VICTORIA CROWE Decades

VICTORIA CROWE AT 80

VICTORIA CROWE AT 80

Decades marks a major moment in the career of Victoria Crowe, one of the most respected and distinctive voices in Scottish art, as she celebrates her 80th year. This Festival, we honour an extraordinary artistic journey and present a collection of new and recent paintings alongside selected earlier works from the 1960s to the 2010s, tracing the evolution and enduring resonance of her practice. Decades offers a reflective and forward-looking view of Crowe’s practice that has remained both consistent in its vision and responsive to the changing world.

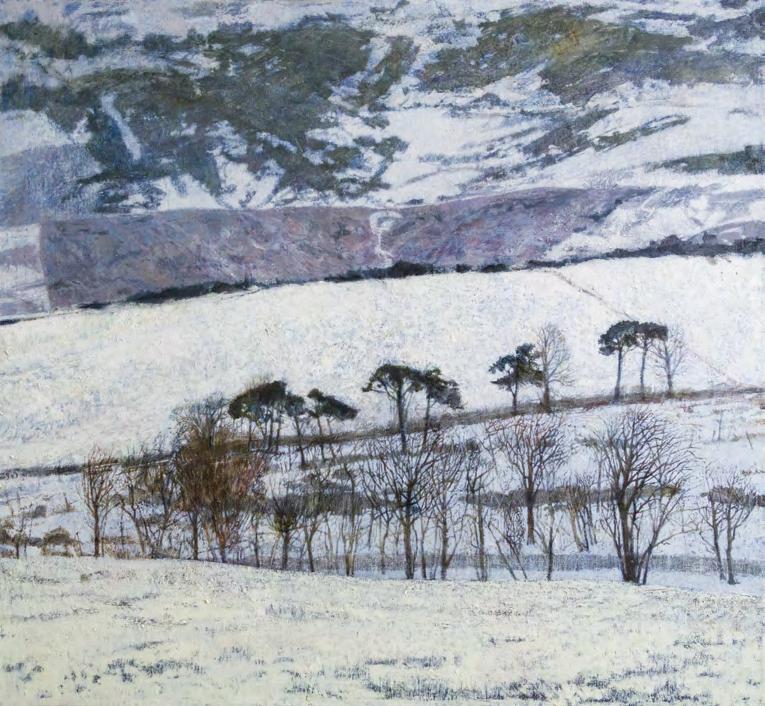

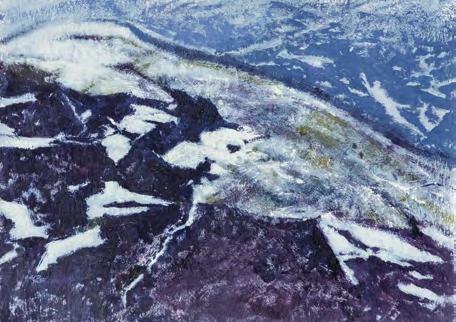

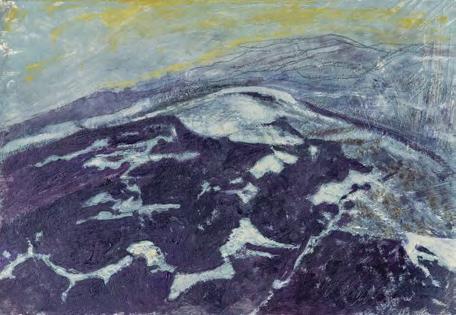

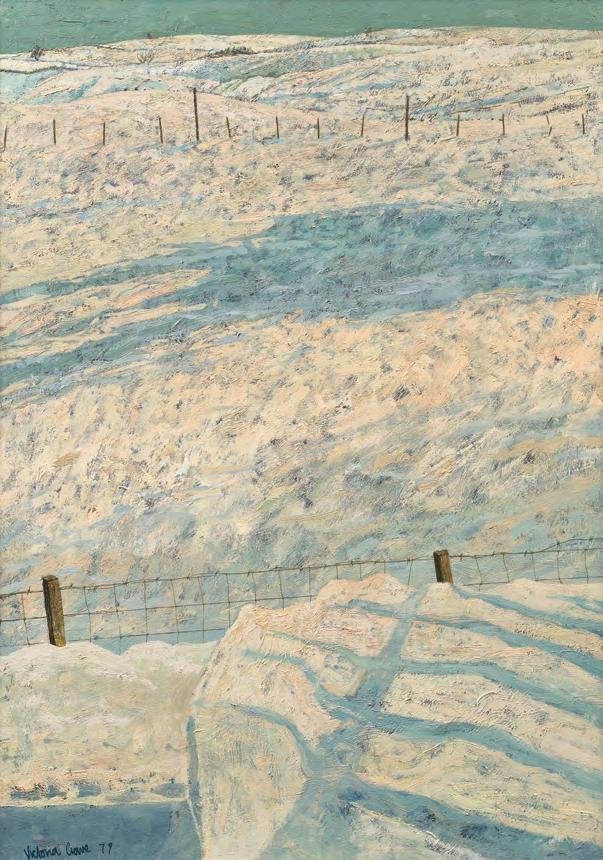

Decades is rooted in continuity: not just in theme and visual language, but in place. The Pentland Hills remain a source of creative renewal. Early encounters with the Scottish landscape, its winter stillness, abstract patterns of snow and heather, and the physical immediacy of being present within it, left a lasting impression. Crowe has returned to these familiar hills, not as a nostalgic revisitation, but as meditations on the passage of time and the evolving self.

Across six decades, Crowe’s landscapes have never been mere topographies. They are deeply felt spaces, infused with memory, metaphor, and presence. Whether in the solitary figure of shepherd Jenny Armstrong at Kittleyknowe, the shifting twilight of Venice, or the elemental horizons of Orkney, Crowe’s works speak to a poetic sensibility, an awareness of life’s ephemerality, permanence, and mystery. Change is held in delicate balance.

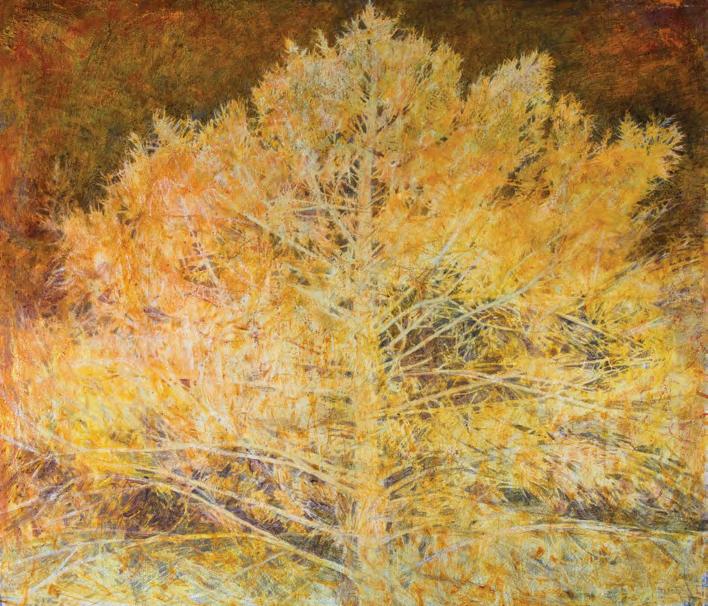

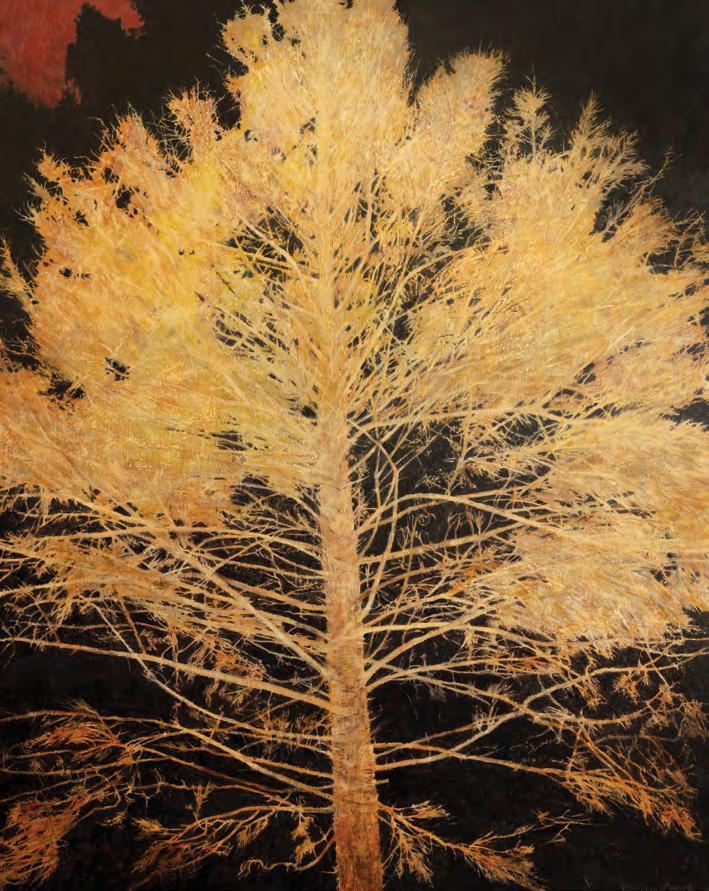

A parallel exhibition, Shifting Surfaces, at Dovecot Studios, celebrates Crowe’s longstanding collaboration with the tapestry studio, beginning in 2007. Tapestry, with its scale and material presence, offers new life to Crowe’s imagery, rich with symbolic colour and intricate mark-making. Landmark commissions such as the Large Tree Group which is held in the public collection of the National Museum of Scotland and The Leathersellers’ Tapestry in London, demonstrate how her work translates across media, retaining its lyrical depth and emotional clarity.

Decades is a testament to creative vitality. It reaffirms Victoria Crowe’s place as an artist of rare insight and vision, whose work continues to evolve while remaining grounded in an unwavering sense of purpose. We are grateful to Victoria Crowe for sharing her reflections, and to Julie Lawson, whose thought-provoking text throughout this publication offers further insight into a truly remarkable artistic journey.

Christina Jansen | The Scottish Gallery

Victoria Crowe in her Edinburgh studio, 2025. Photograph by Kenneth Gray

DECADES

Decades is a celebratory exhibition marking my 80th year, hosted by The Scottish Gallery, who have supported me since I arrived in Scotland as a young artist to begin teaching at Edinburgh College of Art in the late 1960s. The idea behind Decades has been to present a major body of new and recent work, while also reflecting on the continuity of ideas from the very beginning. I began by looking back at some of the earliest work I made in Scotland. In a small, battered sketchbook from 1968, there are drawings of the Pentland Hills in winter – patchy patterns of thaw and ice, with textured dots and strips of gorse or rushes breaking through the snow. I had never seen landscape like that before, expressed purely in terms of abstract values.

Of course, being physically present in that landscape brought an added intensity to the image. I remember that first winter, waiting for the early bus to Edinburgh, standing in the snow by the roadside, my breath looming out into the still, frosty air. I could feel the cold and take in the vastness of the snow-covered hills, and above them, the moon – still visible in the early morning light. That vivid visual memory, that sensory event, has stayed with me ever since.

I thought it would be interesting to revisit the Pentlands and to work again from the same areas along the A702 where I began more than fifty years ago. The sequence of small works on

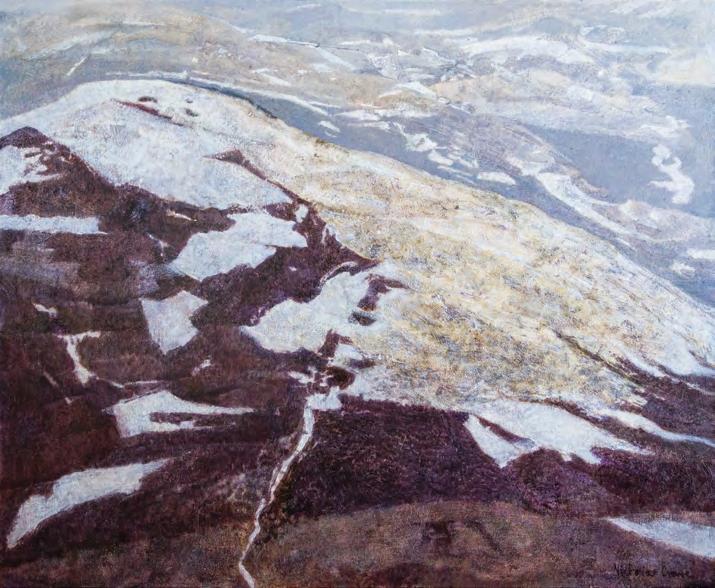

paper, made in the hills between Marchwell and Silverburn, marked the beginnings of my new Pentland paintings. The hills, scorched with burnt heather, created a dramatic contrast with the scattered patches of lying snow. The most recent of these winter hillsides – Higher Reaches (cat. 14) – particularly echo, for me, the importance of being present in the landscape, of feeling part of it rather than merely observing.

Higher Reaches (cat. 14) began as a drawing of a high stretch of land covered in snow shadows, but it developed into a painting about the sensation of almost walking up the surface of the nearest slopes. I don’t do that as often now, but I still carry vivid memories of watching the ground as I walked – the texture of packed snow, stony bits, ice, and rushes underfoot. Earlier this January, while drawing in the Pentlands in deep snow and bright sun, I experienced a kind of vertigo in response to the vast, snow-covered expanse. That sense of disorientation is something I’ve tried to carry into the final painting.

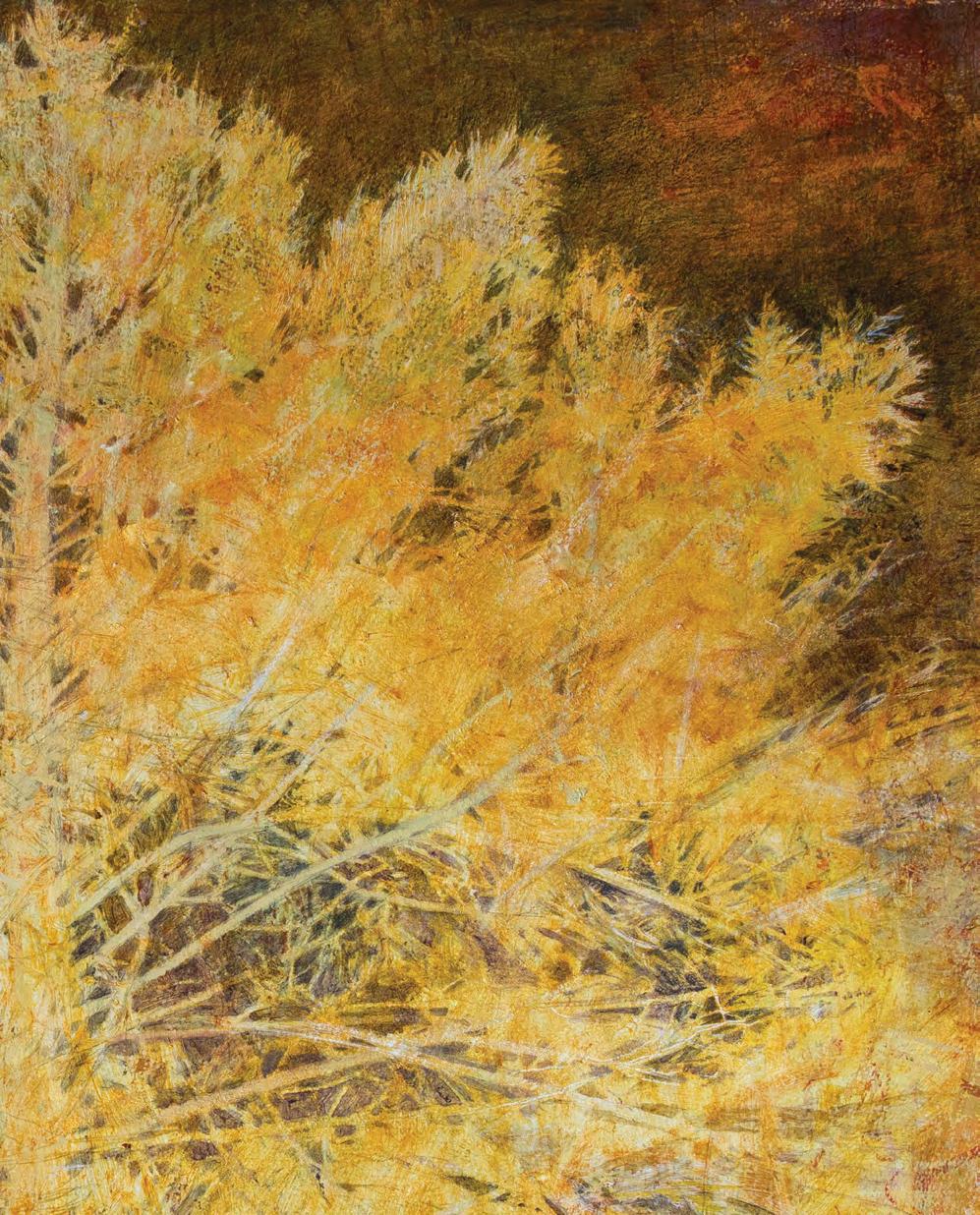

The emphasis of my work has inevitably shifted and evolved over the years, and some recent paintings have become more focused on the metaphysical aspects of landscape. In the Forest of the Night (cat. 20) contains a poetic connection to a world that is burning or destroyed, and yet the imagery carries a

kind of transcendence. While these works have an ecological dimension, a simple and enduring starting point for me is the church of San Francesco in Arezzo. During my sabbatical in 1992, I saw a tree in Piero della Francesca’s mural where the green pigment had flaked away, leaving behind a pale, plaster-coloured ghost. That image has remained with me – strange, haunting, and persistent.

The Orkney paintings began in 2022 during The Pier Arts residency with the Royal Scottish Academy, which sparked many ideas I’m still exploring. When I arrived in Birsay, I heard skylarks, curlew, lapwings, and oystercatchers –birds whose calls once echoed across the skies at Kittleyknowe, where we used to live, but which have grown rarer in the years since. Once again, a strong sense of place drew me in, and I found myself working in Orkney, where the subject matter distilled itself down to sky, horizon, sea, and land.

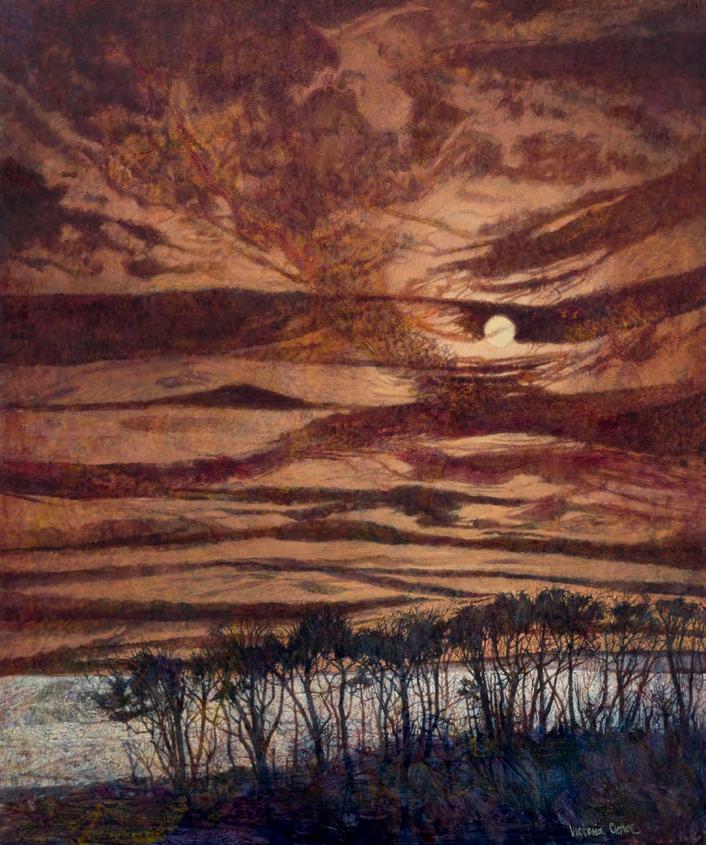

The winter phase of the residency brought brilliant moons and skies that lit up the long darkness, and I’ve recently been working on a series of paintings reflecting on those nights –the kind George Mackay Brown writes about so beautifully.

Victoria Crowe

‘Thermometer and barometer measure our seasons capriciously; the Orkney year should be seen rather as a stark drama of light and darkness. In June and July, at midnight, the north is always red; the sun is just under the horizon; dawn mingles its fires with sunset. In midwinter the sun intrudes for only a few hours into the great darkness, but the January nights are magnificent – star-hung skies, the slow heavy swirling silk of the aurora borealis, the moon in a hundred waters: a silver plate, a broken honeycomb, a cluster of fireflies.’

George Mackay Brown

An Orkney Tapestry, 1969

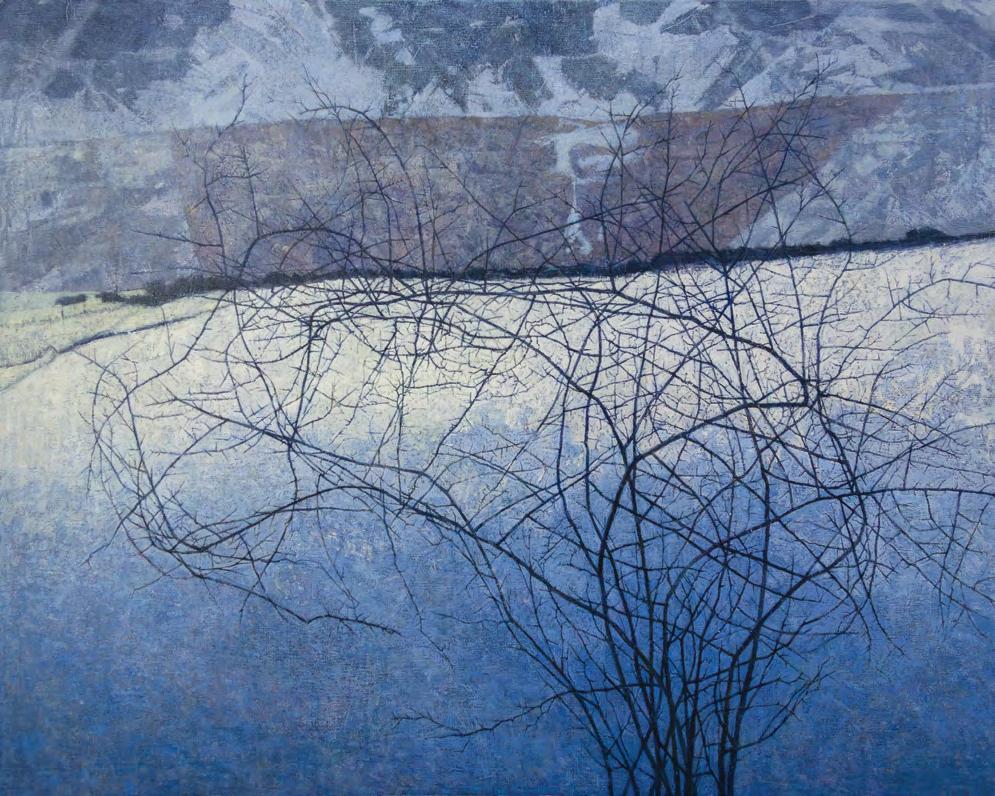

1 | Tactile Traces, 2024 oil on linen, 89 x 102 cm

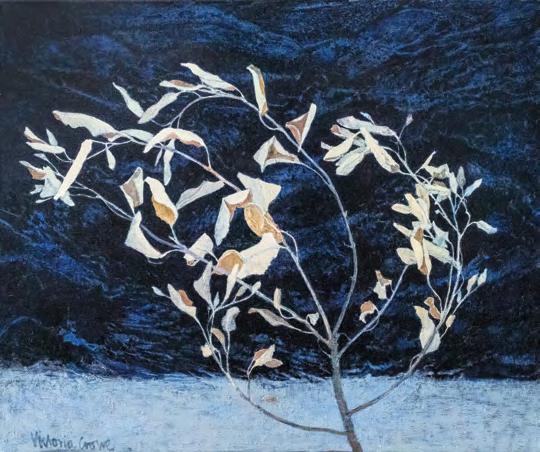

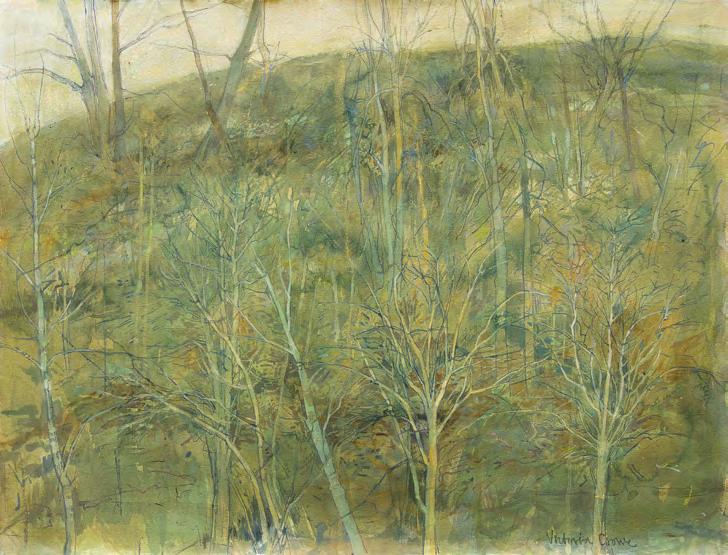

2 | Articulate in Winter, 2025 oil on linen, 101 x 127 cm

3 | The Silence of Winter, 2025 oil on linen, 76 x 82 cm

4 | Snow Melt, 2024 oil on linen, 127 x 114 cm

5 | Pentland Thaw, 2025

ink and acrylic on paper, 23 x 26 cm

6 | Last Snow, 2025

ink and watercolour on paper, 48 x 53 cm

7 | Gate and Thaw, 2025 oil on primed paper, 13 x 18 cm

8 | Side of the Hill, 2025 oil on primed paper, 10.5 x 18 cm

9 | Thaw, Traces, Distance, 2025 oil on linen, 72 x 86 cm

10 | Burnt Heather Hill, 2025 oil on primed paper, 15 x 21 cm

11 | Behind the Crest, 2025 oil on primed paper, 15 x 21 cm

12 | South Black Hill, Silverburn, 2025 oil on primed paper, 15 x 21 cm

13 | Black Hill and Distant Slopes, 2025 oil on primed paper, 14.5 x 21 cm

LANDSCAPE

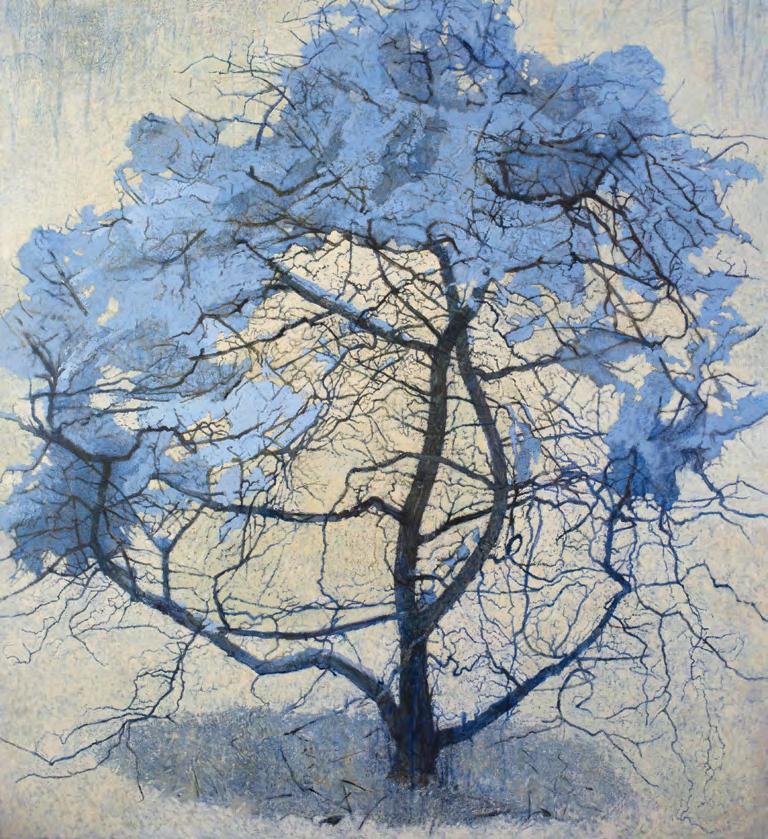

It may seem surprising to learn that Crowe, in her student years, had wanted to be an Abstract painter – in emulation of the artists Malevich and Rothko that she most admired. Less surprising perhaps when one considers that these great painters achieved a power to affect the viewers of their paintings through the contemplation of shape and colour, devoid of any narrative or representational elements – akin to the power of music to speak directly to our feelings. Our emotional responses are not derived from anything specific or concrete in their paintings whose aim is rather a distillation of feeling. They prompt states of mind, reflection, introspection and, for some, an access to another level of consciousness. In her still life paintings, Crowe has sought to convey the human emotions concealed behind seemingly ordinary everyday objects. In her landscape paintings too, with her preference for the leafless tree and snow-covered hill when what is familiar is transformed, broken up into geometric shapes and patches of light and dark tones, she is concerned less with what is ‘real’ than what is remembered or imagined.

Truth in art is different from imitation. As the nineteenth-century art critic John Ruskin wrote: ‘Imitation can only be of something material, but truth has reference to statements both of the the qualities of material things, and of emotions, impressions, and thoughts… There is a truth of impression as well as of form.’

(Modern Painters 1.24)

Crowe has said that her landscapes are not topographical. Her intention is not merely to hold a mirror up to Nature – though they are always based on drawings made before the motif and intense observation – but to express feeling. They are not meteorological – though she has made a study of the different cloud formations and observed land and sky in all seasons – but poetical. She seeks what Ruskin called ‘the higher truth of mental vision rather than that of physical fact’, with the aim of ‘producing in the far-away beholder’s mind precisely the impression which the reality would have produced, and putting his heart into the same state as it would have been had he beheld the same scene’. Ruskin was of course speaking about Turner, but his words are also applicable to Crowe.

Her most recent landscape was painted in the spirit of those Abstract painters she had admired as a student, but even here, however minimally, she provides visual clues that anchor it in reality. In Higher Reaches (cat. 14) we cannot identify with certainty whether the blue elements represent sky or water and are unsure as to what, if we are looking at a landscape, our viewing point is.

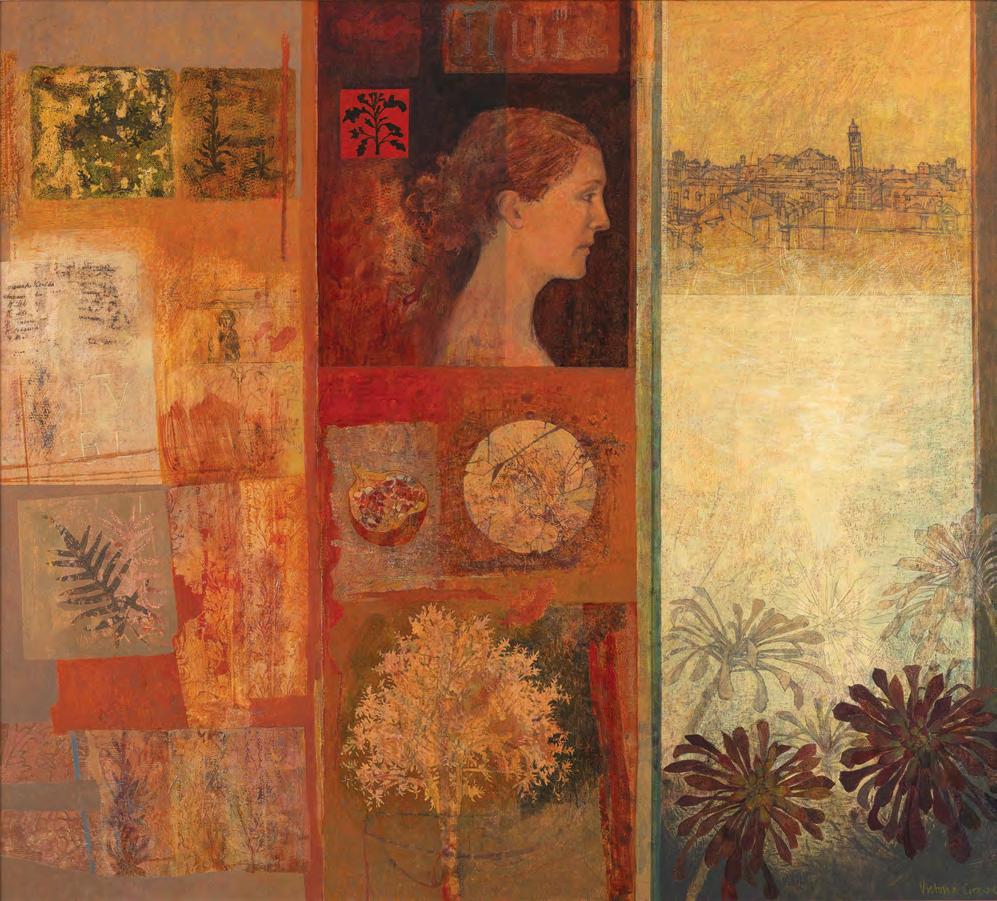

This latest painting is a reminder that there is, in the artist’s oeuvre, a continuity as well as a development and growth. Her early love of the icons of Andrei Rublev still informs her approach to painting. We see echoes of his work repeatedly: the compositional device of dividing up the picture surface with a series of vertical lines to create separate notional spaces; the distressing of the picture surface which, in the icons are the result of paint loss, abrasion and damage, serving to remind us of their survival over time and now part of their aesthetic; a preference for the creation of an independent pictorial reality rather than an illusion of depth and rational space, and above all, the aim to create, like Rublev, images concerned less with

the contingencies and changefulness of the material world and more with eternal verities and deeper realities.

Julie Lawson

14 | Higher Reaches, 2025 oil on linen, 127 x 127 cm

15 | Snow Line, 2025 oil on linen, 40.5 x 51 cm

16 | Lily Illuminated, 2022 oil on board, 101.5 x 81 cm

17 | Watching Winter Pass, 2025

watercolour on paper, 56 x 74 cm

18 | No Longer Able to Read the Signs, 2022 oil on linen, 91.5 x 76 cm

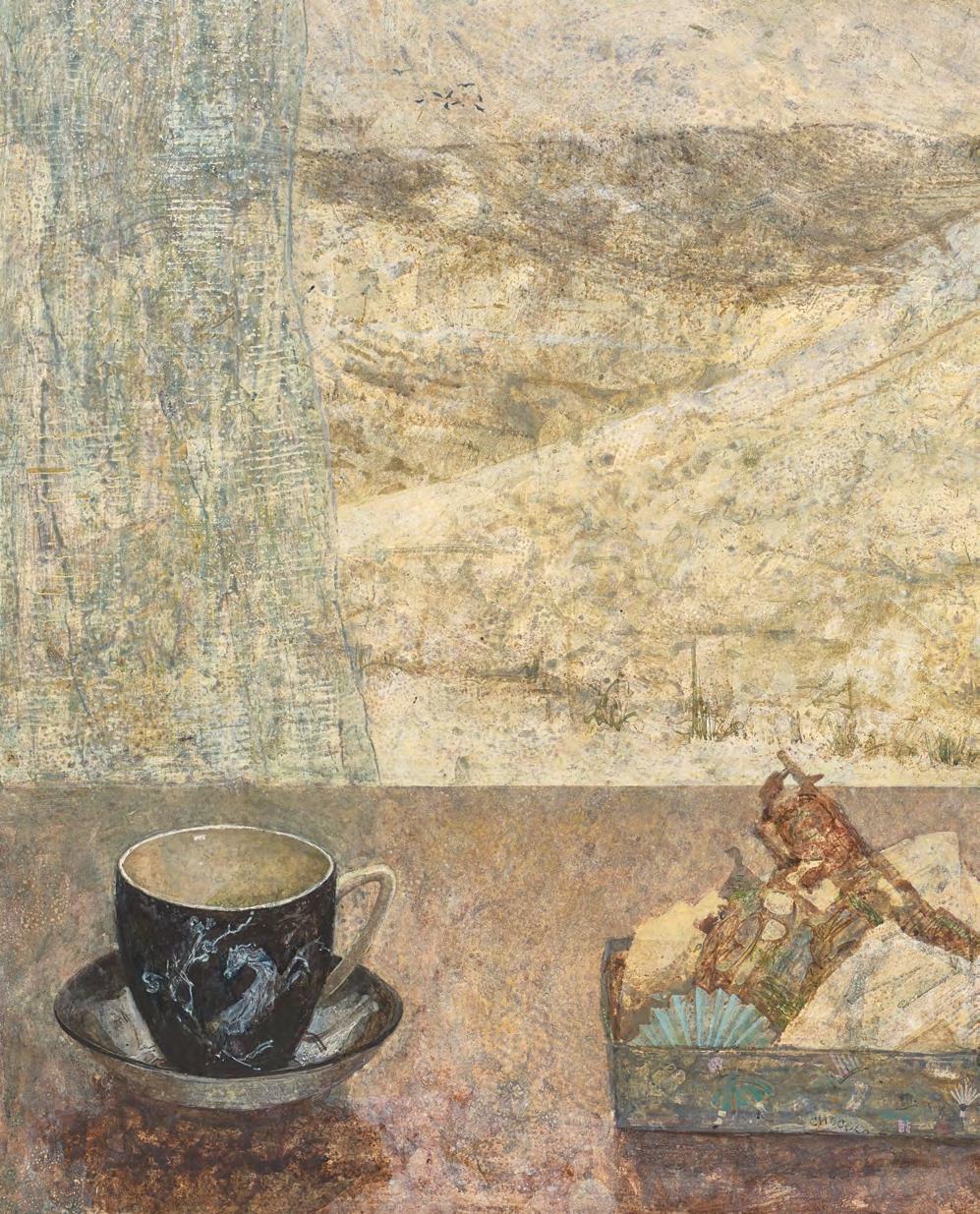

19 | Luminescence, 2025

mixed media on paper, 75.5 x 84 cm

20 | In the Forest of the Night, 2023–24 oil on linen, 100 x 80 cm

ORKNEY

‘I begin with acute observation. Then, imagination and association transform objective reality into a complex personal dialogue, evolving layers of meaning elaborated by persona; memories, set against the vastness of historical time.’

Victoria Crowe

The Orcadian poet George Mackay Brown describes the task of the poet as ‘the interrogation of silence’ (The Poet). This could equally apply to the task that Victoria Crowe set herself during her residency in Orkney in 2022. An enduring fascination for Crowe has been the mysterious and the enigmatic – things seen but not fully understood, apprehended but not comprehended: the intricate geometry of a bare tree, the entanglement of a complex plant form, or a landscape transformed by snowfall from the familiar to the strange – unrecognisable and uncanny. These are things on the edge of sight, in shadow, the crepuscular, the half-glimpsed, the fleeting. In the opening passage of Austerlitz by W G Sebald, he describes a visit to the Nocturama

in Antwerp Zoo, whose denizens have ‘strikingly large eyes, and the fixed, inquiring gaze found in certain painters and philosophers who seek to penetrate the darkness which surrounds us purely by means of looking and thinking.’

Sebald could have been describing Victoria Crowe. She has often described how, during a previous residency at Dumfries House, she would watch the changing light throughout the day, intrigued by how the landscape transformed in twilight. She would draw the landscape by day, when it was visible, and then walk through it by night to capture its moonlit essence in her mind’s eye, wondering how dark she could make her paintings, how she could convey the sense of mystery the night light conferred. One wonders if she knew, in some way, that she was emulating what the German Romantic painter Caspar David Friedrich did –walking at night through the forests of Germany for the same reason. She felt a strong affinity with Friedrich when she saw his exhibition in Berlin on the occasion of his bicentenary, describing the experience of looking at his work as a communion ‘soul to soul’.

Friedrich said, ‘A picture must not be invented, but felt, and the painter should paint not only what he has in front of him, but also what he sees inside himself.’ His paintings are often at the limit of understanding, and Crowe has frequently expressed a similar purpose. In the 1990s, she said: ‘The natural world, its patterns of growth and decay, the renewing cycle of the seasons, became a thing of mystery to me. I was drawn towards examining aspects of the eternal – the moon, the sea...’

So, in 2022, in Orkney, she was drawn to the same subject matter.

Unlike Friedrich, who often included figures in his paintings – usually with their backs turned to the viewer, acting as surrogates watching the moon or gazing out to sea – Crowe’s Orcadian landscapes and seascapes are unpopulated. In Shepherds Huts, War Bunker and Shining Sea (cat. 36), moonlight shines on the surface of the sea, casting silhouettes of a shepherd’s hut or a lookout pillbox – symbols of both peace and war, reminders of invasion, which have coexisted throughout the islands’ history. Perhaps they are symbols of survival, or perhaps they suggest

that the moon has shimmered on the sea for millennia before humans dwelt here and will continue to do so long after our disappearance.

At the heart of both Friedrich’s and Crowe’s work is a sense of mystery, an exploration of the limits of human vision and understanding.

Julie Lawson

21 | Occluded Sky and Headland, Orkney, 2023 oil on panel, 82 x 61 cm

22 | Threshold Between Sky and Sea, Known and Unknown, 2023 oil on

linen, 88 x 102 cm

23 | Fast Moving Cloud Above Still Land, 2024 oil on linen, 76 x 103 cm

24 | Winter Moon with Lights from the Land, 2024 oil on panel, 20 x 25 cm

25 | Above Hamnavoe, 2024

oil on panel, 20 x 25 cm

26 | Orcadian Series: Solstice Moon, 2023

gun-tufted rug, wool and canvas, 160 x 212 cm

tufted by Louise Trotter

Victoria Crowe has collaborated on several large-scale projects with Dovecot Studios and has a good understanding of how the weavers will interpret her starting points to reach an image of scale, richness and grandeur. A rug similar to and yet with a totally different quality from the original painted image. Dovecot Master Weaver Louise Trotter tufted the rug over several months.

27 | Orcadian Series: Above Stromness, 2023

gun-tufted rug, wool and canvas, 160 x 212 cm tufted by Louise Trotter

28 | Moon in a Hundred Waters, Harray, 2025 oil on linen, 81 x 76 cm

29 | Moon in a Hundred Waters, Stenness, 2025 oil on linen, 81 x 76 cm

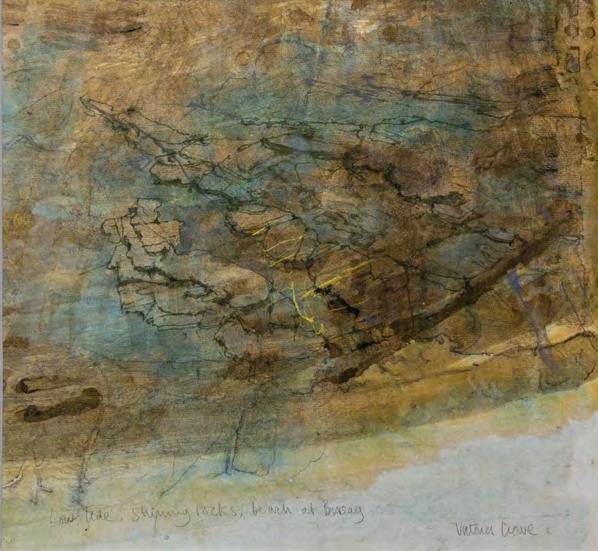

30 | Low Tide, Shining Rocks, Beach at Birsay, 2024

watercolour and ink on paper, 46 x 49 cm

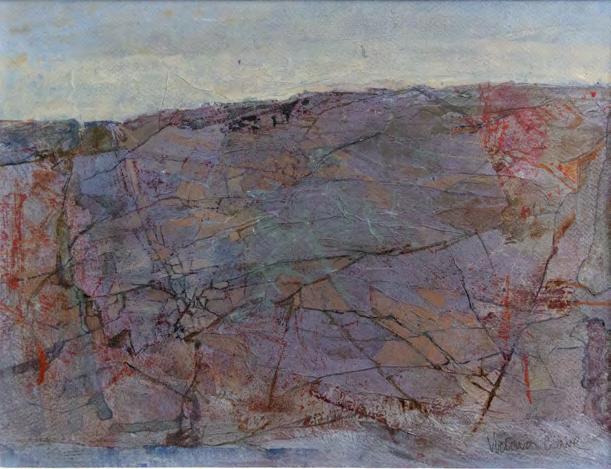

31 | Stone Pavement, Yesnaby, 2024

mixed media, 29 x 38 cm

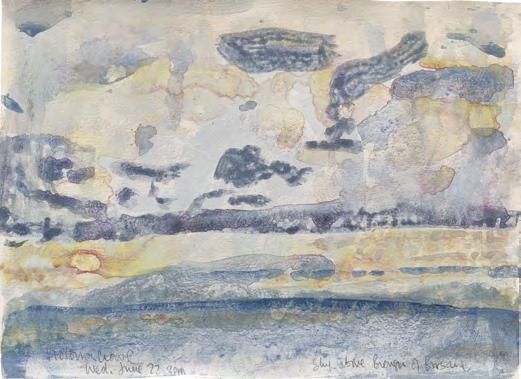

32 | Sky above Brough of Birsay, 2022

acrylic, 22 x 30 cm

33 | Brough and Sky Above, 2022

acrylic, 20 x 30 cm

34 | Shielded Sky, 2022 oil on linen, 20.5 x 24 cm

35 | Closed Sky, 2022

watercolour and ink on paper, 36 x 51 cm

36 | Shepherds Huts, War Bunker and Shining Sea, 2024 oil on linen, 101 x 127 cm

DECADES 1960s–2010s

DECADES 1960s–2010s

When the Scottish National Portrait Gallery was founded in the nineteenth century, it was concerned with ideas of heroism and the need for role models in society. In the year 2000, when it was incumbent upon the institution to mark the Millennium, it did so by signalling that in a new era there was a new understanding of what constitutes the heroic. It was the unsung heroism of everyday life that they chose to celebrate, in the exhibition of paintings by Victoria Crowe entitled A Shepherd’s Life.

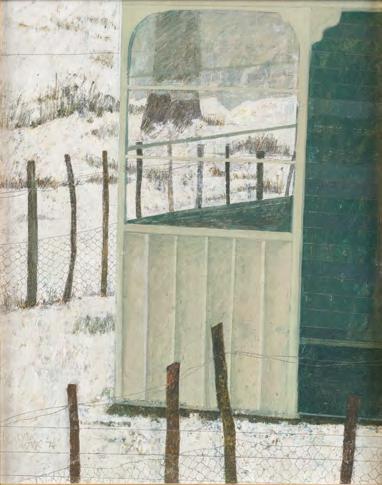

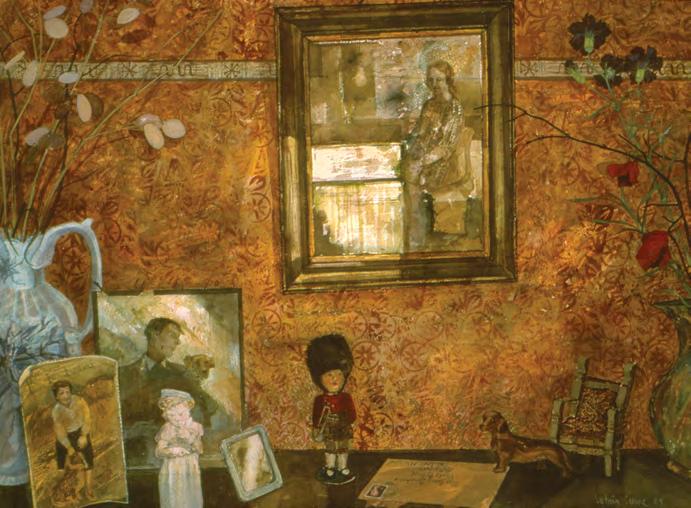

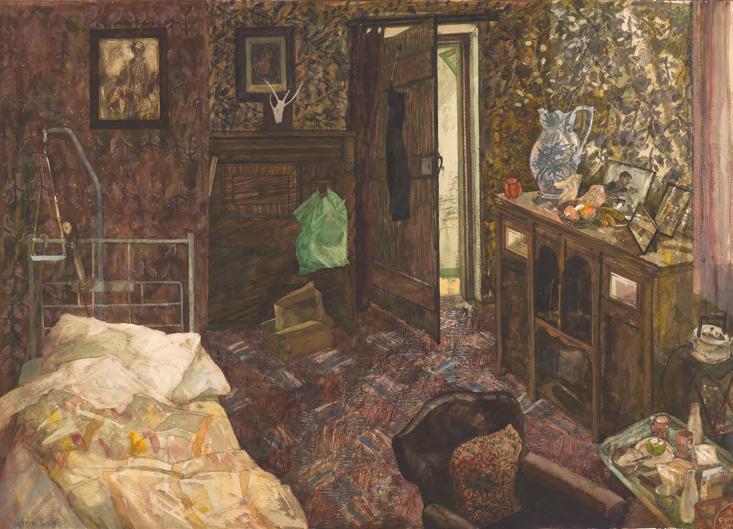

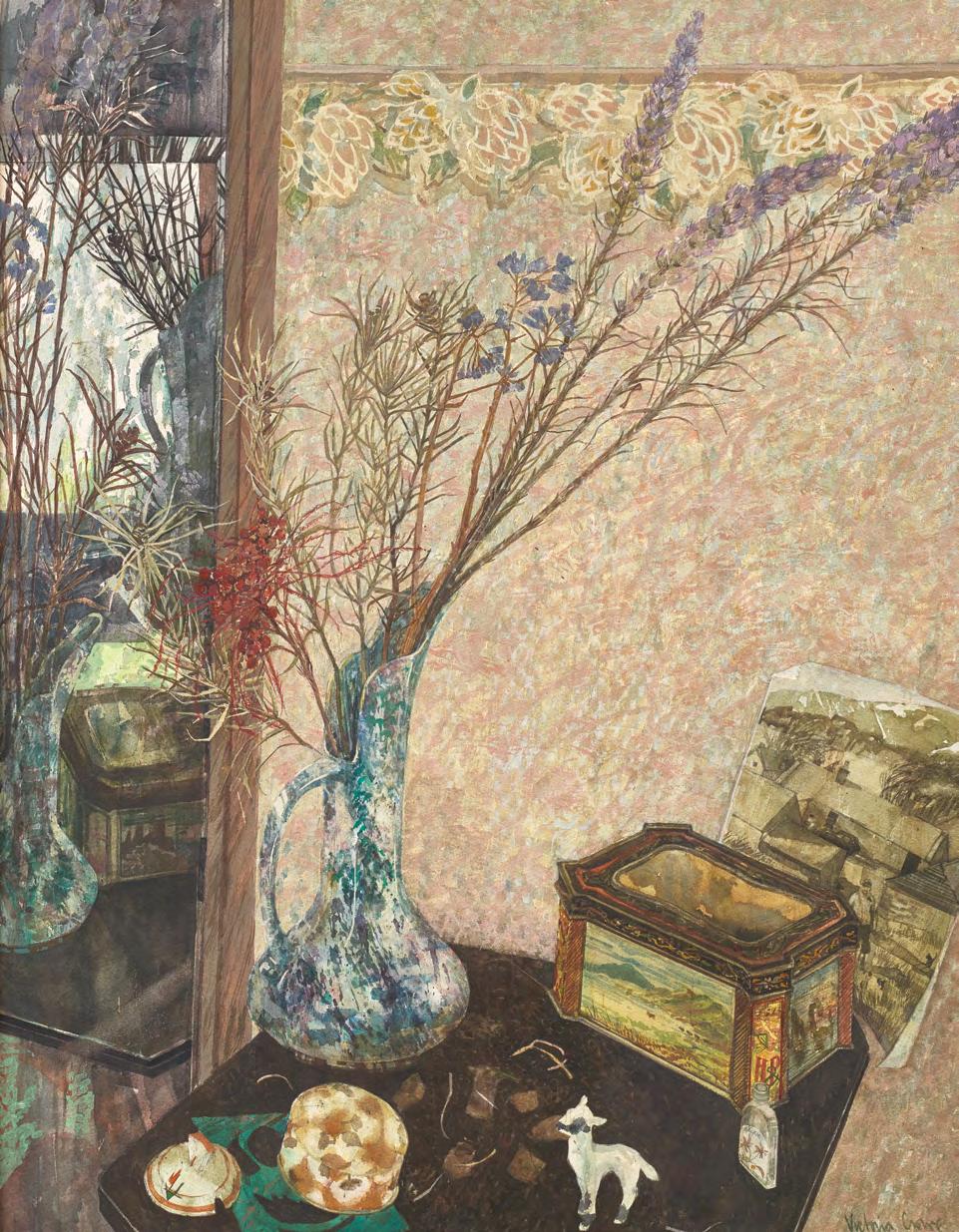

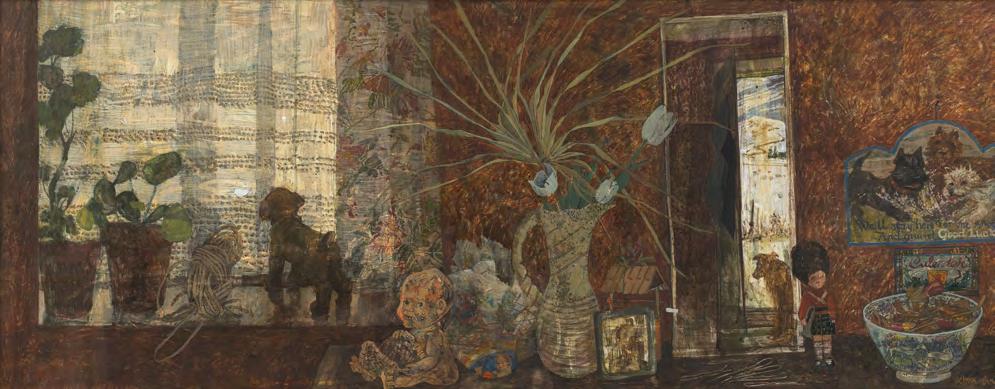

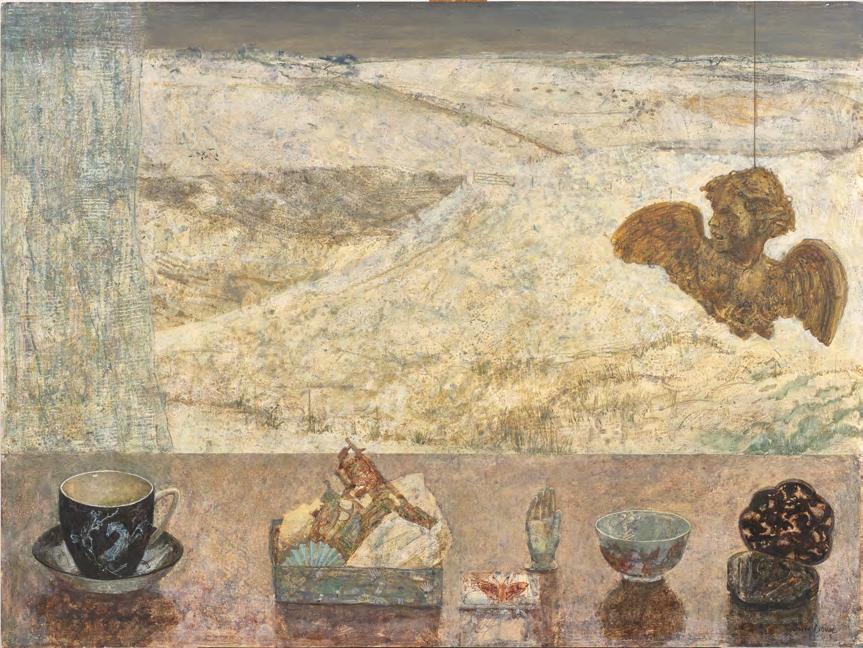

In 1970, Crowe came to live in the remote area of Kittleyknowe in the Pentland Hills, some sixteen miles south of Edinburgh. Over the next decade the landscape, its changing seasons and the way of life that had informed it, represented by the lone figure of a shepherd, provided the subject matter of her painting. The shepherd was Crowe’s neighbour, Jenny Armstrong. From 1980, for the last five years of Armstrong’s life which were spent increasingly indoors, the paintings became close observations of the interior of her cottage, the landscape now seen through a window or reflected in a mirror. After Armstrong’s death in 1985, Crowe made depictions of the empty cottage and a series of still lifes of the objects within it.

When these paintings from the 1970s and 80s were brought together for the exhibition in 2000, Crowe remarked that she had been surprised to see that while her subject matter, artistic concerns and style had developed and ostensibly undergone major changes over the intervening years – changes that had reflected and to a great extent been effected by momentous changes in her life and that of

her family – yet she could see that there was significant continuity in the work. The formative years spent at Kittleyknowe had been, she realised ‘an apprenticeship in a way of distilling the objective into the significantly personal’. In particular, ‘compositional devices, structure, notions of time and sequence, juxtaposition and memory which I am concerned with today are all there – albeit sometimes germinal – in the work of the 70s and 80s’. The same continuum may be remarked in her work over the subsequent twenty-five years.

The strategy that Crowe had devised in making the paintings of Jenny Armstrong after her death was deployed again but with a wider frame of reference. Paintings such as Jenny’s Room (cat. 43) and the still life paintings of her treasured possessions became portraits of the person who was no longer physically present –she was represented – or rather evoked – by the paintings. Years later, Crowe could return to the subject from memory and from aides-mémoire –drawings. She said: ‘I have freedom now to select from all the images of that interior, to make juxtaposition more telling and to let the sunlight fall where I will’.

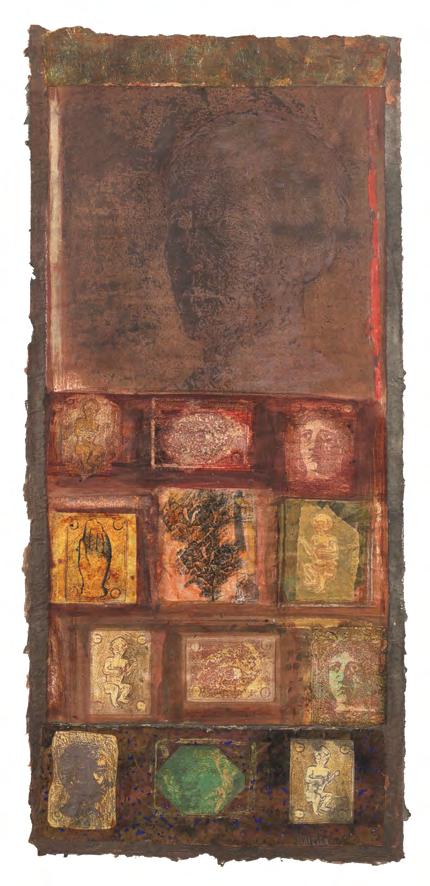

The idea of the emblem painting has remained a constant in her work – one that she has developed and elaborated over the intervening decades.

Another constant is the making of paintings that do not disclose their meaning at first sight. They are to be contemplated – we can look for meaning and decipher the encoded messages or freely associate and allow the different elements to trigger our own memories and ideas.

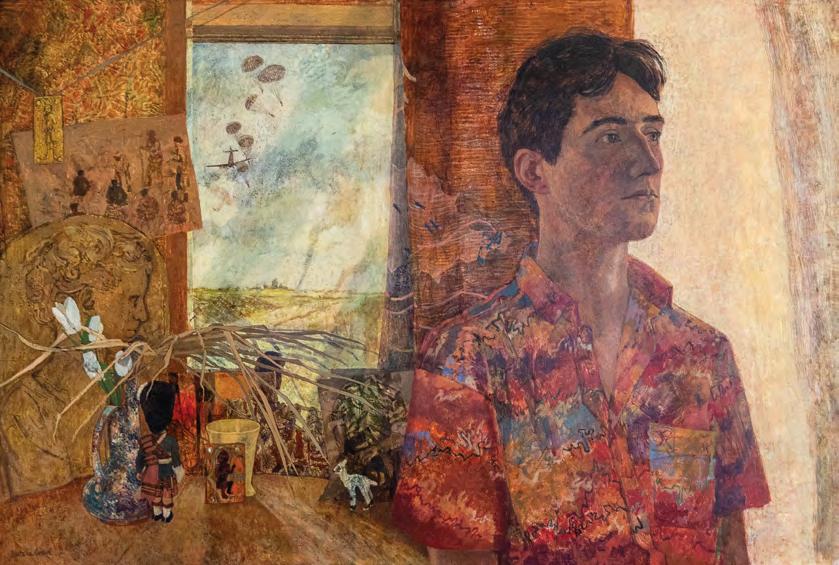

Her purpose is to make works that arrest, engage, evoke a response from the viewer. Painting has always been a way of ‘making sense of the world’ for Crowe. In the early 1980s, she was discovering new ways of interpreting and interrogating her experience. Her artistic practice was significantly expanded when she accepted two portrait commissions. Her subjects were the psychotherapist Winifred Rushforth and the psychoanalyst and author of The Divided Self, R D Laing. Rushforth introduced Crowe to Jungian theories of symbolism, myth, archetypes and the unconscious, while Laing revealed over the course of their sittings his restless search ‘to find a spiritual and intellectual truth that he could apply to his model of existence.’

It is difficult not to see, in hindsight, a curious synchronicity. Crowe had conceived a kind of portraiture that was as much concerned with representing the mind, the inner life of the subject as much as their external appearance.

The Jungian belief that the spiritual is contained within the material world continued to inform Crowe’s methods. This new insight was reinforced when, in 1992, she went to Italy for the first time. In Florence she saw works by Renaissance artists, including the Leonardo painting of the Annunciation that she had always wanted to experience first hand. This and other religious paintings, she said, were ‘images which fed the imagination by refusing to tie us to physical reality’. Like the Russian icons by Andrei Rublev that she had admired as a student, these works were images to be seen through, an access to a higher, metaphysical

reality. Henceforth, echoes of Italian paintings would be incorporated in her own. Memories of the angels, saints, the Tuscan landscapes seen through the eyes of Piero della Francesca – all internalised as part of her own pictorial language.

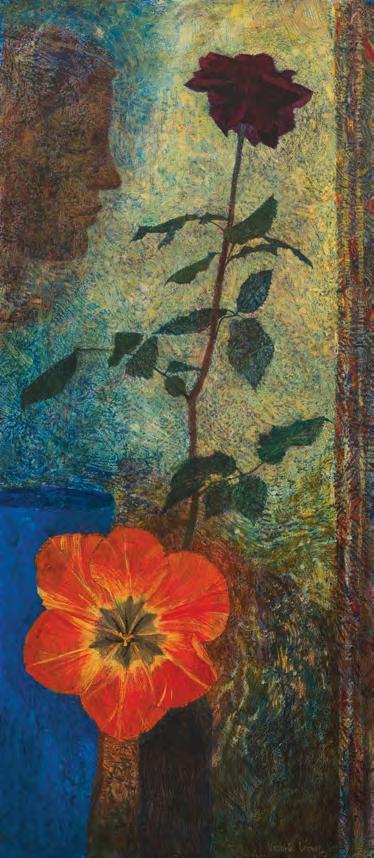

The 1990s was a decade of transformation. The pivotal event, the tragic loss of her son in 1995, was the catalyst for profound changes in Crowe’s approach to painting. There was a new freedom from constraints: if the world had shifted on its axis then so too all certainties, rules, conventions could fall away. They were no longer relevant. She felt herself unbound by their limitations – deaf to their demands. Now phantoms and dreams, memories and imaginings were more real than what passes for quotidian reality. The hallmark of her new style was a kind of visual paradox. She could combine night and day, indoors and outdoors, summer and winter, Kittleyknowe and Italy, the tangible and the intangible. Real people would co-exist along with the saints, madonnas and martyrs of the Quattrocento. Angels abound – messengers, harbingers from another realm. Butterflies and dragonflies with their inexplicably brief lives were juxtaposed with carved and painted heads – immortalised through the power of art. And above all, the eternal verities – the constant moon, the sun, the sea. Italian painting had reaffirmed Crowe’s interest in compositional devices that ‘stretched time and subverted logic’ through the deployment of ‘unexpected juxtapositions’ and a repertoire of signs and symbols.

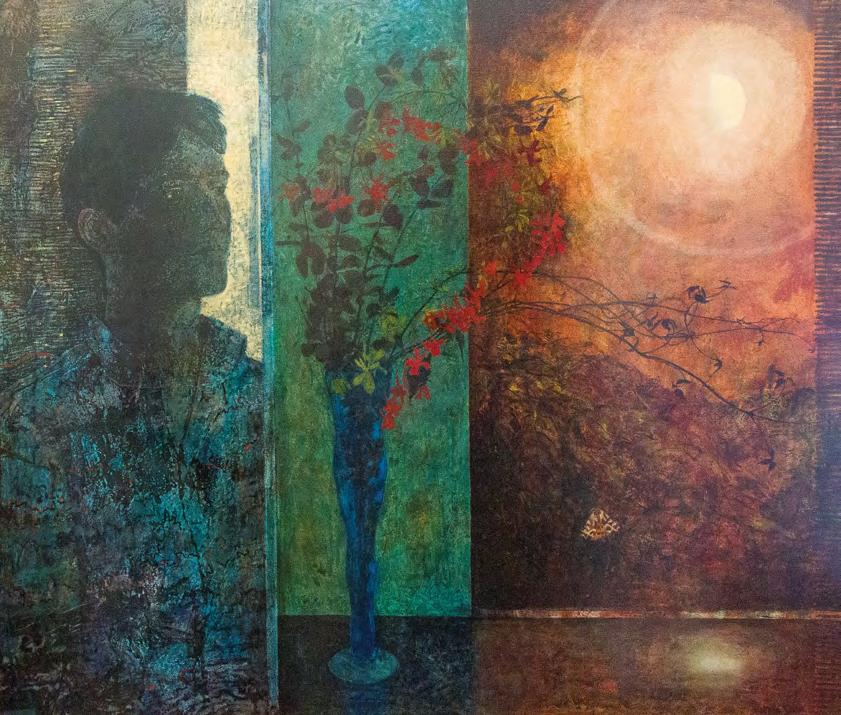

Her own work became replete with visual metaphor. In her last portrait of her son, Travelling by Moonlight (cat. 47), she has divided the picture surface into three sections. Ben is depicted in darkness on the left side, broken brushwork rendering his form insubstantial, his face in shadow against a radiant light. A strong vertical strip of light blue separates him from the rest of the composition. On the right, glowing red, a mysterious moon, and a butterfly – an emblem of the fragility, beauty and transience of life – is caught in suspended animation. In the central section is a vase of flowers, with tendrils reaching across the surface of the canvas, linking the central and right-hand disparate elements.

The interconnectedness of things interests her. The red flower in this painting echoes the recurring motif of a spray of a coral-like red flower that appears in several paintings by Crowe. It contains the memory of the coral hung round the neck of Piero della Francesca’s infant Christ, seen on a visit to the Brera Pinacoteca in Milan. The coral-like plant reappears in a portrait of her daughter, painted in Milan in 1995. The face is suffused with a green light, the colour of the underpainting that creates the shadows on the flesh of the infant Christ, and her eyes are stilled with a profound empathy.

For the first two decades of the twenty-first century, Venice played an increasingly important part in Crowe’s life and work. The city that John Ruskin called ‘a ghost upon the sands of the sea – bereft of all but her loveliness’ became, for the artist, a symbol of survival. As well as providing a seemingly limitless visual plenitude of beautiful architectural adornments and works of art, surrounded by water, Venice stood in contrast in its warmth, light and colour to the cold light and muted tones of the Pentland Hills that had for so long predominated her painting.

But Venice has its dark side too. When there, an ineluctable awareness of the past is acutely felt. The present and the past merge to create a strangely different reality. Crowe sometimes evokes the city in her paintings with the dark, lowering skies that presage a storm, or the solemn gaze of Bellini’s Magdalen, or the votive offerings placed before altars in Assembled Fragments – Gold (cat. 51).

Crowe found in Venice a quality she had been seeking in her paintings – a means of conveying a sense of the accretions of time, the past in dialogue with and informing the present: she noted ‘the creep of lichen, the flaking of paint, the rubbing away of gold… the process of change made visible.’

With few exceptions, Crowe’s landscapes are devoid of people. When she included the figure of Jenny Armstrong in her paintings, it was as an embodiment of tenacity and stoicism, dedicated to her flock and tending to them in all weathers. Like the tree in winter, she is a symbol of permanence and survival, her diminutive figure recalling the poet Edwin Muir’s description of a shepherd who, ‘probing deep through the snow-burdened hill, Resurrected his flock.’

There is a recurring motif in Crowe’s paintings of the single skeletal tree, devoid of foliage – solitary, subjected, blasted by the wind, and yet it too will survive; there will be the annual miracle when it reasserts its plenitude and is reborn. It is difficult not to anthropomorphise trees in her landscapes. They stand in ranks like protective guardians, black against the snow-laden sky, or transfigured – blazing red in sunset or silvered by moonlight. Crowe has said: ‘Trees do literally embody the passage of time: they are witnesses.’

Landscape has always evoked deities –whether the gods of Olympus or the spirits

and immortals of our ancient ancestors. Jung believed that we carry within us traces of our long-dead forebears and that this informs our response to Nature. We instinctively sense the Genius Loci, the spirit of the place, and recognise trees as living things, akin to us in a profound and elemental way.

Crowe has throughout her work tried to capture that feeling.

William Blake saw angels in trees. Anything is possible for the mystic. And anything is possible for the painter. As Picasso said: ‘There are no limitations to the human imagination.’

Crowe has said of the trees in West Linton that she has seen and drawn ‘over days and years of change, in all seasons, transformed by frost, snow and backlit by the winter sun… their familiarity to me seems to give them an iconic status. Which goes beyond the casual reality of the here and now, toward the contemplative’.

Julie Lawson

Snowbank, Sun and Shadows, 1979 (detail) (cat. 39)

37 | A Detail of a Battle, 1969 watercolour, ink and pencil, 22.5 x 31.5 cm

38 | Summer House in Winter, 1974 oil on board, 33 x 27 cm

39 | Snowbank, Sun and Shadows, 1979 oil on board, 75 x 53 cm

40 | Darkening Horizon, 1977

watercolour on paper, 20 x 44 cm

41 | Cottages in Moonlight, c.1976 oil on board, 39 x 45 cm

42 | Celebration for Margaret, the Fraser Boy, and all the Rest, c.1982

watercolour and acrylic on paper, 54.5 x 75 cm

43 | Jenny’s Room, 1987 watercolour, 54.5 x 78 cm

44 | Interior with Spring Lamb, 1987

watercolour, 100 x 83 cm

45 | Silent Assembly, c.1988

watercolour and acrylic, 37 x 94 cm

46 | Heroes and Villains, 1991 oil on board, 76 x 109 cm

47 | Travelling by Moonlight, 1995 oil on board, 95 x 109 cm

48 | Snowlight and Powerful Objects, 1995 watercolour, 75 x 100 cm

49 | Magical Landscape, San Gimignano, 1995 oil on board, 40 x 60 cm

50 | Night Journey, c.1999 oil on board, 81 x 35.5 cm

51 | Assembled Fragments – Gold, 1998

media, 72 x 33 cm

52 | Portrait of a Young Woman, Milan, 2000 oil on canvas, 51 x 66 cm

53 | Echoed Landscape, 2004

oil on linen, 91 x 101.5 cm

54 | Continuing Reflection, 2010

mixed media, 50 x 86 cm

55 | Holding the Heat of the Day, 2010 oil and mixed media on board, 60 x 49.5 cm

56 | Known and Imagined World, 2012 oil on linen, 101.5 x 114 cm

57 | Throughout a Single Day, 2018 oil on linen, 101.5 x 127 cm

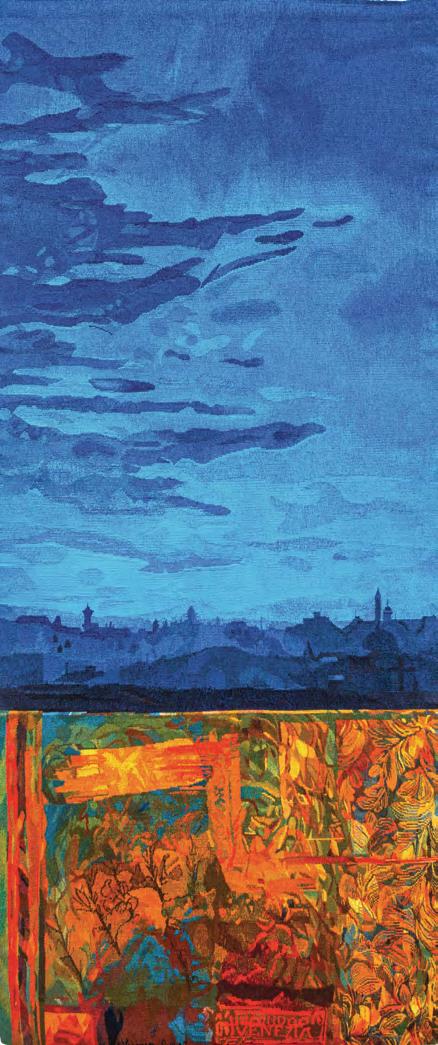

Richer Twilight, Venice is a tapestry inspired by a detail from Victoria Crowe’s painting, Twilight, Venice, 2014. Like many of Victoria’s Venetian paintings, Twilight, Venice features rich colours of a jewel-like quality that reflect the intangible preciousness of the city. Engaging with the textural complexity of the painting, Dovecot Master Weavers Naomi Robertson, Emma Jo Webster and David Cochrane, and Dovecot weaver Rudi Richardson, created a sumptuous interpretation of the work in conjunction with the artist which captured the tones and shades of twilight.

58 | Richer Twilight, Venice, 2019

handwoven tapestry, wool and cotton, 250 × 98 cm

woven by Naomi Robertson, David Cochrane, Rudi Richardson and Emma Jo Webster

VICTORIA CROWE OBE,

DHC, FRSE, MA (RCA), RSA, RSW (b.1945)

Victoria Crowe studied at Kingston School of Art from 1961-65 and at the Royal College of Art, London, from 1965-68. At her postgraduate show, she was invited by Sir Robin Philipson to teach at Edinburgh College of Art. For thirty years she worked as a part-time lecturer in the School of Drawing and Painting while developing her own artistic practice. She lives and works in West Linton and Edinburgh and held a studio in Venice for 20 years. Her first one-person exhibition, after leaving the Royal College of Art, was in London and has subsequently held over fifty, one person shows.

Victoria Crowe’s first solo exhibition at The Scottish Gallery was in 1970. In August 2018, The Gallery held a major exhibition of paintings to coincide with The Scottish National Portrait Gallery’s retrospective of Victoria Crowe’s portraits.

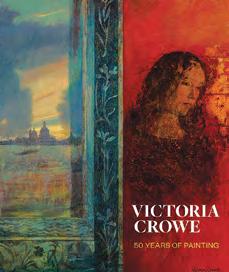

In 2019 The City Art Centre held a retrospective entitled 50 Years of Painting. This exhibition embraced every aspect of Crowe’s practice and featured over 150 paintings, works on paper and sketchbooks and several films of the artist were commissioned.

Victoria Crowe is a member of the Royal Scottish Academy (RSA) and the Royal Scottish Society of Painters in Watercolours (RSW). Crowe has exhibited nationally and internationally and undertaken many important portrait commissions, including HRH The King, RD Laing, Peter Higgs and Jocelyn Bell Burnell. Crowe’s work is held in numerous public and private collections worldwide.

In 2000, Crowe’s exhibition A Shepherd’s Life, consisting of work selected from the 1970s and 80s, was curated for the National

Galleries of Scotland’s to mark the Millennium. The exhibition toured Scotland and was re-gathered in 2009 for the Fleming Collection, London.

Crowe was awarded an OBE for Services to Art in 2004 and from 2004–2007, she was appointed Senior Visiting Scholar at St. Catherine’s College, Cambridge. The resulting work, Plant Memory, was exhibited at the Royal Scottish Academy in 2007 and subsequently toured Scotland. In 2009 she received an Honorary Degree from The University of Aberdeen and in 2010 was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh.

In 2013, Dovecot Studios wove a large-scale tapestry of Crowe’s painting Large Tree Group. This collaborative tapestry was acquired for the National Museums Scotland. In 2015, Crowe was invited as artist-in-residence at Dumfries House. In 2016, a group of work from the artist’s studio was acquired by the National Galleries of Scotland. Crowe was commissioned by the Worshipful Company of Leathersellers in 2014, to design a forty-metre tapestry for their new hall in the city of London, which took over three years to weave and was installed in January 2017. Dovecot worked with Victoria Crowe to produce a new tapestry inspired by a detail from her painting Twilight, Venice, 2014. The new tapestry, Richer Twilight, Venice was completed and unveiled at the end of September 2019.

Following a residency in Orkney in 2022, the Pier Arts Centre in Stromness held a major exhibition of new work, Touching the Surface from August to November 2024, in which she looked specifically at the contrasting light around the summer and winter solstices.

Crowe during her residency with Pier Arts Centre/RSA, Linkshouse, Birsay, Orkney, 2022. Photograph by Kenneth Gray

A Shepherd’s Life, Paintings of Jenny Armstrong by Victoria Crowe by Mary Taubman, Julie Lawson and Victoria Crowe

Published by the Scottish National Portrait Gallery (new edition 2018)

Victoria Crowe: Beyond Likeness by Duncan Macmillan, Julie Lawson and Victoria Crowe

Published by National Galleries of Scotland, 2018

PUBLICATIONS

Crowe by Duncan Macmillan

Published by Antique Collectors’ Club, 2012

Victoria Crowe: The Leathersellers’ Tapestry by Victoria Crowe and Naomi Robertson

Published by The Leathersellers’ Company, 2017

Victoria Crowe: 50 Years of Painting by Susan Mansfield, Duncan Macmillan and Guy Peploe

Published by Sansom & Co, 2019

Another Time, Another Place by Victoria Crowe and Christine De Luca

Published by The Scottish Gallery, 2021

Victoria

PUBLIC COLLECTIONS

Aberdeen Art Gallery

Art in Healthcare

Artlink Edinburgh – Western General Hospital

Calderdale Metropolitan Borough Council

Chatsworth House, Bakewell

City Art Centre, Edinburgh

Dumfries House, Ayrshire

The Fleming Collection

The Gibberd Gallery, Harlow Art Trust, Harlow

Heriot-Watt University, Edinburgh

McLean Museum and Art Gallery, Inverclyde

National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh

National Museums Scotland, Edinburgh

National Portrait Gallery, London

National Trust for Scotland, Hermiston Quay

Newcastle University

NHS Lothian Charity – Tonic Collection

Parliamentary Art Collection, London

Pier Arts Centre, Stromness

Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh

Royal Scottish Academy, Edinburgh

St Catharine’s College, University of Cambridge

St John’s College, University of Oxford

Scottish National Portrait Gallery, Edinburgh

The Hunterian, University of Glasgow

The Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh

The Royal Society of Edinburgh

University of Aberdeen

University of Edinburgh

Wardlaw Museum, University of St Andrews

West Lothian Council, County Buildings

Worshipful Company of Leathersellers, London

Worshipful Company of Painter-Stainers, London

Published by The Scottish Gallery to coincide with the exhibition

Victoria Crowe DECADES

August 2025

Exhibition can be viewed online at scottish-gallery.co.uk/victoriacrowe

ISBN: 978 1 917803 00 7

Produced by: The Scottish Gallery

Design: Kenneth Gray

Photography: John McKenzie, Boyd Wild, Kenneth Gray, Antonia Reeve

Print: Pureprint Group

All rights reserved. No part of this catalogue may be reproduced in any form by print, photocopy or by any other means, without the permission of the copyright holders and of the publishers. All essays and picture notes copyright The Scottish Gallery.

Cover: Tactile Traces, 2024, oil on linen, 89 x 102 cm (cat. 1) (detail)

Inside front cover: No Longer Able to Read the Signs, 2022, oil on linen, 91.5 x 76 cm (cat. 18) (detail)

Inside back cover: Cottages in Moonlight, c.1976, oil on board, 39 x 45 cm (cat. 41) (detail)