic canon begins waves of ferocious assaults” (Stephen Harris, www.quartets.de). This nightmare is abruptly terminated and becomes full of the eerie impish humor of the first movement. The music loses energy, collapses, and dies away.

Britten is regarded as one of the greatest 20th century composers. His musical talents appeared early in his life, and before the age of 18 he had already written over 100 works. Britten’s fame is assured through his vocal and stage works, and a compelling variety of chamber music, including three string quartets.

The Three Divertimenti for string quartet were written in 1933 when Britten was in his early twenties. They are a set of character pieces meant as entertainment without necessarily any serious import or larger formal considerations as might be implied by the traditional multi-movement string quartet form. The bristling rhythms and colorful harmonies of the first movement, March Allegro maestoso (Fast, dignified), places the music in the 20th century, but as with most of Britten’s compositions, the music is tonal and easily appealing. Nonetheless, Britten slips in suggestions of Stravinsky and Bartók, which can still sound modern to our ears. The second movement, Waltz Allegretto (A little fast), is more tame with traditional chamber music–type conversations, and with a distinct whiff of the pastoral English countryside. The last movement, Burlesque Presto (Very fast), reprises the vibrancy of 20th-century rhythms, techniques and sonorities in a masterwork of color and dynamic contrast.

Music critic Patrick Rucker wrote in The Washington Post (2018) that “The Danish String Quartet played a concert Monday night that eloquently demonstrated the power of folk music. Its members could have emerged from Central Casting for a remake of ‘The Vikings.’ But make no mistake, each is a master musician. Together, they play with a cohesion, finesse and precision second to none. Having built a solid reputation in the standard string quartet repertory, recently they’ve turned their attention to Nordic folk music. … There were arrangements of music collected in the 18th century by an itinerant Swedish fiddler; a piece that may have been sung a thousand years ago by Norwegians on the Shetland Islands; and traditional Danish tunes from particular corners of that tiny nation. Every last note, whether evoking open fields, dense forests, mighty fjords, the deep sea, or the flight of birds, was played with a freshness, immediacy and love that gripped the heart and wouldn’t let go.”

Danza Ritual del Fuego (Ritual Fire Dance) is scored for two flutes, one oboe, two clarinets, one bassoon, two horns, two trumpets, timpani, piano, and strings (5 minutes).

Originally from Cádiz, Spain, but living most of his life in Madrid, Manuel de Falla wrote music suffused with the distinctive flavor of his Spanish heritage. However, he admonished that “You must go really deep so as not to make any caricature. You must go to the natural living sources, study the sounds, the rhythms, use their essence, not their externals.”

The Danza Ritual del Fuego is a movement from de Falla’s ballet El amor brujo (Love, the Magician, 1914). The story is told of the Romani Candela who is possessed by the ghost of her faithless former husband. To exorcize the demon, all the Romani convene at midnight and form a circle around the campfire. Candela then performs a frenzied dance, luring the ghost to dance with her. As they whirl around faster and faster, the ghost is drawn into the flames where it is finally extinguished.

Earth for Solo Tenor and Chamber Orchestra is scored for pairs of flutes, oboes, clarinets, bassoons, and horns, with one trumpet, timpani, percussion, piano, harp, and strings (26 minutes).

The composer Aaron Jay Kernis has won the Pulitzer Prize (1998, String Quartet No. 2) and a GRAMMY Award (2019, Violin Concerto). He teaches music composition at the Yale School of Music.

Kernis describes the two movements as a story (Seasons) and a song (Farewell). The first, Seasons, is about a farmer and the land he lives on, where he works and raises his family. The text is by the poet, farmer, and researcher Kai Hoffman-Krull, who lives and farms near Seattle. The second movement, Farewell, is based on an excerpt of William Wordsworth’s poem Tinturn Abbey (1798). Kernis began the work as a homage to Gustav Mahler’s song cycle Das Lied von der Erde (The Song of the Earth), and was inspired by the last movement titled Der Abschied (The Farewell), a rhapsodic, pensive, and deeply spiritual farewell to earthly life.

This work is additionally inspired by the artistry of tenor Nicholas Phan, for whom it was written, and by the venue Tippet Rise Art Center, founded by Peter and Cathy Halstead, located among hundreds of acres of protected and ruggedly beautiful land in Montana. Earth was first written for a chamber ensemble of seven players plus tenor. Santa Fe Pro Musica and the River Oaks Chamber Orchestra (Houston) are the cocommissioners (2021) of the expanded orchestra version, which was created especially for them.

Symphony No. 2 in D Major is scored for two oboes, two horns, and strings (10 minutes).

Of French and Caribbean heritage, Joseph Bologne was the son of Georges de Bologne Saint-Georges, a wealthy, married plantation owner, and Nanon, an enslaved young African woman. When Joseph was seven years old, his father took him to France, where he was educated at a boarding school. The youth was recognized and applauded as a superlative fencer, but little is known about his musical education, though the results indicate that it was thorough and enthusiastically embraced by the student. Ultimately, Bologne wrote 14 violin concertos as showpieces for himself, plus chamber music, symphonies, and operas. We see that Joseph Bologne appeared in 1769 as a violinist in Le Concert des Amateurs. We know he became its concertmaster four years later, and then its director. This ensemble was described as “performing with great precision and delicate nuances and became the best orchestra for symphonies in Paris, and perhaps in all of Europe.” These performances were so acclaimed that Queen Marie Antoinette was known to make unannounced appearances.

The Symphony No. 2 has a dual life, as a symphony and as the overture to Bologne’s most successful comic opera L’Amant Anonyme (The Anonymous Lover). The work evokes the style of early Mozart with a distinctly French twist.

Symphony No. 35 in D Major, K. 385, “Haffner” is scored for pairs of flutes, oboes, clarinets, bassoons, horns, and trumpets, with timpani and strings (20 minutes).

Mozart’s festive Symphony No. 35, K. 385 “Haffner” originated from a request in July 1782 for a serenade celebrating the ennoblement of the son of Salzburg’s Burgomeister Sigmund Haffner. Six months later, Mozart needed a new symphony for one of the Academies (concerts given during Lent when the theaters were closed), so he revised the Haffner Serenade and transformed it from a party piece into a four-movement symphony. He deleted several movements and added flutes and clarinets to give it a richer palette. Many symphonies written during the 1780s commenced with a bold gesture that acted as a “noise killer,” a wake-up call to the audience that the concert was starting. Mozart’s Haffner Symphony is no exception. The first movement, Allegro con spirito (Fast, with spirit), begins with a striking upward leap, abruptly falling into a dramatic silence. It is a brilliantly effective gesture opening a joyous movement that Mozart instructed “must be played with great fire.” A pastoral slow movement, Andante (Flowing), follows, and then a minuet with an Austrian Ländler-like quality. The symphony concludes with a sizzling finale (Presto) based upon a Turkish theme from his opera The Abduction from the Seraglio, and one that Mozart directed should be played as fast as possible.

Mason Bates is a GRAMMY Award–winning American composer and DJ of electronic dance music. He is the first composer-in-residence at the Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts, and has also held residencies with the symphonies of Chicago, San Francisco, and Pittsburgh. Bates attended the Columbia-Juilliard Program and earned a Bachelor of Arts in English Literature and Master of Music in Music Composition. In 2001, Bates relocated to the San Francisco Bay area and studied at the Center for New Music and Audio Technologies at the University of California, Berkeley, and graduated in 2008 with a Ph.D. in Composition. He worked during that time as a DJ and techno artist in clubs and lounges of San Francisco.

His first opera, The (R)evolution of Steve Jobs, was premiered and recorded in 2017 by the Santa Fe Opera, and won the 2019 GRAMMY for Best Opera Recording. He has also received many other prestigious awards and recognitions, including Musical America’s Composer of the Year (2018), Guggenheim Fellowship (2008), First Prize at the Van Cliburn American Composer Invitational (2008), American Academy in Berlin Prize (2005), Rome Prize (2004), and prizes and fellowships from the American Academy of Arts and Letters, Tanglewood Music Center, and Aspen Music Festival.

The Suite for String Quartet was co-commissioned by the Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts and Bravo! Vail Music Festival, and premiered in Vail in the summer of 2022.

1946 while a graduate student at the Curtis Institute of Music. The first movement, Allegro (Fast), presents three contracting ideas, the first one of rhythmic vitality, the second lyrical sadness, and the third features a dramatic, almost angry theme. The second movement, Molto adagio (Very slow), is an elegy dedicated to his grandmother upon her death. It is a lush, rhapsodic and optimistic work colored with fleeting shadows of sadness. The last movement, Allegro con fuoco (Fast, with fire), is strongly defiant, sometimes tempered with gentleness or resignation, but more often fighting, with fist raised and jubilant.

Antonín Dvořák (1841–1904)Quartet No. 10 in E-Flat Major, Op. 51, “Slavonic Quartet” (33 minutes)

Dvořák came from the Czech Republic, then part of the Austrian Empire. He was an advocate of his country’s folk music and infused many of his compositions with the spirit of his culture. He was also influenced by the Viennese classical tradition stretching from Mozart, Haydn, and Beethoven to his friend Johannes Brahms. Dvořák’s 14 string quartets are regarded as one of the finest sets of 19th-century string quartets.

In 1878, Dvořák published his Slavonic Dances, Op. 46, a set of 16 dances for orchestra. They were wildly successful and established for him an international reputation, including a commission for a new string quartet “in the Slavic style.” Dvořák responded by composing his tenth string quartet, Op. 51, published in 1879 and subsequently known by its nickname “Slavonic.” This quartet has been described as the perfect fusion of classical style and the Slavic folk spirit.

George Walker graduated from high school at the age of 14, and attended Oberlin College where he studied piano and organ, graduating at 18 with highest honors. He furthered his education at the Curtis Institute of Music, graduating in 1945 as the first Black graduate of this renowned music school. He achieved many other “firsts” in the classical music industry, including the first Black soloist with the Philadelphia Orchestra (1945), the first Black doctoral graduate of the Eastman School of Music (1955), and the first Black composer to be awarded a Pulitzer Prize in Music (Lilacs for voice and orchestra, 1996). He taught at Smith College, University of Colorado Boulder, Peabody Institute of Johns Hopkins University, and Rutgers (1969–92, Chairman of the Music Department). Walker’s awards include two Guggenheim and two Rockefeller Fellowships, a Fromm Foundation commission, two Koussevitzky Awards, an American Academy of Arts and Letters Award, and many others.

George Walker composed his String Quartet No. 1 in

The quartet opens with a warmly lyrical Allegro ma non troppo (Fast, but not too much). The flowing quality of the music is punctuated by a rhythmic lilt suggestive of the polka, originally a Bohemian dance. The development section features Dvořák’s characteristic flickering between the major and minor modes, a trait recalling the exotic flavor of Eastern European folk music. The development section shifts briefly into something more reverent in the manner of a hymn that Dvořák achieves by slowing the main theme to half its speed. The second movement, Dumka, suggests a style of folk ballad that begins as a slow lament with contrasting fast sections of celebratory exuberance. Dvořák creates a heartfelt romance in the third movement, Romanza Andante con moto (Flowing with motion). The rollicking Finale Allegro assai (Very fast) is based on the skačna, a Bohemian fiddle tune akin to an Irish reel. A vivacious dance animates the movement full of contrasting rhythms, tempos, and moods including a wonderful bluster of classical counterpoint, constantly shifting textures, an infectiously rustic folk character, a unique blend of high art and folk music.

George Walker (1922–2018)

String Quartet No. 1, “Lyric” (24 minutes)

Jennifer Higdon (b. 1962) Selections from Dance Card are scored for string orchestra (10 minutes). In 2010, Jennifer Higdon received the Pulitzer Prize in music for her Violin Concerto and a GRAMMY Award for a recording of her Percussion Concerto. Her opera Cold Mountain, based on the best-selling novel of the same name by Charles Frazier, was co-commissioned and premiered by the Santa Fe Opera in 2015. Higdon is currently Chair of Composition at the Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia. Higdon writes that “Dance Card is a celebration of the joy, lyricism, and passion of a group of strings playing together! This piece is made up of five movements, each of which is designed so that it can also be played as a separate work. From a string fanfare, through gentle serenades, and actual wild dances, the musicians get a chance to highlight their soloistic and ensemble playing. This work reflects the deep commitment that string players bring to their music-making, not only in the many years of learning to play their instruments, but also in the dedication manifested in gorgeous music-making as an ensemble. When we attend as audience members, we in effect, fill our dance card with that shared experience.”

Xavier Dubois Foley (b. 1995) Concerto for Double Bass and String Orchestra (world premiere). Raised in Marietta, Georgia, Xavier Foley thought he had two choices in life: either play football or become a rapper. At 11 years old, Xavier dropped all those stereotypes and picked up a double bass. “I just liked how it could be used to play jazz, classical, and rock and anything in between.” After high school he was accepted into the prestigious Curtis Institute of Music. Now, at the age of 27, Foley has already received many accolades, including winner of the Avery Fisher Career Grant, Young Concert Artists International Auditions, Astral National Auditions, Sphinx Competition, and the International Bass Society Competition. He has performed with the symphonies of Atlanta, Nashville, Victoria, the orchestras of Philadelphia and Brevard, and at the Marlboro Music Festival (Vermont), Tippet Rise Music Festival (Montana), Bridgehampton and Skaneateles Festivals (New York), New Asia Chamber Music Society (Philadelphia), South Mountain Concerts (Massachusetts), Wolf Trap (Virginia), and the Jupiter Chamber Players (New York).

Osvaldo Golijov (b. 1960) Last Round is scored for string orchestra (14 minutes). Golijov is from a Jewish family that immigrated from Romania to Argentina. He grew up listening to classical music, Jewish liturgical and klezmer music, and the tango music of Astor Piazzolla. He has received many awards and honors including a Guggenheim Fellowship (1995), MacArthur Fellowship (2003), Musical America Composer of the Year (2006), a 2007 GRAMMY Award for Best Opera Recording (Ainadamar), and a 2021 GRAMMY Award for Best Classical Contemporary Composition (Falling Out of Time). He has been composer-inresidence with the Los Angeles Philharmonic, the Chicago Symphony, and the Ravinia, Spoleto, Mostly Mozart, and Ojai Festivals.

Golijov writes, “I composed Last Round in 1996 … from a sketch I had written in 1991 upon hearing the news of Astor Piazzolla’s stroke. The title is borrowed from a short story on boxing by Julio Cortázar, the metaphor for an imaginary chance for Piazzolla’s spirit to fight one more time (he used to get into fistfights throughout his life). The piece is conceived as an idealized bandoneón [similar to a concertina, with “its moaning wheeze, seductive and sarcastic”]. The first movement represents the act of a violent compression of the instrument and the second, a final, seemingly endless opening sigh. But Last Round is also a sublimated tango dance. … The bows fly in the air as inverted legs in crisscrossed choreography, always attracting and repelling each other, always in danger of clashing, always avoiding it with the immutability that can only be acquired by transforming hot passion into pure pattern.”

Antonín Dvořák (1841–1904) Serenade in E Major for Strings, Op. 22 (30 minutes).

With origins in the Medieval period, the serenade was a song sung by a suitor under the window of his chosen lady. By the late 18th century, the serenade had become an instrumental work, usually of a light and romantic nature. Dvořák wrote his Serenade for Strings during a two-week period in May, 1875. The genial tone of this work could be attributed to the composer’s happy circumstances at this time—to his young marriage, the birth of his first son, and the growing recognition of his talent. The Serenade’s expressive harmonies, unpretentious counterpoint, and skilled use of the string orchestra (Dvořák’s experience as an orchestral violist served him well) all reveal excellent musical craftsmanship. His musical style is generally classical in its approach, owing much to Johannes Brahms, whom he admired, but also to the rich colors and exotic rhythms of the folk music of his Czech homeland. “The mellow opening sets the tone for the entire piece, which unfolds in five concise movements. The pace picks up gradually as the waltzing second movement leads to the dashing third movement. Then, Dvořák turns inward. Even though the Larghetto’s main melody aims downward, it never sounds downcast. Instead, its depth enhances the music’s richness and soul. The finale unleashes the bohemian excitement that Dvořák is so well known for, but offers parting glances of the Larghetto’s lyricism and the opening’s serenity before the last burst of rowdiness.”—Steven Brown (Houston Symphony, 2015).

GRAUPNER

447

TELEMANN

1:364

Concert Sponsor | M. Carlota Baca, in honor of Stephen Redfield

TELEMANN

Thank you to First Presbyterian Church for their support of Pro Musica’s Baroque Holy Week concerts.

This concert features music by the composers Telemann and Graupner. Most of us are acquainted with Telemann, but less so, or not at all, with Christoph Graupner. But consider in 1722 when the city of Leipzig interviewed candidates for music director, Telemann was first on their list and Graupner was second. After both musicians declined the position, the city offered it to their third candidate, J.S. Bach. Today’s performance will reveal why Telemann and Graupner were so highly esteemed during their day.

On this program are two cantatas, from the Italian word cantare, “to sing.” These are multi-movement, narrative forms of music for voice with instrumental accompaniment. During the Baroque period (1600–1750) cantatas were the heart of Lutheran church services, and Germany was the motherland of Lutheranism. Based upon scripture readings, cantatas include recitatives that describe the action and arias that dwell on the emotional impact of the action.

Graupner received musical instruction on the harpsichord and organ, and completed his musical studies at St. Thomas School in Leipzig (where Bach would later become headmaster). In 1709, Graupner was granted a position at the court of HesseDarmstadt, where he ultimately composed more than 2000 works. For over 250 years, his music has remained intact in the court library, but inaccessible to the public. Since the early 20th century, Graupner’s music has been undergoing a slow process of rediscovery through research, publication, and recording.

Telemann was adept with all the musical styles across Europe, notably the dance traditions of France, concerto forms from Italy, folk music from Poland, in addition to the contrapuntal style from his native Germany. His effortless ability enabled him to please all musical tastes, and he was acclaimed the most popular composer in Germany. In 1721, Telemann was appointed music director at the largest church in Hamburg, where he remained for the rest of his life.

Graupner’s Overture in F Major is scored for recorder, strings, and keyboard (5 minutes). This overture is representative of a popular form at the time, of French origin, and which commonly prefaces a set of dances. The overture’s original function was to announce the arrival of the king who would proceed slowly and regally through the hall. After the king was seated, then came a fast section full of contrapuntal acrobatics, reflecting the intellectual prowess of the king. The overture is

then rounded off with a shortened version of the slow processional material from the beginning.

Telemann’s cantata Jesus praying on the Mount of Olives is scored for voice with strings and keyboard (14 minutes). This cantata recounts Jesus’s agony in the Garden of Gethsemane on the Mount of Olives where he prayed on the eve of his crucifixion. The opening movement contrasts the “the silence of night that refreshes the weary” with the “terrifying night” full of “fear and uncertainty.” The pulsing strings depict anxious heartbeats that accompany Jesus’s trembling in the first aria—“I am saddened unto death.” The second aria appeals for hope—“My father! if it so pleases you, let the cup now pass from me.” In the final aria (Come you children of men) it is the sinner who is offered hope, comfort, and redemption.

Graupner’s Concerto in D Major is scored for solo flute with strings and keyboard (11 minutes). This concerto is full of charm, French elegance, and polite conversation. But occasionally Graupner tosses aside decorum, and the music explodes with exhilarating virtuosity. The second movement Siciliana evokes folk music with pastoral images of shepherds. With the last movement, Graupner grounds us in the German contrapuntal style, though with a delicacy that befits the gentle flute.

Graupner’s cantata Stop the arguments of Faith! is scored for voice, strings, and keyboard (14 minutes). This cantata addresses the questions of doubt in one’s faith. The opening arioso admonishes us to stop worrying— “God will heed our call!” The first aria pleads for God to have pity—“observe my misery … my sighs were in vain” while the companion recitative cries that “even those who defeat every enemy lose their fortitude when from prayer no answer follows.” The first chorale offers courage when it seems that “God has left his own.” The next aria offers hope that “Jesus does not always say no!” And the final chorale reassures us that “Await God, because you know he has mercy on you.”

Telemann’s Overture (Suite) in A Minor is scored for recorder, strings and keyboard (22 minutes). This work opens with a splendidly regal French overture (see Graupner Overture, above). After the overture, Telemann treats us to a sequence (suite) of dance-like movements that blends French, Italian, German, and some “Polish and Moravian music, all in their true barbaric beauty” (Telemann, 1740).

Les Plaisirs is a capricious movement with a mixture of elegant French gestures and Polish folk music. Then follows the Air à l’Italien, a somber aria but not without some warmth. The ensuing pair of Menuets are sifted through the elegant French courts, but come here a bit heavy-handed with displaced country beats and some garish Italian virtuosity. Réjouissance takes the other tack and rejoices with extravagant Italian virtuosity but grounded with some heavy stomping. A pair of contrasting Passepieds follow—one set is robust and the second set is gentle. The suite concludes with a regal Polonaise, a dance of Polish origins, with snapping rhythms and robust beats.

Sinfonia in F Major, “Dissonant” is scored for string orchestra with harpsichord (14 minutes).

J.S. Bach provided his eldest son, Wilhelm Friedemann, with a comprehensively supervised music education. Following in his father’s footsteps, Wilhelm Friedemann became one of the greatest organists of his generation, renowned for his improvistory skills. His compositions include church music and instrumental works, including 10 symphonies. His first post was as church organist in Dresden. Later he worked as music director for the city of Halle, and then as a private teacher and organist. He had considerable difficulties with his employers, and was notorious for his intemperance. His music is an intriguing reflection of both the strength of his talent, the completeness of his education, and the capriciousness of his character.

A newspaper review from 1774 observed that the gifted but eccentric W.F. Bach produced bold music with “just the right ingredients to set the pulse racing, fresh ideas, and striking changes of key.” The opening Vivace (Lively) of his Dissonant Symphony is full of unexpected turns, intense expressivity, capriciousness, and startling harmonic surprises. The second movement, Andante (Flowing), is an aria full of yearning and grasping, and is followed by a contrastingly jocular Allegro (Fast). The symphony gently ends with a gracious Menuetto. One trend during the early Classical period was to conclude a work with a movement of calm elegance meant to assuage any heightened emotions the listeners might have experienced, quite a departure from the exhilarating finales that today’s audiences expect.

Variations on a Theme of Frank Bridge is scored for string orchestra (27 minutes).