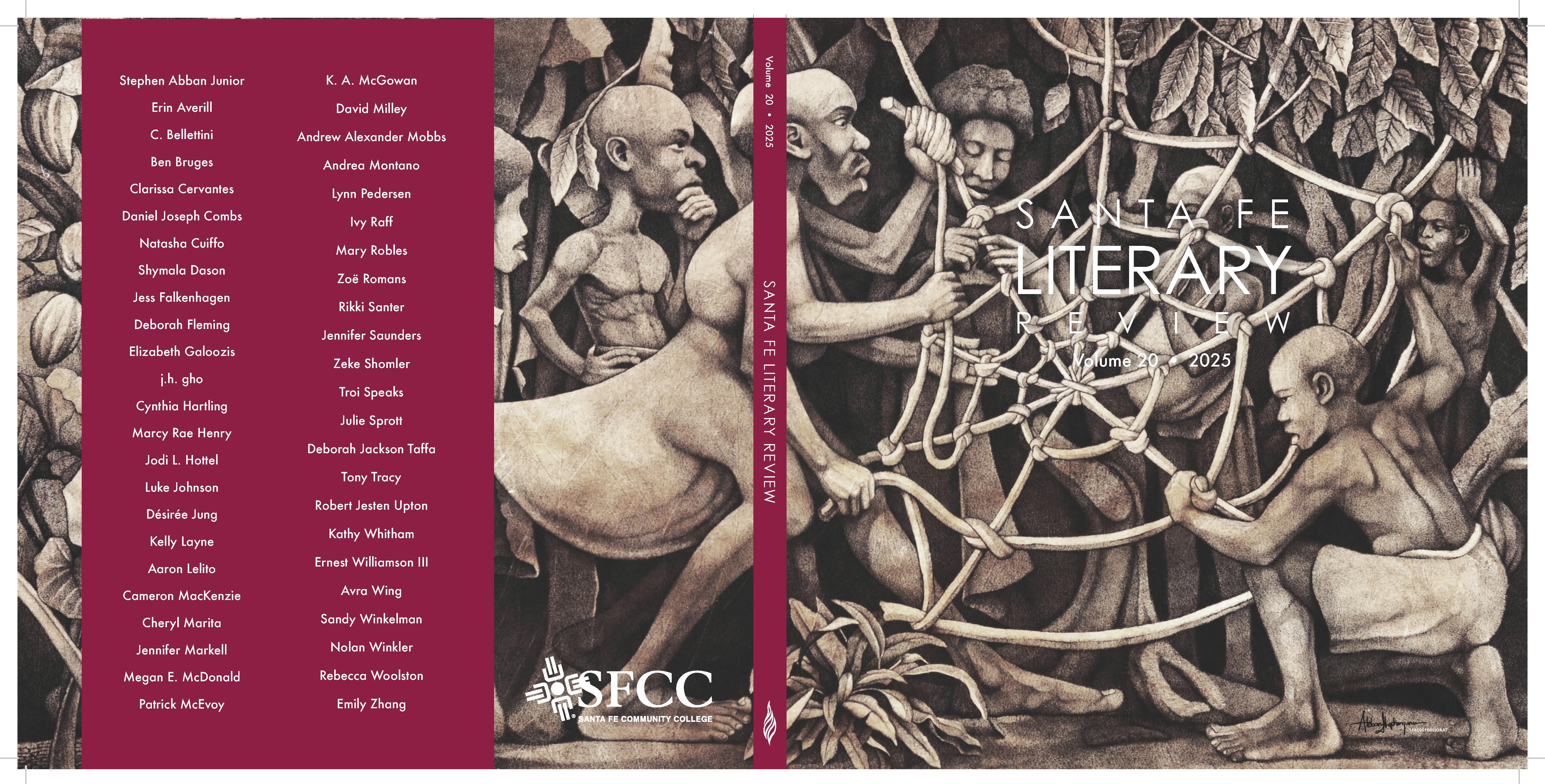

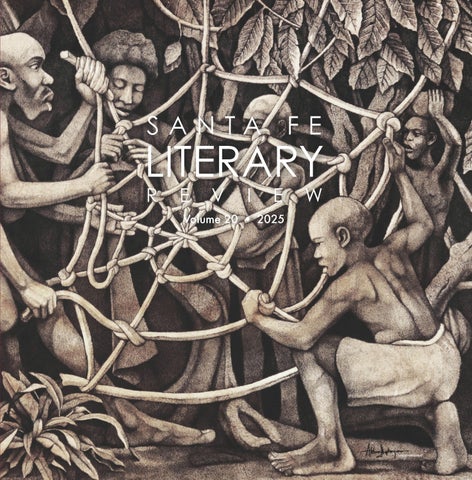

SANTA FE LITERARY

REVIEW

Volume 20 ● 2025

Faculty Advisor: Kate McCahill

SANTA FE LITERARY REVIEW

Creative Non-Fiction Editor: Susan Griego

Fiction Editor: Austin Eichelberger

Poetry Editor: Maira Rodriguez

Art Editor: AJ Wood

Copyeditor: Brittney Beauregard

Editors at Large: Bolden Begody, Jesse Colvin, Loki-Anthony Honey, Alejandra Lara, and Desiree Lopez

The Santa Fe Literary Review is published by Santa Fe Community College’s School of Liberal Arts in Santa Fe, New Mexico. With special thanks to Nancy Beauregard, Linda Cassel, Emily Drabanski, Tracey Gallegos, Andrew Gifford, Julia Goldberg, Jonathan Harrell, Sarah Hood, Tintawi Kaigziabiher, Todd Lovato, Jade McLellan, Laura Mulry, Rob Newlin, Trish Newman, Val Nye, Diane Ortiz, Margaret Peters, Adam Reilly, Serena Rodriguez, Becky Rowley, Miriam Sagan, Brian Sanford, Kelly Smith, Laura Smith, Roxanne Tapia, Briget Trujillo, and Jim Wysong. We’re also grateful to the folks at the Institute of American Indian Arts (IAIA), the SFCC Foundation, the Santa Fe Public Libraries, Pasatiempo and the Santa Fe New Mexican, the Santa Fe Reporter, and the Santa Fe Writers Project.

Santa Fe Community College acknowledges that the grounds upon which the college is built are the unceded sovereign lands of the Pueblo Nations of Cochiti, Jemez, Kewa, Nambé, Ohkay Owingeh, Pojoaque, San Felipe, San Ildefonso, Santa Ana, Tesuque, and Zia. The Santa Fe Literary Review recognizes and respects Indigenous Peoples as the original and current stewards of the land upon which we create and publish.

Copyright © 2025 by Santa Fe Community College

FROM THE EDITORS

Here in Santa Fe, New Mexico, at just the right time of day, the mountain range overlooking our city glows a salmon pink. Sangre de Christo, these peaks are called— “the blood of Christ.” Here beneath those mountains in the storied City Different, families bleed into each other and diverge again. Travelers come and go. Writers and artists still flock to this scrappy town, a place that, newcomers are told, either embraces you instantly or spits you out. We all leave a bit of our stories, our bloodlines, beneath the shadow of the Sangre de Christo range.

In the poems, stories, essays, and pieces of art that punctuate this issue, voices and images created far beyond the reaches of the Sangre de Christo examine that which we’re born with—and the pieces of ourselves that we’ll leave behind. In these pages, storytelling becomes at once our inheritance and our destiny, each narrative straddled by a reclaimed present. Making art, after all, is to recreate ourselves, to define our own existence in spite of—or in thanks to—our bloodlines.

In the end, we’ll all become stories.

Margaret Atwood

MARCY RAE HENRY

MARCY RAE HENRY

ERNEST WILLIAMSON III

ERNEST WILLIAMSON III

ZEKE SHOMLER | HYDROLOGY

When my father’s daughter washed my dark hair in the war m midwestern gutter-rain, pink bubbles traveled down the hill in little rivers as if racing toward some other, safer life. We didn’t know, then, how phthalates and parabens could disrupt the cells of animals, slipping into muscle and marrow as a hand slips behind a closing door to stop the latch. I only saw the greenness of the yard, warm with light and swarming with mosquitoes, where we found four rabbit kits clustered like closed white flowers and tense with the fear of feral cats. There were no fences there, between the houses, only open space to watch the storm-clouds rolling in and reaching their green fingers toward the earth. My sister smells like nicotine and hair oil. She washed me in the foment of the summer rain, the first time I was baptized, the only one I still believe in. Faith in something larger than myself comes easily; to find its name requires a complex mathematics I have yet to learn. I am not my father, but I’ve sown seeds of this world’s unmaking, rinsed my scalp and poured the water-waste into a living mouth. I strain my neck to see the next downpour, anticipating lightning like each new year of my inevitable and damage-stricken life. When my hair was clean, my sister held me to her chest to hear my breathing.

C. BELLETTINI | CROSSING THE RIVER

This morning, I woke up to the sound of Grandmother’s prayer beads flowing through her fingers, clicking her simple gold wedding band. The only piece of jewelry we didn’t sell because she put it on when she was 16, and we couldn’t remove it even after the soup became water.

There is no space in this tiny apartment that I share with her, my mother, and my brother. He tries his best to forget by spending the night with the cheap lipsticks he meets at the Club Zhavago. Nobody says anything about the cloud of perfume he leaves behind after one of his expeditions. We ignore the whole squalid spectacle like some beggar on the street we cannot afford to see.

My grandmother has put the eye on me. I walk up the stairs from the subway, I wait at the bus stop in the night, and I am safe. After the soldiers crossed the river, the gulf between childhood and the person I am now is so wide there is no bridge. But here in America, my grandmother’s eye is a powerful thing, stronger than death.

I pack cardboard boxes with plastic objects in a warehouse without windows. I work every day except Monday. At night, I learn how to be a phlebotomist. My lips move around the word: fill-bottom-must. I am not afraid of blood. I put in the best IV. The instructor even told me so: “Jelena, you are a natural. I didn’t even feel it. Nice job.” I smile. My fingers find the ping-pop of a good vein, where the needle can slide in and not blow a site when the skin is tough or the patient is dehydrated. These are the things I can do. But in the timelessness of artificial light, one more box until I am huffing and puffing running late into the classroom that will be my escape, one day

But escape is a question, like the hastily packed suitcase I left behind; I don’t really know if it exists. A white car parked by our building becomes a smoking shell, the wind whistling its tinny music through the charred interior. There are still echoes of feet running on the pavement, slamming of doors, whispers of men coming to town, tomorrow, next week, next month. When I tell my mother these things, she and my grandmother sing to me; sometimes we all cry at the lost slow sound of our voices remembering.

In the library where I go to study, on the long wooden tables carved with initials and insults, I trace over the human values of hemoglobin and hematocrit, neutrophils and monocytes with a pencil that needs sharpening. I weave into the stacks; I pull out a thin book that smells like nutmeg when I fan its pages. Sit on the floor and mouth the short lines into understanding.

In the poem, a captain on a sinking boat touches his lips with salted fingertips and imagines the softness of fresh bread, his lover’s breast. Against the spines of books, I am adrift at sea with the man in the boat. A librarian shakes me awake. She slips the book from my hands. Then she gives me a look like the ones I reserve for my brother, who is only trying to survive. We are in the same boat, trying to moor ourselves before we fill with sea.

SANDY WINKELMAN | AN ARTIST’S STATEMENT

Through the fusion of pyrography and watercolor, I celebrate the spirit of the desert animals and landscapes of the American Southwest. Each piece begins with the wood itself, where the natural grain becomes a unique foundation, reflecting the organic beauty and individuality of the land. No two canvases are ever the same, mirroring the diversity and character of the desert itself.

Inspired by the camouflage patterns of wildlife, I burn intricate designs into the wood. These patterns honor the animals’ ability to blend into their rugged environments—an essential harmony between survival and beauty. My work seeks to capture that delicate balance, where life and landscape coexist in quiet resilience.

Watercolor enhances the warmth and texture of the wood-burned images, echoing the golden sands, twilight skies, and sunlit mesas of the Southwest. This blending of fire and color brings the animals to life, inviting viewers to connect with their timeless presence and the landscapes they inhabit.

I aim to honor the region’s beauty and spirit, encouraging viewers to see the world through the lens of nature’s patterns and resilience. My art is a tribute to the desert’s power, harmony, and the creatures that call it home—an ever-present reminder of the connection between land, life, and art.

MEGAN E. M c DONALD | BLOODLINES

“Maybe she would find me more charming on account of what’s befallen me—the unexpected horror I’ve seen, the inevitable pain I’ve endured. It’s an awful truth that suffering can deepen us, give a greater luster to our colors, a richer resonance to our words.”

—The Vampire Lestat in The Queen of the Damned by Anne Rice

She and her disease spotted my blood and, excited by the prospect of continuing the night’s frenzied activity, crept toward where I huddled on the floor.

From an early age up until I had acquired the wisdom of a nine-year-old, I perceived my mother as this plurality—woman and incurable condition. She appeared to me as two distinct entities: she acted as my nurturer, clothing me, feeding me, and caring for my pains. However, with the tilt of an inauspicious glass, she became the demon responsible for stripping me naked of my strength, tearing at my young flesh and systematically draining my lifeblood away. Like the vampire responsible for speaking the words I opened with, my mother was intoxicated, not by the possibilities of life coursing through intimate veins, but rather by the power offered her in a bottle of sharp, chilled, cheap vodka.

On this particular night, her existence had become especially unbearable, so her psyche demanded a larger transfusion of liquid fire than usual. But the flames spilled over from her soul into her actions and she resorted to violence to keep herself from being burned. I can see myself, the innocent child, descending the staircase into the hell of a parental battleground.

Unfortunately, I had already been exposed to my mother’s illness: more than once I cleaned the physical residue of her drunkenness from the toilet and from her body, then laid her to rest for the night.

I should have stayed safe in bed despite the explosions of glass shattering my slumber, but my father’s distorted tones roused me. I padded my way barefoot to the living room and, in my groggy state, woke fully to the source of my father’s pain. More than the steak knife she held to his throat, it was her taunting that hurt him. She, despite threatening his life, scraping his skin with a serrated edge and causing a rash of tiny scarlet dots to stain the pale of his neck, was daring him to seize the knife from her like a man and slit her throat.

My whimper distracted them from this peculiar suicide attempt. I expected my father to rise and remedy the situation quickly. But he remained seated, forcing me to decide abruptly that if he wasn’t going to prevent his own death, thus deserting me and my younger brother, I was going to sacrifice myself, too.

The glittering shards of glass littering the floor rescued me—they tripped me and drew me close to the carpet, lodging in my tender toes. At the sight of blood flowing, my mother let the knife fall and brought her maternal instincts to bear upon my prone form. Although I recoiled from her touch, she persisted in trying to alleviate the pain she’d caused. She grasped my foot, tore the glass from my wounds, then laid her lips to my skin and sucked with all her might. The alcohol on her breath stung mightily, and I fell into a welcome state of unconsciousness.

I came to tucked into my twin bed with the antique white and gold leaf headboard, swaddled in pink gingham sheets, just as the first rosy fingers of dawn reached into the room. The night was over.

My mother eventually received professional help, but this was at a time when counseling for collateral victims—the family of the alcoholic—wasn’t indicated. I might have become a very different person due to this lack of support had I let my recollections consume me. In fact, I often wonder if they occurred exactly as I remember them, or if my impressionable young mind misinterpreted or exaggerated the scenarios. If I attempt to confirm or confront the circumstances, I am hushed and shushed, told, “We don’t talk about those things…” But all doubt is banished by my mother’s occasional threat that she will return to drinking. Though these warnings are infrequent and subtle, they are enough to trigger a deep, choking fear.

I cannot help but sometimes reflect on this “gift” I have been given: I may speak with a resonance the Vampire Lestat claims exists only in those who have endured glorious amounts of suffering. Despite my apparent acceptance of the memories, though, I could never recommend my experience to any other human being. For when interacting closely with an alcoholic, as when flirting with a vampire, one perpetually risks becoming what one is struggling against.

j.h. gho | how do scars form?

the 박수무당 said it was very likely my mother had family separated at the 38th parallel i thought of a sepia-tinged photo you once showed me, a gaggle of tan children –you pointed yourself out to me, bowl cut heavy on your head the 박수무당 said when i felt grief depressing on me it was a visit from my 외할머니, who was already gone when my mother was younger than i am today the 박수무당 said my mother bears a lineage of lives cut short, so that is my lineage too the 박수무당 said my work now is to return to my body

depressed tongue saying “ahhhhh” in the doctor’s office depressed cushion, sticky thighs crinkling medical paper “do you have a history of depression?” indigo-inked marker depressing dotted and solid lines into my chest “this is where we’ll separate tissue from muscle this is where we’ll remove your nipples this is where we’ll reattach flesh to flesh this is where the incisions will end” when i put a hand on my chest, i feel a cavity depressed where it once hung heavy i know the scars will end with my body

translations:

박수무당 / bahksu mudang / a male mudang (korean shaman) / the one i mention is trans 외할머니 / weh halmuhnee / grandmother on mother’s side / my mother’s mother

JENNIFER SAUNDERS | SETTLING THE ESTATE

after Gabrielle Calvocoressi

At first there were vestiges of her: tuna-tins in the trash can and coffee cups in the sink. Newspapers stacked unread.

The air stale and close. Then cleaners moved through the house, professional and efficient,

they scrubbed the bathroom tiles with Lysol and threw open the windows to June’s late breezes.

They emptied the refrigerator of olives and cheeses, of store-brand sliced turkey. That useless box of Arm & Hammer.

We bagged clothes for Goodwill or consignment, threw away her blown-out winter gloves.

Afterwards, after the estate sale and the strangers sliding through the house picking up stemware on the cheap, then—

then she was nowhere: that house empty as a pocket, its windows uncurtained to the street, to the neighbors,

to the mailman who kept on delivering her mail. That stuttering delay. Weeks after we’d divided and scattered

her ashes came the electricity bill, the water. She must have watched some TV, maybe she’d run a cool bath.

Her small debts lingering in the system until my brother cut a check.

BEN BRUGES | THE EXHIBIT

I'd seen newborns suck in the world and howl for the amphibian dark they've lost in birth's son et lumière

and can imagine the terror of transition: the murmuring voices suddenly shock-clear, the feeble, tenuous, shifting, partial hold in the new rhythms of this breathing medium and the feel of skin, wind on skin, the cold dry touch of skin. And yet, new parent, I wasn't prepared.

After the endless dim-lighted calm a sudden rush of green-robed medics sweep our nurse aside, intent in their silent urgency,

bristling with equipment, working as one. Given no explanation, those last moments push at eternity. Her efforts are given up on.

Left out, she becomes the site of their heroism. A last glorious rush, he's delivered, but whisked away. We're left alone, a moment that might be forever.

I pour empty reassurances into her haze. But I have to know and fear to know what's so urgent in that other lit room

and force a glimpse through the doorway at the huddle, like some dramatic tableau, surrounding, held up, gaze-fixed, there:

the exhibit, blue-hued, soundless but struggling, limbs working, face closed tight, straining, and then the first yell. He's alive, weighed, saved.

Why so resistant to birth? What held him back? After-shocks judder his tiny frame: stomach-tight moments lit equally by delight and dread.

DANIEL JOSEPH COMBS | AN ARTIST’S STATEMENT

In April 2024, my partner, Shelli Rottschafer, and I attended the annual Gathering of Nations Powwow in Albuquerque, New Mexico. It was my first time attending the Powwow. I was hoping to capture some images of the incredible regalia and the movement of the dancers. We watched from the stands as the Grand Entry took place, and around 2,000 dancers entered the arena to the rhythm of the accompanying drummers. Every inch of the arena floor was filled with dancers from tribes from around the nation and the globe. It was without a doubt one of the most moving experiences of my life.

After the Grand Entry, we made our way down to the floor level, where we found ourselves sitting next to the entrance the dancers were using to enter the arena. I sat on the floor next to other photographers and began to shoot away as the youth dancers entered to begin their portion of the Powwow. This photo captured a moment when two young girls shared a word before entering the arena. Whether they were sisters, cousins, or friends, they were certainly “Relatives” in that moment. I feel honored to have witnessed and captured this shared exchange.

DANIEL JOSEPH COMBS

JENNIFER MARKELL | WHAT A GHOST CAN DO

In the parking lot of an abandoned theater, weed-choked and starved for light, my mother’s ghost hides. I see her face in wilted leaves and acorn caps, hear her voice in a branch as it snaps, and in the silence after.

My mother’s ghost eavesdrops on my intimate conversations, waits at the crossroads of my major decisions, says I know you better than you know yourself. She looks through me, translucent as moon jelly. I turn myself inside out so my soul can escape.

She carries a photo of the two of us: mother and young daughter sitting on the hood of a Chevy in matching T-shirts, holding hands. This is love, she pronounces. When I point to the daughter’s fingernails chewed raw, she floats away.

The daughters of ghost mothers like me walk quietly. Our feet above the ground, never touching. Our lifeblood an ancient oath, do no harm. We offer the purity of our silence. Anger seizes us like a bad engine.

The week before my mother dies, she reveals the epitaph for her stone— Beloved Wife and Mother I poke at grief with a stick, drop it in a well to see how deep.

DEBORAH FLEMING | ANGEL TRAIL

Anne Grafton galloped to the edge of the grass in the park where she and her older sister Leah and friend Marcia were reenacting the latest episode from The Adventures of Spin and Marty. Marcia insisted on playing Spin, Leah played the role of Marty, and Anne was a wild horse they were trying to catch. From an opening in the brush, barely visible, the path called Angel Trail descended the steep hillside until it disappeared among the trees. All the kids knew how to make their voices echo by shouting into that valley. Marcia had once claimed that the echo was someone trapped in the woods calling back for help, but when Anne repeated the story, her mother told her it was a fable.

“Don’t go down that trail,” Marcia cautioned, peering through glasses that were thick as the bottom of a Coke bottle and made her eyes look bigger than they really were. “Hobos live in the woods.”

Anne was seven, her sister eight, and Marcia nine, so naturally Marcia was the one who decided where they went and what game they played. Her age as well as the fact that she rode a bus to the Catholic school while Anne and Leah walked to their school gave her added status. Her fair hair was a mass of curls created in a styling salon, while their mother cut Leah’s and Anne’s hair. Marcia also had every toy as soon as it was advertised on television, and she always made a special trip to their house to show them. Her playroom was filled with toys, more than twice what Anne and Leah had together. Whenever they asked to go to Marcia’s to play, their mother always told them to come back together, but they seldom did.

“What’ll the hobos do?” Anne asked.

“They’ll kidnap you,” Leah explained. She was usually less assertive when Marcia was around. “They’ll take you to the railroad yard where they camp out until the trains come. Then they jump onto the cars and make their getaway.” Anne wasn’t sure whether to believe Leah because her sister sometimes told fibs, which weren’t as bad as lies. Anne was not sure of the difference between the two, or between a fib and a fable, especially since they were all stories.

Anne and Leah knew what it was to ride the train because their father, who worked for the railroad, got two free tickets every year. Anne had been fascinated by the enormous size of the locomotive engine, the way the platform trembled when it pulled into the station, and the shiny steel tracks on the bed of black cinders. Once, when the teacher told everyone to explain what their fathers did for a living, Anne had been embarrassed because everyone else’s

father worked in one of the steel mills across the river from Lafayette, Ohio; they were rollers, machinists, or foremen, and when Anne had to say that her father was a block operator for the railroad, the kids turned their heads and wrinkled their noses at her. Marcia’s father didn’t work in the mill, either, but he traveled to many places selling things and brought her presents from every city he visited. Neither Anne nor Leah had ever seen him.

“You can go down there when you’re older,” Marcia corrected Leah. She always contradicted anyone who volunteered information before she did or seemed to know something she did not. “A girl from our school walked all the way down, but she was in high school. She said the path goes to the river. Hobos don’t bother kids that old. They’ll only take younger ones. That’s why it’s called Angel Trail—because a little girl named Angel went down there once and they never found her again.”

Anne and Leah had often seen the river with its twin bridges, the black one the trains used and the silver-gray one for cars crossing over to the West Virginia side. The tires always sounded different when they drove on the bridge made of steel girders with wide gaps between them, so you could see the river beneath. The mills looked like little cities all lit up, with high, round towers the kids named “cloud makers” because they spewed out white smoke. There was something mysterious about the wide gray river winding among the wooded hills and flat barges pushed by tugboats. People warned children not to walk on the steep banks because every so often, someone fell in and drowned in the fast current. Even from as far away as the road, Anne had seen waves curling on the surface. Nobody wanted to live down there because the poorest people lived closest to the river while richer ones lived on the hilltops.

Anne cautiously peered into the dark woods as far as she could.

“Mommy’ll be mad if you get your shoes muddy,” her sister admonished. Yes, their mother would be mad if she ruined her shoes, but Anne and Leah were used to their mother’s temper.

“I’ll go and take a look,” Marcia said with the pride of the eldest.

“Aren’t you afraid?” Anne asked.

“Hobos probably wouldn’t want kids as old as Leah and me,” Marcia answered. “But they’d take you, so you better be careful and stick with us.” She started toward the head of the path.

Then she tur ned. “Look there,” she said, pointing toward the ground. “A red cloth.”

Anne stared where the older girl pointed. The trail bent around a large rock halfcovered by underbrush where a dirty red rag lay among pine needles, rotting leaves, and fallen twigs.

“A hobo bundle!” Marcia yelled as she took off across the grass toward the street. Leah followed, shouting and running as fast as she could.

The combination of two girls screaming overcame Anne’s curiosity. She started after them calling “Wait! Wait!” as the thrill of fear rose from her heart along the back of her throat to the top of her head. She could barely control her own legs.

“Wait! Wait!” Marcia turned and mimicked her; Leah followed suit.

“When we get home, I’ll tell Mommy on you,” Anne shouted when she reached them. “I’ll tell her you ran away from me.” Her lungs ached as she tried to catch her breath.

“Go ahead and tell,” Leah taunted, hands on her hips, wagging her head back and forth and sticking her tongue out.

“Let’s play without her,” Marcia said, and she and Leah strode away from the field toward the street.

“You wait!” Anne cried, angrily pursuing them, but they started running away from her. Tears filled Anne’s eyes and closed her throat as she tripped over a jagged edge of broken concrete and fell onto the gritty pavement. Sitting on the ground, she examined her scraped and bloody knees below the plaid shorts she had worn that day—a birthday present. Although the skin stung, she brushed the dirt off and looked up to see Marcia and Leah far in the distance. They had stopped running and were talking to each other as they walked, not bothering to glance back to see if she was all right.

Full of rage, Anne tur ned and headed back toward the park. She had followed Leah and Marcia here enough times that she could find her way home without them. At first determined to tell on her sister, Anne realized as she paced off the distance that her mother would probably scold her instead and tell her she couldn’t play in the park anymore. She would just have to say she had tripped when she was running. Leah wouldn’t be able to make fun of her without confessing that she and Marcia had run away from Anne.

When she reached the park, Anne crossed the grass, stepped warily toward the hillside, and peered down the slope into the woods. Early in the morning, dense fog shrouded

the hills until only the first row of ghostly trees was visible, reminding her of a story, “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow,” that her teacher had read to the class last year at Halloween. Anne wondered whether Marcia had told the truth about older kids being able to explore without being kidnapped by hobos, and whether she really knew a girl who had walked all the way down to the river. Marcia often changed her tales about people and places in the neighborhood, and yet somehow she was never called a liar as Anne was whenever she added details to make a story more interesting.

Caught in thor ny vines at the edge of the slope, the wet rag lay sodden and dirty. It looked less like a hobo bundle than the kind of large handkerchief that cowboys wore around their necks in movies or TV shows. Someone must have lost it when he walked down into the woods.

Anne strode back up from the trail. Furious with Marcia for telling a lie, at the same time Anne felt disappointed that the red cloth had not been a hobo bundle; she liked the idea that hobos lived in the woods and rode trains wherever they wanted to go. She would ask her father whether hobos really lived in the railroad yards. One day, she’d follow that trail all the way down to the river without her sister or anyone else. In the meantime, she galloped up and down the grass, tossing her head, a wild horse nobody could catch.

LUKE JOHNSON | CHIMERA

Tonight, rain drapes the blue acacia

& the streetlights shimmer, shroud the cars in shadows. My sick, who calls herself daughter, points at how the blossoms curl to cocoons then commit themselves to air. She wants to know where the scavengers take them, & why at night when her name emerges, they come so close

she could reach a hand, stroke their knotted pelt.

Pretend she says, this is all a dream,

& when we wake we are bodiless voices, vapors

framed in mist. We watch I Love Lucy.

Take turns singing Frank Sinatra, then sit by the window waiting for fawns, the little ones lost from their mothers.

As a boy, my father wiped dust from a rifle then slowly framed a five point & blew until the birds burst & the beast lay

still in the reeds. In the reeds, a womb revealed a doe unborn, & my father, lost, spared me the sight, before slipping

Long before this, when my mom was small & her father had not died from cancer, she was wrestled from dream by invisible force & found, when waking,

it into the stream. I confess, when the beast fell & baby sank, I could hear a hum erupt from water then sweep across the fields. It fell like snow

over flowerless trees & loomed, large,

like an angelic chill, stalking the news of the living.

a wounded robin, flapping against the floor.

She bathed the bird & fed it.

Gave it drops of water, a bed, & set it near a lamp to warm its wing.

In the morning, yes, the bird was gone,

but for a single feather, & my mom

began to weep for hours, afraid

of what she’d done. That Fall her father died & the birds no longer shared the news nor squabbled the streets for seed. It was as if everything stopped, she tells me. No more music son, no mystery.

Tonight, rain drapes the blue acacia & sores surface my daughter’s skin, radiate into her stomach. I sprinkle lavender, water, stutter over a prayer. Place my palm upon her body & beg the beast to transfer pain & seed its gales inside me.

CLARISSA CERVANTES | AN ARTIST’S STATEMENT

My work explores the significance of the word lineage as defined by Merriam-Webster: “a group of individuals tracing decent from a common ancestor […] especially such a group of persons whose common ancestor is regarded as its founder.” The origin of the Flamenco Art can be traced to Andalusia and other parts of Spain as early as the 15th Century. Traditional Flamenco performances involve music, poetry, singing, and dancing. Flamenco female dancers typically wear elaborate ruffle dresses, some with polka dots, while others might choose stripes with bright and vibrant colors as well as the typical flamenco shoes, where nails are embedded front and back to enhance the sound. My black and white photography composition was taken during a Flamenco performance as an invitation to add your own colors and sounds into the picture while dancers gather before the last song.

CLARISSA CERVANTES | LINEAGE

CHERYL MARITA | BECOMING HUMAN

I’d never told anyone. It was a secret, even though everyone could see it. I was part lizard. That day in second grade, in the Epiphany Grade School girls’ play yard, the secret was revealed. Terror rose up my back, crawled under my skin.

The schoolyard didn’t have any place to sit. Recess meant jump rope for coordinated kids, not someone like me. There was a huge oak tree growing in the middle of the courtyard, surrounded by concrete. Judy and I sat with our backs to the tree, pulling our skirts under our legs for protection from the prickly twigs on the cold ground. We wore pants at home, but the nuns said pants were “evil.” I thought the Dominican nuns were evil. I snuck my new Silly Putty into school in my sweater pocket. We pulled it, popped it, made imprints of sticks and rocks. Judy told me secrets about her family, like the time her mother squished her between the rollers on their washing machine and then had to blow her up like a balloon. Gullible, I asked, “Did your bones crunch?” That day, I thought she would tell me more secrets. Instead, she asked, “If you’re adopted, where did you come from?”

I’d known I was adopted long before grade school. My mother was a proud rescuer of unwanted children and bragged about saving me and my brother. We had to go to St. Vincent’s Orphanage every year to be exhibited before Sister Mary Alice. Mom wanted to show off how well we were being cared for. If only Sister Mary Alice knew. As for Judy’s question that fateful day, the answer slithered out of my mouth, “I was hatched from an egg. I’m part lizard.”

And so it began. Soon, the whole second grade knew I was an alien, like the one in Twilight Zone. He was a grown-up, hidden in the back room of his mother’s house. He had lizard arms, legs, and scaly skin but a human-sized body. I had the signs—my skin was cracked, crusty, bloody. My parents wrapped me in gauze and took me to special doctors to get help, but nothing worked. I was defective, a lizard girl. Twilight Zone was as real to me as the news. Curiosity and questions were not tolerated in my household, so my birth mythology festered.

Waiting at the stoplight on the way home from school in sixth grade, I tried to become invisible, but the boy next to me saw the latest changes in my skin. “Yuck, your neck is black! You’re dirty! Get away from me!” He ran off while I dragged myself home. I assumed that

the lizard in me was taking over, but I was too scared to say anything to my parents. Mom threatened that if I didn’t behave, she would take me back to the orphanage. Being part lizard would certainly qualify for a reason to return me. But my mother decided to help, and started bleaching my neck every week. We let my hair grow longer to hide the nasty change, but we never talked about what was happening.

As I grew up, my scaly skin got worse. My wrists would leak yellow sticky fluid and blood onto my school worksheets. The creases in my elbows were thick with old blood and scales. The calves of my legs dripped blood onto the cuffs of my white socks. I was a mess before I even arrived at school. The nuns marked my work down because it was messy. After school, I ran eight blocks home to hide.

Somehow, my parents learned about a doctor on Chicago’s south side, a dermatologist who worked with children. We lived in Little Village, the Bohemian settlement on the west side of Chicago. Our stores sold Bohemian food. We spoke Bohemian. We were not allowed to even look at public school kids. We were white, Catholic, Bohemian, and proud— so proud we hated everyone else, or so I was taught. How my parents ended up driving me across the city every week to a Black doctor for Vitamin A shots is still a mystery. Mom didn’t call him Black. She only used the “N” word. She truly hated everyone who didn’t look like her.

The shots hurt a lot. I cried a lot. I wondered if she was punishing me for being defective, for being part lizard. Did she hate me as much as she hated everyone else? Finally, after a year of weekly shots, the torture ended. It never worked, never changed the bleeding, the oozing, or the scales.

High schoolers didn’t care about how I looked since they didn’t see me. I blended into the newspaper office, the Militaires Marching Rifle Squad, the Future Nurses’ Club. Long sleeves and coats covered my skin. My weekly newspaper column, Beatlemania, got rave reviews, although no one knew the quiet, cloaked girl was the author. I wore a beige trench coat yearround. Sometimes I pictured my black lizard tongue around the necks of football jocks when they heckled girls with insults, but most of the time I just hid inside the beige tent of a coat.

Nursing school was harder, as some patients refused to let me care for them if my arms were cracked and draining. Our uniforms were short sleeved, the nuns refusing any exceptions

for my skin condition. My classmates accepted my disease and my brain. I was smart, secretary for the class of ’67, but clumsy. I managed to trip, dousing my very prim Southern belle teacher with a liter of patient urine. Between that incident, my inept bed-making of poorly mitered corners, and the times I refused to give up my seat to a doctor, Sister Superior called me into her office to tell me I had to leave school a month before graduation. My lizard self rose up, clawing the air. I graduated, top of the class, carrying red roses. A poem I wrote was part of the graduation program.

Years later, I would learn the truth. I had a rare skin condition. I was human, and my skin healed itself when I turned forty, which was typical for the disease. All those years of feeling defective, yet almost enjoying the lizard in me. I wanted something to connect to, some bloodline to my past. I wasn’t hatched, but who, or what, was I?

I learned biology and genetics in nursing school, and later, with the births of two healthy human children, I knew my lizard fantasy was only a coping tool for the layers of rejection that adopted children normally feel.

Ancestry.com offered magic to someone like me, someone who would rub an Aladdin’s lamp believing a genie would appear. I told my kids, “Finally, with Ancestry, I’ll find my birth parents. I’m signing up today!” It was 2012. I was one of the first people to submit a DNA sample. Not much happened. The DNA did confirm information St. Vincent’s hospital had sent me back in 1996 in a “non-identifying information” letter, information about my sweet birth mother and my unknown Greek birth father. A few years later, I dropped my membership after some futile attempts to contact eighth and ninth twice-removed cousins. I told my friends, “It’s not worth it. I’ll never find anyone.”

But I never stopped wondering. Years later, I resumed my quest to find out something, anything, about my birth parents. I decided to protest the Illinois closed adoption rules. In 2018, I planned to fly to Chicago, pound on the desk at the Bureau of Vital Statistics Office, and demand a copy of my original birth certificate. My son calmly said over the phone, “Why don’t you call instead?”

I wonder if he’d looked up the Illinois adoption laws while we’d talked. (He’s such a kind, wise man.) If he had, he would have seen that Illinois changed closed adoption laws in

2011, and with a completed one-page form and $15, I could have a copy of my original birth certificate.

Two weeks later, I tore open an envelope stamped “Illinois Adoption Registry.” I plopped down into the chair my grandfather had died in decades earlier. I need your support. What if there aren’t any names on my birth certificate? What if no one wanted to admit that I had a human birth? What if…

I couldn’t unfold the paper. I couldn’t look. I’d been a lizard my whole childhood, then a bastard baby throughout my teens. When I became a nurse, I felt connected to women before me, even Florence Nightingale. When I refused to give my seat to a doctor, I asked Florence to stand by me. She was a rebel who changed the world. I wouldn’t change the world, but she changed me.

As I sat there with the folded birth certificate, I looked at my wrists. At 72, I was older, wiser. Even my tissue-paper skin was more supple than in second grade. When I became a mother, I truly didn’t know how to be one. I just knew to do everything opposite to what Evelyn, my adopted mother, had done. I loved being a mother. I taught my children to take risks. I need to do the same.

I opened my birth certificate. I had a birth mother: Freda Greb. I had a name: Marita Clara Greb. I didn’t have a father: unknown. Someone witnessed my birth, was with Freda when I was born. Someone put one percent silver nitrate in my eyes and recorded it on paper.

Human eyes, a human body.

ELIZABETH GALOOZIS | they made us

they taught us how to swim. bright, squeaky wings buoying us until we could push the wall away. nothing elegant. no strokes that would win us medals or even save our lives. but we could cannonball into the complex pool and make it to the other side.

we’d pull each other’s hair sometimes, then. shove each other just to get our own space. acting our ages.

and them. only twenty years on us, acting their ages, slamming doors and calling names we hadn’t learned yet.

// sometimes they dressed us in the same dresses, one red, one blue. sat us shoulder to shoulder in the portrait studio,

already facing divergent directions. when we moved on from shoving to words, they made us write nice things about each other. we’d ask each other for ideas. you’re nice, you’re pretty, what else. they seemed to do the opposite themselves.

// here we are now. an archipelago instead of a tree. whether it’s swimming distance, I can’t say. the gaps shrink and grow with the tides. they made us without knowing how to make us know. our knowing is what we made ourselves. a system of signals. a rope bridge crafted in the dark. you are the only one who swims the way I do.

NOLAN WINKLER | AN ARTIST’S STATEMENT

“A bird does not sing because it has something to say. It sings because it has a song.”

—Chinese Proverb

I paint with emotions moving the brush and my favored music playing loudly in my studio. I paint not to give advice, but to garner questions while giving no answers. It is for you, the viewer, to react in a manner that suits your senses.

I paint because it is what I do. I paint because I love the act of not knowing what I am going to paint but letting the paint and the music move me. An accident will happen sooner or later, and since I have been painting for so long, I recognize that and go with whatever that accident has to offer. My work is inspired by the paint, the music, and often by poetry and lyrics.

NOLAN WINKLER | ALLOW ME ONE MORE CHANCE

MARY ROBLES | DRESSING FROM MEMORY

My father taught me how to drink Tecate and how to drink myself to death. As a little girl, I knew the comingled scent of lime & salt & beer on his laugh, his laughing breath. Once, he told me that Tecate meant to put it on, like a shimmering of feathers, like the black eagle in the hero stance, bearing its wide chest across the label. Early on, I learned the taste, and the way to suck the foam and in my spinning mind I felt him close, death / my father / bitter, salt-with-soured-lime. The eagle emblem in his hand flowing tender ness & dread, and the name Tecate,

meant my father’s tongue gone sharp with salt & tang as he flew upward without memory. Then as if we had dreamt him up, as if descended from the golden hazes, Death found my father sitting alone in his bed. Death tore a piece of red ribbon from his shirt and gave it to my father to wear as a tie. So my father put it on (like he was told, Tecate.) Ever since that day, my father wore the ribbon as a lock of woman’s hair, wrapped long around his neck. He couldn’t live in the world anymore, he tur ned his back away and sucked the last faint taste of alcohol

from the tangled scrap of the agave’s skirt. Then he fell bur ning into the earth, then he learned to drink the dirt. Pobrecito, I drank to him. T inge of lime saliva, you could call this kind of love a tor ment.

Death stayed with me a long time and went among my family like a dream, bringing a little song of smoke. Bringing an angry woman’s tender ness he wended numbly into rooms. He went into the house, he went writhing in the bed sheets. He undid all the clothing, stripped the fingers ring-by-ring. He pulled feathers from the riverbed and my grandmother tore within his hand.

She would have bur ned but Death was soft with her, and simply tore away her sleep in bed like petals, in the canyon, where my grandfather erupted in his tears. All of this was just a song, Death said and it was up to me to numb my head, and taste the salt, push the limes into the beers, forget. Death offered a gown of so many ribbons to me, held it in his fingers. He said I’d only hurt so long, and he said Tecate, put it on, put it on.

I still dream in drunken rivers where my father sucks the stones, my sleep is black with eagle feathers, I still dream in drunken rivers.

ERIN AVERILL | HOWL

Adjusting the scope on his rifle, he located the outline of the decomposing angus carcass a couple hundred yards away. The moon waxed bright over the open stretch of grama grasses encircled by a dense conglomerate of scrub oak and piñon. Third time he had to re-pitch his tent this week. Wind patterns kept shifting. Needed to be downwind of the original kill site.

He was just doing his job. It was an order from headquarters. But after a string of 16hour shifts, alone in the remote pockets of the Gila Wilderness, questions were starting to surface.

This was Mike’s dream job since he could remember. Grew up on a ranch in southeast Arizona, an hour past the New Mexico state line, just southwest of the Gila and Apache National Forests. As soon as he was old enough to (legally) drive, every weekend was spent under the looming gaze of the evergreens. He was always more interested in looking out for the raptors, reptiles, and pronghorns than running cattle with his dad and brother.

When he was younger, he often wondered what things were like when there were still wolves in the forest. Extirpated before he was born. Ranchers and feds teamed up to eradicate all the Mexican wolves north of the U.S.-Mexico border in the seventies. He understood why the ranchers didn’t like them. It was simple—they killed cattle. In the earlier days, when his grandfather’s grandfathers were running things, food was more scarce and children more numerous. A dead cow could mean empty plates which could mean a dead kid. And now, margins on ranching were thin. It was why some fudged their herd numbers and sent them off to feedlots young. Commercial beef makes more money if you fatten up steers and heifers on corn and undisclosed hormones instead of grass alone.

In the game of man versus wild, man won fair and square. They had spent decades, a couple centuries even, toiling to master this dominion. Never mind the Natives who cohabitated this terrain with other apex predators for thousands of years prior. Removing the wolves was a sign of success. Civilized behavior. Peak human evolution. Less wolves also meant more deer and elk to hunt. A win-win. But then environmentalists started making noise, and the battle to reintroduce them grew fierce.

Captive-breeding campaigns were underway when Mike entered high school. He thought about studying wildlife biology, but college was expensive, so he went straight to working a long string of seasonal jobs at different agencies throughout the Southwest. Even

spent a couple seasons doing trail maintenance in the Grand Canyon. But his heart never stopped pining for the Gila.

Those roles were almost as rare as the Mexican wolves. He bided his time, building up his resume, bouncing through a few state park ranger positions in Utah and Arizona. Then one day, that dream job finally opened up, after nearly two decades of patience and determination. He packed the few belongings he had and made his way to New Mexico.

Cracks in the sheen of his fantasy soon emerged. Too-loud whispers of backdoor deals with ranchers to thwart proposed conservation easements. Protocol was to look the other way when the terms of existing ones weren’t adhered to, with landowners still pocketing the extra cash, making sure to kickback a little to the feds who didn’t give a damn if all the creatures in the forest lived or died. Intimidation of environmentalists was common. Entertainment. A few warning shots fired here and there never hurt anyone. Any related reports or complaints swept under the rug.

Mike developed a reputation for being a rule follower, for not wanting to get involved in these kinds of negotiations. His more jaded coworkers could smell his green as soon as his truck approached the parking lot.

One day, he was called into a meeting with his boss’s boss’s boss’s boss at the USDA. A wolfpack killed some cows on a high-priority grazing allotment. Needed to be taken care of.

“Consider this an initiation,” boss man said.

So here he was, camping out in the Gila, just like he had done hundreds of times as a teenager. Except this time, the scope on his hunting rifle wasn’t searching for deer, but for wolves. He had heard some howls over the past week. After each initial chorus, they only seemed to move further away. Always was tempted to follow, but he knew it was better to exercise patience and stay put.

The night sky was shifting from indigo to azure. Dawn was approaching. In a few hours, the sun would peek out over the trees. If he didn’t find them before ten, he would give himself a day to recharge before coming back out. At least he was getting overtime for this. How does one hunt the forest’s greatest predator? As this question floated his consciousness, a doe darted through the clearing in front of him.

When he heard it, a chill like none before sprinted up his spine. First a shrill bark, then a prolonged, aching howl. Couldn’t be more than a mile away. The exhaustion Mike accumulated over the past week evaporated. He was alert. Heart punching into his ribcage.

Quietly, he pointed the barrel of the rifle towards the meadow. Within a few minutes, he heard distant footsteps fast approaching. The lurking crunch of dried pine needles carpeting the earth was hardly perceptible to the human ear. He cocked the firing pin into place. Peering through the scope, he put his finger on the trigger and took a deep breath.

NOLAN WINKLER | THE BLOOD

Good Luck

Good Luck

Xie xie! (谢谢)

Good Luck

EMILY ZHANG | GOOD LUCK

Good Luck

Xie xie! (谢谢)

Xie xie! (谢谢)

Xie xie!

Xie xie! (谢谢)

we say as children when we receive hong bao (红包 ) during the New Year, money in red envelopes adorned with Chinese characters glimmering gold in the light each time we change the angle.

we say as children when we receive hong bao (红包 ) during the New Year, money in red envelopes adorned with Chinese characters glimmering gold in the light each time we change the angle.

we say as children when we receive hong bao (红包 ) during the New Year, money in red envelopes adorned with Chinese characters glimmering gold in the light each time we change the angle.

we say as children when we receive hong bao during the New Year, money in red envelopes adorned with Chinese characters glimmering gold in the light each time we change the angle.

we say as children when we receive hong bao (红包 ) during the New Year, money in red envelopes adorned with Chinese characters glimmering gold in the light each time we change the angle.

Once guests leave, you take my hong bao and keep it safe, saved for the future, soon to be used for classes, clothes, trinkets, toys— you bought me a red hoodie imprinted with bok choy, jiao zi (饺子 ), with mandarin oranges, to wear on special occasions. Always

Once guests leave, you take my hong bao and keep it safe, saved for the future, soon to be used for classes, clothes, trinkets, toys— you bought me a red hoodie imprinted with bok choy, jiao zi (饺子 ), with mandarin oranges, to wear on special occasions. Always

Once guests leave, you take my hong bao and keep it safe, saved for the future, soon to be used for classes, clothes, trinkets, toys— you bought me a red hoodie imprinted with bok choy, jiao zi (饺子 ), with mandarin oranges, to wear on special occasions. Always

Once guests leave, you take my hong bao and keep it safe, saved for the future, soon to be used for classes, clothes, trinkets, toys— you bought me a red hoodie imprinted with bok choy, jiao zi with mandarin oranges, to wear on special occasions. Always

wear red on important days; good luck will prevail. Red is lucky, you tell me.

wear red on important days; good luck will prevail. Red is lucky, you tell me.

The color of fortune, luck, and prosperity, glimmering against the Eiffel Tower, lighting up dozens of casinos sprinkled across Macau.

wear red on important days; good luck will prevail. Red is lucky, you tell me. The color of fortune, luck, and prosperity, glimmering against the Eiffel Tower, lighting up dozens of casinos sprinkled across Macau. In preparation for Chinese New Year, mandarin oranges beckon in their dining table nest: Don’t eat these! They’ll bring you good luck! every time I reach unknowingly for one. Instead you offer da bai tu (大白兔 ), milk candy, smooth to the touch. It’s a special day! Melting slowly in my mouth, the hard candy’s rice paper flakes off, bit by bit, until milk fills my mouth.

The color of fortune, luck, and prosperity, glimmering against the Eiffel Tower, lighting up dozens of casinos sprinkled across Macau. In preparation for Chinese New Year, mandarin

In preparation for Chinese New Year, mandarin

oranges beckon in their dining table nest: Don’t eat these! They’ll bring you good luck! every time I reach unknowingly for one. Instead you offer da bai tu (大白兔 ), milk candy, smooth to the touch. It’s a special day! Melting slowly in my mouth, the hard candy’s rice paper

wear red on important days; good luck will prevail. Red is lucky, you tell me. The color of fortune, luck, and prosperity, glimmering against the Eiffel Tower, lighting up dozens of casinos sprinkled across Macau. In preparation for Chinese New Year, mandarin

Once guests leave, you take my hong bao and keep it safe, saved for the future, soon to be used for classes, clothes, trinkets, toys— you bought me a red hoodie imprinted with bok choy, jiao zi (饺子 ), with mandarin oranges, to wear on special occasions. Always wear red on important days; good luck will prevail. Red is lucky, you tell me. The color of fortune, luck, and prosperity, glimmering against the Eiffel Tower, lighting up dozens of casinos sprinkled across Macau. In preparation for Chinese New Year, mandarin

oranges beckon in their dining table nest: Don’t eat these! They’ll bring you good luck! every time I reach unknowingly for one. Instead you offer da bai tu , milk candy, smooth to the touch. It’s a special day! Melting slowly in my mouth, the hard candy’s rice paper flakes off, bit by bit, until milk fills my mouth.

flakes off, bit by bit, until milk fills my mouth.

oranges beckon in their dining table nest: Don’t eat these! They’ll bring you good luck! every time I reach unknowingly for one. Instead you offer da bai tu (大白兔 ), milk candy, smooth to the touch. It’s a special day! Melting slowly in my mouth, the hard candy’s rice paper

oranges beckon in their dining table nest: Don’t eat these! They’ll bring you good luck! every time I reach unknowingly for one. Instead you offer da bai tu (大白兔 ), milk candy, smooth to the touch. It’s a special day! Melting slowly in my mouth, the hard candy’s rice paper

flakes off, bit by bit, until milk fills my mouth.

flakes off, bit by bit, until milk fills my mouth.

DÉSIRÉE JUNG | ON THE RIGHTS OF

BEING MAD

If this is an unspoken residue of something unarticulated during my birth, time will tell. From this moment on, the only thing I can do is speculate from the intuited inscriptions etched by the words that write me: an I who unknows herself as mad for an entire life until making it into her cure, and an irreparable love, suddenly creating an unthinkable destiny, once crazy. By recognizing myself as mad, I open the doors to the resignification and reappropriation of my own body. On the rights of being mad is a gesture of renovation to redirect an ancestral order: obey and fulfill an outside judge (not by chance, the name of my city of birth, also called Juiz de Fora in Portuguese).

The rigour of this jurisprudence over my small being is at its maximum efficiency in most of my lifetime, or even before it, I should say. A desire of submission and rebelliousness incarnated in one single knot tying all my law books together while, intimately, urging me to reinvent ways of survival, never of living, for such was not an option, it being improper, dirty.

Ever since I was a little girl, I had the habit of calling this outside judge my foreman, cruel father, extreme law, superego, enforcer of excessive enjoyment, at last, an interiorized exacerbated control forbidding me to desire outside its law (once I had no clue of my own).

But what does it mean to desire outside the law? Is it to be madly passionate, or to be unconscious of one’s own enjoyment? Which madness are we talking about? Incest? Or the transgression and reestablishment of a limit whereby excessive enjoyment opens space for pleasure and love in their purest and unthinkable expressions? This arc, this art of being sexuated and inhabiting a body, appears easy but is impossible in its complete articulation. Sexuality, if acted upon, is an occurrence that brings with it the measure of its own improvisation, which often rhymes with the unmanageable.

Before this conundrum, there is always the risk of facing an unconsciousness deriving from ancestral times, the malign retour of an unceasing repetition demanding more and more in an excessive cruel reset, desirous of an insane sameness. Why is it important to talk about this? There is coherence in my incoherence. I want to state that by understanding my rights of being mad as a choice and not as repetition or destiny, such sentence is set free. And what is madness for me? Irrationality is unknowing how to articulate every single thing by the laws of the mind which judges the body by its reasonable circumstances only, coding without negotiation and excessively enabling its negations.

It goes like this: if you do this, you will win a moment’s respite. How? By placing and replacing one same object in the same position a thousand times over, by thinking excessively about death, by cultivating an altar for the deadly destructive drives, ad infinitum. In this madness, time is jerked off, and I remain unable to feel bliss or delight. My life is sentenced into a body whose locus of enjoyment is obedience and submission before an oppressor who acts as if it knows how to do it right—and yet, closed to the possibilities of love, the opened doors (and legs) of the heart’s reasons.

While fulfilling this judgement imposed by myself, I also struggled to elaborate such martyrdom. The psychoanalytical work I chose to bet was uncertain (like any other bet) and desirous to articulate my letting go of the judge’s hand (the same one that held me, and also my damn origin), hoping to rebirth (or remember) an internal law, which, suddenly and to my unexpected surprise, resurfaces when my life is at risk. Before a cancer diagnosis on the base of my tongue (yes, my tongue), I undergo two surgeries, one urgent, to remove a tumour there-lodged. Such intervention is done by a robot maneuvered by the hands of a surgeon who operates the machine. It is this strange metal being that penetrates my mouth and slits my tongue, cutting the organ in its real materiality, separating its deadly becoming from what announces life.

It is only months later, when receiving the pathology results, that I will hear: the reports indicate that the tongue showed a negative, or, in medical terms, more flesh was extracted than it was needed. Or, said in my own terms, the extricated rest of this tongue represented the unspoken words the once upon a time baby couldn’t vocalize or reach. But I am moving too fast here. I first need to explain that the second intervention I underwent was caused by an unexpected bleeding during the night while I was still hospitalized, and that filled my mouth, and my body, with an excess of blood, an absurd quantity of origin.

It was at that instant, I can assert, that I understood for the first time the primary sense of the law: a deter mination that requests the separation of bodies so that they can live conscious and aware of life and death’s limits and cycles despite the illusion of filiation and eternal repetition, many times unconscious in parents, but often manifested in their descendants, successively. Then and there, I also understood it was time to let go of the judge outside my body and listen to the interior voice inhabiting me, which so much desired but exceeded in blood, in lineage, and yet, still, in a magistral manner (as one of the doctors on

call would later say), was capable of swallowing (unconsciously, under the effect of a general anesthesia) the clot over my vocal cords, and, like so, sacrifice the blood, the origin, and liberate the breathing, easing the tessiture of the cut.

I also have lear ned that only a small percentage of the cases (20%) in this kind of operation can cause unexpected bleedings, especially due to the quantity of nerves located in the region where the tumour was removed—not to mention the placement of several major arteries, one connecting our breathing directly to the beating of our hearts. For me, the interesting aspect of all this is that, despite science having the reputation of universal and endless in search of definitive answers, the doctors, in this situation, and to my luck, the majority who attended me, gave the final authority of knowing to my body, the expert in the success of this traversal.

To the point of me listening, almost like a whisper, while waking up in convalescence in the emergency area after the second surgery extremely fragile, tired (as though I had given birth to my own being and void) after losing so much blood, the doctor’s insistence and reassurance that I had pulled out of this because my body knew exactly what it was doing at the moment of the crisis, prosperously allowing the effective action of the team.

Before death, life, which edges but in a second. And the atemporal consciousness of a knowing (not knowing) anterior to words and which govern the law and the pulsation of life, but also of death. And still, why say something before all this? In order to understand how the trust in what one doesn’t know it knows determines the law of those who choose to live, continuously acting over our bodies with limits and answers, many times impossible to be articulated but still valid with the same science.

It was up to me, and my desire, to unveil this disruptive and destructive plot, recreating a new way out for this mad infant (this infant on fire). But I didn’t do this alone. I worked for several years and still remain, to elaborate the frontiers of the unsayable through the labour of psychanalysis. Without another person occupying the position of a listener, this task would have been impossible, for any link can only be established between one and another. Whilst the dialect of the judge, inverse to the one which connects us in love, is perversely mortal and judgmental: a dictatorship that kills the “I” in the name of another enjoyment, and whose suffering can reach unimaginable levels in its best and worst versions of the law and its limits.

By appropriating the demarcation between life and death, and in a certain way, opting to rebirth in this castrated body, cut from the ideal of original fusion, I validated the unheard emotions of a baby which, in former times, came to the world madly.

These memories, I know, are full of failures, and yet important to be said, so they can fully act on my skin. It is in this tessiture, also, where holes are found, the mad desires without sense in their sudden disappearances. On my rights of being mad: so that, from the return to the mythical maternal origin of Juiz de Fora (Outside Judge), the same mortifications may be possible to create a new dance, a novelty, where I, gone in the erotica of passionate, interlaced loving bodies, can be lost in the other, but refound in myself, depositary of traces melted in the flesh; a heritage of eternal self-rewriting, affectated by the silver gloss of the moon over our transitory, dazzled beings gulped by the pulsations, unrestricted and contingent, and recipient of frequencies and meanings, to be rediscovered, the unhindered pleasures out of the temporary residences of words.

Considering that facts are nothing but versions, nothing but nothings reordered, it is like so that I retell my small little story. The summary of a rebirth, of a traumatic repetition, of life and death intermingled. The tale of a young girl who was born and became gravely sick after labor. Who experienced recurring transit accidents that almost took her life; a sequence of psychotic breaks, an exacerbated dread of the law and a crazy desire to be body and transience. From a normal delivery goes the legend, I was put in incubation for a few days with a very high fever, until, as soon as arriving home, I developed an intestinal infection due to a hospital contamination. What does this baby want? I can still hear the echoes around me. Why doesn’t she get better? Eventually, with an excess of food, affection, and prayer, the child decides to submit to the condition of living outside of her mother’s body (be it for her desire or mine, I don’t know).

It took me a long time to completely understand this. I was also late to comprehend how my so-called independence, which made me capable of creating a life in another country, foreign, and living alone without anyone else (or the fact I never married or had children) are part of the contingencies, but also of an unconscious desire for separation and alienation present in me. Whether this may be a traumatic repetition of what my parents desired and couldn’t realize or a residue of so many other similar principles, life was realized as it could. Certainly plenty has changed today, greatly due to the psychoanalytical work,

moreover, evidently, due to my own spirit, triggered by the mysteries of everything that is most occult and taboo in my soul—for even if I resisted, my life experiences would have inevitably forced me to face each one of my shadows. For this reason, and something more, I no longer feel alienated, much less separated, from the collective or society—the result of an exhaustive and determined work, arduously conquered, obviously with its contingent limitations.

The demand of an idealized return home, a purity of origins, exerted a devastating power over me, and for a long time acted as a destructive ghost, eliminating any possibility of restoration, thus reflecting its incomprehensive invisibility and narrative veracity. In other words: I believed more in the ghost than in my capacity to recreate a new story. That is, until now. Today I can understand how this unconscious desire for lineage, and the demand for sameness, traversed a series of unconscious generations prior to mine. A collective of men and women inattentive to the savoir of a heart which pumps much more than blood. Without mentioning that, despite it all, I still don’t carry definitive answers (auspiciously), only the courage to ask the questions. For they are the ones which, somehow, indicate the path to my truth and singularity, partial and imperfect, an effect of that which is most unknown in me, but also in my ancestors, that if once desired my life, also condemned me to death. In the beginning, in my view, only love and desire (ours and of those who surround us) should remain, so that this trivial cell may expand and win over death, exhausting the thread towards the inorganic (travestied in origin)—while it may be possible.

An intervention, a second time, which, in the case of the medical act, occurs exactly at the moment when the official daylight savings in Canada (from summer to fall) fell back, and the clocks were changed, in an in-between characteristic of the atemporality intermittent in the unconscious, which repeats without any reference to the chronological time, reinscribing itself in difference. A cut beyond the umbilical, in the living real flesh of my body, on the base of my tongue, the one I received from the other, and that, until then, I couldn’t say for sure it was really mine, officialising a new time, an uncertainty, another logic, over my body (an operation without a definitive time, according to the medical reports).

This, and many other stories, are part of my kaleidoscope of experiences: my effort to articulate my rights on being mad, which I attempt to sketch here. For everything that derives from memory and writes me seems to walk in circles, speaking about one thing and saying

something else, so to speak. Like the recurrent dreams of being lost and unable to find my way back home. Like a baby, mad when being taken apart from her mother, the source of her unconditional love. Like the experience of a meditation, which delivers me a vision, and a dream (because I fall asleep): when, searching for my mother, I, still a child, find her lying down in a leaked bathroom, unconscious, maybe dead, the faucet running water. Such is the fright that I panic without knowing what to think or do. Instead, I act by intuition and impulse in a knowledge that doesn’t know (but knows) what it is doing. The child I once was carries the body of her mother to the hallway (who knows how) and lies her ear against her mother’s chest: she (I) wants to hear her heart, to make sure the mother is still alive.

It is at that moment that I hear a sudden expansion coming from my mother’s core, while, at the same time, feel her heart inflate—full, unmeasured, and uncontrollable—in my direction. What I see and sense is her heart amplified with such intensity until funding and entering into mine, expanding myself to such a lengthening that I wake up. Open my eyes. My emotion is so intense that I am slow to understand what has just happened. Little by little, still disoriented with what has passed, I breathe deeply and feel my heart again, the same as my mother’s, now fully alive in mine.

Lying in bed, it starts to dawn on me the memory, the remembrance, of deciding to meditate after arriving home tired after a session of radiotherapy. I remember also that my mother has passed away more than seven years ago, that the bathroom featured in the dream existed once in the past, and that this recollection is partially true in the content of its images, but fully unreal in the veracity of the ensued facts. I also recognize that there are many things I misrecognize when outside the temporality of conscious feeling. During the measure of an instant, or a bit more, I remain in state of pause, slowly to reinhabit my body. Until, suddenly, and from a distant, yet close place, I hear in the background (and strangely outside of me), the uninterrupted crying of a baby who thinks she has killed her mother by being born separated from her. It is then, also, when I understand, a bit unreasonably but fully lucid, that this crying, this desperate baby, is myself lost in some place in the past locked inside of me and that, until now, hadn’t been heard. Thus, with the patience and loving care of a mother, I listen her lament, her sorrow, and explain carefully (also to myself) that she has not killed anyone, and that her mother will live forever, now in peace inside her heart.

It is from this love where all things are born, I say, and I listen.

And it is like so, from a simple, almost accidental, guided meditation, with the intuit of changing my astral frequency, that I reencounter the second moment of the law founded in the love of this mother, now internalized and reawakened inside of me, sometime later. With open eyes, and still alarmed by the truthfulness of the experience outside the linear memory timeline, I regain what I had forgotten: the identification I have with my mother is with her heart. In this riddle of resignification, I also realize the impossibility of separating myself from a quality of enjoyment and pleasure that characterize me despite my fear and even horror. My fusional comings and goings with bodies, images, and perceptions: my way of perceiving others’ traverses and sources infinite possibilities and knowings, not often rational or well regarded with the laws of the mind.

In my body, one is not just one but plenty of others, what complicates my lear ning in a world where (historically) each thing must be one and same, and woe betide anyone who questions why the sea is not shell, moon, or whisper, or all together, for it always comes the time of reason, of coming back to oneself, aware of science and the limit of each word and thing. If what partially characterizes my desire is to love intrinsically, madly passionately and with expansive fusion, it is precisely there where I best live, especially when this way of being no longer condemns me to the death row. Knowing how to fuse is also knowing how to separate and sustain the lack in its most profound and constitutive expression, essential to the creation of life (or death), depending on what you desire. From the impossible of being articulated, the castration of the tongue, the reappearance of a mother’s love is reborn inside of me, the origins of my affection, of my way of loving and desiring, and from where grows the laws of life. The error in calculus occurs in the equivoque of thinking that the heart lies inside one’s tongue and what can be explained with words, while what pulses on the skin is exogenous in speech, times over madly and desirous, whether for being unspoken, unconscious or impossible to be said.

Indirectly I can risk saying that it was through the process, and the symptoms, of radiotherapy I underwent later—six weeks of daily applications of lethal strong rays over the region affected

by the tumour (the right side of my neck)—when I learned something about the process of elaborating anterior marks not previously recognized and which, in a certain manner, were repeated and re-actualized: the intense burns left on my skin. The heated fever kept inside me. The lack of taste in my tongue, the distasteful taste of savours and savoirs. From the base of my tongue, now castrated and conscious of its rational limitations, and everything that is impossible to be said. From the body that once feared lacking words and now lives in the irrational love unraveling the supremacy of reason, defying death like a temporary breeze, a spiral disorientation of knowledges and altering consciousness, trustful in the greatest worth I inherited: life, while it endures, with its mixtures of oceans, colours and airs, far and close from home, present beyond the mad repetitions of a crazy infant, transgressed with the intersection of a motherly love, the law of a desire to re-signify the gift, returning to the same place but differently, madly passionate and familiar in the alterity of the time of arrival, in the other which comes a posteriori. So that the desire to love may be lived in its plenitude, now free from the need of a time or exact place.

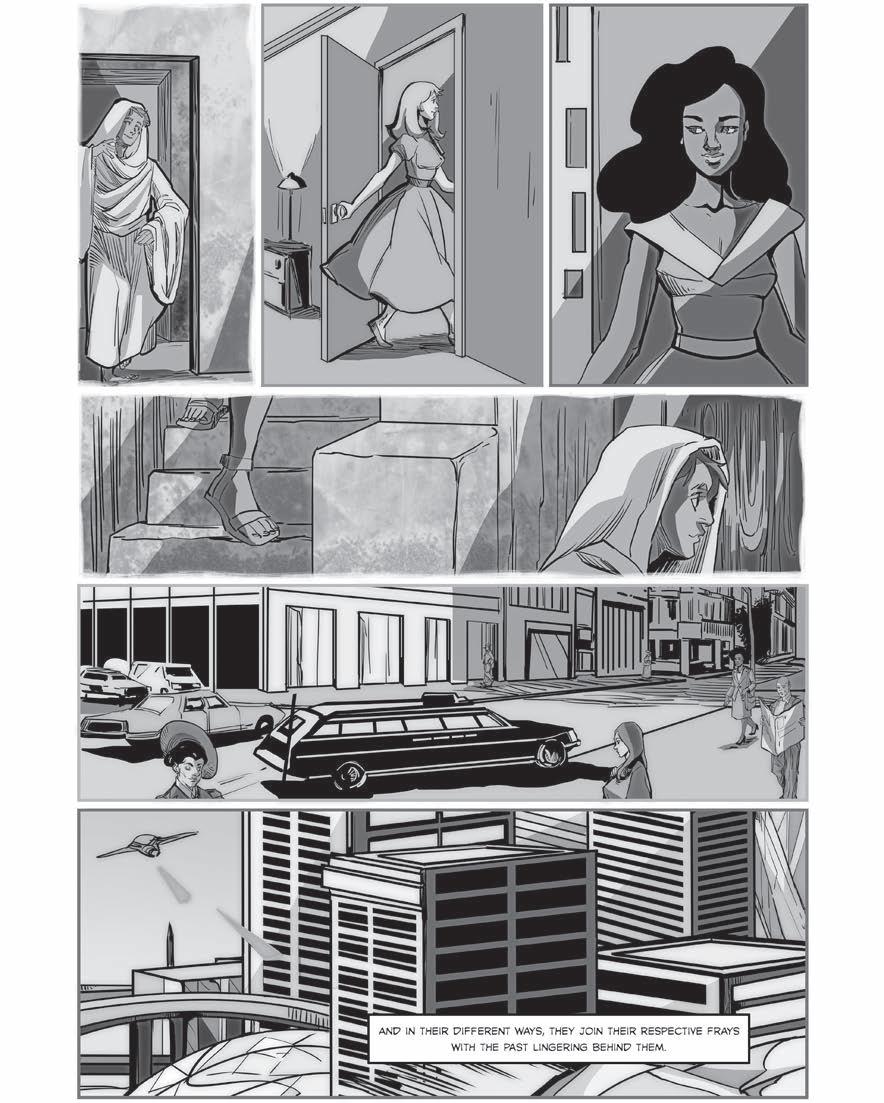

PATRICK McEVOY and ANDREA MONTANO | AN ARTIST’S STATEMENT

Acted out onstage. Illustrated onto a page. Words becoming sentences becoming paragraphs becoming stories. Visuals taking shape within a certain frame. No matter the context, there is an idea there, a thought, possibly a story to be brought up from within. Put out into reality to make someone think, feel. And whether short or long, story or picture, hopefully it resonates in some way with the viewer. With a strong affinity for genre fiction and surreal art, there is possible truth in all forms.

EVOY

PATRICK

INTERVIEW | Santa Fe Literary Review Speaks with Deborah Jackson Taffa

Deborah Jackson Taffa, a citizen of the Quechan (Yuma) Nation and Laguna Pueblo, is the celebrated author of Whiskey Tender: A Memoir, which earned critical acclaim as a 2024 National Book Award Finalist and was named one of The Atlantic's Top 10 Books of the Year. Recognized by The New Yorker, Time Magazine, and NPR, Whiskey Tender also made notable lists in Elle, Esquire, and Publisher's Weekly. Whiskey Tender was also longlisted for the 2025 Carnegie Medal for Excellence in Nonfiction. Taffa has received awards and grants from the National Endowment for the Arts, PEN America, MacDowell, and Tin House, among others.

With an M.F.A. in Creative Writing from the University of Iowa, Deborah Taffa has taught writing at Webster University and Washington University in Saint Louis and now directs the Creative Writing program at the Institute of American Indian Arts (IAIA). Her writing has appeared in The Rumpus, Boston Review, Salon, and Prairie Schooner, and has been anthologized in The Best of Brevity and The Best American Nonrequired Reading. Her play, Parents Weekend, was performed at the Autry Theater in Los Angeles.

Santa Fe Literary Review: To begin, we’d love to hear about your creative process. What does your practice look like, and how do you feel it has evolved over time? And more specifically: how would you describe the process and experience of writing your memoir, Whiskey Tender?

Deborah Jackson Taffa: My practice has become a lifestyle over the past 25 years. Despite publishing my memoir later in life, I resolved to write in my early twenties, but I felt that travel and healing would be important to my development. My family’s place in American history meant that I’d inherited a great deal of pain and confusion. It took many years of hard work—building a marriage, family, and business—to gain critical distance from my upbringing. I followed my intuition and opted to do it backwards, delaying my degree until I had some real-life success under my belt. I surmised at an early age that the callowness of youth might not allow me to write with sensitivity, and that writing could become a desperate act if it was linked too early with survival needs. In other words, I opted to give my voice a chance to develop and turned down at least one offer to publish the book before finally selling it to HarperCollins.

SFLR: Whiskey Tender recounts memories from your deep past—and uncovers difficult truths about your culture and your own family. What does it mean as a writer to expose these parts of yourself?

DJT: I initially resisted writing exclusively about my youth, but this led me to ask myself why I was ashamed of my childhood when it served as an indictment of governmental greed. I remembered the words of Zora Neale Hurston: “If you are silent about your pain, they’ll kill you and say you enjoyed it.” I decided to give my childhood stories a try.

SFLR: How do you navigate the vulnerability of sharing your story—and of writing about others in your life?