ROSS RYAN UNLEASHED

Ross Ryan | The Edge of the Ocean

A narrative, voyage or concept has always been the baseline for my approach to painting. I am yet unable to waltz up to the studio and create without stimulus, I need an expedition, something to pack and prep for. Ross Ryan

For Ross Ryan creative space is equivalent to a life lived. Sure, the smell of the studio, the urgency of a deadline, the critical examination of each work, needing frames and titles, are components of professional practice, but are secondary to the narrative of the creative life. Each work in his exhibition is a step taken on a journey that must stand alone, each a perfectly formed paragraph in a roman fleuve which tells the story of a man deeply engaged with exploring life on the margins.

Unleashed explores a hinterland of extremity, heading to Brittany, travelling to Ireland and finishing at home in Crinan. Friendships renewed, good family reasons, suddenly urgent pretexts, creative opportunism, all drive the itinerary. But it is no coincidence that the harsh coastlines of these Celtic fringes provide the maritime history of a people; voyaging, to raid, trade, fish and settle over three thousand years. A celt with a knowledge of boats will be accepted as brethren in any and each of these wild locales.

Brittany had been a destination oft considered, charts spread out, the logistics of an 800-mile sea journey for Sgarbh finally, always too much of an obstacle. But with his nephew Jock attending art school in Brest, his 21st birthday prompted a

gathering of the clans so Ryan headed to France in his van.

As I was to discover, Brittany was all things stormy and salty.

At Douaranez he found three familiar boats at rest on the banks of the Benot, thoroughbred sailing boats, sailed more than once to Crinan without engines: Swallow, Maggie Helen and Rose of Argyll – a wonderful introductory subject for the last leg. At Pointe du Raz the wind played havoc with materials, surf pounding the lighthouses, there to warn ships of the five-mile shoals going out to sea. Another day Ryan accepted the challenge of his nephew to visit and add to a piece of Breton graffiti on the German defensive fortifications at La Torche, sitting above a thirty-kilometre beach. A little ferry took him out to the low-lying Isle de Sein where he worked at the shore for as long as the tide allowed. He finished, safely restored to the mainland, in the company of Hubert, a boat builder who the artist knew from Clyde regattas, the former employer of his friend Jann, himself a vital contributor to the health and restoration of Sgarbh back in Argyll.

Ireland began with a summer sail to Ballycastle in the north where the artist turned fifty, enjoying the kindness of family and strangers, but was just the primer for an expedition with his van in the Autumn, to Crookhaven in South Cork. Here was familiarity, a village with one pub, a superstitious sea-faring people, but new visual stimulation: the

great slate cliffs, ancient adamantine fortifications speaking to the times of raiding; Viking and Corsair. A steep run of steps hewn out of the rock had been access for fishermen and smugglers to the green swell of the Atlantic, and didn’t make a bad subject for a drawing.

More subjects were found by way of Baltimore and a boatyard, to the ferry to Cape Clear Island, home to a hundred or so hardy souls, the southernmost inhabited part of Ireland. Castle Doonanore, a romantic ruin, black as tar on the jagged promontory gave the sailor in Ryan pause to be grateful he was travelling by van.

And finally, he met up with his nephew Archie in Galway, to surf and share a borrowed holiday home. Here he made his haunting painting depicting

moored, heavy Galway Hookers on a still, misty Atlantic day.

His final section is Home, and his sense of belonging extends from Crinan, to Iona and the Hebrides, to Fife and Port Seton. The sense of belonging is not exclusive to a patch of earth: Ryan sees painting as a means to uncover connections wherever he works, accessing familiarity of the unknown in the act of creativity. His paintings are waymarks along a path, not the fruits of arrival.

The connectivities of sea, boats and boatbuilders, of artists and places to discover and work, anchored the artist in his Celtic journey. But those exigencies of the professional artist drew him back to Argyll, with a van full of work, oils and works on paper, all arrayed around for the final selection of Unleashed.

Guy Peploe

The Journey

Brittany

A narrative, voyage or concept has always been the baseline for my approach to painting. I am yet unable to waltz up to the studio and create without stimulus, I need an expedition, something to pack and prep for. For the last body of work, it came easy. I awoke in the night and thought, ok, I like Joan Eardley, lets sail to Catterline. But this time I struggled and fretted till late. Then in October, my nephew made an exchange from the School of Art in Dundee for one in Brest, France’s maritime city. This and his pending 21st gave me the much needed, and wholesome, catalyst to follow suit.

Though the coast of Brittany has been simmering for years. Many a time the charts had been spread

out on the kitchen table with routes plotted to take the boat on the 800 mile trip south, but I never managed to cast off. Jann the boatbuilder, a Fife Frenchman, had spent his early chapters sailing off this rugged coast of France. During the 9 years we restored Sgarbh, I listened and encored such accounts of being ship-wrecked in the dark off the horrendous Pointe du Raz or living solely from giant crepes. At times he would break into Breton French giving meat to the subject. Stories that would have even had the great R.L. Stevenson put down his quill, and listen.

As I was to discover, Brittany was all things stormy and salty.

Ross Ryan

Mum and I headed off in the van, before her flight, to explore a little of Brittany’s coast. The Breton sun was generous, as we relaxed in a small fishing village drinking tea and discussing why we had not been here before, it was good to see her out of Argyll.

Across the river Benot I spotted three dark hulls, leaning in on each other, with plenty of rigging; it was them. Over the last ten years the boats had made several trips up to Crinan, sailing engineless from France and living in the most traditional

manner, foraging and fishing. I was truly in awe of these vessels, they were whippet-like under sail and only lacked blood in their natural form. The crew were nomadic and I envied and respected them equally. They had the carbon footprint of a robin.

Mum and I drew and painted as the tide slowly made its way up the hulls, giving their keels a rest. The Swallow, Rose of Argyll and Maggie Helen are undoubtedly the most beautiful boats I know, and all together was a rare treat.

1 The Three Old Ladies, Brittany, 20-11-24 oil on board, 74 x 116 cm

2 Through the Rocks to Ushant, Brittany, 21-11-25 oil on board, 116 x 132 cm

3 Douarnenez, Brittany, 22-11-24 oil on paper, 29 x 41.5 cm

4 Bourgh, Île de Sein, Brittany, 28-11-24 oil on paper, 29 x 41.5 cm

Today, wind, tide and swell were in the ring together. Pointe du Raz marks the start of a shallow shoal that runs five miles out to the island, Île de Sein. Infamous and treacherous.

Sufficient enthusiasm even brought the nephews and Izzie down from Brest, for a morning R.V. at a massive empty carpark, not so far from the point. Here the van shivered in warning as the dog-like wind chased itself around us. I loaded equipment up onto the human forklift, big Archie, and then selected a large board from the van. Jock donned a tight and short legged blue denim boilersuit, not unlike the one worn by Hannibal Lecter.

On arrival at the brow of the cliff the three lighthouses came into sight. Like stars from a 60’s blockbuster, they instantly shouldered us some massive waves, sending spray upwards well over their lights. We roared and cheered in approval, though the wind was having none of it, instantly gobbling up our cries.

The afternoon was comical, a far cry from painting alone. On more than one occasion the wind tore the pages off Archie’s sketch pad, with both paper and nephew flying by. All of us were participants in our own charade, drawing and painting as best as one could in these conditions.

On the way back we stopped at a sheltered beach further north. The boys suited-up and surfed, I declined and ate. The lighthouses, now several miles away looked far more vulnerable. I thought of Jann and the very different and terrifying time he must have had trying to save his soul and that of the crew, at this same Pointe du Raz. They all survived.

Back in Douarnenez I insisted the young stayed, checking them into my dishevelled Hôtel du Port We toasted, and celebrated life. A strong emotion had pumped through me, and I was not for ending it soon. Today is how I would want the boys to remember their artist uncle by.

5 Ripping Tide and Big Seas, Pointe du Raz, Brittany, 23-11-24 oil and pastel on board, 105 x 116 cm

I was early down at the ferry port in Audierne with very few clothes but a lot of materials. Yesterday’s gale was easing but like shark’s teeth the next stood close behind. I would get 24 hours on Île de Sein, or five days.

A lumpy residue swell of three metres made it a punchy run out on the small but robust ferry. I was impressed by the boat’s turn of speed and its ability to ride carefree up and down the waves. Literally this must be one of the worst ferry routes anywhere. Sac de Mal de Mer signs and bags were at every possible hand hold. Much like the Corryvrechan whirlpool, the seas were massively influenced by the current. I wondered silently how Sgarbh would have handled it.

We motored close by the three big lighthouses I had painted from Pointe du Raz, them now looking down on me. Despite only being two metres above sea level, the small Île de Sein has been inhabited since the Neolithic period. The buildings appeared to almost be squeezing themselves away from the water’s edge.

Much like Barra there was a good turnout of locals when the ferry came in. Supplies were craned off with crates of fruit, veg, beer and wine, not a Tesco bag in sight. I was led down the narrow car-less streets, taken by the number of beautiful buildings crammed into an island smaller than Iona. Even a couple of good-looking bars.

The Atlantic wind was chilling as I made sketches of the town’s façade, from the bottom of a jetty. Chutney, in her puffer, was tightly curled up on top of my old East German painting jacket. Eventually, with water around paws and feet, the tide chased us back up to the street, step by step.

The evening drawing was of the small lighthouse in the town. I was completely frozen, the picture was done more with shoulder movements than that of the hand. A local had us out a half hour longer as he explained the significance of the eye mural on the harbour wall. As in Malta and parts of Greece, the eye is there to keep a lookout for mariners and migrants on the sea.

6 The Eye and Lighthouse, Île de Sein, Brittany, 24-11-24 oil on canvas, 40 x 45 cm

7 Raging Sea, Brittany, 28-11-24 oil on board, 116 x 122 cm

8 Île de Sein on Approach, Brittany, 28-11-24 oil on canvas, 46 x 102 cm

9 Town Lighthouse, Saint-Pierre, Brittany, 25-11-25 oil on canvas, 20 x 25 cm

10 Tévennec Lighthouse, Brittany, 30-11-24 oil on board, 67 x 67 cm

11 Phare de Goulenez, Île de Sein, Brittany, 27-11-24 oil on paper, 15.5 x 29 cm

12 Mont Saint-Michel, Normandy, 1-12-24 oil on paper, 24 x 28 cm

My nephew Jock had mentioned there was a lot of graffiti in Brittany, something I had wanted to revisit since my time in Berlin. I was told to head down to the old Nazi bunkers and fortifications at La Torche, a beautiful 30 kilometre beach.

The graffiti was bright against the old concrete and ran mainly at head height, within reach of the spray can. There were many ‘tags’ (artists’ logos) claiming their space, but some of the works were more maritime, like a giant French crab, an amusing break from the hard gang image. The bunkers on the beachside were fascinating. Slowly

over time they had been getting inched out to sea. Waves pushed through the reinforced structures where old windows and doors would have been. Hitler would have been mortified by the metal daisies now sticking up gayly on top of the bunker’s roofs.

A few days later, a bag of spray cans were slung into the van and we headed out to an electrical transfer station on the outskirts of Brest. I think Jock had been keen to show his old uncle that he was now the edgy artist in the family.

The hum of power led us down to well painted walls, that kept the likes of

13 Bright Colours on Old Scars, La Torche, Brittany, 26-11-24 oil on paper, 42 x 59 cm

himself from being barbecued. After just three months of being in Brest, Jock knew most of the tags. I sensed his enjoyment as he slagged or praised the works as we looked for a space to cross another artist’s work (spray over). My expensive canvas primer was used to get a good base, then he got busy with his cans, like an octopus drummer. Chutney and I looked on as Cyprus Hill blasted from the portable speaker, this was certainly not a covert operation. Jock tagged under the name of ‘Selk’ or Selkie, the mythological seal/human.

Some locals appeared with several large dogs, apparent regulars for a spot

of weekend drinking, they even had their own makeshift table set up. The dogs were the feral type, I could tell this from the way they scanned purposefully about in a pack. It was not long before they were over at Chutney, a quick sniff, then they went for my sweet wee dog. Like a tuna fisherman I swung her upwards on the lead with a big jerk, sending her up into my arms and clear of the mauling she would have got. I was ready to take them all on, fight or die for my little companion. Good fortune had the owners round their individuals up, quick style. Nothing was made of it, though out of sight my heart was about to burst!

Jock’s Graffiti, Brest, Brittany, 30-11-24

Ireland

During the summer I sailed down to Ballycastle in Northern Ireland joined by Mike and the dog, Chutney. Ireland seemed a reasonable place to turn 50.

The weather was settled, with just a gentle lift from the swell and kind tides all the way to the cosy harbour. A cold wind from the Northwest arrived the following morning, one that stayed for the best part of two weeks. The boat slowly transformed into a static caravan. My cousin Evette and her man, David, lived only 15 miles away which in turn opened-up a wealth of kindness and knowledge for this beautiful coast.

Finally, the June birthday rolled by, one, for which, I could not have wanted for more. A surprise drop-in from Huw, followed by a gathering in the belly of the Sgarbh. We ate red meat and drank a case of Pol Roger.

As soon as the Sgarbh was tucked up for winter I beelined it in the van all the way from Crinan to Crookhaven, County Cork.

Robert, an old friend from primary school, had lent

me his family house situated on one of the last fingers of land in Ireland. Security lights revealed a wonderful and idyllic home, reclusive and comfortable. I was touched by their generosity. However long the drive was we were soon walking down to the pub, O’Sullivans. I had been tasting this pint since Carlisle.

Not unlike Crinan, Crookhaven is a one boozer town, with a couple of piers and some creel boats. It was a black night aside the flood lit gable-end of O’Sullivans. Here was a huge mural of a pint of Murphys, replacing the lighthouse of Fastnet rock which winked just a few miles out to sea. The first life that came into view was a golden retriever dressed as a lion, Chutney too was made up for Halloween, wearing bat wings. The pub was emptying out with families taking their sweet-filled and tired kids home. I soon blended in with the regulars and blew the top off a cold black pint.

The craic was good, but I extracted myself out onto the pier and got a wee drawing done. Fortunately, I had left my passport in the van, otherwise I would have chucked it in the sea!

Ross Ryan

15 High Tide Ireland, 4-6-24 oil on board, 17 x 15.5 cm

16 Low Tide Ireland, 4-6-24 oil on board, 17 x 15.5 cm

17 O’Sullivans Pub, County Cork, 31-10-24 oil on canvas, 20 x 25 cm

O’Sullivans pub also served as an excellent tourist bureau. One man and a dog take little time to go unnoticed in a small Irish fishing village. The nods became bigger and I was soon drawing the stool into craic. Asides their houses, each evening the locals made suggestions of places for me to paint, all of them carrying an underlying narrative.

Today’s location was Three Castles, a series of ruined towers joined by an equally ruined wall.

Don’t look in the loch, or you’ll be cursed like the others by the Grey Lady, three this year. I had been warned.

I don’t take superstitions lightly after growing up in a fishing community myself. Be it red heads and ministers onboard or launching on a Friday, it all had to be considered.

I was soon to find out the loch was right by the castles, which made the drawing almost impossible without glaring into the water. I abandoned the work and made my way back to the van. The coast was built of huge slate cliffs, like nothing I had seen before. A small path down a ravine exposed a series of steep steps chiselled out of the rock that led into the water. The green surging Atlantic was smooth, just the kelp waving slightly. I was mesmerised and spent the next 3 days here. Sketching, painting and just looking.

As it turned out, in 2007 Ireland’s largest drug haul was made in these waters. A heavily laden dingy was overwhelmed and capsized on the way to the steps, after a rendezvous with a foreign yacht. The street value of the coke washed up was 200 million dollars. 50 bales were recovered. But was that all of it?

The ferry departed from Baltimore with all manner of equipment to keep a small island breathing. The run out to Cape Clear was a complicated channel of marker buoys and small islets. Like everywhere else round here the rocks were black, sharp, and unforgiving. The type that make a boat wince.

With just four hours ashore there would be no ‘soaking it up’. As the ferry came alongside, I had already spotted the bright red and handsome looking trawler resting on the harbour wall. A tall fisherman slowly and methodically laid on more red paint to the hull, while it seemed the rest of the world was tripping over itself. We had a blether about Gardner engines and then I quickly shot over the brow of hill, to catch a glimpse of castle Doonanore. Black as tar it stood on the extremities of the point, surrounded by the most awful reefs and rocks that made

my stomach turn. During the trip back to the mainland I could not undo the devilish sight.

I had spotted this yard the previous day on the drive out to Baltimore, to catch the Cape Clear ferry. A multitude of boats, in varying states and age, lay on the muddy tidal flats of the river Ilen. This was Ireland’s last surviving wooden boatyard. I could have done my whole show here. I was let loose by the friendly and knowledgeable Mr Hagerty after explaining, I too, had the rare and incurable disease of being a wooden boat restorer. Old trawlers, transatlantic classic yachts and some work boats stayed still like the best of life models. Two otters under the old pier played close by, either unafraid or unaware. Like so many times in Ireland I smiled warmly within.

18 Steps to the Sea, County Cork, 2-11-24 oil and pastel on board, 84 x 67 cm

19 Red Fishing Boat, Cape Clear Island, County Cork, 4-11-24 oil on canvas, 40 x 45 cm

20 Hagerty’s Boatyard, County Cork, 6-11-24 oil on paper, 42 x 59 cm

After meeting Archie in Ennis for the Trad Festival, we spent five fantastic days surfing on the beaches of Lahinch. A deep Atlantic low was firing beautiful rounded waves shoreside. I had the best surfing in years, managing to hold onto a small amount of credibility with the nephew.

Archie’s pal, Owen, had use of his folk’s house in Galway, so there was a welcome break from kipping in the van. On the misty and cold drive into town I spotted four Galway Hookers alongside the dock. The Hookers were a typical fishing vessel from these waters in the 1800s. Heavily built and with large bows for dealing with an uninterrupted Atlantic Ocean. Night arrived before I got down with the paints, the mist was still present, making it wonderfully eerie.

21 Old Boats, Misty Night, Galway, 11-11-24 oil on canvas, 87 x 102 cm

22 Castle Doonanore, Cape Clear Island, County Cork, 4-11-24 oil on paper, 29 x 41.5 cm

23 Old Galway Fishing Fleet, Galway, 12-11-24 oil on paper, 59 x 42 cm

Home

Home is a sense of place, not just the physical rocks, but also those who walk upon them.

My works are not solely layers of paint, people are also mixed in with the colours, you just can’t see them. I feel there is a unique and natural path in Scotland that connects people and land through thousands of years of storytelling. I write about these relationships built on the islands and coasts, and they draw me back to paint in every way equal to the turquoise waters and white sands.

Ross Ryan

24 Snow Covered North End, Iona, 17-1-24 oil on board, 74 x 123 cm

25 Bay at the Back of the Ocean, Iona, 16-1-24 oil on board, 24 x 41 cm

26 Windy, Very Windy, Iona, 21-1-24 mixed media on board, 20 x 30 cm

27 Thick Snow, First Light, Iona, 17-1-24 oil on canvas, 100 x 170 cm

28 Stoorie Nightfall, Bay at the Back of the Ocean, Iona, 18-1-24 oil and pastel on board, 102 x 122 cm

Getting the wind and sun out on the same day is rare. I had all the raging white but also the colours, enhanced by the strong light. I was lucky this work remained in one piece, so violent was the wind.

29 Carnage on the West, Iona, 20-1-24 oil and pastel on board, 122 x 155 cm

Today was the end of Chutney’s first painting trip. Both of us had to adapt. Settling to work on the beach with an unwalked 2-year-old just didn’t work. However, the pre-painting amble was becoming a worthy routine. I was able to walk in what was to become my painting, while she got to excavate the beaches. Although, a fleeting moment of complacency had its consequences. While pushing out more colours onto the palette, my exposed ham sandwich was ravaged. As I retrieved the remaining calories, now just a miserable sandy bit of bread, she had quickly moved onto my paint!

Pale blue, used to lift the tint of Iona’s waters, had now turned Chutney into a ‘Brave Heart’ extra, her muzzle covered. 25 years of coastguard training did little to calm me, as I frantically used rags and tea to clean her up. The following hour was spent meerkat-like, scrambling over the rocks on the ‘North End’, trying to get reception while speaking to the vet. Fortunately, she was extremely composed and assured me that plenty of Argyll dogs had done far worse. I’ll let you decide if stress is good for work.

30 Last of the Storm, Iona, 24-1-24 oil on canvas, 40 x 45 cm

31 Grey Seas Under, Iona, 23-1-24 oil on board, 74 x 94 cm

32 Snow Covered Sand, Iona, 24-1-24 oil on board, 92 x 115 cm

33 Sgarbh Makes a Rough Rounding, 5-9-24 oil on canvas, 16 x 21 cm

34 Morning Glass for Sgarbh, 5-9-24 oil on canvas, 20 x 22 cm

35 Campbelltown Fleet, 10-11-24 oil on canvas, 45 x 50 cm

36 Storm Eowyn in Crinan, Wow!, 24-1-25 oil and pastel on paper, 28 x 29.5 cm

37 A Night to Remember, Crinan, 9-12-24 oil on canvas, 45 x 50 cm

38 Late Blue Light, North End, Iona, 13-1-25 oil on paper, 42 x 59 cm

39 The Reef, Looking to Ireland, Kintyre, 10-12-24 oil on canvas, 50 x 60 cm

40 Good Surf, the Reef, Kintyre, 27-12-24 oil on canvas, 30 x 30 cm

41 Thick Foam and a Heavy Gale, Kintyre, 22-12-24 oil on canvas, 76 x 76 cm

42 Ronachan to Jura, Kintyre, 2-1-25 oil on canvas, 87 x 87 cm

43 Almost Night, Tarbert, Loch Fyne, 15-12-24 oil on canvas, 40 x 45 cm

44 Tobermory Nights, Isle of Mull, 5-1-25 oil on canvas, 30 x 30 cm

45 The Oban Ball, 28-12-24 oil on canvas, 30 x 30 cm

46 Busy Pittenweem Harbour, 5-2-25 oil on canvas, 30 x 30 cm

47 Cheerio Sun, Saint Monans, Fife, 5-2-25 oil on board, 32 x 67 cm

Many years had passed since I had been in the lovely Neuk towns. Saint Monans though, is particularly special. Duanach, Mum’s small exfishing boat had been built here. This was the first boat I was aboard at one week old.

48 My Fish Supper, Anstruther, 4-2-24 oil on canvas, 24 x 30 cm

49 My Van in Crail, 3-2-25 oil on canvas, 50 x 60 cm

Artist John Bellany was born in Port Seton from generations of fishermen. I met him briefly at an exhibition of his prints while I was at art school in Aberdeen. I was never one to follow other people’s work, but Bellany was the exception. Today was a bit of a pilgrimage.

I asked at the thrift shop if there was still any of Bellany’s family around. I was directed to his cousin’s house, one of the old fisherman’s cottages overlooking the links. He was another John, of about 80. We talked about the old yard at Cockenzie, where they built the loveliest herring

boats, not dissimilar to Sgarbh. On the wall behind John was a fine model boat, one which he had worked on, Queen of the Fleet, the artist’s father had made it. I could have spent hours chatting in the porch.

Later when painting, I thought of Bellany. I wondered how it must have been to be such an able painter. Working on large canvases down at Port Seton, at a time when the harbour would have been stinking of fish and not a spare bit of water to park a boat.

50 Port Seton, 1-2-25 oil on paper, 42 x 59 cm

51 Kilmory, Argyll, 9-1-25 oil and pastel on board, 45 x 62 cm

52 Cracking Day, Tangy, Kintyre, 7-2-25 oil on canvas, 50 x 60 cm

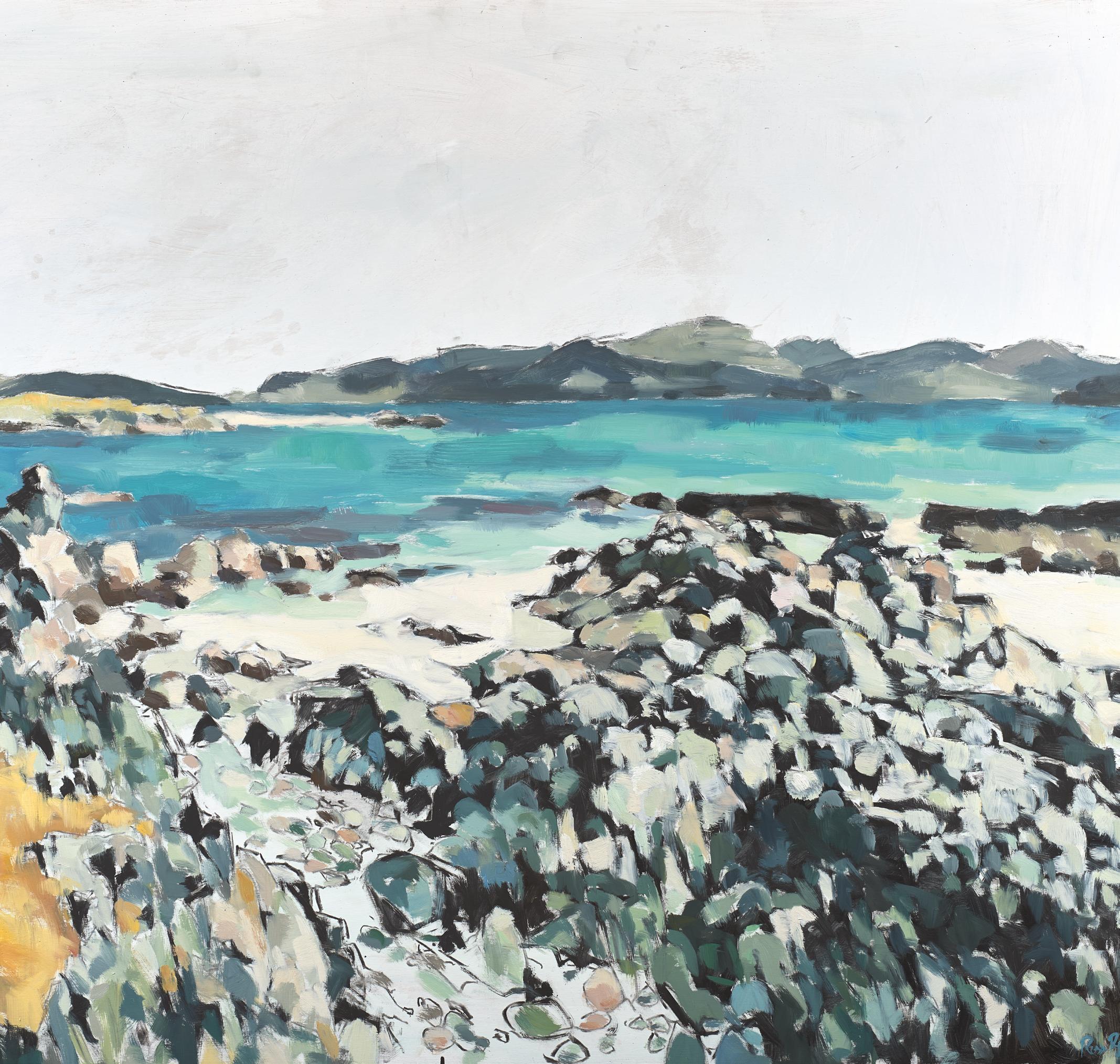

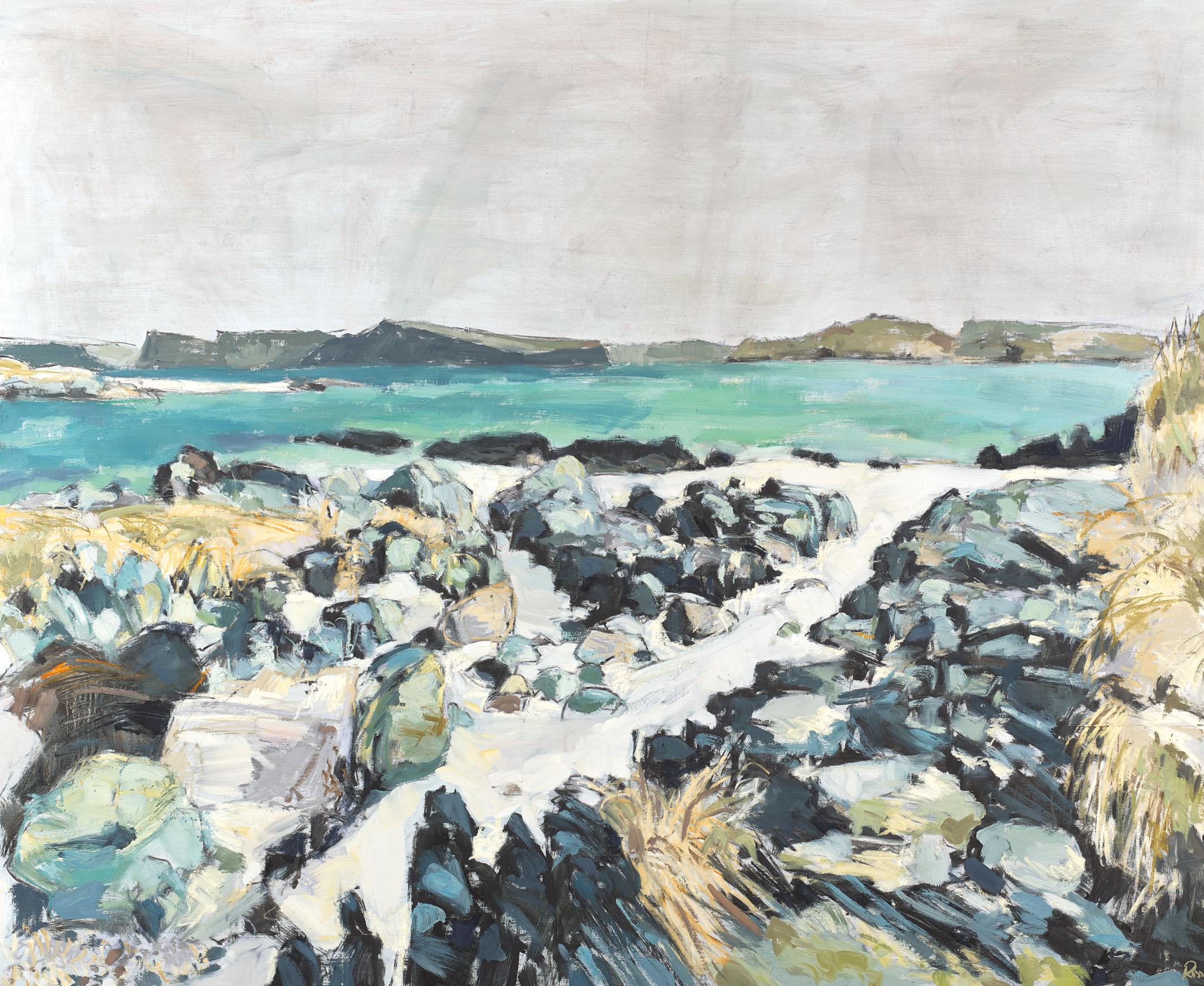

This was the last of the winter’s painting trips out to Iona, I would soon have to get the boat in commission for Spring. Slowly, I lugged the gear over the machair, Chutney pulling hard on her back legs, clearly aware a beach was imminent.

I had discussed with Mum previously, the struggle I had been having painting the wide expanse of white sand in the middle of the beach, just the intensity of it. The tide was incredibly low, being pushed out further by the high pressure. Here I found several new spots with plenty of boulders, slabs and rockpools. For every 5 degrees I moved my head there was another painting. I fed Chutney and then wrapped her in a wee rug. She was soon asleep, warm but enjoying the cold air.

I spent the next two days here.

53 Crystal Clear, North End, Iona, 10-2-25 oil on board, 122 x 160 cm

54 Through the Rocks to Eilean Annraidh, Iona, 10-2-25 oil on paper, 42 x 59 cm

55 Arriving at the North End, Iona, 12-2-25 oil on paper, 42 x 59 cm

56 Boulders, Rocks and Sand, North End, Iona, 9-2-25 oil and pastel on board, 116 x 145 cm

Ross Ryan, b.1974 Education

Gray’s School of Art, Aberdeen, Scotland, BA Hons Fine Art 1993-1997

Selected Solo Exhibitions

The Scottish Gallery, Edinburgh, Scotland 2025

The Scottish Gallery, Edinburgh, Scotland 2022

The Scottish Gallery, Edinburgh, Scotland 2020

The Scottish Gallery, Edinburgh, Scotland 2018

The Scottish Gallery, Edinburgh, Scotland 2013

Nelimarkka Museum, Alajarvi, Finland 2013

Kupferdiebe Gallery, Hamburg, Germany 2012

Santa Cruz, Galapagos, Ecuador 2011

Gallery Herald, Bremen, Germany 2010

The Scottish Arts Club, Edinburgh, Scotland 2009

R.G.I Kelly Gallery, Glasgow, Scotland 2004, 2005, 2007, 2009

Selected Group Exhibitions

Portland Gallery, London, England 2024

Gallerie Biesenbach, Cologne, Germany 2015

Atom Gallery, London, England 2015

“14” Bermondsey, London, England 2014

Lawrence Alkin Gallery, London , England 2014

White Cube, London, England 2014

RAR Gallery, Berlin, Germany 2013

Goldberg, Berlin, Germany 2012

Bunker, Bremen, Germany 2012

Goldberg, Berlin, Germany 2011

Lime Gallery, Glasgow, Scotland 2004-2009

Sotheby’s Auction House, Tel Aviv, Israel 2001

The Elisabeth Foundation For Arts, New York, United States 2001

The Lighthouse, Glasgow, Scotland 2001

The Roger Billcliffe Gallery, Glasgow, Scotland 2001

Philips Auction House, Edinburgh, Scotland 1997

Scottish Arts Club, Edinburgh, Scotland 1996

Published by The Scottish Gallery to coincide with the exhibition:

Ross Ryan Unleashed

8 - 31 May 2025

Exhibition can be viewed online at: scottish-gallery.co.uk/rossryan

ISBN: 978 1 912900 98 5

Printed by PurePrint Group

Designed and produced by The Scottish Gallery

A big thanks to everyone at The Scottish Gallery, Brien and Brown Framing and John McKenzie Photography.

And those who helped while underway:

The Gordon Family

My sister Julia and the boys

The Rankin Family

Hubert and Silvia Mum

All rights reserved. No part of this catalogue may be reproduced in any form by print, photocopy or by any other means, without the permission of the copyrightholders and of the publishers.

57 The Scottish Gallery, Edinburgh, 14-2-25 oil on board, 19.5 x 22.5 cm